Abstract

Immunosuppression in response to severe sepsis remains a serious human health concern. Evidence of sepsis-induced immunosuppression includes impaired T lymphocyte function, T lymphocyte depletion or exhaustion, increased susceptibility to opportunistic nosocomial infection, and imbalanced cytokine secretion. CD4 T cells play a critical role in cellular and humoral immune responses during sepsis. Here, using an RNA sequencing assay, we found that the expression of T cell-containing immunoglobulin and mucin domain-3 (Tim-3) on CD4 T cells in sepsis-induced immunosuppression patients was significantly elevated. Furthermore, the percentage of Tim-3+ CD4 T cells from sepsis patients was correlated with the mortality of sepsis-induced immunosuppression. Conditional deletion of Tim-3 in CD4 T cells and systemic Tim-3 deletion both reduced mortality in response to sepsis in mice by preserving organ function. Tim-3+ CD4 T cells exhibited reduced proliferative ability and elevated expression of inhibitory markers compared with Tim-3−CD4 T cells. Colocalization analyses indicated that HMGB1 was a ligand that binds to Tim-3 on CD4 T cells and that its binding inhibited the NF-κB signaling pathway in Tim-3+ CD4 T cells during sepsis-induced immunosuppression. Together, our findings reveal the mechanism of Tim-3 in regulating sepsis-induced immunosuppression and provide a novel therapeutic target for this condition.

Keywords: sepsis-induced immunosuppression, T cell-containing immunoglobulin and mucin domain-3 (Tim-3), CD4 T cells, biomarker

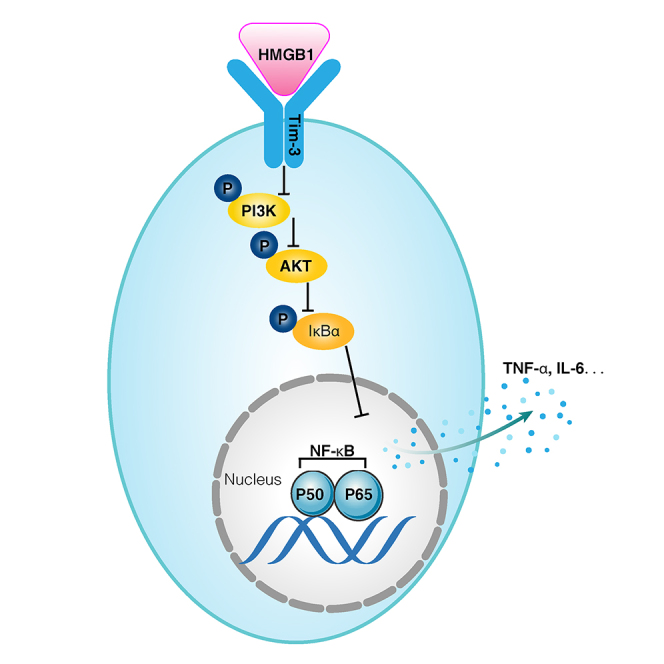

Graphical abstract

This study first clarifies that HMGB1 is a ligand that binds to Tim-3 on CD4 T cells, and their binding inhibits the NF-κB signaling pathway in Tim-3+ CD4 T cells during sepsis-induced immunosuppression. The study provides a potential therapeutic target for sepsis-induced immunosuppression.

Introduction

Sepsis is an illness with high incidence and mortality. More than 14,000 people worldwide die of sepsis every day. Moreover, sepsis treatment consumes many medical resources, posing a great threat to human health and seriously affecting the quality of human life.1 Even if the prognosis has improved, with more sepsis survivors being discharged from hospitals, approximately one-sixth of sepsis patients die within the first year after discharge. Current treatment includes supportive care and antibiotics, but specific interventions to reduce secondary infection-related mortality are lacking.2 Sepsis is related to the host response to infection, and its pathophysiological mechanism is complex.3 The host's response to infection initially activates natural immunity, triggering a cascade of inflammatory cytokine release and promoting a “cytokine storm.” During this period, the first peak of septic death occurs due to hyperinflammation. However, with the application of multiple organ support therapy (MOST) in the ICU, such as continuous blood purification (CBP) and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), most patients can survive this stage.4 Subsequently, to maintain the immune balance and prevent organ dysfunction caused by the continuous release of inflammatory cytokines, compensatory anti-inflammatory response syndrome is driven to control the proinflammatory response. This stage is characterized by immunosuppression and secondary infection. This is the second peak of death in sepsis patients who die of immunosuppression or immunoparalysis.5 During sepsis-induced immunosuppression, natural immune cells, such as macrophages, may be overactivated, dendritic cells exhibit defects in antigen presentation or even apoptosis, and bone marrow-derived inhibitory cells begin to activate.6 In adaptive immunity, all lymphocytes, except regulatory T cells, undergo disfunction and apoptosis.7 This is also an important cause of immunosuppression in sepsis patients. This may explain why all immunosuppressive treatments against the sepsis-induced cytokine storm, whether glucocorticoid inhibition or targeted inhibition, are ineffective.8,9 Therefore, identifying immunosuppressive patients using specific biomarkers and immunomodulators has great potential for the future treatment of sepsis.

The treatment of septic immunoparalysis requires a further understanding of the mechanism of the host immune defects that occur in response to sepsis.10 In adaptive immune cells, T cells are activated to eliminate pathogens by secreting cytokines, such as TNF-α and INF-γ. B cells differentiate into plasma cells and mediate the clearance of pathogens by producing neutralizing antibodies.11,12 CD4 T cells play a crucial role in cellular and humoral immune responses during sepsis. They also help to activate CD8 T cells and play a critical role in the class conversion or isotype switching of Ig in the initial type and memory B cell response. In addition, CD4 T cells participate in the sepsis-induced immune inflammatory response by producing cytokines.13,14 Therefore, understanding how CD4 T cells are affected by sepsis, including changes in their gene expression and function, is of vital importance for pathophysiological research on sepsis.

T cell-containing immunoglobulin and mucin domain-3 (Tim-3) was initially identified as a molecule expressed on CD4 and CD8 T cells,15 and it has since been identified as a T cell exhaustion marker in cancer and chronic infection, especially when coexpressed with programmed death-1 (PD-1).16 However, treatment to block Tim-3 or Tim-3 together with other coinhibitory proteins, such as PD-1, in patients with sepsis has yielded inconsistent results. Boomer et al. demonstrated that Tim-3 expression was significantly higher on CD4 T cells in patients with sepsis.17 During sepsis, Tim-3 and PD-1 play a crucial role in the immune response of T lymphocytes and monocytes. The Tim-3 signaling pathway mediates expression of TNF-α and IL-10 by T lymphocytes in sepsis patients.18 Zhao et al. demonstrated that blocking Tim-3 using soluble Tim-3 immunoglobulin (sTim-3-IgG) during the acute stage of sepsis aggravated the sepsis-induced macrophage hyperinflammatory response and lymphocyte apoptosis in a cecal ligation puncture (CLP) model. However, during the late phase of sepsis, sTim-3-IgG enhanced the anti-inflammatory role of CD4 T cells.19 Yang et al. showed that Tim-3 is involved in maintaining sepsis by negatively regulating lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-TLR4-mediated NF-κB activation. Blockade and/or downregulation of Tim-3 is related to the severity of sepsis, and Tim-3 might represent a new target for the treatment of sepsis.20 Based on these studies, the possible effects of Tim-3 on the sepsis-induced immunosuppression is uncertain and is worthy of further investigation.

