Abstract

Type I interferons (IFNs) are so-named because they interfere with viral infection in vertebrate cells. The study of cellular responses to type I IFNs led to the discovery of the JAK-STAT signaling pathway, which also governs the response to other cytokine families. We review here the outcome of viral infections in mice and humans with engineered and inborn deficiencies, respectively, of (i) IFNAR1 or IFNAR2, selectively disrupting responses to type I IFNs, (ii) STAT1, STAT2, and IRF9, also impairing cellular responses to type II (for STAT1) and/or III (for STAT1, STAT2, IRF9) IFNs, and (iii) JAK1 and TYK2, also impairing cellular responses to cytokines other than IFNs. A picture is emerging of greater redundancy of human type I IFNs for protective immunity to viruses in natural conditions than was initially anticipated. Mouse type I IFNs are essential for protection against a broad range of viruses in experimental conditions. These findings suggest that various type I IFN-independent mechanisms of human cell-intrinsic immunity to viruses have yet to be discovered.

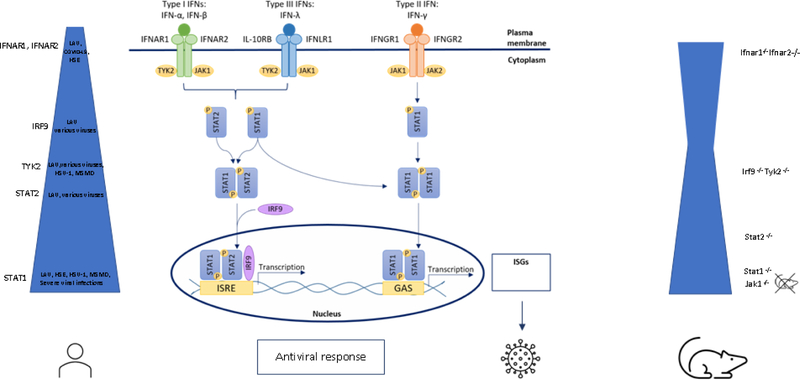

Graphical Abstract

Mouse and human type I IFN pathway defects result in comparable increased susceptibility to viral infection for STAT1 >STAT2 > TYK2 and IRF9 deficiency. In contrast, human IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 deficiency present with susceptibility to live attenuated vaccine (LAV) disease, and more recently to SARS-CoV2. Further research in mice and inborn errors of immunity will delineate the essential and redundant roles of type I IFNs in antiviral defense.

Introduction

In 1957, Isaacs and Lindenmann discovered that influenza virus-infected chicken embryo cells produced and released a substance that protected uninfected cells against infection (1–3). As this substance “interfered” with viral infection, it was given the name “interferon”. Type I interferons (IFNs) form a multigenic family, with 13 IFN-α subtypes in humans (14 in mice), single IFN-β, IFN-ε, and IFN-κ types in both mice and humans, plus IFN-ω in humans, and IFN-ζ in mice (4). Type I IFNs mediate potent antiviral and other effects on stimulated cells through the induction or repression of target genes (5–7). Type I IFNs are encoded by intron-less genes clustering on chromosome 9 in humans and chromosome 4 in mice. All discernable cell types apparently produce at least one type I IFN and can respond to type I IFNs via their unique heterodimeric receptor, consisting of IFNAR1 and IFNAR2. By contrast, type II IFN, described in 1965, consists of a single gene product, predominantly secreted by NK and T lymphocytes, and acting on a broad range of cells expressing IFNGR1 and IFNGR2 (8). However, this molecule, better known as IFN-γ rather than type II IFN, acts more as a macrophage-activation factor than as an antiviral IFN in both mice and humans (9, 10). Finally type III IFNs, or IFN-λ, were described in 2003; they are encoded by four genes in humans, including IFNL4, which is undergoing pseudogenization, and two pseudogenes and two genes in mice (4, 11). They are produced by many cells, but seem to act mostly at epithelial surfaces, given the distribution of their receptor, which is composed of IFNLR1 and IL10RB (12, 13).

Type I IFNs are monomers that signal through a heterodimer composed of a low-affinity IFNAR1 subunit and a high-affinity IFNAR2 subunit (14, 15). IFNAR ligation results in the phosphorylation of TYK2 (constitutively associated with IFNAR1) and JAK1 (with IFNAR2) (16–19). Ligand-receptor interaction results in JAK phosphorylation and activation (20). Activated JAKs then phosphorylate the receptor, which attracts the signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT) STAT1 and STAT2. Once these STATs are themselves phosphorylated, they can heterodimerize with the DNA-binding protein IRF9 (p48) to form interferon-stimulated gene factor 3 (ISGF3) or form STAT1 homodimers (16, 21). ISGF3 promotes or, more rarely, regulates the transcription of genes through the IFN-stimulated response element (ISRE), whereas STAT1 homodimers operate via gamma activation sites (GAS) (22–25). ISGF3 is also the crucial signaling component downstream from the IFN-λ receptor, accounting for the overlapping effects of type I and type III IFNs. In the ISGF3 complex, IRF9 provides specificity for binding to ISRE, a motif that can be recognized by other IRF proteins (26). However, IRF9 requires STAT1 and STAT2 for efficient DNA binding and transcriptional activity. STAT1 homodimers play an essential role in transducing signals downstream from IFN-γ (17, 27–29). There seems to be some overlap in the signal transduction pathways, with type I IFNs inducing STAT1 homodimers and driving GAS-mediated gene expression, and IFN-γ activating ISGF3 complexes containing unphosphorylated STAT2 that bind ISRE (Fig. 1)(30, 31).

Figure 1.

Overview of Type I, Type II and Type III Signaling Pathways. Upon binding to their respective receptors, the JAK-STAT signaling pathways are activated that lead ultimately to induction and transcription of ISGs, resulting in the induction of antiviral responses. In humans, IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 deficiency predispose to disease following LAV vaccine, but also to Herpes Simplex Encephalitis and severe COVID-19. AR STAT2 deficiency is characterized by a broader phenotype with susceptibility to LAV but also to various other viruses. AR complete STAT1 deficiency presents with the most severe phenotype, including life-threatening viral infections, but also life-threatening mycobacterial infections. TYK2 deficiency is similar but with a somewhat milder viral phenotype. No humans with complete JAK1 deficiency are described until now. In mice, there is broad viral susceptibility with STAT1−/− more severe than Ifnar1−/− and Ifnaar2−/− and STAT2−/− mice, and these more severe than Tyk2−/− and Irf9−/− at least for the viruses and the models tested. The width of the blue bar indicates the extent of viral susceptibility.

Most studies of the type I IFN response pathway have focused on its role in antiviral defense, via the induction of ISGs (32). We will not review here studies of cell-intrinsic antiviral immunity conducted in vitro, with mouse or human primary cells, or with cell lines. Instead, this review focuses on studies conducted in vivo in mice and in natura in humans (33–36), as in our previous reviews for this journal on the IL-12, IL-17, and TLR and IL-1R pathways (37–39) and adding to similar recent reviews by us and others (36, 40). In addition to the general limitations inherent to experimental studies in mice, a specific limitation applies to studies of the type I IFN response pathway, as many inbred laboratory strains lack one or more ISGs. For instance, CBA/J, DBA/2J and BALB/c mice lack Mx1, the canonical anti-influenza ISG (41–43). Particular attention must, therefore, be paid to the genetic background of the mice in which the type I IFN pathway is studied by reverse genetics (42). The study of inherited defects of the human type I IFN response pathway in natura is timely, as some of these defects have been shown to underlie life-threatening COVID-19 pneumonia, with auto-antibodies against type I IFNs accounting for at least another 10% of patients with this condition (44–46). We will successively review the studies of (i) IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 deficiencies, (ii) JAK1 and TYK2 deficiencies, and (iii) STAT1, STAT2, and IRF9 deficiencies.

1. IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 deficiency

Ifnar1−/− mice

The IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 genes encode the heterodimeric receptor for type I IFNs (15). The α-subunit (IFNAR1) was the first to be cloned, based on its ability to confer resistance to VSV infection in mouse cells in response to IFN-α8 (47). The first experimental model of viral infection in Ifnar1−/− mice, dates back to 1994. Ifnar1−/− mice (a.k.a Ifnαβ−/− mice), engineered by homologous recombination in a mixed B6.129sv background, did not express the wild-type IFNAR1 or respond to type I IFNs in terms of ISG induction (48–50). The mice were extremely susceptible to infection with various viruses, including vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV), Semliki Forest virus, Vaccinia virus, Sindbis virus, and Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV), with a lower LD50 and deaths occurring earlier than in wild-type controls (48, 51) (Table 1). Ifnar1−/− mice are also highly susceptible to various influenza virus strains, displaying disseminated infection (28, 52–54). Ifnar1−/− mice have been shown to be highly susceptible to all viruses tested, with greater mortality and earlier deaths: Usutu virus, Freund retrovirus, Ross River virus, Rift Valley fever virus, West Nile virus, Dengue virus, Yellow fever virus, Zika virus, Ebola virus (list, see Table 1) (51, 55–85). Mice lacking both Ifngr1 and Ifnar1 displayed greater viral susceptibility than Ifnar1−/− mice, which themselves more susceptible than Ifnγ−/− mice to MCMV infection (86). Ifnar1−/− mice have been found to have a greater susceptibility to and mortality due to all viruses tested. By contrast, Ifnar1−/− mice are no more sensitive to intracellular bacteria and parasites than the wild type (Fig. 1) (48).

Table 1.

Overview of in vivo viral infection models in Ifnar1−/−, Tyk2−/−, Stat1−/−, Stat2−/−, and IRF9−/− mice

| Gene knockout | Mouse strain | Virus strain | Virus subtype | Viral phenotype | Mortality | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ifnar1−/− | B6/129 | VSV, Semliki forest virus, i.v Vaccina virus, iv LCMV (f.p.)/(i.c.) |

WE* | Decreased LD50 (6 orders of magnitude) | Increased, d3–6 p.i. Not lethal |

(48, 49) |

| Ifnar1−/− | B6.A2G.M ×1 | Influenza, SC35M and A/PR/8/34 (i.n.) | SC35M (H7N7) and A/PR/8/34, (H1N1) | Disseminated infection | Increased | (54) |

| Ifnar 1−/− | 129/Sv/Ev | Influenza A (i.n.) | A/WSN/33 and A/PR/8/34 (H1N1) | High lung titers; Disseminated infection of the lung and brain | NA (sacrificed) | (52) |

| Ifnar1−/− | 129 | Influenza A/PR/8 (i.n.) |

Patchy bronchopneumonia | (28) | ||

| Ifnar 1−/− | C57BL/6 | MCMV (i.v.) | 100% lethal | (116) | ||

| Ifnar1−/− | C57BI/6 | Usutu virus (f.p.) | Spain South Africa Uganda Senegal |

Depression, paraplegia, paralysis, coma; Disseminated infection |

100% mortality d5 except for the Netherlands strain | (57) |

| Ifnar1−/− | Usutu virus (i.p.) | Saar 1776 | Disseminated infection | 90% mortality d10 p.i. | (58) | |

| Ifnar1−/− | Friend retrovirus | Disseminated infection | NA (sacrificed) | (59) (60) |

||

| Ifnar1−/− | 129Sv/Ev | Rift valley Fever Virus | MP12 ZH548 |

100% mortality d2 p.i. versus d21 p.i. in WT, 66% mortality d2, 100% d6 p.i. |

(61) | |

| Ifnar1−/− | 129Sv/Ev | West Nile Virus (s.c.) | Disseminated disease | 100% mortality d3.8 post infection vs. 62% d11.9 | (63) | |

| Ifnar1−/− | C57BI/6 | West Nile Virus (f.p.) | Disseminated disease | 100% mortality d-,4 post infection | (64) | |

| Ifnar1−/− | C57BI/6 | West Nile Virus (s.c.) | NY1999 | Disseminated infection | 100% mortality d9 p.i. | (171) |

| Ifnar1−/− | 129Sv/Ev | DENV-1, DENV-2 (i.v.) | Disseminated disease | No mortality vs. AG129 100% mortality | (65) | |

| Ifnar1−/− | 129Sv/Ev | YFV (f.p.) | Asibi / Angola 73 | Disseminated viscerotropoic disease | Death 7–9 dpi | (172) |

| Ifnar1−/− | 129Sv/Ev | JEV (s.c.) | JaOArS982 | Disseminated disease | 90%, 120h post infection | (67) |

| Ifnar1−/− | 129Sv/Ev | Zika virus (s.c.) | MP1751 | Encephalitis | 100% lethal at 6 dpi vs. asymptoma tic | (68) |

| Ifnar1−/− | C57BI/6 | Zika virus (f.p.) | H/PF/2013 MR766 |

Encephalitis and viscerotropic disease | 100% 8–10d p.i. 80% 9.13 d p.i. vs. no symptoms in WT |

(69) |

| Ifnar1−/− | Zika virus (s.c.) |

MR766, Dakar41519, Dakar41677 | Long duration of high levels in the brain, spinal cord and testes | 100% Lethal vs. no clinically overt illness in WT | (69) | |

| Ifnar1−/− | C57BI/6 | Zika virus sc | FSS13025 | Age-dependent mortality 100% at 3w vs. 0 at 11 w | (70) | |

| Ifnar1−/− | 129Sv/Ev | Ebola virus Sudan virus Reston virus Tai forest virus Marburg virus Ravn Virus (i.p.) |

Mayinga/Kikwit Boneface |

100% 5.4d p.i. vs. 0 100% lethal 6.3 dpi 0% 0% 67% d8.5 p.i. 100% d6 p.i. |

(71) | |

| Ifnar1−/− | 129Sv/Ev | Myainga Ebola (s.c.) | 100% 7.3 dpi | (71) | ||

| Ifnar1−/− | 129Sv/Ev | Ebola aerosol Marburg aerosol Sudan virus aerosol |

Anorexia, weight loss | 100% 8d p.i. 100% 11–13d p.i. 0% |

(72) | |

| Ifnar1−/− | 129Sv/Ev | Lassavirus( i.v.) | Josiah, AV, BA366, Nig04–10, IV | Hepatitis, weight loss; High levels of live virus at 9d p.i. | 0% | (73) |

| Ifnar1−/− | 129Sv/Ev | Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus ip | IbAr2000 | Disseminated infection vs. asymptomatic infection in WT | 100% | (74) |

| Ifnar1−/− | C57BI6 | Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus i.p./i.m./i.n./s.c. |

IbAr2000 | Coagulopathy tc penia – disseminated infection vs. asymptomatic infection in WT |

