Abstract

Aims:

Although treatment barriers are different for men and women, research is dominated by males’ and practitioners’ perspectives rather than women’s voices. The purpose of this study in Belgium was to identify and obtain a better understanding of the barriers and facilitators for seeking treatment as experienced by substance (ab)using women themselves.

Methods:

In-depth interviews were conducted with 60 female substance users who utilise(d) outpatient and/or residential treatment services. A content analysis was performed on women’s personal accounts of previous treatment experiences as well as their experiences with services along the continuum of care, resulting in practical implications for the organisation of services.

Results:

Female substance users experience various overlapping – and at times competing – barriers and facilitators when seeking treatment and utilising services. For most women, the threat of losing custody of their children is an essential barrier to treatment, whereas for a significant part of the participants it serves as a motivation to seek help. Also, women report social stigma in private as well as professional contexts as a barrier to treatment. Women further ask for a holistic approach to treatment, which stimulates the healing process of body, mind and spirit, and emphasise the importance of feeling safe in treatment. Participants suggested several changes that could encourage treatment utilisation.

Conclusion:

Our findings demonstrate the need for a gender-sensitive approach within alcohol and drug services that meets the needs of female substance users, as well as gender-sensitivity within prevention and awareness-raising campaigns, reducing the stigma and facilitating knowledge and awareness among women and society.

Keywords: addiction, alcohol and drug treatment, barriers, facilitators, gender, motherhood, stigma, women

Significant gender differences have been reported worldwide regarding the use and abuse of alcohol, prescription drugs and illicit substances (Back et al., 2010; Tang et al., 2012; Van Havere et al., 2009). For example, men and women tend to progress differently from first use to dependence and recovery (Ait-Daoud et al., 2019). Women tend to enter treatment with more severe substance abuse problems, including more physical, psychological, family and socio-economic problems (De Wilde, 2006; Kissin et al., 2014). Research shows that once in treatment women do as well as men, or even better (International Narcotics Control Board, 2017), regarding treatment retention, completion and outcomes. Still, several predictors of poor treatment outcomes (e.g., unemployment, history of victimisation, psychological distress) are more common among women (Greenfield et al., 2007).

Several studies have demonstrated that women-centred treatment programmes can contribute to improved treatment outcomes (Greenfield et al., 2007, 2011; Kissin et al., 2014). However, a recent study in Belgium showed the paucity of alcohol and drug services that are specifically focusing on women or that are explicitly sensitive to the needs of women, further referred to in this study as gender-sensitive treatment, services or approaches (Schamp et al., 2018). Only one in 10 alcohol and drug services in Belgium reported to have a gender-sensitive or gender-specific initiative for women. Moreover, based on their experience and daily practice, programme directors indicated a clear need for gender-sensitive practices.

Abundant evidence suggests that women are underrepresented in alcohol and drug services (Greenfield et al., 2007; Kalema et al., 2017). Treatment demand data show that men clearly outnumber women in alcohol and drug services (“gender gap”), although the male-to-female gender ratio differs between countries and treatment modalities and according to the primary substance of abuse (e.g., relatively more women enter treatment due to problems with alcohol and stimulant substances) (Montanari et al., 2011). Previous research has shown that the underrepresentation of female substance users is particularly high in long-term residential services (e.g., therapeutic communities) (De Wilde, 2006; EMCDDA, 2006). It is further assumed that the number of female problem users in the population does not correspond with the proportion of women in alcohol and drug treatment, especially among women of childbearing age (Montanari et al., 2011).

Lack of appropriate services is a major barrier for treatment engagement among substance abusing women (Elms et al., 2018; Terplan et al., 2015). Treatment entry may be complicated by complex socio-cultural (e.g., social stigma) (McCann & Lubman, 2018) and socio-economic factors (e.g., poverty, educational attainment, social support), as well as by system barriers such as the availability, accessibility and affordability of services, opening hours and absence of childcare (Montanari et al., 2011; Neale et al., 2018). Provider- and clinical-level factors that help or hinder the process of linking female substance users to appropriate services have been documented, primarily outside Europe. For example, primary caregivers often fail to prioritise substance use over other comorbid health concerns, perceive a lack of coordination of care and consider themselves as having insufficient knowledge regarding referral options (Abraham et al., 2017).

Gender has often been regarded as a dichotomous determinant of differences in treatment and population samples, whereas it interacts with many other variables such as age, ethnicity, social status, etc. (Greenfield et al., 2007). Consequently, help-seeking behaviour is profoundly affected by emotional and motivational factors (Kerridge et al., 2017; Probst et al., 2015) and diverse social factors, such as poverty, lack of social and family support, immigration status, and loss of child custody (Gueta, 2017). In this perspective, LeBel and colleagues (2008, p. 136) argued that desistance, and by extension recovery, requires “the will and the ways”, referring to the need for internal motivation for treatment engagement as well as situational opportunities and its interrelationship.

Gender aspects have mainly been studied and discussed in relation to treatment, while this phenomenon is scantly documented in prevention, harm reduction and other alcohol and drug services along the continuum of care (Mrazek & Haggerty, 1994). Moreover, the few studies on drugs and gender that have been carried out in Belgium have focused on very specific populations (e.g., mothers in residential treatment, Vanderplasschen et al., 2016; party drug users, Van Havere et al., 2009). Moreover, research is dominated by practitioners’ perspectives (Fox, 2020) and women’s perceptions regarding the gender gap in alcohol and drug services are poorly documented, as recently confirmed by Lavee (2016). Recent studies emphasise that in order to identify more effective ways to support female users, research must focus on the lived experiences of those women (Noori et al., 2019; Virokannas, 2019).

