Summary

The prelimbic cortex (PrL) is involved in the organization of operant behaviors, but the relationship between longitudinal PrL neural activity and operant learning and performance is unknown. Here, we developed deep behavior mapping (DBM) to identify behavioral microstates in video recordings. We combined DBM with longitudinal calcium imaging to quantify behavioral tuning in PrL neurons as mice learned an operant task. We found that a subset of PrL neurons were strongly tuned to highly specific behavioral microstates, both task and non-task related. Overlapping neural ensembles were tiled across consecutive microstates in the response-reinforcer sequence, forming a continuous map. As mice learned the operant task, weakly tuned neurons were recruited into new ensembles, with a bias towards behaviors similar to their initial tuning. In summary, our data suggest that the PrL contains neural ensembles that jointly encode a map of behavioral states which is fine-grained, continuous, and grows during operant learning.

Keywords: Learning, operant conditioning, behavioral sequence, prelimbic cortex, neural ensembles, miniScope, longitudinal calcium imaging, deep learning, deep behavior mapping, cognitive maps

eTOC Blurb

Zhang et al. reveal that prelimbic (PrL) neurons encode a complex reward-driven behavior as a continuous sequence, rather than signaling only the most salient task events. Other PrL neurons encode non-task behaviors, while many others possess weak / unstable tuning but may be recruited to represent newly learned behaviors.

Introduction

The organization and execution of even simple behaviors places diverse cognitive demands on an individual, which engage multiple brain systems (Bradfield et al., 2015; Desrochers et al., 2015; Dezfouli and Balleine, 2019; Markowitz et al., 2018). The prefrontal cortex is linked across species to high-level aspects of action selection and behavioral organization that termed executive functions (Diamond, 2013; Menon and D'Esposito, 2021), but these functions are highly interrelated and therefore difficult to differentiate (Fusi et al., 2016; Le Merre et al., 2021).

Within the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), the prelimbic cortex (PrL) is implicated in high-level control of behavior by loss-of-function studies linking it to the selection of appropriate behavioral strategies on the basis of contextual information (Marquis et al., 2007; Ragozzino et al., 2003; Trask et al., 2017). Many PrL neurons display activity time locked to specific behaviors (Chang et al., 1997; Euston and McNaughton, 2006; Horst and Laubach, 2013), but similar actions in different circumstances may evoke different patterns of PrL activity (Chang et al., 1998; Woodward et al., 2000). Recent work has linked the PrL to action selection using the rat’s own behavior as context (Thomas et al., 2020). This evidence suggests that PrL neurons encode relationships between behavioral states, but traditional experimental procedures provide little information about the laboratory animal’s behavioral state outside of a narrow temporal window around certain discrete action (e.g., a lever press). Such responses represent only one part of a larger behavioral program that comprises a flexible sequence of behaviors across a broader timescale (Silva et al., 2019; Timberlake, 1994), and these behaviors are likely to be correlated with task variables. This makes it difficult to differentiate between representation of the animal’s behavioral state and representation of abstract task variables, and to characterize the scope of the PrL’s relationship to behaviors.

In this manuscript, we addressed this problem by developing a novel method called deep behavior mapping (DBM) to derive a fine-grained map of behavioral microstates from video tracking data. Our analysis mapped operant behavior as a flexible sequence of microstates, capturing variations in the timing and order of task-related behaviors, as well as a variety of non-task behaviors. This approach allowed us to identify task-related behaviors performed spontaneously outside of the normal task context, and to quantify the evolution of a conditioned behavior across learning in greater detail. We combined DBM with a custom miniScope system (Barbera et al., 2016; Liang et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2019) to record calcium activity of PrL neurons longitudinally while mice learned to lever press to receive palatable food pellets (the operant reinforcer). We identified overlapping ensembles of PrL neurons tuned to operant task-related and non-task related behaviors, forming a detailed map of both task-related and spontaneous behaviors, where the overlap between ensembles corresponded to the probability of transitions from one behavioral state to another. PrL neurons’ behavioral tuning explained significant trial-to-trial variability that would otherwise appear as noise or non-goal-directed behavior.

We showed that when mice learned the operant task, neurons with weak and unstable behavioral tuning were recruited to extend the behavioral map to encompass the new behavior, and that neurons with initial weak tuning to behaviors resembling the operant response (prior to mice’s first exposure to the lever) were more likely to be recruited. Our findings are consistent with the hypothesis that the PrL maintains a detailed and stable map of the relationships between behavioral states, which grows by recruitment from a pool of neurons with weak, unstable tuning.

Results

Longitudinal Calcium Imaging Across Learning

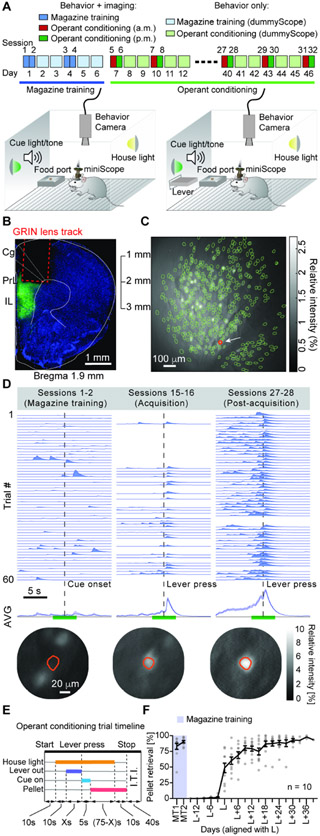

To track the formation and evolution of neural ensembles in the PrL across learning, we used a custom miniScope system (Barbera et al., 2016; Liang et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2019) to record calcium activity of PrL neurons while mice learned a food self-administration task (Figure 1A). We used adeno-associated virus (AAV) expressing GCaMP6f, a genetic encoded fluorescence calcium indicator (Chen et al., 2013), to label PrL principal neurons. After implantation of a gradient index (GRIN) lens in the PrL (Liang et al., 2018) (Figure 1B, Figure S1), we used a miniScope to image calcium activity of PrL neurons during both magazine training and operant conditioning. A representative field of view from a single recording session is shown (Figure 1C, movie S1). We identified neurons tuned to specific behavioral events (e.g., lever-press) and tracked them across 46 days (Figure 1D).

Figure 1. Longitudinal miniScope calcium imaging across operant conditioning.

(A) Experimental timeline and apparatus. Left illustration: configuration during food magazine training; no lever is presented. Right illustration: lever presentation during operant training. (B) Sample histological image showing GCaMP6f expression (green) with GRIN lens positioned in the PrL. Scale bar: 1 mm. (C) Sample image from miniScope calcium video, with detected neurons outlined in green. Scale bar: 100 μm. (D) Representative image of a PrL neuron (bottom panels, also indicated in red circle in C) on days 1, 22, and 40, with traces showing calcium signal around cue onset / lever press (no traces shown for no-response trials), with session average trace shown below. Scale bar: 20 μm. (E) Trial structure during operant training. (F) Response rates for all post- magazine training days aligned to day L. Abbreviations and definitions: MT, magazine training; L: first day at/above response criterion. See also Figure S1 and Table S1.

During training, mice were given 60 trials per day, spread across a morning and an afternoon session (Figure 1A). Each trial lasted 110 seconds and was cued by illumination of the house light. In the initial magazine training phase, mice received a noncontingent reward of a 20-mg food pellet after a 5-s tone-light cue. In the subsequent food self-administration training phase, a lever was presented 10-s after house light illumination; responses on this lever were reinforced by delivery of the 5-s tone-light cue followed by the pellet (Figure 1E). We denoted the first imaging day in which mice successfully completed at least 10% of “Lever-press” trials as day “L”, with L ± X representing the Xth day before or after day L (Figure 1F, Figure S2). We also defined a “pre-acquisition” phase of training as from the beginning of contingent reinforcement to just before the onset of consistent lever pressing (days L-9 through L-3), “early acquisition” phase as the first two imaging days with response rate ≥ 10% (days L and L+3), and a “post-acquisition” stage during which mouse behavioral performance was stable (from day L+6 onward).

