Highlights

-

•

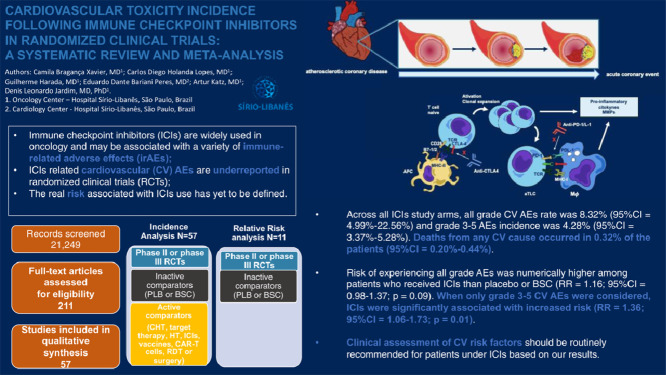

Cardiovascular (CV) adverse effects (AEs) of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) are underreported in clinical trials.

-

•

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate cardiovascular adverse effects incidence among patients with solid tumors receiving ICIs in randomized clinical trials (RCTs).

-

•

All grade CV AEs incidence rate was 8.32% (95% CI = 6.35%−10.53%).

-

•

When only grade 3–5 CV AEs were considered, ICIs were significantly associated with increased risk than placebo or BSC (RR = 1.36; 95% CI = 1.06–1.73; p = 0.01).

-

•

There is satisfactory evidence suggesting awareness for patient's CV signs and symptoms while receiving ICIs in clinical practice .

Keywords: Cardiovascular toxicity; Checkpoint blockade; Immune checkpoint inhibitors; Meta-analysis, abbreviations, AES; Adverse effects, BSC; Best supportive care, CTCAE; Common toxicity criteria, CTLA-4; Cytotoxic t-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4, CV; Cardiovascular, FAERS; U.S. food and drug administration adverse events reporting system, ICIS; Immune checkpoint inhibitors, PRISMA; Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses, RCTs; randomized clinical trials, PD-1; programmed cell death protein 1, PD-L1; programmed cell death ligand 1, RR; relative risk

Abstract

Background

Immune checkpoint inhibitors may be associated with multiple immune-related toxicities. Cardiovascular adverse effects are underreported in clinical trials.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate cardiovascular adverse effects incidence among patients with solid tumors receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors in randomized clinical trials and the relative risk of presenting these effects compared to placebo or best supportive care. The search was conducted through MEDLINE, Embase, and Scopus databases from January 1st, 2010 until July 1st, 2020. Outcomes were reported following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.

Results

57 randomized clinical trials including 12,118 patients were included. All grade CV AEs incidence rate was 8.32% (95% CI = 6.35%-10.53%). When only grade 3–5 CV AEs were considered, ICIs were significantly associated with increased risk than placebo or BSC (RR = 1.36; 95% CI = 1.06–1.73; p = 0.01).

Conclusion

This meta-analysis corroborates the hypothesis of increased CV risk related to immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract

.

Introduction

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) are currently widely used for the therapy of a variety of advanced cancers. Monoclonal antibodies targeting programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1), and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) received regulatory approval in different indications and are also in development for new ones [1]. Hence, their role in clinical practice is expected to increase in the coming years. The efficacy of ICIs is derived from their ability to unleash the host immune system against cancer cells. An unplanned consequence of this mechanism of action is the development of an immune response against normal host cells, leading to immune mediated toxicities [2]. Immune toxicities are more commonly described affecting the pulmonary, gastrointestinal, dermatological and endocrinological systems [3], [4], [5], but rare events may also cause morbidity and mortality.

The PD-1/PD-L1 pathway appears to be particularly important in cardiac protection from T cells. The upregulation of PD-L1 in human myocardium, both on myocytes and endothelium, by interferon-gamma secretion, is evident in the hearts of cancer patients treated with ICIs [6]. Activated T cells further produce large amounts of pro-atherogenic cytokines that may contribute to atherosclerotic plaque growth and destabilization. These findings suggest that cancer patients receiving ICIs therapy could worsen cardiovascular (CV) inflammation and as consequence suffer CV or cerebrovascular events [7].

Cases of myocarditis, heart failure, coronary syndromes, arrhythmias, pericardial disease, and other CV adverse effects (AEs) have been described in patients treated with ICIs alone or in combination [8]. Nevertheless, CV toxicity is underreported in randomized clinical trials (RCTs) and the true risk associated with ICIs use has yet to be defined. Data from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration Adverse Events Reporting System (FAERS) states that 92,073 adverse events secondary to the most prescribed immune checkpoint inhibitors Ipilimumab, Pembrolizumab, and Nivolumab were reported over the last ten years. Among these, only 31 were from cardiovascular nature: 30 were classified as severe (96.77%), and 14 led to death (45.16%) [9] Therefore, our aim was to investigate the incidence and risk of CV toxicities in patients receiving ICIs, using an up-to-date meta-analysis of prospective clinical trials.

Methods

Search methods and study selection

We conducted a systematic review of the literature to identify RCTs testing PD-1, PD-L1, and CTLA-4 inhibitors for solid tumors, either in monotherapy or in combination between them. For incidence estimation of CV AEs, we included phase II and phase III trials regardless of the control arm. For relative risk (RR) assessment, we included phase II or phase III RCTs using best supportive care (BSC) or placebo as comparator. As our intention was to make comparisons, to maintain balance between both ICIs and BSC or placebo arms, we removed single-arm trials from this second phase of the analysis. The search was conducted through MEDLINE, Embase, and Scopus databases from January 1st, 2010 until July 1st, 2020. The search strategy can be found at SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL 1. All data obtained from initial search can be found at SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL 2. Data presented as meeting abstracts without published full-text original articles were included if they comply with all the eligibility criteria mentioned above. In case of more than one publication reporting on the same study, the most recent and comprehensive publication was included in the analysis. Study classification, selection, and duplicate removal were conducted using Rayyan, a web and mobile app for systematic reviews [10]. Trials that did not mention cardiovascular side effects were excluded. Trials that reported zero cardiovascular events were included. Processed data after study selection and duplicate removal can be found at SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL 3.

Data extraction

Data were extracted by two independent reviewers (C.B.X. and G.H.), and discordant cases were analyzed by a third reviewer (D.L.F.J.) Using the used the Rayyan mobile app [10], both authors (C.B.X. and G.H.), did separate evaluation of the trials, assessing if they met the inclusion criteria and removing duplicates. Then, trial name, phase, cancer type, ICIs dose and dosing schedule, and the number of exposed patients were obtained from each arm in each included study. All-grade CV AEs and treatment related deaths data were both extracted according to study information. CV AEs were categorized based on Common Toxicity Criteria (CTCAE) version 4.03 [11] as described in SUPPLEMENTARY TABLE 1. All the process followed Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [12].

Statistical analysis

The principal summary measures were incidence, RR and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Incidence analysis were performed using Metaprop module from STATA v.16.1 [13]. The presence of heterogeneity was evaluated using the Chi2 test, and a random-effects meta-analysis was performed as substantial heterogeneity was observed. The approach allows investigators to address heterogeneity that cannot be obviously attributed to other factors, assuming that the effects being estimated in the different studies follow normal random distribution [14].

