Abstract

Objectives

While risk factors of bisphosphonate (BP) associated osteonecrosis of the jaw have been properly analyzed, studies focusing on risk factors associated with denosumab (DNO) are sparse. The purpose of this study was to identify risk factors influencing the onset of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ) in patients receiving antiresorptive treatment (ART) with DNO by comparing patients suffering from MRONJ and patients without MRONJ. Multiple variables were evaluated including the impact of a previous BP intake.

Materials and methods

A retrospective single-center cohort study with patients receiving DNO was conducted. One-hundred twenty-eight patients were included and divided into three groups: I (control, n = 40) receiving DNO with absence of MRONJ; group II (Test 1, n = 46), receiving DNO with presence of MRONJ; and group III (Test 2, n = 42) sequentially receiving BP and DNO with presence of MRONJ. Patients’ medical history, focusing on the identification of MRONJ risk factors, was collected and evaluated. Parameters were sex, age, smoking habit, alcohol consumption, underlying disease (cancer type, osteoporosis), internal diseases, additional chemo/hormonal therapy, oral inflammation, and trauma.

Results

The following risk factors were identified to increase MRONJ onset significantly in patients treated with DNO: chemo/hormonal therapy (p = 0.02), DNO dosage (p < 0.01), breast cancer (p = 0.03), intake of corticosteroids (p = 0.04), hypertension (p = 0.02), diabetes mellitus (p = 0.04), periodontal disease (p = 0.03), apical ostitis (p = 0.02), and denture use (p = 0.02). A medication switch did not affect MRONJ development (p = 0.86).

Conclusions

Malignant diseases, additional chemotherapy, DNO dosage, and oral inflammations as well as diabetes mellitus and hypertension influence MRONJ onset in patients treated with DNO significantly.

Clinical relevance

Patients receiving ART with DNO featuring aforementioned risk factors have a higher risk of MRONJ onset. These patients need a sound and regular prophylaxis in order to prevent the onset of MRONJ under DNO treatment.

Keywords: MRONJ, Osteonecrosis of the jaw, Risk factors, Bisphosphonates, Denosumab

Introduction

Medication-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ) is a rare but severe adverse side effect of an antiresorptive therapy (ART). Initially described as being associated with the intake of bisphosphonates (BP) [1, 2], it became obvious that other antiresorptive drugs such as denosumab (DNO) have also the risk of inducing MRONJ [3–5]. Increasing tumor incidences, longer patient survival, adjuvant antiresorptive therapy strategies, and rising numbers of first-line regimes for osteoporosis are turning MRONJ into a disease of increasing importance [6–8].

Interestingly, both the pharmacological mechanisms and pharmacokinetics of BP and DNO are markedly different: BP are admitted orally or intravenously and accumulate in bone by selectively binding to hydroxyapatite. In the soluble phase when released from bone in an acidic milieu, BP molecules interfere intracellularly in the mevalonate pathway and inactivate various cell types but in particular osteoclasts [9]. DNO, in contrast, is a human monoclonal antibody that selectively binds to the RANK ligand, a key cytokine for the differentiation, maturation, and activation of osteoclasts. Subcutaneously admitted DNO is inactivated by the immune system within weeks as other allogenic antibodies and does not accumulate in the body.

Both drugs have an osteoclast suppressing effect in common. Thus, conditions in which osteoclast activity is essentially needed (such as local bone inflammation processes of the jaws or bone remodeling after tooth extraction) may not be overcome and can lead to an osteonecrosis. While this pathogenesis theory is widely accepted [10–12] there are additional risk factors associated with MRONJ onset. Risk factors for BP therapy have previously been described in several studies (see Table 1). To date, however, only limited data with small sample sizes are available focusing on the impact of certain risk factors associated with DNO intake [13].

Table 1.

Availability of data concerning risk factors associated with MRONJ in patients treated with DNO compared to BP and sequentially with both drugs

| Variable | Denosumab references | Denosumab/bisphosphonate reference | Bisphosphonate references | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic factors | Sex | [13] | [14] | [15, 16] |

| Age | [13] | * | [15, 16] | |

| Smoking habit | [13] | * | [15, 17–19] | |

| Alcohol consumption | [13] | * | [15, 17–19] | |

| Medical comorbidities | Cancer type | [13, 14] | [14] | [15, 16, 18–23] |

| Osteoporosis | [13, 14] | [14] | [15, 16, 18, 20, 24] | |

| Diabetes mellitus | [13] | [14] | [15, 16, 18, 20, 25] | |

| Diseases of cardio-vascular system | * | * | [16, 18] | |

| Hypertension | * | [14] | [16, 18, 21] | |

| Renal disease | * | * | [16, 18] | |

| Gastrointestinal disease | * | * | [16, 18] | |

| Thyroid malfunctions | * | [14] | [16, 18] | |

| Rheumatic diseases | * | [14] | [16, 18, 22] | |

| Infectious diseases | * | * | [16, 18, 22] | |

| Co-medication associated with underlying disease | Chemotherapy | [13] | [14] | [1, 15, 22, 24, 26] |

| Molecular targeted therapy | [13] | [14] | [1, 15, 18–20, 22, 24, 26] | |

| Corticosteroid therapy | [13] | [14] | [1, 18–20, 22, 24, 26] | |

| Hormonal therapy | [13] | * | [1, 15, 22, 24, 26] | |

| Dental comorbidities | Extraction | [14] | [14] | [1, 15–25, 27–29] |

| Periodontal disease | [13] | [14] | [15–18, 21, 27] | |

| Apical ostitis | [13] | [14] | [15, 17, 20, 23, 27, 30] | |

| Retained root | * | * | [15, 17] | |

| Dental cysts | * | * | [15, 17, 30] | |

| Dental implants | [31] | [14] | [15–17, 23, 32–34] | |

| Endodontic treatment | * | * | [35, 36] | |

| Use of dentures | [13] | [14] | [15–18, 21, 27] | |

| Trauma | * | * | [37, 38] | |

| Poor oral hygiene | * | [14] | [15–18, 20, 21, 23, 27] |

*To our knowledge, few data (mostly case reports or studies with small cohorts) exist concerning these risk factors. Of note, the sample size of [13] was n = 14

Identification of risk factors could improve prophylaxis and prevention of MRONJ. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to find out other risk factors inducing the onset of MRONJ in patients receiving antiresorptive treatment with DNO.

The authors hypothesize that (I) certain demographic, co-medications, and oral-health factors influence the onset of MRONJ; (II) the switch from a previous BP intake to DNO intake furthermore influences the onset of MRONJ; and (III) that the presence of dental implants at the start of ART elevates the risk of MRONJ onset.

The specific aims of this study were to estimate (I) which factors, derived from patients medical history, influence MRONJ onset; (II) whether a combination of DNO/BP treatment elevates the risk of MRONJ onset; and (III) whether the presence of dental implants would impact MRONJ incidence.

Patients and methods

This study was approved by the local medical association authority (Bayerische Landesärztekammer, ethic committee number: 2020–1228) and was carried out according to the Declaration of Helsinki 7th revision of 2013.

