Abstract

Objectives:

To describe treatment and monitoring outcomes of posterior teeth with cracks at baseline followed in the National Dental Practice-Based Research Network for up to three years.

Materials and Methods:

Two hundred and nine dentists enrolled a convenience sample of 2,858 patients, each with a posterior tooth with at least one visible crack and followed them for three years. Characteristics at the patient, tooth and crack level were recorded at baseline and at annual recall visits. Data on all teeth referred for extraction were reviewed. Data on all other teeth, treated or monitored, seen at one or more recall visits were reviewed for evidence of failure (subsequent extraction, endodontics or recommendation for a re-treatment).

Results:

The survival rate for teeth with cracks at baseline exceeded 98% (only 37 extractions), and the failure rate for teeth that were treated restoratively was only 14%. Also, only about 14% of teeth recommended at baseline for monitoring were later recommended to be treated, and about 6.5% of teeth recommended for monitoring at baseline were later treated without a specific recommendation. Thus, about 80% of teeth recommended at baseline for monitoring continued with a monitoring recommendation throughout the entire three years of the study. Treatment failures were associated with intra-coronal restorations (vs. full or partial coverage) and male patients.

Conclusions:

In this large 3-year practice-based study conducted across the United States, the survival rate of posterior teeth with a visible crack exceeded 85%.

Clinical Relevance:

Dentists can effectively evaluate patient, tooth, and crack level characteristics to determine which teeth with cracks warrant treatment and which only warrant monitoring.

Keywords: cracked teeth, practice-based research, failure, restoration, extraction

Introduction

The ideal course of action for teeth with cracks often presents a conundrum to dentists, ranging from tooth extraction, restoration, or monitoring, depending upon the suspected severity of the situation, including other characteristics of the tooth and the presence and extent of symptoms [1]. Most studies that investigated treatment outcomes of teeth with cracks reported on a particular type of treatment, root canal therapy (RCT), but not on other potential treatment outcomes or on cracked teeth not treated.

Krell and Rivera reported that 21% of teeth with reversible pulpitis and visible cracks (the majority being on the distal margin and verified with transillumination) that had been immediately treated with a crown required RCT within 2-5 months [2]. Another study of 50 teeth with cracks that were treated by RCT reported a two-year survival of 85.5% [3]. Kang et al. [4] reported a two-year survival of 90% for 88 RCT-treated teeth with cracks, and the prognosis was poorest for teeth with probing depths exceeding 6 mm and class II restorations. Recently a one-year success rate of 82% was reported for 363 cracked teeth treated with orthograde RCT, the majority having amalgam restorations (58%), confirming that the factors most associated with failure were probing depth exceeding 5 mm and cracks on the distal marginal ridge [5]. Sim et al. [6] followed 84 patients with RCT-treated teeth with cracks and reported a Kaplan-Meier five-year survival of 95% but showed 11X higher odds of failure when the teeth had cracks that extended onto the pulpal floor. However, a more recent prospective study of 53 RCT-treated teeth (with crowns existing or crowns placed after the RCT) that had cracks with radicular extensions reported 100% success at two years and 96.6% from two to four years [7]. Further, over 90% of the teeth were asymptomatic when evaluated from two to four years later. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis based on seven studies reported an 88% survival rate after one year for RCT teeth with cracks [8]. Thus, within the first five years, prognosis for cracked teeth treated with RCT and then restorations, typically crowns, is very good and essentially equivalent to that of non-cracked RCT teeth.

Several studies have followed teeth with cracks treated restoratively but without RCT. Opdam et al. [9] compared outcomes of painful cracked teeth restored with direct composite, with or without cuspal coverage. Of 40 teeth, only three required RCT (7.7%) during seven years of follow-up, and these were all in the non-cuspal coverage group. Signore et al. [10] reported a similar frequency of RCT for 43 teeth with cracks treated with bonded composite onlays and evaluated for four to six years. All three of the endodontic treatments were required within the first five months, and overall survival at six years was 93%. Abbot and Leow [11] reported on 100 cracked teeth consecutively treated with sedative fillings and interim restorations and ultimately with crowns or onlays. Only 15% of the teeth needed RCT immediately. None of the 46 teeth followed for up to five years required RCT, suggesting that the initial conservative treatment approach followed by crowning the tooth was highly successful. Kanemaru et al. [12] reported excellent results from one to three years for 38 teeth with cracks and non-working side interferences when treated with full coverage restorations (after RCT or with vital pulps). All of these studies suggest that the prognosis for restoratively treated cracked teeth is very good, especially when the crack is diagnosed before significant damage to the tooth has occurred.

The Cracked Tooth Registry (CTR) was a prospective observational study of nearly 3,000 teeth with at least one visible external crack followed for up to three years in The National Dental Practice-based Research Network. The overall goal was to identify characteristics that may help to predict which teeth will get worse and when the practitioner should intervene, as well as to assess the outcomes of specific interventions. The recommendations for treatment of teeth with cracks were previously presented [13].

The primary objective of this report is to describe treatment and monitoring outcomes of posterior cracked teeth over three years. Secondary objectives are to ascertain differences between groups recommended to be treated and those treated, with or without a recommendation.

Methods

This prospective cohort study was conducted in the network [14]. The full study protocol has been described in detail [13, 15]. The subjects chosen were from a convenience sample and were between 19 and 85 years old and had at least one vital posterior tooth with a visually identifiable external crack. Teeth with fractures at baseline were ineligible. At baseline, dentists selected and characterized one eligible cracked posterior tooth per subject. Practitioners were given training materials in which a crack was differentiated from a full or partial fracture and was defined as follows: an obvious break of the external contiguous structure of the tooth, but involves no loss of tooth structure (e.g., lost cusp). The participants recorded a variety of patient-, tooth- and crack-level characteristics, such as the presence and type of pain (spontaneous, cold, biting), and any treatments recommended or performed. Data forms are publicly available at [http://nationaldentalpbrn.org/study-results/cracked-tooth-registry.php; click on “studies”, then “study results”, then “crack tooth registry” to reach data forms]. The enrollment period ran for eight weeks or until a maximum of 20 subjects were enrolled. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the lead investigators (TH & JF), as well as those of the six network regions. Patients were enrolled from April 2014 through April 2015.

