Abstract

The extravasation of contrast agents is one of the most common and remarkable complications during a computed tomography (CT) scan. The clinical manifestations are commonly minimal, leading to mild symptoms. However, in rare cases of high-volume extravasation, the complications are extremely threatening. Compartment syndrome of the hand and the forearm leads to critical dysfunction and upper limb necrosis. This article reported an unusual case of hand compartment syndrome following extravasation of iodinated contrast agent from a peripheral venous catheter, during a CT angiography, and its surgical treatment. Moreover, a literature review regarding all published similar surgically treated cases was conducted.

Keywords: computer tomography angiography, complication, extravasation, contrast agent, compartment syndrome, hand

INTRODUCTION

The extravasation of contrast agents is one of the most common and remarkable complications during a CT scan [1]. The clinical manifestations are commonly minimal, leading to mild symptoms. However, in rare cases of high-volume extravasation, the complications are extremely threatening [2, 3].

This article reported an unusual case of hand compartment syndrome following extravasation of iodinated contrast agent and its surgical treatment. A literature review regarding all published similar surgically treated cases is also presented.

CASE REPORT

A 79-year-old male patient was admitted to the emergency department with critical limb ischemia. A computed tomography angiography (CTA) was conducted to evaluate arterial blood flow of the right lower extremity. CTA was performed by infusion of an iodinated contrast agent through an automated power injector from a distal vein at the dorsal aspect of the right hand.

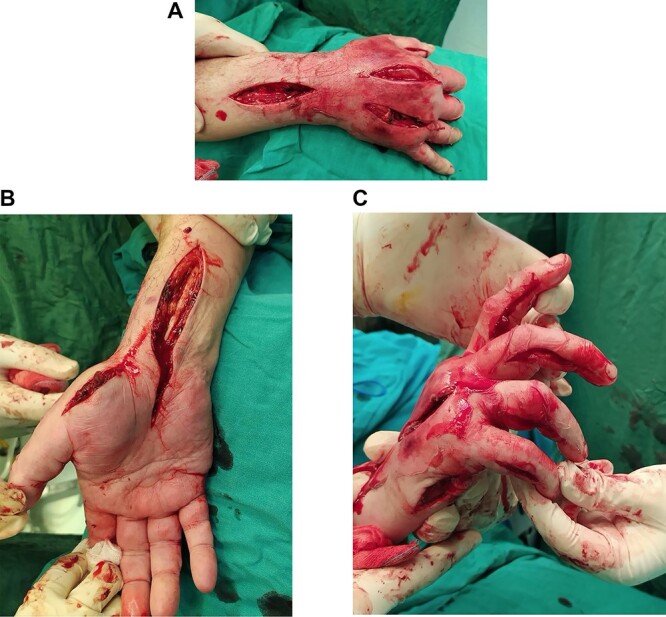

Shortly after the infusion, the patient was admitted to the surgical department complaining of acute pain on his right hand at the site of the infusion. Physical examination revealed a swollen, paleness, erythematous and tense hand with skin blistering on dorsal aspect (Fig. 1). The hand appeared warm with diminished but not absolutely absent pulses along radial and ulnar arteries, loss of superficial sensitivity and minus posturing. Fingers were also swollen, and capillary refill time was prolonged. Passive extension of the fingers was very painful. The pain remained for up to 6 h. Conservative treatment with elevation of the forearm and analgesics did not improve the clinical symptoms. Compartment syndrome (CS) was diagnosed, and 8 h post infusion the patient underwent emergent fasciotomies.

Figure 1.

Swollen, paleness, erythematous and tense hand with skin blistering on dorsal aspect following extravasation of iodinated contrast agent.

Multiple incisions of the hand and the forearm were required to decompress all involved osseofascial compartments (Fig. 2a–c). Primarily, two dorsal longitudinal incisions through second and fourth metacarpal were done in order to decompress the dorsal interosseous (×4) compartments. Dissection of the fascia was carried down along the sides of each metacarpal. The hematoma as well as fluid were also drained (Fig. 3). Deeper dissection was continued along the radial aspect of the second metacarpal to release the adductor compartment. Afterwards, two volar incisions over the thenar and hypothenar area (radial to the first metacarpal and ulnar to the fifth metacarpal, respectively) were made so as to reduce the pressure of the aforementioned compartments. Volar interosseous (×3) were also released. Digits’ compartments were additionally decompressed via ulnar longitudinal incision of each finger. Subsequently, the carpal tunnel ligament was dissected through a palmar longitudinal incision and the median nerve was decompressed. Finally, the increased forearm pressure of volar, dorsal and mobile wad (lateral) compartments was also relieved.

Figure 2.

(A) Dorsal decompression of the dorsal interosseous and antebrachium compartments. (B) Thenar and carpal canal decompression. (C) Hypothenar decompression along with digit release via ulnar longitudinal incision of each finger.

Figure 3.