Study design

We designed and implemented a retrospective single-center cohort study and consecutively enrolled a sample derived from the source population of subjects who were treated at the Department “Medicine and Aesthetics,” Clinic for Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Munich, between 2011 and 2020, and fulfilled a predefined selection protocol with the following inclusion criteria: (1) antiresorptive therapy (ART) with at least one or more doses of DNO in patients’ medical history, (2) presence of MRONJ (for groups II and III) according to criteria for MRONJ according to the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery (AAOMS) [39], (3) availability of panoramic dental X-ray, (4) follow-up examinations of at least 12 months, and (5) complete medical history including co-medication.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) history of irradiation in the head and neck region, (2) metastatic bone disease of the maxillofacial region, (3) missing follow-up examinations, (4) missing panoramic dental X-ray, and (5) missing information in the medical history.

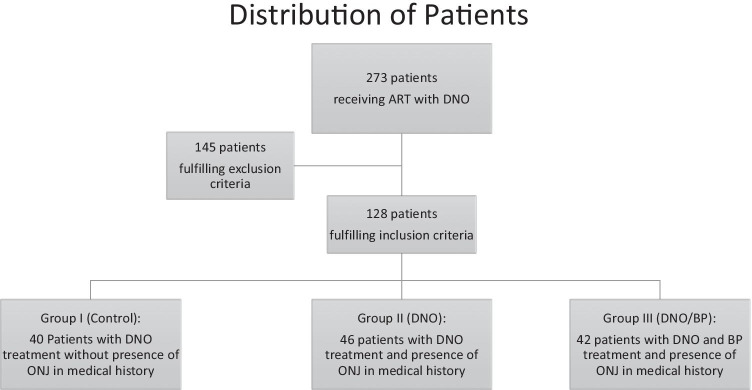

All patients fulfilling inclusion criteria were consecutively divided into three groups, according to patient’s medical history: group I (control), DNO treatment and no presence of MRONJ; group II (Test 1, DNO), DNO treatment with presence of MRONJ; and group III (Test 2, DNO/BP), switch of ART from BP to DNO with presence of MRONJ (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of patient distribution into three groups

Study variables

The study variables were as follows: presence of MRONJ in patient’s medical history (yes/no), demographic factors (age at last clinical examination, sex, duration of follow-up, smoking habits, and alcohol consumption), underlying disease requiring ART (cancer type and/or osteoporosis, bone metastasis, and time since initial diagnosis of underlying disease), ART type of medication (duration of medication and medication switch), co-medication associated with underlying disease (chemotherapy or molecular targeted therapy, corticosteroid therapy, hormonal therapy, and antiangiogenic therapy), MRONJ (time since initial diagnosis of MRONJ, location, and surgical therapy), additional medical history (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, diseases of cardio-pulmonary system, thyroid malfunctions, rheumatic diseases, and infectious diseases), and intraoral findings (number of teeth, retained root, presence of dental implants prior to ART, periodontal disease, apical periodontitis, dental cysts, denture use, and presence of current dental procedure in area of MRONJ) (see Table 1).

Primary and follow-up examinations

Patients not yet treated with DNO were referred to Medicine and Aesthetics by different regional oncologists and osteologists, prior to ART, for primary examination to assess oral health status. Patients’ medical records on underlying disease, ART, medical comorbidities and co-medications, and oral findings were evaluated. Additionally, a panoramic X-ray was performed, and mucosal integrity and periodontal diseases were evaluated according to the European Federation of Periodontology guidelines [40].

With absence of MRONJ these patients underwent yearly (12 months) follow-up examinations undergoing the same examination. If required prophylactic treatment was performed according to the 2018 German MRONJ guidelines [41] and consisted of extraction of non-preservable and periodontally compromised teeth and dental implants, the excision of dental cysts and foreign bodies, and the reduction of denture-associated sore spots.

Patients with onset of MRONJ were referred to Medicine and Aesthetics either by the same oncologists and osteologists or by their dentists initially discovering exposed bone or MRONJ lesions. Most patients presenting MRONJ received surgical treatment following the same therapeutic standardized protocol as recently described [42]. Follow-up examinations in cases of MRONJ were conducted quarterly (3 months). All examinations were conducted by the same investigators (CP, BHM, AW, PB). Surgery was performed by one and the same oral and maxillofacial surgery specialist (CP). When extraction of non-preservable or periodontally compromised teeth and dental implants was necessary under ongoing DNO therapy, procedures were again performed accordingly to the 2018 German MRONJ guidelines [41]. Treatment consisted essentially of minimally invasive techniques with consecutive smoothing of sharp bone edges, complete mucoperiostal closure, and perioperative antibiotic therapy (amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 875/125 mg 1–0-1, in case of allergy: clindamycin 600 mg 1–1-1, starting 1 week preoperatively and continuing for up to 3 weeks postoperatively) as well as a weekly follow-up in the first 4 weeks.

There was no recommendation for discontinuation of ART (drug holiday) by the investigators of this study, but in few cases (see Tables 1 and 2) ART was paused by the prescribing osteologists and/or oncologists at the time of first consultation in our clinic.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics and demographics

| Variables | n (%) or median [range] | |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic factors | Male | 49 (38.3%) |

| Female | 79 (61.7%) | |

| Age (years) | 72.2 [61.9–80.1] | |

| Duration of follow-up (months) | 14.0 [12.7–20.2] | |

| Smoking habit | 24 (18.8%) | |

| Alcohol consumption | 21 (16.4%) | |

| Underlying disease | Osteoporosis | 57 (44.5%) |

| Cancer | 86 (67.2%) | |

| Breast | 40 (31.3%) | |

| Prostate | 31 (24.2%) | |

| Other | 15 (11.7%) | |

| Bone metastasis | 86 (67.2%) | |

| Time since initial diagnosis of underlying disease (years) | 9.0 [6.0–14.3] | |

| Antiresorptive therapy | Denosumab | 128 (100%) |

| 120 mg | 78 (60.9%) | |

| 60 mg | 50 (39.1%) | |

| Bisphosphonates | 42 (32.8%) | |

| Zoledronate | 21 (16.4%) | |

| Ibandronate | 14 (10.9%) | |

| Other | 7 (5.5%) | |

| Duration of medication (months) | 38.7 [22.9–59.2] | |

| Co-medication associated with underlying disease | Chemotherapy or molecular targeted therapy | 37 (28.9%) |

| Corticosteroid therapy | 7 (5.5%) | |

| Hormonal therapy | 24 (18.8%) | |

| Antiangiogenic therapy | 5 (3.9%) | |

| Osteonecrosis of the jaw | Presence of MRONJ | 88 (68.8%) |

| Time since initial diagnosis of MRONJ (years) | 3.0 [1.7–5.1] | |

| Location of MRONJ | Upper jaw: 31 (32.0%) | |

| Lower jaw: 66 (68.0%) | ||

| Drug holiday | 13 (10.2%) | |

| Surgical therapy | 81 (92.0%) | |

| Medical history | Hypertension | 43 (33.6%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 8 (6.3%) | |

| Diseases of cardio-pulmonary system | 49 (38.3%) | |

| Thyroid malfunctions | 29 (22.7%) | |

| Rheumatic diseases | 10 (7.8%) | |

| Infectious diseases | 1 (0.8%) | |

| Intraoral findings | Number of teeth | 2211 (100%) |

| 20.0 [11.3–25.0] | ||

| Upper jaw | 10.0 [4.0–12.0] | |

| Lower jaw | 11.0 [6.0–13.0] | |

| Retained root | 5 (3.9%) | |

| Patients with dental implants prior to ART | 34 (26.6%) | |

| Number of dental implants | 139 (6.3%)* | |

| Periodontal disease | 88 (68.8%) | |

| Apical periodontitis | 48 (37.5%) | |

| Dental cysts | 5 (3.9%) | |

| Denture use | 52 (40.6%) | |

| Dental procedures | 60 (46.8%) |

*Percentage measured according to absolute number of teeth

Data acquisition and analysis

Data acquisition was performed retrospectively and derived from patients’ medical records in a yes/no manner according to the previously performed primary and follow-up examinations (see Table 2).

