Abstract

N6-methyladenosine (m6A), as the most pervasive internal modification of eukaryotic mRNA, plays a crucial role in various cancers, but its role in multiple myeloma (MM) pathogenesis has not yet been investigated. In this study, we revealed significantly decreased m6A methylation in plasma cells (PCs) from MM patients and showed that the abnormal m6A level resulted mainly from upregulation of the demethylase fat mass and obesity-associated protein (FTO). Gain- and loss-of-function studies demonstrated that FTO plays a tumor-promoting and pro-metastatic role in MM. Combined m6A and RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) and subsequent validation and functional studies identified heat shock factor 1 (HSF1) as a functional target of FTO-mediated m6A modification. FTO significantly promotes MM cell proliferation, migration, and invasion by targeting HSF1/HSPs in a YTHDF2-dependent manner. FTO inhibition, especially when combined with bortezomib (BTZ) treatment, synergistically inhibited myeloma bone tumor formation and extramedullary spread in NOD-Prkdcem26Cd52il2rgem26Cd22/Nju (NCG) mice. We demonstrated the functional importance of m6A demethylase FTO in MM progression, especially in promoting extramedullary myeloma (EMM) formation, and proposed the FTO-HSF1/HSP axis as a potential novel therapeutic target in MM.

Keywords: multiple myeloma, m6A methylation, FTO, HSF1, metastasis

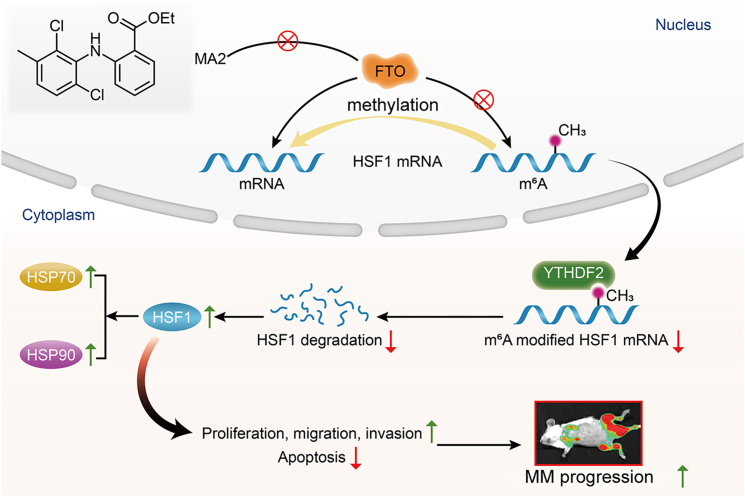

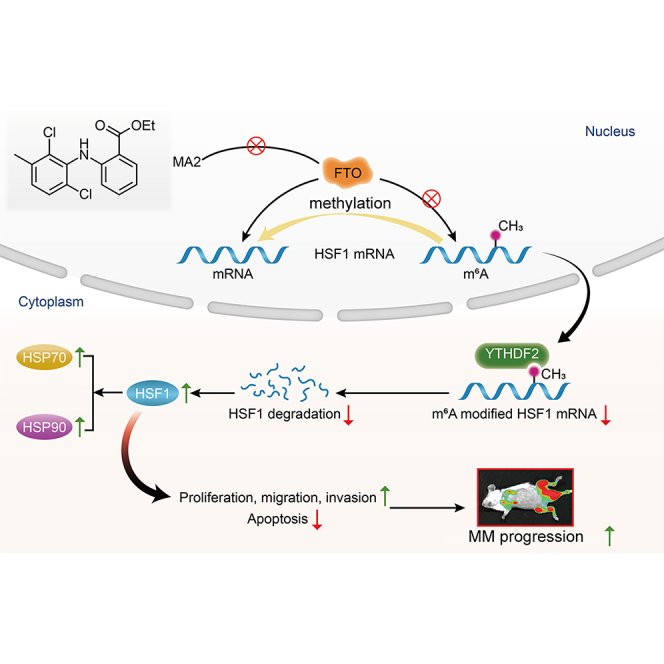

Graphical abstract

The role of m6A in MM pathogenesis has not yet been investigated. Hu and colleagues demonstrate that aberrant upregulation of m6A demethylase FTO enhances the stability of HSF1 by YTHDF2-mediated mRNA decay, thereby promoting MM progression, especially in promoting EMM formation.

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is the second most common hematological malignancy that develops as a consequence of a multistep transformation process.1 Despite the development of novel therapeutic agents, MM remains a largely incurable and fatal disease.2,3 In recent decades, tremendous evidence has indicated that both genetic aberrations, including mutations in oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes, and epigenetic mechanisms, including DNA and histone methylation, abnormal microRNA (miRNA), and other noncoding RNA expression, are involved in the pathogenesis of MM.4,5 miRNAs are well known to play a central role in MM pathogenesis and drug resistance by destroying mRNA or inhibiting its translation.6 Several studies in recent years assessed epigenetic inhibitors in clinical trials of MM, showing that drugs targeting epigenetic modifiers (HDAC or EZH2) can sensitize MM cells to antimyeloma treatment.7,8 Moreover, miRNAs have been reported to reciprocally impact epigenetic modulators in cancers, highlighting the existence of a regulatory circuit between these two regulatory systems.9, 10, 11, 12 A recent study indicated that the epigenetic miRNA axis could provide potential therapeutic targets in MM patients, especially for those with poor prognosis.10 Collectively, epigenetic deregulation is now considered a major driving force of MM carcinogenesis and development.

N6-methyladenosine (m6A), methylation at the N6 position of adenosine, is a recently emerging epigenetic molecular mechanism. Recognized by different reader proteins, m6A methylation can regulates almost all steps of RNA metabolism, including stability, decay, splicing, nuclear export, and translation.13,14 Among hundreds of posttranscriptional chemical modifications, m6A is the most abundant and pervasive internal modification of eukaryotic mRNAs and noncoding RNAs.15, 16, 17 Analogous to DNA methylation, m6A modification is also reversible and is regulated by three groups of molecules commonly referred to as m6A writers, erasers, and readers. m6A writers, consisting of several methyltransferases such as methyltransferase-like 3 (METTL3), METTL14, and Wilms tumor 1-associated protein (WTAP), catalyze m6A formation. Fat mass and obesity-associated protein (FTO) and ALKBH5, two m6A demethylases (erasers), facilitate m6A removal.13,18 In addition, the biological effects of m6A modification require the recognition of m6A marks by m6A reader proteins that contain a YT521-B homology (YTH) domain or, alternatively, by eukaryotic initiation factor 3 (eIF3).18 YTHDF2 is the first identified and the most studied m6A reader protein that influences mRNA stability.19 Recent studies have suggested that m6A RNA methylation plays a crucial role in highly conserved bioprocesses, such as stem cell renewal, tissue development, circadian clock regulation, and the heat shock response (HSR).20, 21, 22 Subsequently, compelling evidence indicates that m6A modulators have important effects on tumor initiation, invasion, and metastasis in several cancers and function as either oncogenes or tumor suppressor genes.13,23

The first evidence of the biological impacts of m6A regulatory genes on hematological malignancy was found in a study of the m6A demethylase FTO. In that work, FTO was reported to play a tumor-promoting role in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cell differentiation, enhance leukemogenesis, and attenuate the efficacy of all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) in AML cells by negatively regulating ASB2 and RARA by decreasing their degree of m6A modification.24 Additionally, FTO has been shown to act as a crucial oncogene in glioblastoma,25 gastric cancer,26 breast cancer,27 and melanoma,28 likely by regulating cancer-specific targets. Most importantly, epidemiological studies have demonstrated that people with single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in FTO or with obesity/overweight tend to have a higher risk of developing various cancers,29, 30, 31 including MM. However, the role of FTO in MM occurrence and development has not yet been investigated.

In the present work, we revealed significantly decreased m6A methylation in MM patients, evaluated the role of FTO in MM pathogenesis and progression, and investigated the underlying molecular mechanism. Our findings provide the persuasive evidence that upregulated FTO is associated with the development and progression of MM, especially with extramedullary spread. FTO promoted the proliferation, migration, and invasion of MM in vitro and in vivo through m6A- and YTHDF2-dependent HSF1/HSP axis activation. We proposed that FTO may act as a novel therapeutic target in MM, especially in extramedullary myeloma (EMM).