The Freeman-Tukey method was applied for the outcome of adverse events incidence and the Clopper-Pearson method was applied for the mortality outcome. The incidence of CV AEs was investigated for all ICIs cohorts and reported by arm with 95% CIs. RR analysis was performed for ICIs cohorts from placebo-controlled or BSC-controlled RCTs using RevMan v.5.4 [15]. Tau2 was incorporated to measure the extent of variation among the effects observed in different studies and perform weight adjustments. Each RCT was categorized as “low-risk” or “high-risk” of bias using predefined quality criteria according to Higgins et Al [16].. Quality assessment in the context of meta-analysis is interchangeable with bias risk assessment and refers to the internal validity of a study [17]. Random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other biases were considered. Bias risk from the included studies is summarized in SUPPLEMENTARY TABLE 2.

Results

Eligible studies and characteristics

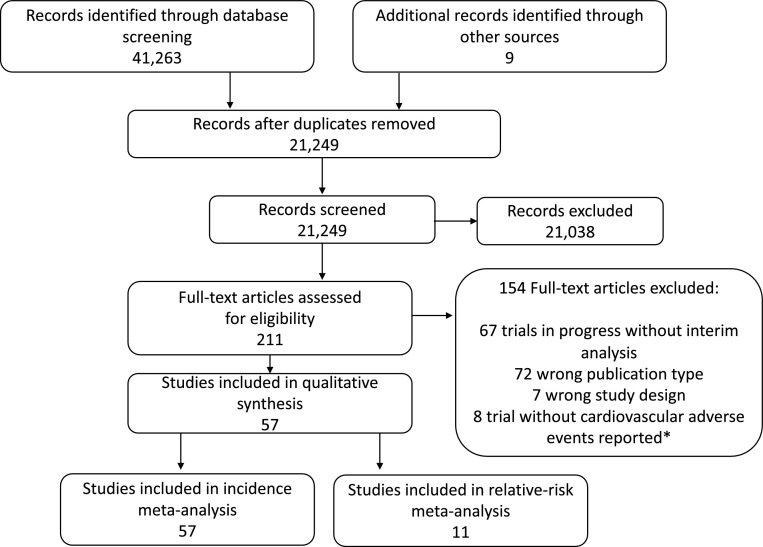

Our initial search yielded a total of 21,249 relevant publications (FIG. 1). After screening and eligibility assessment, we selected 57 clinical trials [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53], [54], [55], [56], [57], [58], [59], [60], [61], [62], [63], [64], [65], [66], [67], [68], [69], [70], [71], [72], [73], [74] that are presented at data set SUPPLEMENTARY TABLE 3. A total of 21,118 patients (67 cohorts from 57 trials) were available for this meta-analysis. Trial distribution included 3 phase II, 1 phase II/III, and 53 phase III RCTs. The most frequent tumor types by number of studies included lung cancer (n = 16; 28.0%), melanoma (n = 13; 22.80%), urothelial carcinoma (n = 6; 10.53%) and gastric cancer (n = 5; 8.77%). While the majority of studies included advanced cancer patients, four RCTs tested ICIs as adjuvant therapy (1 for lung cancer and 3 for melanoma). We categorized the cohorts by ICIs regimen as monotherapy with a PD-1 inhibitor (35 cohorts; 10,241 patients), PD-L1 inhibitor (12 cohorts; 3755 patients), CTLA-4 inhibitor (11 cohorts; 4135 patients), and combination therapy (9 cohorts; 2987 patients). For the RR analysis, we included 11 placebo-controlled or BSC-controlled RCTs. ICIs regimens were likewise categorized as PD-1 inhibitor (5 cohorts; 1452 patients), PD-L1 inhibitor (2 cohorts; 823 patients), CTLA-4 inhibitor (4 cohorts; 1307 patients), and combination therapy (1 cohort; 278 patients). Forty-four studies adequately reported follow-up duration. Amidst this data set, the median follow-up was 12.6 months (6.3–60).

Fig. 1.

– Consort diagram of study selection.