The current study begins to fill this evidence gap and aims to explore female substance users’ experiences and perspectives on facilitators and barriers for seeking alcohol and drug treatment and utilising services. The scope of the study is not limited to illicit substances, and alcohol and prescription drugs are also included. We studied female substance users’ experiences along the continuum of care including prevention, harm reduction, treatment and continuing care settings. This research was undertaken as part of the GEN-STAR study (GENder-Sensitive Treatment and prevention services for Alcohol and drug useRs), which aimed to assess the availability of and need for gender-sensitive prevention and treatment approaches in Belgium and the obstacles and challenges that are experienced by female substance users in utilising these services (Schamp et al., 2018). Mapping and understanding the facilitators and barriers is critical to better address the unique needs of female substance users.

Methods

Subjects

The sample consisted of 60 female users who were recruited between November 2016 and April 2017 in both the Flemish and the Walloon parts of Belgium. In order to recruit a diverse sample of substance using women in terms of age, socio-economic background, primary substance of abuse and previous treatment experiences, a purposive sampling technique was used (Etikan et al., 2016; Palinkas et al., 2015). Respondents were selected from drug and alcohol services that were identified in an earlier stage of the research as services that implemented either gender-sensitive or gender-specific initiatives. In addition, other services were contacted that provide treatment to female substance users. Both mixed-gender and women-only services were involved in the study, including residential as well as outpatient services along the continuum of care (i.e., methadone centres, psychiatric hospitals, mental healthcare centres and specialised drug services). To find hidden populations of substance using women we aimed to use snowball sampling, but this strategy was not successful since many of the women who participated in the study had cut all ties with their drug using network.

The minimum age of participants was set at 20 years due to ethical considerations. Age stratification (20–30 years, 31–45 years, 45+ years) was applied to select the same proportion of women in each age category. The average age was 41 years. In order to be eligible, participants needed to have had at least one treatment experience and/or experiences with prevention or harm reduction services. An equal proportion of women was recruited in outpatient and residential settings (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of female respondents (n = 60).

| Number of respondents by age category | |

| 20–30 years | 20 |

| 31–45 years | 21 |

| 45+ years | 19 |

| Number of respondents by primary substance | |

| Alcohol | 19 |

| Heroin | 16 |

| Cocaine | 11 |

| Cannabis | 4 |

| Speed | 4 |

| Medication | 3 |

| GHB | 2 |

| Ecstasy | 1 |

| Number of respondents by setting | |

| Outpatient | 28 |

| Residential | 32 |

| Number of respondents with child(ren) | |

| Women with child(ren) | 48 |

| Women with small child(ren) (0–7) | 16 |

| Women with small children (0–7) in residential treatment programme with child(ren) | 7 |

| Women with small children (0–7) in residential treatment programme without children | 3 |

| Women with small children (0–7) in outpatient treatment programme | 6 |

Note. GHB, gamma-Hydroxybutyric acid or γ-Hydroxybutyric acid.

Data collection

A qualitative research approach was applied to explore participants’ experiences and perceptions of facilitators and barriers regarding alcohol and drug treatment. The focus was on describing and understanding the trajectories of these women, the intersections that they encounter, critical life events that they experience along with obstacles and facilitators with regard to entering, staying in or dropping out of treatment. In-depth interviews were used to examine these gendered experiences. After a short socio-demographic assessment, a semi-structured interview was used to make sure every interviewee was asked the same key questions, while providing enough flexibility to explore various topics (Dowling, Lloyd, & Suchet-Pearson, 2016). The findings of the mapping of gender-sensitive initiatives in an earlier stage of the research (Schamp et al., 2018), as well as available literature regarding the topic (Covington, 2015; Elms et al., 2018; Gilchrist et al., 2015; Green, 2006; Greenfield et al., 2007; Grella, 2008) influenced the design of the interview guide. The guide was conceived and especially adapted to question the interaction between agency of female users, the availability of resources and difficulties that women encounter in seeking treatment. The interview contained four major themes: (a) barriers and facilitators experienced by female users and critical events they experienced as (un)helpful, (b) availability or lack of various forms of support and resources, (c) gender-sensitive treatment and personal needs regarding this approach, and (d) personal future perspectives.

The in-depth interviews were performed on site, i.e., the outpatient or residential service for alcohol and drug treatment where the participant was involved in a programme, and conducted in the women’s mother tongue (French or Flemish). Both aspects helped in generating trust among the participants and helping them to feel comfortable and safe during the interview. Interviews were audio-taped and lasted between 40 and 90 minutes. Although participants had already received an information sheet at the moment of recruitment, the researcher went through the information sheet in detail with the participant once again before the start of the interview. Participants then signed an informed consent form that clearly stated participants could end their participation at any time and that the anonymous character of the research was guaranteed. As an incentive, every participant received a voucher for 20 euro.

