Abstract

Objective:

Suicidal thoughts and behaviors (STBs) represent a significant and escalating public health concern in youth. Evidence that suicidal thoughts and behaviors can emerge in the preschool years suggests that some pathways leading to clinically significant STBs begin early in life.

Method:

The current prospective longitudinal study examined the developmental trajectories of STBs in children from ages 3 to 17, oversampled for preschool-onset depression.

Results:

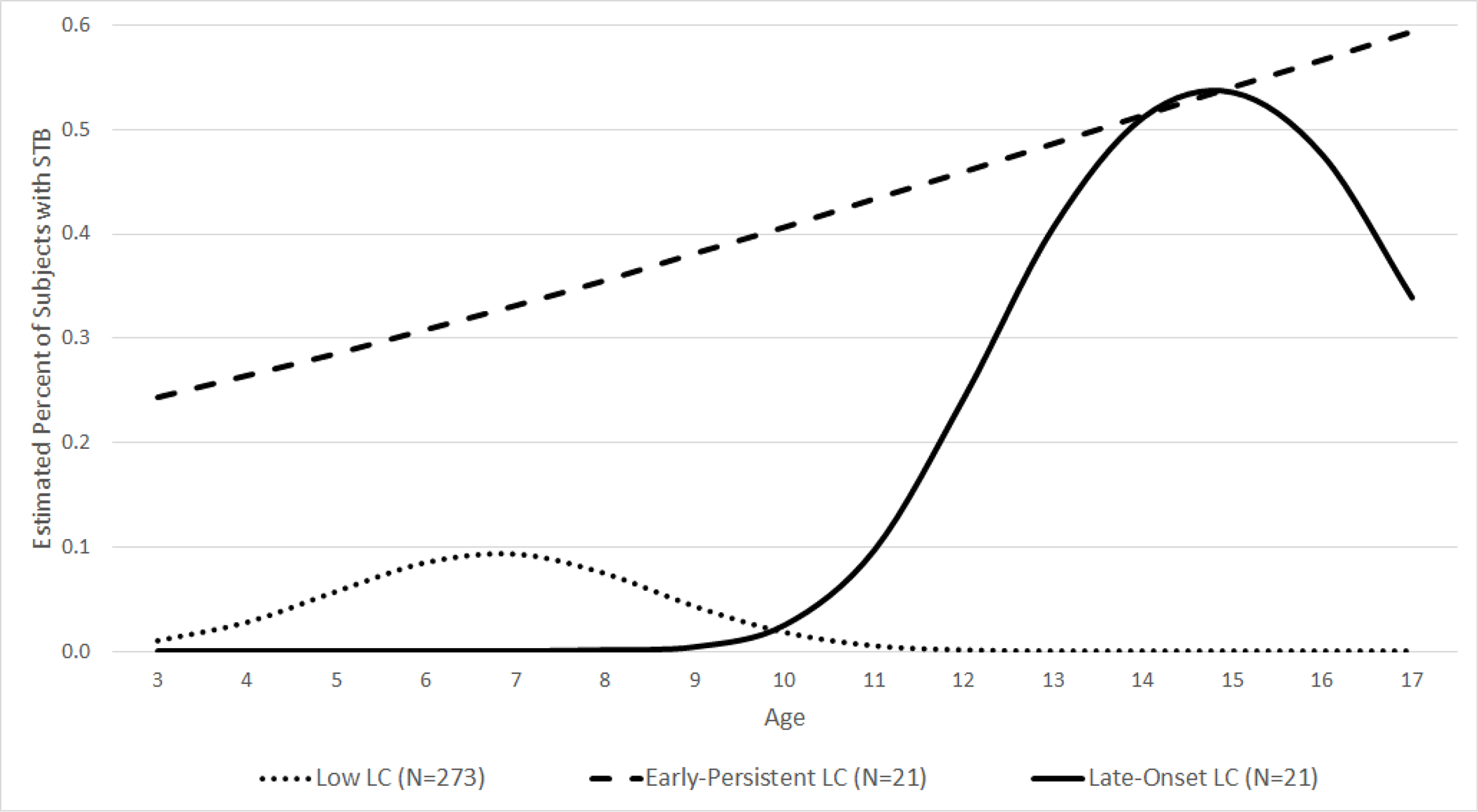

Three unique trajectories of STBs across childhood and adolescence were identified: a Low class (n = 273) characterized by low rates of STBs, an Early-Persistent class (n = 21) characterized by steadily increasing STBs, and a Late-Onset class (n = 21) characterized by low rates of STBs through age 10 followed by a dramatic increase from ages 11–14 years. Preschool measures of depression symptoms, externalizing symptoms, impulsivity, and lower income-to-needs were associated with both high-risk STB classes. Both high-risk STB classes reported greater functional impairment, more externalizing symptoms, and more cumulative stressful life events in adolescence relative to the Low class; the Late-Onset class also reported poorer academic functioning relative to both the Early-Persistent and Low classes.

Conclusions:

A significant minority of this prospectively followed group of preschool children evidenced STBs by and/or after age 10. Although relatively rare prior to age 10, approximately half of the children who experienced STBs in adolescence first exhibited STBs in early childhood and comprised a trajectory suggesting increasing STBs. In contrast, approximately half first exhibited STBs in early adolescence. Early screening and identification of at-risk youth during both preschool and late childhood is important for early intervention regarding STBs.

Introduction

Between 2006 and 2016, rates of suicide increased by 30% in youth ages 10–19 years, and youth presenting to hospitals with suicidal thoughts or attempts nearly doubled between 2008 to 20151. Suicide is now the third leading cause of death in children under 14 years2. A recent meta-analysis found few accurate predictors of suicidal thoughts and behaviors (STBs)3 highlighting the need for greater knowledge about developmental trajectories of STBs. Increased understanding of predictors of risk trajectories has the potential to uncover how suicide risk unfolds over time.