Incidence of cardiovascular adverse events with checkpoint inhibitors

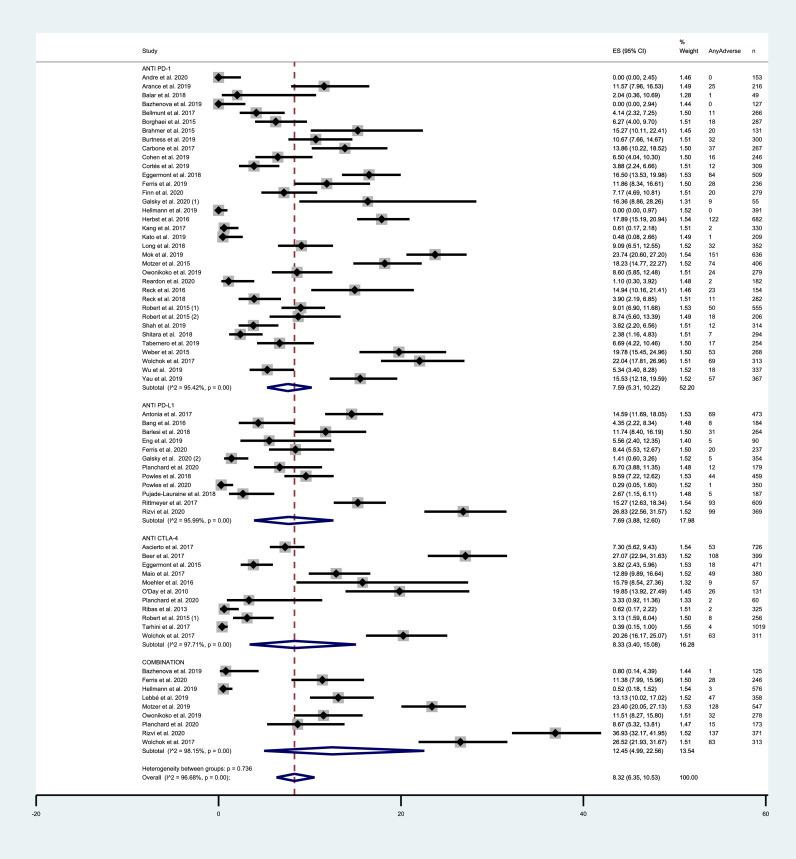

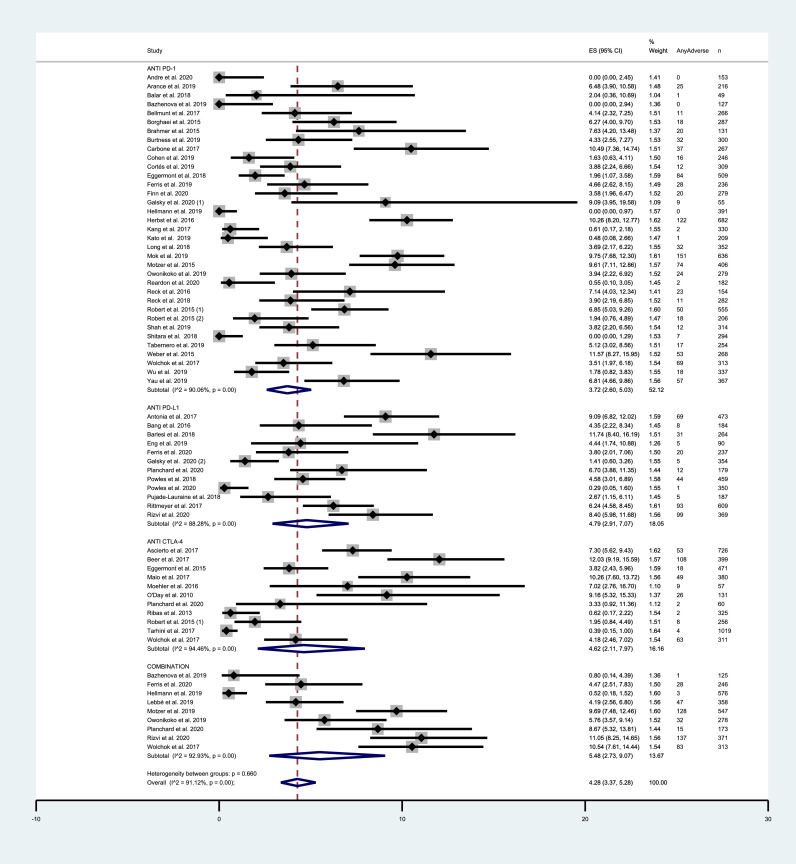

Across all ICIs study arms, incidence of all grade CV events was 8.32% (95% CI = 6.35–10.53%). PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors exhibited similar incidence rates of 7.59% (95% CI = 5.31–10.22%) and 7.69% (95% CI = 3.88–12.60%) respectively. Among trials testing CTLA-4 inhibitors, incidence was 8.33% (95% CI = 3.40–15.08%). Combination therapy exhibited a higher incidence of 12.45% (95% CI = 4.99–22.56%). Grade 3–5 CV AEs occurred in 4.28% (95% CI = 3.37–5.28%) among all ICIs arms. Incidence of severe events was 3.72% (95% CI = 2.60–5.03%), 4.79% (95% CI = 2.91–7.07%), 4.62% (95% CI = 2.11%−7.97%) and 5.48% (95% CI = 2.73–9.07%) with the use of PD-1, PD-L1 and CTLA-4 inhibitors and with combinations, respectively. Incidence results are summarized in FIG. 2 and FIG. 3. For mortality analyses, only studies that provided an adequate report on mortality causes were included. Deaths from any CV cause occurred in 0.32% of the patients receiving ICIs (95% CI = 0.20–0.44%) (SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 4). Funnel plots for estimation of the intervention effect from each individual study were generated. For all grade CV AEs incidence, some heterogeneity was noted, while for grade 3–5 CV AEs and mortality analyses the plots resemble a symmetrical inverted funnel (SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 5).

Fig. 2.

– Incidence of all-grade cardiovascular AEs in studies testing ICIs according to the mechanism of action. Incidence rates are represented by boxes and whiskers indicate 95% CI; size of squares is proportional to amount of data of each trial. Numbers in brackets for selected studies identifies different studies from same author published on the same year.

Fig. 3.

– Incidence of grade 3–5 cardiovascular AEs in studies testing ICIs according to the mechanism of action. Incidence rates are represented by boxes and whiskers indicate 95% CI; size of squares is proportional to amount of data of each trial. Numbers in brackets for selected studies identifies different studies from same author published on the same year.

Relative risk of cardiovascular toxicities with checkpoint inhibitors

Risk of experiencing all grade CV AEs was numerically higher among patients that received ICIs compared to placebo or BSC, although not statistically significant (RR = 1.16; 95% CI = 0.98–1.37; P = 0.09) as exhibited in FIG. 4. When only grade 3–5 CV AEs where considered, ICIs were associated with increased risk (RR 1.36; 95% CI = 1.06–1.73; P = 0.01) as depicted in FIG. 5. The risk of death from any CV cause did not differ between ICIs and placebo or BSC arms (RR = 1.52; 95% CI = 0.58–3.97; P = 0.39) (SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 6).

Fig. 4.

– Forest plot of relative risk (RR) of all-grade cardiovascular AEs associated with ICIs versus placebo/BSC. RR are represented by boxes and whiskers indicate 95% CIs; size of squares is proportional to amount of data of each trial. Numbers in brackets for selected studies identifies different studies from same author published on the same year.

Fig. 5.

– Forest plot of relative risk (RR) of grade 3–5 cardiovascular AEs associated with ICIs versus placebo/BSC. RR are represented by boxes and whiskers indicate 95% CIs; size of squares is proportional to amount of data of each trial. Numbers in brackets for selected studies identifies different studies from same author published on the same year.

Additional analyses were conducted to estimate the RR individual CV AEs, including arrhythmia, cardiac arrest, heart failure, stroke, hypertension, myocardial infarction, myocarditis, pericardial events, and thromboembolic events. None of the analysis identified a statistically significant additional risk of these events compared placebo or BSC (SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURES 7–15). Although the number of patients in these sub-analyses was small, the risk of stroke (RR 1.70; 95% CI = 0.58–4.95; P = 0.33), myocarditis (RR 1.69; 95% CI = 0.35–8.18; P = 0.51) and myocardial infarction (RR 2.0; 95% CI = 0.87–4.59; P = 0.10) was numerically higher among patients exposed to ICIs. It reinforces the hypothesis of an increased risk of atherosclerotic and inflammatory events rather than non-inflammatory events like hypertension (RR 1.0; 95% CI = 0.74–1.36; P = 0.99) and thrombosis (RR 0.93; 95% CI = 0.53–1.63; P = 0.80).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis that succeeds in demonstrating the association between ICIs and CV risk. Among 21,118 patients from 57 RCTs, all grade CV events incidence was 8.32% (95% CI = 6.35–10.53%). PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors exhibited similar incidence rates which was slightly lower then with CTLA-4 inhibitors. Incidence rates reached up to 12.45% (95% CI = 4.99–22.56%) with combination regimens. Grade 3–5 CV AEs occurred in 4.28% (95% CI = 3.37–5.28%) among all ICIs arms. Incidence increased progressively from 3.72% (95% CI = 2.60–5.03%) with PD-1 inhibitors to 5.48% (95% CI = 2.73–9.07%) with combinations. Deaths from any CV cause occurred in 0.32% of the patients receiving ICIs (95% CI = 0.20%−0.44%). The risk of all grade CV AEs and grade 3–5 CV AEs was higher among patients that received ICIs compared to placebo or BSC (RR = 1.16; 95% CI = 0.98–1.37; P = 0.09 and RR 1.36; 95% CI = 1.06–1.73; P = 0.01) but this correlation was statistically significant only when where considered. Risk of death from any CV cause did not differ between ICIs and placebo or BSC arms (RR = 1.52; 95% CI = 0.58–3.97; P = 0.39).