Data analysis

All full interviews were transcribed verbatim and anonymised. A content analysis was performed on the data emerging from these interviews using the software program NVivo 10. Qualitative content analysis is a research method for the subjective interpretation of the content of text data through the systematic classification process of coding and identifying themes or patterns (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). Hence, key themes and meanings that may have been manifest or latent in the transcribed data were examined. A conventional content analysis was used, since existing theory and research literature on the phenomenon is limited (Kondracki & Wellman, 2002). In order to analyse the interviews and to code them in the same way, each researcher elaborated a coding tree for the analysis based on the data. These two coding trees were then compared and discussed in detail exploring similarities and differences in order to develop a final coding tree, conjoint for both parties. This approach, also described as inductive category development (Mayring, 2000) or text-driven content analysis (Krippendorff, 2013), allowed to identify several major themes and patterns in the data. These themes became the starting point for the content analysis, allowing the researchers to move from the data to a theoretical understanding (Graneheim et al., 2017). During the coding of the interviews, the coding tree was adapted and enlarged by new nodes and sub-nodes. Every change and addition to the coding tree was communicated and discussed to optimise the similarities in the coding process.

Findings

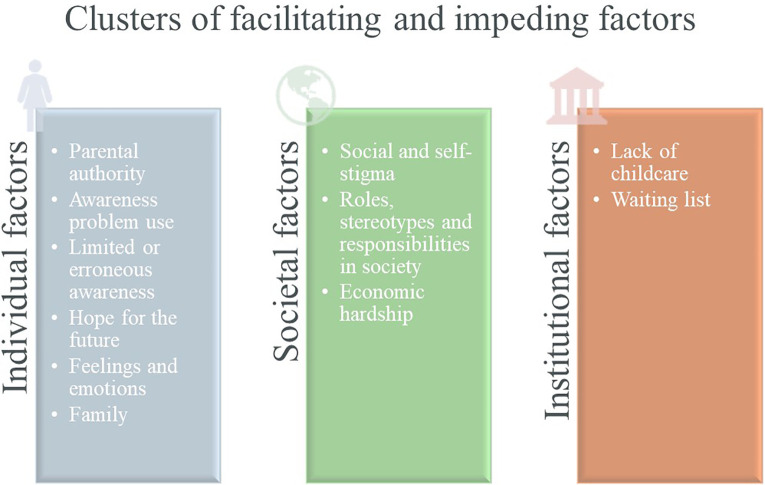

Based on the content analysis, various barriers to treatment were distinguished. Barriers are defined as “events or characteristics of the individual or system that restrain or serve as obstacles to the person receiving healthcare or drug treatment” (Xu, 2007, p. 321). In addition, several factors that facilitate treatment participation for women are described. The data reveal that some facilitating and impeding factors are closely interconnected and/or serve in different ways. Selected quotations using the participants’ own words are used to illustrate the major themes, covering individual, societal and institutional factors (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Identified clusters of facilitating and impeding factors for seeking treatment and service utilisation among female substance users.

Individual factors

Parental authority as a barrier and facilitator for help-seeking behaviour

The main barrier to either outpatient or residential treatment for female users with (young) children, is the fear of losing parental authority. Most women in the study who still have custody of their child(ren) fear that revealing their substance use to social services and/or seeking help for an addiction problem, will lead to losing child custody. Thus, at the junction of being a substance user and the fear of losing child custody, many women are reluctant to contact social services for help, even when they recognise the need for it. Similarly, a few women who are already enrolled in treatment sometimes deliberately avoid being honest about their situation to counsellors. They occasionally omit reporting a relapse or certain events that might negatively influence their parental rights, such as selling drugs or hosting an acquainted substance user.

Do you know what’s hard? The children. That has been a fear of mine for a very long time, you know. If I talk about it they’ll take them away from me. And that’s something you don’t want, of course. Also because I take good care of them. But they’ll never go along with that [substance use]. (39 years, outpatient programme)

In addition, some respondents who had already lost child custody gave up hope and did not see the point of ceasing substance use or seeking treatment anymore. Meanwhile, their substance use was worsening further and prevented help-seeking behaviour even more.

That they were taken from me, you know [stopped me from seeking help]. Then I simply thought “I have nothing left anyway, so I really don’t care anymore what I do or don’t do”. (28 years, residential programme)

Although a number of narratives of female users with small children illustrate the fear of losing parental authority as a treatment barrier, some mothers in the study indicate that the fear of losing child custody as well as recognising the damaging consequences of parental substance use motivates them to seek treatment. Receiving a final warning from social services regarding their parental rights, serves for these mothers as a wake-up call, and motivates them to change their problem substance use and its related problems. These mothers want to do everything they can to make things better, to change their situation, and hence avoid losing child custody. Also, some participants who have already lost parental rights, are encouraged to seek help or enter treatment hoping to regain custody once they have completed the treatment programme.

Yes, but it was already like that the last time…She [daughter] was already gone, you know. They had already taken [daughter] away from me and [son] had also left home. So, I had already lost them both, you know. So, it was basically to get them back, I had to do something, you know. It couldn’t go on like this. (52 years, outpatient programme)

Awareness of problem use often related to health problems

For almost all participants, a prominent barrier to seeking help is the denial or minimisation of the extent of substance use by women themselves. Specifically, reasons for not seeking treatment are the belief that they have their substance use under control, that they can solve their substance use and related problems themselves, or that their substance use is not a problem. In addition, the minimisation or denial of substance use by a member of one’s family, by a friend or by a general practitioner also impedes women’s help-seeking behaviour. On the other hand, nearly all women notice that, once they are better aware of their problem use as well as of its detrimental effects and consequences, it encourages them to seek help and enrol in a treatment programme. Very often the confrontation with an unexpected mental or physical health problem or the sudden deterioration of a dragging health problem is seen as a rock bottom experience and a trigger to gain insight in the extent of their problem.

