Abstract

Aims:

To end the hepatitis and AIDS epidemics in the world by 2030, countries are encouraged to scale-up harm reduction services and target people who inject drugs (PWID). Blood-borne viruses (BBV) among PWID spread via unsterile injection equipment sharing and to combat this, many countries have introduced needle and syringe exchange programmes (NEP), though not without controversy. Sweden’s long, complicated harm reduction policy transition has been deviant compared to the Nordic countries. After launch in 1986, no NEP were started in Sweden for 23 years, the reasons for which are analysed in this study.

Methods:

Policy documents, grey literature and research mainly published in 2000–2017 were collected and analysed using a hierarchical framework, to understand how continuous build-up of evidence, decisions and key events, over time influenced NEP development.

Results:

Sweden’s first NEP opened in a repressive-control drug policy era with a drug-free society goal. Despite high prevalence of BBV among PWID with recurring outbreaks, growing research and key-actor support including a NEP law, no NEP were launched. Political disagreements, fluctuating actor-coalitions, questioning of research, and a municipality veto against NEP, played critical roles. With an individual-centred perspective being brought into the drug policy domain, the manifestation of a dual drug and health policy track, a revised NEP law in 2017 and removal of the veto, Sweden would see fast expansion of new NEP.

Conclusions:

Lessons from the Swedish case could provide valuable insight for countries about to scale-up harm reduction services including how to circumvent costly time- and resource-intensive obstacles and processes involving ideological and individual moral dimensions.

Keywords: dual track policy, harm reduction, HIV, needle exchange programme, people who inject drugs, hepatitis C

Background and aims

The World Health Organization (WHO) and the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) have set ambitious goals to end the hepatitis B, C (HBV, HCV) and AIDS epidemics in the world by 2030, targeting people who inject drugs (PWID) as a specific risk group (UNAIDS, 2014; WHO, 2016a). PWID using illegal drugs are partly hidden in society due to laws and societal and legal discrimination, and are considered a hard-to-reach group (Karlsson et al., 2017). PWID are also heavily affected by blood-borne viruses (BBV) such as HBV, HCV and HIV, which primarily spread via sharing of non-sterile injection equipment (Kåberg et al., 2020). To reach PWID and prevent BBV transmission, many countries have introduced harm reduction services such as evidence-based needle exchange programs (NEP) (Marotta & McCullagh, 2016), though not without political or societal controversy (Davidson & Howe, 2014; Roe, 2005). The goal of NEP is to reduce harm and BBV transmission, while accepting continued injection drug use (IDU) in some contexts perceived as creating unclear boundaries with, e.g., social services support, the police, politics, policy decision-making and local communities supposed to harbour these programmes (Davidson & Howe, 2014). Estimations suggest IDU is present in 179 of 206 countries with 93 countries providing forms of NEP (EMCDDA, 2019; Larney et al., 2017; Stone & Shirley-Beavan, 2018). Historically, NEP have been prohibited from starting, or forced to close because of societal or political turmoil (Davidson & Howe, 2014; Gyarmathy et al., 2016; Macneil & Pauly, 2010; Rich & Adashi, 2015). The WHO, UNAIDS but also the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) with support from several other organisations have underlined the importance of learning from key experiences to enable a more coherent global public health response including implementation of strategic policy frameworks and continued scaling-up of harm reduction services (Day et al., 2018; UNAIDS, 2015; UNODC et al., 2017; WHO, 2016b). Closure of NEP has often come against the backdrop of long and complicated starting processes involving policy-makers and actor-coalitions transitioning from a prohibitionist-oriented policy towards a harm reduction policy, as was the case for many European countries in 1980–1990 (Kübler, 2001). Additionally, NEP face challenges not only with reaching PWID but also in retaining them in the programmes over time (Gindi et al., 2009; Kåberg et al., 2018).

To reach the 2030 goals set by the WHO and UNAIDS could, for many countries, require scaling-up existing, but possibly also new evidence-based harm reduction services, within a larger comprehensive public health approach (Day et al., 2018). Research shows that service models suit PWID differently (Bruggmann & Litwin, 2013; Day et al., 2019) which is why some countries have opted to introduce evidence-based harm reduction services such as drug consumption rooms and heroin assisted treatment programmes, proven successful in reaching and retaining otherwise hard-to-reach PWID (EMCDDA, 2012, 2018). However, those few countries mostly found in Europe have implemented these programmes during often lengthy and intense discussions in both politics and society (Cruz et al., 2007). Even Switzerland, considered a harm reduction pioneer, had its transition challenges (Kimber et al., 2005; Kübler, 2001; Uchtenhagen, 2010). Sweden’s long and complicated harm reduction policy transition has been deviant compared to other European countries who have adopted harm reduction policies more quickly.

Harm reduction programmes have been extensively discussed, and also studied in Sweden during recent decades (Svensson, 2012; see what follows for additional references). However, in this article we develop an argument that understanding processes and events behind the Swedish deviant case with its specific NEP harm reduction approach, could provide lessons learnt to other countries and help understand how the interplay between scientific evidence, leadership, governance and policy decision-making helped change attitudes and understanding of NEP in a context strictly opposed to harm reduction. In what follows, we present an analysis of the Swedish NEP development over time and within the framework of the Swedish drug and health policy. We specifically wanted to understand reasons for NEP becoming accepted within a policy climate where political and moral issues collided with scientific evidence, how a series of events, decisions and continuous build-up of evidence, gradually created space for change in actor-coalitions dynamics, policy focus, and reorientation of political will and decision-making.

The formative era of Swedish drug policy and early harm reduction service implementation

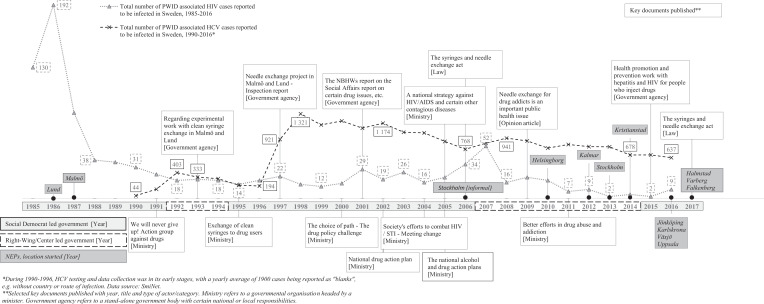

In the 1960s, as individual drug use was on the increase in the world, in Sweden it transformed into a social-legal challenge with stricter laws and Sweden launching one of the world’s first methadone maintenance treatment programmes for opioid users (Nyberg & Grönbladh, 2006; Statens Offentliga Utredningar [Swedish Government Official Reports]. (SOU 2000:126), 2000). When the Social Democrat political party lost power to a centre/right-wing government in 1976, political discussions and consequently drug policy shifted towards a repression-control and zero-tolerance model, reinforced in 1984 when the Social Democrats, back in power, introduced a national goal of a drug-free society (Government Bill [GB]. (Prop. 1984/85:19), 1984; Lenke & Olsson, 2002; Statens Offentliga Utredningar [Swedish Government Official Reports]. (SOU 2000:126), 2000; Tryggvesson, 2012). However, a contemporary emerging HIV epidemic among PWID led Sweden to open its first two NEP in Lund (1986) and Malmö (1987), both in the Skåne region in southern Sweden (Departementsskrivelse [Ministerial Report], 2010). By early 1990, seven of Sweden’s 21 regions were running various NEP activities, often initiated without a formal political decision (Socialstyrelsen [The National Board of Health and Welfare], 1993). Figure 1 summarises findings in terms of events taking place over the studied time period.

Figure 1.

Timeline with key events, reports, political majority, total number of NEP and PWID associated HIV/HCV cases reported in Sweden, 1985-2017.

Influential non-governmental organisations (NGO) and the social services on municipality level, an important actor given their responsibility for providing drug treatment, social or financial support to drug users and with their staff attributing to a coercive ideology (Bergmark, 1998), were predominantly negative towards NEP (Departementsskrivelse [Ministerial Report]. (Skr. 1988/89:94), 1989; Lenke & Olsson, 2002; Tryggvesson, 2012). Against the swift yet unorganised NEP development, the government agency responsible for developing and implementing national health policies, the National Board of Health and Welfare, conducted a NEP evaluation in 1988. The evaluation concluded that a formal affiliation with the healthcare system was lacking, including poor collaboration with the social services, which resulted in all NEP shutting down except for those in Lund and Malmö, continuing as trial NEP pending further evaluation (Departementsskrivelse [Ministerial Report]. (Skr. 1988/89:94), 1989). To start additional trial NEP, the social services in each municipality had to give their formal consent (Departementsskrivelse [Ministerial Report]. (Skr. 1988/89:94), 1989). In 1991, a right-wing/centre government won the election (Figure 1). Stricter drug use measures were implemented (Lenke & Olsson, 2002) and a new government agency, the National Institute of Public Health was formed, tasked with implementing the new harsher drug policy called the “Successful Swedish Control Model” (Lenke & Olsson, 2002) and with implementing the goal of creating a drug-free society (Government Bill [GB]. (Prop. 1984/85:19), 1984). The overarching ambition was highlighted in a government report stating that “the more difficult it was to be a drug user, the more appealing a drug-free life would appear” (Aktionsgrupp mot narkotika [Action Group Against Drugs], 1991, p. 14). This focus was in line with the more fierce and general public debate in the 1970s and 1980s focusing on strengthening the repressive control drug policy (Olsson et al., 2011). A debate which in the 1990s would focus on preserving the restrictive approach against what was perceived as a growing force of drug liberalisation ideas (Olsson et al., 2011).