The results presented herein can be added to other recent meta-analyses approaching an equivalent outcome [75,76]. Rahouma and colleagues investigated the association between ICIs use and CV AEs, including comparator arms that contained either inactive or active treatments. Among 6574 patients from 11 RCTs included, no difference was found regarding all grade cardiotoxicity (RR 1.15; 95% CI = 0.73–1.80; P = 0.55) or high-grade CV adverse events (RR 1.47; 95% CI = 0.87–2.46; P = 0.15). More recently, Agostinetto and colleagues performed a two-parts meta-analyses – the first part assessing ICIs versus non-ICIs active treatments and the second part investigating whether dual-agent ICIs induce higher toxicity than single-agent ICIs. Eighty studies including 35,337 patients were included in the analysis. No difference in CV events incidence was observed between ICIs and non-ICIs groups (RR 1.14; 95% CI = 0.88–1.48; P = 0.326) nor between dual ICIs versus single ICIs groups (RR 1.91; 95% CI = 0.52–7.01, P = 0.329). Myocarditis incidence did not differ between ICI and non-ICI groups (RR 1.11; 95% CI = 0.64–1.92; P = 0.701) nor between dual ICI and single ICI groups (RR 1.10; 95% CI = 0.31–3.87; P = 0.881). We understand that the abovementioned difference can be assigned to the methodology we adopted. Analyzing risks using a placebo or BSC comparator rather than other active treatment showcases the exact effect of ICIs in CV toxicity. As ICIs may also present synergistic CV toxicities with other anticancer therapies, there is a future need to evaluate CV AEs related to combined treatments.

There are several potential hypotheses for an increase in CV toxicities with ICIs. Preclinical studies utilizing murine models showed that PD-L1 is expressed in nonlymphoid tissues like the heart, and the relative levels of inhibitory PD-L1 may determine a threshold to immunotolerance, exhibiting a protective effect against autoimmune damage to the heart [77]. Pathology reports from patients affected with ICIs-related myocarditis confirm an imbalance between tolerance and autoimmunity, resulting in a T-cell mediated event [6]. Molecular examination of recurrent ICIs-associated myocarditis exhibited microRNAs with known inflammatory roles and its parallel with circulating cytokine abundance. Besides, serum autoantibodies linked to autoimmune disease were also identified [78]. The combination of CTLA-4 and PD-1 or PD-L1 inhibitors is known to increase both incidence and severity of immune related AEs when compared to single agent regimens [79]. For example, in the MYSTIC trial [19] treatment-related AEs of any grade occurred in 54.2% of patients who received durvalumab, a PD-L1 inhibitor, and in 60.1% patients who received combination of durvalumab with tremelimumab, a CTLA-4 inhibitor. When CV AEs were selected, this study outweighed others, with an incidence of 36.93% of all grade CV AEs. Therefore, inferences on the role of this single study on the overall CV AEs incidence rate can not be made. A recently published meta-analysis evaluated incidence rates of AEs secondary to combination regimens of one active treatment (chemotherapy, targeted therapy, immunotherapy, or radiation therapy) with PD-1 or PD-L1 inhibitors in 161 prospective trials. Among 17,197 patients included, 6083 received immunotherapy plus a PD-1 or PD-L1 inhibitor. Incidence of AEs following this combination was 86.8% (95% CI = 80.9 – 91.1; I2 = 94%) for all-grade AEs and 35.9% (95% CI = 29.5 – 42.9; I2 = 92%) for grade 3 or higher AEs. Treatment-related deaths occurred in 0.87% of patients in this group. For CTLA-4 inhibitors combination, deaths were caused by a spectrum of uncommon adverse events, consistent with our and our colleagues' findings [80].

One limitation of our study is that although the inclusion criteria comprised low bias-risk features (e.g., phase III, randomized and placebo-controlled), many studies were classified as high bias-risk after careful evaluation. In most of cases, the reason leading to the high-risk of bias classification was the lack of clarity of the outcome reports, mainly regarding death cases. Sensitivity analyses were performed excluding these papers, and the results supported our previous findings (SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURES 16–18). Other limitation is the inclusion of CV events that could be considered non-immunogenic like hypertension and thromboembolic events. As the in vivo mechanism of ICIs AEs is not fully elucidated, and the RR of this events is mainly the same compared to placebo, we don't believe that it underpowers our findings.

Due to the relatively short follow-up of studies with ICIs, we cannot conclude about late cardiac risk associated with these agents. Studies that exhibited follow-up duration above the median of 12.6 months exhibited more all-grade and high-grade CV AEs than those with follow-up duration below the median (n = 1260 versus 340 and 526 versus 206, respectively). Nevertheless, this is an exploratory hypothesis, and may be related to a more prolonged period of observation for assessment of toxicities.

Currently, guidelines do not recommend cardiac monitoring for cancer patients receiving ICIs [81,82]. We argue that clinical assessment of CV risk factors should be routinely recommended for these patients based on our results. It is highly important to adjust or minimize other potential CV risks during therapy with ICIs. For patients presenting risk factors for CV events, a multi-disciplinary approach including cardiology assessment might be recommended.

Conclusion

This systematic review and meta-analysis corroborate the pre-clinical hypothesis of an increased risk of CV AEs related to ICIs. The data presented also contributes to a better comprehension of the incidence of these events and risk's magnitude. Based on our results, there is satisfactory evidence suggesting awareness for patient's CV signs and symptoms while receiving ICIs in clinical practice.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This work was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Sírio-Libanês.

Consent for publication

Prior presentations: this study was presented as part of a Poster Session at the 2021 ASCO Annual Meeting and embargo is currently ended. DOI: 10.1200/JCO.2021.39.15_suppl.2636 Journal of Clinical Oncology 39, no. 15_suppl (May 20, 2021) 2636–2636.

Availability of data and material

Data regarding CV AEs that was not available in the printed version of the included studies was extracted from ClinicalTrials.gov (https://clinicaltrials.gov)

Funding

This work was supported by the Instituto de Ensino e Pesquisa of Hospital Sírio-Libanês.

The role of the funder: The funder had no role in the design of the study, the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, writing of this manuscript or the decision to submit it for publication.

Authors’ contributions

D.L.F.J. conceived and supervised the project. C.B.X and G.H. performed the systematic review. C.B.X contributed to data analysis. C.D.H.L. contributed to data analysis and artwork. E.D.B.P. and A.K. contributed to the discussion section and review of the manuscript.

Declaration of Competing Interest

Dr. Jardim receives speaker fees from Roche, Janssen, Astellas, MSD, Bristol-Myers Squibb and Libbs, as well as consultant fees from Janssen, Bristol-Myers Squibb and Libbs. Dr. Harada receives speaker fees from MSD, Pfizer and AstraZeneca. All other authors declare no competing interests