Deep Behavior Mapping: Identifying Behavioral Microstates

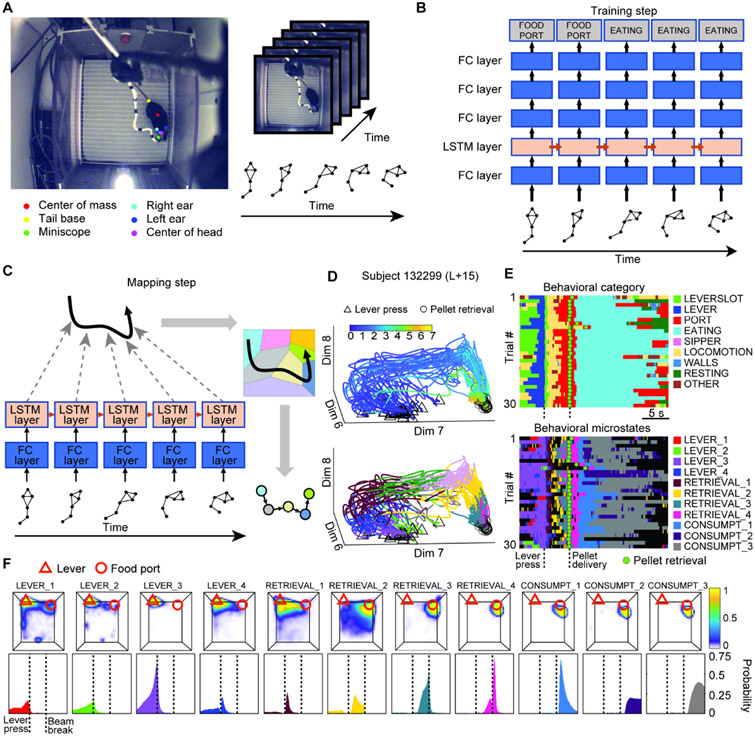

Quantifying operant behavior by the rate and timing of designated “response” behaviors (e.g., lever-press) is useful in studying factors that influence behavior, and remains widely used in the field. However, this approach does not allow the identification of all the successive behavioral links in the operant behavior (Chang et al., 1997; Skinner, 1938; Thrailkill and Bouton, 2015; Thrailkill et al., 2016; Woodward et al., 1999; 2000) that may be relevant to interpreting the activity of PrL neurons, making it difficult to determine the relationship between activity of neural ensembles in PrL to operant behavior. To overcome this limitation, we developed DBM, a method to extract a detailed representation of mouse behavior from video recordings. We first used DeepLabCut (Mathis et al., 2018) to track mice’s location and posture across video frames (Figure 2A). We then used the mouse’s location and the timing of experimental events (e.g., lever-press, reward retrieval) to derive a set of behavior pseudo-labels (e.g., lever interaction, reward acquisition, locomotion, etc.; Table S1).

Figure 2. Deep Behavior Mapping: Learning a detailed representation of behavior from video recordings.

(A) Pose estimation using DeepLabCut. Colored dots denote body part labels applied by trained model. Body part positions across successive frames form a posture sequence. (B) Schematic of Deep Behavior Mapping (DBM) model and training procedure. A neural network containing a long short-term memory (LSTM) layer (light orange box) is trained to predict data-derived pseudo-labels (gray boxes) using pose data sequences (bottom) as input. Network is depicted ‘unrolled’ across multiple timesteps. (C) Mapping mouse behavior using the trained DBM model. The LSTM layer’s output (dashed gray arrows) is represented as a trajectory in a 10-dimensional space, which is then quantized into a sequence of discrete states (behavioral microstates, depicted as colored circles at lower right). (D) Snippets of trajectories through behavioral state space (dim: subset of output dimensions). Each line depicts the trajectory from lever press (triangle markers) to food reward retrieval (circle markers) in a single trial. Top, continuous color scale indicates time elapsed since lever press (triangle markers). Bottom, segments of trajectories are colored to indicate assignment to different microstates. (E) Example raster of experimenter-defined training labels (Top, see also Table S1 and S2) and extracted microstates (Bottom). Only task-related behavioral microstates are shown in the bottom panel to reduce color confusion. Other microstates are left black. Rasters are aligned to lever press. (F) Localization of task-related microstates in space and time. Top row: Spatial distribution of mouse head position for indicated microstates in the operant chamber, red triangle and circle indicate lever and food port position, respectively. See also Figure S3. Bottom row: Probability of microstate occurrence from 10s before lever press to 10-s after food reward retrieval. Interval between lever press and food reward retrieval was compressed to remove variability in latency to retrieve the food pellet.

Next, we trained an artificial neural network with a 10 node long short-term memory (LSTM) (Hochreiter and Schmidhuber, 1997) layer to predict these pseudo-labels using sequences of pose data as input (Figure 2B, see STAR Methods), a method known as self-supervised learning (Misra and Maaten, 2020). When we analyzed video recordings using the trained model; we extracted the outputs of the LSTM layer on each frame and discarded the network’s final output (i.e. predicted pseudo-labels), mapping an mouse’s behavior on a given trial as a trajectory through a 10-dimensional latent space (Figure 2C).

We used vector quantization with the k-means algorithm to map these trajectories as sequences of discrete states (k=50), with the mouse’s behavior in each frame assigned to one of 50 categories (Figure 2C), which we termed ‘behavioral microstates’. Thirty snippets of actual trajectories (from lever press to food reward retrieval) and their assignment to discrete microstates are shown in Figure 2D. We characterized the spatial and temporal distributions of the 50 microstates (Figure 2F, Figure S3) and assigned descriptive labels based on examination of video recordings. Eleven of these microstates corresponded specifically to task-related behaviors, capturing behavioral sub-sequences and trial-to-trial variations that were not apparent in the behavior pseudo-labels derived from location and event timing (Figure 2E).

Of the 11 task-related microstates, 4 were related to the lever: The microstate we termed LEVER_1 coincided with approach to the lever and head extension towards the lever, LEVER_2 corresponded to lever sniffing / investigative behaviors, LEVER_3 to focused lever interaction / manipulation (typically by biting / grabbing with mouth), and LEVER_4 to head-raising and orienting behaviors performed before and after the lever press. Another 4 microstates corresponded to successive phases of the behavioral sequence linking a successful lever press to obtaining the palatable food pellet: In RETRIEVAL_1, the mouse quickly oriented away from the lever and began moving to the food port, followed by RETRIEVAL_2 in which the mouse approached the food port with snout extended toward the pellet cup. RETRIEVAL_3 corresponded to focused sniffing / probing / gnawing directed at the food port prior to pellet delivery, while RETRIEVAL_4 corresponded to grabbing the pellet and retracting the upper body to bring the pellet to the mouth. CONSUMPT_1, 2, and 3 indicate successive phases of pellet consumption. Each task-related microstate’s spatial and temporal distribution are shown in Figure 2F. Non-task microstates corresponded to behaviors such as rearing (n=3), locomotion (n=7), interacting with the chamber’s water-spout (n=1), climbing the chamber’s walls (n=1), or grooming (n=1), as well as several exploratory behaviors and fine movement (Figure S3, Table S2).

Neural Ensembles Tuned to Task-Related Behavioral Microstates

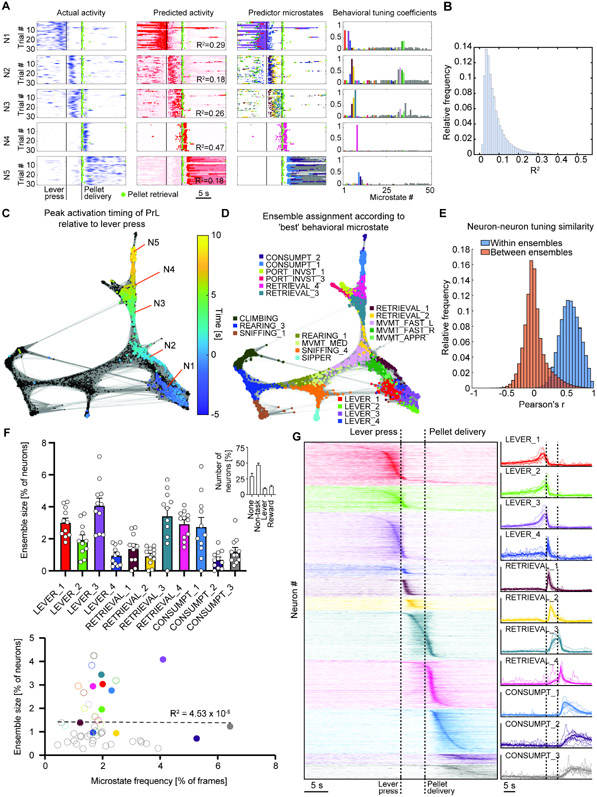

Using the detailed representation of behavioral microstates provided by DBM, we quantified the behavioral tuning of PrL neurons. We identified behavioral microstates that reliably predicted an increase in a neuron’s activity, and calculated microstate tuning coefficients describing the neuron’s average activity for each microstate (see STAR Methods). The activity of five behaviorally tuned PrL neurons around the time of the lever press or food consumption is shown in Figure 3A (first column), along with predicted activity based on microstate tuning profiles (Figure 3A, second column), rasters showing the timing of the occurrence of individual predictor microstates (Figure 3A, third column), and each example neuron’s microstate tuning profile (Figure 3A, fourth column). We predicted each neuron’s activity using the microstate tuning coefficients for significant predictor microstates. We quantified the strength of behavioral tuning as the R2 value (proportion of explained variance) for predicting a neuron’s activity solely based on the current microstate identified by DBM. Most behaviorally tuned neurons (n=33071) had only weak behavioral tuning (median R2 = 0.0613, inter-quartile range = 0.059, Figure 3B), but a smaller subset of neurons displayed stronger behavioral tuning, with 11% of behaviorally tuned neurons having an R2 value ≥ 0.15. These results show that behavioral microstates identified by DBM predict significant trial-to-trial variability in neural activity.