100% 4, 5, 7, 4 i.p./i.m./i.n./s.c. |

(75) |

| Ifnar1−/− | 129Sv/Ev | Severe fever TCP syndrome virus | YL-1, s.c. | Disseminated disease; All dead 3–4d p.i. | 100% d3–4 p.i. vs. limited weight loss in WT | (76) |

| Ifnar1−/− | C57BI6 | Severe fever TCP syndrome virus i.d., i.p., i.m., s.c. |

Sd4 | All dead, via all routes | 100% | (77) |

| Ifnar1−/− | C57BI6 | Nipah virus i.n., i.p., i.c. |

Disseminated infections; Lower mortality in older animals |

100% d3 p.i. (i.c.) 100% d8 p.i. (i.p.) 40% d15 p.i. (i.n.) |

(78) | |

| Ifnar1−/− | 129SVJ | Semliki Forest virus, i.p. | 100% d2 p.i. | (49) | ||

| Ifnar1−/− | 129Sv/Ev | Semliki Forest virus i.p |

A7(74) and SFV4 | Disseminated infection in extra-neuronal tissues including brain endothelium | 100% d3 p.i. | (79) |

| Ifnar1−/− | 129Sv/Ev | Sindbis virus TR339 s.c. |

Disseminated infection, infection prominent in macrophages and dendritic cell like cells in spleen, liver, lung, thymus, kidnye | 100% 84 h p.i. | (51) | |

| Ifnar1−/− | 129Sv/Ev | VEE (human/horse) (s.c.) |

V3000 and 43043 | 100% at 30h p.i. versus 7.7 days in WT | (80) | |

| Ifnar1−/− | 129Sv/Ev | VEE (f.p.) |

V3000 V3032 |

100% at d1 p.i. in both strains vs. d 7–9 p.i. for WT V3000 infected | (81) | |

| Ifnar1−/− | 129Sv/Ev | VEE 3000 or 3032 (i.p.) |

V3000 V3032 |

Hunching ruffled fur, lethargy, death | 100% d1 p.i. | (82) |

| Ifnar1−/− | 129Sv/Ev | Eastern equine encephalitis virus (s.c.) | 792138 NA FL 93939 NA 300851 and GML SA |

Higher viremia and shorter survival except for GML SA where there was no differential effect | 90% at d7 p.i. for 792138 NA strain | (81) |

| Ifnar1−/− | 129Sv/Ev | Chikungunya virus (i.d.) | Hemorrhagic fever; Dissemination into Liver, spleen, leptomeningeal cells, muscle |

100% at d3 p.i. | (83) | |

| Ifnar1−/− | C57BL/6 | Chikungunya virus (f.p.) | 100% at d4 p.i. | (84) | ||

| Ifnar1−/− | 129S6 (A129) | O’Nyong-Nyong virus (i.p.) (f.p.) |

SG650, MP30 | Weight loss, lethargy, muscle and liver infection Muscle swelling |

50% | (85) |

| Ifnar2−/− | C57BL/6and 129S2 | Influenza virus it | H1N1 (A/PR/8/34) | Increased morbidity and mortality | 90% d8 p.i. | (90) |

| Tyk2−/− | Mixed 129/SvJ, C57BL/6 | VSV (i.v.) Vaccinio virus (i.v.) |

Mudd-Summers isolate | Elevated viral replication in the spleen | 20% mortality vs. 0% in WT but 88% of Ifnar1−/− | (98) |

| Tyk2−/− | Mixed 129/SvJ, C57BL/6 | VSV (i.n.) | Indiana strain | 100% lethal within 7 days vs. <40% in WT | (100) | |

| Tyk2K923E kinase-inactive |

Mixed 129/SvJ, C57BL/6 or C57BL/6 | VSV (i.n.) | Indiana strain | 100% lethal within 7 days vs. < 40% in WT | (100) | |

| Tyk2−/− | Mixed 129/SvJ, C57BL/6 | EMCV (i.p.) | Lethal | (100) | ||

| Tyk2K923E kinase-inactive |

Mixed 129/SvJ, C57BL/6 or C57BL/6 | EMCV (i.p.) | Lethal | (100) | ||

| Tyk2−/− | Mixed 129/SvJ, C57BL/6 | LCMV (i.v.) | WE | Significant (3- to 10-fold) decrease in cytotoxic Tlymphocyte (CTL) activity | NA | (98) |

| Tyk2−/− | NA | LCMV (i.v.) | Clone 13 | Resistance to LCMV-induced lymphoid hypoplasia, particularly in cells of the B lineage | NA | (99) |

| Tyk2−/− | Mixed 129/SvJ, C57BL/6 | Vaccinio virus (i.v.) | Strain WR | High levels of viral replication in the spleen | NA | (98) |

| Tyk2−/− | C57BL/6 | MCMV (i.v.) | Smith strain VR-194 | High levels of viral replication in all organs except the spleen; 103-fold increase in MCMV replication in macrophages | Lethal within 7 days | (101) |

| Stat1−/− | B6/129SV/Ev | Mouse hepatitis virus; Natural infection |

LD50 decrease by 6 orders of magnitude | Lethal< 48 h | (28) | |

| Stat1−/− | B6/129SV/Ev | VSV (i.v.) | Indiana | LD50 decreased by 6 orders of magnitude | Lethal<48h | (28) |

| Stat1−/− | B6/129Sv/Ev | Influenza virus A (i.n.) |

A/PR/8/34 | Diffuse bronchopneumonia | 10x more susceptible to lethal infection than WT and Ifnar−/− | (111) |

| Stat1−/− | 129Sv/Ev | Influenza virus (i.p.) | WSN/33 | Fulminant systemic infection | NA (sacrificed) | (52) |

| Stat1−/− | 129Sv/Ev | Sindbis virus (i.p.) | Mortality slightly higher than WT | (86) | ||

| Stat1−/− | 129Sv/Ev | MCMV (i.v) | Mortality as for Ifnar−/− receptor deficiency | (86) | ||

| Stat1−/− | 129Sv/Ev | Murine norovirus type 1 (p.o.; i.c.) |

75% d60 p.i. (p.o.) 100% d15 p.i. (i.c.) |

(173) | ||

| Stat1−/− | 129S6Sv/Ev | Norovirus (p.o.) | Lymphangitis and colitis, hepatitis splenitis | Not lethal | (112) | |

| Stat1−/− | 129S6Sv/Ev | HSV1 Into the cornea |

Wt | Prolonged inflammatory disease, more replication at cornea; weight loss, disseminated disease |

100% lethal d7 p.i. | (114) |

| Stat1−/− | 129/Sv/Ev | LCMV (i.p.) | A rmstrong 53b | Disseminated disease | 100% lethal D7 | (117) |

| Stat1−/− | C57BL6 | SARS-CoV2 (i.n.) | Greater weight loss and lung disease | NR | (119) | |

| Stat2−/− | Mixed W9.5 ESC, RAG1−/−, 129/SvJ | VSV (i.v.) | Indiana strain | High levels of viral replication in spleen and liver | 100% d6 p.i. | (132) |

| Stat2−/− | 129/Sv/Ev | LCMV (i.c.) | Armstrong 53b strain | Late and significantly smaller increase in ISG expression after infection | NA | (174) |

| Stat2−/− | 129/Sv/Ev | LCMV (i.p.; i.c.) | Armstrong 53b strain | Persistent infection, moderate disease | À% | (141) |

| Stat2−/− | 129/Sv/Ev | Influenza A (i.n.) | A/HK-X31 (H3N2) | High viral titers | 100% d11 p.i. | (135) |

| Stat2−/− | C57BL/6 | Influenza A (p.o.) | A/PR/8/34 (H1N1) | More severe disease, increased lung viral load, pulmonary inflammation with polymorphonucl ear exudate; delayed recovery after infection in males | 80% lethality in females | (138) |

| Stat2−/− | 129/Sv/Ev | Dengue virus iv | Strain S221 | Delayed IFN-α production after infection | 0% | (139) |

| Stat2−/− | 129/Sv/Ev | Human metapneumovirus in/it | clinical strain TN/94–49 (subtype A2) | High viral titers | 0% | (175) |

| Stat2−/− | C57BL/6 | Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus (SFTSV) (i.d.) | YG-1 strain | Thrombocytopenia, transient leukopenia, high viral titers in plasma and all organs (highest in spleen and kidney) | 100% d7 p.i. | (140) |

| Stat2−/− | C57BL/6 | Zika virus (ZIKV) (s.c.) | Uganda strain MR766 Senegal strain DAKAR 41519 |

