Abstract

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) gave rise to an international public health emergency in 3 months after its emergence in Wuhan, China. Typically for an RNA virus, random mutations occur constantly leading to new lineages, incidental with a higher transmissibility. The highly infective alpha lineage, firstly discovered in the UK, led to elevated mortality and morbidity rates as a consequence of Covid-19, worldwide. Wastewater surveillance proved to be a powerful tool for early detection and subsequent monitoring of the dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 and its variants in a defined catchment. Using a combination of sequencing and RT-qPCR approaches, we investigated the total SARS-CoV-2 concentration and the emergence of the alpha lineage in wastewater samples in Vienna, Austria linking it to clinical data. Based on a non-linear regression model and occurrence of signature mutations, we conclude that the alpha variant was present in Vienna sewage samples already in December 2020, even one month before the first clinical case was officially confirmed and reported by the health authorities. This provides evidence that a well-designed wastewater monitoring approach can provide a fast snapshot and may detect the circulating lineages in wastewater weeks before they are detectable in the clinical samples. Furthermore, declining 14 days prevalence data with simultaneously increasing SARS-CoV-2 total concentration in wastewater indicate a different shedding behavior for the alpha variant. Overall, our results support wastewater surveillance to be a suitable approach to spot early circulating SARS-CoV-2 lineages based on whole genome sequencing and signature mutations analysis.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2 dynamics, WBE (Wastewater Based Epidemiology), Alpha lineage, Signature mutations, epidemiological data, whole genome sequencing

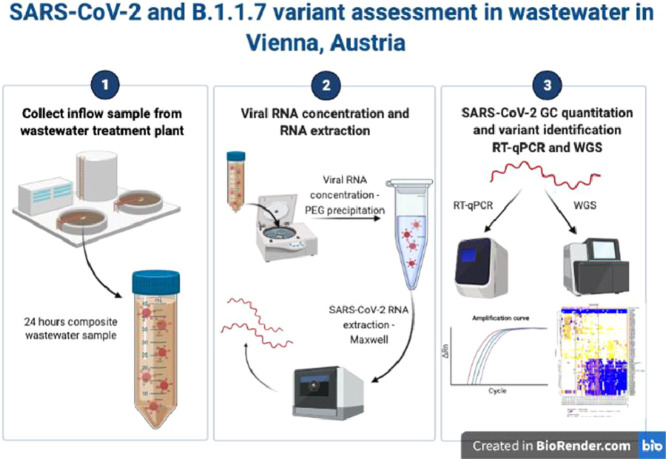

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

The novel Corona virus disease 2019 (Covid-19) caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was officially declared an international public health emergency by the WHO, within 3 months after its emergence in Wuhan, China (WHO, 2020a; 2020b). One year after the onset of the pandemic, the ongoing active cases are still raising, counting more than 229 million confirmed cases and over 4.7 million deaths as of by September 23rd 2021 (https://covid19.who.int/).

Although, the virus infects mainly the respiratory system, SARS-CoV-2 RNA has been also detected in human feces (Wang et al., 2020) and urine (Peng et al., 2020), resulting in a pool of viral particles from symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals in municipal wastewater (Sims and Kasprzyk-Hordern, 2020). Wastewater-based epidemiology (WBE) for SARS-CoV-2 surveillance, the concept proposed by Daughton (Daughton, 2020), enables the local authorities to have a real time overview of the prevalent RNA viral loads and variants in a defined sewer catchment. The approach has been successfully implemented in many countries for early detection of SARS-CoV-2 hotspots (Ahmed et al., 2020a; Fontenele et al., 2021; Gerrity et al., 2021; Medema et al., 2020). The clinical data associated with the epidemiological observations suggest municipal wastewater to be a useful tool for early warning and tracking the dissemination of SARS-CoV-2 in the community. A correlation between SARS-CoV-2 prevalence in primary sewage sludge and epidemiological data demonstrated that viral RNA concentrations in sewage sludge showed an increase that was not observed in the reported tests or hospital admission data, highlighting that the sludge results may be considered as an earlier, real-time approach regarding the infection dynamics (Peccia et al., 2020).

RT-qPCR (reverse transcription quantitative PCR) and WGS (whole genome sequencing) represent the most common tools applied for SARS-CoV-2 quantitation and identification. N-gene assay kits are implemented globally for SARS-CoV-2 screening by reason of their high specificity, sensitivity and fast results (Nalla et al., 2020). Due to the noticeable spread of more contagious variants (Variants of Concern – VOCs and Variants of Interest - VOIs), sequencing techniques proved to be the most valuable strategy to provide a deep and accurate understanding of the new circulating lineages (Fontenele et al., 2021; Martin et al., 2020; Rambaut et al., 2020b). The method is efficiently carried-out worldwide (Ahmed et al., 2020a; Alygizakis et al., 2021; Crits-Christoph et al., 2021; Popa et al., 2020), providing real-time data essential for understanding the pandemic dynamics. In a recent study, Fontanele and collabolators (2021) determined 263 SARS-CoV-2 SNVs (single nucleotide variants) in wastewater samples collected from different WWTPs (wastewater treatment plants) which have not been identified in clinical cases by then. Interestingly, spatial and temporal SARS-CoV-2 sequence variations were found in the wastewater samples from each location over time (Fontenele et al., 2021).

As with any replicating virus, random mutations accumulate in SARS-CoV-2 genome overtime, leading to new variants which potentially have a higher infectivity, virulence or capability to bypass the immune system response of its host. Computational studies based on epidemiological data, show that mutations located in the Spike receptor binding domain (RBD) of SARS-CoV-2 can boost its dissemination in the human population. It is already well known that the D614G mutation, which was firstly identified in February 2020 in Europe, enhances the SARS-CoV-2 infectivity and alters the virus fitness (Hu et al., 2020; Korber et al., 2020). Besides higher viral loads, the mutation doesn't affect the severity of the disease (Korber et al., 2020), nonetheless a 10-fold increase in the infectivity was observed compared with the original, Wuhan-1 strain (Li et al., 2020b). Furthermore, N501Y mutation presents a higher affinity to bind to the ACE2 (angiotensin-converting enzyme 2) receptor in human epithelial cells, resulting in an elevated shedding value, which presumably has a role in viral transmissibility (Khateeb et al., 2021; Luan et al., 2021). Therefore, D614G and N501Y mutations may enhance SARS-CoV-2 shedding, which can raise the infectivity and dissemination rates.

The present study describes the longitudinal screening of total SARS-CoV-2 GC (genome copies) and alpha lineage occurrence in Vienna, Austria, in the inflow sewage from the WWTP and in clinical samples during the time period around the emergence of the alpha lineage. The main goal of the manuscript is to report monitoring data regarding alpha variant abundance since its emergence in wastewater and to correlate the overall RT-qPCR signal with the epidemiological data. Alpha lineage assessment in sewage samples started in January 2021 in parallel with the official confirmation of the first clinical case carrying the new variant. Based on the hypothesis that alpha variant is associated with an increase of the viral RNA concentrations in the human stool, we presume that the new variant was present in Vienna sewage samples already in the middle of December 2020. To test our assumption, we correlated epidemiological data with sequencing and RT-qPCR results of wastewater samples for the same period.