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge and thank Rachel Riera MD, MSc, PhD, coordinator of the Center of Health Technology Assessment of Hospital Sírio-Libanês and adjunct professor from Universidade Federal de São Paulo for the statistical consulting provided to our group.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.tranon.2022.101383.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Oliveira L.J.C., Gongora A.B.L., Jardim D.L.F. Spectrum and clinical activity of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors: regulatory approval and under development. Curr. Oncol. Rep. [Internet] 2020;22(7):70. doi: 10.1007/s11912-020-00928-5. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s11912-020-00928-5 [cited 2021 Jan 18]Available from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Postow M.A., Sidlow R., Hellmann M.D., Longo D.L. Immune-related adverse events associated with immune checkpoint blockade. N. Engl. J. Med. [Internet] 2018;378(2):158–168. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1703481. http://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMra1703481 editor. [cited 2021 Jan 18]Available from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nishino M., Giobbie-Hurder A., Hatabu H., Ramaiya N.H., Hodi F.S. Incidence of programmed cell death 1 inhibitor–related pneumonitis in patients with advanced cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol [Internet] 2016;2(12):1607. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.2453. http://oncology.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?doi=10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.2453 [cited 2021 Jan 18]Available from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang W., Men P., Xue H., Jiang M., Luo Q. Risk of gastrointestinal adverse events in cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitor plus chemotherapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Oncol. [Internet] 2020;10:197. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.00197. https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fonc.2020.00197/full [cited 2021 Jan 18]Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barroso-Sousa R., Barry W.T., Garrido-Castro A.C., Hodi F.S., Min L., Krop I.E., et al. Incidence of endocrine dysfunction following the use of different immune checkpoint inhibitor regimens: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. [Internet] 2018;4(2):173. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.3064. http://oncology.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?doi=10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.3064 [cited 2021 Jan 18]Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grabie N., Lichtman A.H., Padera R. T cell checkpoint regulators in the heart. Cardiovasc. Res. [Internet] 2019;115(5):869–877. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvz025. https://academic.oup.com/cardiovascres/article/115/5/869/5307034 [cited 2020 Sep 19]Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calabretta R., Hoeller C., Pichler V., Mitterhauser M., Karanikas G., Haug A., et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy induces inflammatory activity in large arteries. Circulation [Internet] 2020;120 doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.048708. https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.048708 [cited 2020 Sep 19];CIRCULATIONAHAAvailable from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Varricchi G., Galdiero M.R., Marone G., Criscuolo G., Triassi M., Bonaduce D., et al. Cardiotoxicity of immune checkpoint inhibitors. ESMO Open [Internet] 2017;2(4) doi: 10.1136/esmoopen-2017-000247. http://esmoopen.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/esmoopen-2017-000247 [cited 2020 Sep 19]Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) Public Dashboard [Internet]. Available from: https://fis.fda.gov/sense/app/d10be6bb-494e-4cd2-82e4-0135608ddc13/sheet/45beeb74-30ab-46be-8267-5756582633b4/state/analysis.

- 10.Ouzzani M., Hammady H., Fedorowicz Z., Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. [Internet] 2016;5(1):210. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4. http://systematicreviewsjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4 [cited 2021 Jan 18]Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.CTCAE v4.03 [Internet]. Available from: https://evs.nci.nih.gov/ftp1/CTCAE/CTCAE_4.03/CTCAE_4.03_2010-06-14_QuickReference_8.5x11.pdf.