Using RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), we found that expression of Tim-3 on CD4 T cells in sepsis patients was significantly elevated. Conditional knockout of Tim-3 in CD4 T cells significantly reduced mortality in a mouse sepsis model by preserving organ function. HMGB1 serves as a ligand that binds to Tim-3 on CD4 T cells, and its binding inhibits the NF-κB/TNF-α signaling pathway induced by Tim-3+ CD4 T cells during sepsis-induced immunosuppression.

Results

The proportion of Tim-3+ CD4 T cells is increased in the peripheral blood of septic immunosuppression patients

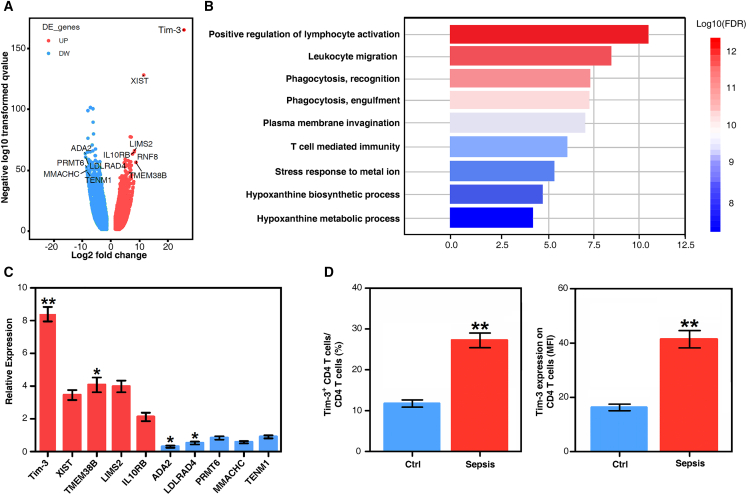

Septic immunosuppression often occurs 7 to 10 days after the diagnosis of sepsis.21,22 Therefore, we collected peripheral blood samples from 20 sepsis patients 14 days after sepsis diagnosis and 20 healthy volunteers (demographic and clinical characteristics of sepsis patients are shown in Table S1). Flow cytometry-sorted CD4 T cells were detected using RNA-seq. The results suggested that there were multiple differentially expressed genes in CD4 T cells from sepsis patients compared with healthy volunteers. The top five upregulated genes included T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain 3 (Tim-3), X inactive specific transcript (XIST), transmembrane protein 38B (TMEM38B), LIM zinc finger domain containing 2 (LIMS2), and interleukin 10 receptor subunit beta (IL10RB). The top five downregulated genes included transcriptional adaptor 2B (ADA2), low-density lipoprotein receptor class A domain containing 4 (LDLRAD4), protein arginine methyltransferase 6 (PRMT6), methylmalonic aciduria and homocystinuria type C protein (MMACHC), and teneurin transmembrane protein 1 (TENM1) (Figure 1A and Data S1). Gene ontology enrichment analysis revealed that these genes were enriched in immune-related pathways, especially lymphocyte- and leukocyte-related pathways, as well as several metabolic pathways (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

The proportion of Tim-3+ CD4 T cells is increased in CD4 T cells from septic immunosuppression patients

(A) Volcano plot of CD4 T cells from healthy volunteers and septic immunosuppression patients. The top five upregulated genes were Tim-3, XIST, TMEM38B, LIMS2, and IL10RB. The top five downregulated genes were ADA2, LDLRAD4, PRMT6, MMACHC, and TENM1. (B) Enriched gene ontology (GO) functions of upregulated genes in CD4 T cells. Upregulated genes in CD4 T cells of septic immunosuppression patients were enriched in immune-related pathways, especially lymphocyte- and leukocyte-related pathways, as well as several metabolic pathways. (C) Verification of the transcription levels of the top five upregulated and top five downregulated genes in CD4 T cells between sepsis patients and healthy volunteers (means ± SD; n = 30; ∗p < 0.05 and ∗∗p < 0.01 versus healthy control group, one-way ANOVA). (D) Tim-3 expression on CD4 T cells in 30 sepsis patients and 30 healthy volunteers by flow cytometry. The percentage of Tim-3-positive CD4 T cells (means ± SD; n = 30; ∗∗p < 0.01 versus healthy control group, one-way ANOVA). Tim-3 expression on CD4 T cells is presented as the mean fluorescence intensity (means ± SD; n = 30; ∗∗p < 0.01 versus healthy control group, one-way ANOVA).

In addition, we verified the transcription and expression levels of the five upregulated and five downregulated genes in CD4 T cells using real-time PCR (Table S2). The results showed that the transcriptional level of Tim-3 was significantly increased in CD4 T cells in sepsis patients compared with healthy controls (p < 0.01, Figure 1C). Expression levels of Tim-3 in CD4 T cells were detected by flow cytometry. The percentage of Tim-3+ CD4 T cells and expression of Tim-3 on CD4 T cells in 30 sepsis patients were significantly higher than those in healthy controls (p < 0.01, Figure 1D). Together, these findings suggest that the proportion of Tim-3+ CD4 T lymphocytes in sepsis patients was significantly elevated compared to that in healthy volunteers. Therefore, we further examined the effect of Tim-3 knockout on survival rate in septic mice.