The novelty of our approach is represented by the correlation of different data obtained from clinical and environmental samples to trace back the moment when SARS-CoV-2 alpha variant emerged in a defined sewer catchment. The correlation of SARS-CoV-2 RT-qPCR and sequencing data with the increasing trend in viral shedding compared with the epidemiological data highlight that a well-designed wastewater-based epidemiology may detect new variants already circulating before they are seen in clinic data. The present manuscript describes the first observation regarding the alpha lineage in wastewater samples in Vienna, Austria.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Wastewater monitoring sampling campaigns

The wastewater from the city of Vienna (1.9 million inhabitants) is collected in the sewerage system and further treated at the main WWTP. Due to a well-defined sewer system with an average flow time of about 2 h and connected to a single main WWTP, wastewater-based surveillance approach is feasible in real time. Representative 24 h flow proportional composite samples (CVVT – constant volume variable time) of untreated wastewater (sewage) were collected at least twice per week, directly from the inflow of the WWTP by an automated sampler. Samples were cooled at 4 °C during the 24-hour sampling duration directly in the sampler and afterwards transferred to the laboratory of the WWTP. There, the sewage samples were mixed thoroughly, transferred to sterile 1 L HDPE (High Density Poly Ethylene; Sigma Aldrich) bottles and transported to the processing laboratory on ice in insulated boxes. The wastewater samples were processed on the same day. During the period of the study, 73 samples were collected in total between October 4th 2020 and May 5th 2021. Wastewater inflow rate (m3/day) and temperature ( °C) were recorded on a daily basis. Total nitrogen (TN) was determined to calculate the corresponding daily loads and further for RT-qPCR results normalization in order to compensate for fluctuations related to dilution effects caused by storm water events. Information regarding sampling dates and wastewater characteristic parameters are given in Table S1- SI.

2.2. Wastewater viral concentration and RNA extraction

SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA was concentrated using a modified PEG (Polyethylene glycol) precipitation protocol (Medema et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020). Thoroughly mixed 45 ml aliquots from each sample were centrifuged at 4500 g for 30 min at 4 °C (the centrifuge was previously cooled down to 4 °C). 40 ml of the supernatant were further added to fresh 50 ml falcon tubes containing 100 g/L PEG 8000 (Sigma Aldrich) and 22.5 g/L NaCl (Sigma Aldrich), followed by centrifugation at 12,000 g for 1 h 30 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was carefully removed and an additional centrifugation step was carried out in order to remove the remaining liquid (12,000 g, 5 min, 4 °C). The pellet was resuspended in 400 µl molecular biology grade water (Sigma Aldrich) and 400 µl CTAB (Hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide; Promega) buffer. Prior to the RNA extraction, 40 µl of Proteinase K (Promega) were added to each tube and inverted carefully in order to obtain a homogenous suspension. The suspension was further transferred to a tube containing disruptor beads and run on FastPrep24 machine for 40 s at 6 m/s. Subsequently, 400 µl of each sample were used for further RNA extraction. The RNA extraction was performed on Maxwell® RSC AS4500 (Promega) device using Viral RNA/DNA Concentration and Extraction Kit from Wastewater (Promega). The SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA was eluted in 100 µl TE buffer.

2.3. RT-qPCR analysis

The quantitative assessment of SARS-CoV-2 RNA GC in wastewater samples was performed with the ViroReal® Kit SARS-CoV-2 & SARS (Ingenetix, Vienna, Austria) on a QuantStudio 6 Pro-instrument (Applied Biosystems®, Thermo Fisher Scientific) targeting a highly conserved region of the nucleocapsid protein gene (N gene). A standard curve for absolute quantification was obtained using serial dilutions (101 to 105 copies/reaction) of a synthetic RNA template (positive control - PC) containing the target sequence. The reaction mixture contains 4 µl molecular biology grade water (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 5 µl of Master Mix (Ingenetix), 1 µl of SARS-CoV-2 Multiplex Assay Mix (comprising the primers and the probe; Ingenetix) and 10 µl RNA template. Thermal cycling conditions were as follow: reverse transcription at 50 °C for 15 min, initial denaturation at 95 °C for 20 s, followed by 45 cycles at 95 °C for 5 s and 60 °C for 30 s. All RT-qPCR reactions were performed in duplicates in a total volume of 20 µl/reaction. For each RT-qPCR run, a standard curve containing the five dilution steps in duplicate and two negative controls (molecular biology grade water was added to the reaction mixture) were included.

2.4. RT-qPCR assay performance, primer set validation and recovery efficiency

Assay linearity, limit of detection (LoD), inter- and intra-assay precision were assessed by Ingenetix (Vienna, Austria) (detailed information regarding the results are given in the Supplementary Information file). An internal positive control (IPC) was employed to estimate the RNA extraction efficiency and to detect inhibition during RT-qPCR reaction. Each tested sample was seeded with 1 µl IPC of known concentration (6 × 105 copies/µl) prior to RNA extraction and the recovery efficiency was calculated as follows: Recovery efficiency [%] = (IPC recovered / IPC seeded) x 100. For each RNA extraction run, a non-template control (NTC) was included by adding IPC (6 × 105 copies/µl) to molecular biology grade water and further used it as reference sample. RT-qPCR inhibition was assessed by comparing the IPC-cycle threshold (Ct) value of the seeded wastewater sample with the IPC non-template control Ct value. A threshold difference of ≤2 cycles was indicative for no inhibition (Staley et al., 2012).

SARS-CoV-2 primer set used for RT-qPCR quantification was subjected to validation by whole genome sequencing based mutation analysis for the binding sites (details in SI). The analysis revealed that only five mutations within the binding site of any of the used primers end probes were observed within the sequenced samples. None of the observed mutations occurred in more than 2 samples or exceeded a frequency of 0.1, virtually excluding a systematic bias of the applied RT-qPCR set up in the quantification of variants occurring in the Vienna wastewater in the considered time period (Figure S1 – SI).

Recovery efficiency of SARS-CoV-2 GC in wastewater samples average value was 57.71% ± 8.5%. For the RT-qPCR results, a threshold value of 40 cycles was implemented. All tested samples were considered positive and presented Ct values were below the cut off limit, varying between 27 and 35 cycles (Figure S2 – SI), with an average PCR efficiency of 95.51% and 101.02% for IPC and PC respectively. No PCR inhibition was detected for any of the tested samples.