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS Version 21 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) as well as R Version 4.0.3. Initially all non-nominal data were analyzed for normal distribution applying a Kolmogorov–Smirnov test.

The statistical differences between the three groups were evaluated using T-test, Chi-square test, and ANOVA or Kruskal–Wallis test with post hoc analysis applying a Bonferroni test. Analysis of certain risk factors for the development of MRONJ was furthermore conducted by applying logistic regression.

Patient cohort and characteristics

In total, 273 individuals were identified as having received ART with DNO, 145 patients met one or more exclusion criteria and were excluded from this study (see Fig. 1), and 128 patients met the inclusion criteria. The median follow-up on 31 December 2020 (end of data acquisition) was 14.0 [12.7–20.2] months with a maximum follow-up time of 80 and a minimum of 12 months (see Table 1).

Most of the patients in our cohort suffered from stage IV cancer (of which breast and prostate cancer were the prominent malignant diseases) followed by osteoporosis. All cancer patients had at least one or multiple skeletal metastases. The median time since initial diagnosis of underlying disease was 9 years.

Patients received most frequently DNO in the dosage 120 mg in 60.9%, 37 patients (28.9%) patients received chemotherapy or molecular targeted therapy, 24 patients (18.8%) were treated with a hormonal therapy. Seven patients (5.5%) received an additional corticosteroid therapy, 5 patients (3.9%) received antiangiogenic therapy, and 42 patients (32.8%) had received ART with BP before DNO treatment (see Fig. 1).

The main variable MRONJ was present in 88 patients (68.8%) with a median time since initial diagnosis of MRONJ of 3 years. MRONJ was found in the upper jaw in 31 cases (32.0%), in 66 cases (68.0%) in the lower jaw, and in 9 patients (7.0%) in both jaws. Surgical therapy of MRONJ lesions was performed in 81 cases (92.0%). A discontinuation of ART at the time of the dental procedure was performed in 13 cases (10.2%). Of note, the investigators of the study gave no recommendation on drug holiday. The ART prescribing physician initiated the drug holiday.

The most frequent co-morbidities were diseases of cardio-pulmonary system hypertension in 49 patients (38.3%), followed by arterial hypertension in 43 patients (33.6%), thyroid malfunctions in 29 patients (22.7%), rheumatic diseases in 10 patients (7.8%), and diabetes mellitus in 8 patients (6.3%).

Intraoral findings presented a total number of 2211 teeth with a median of 10 in the upper and 11 in the lower jaw. Five patients (3.9%) had a retained root, 88 patients (68.8%) revealed moderate to severe periodontal disease, 48 patients (37.5%) had apical periodontitis, 5 patients (3.9%) had dental cysts, and 52 patients (40.6%) were using removable dentures. In 60 patients (46.8%) dental surgical procedures were performed. A total of 139 dental implants prior to ART were found in 34 patients (26.6%) with a median of 3 implants per patient (see Table 2).

The cohort was divided into three groups dependent on the presence of MRONJ and the antiresorptive medication:

Group I (control): n = 40 15 males (37.5%) and 25 females (62.5%) with a median age of 69.8 years. Three patients (6.6%) had died until the end of data acquisition.

Group II (Test 1, DNO): n = 46 patients with 49 MRONJ lesions, 20 males (43.5%) and 26 females (56.5%) with a median age of 75.1 years. Four patients (9.5%) had died until the end of data acquisition.

Group III (Test 2, DNO/BP): n = 42 patients with 48 MRONJ lesions, 14 males (33.3%) and 28 females (66.7%) with a median age of 70.8 years. Two patients (4.4%) had died until the end of data acquisition.

To further display patient characteristics and demographics of patients with MRONJ onset and those with MRONJ absence, Table 3 demonstrates parameter distribution in groups I, II, and III.

Table 3.

Comparison of patient characteristics and demographics within groups

| n (%) or median [range] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Group I (control) (n = 40) | Group II (Test 1, DNO) (n = 46) | Group III (Test 2, DNO/BP) (n = 42) | |

| Demographic factors | Male | 15 (37.5%) | 20 (43.5%) | 14 (33.3%) |

| Female | 25 (62.5%) | 26 (56.5%) | 28 (66.7%) | |

| Age (years) | 69.8 [61.3–80.4] | 75.1 [63.5–83.8] | 70.8 [61.8–76.3] | |

| Duration of follow-up (months) | 13.6 [12.5–20.9] | 13.3 [12.8–18.2] | 16.2 [13.4–24.1] | |

| Smoking habit | 4 (10.0%) | 9 (19.6%) | 11 (26.2%) | |

| Alcohol consumption | 4 (10.0%) | 8 (17.4%) | 9 (21.4%) | |

| Underlying disease | Osteoporosis | 27 (58.7%) | 14 (27.5%) | 16 (34.8%) |

| Cancer | 19 (41.3%) | 37 (72.5%) | 30 (65.2%) | |

| Breast | 7 (36.8%) | 15 (40.5%) | 18 (60.0%) | |

| Prostate | 9 (47.4%) | 13 (35.1%) | 9 (30.0%) | |

| Lung | 0 | 2 (5.4%) | 0 | |

| Kidney | 0 | 3 (8.1%) | 0 | |

| Other | 3 (15.8%) | 4 (10.8%) | 3 (10.0%) | |

| Bone metastasis | 19 (41.3%) | 37 (72.5%) | 30 (65.2%) | |

| Time since initial diagnose of underlying disease (years) | 6.5 [3.5–10.5] | 8.2 [5.1–12.0] | 10.5 [8.6–15.1] | |

| Antiresorptive therapy | Denosumab | 40 (100%) | 46 (100%) | 42 (100%) |

| 120 mg | 13 (32.5%) | 35 (76.1%) | 30 (71.4%) | |

| 60 mg | 27 (67.5%) | 11 (23.9%) | 12 (28.6%) | |

| Bisphosphonates | No BP | No BP | 42 (100%) | |

| Zoledronate | 21 (50.0%) | |||

| Alendronate | 5 (11.9%) | |||

| Ibandronate | 14 (33.3%) | |||

| Other | 2 (4.8%) | |||

| Duration of medication (months) | 35.8 [18.5–47.6] | 35.3 [23.4–58.1] | 47 [24–66.9] | |