Reduced motility, limb paralysis; High viral titers in the brain and gonads | 100% d7 p.i. | (137) |

| C57BL/6 | Zika virus (ZIKV) (s.c.) | Cambodia strain FSS13025 |

Milder neurological symptoms: Delayed onset, milder but more prolonged disease than for the African strains |

Increased by 20% | (137) | |

| C57BL/6 | Zika virus (ZIKV) (s.c.) | Malaysia strain P6–740 Puerto Rico strain PRVABC59 |

Delayed onset, milder but more prolonged disease than for the African strains | 0% | (137) | |

| Stat2m/m (hypomorphic) | C57BL/6 | EMCV (i.p.) | Lethal within 2–4 days | (176) | ||

| Trf9−/− | C57BL/6 | LCMV (i.p.) | Armstrong strain | More severe clinical disease, development of chronic infection with inflammatory infiltrates of liver and CNS | 0% | (155) |

Abbreviations: i.c. : intracerebral; i.d. : intradermal; p.i. : post-infection; i.v. : intravenous; i.p. : intraperitoneal ; s.c. : subcutaneous ; f.p. : injection in footpad ; p.o. : per os ; LD50 : median Lethal Dose for 50% of subjects ; LCMV WE strain : virulent strain named after strain isolated from an infected human with the initials « WE ». Most other strains are named after the place of isolation or the researcher who isolated the strain (e.g. Armstrong), or the surface proteins (e.g. H1N1)

Human AR IFNAR1 deficiency

Only nine patients with autosomal recessive (AR) complete IFNAR1 deficiency from six unrelated kindreds have been described to date (45, 87–89) (Table 2). Most of the causal mutations are nonsense mutations or substitutions of essential splice sites, resulting in a premature stop codon and an absence of functional IFNAR1. A deletion of the coding sequence and part of the 3’UTR of the last exon of IFNAR1 has recently been described (88). This deletion led to the expression at the cell surface of a C-terminally truncated protein unable to bind Tyk2, resulting in an absence of response to IFN-α2b or IFN-β, in terms of STAT1, STAT2, and STAT3 phosphorylation, or the induction of ISGs, as for the other mutations. All the other known patients display an absence of IFNAR1 expression at the cell surface. Six of the nine patients, presented with disseminated infection following inoculation with live attenuated viral vaccine in infancy or childhood (three of four cases after MMR, and 1 after YFV 17D vaccination). HSV-1 encephalitis (HSE) with a fatal outcome was described in one patient. The patient vaccinated with YFV 17D and the patient with HSE had previously received the MMR vaccine with no adverse effects and only a prolonged fever, respectively (88). Finally, two of the nine patients with IFNAR1 deficiency presented life-threatening COVID-19 at the ages of 38 and 26 years, which was fatal in one of these cases (45). Seroconversion for various viruses, including VZV, CMV, EBV, HHV6, HHV4, Adenovirus, Rhinovirus, Enterovirus, HAV, RSV and IAV, was noted in the IFNAR1-deficient cousin of the IFNAR1-deficient patient with HSE. This patient suffered recurrent aseptic meningitis, followed by sudden deafness after parotitis, presumably due to mumps, at the age of 14 years. This patient was not vaccinated with MMR (87, 88). Thus, human IFNAR1 deficiency is characterized by incomplete clinical penetrance for disseminated disease due to live attenuated viral vaccines. Unlike ifnar1−/− mice, humans with complete IFNAR1 deficiency have a narrow viral infectious phenotype, which remains unexplained. The HSE and COVID-19 pneumonia observed in these patients occurred in natural conditions, unlike the adverse reactions to live vaccines (Fig. 1)..

Table 2.

Genetics and viral infection phenotype of patients with complete IFNAR1, IFNAR2, JAK1, TYK2, STAT1, STAT2, and IRF9 deficiencies

| Gene | Mutation | N confirmed (Country) | Severe viral phenotype / infections with normal course / exposure | MSMD | Other | Age at last follow-up | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IFNA R1 |

c.674-2A>G hoz c.783G>A;pW261X and c.674-1G>A |

3 from 2 kindreds Iran Brazil |

P1: 1 y MMR disseminated disease and encephalitis; exposed to CMV P2:1 y: disseminated disease post MMR, fatal P3: disseminated YFV 17D disease with fever, shock, renal and hepatic insufficiency, pleural effusion and atelectasis; oral polio, BCG and MMR vaccinations uneventful; seroconversion for CMV, HSV1, HSV2 |

NR | NR | 10 y 1 y* 14 y |

(87) |

| Hoz. deletion intron 10 to exon 11 and 3′UTR g.34,726,420_34,728, 094deln aberrant splicing, resulting in a C-terminally truncated protein, expressed at cell surface but not binding to Tyk2 (low levels of mRNA and protein) |

3 from 1 kindred Palestini an territory |

P1: 13 mo prolonged fever, post-MMR fever with spontaneous resolution; gingivostomatitis and aseptic meningitis, HSV-1 gingivostomatitis and HSE 19 mo, died at 20 months P2 Aseptic meningitis, 14 y parotitis, deafness after mumps? (P2), did not receive MMR, seroconversion for many viruses P3 disseminated disease following MMR vaccination at 12m(not genotyped) |

NR | NR | 20 mo* 17 y 12 mo* |

(88) | |

| p.Ser422Arg/Ser422Arg p.Trp73Cys/Trp73Cys |

2 from 2 kindreds 1 Saudi-Arabia, 1 Turkey |

Life-threatening COVID-19, one fatal outcome; EBV seroconversion | NR | NR | 38 y 26 y* |

(45) | |

| c922C>T; p.Gln308Ter | ? | Severe reaction to MMR 15 mo (encephalitis, death) | NR | HLH | 21 mo* | (89) | |

| IFNA R2 | Complete; c.A311del; pE104fs110X, truncated protein) no expression | 2, from 1 kindred, UK |

P1 Severe reaction to MMR (meningoencephalitis) at age 13 mo (HHV6 uncomplicated infection, seroconversion for CMV, EBV) P2: well (MMR not administered) |

NR | HLH Treated with SCIG |

1.3 y* 5 y |

(95) |

| Homozygous c.840+1G>T;p.Ser238 Phefs*3 | 2 from 1 kindred, Brazil |

P1: well until YFV 13 y, epistaxis, hepatitis, hypotension. P2 (sisterof P1: YFV-17D disease at 19 y |

13 y? 19 y* |

(85) | |||

| TYK2 | Complete 4 bp del exon 4: C70HfsX21 9 bp del exon 16 c.2303_2311del c.3318_3319insC c.462G>T;E154X c.149delC; S50HfsX1 c.1912C>T;R638X |

1, Japan | Molluscum contagiosum, cutaneous and mucosal HSV, parainfluenza virus pneumonia | MSMD | Salmonella, mucocutaneous candidiasis | 35 y | (102, 103) |

| 1, Turkish | P1 chickenpox, shingles twice | MSMD | Brucella meningitis | 28 y | (103) | ||

| 2 from 1 kindred Morocco | P2 NR P3 meningitis? |

MSMD, abdomin al TB | Bacterial meningitis | 14 y* 20 y |

|||

| 2 from 1 kindred Iran | P4 NR P5 viral skin infection |

MSMD MSMD |

10 y? 7 y? |

||||

| Iran | P6 | TB | 14 y? | ||||

| Argentina | P7 18 mo HSV gingivostomatitis aseptic meningitis and cutaneous hsv at 24 mo; 10 y HSV meningitis | NR | 16 y? | ||||

| 1, Kurdish, living in Germany | NR received MMRvaccine, seroconversion for HHV6, ParvoB19, Influenza A | NR | Bacterial infection, anal and skin abscesses | 10 y? | (104) | ||

| C647delC fs P216Rfs*14 | 1 Persian-Turks, Iran (2 died, not genotyped) | HSV gingivostomatitis twice, at 3 and 7 y, aseptic meningitis age 6 y, VZV (two uncles died at age 1 y and 3 y) |