2.5. Data analysis

The raw absolute number of SARS-CoV-2 RNA GC in wastewater inflow samples was used to calculate the final concentrations reported to the population equivalent by applying the data normalization to total nitrogen (TN), frequently used in WBE (Been et al., 2014; van Nuijs et al., 2011). An estimated excreted value of 11 g TN was taken as value excreted per person per day in wastewater (EPA, 2002). TN was measured in the inflow wastewater samples, following the standard EN ISO 20236:2018 and the normalized SARS-CoV-2 genome copies per TN population equivalent (PE11) was calculated by the following formula:

| (1) |

where: TN – total nitrogen; PE11 – 11 g TN per population equivalent (detailed explanation of the formula in SI – Equations S1; S2; S3).

Considering environmental factors such as rain events, temperature fluctuations, hydraulic retention time in the sewerage system, “soft” smooth data analysis by rbf (radial basis functions with factor 0.25) (Myers, 1999) was implemented to closer estimate the number of SARS-CoV-2 GC released per person for the days where no sampling was done.

In order to be representative, as epidemiological data, the 14 days incidence was taken into consideration. The calculated incidence number was considered as total sum of new infected persons reported in the past 14 days and – assuming a duration of 14 days until recovery from the COVID disease – is considered to represent the shedding duration via stool into wastewater (Li et al., 2020a).

2.6. Whole genome sequencing and data analysis

Enriched RNA extracts from the wastewater samples were subjected to viral whole genome sequencing as described by Popa et al. (2020). In brief, genomic RNA was amplified using the ARTIC SARS-CoV-2 primer set V3, applying 35 PCR cycles to cope with high Ct value samples and sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 sequencer in 2 × 250 bp paired-end mode to an average of 2.6 M reads per sample. Reads were demultiplexed, quality controlled (FastQC) (Andrews, 2010) and adapter trimmed (bbduk) (Bushnell et al., 2017). bbmerge (Bushnell et al., 2017) was used to correct sequences in overlapping regions of the same mate pair. This way quality-controlled reads were mapped against a joint human (hg38) and SARS-CoV-2 (NC_045512.2) genome using bwa-mem. Variants were detected and quantified using the tool LoFreq (Wilm et al., 2012), including a realignment step, using its implementation of the Viterbi algorithm. Samples with less than 40% of the genome covered with at least 10 reads were omitted entirely. In the remaining samples, variants with an allele frequency below 0.01 and sites with a read coverage less than 250 reads, were excluded. The consensus sequence was constructed using samtools mpileup and bcftools (Li, 2011) and categorized according its SARS-CoV-2 lineage (Rambaut et al., 2020a) using the software Pangolin (github.com/cov-lineages/pangolin). For the quantification of the alpha lineage the specific markers applied are depicted in Table S2 in Supplementary Information.

2.7. Clinical/epidemiological data

SARS-CoV-2 Wuhan-1 strain and alpha lineage epidemiological data for Vienna, Austria is updated on a daily or weekly base on the AGES (Austrian Agency for Health and Food Safety) Dashboard (https://covid19-dashboard.ages.at/dashboard.html) and main website (https://www.ages.at/themen/krankheitserreger/coronavirus/sars-cov-2-varianten-in-oesterreich/). Out of the publicly available data, we retrieved the Vienna specific information and used it for downstream analysis. 14 days incidence data was taken into consideration and compared with the SARS-CoV-2 GC in wastewater normalized to population equivalent (PE11). Alpha lineage percentages in clinical samples, retrieved from WGS data, were further used for correlation and comparability evaluation with its share in the wastewater samples.

Statistical analysis

Statistical data analysis and plots were performed in SigmaPlot v14.0. Non-linear regression sigmoid curve was obtained using a 3-parameter formula (Equation S4 in SI) by applying a dynamic fitting regression.

3. Results

3.1. SARS-CoV-2 concentration in wastewater samples and epidemiological data

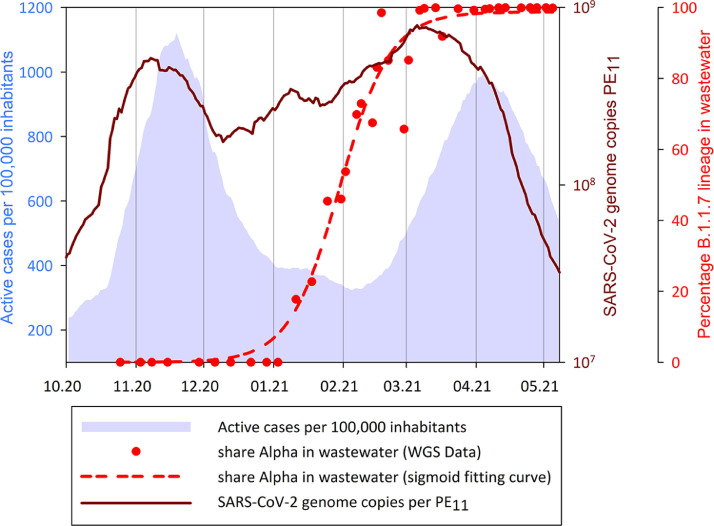

SARS-CoV-2 prevalence in wastewater presents similar fluctuations as incidence data and an upward / downward trend is observed initially in the sewage samples followed, after a time-lag, by the clinical active cases per 100,000 inhabitants Fig. 1. depicts the daily SARS-CoV-2 concentrations reported to the population equivalent (PE11) for the period under specific investigation in this paper (whole dataset Figure S4 – SI), the percentage of alpha variant in wastewater and the active cases per 100,000 inhabitants.

Fig. 1.

Total SARS-CoV-2 concentration per ml per day load calculated to the active cases, in wastewater samples (brown smooth data line); Alpha lineage percentage in wastewater samples (non-linear regression model based on a dynamic fitting curve - Rsqr = 0.9876 - dashed red line and WGS data – red dots) and active clinical cases per 100,000 inhabitants (blue area). Period considered: October 2020 - May 2021.

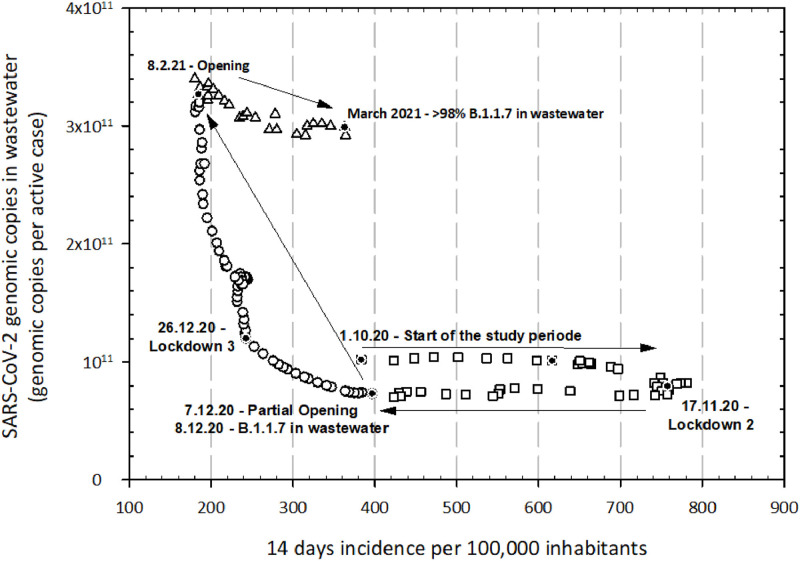

During the study period, from October 2020 to May 2021, SARS-CoV-2 concentration in wastewater reported to PE11 ranged from 5.01 × 107 to 1.10 × 109 GC (Fig. 1) while comparing with its prevalence calculated per active case, it ranged from 1 × 1011 to 3.5 × 1011 GC (Fig. 2 ). For the same period, the incidence varied from 237 to 1121 active cases per 100,000 inhabitants with two peaks in November and April (Data available on AGES website), corresponding the time right before the onset of the 2nd wave (November 11th 2020) and lockdown in the Eastern part of Austria (including Vienna) (April 1st 2021).

