Abstract

Study Design:

Studies on the concept of Damage Control Surgery (DCS) in the management of firearm injuries to the oral and maxillofacial region are still scarce, hence the basis for the current study.

Objectives:

The objectives of the current study is to share our experience in the management of maxillofacial gunshot injuries with emphasis on DCS and early definitive surgery.

Methods:

This was a retrospective study of combatant Yemeni patients with maxillofacial injuries who were transferred across the border from Yemen to Najran, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Demographics and etiology of injuries were stored. Paths of entry and exit of the projectiles were also noted. Also recorded were types of gunshot injury and treatment protocols adopted. Data was stored and analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows Version 25 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp).

Results:

A total of 408 victims, all males, were seen during the study period with 173 (42.4%) males sustaining gunshot injuries to the maxillofacial region. Their ages ranged from 21 to 56 years with mean ± SD (27.5 ± 7.6) years. One hundred and twenty-one (70.0%) victims had extraoral bullet entry, while 53 (30.0%) victims had intraoral entry route. Ocular injuries, consisting of 25 (14.5%) cases of ruptured globe and 6 (3.5%) cases of corneal injuries, were the most commonly associated injuries. A total of 78 (45.1%) hemodynamically unstable victims had DCS as the adopted treatment protocol while early definitive surgery was carried out in 47(27.2%) hemodynamically stable victims. ORIF was the treatment modality used for the fractures in 132 (76.3%) of the victims.

Conclusions:

We observed that 42.4% of the war victims sustained gunshot injuries. DCS with ORIF was the main treatment protocol adopted in the management of the hemodynamically unstable patients.

Keywords: gunshot, maxillofacial, damage control surgery, salvage surgery

Introduction

Oral and maxillofacial gunshot injuries pose a significant challenge for reconstructive surgeons who are faced with a mixture of extensive soft tissue and bone defects.1,2 These tissue injuries are triggered during wars and conflicts, aggression, accidents and suicide attempts. Each of them exhibiting particular characteristics in terms of type of firearm used. 3 It has been reported that greater tissue damage is not necessarily caused by high speed projectile with larger kinetic energy. But rather, injury pattern depends on many factors including; kinetic energy, deformation capability, bullet fragmentation and resistance to deformation exhibited by involved tissue. 4 In war and armed conflicts where semi-automatic and automatic weaponry are used, the high speed generated in a projectile can produce bone fragments which will also exit as projectiles in the direction of the bullet’s entrance creating secondary missiles. The projectile itself might become deformed or fragmented, causing a greater damage to the soft tissue. 5 With this pathophysiology, the extent of soft tissue destruction in the immediate post injury may not be totally apparent because there is extensive tissue necrosis, ischemia and potential infection. 1

Past management protocol of ballistic injuries have adopted the delayed definitive reconstruction policy based on the pathophysiology of ballistic injury. However, recent evidences have favored immediate and definitive reconstruction.6,7

Damage Control Strategies which involves Damage Control Resuscitations (DCR) and Damage Control Surgery (DCS) have recently been emphasized.8,9 DCR is the non-surgical technique to reverse the lethal triad of the combination of acidosis, coagulopathy and hypothermia that usually follows hemorrhage from such injuries. DCS involves immediate hemorrhage control, reduction of contamination and temporary wound closure which should be initiated simultaneously with the involvement of all medical personnel in trauma management.10,11 Studies have shown the benefit of combined DCR and DCS in the management of maxillofacial and neck trauma.12,13

The current review is to share our experience in the management of gunshot injuries to the maxillofacial region adopting the DCS and early definitive surgical intervention protocols during the Yemeni civil conflict.

Materials and Methods

This cohort study was carried out between December, 2015 and December, 2019 on combatant Yemeni patients who sustained oral and maxillofacial injuries and were transferred across the border from Yemen to King Khalid Hospital, a tertiary referral center in Najran, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Ethical approval was obtained from the hospital research and ethics committee (IRB) with protocol number H-II-N-081. Inclusion criteria are patients with gunshot injuries as a result of the civil conflict in Yemen. Information such as etiology of injury, age and sex were retrieved from the daily data of the accident and emergency department. Classification of anatomical zones of the neck was based on Monson classification 14 where Zone 1 extends from clavicles to cricoid, zone II from cricoid to angle of mandible, and zone III from angle of mandible to skull base. Entry and exit of the projectile were also noted. Also recorded were types of gunshot injury namely; penetrating, perforating, avulsive and combination and the adopted treatment protocols such as DCS, early definitive surgery, closed reduction and fixation as well as conservative management.