Patients were placed on an annual recall (follow-up) schedule for three years (Y1 – Y3). The first two annual recalls occurred within a permitted six-month window, which was expanded for Y3 to maximize final recall visits (Y3 visits were between 03/2017 and 12/2018). Therefore, some patients had up to 22 months between the last two recall visits (4% of 1,434 who attended both Y2 and Y3 had a greater than the maximum of 19 months between the first two recall visits). The same data were collected at baseline (Y0) and each recall or interim visit, including presence/absence of cold, biting, and spontaneous pain, treatments recommended and performed. Treatments included extraction, RCT (with or without restoration), restoration only, and other (e.g., desensitizing, occlusal adjustment). An interim visit was when the patient was treated between scheduled recalls. All treatment decisions were made by the practitioner in consultation with the patient and were not a requirement of the study protocol. A subject was withdrawn from the study if their study tooth was referred for extraction, whether at a recall or interim visit. The Data Coordinating Center (DCC) employed a robust effort involving reminders to the offices and specific patient tracking procedures to maximize recall participation. A nominal remuneration was provided for the baseline and annual recall visits to both patients and practitioners. Overall, 2,858 patients were enrolled by 209 practitioners.

Data for teeth with cracks that were treated were reviewed for evidence of treatment failure (subsequent extraction, RCTs or recommendation for a re-treatment, whether performed or not). For the failures, the type of restoration (direct vs. indirect, intra-coronal vs. crown/partial crown, bonded or not, whether any build-up was needed) that failed was compared to those that did not fail.

Analysis

First, cracked teeth were categorized based on what was recommended at Y0: non-surgical treatment, surgical treatment (any combination of extraction, RCTs, and restoration), and monitor only (Figure 1). Descriptive analysis of the occurrence and timing of all teeth referred for extraction (thus withdrawn), a primary study outcome, is also presented. Changes in treatment recommendations and any treatments performed are described for teeth for which non-surgical treatment was recommended at Y0. Teeth for which surgical treatment was recommended at Y0 were classified into three groups: 1) no treatment performed throughout the three years of follow-up; 2) practitioner recommended definitive treatment; and 3) practitioner recorded that additional treatments would be needed after completing the initial treatment that was recommended at Y0 (i.e., recommending multiple treatments at Y0). Separating recommended treatment into two groups was needed because of the inability to determine failures in many of the teeth in group #3. For groups #2 and #3, teeth that had a treatment performed on ≥ 2 visits were reviewed in detail by a study P.I. (TH) to determine if treatments performed on later visits were to complete what was recommended at Y0 or because of treatment failure. Cracked teeth that were recommended at Y0 for monitoring were categorized as to whether the treatment recommendation changed from monitor to surgically treat at any time. Those who had a recommendation for treatment later and had a treatment performed at ≥ 2 visits were reviewed to determine if any second treatment was because of failure of the first treatment or to complete the initial treatment recommended. In each category in which treatment failures were identified, the details of the treatments performed, namely, whether a build-up was placed, direct or indirect, bonded or not, and intra-coronal, full or partial crown, were compared.

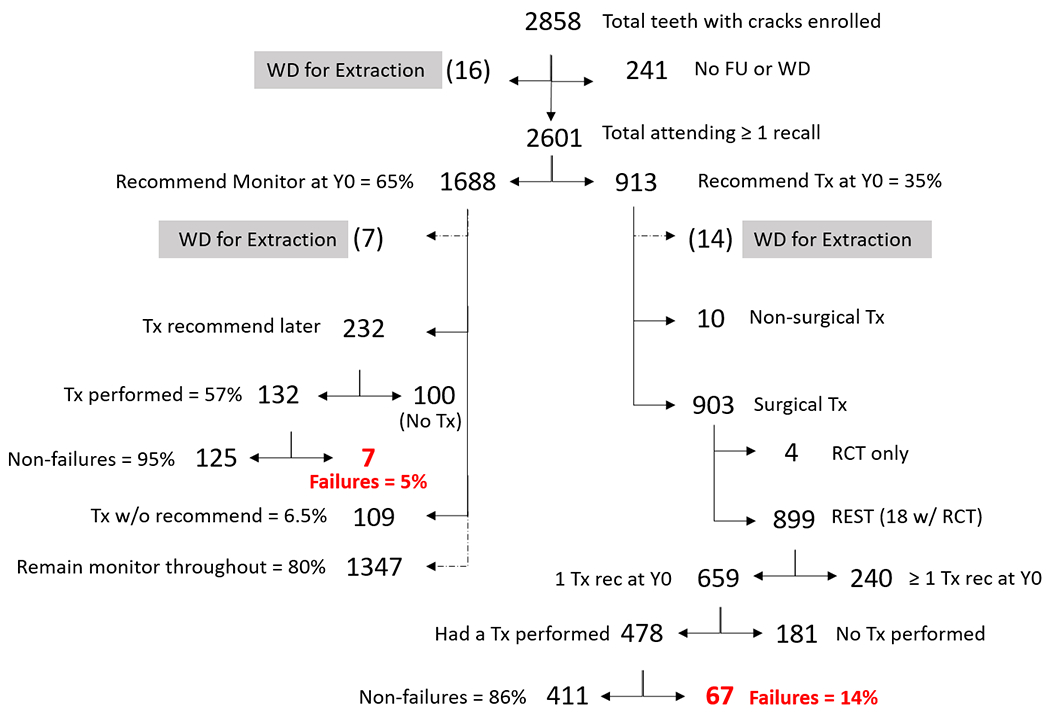

Figure 1:

Dispensation of the total teeth with cracks enrolled in the study, specifically differentiating those recommended at baseline (Y0) to be treated (Tx) or monitored. (WD = withdrawn, FU = follow-up), RCT = root canal therapy, REST = restorative treatment).