| Co-medication associated with underlying disease | Chemotherapy or molecular targeted therapy | 7 (17.5%) | 18 (39.1%) | 16 (38.1%) |

| Corticosteroid therapy | 0 | 6 (13.0%) | 2 (4.8%) | |

| Hormonal therapy | 2 (5.0%) | 13 (28.3%) | 9 (21.4%) | |

| Antiangiogenic therapy | 0 | 1 (2.2%) | 4 (9.5%) | |

| Osteonecrosis of the jaw | Presence of MRONJ | No MRONJ | 46 (100%) | 42 (100%) |

| Time since initial diagnosis of MRONJ | 2.6 [1.8–4.3] | 3.7 [1.7–5.6] | ||

| Location of MRONJ | Upper jaw: 15 (30.6%) | Upper jaw: 16 (33.3%) | ||

| Lower jaw: 34 (69.4%) | Lower jaw: 32 (66.7%) | |||

| Surgical therapy | 42 (91.3%) | 39 (92.9%) | ||

| Drug holiday | 8 (20.0%) | 3 (6.5%) | 2 (4.8%) | |

| Medical history | Hypertension | 8 (20.0%) | 21 (45.7%) | 16 (38.1%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0 | 6 (13.0%) | 2 (4.8%) | |

| Diseases of cardio-pulmonary system | 12 (30.0%) | 20 (43.5%) | 17 (40.5%) | |

| Thyroid malfunctions | 9 (22.5%) | 15 (32.6%) | 5 (11.9%) | |

| Rheumatic diseases | 4 (10.0%) | 3 (6.5%) | 3 (7.1%) | |

| Infectious diseases | 1 (2.5%) | 0 | 0 | |

| Intraoral findings | Number of teeth | 24 [13.3–26.8] | 19 [7.3–24] | 20 [12–23] |

| Upper Jaw | 11 [5–14] | 8 [4–11] | 9.5 [5.3–12] | |

| Lower Jaw | 12 [8.5–14] | 10 [4.3–12] | 10.5 [6–12] | |

| Retained root | 0 | 1 (2.2%) | 4 (9.5%) | |

| Dental implants prior to ART | 3 [2.0–6.3] | 2.5 [2–3.8] | 4 [3–5] | |

| Periodontal disease | 22 (55.0%) | 35 (76.1%) | 31 (73.8%) | |

| Apical periodontitis | 12 (30.0%) | 18 (39.1%) | 23 (54.8%) | |

| Dental cysts | 2 (5.0%) | 1 (2.2%) | 2 (4.8%) | |

| Denture use | 10 (25.0%) | 27 (58.7%) | 15 (35.7%) | |

| Dental procedures | 18 (45.0%) | 22 (47.8%) | 20 (47.6%) | |

Results

To assess which parameters influence the onset of MRONJ in patients treated with DNO, each of the above mentioned parameters was initially compared with the parameter “presence of ONJ” (Yes/No) applying chi-square and T-tests.

Statistically significant differences in patients with MRONJ absence (control) and patients with MRONJ presence (groups II and III) were found in the parameters underlying disease (p = 0.01), DNO dosage (p < 0.01), co-medications (chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, etc.) (p = 0.05), vascular diseases (p = 0.04), and dental inflammations.

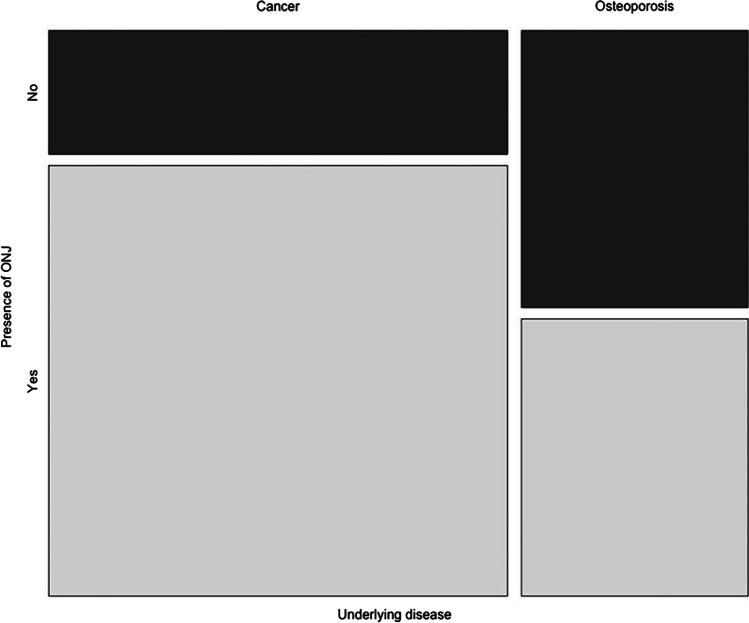

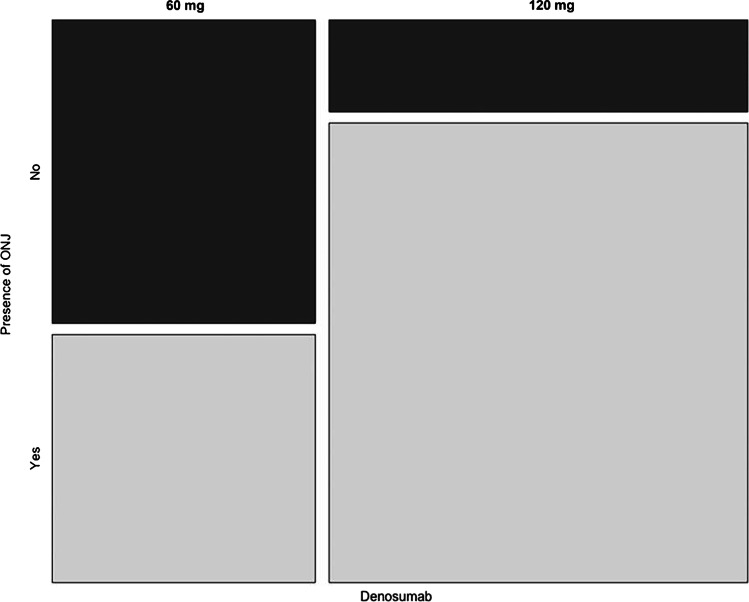

Exemplary the parameters underlying disease and DNO dosage are displayed as mosaic plots. Patients suffering from cancer (n = 86) as underlying disease showed a significantly higher presence of MRONJ (p < 0.01) compared to patients suffering from osteoporosis (n = 56) (see Fig. 2). Patients receiving high-dose (120 mg) DNO (n = 78) presented more onset of MRONJ compared to patients receiving low-dose (60 mg) DNO (n = 50) (see Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Mosaic plot: underlying disease vs. presence of MRONJ

Fig. 3.