MSMD | NR | 7 y? | (105) | |

| STAT 1 | c.1757_1758delAG/1757_1758delAG | Saudi-Arabia | Recurrent HSV1, lethal disseminated meningoencephalitis | MSMD | NR | 16 mo* | (120) |

| p.L600P/L600P | Saudi-Arabia | Lethal undefined viral illness | MSMD | NR | 12 mo* | (120) | |

| p.L600P/L600P | Saudi-Arabia | MSMD | 3 mo* | (120) | |||

| p.L600P/L600P | Saudi-Arabia | MSMD | 3 mo* | (120) | |||

| c.1928insA/1928insA | 1, Pakistan | Vaccine strain polio shedding, Fulminant EBV LPD post HSCT, infection with HRV, PIV2 |

MSMD | Severe hepatitis | 11 mo* 2 mo post HSCT | (121) | |

| p.Q124/p.Q124H | 1, Pakistan | Interstitial pneumonia with CMV, encephalitis; recurrent enterovirus infection, cutaneous HSV, EBV | MSMD, no BCG vaccine, M. kansasii | NR | HSCT, 15.5 y old | (122) | |

| c.88delA/88delA | 1, Australia | Severe reaction to MMR/HHV6 infection with encephalopathy and multisystem inflammatory response | NR (BCG naïve) | HLH | 5 y, post HSCT | (97) | |

| c.128+2T>G/542-8A>G | 1, Japan | RSV, influenza A, hMPV, paralyticileus post rotavirus, vaccine-induced chickenpox, MMR encephalopathy | MSMD (BCG, M. malmoense) | HLH | 6 y, post HSCT | (124) | |

| c.1011_1012delAG/c.1011_1012delAG Val339ProfsTer18 |

1, Guinea | Meningoenceph alitis of unknown cause, VZV vaccine strain disease and parainfluenza virus with HLH; fatal CMV reactivation post HSCT | NR (BCG naïve) | HLH, Rothia dentocariosa, Streptococcus viridans, Klebsiella pneumoniae | 20 mo* | (125) | |

| STAT 2 | Complete, c.381+5G>C/c.381+5G>C |

5, 1 kindred, UK |

P1 MMR pneumonia, HSV1 gingivostomatitis, IAV pneumonia (EBV asymptomatic) P2 fatal virus infection 10 w P3 evidence of MMR inoculation, VZV, CMV infection, no severe illness known P4 Bronchiolitis, MMR encephalitis, uncomplicated VZV P5 viral illness, VZV uncomplicated |

NR | NR | Alive, age? 10 w* Alive, age? Alive, age? Alive, age? |

(143) |

| Absent (splice and stop) c.1528C>T/1576G>A | 2 Belgium | P1 MMR hepatitis, Severe RSV, EV, Adv, Fatal viral illness P2 Severe VZV, MMR pneumonia, hepatitis, EV meningitis, prolonged primary EBV |

NR NR |

NR HLH-like / Kawasakilike disease after MMR |

7 y* 16 y |

(144) | |

| Absent (stop) c.1836C>A/1836C>A |

2 Albania | P1 MMR opsoclonus - myoclonus syndrome P2 MMR encephalitis |

NR | NR | 11 y 9 y |

(149) | |

| Splice c,1209+1delG | Nepal | P1 common viral infections with RSV, norovirus, coxsackie virus. MMR disseminated disease | NR | HLH after MMR | 3 y | (146) | |

| IRF9 | Reduced expression truncated product (exon 7) Complete |

Algeria, France | Severe IAV pneumonia 23 mo, biliary perforation post MMR – infection with RSV, hMPV, Adv, parainfluenza virus, evidence of HSV, CMV, HRV, EV infection | Recurrent fevers | (157) |

Explanation of symbols used:

deceased: ?: age unknown; hoz: homozygous

Ifnar2−/− mice

Ifnar2−/− mice were not described until 2006 (50). Comparisons with Ifnar1−/− mice revealed a similar susceptibility to viral infection (90). Consistent differences between Ifnar1−/− and Ifnar2−/− mice were found only in inflammatory conditions such as Socs deficiency-driven inflammation, LPS toxicity and ischemic brain damage (50, 91, 92).

Human AR IFNAR2 deficiency

Four cases of AR IFNAR2 deficiency have been described to date (Table 2). The causal mutations include substitutions of an essential splice site and a single-base deletion, all resulting in frameshifts and premature stop codons, with a loss of expression of the full-length protein (93, 94). The cells of the first patient studied displayed a complete failure of tyrosine phosphorylation of JAK1, TYK2, STAT1/2, and ISG induction in response to IFN-α and IFN-β. Responses to IFN-γ were maintained. The transduction of patient fibroblasts with WT IFNAR2 rescued STAT1 phosphorylation, ISG induction and the control of viral replication. The patient’s fibroblasts failed to control the replication of attenuated virus, even in the presence of exogenous IFN-α. Clinically, patients typically present in infancy or childhood. The first patient developed fatal meningoencephalitis complicated by hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis following MMR vaccination (95). Sustained replication of the vaccine viruses and of HHV6 were demonstrated in the patient’s blood and brain. Evidence for seroconversion for CMV and EBV in the absence of overt disease was obtained, consistent with the findings of narrow viral susceptibility in IFNAR1 deficiency. The sibling of this patient did not receive MMR and remains clinically well at the age of five years. Two additional patients displayed manifestations only in their teens, at the time of YFV 17D vaccination, when they developed viscerotropic disease, leading to the death of one of these patients and the recovery of the other (94). Thus, IFNAR2 deficiency is clinically similar to IFNAR1 deficiency, at least in the patients described to date, with a narrow viral susceptibility and presentation at the time of live attenuated virus inoculation. None of the reported patients with IFNAR2 has suffered from severe natural viral infections, suggesting that the clinical infectious phenotype of human IFNAR2 deficiency may be less severe than that of IFNAR1 deficiency. This would be consistent with the demonstration in vitro that some types of IFN, such as IFN-β, signal via Ifnar1 in the absence of Ifnar2, at least in mice (Fig 1)(91).

2. Deficiencies of JAK1 and TYK2

JAK1 deficiency

Jak1−/− mice

Wilks et al. described the first member of the protein-tyrosine kinase (PTK) family, which is characterized by the presence of a second phosphotransferase-related domain, N-terminal to the PTK domain, hence the name Janus kinase 1 (96). Mice lacking Jak1 are small at birth, fail to suckle, and die within 24 h of birth. They have a profound defect of lymphocyte development despite normal thymic and bone marrow architecture. There are, therefore, no in vivo models for studying viral susceptibility in Jak1−/− mice, and our knowledge is based exclusively on in vitro studies of type I IFN. Jak1−/− cells do not respond to cytokines signaling via class II cytokine receptors (IFN-α, IFN-β, IFN-γ, and IL-10), cytokine receptors using the γ(c) subunit for signaling (IL-2, IL-4, IL-7, IL-9, and IL-15), and cytokine receptors dependent on the gp130 subunit for signaling (IL-6, IL-11, LIF, OSM, CNTF, and CT-1). Accordingly, embryonic fibroblasts (EFs) derived from Jak1−/− mice fail to respond to type I and type II IFNs in terms of the upregulation of MHC class I molecules. Jak 1−/− EFs are also highly susceptible to the cytopathic effect of VSV in the presence or absence of IFN-α or IFN-γ. These results suggest that Jak1 plays a nonredundant role in VSV infection, at least in Jak1−/− mouse-derived EFs in vitro.