STBs, defined as suicidal ideation, plans, or attempts, typically increase over the course of development in at-risk groups. It is often assumed that young children are too developmentally immature to engage in STBs, however, longstanding evidence refutes these assumptions4. For example, children as young as 3 years report persistent thoughts about death, suicide behaviors, and even attempts5. Suicidal depression has also been documented in preschool-age children (3–7 years) and is characterized by increased anhedonia, worthlessness, guilt, non-suicidal self-injurious behavior, and recurrent thoughts about death6. Importantly, recent work found that depressed 4- to 6-year-olds with STBs have a better understanding of death – including the notion that death is permanent – than depressed children without STBs and healthy peers7. Thus, some of the pathways that lead to STBs begin early in life, suggesting studies of STBs may benefit from starting earlier in development to identify antecedents.

Whereas preschool-onset STBs are rare and understudied, more is known about the onset and trajectories of STBs during late childhood and adolescence. A US population-based study of 9 and 10 year-olds found rates of suicidal ideation, self-harm, and suicide attempts were 6.4%, 9.1%, and 1.3% respectively8. Moreover, suicidal ideation tends to increase from 11- to 17 years9 with some evidence of a peak in incidence at 15–16 years in girls and a steady increase over those years in boys10. Prospective studies indicate that suicidal ideation and self-harm predict later suicide attempts, and suicide attempts predict suicide in adolescents11. There is also a sharp increase in suicide in early adolescence and young adulthood12.

Alongside onset and prevalence rates, trajectories of STBs throughout adolescence have been identified. For example, in one study that followed African American youth from 11–19 years, suicidal ideation peaked around 12–13 years13. Another longitudinal study of adolescents from 14–17 years identified three STB trajectories: increasing, decreasing, and not present14. Finally, a nationally representative study that followed individuals over 20 years (ages 11–32) also found three STB trajectories: low and slightly decreasing, low and slightly increasing, and high and slightly decreasing15. These trajectory studies began and assessed STBs during adolescence. However, no longitudinal studies began and assessed STBs during preschool and continued through adolescence. Given the evidence for increasing rates of STBs throughout childhood and adolescence and research documenting the emergence of STBs in early childhood, additional work assessing longitudinal trajectories of STBs is needed.

Established risk factors for STBs include family history of suicide and/or suicide attempts, early environmental factors, and psychological factors related to psychopathology and social relationships16. Much of the literature on youth risk factors assesses independent factors and has been primarily cross-sectional, which limits the ability to make any type of causal inferences. Less work has focused on identifying classes or subgroups of children with suicidality by incorporating multiple risk factors that may differentiate onset, severity, and/or course17. Below, we briefly review evidence supporting established risk factors of STBs in youth.

Family history of suicide and/or suicide attempts is considered a biological and psychological risk for STBs18,19. Moreover, the heritability of suicide risk is independent of risk for psychiatric disorders broadly20. However, family history of suicide attempts or suicide does not appear to be associated with early childhood STBs5,21, suggesting developmental differences in family history as a risk-factor.

Environmental factors associated with STBs in youth include low socioeconomic status (SES)22, experiencing stressful life events, and childhood maltreatment23. There is a substantial literature linking STBs with exposure to stress and early adversity24 and longitudinal prospective studies have demonstrated that physical and sexual abuse in childhood is linked with later suicide attempts and death in youth22,23.

Psychological factors associated with STBs in youth include internalizing and externalizing psychopathology and poor social functioning. Depression, in particular, has been consistently associated with STBs16. Guilt, a prominent feature of depression, is also independently associated with suicide25. Externalizing problems and impulsivity have been linked with STBs in youth16,24,26 and may have particular relevance for STBs in younger children. Specifically, one study found that, compared to adolescents, 5- to 11-year-olds who died by suicide were more likely to have externalizing symptoms and less likely to have depression/dysthymia27. The impact of poor social functioning on STBs, especially social rejection and bullying, has also received attention. Several longitudinal studies have demonstrated that childhood social problems are related to later STBs28–31 with recent work suggesting that increased use of social media use may play a role in STB risk32,33.

Given the increasing public health crisis regarding STBs in childhood and new data on early onset1,5, understanding how suicide risk unfolds across development and how specific factors predict risk trajectories has the potential to identify earlier windows for prevention and intervention. The current prospective longitudinal study examined trajectories of STBs from preschool to adolescence in children oversampled for depression during the preschool period. Based on previous work examining STB trajectories in adolescents13–15 it was broadly hypothesized that there would be three unique trajectory groups: increasing, decreasing, and stable low STBs. Based on the previously detailed evidence, several family, environmental, and psychological factors were hypothesized to predict STBs over time: family history of suicide and/or suicide attempts, lower SES, experiencing more stressful life events, poor peer relations, psychopathology including high levels of depression, high impulsivity, and externalizing symptoms. Finally, it was hypothesized that children with increasing STBs would evidence greater functional and academic impairment in adolescence relative to children with decreasing or stable low STBs.

Method

Participants

Participants were 348 children and their primary caregivers enrolled in the Preschool Depression Study, an ongoing study of children and their families designed to investigate the longitudinal outcomes of early-onset depression at the Washington University School of Medicine34,35. Children 3.0 to 5.9 years were recruited between 2003 and 2005 from pediatrician’s offices, daycare centers, and preschools in the St. Louis metropolitan area. Children were screened with the Preschool Feelings Checklist36 and oversampled for depression and externalizing symptoms. Exclusion criteria were chronic medical illnesses, neurological disorders, pervasive developmental disorders, or language and/or cognitive delays (see34 for additional details). All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board prior to data collection.

306 children were enrolled at preschool age (between ages 3.0 to 5.9 years). Approximately 65% (n=197) of children had a psychiatric diagnosis during Times 1–3. Of those, 25% (n=75) had depression and 32% (n=99) had an externalizing disorder. Eight additional follow-up assessments occurred approximately one year apart, with longer intervals between Times 3 and 4 (approximately 2.5 years) and Times 8 and 9 (approximately 3 years), due to grant funding cycles (see Figure S1, available online). Beginning at Time 6 (ages 8 to 13.6 years), 42 new healthy children, age-matched to children with psychiatric disorders, were recruited and followed to increase the number of children without psychopathology.37 The number of children with an assessment at each age is detailed in Supplement 1, available online. Of these 348 participants, 315 completed at least 3 assessments (M=6.1, SD=1.9, Range=3–9 assessments) and were included in quadratic growth mixture models (described below).