Mosaic plot: DNO dosage vs. presence of MRONJ

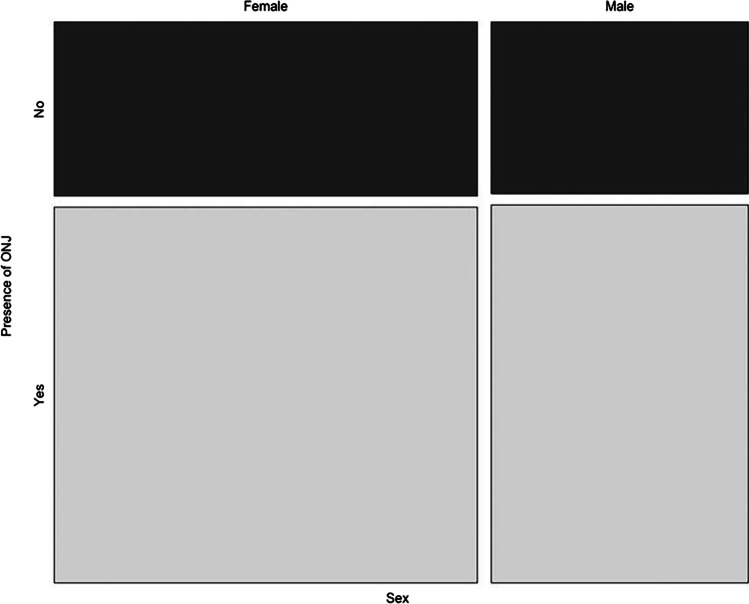

Even though there were significantly more women (n = 79) than men (n = 49) included in this study, the variable “sex” was not identified as a risk factor and MRONJ onset was distributed equally for both genders (see Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Mosaic plot: sex vs. presence of MRONJ

To further define risk factors, these previously identified parameters were analyzed performing logistic regression. The variable duration of ART (OR 1.07 [1.00–1.13], p = 0.04), breast cancer (OR 2.83 [1.12–7.12], p = 0.03), chemotherapy or molecular targeted therapy (2.97 [1.18–7.46], p = 0.02), hormonal therapy (6.33 [1.41–28.43], p = 0.02), hypertension (2.96 [1.22–7.16], p = 0.02), periodontal disease (2.46 [1.12–5.40], p = 0.03), apical ostitis (2.04 [0.92–4.51], p = 0.02), and use of dentures (2.74 [1.20–6.28], p = 0.02) presented significant predictors of MRONJ onset with an odds ratio larger than 1 (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Risk factors for MRONJ onset in logistic regression analyses

| Variables | Odds ratio [CI] | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Duration of ART | 1.07 [1.00–1.13] | 0.037 |

| Breast cancer | 2.83 [1.12–7.12] | 0.027 |

| Chemotherapy | 2.97 [1.18–7.46] | 0.021 |

| Hormonal therapy | 6.33 [1.41–28.43] | 0.016 |

| Hypertension | 2.96 [1.22–7.16] | 0.016 |

| Periodontal disease | 2.46 [1.12–5.40] | 0.026 |

| Apical ostitis | 2.04 [0.92–4.51] | 0.018 |

| Denture use | 2.74 [1.20–6.28] | 0.017 |

CI confidence interval, p significance

The variables drug holiday (OR 0.24 [0.07–0.79], p = 0.02) and presence of dental implants prior to ART (0.85 [0.189–1.018], p = 0.04) however were identified to decrease the risk of MRONJ onset in this study (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Factors decreasing the risk of MRONJ in logistic regression analyses

| Variables | Odds ratio [CI] | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Drug holiday | 0.241 [0.073–0.792] | 0.019 |

| Dental implants prior to ART | 0.846 [0.189–1.018] | 0.043 |

CI confidence interval, p significance

Discussion

The results of this study revealed that higher DNO dosage, additional chemotherapy, hormonal therapy and corticosteroid therapy, breast cancer as underlying disease, co-morbidities like hypertension and diabetes mellitus, periodontal disease and apical periodontitis, and the use of dentures elevate the risk of MRONJ onset in patients treated with DNO. A minor effect was also associated with prolonged intake of DNO.

When comparing the afore mentioned risk factors for onset of MRONJ in patients treated with DNO and those previously described for onset of MRONJ in patients treated with BP (see Table 1) it becomes clear that these findings correlate well. Considering the different pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of BP and DNO, this underlines the importance of inflammatory processes as the main triggering events [11, 15] in the development of MRONJ.

Risk factors

For BP it was shown that co-medications such as chemotherapy or corticosteroid therapy alongside local risk factors, e.g., dental procedures, apical ostitis, and periodontal disease, presented a significant impact on the onset of MRONJ [15, 23, 39, 43]. The female gender as well as breast cancer as an underlying disease were also identified as having a predilection for MRONJ [44–48].

In a recent study patients under DNO therapy with absence and presence of MRONJ were compared [13]; however, the sample size with n = 14 was limited. The number of patients in the present study was considerably higher and an additional investigation group was added: patients under antiresorptive therapy with a medication switch from BP to DNO and the presence of MRONJ. The three investigated groups presented statistically significant differences in regard to the underlying disease, the dosage of DNO, co-medications, additional diseases, and intraoral findings.

The number of patients suffering from stage IV cancer was significantly higher in both MRONJ groups (DNO and DNO/BP) compared to the control group whose population predominantly suffered from osteoporosis. This result is concordant to the dosage of DNO distributed among the groups: high-dose DNO (120 mg) was mainly found in the MRONJ groups, whereas low-dose DNO (60 mg) was the main DNO derivate in the control group with no onset of MRONJ. The results of this study suggest that higher doses of DNO elevate the risk of MRONJ.

Co-medications such as chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, and corticosteroid therapy pose a significant risk to the development of DNO associated MRONJ. This can be explained by the fact that these medications might lead to immunosuppression and thus, indirectly, alter the risk of local inflammation and consecutively the onset of MRONJ. Breast cancer as an underlying disease was also associated with an elevated MRONJ risk [48–50].

Hypertension and with less impact also diabetes mellitus as vascular diseases were also identified as risk factors. An impaired vascular system decreases the blood circulation of bone structures particularly of bones with exceptional blood supply as well as a high proportion of cortical structures such as the lower jaw [15] and thus possibly abating the onset of MRONJ.

Periodontal disease, apical periodontitis, and the use of dentures were shown to elevate the risk of MRONJ. This is concordant with the theory of inflammation as a key factor in the pathogenesis of MRONJ. On the one hand mucosal inflammation due to periodontal diseases and denture-associated sore spots pose a continuous stimulus on mucosal integrity. Micro-lesions in mucosa and periodontal apparatus thus enable oral bacteria to penetrate into the bone and cause local inflammation [51]. Due to the reduced osteoclast activity under ART the defense ability towards bone infections is markedly reduced. These observations support the hypothesis that local inflammations are of paramount importance in the pathogenesis of MRONJ [18, 25, 52].

Even though regular consumption of alcohol and smoking did not pose significant risk factors for MRONJ in this study, they are clear risk factors for oral diseases, e.g., periodontal disease and impaired wound healing, thus indirectly favoring the development of MRONJ [53].

These findings correlate well with those of the few other studies we found. Okuma et al. [13] furthermore showed that prolonged DNO intake and sex influence onset of MRONJ. In this study prolonged intake of DNO did only present a mild risk of MRONJ. It is however a logical consequence that longer DNO application adds to the likelihood of triggering events taking place. This is in line with the findings of other studies demonstrating that prolonged intake of DNO significantly increased the development of MRONJ [38, 54]. As for sex, it is readily assumed that gender may present a risk factor; however, it needs to be considered that mainly female patients are affected by breast cancer and osteoporosis [22] and thus shift the balance of patients receiving ART to the female gender.