Results

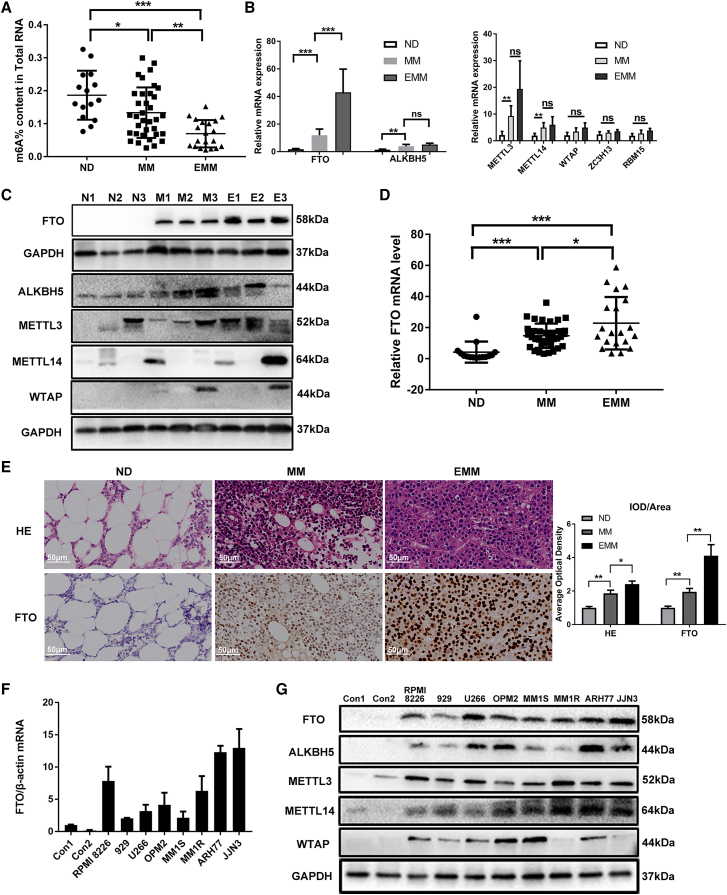

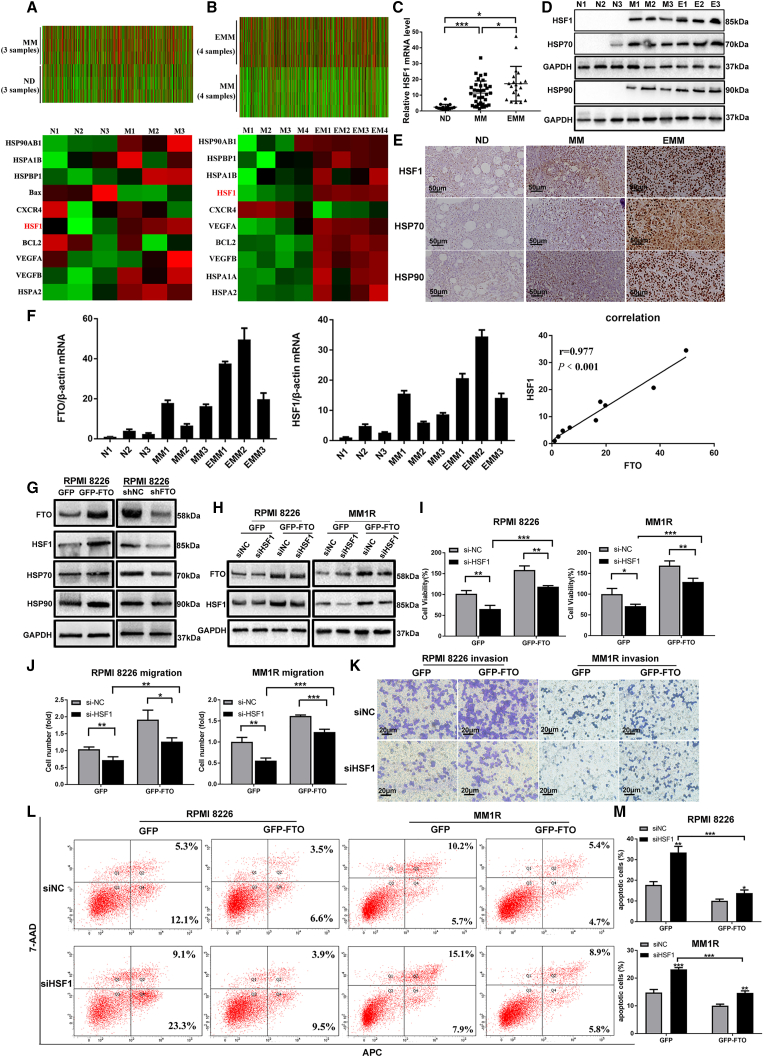

The FTO m6A demethylase is highly expressed in MM and EMM samples

Compared with healthy donors, FTO expression was at a higher level in MM patients by transcriptome array analysis (Figure S1A). Using a colorimetric assay, we evaluated the m6A level in MM patients (n = 35) and EMM patients (n = 20). Decreased RNA m6A levels were detected in primary plasma cells (PCs) from MM patients compared with those from normal donors (NDs) (n = 15), and a further decrease in the m6A level was found in primary PCs from EMM patients (Figure 1A). In addition, there was no significant difference between the m6A level in the bone marrow (BM) of EMM patients and that in MM patients (data not shown). To investigate the key regulator of m6A methylation in MM, we systematically analyzed the levels of the seven major modifying enzymes in eight sets of primary PCs from NDs, MM patients, and EMM patients and identified that FTO, the core m6A demethylase, was significantly upregulated in PCs from patients with MM compared with NDs and was further upregulated in PCs from EMM patients (Figures 1B and 1C). Next, we validated the findings in an expanded sample cohort and consistently found that the expression of FTO was significantly elevated in primary PCs from MM patients, especially in EMM patients (Figure 1D). These results were further confirmed by IHC staining of the FTO protein in BM biopsy of MM patients and soft tissues of EMM patients (Figure 1E). Additionally, upregulation of FTO was found in human myeloma cell lines (HMCLs) at both the mRNA and protein levels, especially in ARH77 and JJN3 cells (two kinds of PC leukemia (PCL) cell lines) (Figures 1F and 1G). However, other m6A-associated proteins showed no increasing or decreasing trend consistent with the m6A level change in NDs, MM, and EMM samples (Figures 1B and 1C); these proteins also showed no progressive trend in the PCs of NDs, MM cell lines or PCL cell lines (Figure 1G). These results demonstrated that FTO was upregulated in MM cells, especially in those from EMM samples.

Figure 1.

FTO is upregulated in MM and EMM

(A) m6A mRNA levels in NDs (n = 15), MM patients (n = 35), and EMM patients (n = 20) were measured by an m6A ELISA. (B) Expression of m6A regulatory enzymes was measured by qPCR in CD138 + cells from NDs, MM patients, and EMM patients. (C) Western blot analysis of major m6A enzymes in CD138 + cells isolated from MM patients or EMM patients. N indicates NDs, M indicates MM patients, and E indicates EMM patients. (D) FTO upregulation was further validated in an expanded set of samples from 15 NDs, 35 MM patients, and 20 EMM patients by qPCR. (E) Distribution of primary PCs in samples of different groups was assessed by H&E staining; the FTO protein level was assessed by immunohistochemistry. Average optical density (AOD) of different groups is presented in the histogram on the right. (F and G) qPCR analysis of FTO (F) and Western blot analysis of m6A regulatory enzymes (G) in primary PCs from NDs and in MM cell lines. ∗P<0.05, ∗∗P<0.01, ∗∗∗P<0.001, ns: no significance.

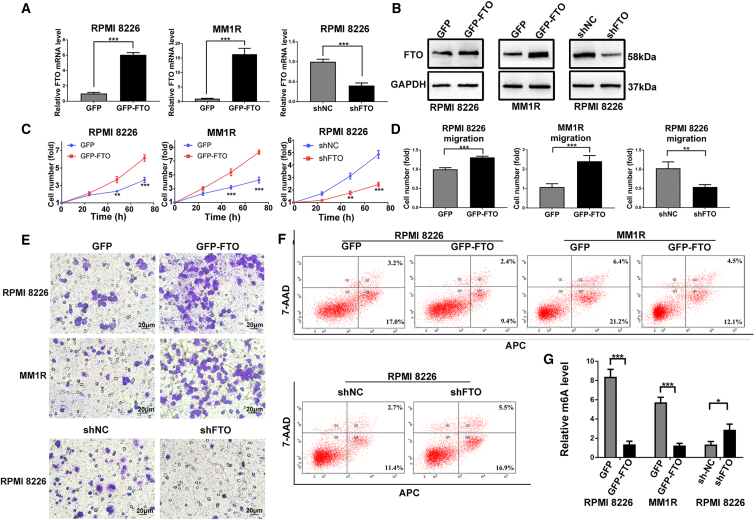

FTO promotes the proliferation, migration, and invasion and inhibits the apoptosis of MM cells in vitro

To explore the functional roles of FTO in MM cells, we established stable FTO-KD and FTO-OE in two common MM cell lines, RPMI8226 and MM1R, using lentiviral transduction (Figures 2A and 2B). We found that forced expression of FTO in MM cells promoted cell growth/proliferation, migration, and invasion, while decreasing apoptosis and the global m6A RNA modification level (Figures 2C–2G and S1G). In contrast, FTO knockdown (FTO-KD) showed the opposite effects in MM cells (Figures 2C–2G and S1G). Similar effects were observed when the expression of FTO was silenced by siRNAs (Figures S1B–S1F).

Figure 2.

FTO promotes MM cell proliferation and migration/invasion and inhibits apoptosis in vitro

(A and B) Stable FTO-OE and FTO-KD in RPMI8226 and MM1R cells by lentiviral sequencing. The transfection efficiency was confirmed at both the mRNA (A) and protein levels (B). (C) Cell proliferation assay in RPMI8226 and MM1R cells with GFP (vector control), GFP-FTO (FTO-OE), shNC (negative control), or shFTO (FTO-KD). (D) Cell migration assay analysis with cells as in (C). (E) Cell invasion assay with cells as in (C). (F) Apoptosis analysis in cells used in (C). (G) The global m6A level was detected in the cells used in (C). ∗P<0.05; ∗∗P<0.01; ∗∗∗P<0.001.