Fig. 2.

Schematic representation (smooth data) of the 14 days incidence per 100,000 inhabitants (x-axis) and SARS-CoV-2 GC in wastewater per active case (y-axis) during the study period; lockdowns and openings are marked on the graph. Three important periods are outlined: at the beginning of the study (squares) when the SARS-CoV-2 GC remain rather constant but the 14 days incidence fluctuates; the second period highlighted by the boost of SARS-CoV-2 shedding per person in wastewater (bullets) during the 3rd lockdown and 14 days incidence continues to decline; last part of the study, when the viral shedding per person stays rather constant again but active cases increase (triangles).

For 8 months from the pandemic onset, SARS-CoV-2 concentrations in wastewater exhibit a rather similar trend as epidemiological data, represented by the daily active cases reported to 100,000 inhabitants (Figure S4 – SI). Starting from November 2020, the concentration of the virus in the sewage samples showed a downward trend, along with the number of the confirmed clinical cases (Fig. 1). On November 11th 2020, the 2nd lockdown commenced in Vienna, followed by the 3rd one on December 26th 2020 (with a break in between of 20 days without constraints); restrictions that are highlighted by a drop in the confirmed active cases per 100,000 inhabitants from 1100 to less than 400 clinical Covid-19 cases until January 2021. During this period, the incidence ranged from 406 to 908 with a mean value of 582 active cases per day per 100,000 persons. At the beginning of December, SARS-CoV-2 concentration in wastewater started to increase, while the confirmed active cases per day continued to descend. In contrast to the epidemiological data, SARS-CoV-2 concentration in the sewage samples continued to increase until March 2021, with fluctuations within the same order of magnitude. Over the study period, the average SARS-CoV-2 concentration in the wastewater samples is 3.44 × 108 GC per PE11. After the lockdown has terminated (February 8th 2021) a noticeable boost in the incidence of Covid-19 cases can be observed, followed by an overlap of SARS-CoV-2 concentration and incidence per 100,000 inhabitants at the beginning of April 2021. Taking into account the lockdown measures and the increasing rate of vaccinated persons, a decline in the wastewater viral RNA can be noticed starting in April, followed by the epidemiological data with a short delay.

Considering the increase of SARS-CoV-2 concentration in wastewater, following an upward trend during the same period of a steady decrease in the clinical data, raised the question of the explanation behind this state that was observed for 2 months (December 8th 2020 until beginning of February 2021). After excluding methodological issues, the viral shedding per active case was calculated. The total load of the SARS-CoV-2 expressed in GC per mL was multiplied with the wastewater flow of the specific day and divided by the active cases (recalculated from the 14 days incidence per 100,000 persons using the actual population). The resulting number illustrates the average viral shedding per infected person per day Fig. 2. exhibits the values calculated for each day during the discussed period, plotted versus the 14 days incidences per 100,000 inhabitants, as measure for infected persons shedding the virus reported for the same day. It was expected, that the shedding per person would remain constant, resulting in roughly identical values on the Y axis independent on the clinical data. Surprisingly, the numbers show a pattern that deviates from expectations resulting in the definition of three phases.

At the beginning of our study period, SARS-CoV-2 concentration reported to the 14 days incidence remained stable at 1011 GC, while the 14 days incidence per 100,000 inhabitants increases from approximately 400 to 800 active cases. The onset of the 2nd lockdown (November 17th 2020) led to a decrease in the incidence but the viral concentration shed by one infected person stayed rather stable in the tested wastewater samples. In contrast, starting with December 2020, a boost in the viral RNA concentration could be observed in the wastewater that resulted in an increase in the number of GCs per active case too. In that phase, the incidence only showed a small fluctuation, basically decreasing form 400 to 250 active cases per 14 days, until the 3rd lockdown started (December 26th 2020). Interesting, afterwards, the 14 days incidence stabilized at around 200 active cases per 14 days for one month and half, while the SARS-CoV-2 concentration increased three times in the same period (from 1 × 1011 to 3 × 1011 GC per 14 days incidence). After the relaxation of the restrictions, the incidence quickly started to increase reaching 400 active cases per 14 days in one month again. At the same time SARS-CoV-2 shedding per active case remains stable again.