Tim-3 knockout attenuated sepsis-induced mortality by preserving organ function

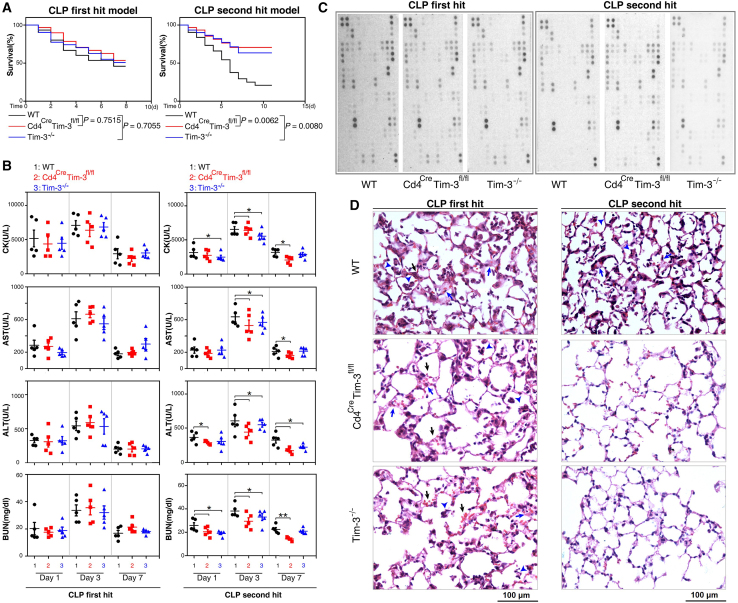

Due to the application of MOST in the ICU, such as CBP and ECMO, most patients can survive until an effective adaptive immune response is initiated but die due to secondary pneumonia or other acquired infections after discharge.4 However, most deaths in animal sepsis models occur 3 days before the effective initiation of the adaptive immune response.23 The well-accepted sepsis CLP model is a "first hit" model, and most animals die during the stage of the proinflammatory response (SIRS). The sepsis "second hit model" better reflects susceptibility to secondary infection and late onset immunosuppression because animals often die during the anti-inflammatory stage.22 Using Cd4CreTim-3fL/fL mice and Tim-3−/− mice, we examined the effect of Tim-3 conditional knockout in CD4 T cells and systemic knockout of Tim-3 on the survival rate of CLP first hit and second hit mouse models. Our results revealed that neither Tim-3 conditional knockout in CD4 T cells nor systemic knockout of Tim-3 affected mortality in response to the CLP first hit (Figure 2A). However, the survival rates of Cd4CreTim-3fL/fL and Tim-3−/− mice exposed to the CLP second hit were significantly higher than those of wild-type mice (p = 0.0062 and p = 0.008, Figure 2A). Blood biochemical measurement of primary organ enzymes also revealed the protective effect of Tim-3 conditional knockout on CD4 T cells and Tim-3 systemic knockout in a sepsis immunosuppressive model. In the sepsis second hit model, heart (creatine kinase), liver (aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase), and kidney (blood urea nitrogen) metabolic readouts in Cd4CreTim-3fL/fL and Tim-3−/− mice were significantly lower than those of wild-type mice (Figure 2B). Mouse cytokine array kit analysis showed that Tim-3 conditional knockout of CD4 T cells and systemic knockout of Tim-3 had no significant effect on the expression of cytokines in the peripheral blood of the CLP first and second hit models (Figure 2C). Tim-3 conditional knockout of CD4 T cells decreased the severity of septic lung injury in the CLP second hit model. Alveolar septum thickening, leukocyte infiltration, alveolar congestion, and edema were significantly reduced (Figure 2D). These results suggested that Tim-3 conditional knockout in CD4 T cells and Tim-3 systemic knockout both reduce the mortality of septic immunosuppression by preserving the function of vital organs and alleviating septic lung inflammation.

Figure 2.

Tim-3 knockout reduces sepsis mortality by preserving organ function

(A) Survival curves of WT, Cd4CreTim-3fL/fL, and Tim-3−/− mice in the CLP first hit and second hit models of sepsis. p = 0.0062 compared with WT and Cd4CreTim-3fL/fL and p = 0.008 compared with WT and Tim-3−/− mouse in CLP second hit mouse of sepsis (n = 30 mice per group; Kaplan–Meier survival analysis). (B) Serum enzyme activity in the heart, liver, and kidney of CLP first and second hit mouse post 1, 3, and 7 days (n = 5; ∗p < 0.05 and ∗∗p < 0.01 versus WT, one-way ANOVA). (C) Secreted cytokines in WT, Cd4CreTim-3fL/fL, and Tim-3−/− mouse peripheral blood were profiled using a Proteome Profiler™ Array Mouse XL Cytokine Array Kit. (D) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of WT, Cd4CreTim-3fL/fL, and Tim-3−/− mouse lungs: alveolar septum thickening (blue arrow), leukocyte infiltration (blue arrowhead), alveolar congestion and edema (black arrow). Magnification, 200×; Scale bars, 100 μm.

Tim-3 correlates with a more severe exhaustion state of CD4 T cells during septic immunosuppression

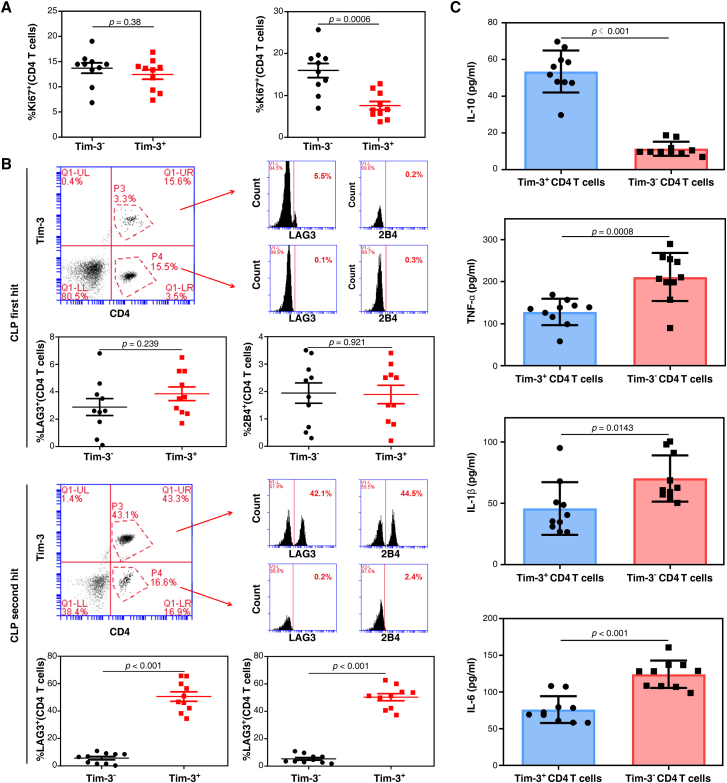

To compare the effect of Tim-3 expression on the proliferation of CD4 T cells, we analyzed the percentage of Ki67-positive cells in Tim-3+ CD4 T cells and Tim-3– CD4 T cells in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). The results revealed no differences in Ki67 expression between Tim-3+ CD4 T cells and Tim-3– CD4 T cells in CLP first hit mouse PBMCs (p = 0.38, Figure 3A), but Tim-3+ CD4 T cells presented a significantly lower Ki67 expression than the Tim-3– population in septic immunosuppression mouse PBMCs (p = 0.0006, Figure 3A). We further assessed the phenotypic profile of Tim-3+ CD4 T cells and Tim-3– CD4 T cells using two inhibitory markers, LAG3 and 2B4.24 Expression of LAG3 and 2B4 on Tim-3+ CD4 T cells was significantly higher than on Tim-3– CD4 T cells in septic immunosuppression mouse PBMCs (p < 0.0001 for CLP second hit mouse, Figure 3B) but not in the CLP first hit model (p = 0.239 and p = 0.921 for LAG3 and 2B4, Figure 3B). These results suggested that Tim-3+ CD4 T cells exhibited elevated expression of inhibitory markers, which might be related to the immunosuppressive state induced by sepsis.

Figure 3.

Tim-3 is correlated with a more severe exhaustion state of CD4 T cells during septic immunosuppression

(A) The proliferation ability of Tim-3+ CD4 T cells and Tim-3– CD4 T cells after CLP first hit (left) and second hit (right) is shown as the percentage of Ki67+ cells. Data are representative of three independent experiments with 10 mice per group in each experiment (p = 0.0006 in CLP second hit mouse of sepsis, one-way ANOVA). (B) Expression of LAG3 and 2B4 on Tim-3+ CD4 T cells and Tim-3– CD4 T cells after CLP first hit and second hit models (n = 10; p < 0.01 in CLP second hit mouse of sepsis, one-way ANOVA). (C) Release of IL-10, TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 in Tim-3+ CD4 T cells and Tim-3− CD4 T cells in response to 100 ng/mL LPS stimulation in vitro for 24 h (p = 0.0008 for TNF-α, p = 0.0143 for IL-1β, p < 0.01 for IL-10 and IL-6, one-way ANOVA).

We next examined cytokine secretion by Tim-3+ CD4 T cells and Tim-3– CD4 T cells in response to LPS stimulation in vitro. Interleukin-10 (IL-10) is an inhibitory cytokine primarily secreted by macrophages and T helper cells. In contrast to effector cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, IL-10 production was significantly increased by Tim-3+ CD4 T cells compared with Tim-3– CD4 T cells (p < 0.001 for IL-10; p = 0.0008 for TNF-α; p = 0.0143 for IL-1β; p < 0.0001 for IL-6; Figure 3C). These results suggested that the functional exhaustion of CD4 T cells was characterized by a highly reduced ability to secrete the inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 compared to a highly enhanced ability to express the inhibitory cytokine IL-10. These results indicated that Tim-3+ CD4 T cells might affect the cellular immunological state by regulating cell proliferation and cytokine production. Tim-3 expression on CD4 T cells might represent an immunophenotypic marker for determining the exhausted state of CD4 T cells.