For teeth recommended for surgical treatment at Y0, differences in practitioner-, patient-, tooth- and crack-level characteristics, including types of pain (cold, biting and spontaneous) and changes in pain from Y0 to follow-up (virtually all patient, tooth, and crack characteristic on the data forms were assessed), were established to compare teeth that were treated with those not treated; similarly, these differences were compared among teeth recommended to be monitored at Y0 and at all subsequent recalls with those having a subsequent recommendation change to surgical treatment.

Significance of differences were ascertained using a generalized estimating equation (GEE) to adjust for the clustering of patients within the practice, which was implemented using a generalized model procedure (PROC GENMOD in SAS with the CORR=EXCH option). Independence of associations was determined by entering all characteristics with p<0.10, after adjusting only for the clustering of patients within the practice, into a full model. This was followed with backward elimination to identify independent associations and removing variables until all remaining variables had p<0.05. All odds ratios (OR) and p-values reported were adjusted for the clustering of patients within practitioners with GEE. This method was used to ascertain all independent associations described below. All analyses were performed using SAS software (SAS v9.4, SAS Institute Inc., Cary NC).

Results

Of the 2,858 patients/teeth enrolled, 241 (8.4%) had no follow-up and were not withdrawn due to tooth extraction (Figure 1). A total of 37 cracked teeth (1.3% of all 2,858 enrolled teeth) were withdrawn due to recommendation to have the tooth extracted at some point during the study, 16 without attending any recall visit (Details provided in Supplemental Figure 1).

The numbers of patients who attended each combination of recall examinations are given in Table S1, as are the dates of the recall examinations, the mean and median number of months, and inter-quartile range (IQR) between examinations and follow-up times. Of the 2,601 (91.0%) who attended at least one recall examination, 2,079 attended Y3, and 1,912 attended all three recall examinations, with a mean number of follow-up months of 37.4 (sd=3.1).

Of the 2,601 patients who attended at least one annual recall, 913 (35%) were recommended at Y0 to have some type of treatment (Figure 1): 10 had non-surgical recommendations (7 occlusal adjustments, 2 desensitization, 1 unspecified diagnostic tests), 2 later had a recommendation to surgically treat and 1 had a treatment performed without a prior recommendation. None of these were considered treatment failures. For 903, the following surgical treatments were recommended: 4 RCTs only, 18 RCTs and restoration, and 881 restorations only. Of the 4 recommended for RCTs only, 1 was treated with RCT and the others were never treated (recommendation later changed to monitor). None of these 4 were considered treatment failures. Of the 18 recommended for RCTs and restoration, 9 were recommended for multiple treatments at Y0 and could not be evaluated for failure. Only 5 of the 9 recommended for definitive treatment at Y0 were treated, 3 had both a RCT and restoration performed and 2 had only a restoration performed. On review, none of the 9 were considered failures. Details of restorations recommended and if treatment was completed and by whether multiple treatments were recommended at Y0 are presented in Figures S2 and S3.

Of the 899 that were recommended at Y0 to be restored, with or without RCTs, 715 (80%) had at least one restorative treatment performed. Several characteristics were associated with 715 of these 899 teeth having a restorative treatment performed (Tables 1 and 4A): type of practice (owners of private practices and members of preferred provider organizations [PPO] had higher completion rates), region (Western and Northeast had the highest completion rate at 88% and Southwest had the lowest at 69%), patients with higher education attainment, biting or spontaneous pain or caries present on the tooth, had an intra-coronal restoration recommended, or the practitioner recommended multiple treatments at Y0. Teeth that had a wear facet through enamel or a crack that extended to the root were less likely to be treated. Of note, the Southwest region had fewer patients attend Y2 or Y3 recall exams (72% vs. 91%, p=0.04).

Table 1.

Practice, patient and tooth characteristics at baseline (Y0) by whether any restorative treatment (Tx) was performed among the 899 teeth that were recommended for treatment at Y0.

| (N=899) | Whether Restorative Tx Was Performed | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALL1 | Column % | N | Row %2 | P 3 | OR 4 | |