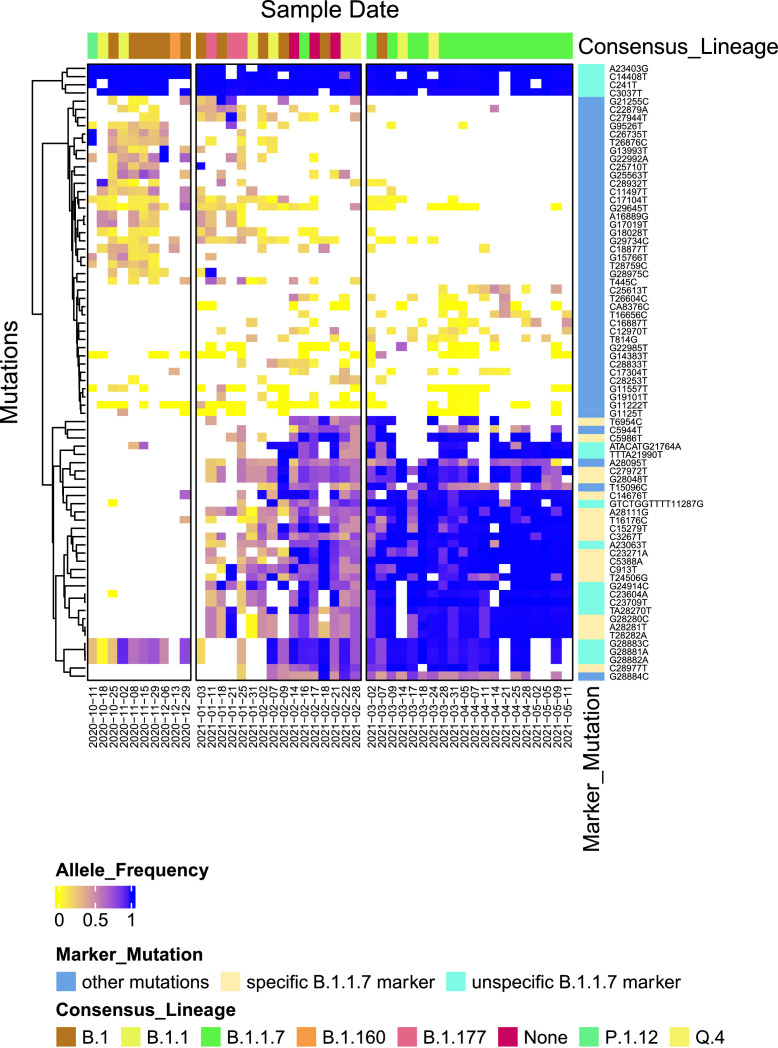

3.2. Signature mutations for alpha lineage and their frequency in wastewater samples

Fig. 3 displays a detailed analysis based on individual mutations and their relative abundance in the wastewater samples by revealing a consistent and more nuanced picture. A block of around 23 mutations which characterize the period before January 2021, but never reach complete fixation in the population, are slowly phasing out during January/February. In the same period around 30 mutations are slowly emerging and reaching fixation by March 2021. All of these mutations are signature mutations of the alpha lineage.

Fig. 3.

Graphical representation of all mutations observed in the wastewater from Vienna until May 2021, which are detected in at least six samples, in at least 3 consecutive timepoints, and with an allele frequency of at least 0.3 in at least one sample. The top annotation bar depicts the assigned pangolin lineage of the consensus sequence of the respective sample. The annotation on the righthand side depicts the observed mutation and a categorization if this mutation is a marker for alpha (if present in at least 90% of all genomes from GISAID as of May 20th, 2021 with the lineage assignment alpha). Mutations which are found to be markers exclusive for alpha are denoted as “specific”. If the marker is also associated with other lineages, it is denoted as “unspecific”.

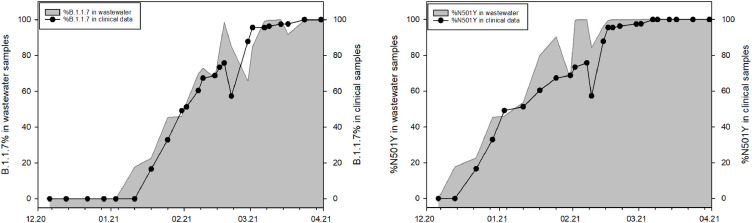

3.3. Percentages of alpha lineage and N501Y mutation in clinical and wastewater samples in Vienna, Austria derived from WGS data

On January 4th 2021, the first patient was officially confirmed and reported by the health authorities with SARS-CoV-2 alpha variant in Vienna, Austria. Although the first case with alpha variant was detected around Christmas time, the official confirmation from sequencing data was necessary in order to report it as positive for the alpha lineage. The alpha lineage increased gradually in clinical samples from 1% on 10th of January 2021 to 49% on 1st of February 2021, reaching 75% on 15th of March 2021.

The atypical descending trend observed in clinical data concomitant with the increasing tendency of the SARS-CoV-2 GC in wastewater samples starting with Dec 8th 2021 (Fig. 1) gave rise to data interpretation questions. Regression model analysis (dashed line Fig. 1) for the alpha variant and N501Y mutation percentages obtained from sequencing (gray area in Fig. 4 ) matched in both data sets from clinical and wastewater samples for the same study period. The percentage of alpha in wastewater samples reached almost 100% in only 10 weeks since its first detection, while a similar share in clinical samples was visible after 13 weeks from the first confirmed case.

Fig. 4.

Percentage of alpha lineage and N501Y mutation in clinical (black line and scatter) and wastewater (gray area) samples retrieved from WGS data and non-linear regression model describing a dynamic fitting curve based on 3-parameter function to estimate the date when the variant emerged in Vienna sewage samples.

4. Discussions

This study describes the temporal quantitative analysis of SARS-CoV-2 genome and alpha lineage in wastewater samples in Vienna, Austria. During the study period we determined the total SARS-CoV-2 concentration and alpha variant share in 73 wastewater samples collected between October 4th 2020 and May 5th 2021 from Vienna WWTP. Further, we compared the epidemiological data, active cases per 100,000 inhabitants, with the wastewater data reported to the population equivalent (PE11), and based on a non-linear regression model, the estimated date when alpha variant appeared in the sewage samples from Vienna was assessed.

The present paper considers the TN as human biomarker to estimate the population connected to the sewerage system (PE11) in Vienna. One of the first WBE studies to detect and track SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater in Europe was conducted by Medema and collaborators in the Netherlands (Medema et al., 2020). Since the onset of the pandemic, the wastewater surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 became a monitoring routine worldwide. The observed SARS-CoV-2 concentrations in untreated wastewater ranged from 105 to 1011 GC/mL (Ahmed et al., 2020a; D'Aoust et al., 2021; Peccia et al., 2020; Wurtzer et al., 2021). Similarly, in our manuscript, the observed SARS-CoV-2 concentrations in Vienna wastewater over the whole monitoring period (Figure S4 – SI) ranged from 3.59 × 107 in May 2021 (5.01 × 107 in April 2020) to respectively 1.10 × 109 GC/mL in March 2021.

For the first one and half month of the study (October 2020 – November 15th 2020), a similar upward SARS-CoV-2 pattern was observed in both wastewater samples and active clinical cases per 100,000 inhabitants. The increase in the wastewater signal fits the reported clinical cases (Fig. 1). Similar results were observed by Wilton et al. (2021), Foladori et al. (2020) and Randazzo et al. (2020). In contrast, for the downward trend, the data correspond only for a limited period. Interesting, by December 8th the number of infected persons continue the decline but the SARS-CoV-2 concentration in sewage samples started to raise again. One explanation for the resulting changes of SARS-CoV-2 GCs per active case would be a different shedding rate by infected individuals or different virion stability of circulating variants in the respective period in wastewater. To elucidate the potential role of variant specific mutations regarding the upward trend of SARS-CoV-2 concentration, we characterized the patterns of prevailing virus variants in the wastewater samples. The main outcome is that the mutations present at the beginning of the study period disappear within one month and new ones, signature mutations for alpha variant, showed up and get fixed in the population by the end of March (Fig. 3).