- 12.Liberati A., Altman D.G., Tetzlaff J., Mulrow C., Gøtzsche P.C., Ioannidis J.P.A., et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. [Internet] 2009;6(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100. https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100 [cited 2020 Sep 19]Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nyaga V.N., Arbyn M., Aerts M. Metaprop: a Stata command to perform meta-analysis of binomial data. Arch. Public Health [Internet] 2014;72(1):39. doi: 10.1186/2049-3258-72-39. http://archpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/2049-3258-72-39 [cited 2021 Mar 15]Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The Cochrane Collaboration; 2020. Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer Program] Version 5.4. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higgins J.P.T., Altman D.G., Gotzsche P.C., Juni P., Moher D., Oxman A.D., et al. The cochrane collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ [Internet] 2011;343(oct18 2):d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. https://www.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bmj.d5928 [cited 2020 Dec 25]–d5928Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dreier M. In: Methods of Clinical Epidemiology [Internet] SAR Doi, Williams GM., editors. Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; Berlin: 2013. Quality Assessment in meta-analysis; pp. 213–228.http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-642-37131-8_13 [cited 2022 Feb 10]Springer Series on Epidemiology and Public Health). Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galsky M.D., Mortazavi A., Milowsky M.I., George S., Gupta S., Fleming M.T., et al. Randomized double-blind phase II study of maintenance pembrolizumab versus placebo after first-line chemotherapy in patients with metastatic urothelial cancer. JCO [Internet]. 2020;38(16):1797–1806. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.03091. https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.19.03091 [cited 2020 Sep 19]Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rizvi N.A., Cho B.C., Reinmuth N., Lee K.H., Luft A., Ahn M.-.J., et al. Durvalumab with or without tremelimumab vs standard chemotherapy in first-line treatment of metastatic non–small cell lung cancer: the MYSTIC phase 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. [Internet] 2020;6(5):661. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.0237. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamaoncology/fullarticle/2763864 [cited 2020 Sep 19]Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Finn R.S., Ryoo B.-.Y., Merle P., Kudo M., Bouattour M., Lim H.Y., et al. Pembrolizumab as second-line therapy in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma in KEYNOTE-240: a randomized, double-blind, phase iii trial. JCO [Internet]. 2020;38(3):193–202. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.01307. http://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.19.01307 [cited 2020 Sep 19]Available from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferris R.L., Haddad R., Even C., Tahara M., Dvorkin M., Ciuleanu T.E., et al. Durvalumab with or without tremelimumab in patients with recurrent or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: EAGLE, a randomized, open-label phase III study. Ann. Oncol. [Internet] 2020;31(7):942–950. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.04.001. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0923753420364346 [cited 2020 Sep 19]Available from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reardon D.A., Brandes A.A., Omuro A., Mulholland P., Lim M., Wick A., et al. Effect of nivolumab vs bevacizumab in patients with recurrent glioblastoma: the checkmate 143 phase 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. [Internet] 2020;6(7):1003. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.1024. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamaoncology/fullarticle/2766213 [cited 2020 Sep 19]Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ribas A., Kefford R., Marshall M.A., Punt C.J.A., Haanen J.B., Marmol M., et al. Phase III randomized clinical trial comparing tremelimumab with standard-of-care chemotherapy in patients with advanced melanoma. JCO [Internet]. 2013;31(5):616–622. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.6112. http://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.2012.44.6112 [cited 2020 Sep 19]Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Day S., Hodi F.S., McDermott D.F., Weber R.W., Sosman J.A., Haanen J.B., et al. A phase III, randomized, double-blind, multicenter study comparing monotherapy with ipilimumab or gp100 peptide vaccine and the combination in patients with previously treated, unresectable stage III or IV melanoma. JCO [Internet]. 2010;28(18_suppl):4. http://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/jco.2010.28.18_suppl.4 [cited 2020 Sep 19]–4Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burtness B., Harrington K.J., Greil R., Soulières D., Tahara M., de Castro G., et al. Pembrolizumab alone or with chemotherapy versus cetuximab with chemotherapy for recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (KEYNOTE-048): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. The Lancet [Internet] 2019;394(10212):1915–1928. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32591-7. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673619325917 [cited 2020 Sep 19]Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robert C., Schachter J., Long G.V., Arance A., Grob J.J., Mortier L., et al. Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. [Internet] 2015;372(26):2521–2532. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1503093. http://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMoa1503093 [cited 2020 Sep 19]Available from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bellmunt J., de Wit R., Vaughn D.J., Fradet Y., Lee J.-.L., Fong L., et al. Pembrolizumab as second-line therapy for advanced urothelial carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. [Internet] 2017;376(11):1015–1026. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1613683. http://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMoa1613683 [cited 2020 Sep 19]Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu Y.-.L., Lu S., Cheng Y., Zhou C., Wang J., Mok T., et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in a predominantly Chinese patient population with previously treated advanced NSCLC: checkMate 078 randomized phase III clinical trial. J. Thoracic Oncol. [Internet] 2019;14(5):867–875. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.01.006. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1556086419300206 [cited 2020 Sep 19]Available from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reck M., Rodríguez-Abreu D., Robinson A.G., Hui R., Csőszi T., Fülöp A., et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for PD-L1–positive non–small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. [Internet] 2016;375(19):1823–1833. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1606774. http://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMoa1606774 [cited 2020 Sep 19]Available from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moehler M.H., Cho J.Y., Kim Y.H., Kim J.W., Di Bartolomeo M., Ajani J.A., et al. A randomized, open-label, two-arm phase II trial comparing the efficacy of sequential ipilimumab (ipi) versus best supportive care (BSC) following first-line (1 L) chemotherapy in patients with unresectable, locally advanced/metastatic (A/M) gastric or gastro-esophageal junction (G/GEJ) cancer. JCO [Internet]. 2016;34(15_suppl):4011. http://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.2016.34.15_suppl.4011 [cited 2020 Sep 19]–4011Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Herbst R.S., Baas P., Kim D-W, Felip E., Pérez-Gracia J.L., Han J.-.Y., et al. Pembrolizumab versus docetaxel for previously treated, PD-L1-positive, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-010): a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet [Internet] 2016;387(10027):1540–1550. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01281-7. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673615012817 [cited 2020 Sep 19]Available from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shitara K., Özgüroğlu M., Bang Y.-.J., Di Bartolomeo M., Mandalà M., Ryu M.-.H., et al. Pembrolizumab versus paclitaxel for previously treated, advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (KEYNOTE-061): a randomised, open-label, controlled, phase 3 trial. The Lancet [Internet] 2018;392(10142):123–133. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31257-1. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673618312571 [cited 2020 Sep 19]Available from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rittmeyer A., Barlesi F., Waterkamp D., Park K., Ciardiello F., von Pawel J., et al. Atezolizumab versus docetaxel in patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (OAK): a phase 3, open-label, multicentre randomised controlled trial. The Lancet [Internet] 2017;389(10066):255–265. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32517-X. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S014067361632517X [cited 2020 Sep 19]Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eggermont A.M.M., Blank C.U., Mandala M., Long G.V., Atkinson V., Dalle S., et al. Adjuvant pembrolizumab versus placebo in resected stage III melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. [Internet] 2018;378(19):1789–1801. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1802357. http://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMoa1802357 [cited 2020 Sep 19]Available from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Planchard D., Reinmuth N., Orlov S., Fischer J.R., Sugawara S., Mandziuk S., et al. ARCTIC: durvalumab with or without tremelimumab as third-line or later treatment of metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann. Oncol. [Internet] 2020;31(5):609–618. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.02.006. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0923753420360415 [cited 2020 Sep 19]Available from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Long G.V., Dummer R., Hamid O., Gajewski T., Caglevic C., Dalle S., et al. Epacadostat (E) plus pembrolizumab (P) versus pembrolizumab alone in patients (pts) with unresectable or metastatic melanoma: results of the phase 3 ECHO-301/KEYNOTE-252 study. JCO [Internet]. 