Measures

STB Trajectories

Suicidal thoughts and behaviors.

STBs were assessed via The Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment (PAPA)38, Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment (CAPA)39, or Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (K-SADS40) at each timepoint, including baseline and up to eight follow-up assessments, using the age-appropriate diagnostic interview. When participants were 3.0–7.9 years the PAPA was administered to parents. When participants were 8.0–8.9 years the CAPA was administered to parents only, and when participants were 9.0 years and older the CAPA was administered separately to parents and children. When participants were 16 years or older, the K-SADS was administered separately to parents and adolescents. Parent and child report on the CAPA and K-SADS were combined by taking the most severe rating. Raters were trained to reliability and blind to the child’s previous diagnostic status34,35. All interviews were audiotaped, and methods to maintain reliability and prevent drift, including ongoing calibration of interviews by master raters for 20% of each interviewer’s cases, were implemented in consultation with an experienced clinician at each timepoint.

A dichotomous STB variable was calculated at each timepoint as the endorsement of any of the following symptoms: suicidal themes in play (PAPA), suicidal thoughts, suicide plan (PAPA, CAPA), suicidal behavior, or suicide attempt (PAPA, CAPA, K-SADS; see Table S1 for additional details, available online).

Preschool Predictors of STB Trajectories

Depression.

Depression severity was calculated by summing the number of MDD symptoms endorsed on the PAPA at baseline, excluding STBs. These included: depressed/irritable mood, anhedonia, insomnia/hypersomnia, fatigue, decreased concentration, weight/appetite change, psychomotor agitation/retardation, and worthlessness/guilt.

Externalizing symptoms.

Externalizing symptoms were assessed with the MacArthur Health and Behavior Questionnaire-Parent (HBQ-P41) at baseline. The HBQ-P includes four Externalizing subscales: Oppositional Defiant (9 items), Conduct Problems (12 items), Overt Hostility (4 items), and Relational Aggression (6 items). Items are rated from 0 (never/not true) to 2 (often or very true).

Impulsivity.

Impulsivity was assessed with the 9-item Impulsivity subscale of the HBQ-P41 at baseline. Items are rated from 0 (never/not true) to 2 (often or very true).

Guilt.

Guilt feelings and reparation was assessed with the My Child: Version 242 at baseline. The My Child scale is a 100-item parent-report measure of children’s self-conscious emotions. Items are rated from 1 (extremely untrue) to 7 (extremely true) and subscale means are computed.

Early stressful life events.

The PAPA assessed how often children experienced any of 18 stressful life events (e.g., change in daycare/school, birth of sibling)38. Frequency of these events experienced prior to age 7 was summed to create a measure of early stressful life events.

Peer relations.

Peer relations were assessed with the Peer Relations subscale of the HBQ-P41) at baseline, a composite of the Peer Acceptance/Rejection (8 items) and Bullied by Peers (3 items) subscales. The composite assesses friendship quality, the extent to which the child is liked by peers, and how frequently the child is teased or picked on. Items are rated from 1 (not at all like) to 4 (very much like).

Social withdrawal.

Social Withdrawal was assessed using the mean of the Asocial with Peers (6 items) and Social Inhibition (3 items) subscales of the HBQ-P41 at baseline. Items are rated from 0 (never or not true) to 2 (often or very true).

Family history of suicide and/or suicide attempts.

The Family Interview for Genetic Studies (FIGS)43, a structured measure designed to assess diagnostic information about relatives, was used to assess family history of suicide and/or suicide attempts in first- and second-degree relatives at each timepoint. A senior psychiatrist, blind to the child’s diagnostic status, reviewed questions about the diagnostic status of family members. Family history of suicide and/or suicide attempts was coded dichotomously (present or absent).

Income-to-needs.

An income-to-needs ratio was computed as the total family income at baseline divided by the Federal Poverty Level, based on family size, at the time of data collection44.

Preschool to Middle Childhood Predictors of STB Trajectories

Depression, externalizing symptoms, impulsivity, guilt, early stressful life events, peer relations, social withdrawal, family history of suicide/attempts, and income-to-needs (all detailed above) were assessed at each timepoint between 3–10 years and used as early to middle childhood predictors of STB trajectories. Because participants had several assessments prior to age 10, individual participants’ estimated intercepts and slopes were extracted from multilevel models of each subscale (see results for further details).

Adolescent Outcomes of STB Trajectories

Adolescent outcomes were taken from the final assessment timepoint for each participant 14 years or older. Participants who completed their final assessment prior to age 14 were not included in the analyses of adolescent outcomes.

Adolescent externalizing symptoms.

Scores on the HBQ-P externalizing subscales at the final assessment assessed adolescent externalizing symptoms.

Adolescent internalizing symptoms.

Scores on the HBQ-P internalizing subscales at the final assessment assessed adolescent internalizing symptoms.

Cumulative stressful life events.

The frequency of stressful life events reported on the PAPA/CAPA/K-SADS were summed to create a cumulative stressful life events score indicating the frequency of stressful life events experienced through the final assessment.

Functional impairment.

The Functional Impairment scale (7 items) of the HBQ-P41 administered at the final assessment was used to quantify the amount of impairment exhibited across several domains of functioning, including school, home/family, and social. Items are rated from 0 (none) to 2 (a lot).

Academic functioning.

The Academic Functioning scale of the HBQ-P41 is a composite of the School Engagement (8 items) and Academic Competence (8 items) subscales. Items are rated from 1 (not at all) to 4 (quite a bit).

Data Analytic Plan

Growth Mixture Models.