To further verify the oncogenic function of FTO in MM, we used MA2, a selective chemical inhibitor of FTO32 (Figure 3A). As shown in Figure 3B, an obvious growth inhibitory effect of MA2 was detected in MM cells treated with doses of 60–100 μM (P < 0.001). In addition, MA2 suppressed the proliferation and migration of RPMI8226 and MM1R cells at a dose of 60 μM (Figures 3C and 3D), while increasing the apoptosis of these cells (Figures 3E and S1H). Furthermore, to assess the influence of MA2 on the effects of bortezomib (BTZ), a first-line chemotherapeutic agent for MM, we treated MM cells with a combination of MA2 (60 μM) and BTZ (3 nM for RPMI8226 cells and 1.5 nM for MM1R cells for 48 h. The results showed that in the presence of BTZ, MA2 further decreased the proliferation, migration, and invasion but increased the apoptosis of MM cells (Figures 3C–3E and S1H), demonstrating that FTO inhibition potentially augments the efficiency of BTZ in MM cells in vitro. Importantly, MA2 treatment significantly increased the m6A levels in MM cells (Figure 3F).

Figure 3.

The FTO inhibitor MA2 suppresses MM cell growth and migration and increases apoptosis in vitro

(A) Western blot analysis was used to assess the inhibitory effect of MA2 on FTO. (B) Cell viability analysis of MM cells treated with MA2. (C) RPMI8226 and MM1R cells were treated with MA2, combined with or without BTZ for 48 h. The effect on viability was determined using a CCK-8 assay. (D) Cell migration was examined in cells as in (C). (E) Apoptosis analysis was conducted in cells as in (C). (F) The global m6A level was detected in RPMI8226 and MM1R cells treated with MA2 at different concentrations. ∗P<0.05; ∗∗P<0.01; ∗∗∗P<0.001.

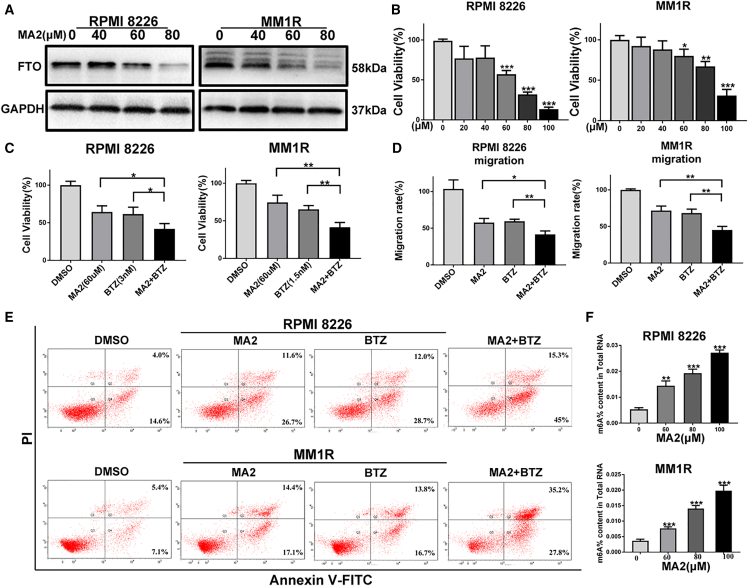

m6A-seq and RNA-seq assays identify HSF1 as a potential target of FTO

To investigate the molecular mechanism of FTO and identify its downstream targets in MM, we conducted m6A-seq in combination with RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis to explore the potential transcriptome-wide m6A-modified gene targets of FTO in RPMI8226 cells with or without FTO overexpression (FTO-OE) or FTO-KD. In stable FTO-OE cells, 224 genes overlapped between the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) by RNA-seq and the differentially methylated mRNA by m6A-seq analysis, while 183 genes overlapped in cells with stable FTO-KD cells (Figure 4A). Gene ontology analysis revealed that the significantly upregulated overlapping genes in FTO-OE cells and differentially downregulated overlapping genes in FTO-KD cells were consistently enriched in cell motility, cell migration, cell adhesion, and cell activation, suggesting that FTO may play critical roles in MM metastasis (Figures S2A and S2B). Among these genes, heat shock factor 1 (HSF1) has been reported to be a potent metastasis-promoting gene in melanoma.33,34 Notably, it has also been reported to be frequently upregulated in MM samples and in almost all EMM samples.35, 36, 37 Moreover, m6A-seq analysis showed that FTO-KD increased m6A enrichment in the coding sequence (CDS) region and 3′-untranslated region (3′-UTR) but had little effect on the 5′-untranslated region (5′-UTR) (Figure 4B). Moreover, FTO-KD altered the total peak distribution and unique peak distribution (Figure 4C). Consistent with the results of previous studies,38 the 20,355 m6A peaks identified in this study were significantly enriched in the most common m6A motif (RRACH) (Figure 4D). Importantly, our m6A-seq analysis identified HSF1 as a direct m6A modification target. m6A peaks were detected in the CDS region and 3′-UTR of the HSF1 transcript, and the number of peaks was increased upon FTO-KD (Figure 4E). Therefore, we selected HSF1 as a candidate target of FTO-mediated m6A modification for the next investigation.

Figure 4.

m6A-seq and RNA-seq identified HSF1 as a potential target of FTO-mediated m6A modification

(A) The intersection of DEGs identified by RNA-seq and m6A methylation genes in cells with stable FTO-OE and FTO-KD. (B) The distribution of m6A peaks across the length of mRNAs. The 5′-UTR indicates the 5′-untranslated region, the 3′-UTR indicates the 3′-untranslated region, and the CDS indicates the coding sequence region. (C) The proportion of m6A peaks distributed in the indicated regions across the entire set of mRNAs and the appearance of new m6A peaks or the loss of existing m6A peaks after FTO-KD. (D) The most common m6A motifs identified by HOMER in RPMI8226 cells with or without FTO-KD. (E) The m6A levels on HSF1 mRNA transcripts in FTO-KD (shFTO) and control (shNC) cells.

HSF1 is a functionally important target gene of FTO in MM

To assess the biological function of HSF1 in MM, we first performed transcriptome array analysis and identified the DEGs in MM patients (Figure S2C). Consistent with the results of previous studies,37 our results confirmed upregulation of the HSF1 transcript in MM (Figure 5A, P = 0.0447) and further upregulation in EMM patients (Figure 5B, P = 0.00026). To further clarify the role of HSF1 in MM, survival analysis was conducted to evaluate the value of HSF1 in the prognosis of MM. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showed that the elevated HSF1 expression predicted a poor prognosis in MM patients (GSE9782)39 (Figure S2D). In addition, compared with NDs, the levels of HSF1 and its target genes HSP70 and HSP90 were higher in MM and EMM samples and were also proven to be higher in MM cell lines, especially in PCL cell lines, than in NDs (Figures 5C–5E and S2E–S2G). Moreover, we evaluated the levels of FTO and HSF1 in PCs from NDs, MM patients, and EMM patients, followed by the Spearman correlation test. The results showed a positive correlation between FTO and HSF1 expression (P < 0.001) (Figure 5F). Furthermore, forced expression of FTO increased the protein level of HSF1 and its target HSPs (Figures 5G and S2H), while FTO-KD produced the opposite results (Figure 5G). These findings indicated that HSF1 was a crucial target gene of FTO in MM.

Figure 5.

HSF1 has been validated to be a functionally important target gene of FTO in MM

(A) Identification of DEGs between MM and ND samples by transcriptome sequencing. (B) Identification of DEGs between EMM and MM samples by transcriptome sequencing. (C) HSF1 expression was further validated in EMM patients (n = 20) by qPCR. (D) Western blot analysis of HSF1 and its target HSPs in CD138 + cells isolated from MM patients or EMM patients. N indicates NDs; M indicates MM patients; and E indicates EMM patients. (E) Immunohistochemical analysis of HSF1 and its target HSPs in biopsies of ND, MM, and EMM samples. (F) qPCR analysis of FTO and HSF1 expression in the same samples of ND, MM, and EMM patients. The correlation between the expression of FTO and HSF1 was determined by the Spearman correlation test. (G) Immunoblot analysis of FTO, HSF1, and its target HSPs in stable RPMI8226 cells with or without forced FTO-OE and FTO-KD. (H) The expression of FTO and HSF1 was determined by Western blot in RPMI8226 and MM1R cells with or without FTO-OE and/or HSF1 knockdown. (I) Cell proliferation assay in cells as in (H). (J) Cell migration assay in cells as in (H). (K) Cell invasion assay in cells as in (H). (L) Cell apoptosis analysis in cells as in (H). (M) The quantification of cell apoptosis for (L). ∗P<0.05; ∗∗P<0.01; ∗∗∗P<0.001.

Next, we investigated whether HSF1 mediates the function of FTO. Knockdown of HSF1 in FTO-OE cells resulted in decreased expression of HSF1 (Figure 5H) accompanied by significant decreases in cell proliferation (Figure 5I), migration (Figure 5J), and invasion (Figure 5K) and a marked increase in apoptosis (Figures 5L and 5M). These findings suggested that the effects of FTO-OE were partially rescued by knockdown of HSF1 and that HSF1 was a crucial downstream target gene of FTO, which mediated its effects in MM.