Somewhat contradictorily, in the same period, the two remaining NEP were evaluated positively by the National Board of Health and Welfare and found not to contradict a drug-free society goal, despite poor interaction with the social services. They thus recommended that these trial NEP would become a permanent service in the healthcare system (Socialstyrelsen [The National Board of Health and Welfare], 1993). The Social Democrats regained power in mid-1990 and it was again concluded that the NEP were to continue as trials pending further evaluations (Departementsskrivelse [Ministerial Report]. (Skr. 1995/96:1), 1995; Socialstyrelsen [The National Board of Health and Welfare], 1997).

From a Nordic perspective, Sweden, like Denmark (1986) and Norway (1988), was early to launch NEP compared to Finland (1996) (Amundsen et al., 2003). However, the other Nordic countries, despite sharing commonalities with Sweden regarding a repression-control policy, had a more accepted and sustainable approach (Houborg & Bjerge, 2011; Koman, 2019; Tammi, 2005), while NEP in Sweden were launched in a strenuous societal but also an ambivalent political climate. This uniform ambivalence has been referred to as “tango-politics” i.e., making it hard to distinguish which political side that was leading “the dance” (Amundsen et al., 2003; EMCDDA, 2019; Lenke & Olsson, 2002), or even “politics in denial” (Tham, 2005), with a strict drug policy, reluctance towards harm reduction and key-actor opposition (Eriksson & Edman, 2017; Government Bill [GB]. (Prop. 2005/06:60), 2005; Tham et al., 2003; Tryggvesson, 2012). It would take another 26 years of political controversy until Sweden’s third NEP would start, after which a rapid scale-up of NEP would come to take place.

Responding to calls from the WHO, UNAIDS and UNODC to scale-up existing evidence-based harm reduction services, could for many countries involve introduction of new programmes which would require political and societal determination and public acceptance to avoid lengthy start-up processes, to allow for swiftness in provider implementation, in sharp contrast to how the NEP issue has developed in Sweden since the mid-1980s.

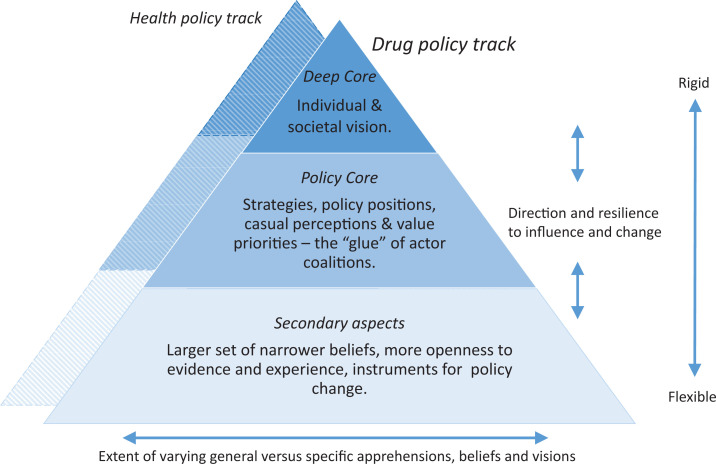

Methods and data

In this study we analysed how the concept of NEP resisted or was subjected to change in the context of the Swedish drug and health policy. To reconstruct this multi-phase and relatively long-lasting policy process, we drew upon the basic idea of the advocacy coalition framework (ACF) (Sabatier, 1988, 1998) and its use in similar contexts (Kübler, 2001), in what is referred to as competition between advocacy coalitions, their belief systems and the three included structural levels; i.e., the deep core holding the fundamental vision of the individual and society, the policy core containing strategies and policy positions that associate with the deep core, and secondary aspects containing the instruments on how to implement the policy core (Sabatier, 1998). Advocacy coalitions are networks of people who share beliefs about the causes and solutions of a policy problem, and engage in coordinating actions on different levels towards a common goal. The ACF offers an analytical approach for recognising these coalitions, and then analysing the related policy processes within changing environments, originating from actor-coalition competitions in specific policy subsystems (Willemsen, 2018). In addition to paying attention to actors and their coalitions, the ACF has a focus on policy processes which take place over “a decade or more” – on developments, evidence-building and other policy prerequisites that demand time: e.g., launching and conducting new research, changes in administration, legislation or state budgeting (Cairney, 2011). All of these typically take several years to happen. For the purpose of analytical clarity we have used a hierarchical framework in which a health policy track, i.e., a new public health-based harm reduction policy, was manifested and aligned side-by-side with the old repressive-control policy, the drug policy track (Hakkarainen et al., 2007) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

A hierarchical dual policy track framework.

To enable the reconstruction of key events and decisions, we used a within-case empirical analysis i.e., acquiring an in-depth understanding and description of a delimited case, such as the 2006 NEP law (Svensk författningssamling [Swedish Code of Statue]. (SFS 2006:323), 2006). This allowed us to trace, triangulate and analyse subtle and often complex multi-faceted policy and decision-making processes or triggering-events associated with change (Cook et al., 2010; Eisenhardt, 1989; Tammi, 2007). Furthermore, and from an actor-coalition perspective, we analysed how disagreements, problems and evidence were formulated and addressed on public platforms, influencing drug and health policy-making from a somewhat unanimous zero-tolerance approach with few critical voices (Lenke & Olsson, 1996; Tham, 1995), to a more polyphonic health-related public discussion in the new millennium (Eriksson & Edman, 2017). The empirical material used in this analysis consists of documents from 1980 and forward identified from several sources, mostly government agency publications including the four important and independent government health agencies: the National Board of Health and Welfare, the Institute for Infectious Disease Control, the National Institute of Public Health, 1 the Public Health Agency of Sweden and the Swedish Government. Documents were collected using a document snowballing sampling technique. Documents were first identified through references used for the 2006 NEP law proposal (Government Bill [GB]. (Prop. 2005/06:60), 2005). Thereafter these referenced documents were screened using several search terms based on previous research: harm reduction, drug policy, health policy, NEP, HIV, HCV, drug abuse or use, injection, needle, syringe and PWID (in Swedish: skademinimering, drogpolicy, drogpolitik, hälsopolicy, hälsopolitik, sprutbytesprogram, sprututbytesprogram, HIV, hepatit, intravenöst, missbruk, narkotikabruk, drogbruk, injektion, nål, kanyl, spruta, drogmissbrukare, injicera, droger, narkoman), and in relation to our study focus on NEP development. Any additional references found were likewise screened until no references could be found. For 1986–2007, documents were screened and collected retrospectively, and for 2008–2017 they were screened and collected prospectively. Most documents such as scientific research, grey literature, policy, laws and debates in printed media were published during the time period 2000–2017. Data collection was complemented using a participatory approach with the research team being actively involved in producing certain documents. Key excerpts relating to the search terms were extracted and the historical context was deconstructed in relation to our interpretation of that which best articulated the main issues in NEP development within the Swedish drug and health policy, and concept of our hierarchical dual policy track framework (Figure 2). In total, 150 documents were identified and read several times. Of these, and based on the search terms, the research team identified 75 key documents which were analysed in-depth. The remaining 75 documents were discarded as they either duplicated information already acquired, or failed to contribute to any further understanding of NEP development in Sweden.

Results

Our findings are presented within the identified and reconstructed context of three separate evolutionary phases: reorientation, stalemate and development. These phases are delimited in relation to specific key events, as used by Bergersen Lind for analysing the evolution of the Norwegian drug context (Bergersen Lind, 1974). Each constructed phase incorporates important public and policy trends and events on drug use, BBV, health and harm reduction services of importance. In the first phase of 2000–2005 (reorientation), after presenting key events and documents, we analyse how a landmark government commissioned investigation reviewing society’s drug policy efforts since early 1980, came to influence political willingness, focus and harm reduction policies. Further, we analyse how harm reduction eventually became more accepted with changes in public health policy, giving birth to a dual drug and health policy track and Sweden’s first NEP law. In the second phase of 2006–2011 (stalemate), key findings are presented, after which we analyse how the NEP law was implemented, and followed by repeated political resistance. Further, we look at how key government agencies changed policy positions influencing actor-coalition dynamics. During this phase, PWID were exposed to a large HIV outbreak, however without any new NEP being launched. In the third phase of 2012–2017 (development), our final findings are followed by an analysis into a continued build-up of evidence, change in key actor-coalitions and political decision-making. Further, we explore how these processes reduced space for disbelief and discrediting, leading to a revised NEP law being implemented including a significant scale-up of NEP. Based on our analyses of these three constructed phases, we draw conclusions and discuss how the Swedish NEP case can contribute to a possible scale-up of harm reduction services in the world and in relation to the WHO and UNAIDS 2030 global hepatitis and HIV goals.