Figure 3. Evaluating behavioral tuning of PrL neurons using behavioral microstates.

(A) Behavioral tuning of example PrL neurons (1 neuron per row of plots). First column: Neural activity across trials within a single session, from 10-s before lever press to 20-s after. Vertical lines indicate time of lever press and pellet delivery (+5-s after lever press), and circular markers denote food reward retrieval. Second column: Neural activity predicted from microstate labels, for neurons in previous column. Third column: Rasters showing occurrence of microstates associated with increased activity of example neurons. Color code matches bars in 4th column. For First, Second and Third columns, X-axis represents time in seconds. Scale bar is 5 s. Fourth column: Microstate tuning profiles for example neurons. X-axis indicates microstate index from 1 to 50, task-related microstates are 1 through 11. Nonzero bars correspond to microstates that are significant predictors of the neuron's activity, bar height indicates average deconvolved signal during each microstate (% of max). Bar color matches microstate color code in Fig. 2. (B) Histogram of R2 values for neurons with significant behavioral tuning. Mean R2=0.08. (C) 100-nearest neighbor graph of PrL neurons after acquisition of food self-administration (all mice, days 25-40). Nodes represent behaviorally tuned neurons, with edges connecting each neuron with its 100 nearest neighbors (correlation distance, neurons with neighborhood diameter >0.25 excluded). Color scale indicates timing of neuron's activity peak within a window from 5-s before lever press (blue) to 10-s after (yellow). N1 to N5 labels indicate the location of the 5 example neurons in A. (D) Same graph as C, but nodes colors indicate ensemble assignment according to a neuron's 'best microstate'. Color code matches Fig. 2 and 3A. (E) Histogram of pairwise behavioral tuning similarity values for neurons in the same ensemble (blue bars) or between different ensembles (red bars). Intra-ensemble similarity values are significantly greater than between-ensemble values (Wilcoxon rank-sum test, p<0.0001). (F) Top: Average size of task-relevant ensembles, bar represents group average from all mice, individual open circle represents data from each mouse; inset: each bar represents the number of neurons (as fraction of total detected neurons) associated with operant response behavior (Lever), food reward retrieval/consumption behaviors (Reward), other behaviors (Non-task), or not associated with any microstate (None). Bottom: Scatterplot of frequency of the associated behavioral microstate (% of frames, X axis) vs. ensemble size (% of behaviorally tuned neurons, Y axis). Task-related and/or strongly represented microstates are plotted in solid circles and colored according to previously used color code (e.g., Figure 2; Figure 3C); other microstates are denoted by open markers. (G) Activity around lever press and food reward delivery averaged across trials for neurons in task-related ensembles. Left: color indicates ensemble membership. Right: mouse-wise ensemble average traces are shown as thin lines and grand average traces as bold lines.

Next, we identified task-related neural ensembles in the post-acquisition stage. We first calculated profile similarity scores between behaviorally tuned neurons using correlation similarity. A nearest-neighbor graph of highly similar neurons from the post-acquisition phase is shown in Figure 3C, colored to indicate the timing of neurons’ activity peaks within the range from 5 s prior to lever press to 10 s after (with food retrieval usually occurring at around +7 s). This result shows that behaviorally tuned neurons corresponding to every step of the task were observed in the PrL.

We then assigned neurons to neural ensembles according to the behavioral microstate to which they were most strongly tuned (Figure 3D). The resulting neural ensembles preserved the similarity relationships between neurons (Figure 3E). Of all detected PrL neurons post-acquisition, we found that 27.2% were not associated with any specific behavioral microstate, 48.3% were associated with non-task behavioral microstates, 10.0% were associated with lever press-associated microstates, and 14.5% were associated with food reward retrieval / consumption microstates (Figure 3F, top inset, Table S3).

Ensemble sizes for specific microstates ranged from under 1% to ~4% of all detected neurons (Figure 3F, top, Table S3), and did not depend on the frequency of microstate occurrence (Figure 3F, bottom, Table S3). The peak activity of neurons within task-related ensembles covered contiguous time ranges within the task, with all the task-related ensembles together covering the entire task sequence (Figure 3G), mapping out sequential relationships between behavioral microstates in a food self-administration task.

Formation of Task-Related Neural Ensembles Across Learning

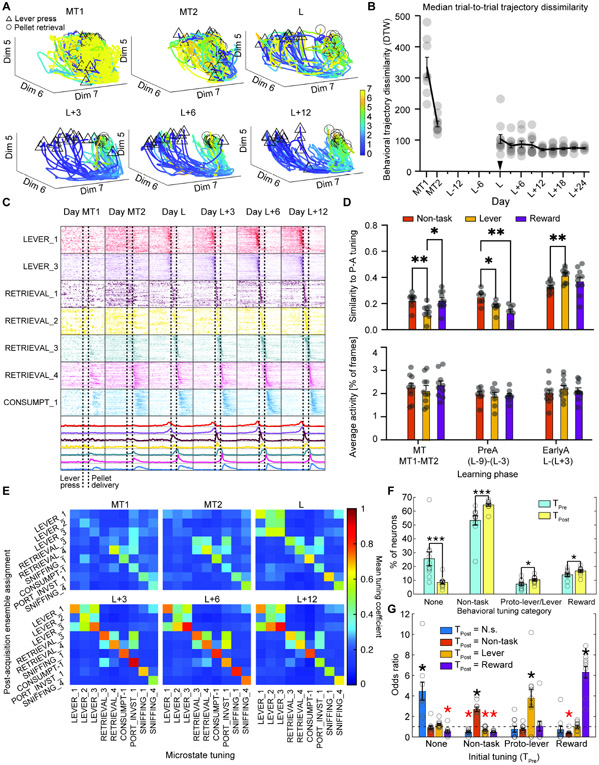

We next examined the emergence of the food self-administration behavior and the stabilization of the behavioral sequence surrounding the lever press and food reward retrieval. Mice’s behavioral microstate trajectories were more disorganized during magazine training, and gradually became more organized during acquisition of operant food self-administration (Figure 4A). A mixed-effects ANOVA of the average trial-to-trial variability of mice’s behavioral trajectories across imaging days (Figure 4B) showed a significant effect of time (F(3.79,31.43) = 43.7, p<0.001), while a second analysis restricted to the post-acquisition period (from day L+6 onward) was not significant (F(2.52,19.74) = 1.3, p>0.05), indicating that the mice’s behavioral sequences stabilized by the post-acquisition period.

Figure 4. Longitudinal analysis of behavioral tuning in PrL neurons.

(A) Example snippets of DBM behavior trajectories at different points across learning for one mouse. Each line corresponds to a trajectory through behavior space on a single trial, beginning at cue onset/lever press (triangle markers) and ending at acquisition of food self-administration (circle markers). Color scale indicates time (in seconds) elapsed since cue onset. (B) Stabilization of the mouse’s’ behavior across learning. Days before / after learning (plus magazine training (MT)) shown on X axis. The median pairwise distance between trajectories on different trials (measured by dynamic time warping algorithm) is plotted as a black line (± SEM) with individual mouse means shown as gray circles. See also Figure S2, S3 and S4. (C) Activity of post-acquisition task-related ensembles visualized at different timepoints across learning. Each row corresponds to a single neuron's activity (averaged across trials) on the indicated day. Ensemble means for each day shown at bottom in same order as above. Vertical lines indicate timing of lever press and food pellet delivery. (D) Emergence of behavioral tuning of post-acquisition ensembles in earlier phases of training, grouped by tuning category. Top: Average similarity between neuron’s tuning and its post-acquisition tuning during the indicated phase of training, i.e. higher values indicate greater resemblance to final tuning. (* p<0.05, ** p<0.01, Tukey’s HSD). Bottom: As in top panel but showing average activity (% active frames) across phases of training. (E) Partial tuning profiles for ensemble neurons at different days labeled above each subpanel across learning. Abbreviations: MT; magazine training; L represents day L. Each matrix row corresponds to an ensemble, and each column contains tuning coefficients for a different behavioral microstate, so that the element in the ith row and jth column is the average tuning coefficient for the jth microstate among neurons in the ith ensemble. Color scale indicates magnitude of tuning coefficients. (F) Percentage of neurons with no significant behavioral tuning (“None”) or tuning in one of the three categories used in 4D during the initial magazine training phase prior to food self-administration training (TPre, blue bars) or in the post-acquisition phase (TPost, yellow bars). Bars show average percentage across mice, gray circles denote individual mice. (G) Effect of initial tuning category (TPre, shown on X axis) on post-acquisition tuning (TPost, categories denoted by bar color). Y axis shows odds ratio, e.g., blue bars indicate the effect of different types of initial tuning (as indicated by X axis) on odds of having no significant tuning post-acquisition; orange bars indicate effect of initial tuning (X axis) on odds of having non-task tuning post-acquisition, etc. (* p<0.05, FDR corrected, red markers indicate decreased odds).