| Type of practice | P = 0.03 | categorical | ||||

| Owner private practice | 729 | 81% | 591 | 81% | ||

| HP/PDA other PPO54 | 65 | 7% | 58 | 89% | ||

| Other, unknown | 105 | 12% | 66 | 63% | ||

| Network Region | P = 0.03 | categorical | ||||

| Western | 149 | 17% | 131 | 88% | ||

| Midwest | 147 | 16% | 124 | 84% | ||

| Southwest | 167 | 19% | 116 | 69% | ||

| South Central | 178 | 20% | 137 | 77% | ||

| South Atlantic | 129 | 14% | 94 | 73% | ||

| Northeast | 129 | 14% | 113 | 88% | ||

| Patient’s Level of Education | P = 0.04 | 1.4 | ||||

| < Bachelor’s degree | 400 | 45% | 305 | 76% | ||

| Bachelor’s or higher | 496 | 55% | 407 | 82% | ||

| Biting pain at Y0 | P = 0.008 | 1.7 | ||||

| No | 592 | 66% | 450 | 76% | ||

| Yes | 307 | 34% | 265 | 86% | ||

| Spontaneous pain at Y0 | P = 0.02 | 1.7 | ||||

| No | 682 | 76% | 531 | 78% | ||

| Yes | 217 | 24% | 184 | 85% | ||

| Wear facet thru enamel at Y0 | P = 0.03 | 0.65 | ||||

| No | 645 | 72% | 534 | 83% | ||

| Yes | 254 | 28% | 181 | 71% | ||

| Caries present at Y0 | P < 0.001 | 2.4 | ||||

| No | 644 | 72% | 491 | 76% | ||

| Yes | 255 | 28% | 224 | 88% | ||

| Non-carious cervical lesion present at Y0 | P = 0.07 | 0.58 | ||||

| No | 827 | 92% | 669 | 81% | ||

| Yes | 72 | 8% | 46 | 64% | ||

| Has a crack that connects with restoration at Y0 | P = 0.03 | 0.62 | ||||

| No | 191 | 21% | 165 | 86% | ||

| Yes | 708 | 79% | 550 | 78% | ||

| Has a crack that…extends to root at Y0 | P = 0.02 | 0.45 | ||||

| No | 802 | 89% | 658 | 82% | ||

| Yes | 97 | 11% | 57 | 59% | ||

| Intracoronal restoration recommended at Y0 | P < 0.001 | 2.0 | ||||

| No (Crown, full or partial) | 593 | 66% | 451 | 76% | ||

| Yes | 306 | 34% | 264 | 86% | ||

| Multiple treatments recommended at Y0 | P < 0.001 | 27.4 | ||||

| No | 659 | 73% | 478 | 73% | ||

| Yes | 240 | 27% | 237 | 99% | ||

Column Ns not summing to 899 due to missing data.

Percent within level of row characteristic.

Significance of differences in proportions of column heading adjusted only for clustering of patients within practitioner.

OR: Odds ratios (only for dichotomous variables)

HP: Health Partners; PDA: Permanente Dental Associates; PPO: Preferred provider organization.

Table 4.

Independent associations, using general estimating equations from univariable associations in Tables 1–3.

| A. Practice, patient, and tooth characteristics at baseline (Y0), by whether any restorative treatments were performed among 899 teeth that were recommended for treatment at Y0 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted only for clustering | Full model | Final, reduced model | |||||

| Characteristic | Odds Ratio | P1 | Odds Ratio | P1 | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | P1 |

|

| |||||||

| Practice type | categorical | 0.03 | categorical | 0.002 | categorical | 0.002 | |

| Region | categorical | 0.03 | categorical | 0.01 | categorical | 0.01 | |

| Education BS or greater | 1.4 | 0.04 | 1.5 | 0.03 | 1.5 | 1.1 - 2.0 | 0.03 |

| At Y0 | |||||||

| Biting pain | 1.7 | 0.008 | 1.6 | 0.04 | 1.7 | 1.1 - 2.6 | 0.03 |

| Spontaneous pain | 1.7 | 0.02 | 1.7 | 0.046 | 1.7 | 1.0 - 2.9 | 0.047 |

| Wear facet thru enamel | 0.65 | 0.03 | 0.48 | 0.002 | 0.47 | 0.31 - 0.71 | 0.002 |

| Caries present | 2.4 | <0.001 | 2.0 | 0.007 | 2.0 | 1.3 - 3.3 | 0.005 |

| Noncarious lesion present | 0.58 | 0.07 | 0.65 | 0.15 | - | not retained | - |

| Has crack that connects w/ restoration | 0.62 | 0.03 | 0.73 | 0.3 | - | not retained | - |

| Has crack that that extends to root | 0.45 | 0.02 | 0.35 | 0.01 | 0.35 | 0.17 - 0.72 | 0.01 |

| Intracoronal restoration | 2.0 | <0.001 | 3.4 | <0.001 | 3.6 | 2.1 - 5.9 | <0.001 |

| Recommend multiple treatments at Y0 | 27.4 | <0.001 | 41.7 | <0.001 | 41.2 | 14.2 - 119.6 | <0.001 |

|

| |||||||

| B. Among the teeth for which the dentist recommended restorative treatment as the definitive treatment at baseline (Y0), comparison of the characteristics of the teeth that nonetheless never received treatment during follow-up (N=181) to the teeth that did receive restorative treatment at some point during follow-up (N=478) | |||||||

| Region | categorical | 0.04 | categorical | 0.02 | categorical | 0.02 | |

| Associate of private practice | 3.0 | 0.03 | 2.7 | 0.037 | 2.9 | 1.4 - 6.1 | 0.03 |

| No biting pain at Y0 | 1.4 | 0.08 | 1.5 | 0.16 | -- | not retained | -- |

| No spontaneous pain at Y0 | 1.5 | 0.06 | 1.6 | 0.06 | 1.9 | 1.2 - 3.1 | 0.007 |

| Wear facet thru enamel | 1.6 | 0.02 | 2.0 | 0.004 | 1.9 | 1.3 - 2.9 | 0.006 |

| No caries present at Y0 | 2.2 | <0.001 | 2.6 | <0.001 | 2.5 | 1.6 - 4.0 | <0.001 |

| Noncarious cervical lesion present at Y0 | 1.8 | 0.065 | 1.8 | 0.052 | 1.9 | 1.1 - 3.2 | 0.037 |

| Has crack that connects w/ restoration | 1.7 | 0.03 | 1.5 | 0.14 | not retained | ||

| Has crack that blocks trans light | 1.5 | 0.07 | 1.3 | 0.25 | not retained | ||

| Has crack that that extends to root | 2.2 | 0.01 | 2.4 | 0.01 | 2.5 | 1.4 - 4.7 | 0.01 |

|

|

|

|

|||||

| C. Among the teeth for which the dentist recommended monitoring at baseline (Y0; N=1,688), comparison of the characteristics of the teeth whose dentist’s recommendation changed to treat during follow-up (restore; N=232 [14%]) to the characteristics of the teeth whose recommendation remained to monitor (109 teeth treated during follow-up that had no stated recommendation for treatment were excluded) | |||||||

| Adjusted only for clustering | Full model | Final, reduced model | |||||

| Characteristic | Odds Ratio | P1 | Odds Ratio | P1 | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | P1 |

|

| |||||||

| Patient male | 1.6 | 0.001 | 1.4 | 0.04 | 1.4 | 1.1 - 1.8 | 0.03 |

| Biting pain Y0-Y3 | 4.5 | <0.001 | 3.8 | <0.001 | 4.5 | 2.8 - 7.2 | <0.001 |

| Spontaneous pain Y0-Y3 | 2.6 | <0.001 | 1.6 | 0.08 | not retained | ||

| Any fracture Y1-Y3 | 29.3 | <0.001 | 25.5 | <0.001 | 25.3 | 10.7 - 59.7 | <0.001 |

| Caries present on tooth at Y1 or Y2 | 27.6 | <0.001 | 21.8 | <0.001 | 23.5 | 7.6 - 72.1 | <0.001 |

| Has crack that wear facet on tooth | 1.7 | <0.001 | 1.4 | 0.08 | not retained | ||

| Has crack that roots exposed on tooth | 1.4 | 0.047 | 1.2 | 0.3 | not retained | ||

|

|

|

|

|||||

Significance of differences in proportions of column heading adjusted only for clustering of patients within practitioner.