Dental implants

Taking a closer look at dental implants as a risk factor for increased MRONJ onset in patients treated with BP results are ambiguously, if not contrary. In a recent overview evaluating several studies on the impact of dental implants on the onset of MRONJ, dental implants were identified as a risk factor [55]. The same conclusion was drawn from another working group by Jacobsen et al. [56] showing that dental implants were risk factors for MRONJ onset in patients treated with BP, whereas in a Korean cohort, these results could not be confirmed by Ryu, Kim, and Kwon [31].

To our knowledge, the impact of dental implants in patients treated with DNO has been scarcely investigated [14] and was therefore a key finding of this study. When applying logistic regression (see Table 5) it was revealed that the presence of dental implants prior to ART did not increase but instead decrease the risk of MRONJ onset in patients treated with DNO. This finding could be related to a potentially better oral hygiene in patients caring for the dental implants compared to those without dental implants, as those patients with dental implants prior to ART presented fewer cases of periodontitis in this study. Whatever the reason may be, we can assert from this study that the presence of dental implants prior to ART does not impact onset of MRONJ negatively. Periimplantitis, as a risk factor for MRONJ, seems to be as significant as periodontitis and should be avoided just as much in patients at risk. A poor oral hygiene appears to have a significant impact on the development of MRONJ in patients treated with DNO just as it has been reported in those patients treated with BP [7, 15].

Medication switch

The assumed impact of a medication switch from BP to DNO did not however influence MRONJ onset. When compared to one another, groups II (DNO) and III (DNO/BP) did not show an increased MRONJ risk or a significant difference in risk factors. A similar result has been reported in a previous study by the same investigators as of this study [42]. In afore mentioned study it was also shown that a medication switch did neither influence the time to onset of MRONJ nor the outcome after surgical MRONJ therapy negatively.

Drug holiday

The number of patients receiving a drug holiday in this study was relatively low, and these findings should be evaluated with care. A finding of this study was that the risk of MRONJ could be reduced by more than 75% in patients undergoing a drug holiday around dental procedures. A large prospective study would be advisable for future studies addressing this aspect.

The appliance of a drug holiday is widely discussed. Osteologists and oncologists [24, 57, 58] often advise not to pause ART even for a short term as the onset of skeletal related events (SRE) may yet occur. A meta-analysis of multiple studies concerning drug holidays has shown that a drug holiday does not reduce risk of MRONJ [55]. However, most studies in this meta-analysis focused on BP not on DNO. Two studies addressed the influence of a DNO drug holiday on the wound healing after the onset of MRONJ [14, 59]. Regarding the pharmacological differences between BP and DNO a short-termed DNO drug holiday surrounding a possible triggering event, like tooth extraction, could very well decrease the risk of MRONJ.

Discontinuation of DNO

There was no recommendation from the authors to discontinue the antiresorptive therapy neither for BP nor for DNO. However, in several cases the ART was stopped by the prescribing oncologist/practitioner. Due to the fact that the pharmacological effect of denosumab attenuates within weeks there is a substantiation for a drug holiday. Nevertheless, the decision for a discontinuation should be an interdisciplinary one. There are no recommendations in the German guidelines for prostate carcinoma, breast cancer, or multiple myeloma for the discontinuation of ART with DNO [60–62].

Limitations

The limitation of the present study is the small sample size evaluated. Due to the retrospective character of this study, inclusion in the study was defined after a predefined period of time. However, for further evidence the present data can be used for power estimations of a prospective trial in the future. Another limitation is the heterogeneous intake of antiresorptive medication, underlying disease, and immunomodulatory co-medications. Nevertheless, the application of multifactorial regression models (considering covariance as medication types and/or underlying disease) should be the aim in subsequent confirmatory studies. Of note, it will be increasingly difficultly to find pure intervention groups in the future. This might be progressively part of the discussion when performing MRONJ studies. However, we tried our best to create large and comparable study groups, all of whom were operated on by the same surgeon and followed regular check-ups.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the results of this study revealed statistically significant correlations of the onset of MRONJ in patients treated with DNO in patients receiving higher DNO dosage, additional chemotherapy, hormonal therapy and corticosteroid therapy, those suffering from breast cancer, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, periodontal disease and apical periodontitis, and those using dentures. A minor effect was associated with prolonged intake of DNO.

These findings correlate well with risk factors associated with MRONJ onset in patients treated with BP. MRONJ onset is a multi-factorial event that occurs in patients receiving BP as well as those treated with DNO despite the medication’s different pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic mechanisms. This underlines the importance of inflammatory processes as the main triggering event in the development of MRONJ. Concluding that prophylactic treatment prior to DNO application as well as regular oral examinations and carefully performed dental procedures after DNO application are fundamental elements in MRONJ prevention and patients at risk need to be educated that good dental hygiene is paramount to reduce MRONJ development.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dipl. Ing. Chris Rudolph, MSc, for the statistical support. This study is part of the doctoral thesis of Philipp Bankosegger and published with the permission of the University of Munich.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Declarations