We then examined the evolution of task-related neural ensembles in the PrL. We grouped neurons according to their largest microstate coefficient in the post-acquisition phase and assigned their post-acquisition behavioral tuning to one of three categories: ‘Non-task’ (neurons tuned to task-irrelevant behaviors), ‘Lever’ (neurons tuned to lever-related behaviors), and ‘Reward’ (neurons tuned to food reward retrieval / consumption behaviors). We then followed these neurons backwards through time to the beginning of the experiment and examined the development of their behavioral tuning. Trial averaged rasters of the activity of neurons grouped by post-acquisition ensemble are shown in Figure 4C, while an analysis of the development of behavioral tuning in different categories of behaviorally tuned neuron is shown in Figure 4D (top).

An ANOVA (training phase X tuning category) of neurons’ similarity to their final tuning in different phases of the experiment showed an effect of training phase (F(2.56, 63.9) = 157.6, p<0.0001) and a training phase X tuning category interaction (F(6,75) = 15.0, p<0.0001), indicating that neurons’ final behavioral tuning emerged at different times for different categories of behavioral tuning. Post-hoc tests (Tukey’s multiple comparisons) for differences between tuning categories showed that during the magazine training phase, ‘Lever’ neurons were less similar to their final state than neurons in other tuning categories (p<0.01 vs. Non-task, p<0.05 vs. Reward). In the pre-acquisition phase (day L-9 to L-3), when mice had not learned to press the lever and consequently received few or no rewards, both ‘Lever’ neurons and ‘Reward’ neurons displayed lower similarity to their final tuning compared to ‘Non-task’ neurons (p<0.05 for Lever vs. Non-task, p<0.01 for Reward vs Non-task). But in the early acquisition phase, this difference was reversed for Lever neurons (Lever > Non-task, p<0.01) and disappeared for Reward neurons. A mixed-effects analysis of the average activity of behaviorally tuned neurons (Figure 4D, bottom) showed only an effect of training phase (F(2.61,65.14) = 3.7, p<0.05), and post-hoc tests did not show significant differences between groups. Figure 4E depicts average tuning profiles (for a subset of microstates) at various points across training, showing the development of tuning and tuning overlap between ensembles.

These findings indicate that neural ensembles tuned to reward-related behaviors emerge as soon as mice are first given the opportunity to consume the food reward, rather than upon the imposition of a response contingency. In contrast, ensembles tuned to lever-related behaviors develop their lever-related tuning later, upon acquisition of the operant behavior. Furthermore, neurons tuned to behaviors the mice had no opportunity to perform (i.e., food reward ensembles during pre-acquisition phase) are not less active than other ensembles, suggesting that behavioral tuning may be shaped in part by inhibition.

Initial Tuning Biases but Does Not Determine Final Tuning

We also investigated the effect of neurons’ initial tuning during the magazine training phase on their tuning later in training. Although there was no lever present during magazine training, DBM nonetheless assigned the mice’s behavior to a lever-associated microstate during this phase (Figure S4). The spatial distribution of the lever-press associated microstates during magazine training was mainly concentrated around the lever port, food port, sipper tube, and walls (Figure S3, left), leading us to conclude that the label indicated general exploration behaviors bearing some similarity to the behaviors later adapted to press the lever. We therefore considered neurons tuned to these behaviors during magazine training to possess “Proto-lever” tuning.

We identified neurons whose activity could be tracked from the magazine training phase to the post-acquisition phase and categorized their behavioral tuning at both timepoints into four broad categories: No detectable tuning (None), tuning to non-task behaviors (Non-task), “Proto-lever” tuning, and “Reward” (i.e., food reward retrieval and consumption). The proportion of neurons in each category at each timepoint is shown in Figure 4F. We found that neurons with initial tuning in any of the four categories were significantly more likely than other neurons to have the same type of tuning in the experiment’s post-acquisition phase (Expressed as Odds ratio (OR), None: OR = 4.46 ±0.88; Non-task: OR = 2.7 ±0.23; Proto-lever→Lever: OR = 3.78 ±0.86; Reward: OR = 6.32 ±0.56), as shown in Figure 4G.

These results indicate that the formation of behaviorally tuned ensembles of PrL neurons from weakly tuned neurons is probabilistic, with some bias due to initial tuning, but that the tuning of the ensembles is relatively stable once formed. The fact that this bias was observed for proto-lever neurons (i.e., that neurons tuned to lever press-like behaviors prior to mice’s first exposure to the lever were more likely to have lever-related behavioral tuning after acquisition) suggests that PrL encoding of information about behavioral state may be independent of the behavior’s conditioned associations with food reward or other external stimuli.

Discussion

Here we investigated how a diverse set of operant task-related and non-task behaviors are represented in the PrL. Our results indicate that neurons in PrL encode detailed information about the mouse’s behavioral microstate via the activity of behaviorally tuned neurons. Different behavioral microstates were associated with the activity of different ensembles of PrL neurons, and the ensembles corresponding to behaviors that frequently followed one another in a sequence tend to overlap. Our results also show that new ensembles arise by recruitment of weakly tuned neurons, with preferential recruitment of neurons tuned to behaviors related to the newly learned behavior (Figure 4G). These findings expand our understanding of the PrL’s function by providing a view of PrL function in a broader behavioral context, encompassing not only conditioned behavior but also unconditioned behaviors not motivated by external rewards, as well as behaviors associated with conditioned responding but performed outside of that context. We propose that encoding information about the relationships between behavioral states is a significant part of the PrL’s function.

Neurons in the PrL have been shown to display mixed selectivity, in which neurons’ activity is selective for specific conjunctions of stimuli, time, place, and other variables, without having a generalized relationship to any one of those parameters (Fusi et al., 2016; Rigotti et al., 2013). Mixed selectivity in PrL neurons may in part reflect action selectivity for highly context-dependent behaviors or behavioral states: animals can display subtle variations in behavior and movement that are correlated with task conditions or cognitive parameters, and the activity of some PrL neurons is linked to such micro-behaviors (Cowen and McNaughton, 2007; Euston and McNaughton, 2006). There is evidence that behavioral variability is a strong determinant of neural activity across much of the cortex (Musall et al., 2019), and that activity in PrL in particular can be driven by task-correlated variations in behavior (Cowen and McNaughton, 2007; Euston and McNaughton, 2006; Horst and Laubach, 2013). It is possible that further improvements in methods for tracking laboratory animals’ behavioral state may reveal a correspondence between the aspects of behavioral state tracked by PrL neurons and the high-dimensional task strategy representations that have been argued to account for mixed selectivity (Badre et al., 2021).

The behavioral task used in the current study presented mice with the opportunity to perform a response to receive a food reward, but only permitted one response per trial (during the interval in which the response lever was available; Figure 1E). The lever (as well as the houselight) therefore represents a contextual stimulus that indicates when it is appropriate to perform task-related behaviors. Given the known relevance of the PrL to contextual control of behavior (Thomas et al., 2020; Trask et al., 2017) and the ability of a lever inserted into the chamber to act as a Pavlovian cue with its own conditioned associations (Holland et al., 2014; Robinson and Flagel, 2009), we might have expected to observe that the activity of some PrL neurons corresponded to contextual cues / occasion setters. These cues could include the presence of the lever or the houselight, or to the presentation of the tone-light cue which was consistently associated with impending food reward in both magazine training and food self-administration training, but we did not.

One explanation is that we only recorded the activity of excitatory neurons. Interneurons likely play an important role in shaping the behavioral tuning of excitatory PrL neurons: a recent study found that tentatively identified mPFC interneurons displayed higher levels of selectivity for the identity of a conditioned stimulus than putative excitatory neurons (Xing et al., 2020). Future experiments examining the interplay of local inhibitory interneurons and excitatory projection neurons across contexts and behavioral states may reveal that PrL interneurons are responsible for mediating the effects of context on selection of appropriate behavioral transitions. Such functions may also involve interplay of circuits in PrL and the closely related infralimbic (IL) division of the mPFC, which is also implicated in contextual control of behavior (Bossert et al., 2011; Bossert et al., 2012; Madangopal et al., 2021; Roughley and Killcross, 2021; Smith et al., 2012). Both the IL and the PrL are implicated in the organization of a variable cue-directed response sequence (Risterucci et al., 2003). Therefore, contextual control of behavior is ultimately likely to involve both PrL and IL, particularly as well-learned behaviors become habitual (Gourley and Taylor, 2016). The functions of different PFC subregions are interdependent (Le Merre et al., 2021), and assembling a complete picture may not be possible until functional studies (e.g. calcium imaging, electrophysiology) have caught up to loss-of-function studies in the breadth and depth of the behavioral phenomena surveyed.