Growth Mixture Models (GMM) were used to identify groups with similar courses of STBs. Age at assessment was the time variable and ranged from 3–19 years, however the model could not run including data from ages 18 and 19, because no participants with an assessment at age 18 (n=4) or 19 (n=1) endorsed STBs at that age, and thus effectively covered ages 3–17 years. We selected an optimal number of class trajectories by following an iterative sequence45. Consistent with best practices46,47 for class selection, as part of this sequence, model fit was evaluated through comparisons of the Lo-Mendell-Rubin adjusted likelihood ratio test p value, Bayesian information criterion (BIC), entropy, and group size. Model fit of a “k class” model (eg, a 4-class model) was compared with the model fit of a “k -1 class” model (eg, a 3-class model). This process concluded and the optimal number of classes was determined when the likelihood ratio tests were no longer significant, when overextraction was evident, or when a class model failed to converge46,48.

The 3-class model was selected because it had the lowest sample size adjusted BIC and because the Lo-Mendell-Rubin adjusted likelihood ratio was no longer significant for the 4-class model. See Table S2, available online, for all selection criteria.

Growth mixture model analyses were fit using Mplus 8.6. Given the longitudinal nature of the data, some cases were missing owing to attrition and thus a full-information maximum-likelihood estimator was used because these models assume the data are missing at random and produce estimates based on all available data. Even subjects with no missing assessments had missing data, because the time variable was age, not wave, and there were more possible ages than waves.

Preschool and Middle Childhood Predictors of STB Latent Classes.

Baseline depression, externalizing symptoms, impulsivity, guilt, early stressful life events, peer relations, social withdrawal, family history of suicide/attempts, and income-to-needs were each tested as potential predictors of membership in each latent class. Multinomial logistic regression models with latent class as the dependent variable were used to assess differences in preschool and middle childhood variables by class. When omnibus tests were significant, odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CI’s) comparing each pair of latent classes were calculated.

Adolescent Outcomes of STB Latent Classes.

Adolescent externalizing symptoms, internalizing symptoms, cumulative stressful life events, functional impairment, and academic functioning were included as outcome measures of latent class membership. Linear regressions with outcome as the dependent variable and latent class as the independent variable were conducted. Contrast statements were added to the model for pair-wise class comparisons when omnibus tests were significant.

Covariates included child sex (all analyses), age at baseline (preschool predictors), and age at last assessment (adolescent outcomes). To account for multiple comparisons, false discovery rate (FDR) p-values were calculated within each set of analyses (demographics, preschool-age predictors, adolescent outcomes, and post-hoc analyses). The FDR uses a rank-order approach to control for the proportion of false discoveries across multiple analyses.

Results

STB Trajectories

As described above, the 3-class model was selected as the best-fitting model. Intercept, slope, and quadratic estimates from this model are presented in Table 1. As can be seen in Figure 1, each of the three trajectories shows a distinct pattern over time (see Table S3, available online, for rates of STB endorsement by age). The largest class (N=273) is characterized by low rates of STBs at all points between 3 and 17 years (termed Low). The Low class reported overall low levels of STBs, although given that children were originally oversampled for depressive symptoms, as might be expected, some children in this class did transiently exhibit STBs at ages 3 through 9 years. The second class (N=21) is characterized by a steady, linear increase in the proportion of STBs endorsed over the study period (termed Early-Persistent). The third class (N=21) shows a unique trajectory characterized by a very low proportion of STBs early in development (ages 3–9 years), followed by a sharp increase after age 10, which peaks around age 15 and then begins to decrease (termed Late-Onset). Classes did not differ in IQ (χ2=3.70, p=.16), proportion of males and females (χ2=3.37, p=.19), or race (χ2=1.28, p=.86), as detailed in Table 2. Thus, overall forty-two of 315 (~13%) of children exhibited STBs in later childhood and adolescence, with about half having persistent and increasing STBs (Early-Persistent) and the other half developing STBs later in childhood and adolescence (Late-Onset). The Low and Early-Persistent classes align with the study predictions for expected trajectories. Contrary to predictions, there was no evidence for a decreasing class. The emergence of the Late-Onset class was unexpected and further explored in post-hoc analyses.

Table 1.

Intercept, Slope, and Quadratic Estimates from the 3 Latent Class Growth Mixture Model of Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors by Age

| Estimate | SE | Estimate/SE | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low LC (N=273) | ||||

| Intercept | −2.079 | 0.923 | −2.252 | 0.024 |

| Slope | 1.265 | 0.472 | 2.678 | 0.007 |

| Quadratic | −0.168 | 0.056 | −3.002 | 0.003 |

| Early-Persistent LC (N=21) | ||||

| Intercept | 1.435 | 0.362 | 3.965 | <0.001 |

| Slope | 0.108 | 0.054 | 2.007 | 0.045 |

| Quadratic | non-significant, removed from model | |||

| Late-Onset LC (N=21) | ||||

| Intercept | −20.395 | 4.694 | −4.345 | <0.001 |

| Slope | 3.922 | 0.898 | 4.369 | <0.001 |

| Quadratic | −0.166 | 0.043 | −3.913 | <0.001 |

Figure 1.

Estimated Latent Class Trajectories from the 3 Latent Class Growth Mixture Model of Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors by Age

Table 2.