Of the 899 cracked teeth recommended for restoration at Y0, 659 had a single definitive treatment recommended at Y0 and 240 had multiple treatments recommended at Y0; 478 of the 659 were treated. These 478 were reviewed for failure, namely, that any additional treatment was subsequently needed after the recommended definitive treatment was completed. Overall, 67 (14% of 478) were determined to have failed. Treatment failures were associated with intra-coronal restorations (vs. full or partial coverage) and male patients, while patients from the Northeast and South Atlantic regions were less likely to have a treatment that failed. Neither direct vs. indirect restorations, bonded vs. non-bonded restorations, nor whether restorations required a buildup were associated with failure. Of the 240 that had multiple treatments recommended at Y0, 237 were treated. These were reviewed; no failures could be determined because of the complexity of the recommendations, the uncertainty over the definitive treatment, or the lack of adequate follow-up time.

Of the 659 patients with teeth recommended for definitive treatment at Y0, the 181 who were not treated were compared to the 478 who were treated to identify differences between the groups (Table 2). The distribution of those not treated varied across the regions, with the lowest proportion being in the Northeast and Western regions (15-17%) and the highest in the Southwest (41%). Patients whose dentist was an associate of a private practice, who did not have spontaneous pain at Y0, whose cracked tooth did not have caries, had a wear facet thru enamel, a non-carious cervical lesion, or a crack that extended to the root, were more likely to not be treated during the 3 years (Table 4B).

Table 2.

Among the teeth for which the dentist recommended restorative treatment as definitive treatment at baseline (Y0; N=659), comparison of the characteristics of the teeth that nonetheless never received restorative treated during follow-up (N=181) to the teeth that did receive restorative treatment at some point during follow-up (N=478)

| Recommended for Tx but Tx not received | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALL1 | Column % | N | Row %2 | P 3 | OR 4 | |

| Region | P = 0.04 | |||||

| Western | 107 | 16% | 18 | 17% | ||

| Midwest | 93 | 14% | 23 | 25% | ||

| Southwest | 122 | 19% | 50 | 41% | ||

| South Central | 121 | 18% | 39 | 32% | ||

| South Atlantic | 110 | 17% | 35 | 32% | ||

| Northeast | 106 | 16% | 16 | 15% | ||

| Associate of private practice | 58 | 9% | 30 | 52% | P = 0.03 | OR = 3.0 |

| Other practice settings | 601 | 91% | 151 | 25% | ||

| Biting pain at Y0 | 195 | 30% | 40 | 21% | P = 0.08 | OR = 1.4 |

| No biting pain at Y0 | 464 | 70% | 141 | 30% | ||

| Spontaneous pain at Y0 | 147 | 22% | 32 | 22% | P = 0.06 | OR = 1.5 |

| No spontaneous pain at Y0 | 512 | 78% | 149 | 29% | ||

| Wear facet thru enamel at Y0 | 182 | 28% | 71 | 39% | P = 0.02 | OR = 1.6 |

| No wear facet through enamel | 477 | 72% | 110 | 23% | ||

| Caries present at Y0 | 184 | 28% | 31 | 17% | P <0.001 | OR = 2.2 |

| No caries present at Y0 | 475 | 72% | 150 | 32% | ||

| Non-carious cervical lesion present at Y0 | 56 | 9% | 26 | 46% | P = 0.065 | OR = 1.8 |

| No non-carious cervical lesion present at Y0 | 603 | 92% | 155 | 26% | ||

| Has crack at Y0 that connects with a restoration | 521 | 79% | 155 | 30% | P = 0.03 | OR = 1.7 |

| No crack at Y0 connects with a restoration | 138 | 21% | 26 | 19% | ||

| Has crack at Y0 that blocks transilluminated light | 471 | 71% | 141 | 30% | P = 0.07 | OR = 1.5 |

| No crack at Y0 blocks transilluminated light | 188 | 29% | 40 | 21% | ||

| Has crack at Y0 that that extends to the root | 70 | 11% | 37 | 53% | P = 0.01 | OR = 2.2 |

| No crack at Y0 extends to root | 589 | 89% | 144 | 24% | ||

Column Ns not summing to 899 due to missing data.

Percent within level of row characteristic.

Significance of differences in proportions of column heading adjusted only for clustering of patients within practitioner.

OR: Odds ratios (only for dichotomous variables)

At Y0, 1,688 (65% of 2,601) cracked teeth were recommended to be monitored (Figure 1). Of these, 232 (14%) later had a recommendation to (surgically) treat, of which 132 (57% of 232) had a treatment performed. Only 7 (5% of 132) were determined to have failed, which was too few for statistical analysis. There were 109 cracked teeth that were treated without a prior recommendation (6.5% of 1,688). Eighty percent of the teeth recommended to be monitored at Y0 remained as such through all three years (1,347 of 1,688).

To ascertain why treatment recommendations changed from Y0, those with a change from monitor to surgical treatment were compared to those that remained monitor (232 vs. 1,347). The 109 treated without a prior recommendation were excluded. Those that had their recommendation changed were more likely to be male, had biting pain sometime between Y0-Y3, developed a tooth fracture, or had caries on the tooth at Y1 or Y2 (Tables 3 and 4C).

Table 3.