Data was stored and analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows Version 25 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). Results were presented as simple frequencies and descriptive statistics. Pearson Chi-square statistics was used to compare categorical variables. Statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05.

Results

A total of 408 adult maxillofacial trauma patients was seen during the study period with 173 (42.4%) victims having gunshot injuries. All the victims were males. The ages ranged from 21 to 56 years with mean ± SD (27.5 ± 7.6) years. The majority of the patients were between the age 21 and 30 years (140 (80.9%)) with the age group 21-25 years constituting the highest frequency (100 (57.8%)). This however, did not attain any statistically significant difference (χ2 = 5.602, df = 5, p value = 0.347) when age group was compared with entry of the projectile (Table 1). One hundred and twenty-one (70.0%) victims had extraoral entry of the bullet, while 53 (30.0%) victims had entry of the bullets via an intraoral route (Table 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of Mechanisms of Gunshot Injury According to Age Group of the Victims.

| Entry of gunshot injury | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age group (years) | Intraoral (%) | Extraoral (%) | Total (%) |

| 21-25 | 28 (16.2) | 72 (41.6) | 100 (57.8) |

| 26-30 | 12 (6.9) | 28 (16.2) | 40 (23.1) |

| 31-35 | 2 (1.1) | 6 (3.5) | 8 (4.6) |

| 36-40 | 4 (2.3) | 6 (3.5) | 10 (5.8) |

| 41-45 | 5 (2.9) | 3 (1.7) | 8 (4.6) |

| >45 | 1 (0.6) | 6 (3.5) | 7 (4.1) |

| Total | 52 (30.0) | 121 (70.0) | 173 (100.0) |

χ2 = 5.602, df = 5, p value = 0.347.

Perforating injury type was mostly observed in the study population in 99 (57.3%) of the victims (Table 2). Individually, the most affected bones in the maxillofacial region were mandible with 55 (31.8%) cases, orbits 24 (13.9%) cases and maxilla 12 (6.9%) cases respectively while, among the cases affecting multiple bones, combined trauma involving both mandible and maxilla was the majority with 11 (6.3%) of cases. Other maxillofacial bones affected were as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Distribution of Blast Injury Zone According to Injury Type and Maxillofacial Bones Affected.

| Injury Zone | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zone 2 (%) | Zone 3 (%) | Total (%) | Statistics | |

| Injury type | χ2 = 0.757, df = 3, p value = 0.860 | |||

| Penetrating | 4 (2.3) | 42 (24.3) | 46 (26.6) | |

| Perforating | 7 (4.1) | 92 (53.2) | 99 (57.3) | |

| Avulsive | 1 (0.6) | 25 (14.4) | 26 (15.0) | |

| Combination | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.1) | 2 (1.1) | |

| Total | 12 (7.0) | 161 (93.0) | 173 (100.0) | |

| Maxillofacial bones affected | χ2 = 19.285, df = 10, p value = 0.037* | |||

| Mandible | 3 (1.7) | 52 (30.1) | 55 (31.8) | |

| Maxilla | 0 (0.0) | 12 (6.9) | 12 (6.9) | |

| Zygoma | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.7) | 3 (1.7) | |

| Orbit | 0 (0.0) | 24 (13.9) | 24 (13.9) | |

| Antrum | 0 (0.0) | 7 (4.1) | 7 (4.1) | |

| MOZ | 0 (0.0) | 6 (3.5) | 6 (3.5) | |

| MMZ | 0 (0.0) | 4 (2.3) | 4 (2.3) | |

| ZM | 2 (1.1) | 3 (1.7) | 5 (2.9) | |

| MM | 0 (0.0) | 11 (6.3) | 11 (6.3) | |

| CZ | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.1) | 2 (1.1) | |

| None | 7 (4.1) | 37 (21.3) | 44 (25.4) | |

| Total | 12 (7.0) | 161 (93.0) | 173 (100.0) | |

Key: MOZ (Maxilla/Orbit/Zygoma), MMZ (Maxilla/Mandible/Zygoma), ZM(Zygoma/Maxilla), MM (Maxilla/Mandible), CZ (Condyle/Zygoma).