Phase 1: Reorientation – A change of trend in Sweden’s drug and health policy and the law for needle exchange

Following decades of contradiction regarding NEP, the first analysed phase began in the year 2000 and covered five years of events and processes, taking place under a Social-Democrat-led government. The phase started with an investigation of Sweden’s contemporary drug policy “Choice of path – the drug policy challenge”. The investigation marked a significant development in focus compared to previous repression-control zero-tolerance drug policy focus (Figure 1) (Statens Offentliga Utredningar [Swedish Government Official Reports]. (SOU 2000:126), 2000). An emerging public tolerance towards drugs in Swedish society was noted in the investigation, and contrary to previous concentration on harsher measures, the individual drug user perspective was highlighted. Access to healthcare and infectious disease treatment was promoted and now without a requirement for people to quit drug use immediately. Quitting drugs was considered a long, drawn-out and complicated process needing collaboration of several actors, and NEP closely linked to the social services were considered as possibly useful in this process (Statens Offentliga Utredningar [Swedish Government Official Reports]. (SOU 2000:126), 2000).

Shortly after the release of the investigation, the National Board of Health and Welfare again positively evaluated Sweden’s two NEP, considering them as complementary to other treatment and rehabilitation measures and not to undermine the drug-free society goal (Socialstyrelsen [The National Board of Health and Welfare], 2001). This time, the government was asked to take a decision on their trial status, either banning or making NEP permanent programmes. The NEP issue was, however, handled within a larger policy context when the government proposed a wider public health policy framework (Government Bill [GB]. (Prop. 2002/03:35), 2002). This framework initiated a separation between the drug and health policies through a new national drug action plan including a forthcoming NEP legislation investigation (Government Bill [GB]. (Prop. 2001/02:91), 2002). With this change also came a shift in focus from drug substances towards drug use environments and lifestyle factors, including individual negative health consequences from unsterile syringe use (Government Bill [GB]. (Prop. 2001/02:91), 2002). A special national drug coordinator was appointed to oversee the work, drawing similar conclusions as previous and positive NEP evaluations, which included the need for collaboration with the social services (Fries, 2003). These conclusions were later echoed in another government investigation on Sweden’s HIV/AIDS policy (Statens Offentliga Utredningar [Swedish Government Official Reports]. (SOU 2004:13), 2004). Against the growing knowledge and ongoing reorganisation of the overall public health policy framework, the Social Democrat government in 2005 presented two separate national action plans: The National Alcohol and Drug Action Plans, 2006–2010 and A National Strategy Against HIV/AIDS and Certain Other Contagious Diseases, 2006–2016. The drug action plan, still with a drug-free society goal, now emphasised the social and health-related vulnerability of PWID while shifting focus from a previous repression-control model towards one of individual-centred focus (Government Bill [GB]. (Prop. 2005/06:30), 2005). The first national HIV strategy in Sweden aimed at controlling and reducing high levels of reported BBV among PWID – 800 HIV cases were reported in 1985–2005 and 39,000 HCV cases were reported in 1990–2005 (Figure 1) Departementsskrivelse [Ministerial Report]. (Skr. 2004/05:152), 2005) (Axelsson M., personal communication, November, 2017) – while also underlining the importance of NEP in the continuum of care, proposing a new NEP law (Government Bill [GB]. (Prop. 2005/06:60), 2005). Most consultative bodies, including the key government health agencies the National Board of Health and Welfare and the Institute for Infectious Disease Control, supported a NEP law, contrary to the National Institute of Public Health and some regions and municipalities rejecting NEP in their entirety (Government Bill [GB]. (Prop. 2005/06:60), 2005). Critics opposed to the new law requested more evidence of their usefulness (Eriksson & Edman, 2017) and disagreements also permeated politics, NGO and the research community. This was highlighted in an NGO-published report critical of available research on NEP effectiveness (Käll et al., 2005), which in turn was criticised as being biased and of inferior quality by researchers (Antoniusson et al., 2005). The political debate also divided political parties themselves. Politicians were arguing from an individual ideological standpoint rather than basing their judgement on scientific evidence, illustrating an underlying individual ideological dimension (Eriksson & Edman, 2017). In parallel to these debates in Sweden, the international community had, however, reached a consensus on NEP effectiveness in reducing HIV among PWID (WHO, 2004).

In summary, the first phase 2000–2005 under a Social-Democrat-led government comprised several events, emergence of new actor-coalitions, build-up of knowledge and intense debates among key-actors. These factors would all contribute to influencing a reorientation of the Swedish drug and health policy. The first NEP in the 1980s were launched in a highly politicised, unidirectional and strict drug policy context, supported by a mobilised social movement with strong beliefs. The concept of harm reduction was alien to most politicians and society as a whole, and was widely believed to maintain or even increase injection drug use in society (McAdam et al., 1996). However, the fundamental and exclusive goal of a drug-free society in Sweden we argue, came under scrutiny with the “Choice of path” investigation (Statens Offentliga Utredningar [Swedish Government Official Reports]. (SOU 2000:126), 2000). The investigation introduced the perspective of vulnerability and complexity around individual drug use, in line with similar developments in Norway and Denmark in the late 1990s (Houborg & Bjerge, 2011; Skretting, 2014; Tammi, 2007). This change in focus was further reinforced with the reorientation of the drug policy under a wider public health policy framework and introduction of a public-health-based HIV strategy. It could also be argued that support from a number of factors – actor-coalitions and foremost key government agencies and researchers, political leadership through an appointed national drug coordinator, the international community, continued build-up of research highlighting NEP usefulness and an exceptionally high number of reported HCV and HIV cases – provided enough momentum and necessary instruments for change regarding NEP. However, several key-actors still opposed NEP.

Further, the intention regarding collaboration between NEP and the social services with their important role in drug treatment and social care, was well intended. This, however, kept an important yet adverse key-actor in a decisive position on starting new NEP. The complex political situation with politicians advocating individual beliefs rather than existing evidence, caused division and competition between political actor-coalitions and within parties themselves. These political indifferences effectively hindered political unity and willingness to capitalise on opportunities to push for NEP development. The apparent division on NEP was further enhanced by arguments from key-actors that evidence for NEP efficacy was either inconclusive or insufficient. Despite the turmoil, the presented national action plans for drugs and HIV manifested an embryonic dual drug and health policy track structure, creating enough momentum for change in which a new NEP law was proposed and accepted (Figure 2).

Phase 2: Stalemate – The law aftermath and issue of dual ownership

The second phase, 2006–2011, started with the implementation of the new NEP law, which, however, came with restrictions (Svensk författningssamling [Swedish Code of Statue]. (SFS 2006:323), 2006). To start a NEP, the law required an application to the National Board of Health and Welfare from the region, with approval from the regional Healthcare Board, and the municipality-level Social Welfare Board (social services). This consequently involved local politicians in the decision-making process, effectively inserting a veto possibility. As a result, the NEP issue was split on both the drug and health policy track, which was also reflected in the national NEP regulations later released by the National Board of Health and Welfare (Socialstyrelsen [The National Board of Health and Welfare]. (SOSFS 2007:2), 2007). On national level, the newly elected right-wing/centre government in 2007 decided to terminate the national drug coordinator position and instead establish a national secretariat tasked with coordinating the implementation of national drug policy (Socialdepartementet [Ministry of Health and Social Affairs], 2007; Statens Offentliga Utredningar [Swedish Government Official Reports]. (SOU 2008:120), 2008). To this, an advisory council was linked which included representatives from authorities, academia, civil society and noteworthy NGO with ties to the repressive-control movement (Drugnews, 2008; ReActNow, 2009). In parallel to these developments, a report from the National Institute of Public Health brought up the issue of harm reduction in relation to a national restrictive approach and the goal of a drug-free society, suggesting better effect in achieving the goal if supported by effective control, restrictive legislation and the upholding of social norms and attitudes (Statens Folkhälsoinstitut [National Institute of Public Health], 2008). Contrarily, in the health policy track the other key government health agency, the National Board of Health and Welfare, embraced NEP as a feasible tool in new national guidelines for drug abuse however, stressing the need for better collaboration between regions and the social services. The agency also noted a dividing line between those either accepting or distancing themselves from NEP (Socialstyrelsen [The National Board of Health and Welfare], 2007).