In interpreting the results of the present study, we note that PrL/IL lesions can cause response behaviors to occur in contexts where they are not appropriate (Risterucci et al., 2003) or disrupt behavioral strategies used to facilitate correct responding across a delay period (Chudasama and Muir, 1997), and that the activity of PrL neurons has been linked particularly to variations in behavior that are correlated with task state or with upcoming behaviors (Cowen and McNaughton, 2007; Euston and McNaughton, 2006). This evidence is consistent with the hypothesis that the behaviorally tuned neurons identified in our study serve a function related to the organization of behaviors into sequences, rather than the selection of specific actions based on sensory information per se. In this respect, our conclusions parallel those of Thomas et al. (2020), viz. that PrL mediates the conditioning of one behavior upon the preceding behavior, or, more broadly, selectively facilitates transitions between behavioral states (in a manner that may be influenced by contextual stimuli). According to this interpretation, the overlap of ensembles corresponding to successive steps of a behavioral sequence (as visualized in Figure 3C and Figure 3D) may be seen as encoding the relationship between those behavioral states and providing a ‘map’ of possible behavioral sequences.

Our results emphasize the importance of detailed information about laboratory animal behavior for interpreting neural data. The use of DBM to extract behavioral microstates from video tracking data obtained using DeepLabCut (Mathis et al., 2018) enabled us to identify trial-to-trial variations in the timing and sequence of task-related behaviors. This revealed that the activity of some PrL neurons is much less “noisy” than it initially appears (e.g., Figure 3A), and that some neurons are in fact tuned to non-task behaviors when their activity might otherwise appear random (Figure 3D). The use of LSTM (Hochreiter and Schmidhuber, 1997) enables DBM to integrate information about the mouse’s pose across time, so that behaviors which feature similar movements but differ in their sequence and timing are represented separately, allowing DBM to distinguish a wider variety of behavioral states. This approach is suited to exploring the tuning of PrL neurons, since PrL is known to encode action sequences in a context-dependent manner (Chang et al., 1998). However, refining our understanding of precisely what aspects of context are relevant to the encoding of behavioral state in PrL may require the development of hierarchical models capable of mapping behavioral states at multiple levels of abstraction. Self-supervised learning (Misra and Maaten, 2020), in which a deep learning model learns a useful representation of input data without the use of “ground-truth” labels by training the model on a “pretext task” (e.g. learning a representation of birdsong from unlabeled recordings by training to predict geographic region tags associated with each recording), will likely prove to be a valuable tool for future research in this area.

In summary, by extracting a richly detailed representation of behavior with DBM, we showed that overlapping ensembles of PrL map behavioral states in an operant task. The activity of these neural ensembles formed a continuous, stable representation of sequentially related behavioral microstates, both operant task- and non-task-related. We tracked the recruitment of weakly tuned neurons into new behaviorally tuned neural ensembles as the mice acquired an operant lever press response, and by identifying the early behavioral antecedents of lever pressing behavior we demonstrated that neurons with tuning to lever press-like exploratory behaviors were more likely to be recruited. We propose that the PrL neural ensembles encode context dependent sequential relationships between behavioral microstates, enabling the formation of complex and flexible behavioral sequences.

STAR★ METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Dr. Da-Ting Lin (da-ting.lin@nih.gov)

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents

Data and code availability

All datasets and custom MATLAB scripts will be available upon reasonable request. DBM codes are available via GitHub (https://github.com/AlexDenman/DeepBehaviorMapping; DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.5710721).

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Male C57BL/6J wild-type mice, all of ages 3-4 months (~25 g), were used for our experiments. All mice were single housed in a reverse light/dark schedule (8 am off/ 8 pm on) and provided with food and water ad libitum. Behavioral testing was performed during the dark cycle. All experimental procedures and animal care were performed in accordance with the guidelines of Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, the Intramural Research Program, National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health.

METHOD DETAILS

Viral injection

To image GCaMP6f fluorescence in the prelimbic cortex (PrL), we first injected AAV1-CaMKII-GCaMP6f (University of Pennsylvania Vector Core) into the PrL. Mice were anaesthetized with 2% isoflurane in oxygen at a flow rate of 0.4 liter/min and mounted on a stereotactic frame (Model 962, David Kopf Instruments), while mice body temperature was maintained at 37°C using a temperature control system (TCAT-2DF, Physitemp). Sterile ocular lubricant ointment (Dechra Veterinary Products) was applied to mouse corneas to prevent drying. Mouse scalp fur was shaved and the skin was cleaned with 7.5% betadine and 70% alcohol three times. A hole was drilled through the right side of the skull above the injection site (A/P: +1.9 mm; M/L: −0.3 mm) using a 0.5-mm diameter round burr on a high-speed rotary micro drill (19007- 05, Fine Science Tools). A total of 500 nl of virus (a titer of 6.75e12 GC/mL) was injected using the stereotactic coordinates (A/P: +1.9 mm, M/L: −0.3 mm, D/V: −1.7 mm, 0° angle) at a rate of 25 nl/min with a micro pump and Micro4 controller (World Precision Instruments). After injection, the injection needle was kept in the parenchyma for 5 min before being slowly withdrawn. The hole on the skull was then sealed with bone wax, and the skin was sutured. After surgery, Neosporin ointment was applied to the closed skin incision line. Mice were subcutaneously injected with buprenorphine (0.05 mg/kg) and returned to their home cage to recover from anesthesia in a 37°C isothermal chamber (Lyon Technologies, Inc). Mice were maintained on ibuprofen (30 mg/mL in water) ad libitum for at least 3 days post-surgery.

GRIN lens implantation

One week after viral injection, a 1-mm diameter gradient index (GRIN) lens (GRINTECH GmBH) was implanted in the mouse brain above the PrL as previously described (Liang et al., 2018). Briefly, mice were anesthesized with ketamine/xylazine (ketamine:100mg/kg, xylazine:15mg/kg), and a 1 mm-diameter craniotomy was generated in the right hemisphere above the coordinates (A/P: +1.9 mm, M/L: −0.7 mm). Freshly prepared artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) was continuous applied to the exposed tissue throughout the surgery to prevent brain tissue dehydration. The brain tissue above the PrL, along a direction of a 10° laterally shifted angle into a depth of 1.8 mm was precisely removed using vacuum suction through a 30-gauge blunted needle attached to a custom-constructed three-axis motorized stereotactic device, modified from a commercial stereotactic frame (Model 962, David Kopf Instruments). A MATLAB-based software was developed to control the movement of the stereotactic arm carrying the vacuum needle to remove the brain tissue automatically using a pre-defined trajectory (Liang et al., 2019). After brain tissue above PrL had been removed and the surgical site was clear of blood, a GRIN lens was slowly lowered into the PrL. The portion of the GRIN lens extending above the mouse skull was secured to the skull using dental cement (DuraLay). A protective plastic cap (0.2-mL PCR tube bottom) was glued on the skull using super glue (Loctite) to protect the exposed surface of the GRIN lens. Mice were subcutaneously injected with buprenorphine (0.05 mg/kg) and allowed to recover from anesthesia in a 37°C isothermal chamber. Mice were maintained on ibuprofen (30 mg/mL in water) ad libitum for at least 3 days post-surgery in their homecages.

Mounting miniScope

A custom-built miniScope (Barbera et al., 2016; Liang et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2019) was used to image GCaMP6f fluorescence. The miniScope weighs 2.4 grams and has approximately 1.1 mm × 1.1 mm maximum field of view with a cellular spatial resolution. About one month after the GRIN lens implantation, a base was mounted onto the mouse head. A custom miniScope mounting instrument constructed using three motorized translation stages (Thorlabs, constructed using three MTS50-Z8, one MTS50A-Z8, one MTS50B-Z8, one MTS50C-Z8, one CR1, and one GN05) was used to hold the miniScope (including main body and base). After achieving the in-focus position for the entire field of view, the miniScope base was fixed on the skull using dental cement. Subsequently, we attached the miniScope body to mouse head before each experiment and detached it after each experiment.

Food self-administration task

Apparatus

We trained mice in Med Associates mouse self-administration chambers (ENV-307W-CT, 21.59 cm × 18.08 cm × 12.7 cm) located inside sound-attenuating cubicles (ENV-022MD), fitted with electric fans and controlled by a Med Associates system. Each chamber had a plastic mesh on the stainless-steel grid floor and two operant panels on the left and right walls. The right panel of the chamber had a discriminative house light (ENV-315M) and food-paired retractable lever (ENV-312-2W). A press on this lever activated a tone-light cue (3000HZ, 70db) for 5s, and a 20-mg food pellet (Testdiet, #1811142) was then delivered to a food port located on the right side of the chamber. An inactive non-retractable lever (ENV-310W) and a bottle of water (ENV-350CW) were also mounted on the left panel of the chamber.

Dummy adaptation (7 days)

Mice were allowed to freely explore the chamber for 2 h per day for 7 days prior to magazine training. During this time, we mounted a dummy miniScope and cable on the heads of mice in the chamber prior to calcium imaging recording in order to adapt them to the imaging recording setup.