Because I was always falling lower and lower, I said to myself, I really realised that the next step was death, because, when you wake up in your own vomit, when you do really stupid things that you don’t even remember, and you really want to just curl up and die. […] It was that hit-rock-bottom moment, when I found myself unconscious on the floor, half-naked. […] Besides you’re cutting yourself off from everyone […] You’re completely isolated, if I had died five days could have gone by without anyone noticing. And I told myself that it wasn’t a life. And then we realise the potential we have, that really was the trigger. (28 years, outpatient programme)

Although for some women health problems act as an eye-opener, others report that therapy and counselling after emergency admission as well as the role of close friends and family in response to the incident, are the decisive factors in gaining awareness and initiating treatment.

I fell once and ended up in hospital. There they saw that I had been drinking heavily. And then they talked and talked to me and I came to the realisation that I really needed help. That was actually my saviour, that I fell at home and that I was hurt. And that they took me to hospital. (61 years, outpatient programme)

Limited or erroneous awareness

For some participants, lack of information on available treatment services hinders their treatment entry. These women describe a lack of knowledge about treatment options. Also, some women, especially older women with alcohol problems, report the absence of referral or a late referral to specialised addiction services by general practitioners. However, once the options are known, most women are relieved and make contact with a service. It even serves as a facilitator for seeking help at times of relapse or difficulties.

Ignorance [stopped me from seeking help]. I wouldn’t have known where to turn to. I had no idea that [name of outpatient programme] even existed. Not at all. And, until this very day, I still don’t understand why my GP waited so long before sending me there. He only did so after repeated relapses. (55 years, outpatient programme)

Other women in the study, especially younger female users, recount erroneous and inaccurate ideas about residential treatment services, nourished by their social networks. Their image of residential treatment programmes is often distorted, considering the latter as a “place for insane people” or as extremely restrictive.

It [not seeking treatment] has to do with the fact that they are scared to go into treatment because they don’t know what to expect. That most people think that “they tie you up there”. And I’ve heard that a lot, you know. People hear all kinds of horror stories about it, while none of it is actually true. (28 years, residential programme)

Hope for the future

Many participants express the desire to have a “normal life” in the future, instead of their current life characterised by chaos, disappointment and concerns, as an influence that supports seeking treatment. This normal life is defined as a balanced life in which they own a house or an apartment, maintain a stable relationship, have (a) child(ren), build up a social network with clean friends and family, get a job or go back to school, and/or have the possibility to go travelling. In their vision of the future, these women describe their independence in combination with a healthy, non-abusive relationship with a partner who is not a substance user as a crucial part. Younger women in the study even point out that this is one of the hardest parts.

The idea that, maybe finally, I might be able to start building a normal life again. With all my weaknesses, but that I learn to set boundaries and no longer make myself dependent on a partner. Now, I can finally be a part of life, a normal job with good people around me, a good “foundation”. That is most important, and we’ll take the rest from there, my kids too. (42 years, residential programme)

Feelings and emotions

A minority of women in the study indicate that the pleasant effects of substance use are more attractive and more important than a drug-free life and hinder help-seeking behaviour. Some women specifically describe that the discontinuation of numb feelings and rediscovery of positive feelings and sensations as soon as participants remain sober for a few days induces treatment initiation. Further, experiencing emotions of all kind (i.e., positive and/or negative feelings), but also ambition, pride, dignity and self-worth can support treatment utilisation.

I’m happy with them [treatment centre], because I’m rediscovering a lot of stuff. It’s really like it’s the first time, we’ll say. Not just sexual, but even the tastes, the scents, the senses, just everything. […] All that is coming back. (39 years, outpatient programme)

Family

Participants’ narratives demonstrate that family is an important facilitator for help-seeking behaviour. The despair of family members concerning the female user and the desire for her admission to treatment serves for some women initially as an external motivation, but is in many cases a factor initiating premature drop-out. However, having a family of their own and the ambition to become sober and be there for them is for some women an important motivation to seek treatment. Family may include parents, children, grandparents, siblings or godparents. Many women declare that their children do not deserve a mother who is addicted and who is barely or not at all present in their lives. Also, regaining respect from their parents as well as the desire to make them proud facilitates seeking help and entering treatment.

I went through the same thing as a child. My mum who was an addict. So, I don’t want to give my daughter that same life. She deserves a clean mum. And that’s what I want to give her. (26 years, residential programme)

Societal factors

Social and self-stigma

According to the participants one of the most significant treatment barriers stems from the pervasive social stigma surrounding women and substance use. Throughout the interviews, women discuss how the stigma for female users is manifested in various ways, and very often induces feelings of shame and guilt. Women fear the judgment of others in their environment when opening up about their substance use or disclosing their treatment seeking and service utilisation. This internalised concern of the judgement of one’s environment and the shame about their substance use prompts some women to hide their substance use and avoid seeking treatment. Also, participants describe how the stigma surrounding women with problem substance use is more extensive compared to their male counterparts due to societal expectations and roles. On top of that, women report that motherhood adds an additional layer to stigma.