During 2007–2008, a large HIV outbreak occurred among PWID in Stockholm, prompting intensified responses and calls for NEP from, among others, the Institute for Infectious Disease Control (Fredriksson, 2008). Local politicians, however, stayed hesitant and requested more evidence on NEP effectiveness in Sweden (Tidningarnas Telegrambyrå, 2007). Concurrently, international guidelines on how to run NEP were released (WHO et al., 2007) and an informal NGO-operated NEP had opened in Stockholm (SVT Nyheter, 2007) (Figure 1). These events prompted both an official regional-sponsored investigation and a stand-alone research survey into the effectiveness of NEP in Stockholm, the capital of Sweden. The research survey found widespread risk behaviour for HIV and HCV among PWID in Stockholm, though it did not mention NEP in the conclusions or recommendations (Britton et al., 2009). The official investigation, however, concluded that NEP could be effective in collaboration with other activities, recommending a trial NEP (Procyon-Capire, 2009). These conclusions were later reinforced by the National Board of Health and Welfare (Socialstyrelsen [The National Board of Health and Welfare], 2009).

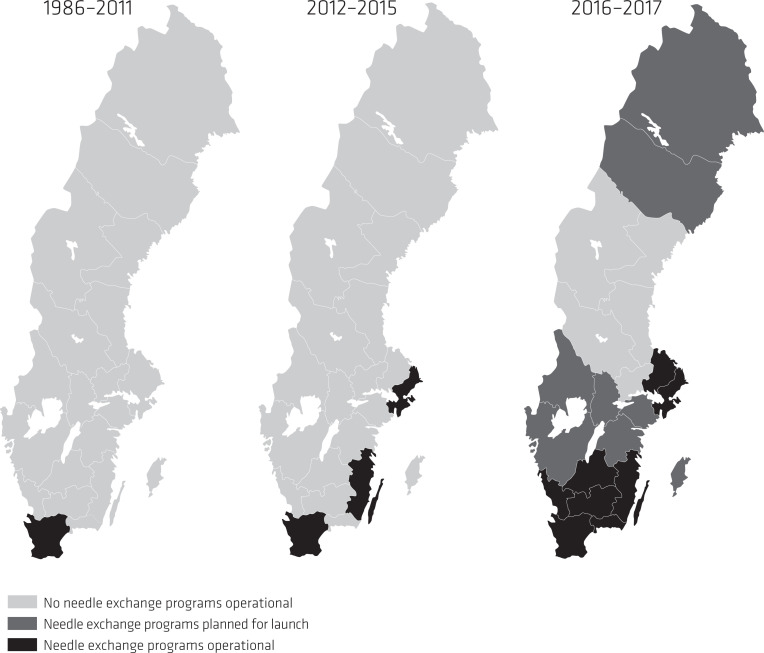

Internationally, evidence for NEP continued to accumulate with the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) stressing NEP effectiveness (EMCDDA, 2010), and the fact that harm reduction was becoming mainstream policy in Europe (EMCDDA, 2010). In Sweden, the NEP status quo was addressed when the government agencies the National Board of Health and Welfare, the Institute for Infectious Disease Control, now together with the previous proponent the National Institute of Public Health, published a debate article in one of Sweden’s largest daily newspapers. In the debate article the three health agencies called for a change, acknowledgement of scientific evidence and to draw on lessons learnt from the Finnish case with NEP development (Tammi, 2005). Most importantly, these agencies argued that NEP would not impose a liberal drug policy in Sweden encouraging regions to start NEP (Holm et al., 2009). For the first time, the National Institute of Public Health also acknowledged that NEP could be effective in preventing BBV (Statens Folkhälsoinstitut [National Institute of Public Health], 2010). This statement was later supported by a government HIV progress report noting a growing number of HCV cases and that the large HIV outbreak in the capital of Stockholm could be partially explained by NEP absence (Departementsskrivelse [Ministerial Report], 2010; Skar et al., 2011). In 2010, a NEP was launched in Helsingborg, Skåne region as Sweden’s third NEP (Figure 1). In the same period, a study into NEP development in Sweden’s 21 regions (Figure 3) found that nearly all regions and their respective medical officers in charge of infectious disease surveillance and control, were in favour of starting NEP (Leandersson, 2011).

Figure 3.

Development of NEP in Sweden’s 21 regions, 1986-2017.

The study also concluded that nearly all 21 regional medical officers expressed hopelessness and frustration of not having the decision-making power, being left to local politicians’ ability to veto. Further, the results also pointed to a perceived general lack of knowledge among local decision-makers, with the medical officers calling for national guidelines on NEP to counter this problem (Leandersson, 2011).

In the drug policy track, a new national drug action plan was presented in 2010, still with the goal of a drug-free society (Government Bill [GB]. (Prop. 2010/11:47), 2010). Compared to previous national plans, focus had now changed from prevention of BBV or NEP, to drug-related surrounding factors such as road accidents, violence, injuries, deaths and so forth (Government Bill [GB]. (Prop. 2010/11:47), 2010). The national plan also had an objective for Sweden, to promote a more restrictive approach on the international policy arena. This objective came from an earlier investigation pointing to Sweden’s general ambivalent position on harm reduction, expressing concern that international actors were pushing in a permissive direction like in the early 2000s. The investigation consequently underlined that Sweden needed more clear standpoints on the international arena and in relation to a repression-control approach (Statens Offentliga Utredningar [Swedish Government Official Reports]. (SOU 2011:66), 2011). In parallel, a government-commissioned investigation on the Swedish drug abuse and dependence care system concluded that NEP appeared effective. The investigation, however, also stressed that collaboration between regions and municipalities was still found to be inadequate (Statens Offentliga Utredningar [Swedish Government Official Reports]. (SOU 2011:35), 2011). It also noted that the municipality-level social services often had a moralising approach towards drug use and drug addiction, therefore suggesting the municipality NEP veto be removed (Statens Offentliga Utredningar [Swedish Government Official Reports]. (SOU 2011:35), 2011).

This second phase of 2006–2011, under a right-wing/centre-led government, started with the implementation of the new NEP law (Svensk författningssamling [Swedish Code of Statue]. (SFS 2006:323), 2006), but would be characterised by a stalemate in NEP development. It has been argued that the law containing a veto was modelled out of fear of possible negative consequences for Swedish drug policy. Also, that NEP as a link in the continuum of care, was subordinate to substance abuse treatment and consequently undermining its infectious disease perspective (Tryggvesson, 2012). Despite a NEP law, factors such as repeated political hindering, termination of the drug policy coordinator role including the creation of an intra-governmental structure providing NGO critical of NEP with direct communicative access to the government, we argue, hindered overall unity around NEP development. In addition, that this intra-governmental political structure considering NEP a non-issue, influenced a shift in focus from individual drug use, towards that of other drug-related consequences such as road accidents. These events, processes and decisions influenced the balance in favour of those actor-coalitions either against or indifferent to NEP, enough to keep ascendancy of the NEP issue under drug policy control. A control that was manifested through the veto decision-making power for municipalities and local politicians leaving no new NEP to start. Sweden’s shift in focus during this time also contradicted how the other Nordic countries were working to scale-up harm reduction services (Arponen et al., 2008; Houborg & Bjerge, 2011; Skretting, 2014). Despite a triggering-event like the large HIV outbreak among PWID in Stockholm, and contrary to the effects of similar events as with NEP development in Finland (Hakkarainen et al., 2007), scientifically grounded guidelines on NEP effectiveness from both domestic and international investigations, research and voices raised by key-actors for launching NEP, was not enough. This accumulated body of knowledge was met with counter-calls for more evidence by actors either doubtful about or opposed to NEP, effectively hindering unity and capitalisation on the opportunity for change.

At the end of the second phase, the officially sponsored investigation suggesting a trial NEP in Stockholm, with the support of key government health agencies like the National Board of Health and Welfare, the Institute for Infectious Disease Control and now also the National Institute of Public Health, again shifted the actor-coalition balance in favour of NEP. This shift was also supported by a growing body of evidence and international actors proposing NEP. With additional support from government investigations from the drug policy track, unity among new actor-coalitions, increased know-how and the start of Sweden’s third NEP in 2010, set a change in motion which would come to reduce space for disbelief and discrediting of NEP. The result of this we argue, claimed the interpretative prerogative of NEP as a health policy measure.

Phase 3: Development – Sweden sees the consolidation of a dual drug and health policy track

The third phase of 2012–2017, commenced with Kalmar region starting Sweden’s fourth NEP (Figure 1), making it the second region in Sweden to start a NEP since 1986. Following this, Sweden would come to see an acceleration in NEP development. The vulnerability of PWID was continuously emphasised and this time in a report finding young PWID in Swedish compulsory care institutions at high risk for BBV (Richert, 2012). In addition, in 2012 the EMCCDA and the European Centre for Diseases Prevention and Control (ECDC) published a key report on evidence for NEP effectiveness in prevention of BBV (ECDC & EMCDDA, 2012). What followed in 2013 was the Swedish government decision to address the issue with collaboration between the regions and municipalities, by introducing an obligation for them to enter into joint agreements on cooperation on drug dependency care (Government Bill [GB]. (Prop. 2012/13:77), 2013). In parallel and for the first time in Swedish history, the number of active PWID in Sweden was estimated: approximately 8,000 people, with 54% residing in the three major metropolitan cities (Socialstyrelsen [The National Board of Health and Welfare], 2013). In 2013, five years after the HIV outbreak, the capital city of Stockholm started its first official NEP, which was followed by another NEP opening in Skåne region in 2014. At the time, a total of six NEP were running in Sweden (Figure 1).