* Statistically significant.

In 78 (45.1%) victims who were hemodynamically unstable, DCS was adopted as the treatment protocol while early definitive surgery was carried out in 47 (27.2%) hemodynamically stable victims. ORIF was the leading treatment modality in 132 (76.3%) of the victims irrespective of whether DCS or early definitive surgery was the treatment protocol adopted (Table 3).

Table 3.

Distribution of Treatment Type According to Surgical Procedure.

| Treatment type | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical procedure | Damage control surgery (%) | Aggressive surgery (%) | None (%) | Total (%) |

| Exploration and pellet removal | 36 (20.8) | 16 (9.3) | 0 (0.0) | 52 (30.1) |

| ORIF | 49 (28.3) | 31 (17.9) | 0 (0.0) | 80 (46.2) |

| Conservative | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 29 (16.8) | 29 (16.8) |

| Closed reduction | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 12 (6.9) | 12 (6.9) |

| Total | 85 (49.1) | 47 (27.2) | 41 (23.7) | 173 (100.0) |

χ2 = 272.560, df = 12, p value = 0.000*.

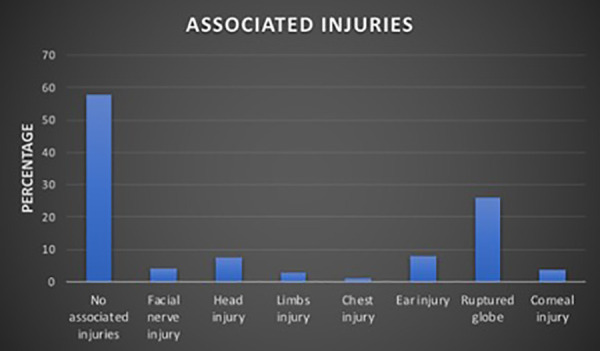

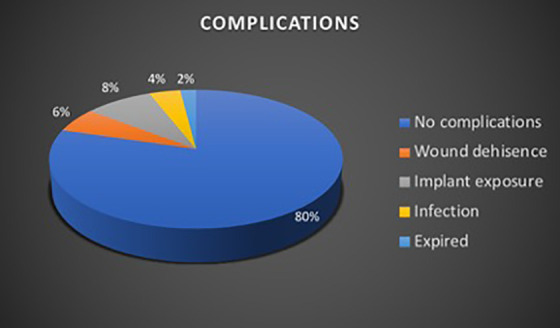

Ocular injuries comprising ruptured globe which makes up of 25 (14.5%) cases and corneal injuries making up of 6 (3.5%) cases, were the most commonly associated injuries. Other associated injury distribution is as shown in Figure 1. In terms of complications, plate exposure 15 (8.0%), wound dehiscence 10 (5.8%) and surgical/injury site infection 7 (4.0%) were observed. Two (1.2%) victims expired as a result of severe head injury (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Bar-chart depicting associated injuries with the gunshot victims.

Figure 2.

Pie-chart showing percentage distribution of complications with the gunshot victims.

Discussions

Our observed epidemiology is consistent with the literature where young adults between ages of 21 and 30 years were the main victims of the conflict. Similarly, only males were seen as victims of the conflict. Studies have shown that males constitute greater than 80% of the gunshot injury patient population. 15 In most war/conflict situations, bomb blast injuries have been reported to be higher than gunshot injuries because of advances in more bomb blast weapon system that can cause more extensive damage. 16 Our current study showed a lower gunshot injury victims (42.4%) as compared with bomb blast injuries that was observed to be 57.6%. Similar lower incidence of gunshot injuries have also been reported in the literature.17,18