The other people, what will they say? A feeling of shame. Yes…Guilt and shame. […] Society looks at it differently. For men it’s more accepted. If you are a woman who’s addicted, you are immediately judged. They won’t easily accept that a woman drinks alcohol and has an addiction. (52 years, outpatient programme)

Some women feel guilty about significant others in their environment such as their parents, children, partner or friends. To avoid feeling guilty or feeling like they have disappointed their parents, partner or children, they attempt to ignore and hide their substance use and pursue little to no help for substance-use-related problems. Some women indicate that the pleasant effects of drugs are more attractive and more important than a drug-free life.

However, some participants report that fear of rejection and stigma, sometimes associated with having children, but mostly embedded in the social and family context, facilitates help-seeking behaviour. For these women who are feeling ashamed, humiliated or guilty, family and friends are an impetus to look for help.

Many times I feel guilty. Towards my daughter, because I wasn’t there for her like I should have been. Towards my mother, because I hurt her so much. Towards so many people, you know. Friends that I let down. And some boys that I sometimes really used and often feeling bad about myself, or ashamed. […] All of that played a role [in seeking help], the biggest role even. (27 years, residential programme)

Roles, stereotypes and responsibilities in society

The stories of the study participants reveal that women have an extensive feeling of being responsible for family and children. They consider it as their duty to nurture and care for their children, to take care of a sick or disabled family member, and to take up housekeeping tasks such as doing the laundry and cooking for their partner and family. Furthermore, women report that these responsibilities appear to a larger extent among women than among men and that these are assigned by either women themselves, their partners or by society in a stereotypical way. These women describe their ongoing role as caregivers, despite their substance use, as a barrier. Seeking and engaging in treatment challenges this role, since it may jeopardise these responsibilities.

Well, men have fewer worries than women, because usually you might say that men, […] they’re going to pay less attention to the child, right? […] If they want to get away from the child, well it’s easier for them than for the woman, they don’t have as many responsibilities. So the woman, she has more problems, she has to take care of more things. (30 years, residential programme)

Economic hardship

The women in the study note several external barriers that interfere with their ability to access alcohol and drug services, such as being homeless and lack of money. Some respondents mention episodes of homelessness that aggravated their mental health, substance use and hygiene problems, while others describe how their problem use increased financial issues, compromising access to medical services and substance abuse treatment. Also, transportation to alcohol and drug services is often difficult to find since they are unable to afford it or do not have a support network to drive them.

I was homeless, so an extra difficulty in terms of travelling to a centre. There are many steps to undertake, which are more complicated if you have to do your administration, but there is no money to pay. Especially, if you don’t receive any support or help, like from your parents. (50 years, outpatient programme)

Institutional factors

Lack of childcare

Related to a woman’s role as primary caregiver, almost all female substance users report the lack of outpatient and residential facilities that provide childcare services as an important barrier to substance abuse treatment. The women in the study report that mothers with problem substance use often lack financial resources to afford childcare, nor can they rely on a trustworthy social network to help them take care of their children. They report that most treatment programmes do not allow for parents to bring their children with them, do not provide child care services, nor do they help to arrange for temporary guardianship while the parent is in treatment. Women enrolled in treatment programmes with facilities for children credit this feature as a decisive factor for treatment engagement.

I think there are not enough options for women with an alcohol problem or a drug problem, who have children. I think there isn’t enough shelter available for them. Because I have two children, I had to spend a really long time looking for a facility that could help mothers with children. And that’s when I came here [residential parent–child programme]. (28 years, residential programme)

Waiting list

Some women describe how waiting lists for treatment services may inhibit treatment entry. When seeking help for substance use and related problems, women want immediate help at that point in time, as they have already struggled through a long process. Being confronted with a waiting list hence influences their motivation and hope.

And you sometimes have to wait too, you know. If you call to make an appointment or something, then you’re not always…“Oh well, come by tomorrow, or come next week”. Then the moment has already passed. You need that help when you say “now is the moment”. (30 years, residential programme)

Discussion

This is one of the first studies to explore in depth how a diverse sample of female substance users in Belgium experiences facilitators and barriers to seeking alcohol and drug treatment and utilising services in their care and recovery trajectories. In line with previous research (Gueta, 2017; McCann & Lubman, 2018), our analyses revealed that treatment entry and help-seeking behaviour among female substance users can be complicated by various factors. These factors are dynamic, interrelated and co-constructed, rather than dichotomous, and are shaped in a very particular way for each woman (e.g., the positive or negative impact of parental custody on help-seeking behaviour).

Consistent with research that has found that the treatment gap among women is primarily due to internal barriers to treatment, such as shame and denial of substance use, that are associated with gender violation (Grella, 2008), the present results demonstrate additional internal/personal barriers such as enjoying the pleasant effects of substance use, shame and denial of problem substance use. Further, the importance of experiencing an emotional or physical “hit rock bottom” moment (Grella et al., 2009; Dekkers et al., 2020) is decisive in the awareness of problem use and hence for the initiation of service utilisation. Still, many participants report a lack of awareness of services (Myers et al., 2011) and the absence of referral by general practitioners. In addition, women report that being prejudiced about utilising treatment services, induced by society and co-drug users, hinders their seeking for help.