Human AR partial JAK1 deficiency

No patient with AR complete JAK1 deficiency has yet been reported, making it impossible to predict the impact of such a deficiency on susceptibility to viral infection. Only one patient harboring a biallelic hypomorphic missense mutation of JAK1 has been published (97). Another patient with a compound heterozygous missense and splice mutation was recently discovered (Bustamante J. Casanova J.-L. et al. unpublished). These alleles resulted in different amounts of full-length and truncated JAK1 protein. In overexpression systems, all the alleles tested have resulted in an impairment of the response to IFN-γ, and a less severe defect of the response to IFN-α. consistent with these findings, the corresponding patients presented viral infections that were either mild or not clinically apparent. The first published patient had uncomplicated HPV and VZV infection with shingles. The predominant clinical manifestation was MSMD. Of note, one patient presented a mild developmental delay and short stature and died at the age of 23 years, from metastatic transitional cell carcinoma (97). Thus, consistent with the mild impact of partial JAK1 deficiency on IFN-α signaling, the two patients discovered to date display only mild viral infections.

TYK2 deficiency

Tyk2−/− mice

Tyk2−/− mice were generated by targeted disruption. They developed normally, with no gross hematopoietic abnormalities. The stimulation of Tyk2−/− mouse-derived EFs with IFN-α/IFN-β resulted in low levels of Stat2 phosphorylation (but this phosphorylation was not entirely abolished) and the coprecipitation of phosphorylated Stat1. Consistent with these findings, ISG induction after IFN-α/IFN-β treatment and IRF-1 induction after IFN-γ stimulation were weak, but not abolished in Tyk2−/− cells. Thus Tyk2−/− mice display only a partial impairment of the response to type I IFN (98). These cellular defects translate in vivo into Tyk2−/− mice being unable to clear Vaccinia virus from the spleen and displaying an impaired T-cell response to challenge with LCMV (98, 99). Intravenous VSV inoculation was fatal in 20% of Tyk2−/− mice, versus 66% of IFNAR1−/− mice, whereas WT mice were resistant to infection (48, 98). Following intranasal infection with VSV, 100% of Tyk2−/− and Tyk2K923E (kinase-inactive) mice died within seven, whereas < 40% of WT mice died within this time frame (100). This work also showed that kinase activity was essential for antiviral defense against viruses in vivo (100). EMCV infection resulted in 100% mortality in Tyk2−/− mice, 95% mortality in kinase-mutated mice and 60% mortality in WT mice (100). Likewise, MCMV infection resulted in higher mortality and earlier death in these mutant mice than in WT mice (101). Tyk2−/− mice are, thus, more susceptible to viral infection than WT mice, but less susceptible than Ifnar1−/− mice (Fig. 1)

Human AR TYK2 deficiency

Ten patients with AR complete TYK2 deficiency have been described (102–105). The mutations are deletions/insertions leading to a frameshift, and/or nonsense mutations resulting in a premature stop codon and complete TYK2 deficiency. Consistent with the scaffolding role of TYK2 for IFN-alpha R1, TYK2-deficient patient-derived EBV-transformed B cells (EBV-B cells) had low levels of IFN-alphaR1 expression (106). IFN-α/β signaling was reduced, but not abolished, in terms of STAT1 phosphorylation. IFN-α/β-induced ISG expression was unaffected in TYK2-deficient EBV-B cells. The EBV-B cells and HSV-T cells of the patients failed to control VSV replication upon IFN-alpha treatment, as reported by Minegishi for HSV (102). The residual signaling observed points to a partly redundant role for TYK2 in IFN-α/β signaling. TYK2-deficient cells responded normally to IFN-λ1 and IFN-λ3 (103). Severe and disseminated infections with intracellular bacteria, such as Salmonella, Brucella (in 3/10) and syndromic MSMD (7/10) predominate, attesting to the poor cellular responses to IL-12 and IL-23 (Table 2). Enhanced susceptibility to severe viral infection has been reported in Five of the 10 patients. Recurrent HSV gingivostomatitis, and recurrent HSV meningitis were described in 3 and 2/10 patients respectively. Molluscum contagiosum, chickenpox with shingles and parainfluenzavirus pneumonia were also reported. Seroconversion in the absence of clinical disease was reported for HHV6, parvoB19 and human influenza A virus in one patient (104, 105). Overall, the viral infection phenotype of TYK2 deficiency in humans is milder than that of Tyk2−/− mice and than those associated with human IFNAR1 or IFNAR2 deficiency, and infection can be controlled with adequate antiviral therapy. Moreover, there is no evidence of severe adverse effects of vaccination with live attenuated vaccine (LAV). The milder viral phenotype can be attributed, at least partly, to the residual TYK2-independent response to type I IFN in these patients (Fig 1)..

1. 3. Deficiencies of STAT1, STAT2, and IRF9

STAT1 deficiency

Stat1−/− mice

STAT1 knockout mice (Stat1−/−) display no response to type I, II or III IFNs, in terms of ISG induction (28, 29). STAT1 also governs responses to IL-27 (107, 108). Stat1−/− mice are susceptible to infection with intracellular bacteria and fungi, including cryptococci, and parasites (56, 109, 110). However, the viral phenotype predominates. Stat1−/− immortalized fibroblasts are not protected against the cytopathic effect of VSV in the presence or absence of IFN-α or IFN-γ (28). Accordingly, Stat1−/− mice succumb to infection with most viruses tested (Table 1). Indeed, this greater susceptibility to viral infection had already been observed upon natural infection with mouse hepatitis viruses during the generation of the KO mice, with such infections leading to the death of the Stat1−/− mice (28). Likewise, VSV causes lethal infections in these mice, with death occurring within two days of inoculation, with an LD50 six orders of magnitude lower than that for WT mice (28). Stat1−/− mice are also more susceptible to influenza A virus infection and to MCMV infection than WT mice, to a similar extent to Ifnar1−/− mice (52, 111). Depending on the route of infection and the strain, norovirus may be lethal in 100% of mice at d15, or may lead to chronic disseminated infection (112, 113). HSV-1 may cause a prolonged inflammatory disease of the cornea or may be 100% lethal (ip) (28, 29, 52, 86, 112–117). Stat1−/− mice are also susceptible to focal infection with mouse papillomavirus (118). A recent study of a murine SARS-CoV-2 model showed greater weight loss and lung disease in Stat1−/− mice (119). Thus, Stat1−/− mice display striking viral susceptibility, consistent with the observed impairment of their type I IFN responses, similar to that in Ifnar1−/− mice (Fig. 1).

Human AR complete STAT1 deficiency

Nine patients with autosomal recessive (AR) complete STAT1 deficiency have been described (120–125). Mutations are missense, small frameshift deletions/insertions, intronic essential splicing mutations, resulting in complete STAT1 deficiency (120–122, 124). Patient cells were unresponsive to type I, II, and III IFNs and IL-27. Clinically, all patients suffered multiple episodes of severe viral infections: recurrent cutaneous, gastrointestinal, and respiratory viral infections, and encephalitis. Mucocutaneous and CNS herpesvirus infections were reported in four of the nine patients. All patients who received live attenuated viral vaccines developed systemic infection, with fever, inflammation, skin eruption and encephalopathy (4/4 inoculated: 2 MMR 2 VZV)(123). Patients also suffered from syndromic MSMD (7/9) (120, 124, 126, 127). Three of the nine patients are still alive and all these patients have undergone HSCT. The other six patients died in infancy, one from EBV lymphoproliferative disease, and another from CMV reactivation post-hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) (122, 124, 125, 128). HLH was noted in three patients. Five patients with AR partial STAT1 deficiency have been described (129–131). Homozygosity for a hypomorphic STAT1 allele impairs, but does not abolish, STAT1 expression and function and IFN responses, resulting in a milder clinical phenotype, with HSV gingivostomatitis, severe VZV infections, and MSMD. Three patients reportedly received MMR without developing disease ((129, 131). Mortality is lower than that for patients with complete deficiencies, with four of the five patients still alive (the fifth patient died at the age of three years). Thus, AR complete STAT1 deficiency presents in infancy with recurrent severe viral infections, including herpes and LAV infection, and is lethal early in life unless treated by HSCT. There seems to be an enhanced risk of mortality post-HSCT, due to the reactivation of herpes viruses, highlighting the role of STAT1 in non-hematopoietic cells.