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Informed consent

For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Marx RE. Pamidronate (Aredia) and zoledronate (Zometa) induced avascular necrosis of the jaws: a growing epidemic. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61:1115. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(03)00720-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Migliorati CA. Bisphosphanates and oral cavity avascular bone necrosis. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4253. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.99.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor KH, Middlefell LS, Mizen KD. Osteonecrosis of the jaws induced by anti-RANK ligand therapy. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;48:221. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2009.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aghaloo TL, Felsenfeld AL, Tetradis S. Osteonecrosis of the jaw in a patient on denosumab. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;68:959. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matsumoto A, Sasaki M, Schmelzeisen R, Oyama Y, Mori Y, Voss PJ. Primary wound closure after tooth extraction for prevention of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients under denosumab. Clin Oral Investig. 2017;21:127. doi: 10.1007/s00784-016-1762-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ristow O, Otto S, Troeltzsch M, Hohlweg-Majert B, Pautke C. Treatment perspectives for medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ) J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2015;43:290. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2014.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schiodt M, Otto S, Fedele S, Bedogni A, Nicolatou-Galitis O, Guggenberger R, Herlofson BB, Ristow O, Kofod T. Workshop of European Task Force on medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw—current challenges. Oral Dis. 2019;25:1815. doi: 10.1111/odi.13160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rugani P, Acham S, Kirnbauer B, Truschnegg A, Obermayer-Pietsch B, Jakse N. Stage-related treatment concept of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw—a case series. Clin Oral Investig. 2015;19:1329. doi: 10.1007/s00784-014-1384-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Otto S, Pautke C, Opelz C, Westphal I, Drosse I, Schwager J, Bauss F, Ehrenfeld M, Schieker M. Osteonecrosis of the jaw: effect of bisphosphonate type, local concentration, and acidic milieu on the pathomechanism. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;68:2837. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2010.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lesclous P, Abi Najm S, Carrel JP, Baroukh B, Lombardi T, Willi JP, Rizzoli R, Saffar JL, Samson J. Bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw: a key role of inflammation? Bone. 2009;45:843. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Otto S, Pautke C, Van den Wyngaert T, Niepel D, Schiodt M. Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: prevention, diagnosis and management in patients with cancer and bone metastases. Cancer Treat Rev. 2018;69:177. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2018.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ueda N, Nakashima C, Aoki K, Shimotsuji H, Nakaue K, Yoshioka H, Kurokawa S, Imai Y, Kirita T. Does inflammatory dental disease affect the development of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients using high-dose bone-modifying agents? Clin Oral Investig. 2021;25:3087. doi: 10.1007/s00784-020-03632-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okuma S, Matsuda Y, Nariai Y, Karino M, Suzuki R, Kanno T. A retrospective observational study of risk factors for denosumab-related osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients with bone metastases from solid cancers. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12:1209. doi: 10.3390/cancers12051209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aljohani S, Gaudin R, Weiser J, Troltzsch M, Ehrenfeld M, Kaeppler G, Smeets R, Otto S. Osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients treated with denosumab: a multicenter case series. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2018;46:1515. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2018.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Otto S, Schreyer C, Hafner S, Mast G, Ehrenfeld M, Sturzenbaum S, Pautke C. Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws — characteristics, risk factors, clinical features, localization and impact on oncological treatment. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2012;40:303. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McGowan K, McGowan T, Ivanovski S. Risk factors for medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaws: a systematic review. Oral Dis. 2018;24:527. doi: 10.1111/odi.12708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsao C, Darby I, Ebeling PR, Walsh K, O'Brien-Simpson N, Reynolds E, Borromeo G. Oral health risk factors for bisphosphonate-associated jaw osteonecrosis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;71:1360. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2013.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hasegawa T, Kawakita A, Ueda N, Funahara R, Tachibana A, Kobayashi M, Kondou E, Takeda D, Kojima Y, Sato S, Yanamoto S, Komatsubara H, Umeda M, Kirita T, Kurita H, Shibuya Y, Komori T. Japanese Study Group of Cooperative Dentistry with M: A multicenter retrospective study of the risk factors associated with medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw after tooth extraction in patients receiving oral bisphosphonate therapy: can primary wound closure and a drug holiday really prevent MRONJ? Osteoporos Int. 2017;28:2465. doi: 10.1007/s00198-017-4063-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Filleul O, Crompot E, Saussez S. Bisphosphonate-induced osteonecrosis of the jaw: a review of 2,400 patient cases. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2010;136:1117. doi: 10.1007/s00432-010-0907-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thumbigere-Math V, Tu L, Huckabay S, Dudek AZ, Lunos S, Basi DL, Hughes PJ, Leach JW, Swenson KK, Gopalakrishnan R. A retrospective study evaluating frequency and risk factors of osteonecrosis of the jaw in 576 cancer patients receiving intravenous bisphosphonates. Am J Clin Oncol. 2012;35:386. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e3182155fcb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saad F, Brown JE, Van Poznak C, Ibrahim T, Stemmer SM, Stopeck AT, Diel IJ, Takahashi S, Shore N, Henry DH, Barrios CH, Facon T, Senecal F, Fizazi K, Zhou L, Daniels A, Carriere P, Dansey R. Incidence, risk factors, and outcomes of osteonecrosis of the jaw: integrated analysis from three blinded active-controlled phase III trials in cancer patients with bone metastases. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:1341. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoff AO, Toth BB, Altundag K, Johnson MM, Warneke CL, Hu M, Nooka A, Sayegh G, Guarneri V, Desrouleaux K, Cui J, Adamus A, Gagel RF, Hortobagyi GN. Frequency and risk factors associated with osteonecrosis of the jaw in cancer patients treated with intravenous bisphosphonates. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:826. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.080205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aljohani S, Fliefel R, Ihbe J, Kuhnisch J, Ehrenfeld M, Otto S. What is the effect of anti-resorptive drugs (ARDs) on the development of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ) in osteoporosis patients: a systematic review. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2017;45:1493. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2017.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McClung M, Harris ST, Miller PD, Bauer DC, Davison KS, Dian L, Hanley DA, Kendler DL, Yuen CK, Lewiecki EM. Bisphosphonate therapy for osteoporosis: benefits, risks, and drug holiday. Am J Med. 2013;126:13. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peer A, Khamaisi M. Diabetes as a risk factor for medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. J Dent Res. 2015;94:252. doi: 10.1177/0022034514560768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dodson TB. The frequency of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw and its associated risk factors. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2015;27:509. doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2015.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Otto S, Troltzsch M, Jambrovic V, Panya S, Probst F, Ristow O, Ehrenfeld M, Pautke C. Tooth extraction in patients receiving oral or intravenous bisphosphonate administration: a trigger for BRONJ development? J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2015;43:847. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2015.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Groetz KA, Piesold J-U, Al-Nawas B: Bisphosphonat-assoziierte Kiefernekrose (BP-ONJ) und andere medikamenten-assoziierte Kiefernekrosen. AWMF online, 2012

- 29.Bamias A, Kastritis E, Bamia C, Moulopoulos LA, Melakopoulos I, Bozas G, Koutsoukou V, Gika D, Anagnostopoulos A, Papadimitriou C, Terpos E, Dimopoulos MA. Osteonecrosis of the jaw in cancer after treatment with bisphosphonates: incidence and risk factors. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8580. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.8670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vandone AM, Donadio M, Mozzati M, Ardine M, Polimeni MA, Beatrice S, Ciuffreda L, Scoletta M. Impact of dental care in the prevention of bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw: a single-center clinical experience. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:193. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ryu JI, Kim HY, Kwon YD: Is implant surgery a risk factor for osteonecrosis of the jaw in older adult patients with osteoporosis? A national cohort propensity score-matched study. Clin Oral Implants Res, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Walter C, Al-Nawas B, Wolff T, Schiegnitz E, Grotz KA. Dental implants in patients treated with antiresorptive medication — a systematic literature review. Int J Implant Dent. 2016;2:9. doi: 10.1186/s40729-016-0041-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shirota T, Nakamura A, Matsui Y, Hatori M, Nakamura M, Shintani S. Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw around dental implants in the maxilla: report of a case. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2009;20:1402. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2009.01801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guazzo R, Sbricoli L, Ricci S, Bressan E, Piattelli A, Iaculli F. Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw and dental implants failures: a systematic review. J Oral Implantol. 2017;43:51. doi: 10.1563/aaid-joi-16-00057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sarathy AP, Bourgeois SL, Jr, Goodell GG. Bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaws and endodontic treatment: two case reports. J Endod. 2005;31:759. doi: 10.1097/01.don.0000182737.09980.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moinzadeh AT, Shemesh H, Neirynck NA, Aubert C, Wesselink PR. Bisphosphonates and their clinical implications in endodontic therapy. Int Endod J. 2013;46:391. doi: 10.1111/iej.12018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yazdi PM, Schiodt M. Dentoalveolar trauma and minor trauma as precipitating factors for medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ): a retrospective study of 149 consecutive patients from the Copenhagen ONJ Cohort. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2015;119:416. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2014.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Almazrooa SA, Woo SB. Bisphosphonate and nonbisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw: a review. J Am Dent Assoc. 2009;140:864. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2009.0280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ruggiero SL, Dodson TB, Fantasia J, Goodday R, Aghaloo T, Mehrotra B, O'Ryan F. American Association of O, Maxillofacial S: American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons position paper on medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw—2014 update. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;72:1938. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2014.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sanz M, Herrera D, Kebschull M, Chapple I, Jepsen S, Beglundh T, Sculean A, Tonetti MS, Participants EFPW, Methodological C. Treatment of stage I-III periodontitis—the EFP S3 level clinical practice guideline. J Clin Periodontol. 2020;47(Suppl 22):4. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.13290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schiegnitz E, Al-Nawas B, Hoefert S, Otto S, Pautke C, Ristow O, Voss P, Grötz KA: S3-Leitlinie, Antiresorptiva-assoziierte Kiefernekrosen (AR-ONJ). AWMF Online 007–091, 2018