Among the teeth for which the dentist recommended monitoring at baseline (Y0; N=1,688), comparison of the characteristics of the teeth whose dentist’s recommendation changed to treat during follow-up (restore; N=232 [14%]) to the characteristics of the teeth whose recommendation remained to monitor*

| Recommended Treat after Y0 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALL1 | Column % | N | Row %2 | P 3 | OR 4 | |

| Patient male | 563 | 36% | 104 | 18% | 0.001 | OR = 1.6 |

| Patient female | 1015 | 64% | 128 | 13% | ||

| Biting pain anytime Y0-Y3 | 172 | 11% | 64 | 37% | <0.001 | OR = 4.5 |

| No biting pain Y0-Y3 | 1407 | 89% | 168 | 12% | ||

| Spontaneous pain anytime Y0-Y3 | 148 | 9% | 40 | 27% | <0.001 | OR = 2.6 |

| No spontaneous pain Y0-3 | 1431 | 91% | 192 | 13% | ||

| Any fracture Y1-Y3 | 50 | 3% | 40 | 80% | <0.001 | OR = 29.1 |

| No fractures developed | 1529 | 97% | 192 | 13% | ||

| Caries present on tooth at Y1 or Y2 | 33 | 2% | 27 | 82% | <0.001 | OR = 27.6 |

| No caries present at Y1 or Y2 | 1546 | 95% | 205 | 13% | ||

| Wear facet on tooth at Y1 or Y2 | 405 | 26% | 80 | 20% | <0.001 | OR = 1.7 |

| No wear facet on tooth at Y1 or Y2 | 1174 | 74% | 152 | 13% | ||

| Roots exposed on tooth | 486 | 31% | 87 | 18% | 0.04 | OR = 1.4 |

| No roots exposed on tooth | 1093 | 69% | 145 | 13% | ||

(N=109) teeth treated during follow-up that had not stated recommendation for treatment were excluded

Column Ns not summing to 1,688 due to missing data.

Percent within level of row characteristic.

Significance of differences in proportions of column heading adjusted only for clustering of patients within practitioner.

OR: Odds ratios (only for dichotomous variables)

Compared to those remaining monitor throughout, the only characteristic associated with the 109 teeth that received treatment without a prior recommendation was a crack connecting with an existing restoration (OR=2.4; 95% CI=1.4-4.0; p<0.001), while having a wear facet through enamel was inversely associated with being treated without a recommendation (OR=0.20; 95% CI=0.07-0.53; P<0.001).

The majority of the 74 failed restorations were intra-coronal (64%, N=47), direct placement (66%, N=49) and bonded (72%, N=53); few (16%, N=12) were built-up prior to placement (Table 5). The specific restorative material used for the restoration could be determined for 54 (73%) failures, with the most frequent being composite (44%, N=23), followed by amalgam (20%, N=11) and ceramic (18%; N=10). The mean time between a restoration being completed and being determined to have failed (by a new recommendation to treat) was 18 months (sd=10) and the median was 14 months (IQR: 11 to 25). Though it was not possible to determine the reason(s) for failure in all instances, the main reasons for re-treatment (failure) were related to caries, broken restorations, or a compromised tooth.

Table 5.

Characteristics of the 74 restorations that were placed in cracked teeth that ultimately failed during follow-up

| # Failures | % of Total Failures | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Restoration Type | Intra-coronal | 47 | 64% | |

| Full Crown | 24 | 32% | ||

| Partial Crown | 3 | 4% | ||

| Type of placement | Direct | 49 | 66% | |

| Indirect | 25 | 34% | ||

| Bonded | Yes | 53 | 72% | |

| No | 21 | 28% | ||

| Build-up prior to placement | Yes | 12 | 16% | |

| No | 62 | 84% | ||

|

|

||||

| Material Type Used in the Restoration that was Followed Until Failure | % of 55 known materials | Average Time to Fail (months)* | ||

|

| ||||

| Composite | 23 | 40% | 19.8 | |

| Amalgam | 11 | 19% | 14.7 | |

| Glass ionomer | 3 | 5% | 17.0 | |

| Ceramic crown | 10 | 18% | 15.0 | |

| Metal crown | 5 | 9% | 14.6 | |

| PFM | 2 | 4% | - | |

| Other | 1 | 2% | - | |

|

| ||||

| Unknown | 22 | |||

Number months from restoration completion to failure (recommendation or placement of new restoration, root canal, fracture, extraction)

Discussion

This observational study with up to 3 years of follow-up of 2,858 posterior teeth with a single or multiple cracks represents the largest longitudinal study of outcomes of cracked teeth to date. Only 37 (1.3%) of the total enrolled teeth were extracted during the study. Ninety-one percent of the cohort (N=2,601) attended at least one of the annual recall visits. Sixty-five percent (N = 1,688) of those followed were recommended to be monitored at Y0; 80% (1,347) of these remained as such through all three years. Less than 8% (N = 241) of the teeth originally recommended to be monitored were treated within the 3 years of the study. This suggests that practitioners accurately assessed more than 92% percent of the teeth when they determined that only monitoring was necessary. Recommendation for treatment at Y0 was recorded for 35% (N = 913), almost always (N=899) involving some type of restorative procedure. Eighty percent (N = 715) received the restorative treatment recommended at Y0. Confirmation of failure or survival could be made for 478 restored teeth with 67 teeth identified as failures (14%), i.e., needed additional treatments beyond original recommendation.

The failures were more common with intra-coronal as opposed to full or partial coverage restorations, male patients, and less common in the Northeast and South Atlantic than the other 4 regions. Since the majority of the intracoronal restorations were bonded composites, it is reasonable to assume that a higher proportion of the failed restorations were composites. Full coverage restorations have also been advocated for cracked teeth, especially when it is suspected that the crack originated from occlusal interferences [12]. The favorable outcome for full or partial coverage is in agreement with that of two previous studies, one in which direct bonded cuspal coverage resin composites for teeth with cracks performed better over 7 years than direct bonded intracoronal composites [9], and the other which showed a six-year survival rate of 93% for teeth with cracks treated with cemented composite onlays [10]. The favorable outcome for full coverage restorations is consistent with the fact that practitioners in this study most often recommended a full crown as the treatment of choice for cracked teeth [13]. The fact that failures were more common for males may relate to the greater occlusal forces produced, in general, for male patients, thus further extending the crack or damaging the tooth [16].