Comparable to our outcome, recent studies highlight the potential contribution of wastewater monitoring for the early detection of alpha lineage by signature mutations (La Rosa et al., 2021; Wilton et al., 2021) La Rosa et al. (2021). report the first evidence of VOCs identification, based on signature mutations, in wastewater samples from Italy using nested RT-PCR together with Sanger sequencing technique Washington et al. (2021). describe the emergence and dynamic of the alpha lineage in the United States in clinical samples, results which show that the variant was already present in different states in November 2020 (Washington et al., 2021). Considering the association of D614G and N501Y mutations with a higher viral load and transmissibility (Korber et al., 2020; Volz et al., 2021), we presume that the different development of the two signals (wastewater and clinical data) may correspond with the emergence of alpha lineage. Recent studies underline our statement that SARS-CoV-2 alpha variant presents a higher viral load in the respiratory tract as well as in stool (Frampton et al., 2021; Kidd et al., 2021; Rosenke et al., 2021). In accordance with our results, Wilton et al. (2021) correlate the emergence of alpha variant with high levels of viral RNA found in sewage samples from London (Wilton et al., 2021). The dissemination of the alpha lineage appears to have a more accelerated spread than SARS-CoV-2 Wuhan-1 strain in human population (Korber et al., 2020; Volz et al., 2021; Wilton et al., 2021).

The result of the sigmoid regression model derived from sequencing data indicates the first occurrence of the alpha variant in Vienna sewage sample started around December 8th 2020. In the same period, a decoupling of the wastewater signal and the epidemiological incidence was observed (Fig. 1) and the average amount of GC in wastewater shed by one infected person started to increase (Fig. 2). The modelled data show that on December 8th the alpha lineage was present in Vienna sewage samples in a share of about 1%. When the initial clinical case was confirmed, the variant portion in wastewater was already at 15% (Fig. 1; Figure S5 - SI). So within one month, the percentage increases to 15% in order to reach 50% after another 3 weeks. At the beginning of March 2021, the SARS-CoV-2 alpha lineage gets to 90% of the total wastewater samples tested, underlining the fast dissemination of the new variant among the population (Table S4 – SI). Nevertheless, data interpretation should consider different factors such as environmental conditions (rainfall and snowfall events, temperature, pH, hydraulic retention time in the sewers) or chemicals (disinfectants and detergents) as they may interfere with the final SARS-CoV-2 GC reported (Polo et al., 2020).

The well-known fact that temperature variations affect the stability of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater led to suspicions regarding the effect of temperature fluctuation in the Vienna sewerage system. As it is already shown in literature, SARS-CoV-2 viral particles display different behavior influenced by temperature in sewage samples Ahmed et al. (2020). tested the stability of SARS-CoV-2 in untreated wastewater samples at four different temperatures. The main outcome of their study is that SARS-CoV-2 viral particles have an extended persistence at 4 and 15 °C, up to 27 and 20 days respectively Ahmed et al. (2020b). In contrast, Wurtzer et al. (2021) observed no effect on SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA detection after incubation for 24 h in a range of temperature between 4 °C and 40 °C. The authors defined a period of 7 days persistence of total viral RNA at 4 °C (Wurtzer et al., 2021). Noteworthy, only temperature values below 15 °C led to a slight increase in SARS-CoV-2 concentration in wastewater samples from Vienna (Figure S5 – SI). As the flow time of the wastewater in Vienna sewerage system is rather short (average of about two hours), a temperature effect on the decay of the viral particles, should be rather small. Based on the combination of a short flow time and only small fluctuations of temperature (max. difference of 7 °C; see Figure S5 – SI) in the wastewater samples during the time period investigated, we conclude the emergence of the new variant being responsible for the increased wastewater signal observed and thus the presence of alpha already well before identification in clinical samples.

Overall, SARS-CoV-2 concentration in untreated wastewater from Vienna was influenced mainly by the emergence of alpha lineage, considering the association of different signature mutations with higher viral loads and only a small effect may be attributed to fluctuations in temperature.

5. Conclusions

Considering that for the clinical cases the results can be delayed for few days due to the time required for symptoms to initiate and testing capacity, WBE proves to be the fastest and advantageous method to provide a quick snapshot of SARS-CoV-2 circulating variants in a certain catchment.

The real number of infected persons is difficult to recalculate with accuracy due to the shedding values which are dependent on the specific SARS-CoV-2 variant and the constant change in lineage composition in wastewater

Different variants may display a distinct behavior of SARS-CoV-2 concentrations in wastewater, therefore a factor of extrapolation should be considered carefully in drawing the final conclusions.

Wastewater represents a complex matrix thus, the key parameters that should be rigorously considered are represented by the viral concentration and circulating SARS-CoV-2 variants in wastewater samples, representative samples and population normalization.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Elena Radu: Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. Amandine Masseron: Investigation. Fabian Amman: Investigation, Writing – original draft. Anna Schedl: Investigation. Benedikt Agerer: Investigation. Lukas Endler: Investigation. Thomas Penz: Investigation. Christoph Bock: Investigation. Andreas Bergthaler: Resources, Writing – review & editing. Julia Vierheilig: Writing – review & editing. Peter Hufnagl: Methodology, Resources. Irina Korschineck: Methodology, Resources. Jörg Krampe: Writing – review & editing. Norbert Kreuzinger: Supervision, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The study was funded by the program “CSI – Abwasser” initiated by the City of Vienna.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the wastewater treatment plant operators and staff for their invaluable support during the sampling campaigns and City of Vienna for funding. Benedikt Agerer acknowledges the support received from the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) DK W1212.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.watres.2022.118257.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- Ahmed W., Angel N., Edson J., Bibby K., Bivins A., et al. First confirmed detection of SARS-CoV-2 in untreated wastewater in Australia: a proof of concept for the wastewater surveillance of COVID-19 in the community. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;728 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed W., Bertsch P.M., Bibby K., Haramoto E., Hewitt J., Huygens F., Gyawali P., Korajkic A., Riddell S., Sherchan S.P., Simpson S.L., Sirikanchana K., Symonds E.M., Verhagen R., Vasan S.S., Kitajima M., Bivins A. Decay of SARS-CoV-2 and surrogate murine hepatitis virus RNA in untreated wastewater to inform application in wastewater-based epidemiology. Environ. Res. 2020;191 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.110092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alygizakis N., Markou A.N., Rousis N.I., Galani A., Avgeris M., Adamopoulos P.G., Scorilas A., Lianidou E.S., Paraskevis D., Tsiodras S., Tsakris A., Dimopoulos M.A., Thomaidis N.S. Analytical methodologies for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater: protocols and future perspectives. Trends Analyt. Chem. 2021;134 doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2020.116125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, S. 2010. FastQC - A quality control tool for high throughput sequence data, http://bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/, Babraham Bioinformatics; 2010).