Parallel to the findings of prior research, this study found that the threat of losing parental authority is the most frequently endorsed barrier to treatment among female substance users with children (Meulewaeter et al., 2019), who attempt to stay under the radar of the social welfare system. However, for some participants it serves as a crucial reason to initiate treatment, either compulsorily or voluntarily. Similarly, participants who have already lost child custody experience this as either a barrier for seeking treatment as they do not have anything left to fight for, or a facilitator for treatment as they want to regain custody. The issue of child custody illustrates a major finding of this study, namely that some decisive factors are multi-layered, dynamic and ambiguous in relation to the meaning-making of the women, that impacts help-seeking behaviour in different ways.

From the perspective of the participants, help-seeking behaviours were profoundly affected not only by individual factors, but also by external factors, which are shaped by structural inequalities, such as poverty and gender-related characteristics of treatment (e.g., lack of childcare), as identified in the literature (Grella, 2008; SAMASHA, 2012). This research supports strong evidence that stigma towards individuals with an alcohol use disorder adversely impacts treatment utilisation (Keyes et al., 2010; Phelan et al., 2000), with social stigma being an even greater barrier to treatment for women than for men (Stringer & Baker, 2018; Neale et al., 2018). The social stigma and judgements on female substance abuse nurture deep feelings of shame, guilt, humiliation and rejection and hinder utilisation of available services. Further, the dominant stereotypes of the roles, responsibilities and expectations of men and women in society are deeply integrated into female users’ lives and constrain women’s ability to seek help. The normative role of being a woman or a mother and the impact of stereotypical role models on treatment are reflected in women’s trajectories and the way they perceive themselves. Gendered roles and higher expectations about women and mothers regarding caring obligations can be detrimental to women (Neale et al., 2014).

Thus, female substance users and mothers experience a number of additional barriers to treatment (Stringer & Baker, 2018), including strong maternal and family responsibilities, lack of childcare while being in treatment, scarce economic resources, lack of support from a social network or partner, and possibly greater social stigma. In addition, the social stigma on substance using mothers is even greater than the social stigma on female users in general and hinders help-seeking behaviour (Stringer & Baker, 2018). Moreover, the intersection of single parenthood and substance use stigma may further decrease the likelihood of seeking treatment.

Finally, several external-systemic factors create additional barriers to service utilisation for female substance users. Consistent with previous literature (van Olphen & Freudenberg, 2004), female users with children report the responsibility for children combined with lack of childcare outside treatment or provided as part of the treatment programme. Also, the tension between the desire for immediate help while being confronted with a waiting list demotivates women.

Strengths of the study include the focus on women’s experiences and voices, the relatively large sample size of 60 participants, and the scope of the research including the entire continuum of care and various substances of abuse. Previous research in Belgium has not consulted female service users to better understand how they experience their care and recovery trajectories. This article is, therefore, important and timely, because it demonstrates the barriers women have to overcome to access treatment on the one hand and facilitating factors for entering treatment on the other hand. Still, some limitations of this study should be noted. First, our data are qualitative; therefore, it is neither possible to assess statistical between-group differences nor to make any empirical generalisations from these findings. Second, although self-report methods are considered appropriate to collect data, they may also threaten the validity of the findings. However, the quality of these data varies with the personal circumstances of the respondents and the conditions and procedures created by the researcher (Del Boca & Noll, 2000). Therefore, participants were guaranteed confidentiality and their engagement was fostered by a financial incentive. Last, although snowball sampling was intended, participants were solely recruited through treatment services. This sample may have specific characteristics affecting help-seeking behaviour. Future research focusing on women who are not currently in treatment might reveal other barriers and facilitators.

Despite these limitations, the findings of the present study have implications for policy and practice. As social stigma on female substance abuse, and even more on motherhood and substance abuse, is one of the most important treatment barriers for women, public health measures are needed to reduce the social stigma on female substance abuse. These measures include campaigns for prevention and awareness raising such as promoting positive experiences of users in recovery and normalising help-seeking behaviour among women and mothers. Second, adequate information on available services for female users and their families must be disseminated among general health and mental health practitioners in order to increase efficient referrals, as well as among female users to improve treatment awareness and reduce erroneous images of treatment centres. Third, as a lack of childcare is one of the main reasons female users avoid seeking help, efforts to involve children or provide childcare in treatment of female users are necessary. In this regard, cooperation with local childcare centres can be explored. Also, in working with mothers and their children the emphasis must be on confidentiality and trust instead of managing punitive and coercive approaches that focus on child custody. Generally, the results of this study call for a more gender-sensitive approach within alcohol and drug services meeting the needs of female substance users. These results also raise important questions for future research, for example, the need for longitudinal prospective studies that track female substance users over time and allow researchers to further identify the factors that induce or hamper treatment utilisation. Future studies on critical factors of service utilisation should attempt to include female users who needed services and did not try to access them, those who attempted to access treatment and were unsuccessful, and those who successfully accessed treatment. Finally, research is needed that evaluates help-seeking behaviour among men and women from the perspective of the perspective of users, since they offer important insights that usually do not become visible through service-, practitioner- or policy-focused research.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the women who participated in the study. The authors thank the staff of the treatment services involved for valuable and elucidative help concerning recruitment of the participants.

Ethics: All procedures performed in the present study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional ethics committee of the Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences at Ghent University.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Belgian Science Policy (DR/00/73) and the Federal Public Service Health, Food Chain Safety and Environment.

ORCID iD: Julie Schamp  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1165-5729

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1165-5729

Contributor Information

Julie Schamp, Ghent University, Belgium.