- 42.Pautke C, Wick A, Otto S, Hohlweg-Majert B, Hoffmann J, Ristow O: The type of antiresorptive treatment influences the time to onset and the surgical outcome of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. J Oral Maxillofac Surg, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.McGowan K, Ware RS, Acton C, Ivanovski S, Johnson NW. Both non-surgical dental treatment and extractions increase the risk of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: case-control study. Clin Oral Investig. 2019;23:3967. doi: 10.1007/s00784-019-02828-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stopeck AT, Lipton A, Body JJ, Steger GG, Tonkin K, de Boer RH, Lichinitser M, Fujiwara Y, Yardley DA, Viniegra M, Fan M, Jiang Q, Dansey R, Jun S, Braun A. Denosumab compared with zoledronic acid for the treatment of bone metastases in patients with advanced breast cancer: a randomized, double-blind study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:5132. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.7101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huang WW, Huang C, Liu J, Zheng HY, Lin L. Zoledronic acid as an adjuvant therapy in patients with breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e40783. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Martin M, Bell R, Bourgeois H, Brufsky A, Diel I, Eniu A, Fallowfield L, Fujiwara Y, Jassem J, Paterson AH, Ritchie D, Steger GG, Stopeck A, Vogel C, Fan M, Jiang Q, Chung K, Dansey R, Braun A. Bone-related complications and quality of life in advanced breast cancer: results from a randomized phase III trial of denosumab versus zoledronic acid. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:4841. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-3310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Diel I, Ikenberg R, Cristino J, Gatta F, Qian Y, Arellano J. Impact on hospitalization derived from the use of denosumab for the prevention of skeletal-related events in patients with bone metastases secondary to breast cancer in Germany. Value Health. 2014;17:A644. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2014.08.2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hadji P, Coleman RE, Wilson C, Powles TJ, Clezardin P, Aapro M, Costa L, Body JJ, Markopoulos C, Santini D, Diel I, Di Leo A, Cameron D, Dodwell D, Smith I, Gnant M, Gray R, Harbeck N, Thurlimann B, Untch M, Cortes J, Martin M, Albert US, Conte PF, Ejlertsen B, Bergh J, Kaufmann M, Holen I. Adjuvant bisphosphonates in early breast cancer: consensus guidance for clinical practice from a European panel. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:379. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang X, Yang KH, Wanyan P, Tian JH. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of denosumab versus bisphosphonates in breast cancer and bone metastases treatment: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Oncol Lett. 2014;7:1997. doi: 10.3892/ol.2014.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chirappapha P, Kitudomrat S, Thongjood T, Aroonroch R. Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of jaws in advanced stage breast cancer was detected from bone scan: a case report. Gland Surg. 2017;6:93. doi: 10.21037/gs.2016.07.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Otto S, Hafner S, Mast G, Tischer T, Volkmer E, Schieker M, Sturzenbaum SR, von Tresckow E, Kolk A, Ehrenfeld M, Pautke C. Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: is pH the missing part in the pathogenesis puzzle? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;68:1158. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.07.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ruggiero S, Saxena D, Tetradis S, Aghaloo T, Ioannidou E. Task force on design and analysis in oral health research: medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. JDR Clin Trans Res. 2018;3:222. doi: 10.1177/2380084418770662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jepsen S, Caton JG, Albandar JM, Bissada NF, Bouchard P, Cortellini P, Demirel K, de Sanctis M, Ercoli C, Fan J, Geurs NC, Hughes FJ, Jin L, Kantarci A, Lalla E, Madianos PN, Matthews D, McGuire MK, Mills MP, Preshaw PM, Reynolds MA, Sculean A, Susin C, West NX, Yamazaki K. Periodontal manifestations of systemic diseases and developmental and acquired conditions: consensus report of workgroup 3 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions. J Periodontol. 2018;89(Suppl 1):S237. doi: 10.1002/JPER.17-0733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Egloff-Juras C, Gallois A, Salleron J, Massard V, Dolivet G, Guillet J, Phulpin B. Denosumab-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: a retrospective study. J Oral Pathol Med. 2018;47:66. doi: 10.1111/jop.12646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mendes V, Dos Santos GO, Calasans-Maia MD, Granjeiro JM, Moraschini V. Impact of bisphosphonate therapy on dental implant outcomes: an overview of systematic review evidence. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2019;48:373. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2018.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jacobsen C, Metzler P, Rossle M, Obwegeser J, Zemann W, Gratz KW. Osteopathology induced by bisphosphonates and dental implants: clinical observations. Clin Oral Investig. 2013;17:167. doi: 10.1007/s00784-012-0708-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McClung MR. Bisphosphonate therapy: how long is long enough? Osteoporos Int. 2015;26:1455. doi: 10.1007/s00198-014-3019-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tsourdi E, Makras P, Rachner TD, Polyzos S, Rauner M, Mandanas S, Hofbauer LC, Anastasilakis AD. Denosumab effects on bone density and turnover in postmenopausal women with low bone mass with or without previous treatment. Bone. 2019;120:44. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2018.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hoefert S, Yuan A, Munz A, Grimm M, Elayouti A, Reinert S. Clinical course and therapeutic outcomes of operatively and non-operatively managed patients with denosumab-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (DRONJ) J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2017;45:570. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2017.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Leitlinienprogramm Onkologie (Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft DK, AWMF): Diagnostik, Therapie und Nachsorge für Patienten mit monoklonaler Gammo- pathie unklarer Signifikanz (MGUS) oder Multiplen Myelom, Langversion 1.01 (Konsulta- tionsfassung, 2021, AWMF Registernummer: 018/035OL; https://www.leitlinienpro-gramm-onkologie.de/leitlinien/multiples-myelom/

- 61.Leitlinienprogramm Onkologie (Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft DK, AWMF): S3-Leitlinie Prostatakarzinom, Langversion 6.0, 2021, AWMF Registernummer: 043/022OL, http://www.leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/leitlinien/prostatakarzinom/.

- 62.Leitlinienprogramm Onkologie (Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft DK, AWMF): S3-Leitlinie Prostatakarzinom, Langversion 6.0, Mai 2021, AWMF Registernummer: 043/022OL, http://www.leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/leitlinien/prostatakarzinom/. (ed. AWMF online, 2021