- Been F., Rossi L., Ort C., Rudaz S., Delemont O., Esseiva P. Population normalization with ammonium in wastewater-based epidemiology: application to illicit drug monitoring. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014;48(14):8162–8169. doi: 10.1021/es5008388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushnell B., Rood J., Singer E. BBMerge - Accurate paired shotgun read merging via overlap. PLoS One. 2017;12(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0185056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crits-Christoph A., Kantor R.S., Olm M.R., Whitney O.N., Al-Shayeb B., Lou Y.C., Flamholz A., Kennedy L.C., Greenwald H., Hinkle A., Hetzel J., Spitzer S., Koble J., Tan A., Hyde F., Schroth G., Kuersten S., Banfield J.F., Nelsonb K.L. Genome Sequencing of Sewage Detects Regionally Prevalent SARS-CoV-2 Variants. mBio. 2021;12(1):e02703–e02720. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02703-20. 2021 Jan-Feb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Aoust P.M., Mercier E., Montpetit D., Jia J.J., Alexandrov I., Neault N., Baig A.T., Mayne J., Zhang X., Alain T., Langlois M.A., Servos M.R., MacKenzie M., Figeys D., MacKenzie A.E., Graber T.E., Delatolla R. Quantitative analysis of SARS-CoV-2 RNA from wastewater solids in communities with low COVID-19 incidence and prevalence. Water Res. 2021;188 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2020.116560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daughton C. The international imperative to rapidly and inexpensively monitor community-wide Covid-19 infection status and trends. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;726 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EPA, U. 2002. Onsite Wastewater Treatment Systems Manual.

- Foladori P., Cutrupi F., Segata N., Manara S., Pinto F., Malpei F., Bruni L., La Rosa G. SARS-CoV-2 from faeces to wastewater treatment: what do we know? A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;743 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontenele R.S., Kraberger S., Hadfield J., Driver E.M., Bowes D. High-throughput sequencing of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater provides insights into circulating variants. medRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2021.117710. (PMID: 33501452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frampton D., Rampling T., Cross A., Bailey H., Heaney J., Byott M., Scott R., Sconza R., Price J., Margaritis M., Bergstrom M., Spyer M.J., Miralhes P.B., Grant P., Kirk S., Valerio C., Mangera Z., Prabhahar T., Moreno-Cuesta J., Arulkumaran N., Singer M., Shin G.Y., Sanchez E., Paraskevopoulou S.M., Pillay D., McKendry R.A., Mirfenderesky M., Houlihan C.F., Nastouli E. Genomic characteristics and clinical effect of the emergent SARS-CoV-2 B1.1.7 lineage in London, UK: a whole-genome sequencing and hospital-based cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2021;21(9):1246–1256. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00170-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerrity D., Papp K., Stoker M., Sims A., Frehner W. Early-pandemic wastewater surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 in Southern Nevada: methodology, occurrence, and incidence/prevalence considerations. Water Res. X. 2021;10 doi: 10.1016/j.wroa.2020.100086. github.com/cov-lineages/pangolin. https://covid19-dashboard.ages.at/dashboard.html. https://covid19.who.int/. https://www.ages.at/themen/krankheitserreger/coronavirus/sars-cov-2-varianten-in-oesterreich/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J., He, C.-.L., Gao, Q.-.Z., Zhang, G.-.J., Cao, X.-.X., Long, Q.-.X., Deng, H.-.J., Huang, L.-.Y., Chen, J., Wang, K., Tang, N. and Huang, A.-.L. 2020. D614G mutation of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein enhances viral infectivity.

- Khateeb J., Li Y., Zhang H. Emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern and potential intervention approaches. Crit. Care. 2021;25(1):244. doi: 10.1186/s13054-021-03662-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd M., Richter A., Best A., Cumley N., Mirza J., Percival B., Mayhew M., Megram O., Ashford F., White T., Moles-Garcia E., Crawford L., Bosworth A., Atabani S.F., Plant T., McNally A. S-Variant SARS-CoV-2 Lineage B1.1.7 Is Associated With Significantly Higher Viral Load in Samples Tested by TaqPath Polymerase Chain Reaction. J. Infect. Dis. 2021;223(10):1666–1670. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiab082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korber B., Fischer W.M., Gnanakaran S., Yoon H., Theiler J., Abfalterer W., Hengartner N., Giorgi E.E., Bhattacharya T., Foley B., Hastie K.M., Parker M.D., Partridge D.G., Evans C.M., Freeman T.M., de Silva T.I., Sheffield C.-G.G., McDanal C., Perez L.G., Tang H., Moon-Walker A., Whelan S.P., LaBranche C.C., Saphire E.O., Montefiori D.C. Tracking Changes in SARS-CoV-2 Spike: evidence that D614G Increases Infectivity of the COVID-19 Virus. Cell. 2020;182(4):812–827. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.06.043. e819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Rosa G., Mancini P., Bonanno Ferraro G., Veneri C., Iaconelli M., Lucentini L., Bonadonna L., Brusaferro S., Brandtner D., Fasanella A., Pace L., Parisi A., Galante D., Suffredini E. Rapid screening for SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern in clinical and environmental samples using nested RT-PCR assays targeting key mutations of the spike protein. Water Res. 2021;197 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2021.117104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. A statistical framework for SNP calling, mutation discovery, association mapping and population genetical parameter estimation from sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2011;27(21):2987–2993. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Wang Y., Ji M., Pei F., Zhao Q., Zhou Y., Hong Y., Han S., Wang J., Wang Q., Li Q., Wang Y. Transmission Routes Analysis of SARS-CoV-2: a systematic review and case report. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020;8:618. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.00618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q., Wu J., Nie J., Zhang L., Hao H., Liu S., Zhao C., Zhang Q., Liu H., Nie L., Qin H., Wang M., Lu Q., Li X., Sun Q., Liu J., Zhang L., Li X., Huang W., Wang Y. The impact of mutations in SARS-CoV-2 spike on viral infectivity and antigenicity. Cell. 2020;182(5):1284–1294. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.07.012. e1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luan B., Wang H., Huynh T. Enhanced binding of the N501Y-mutated SARS-CoV-2 spike protein to the human ACE2 receptor: insights from molecular dynamics simulations. FEBS Lett. 2021;595(10):1454–1461. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.14076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, D., Weaver, S., Tegally, H., San, E.J., Wilkinson, E., Giandhari, J., Sureshnee Naidoo, Pillay, Y., Singh, L., Lessells, R.J., Oliveira, T.d., NGS-SA Wertheim, J., Lemey, P., MacClean, O., Robertson, D., Murrell, B. and Pond, S.L.K. 2020. The emergence and ongoing convergent evolution of the N501Y lineages coincided with a major global shift in the SARS-Cov-2 selective landscape.