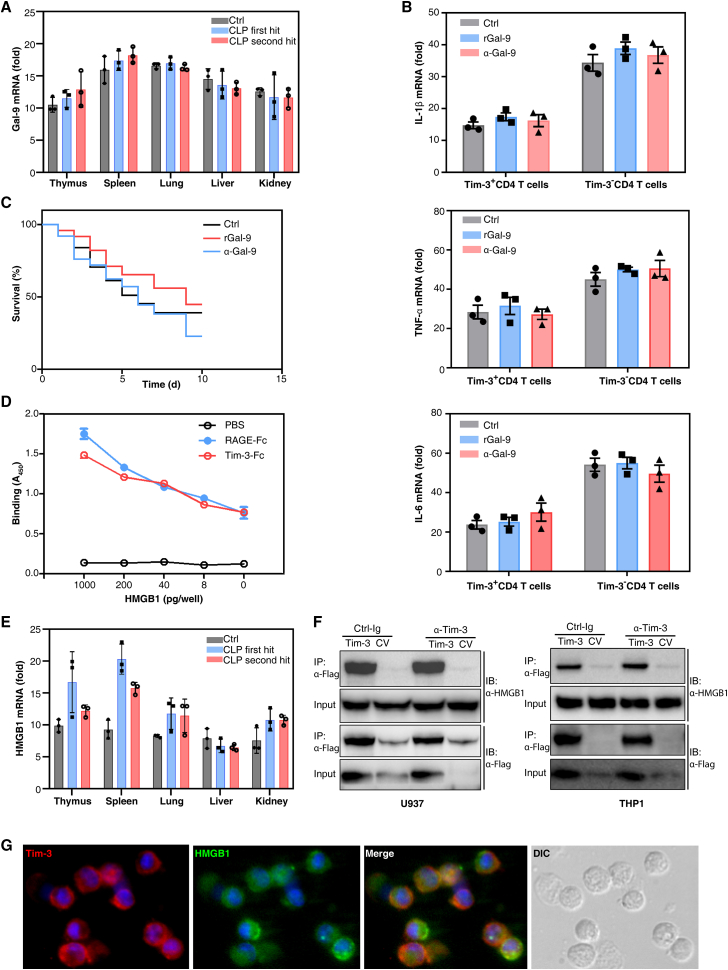

HMGB1 serves as a ligand for Tim-3 on CD4 T cells in septic immunity

Galectin-9 (Gal-9), HMGB1, CEACAM-1, phosphatidylserine (PtdSer), and other ligands are involved in the regulation of Tim-3 and its effects on T cell inflammation and exhaustion. Gal-9 is the first reported Tim-3 ligand. IFN-γ and IL-1β enhance the Tim-3-Gal-9 interaction in TH1-type immunity and inflammation. The binding of Gal-9 to Tim-3 transmits a signal to T cells and triggers Th1 cell apoptosis.25,26 Therefore, we first verified whether Gal-9 was the ligand of Tim-3 on CD4 T cells during sepsis. The transcriptional levels of Gal-9 in multiple organs of two sepsis mouse models were examined. In control, CLP first hit and second hit group, both the transcriptional and translational level of Gal-9 in thymus was not different compared with that in lung, liver, and kidney. The transcriptional and translational level of Gal-9 in spleen was also not different compared with that in lung, liver, and kidney (p > 0.05 by one-way ANOVA, Figure 4A and S1A). Moreover, treatment with recombinant Gal-9 (rGal-9) or mAb against Gal-9 (α-Gal-9) did not promote Tim-3-mediated IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 production in Tim3+ or Tim3– CD4 T cells (p > 0.05 by one-way ANOVA, Figures 4B and S1B). Furthermore, treatment with rGal-9 or α-Gal-9 had no effect on the survival rate of mice with sepsis induced by the CLP second hit model (Figure 4C). Therefore, Tim-3 regulates septic immunity in a Gal-9-independent mechanism.

Figure 4.

HMGB1 is a ligand for Tim-3 on CD4 T cells in septic immunity

(A) RT-PCR quantification of Gal-9 mRNA in the thymus, spleen, lung, liver, and kidney of CLP first hit and second hit model mice. The results are presented relative to the expression of GAPDH (n = 3; means ± SD; one-way ANOVA). (B) RT-PCR analysis of IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 mRNA without or with rGal-9 or α-Gal-9 treatment for 12 h. The results are presented relative to GAPDH expression (n = 3; means ± SD; one-way ANOVA). (C) Administration of rGal-9 or α-Gal-9 to mice prevented CLP second hit-induced death (n = 20 mice per group; Kaplan–Meier survival analysis). (D) Binding of biotin-labeled rHMGB1 to plates coated with PBS or fusions of Fc-RAGE (RAGE-Fc) or Fc-Tim-3 measured by colorimetric analysis and presented as absorbance at 450 nm. (E) RT-PCR quantification of HMGB1 mRNA in the thymus, spleen, lung, liver, and kidney of CLP first hit and second hit mouse models. The results are presented relative to the expression of GAPDH (n = 3; means ± SD; p < 0.05 thymus versus lung, liver, or kidney in CLP second hit model; p < 0.05 spleen versus lung, liver, or kidney in CLP second hit model by one-way ANOVA). (F) Immunoprecipitation of U937 or THP1 cells transfected with vector encoding Flag-tagged Tim-3 or control vector and stimulated for 2 h with HMGB1 in the presence of control immunoglobulin (Ig) or mAb to Tim-3, followed by IP with mAb M2 to the FLAG tag and immunoblot analysis with anti-HMGB1 or anti-Flag. (G) Immunofluorescence image of Tim-3 (red) in Tim-3+ CD4 T cells colocalized with recombinant HMGB1 (green). Magnification, 600×.

High-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) is a nuclear protein that plays a crucial role as a damage-associated molecular pattern. HMGB1 can bind to Tim-3 expressed on dendritic cells, and this binding inhibits the innate immune response to nucleic acids.27 Recently, it has been suggested that HMGB1/Tim-3 may also downregulate T cell responses.28 HMGB1 acts on a variety of cells and interacts with RAGE, TLR4, and other ligands to regulate the pleiotropic function of these entities in a variety of physiological and pathological conditions.29 Thus, we investigated the potential interaction between HMGB1 and Tim-3. The results revealed that Tim-3 had a relatively strong binding affinity for HMGB1, similar to the known HMGB1 receptor RAGE (Figure 4D). In control group, the transcriptional level of HMGB1 in thymus and spleen was not different compared with that in lung, liver, and kidney. But the transcription level of HMGB1 in thymus and spleen was significantly higher than that in lung, liver, and kidney in the second-hit sepsis model, indicating that HMGB1 was mainly produced in immune organs (Figures 4E and S1C). Previous studies have shown that the interplay between HMGB1 and Tim-3 coordinately regulates the innate immune response of tumor-infiltrating dendritic cells.27 Therefore, we examined whether the binding of HMGB1 and Tim-3 was also a critical driver of the immune response in sepsis. The binding of HMGB1 to Tim-3 was detected by immunoprecipitation. LPS-primed U937 and THP1 transfected with Flag-tagged Tim-3 vector or control vector were stimulated with HMGB1 in the presence of control immunoglobulin (Ctrl-Ig) or mAb to Tim-3 (a-Tim-3), followed by immunoprecipitation with anti-HMGB1 or anti-Flag. Binding between HMGB1 and Tim-3 was observed in LPS-primed U937 and THP1 cells, and the a-Tim-3 inhibited its binding with HMGB1 (Figure 4F). Immunofluorescence also showed that Tim-3 and HMGB1 were colocalized in Tim-3+ CD4 T cells treated with LPS (Figure 4G). These findings suggested that Tim-3 might be a putative receptor for HMGB1 in Tim-3+ CD4 T cells during infection.