Sarah Simonis, Université de Liège, Belgium.

Griet Roets, Ghent University, Belgium.

Tina Van Havere, University of Applied Sciences and Arts, Belgium.

Lies Gremeaux, Sciensano, Brussels, Belgium.

Wouter Vanderplasschen, Ghent University, Belgium.

References

- Abraham T. H., Lewis E. T., Cicciare M. A. (2017). Providers’ perspectives on barriers and facilitators to connecting women veterans to alcohol-related care from primary care. Military Medicine, 182, 1888–1894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ait-Daoud N., Blevins D., Khanna S., Sharma S., Holstege C. P., Amin P. (2019). Women and addiction: An update. Medical Clinics of North America, 103(4), 699–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Back S. E., Payne R. L., Simpson A. N., Brady K. T. (2010). Gender and prescription opioids: Findings from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Addictive Behaviors, 35(11), 1001–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covington S. S. (2015). Understanding and applying gender differences in recovery. In O’Neil A. L., Lucas J. (Eds.), Promoting a gender responsive approach to addiction (pp. 309–324). UNICRI Publication nr 104. [Google Scholar]

- Dekkers A., De Ruysscher C., Vanderplasschen W. (2020). Perspectives on addiction recovery: focus groups with individuals in recovery and family members. Addiction Research & Theory. Advance online publication. 10.1080/16066359.2020.1714037 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Del Boca F. K., Noll J. A. (2000). Collecting valid data from community sources. Truth or consequences: the validity of self-report data in health services research on addictions. Addiction, 95(3), 347–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Wilde J. (2006). Gender-specific profile of substance abusing women in therapeutic communities in Europe (Doctoral dissertation). Academia Press Gent. [Google Scholar]

- Dowling R., Lloyd K., Suchet-Pearson S. (2016). Qualitative methods I: Enriching the interview. Progress in Human Geography, 40(5), 679–686. [Google Scholar]

- Elms N., Link K., Newman A., Brogly S. B. (2018). Need for women-centred treatment for substance use disorders: Results from focus group discussions. Harm Reduction Journal, 15(40). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etikan I., Musa S. A., Alkassim R. S. (2016). Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5(1), 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. (EMCDDA). (2006). Annual report 2006. Selected issue 2: A gender perspective on drug use and responding to drug problems. Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. [Google Scholar]

- Fox S. (2020). “[…] you feel there’s nowhere left to go”: The barriers to support among women who experience substance use and domestic abuse in the UK. Advances in Dual Diagnosis, 13(2), 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Gilchrist G., Blazquez A., Rabasa A. P., Coronado M., Colom M., Torrens M. (2015). Sex differences in barriers to accessing substance abuse treatment, a qualitative study. In O’Neil A. L., Lucas J. (Eds.), Promoting a gender responsive approach to addiction (pp. 176–194). UNICRI Publication nr 104. [Google Scholar]

- Graneheim U. H., Lindgren B.-M., Lundman B. (2017). Methodological challenges in qualitative content analysis: A discussion paper. Nurse Education Today, 56, 29–34. 10.1016/j.nedt. 2017.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green C. A. (2006). Gender and use of substance abuse treatment services. Alcohol Research and Health, 29(1), 55–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield S. F., Brooks A. J., Gordon S. M., Green C. A., Kropp F., McHugh R. K., Miele G. M. (2007). Substance abuse treatment entry, retention, and outcome in women: A review of the literature. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 86(1), 1–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield S. F., Rosa C., Putnins B. A., Green C. A., Brooks A. J., Calsyn D. A., Cohen L. R., Erickson S., Gordon S. M., Heynes L., Killeen T., Miele G., Tross S., Winhusen T. (2011). Gender research in the National Institute on Drug Abuse National Treatment Clinical Trials Network: A summary of findings. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 37(5), 301–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield S. F., Trucco E. M., McHugh R. K., Lincoln M., Gallop R. J. (2007). The Women’s Recovery Group Study: A stage I trial of women-focused group therapy for substance use disorders versus mixed-gender group drug counseling. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 90(1), 39–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grella C. E. (2008). From generic to gender-responsive treatment: Changes in social policies, treatment services and outcomes of women in substance abuse treatment. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 40(5), 327–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grella C. E., Greenwell L., Mays V. M., Cochran S. D. (2009). Influence of gender, sexual orientation, and need on treatment utilization for substance use and mental disorders: Findings from the California quality of life survey. BMC Psychiatry, 9(1), 52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gueta K. (2017). A qualitative study of barriers and facilitators in treating drug use among Israeli mothers: An intersectional perspective. Social Science and Medicine, 187, 155–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh H.-F., Shannon S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Narcotics Control Board. (2017). Report of the International Narcotics Control Board for 2016. United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- Kalema D., Vanderplasschen W., Vindevogel S., Baguma P. K., Derluyn I. (2017). Treatment challenges for alcohol service users in Kampala, Uganda. International Journal of Alcohol and Drug Research, 6(1), 27–35. [Google Scholar]