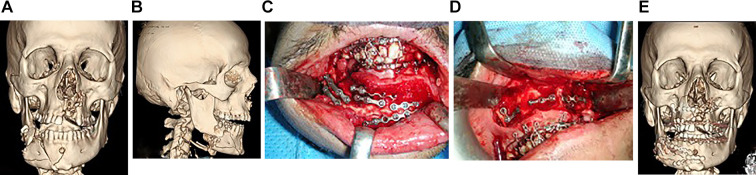

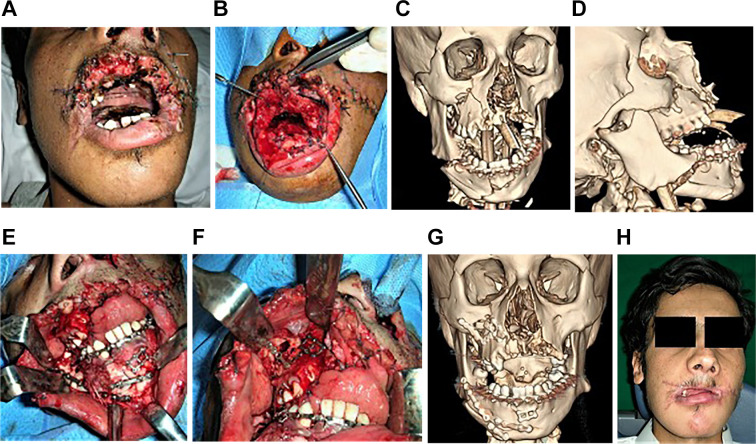

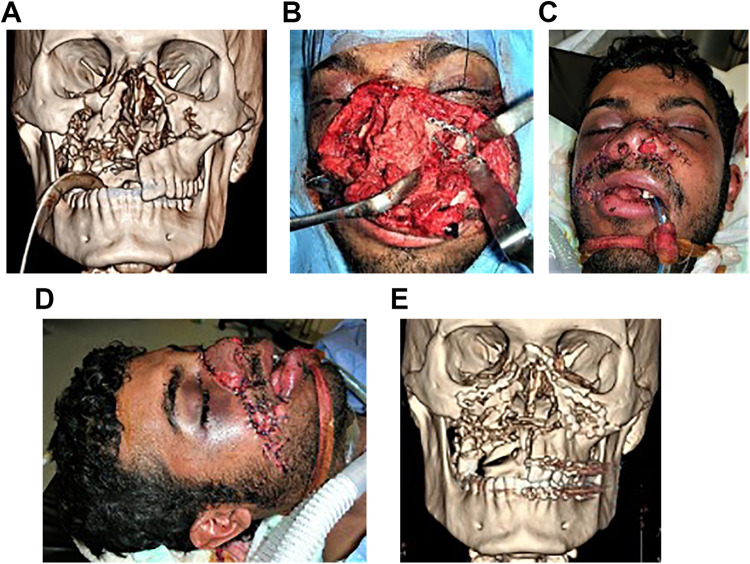

The mandible, which is the only mobile bone in the craniofacial complex and most prominent after zygoma, 19 was observed to be most commonly affected in the current study, accounting for 55 (31.8%) of the victims. The mandible is therefore more prone to direct forces and injuries because of lack of protection and its large surface area, making it easily exposed to injury.20–22 Comminution of hard tissues (Figures 3A-E) and avulsion of both hard and soft tissues (Figures 4A-H), which are common with firearms injuries, were also observed in this group of patients. Midface injuries, involving the maxilla, zygoma, orbit and NOE, were the second most affected after the mandible (Figures 5A-E). This is also in agreement with reports in the literature 23 but contrary to other studies from war data which have reported the midface to be the commonest zone of injuries.24,25

Figure 3.

A. Anteroposterior view of 3-D CT Scan of a gunshot victim with comminuted fracture of left anterior maxilla (entry point of bullet), right maxilla and comminuted fracture of symphysis, right body of mandible (exit point of bullet). B. Lateral view of 3-D CT scan of the same patient showing comminuted fracture of right body and angle of mandible with displaced proximal segment. C. Intraoperative photo of patient with gunshot injuries showing ORIF of comminuted fractures of mandible. D. Intraoperative photograph showing ORIF of fractured right maxilla. E. Anteroposterior view of postoperative 3-D Scan showing ORIF of the comminuted fractures of maxilla and mandible.

Figure 4.