Demographic and Descriptive Characteristics

| Total (N=315) | Low (N=273) | Early-Persistent (N=21) | Late-Onset (N=21) | Omnibus Test | Low vs. Late-Onset | Early-Persistent vs. Late-Onset | Low vs. Early-Persistent | |||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||

| Demographics | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | χ2 | p | FDR p | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Baseline age | 5.12 | 2.03 | 5.21 | 2.15 | 4.85 | 0.68 | 4.34 | 0.85 | 3.70 | 0.1575 | 0.2230 | |||

| Last assessment age | 13.76 | 3.11 | 13.53 | 3.13 | 14.28 | 2.79 | 16.30 | 1.61 | 13.10 | 0.0014 | 0.0084 | 0.64 (0.49–0.82) | 0.69 (0.52–0.92) | 0.92 (0.79–1.07) |

| Baseline income-to-needs | 2.09 | 1.13 | 2.16 | 1.12 | 1.82 | 1.07 | 1.46 | 1.12 | 8.13 | 0.0171 | 0.0513 | 1.73 (1.15–2.60) | 1.33 (0.77–2.29) | 1.30 (0.87–1.94) |

| IQ score | 105.0 | 14.6 | 105.8 | 14.5 | 101.9 | 14.3 | 100.1 | 15.6 | 3.70 | 0.1574 | 0.2230 | |||

| % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | χ2 | p | FDR p | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

|

|

||||||||||||||

| Male sex | 51.8 | 163 | 50.6 | 138 | 71.4 | 15 | 47.6 | 10 | 3.37 | 0.1858 | 0.2230 | |||

| Race | 1.28 | 0.8642 | 0.8642 | |||||||||||

| White | 53.3 | 168 | 54.2 | 148 | 47.6 | 10 | 47.6 | 10 | ||||||

| Black | 34.3 | 108 | 34.1 | 93 | 33.3 | 7 | 38.1 | 8 | ||||||

| Other | 12.4 | 39 | 11.7 | 32 | 19.1 | 4 | 14.3 | 3 | ||||||

Preschool Age Predictors of STB Trajectories

Differences in preschool-age predictors across STB trajectories are presented in Table 3. Relative to the Low class, both the Early-Persistent and Late-Onset classes reported more preschool externalizing and depression symptoms and impulsivity (ps<.05); a similar pattern for peer relations did not survive FDR correction. Moreover, relative to the Low class, the Late-Onset class reported lower income-to-needs (p<.01). Classes did not differ on family history of suicide/attempts, early stressful life events, social withdrawal, or guilt. These findings are broadly in line with study hypotheses, as when differences emerged between the classes, they were driven by increases in risk factors for both of the increasing STB classes (externalizing, depression, impulsivity), or the Late-Onset class (income-to-needs), relative to the Low class.

Table 3.

Preschool Predictors (baseline measures) of Latent Class Membership Covarying for Sex and Age at Baseline

| Low (N=237) | Early-Persistent (N=21) | Late-Onset (N=21) | Omnibus Test | Low vs. Late-Onset | Early- Persistent vs. Late-Onsest | Low vs. Early-Persistent | ||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | χ2 | p | FDR p | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Income-to-needs | 2.19 | 1.17 | 1.82 | 1.07 | 1.46 | 1.12 | 8.27 | 0.0160 | 0.0400 | 1.70 (1.15–2.52) | 1.29 (0.76–2.20) | 1.31 (0.89–1.95) |

| Depression | 1.89 | 1.57 | 3.38 | 1.53 | 2.81 | 1.50 | 16.66 | 0.0002 | 0.00010 | 0.70 (0.54–0.92) | 1.14 (0.81–1.62) | 0.62 (0.47–0.81) |

| Early stressful life events | 4.80 | 5.02 | 5.10 | 3.67 | 5.29 | 2.92 | 0.25 | 0.8809 | 0.9510 | |||

| Externalizing symptoms | 0.43 | 0.31 | 0.82 | 0.34 | 0.56 | 0.35 | 18.46 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.24 (0.06–0.95) | 3.47 (0.62–19.50) | 0.07 (0.02–0.25) |

| Impulsivity | 0.81 | 0.41 | 1.20 | 0.44 | 0.99 | 0.43 | 13.62 | 0.0011 | 0.0037 | 0.31 (0.10–0.93) | 1.99 (0.45–8.72) | 0.15 (0.05–0.47) |

| Peer relationships | 3.52 | 0.51 | 3.19 | 0.68 | 3.32 | 0.71 | 6.91 | 0.0316 | 0.0632 | |||

| Social withdrawal | 0.67 | 0.39 | 0.65 | 0.37 | 0.65 | 0.39 | 0.10 | 0.9510 | 0.9510 | |||

| Guilt reparation | 26.71 | 4.29 | 25.24 | 4.96 | 25.44 | 4.47 | 2.96 | 0.2282 | 0.3803 | |||

| Guilt feelings | 17.82 | 2.63 | 18.30 | 2.66 | 17.94 | 3.03 | 1.21 | 0.5465 | 0.7807 | |||

| % | N | % | N | % | N | χ2 | p | FDR p | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

|

|

||||||||||||

| Family history of suicide | 20.2 | 46 | 14.3 | 3 | 15.0 | 3 | 0.88 | 0.6448 | 0.8060 | |||

Adolescent Outcomes of STB Trajectories

Outcomes during adolescence were examined as a function of STB latent class (Table 4). Relative to the Low class, both the Late-Onset and Early-Persistent classes reported greater functional impairment, more externalizing symptoms, and more cumulative stressful life events. The Late-Onset class also reported poorer academic functioning relative to both the Low and Early-Persistent classes and more internalizing symptoms relative to the Low class. Moreover, STB latent class continued to predict stressful life events, functional impairment, academic functioning, and externalizing when each of the preschool predictors are included in the model (except preschool externalizing in the model of adolescent externalizing), suggesting that latent class explains unique variance in functional impairment not accounted for by other predictors.

Table 4.