2018;36(15_suppl):108. http://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.2018.36.15_suppl.108 [cited 2020 Sep 19]–108Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Balar A.V., Plimack E.R., Grivas P., Necchi A., De Santis M., Pang L., et al. Phase 3, randomized, double-blind trial of pembrolizumab plus epacadostat or placebo for cisplatin-ineligible urothelial carcinoma (UC): KEYNOTE-672/ECHO-307. JCO [Internet] 2018;36(15_suppl):TPS4587. http://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.2018.36.15_suppl.TPS4587 [cited 2020 Sep 19]–TPS4587Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arance H.Gogas, Dreno B., Flaherty K.T., Demidov L., Stroyakovskiy D., et al. Combination treatment with cobimetinib (C) and atezolizumab (A) vs pembrolizumab (P) in previously untreated patients (pts) with BRAFV600 wild type (wt) advanced melanoma: primary analysis from the phase 3 IMspire170 trial. Ann. Oncol. [Internet] 2019;30(suppl_5):906. https://oncologypro.esmo.org/meeting-resources/esmo-2019-congress/Combination-treatment-with-cobimetinib-C-and-atezolizumab-A-vs-pembrolizumab-P-in-previously-untreated-patients-pts-with-BRAFV600-wild-type-wt-advanced-melanoma-primary-analysis-from-the-phase-3-IMspire170-trial Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Motzer R.J., Escudier B., McDermott D.F., George S., Hammers H.J., Srinivas S., et al. Nivolumab versus everolimus in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. [Internet] 2015;373(19):1803–1813. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1510665. http://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMoa1510665 [cited 2020 Sep 19]Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Robert C., Long G.V., Brady B., Dutriaux C., Maio M., Mortier L., et al. Nivolumab in previously untreated melanoma without BRAF mutation. N. Engl. J. Med. [Internet] 2015;372(4):320–330. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1412082. http://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMoa1412082 [cited 2020 Sep 19]Available from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hellmann M.D., Paz-Ares L., Bernabe Caro R., Zurawski B., Kim S.-.W., Carcereny Costa E., et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced non–small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. [Internet] 2019;381(21):2020–2031. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1910231. http://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMoa1910231 [cited 2020 Sep 19]Available from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Antonia S.J., Villegas A., Daniel D., Vicente D., Murakami S., Hui R., et al. Durvalumab after chemoradiotherapy in stage III non–small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. [Internet] 2017;377(20):1919–1929. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1709937. http://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMoa1709937 [cited 2020 Sep 19]Available from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tabernero J., Van Cutsem E., Bang Y.-.J., Fuchs C.S., Wyrwicz L., Lee K.W., et al. Pembrolizumab with or without chemotherapy versus chemotherapy for advanced gastric or gastroesophageal junction (G/GEJ) adenocarcinoma: the phase III KEYNOTE-062 study. JCO [Internet] 2019;37(18_suppl):LBA4007. http://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.2019.37.18_suppl.LBA4007 [cited 2020 Sep 19]–LBA4007Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Motzer R.J., Rini B.I., McDermott D.F., Arén Frontera O., Hammers H.J., Carducci M.A., et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus sunitinib in first-line treatment for advanced renal cell carcinoma: extended follow-up of efficacy and safety results from a randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. The Lancet Oncol. [Internet] 2019;20(10):1370–1385. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30413-9. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1470204519304139 [cited 2020 Sep 19]Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maio M., Scherpereel A., Calabrò L., Aerts J., Perez S.C., Bearz A., et al. Tremelimumab as second-line or third-line treatment in relapsed malignant mesothelioma (DETERMINE): a multicentre, international, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2b trial. The Lancet Oncol. [Internet] 2017;18(9):1261–1273. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30446-1. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1470204517304461 [cited 2020 Sep 19]Available from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cortés J., Lipatov O., Im S.-.A., Gonçalves A., Lee K.S., Schmid P., et al. KEYNOTE-119: phase III study of pembrolizumab (pembro) versus single-agent chemotherapy (chemo) for metastatic triple negative breast cancer (mTNBC) Ann. Oncol. [Internet] 2020;30:v859–v860. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0923753419603704 [citedSep 19]Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carbone D.P., Reck M., Paz-Ares L., Creelan B., Horn L., Steins M., et al. First-line nivolumab in stage IV or recurrent non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med [Internet] 2017;376(25):2415–2426. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1613493. http://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMoa1613493 [cited 2020 Sep 19]Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tarhini A.A., Lee S.J., Hodi F.S., Rao U.N.M., Cohen G.I., Hamid O., et al. A phase III randomized study of adjuvant ipilimumab (3 or 10 mg/kg) versus high-dose interferon alfa-2b for resected high-risk melanoma (U.S. Intergroup E1609): preliminary safety and efficacy of the ipilimumab arms. JCO [Internet] 2017;35(15_suppl):9500. http://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.2017.35.15_suppl.9500 [cited 2020 Sep 19]–9500Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wolchok J.D., Chiarion-Sileni V., Gonzalez R., Rutkowski P., Grob J.-.J., Cowey C.L., et al. Overall survival with combined nivolumab and ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. [Internet] 2017;377(14):1345–1356. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1709684. http://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMoa1709684 [cited 2020 Sep 19]Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Powles T., Loriot Y., Ravaud A., Vogelzang N.J., Duran I., Retz M., et al. Atezolizumab (atezo) vs. chemotherapy (chemo) in platinum-treated locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma (mUC): immune biomarkers, tumor mutational burden (TMB), and clinical outcomes from the phase III IMvigor211 study. JCO [Internet]. 2018;36(6_suppl):409. http://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.2018.36.6_suppl.409 [cited 2020 Sep 19]–409Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eng C., Kim T.W., Bendell J., Argilés G., Tebbutt N.C., Di Bartolomeo M., et al. Atezolizumab with or without cobimetinib versus regorafenib in previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer (IMblaze370): a multicentre, open-label, phase 3, randomised, controlled trial. The Lancet Oncol. [Internet] 2019;20(6):849–861. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30027-0. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1470204519300270 [cited 2020 Sep 19]Available from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pujade-Lauraine E., Fujiwara K., Dychter S.S., Devgan G., Monk B.J. Avelumab (anti-PD-L1) in platinum-resistant/refractory ovarian cancer: JAVELIN Ovarian 200 Phase III study design. Future Oncol. [Internet] 2018;14(21):2103–2113. doi: 10.2217/fon-2018-0070. https://www.futuremedicine.com/doi/10.2217/fon-2018-0070 [cited 2020 Sep 19];Available from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mok T.S.K., Wu Y.-.L., Kudaba I., Kowalski D.M., Cho B.C., Turna H.Z., et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for previously untreated, PD-L1-expressing, locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-042): a randomised, open-label, controlled, phase 3 trial. The Lancet [Internet] 2019;393(10183):1819–1830. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32409-7. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673618324097 [cited 2020 Sep 19]Available from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Beer T.M., Kwon E.D., Drake C.G., Fizazi K., Logothetis C., Gravis G., et al. Randomized, double-blind, phase III trial of ipilimumab versus placebo in asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic patients with metastatic chemotherapy-naive castration-resistant prostate cancer. JCO [Internet]. 2017;35(1):40–47. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.69.1584. http://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.2016.69.1584 [cited 2020 Sep 19]Available from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bazhenova L., Redman M.W., Gettinger S.N., Hirsch F.R., Mack P.C., Schwartz L.H., et al. A phase III randomized study of nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus nivolumab for previously treated patients with stage IV squamous cell lung cancer and no matching biomarker (Lung-MAP Sub-Study S1400I, NCT02785952) JCO [Internet] 2019;37(15_suppl):9014. http://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.2019.37.15_suppl.9014 [cited 2020 Sep 19]–9014Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 55.Owonikoko T.K., Kim H.R., Govindan R., Ready N., Reck M., Peters S., et al. Nivolumab (nivo) plus ipilimumab (ipi), nivo, or placebo (pbo) as maintenance therapy in patients (pts) with extensive disease small cell lung cancer (ED-SCLC) after first-line (1 L) platinum-based chemotherapy (chemo): results from the double-blind, randomized phase III CheckMate 451 study. Ann. Oncol. [Internet] 2019;30:ii77. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0923753419302595 [cited 2020 Sep 19]Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Powles T., Park S.H., Voog E., Caserta C., Valderrama B.P., Gurney H., et al. Maintenance avelumab + best supportive care (BSC) versus BSC alone after platinum-based first-line (1 L) chemotherapy in advanced urothelial carcinoma (UC): JAVELIN Bladder 100 phase III interim analysis. JCO [Internet] 2020;38(18_suppl):LBA1. https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.2020.38.18_suppl.LBA1 [cited 2020 Sep 19]–LBA1Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yau J.W.Park, Finn R.S., Cheng A.-.L., Mathurin P., Edeline J., et al. LBA38 PR CheckMate 459: a randomized, multi-center phase III study of nivolumab (NIVO) vs sorafenib (SOR) as first-line (1 L) treatment in patients (pts) with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (aHCC) Ann. Oncol. [Internet]. 2019;30(suppl_5):874. https://www.annalsofoncology.org/article/S0923-7534(19)60389-3/pdf Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Andre T., Shiu K.-.K., Kim T.W., Jensen B.V., Jensen L.H., Punt C.J.A., et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for microsatellite instability-high/mismatch repair deficient metastatic colorectal cancer: the phase 3 KEYNOTE-177 Study. JCO [Internet] 2020;38(18_suppl):LBA4. https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.2020.38.18_suppl.LBA4 [cited 2020 Sep 19]–LBA4Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bang Y.-.J., Wyrwicz L., Park Y.I., Ryu M.