A. Photograph of a gunshot victim showing a substantial part of the upper lip shaved off by the bullet and transpalatal wire used to stabilize the maxillary fracture. B. Photograph of the same patient showing an extensive horizontal split of the tongue. Note the skin sutures used initially to repair facial laceration during stage 2 of the damage control surgery (DCS) for the patient. C. Oblique view of a preoperative 3-D CT Scan of the patient showing comminuted fractures of symphysis, right body and angle of mandible, comminuted fracture of right maxilla with missing part of anterior and left maxilla. D. Lateral view of 3-D CT scan showing displaced fracture of right angle of mandible. Note the presence of oro-tracheal intubation. E. Intraoperative photograph showing ORIF of the fractures of the mandible during stage 4 of DCS. F. Intraoperative photograph showing ORIF of the fractures of the maxilla. G. Anteroposterior view of postoperative 3-D CT scan showing ORIF of the fractures of mandible and maxilla. H. Photograph of the patient take 4 weeks postoperatively showing healed facial lacerations and deformation of upper lip which will require correction at a later stage.

Figure 5.

A. Anteroposterior view of 3-D CT scan of a patient with comminuted fracture of maxilla and nose following gunshot injury to the midface. B. Intraoperative photo of the patient showing extensive facial laceration with degloved nose and ORIF of the maxillary fracture during early definitive surgery of his injuries. C and D. Postoperative photos of the patient showing satisfactory repair of facial lacerations after ORIF of the maxillary and nasal fractures. E. Postoperative anteroposterior 3-D CT scan showing ORIF of the maxillary and nasal fractures.

Many maxillofacial firearm injuries can be treated early despite the fact that these wounds are considered contaminated. Numerous researchers have expressed contrary opinion to traditional protocol of delaying surgical intervention and have proposed a comprehensive early primary surgical treatment.26–28 The group also reported that delaying the procedure increased the incidence of wound contracture and fibrosis which resulted in extensive structural and functional disfigurement. Advocates of delayed reconstruction have typically argued that the delay period will reduce infection rate, decrease the amount of necrotic tissues, lead to resolution of edema, and decrease inflammation for proper tissue assessment. 29 For the immediate reconstruction group, they have reported that by immediately reducing or eliminating local dead space, there is improved immunoreactivity, delivery of more nutrients necessary for healing to progress, tissues are more elastic and pliable, and finally, there are fewer and less complex secondary procedures.27,28

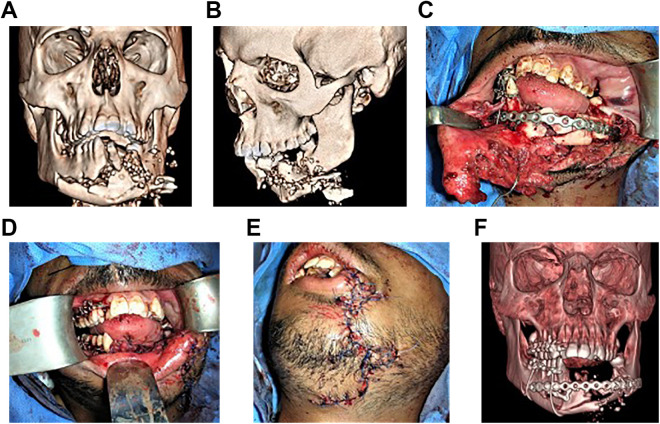

DCS, also referred to as salvage surgery, has been in the frontline in the management of trauma patients especially when they are not clinically fit for a prolonged surgery required for extensive soft and hard tissue reconstruction.8,11 We reported that 78 (45.1%) victims were treated with the DCS and 47 (27.2%) by immediate definitive repair with ORIF. In the victims who were too hemodynamically unstable to withstand prolonged surgery for definitive reconstruction, we applied DCS by initial exploration of soft tissue wounds to control bleeding and later when the patients’ condition improved, ORIF of bony fractures. The ORIF was carried out by initially picking viable bone pieces and aligning them with the use of wires, microplates and/or use of flexible 2.0 mm miniplates and later reinforcing the aligned segments with rigid 2.0 mm miniplates, 2.4 mm miniplates or sometimes, 3 mm reconstruction plates (Figures 6A-F). Literature search has revealed only 2 reported studies that specifically explained the application of DCS in maxillofacial surgery but unfortunately they did not discuss which procedures should be used specifically for the maxillofacial trauma.30,31 From the authors’ point of view, the idea of DCS may operate as a compromise between delayed and early definitive management. In the current study, hemodynamically stable victims were treated by early definitive management with ORIF and soft tissue repair. This approach is consistent with the early surgical intervention of maxillofacial ballistic injuries reported in the literature. Recent evidences have shown that in the maxillofacial region, many ballistic injuries may be treated early with improved re-establishment of the facial contours, lesser morbidity, early return to function, shorter hospitalization, and reduced need for secondary procedures.6,7,26,32

Figure 6.