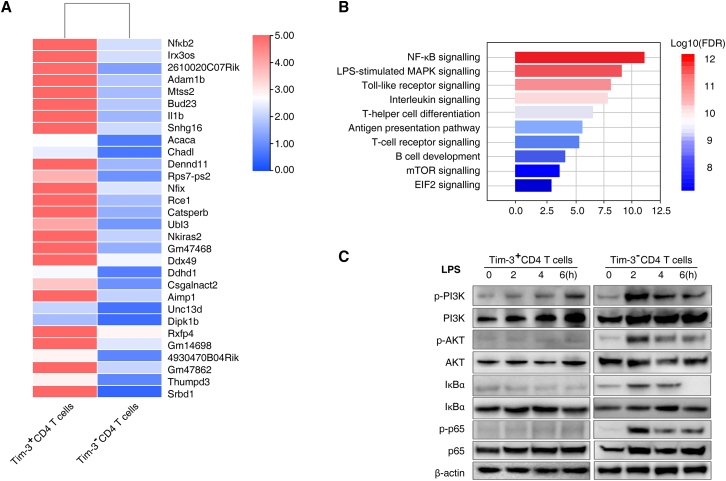

Tim-3 blocking in CD4 T cells induced the activation of NF-κB/TNF-α signaling pathway in sepsis-induced immunosuppression

To determine the mechanism of Tim-3+ CD4 T cells in septic immunosuppression, we performed RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis of Tim-3+ CD4 T cells and Tim-3– CD4 T cells isolated from CLP second hit mice. We identified differentially expressed genes between Tim-3– CD4 T cells and Tim-3+ CD4 T cells (Figure 5A and Data S2). Compared to Tim-3+ CD4 T cells, Tim-3– CD4 T cells exhibited increased activation of NF-κB signaling, LPS-stimulated MAPK, Toll-like receptor signaling, interleukin signaling, and T helper cell differentiation pathways (Figure 5B). Signal transduction of Tim-3 was reported to continuously activate NF-AT and NF-κB during inflammation, promoting T cell overactivation and eventual exhaustion.30,31 Therefore, we assessed the phosphorylation of key proteins of the NF-κB/TNF-α signaling pathway in Tim-3+ and Tim-3– CD4 T cells treated with LPS to simulate the inflammatory response in sepsis. The results showed that phosphorylation of PI3K, AKT, IκBα, and p65 was significantly increased 2 h after LPS simulation and gradually decreased after 4–6 h in Tim-3– CD4 T cells (Figure 5C). However, the inflammatory response did not activate the phosphorylation of PI3K, AKT, IκBα, and p65 in Tim-3+ CD4 T cells (Figures 5C and 5D). These results indicated that activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway in Tim-3+ CD4 T cells was inhibited by the inflammatory response to sepsis and that the release of inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-6, was also inhibited, resulting in sepsis-induced T lymphocyte "exhaustion" and immunosuppression. Taken together, these results demonstrated that the NF-κB signaling pathway mediates the regulation of HMGB1-Tim-3-dependent septic immunosuppression.

Figure 5.

Expression of Tim-3 on CD4 T cells regulates septic immunosuppression through the NF-κB/TNF-α pathway

(A) Heatmap of the top 30 upregulated genes in Tim-3– CD4 T cells compared to Tim-3+ CD4 T cells isolated from CLP second hit mice. (B) Enriched gene ontology functions of upregulated genes in Tim-3– CD4 T cells. Upregulated genes were enriched in NF-κB signaling, LPS-stimulated MAPK, and Toll-like receptor signaling. (C) Western blot analysis of the indicated protein expression in Tim-3+/Tim-3– CD4 T cells in response to treatment with 100 ng/mL LPS for 0, 2, 4, or 6 h.

Sepsis non-surviving patients have higher proportion of Tim-3-positive CD4 T cells than surviving patients

Next, we examined the clinical correlation between the proportion of Tim-3+ CD4 T cells and sepsis severity. We investigated a cohort of 36 patients diagnosed with sepsis for more than 14 days, including 30 surviving sepsis patients and six non-surviving patients. These patients were diagnosed according to the definition of the Third International Consensus on Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3).32 The demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients are shown in Table S3. There was no significant difference in age, sex, infection site, or bacterial type between surviving patients and non-surviving patients. As expected, the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score in surviving patients was lower than that in non-surviving patients (Table S3). Furthermore, there was a significant difference in the proportion of Tim-3-positive CD4 T cells between the two groups. The proportion of Tim-3-positive cells in non-surviving patients was significantly higher than that in surviving patients (p < 0.001). These findings further support the correlation between the proportion of Tim-3-positive CD4 T cells and the severity of septic immunosuppression. The proportion of Tim-3-positive cells may be used as a biomarker to predict immunosuppressive-induced mortality in sepsis.

Discussion

Sepsis is initially caused by pathogen invasion, so the premise and basis of sepsis treatment is to effectively eliminate the pathogens that have invaded the body. In the case of unknown pathogens, a lack of targeted therapeutic drugs, and/or drug resistance, the only way to eliminate pathogens is to rely on the immune system.33 Immunocytes play an important role in pathogen clearance. Increasing evidence shows that functional defects in T cells, especially CD4+ T cells, are the key reason underlying the inadequate clearance of pathogens in septic pathological conditions. Mechanisms of septic immunosuppression include the functional depletion of effector CD4+ T cells, a decrease in initial CD4+ T cell diversity, and an increase in Treg cells. Effector CD4+ T cells not only directly remove pathogens but also mediate the activation of CD8+ T cells and the class conversion of immunoglobulins. Their functional depletion is not only the direct reason for inadequate pathogen clearance in sepsis patients but is also the reason for repeated infection in sepsis patients. Therefore, it is of great significance to elucidate the molecular mechanism of CD4+ T cell exhaustion under the pathological conditions of sepsis and to clarify the role of repeated infection.34 Tim-3 was initially identified as a T cell exhaustion marker in cancer and chronic infection. Some studies have focused on the role of Tim-3 expression in lymphocytes during sepsis. Xia et al. investigated the effects of Tim-3 and PD-1 on T lymphocytes in septic patients. Blockade of the Tim-3 signaling pathway contributed to the release of IL-10 and TNF-α by T lymphocytes in septic patients. In the septic process, Tim-3 played crucial roles in the immune response of T lymphocytes.35 A clinical study showed that expression of TIM-3 and LAG-3 was elevated on CD4+ T cells in septic patients and LAG-3 was elevated on CD8+ T cells at the onset of acute phase of sepsis.17

We used a mouse CLP Streptococcus pneumoniae second hit model as the immunosuppressive model of sepsis for two reasons. First, S. pneumoniae is one of the most common opportunistic pathogens and causes severe hospital-acquired pneumonia in immunocompromized patients.36,37 Second, the adaptive immune response mediated by CD4+ T cells plays a critical role in controlling S. pneumoniae infection.38 Our results demonstrated that the proportion of Tim-3+ CD4 T cells in PBMCs of sepsis immunosuppression patients was higher than that in PBMCs from healthy volunteers. Furthermore, through the analysis of CD4 T cell proliferation, inhibitory marker expression, and cytokine secretion ability, the results suggest that the expression of Tim-3 is related to the severity of CD4 T cell exhaustion. We further observed the effects of conditional knockout of Tim-3 on CD4 T cells (Cd4CreTim-3fL/fL mice) and Tim-3 systemic knockout (Tim-3−/− mice) on sepsis-associated mortality.39 The results revealed that there was no difference in the mortality of the CLP first hit model but that it does reduce mortality in the CLP second hit immunosuppressive model. Blood biochemical measurements of heart, kidney, and liver enzymes revealed a protective role of Tim-3 conditional knockout on CD4 T cells and Tim-3 systemic knockout in a sepsis immunosuppressive model. However, no significant difference was detected in the levels of major inflammatory cytokines at the serum level. This result better explains the divergent effect of blocking Tim-3 in sepsis. Previous treatment to block Tim-3 in sepsis was ineffective, possibly due to it being inhibited in the septic immune inflammatory phase. Instead, Tim-3 should be inhibited during the septic immunosuppressive phase because its inhibition is ineffective during the hyperinflammatory phase.