The tide is turned in Sweden regarding NEP development

In 2014, the Social Democrats regained power. The following year a government report concluded that Sweden was still seeing high numbers of drug-related deaths and large numbers of people engaged in harmful drug use, despite increased care provision (Departementsskrivelse [Ministerial Report]. (Skr. 2015/16:86), 2016). At the same time, and against the prevalent burden of BVV among PWID, the Public Health Agency of Sweden released a national set of guidelines for health promotion and prevention of hepatitis and HIV among PWID (Folkhälsomyndigheten [The Public Health Agency of Sweden], 2015). The guidelines put emphasis on available evidence on NEP effectiveness while suggesting continued scale-up of these programmes, however, in the broader form of low-threshold services including other drug and health supportive measures (Folkhälsomyndigheten [The Public Health Agency of Sweden], 2015). The effectiveness of NEP was later echoed in national guidelines for care and support in addiction, released by the National Board of Health and Welfare (Socialstyrelsen [The National Board of Health and Welfare], 2015). Shortly thereafter, the Minister of Health Care and Public Health in an opinion article, declared it was high time to revise the 2006 NEP law and remove the municipality veto in order for more NEP to start (Holmqvist, 2015). The NEP law revision that followed concluded NEP to be effective in prevention of BBV, and not to contradict a restrictive view of drugs (Departementsskrivelse [Ministerial Report]. (Ds 2015:56), 2015). Consequently, in early 2017 the revised NEP law (Svensk författningssamling [Swedish Code of Statue]. (SFS 2017:7), 2017) was passed in the Swedish parliament, with 226 in favour, 72 against, and 51 not voting (Departementsskrivelse [Ministerial Report], 2016). All votes against came from the right-wing party Moderaterna. By 2017, 13 NEP were operational (Figure 1) in eight of 21 regions with a further eight NEP planned for launch in 2018 (Figure 3).

In summary, during this third phase of NEP development, 2012–2017, international guidelines on harm reduction had already become mainstream, and had been implemented in many countries across the world. National evidence on NEP effectiveness in Sweden continued to accumulate, supported by PWID estimations making the associated challenges more comprehensible, as called for both by the international research community (Grebely et al., 2017) and national actor-coalitions. Political leadership also shifted from a right-wing/centre to a Social-Democrat-led government, bringing back the individual-centred focus and challenge with the burden of BBV among PWID. However, even though three new NEP opened (2012–2014), the NEP issue continued to be split between the drug and health policy tracks given the municipality veto, allowing for local resistance to continue. With the shift in overall political leadership, legislation obliging regions and municipalities to collaborate, change in key-actor-coalitions in favour of NEP, and a continued accumulating body of NEP evidence and experience, provided the health policy track with a factual base, an organised approach and clear purpose. The launch of complementary national public health and drug guidelines, supported by international research and the Minister of Health Care and Public Health’s call for a revision of the NEP law, created enough momentum for change. As a result, in 2016–2017 several NEP were launched, leaving three quarters of Sweden’s regions offering NEP services (Figure 3) (Folkhälsomyndigheten [The Public Health Agency of Sweden], 2018).

Discussion: The Swedish case and its possible significance for the continued scaling-up of harm reduction services in the world

Our aim was to analyse how a variety of accumulating factors, events, decisions and a continuous build-up of evidence within a drug and health policy framework, slowly created space for change regarding NEP development and in a context strictly opposed to harm reduction. We analysed policy processes and traced back and reconstructed key events and decisions using actor-coalition, time and context-related situational factors. This allowed us to analyse how the NEP issue was influenced to resist or effect change, with regard to our hierarchical dual drug and health policy track framework and its structural levels: the deep core, policy core and secondary aspects (Figure 2). In many European countries, drug policy changed towards harm reduction including NEP typically as the result of trigger-events. Sweden, however, maintained its repressive-control and strict drug policy guided by the overarching goal of a drug-free society for more than three decades.

Even though Nordic countries also ascribed to forms of repressive-control policies – e.g., until 2012, Norway had a goal of a drug-free society – health policy in Sweden was never fully allowed to equal the drug policy domain with regard to NEP development (Houborg & Bjerge, 2011; Koman, 2019; Skretting, 2014). Most of the European NEP scale-up took place during the 1990s, when national approaches and policies converged in the fight against BBV among PWID (Hedrich et al., 2008). However, despite experiencing similar events, no new NEP were started in Sweden for a period of 23 years, despite being sanctioned by law. During this period, public health policy dimension knowledge on NEP continued to develop and be clarified, which consequently and simultaneously led to the manifestation of a separate dual drug and health policy track in Sweden (Hakkarainen et al., 2007). A separation process having taken place earlier in both Norway and Finland (Koman, 2019; Tammi, 2005).

We argue that these turns of events and their consequences were partially the result of the individual-centred perspective being brought into focus in the drug policy domain. The consequences of this were that drug policy and the goal of a drug-free society were indirectly challenged, but also complemented, by a reinforced health policy dimension with a public-health-based harm reduction approach and overall vision (Figure 2). The dynamics of change and development in Sweden on and in-between the respective levels in our hierarchical framework, took place simultaneously and in constant interaction. However, contrary to the historical European NEP development, changes in overall political leadership and key-actor-coalitions in Sweden created an irregularity in how NEP-related events unfolded, took shape and influenced NEP implementation. Our analyses show that these changes did not follow a clear and logical cause–effect pattern. Changes and decisions being taken were rather the result of a combination of haphazard key-events and processes, in turn supported by a stable, long-term and continuous build-up of evidence. This continued enhanced clarity on national PWID and NEP knowledge, consequently made it hard for key-actors to ignore available facts (Tham, 2005).

The prerequisites for change on the vision level and consequent split of the health and drug policy tracks, as illustrated in our framework (Figure 2), were fully realised with the introduction of separate national health and drug action plans. These plans brought clarity to the respective tracks’ strategies, policy positions and mandate. Changes in key-actor coalition dynamics with the National Institute of Public Health changing its policy position on NEP, created openness to evidence and experience, which continued to accumulate throughout the remaining constructed phases. Adding to this was the number of triggering-events such as HIV outbreaks and launching of new NEP, which in the long run created enough momentum to remove space for disbelief and present instrumental considerations for policy change (Tham, 2005). Consequently, the accumulated effect of events led to directives for change, with the call coming from a superior jurisdiction to revise the NEP law. This call, and from this sender we argue, was the final stepping stone for overall change, and removal of the municipality veto, an idea of “forced collaboration” between NEP and the social services, presented already in 1988 (Departementsskrivelse [Ministerial Report]. (Skr. 1988/89:94), 1989). When the veto was removed, ownership of NEP development was fully transferred to the health policy track (Kübler, 2001) (Figure 2). This was in stark contrast to the NEP development in other Nordic countries. As an example, in 1999, the Minister of Social Affairs in Norway provided grants to municipalities looking to start low threshold services including needle exchange activities (Skretting, 2014) and in 2004, Finland made it mandatory for municipalities to start a NEP through law (Tammi, 2005).

However, despite long-term presence of harm reduction services, many countries to date still report PWID as a hard-to-reach population (Balayan et al., 2019). Studies suggest that eliminating BBV among PWID relies on high coverage of harm reductions services, which poses a challenge for countries or contexts where high coverage is not available (Fraser et al., 2018; Heffernan et al., 2019). Absence of these services is in many cases the result of restrictive policies and laws (WHO, 2019). For many countries, to reach PWID with comprehensive harm reduction services as suggested by the WHO (2017), will likely involve starting or to scaling-up existing NEP. Also, countries with low prevalence of HCV or HIV will have to find ways to reach those high-risk PWID not already covered by existing harm reduction services. A possible scenario here is for these countries to introduce other evidence-based yet today more uncommon services, like drug consumption rooms and heroin assisted treatment programmes (EMCDDA, 2019; Scott et al., 2018). A scale-up scenario of this magnitude, with some 120 countries currently not offering forms of NEP we argue, could generate a “second wave” of harm reduction implementation such as when Europe scaled-up NEP in 1980–1990. For many national governments, a scenario like this could prove a great challenge and possibly start or reintroduce societal and political controversy, as was demonstrated in the Swedish case with NEP development (Davidson & Howe, 2014).