It is not obvious why there was a regional difference in incidence of failure of the treated cracked teeth. Since failures were more associated with intracoronal restorations, one may expect that a higher proportion of restorations placed in the South Atlantic and Northeast, where failures were less frequent, would have been full or partial coverage. However, the opposite was true, and in fact the ratio of full/partial coverage to intracoronal restorations was lowest in the South Atlantic and Northeast, as compared with the other four regions.

Due to the small number of failures, it is not possible to ascertain the significance of differences in times to failure for the different types of restoration characteristics. However, mean times to failure for each of the categories (i.e., direct vs indirect, bonded vs. non-bonded, intracoronal vs full/partial coverage, buildup vs. none) was about one and a half years, suggesting that some similar factors, such as overall quality of the remaining tooth structure featured most prominently in the duration of success, independent of how the tooth was restored.

There were some commonalities of presence of caries and pain in associations regarding treatments recommended and whether performed. Previously we reported characteristics associated with a cracked tooth being recommended for treatment at Y0 [13]. The strongest associations were with presence of caries, biting, spontaneous and cold pain. In the present report assessing which teeth were restored among the 899 recommended for restoration at Y0, biting and spontaneous pain, and presence of caries were each associated with the cracked tooth having a restoration performed. Also, being a male patient, having persistent biting pain, active caries and development of fractures were associated with having a recommendation from monitor at Y0 change to restore at a recall visit. Conversely, lack of spontaneous pain at Y0 and no active caries on the tooth were associated with treatment not being performed, though recommended. The 181 teeth recommended to be restored at Y0 but never treated may not have been causing issues for the patient, at least not significant enough to motivate them to have the originally recommended treatment. Several tooth and crack characteristics were examined for each of the comparisons above; a few were observed, but most were weak associations, and none were common across associations.

It is important to note that only 37 (1.3%) of the total enrolled teeth were extracted during the study. This suggests an excellent prognosis for maintenance of a cracked tooth for at least one and up to three years, whether treated or not. Most of the studies on survival of treated cracked teeth involve those receiving endodontic therapy, and one meta-analysis showed a survival rate at one year of 88% [8]. Another recent meta-analysis reported a survival rate of 93% at one year and 84% remaining at five years [17]. The current study showed even better results with none of the 18 teeth treated with RCT being lost within the three years.

Limitations of this study include the fact that the patients were not randomly selected and thus may not be representative of all people who have posterior teeth with cracks. However, allowing practitioners to choose patients who had a high expected retention probability was considered most important, and likely contributed to the high retention rate observed. In addition, although all study personnel underwent pre-participation training, some of the data collected were subjective and open to multiple interpretations, making it impossible to fully describe the outcomes for all treated teeth. For example, for the 237 teeth that had multiple treatments, presence or absence of failure could never be determined due to inadequate records, despite detailed training of practices by regional coordinators using a detailed manual of procedures. Another limitation is the fact that the reason for extraction, and therefore withdrawal of the tooth from the study, was only recorded if this occurred at a prescribed recall visit. No reason was recorded for the 68% of extractions (25 of 37) that occurred at an interim visit. Similarly, only reasons for recommending treatments were recorded, not for treatments performed, namely, those without a prior recommendation or if treatment was different than, or in addition to, what was recommended. This was common among failures. For example, anecdotal evidence showed that on some occasions when the dentist attempted to place a crown, the tooth was found to be unstable, leading to its extraction or referral for extraction. Lastly, the small number of outcomes, specifically extractions, and of teeth treated with RCT, either alone (12) or in combination with a restoration (20), made it impossible to perform statistical analysis on any treatment other than restorations. This includes analyses regarding who is treated and of failures among those treated, the focus of this paper.

The strengths of this study include a high number of patients enrolled in different types of practice settings distributed geographically across the entire United States. In addition, the patients were evaluated longitudinally for a variety of outcomes, and the recall rate was very high with 91% attending at least one follow-up. Further, the results of this study are very similar to those reported by others for teeth with cracks, showing that outcomes of restorations with cuspal coverage perform better than bonded intracoronal restorations.

In summary, this three-year observational study provides strong evidence for the successful treatment of posterior teeth with cracks, especially when using full or partial coverage restorations. The survival rate for teeth with cracks exceeded 98%, and the failure rate for teeth that were treated restoratively was only 14%. Overall, the results suggest that dentists are effective at evaluating patient, tooth, and crack level characteristics to determine which teeth with cracks to recommend for treatment, and which to recommend for monitoring.

Supplementary Material

Figure S2: Restoration completion rate (%) by restoration type, among 899 teeth that were recommended for restorative treatment at Y0. Yes = restoration completed; No = not completed.

Figure S1: Chronology of the 37 teeth extracted and withdrawn from the study, specifically differentiating those recommended at baseline (Y0) to be treated (Tx) or monitored (symp. = symptomatic, Fx = fracture, WD = withdrawn).

Figure S3: Percent of the restoration types (%) for which multiple treatments (Tx) vs. a single definitive treatment was recommended at Y0.

Acknowledgements

An Internet site devoted to details about the nation’s network is located at http://NationalDentalPBRN.org.

We are very grateful to the network’s Regional Node Coordinators along with other network staff (Midwest Region: Tracy Shea, RDH, BSDH; Western Region: Stephanie Hodge, MA; Northeast Region: Patricia Ragusa, BA; South Atlantic Region: Hanna Knopf, BA, and Deborah McEdward, RDH, BS, CCRP; South Central Region: Shermetria Massengale, MPH, CHES, and Ellen Sowell, BA; Southwest Region: Stephanie Reyes, BA, Meredith Buchberg, MPH, and Colleen Dolan, MPH; network program manager (Andrea Mathews, BS, RDH) and program coordinator (Terri Jones)), along with network practitioners and their dedicated staff who conducted the study.