Tim-3 has many ligands in immune and inflammatory responses, such as Gal-9, HMGB1, CEACAM-1, and Ptdser. Our study verified that Gal-9 is not a ligand for Tim-3 on CD4 T cells during sepsis. Next, we investigated the potential interaction between HMGB1 and Tim-3. The results demonstrated that Tim-3 had a relatively strong binding affinity for HMGB1, similar to the known HMGB1 receptor RAGE. Tim-3 and HMGB1 were also colocalized in Tim-3+ CD4 T cells treated with LPS. These findings suggest that Tim-3 is a putative receptor for HMGB1 in Tim-3+ CD4 T cells during sepsis. RNA-seq analysis suggested that NF-κB may be an important signaling pathway of Tim-3-mediated CD4 T cell exhaustion. Further analysis elucidated that Tim-3 regulates key protein phosphorylation in the NF-κB/TNF-α pathway during sepsis.

A large number of preclinical and clinical studies have demonstrated that immunosuppression plays a detrimental role in sepsis.40 Inhibitor therapy targeting immune checkpoints, such as PD-1, PD-L1, BTLA, and Tim-3, which may reverse innate and adaptive system hyporesponsiveness during sepsis, is a new strategy of immunosuppressive therapy for sepsis. In our research, we showed that the proportion of Tim-3+ CD4 T cells in surviving patient PBMCs was significantly lower than that in nonsurviving patients. Therefore, the proportion of Tim-3+ CD4 T cells is related to the severity of septic immunosuppression. The proportion of Tim-3-positive cells can be used as a biomarker to predict immunosuppressive-mediated mortality in sepsis. Our study demonstrates that expression of Tim-3 is elevated on CD4 T cells in patients with septic immunosuppression and that inhibition of Tim-3 reduces mortality in septic immunosuppressive mice. Therefore, our study provides a new therapeutic target for sepsis immunosuppression.

Materials and methods

Patient samples

Peripheral blood from 20 sepsis patients and 20 healthy volunteers was obtained from the Third Affiliated Hospital of Army Medical University. CD4+ T lymphocytes were isolated using a flow cytometry sorting (MoFlo Astrios EQ, Beckman) system. Collection of samples was performed with the approval of the Ethics Committee at the Third Affiliated Hospital of Army Medical University (Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT01713205.). Sepsis was confirmed according to the Third International Consensus Definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3).32 Written informed consent was obtained from the patients or their next of kin before enrollment, including the collection of relevant clinical data. Patient confidentiality was preserved in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) under the age of 18 and (2) preexisting respiratory, cardiovascular, hepatic, renal, immunological, or hematological disease.

Animals

C57BL/6, Cd4cre, Tim-3fL/fL, and Tim-3−/− mice were purchased from the Shanghai Model Organisms Center. TIM-3 conditional knockout in CD4 T cells mice (Cd4creTim-3fL/fL) was generated from Cd4cre and Tim-3fL/fL mice. Animal experiments were performed according to the protocols for the Use of Experimental Animals approved by the Ethics Committee of Army Medical University. All mice were maintained in the animal facility of Daping Hospital, Army Medical University. Before experiments, all mice were acclimatized for 1 week. Mice of both sexes were used in the study. Age- and sex-matched (8–12 weeks) controls were used in each experiment.

Sepsis first hit model: cecal ligation and puncture

CLP surgery was performed according to Rittirsch et al.41 Mice were anesthetized using ketamine (80 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg), and an incision was made from the midline of the abdomen. One-third of the distal cecum was ligated using 3-0 silk sutures and punctured once using 18Ga needles. Next, some of the intestinal contents were allowed to flow out through the puncture site. The cecum was replaced into the abdomen, and the incision was closed. Then, 1.0 mL of 0.9% normal saline was injected subcutaneously, and the mouse was placed into a 37°C heat preservation box to recover. Analgesia (buprenorphine, 0.05 mg/kg) was administered 6 h and 18 h after the operation.

Sepsis second hit model: Streptococcus pneumoniae second hit

Four days after CLP surgeries, surviving mice were administered S. pneumoniae (Sp) (#bio00005, Biobw, Beijing) as a sepsis second hit model. Forty microliters of Sp (5 × 108 CFU) suspension was slowly injected intranasally and was observed to be aspirated upon inhalation. The control group consisted of mice that were identically treated except that 0.9% normal saline was intranasally administered. The survival rate was observed for 7 days after pneumonia induction.

RNA sequencing and analysis

CD4 T cells from sepsis patients and healthy volunteers and Tim-3– CD4 T cells and Tim-3+ CD4 T cells from CLP mice were sorted using flow cytometry. Total RNA was extracted using an RNeasy Plus Kit (Qiagen, Germany), and 1 μg RNA was used as input for RNA sample preparation. RNA-seq strand-specific libraries were constructed using the VAHTS Total RNA-seq (H/M/R) Library Prep Kit (Vazyme, China). Cluster was generated by cBot after the library was diluted to 10 pM and then sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform (Illumina, USA). Library construction and sequencing were performed by Sinotech Genomics (Shanghai, China). Gene ontology analysis was performed for biological process, cellular component, and molecular function. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis was performed using the enrich R package (http://www.genome.ad.jp/kegg). Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were classified according to the official classification of KEGG annotation results and enriched in the path function using Phyper.

Flow cytometry analysis

Erythrolysis was performed immediately after peripheral blood collection from patients with sepsis and healthy volunteers. PBMCs were stained for 30 min at 4°C with monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) diluted in PBS. The mAbs used were Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-human Tim-3 (EPR20767, #ab233060, Abcam), Alexa Fluor 647 Anti-CD4 antibody (EPR6855, #ab196147, Abcam), PE/Cy7-conjugated anti-human CD3 (UCHT1, #ab81992, Abcam), Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse Ki67 (SP6, #ab281847, Abcam), phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-mouse LAG3 (C9B7W, #ab272044, Abcam), FITC-conjugated anti-mouse 2B4 (244F4, #ab95805, Abcam), allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated anti-mouse Tim-3 (RMT3-23, #ab272267, Abcam), anti-mouse CD4 (EPR19533, #ab183686, Abcam), and anti-mouse CD3 (RM0027-3B19, #ab56313, Abcam). Isotype control immunoglobulins (IgG) were used as controls. After washing twice with PBS containing 2% fetal cattle serum, the cells were analyzed by flow cytometry in a FACS Coulter Beckman EPICS XL (Beckman, USA).