A. Anteroposterior view of preoperative 3-D CT scan showing comminuted fracture of mandible resulting from gunshot injuries. B. Lateral view of preoperative 3-D CT scan showing comminuted fracture of mandible. C. Intraoperative photo showing alignment of comminuted fractures of mandible with bony fragments aligned and fixed with wires and reinforced with reconstruction plate. Note the extensive laceration of the lower lip extending the chin. D. Intraoperative photo showing closure of the wound after ORIF of the fractures. E. Intraoperative photo showing closure of the wound involving the lower lip, mental and submental region after ORIF of the fractures. F. Anteroposterior view of postoperative 3-D CT scan showing ORIF of the comminuted fractures of mandible with some bone fragments supported with circum-mandibular wires.

Ocular trauma was observed as the mostly commonly associated injury in the current study which is in tandem with the literature.25,33,34 We reported 25 (14.5%) victims with ruptured globe which required enucleation and evisceration, 6 (3.5%) had corneal lacerations that were sutured and abrasions that were managed with topical dressings by the ophthalmologists. Furthermore, these patients were under constant reviews by the ophthalmologists in the eye clinic. Because of the high incidence of ocular injuries in ballistic missile trauma to the craniofacial complex, the United States of America and United Kingdom military forces have resorted to the use of low- and medium-impact ballistic sunglasses and goggles. 35 Other associated injuries in our study were attended to in a multi-specialty management protocol for war victims received by our hospital. This include psychologists and psychiatrists for the management of anxiety and depression, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), low self-esteem and low quality of life (QoL) that are usually associated with such injuries. Secondary procedures planned for reconstruction in these patients were suspended because of the high turnover rate of patients for emergency surgery during the conflict. Inability to rehabilitate them to full oral function with dental treatments including implant-retained prosthesis was a major treatment gap observed in these group of patients. Nonetheless, appropriate and detailed medical report were provided to all patients returning to their country for follow-up.

Conclusions

Firearms injuries will continue to be a public health challenge in the current world situation. From the current study, all the victims of gunshot injuries in the ongoing Yemen conflict were males with the majority in the 21-30 years age group. Fifty-three (30.0%) victims had intraoral entry of the bullets which is suggestive of sniper tactics while others were victims from battle field gunshot injuries. The majority of the victims were managed by DCS which involved initial exploration to control soft tissue bleeding as well as temporary fixation of bone fragments followed later by definitive ORIF of bony fractures. Ocular trauma was the most observed associated injury. Multi-disciplinary management protocol was adopted for the victims including psychologists and psychiatrists for the management of anxiety and depression, post-traumatic stress disorder low self-esteem and low quality of life.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Ramat O. Braimah, FWACS  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7608-1965