Recording procedures (imaging days)

Mice were imaged on the first day of magazine training, and every third day of training thereafter. On imaging days, mice were briefly and lightly anesthetized using isoflurane before the miniScope was mounted. We then waited 1 h for mice to recover before the first imaging trial. Each mouse received two sessions per day, one in the morning, the other in the afternoon with more than 2 h interval between the two sessions. Each session contained 30 trials and lasted 75 min. Behavior was recorded using a video camera controlled by software (Point Gray). The start of both calcium imaging and behavior recording was triggered by a TTL signal from the Med Associate software. The time stamps were also recorded for the synchronization of calcium imaging and behavioral video.

Magazine training (6 days)

On the first 6 days of training, the mice received two sessions of magazine training (30 trials/session) per day. One session was in the morning, the other one was > 2h later in the afternoon. During imaging sessions, the miniScope camera was turned on at the start of each trial. The house light was turned on 10 s after the start of the trial and stayed on for a total of 80 s. 40 s after house light on, a 5 s paired tone-light (3000 HZ, 70 db) cue was presented, followed by the delivery of a food pellet. At the end of each trial, the miniScope camera was turned off 10 s after house light off, followed by a 40 s intertrial interval. No active lever was available in the chamber at any time during magazine training. Mice were imaged during the first and fourth days of magazine training (Figure 1A). During non-imaging session, mice wore dummy miniScopes during training.

Operant training

From the 7th day of training onwards, mice received two operant conditioning sessions (30 trials/session) per day. One session was in the morning, the other one was > 2 h later in the afternoon. The miniScope camera was turned on at the start of each trial, and the house light was turned on 10 s after the start of the trial. The active lever was extended into the chamber 10 s after house light on. An active lever response (termed “successful trial”) led to the lever being retracted, and the 5 s tone-light cue presentation (3000 HZ, 70 db) followed by the delivery of a food pellet. If the active lever was not pressed within 60 s (termed “unsuccessful trial”), the lever was retracted, and house light was turned off 10 s later. Each trial would end 10 s after house light off and the miniScope camera was turned off at the end of trial. An intertrial interval period of 40 s was included between trials (Figure 1E). In non-imaging sessions, mice wore dummy miniScopes during training.

Histochemistry

After the completion of experiments, mice were deeply anesthetized by an overdose of ketamine (150 mg/kg) and xylazine (22.5 mg/kg), and perfused with phosphate buffer solution (PBS, PH 7.4) followed by a fixation buffer containing 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS. The brains were removed and post-fixed in 4% PFA at 4°C overnight. The brains were sectioned on a microtome and 30 μm brain slices were collected. These slices were then mounted, counterstained with DAPI (Thermo Fisher Scientific, D1306), and cover slipped. Fluorescent images were obtained through an Olympus VS120 scanner and analyzed using ImageJ (NIH).

Behavioral video analysis

Pose estimation (DeepLabCut)

We used the behavioral tracking tool DeepLabCut (Mathis et al., 2018) to track the mice’s movements during magazine training and operant training sessions. Six points were selected for tracking: the center of the mouse’s trunk, the base of the tail, the left and right ears, the center of the mouse’s head, and the top of the MiniScope. Using DeepLabCut’s labeling interface, we hand-labeled these six points in 258 frames taken from the behavioral video and trained a DeepLabCut model. We applied the trained model to all of the video recordings from the experiment, which yielded the estimated location of each of the tracked body parts in each frame (Figure 2A), as well as a confidence value ranging from 0 to 1 for each point, with occlusions of the tracked points reflected by lower confidence values. Because parts of the mouse’s head were sometimes occluded by the cable, we estimated the position of the head by averaging the locations predicted by DeepLabCut for 4 trackpoints: The left and right ears, the top of the miniScope, and the center of the head. For each frame, any trackpoints with a confidence score <0.95 were assumed to be occluded from view and were treated as missing data, as were trackpoints for which the predicted position differed by more than 100 pixels from the previous frame. The position of missing trackpoints was estimated by linear interpolation between the last known position and next. Body part X and Y coordinates were smoothed using a Gaussian with σ=1.667.

Deep Behavior Mapping

To extract information about mouse behavioral states from the transformed pose sequences, we used self-supervised learning (Misra and Maaten, 2020), a machine learning technique that avoids the use of hand-labeled data by training a model to use one part of the data to predict another. We defined rough behavioral categories based on mouse’s location and event timing and trained a deep neural network to predict these behavior categories on a frame-by-frame basis from mouse posture alone. The trained model was used for feature extraction and quantization to identify behavioral microstates.

Posture sequences

Mouse pose data, in the form of X and Y pixel coordinates, was transformed by taking the point-to-point distances between body parts in each frame (N = 15 with 6 body parts), combined with the distance between each body part and the positions of all body parts in the next frame (N = 36 with 6 body parts). The resulting 51 variables provide a rotation- and translation-invariant representation of mouse posture and movement in each video frame, so that mouse behavior over the course of a trial can be represented as a 51-dimensional time series with length equal to one less than the number of video frames captured between the first frame in which the mouse could be tracked and the last frame in which the house light was illuminated (typically around 890 frames, though sometimes fewer if the camera’s view was initially obstructed).

Experimenter-defined behavior categories

We defined 9 behavioral categories based on regions of interest (ROIs) within the experimental chamber, mouse velocity, and the timing of experimental events (e.g., lever press, food reward retrieval). A complete list is given in supplementary Table S1. Each video frame was assigned a label, producing a sequence of labels for each trial with length equal to the number of video frames captured.

Model training

We used a neural network model with 4 hidden layers: A fully connected layer (10 nodes, hyperbolic tangent activation), followed by a 10 node Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) layer, followed by two additional 10-node fully connected layers (10 nodes, rectified linear output function) and a final 9-node classification layer. All trials from all mice, across all imaging days (including magazine training) were used for training, except for 10% of trials held back for validation, for a total of 8,126 trials used for training and 873 trials held back for validation. For training, input posture sequences and the corresponding label sequences were divided into subsequences 100 frames or less in length, yielding a total of 73,124 training samples. We trained the network for approximately 27,000 iterations using the ADAM optimizer, with minibatch size = 2925.

Mapping

We evaluated the trained model on the full-trial posture sequences, taking the activations of the 10 nodes in the LSTM layer and discarding the outputs of the final classification layer, yielding a 10-dimensional time series with length equal to that of the input posture sequence. We concatenated the outputs from all trials and discretized the output using the k-means algorithm with k = 50, assigning each video frame to one of 50 categories, which we termed ‘behavioral microstates.’

Microstate characterization

We characterized behavioral microstates according to their spatial distribution (Figure S3), the timing of their occurrence relative to task events (Figure 2F), and visual examination of video recordings. We assigned behavioral microstates to five general categories: Task (n=11), food port (i.e. non-task related behaviors at the food port, n=3), exploration (n=15), locomotion (n=7), fine movement (n=11), and miscellaneous (n=3). Each microstate was further given a unique identifier and description (Table S2).

Calcium imaging data processing

Image processing and source extraction

Image sequences from single trials were background subtracted and then concatenated into a batch with all other image sequences from the same day. Further processing was performed using the CaImAn calcium image processing toolbox (Giovannucci et al., 2019), including rigid motion correction using the NormCorre algorithm and source extraction using the CNMF-E algorithm. CaImAn produced estimates of each candidate neuron’s footprint, deconvolved activity trace, calcium trace reconstructed from deconvolved activity, an estimated signal to noise ratio (SNR), and spatial correlation value (a measure of spatial consistency). We estimated of background noise for each candidate by taking the root mean square (RMS) of the residual signal after deconvolution, and thresholded each candidate’s deconvolved activity trace at 2.5 X the estimated noise level. We removed candidates with a SNR less than 4 or a spatial correlation value less than 0.4 from further analysis. We thresholded each candidate’s footprint at 1% of the maximum value and rejected candidates with fewer than 200 pixels or more than 1000 pixels. We rejected spurious ‘neurons’ resulting from imperfect motion correction by calculating the frame-by-frame correlation between a candidate’s activity trace and the magnitude of the motion correction vector and rejecting candidates with a correlation of 0.4 or greater. If any two spatially overlapping candidates had highly correlated activity, we rejected the candidate with lower signal quality (SNR / spatial correlation).

Neuron registration across imaging days

We aligned the spatial footprints of neurons recorded on different imaging days using a custom MATLAB script which removed the low-frequency components of the background images produced by CaImAn for two days with a Gaussian filter (σ = 12.375 pixels), followed by smoothing with another Gaussian (σ = 0.625 pixels), then registration using the MATLAB functions imregtform and imregdemons. Alignment was considered successful if the correlation of the aligned neuron footprint maps was at least 0.25. If a pair of days could not be aligned with this procedure, alignment was attempted using the footprint maps, and finally with the raw, un-filtered background image.