STAT2

Stat2−/− mice

The Stat2 gene was targeted for deletion by homologous recombination, to generate Stat2-null mice (Stat2−/−) (132). In line with findings from previously studied Stat2-deficient tumor lines, ISGF-3 target gene expression was abolished in primary embryonic fibroblasts (PEFs) from Stat2−/− mice. These mice display no developmental defects (133, 134). In a VSV model, the infection of PEFs from Stat2+/− and Stat−/− mice resulted in the production of 10 to 40 times more virus plaque-forming units than were observed with the wild type (132). IFN-α pretreatment provided protection (i.e. a decrease of three to four orders of magnitude in viral yield) in wild-type cells and Stat2+/− cells, but not in Stat2−/− cells. IFN-γ pretreatment did not result in an antiviral response in Stat2−/− cells upon infection with VSV. This is in line with the findings in Ifnar1−/− mice derived fibroblasts, where it was shown that at least in mouse fibroblasts, IFN- γ produces its antiviral activity in part through induction of type I IFN (23, 48). The reduced levels of Stat1 in the Stat2−/− cells are likely to additionally explain the finding of diminished antiviral response upon IFN- γ stimulation. Like Stat1-null mice, the Stat2-null mice succumbed to infection with doses of VSV six orders of magnitude lower than those lethal in wild-type and Stat2+/− mice (132). Moreover, Stat2−/− mice are much more susceptible to MCMV, severe fever thrombocytopenia syndrome virus, influenza virus, dengue virus, and Zika virus, than control mice (135–140). LCMV infection is lethal in STAT1−/− mice, but not in STAT2−/− or IRF9−/− mice, alluding to a role of IFN-γ-driven inflammation in fatal outcomes to this infection (141, 142). Overall, Stat2−/− mice display broad viral susceptibility, with greater mortality. However, death occurred later and mortality was lower in Stat2−/− mice than in Stat1−/− mice and Ifnar1−/− mice.

Human AR STAT2 deficiency

Ten patients with AR complete STAT2 deficiency have been reported (143–146). They carry mutations resulting in substitutions at essential splice sites, leading to aberrant splicing, and premature stop codons, leading to a complete loss of expression, phosphorylation and downstream ISG transcription. The predominant clinical phenotype is disseminated infection with vaccine-strain measles (mumps in 1 patient) following immunization with the live attenuated MMR vaccine (7/8 patients vaccinated, at the age of 12–19 months, residing in Belgium, the UK, Albania and Nepal). Moreover, 7/10 patients had an onset of severe disease in infancy, following infection with RSV, norovirus, coxsackievirus, adenovirus, or enterovirus (8/10). One patient developed prolonged CNS disease following EBV infection. CMV infection was uneventful in 2/10 and VZV infection was uncomplicating in three of four patients, but severe in the fourth patient. Two patients died from viral infections. Some of the patients reached adult age (Table 2). Excessive inflammation has been reported in four patients as “Kawasaki-like syndrome” or “HLH-like syndrome”. Two groups recently reported a homozygous STAT2 missense mutation (R148W/Q) leading to a STAT2 gain of function underlying fatal early-onset autoinflammation in three patients from two kindreds (147, 148). The mutation leads to a sustained type I IFN response due to ineffective binding of the mutated STAT2 to USP18, an essential step in the negative autofeedback loop in which USP18 sterically hinders the binding of JAK1 to IFNAR1 (147). In conclusion, complete AR STAT2 deficiency typically presents as disseminated LAV infection and recurrent natural viral infections. Penetrance is incomplete for several viral infections and for complicated live measles vaccine disease (145, 149, 150). The condition is less severe than human complete AR STAT1 deficiency, but more severe than IFNAR1 or IFNAR2 deficiency, at least for the patients described to date. This reflects the additional impairment of type II IFN and IL-27 signaling in STAT1 deficiency and the additional impairment of type III IFN signaling in STAT2 deficiency relative to IFNAR1 or IFNAR2 deficiency. The human phenotype is less severe than that observed in mice (Fig. 1)..

IRF9 deficiency

Irf9−/− mice

Like STAT2, IRF9 is crucial for the enhanced expression of most ISGs downstream from all type I and type III IFNs (151–153). Susceptibility to infection has not been studied extensively in Irf9 knockout mice (Irf9−/−) (153). In their seminal work Kimura et al created p48−/− mice and studied the antiviral state in these p48−/− cells. In p48−/− derived EFs and peritoneal macrophages, the induction of the antiviral state is abolished and dramatically impaired against at least three classes of viruses (EMCV, VSV, HSV) in response to IFN- α or IFN- γ respectively (153). The impaired clearance after in response to IFN- α was associated with poor capacity of IFN-α to induce ISGs. The authors go on to show that ISGF3 resembling DNA binding activity was found in IFN-γ stimulated wild type EFs but not p48−/− derived EFs. Bluyssen et al made similar observations in Vero cells as they showed that especially in the context of high concentrations of p48 and STAT1, ISRE binding activity was found, consisting of phosphorylated STAT1 and p48 (154). This is in agreement with findings in a human IRF9 deficient cell line (U2) by John et al (151). Irf9−/− DCs failed to respond to Toll-like receptor (TLR) 7 and 9 stimulation and displayed no upregulation of IRF7, an essential mediator of the type I IFN response, resulting in significantly lower levels of ISG expression than for the control. These defects were also present, but were more pronounced, in Ifnar1−/− mice, indicating a partial preservation of type I IFN signaling in Irf9−/− mice. Only one in vivo viral infection model has been described, in Irf9−/− mice. Huber et al. investigated the role of IRF9 in the response to infection with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) (155). Stat1−/− mice succumb to LCMV, whereas Irf9−/− mice, like Stat2−/− and Ifnar1−/− mice, survive but develop chronic infection and inflammation of the liver and central nervous system, accompanied by CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell exhaustion (141). The role of Irf9 has been studied only incompletely in in vivo models of viral infection in mice, but, at least for LCMV, the course of viral infection in Irf9−/− KO mice is similar to that in Tyk2−/− mice, Ifnar1−/− mice and Stat2−/− mice, resulting in a disseminated infection that is much less severe than that observed in Stat1−/− mice, in which ip injection of LCMV is 100% lethal.

Human AR IRF9 deficiency

A single kindred with AR complete IRF9 deficiency due to a homozygous missense mutation (991G>A) disrupting an essential splice site and leading to the skipping of exon 7 was described by Hernandez et al. (87). Another kindred with two affected siblings harboring a homozygous splice site mutation was recently reported. However, genetic studies and validation were incomplete for this kindred (156). In the first patient, the mutant protein was found in the cytoplasm, with small amounts in the nucleus of the patient’s SV40 fibroblasts, and in U2A fibrosarcoma cells transfected with the mutant, but it did not associate with STAT1 and STAT2 to generate the ISGF3 complex (157). Accordingly, the level of transcription of ISGs was lower in the patient’s fibroblasts and EBV-LCL cells than in control cells. The patient’s primary cells displayed enhanced susceptibility in vitro when challenged with influenza A virus (IAV) or vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV). Cell-intrinsic immunity to parainfluenza virus and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) was also found to be broadly impaired in IRF9-knockout control fibroblasts. Clinically, the patient suffered from life-threatening influenza pneumonia (158). The patient had also experienced biliary perforation and disseminated intravascular coagulation following MMR vaccination at the age of one year, and recurrent episodes of fever, with skin rash and septic shock, but with no identified infection. Nevertheless, the patient displayed seroconversion for HSV, CMV, HRV and EV, without severe clinical infection. The second patient had various severe viral infections, including enterovirus encephalitis and disseminated VZV vaccine-strain infection. Thus, the phenotype of human complete IRF9 deficiency encompasses a broad spectrum of viral susceptibility to both LAV and natural infections, similar to that observed in STAT2-deficient patients, with a broader susceptibility than observed in IFNAR1- and IFNAR2-deficient patients, and less severe than that observed in complete TYK2 deficiency and complete STAT1 deficiency. Comparisons with mice are hampered by a lack of in vivo viral infection models (Fig. 1).