-.H., Muntean A., Gomez-Martin C., et al. Avelumab (MSB0010718C; anti-PD-L1) + best supportive care (BSC) vs BSC ± chemotherapy as third-line treatment for patients with unresectable, recurrent, or metastatic gastric cancer: the phase 3 JAVELIN Gastric 300 trial. JCO [Internet] 2016;34(15_suppl):TPS4135. http://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.2016.34.15_suppl.TPS4135 [cited 2020 Sep 19]–TPS4135Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Reck M., Vicente D., Ciuleanu T., Gettinger S., Peters S., Horn L., et al. Efficacy and safety of nivolumab (nivo) monotherapy versus chemotherapy (chemo) in recurrent small cell lung cancer (SCLC): results from CheckMate 331. Ann. Oncol. [Internet] 2018 Dec;29:x43. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0923753419327619 [cited 2020 Sep 19]Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shah M.A., Adenis A., Enzinger P.C., Kojima T., Muro K., Bennouna J., et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy as second-line therapy for advanced esophageal cancer: phase 3 KEYNOTE-181 study. JCO [Internet]. 2019;37(15_suppl):4010. http://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.2019.37.15_suppl.4010 [cited 2020 Sep 19]–4010Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ascierto P.A., Del Vecchio M., Robert C., Mackiewicz A., Chiarion-Sileni V., Arance A., et al. Ipilimumab 10 mg/kg versus ipilimumab 3 mg/kg in patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma: a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, phase 3 trial. The Lancet Oncol. [Internet] 2017;18(5):611–622. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30231-0. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1470204517302310 [cited 2020 Sep 19]Available from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ferris R.L., Licitra L., Fayette J., Even C., Blumenschein G., Harrington K.J., et al. Nivolumab in patients with recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: efficacy and safety in checkmate 141 by prior cetuximab use. Clin. Cancer Res. [Internet] 2019;25(17):5221–5230. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-3944. http://clincancerres.aacrjournals.org/lookup/doi/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-3944 [cited 2020 Sep 19]Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Barlesi F., Vansteenkiste J., Spigel D., Ishii H., Garassino M., de Marinis F., et al. Avelumab versus docetaxel in patients with platinum-treated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (JAVELIN Lung 200): an open-label, randomised, phase 3 study. The Lancet Oncol. [Internet] 2018;19(11):1468–1479. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30673-9. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1470204518306739 [cited 2020 Sep 19]Available from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cohen E.E.W., Soulières D., Le Tourneau C., Dinis J., Licitra L., Ahn M.-.J., et al. Pembrolizumab versus methotrexate, docetaxel, or cetuximab for recurrent or metastatic head-and-neck squamous cell carcinoma (KEYNOTE-040): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. The Lancet [Internet] 2019;393(10167):156–167. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31999-8. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673618319998 [cited 2020 Sep 19]Available from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Brahmer J., Reckamp K.L., Baas P., Crinò L., Eberhardt W.E.E., Poddubskaya E., et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced squamous-cell non–small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. [Internet] 2015;373(2):123–135. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504627. http://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMoa1504627 [cited 2020 Sep 19]Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Borghaei H., Paz-Ares L., Horn L., Spigel D.R., Steins M., Ready N.E., et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med [Internet] 2015;373(17):1627–1639. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507643. http://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMoa1507643 [cited 2020 Sep 19]Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Weber J.S., D'Angelo S.P., Minor D., Hodi F.S., Gutzmer R., Neyns B., et al. Nivolumab versus chemotherapy in patients with advanced melanoma who progressed after anti-CTLA-4 treatment (CheckMate 037): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. The Lancet Oncol. [Internet] 2015;16(4):375–384. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70076-8. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1470204515700768 [cited 2020 Sep 19]Available from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Eggermont A.M.M., Chiarion-Sileni V., Grob J.-.J., Dummer R., Wolchok J.D., Schmidt H., et al. Adjuvant ipilimumab versus placebo after complete resection of high-risk stage III melanoma (EORTC 18071): a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. The Lancet Oncol. [Internet] 2015;16(5):522–530. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70122-1. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1470204515701221 [cited 2020 Sep 19]Available from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kang Y.-.K., Boku N., Satoh T., Ryu M.-.H., Chao Y., Kato K., et al. Nivolumab in patients with advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer refractory to, or intolerant of, at least two previous chemotherapy regimens (ONO-4538-12, ATTRACTION-2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. The Lancet [Internet] 2017;390(10111):2461–2471. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31827-5. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673617318275 [cited 2020 Sep 19]Available from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lebbé C., Meyer N., Mortier L., Marquez-Rodas I., Robert C., Rutkowski P., et al. Evaluation of two dosing regimens for nivolumab in combination with ipilimumab in patients with advanced melanoma: results from the phase IIIb/IV CheckMate 511 trial. JCO [Internet]. 2019;37(11):867–875. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.01998. http://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.18.01998 [cited 2020 Sep 19]Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kato K., Cho B.C., Takahashi M., Okada M., Lin C.-.Y., Chin K., et al. Nivolumab versus chemotherapy in patients with advanced oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma refractory or intolerant to previous chemotherapy (ATTRACTION-3): a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. The Lancet Oncol. [Internet] 2019;20(11):1506–1517. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30626-6. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1470204519306266 [cited 2020 Sep 19]Available from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Galsky M.D., JÁA Arija, Bamias A., Davis I.D., De Santis M., Kikuchi E., et al. Atezolizumab with or without chemotherapy in metastatic urothelial cancer (IMvigor130): a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. The Lancet [Internet] 2020;395(10236):1547–1557. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30230-0. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673620302300 [cited 2020 Sep 19]Available from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rahouma M., Karim N.A., Baudo M., Yahia M., Kamel M., Eldessouki I., et al. Cardiotoxicity with immune system targeting drugs: a meta-analysis of anti-PD/PD-L1 immunotherapy randomized clinical trials. Immunotherapy [Internet] 2019;11(8):725–735. doi: 10.2217/imt-2018-0118. https://www.futuremedicine.com/doi/10.2217/imt-2018-0118 [cited 2020 Dec 25]Available from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Agostinetto E., Eiger D., Lambertini M., Ceppi M., Bruzzone M., Pondé N., et al. Cardiotoxicity of immune checkpoint inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials. Eur. J. Cancer [Internet] 2021;148:76–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2021.01.043. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0959804921000794 [cited 2021 Apr 12]Available from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Freeman G.J., Long A.J., Iwai Y., Bourque K., Chernova T., Nishimura H., et al. Engagement of the Pd-1 immunoinhibitory receptor by a Novel B7 family member leads to negative regulation of lymphocyte activation. J. Exper. Med. [Internet] 2000 Oct 2;192(7):1027–1034. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.7.1027. https://rupress.org/jem/article/192/7/1027/8251/Engagement-of-the-Pd1-Immunoinhibitory-Receptor-by [cited 2021 Apr 12]Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Aghel N., Gustafson D., Di Meo A., Music M., Prassas I., Seidman M.A., et al. Recurrent myocarditis induced by immune-checkpoint inhibitor treatment is accompanied by persistent inflammatory markers despite immunosuppressive treatment. JCO Precision Oncology [Internet] 2021;(5):485–491. doi: 10.1200/PO.20.00370. https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/PO.20.00370 [cited 2021 Apr 12]Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Martins F., Sofiya L., Sykiotis G.P., Lamine F., Maillard M., Fraga M., et al. Adverse effects of immune-checkpoint inhibitors: epidemiology, management and surveillance. Nat Rev. Clin. Oncol. [Internet] 2019;16(9):563–580. doi: 10.1038/s41571-019-0218-0. http://www.nature.com/articles/s41571-019-0218-0 [cited 2021 Apr 30]Available from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhou X., Yao Z., Bai H., Duan J., Wang Z., Wang X., et al. Treatment-related adverse events of PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitor-based combination therapies in clinical trials: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Oncol. [Internet] 2021 doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00333-8. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1470204521003338 [cited 2021 Aug 17];S1470204521003338. Available from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Brahmer J.R., Lacchetti C., Schneider B.J., Atkins M.B., Brassil K.J., Caterino J.M., et al. Management of immune-related adverse events in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: American society of clinical oncology clinical practice guideline. JCO [Internet]. 2018;36(17):1714–1768. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.77.6385. https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.2017.77.6385 [cited 2021 Apr 12]Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Haanen J.B.A.G., Carbonnel F., Robert C., Kerr K.M., Peters S., Larkin J., et al. Management of toxicities from immunotherapy: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol [Internet] 2017;28:iv119. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx225. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0923753419421534 [cited 2021 Apr 12]–42Available from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data regarding CV AEs that was not available in the printed version of the included studies was extracted from ClinicalTrials.gov (https://clinicaltrials.gov)