For each mouse, we constructed a graph with nodes representing imaging days and edges connecting pairs of imaging days that could be successfully registered, weighted according to the correlations between the filtered background images and the aligned neuron footprint maps. We selected a reduced set of linkages between days by iteratively computing the minimum spanning tree and removing the corresponding edges from the graph, and then constructing a new graph from the edges contained in all the previous minimum spanning trees. Registration of neurons was only performed for pairs of days connected by an edge in the resulting graph. The number of iterations was chosen to maximize the number of neurons that could be co-registered while minimizing the number of contradictory registrations (where a neuron recorded on one day was registered to more than one neuron on another day. For each selected pair of days, we matched each neuron with its 1st and 2nd nearest neighbors within 18 μm (if any) apart and calculated the correlation between their spatial footprints. We fit a pseudoquadratic discriminant classifier using the MATLAB function fitcdiscr for each mouse to separate 1st nearest neighbor pairs from 2nd nearest neighbor pairs according to their centroid distance and footprint correlation, assigning a score P1nn to each neuron pair indicating the predicted probability that a pair of neurons were 1st nearest neighbors. We then formulated the assignment of neurons as a linear assignment problem with 1-P1nn as the cost to match a pair of neurons and 0.01 as the cost of not matching a neuron, and solved this problem using the MATLAB function matchpairs. Chains of neurons matched across successive days were treated as single neurons tracked across time, except for cases where a chain included more than one neuron on the same day, in which case the entire group was excluded from longitudinal analyses.

Analysis of neural tuning

Microstate tuning calculation

We calculated a neuron’s behavioral microstate tuning coefficients by taking the neuron’s average activity for each microstate across the entire imaging day. We then predicted the neuron’s activity using the microstate tuning coefficients (i.e., the predicted activity for each frame was equal to the neuron’s tuning coefficient for whichever microstate the mouse was in during that frame) and calculated the R2 value. To test the significance of the R2 value we repeated the above procedure after reversing the temporal sequence of microstate labels for each trial and adding a random temporal shift of anywhere from 1 to 1100 frames (length of a single trial). This procedure was repeated 1000 times to generate a surrogate distribution of R2 values under the null hypothesis (i.e. that the neuron’s activity was uncorrelated with behavior). We calculated a p value for the observed R2 value by comparing it to the cumulative distribution of surrogate R2 values. After performing this calculation for all neurons in the dataset, we identified neurons with R2 significantly greater than zero with p<0.05, using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure to control the false discovery rate across all neurons in the dataset.

For neurons with R2 significantly greater than zero, we identified the specific microstate(s) for which the neuron’s activity was elevated by a similar method: We compared individual coefficients to the cumulative distribution of surrogate coefficients generated by the randomized time shifting procedure (see above) to generate a p value, then testing for significance at the p<0.05 level with the false discovery rate across the entire dataset controlled by the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure. For non-significant coefficients, we estimated the chance / background activity level as the median of the surrogate coefficients. We referred to the resulting 50 tuning coefficients (after substituting non-significant coefficients with the median time-shifted coefficient) for each neuron as that neuron’s behavioral tuning profile (Fig. 3A, 4th column).

Population tuning visualization

We visualized the distribution of behaviorally tuned PrL neurons in the space of possible tuning profiles by taking neurons recorded on imaging days 9 – 14 (experimental days 25 – 40) and finding each neuron's 100 nearest neighbors in behavioral tuning space using the correlation distance between neurons’ tuning profiles. We constructed a k-nearest neighbor graph with k=100, excluding neurons with a neighborhood size (i.e. distance to 100th nearest neighbor) greater than 0.25, shown in Figure 3C, 3D.

Longitudinal analysis

Analysis of behavior stabilization

We measured the stabilization of the operant behavior sequence across recording days using trajectory snippets (i.e., the 10-dimensional time series produced by the LSTM module of the trained DBM model) corresponding to the interval between lever press (or cue onset in magazine training) and food reward retrieval on each trial (as shown in Figure 4A). For each mouse, we calculated the pairwise distances between these 10-D trajectory snippets using dynamic time warping with the MATLAB function dtw, and took the median trial-to-trial trajectory distance for each mouse. These values were then averaged across mice for each recording day (Figure 4B).

Longitudinal ensemble analysis

We selected neurons that were recorded and tracked across multiple days, and for each day we calculated the similarity between the neuron’s tuning on that day and its tuning on all days from L+6 onwards (excluding the day for which the measure was being calculated, if applicable). We then averaged these values to obtain a general measure of the neuron’s similarity to its post-acquisition tuning on the specified day. We averaged these values within 3 general categories of neural tuning: Non-task (neurons tuned to non-task behaviors), Lever (neurons tuned to lever investigation / manipulation behaviors), and Reward (neurons tuned to food reward retrieval / consumption behaviors). The results are plotted across training phases in Figure 4D. We also calculated average tuning profiles for post-acquisition ensemble neurons at specific timepoints (Figure 4E).

Initial tuning analysis

We then selected neurons with recorded activity in both the initial magazine training phase and the post-acquisition phase of the experiment and categorized their tuning in each of those two phases using the same categories as in the previous analysis, plus the category “None” for neurons with no significant behavioral tuning. In the magazine training phase, since no response lever was present, we categorized neurons with tuning to lever-associated microstates as “Proto-lever” instead of “Lever”. We referred to neurons’ tuning category in magazine training as TPre, and their tuning category in the post-acquisition phase as TPost. We quantified the effect of TPre on TPost using the odds ratio (OR), so that an OR of 1 for a given TPre/TPost combination indicates that the odds of having the indicated TPost for neurons with the indicated TPre were the same as the odds for neurons having any other TPre, while values > 1 indicate that having the indicated TPre increased the odds of having the indicated TPost. The results are shown in Figure 4G.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Statistics

All reported sample numbers represented biological replicates. Of the 11 mice used in the study, 1 was not included in longitudinal analyses due to insufficient registered neurons. Technical issues resulted in missing data from one mouse on imaging day 25, one mouse on imaging day 43, and two mice on imaging day 46. Detailed information on the number of mice in different phases of the experiment is available in Figure S2. All data were presented as mean ± SEM unless otherwise specified. All statistical analyses were performed using Graphpad Prism (Graphpad) or MATLAB (Mathworks). Normality tests were performed prior to statistical tests. Parametric tests were used for data that passed normality test. Non-parametric tests were used data that did not pass normality test. Unless otherwise specified, all tests were two-sided, and statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. For detailed statistical results please refer to Table S3.

Supplementary Material

Movie S1. Imaging in PrL during operant conditioning, related to Figure 1.

Representative GCaMP6f imaging of mouse behavior recording (left) and calcium activity of PrL neurons (right) for one trial in post-acquisition period. Text on the top side of behavior movie indicates elapsed trial time in seconds. List of text on the left side of the behavior movie indicates task-relevant behavioral microstates, the larger size bold text right below the list as well as the colored one on the list indicate the behavioral microstate the mouse is in. Movie is played at 3x of recording speed. Scale bar at the lower left corner of the GCaMP6f panel is 100 μm.

Supplementary Table S3. Statistical procedures, related to Figure 3 and Figure 4. Excel spreadsheet containing detailed list of statistical tests used in text and figure legends.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial and Virus Strains | ||

| AAV1.CamKII.GCaMP6f.WPRE.SV40 | University of Pennsylvania Vector Core | AV-1-PV3435 |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| C57BL/6J mice | The Jackson Laboratory | 000664 |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| Matlab | Mathworks | https://www.mathworks.com/ |

| Graphpad Prism | Graphpad | https://www.graphpad.com/ |

| CaImAn | (Giovannucci et al., 2019) | https://github.com/flatironinstitute/CaImAn |

| Other | ||

| Miniature microscope (miniScope) for in vivo calcium imaging | (Barbera et al., 2016; Liang et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2019) | DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.5710817 |

| Automated surgical instrument for GRIN lens implantation | (Liang et al., 2019) | DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.5710828 |

| DeepLabCut | (Mathis et al., 2018) | https://github.com/AlexEMG/DeepLabCut |

| Deep Behavior Mapping | This work | DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.5710721 |

Highlights.

Self-supervised learning enables fine-grained analysis of behaviors in video data.

Prelimbic cortex neurons encode a detailed map of both task and non-task behaviors.

Overlapping ensembles represent each step of a reward-driven behavioral sequence.