- Medema G., Heijnen L., Elsinga G., Italiaander R., Brouwer A. Presence of SARS-Coronavirus-2 RNA in sewage and correlation with reported COVID-19 prevalence in the early stage of the epidemic in The Netherlands. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2020;7(7):511–516. doi: 10.1021/acs.estlett.0c00357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers D.E. Smoohing and interpolation with radial basis functions. Trans. Modell. Simul. 1999;22 [Google Scholar]

- Nalla K.A., Casto Amanda M., Huang Meei-Li W., Perchetti Garrett A., Sampoleo Reigran, Shrestha Lasata, Wei Yulun, Zhu Haiying, Jerome Keith R., Greningera A.L. Comparative performance of SARS-CoV-2 detection assays using seven different primer-probe sets and one assay kit. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2020;58(6) doi: 10.1128/JCM.00557-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peccia J., Zulli A., Brackney D.E., Grubaugh N.D., Kaplan E.H. Measurement of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater tracks community infection dynamics. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020;38(10):1164–1167. doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0684-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng L., Liu J., Xu W., Luo Q., Chen D., Lei Z., Huang Z., Li X., Deng K., Lin B., Gao Z. SARS-CoV-2 can be detected in urine, blood, anal swabs, and oropharyngeal swabs specimens. J. Med. Virol. 2020;92(9):1676–1680. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polo D., Quintela-Baluja M., Corbishley A., Jones D.L., Singer A.C., Graham D.W., Romalde J.L. Making waves: wastewater-based epidemiology for COVID-19 - approaches and challenges for surveillance and prediction. Water Res. 2020;186 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2020.116404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popa A., Genger J.-.W., Nicholson M.D., Penz T., Schmid D., Aberle S.W., Agerer B., Lercher A., Endler L., Colaço H., Smyth M., Schuster M., Grau M.L., Martínez-Jiménez F., Pich O., Borena W., Pawelka E., Keszei Z., Senekowitsch M., Laine J., Aberle J.H., Redlberger-Fritz M., Karolyi M., Zoufaly A., Maritschnik S., Borkovec M., Hufnagl P., Nairz M., Weiss G.n., Wolfinger M.T., Laer D.v., Superti-Furga G., Lopez-Bigas N., Puchhammer-Stöckl E., Allerberger F., Michor F., Bock C., Bergthaler A. Genomic epidemiology of superspreading events in Austria reveals mutational dynamics and transmission properties of SARS-CoV-2. Sci. Transl. Med. 2020;12(573) doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abe2555. 2020 Dec 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rambaut A., Holmes E.C., O'Toole A., Hill V., McCrone J.T., Ruis C., du Plessis L., Pybus O.G. A dynamic nomenclature proposal for SARS-CoV-2 lineages to assist genomic epidemiology. Nat. Microbiol. 2020;5(11):1403–1407. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0770-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rambaut, A., Loman, N., Pybus, O., Barclay, W., Barrett, J., Carabelli, A., Connor, T., Peacock, T., Robertson, D.L., Volz, E. and UK, C.-G.C. 2020b. Preliminary genomic characterisation of an emergent SARS-CoV-2 lineage in the UK defined by a novel set of spike mutations.

- Randazzo W., Truchado P., Cuevas-Ferrando E., Simon P., Allende A., Sanchez G. SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater anticipated COVID-19 occurrence in a low prevalence area. Water Res. 2020;181 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2020.115942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenke K., Feldmann F., Okumura A., Hansen F., Tang-Huau T.L., Meade-White K., Kaza B., Callison J., Lewis M.C., Smith B.J., Hanley P.W., Lovaglio J., Jarvis M.A., Shaia C., Feldmann H. UK Alpha variant exhibits increased respiratory replication and shedding in nonhuman primates. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2021;10(1):2173–2182. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2021.1997074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims N., Kasprzyk-Hordern B. Future perspectives of wastewater-based epidemiology: monitoring infectious disease spread and resistance to the community level. Environ. Int. 2020;139 doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staley C., Gordon K.V., Schoen M.E., Harwood V.J. Performance of two quantitative PCR methods for microbial source tracking of human sewage and implications for microbial risk assessment in recreational waters. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012;78(20):7317–7326. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01430-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Nuijs A.L., Mougel J.F., Tarcomnicu I., Bervoets L., Blust R., Jorens P.G., Neels H., Covaci A. Sewage epidemiology–a real-time approach to estimate the consumption of illicit drugs in Brussels, Belgium. Environ. Int. 2011;37(3):612–621. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volz E., Hill V., McCrone J.T., Price A., Jorgensen D., O'Toole A., Southgate J., Johnson R., Jackson B., Nascimento F.F., Rey S.M., Nicholls S.M., Colquhoun R.M., da Silva Filipe A., Shepherd J., Pascall D.J., Shah R., Jesudason N., Li K., Jarrett R., Pacchiarini N., Bull M., Geidelberg L., Siveroni I., Consortium C.-.U., Goodfellow I., Loman N.J., Pybus O.G., Robertson D.L., Thomson E.C., Rambaut A., Connor T.R. Evaluating the Effects of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Mutation D614G on. Transmissibility Pathogenicity Cell. 2021;184(1):64–75. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.11.020. e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Hu B., Hu C., Zhu F., Liu X., Zhang J., Wang B., Xiang H., Cheng Z., Xiong Y., Zhao Y., Li Y., Wang X., Peng Z. Clinical Characteristics of 138 Hospitalized Patients With 2019 Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia in Wuhan. China. JAMA. 2020;323(11):1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washington N.L., Gangavarapu K., Zeller M., Bolze A., Cirulli E.T., Schiabor Barrett K.M., La Rosa G., Andersen K.G. Emergence and rapid transmission of SARS-CoV-2 ALPHA in the United States. Cell. 2021;184(10):2587–2594. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.03.052. e2587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO 2020a. WHO Director-General's Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020. Available at: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19—11-march-2020.

- WHO 2020b. World Health Organization. Statement on the Second Meeting of the International Health Regulations Emergency Committee Regarding the Outbreak of Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV), 2020. Available at: https://www.who.int/news/item/30-01-2020-statement-on-the-second-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-outbreak-of-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov).

- Wilm A., Aw P.P., Bertrand D., Yeo G.H., Ong S.H., Wong C.H., Khor C.C., Petric R., Hibberd M.L., Nagarajan N. LoFreq: a sequence-quality aware, ultra-sensitive variant caller for uncovering cell-population heterogeneity from high-throughput sequencing datasets. Nucleic. Acids. Res. 2012;40(22):11189–11201. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilton T., Bujaki E., Klapsa D., Fritzsche M., Mate R., Martin J. Rapid increase of SARS-CoV-2 variant Alpha detected in sewage samples from England between October 2020 and January 2021. mSystems. 2021;6(3) doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00353-21. e00353-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F., Zhang J., Xiao A., Gu X., Lee W.L., Armas F., Kauffman K., Hanage W., Matus M., Ghaeli N., Endo N., Duvallet C., Poyet M., Moniz K., Washburne A.D., Erickson T.B., Chai P.R., Thompson J., Alm E.J. SARS-CoV-2 titers in wastewater are higher than expected from clinically confirmed cases. mSystems. 2020;5(4) doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00614-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurtzer S., Waldman P., Ferrier-Rembert A., Frenois-Veyrat G., Mouchel J.M., Boni M., Maday Y., consortium O., Marechal V., Moulin L. Several forms of SARS-CoV-2 RNA can be detected in wastewaters: implication for wastewater-based epidemiology and risk assessment. Water Res. 2021;198 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2021.117183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.