Lessons from the case of Sweden, historically considered one of the more strict drug policy contexts (Eriksson & Edman, 2017), could provide valuable insight for countries and actors on how to circumvent costly time- and resource-intensive obstacles and processes involving ideological and individual moral dimensions on both policy and implementation levels. Contemporary examples show how extensive these processes can prove to be. Denmark introduced drug consumption rooms and heroin assisted treatment in 2009, 23 years after their first NEP (EMCDDA, 2019). Norway introduced a temporary law in 2004 allowing municipalities to start drug consumption rooms (Skretting, 2014) and plan to launch heroin assisted treatment programmes in 2020 (Helsedirektoratet [The Norwegian Directorate of Health], 2018). In Finland on the other hand, the implementation of drug consumption rooms is currently at a stand-still due to political challenges (Talking Drugs, 2018). Based on our findings in this study, a country introducing or scaling-up harm reduction services, could therefore benefit from building a solid base of research evidence and experience. Further, we suggest identifying key-actor-coalitions likely to be involved in an implementation process and engaging them early on, especially in settings with existing veto-players (Resnick et al., 2018). A solid base of available information will help reduce space for disbelief and discrediting, turn confusion into clarity, and create the basis for consensus, clear leadership and long-term political commitment. Proactive work on these platforms can also help in capitalising on trigger-events when they occur, to promote change.

Notes

The Institute for Infectious Disease Control and the National Institute of Public Health were terminated in 2013 and merged into the new government agency the Public Health Agency of Sweden, launched in 2014.

Footnotes

Author note: Data are available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of Karolinska Institutet. All authors contributed to, read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. It should however be noted that the main author was employed by the Public Health Agency of Sweden at the time of the study.

Funding: The authors received the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Public Health Agency of Sweden.

ORCID iD: Niklas Karlsson  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0523-5397

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0523-5397

Contributor Information

Niklas Karlsson, Department of Public Health Sciences, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden; and Department of Public Health Analysis and Development, Public Health Agency of Sweden, Solna, Sweden.

Torsten Berglund, Department of Public Health Sciences, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden; and Department of Public Health Analysis and Development, Public Health Agency of Sweden, Solna, Sweden.

Anna Mia Ekström, Department of Public Health Sciences, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden; and Department of Medicine Huddinge, Division of Infectious Diseases, Karolinska Institutet, Karolinska University Hospital Huddinge, Stockholm, Sweden.

Anders Hammarberg, Centre for Psychiatry Research, Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden; and Stockholm Centre for Dependency Disorders, Stockholm Health Care Services, Stockholm County Council, Sweden.

Tuukka Tammi, Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare, Finland.

References

- Aktionsgrupp mot narkotika [Action Group Against Drugs]. (1991). Vi ger oss aldrig! [We will never give up!]. Socialdepartementet. [Google Scholar]

- Amundsen E. J., Eskild A., Stigum H., Smith E., Aalen O. O. (2003). Legal access to needles and syringes/needle exchange programmes versus HIV counselling and testing to prevent transmission of HIV among intravenous drug users: A comparative study of Denmark, Norway and Sweden. European Journal of Public Health, 13(3), 252–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoniusson E.-M., Kristiansen A., Laanemets L., Svensson B., Tops D. (2005). Sprutbytesfrågan: en granskning av en forskningsgenomgång om effekter av sprutbytesprogram [The needle exchange question: A review of a research review on the effects of needle exchange programmes]. Socialhögskolan, Lunds universitet. [Google Scholar]

- Arponen A., Brummer-Korvenkontio H., Liitsola K., Salminen M. (2008). Trust and free will as the keys to success for the low threshold service centers (LTHSC): An interdisciplinary evaluation study of the effectiveness of health promotion services for infectious disease prevention and control among injecting drug users. Publications of the National Public Health Institute B24 / 2008. Helsinki. [Google Scholar]

- Balayan T., Oprea C., Yurin O., Jevtovic D., Begovac J., Lakatos B., Sedlacek D., Karpov I., Horban A., Kowalska J. D., & Euro-guidelines in Central and Eastern Europe Network Group. (2019). People who inject drugs remain hard-to-reach population across all HIV continuum stages in Central, Eastern and South Eastern Europe: Data from Euro-guidelines in Central and Eastern Europe Network. Infectious Diseases, 51(4), 277–286. 10.1080/23744235.2019.1565415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergersen Lind B. (1974). Narkotikakonflikten: stoffbruk og myndighetskontroll [The drug conflict: drug use and government control]. Universitetsforlaget. [Google Scholar]

- Bergmark A. (1998). Expansion and implosion: The story of drug treatment in Sweden. In Klingemann H., Hunt G. (Eds.), Drug treatment systems in an international perspective: drugs, demons, and delinquents (pp. 33–47). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Britton S., Hillgren K., Marosi K., Sarkar K., Elofsson S. (2009). Baslinjestudie om blodburen smitta bland injektionsnarkomaner i Stockholms län 1 juli 2007 – 31 augusti 2008 [Baseline study on blood-borne infections among injection drug addicts in Stockholm County]. Karolinska Institutet. [Google Scholar]

- Bruggmann P., Litwin A. H. (2013). Models of care for the management of hepatitis C virus among people who inject drugs: One size does not fit all. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 57(Suppl 2), S56–S61. 10.1093/cid/cit271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairney P. (2011). Understanding public policy: Theories and issues. Palgrave MacMillian. [Google Scholar]

- Cook C., Bridge J., Stimson G. V. (2010). The diffusion of harm reduction in Europe and beyond. In Rhodes T., Hedrich D. (Eds.), Harm reduction: Evidence, impacts and challenges (pp. 37–56). EMCDDA, Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz M. F., Patra J., Fischer B., Rehm J., Kalousek K. (2007). Public opinion towards supervised injection facilities and heroin-assisted treatment in Ontario, Canada. International Journal of Drug Policy, 18(1), 54–61. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2006.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson P. J., Howe M. (2014). Beyond NIMBYism: Understanding community antipathy toward needle distribution services. International Journal on Drug Policy, 25(3), 624–632. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.10.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day E., Broder T., Bruneau J., Cruse S., Dickie M., Fish S., Grillon C., Luhmann N., Mason K., McLean E., Trooskin S., Treloar C., Grebely J. (2019). Priorities and recommended actions for how researchers, practitioners, policy makers, and the affected community can work together to improve access to hepatitis C care for people who use drugs. International Journal on Drug Policy, 66, 87–93. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day E., Hellard M., Treloar C., Bruneau J., Martin N. K., Ovrehus A., Dalgard O., Lloyd A., Dillon J., Hickman M., Byrne J., Litwin A., Maticic M., Bruggmann P., Midgard H., Norton B., Trooskin S., Lazarus J. V., Grebely J., & International Network on Hepatitis in Substance Users (INHSU). (2018). Hepatitis C elimination among people who inject drugs: Challenges and recommendations for action within a health systems framework. Liver International, 39(1), 20–30. 10.1111/liv.13949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Departementsskrivelse [Ministerial Report]. (2010). UNGASS Country progress report. Regeringskansliet. [Google Scholar]

- Departementsskrivelse [Ministerial Report]. (2016). Votering: betänkande 2016/17: SoU4 Ökad tillgänglighet till sprututbytesverksamheter i Sverige [Vote: Increased availability of needle exchange programmes in Sweden]. Sveriges Riksdag. https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/omrostning/votering-betankande-201617sou4-okad_H419SoU4p1 [Google Scholar]

- Departementsskrivelse [Ministerial Report]. (Ds 2015:56). (2015). Ökad tillgänglighet till sprututbytesverksamheter i Sverige [Increased access to needle exchange programmes in Sweden]. Regeringskansliet. [Google Scholar]

- Departementsskrivelse [Ministerial Report]. (Skr. 1988/89:94). (1989). Om försöksverksamheten inom hälso- och sjukvården med utdelning av sprutor och kanyler till narkotikamissbrukare [Regarding experimental work within healthcare involving dispensing of syringes and needles to drug users]. Regeringskansliet. [Google Scholar]

- Departementsskrivelse [Ministerial Report]. (Skr. 1995/96:1). (1995). Utbytesverksamhet med rena sprutor till narkotikamissbrukare [Exchange of clean syringes to drug users]. Regeringskansliet. [Google Scholar]

- Departementsskrivelse [Ministerial Report]. (Skr. 2004/05:152). (2005). Insatser för narkotikabekämpning utifrån regeringens narkotikahandlingsplan [Drug-fighting efforts based on the government’s drug action plan]. Regeringskansliet. [Google Scholar]

- Departementsskrivelse [Ministerial Report]. (Skr. 2015/16:86). (2016). En samlad strategi för alkohol-, narkotika-, dopnings- och tobakspolitiken 2016–2020 [A comprehensive strategy for alcohol, narcotics, doping and tobacco policy]. Regeringskansliet. [Google Scholar]

- Drugnews. (2008). Regeringens ANT-råd utsett [Government alcohol, narcotics and tobacco council appointed]. Drugnews. http://drugnews.nu/2008/05/19/4497/ [Google Scholar]

- ECDC & EMCDDA. (2012). Technical report – Evidence for the effectiveness of interventions to prevent infections among people who inject drugs Part 1: Needle and syringe programmes and other interventions for preventing hepatitis C, HIV and injecting risk behaviour. ECDC. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt K. M. (1989). Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532–550. 10.5465/amr.1989.4308385 [Google Scholar]

- EMCDDA. (2010). Harm reduction: Evidence, impact and challenges. EMCDDA. http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/attachements.cfm/att_101257_EN_EMCDDA-monograph10-harm%20reduction_final.pdf [Google Scholar]