- Kerridge B. T., Mauro P. M., Chou S. P., Saha T. D., Pickering R. P., Fan A. Z., Grant B. F., Hasin D. S. (2017). Predictors of treatment utilization and barriers to treatment utilization among individuals with lifetime cannabis use disorder in the United States. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 181, 223–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes K. M., Hatzenbuehler M. L., McLaughlin K. A., Link B., Olfson M., Grant B. F., Hasin D. S. (2010). Stigma and treatment for alcohol use disorders in the United States. American Journal Epidemiology, 172, 1364–1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kissin W. B., Tang Z. Q., Campbell K. M., Claus R. E., Orwin R. G. (2014). Gender-sensitive substance abuse treatment and arrest outcomes for women. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 46(3), 332–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondracki N. L., Wellman N. S. (2002). Content analysis: Review of methods and their applications in nutrition education. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 34, 224–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff K. (2013). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology (3rd ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Lavee E. (2016). Low-income women’s encounters with social services: Negotiation over power, knowledge and respectability. British Journal of Social Work, 47, 1554–1571. [Google Scholar]

- LeBel T. P., Burnett R., Maruna S., Bushway S. (2008). The “chicken and egg” of subjective and social factors in desistance from crime. European Journal of Criminology, 5(2), 131–159. [Google Scholar]

- Mayring P. (2000). Qualitative content analysis. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 1(2). http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/1089/2385 [Google Scholar]

- McCann T. V., Lubman D. I. (2018). Helpseeking barriers and facilitators for affected family members of a relative with alcohol and other drug misuse: A qualitative study. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 93, 7–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meulewaeter F., De Pauw S., Vanderplasschen W. (2019). Mothering, substance use disorders and intergenerational trauma transmission: an attachment-based perspective. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montanari L., Serafini M., Maffli E., Busch M., Kontogeorgiou K., Kuijpers W., Ouwehand A., Pouloudi M., Simon R., Spyropoulou M., Studnickova B., Gyarmathy V. A. (2011). Gender and regional differences in client characteristics among substance abuse treatment clients in the Europe. Drugs Education Prevention and Policy, 18(1), 24–31. [Google Scholar]

- Mrazek P. J., Haggerty R. J. (1994). Reducing risks for mental disorders: Frontiers for preventive intervention research. National Academy Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers B., Louw J., Pasche S. (2011). Gender differences in barriers to alcohol and other drug treatment in Cape Town, South Africa. African Journal of Psychiatry, 14, 146–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale J., Nettleton S., Pickering L. (2014). Gender sameness and difference in recovery from heroin dependence: A qualitative exploration. International Journal of Drug Policy, 25, 3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale J., Tompkins C.N.E., Marshall A.D., Treloar C., Strang J. (2018). Do women with complex alcohol and other drug use histories want women-only residential treatment. Addiction, 113, 989–997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noori R., Pashaei T., Panjvini D., Khoshravesh S. (2019). Treatment needs of drug users: The perspective of Iranian women. Journal of Substance Use, 24(3), 280–284. 10.1080/14659891.2018.1562573 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Palinkas L. A., Horwitz S. M., Green C. A., Wisdom J. P., Duan N., Hoagwood K. E. (2015). Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services, 42(5), 533–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan J. C., Link B. G., Stueve A., Pescosolido B. A. (2000). Public conceptions of mental illness in 1950 and 1996: What is mental illness and is it to be feared? Journal Health Social Behaviour, 41, 188–207. [Google Scholar]

- Probst C., Manthey J., Martinez A., Rehm J. (2015). Alcohol use disorder severity and reported reasons not to seek treatment: A cross-sectional study in European primary care practices. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 10(1), 32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schamp J., Simonis S., Van Havere T., Gremeaux L., Roets G., Willems S., Vanderplasschen W. (2018). Towards gender-sensitive prevention and treatment for female substance users in Belgium. Final report. Belgian Science Policy. [Google Scholar]

- Stringer K.L., Baker E.H. (2018). Stigma as a barrier to substance abuse treatment among those with unmet need: An analysis of parenthood and marital status. Journal of Family Issues, 39(1), 3–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration. (SAMASHA). (2012). National survey on drug use and health. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang A., Claus R. E., Orwin R. G., Kissin W. B., Arieira C. (2012). Measurement of gender-sensitive treatment for women in mixed-gender substance abuse treatment programs. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 123(1–3), 160–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terplan M., Longinaker N., Appel L. (2015). Women-centered drug treatment services and need in the United States, 2002–2009. American Journal of Public Health, 105(11), 50–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Havere T., Vanderplasschen W., Broekaert E., De Bourdeaudhui I. (2009). The influence of age and gender on party drug use among young adults attending dance events, clubs, and rock festivals in Belgium. Substance Use and Misuse, 44(13), 1899–1915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Olphen J., Freudenberg N. (2004). Harlem service providers’ perceptions of the impact of municipal policies on their clients with substance use problems. Journal of Urban Health, 81(2), 222–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderplasschen W., Van Rompaye E., Littera L., Vandevelde D. (2016). Geen kinderspel: Opvoeding door aan drugs verslaafde ouders na residentiële ouder-kind behandeling [No joke: Parenting by drug dependent parents after mother-child treatment]. Tijdschrift Verslaving, 11(3), 162–175. [Google Scholar]

- Virokannas E. (2020) Treatment Barriers to Social and Health Care Services from the Standpoint of Female Substance Users in Finland. Journal of Social Service Research, 46(4), 484–495. [Google Scholar]

- Xu J., Wang J., Rapp R. C. (2007). The multidimensional structure of internal barriers to substance abuse treatment and its invariance across gender, ethnicity, and age. Journal of Drug Issues, 37(2), 321–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]