Funding:

This work was supported by NIH/NIDCR grants U19-DE-28717 and U19-DE-22516. Opinions and assertions contained herein are those of the authors and are not to be construed as necessarily representing the views of the respective organizations or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Author Ferracane declares no conflict of interest. Author Hilton declares no conflict of interest. Author Funkhouser declares no conflict of interest. Author Gordan declares no conflict of interest. Author Gilbert declares no conflict of interest. Author Mungia declares no conflict of interest. Author Burton declares no conflict of interest. Author Meyerowitz declares no conflict of interest. Author Kopycka-Kedzierawski declares no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval: This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent: The informed consent of all human subjects who participated in this investigation was obtained after the nature of the procedures had been explained fully.

Contributor Information

Jack L. Ferracane, Department of Restorative Dentistry, School of Dentistry, Oregon Health & Science University, 2730 S.W. Moody Ave., Portland, OR 97201-5042.

Thomas J. Hilton, School of Dentistry, Oregon Health & Science University, 2730 S.W. Moody Ave., Portland, OR 97201-5042.

Ellen Funkhouser, School of Medicine, University of Alabama, Birmingham, 1720 2nd Avenue South, Birmingham, AL 35294-0007.

Valeria V. Gordan, Department of Restorative Dental Sciences, University of Florida, 1600 SW Archer Rd, Gainesville, FL 32610.

Gregg H. Gilbert, Department of Clinical and Community Sciences, School of Dentistry, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL.

Rahma Mungia, Department of Periodontics, School of Dentistry, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio.

Vanessa Burton, HealthPartners, 5901 John Martin Dr., Brooklyn Center, MN 55430.

Cyril Meyerowitz, Eastman Institute for Oral Health, University of Rochester, 601 Elmwood Avenue, Box 686, Rochester, NY 14642.

Dorota T. Kopycka-Kedzierawski, Eastman Institute for Oral Health, 625 Elmwood Ave, Box 683, Rochester, NY 14620.

References

- [1].Bader JD, Shugars DA, Roberson TM. Using crowns to prevent tooth fracture. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1996;24:47–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Krell KV, Rivera EM. A six year evaluation of cracked teeth diagnosed with reversible pulpitis: treatment and prognosis. J Endod. 2007;33:1405–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Tan L, Chen NN, Poon CY, Wong HB. Survival of root filled cracked teeth in a tertiary institution. Int Endod J. 2006;39:886–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Kang SH, Kim BS, Kim Y. Cracked Teeth: Distribution, Characteristics, and Survival after Root Canal Treatment. J Endod. 2016;42:557–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Krell KV, Caplan DJ. 12-month Success of Cracked Teeth Treated with Orthograde Root Canal Treatment. J Endod. 2018;44:543–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Sim IG, Lim TS, Krishnaswamy G, Chen NN. Decision Making for Retention of Endodontically Treated Posterior Cracked Teeth: A 5-year Follow-up Study. J Endod. 2016;42:225–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Davis MC, Shariff SS. Success and Survival of Endodontically Treated Cracked Teeth with Radicular Extensions: A 2- to 4-year Prospective Cohort. Journal of Endodontics. 2019;45:848–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Olivieri JG, Elmsmari F, Miró Q, Ruiz XF, Krell KV, García-Font M, et al. Outcome and Survival of Endodontically Treated Cracked Posterior Permanent Teeth: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Endod. 2020;46:455–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Opdam NJ, Roeters JJ, Loomans BA, Bronkhorst EM. Seven-year clinical evaluation of painful cracked teeth restored with a direct composite restoration. J Endod. 2008;34:808–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Signore A, Benedicenti S, Covani U, Ravera G. A 4- to 6-year retrospective clinical study of cracked teeth restored with bonded indirect resin composite onlays. Int J Prosthodont. 2007;20:609–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Abbott P, Leow N. Predictable management of cracked teeth with reversible pulpitis. Aust Dent J. 2009;54:306–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Kanamaru J, Tsujimoto M, Yamada S, Hayashi Y. The clinical findings and managements in 44 cases of cracked vital molars. Journal of Dental Sciences. 2017;12:291–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Hilton TJ, Funkhouser E, Ferracane JL, Schultz-Robins M, Gordan VV, Bramblett BJ, et al. Recommended treatment of cracked teeth: Results from the National Dental Practice-Based Research Network. J Prosthet Dent. 2020;123:71–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Gilbert GH, Williams OD, Korelitz JJ, Fellows JL, Gordan VV, Makhija SK, et al. Purpose, structure, and function of the United States National Dental Practice-Based Research Network. J Dent. 2013;41:1051–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Hilton TJ, Funkhouser E, Ferracane JL, Gilbert GH, Baltuck C, Benjamin P, et al. Correlation between symptoms and external characteristics of cracked teeth: Findings from The National Dental Practice-Based Research Network. J Am Dent Assoc. 2017;148:246–56.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Dheyriat A, Frutoso J, Lissac M. [The determination of the intensity of premolar and molar maximal forces during the isometric contraction of the masticatory muscles due to forced mandibular closure]. Bull Group Int Rech Sci Stomatol Odontol. 1996;39:87–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Leong DJX, de Souza NN, Sultana R, Yap AU. Outcomes of endodontically treated cracked teeth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Oral Investig. 2020;24:465–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S2: Restoration completion rate (%) by restoration type, among 899 teeth that were recommended for restorative treatment at Y0. Yes = restoration completed; No = not completed.

Figure S1: Chronology of the 37 teeth extracted and withdrawn from the study, specifically differentiating those recommended at baseline (Y0) to be treated (Tx) or monitored (symp. = symptomatic, Fx = fracture, WD = withdrawn).

Figure S3: Percent of the restoration types (%) for which multiple treatments (Tx) vs. a single definitive treatment was recommended at Y0.