Hematoma along with fluid drained during the decompression.

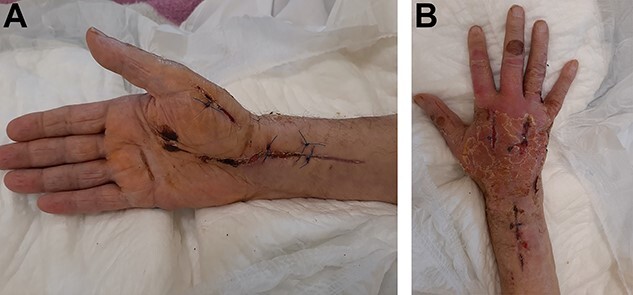

The patient’s post-surgery clinical appearance was gradually improved. Five days after decompression, the patient returned to the theater and underwent a delayed wound primary closure (Fig. 4a and b). At the last follow-up, 2 months after the surgery, the patient had retrieved full range of motion of the wrist joint and the fingers. The wounds were healed adequately and the possible risk of upper limb necrosis and dysfunction was overcome.

Figure 4.

(A) Twenty-day postoperative view of the hand with tension-free skin closure. (B) Twenty-day postoperative view of the hand with tension-free skin closure.

DISCUSSION

According to literature, extravasation can be frequently observed in infants, young children, unconscious patients, elderly or frail patients with fragile blood vessels or patients receiving chemotherapy. More severe extravasation injuries observed in patients with low muscular mass and atrophic subcutaneous tissue. Arterial or venous insufficiency as well as compromised lymphatic drainage could also lead to extravasation of contrast medium in the subcutaneous tissue during the infusion procedure [1].

Large volume extravasation, commonly defined as a quantity over 50 ml, as well as the usage of an automated power injector pump can cause severe skin ulceration and necrosis [2]. The type of venous access affects the frequency of extravasation. Extravasation injury is frequently associated with injection into the dorsum of the hand or the foot [1]. Across the recent literature there have been reported 16 similar cases (Table 1) who experienced CS due to contrast medium (non-ionic iodinated) extravasation at hand and/or forearm that needed urgent fasciotomy in order to avoid irreversible complications of the limb.

Table 1.

Twelve papers (listed in chronological order) reporting compartment syndrome due to contrast medium extravasation at the hand and/or forearm that treated surgically

| Author | Age | Localization | Contrast medium used | Distal pulses | Time of surgery | Fasciotomies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loth et al. 1988 [7] | 51 years | Hand | Renografin 76 (Diatrizoate meglumine) | N/A | 20 h | N/A |

| 40 years | Antecubital area | Mixture of Renografin 60 & 30 | N/A | 6 h | N/A | |

| 54 years | Forearm | 150 ml of 60% iothalamate rneglumine | yes | N/A | N/A | |

| 47 years | Forearm and hand | 45 ml 60% iothalamate rneglumiec | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 45 years | Forearm | 60% iothalamate rneglumin | N/A | 1 h | N/A | |

| Selek et al. 2007 [8] | 70 years | Hand | 100 ml of non-ionic iodinated contrast medium (Ultravist 300) | N/A | 8 h | Carpal tunnel, interosseous and adductor compartments |

| Grand et al. 2008 [9] | 48 years | Forearm | 53 mL of Omnipaque 350 contrast medium | Absent | 1 h | Carpal tunnel, volar and dorsal of the forearm |

| Ensat et al. 2010 [10] | 44 years | Left forearm | non-ionic iodinated contrast medium (Xenetix) | Absent | N/A | N/A |

| D'Asero et al. 2010 [3] | 81 years | Hand | 100 ml of non-ionic iodinated contrast medium | Absent | N/A | Interosseous compartments, thumb adductor |

| Belzunegui et al. 2011 [2] | 50 years | Hand | 100 ml non-ionic iodinated contrast (Optiray UltraJet 350 mg/ml) | N/A | 6 h | Interosseous compartments, thenar, hypothenar, carpal tunnel, thumb adductor |

| Güner et al. 2012 [11] | 48 years | Hand | 90 ml of the non-ionic water-soluble iso-osmolar contrast medium, iodixanol | asent | 3 h | Dorsal interosseous and adductor compartments, thenar, hypothenar, carpal tunnel |

| Altan et al. 2013 [12] | 23 days | Hand and forearm | 10 ml of iohexol Omnipaque (non-ionic) | absent | 2 h | Extended volar, carpal tunnel |

| Yurdakul et al. 2014 [13] | 60 years | Hand | 100 ml of iohexol (non-ionic) | absent | 2 h | Dorsal interosseous compartments, carpal tunnel |

| Vinod et al. 2016 [14] | 63 years | Hand | 100 ml Optiscan-300, containing iohexol | N/A | 15 h | Dorsal interosseous compartments |

| Stavrakakis et al. 2018 [15] | 72 years | Hand | 110 ml of Iopromide | N/A | 5 h | Interosseous compartments, thenar, hypothenar, carpal tunnel, thumb adductor |

| van Veelen et al. 2020 [5] | 43 years | Forearm | 110 ml of iomeprolum, non-ionic iodinated contrast medium | Absent | 39 min | Carpal tunnel, volar and dorsal of the forearm |