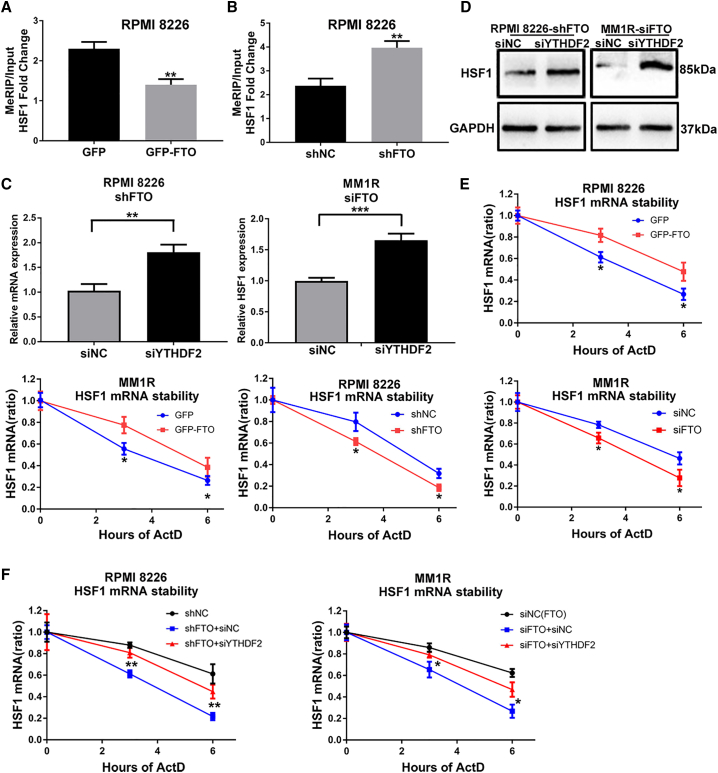

FTO enhances HSF1 mRNA stability through an m6A-YTHDF2-dependent pathway

Next, the mechanism by which FTO regulates HSF1 expression was investigated. Gene-specific m6A IP qPCR38 was used to confirm that FTO influenced HSF1 through m6A modification. We found that forced expression and FTO-KD markedly, respectively, decreased and increased the m6A modification level of HSF1 mRNA (Figures 6A and 6B). Previous studies showed that the m6A reader protein YTHDF2 can target thousands of transcripts, whose half-lives increase upon YTHDF2 knockdown.19 Consistent with early reports, our study showed that knockdown of YTHDF2 with siRNA (siYTHDF2) obviously rescued HSF1 expression in FTO-KD cells (Figures 6C and 6D). Via RNA stability assays,40 we assessed the effect of m6A modification on the stability of the HSF1 transcript. The results suggested that the half-life of the HSF1 transcript was prolonged and shortened in MM FTO-OE and FTO-KD cells, respectively (Figure 6E). Moreover, siYTHDF2 transfection increased HSF1 transcript stability in FTO-KD cells (Figure 6F). Consistent with the above results, siYTHDF2 transfection promoted the proliferation of shFTO cells (Figure S2I). Thus, our findings indicated that the m6A demethylase FTO upregulated HSF1 expression at least partially through a YTHDF2-dependent RNA decay effect in MM cells.

Figure 6.

FTO regulates HSF1 expression by inhibiting m6A/YTHDF2-mediated mRNA decay

(A and B) Gene-specific m6A qPCR analysis of m6A enrichment of HSF1 mRNA in RPMI8226 cells with GFP, GFP-FTO (A), shNC, or shFTO (B). (C and D) qPCR and Western blot analysis of the mRNA (C) and protein (D) levels of HSF1 in RPMI8226 and MM1R cells with or without FTO-KD, in combination with siRNA knockdown of the m6A reader YTHDF2. € qPCR analysis of the mRNA stability of HSF1 in RPMI8226 or MM1R cells with GFP, GFP-FTO, shNC or shFTO, siNC (FTO), or siFTO. (F) qPCR analysis of the mRNA stability of HSF1 in RPMI8226 cells and MM1R cells with or without FTO-KD in combination with or without siRNA knockdown of YTHDF2. ∗P<0.05; ∗∗P<0.01; ∗∗∗P<0.001.

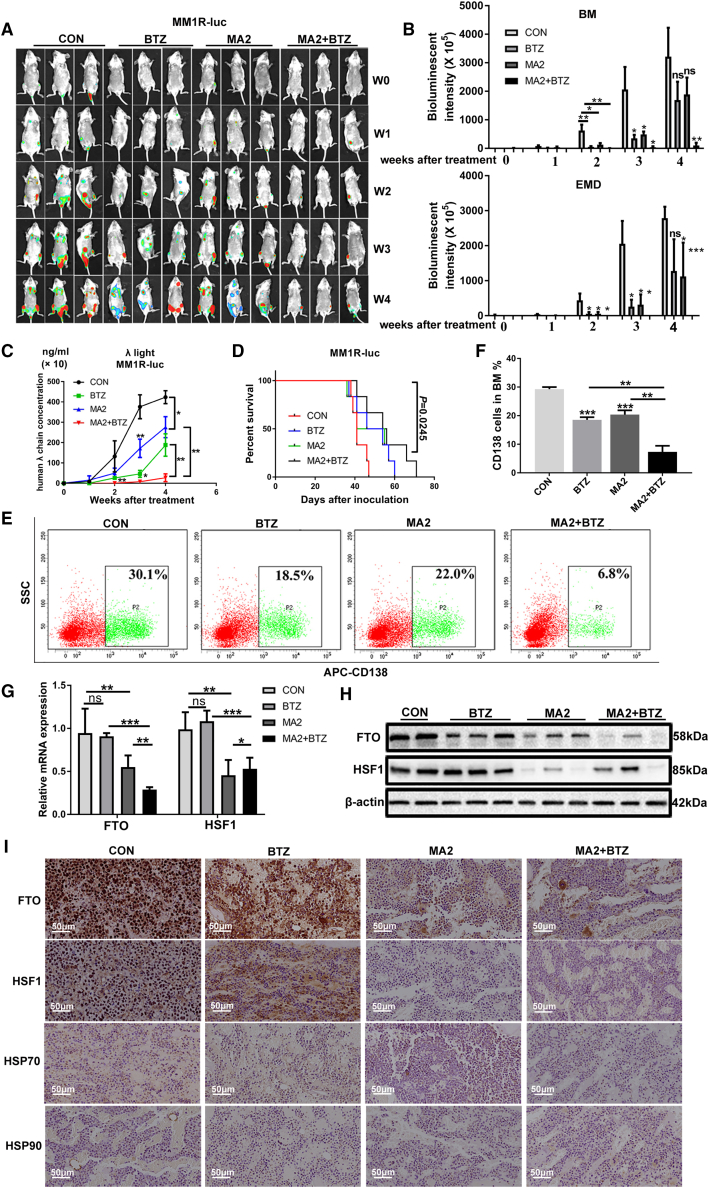

The FTO inhibitor MA2 significantly inhibits MM formation and extramedullary spread in the NCG mouse model of disseminated myeloma

To further study the effect of FTO on the pathogenesis and extramedullary metastasis of MM in vivo, we used MM1R-V-luc cells to establish a xenograft model in NOD-Prkdcem26Cd52il2rgem26Cd22/Nju (NCG) mice via tail intravenous injection. Three days after xenotransplantation, mice were randomly divided into four groups and intraperitoneally injected with MA2 (20 mg/kg) or vehicle control combined with or without BTZ at the indicated time point. We monitored MM development and extramedullary lesion formation weekly by bioluminescence imaging. At early stages (at and before week 3 after treatment), compared with the control treatment, both MA2 and BTZ treatment alone obviously decreased the number of MM cells in the BM of the fore or hind limbs/joints, delayed extramedullary tumor formation (with tumors mainly consisting of extraintestinal tumors, abdominal tumors, and tumors in subcutaneous and other soft tissues, Figure S3A), and reduced the size of EMD regions, although these treatments produced limited effects at late stages (3 weeks after treatment) (Figures 7A and 7B). Notably, combination treatment with MA2 and BTZ almost completely eliminated extramedullary tumors and markedly reduced the sizes of intramedullary and extramedullary tumors at all stages (Figures 7A and 7B). The differences in MM cells loaded in BM sites and the extramedullary region were statistically confirmed by bioluminescence intensity analysis (P < 0.05) (Figure 7B). Treatment effectiveness was further confirmed by assessing the tumor burden (Figure 7C) and mouse survival (Figure 7D). Consistently, flow cytometric analysis showed that mice treated with MA2 or BTZ had fewer MM cell (CD138+)-formed tumors in fore or hind limbs' BM than control mice (P < 0.001) (Figures 7E and 7F) and that combination treatment with MA2 and BTZ further markedly suppressed myeloma bone tumor formation (P < 0.01) (Figures 7E and 7F), highlighting that MA2 in combination with BTZ has synergistic cytotoxic effects. Next, we examined the expression of FTO and HSF1 in fluorescence-positive MM cells. Downregulation of FTO and HSF1 expression was found in mice treated with MA2 alone and in combination with BTZ (Figures 7G–7I and S4G). Additionally, MA2-treated mice exhibited lower expression levels of the target HSPs of HSF1 than mice in other groups (Figures 7I and S4G). In contrast, the expression of these proteins in BTZ-treated mice was not obviously changed compared with that in control mice (Figures 7G–7I and S4G). The BM of MA2- and BTZ-treated mice also contained higher levels of Caspase 3 (a marker of apoptosis) and lower expression of CD34 (a marker of angiogenesis), VEGF (a marker of angiogenesis), Matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9, a kind of metalloproteinases), and Collagen Ⅳ (a type of collagen related to tumor progression) (Figure S3B). We repeated the in vivo studies with another MM cell line (RPMI8226-Luc) and obtained similar results (Figures S4A–S4F). Taken together, these results indicated that MA2 significantly suppressed MM formation and metastasis in vivo and that combination therapy with MA2 and BTZ had a stronger inhibitory effect on the progression of both medullary and extramedullary disease in NCG mice than treatment with either agent alone.

Figure 7.