Adolescent Outcomes Covarying for Sex and Age at Last Assessment

| Low (N=133) | Early-Persistent (N=13) | Late-Onset (N=20) | Omnibus Test | Low vs. Late-Onset | Early- Persistent vs. Late-Onset | Low vs. Early-Persistent | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | F | p | FDR p | F | p | F | p | F | p | |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Cumulative stressful life events | 39.3 | 34.3 | 65.5 | 80.3 | 98.0 | 82.7 | 14.06 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 25.97 | <0.0001 | 3.20 | 0.0753 | 3.99 | 0.0474 |

| Functional impairment | 0.22 | 0.32 | 0.45 | 0.52 | 0.62 | 0.48 | 12.04 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 21.28 | <0.0001 | 1.80 | 0.1818 | 4.62 | 0.0330 |

| Academic functioning | 4.02 | 0.63 | 3.87 | 0.63 | 3.40 | 0.92 | 7.16 | 0.0011 | 0.0014 | 14.27 | 0.0002 | 4.12 | 0.0440 | 0.38 | 0.5371 |

| Adolescent externalizing symptoms | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.34 | 0.30 | 0.26 | 0.31 | 5.38 | 0.0055 | 0.0055 | 3.96 | 0.0483 | 0.90 | 0.3430 | 7.85 | 0.0057 |

| Adolescent internalizing symptoms | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.33 | 0.20 | 0.51 | 0.42 | 12.15 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 23.17 | <0.0001 | 3.83 | 0.0522 | 2.44 | 0.1204 |

Post-Hoc Analyses Exploring Preschool-to-Middle Childhood Predictors of the Late-Onset Trajectory

Factors that may explain the rapid increase in STBs after age 10 for the Late-Onset class were examined in post-hoc analyses (Table S4, available online). Repeatedly assessed measures from ages 3 through 9.11 years included: depression, externalizing symptoms, impulsivity, guilt, peer relations, and social withdrawal. Multilevel linear models, including random intercept and slope components, generated individual participants’ estimated intercepts and slopes for each of the above potential risk factors. Changes (e.g., slopes) from ages 3 through 9.11 years were estimated for depression, externalizing, impulsivity, guilt, peer relations, and social withdrawal. Cumulative stressful life events, family history of suicide/attempts, and income-to-needs just at age 10 were also examined as potential risk factors. Differences in pubertal status at age 10 were also analyzed, given the increased risk for STBs that emerges after puberty49.

Relative to the Early-Persistent class, the Low class had a shallower negative slope in externalizing symptoms (p<.001). Furthermore, the omnibus test revealed significant effects of income-to-needs and social withdrawal slopes that suggested that children in the Late-Onset class experienced lower income-to-needs and did not have an age-appropriate decline in social withdrawal in early to middle childhood relative to the Early-Persistent and Low classes; however, these effects did not survive FDR corrections. The classes did not differ in changes in depression, impulsivity, peer relationships, guilt, family history of suicide, cumulative stressful life events through age 9, or puberty status at age 10.

Discussion

This study identified three unique developmental trajectories of STBs that emerge during preschool and extend through adolescence (ages 3–17 years): Low, Early-Persistent, and Late-Onset. Of the 42 children in the high-risk groups (~13% of the sample), approximately half exhibited persistent and increasing STBs starting as early as preschool (Early-Persistent), and half first exhibited STBs in early adolescence (Late-Onset). The Low and Early-Persistent classes were consistent with study hypotheses and extend our knowledge of STB trajectories earlier into development, highlighting their emergence as early as the preschool period. The finding of a third Late-Onset class was not hypothesized but of interest. This class reported low rates of STBs through age 10 followed by a dramatic increase in STBs after age 10.

Several preschool-age risk factors distinguished the low from high-risk STB classes including depression, externalizing symptoms, impulsivity, and lower income-to-needs. There was also some indication that children in the high-risk STB classes might struggle with peer relationships, although these did not survive FDR correction. These findings are largely in line with previous studies of correlates and risk factors for STBs in school age and adolescent youth16 providing further evidence for their association with STBs and extending evidence for their relevance to preschool age children. However, no preschool-age risk factors uniquely predicted the Early-Persistent from the Late-Onset class. Contrary to hypotheses, family history of suicide and/or suicide attempts, early stressful life events, social withdrawal, and guilt did not differ by class. As most research on these risk factors for STBs has focused on adolescents, a downward extension of these specific factors may not be applicable. For example, some risk factors may not have been experienced or may not have accumulated to a significant degree to have an effect during the preschool period.

In our prior work, we found evidence of continuation in STBs from preschool to school-age5. The current study extends these findings by: (1) creating latent classes that span from preschool to adolescence and (2) showing that children in the high-risk STB classes had worse adolescent outcomes than those in the Low class, including greater functional impairment, more externalizing symptoms, and more experiences of stressful life events (Early-Persistent and Late-Onset), and more internalizing symptoms and poorer academic functioning (Late-Onset only). These findings suggest that trajectories of increasing STBs have widespread implications for mental health and functioning across several domains.

During adolescence those in the Late-Onset class had poorer academic functioning relative to those in the Early-Persistent class, and this was the only variable that distinguished the two high-risk STB classes. This finding is not surprising given the precipitous change in STBs in the Late-Onset class prior to this measure and consistency with other poor outcomes; yet may also suggest that during adolescence, those in the Early-Persistent class who have continual and increasing STBs have acquired some ability to cope in the context of academic functioning.

Post-hoc analyses explored predictors of the unexpected Late-Onset class, pointing to externalizing symptoms, social withdrawal, and income-to-needs as factors that should be investigated in future studies. Relative to the Early-Persistent class, the Low class had a shallower negative slope in externalizing symptoms. This is likely a result of the Early-Persistent class regressing toward more developmentally normative levels of externalizing behavior, whereas the Low class started off with low levels and maintained those low levels across the study. Alternatively, 49 children in the Low class expressed STBs between ages 3–10. Thus, the STBs in this class may be an extreme form of frustration expression associated with persistent externalizing symptoms. Future research exploring this possibility is needed.

Interestingly, while all three classes showed age-appropriate decreases in social withdrawal from ages 3 through 9, the Late-Onset class decreased at a slower rate. Consistent with previous literature23, the Late-Onset class also reported lower income-to-needs at age 10 compared to the Low class. However, these effects did not survive FDR correction. Nonetheless, when combined with the preschool-onset risk factors described above, these exploratory findings hint that the Late-Onset group might be facing more social deprivation and failing to increase engagement with peers. There were no group differences in peer relations broadly, suggesting that the effect is unique to social withdrawal. A potential picture emerges of the Late-Onset class as a group of children without early STBs and who experienced low SES throughout early childhood. Over time, children in this class may not increase engagement in social situations or develop relationships that might buffer the negative impact of accumulating stressful life events50. Moreover, the social effects of low SES might become highly salient around age 10 as peer pressure and peer comparison increase, driving social withdrawal and STBs as maladaptive coping mechanisms. The effects of accumulating stressful life events may also represent an independent risk for STBs24 and contribute to social withdrawal.