Neurons with weak, unstable tuning are recruited to encode newly learned behaviors.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Genetically-Encoded Neuronal Indicator and Effector (GENIE) Project and the Janelia Research Campus of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) for generously allowing the use of GCaMP6 in our research; We would like to thank the Machine Learning Team of National Institute of Mental Health Intramural Research Program (NIMH IRP) for their consultation in optimizing our DBM algorithm; This work utilized the computational resources of the NIH HPC Biowulf cluster (http://hpc.nih.gov). We would like to thank Drs. Geoffrey Schoenbaum and Bruno Averbeck for critical reading of the manuscript. Funding: Research was supported by NIH/NIDA/IRP. YZ, NJB, and CTW are supported by Postdoctoral Fellowship from the Center on Compulsive Behaviors, National Institutes of Health. YL is supported by NIGMS COBRE 5P20GM121310-05.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Badre D, Bhandari A, Keglovits H, and Kikumoto A (2021). The dimensionality of neural representations for control. Curr Opin Behav Sci 38, 20–28. 10.1016/j.cobeha.2020.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbera G, Liang B, Zhang L, Gerfen CR, Culurciello E, Chen R, Li Y, and Lin DT (2016). Spatially Compact Neural Clusters in the Dorsal Striatum Encode Locomotion Relevant Information. Neuron 92, 202–213. 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.08.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossert JM, Stern AL, Theberge FR, Cifani C, Koya E, Hope BT, and Shaham Y (2011). Ventral medial prefrontal cortex neuronal ensembles mediate context-induced relapse to heroin. Nat Neurosci 14, 420–422. 10.1038/nn.2758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossert JM, Stern AL, Theberge FR, Marchant NJ, Wang HL, Morales M, and Shaham Y (2012). Role of projections from ventral medial prefrontal cortex to nucleus accumbens shell in context-induced reinstatement of heroin seeking. J Neurosci 32, 4982–4991. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0005-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradfield LA, Dezfouli A, van Holstein M, Chieng B, and Balleine BW (2015). Medial Orbitofrontal Cortex Mediates Outcome Retrieval in Partially Observable Task Situations. Neuron 88, 1268–1280. 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang JY, Janak PH, and Woodward DJ (1998). Comparison of mesocorticolimbic neuronal responses during cocaine and heroin self-administration in freely moving rats. J Neurosci 18, 3098–3115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang JY, Sawyer SF, Paris JM, Kirillov A, and Woodward DJ (1997). Single neuronal responses in medial prefrontal cortex during cocaine self-administration in freely moving rats. Synapse 26, 22–35. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen TW, Wardill TJ, Sun Y, Pulver SR, Renninger SL, Baohan A, Schreiter ER, Kerr RA, Orger MB, Jayaraman V, et al. (2013). Ultrasensitive fluorescent proteins for imaging neuronal activity. Nature 499, 295–300. 10.1038/nature12354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chudasama Y, and Muir JL (1997). A behavioural analysis of the delayed non-matching to position task: the effects of scopolamine, lesions of the fornix and of the prelimbic region on mediating behaviours by rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 134, 73–82. 10.1007/s002130050427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowen SL, and McNaughton BL (2007). Selective delay activity in the medial prefrontal cortex of the rat: contribution of sensorimotor information and contingency. J Neurophysiol 98, 303–316. 10.1152/jn.00150.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desrochers TM, Burk DC, Badre D, and Sheinberg DL (2015). The Monitoring and Control of Task Sequences in Human and Non-Human Primates. Front Syst Neurosci 9, 185. 10.3389/fnsys.2015.00185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dezfouli A, and Balleine BW (2019). Learning the structure of the world: The adaptive nature of state-space and action representations in multi-stage decision-making. PLoS Comput Biol 15, e1007334. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1007334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond A (2013). Executive functions. Annu Rev Psychol 64, 135–168. 10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Euston DR, and McNaughton BL (2006). Apparent encoding of sequential context in rat medial prefrontal cortex is accounted for by behavioral variability. J Neurosci 26, 13143–13155. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3803-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusi S, Miller EK, and Rigotti M (2016). Why neurons mix: high dimensionality for higher cognition. Curr Opin Neurobiol 37, 66–74. 10.1016/j.conb.2016.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovannucci A, Friedrich J, Gunn P, Kalfon J, Brown BL, Koay SA, Taxidis J, Najafi F, Gauthier JL, Zhou P, et al. (2019). CaImAn an open source tool for scalable calcium imaging data analysis. Elife 8. 10.7554/eLife.38173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourley SL, and Taylor JR (2016). Going and stopping: Dichotomies in behavioral control by the prefrontal cortex. Nat Neurosci 19, 656–664. 10.1038/nn.4275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochreiter S, and Schmidhuber J (1997). Long short-term memory. Neural Comput 9, 1735–1780. 10.1162/neco.1997.9.8.1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland PC, Asem JS, Galvin CP, Keeney CH, Hsu M, Miller A, and Zhou V (2014). Blocking in autoshaped lever-pressing procedures with rats. Learn Behav 42, 1–21. 10.3758/s13420-013-0120-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horst NK, and Laubach M (2013). Reward-related activity in the medial prefrontal cortex is driven by consumption. Front Neurosci 7, 56. 10.3389/fnins.2013.00056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Merre P, Ahrlund-Richter S, and Carlen M (2021). The mouse prefrontal cortex: Unity in diversity. Neuron 109, 1925–1944. 10.1016/j.neuron.2021.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang B, Zhang L, Barbera G, Fang W, Zhang J, Chen X, Chen R, Li Y, and Lin DT (2018). Distinct and Dynamic ON and OFF Neural Ensembles in the Prefrontal Cortex Code Social Exploration. Neuron 100, 700–714 e709. 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.08.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang B, Zhang L, Moffitt C, Li Y, and Lin DT (2019). An open-source automated surgical instrument for microendoscope implantation. J Neurosci Methods 311, 83–88. 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2018.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madangopal R, Ramsey LA, Weber SJ, Brenner MB, Lennon VA, Drake OR, Komer LE, Tunstall BJ, Bossert JM, Shaham Y, and Hope BT (2021). Inactivation of the infralimbic cortex decreases discriminative stimulus-controlled relapse to cocaine seeking in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology 46, 1969–1980. 10.1038/s41386-021-01067-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz JE, Gillis WF, Beron CC, Neufeld SQ, Robertson K, Bhagat ND, Peterson RE, Peterson E, Hyun M, Linderman SW, et al. (2018). The Striatum Organizes 3D Behavior via Moment-to-Moment Action Selection. Cell 174, 44–58 e17. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquis JP, Killcross S, and Haddon JE (2007). Inactivation of the prelimbic, but not infralimbic, prefrontal cortex impairs the contextual control of response conflict in rats. Eur J Neurosci 25, 559–566. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.05295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathis A, Mamidanna P, Cury KM, Abe T, Murthy VN, Mathis MW, and Bethge M (2018). DeepLabCut: markerless pose estimation of user-defined body parts with deep learning. Nat Neurosci 21, 1281–1289. 10.1038/s41593-018-0209-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon V, and D'Esposito M (2021). The role of PFC networks in cognitive control and executive function. Neuropsychopharmacology. 10.1038/s41386-021-01152-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misra I, and Maaten L.v.d. (2020). Self-supervised learning of pretext-invariant representations. pp. 6707–6717. [Google Scholar]

- Musall S, Kaufman MT, Juavinett AL, Gluf S, and Churchland AK (2019). Single-trial neural dynamics are dominated by richly varied movements. Nat Neurosci 22, 1677–1686. 10.1038/s41593-019-0502-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragozzino ME, Kim J, Hassert D, Minniti N, and Kiang C (2003). The contribution of the rat prelimbic-infralimbic areas to different forms of task switching. Behav Neurosci 117, 1054–1065. 10.1037/0735-7044.117.5.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigotti M, Barak O, Warden MR, Wang XJ, Daw ND, Miller EK, and Fusi S (2013). The importance of mixed selectivity in complex cognitive tasks. Nature 497, 585–590. 10.1038/nature12160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risterucci C, Terramorsi D, Nieoullon A, and Amalric M (2003). Excitotoxic lesions of the prelimbic-infralimbic areas of the rodent prefrontal cortex disrupt motor preparatory processes. Eur J Neurosci 17, 1498–1508. 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, and Flagel SB (2009). Dissociating the Predictive and Incentive Motivational Properties of Reward-Related Cues Through the Study of Individual Differences. Biol Psychiat 65, 869–873. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roughley S, and Killcross S (2021). The role of the infralimbic cortex in decision making processes. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences 41, 138–143. [Google Scholar]

- Silva KM, Silva FJ, and Machado A (2019). The evolution of the behavior systems framework and its connection to interbehavioral psychology. Behav Processes 158, 117–125. 10.1016/j.beproc.2018.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner BF (1938). The behavior of organisms; an experimental analysis (D. Appleton-Century company; ). [Google Scholar]

- Smith KS, Virkud A, Deisseroth K, and Graybiel AM (2012). Reversible online control of habitual behavior by optogenetic perturbation of medial prefrontal cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109, 18932–18937. 10.1073/pnas.1216264109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas CMP, Thrailkill EA, Bouton ME, and Green JT (2020). Inactivation of the prelimbic cortex attenuates operant responding in both physical and behavioral contexts. Neurobiol Learn Mem 171, 107189. 10.1016/j.nlm.2020.107189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thrailkill EA, and Bouton ME (2015). Extinction of chained instrumental behaviors: Effects of procurement extinction on consumption responding. J Exp Psychol Anim Learn Cogn 41, 232–246. 10.1037/xan0000064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]