Immunoblotting and coimmunoprecipitation

For immunoblotting, cell lysis buffer (#FNN0021, Invitrogen) with protease inhibitor cocktail (#78438, Promega), phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (#78440, Promega), and 1 mM Na3VO4 was used for cell lysis. Antibodies against phospho-PI3K ((Tyr458)/p55 (Tyr199), 1:1,000, #17366), PI3K (1:1,000, #4255), phospho-AKT (1:1,000, (Ser473) (D9E), #4060), AKT (1:1,000, #9272), p-p65, phospho-p65 (1:1,000, Ser468, #3039), p65 (1:1,000, #6956), and β-actin (1:1,000, #3700) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (CST). Phospho-IκBα (1:1,000, Ser36, #ab133462) and IκBα (1:1,000, #ab97783) were purchased from Abcam. HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (#7076, CST) and HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (#7074, CST) were used as secondary antibodies. The blots were analyzed using a ChemiDoc Touch Imaging System (Bio-Rad, USA). Image Lab software was used to analyze the band intensities. For coimmunoprecipitation (Co-IP), antibodies against Gal-9 (1:1,000, #3535-GA-050) and HMGB1 (1:1,000, #MAB16901) were purchased from R&D Systems. Antibodies against Tim-3 were purchased from GeneTex (1:1,000, #GTX54055). Antibodies against control immunoglobulin were purchased from Beckman-Coulter (1:1,000, #731705).

RT-PCR

According to the manufacturer's instructions, total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Plus Kit (#74134, Qiagen). One microgram of RNA was used for cDNA synthesis with an iScript cDNA Synthesis kit (#1708890, Bio-Rad). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using synthesized cDNA, primers, and SsoFast EvaGreen Supermix (#172–5204, Bio-Rad). Target gene expression was calculated using the ddCt method relative to the expression of the housekeeping gene β-actin or GAPDH. Data are shown as the relative quantity (RQ), and the control cell RQ was set to one.

Cytokine assay

According to the manufacturer's instructions, a Proteome Profiler Array Mouse XL Cytokine Array Kit (#ARY028, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, USA) was used for the detection of mouse serum cytokines. In brief, captured antibodies spotted on nitrocellulose membranes bind to target proteins appearing in the serum. Biotinylated antibodies captured specific proteins that were visualized using chemiluminescence detection reagents. The intensity of spots was analyzed by Quick Spots Image Analysis Software (Western Vision Software).

Cytokine ELISA

For analysis of the production of cytokines, IL-1β (#MLB00C), TNF-α (#MTA00B), IL-6 (#D6050), and IL-10 (#M1000B) in supernatants obtained from specific cells were quantified using ELISA kits according to the manufacturer's instructions (R&D Systems). For analysis of Gal-9 (#EM1059) and HMGB1 (#EM0382) in homogenate of thymus, spleen, lung, liver, and kidney were quantified using ELISA kits according to the manufacturer's instructions (FineTest, Wuhan, China).

Hematoxylin and eosin staining

Fixed lung tissues were embedded in paraffin for sectioning (5.0 μm) and then stained with hematoxylin and eosin for histopathology analysis. The stained slides were imaged using an Axio Zoom v16 imaging system (Zeiss) with five fields per section and five sections per sample.

Measurement of the Tim-3-HMGB1 interaction

Expression vectors of HMGB1 (pET28b-HMGB1-Full and pET28b-GST) were introduced into Chinese hamster ovary cells. Recombinant proteins were purified using a histidine-tagged protein purification kit (#IP999, R&D Systems). The plastic plate was coated with recombinant Tim-3 (#1529-TM, R&D Systems), RAGE (#1179-RG, R&D Systems), or Gal-9 (#3535-GA, R&D Systems) protein, and then biotin-labeled HMGB1 was loaded at different concentrations. The binding capacity of biotinylated HMGB1 to RAGE or Gal-9 was detected by colorimetric analysis (450 nm).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study protocol was approved by the Ethics and Protocol Review Committee of the Army Medical University (No. TMMU2012009). Informed consent was obtained from all patients or their next of kin.

Consent for publication

All authors consent for the publication.

Resource availability

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or in Supplemental information. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Dong-po Jiang, Dr. Lianyang Zhang, and J.Z., Army Medical University, and Dr. Dingyuan Du, Chongqing Emergency Medical Center, for the collection of the blood samples. This study was supported by the Chongqing Special Project for Academicians (cstc2020yszx-jcyjX0004), the Projects of the State Key Laboratory of Trauma, Burns and Combined Injury (SKLYQ201901), the Training Plan for Innovation Ability on the Frontiers of Military Medical Research (2019CXJSB014), and the Chongqing Special Project for Epidemic Prevention Doctors (2020FYYX239).

Author contributions

S-Y.H. and D-L. were the primary researchers of this study. J-Z., Q-W., L-B.G., G-X.Q., J-C.Q., and D-L.W. were involved in the collection of blood samples and clinical data. H-C.Z. and J-D. performed the technical work. L-Z. and J-X.J. planned the study, and L-Z. wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of interests

All authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2021.12.013.

Contributor Information

Jianxin Jiang, Email: jiangjx@cta.cq.cn.