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7608-1965

References

- 1.Kaufman Y, Cole P, Hollier LH, Jr. Facial Gunshot wounds: trends in management. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2009;2(2):85–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doctor VS, Farwell DG. Gunshot wounds to the head and neck. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;15(4):213–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stefanopoulos P, Filippakis O, Soupiou V, Pazarakiotis C. Wound ballistics of firearm-related injuries—Part 1: Missile characteristics and mechanism of soft tissue wounding. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;43(12):1445–1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Powers DB, Robertson OB. Ten common myths of ballistic injuries. Oral Maxillofacial. Surg Clin North Am. 2005;17(3):251–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stefanopoulos PO, Soupiou V, Pazarakiotis C, Filippakis V. Wound ballistics of firearm-related injuries—Part 2: Missile characteristics and mechanism of soft tissue wounding. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;44(1):67–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Motamedi MHK. Primary management of maxillofacial hard and soft tissue gunshot and shrapnel injuries. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61(12):1390–1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Motamedi MH. Primary treatment of penetrating injuries to the face. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65(6):1215–1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lamb CM, MacGoey P, Navarro AP, Brooks AJ. Damage control surgery in the era of damage control resuscitation. Br J Anaesth 2014;113(2):242–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duchesne JC, McSwain NE, Jr, Cotton BA, et al. Damage control resuscitation: the newface of damage control. J Trauma 2010;69(4):976–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rotondo MF, Zonies DH. The damage control sequence and underlying logic. Surg Clin North Am. 1997;77(4):(761–777). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krausz AA, Krausz MM, Picetti E. Maxillofacial and neck trauma: a damage control approach. World J Emerg Surg. 2015;10:31, DOI 10.1186/s13017-015-0022-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Firoozmand E, Velmahos GC. Extending damage-control principles to the neck. J Trauma. 2000;48(3):541–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rezende-Neto J, Marques AC, Guedes LJ, Teixeira LC. Damage control principles applied to penetrating neck and mandibular injury. J Trauma. 2008;64(4):1142–1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Monson DO, Saletta JD, Freeark RJ. Carotid vertebral trauma. J Trauma. 1969;9(12):987–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hollier L, Grantcharova EP, Kattash M. Facial gunshot wounds: a 4-year experience. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;59(3):277–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arasa M, Altas M, Yılmaza A, et al. Being a neighbor to Syria: a retrospective analysis of patients brought to our clinic for cranial gunshot wounds in the Syrian civil war. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2014;125(2014):222–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mabry R, Holcomb JB, Baker AM, et al. United States Army Rangers in Somalia: an analysis of combat casualties on an urban battlefield. J Trauma. 2000;49(3):515–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lakstein D, Blumenfeld A. Israeli army casualties in the second Palestinian uprising. Mil Med. 2005;170(5):427–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Anee AM, Al-Quisi AF, Al-Jumaily HA. Mandibular war injuries caused by bullets and shell fragments: a comparative study. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2018;22(3):303–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin FY, Wu CI, Cheng HT. Mandibular fracture patterns at a medical center in Central Taiwan. A 3-year epidemiological review. Medicine 2017;96(51):1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lew TA, Walker JA, Wenke JC, Blackbourne LH, Hale RG. Characterization of craniomaxillofacial battle injuries sustained by United States service members in the current conflicts of Iraq and Afghanistan. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;68(1):3–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Breeze J, Gibbons AJ, Shieff C, et al. Combat-related craniofacial and cervical injuries: a 5 year review from the British military. J Trauma. 2011;71(1):108–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abramowicz S, Allareddy V, Rampa S, et al. Facial fractures in patients with firearm injuries: profile and outcomes. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017;75(10):2170–2176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keller MW, Han PP, Galarneau MR, Gaball CW. Characteristics of maxillofacial injuries and safety of in-theater facial fracture repair in severe combat trauma. Mil Med. 2015;180(3):315–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lanigan A, Lindsey B, Maturo S, Brennan J, Laury A. The Joint Facial and Invasive Neck Trauma (J-FAINT) Project, Iraq and Afghanistan: 2011-2016. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;157(4):602–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mclean JN, Moore CE, Yellin SA. Gunshot wounds to the face—acute management. Facial Plast Surg. 2005;21(3):191–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gruss JS, Antonyshyn O, Phillips JH. Early definitive bone and soft-tissue reconstruction of major gunshot wounds of the face. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;87(30):436–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vayvada H, Menderes A, Yilmaz M, Mola F, Kzlkaya A, Atabey A. Management of close range, high energy shotgun and rifle wounds to the face. J Craniofac Surg. 2005;16(5):794–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ueeck BA. Penetrating injuries to the face: Delayed versus primary treatment-considerations for delayed treatment. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65(6):1209–1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gibbons AJ, Breeze A. The face of war: the initial management of modern battlefield ballistic facial injuries. J Mil Veterans Health. 2011;19(2):15–18. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gibbons AJ, Mackenzie N. Lessons learned in oral and maxillofacial surgery from British military deployments in Afghanistan. J R Army Med Corps. 2010;156(2):113–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baig MA. Current trends in the management of maxillofacial trauma. Ann R Australas Coll Dent Surg. 2002;16:123–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thach A, Johnson AJ, Carrol RB, et al. Severe eye injuries in the war in Iraq, 2003-2005. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(2):377–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cockerham GC, Rice TA, Hewes EH, et al. Closed-eye ocular injuries in the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(22):2172–2173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Breeze J, Horsfall I, Hepper A, Clasper J. Face, neck, and eye protection: adapting body armour to counter the changing patterns of injuries on the battle field. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;49(8):602–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]