The FTO inhibitor MA2 significantly inhibits MM progression and enhances the sensitivity of BTZ to MM in vivo

(A) In vivo bioluminescent imaging showing tumor initiation, burden, and metastasis in NCG mice bearing MM1R-luc cells treated with DMSO (the control group), MA2, BTZ, or MA2 in combination with BTZ. W indicates weeks after treatment. (B) Quantification of bioluminescence intensity at BM and extramedullary disease of mice as in (A) after treatment. (C) Tumor burden was analyzed by ELISA of mouse plasma human λ chain concentrations. (D) Survival in mice bearing MM1R-luc tumors treated with vehicle control (CON), BTZ (1 mg/kg per mouse, at days 1, 4, 8, and 11), MA2 (20 mg/kg per mouse, days 1–10), and their combination (MA2+BTZ). (E and F) Flow cytometry analysis of CD138 + cell percentages. (G and H) qPCR and Western blot showing the mRNA (G) and protein (H) levels of FTO and HSF1 in different groups of mice as in (D). (I) Immunohistochemical analysis of FTO, HSF1, and its target HSPs in BM from different groups of mice as in (D). ∗P<0.05; ∗∗P<0.01; ∗∗∗P<0.001.

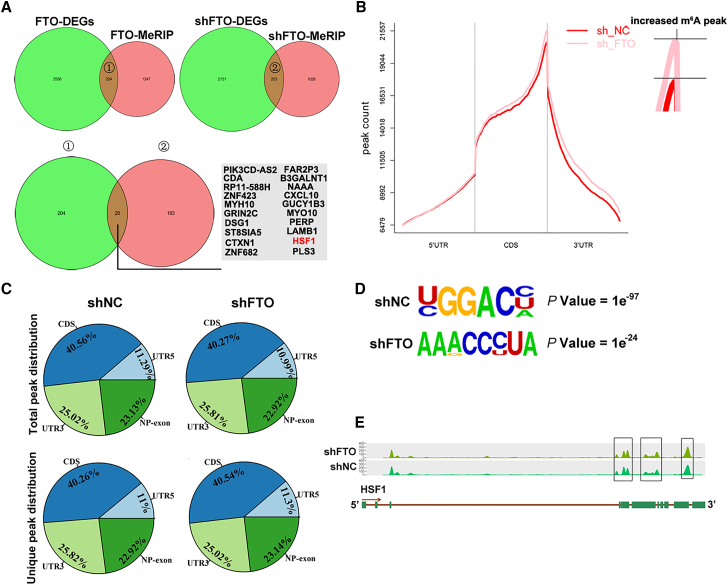

Discussion

Epigenetic modification plays an important role in the pathogenesis of various diseases.41 m6A RNA modification, as a new layer of epigenetic regulation, has recently been demonstrated to be involved in the tumorigenesis of various cancers.13,23 However, the roles of m6A modification in MM pathogenesis are still unclear. Herein, we revealed a tendency toward decreased m6A methylation in MM and EMM patients and identified the FTO demethylase as the main factor for the abnormal m6A level in MM. Our data demonstrated the biological role of FTO-mediated m6A demethylation in MM for the first time and proposed the FTO-HSF1/HSP axis as a potential novel therapeutic target in MM, especially in EMM.

Accumulating evidence has shown that m6A modification exerts tumor-promoting or tumor-suppressing functions by regulating cancer-specific genes.42 In this study, we systematically analyzed the key regulators of m6A methylation in MM and confirmed that FTO was upregulated in primary PCs from MM patients, especially in EMM patients. This finding was similar to a recent study reporting that upregulated FTO promoted both metastasis and invasion in endometrial cancer.43 Moreover, many additional studies have shown that FTO is upregulated and considered to act as a crucial oncogene in various cancers, including leukemia,24 breast cancer,27 and melanoma,28 promoting cancer development and progression. Thus, it is rational to infer that FTO upregulation is potentially involved in MM tumorigenicity and metastasis. ALKBH5, another m6A demethylase, was previously reported to function as an oncogene in GBM44 and breast cancer,45 whereas it likely plays a tumor suppressor role in AML, owing to its frequent copy number loss.46 Therefore, deregulation of m6A methylation may be heterogeneous in the context of different kinds of cancers. Herein, we found that upregulated FTO promoted the proliferation, migration, and invasion and inhibited the apoptosis of MM cells. Moreover, MA2 markedly suppressed the proliferation and migration of MM cells in vitro and inhibited tumor growth and extramedullary spread in therapeutic xenograft models, demonstrating a promising strategy based on m6A modification in the treatment of MM.

To further explore the molecular mechanism by which FTO promotes MM progression, we analyzed m6A-seq and RNA-seq profile data and identified HSF1 as a candidate target of FTO-mediated m6A demethylation. Furthermore, HSF1 was found to be significantly upregulated in MM samples and cell lines, especially in EMM tissues and PCL cell lines, and it was proven to be positively correlated with that of FTO. HSF1, as the transcriptional regulator of the mammalian HSR, is required for the expression of HSPs.47,48 HSF1 is a powerful modifier of tumorigenesis, and its aberrant activation in many cancers is strongly associated with tumor metastasis and poor prognosis.49 In a recent genomic study, HSF1 was one of the six screened potent metastasis-promoting genes in melanoma.34 Moreover, the expression of HSF1 and its transcriptional target genes is associated with metastasis and poor outcomes in breast,50 colon, and lung tumors.49 In addition, Heimberger et al.37 found that HSF1 was overexpressed in half of MM samples and in almost all EMM tissues. HSF1 inhibition was proven to effectively suppress the growth of MM cells.36 Indeed, several inhibitors of HSF1 have been reported, but their low potency and lack of specificity limit their potential for clinical application.51 These inhibitors, while inhibiting HSF1, could also inhibit the transcription factor AP1 as well as the NF-κB, P53, and other signaling pathways.52,53 To date, no specific HSF1 inhibitor has been developed.53 Therefore, a better understanding of the HSF1 regulatory network is essential to achieve specific targeting of HSF1. Herein, we observed that HSF1 silencing functionally inhibited MM cell proliferation, migration, and invasion, similar to the effect of FTO-KD. Moreover, via gain- and loss-of-function studies, we found that FTO positively regulated HSF1 in MM but negatively regulated the m6A level of HSF1 mRNA. Silencing HSF1 partially antagonized the tumor-promoting effects mediated by FTO-OE. Therefore, we demonstrated that HSF1 was a functional downstream target of FTO and that FTO inhibition may provide a novel strategy for improved targeting of HSF1.

Although we demonstrated that FTO modulated HSF1 expression in a manner mediated by m6A demethylation in MM, Mauer et al.54 reported that N6,2′-O-dimethyladenosine (m6Am) was another substrate of FTO, which promoted the decay of mRNAs containing m6Am. Interestingly, a recent review showed that FTO demethylated m6Am rather than internal m6A, thus reducing the stability of m6Am-containing transcripts.18 However, FTO-mediated m6A demethylation has been clearly clarified in AML,24 breast cancer,27 and melanoma,28 and repressing FTO with R-2-hydroxyglutarate (R-2HG) increased m6A levels on MYC/CEBPA mRNAs and promoted mRNA decay.55 Notably, more recent studies have indicated that m6Am levels in many cell lines are extremely low, accounting for only 3%–5% of m6A modifications; thus, the effect of FTO on mRNA stability is exerted mainly through m6A, not m6Am.56,57 Herein, we showed that the levels of over 50% of potential target mRNAs of FTO were positively related to those of FTO in MM cells. FTO-KD decreased the mRNA and protein levels and stability of HSF1 and increased m6A enrichment on the HSF1 transcript in the CDS and 3′-UTR regions, but m6Am is reported to often be located near the 5′-UTR.57 Thus, our findings demonstrated that HSF1 was regulated by FTO-mediated m6A demethylation.

Mechanistically, m6A exerts its effect primarily by recruiting m6A-binding proteins.18 YTHDF2, a reader protein, displays a 10- to 50-fold higher affinity for methylated mRNAs than for nonmethylated mRNAs.58,59 YTHDF2 selectively binds m6A sites and mediates the well-documented instability of m6A-containing mRNAs by recruiting the CCR4-NOT deadenylase complex.19,60 In our study, FTO-KD reduced the stability of mRNA transcripts, suggesting that the m6A reader YTHDF2 might participate in this process. We further investigated whether YTHDF2 affected the HSF1 mRNA expression level via m6A regulation and found that knockdown of YTHDF2 increased the level and stability of HSF1 and promoted cell proliferation, reversing the effect of FTO-KD. These results suggested that m6A enrichment led to HSF1 mRNA decay through a YTHDF2-dependent mechanism in MM. Li et al.24 showed that FTO depletion can lead to an increase in the level of the methyltransferase METTL3, and Yang et al.28 showed that METTL3/METTL14 knockdown reversed the effect of FTO-KD. However, whether FTO-regulated demethylation affects m6A methyltransferase activity in MM needs to be further assessed.