- EMCDDA. (2012). New heroin assisted treatment: Recent evidence and current practices of supervised injectable heroin treatment in Europe and beyond. EMCDDA. http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/insights/heroin-assisted-treatment [Google Scholar]

- EMCDDA. (2018). Drug consumption rooms: An overview of provision and evidence. EMCDDA. [Google Scholar]

- EMCDDA. (2019). Availability of selected harm reduction responses in Europe. EMCDDA. http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/print/countries/drug-reports/2018/turkey/harm-reduction_en [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson L., Edman J. (2017). Knowledge, values, and needle exchange programs in Sweden. Contemporary Drug Problems, 44(2), 105–124. [Google Scholar]

- Folkhälsomyndigheten [The Public Health Agency of Sweden]. (2015). Hälsofrämjande och förebyggande arbete med hepatit och hiv för personer som injicerar droger [Health promotion and prevention work with hepatitis and HIV for people who inject drugs]. Folkhälsomyndigheten. [Google Scholar]

- Folkhälsomyndigheten [The Public Health Agency of Sweden]. (2018). Den svenska narkotikasituationen [The Swedish drug situation]. Folkhälsomyndigheten. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser H. Martin N. K. Brummer-Korvenkontio H. Carrieri P. Dalgard O. Dillon J. Goldberg D. Hutchinson S. Jauffret-Roustide M. Kåberg M. Matser A. A. Matičič M. Midgard H. Mravcik V. Ovrehus A. Prins M. Reimer J. Robaeys G. Schulte B.…Hickman M. (2018). Model projections on the impact of HCV treatment in the prevention of HCV transmission among people who inject drugs in Europe. Journal of Hepatology, 68(3), 402–411. 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.10.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksson S. (2008). Ragnar Norrby vill ha sprutbyte även i Stockholm [Ragnar Norrby wants to have NEP also in Stockholm]. Dagens Medicin. https://www.dagensmedicin.se/artiklar/2008/02/25/ragnar-norrby-vill-ha-sprutbyte-aven-i-stockholm/

- Fries B. (2003). Sprututbyte [Needle exchange]. Mobilisering mot narkotika - Narkotikapolitisk samordning [Mobilisation against drugs – Drug policy coordination]. [Google Scholar]

- Gindi R. M., Rucker M. G., Serio-Chapman C. E., Sherman S. G. (2009). Utilization patterns and correlates of retention among clients of the needle exchange program in Baltimore, Maryland. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 103(3), 93–98. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.12.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Government Bill [GB]. (Prop. 1984/85:19). (1984). Om en samordnad och intensifierad narkotikapolitik [Regarding a coordinated and intensified drug policy] (Vol. Nr. 19). Parliament Documents. [Google Scholar]

- Government Bill [GB]. (Prop. 2001/02:91). (2002). Nationell narkotikahandlingsplan [National Drug Action Plan]. Swedish Parliament. [Google Scholar]

- Government Bill [GB]. (Prop. 2002/03:35). (2002). Mål för folkhälsan [Objectives for public health]. Swedish Parliament. [Google Scholar]

- Government Bill [GB]. (Prop. 2005/06:30). (2005). Nationella alkohol- och narkotikahandlingsplaner [National alcohol and drug action plans]. Parliament Documents. [Google Scholar]

- Government Bill [GB]. (Prop. 2005/06:60). (2005). Nationell strategi mot hiv/aids och vissa andra smittsamma sjukdomar [National strategy against HIV/AIDS and some other communicable diseases]. Parliament Documents. [Google Scholar]

- Government Bill [GB]. (Prop. 2010/11:47). (2010). En samlad strategi för alkohol-, narkotika-, dopnings- och tobakspolitiken [A cohesive strategy for alcohol, narcotic drugs, doping and tobacco policy]. Parliament Documents. [Google Scholar]

- Government Bill [GB]. (Prop. 2012/13:77). (2013). God kvalitet och ökad tillgänglighet inom missbruks- och beroendevården [Good quality and increased accessibility in drug abuse and addiction care]. Parliament Documents. [Google Scholar]

- Grebely J. Bruneau J. Lazarus J. V. Dalgard O. Bruggmann P. Treloar C. Hickman M. Hellard M. Roberts T. Crooks L. Midgard H. Larney S. Degenhardt L. Alho H. Byrne J. Dillon J. F. Feld J. J. Foster G. Goldberg D.…Dore G. J. (2017). Research priorities to achieve universal access to hepatitis C prevention, management and direct-acting antiviral treatment among people who inject drugs. International Journal on Drug Policy, 47, 51–60. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.05.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyarmathy V. A., Csák R., Bálint K., Bene E., Varga A. E., Varga M., Csiszér N., Vingender I., Rácz J. (2016). A needle in the haystack-the dire straits of needle exchange in Hungary. BMC Public Health, 16, 157. 10.1186/s12889-016-2842-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakkarainen P., Tigerstedt C., Tammi T. (2007). Dual-track drug policy: Normalization of the drug problem in Finland. Drugs: Education, Prevention & Policy, 14(6), 543–558. [Google Scholar]

- Hedrich D., Pirona A., Wiessing L. (2008). From margin to mainstream: The evolution of harm reduction responses to problem drug use in Europe. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 15(6), 503–517. 10.1080/09687630802227673 [Google Scholar]

- Heffernan A., Cooke G. S., Nayagam S., Thursz M., Hallett T. B. (2019). Scaling up prevention and treatment towards the elimination of hepatitis C: A global mathematical model. The Lancet, 393(10178), 1319–1329. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32277-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helsedirektoratet [The Norwegian Directorate of Health]. (2018). Prøveprosjekt - heroinassistert behandling – oppdrag nr. 34 [Prospect - Heroin assisted treatment] . Helse- og Omsorgsdepartementet. [Google Scholar]

- Holm L.-E., Carlson J., Wamala S. (2009). Sprutbyte för narkomaner är en viktig folkhälsofråga [Needle exchange for drug addicts is an important public health issue]. Dagens Nyheter. http://www.dn.se/debatt/sprutbyte-for-narkomaner-ar-en-viktig-folkhalsofraga/

- Holmqvist A. (2015). Ministern vill göra sprututbyte för narkomaner enklare [The minister wants to simplify needle exchange for drug addicts]. Aftonladet. http://www.aftonbladet.se/nyheter/article20327359.ab

- Houborg E., Bjerge B. (2011). Drug policy, control and welfare. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 18(1), 16–23. 10.3109/09687631003796461 [Google Scholar]

- Kåberg M., Karlsson N., Discacciati A., Widgren K., Weiland O., Ekström A. M., Hammarberg A. (2020). Significant decrease in injection risk behaviours among participants in a needle exchange programme. Infectious Diseases. Advance online publication. 10.1080/23744235.2020.1727002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kåberg M., Naver G., Hammarberg A., Weiland O. (2018). Incidence and spontaneous clearance of hepatitis C virus (HCV) in people who inject drugs at the Stockholm Needle Exchange-Importance for HCV elimination. Journal of Viral Hepatitis, 25(12), 1452–1461. 10.1111/jvh.12969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Käll K., Hermansson U., Rönnberg S., Bergvall B. (2005). Sprututbyte - En genomgång av den internationella forskningen och den svenska debatten [Needle exchange: A review of international research and the Swedish debate] . Fri Förlag. [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson N., Santacatterina M., Käll K., Hägerstrand M., Wallin S., Berglund T., Ekström A. M. (2017). Risk behaviour determinants among people who inject drugs in Stockholm, Sweden over a 10-year period, from 2002 to 2012. Harm Reduction Journal, 14, 57. 10.1186/s12954-017-0184-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimber J., Dolan K., Wodak A. (2005). Survey of drug consumption rooms: Service delivery and perceived public health and amenity impact. Drug and Alcohol Review, 24(1), 21–24. 10.1080/09595230500125047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koman R. (2019). Sustaining the development goals in drug approaches in Europe, Norway and Singapore. Beijing Law Review, 10, 882–912. 10.4236/blr.2019.104048. [Google Scholar]

- Kübler D. (2001). Understanding policy change with the advocacy coalition framework: An application to Swiss drug policy. Journal of European Public Policy, 8(4), 623–641. 10.1080/13501760110064429 [Google Scholar]

- Larney S., Peacock A., Leung J., Colledge S., Hickman M., Vickerman P., Grebely J., Dumchev K. V., Griffiths P., Hines L., Cunningham E. B., Mattick R. P., Lynskey M., Marsden J., Strang J., Degenhardt L. (2017). Global, regional, and country-level coverage of interventions to prevent and manage HIV and hepatitis C among people who inject drugs: A systematic review. The Lancet: Global Health, 5(12), e1208–e1220. 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30373-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leandersson Å. (2011). Smittskyddsläkares uppfattningar om sprutbytesverksamhet - En kvalitativ studie om upplevda faktorer som påverkar införandet av sprutbytesverksamhet [County medical officers’ apprehensions of needle exchange programmes: A qualitative study of perceived factors that affect the introduction of needle exchange programmes] . Karolinska Institutet. [Google Scholar]