In our case we used an automated power injector and a high osmolar contrast medium (Scanlux 300 mg/ml, iopamidol) in an elderly patient with a documented past medical history of arterial insufficiency. The infusion was made through a distal vein at the dorsal aspect of the right hand. Therefore, the error that was detected in our case was an inadequate intravenous access site in a patient with high risk of vessel rupture. In order to reduce the risk of contrast extravasation injury we could use contrast agents with low osmolality (iopamidol) through larger veins at the antecubital fossa.

The diagnosis of acute CS is mainly clinical. The 5Ps’ rule (pain, paresthesias, paralysis, pallor and pulselessness), as well as palpable fullness, presence of blisters, erethymatous or dusky hue are findings that lead to a clinical diagnosis consistent with the CS. Apart from pain, the remaining appear as late findings [1, 3, 4].

According to Mandlik et al. [4] all the aforementioned clinical findings suggest severe injury and, in some cases, necessitate early referral to (plastic) surgeon consultation. The treatment of extravasation injuries should be described as conservative. It is not possible to predict whether the extravasation injury will resolve naturally or will result in necrosis, ulceration or permanent soft tissue injury [1]. Another treatment option for prevention of CS is the so-called ‘wash out’ technique [1, 4, 5].

According to Rubinstein et al. emergency fasciotomy is used as last attempt to treat acute CS. This therapeutic process should be performed as soon as possible, preferably within the first 6 h, in order to relieve neurovascular compromise and prevent further deterioration [6].

CONCLUSION

We should always be aware of this extremely threatening complication, so early identification is of paramount importance in order to reduce the risk of irreversible ischemia of the hand. We should also keep in mind an early plastic surgeon or hand surgeon consultation for evaluation of all extravasation events that develop symptoms of CS of the hand, regardless of the volume of the extravasation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

References

- 1. Bellin MF, Jakobsen JA, Tomassin I, Thomsen HS, Morcos SK, Thomsen HS, et al. Contrast medium extravasation injury: guidelines for prevention and management. Eur Radiol 2002;12:2807–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Belzunegui T, Louis CJ, Torrededia L, Oteiza J. Extravasation of radiographic contrast material and compartment syndrome in the hand: a case report. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2011;19:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. D'Asero G, Tati E, Petrocelli M, Brinci L, Palla L, Cerulli P, et al. Compartment syndrome of the hand with acute bullous eruption due to extravasation of computed tomography contrast material. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2010;14:643–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mandlik V, Prantl L, Schreyer A. Contrast media extravasation in CT and MRI - a literature review and strategies for therapy. Rofo 2019;191:25–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Veelen NM, Link BC, Donner G, Babst R, Beeres FJP. Compartment syndrome of the forearm caused by contrast medium extravasation: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Imaging 2020;61:58–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rubinstein AJ, Ahmed IH, Vosbikian MM. Hand compartment syndrome. Hand Clin 2018;34:41–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Loth TS, Jones DE. Extravasations of radiographic contrast material in the upper extremity. J Hand Surg Am 1988;13:395–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Selek H, Özer H, Aygencel G, Turanlı S. Compartment syndrome in the hand due to extravasation of contrast material. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2007;127:425–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Grand A, Yeager B, Wollstein R. Compartment syndrome presenting as ischemia following extravasation of contrast material. Can J Plast Surg 2008;16:173–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ensat F, Babl M, Spies M. Acute compartment syndrome of the forearm after paravasation of contrast medium. Case Rep Radiol 2010;50:272–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Güner S, Ceylan MF, Avcu S, Güner Sİ, Doğan A. Compartment syndrome due to extravasation of iodixanol contrast medium: case report. Turkiye Klinikleri J Med Sci 2012;32:248–51. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Altan E, Tutar O, Şenaran H, Aydın K, Acar MA, Yalçın L. Forearm compartment syndrome of a newborn associated with extravasation of contrast agent. Case Rep Orthop 2013;2013:638159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yurdakul E, Salt Ö, Durukan P, Duygulu F. Compartment syndrome due to extravasation of contrast material: a case report. Am J Emerg Med 2014;32:1155.e3–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Vinod KV, Shravan R, Shrivarthan R, Radhakrishna P, Dutta TK. Acute compartment syndrome of hand resulting from radiographic contrast iohexol extravasation. J Pharmacol Pharmacother 2016;7:44–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stavrakakis IM, Daskalakis II, Detsis EPS, Karagianni CA, Papantonaki SN, Katsafarou MS. Hand compartment syndrome as a result of intravenous contrast extravasation. Oxf Med Case Reports 2018;12:425–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]