In addition, a previous study showed that activation of the HSR limits the efficacy of several current myeloma drugs, including BTZ.36 HSR, including upregulation of HSPs, can be activated in BTZ-treated myeloma cells, and this activation causes the development of resistance to chemotherapies.36,61 The results of additional studies implied that proteasome inhibitor treatment-induced upregulation of HSPs was critically dependent on HSF1.37 Thus, targeted inhibition of FTO can not only suppress MM formation and progression but also increase sensitivity to chemotherapeutic drugs by inhibiting the HSF1/HSP axis, which seems to be a promising therapeutic strategy for MM patients, especially refractory and relapsed MM patients. MA2, an FTO selective inhibitor, was reported to inhibit glioblastoma stem cell growth and self-renewal,25 and Zhou et al.62 suggested that MA2 may increase the sensitivity of cervical cancer to chemoradiotherapy. In our work, MA2 promoted the anti-MM efficiency of BTZ in vitro, and combination therapy with MA2 and BTZ significantly delayed the occurrence of MM and almost completely eliminated extramedullary metastasis in the NCG mouse model through targeting the FTO/m6A/HSF1/HSPs axis. Notably, no substantial effect of MA2 on the growth of normal cells was detected.25 Therefore, FTO is a promising therapeutic target to suppress the growth and migration/invasion of MM cells, and treatment with specific FTO inhibitors, especially in combination with BTZ, is considered a preferred therapeutic strategy for MM patients, especially those who are at high risk of extramedullary relapse. Interestingly, our study found the FTO expression in MM cells was partially weakened by MA2 (Figure 7I), while a previous study suggested that MA2 could not decrease FTO expression.63 MA2 has been reported to elevate the levels of cellular m6A in the mRNA of human cells.25,32 Recent studies have indicated that, in addition to the roles of m6A modifications in mRNAs, m6A methylation can also regulate the generation and function of noncoding RNAs, such as miRNAs and lncRNAs.64, 65, 66 Furthermore, noncoding RNAs can regulate m6A modifications.64,67,68 Several recent studies have shown that noncoding RNAs can influence carcinogenesis by regulating FTO expression in various of tumors. miR-96 elevates the expression of FTO through regulation of the AMPKα2/FTO/m6A/myc axis in colorectal cancer.69 miR-149-3p modulates the adipogenic differentiation of BMSCs by directly targeting FTO.70 miR-1266 promotes colorectal cancer progression by targeting FTO.71 Therefore, we speculated that MA2 might lead to the elevated expression of noncoding RNAs, which can indirectly decrease the expression of FTO. Further investigation will be required to better elucidate the specific mechanism underlying this result.

In summary, our study demonstrated an FTO-dependent m6A demethylation module that regulates HSF1 expression and has functional implications in MM progression and metastasis, acting at least partially through YTHDF2-mediated mRNA decay. Therefore, given the functional importance of FTO/HSF1 in the formation and drug response of MM, targeting the FTO-m6A-HSF1 axis with selective inhibitors may be a promising therapeutic strategy for MM patients, especially for those with extramedullary disease (Figure 8). As FTO has also been reported to play an oncogenic role in other cancers, our findings in MM may have great significance for cancer pathogenesis and therapy.

Figure 8.

The m6A demethylase FTO promotes myeloma progression by regulating HSF1 in an m6A-YTHDF2-dependent manner

Elevated FTO induces mRNA demethylation, leading to a decrease in HSF1 m6A modification levels in MM and EMM patients. FTO promotes the proliferation, migration, and invasion and inhibits the apoptosis of MM cells. HSF1 is a functional target of FTO-mediated m6A demethylation. FTO attenuated HSF1 degradation in a YTHDF2-dependent manner. The FTO/HSF1/HSP axis is considered a potential novel therapeutic target in MM, especially in extramedullary disease.

Materials and methods

Patient samples

Primary PCs obtained from 15 healthy donors and 35 newly diagnosed MM patients were purified from BM aspirates using CD138 magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The purity of the PCs was assessed by flow cytometric analysis and was found to be >95%. In addition, primary PCs from 20 EMM patients were isolated by tissue homogenization of 20 extramedullary soft tissue masses resulting from hematogenous spread to the skin, brain, oral mucosa, and liver. The diagnoses of all EMM patients were confirmed from the pathological sections. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the institutional review board of Huazhong University of Science and Technology.

Cell culture, MM cells transfected with siRNA, or lentivirus

Synthetic FTO, HSF1 or YTHDF2 siRNA, and siRNA negative control were purchased from RiboBio (Guangzhou, China). The sequences of siRNAs are shown in Table S1. Lentivirus particles were produced using a third-generation packaging system by GeneChem Company (Shanghai, China). Additional details are provided in the Supplementary Materials and Methods.

Microarray assays of the MM patients and EMM patients

Starting with the previously determined gene expression profiles of 3 MM patients assessed by our teams, we added several samples to expand upon the analysis. The global protein-coding transcript profiles of a total of 4 MM patients and 4 EMM patients were analyzed using Human LncRNA Microarray v. 4.0. One microgram of labeled RNA was used for each sample. Quantile normalization and subsequent data processing were performed with the GeneSpring GX v 12.1 software package (Agilent Technologies). After quantile normalization of the raw data, significantly differentially expressed mRNAs between groups were identified by p value and fold change filtering.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR), Western blot, cell proliferation and viability assays, flow cytometric analysis, and migration and invasion assays

The primers for target genes are shown in Table S2. The FTO inhibitor MA232 was kindly provided by Professor Yang (Shanghai Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Sciences). Additional details are provided in the Supplementary Materials and Methods.

Colorimetric analysis (RNA m6A quantification)

Total RNA (200 ng) was isolated from tissue samples and cells using TRIzol. The m6A level in the total RNA was measured with an EpiQuik m6A RNA Methylation Quantification Kit (Epigentek, Farmingdale, NY, USA), following the manufacturer's instructions. The m6A levels were evaluated colorimetrically by measuring the absorbance of each sample at a wavelength of 450 nm and performing calculations on the basis of the standard curve.

MeRIP-seq and RNA-seq, gene-specific m6A qPCR

Methylated RNA immunoprecipitation sequencing (MeRIP-seq) was performed according to a previously reported protocol72 with some changes. The detailed experimental protocols are provided in the Supplementary Materials and Methods.

mRNA stability assay

MM stable FTO-OE and FTO-KD cells were harvested at 6, 3, and 0 h after treatment with actinomycin D (5 μg/mL). Total RNA was isolated with a TRIzol kit (Takara). After reverse transcription, mRNA levels of target transcripts were measured by qPCR. mRNA half-lives were evaluated via linear regression analysis.

Cells and mice used in the animal model

The human MM cell lines RPMI8226 and MM.1R were stably transfected with a luciferase (Luc) vector (GeneChem, Shanghai, China) for in vivo monitoring of tumor growth. Female NCG mice were purchased from the Nanjing Biomedical Research Institute of Nanjing University. Six- to eight-week-old female mice (6–8 mice per group) were obtained at the beginning of the animal experiment. Mice were housed in a pathogen-free environment, and the experimental procedure and protocols were approved by the Committee on Animal Handling of Huazhong University of Science and Technology.

Animal model and treatment

A total of 3×106 RPMI8226/MM1R-Luc cells were intravenously injected into NCG mice to establish a disseminated human MM xenograft model. The in vivo antitumor effect of the FTO inhibitor MA2 combined with or without the first-line chemotherapeutic agent BTZ was evaluated as follows: 3 days post xenotransplantation, MA2 (20 mg/kg), or vehicle control was injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) daily for 10 days, and BTZ was injected intraperitoneally on days 1, 4, 8, and 11. Mouse serum was collected at specified time points during the treatment, and the tumor burden was monitored by detecting myeloma cell-secreted λ light chains via a Human Lambda ELISA Kit (Bethyl Laboratories, No. E88-116). Tumor development was monitored weekly after treatment with an in vivo imaging system (IVIS, SI Imaging, Lago, and LagoX). Luciferin (150 mg/kg, YEASEN, Shanghai, China) was injected intraperitoneally into the mice. After 10–15 min, the tumor photon flux was measured using an IVIS imaging system with an exposure time of 30–60 s. Mice were observed daily and sacrificed when hindlimb paralysis was detected. Fluorescent signal-positive primary tumor (fore or hindlimb BM) and metastasis samples, including spleen (data not shown), extraintestinal tumor, subcutaneous tissue, abdominal tumor, and other soft tissue, were surgically removed for subsequent analysis. Flow cytometry was used to analyze the population of CD138 + cells in fluorescence-positive tissues, whereas H&E staining and immunohistochemical staining were used to assess the expression of FTO and the proteins encoded by its target genes.

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin-embedded sections from biopsy of MM and EMM samples were deparaffinized and blocked, and BM from each group of xenograft mice was fixed in formalin. Additionally, these sections were incubated with antibodies directed against FTO, HSF1, HSP70, HSP90, Caspase3, CD34, VEGF, MMP9, and Collagen Ⅳ at 4°C overnight. Then, the sections were treated with polymer antibodies, developed with DAB-Chromogen, and counterstained with hematoxylin.

Availability of data and materials

Microarray data are available in the GEO database under accession numbers GSE146757 and GSE147841. All other data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics approval and informed consent statement

All experiments related to patient samples were approved by the Ethics Committee of Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology (No. 2020(S091)). All animal procedures were approved by the Committee on Animal Handling of Huazhong University of Science and Technology (No. 2019s-854).

Statistical analysis

All results are presented as the means ± SDs. Differences in FTO and HSF1 levels between independent groups of samples were evaluated by using the Mann-Whitney U test. Correlations between the expression levels of FTO and HSF1 in primary PCs were analyzed by the Spearman correlation test. Comparisons between other groups were analyzed using unpaired Student's t tests. All statistical analyses were carried out with GraphPad Prism 7, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81974007 to C.S.), the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant No. 2019YFC1316204 to Y.H.), and the Clinical Research Physician Program of Tongji Medical College, HUST (to C.S.). The authors thank Caiguang Yang from the CAS Key Laboratory of Receptor Research, Shanghai Institute of Materia Medica, and Chinese Academy of Sciences for helpfully providing MA2; Yuhuan Zheng from the Department of Hematology and State Key Laboratory of Biotherapy and Cancer Center, Sichuan University, West China Hospital, for his valuable advice on establishing the animal model; and Jian Li from the Department of Hematology, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College for their kindly providing precious soft-tissue samples of EMM patients.