- Lenke L., Olsson B. (1996). Sweden: Zero tolerance wins the argument? In Dorn N., Jepsen J., Savona E. (Eds.), European drug policies and enforcement (pp. 106–118). Palgrave Macmillan UK. [Google Scholar]

- Lenke L., Olsson B. (2002). Swedish drug policy in the twenty-first century: A policy model going astray. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 582(1), 64–79. [Google Scholar]

- Macneil J., Pauly B. (2010). Impact: A case study examining the closure of a large urban fixed site needle exchange in Canada. Harm Reduction Journal, 7, 11. 10.1186/1477-7517-7-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marotta P. L., McCullagh C. A. (2016). A cross-national analysis of the effects of methadone maintenance and needle and syringe program implementation on incidence rates of HIV in Europe from 1995 to 2011. International Journal on Drug Policy, 32, 3–10. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2016.02.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAdam D., McCarthy J. D., Zald M. N. (Eds.). (1996). Comparative perspectives on social movements: Political opportunities, mobilizing structures, and cultural framings. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nyberg F., Grönbladh L. (2006). Sveriges första metadonprogram firar 40-årsjubileum [Sweden’s first methadone programme celebrates its 40th anniversary] . Uppsala Universitet. http://www.ufold.uu.se/digitalAssets/74/74639_Metadonprogrammet1966-2006.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Olsson B., Blomqvist J., Edman J., Göransson B., Sahlin I., Träskman P., Törnqvist D. (2011). Narkotika: om problem och politik [Drugs: About problems and politics] . Norstedts juridik. [Google Scholar]

- Procyon-Capire. (2009). Åtgärder för att begränsa smittspridning - Sprutbyten och andra smittskyddsåtgärder [Measures to limit spread of infection: Needle exchange and other preventive measures] . Procyon-Capire. [Google Scholar]

- ReActNow. (2009). Mässan Sverige mot narkotika [The Swedish trade fair against drugs] . ReActNow. [Google Scholar]

- Resnick D., Haggblade S., Babu S., Hendriks S. L., Mather D. (2018). The Kaleidoscope Model of policy change: Applications to food security policy in Zambia. World Development, 109, 101–120. 10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.04.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rich J. D., Adashi E. Y. (2015). Ideological anachronism involving needle and syringe exchange programs: Lessons from the Indiana HIV outbreak. JAMA, 314(1), 23–24. 10.1001/jama.2015.6303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richert T. (2012). HIV- och hepatitprevention på insitution [HIV and hepatitis prevention in institutional care] (Vol. 2012:1). Malmö Högskola. [Google Scholar]

- Roe G. (2005). Harm reduction as paradigm: Is better than bad good enough? The origins of harm reduction. Critical Public Health, 15(3), 243–250. 10.1080/09581590500372188 [Google Scholar]

- Sabatier P. A. (1988). An advocacy coalition framework of policy change and the role of policy-oriented learning therein. Policy Sciences, 21(2), 129–168. 10.1007/bf00136406 [Google Scholar]

- Sabatier P. A. (1998). The advocacy coalition framework: Revisions and relevance for Europe. Journal of European Public Policy, 5(1), 98–130. 10.1080/13501768880000051 [Google Scholar]

- Scott N., Stoove M., Kelly S. L., Wilson D. P., Hellard M. E. (2018). Achieving 90-90-90 human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) targets will not be enough to achieve the HIV incidence reduction target in Australia. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 66(7), 1019–1023. 10.1093/cid/cix939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skar H., Axelsson M., Berggren I., Thalme A., Gyllensten K., Liitsola K., Brummer-Korvenkontio H., Kivelä P., Spångberg E., Leitner T., Albert J. (2011). Dynamics of two separate but linked HIV-1 CRF01_AE outbreaks among injection drug users in Stockholm, Sweden, and Helsinki, Finland. Journal of Virology, 85(1), 510–518. 10.1128/JVI.01413-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skretting A. (2014). Governmental conceptions of the drug problem: A review of Norwegian governmental papers 1965–2012. Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 31(5–6), 569–584. 10.2478/nsad-2014-0047 [Google Scholar]

- Socialdepartementet [Ministry of Health and Social Affairs]. (2007). Inrättandet av en samordningsfunktion för regeringens alkohol-, narkotika-, dopnings- och tobaksförebyggande politik [Establishing a coordinating function for the Government’s alcohol, narcotics, doping and tobacco prevention policy] . Socialdepartementet. [Google Scholar]

- Socialstyrelsen [The National Board of Health and Welfare]. (1993). Ang. Försöksverksamheten med utbyte till rena sprutor i Malmö och Lund [Regarding experimental work with clean syringe exchange in Malmö and Lund] . Socialstyrelsen. [Google Scholar]

- Socialstyrelsen [The National Board of Health and Welfare]. (1997). Sprututbytesprojektet i Malmö och Lund - Inspektionsrapport [Needle exchange project in Malmö and Lund: Inspection report] . Socialstyrelsen. [Google Scholar]

- Socialstyrelsen [The National Board of Health and Welfare]. (2001). Socialstyrelsens skrivning med anledning av socialutskottets betänkande 1999/2000: sou10 om vissa narkotikafrågor m.m. [The National Board of Health and Welfare’s report on the Social Affairs Report on certain drug issues, etc.] . Socialstyrelsen. [Google Scholar]

- Socialstyrelsen [The National Board of Health and Welfare]. (2007). Nationella riktlinjer för missbruks- och beroendevård [National guidelines for drug abuse and addiction care] . Socialstyrelsen. [Google Scholar]

- Socialstyrelsen [The National Board of Health and Welfare]. (2009). Sprututbytesverksamheterna i Lund och Malmö - Tillsynsrapport [Needle exchange programmes in Lund and Malmö: Supervision report] . Socialstyrelsen. [Google Scholar]

- Socialstyrelsen [The National Board of Health and Welfare]. (2013). En uppskattning av omfattningen av injektionsmissbruket i Sverige [An estimate of the extent of the injection drug abuse in Sweden] . Socialstyrelsen. [Google Scholar]

- Socialstyrelsen [The National Board of Health and Welfare]. (2015). Nationella riktlinjer för vård och stöd vid missbruk och beroende [National guidelines for care and support in addiction] . Socialstyrelsen. [Google Scholar]

- Socialstyrelsen [The National Board of Health and Welfare]. (SOSFS 2007:2). (2007). Utbyte av sprutor och kanyler till personer som missbrukar narkotika [Exchange of syringes and needles for people who abuse drugs] . Socialstyrelsen. [Google Scholar]

- Statens Folkhälsoinstitut [National Institute of Public Health]. (2008). Narkotikan i Sverige: Metoder för förebyggande arbete [Drugs in Sweden: Prevention methods] . Statens Folkhälsoinstitut. [Google Scholar]

- Statens Folkhälsoinstitut [National Institute of Public Health]. (2010). Folkhälsopolitisk rapport Framtidens folkhälsa – allas ansvar [Public Health Policy Report the future of public health – everyone’s responsibility] . Statens Folkhälsoinstitut. [Google Scholar]

- Statens Offentliga Utredningar [Swedish Government Official Reports]. (SOU 2000:126). (2000). Vägvalet - Den narkotikapolitiska utmaningen [Choice of path: The drug policy challenge] . Parliament Documents. [Google Scholar]

- Statens Offentliga Utredningar [Swedish Government Official Reports]. (SOU 2004:13). (2004). Samhällets insatser mot hiv/STI – att möta förändring [Society’s efforts to combat HIV / STI – meeting change] . Parliament Documents. [Google Scholar]

- Statens Offentliga Utredningar [Swedish Government Official Reports]. (SOU 2008:120). (2008). Bättre kontroll av missbruksmedel - En effektivare narkotika- och dopningslagstiftning m.m. [Better control of drug abuse substances: A more efficient drug and doping legislation, etc.] . Parliament Documents. [Google Scholar]

- Statens Offentliga Utredningar [Swedish Government Official Reports]. (SOU 2011:35). (2011). Bättre insatser vid missbruk och beroende - Individen, kunskapen och ansvaret [Better efforts in drug abuse and addiction: The individual, the knowledge and the responsibility] . Parliament Documents. [Google Scholar]

- Statens Offentliga Utredningar [Swedish Government Official Reports]. (SOU 2011:66). (2011). Sveriges internationella engagemang på narkotikaområdet [Sweden’s international commitment in drug policy] . Parliament Documents. [Google Scholar]

- Stone K., Shirley-Beavan S. (2018). The global state of harm reduction 2018. Harm Reduction International. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensk författningssamling [Swedish Code of Statue]. (SFS 2006:323). (2006). Lag om utbyte av sprutor och kanyler [The syringes and needles exchange act].

- Svensk författningssamling [Swedish Code of Statue]. (SFS 2017:7). (2017). Lag om ändring i lagen (2006:323) om utbyte av sprutor och kanyler [Act amending the Act (2006: 323) on the exchange of syringes and needles].