Ling Zeng, Email: zengling_1025@tmmu.edu.cn.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Rudd K.E., Johnson S.C., Agesa K.M., Shackelford K.A., Tsoi D., Kievlan D.R., Colombara D.V., Ikuta K.S., Kissoon N., Finfer S., et al. Global, regional, and national sepsis incidence and mortality, 1990-2017: analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 2020;395:200–211. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32989-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mira J.C., Gentile L.F., Mathias B.J., Efron P.A., Brakenridge S.C., Mohr A.M., Moore F.A., Moldawer L.L. Sepsis pathophysiology, chronic critical illness, and persistent inflammation-immunosuppression and catabolism syndrome. Crit. Care Med. 2017;45:253–262. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Der Poll T., Van De Veerdonk F.L., Scicluna B.P., Netea M.G. The immunopathology of sepsis and potential therapeutic targets. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2017;17:407–420. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fattahi F., Ward P.A. Understanding immunosuppression after sepsis. Immunity. 2017;47:3–5. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gotts J.E., Matthay M.A. Sepsis: pathophysiology and clinical management. BMJ. 2016;353:i1585. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karakike E., Giamarellos-Bourboulis E.J. Macrophage activation-like syndrome: a distinct entity leading to early death in sepsis. Front. Immunol. 2019;10:55. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hotchkiss R.S., Monneret G., Payen D. Sepsis-induced immunosuppression: from cellular dysfunctions to immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013;13:862–874. doi: 10.1038/nri3552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sprung C.L., Annane D., Keh D., Moreno R., Singer M., Freivogel K., Weiss Y.G., Benbenishty J., Kalenka A., Forst H., et al. CORTICUS Study Group Hydrocortisone therapy for patients with septic shock. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;358:111–124. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clark M.A., Plank L.D., Connolly A.B., Streat S.J., Hill A.A., Gupta R., Monk D.N., Shenkin A., Hill G.L. Effect of a chimeric antibody to tumor necrosis factor-alpha on cytokine and physiologic responses in patients with severe sepsis--a randomized, clinical trial. Crit. Care Med. 1998;26:1650–1659. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199810000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin M.D., Badovinac V.P., Griffith T.S. CD4 T cell responses and the sepsis-induced immunoparalysis state. Front. Immunol. 2020;11:1364. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jensen I.J., Sjaastad F.V., Griffith T.S., Badovinac V.P. Sepsis-induced T cell immunoparalysis: the ins and outs of impaired T cell immunity. J. Immunol. 2018;200:1543–1553. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1701618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor M.D., Fernandes T.D., Kelly A.P., Abraham M.N., Deutschman C.S. CD4 and CD8 T cell memory interactions alter innate immunity and organ injury in the CLP sepsis model. Front. Immunol. 2020;11:563402. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.563402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu J., Paul w.e. CD4 T cells: faults, functions, and faults. Blood. 2008;112:1557–1569. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-078154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inoue S., Suzuki K., Komori Y., Morishita Y., Suzuki-Utsunomiya K., Hozumi K., Inokuchi S., Sato T. Persistent inflammation and T cell exhaustion in severe sepsis in the elderly. Crit. Care. 2014;18:R130. doi: 10.1186/cc13941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Monney L., Sabatos C.A., Gaglia J.L., Ryu A., Waldner H., Chernova T., Manning S., Greenfield E.A., Coyle A.J., Sobel R.A. Freeman GJ, Kuchroo VK. Th1-specific cell surface protein Tim-3 regulates macrophage activation and severity of an autoimmune disease. Nature. 2002;415:536–541. doi: 10.1038/415536a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anderson A.C., Joller N., Kuchroo V.K. Lag-3, Tim-3, and TIGIT: Co-inhibitory receptors with specialized functions in immune regulation. Immunity. 2016;44:989–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boomer J.S., Shuherk-Shaffer J., Hotchkiss R.S., Green J.M. A prospective analysis of lymphocyte phenotype and function over the course of acute sepsis. Crit. Care. 2012;16:R112. doi: 10.1186/cc11404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xia Q., Wei L., Zhang Y., Sheng J., Wu W., Zhang Y. Immune checkpoint receptors Tim-3 and PD-1 regulate monocyte and T lymphocyte function in sepsis patients. Mediat. Inflamm. 2018;2018:1632902. doi: 10.1155/2018/1632902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao Z., Jiang X., Kang C., Xiao Y., Hou C., Yu J., Wang R., Xiao H., Zhou T., Wen Z., et al. Blockade of the T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain protein 3 pathway exacerbates sepsis-induced immune deviation and immunosuppression. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2014;178:279–291. doi: 10.1111/cei.12401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang X., Jiang X., Chen G., Xiao Y., Geng S., Kang C., Zhou T., Li Y., Guo X., Xiao H., et al. T cell Ig mucin-3 promotes homeostasis of sepsis by negatively regulating the TLR response. J. Immunol. 2013;190:2068–2079. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boomer J.S., To K., Chang K.C., Takasu O., Osborne D.F., Walton A.H., Bricker T.L., Jarman S.D., Kreisel D., Krupnick A.S., et al. Immunosuppression in patients who die of sepsis and multiple organ failure. JAMA. 2011;306:2594–2605. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gentile L.F., Cuenca A.G., Efron P.A., Ang D., Bihorac A., McKinley B.A., Moldawer L.L., Moore F.A. Persistent inflammation and immunosuppression: a common syndrome and new horizon for surgical intensive care. J. Trauma Acute. Care Surg. 2012;72:1491–1501. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318256e000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bouras M., Asehnoune K., Roquilly A. Contribution of dendritic cell responses to sepsis-induced immunosuppression and to susceptibility to secondary pneumonia. Front. Immunol. 2018;9:2590. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wherry E.J. Molecular signature of CD8+ T cell exhaustion during chronic viral infection. Immunity. 2007;27:670–684. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhu C., Anderson A.C., Schubart A., Xiong H., Imitola J., Khoury S.J., Zheng X.X., Strom T.B., Kuchroo V.K. The Tim-3 ligand galectin-9 negatively regulates T helper type 1 immunity. Nat. Immunol. 2005;6:1245–1252. doi: 10.1038/ni1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuchroo V.K., Dardalhon V., Xiao S., Anderson A.C. New roles for TIM family members in immune regulation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008;8:577–580. doi: 10.1038/nri2366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chiba S., Baghdadi M., Akiba H., Yoshiyama H., Kinoshita I., Dosaka-Akita H., Fujioka Y., Ohba Y., Gorman J.V., Colgan J.D., et al. Tumor-infiltrating DCs suppress nucleic acid-mediated innate immune responses through interactions between the receptor TIM-3 and the alarmin HMGB1. Nat. Immunol. 2012;13:832–842. doi: 10.1038/ni.2376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Mingo Pulido Á., Hänggi K., Celias D.P., Gardner A., Li J., Batista-Bittencourt B., Mohamed E., Trillo-Tinoco J., Osunmakinde O., Peña R., et al. The inhibitory receptor TIM-3 limits activation of the cGAS-STING pathway in intra-tumoral dendritic cells by suppressing extracellular DNA uptake. Immunity. 2021;54:1154–1167. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2021.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou H., Wang X., Zhang B. Depression of lncRNA NEAT1 antagonizes LPS-evoked acute injury and inflammatory response in alveolar epithelial cells via HMGB1-RAGE signalling. Mediat. Inflamm. 2020;2020:8019467. doi: 10.1155/2020/8019467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee J., Su E.W., Zhu C., Hainline S., Phuah J., Moroco J.A., Smithgall T.E., Kuchroo V.K., Kane L.P. Phosphotyrosine-dependent coupling of Tim-3 to T-cell receptor signalling pathways. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2011;31:3963–3974. doi: 10.1128/MCB.05297-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zheng Y., Li Y., Lian J., Yang H., Li F., Zhao S., Qi Y., Zhang Y., Huang L. TNF-α-induced Tim-3 expression marks the dysfunction of infiltrating natural killer cells in human esophageal cancer. J. Transl. Med. 2019;17:165. doi: 10.1186/s12967-019-1917-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singer M., Deutschman C.S., Seymour C.W., Shankar-Hari M., Annane D., Bauer M., Bellomo R., Bernard G.R., Chiche J.D., Coopersmith C.M., et al. The Third International Consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3) JAMA. 2016;315:801–810. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kumar V. Immunometabolism: Another road to sepsis and its therapeutic targeting. Inflammation. 2019;42:765–788. doi: 10.1007/s10753-018-0939-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oami T., Watanabe E., Hatano M. Suppression of T cell autophagy results in decreased viability and function of T cells through accelerated apoptosis in a murine sepsis model. Crit. Care Med. 2017;45:e77–e85. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xia Q., Wei L., Zhang Y., Sheng J., Wu W., Zhang Y. Immune checkpoint receptors Tim-3 and PD-1 regulate monocyte and T lymphocyte function in septic patients. Mediat. Inflamm. 2018;2018:1632902. doi: 10.1155/2018/1632902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muenzer J.T., Davis C.G., Dunne B.S., Unsinger J., Dunne W.M., Hotchkiss R.S. Pneumonia after cecal ligation and puncture: a clinically relevant "two-hit" model of sepsis. Shock. 2006;26:565–570. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000235130.82363.ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu T., Yang F., Xie J., Chen J., Gao W., Bai X., Li Z. All-trans-retinoic acid restores CD4+ T cell response after sepsis by inhibiting the expansion and activation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Mol. Immunol. 2021;136:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2021.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Unanue E.R. Intracellular pathogens and antigen presentation-new challenges with Legionella pneumophila. Immunity. 2003;18:722–724. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00145-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aghajani K., Keerthivasan S., Yu Y., Gounari F. Generation of CD4CreER(T2) transgenic mice to study development of peripheral CD4-T-cells. Genesis. 2012;50:908–913. doi: 10.1002/dvg.22052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Patil N.K., Guo Y., Luan L., Sherwood E.R. Targeting immune cell checkpoints during sepsis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017;18:2413. doi: 10.3390/ijms18112413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rittirsch D., Huber-Lang M.S., Flierl M.A., Ward P.A. Immunodesign of experimental sepsis by cecal ligation and puncture. Nat. Protoc. 2009;4:31–36. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.