Author contributions

Y.H., C.S., and A.X. conceived and designed this study and revised the manuscript; A.X. performed most of the experiments, analyzed the results of all experiments, and wrote the paper; J.Z. collected some of the clinical samples and helped to perform some of the experiments; L.Z. helped culture the cell lines and contributed to establishing the mouse model; H.Y., J. X., and X. Y. helped with the lentivirus-mediated construction of stable cell lines; Q.C., Y.Z., F.F., L.C., and J.D. performed the statistical analyses and provided important suggestions for this study; H.M., Z.H., and F.Z. collected some of the clinical samples. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2021.12.012.

Contributor Information

Chunyan Sun, Email: suncy0618@163.com.

Yu Hu, Email: dr_huyu@126.com.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Palumbo A., Anderson K. Multiple myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;364:1046–1060. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1011442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chim C.S., Kumar S.K., Orlowski R.Z., Cook G., Richardson P.G., Gertz M.A., Giralt S., Mateos M.V., Leleu X., Anderson K.C. Management of relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma: novel agents, antibodies, immunotherapies and beyond. Leukemia. 2018;32:252–262. doi: 10.1038/leu.2017.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dimopoulos M.A., Richardson P.G., Moreau P., Anderson K.C. Current treatment landscape for relapsed and/or refractory multiple myeloma. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2015;12:42–54. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2014.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dimopoulos K., Gimsing P., Gronbaek K. The role of epigenetics in the biology of multiple myeloma. Blood Cancer J. 2014;4:e207. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2014.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walker B.A., Wardell C.P., Chiecchio L., Smith E.M., Boyd K.D., Neri A., Davies F.E., Ross F.M., Morgan G.J. Aberrant global methylation patterns affect the molecular pathogenesis and prognosis of multiple myeloma. Blood. 2011;117:553–562. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-279539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Handa H., Murakami Y., Ishihara R., Kimura-Masuda K., Masuda Y. The role and function of microRNA in the pathogenesis of multiple myeloma. Cancers (Basel) 2019;11:1738. doi: 10.3390/cancers11111738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yap T.A., Winter J.N., Giulino-Roth L., Longley J., Lopez J., Michot J.M., Leonard J.P., Ribrag V., McCabe M.T., Creasy C.L., et al. Phase I study of the novel enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) inhibitor GSK2816126 in patients with advanced hematologic and solid tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019;25:7331–7339. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-4121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rabal O., San Jose-Eneriz E., Agirre X., Sanchez-Arias J.A., de Miguel I., Ordonez R., Garate L., Miranda E., Saez E., Vilas-Zornoza A., et al. Design and synthesis of novel epigenetic inhibitors targeting histone deacetylases, DNA methyltransferase 1, and lysine methyltransferase G9a with in vivo efficacy in multiple myeloma. J. Med. Chem. 2021;64:3392–3426. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c02255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahmad A., Ginnebaugh K.R., Yin S., Bollig-Fischer A., Reddy K.B., Sarkar F.H. Functional role of miR-10b in tamoxifen resistance of ER-positive breast cancer cells through down-regulation of HDAC4. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:540. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1561-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rastgoo N., Abdi J., Hou J., Chang H. Role of epigenetics-microRNA axis in drug resistance of multiple myeloma. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2017;10:121. doi: 10.1186/s13045-017-0492-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang Q., Padi S.K., Tindall D.J., Guo B. Polycomb protein EZH2 suppresses apoptosis by silencing the proapoptotic miR-31. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1486. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amodio N., Leotta M., Bellizzi D., Di Martino M.T., D'Aquila P., Lionetti M., Fabiani F., Leone E., Gulla A.M., Passarino G., et al. DNA-demethylating and anti-tumor activity of synthetic miR-29b mimics in multiple myeloma. Oncotarget. 2012;3:1246–1258. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deng X., Su R., Weng H., Huang H., Li Z., Chen J. RNA N(6)-methyladenosine modification in cancers: current status and perspectives. Cell Res. 2018;28:507–517. doi: 10.1038/s41422-018-0034-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.He L., Li H., Wu A., Peng Y., Shu G., Yin G. Functions of N6-methyladenosine and its role in cancer. Mol. Cancer. 2019;18:176. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-1109-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boccaletto P., Machnicka M.A., Purta E., Piatkowski P., Baginski B., Wirecki T.K., de Crecy-Lagard V., Ross R., Limbach P.A., Kotter A., et al. MODOMICS: a database of RNA modification pathways. 2017 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D303–D307. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roundtree I.A., Evans M.E., Pan T., He C. Dynamic RNA modifications in gene expression regulation. Cell. 2017;169:1187–1200. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao B.S., Roundtree I.A., He C. Post-transcriptional gene regulation by mRNA modifications. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017;18:31–42. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2016.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meyer K.D., Jaffrey S.R. Rethinking m(6)A readers, writers, and erasers. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2017;33:319–342. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100616-060758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang X., Lu Z., Gomez A., Hon G.C., Yue Y., Han D., Fu Y., Parisien M., Dai Q., Jia G., et al. N6-methyladenosine-dependent regulation of messenger RNA stability. Nature. 2014;505:117–120. doi: 10.1038/nature12730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Y., Li Y., Toth J.I., Petroski M.D., Zhang Z., Zhao J.C. N6-methyladenosine modification destabilizes developmental regulators in embryonic stem cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2014;16:191–198. doi: 10.1038/ncb2902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zheng G., Dahl J.A., Niu Y., Fedorcsak P., Huang C.M., Li C.J., Vagbo C.B., Shi Y., Wang W.L., Song S.H., et al. ALKBH5 is a mammalian RNA demethylase that impacts RNA metabolism and mouse fertility. Mol. Cell. 2013;49:18–29. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou J., Wan J., Gao X., Zhang X., Jaffrey S.R., Qian S.B. Dynamic m(6)A mRNA methylation directs translational control of heat shock response. Nature. 2015;526:591–594. doi: 10.1038/nature15377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen X.Y., Zhang J., Zhu J.S. The role of m(6)A RNA methylation in human cancer. Mol. Cancer. 2019;18:103. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-1033-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li Z., Weng H., Su R., Weng X., Zuo Z., Li C., Huang H., Nachtergaele S., Dong L., Hu C., et al. FTO plays an oncogenic role in acute myeloid leukemia as a N(6)-Methyladenosine RNA demethylase. Cancer Cell. 2017;31:127–141. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cui Q., Shi H., Ye P., Li L., Qu Q., Sun G., Sun G., Lu Z., Huang Y., Yang C.G., et al. m(6)A RNA methylation regulates the self-renewal and tumorigenesis of glioblastoma stem cells. Cell Rep. 2017;18:2622–2634. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.02.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu D., Shao W., Jiang Y., Wang X., Liu Y., Liu X. FTO expression is associated with the occurrence of gastric cancer and prognosis. Oncol. Rep. 2017;38:2285–2292. doi: 10.3892/or.2017.5904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Niu Y., Lin Z., Wan A., Chen H., Liang H., Sun L., Wang Y., Li X., Xiong X.F., Wei B., et al. RNA N6-methyladenosine demethylase FTO promotes breast tumor progression through inhibiting BNIP3. Mol. Cancer. 2019;18:46. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-1004-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang S., Wei J., Cui Y.H., Park G., Shah P., Deng Y., Aplin A.E., Lu Z., Hwang S., He C., et al. m(6)A mRNA demethylase FTO regulates melanoma tumorigenicity and response to anti-PD-1 blockade. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:2782. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10669-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Castillo J.J., Mull N., Reagan J.L., Nemr S., Mitri J. Increased incidence of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, leukemia, and myeloma in patients with diabetes mellitus type 2: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Blood. 2012;119:4845–4850. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-06-362830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hernandez-Caballero M.E., Sierra-Ramirez J.A. Single nucleotide polymorphisms of the FTO gene and cancer risk: an overview. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2015;42:699–704. doi: 10.1007/s11033-014-3817-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soderberg K.C., Kaprio J., Verkasalo P.K., Pukkala E., Koskenvuo M., Lundqvist E., Feychting M. Overweight, obesity and risk of haematological malignancies: a cohort study of Swedish and Finnish twins. Eur. J. Cancer. 2009;45:1232–1238. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang Y., Yan J., Li Q., Li J., Gong S., Zhou H., Gan J., Jiang H., Jia G.F., Luo C., et al. Meclofenamic acid selectively inhibits FTO demethylation of m6A over ALKBH5. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:373–384. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kourtis N., Moubarak R.S., Aranda-Orgilles B., Lui K., Aydin I.T., Trimarchi T., Darvishian F., Salvaggio C., Zhong J., Bhatt K., et al. FBXW7 modulates cellular stress response and metastatic potential through HSF1 post-translational modification. Nat. Cell Biol. 2015;17:322–332. doi: 10.1038/ncb3121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scott K.L., Nogueira C., Heffernan T.P., van Doorn R., Dhakal S., Hanna J.A., Min C., Jaskelioff M., Xiao Y., Wu C.J., et al. Proinvasion metastasis drivers in early-stage melanoma are oncogenes. Cancer Cell. 2011;20:92–103. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bustany S., Cahu J., Descamps G., Pellat-Deceunynck C., Sola B. Heat shock factor 1 is a potent therapeutic target for enhancing the efficacy of treatments for multiple myeloma with adverse prognosis. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2015;8:40. doi: 10.1186/s13045-015-0135-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fok J.H.L., Hedayat S., Zhang L., Aronson L.I., Mirabella F., Pawlyn C., Bright M.D., Wardell C.P., Keats J.J., De Billy E., et al. HSF1 Is essential for myeloma cell survival and a promising therapeutic target. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018;24:2395–2407. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-1594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heimberger T., Andrulis M., Riedel S., Stuhmer T., Schraud H., Beilhack A., Bumm T., Bogen B., Einsele H., Bargou R.C., et al. The heat shock transcription factor 1 as a potential new therapeutic target in multiple myeloma. Br. J. Haematol. 2013;160:465–476. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dominissini D., Moshitch-Moshkovitz S., Schwartz S., Salmon-Divon M., Ungar L., Osenberg S., Cesarkas K., Jacob-Hirsch J., Amariglio N., Kupiec M., et al. Topology of the human and mouse m6A RNA methylomes revealed by m6A-seq. Nature. 2012;485:201–206. doi: 10.1038/nature11112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mulligan G., Mitsiades C., Bryant B., Zhan F., Chng W.J., Roels S., Koenig E., Fergus A., Huang Y., Richardson P., et al. Gene expression profiling and correlation with outcome in clinical trials of the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib. Blood. 2007;109:3177–3188. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-09-044974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang H., Weng H., Sun W., Qin X., Shi H., Wu H., Zhao B.S., Mesquita A., Liu C., Yuan C.L., et al. Recognition of RNA N(6)-methyladenosine by IGF2BP proteins enhances mRNA stability and translation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2018;20:285–295. doi: 10.1038/s41556-018-0045-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ottaiano A., Caraglia M. MGMT promoter methylation as a target in metastatic colorectal cancer: rapid turnover and use of folates alter its study-letter. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020;26:3493–3494. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-3991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu J., Harada B.T., He C. Regulation of gene expression by N(6)-methyladenosine in cancer. Trends Cell Biol. 2019;29:487–499. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2019.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang L., Wan Y., Zhang Z., Jiang Y., Lang J., Cheng W., Zhu L. FTO demethylates m6A modifications in HOXB13 mRNA and promotes endometrial cancer metastasis by activating the WNT signalling pathway. RNA Biol. 2020;5:1–14. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2020.1841458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang S., Zhao B.S., Zhou A., Lin K., Zheng S., Lu Z., Chen Y., Sulman E.P., Xie K., Bogler O., et al. m(6)A demethylase ALKBH5 Maintains tumorigenicity of glioblastoma stem-like cells by sustaining FOXM1 expression and cell proliferation program. Cancer Cell. 2017;31:591–606.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang C., Samanta D., Lu H., Bullen J.W., Zhang H., Chen I., He X., Semenza G.L. Hypoxia induces the breast cancer stem cell phenotype by HIF-dependent and ALKBH5-mediated m(6)A-demethylation of NANOG mRNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2016;113:E2047–E2056. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1602883113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kwok C.T., Marshall A.D., Rasko J.E., Wong J.J. Genetic alterations of m(6)A regulators predict poorer survival in acute myeloid leukemia. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2017;10:39. doi: 10.1186/s13045-017-0410-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Qian S.B., McDonough H., Boellmann F., Cyr D.M., Patterson C. CHIP-mediated stress recovery by sequential ubiquitination of substrates and Hsp70. Nature. 2006;440:551–555. doi: 10.1038/nature04600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu J., Liu T., Rios Z., Mei Q., Lin X., Cao S. Heat shock proteins and cancer. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2017;38:226–256. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2016.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mendillo M.L., Santagata S., Koeva M., Bell G.W., Hu R., Tamimi R.M., Fraenkel E., Ince T.A., Whitesell L., Lindquist S. HSF1 drives a transcriptional program distinct from heat shock to support highly malignant human cancers. Cell. 2012;150:549–562. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Santagata S., Hu R., Lin N.U., Mendillo M.L., Collins L.C., Hankinson S.E., Schnitt S.J., Whitesell L., Tamimi R.M., Lindquist S., et al. High levels of nuclear heat-shock factor 1 (HSF1) are associated with poor prognosis in breast cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2011;108:18378–18383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115031108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Whitesell L., Lindquist S. Inhibiting the transcription factor HSF1 as an anticancer strategy. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets. 2009;13:469–478. doi: 10.1517/14728220902832697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.de Billy E., Powers M.V., Smith J.R., Workman P. Drugging the heat shock factor 1 pathway: exploitation of the critical cancer cell dependence on the guardian of the proteome. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:3806–3808. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.23.10423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vilaboa N., Bore A., Martin-Saavedra F., Bayford M., Winfield N., Firth-Clark S., Kirton S.B., Voellmy R. New inhibitor targeting human transcription factor HSF1: effects on the heat shock response and tumor cell survival. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:5797–5817. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mauer J., Luo X., Blanjoie A., Jiao X., Grozhik A.V., Patil D.P., Linder B., Pickering B.F., Vasseur J.J., Chen Q., et al. Reversible methylation of m(6)Am in the 5’ cap controls mRNA stability. Nature. 2017;541:371–375. doi: 10.1038/nature21022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Su R., Dong L., Li C., Nachtergaele S., Wunderlich M., Qing Y., Deng X., Wang Y., Weng X., Hu C., et al. R-2HG exhibits anti-tumor activity by targeting FTO/m(6)A/MYC/CEBPA signaling. Cell. 2018;172:90–105.e123. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.11.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nachtergaele S., He C. Chemical modifications in the life of an mRNA transcript. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2018;52:349–372. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-120417-031522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wei J., Liu F., Lu Z., Fei Q., Ai Y., He P.C., Shi H., Cui X., Su R., Klungland A., et al. Differential m(6)A, m(6)Am, and m(1)A demethylation mediated by FTO in the cell nucleus and cytoplasm. Mol. Cell. 2018;71:973–985.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Theler D., Dominguez C., Blatter M., Boudet J., Allain F.H. Solution structure of the YTH domain in complex with N6-methyladenosine RNA: a reader of methylated RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:13911–13919. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhu T., Roundtree I.A., Wang P., Wang X., Wang L., Sun C., Tian Y., Li J., He C., Xu Y. Crystal structure of the YTH domain of YTHDF2 reveals mechanism for recognition of N6-methyladenosine. Cell Res. 2014;24:1493–1496. doi: 10.1038/cr.2014.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Du H., Zhao Y., He J., Zhang Y., Xi H., Liu M., Ma J., Wu L. YTHDF2 destabilizes m(6)A-containing RNA through direct recruitment of the CCR4-NOT deadenylase complex. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:12626. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mitsiades N., Mitsiades C.S., Poulaki V., Chauhan D., Fanourakis G., Gu X., Bailey C., Joseph M., Libermann T.A., Treon S.P., et al. Molecular sequelae of proteasome inhibition in human multiple myeloma cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2002;99:14374–14379. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202445099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhou S., Bai Z.L., Xia D., Zhao Z.J., Zhao R., Wang Y.Y., Zhe H. FTO regulates the chemo-radiotherapy resistance of cervical squamous cell carcinoma (CSCC) by targeting beta-catenin through mRNA demethylation. Mol. Carcinog. 2018;57:590–597. doi: 10.1002/mc.22782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xiao L., Li X., Mu Z., Zhou J., Zhou P., Xie C., Jiang S. FTO inhibition enhances the antitumor effect of temozolomide by targeting MYC-miR-155/23a cluster-MXI1 feedback circuit in glioma. Cancer Res. 2020;80:3945–3958. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-20-0132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ma S., Chen C., Ji X., Liu J., Zhou Q., Wang G., Yuan W., Kan Q., Sun Z. The interplay between m6A RNA methylation and noncoding RNA in cancer. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2019;12:121. doi: 10.1186/s13045-019-0805-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wu B., Su S., Patil D.P., Liu H., Gan J., Jaffrey S.R., Ma J. Molecular basis for the specific and multivariant recognitions of RNA substrates by human hnRNP A2/B1. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:420. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02770-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yang D., Qiao J., Wang G., Lan Y., Li G., Guo X., Xi J., Ye D., Zhu S., Chen W., et al. N6-Methyladenosine modification of lincRNA 1281 is critically required for mESC differentiation potential. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:3906–3920. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chen T., Hao Y.J., Zhang Y., Li M.M., Wang M., Han W., Wu Y., Lv Y., Hao J., Wang L., et al. m(6)A RNA methylation is regulated by microRNAs and promotes reprogramming to pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;16:289–301. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yang Z., Li J., Feng G., Gao S., Wang Y., Zhang S., Liu Y., Ye L., Li Y., Zhang X. MicroRNA-145 modulates N(6)-methyladenosine levels by targeting the 3’-untranslated mRNA region of the N(6)-methyladenosine binding YTH domain family 2 protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2017;292:3614–3623. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.749689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yue C., Chen J., Li Z., Li L., Chen J., Guo Y. microRNA-96 promotes occurrence and progression of colorectal cancer via regulation of the AMPKalpha2-FTO-m6A/MYC axis. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020;39:240. doi: 10.1186/s13046-020-01731-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Li Y., Yang F., Gao M., Gong R., Jin M., Liu T., Sun Y., Fu Y., Huang Q., Zhang W., et al. miR-149-3p regulates the switch between adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs by targeting FTO. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 2019;17:590–600. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2019.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shen X.P., Ling X., Lu H., Zhou C.X., Zhang J.K., Yu Q. Low expression of microRNA-1266 promotes colorectal cancer progression via targeting FTO. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2018;22:8220–8226. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_201812_16516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dominissini D., Moshitch-Moshkovitz S., Salmon-Divon M., Amariglio N., Rechavi G. Transcriptome-wide mapping of N(6)-methyladenosine by m(6)A-seq based on immunocapturing and massively parallel sequencing. Nat. Protoc. 2013;8:176–189. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Microarray data are available in the GEO database under accession numbers GSE146757 and GSE147841. All other data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.