The findings from the current study are limited in several ways. First, because the children were oversampled for depression, the findings may not generalize to other populations. Second, the findings may be limited by the use of a composite score that combined suicidal thoughts and behaviors. There is some evidence that predictors of ideation may differ from those that predict the transition from ideation to plans and attempts9. These issues require additional study in samples with higher rates of suicidal behaviors. While several of the predictors of the Late-Onset class are intriguing and fit with prior literature, the differences did not survive FDR correction and should be taken as hypotheses to be examined in future work.

Clinically, it may be helpful for parents, teachers, and pediatricians to pay additional attention to children at ages 10 and 11 for signs of emerging STBs. Children who experience higher levels of stressful life events, lower income, and who fail to engage with other children may be at particular risk for a rapid increase in STBs at this time. Monitoring social engagement both in person and on social media may provide important information about a child’s internal emotional states. Second, similar to what has been observed in school age and adolescence, preschool children displaying symptoms of depression, externalizing disorders and impulsivity, and from families with lower income relative to needs may be at risk for increasing rates of STBs across childhood and into adolescence. Because these factors can be reliably assessed by preschool age, the potential for early intervention is significant. Intervening on such symptoms during preschool has the potential to not only treat existing difficulties but alter a child’s overall trajectory away from developing or maintaining STBs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

The authors wish to thank the children and caregivers of the Preschool Depression Study for their time and commitment to this ongoing project.

Funding:

Support for this research was provided by National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) grant R01 5R01MH090786 (PIs: Luby and Barch). Dr. Whalen’s effort was supported by grants NIMH grants: K23 MH118426 (PI: Whalen) and L30 MH108015 (PI: Whalen). Dr Hennefield’s effort was supported by National Institute of Child Health and Development (NICHD) training grant F32 HD093273 (PI: Hennefield).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Plemmons G, Hall M, Doupnik S, et al. Hospitalization for Suicide Ideation or Attempt: 2008–2015. Pediatrics. 2018;141(6). doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-2426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dervic K, Brent DA, Oquendo MA. Completed Suicide in Childhood. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2008;31(2):271–291. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2008.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Franklin JC, Ribeiro JD, Fox KR, et al. Risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors: A meta-analysis of 50 years of research. Psychol Bull. 2017;143(2):187–232. doi: 10.1037/bul0000084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pfeffer CR, Conte HR, Plutchik R, Jerrett I. Suicidal Behavior in Latency-Age Children: An Empirical Study. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 1979;18(4):679–692. doi: 10.1016/S0002-7138(09)62215-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whalen DJ, Dixon-Gordon K, Belden AC, Barch D, Luby JL. Correlates and Consequences of Suicidal Cognitions and Behaviors in Children Ages 3 to 7 Years. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;54(11):926–937.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2015.08.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luby J, Whalen D, Tillman R, Barch D. Clinical and Psychosocial Characteristics of Young Children with Suicidal Ideation, Behaviors and Non-Suicidal Self-Injurious Behaviors. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2018;0(0). doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2018.06.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hennefield L, Whalen DJ, Wood G, Chavarria MC, Luby JL. Changing Conceptions of Death as a Function of Depression Status, Suicidal Ideation, and Media Exposure in Early Childhood. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019;58(3):339–349. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2018.07.909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeVille DC, Whalen D, Breslin FJ, et al. Prevalence and Family-Related Factors Associated With Suicidal Ideation, Suicide Attempts, and Self-injury in Children Aged 9 to 10 Years. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(2):e1920956–e1920956. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nock MK, Green JG, Hwang I, et al. Prevalence, correlates, and treatment of lifetime suicidal behavior among adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(3):300–310. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamapsychiatry.55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boeninger DK, Masyn KE, Feldman BJ, Conger RD. Sex differences in developmental trends of suicide ideation, plans, and attempts among European American adolescents. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2010;40(5):451–464. doi: 10.1521/suli.2010.40.5.451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brent DA, Perper JA, Moritz G, et al. Psychiatric risk factors for adolescent suicide: a case-control study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1993;32(3):521–529. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199305000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, et al. Cross-national prevalence and risk factors for suicidal ideation, plans and attempts. Br J Psychiatry J Ment Sci. 2008;192(2):98–105. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.040113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Musci RJ, Hart SR, Ballard ED, et al. Trajectories of suicidal ideation from sixth through tenth grades in predicting suicide attempts in young adulthood in an urban African American cohort. Suicide Life-Threatening Behav. 2016;46(3):255–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rueter MA, Holm KE, McGeorge CR, Conger RD. Adolescent suicidal ideation subgroups and their association with suicidal plans and attempts in young adulthood. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2008;38(5):564–575. doi: 10.1521/suli.2008.38.5.564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nkansah-Amankra S Adolescent suicidal trajectories through young adulthood: prospective assessment of religiosity and psychosocial factors among a population-based sample in the United States. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2013;43(4):439–459. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cha CB, Franz PJ, M Guzmán E, Glenn CR, Kleiman EM, Nock MK. Annual Research Review: Suicide among youth - epidemiology, (potential) etiology, and treatment. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2018;59(4):460–482. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whalen DJ, Luby JL, Barch DM. Highlighting risk of suicide from a developmental perspective. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2018;25(1):No Pagination Specified-No Pagination Specified. doi: 10.1111/cpsp.12229 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rajalin M, Hirvikoski T, Jokinen J. Family history of suicide and exposure to interpersonal violence in childhood predict suicide in male suicide attempters. J Affect Disord. 2013;148(1):92–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.11.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tidemalm D, Runeson B, Waern M, et al. Familial clustering of suicide risk: a total population study of 11.4 million individuals. Psychol Med. 2011;41(12):2527–2534. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711000833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qin P, Agerbo E, Mortensen PB. Suicide risk in relation to socioeconomic, demographic, psychiatric, and familial factors: a national register-based study of all suicides in Denmark, 1981–1997. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(4):765–772. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.4.765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luby JL, Gilbert K, Whalen D, Tillman R, Barch DM. The Differential Contribution of the Components of Parent−Child Interaction Therapy Emotion Development for Treatment of Preschool Depression. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. Published online July 31, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2019.07.937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson JG, Cohen P, Gould MS, Kasen S, Brown J, Brook JS. Childhood adversities, interpersonal difficulties, and risk for suicide attempts during late adolescence and early adulthood. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(8):741–749. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.8.741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Björkenstam C, Kosidou K, Björkenstam E. Childhood adversity and risk of suicide: cohort study of 548 721 adolescents and young adults in Sweden. BMJ. 2017;357:j1334. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j1334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beautrais A Suicide in New Zealand II: a review of risk factors and prevention. N Z Med J. 2003;116(1175):U461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bryan CJ, Morrow CE, Etienne N, Ray-Sannerud B. Guilt, shame, and suicidal ideation in a military outpatient clinical sample. Depress Anxiety. 2013;30(1):55–60. doi: 10.1002/da.22002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yen S, Gagnon K, Spirito A. Borderline Personality Disorder in Suicidal Adolescents. Personal Ment Health. 2013;7(2):89–101. doi: 10.1002/pmh.1216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sheftall AH, Asti L, Horowitz LM, et al. Suicide in Elementary School-Aged Children and Early Adolescents. Pediatrics. 2016;138(4). doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Geoffroy M-C, Boivin M, Arseneault L, et al. Associations Between Peer Victimization and Suicidal Ideation and Suicide Attempt During Adolescence: Results From a Prospective Population-Based Birth Cohort. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016;55(2):99–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2015.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klomek AB, Sourander A, Niemelä S, et al. Childhood bullying behaviors as a risk for suicide attempts and completed suicides: a population-based birth cohort study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(3):254–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klomek AB, Sourander A, Elonheimo H. Bullying by peers in childhood and effects on psychopathology, suicidality, and criminality in adulthood. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(10):930–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Winsper C, Lereya T, Zanarini M, Wolke D. Involvement in Bullying and Suicide-Related Behavior at 11 Years: A Prospective Birth Cohort Study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(3):271–282.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luxton DD, June JD, Fairall JM. Social Media and Suicide: A Public Health Perspective. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(Suppl 2):S195–S200. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Twenge JM, Joiner TE, Rogers ML, Martin GN. Increases in Depressive Symptoms, Suicide-Related Outcomes, and Suicide Rates Among U.S. Adolescents After 2010 and Links to Increased New Media Screen Time. Clin Psychol Sci. 2018;6(1):3–17. doi: 10.1177/2167702617723376 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luby JL, Belden AC, Pautsch J, Si X, Spitznagel E. The clinical significance of preschool depression: Impairment in functioning and clinical markers of the disorder. J Affect Disord. 2009;112(1–3):111–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.03.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luby JL, Si X, Belden AC, Tandon M, Spitznagel E. Preschool depression: Homotypic continuity and course over 24 months. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(8):897–905. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luby JL, Heffelfinger A, Koenig-McNaught AL, Brown K, Spitznagel E. The Preschool Feelings Checklist: A Brief and Sensitive Screening Measure for Depression in Young Children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43(6):708–717. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000121066.29744.08 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suzuki H, Luby JL, Botteron KN, Dietrich R, McAvoy MP, Barch DM. Early life stress and trauma and enhanced limbic activation to emotionally valenced faces in depressed and healthy children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53(7):800–813.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.04.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Egger HL, Ascher B, Angold A. The Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment: Version 1.4. Center for Developmental Epidemiology, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences. Duke Univ Med Cent Durh NC. Published online 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Angold A, Prendergast M, Cox A, Harrington R, Simonoff E, Rutter M. The Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment (CAPA). Psychol Med. 1995;25(04):739–753. doi: 10.1017/S003329170003498X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, et al. Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children-present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36(7):980–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Armstrong J, Goldstein L. Manual for the MacArthur health and behavior questionnaire (HBQ 1.0). MacArthur Found Res Netw Psychopathol Dev Univ Pittsburgh. Published online 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kochanska G, DeVet K, Goldman M, Murray K, Putnam SP. Maternal Reports of Conscience Development and Temperament in Young Children. Child Dev. 1994;65(3):852–868. doi: 10.2307/1131423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maxwell ME. Family Interview for Genetic Studies (FIGS): a manual for FIGS. Clin Neurogenet Branch Intramural Res Program Natl Inst Ment Health; Bethesda MD. Published online 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 44.McLoyd VC. Socioeconomic disadvantage and child development. Am Psychol. 1998;53(2):185–204. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.53.2.185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ram N, Grimm K. Using simple and complex growth models to articulate developmental change: Matching theory to method. Int J Behav Dev. 2007;31(4):303–316. doi: 10.1177/0165025407077751 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ram N, Grimm KJ. Growth Mixture Modeling: A Method for Identifying Differences in Longitudinal Change Among Unobserved Groups. Int J Behav Dev. 2009;33(6):565–576. doi: 10.1177/0165025409343765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, Muthén BO. Deciding on the Number of Classes in Latent Class Analysis and Growth Mixture Modeling: A Monte Carlo Simulation Study. Struct Equ Model Multidiscip J. 2007;14(4):535–569. doi: 10.1080/10705510701575396 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jung T, Wickrama K a. S. An Introduction to Latent Class Growth Analysis and Growth Mixture Modeling. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2008;2(1):302–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2007.00054.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bridge JA, Goldstein TR, Brent DA. Adolescent suicide and suicidal behavior. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47(3–4):372–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Criss MM, Pettit GS, Bates JE, Dodge KA, Lapp AL. Family adversity, positive peer relationships, and children’s externalizing behavior: A longitudinal perspective on risk and resilience. Child Dev. 2002;73(4):1220–1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.