Concluding remarks

We review here in vivo viral infection models in KO mice, and natural infection and infection following LAV inoculation in human patients with complete deficiencies of IFNAR1, IFNAR2, JAK1, TYK2, STAT1, STAT2 and IRF9. Several observations emerge. First, it is impossible to compare the various mouse models in an unambiguous manner, due to the diverse routes of infection used (i.p. versus i.d. versus s.c. versus i.v. versus i.n. versus inhaled) and the ensuing differences in the activation of type l and type III IFN signaling. Second, it is not straightforward to compare different viral strains of viruses as nicely reported for instance for Influenzavirus and several other (159)(Table 1). Third, there are intrinsic ISG deficiencies in several inbred mouse strains, as shown for Mxa (41). Fourth, in vivo viral infection with relevant viral pathogens has not been studied equally thoroughly in all KO models (e.g. in Irf9 deficiency). Based on cumulative disruption of type I IFNs, versus type I and II IFNs, and type I, II and III IFNs, it is currently thought that susceptibility to viral infection is lowest in Ifnar1−/− mutants, intermediate in Stat2−/−, Tyk2−/− and Irf9−/− mutants, and greatest in Stat1−/−mutants. Indeed, LCMV infection, which has been studied in all KO models, is lethal in Stat1−/− mutants, but causes only chronic infection in Stat2−/−, Tyk2−/−, Irf9−/− and Ifnar1−/− mice. Further formal comparisons will be necessary, to prove or disprove this hypothesis.

Human inborn errors of the type I IFN response pathway have revealed increasing susceptibility to viral infection from IFNAR1 and IFNAR2, through TYK2, STAT2 and IRF9, to STAT1 deficiencies. The unexpectedly narrow viral phenotype observed in IFNAR1, IFNAR2, STAT2 and IRF9 deficiencies remains incompletely explained. The bypassing of λ- IFN was initially put forward as an explanation of the severe phenotype following LAV inoculation in patients with IFNAR1/2 deficiencies (12, 87, 95). However, the description of HSE and severe COVID-19 in patients with IFNAR1 deficiency has demonstrated this hypothesis to be incorrect (88). Also, the finding that responses to IFN-γ are intact in human IFNAR1- and IFNAR2-deficient fibroblasts and that these responses provide partial protection against viral infection cannot provide a sufficient explanation. These findings suggest that type II IFN plays a role in antiviral immunity via STAT1-STAT1 homodimers, but specific type II IFN defects in humans (IFN-γ deficiency, and also all forms of complete and partial IFNGR1 and IFNGR2 deficiencies) have a phenotype of MSMD rather than severe viral infection (10, 160). Another unexplained observation is the incomplete penetrance for MMR disease in STAT2 and IFNAR1 deficiencies, and the lack of MMR disease observed in patients with complete TYK2 deficiency. The ultimate enigma is the previously healthy adults with AR IFNAR1 deficiency suffering from critical COVID-19 due to an inhibition of host type I IFN responses. Indeed, inborn errors of type I IFN induction and response underlie at least 3.5% of severe COVID-19 cases (45). In addition, at least 10% of severe cases have neutralizing autoantibodies against type I IFNs (mostly against the 13 subtypes of IFN-α and IFN-ω) (44). These observations suggests a critical role for type I IFN-independent restriction factors, such as DBR1 (161), SNORA31 (162), and EVER-CIB1(163), and perhaps other constitutive mechanisms (e.g. autophagy), in human antiviral host defense (164, 165).

The comparison of susceptibility to viral infection between in vivo models of viral infection in mice deficient for Ifnar1, Jak1, Tyk2, Stat1, Stat2, and Ifnar9 and humans with complete deficiencies of the corresponding proteins, as a means of deciphering the role of the type I IFN response pathway, is challenging. First, the signaling pathways of type I, II and III IFNs are intricately connected, in both mice and humans (17). Thus, for STAT1, STAT2, and IRF9, it is intrinsically difficult to delineate the contribution of defects limited to type I IFN immunity. There are also clear differences between species. For example, mouse hepatocytes do not respond to lambda interferon, and Tyk2−/− mouse cells display a milder impairment of type I IFN responses than their human counterparts, making any straightforward comparison difficult (98, 166). Many viruses are not equally pathogenic in both humans and mice (41). Furthermore, there are no in vivo models of complete Jak1 deficiency, due to the short lifespan of mice with this deficiency (96). Similarly, no human with complete JAK1 deficiency has ever been identified (97). Despite these and other challenges, a similar viral phenotype is emerging in mice and humans, at least for STAT1, STAT2 and TYK2 deficiencies, with STAT1 deficiency the most severe, and STAT2, IRF9 and TYK2 deficiencies associated with a milder phenotype, at least for the patients reported to date. However, human IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 deficiencies seem to differ from the ifnar1−/− mice, with mice displaying a broader phenotype, with greater mortality and dissemination reported for most of the viruses tested, including HSV and murine CMV (48–50, 87, 94, 95). The recent description of HSE and severe COVID-19 pneumonia in patients with IFNAR1 deficiency brings the mouse and human phenotypes closer together (167–170). Further descriptions of humans with inborn errors of immunity affecting the type I IFN response pathway, and discoveries of type I IFN-independent mechanisms of cell-intrinsic immunity to viruses will improve delineation of the essential and redundant roles of type I IFNs in host antiviral defense.

Acknowledgements

The Authors thank the patients and their parents. We thank Dr Giorgia Bucciol and Ms Jo Vencken for assistance. IM is a Senior Clinical Investigator at the Research Foundation – Flanders, and is supported by the CSL Behring Chair of Primary Immunodeficiencies, by the KU Leuven C1 Grant C16/18/007, by a VIB GC PID Grant, by the FWO Grants G0C8517N, G0B5120N and G0E8420N and by the Jeffrey Modell Foundation. This work is supported by ERN-RITA. The Laboratory of Human Genetics of Infectious Diseases is supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the Rockefeller University, the St. Giles Foundation, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R01AI088364, R01AI127564, R01AI143810, R01NS072381, R21AI137371, R21AI151663, R37AI095983) the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), NIH Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program (UL1TR001866), the Yale Center for Mendelian Genomics and the GSP Coordinating Center funded by the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) (UM1HG006504 and U24HG008956), the French National Research Agency (ANR) under the “Investments for the Future” program (ANR-10-IAHU-01) and the “Lymphocyte T helper (Th) cell differentiation in patients with inborn errors of immunity to Mycobacterium and/or Candida species” program (ANR-FNS LTh-MSMD-CMCD, ANR-18-CE93-0008-01), the Integrative Biology of Emerging Infectious Diseases Laboratory of Excellence (ANR-10-LABX-62-IBEID), the French Foundation for Medical Research (FRM) (EQU201903007798), Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (INSERM) and the University of Paris

Abbreviations

- 3’UTR

Three prime untranslated region

- Adv

Adenovirus

- AR

Autosomal Recessive

- CIB1

Calcium and Integrin-Binding Protein 1

- CMV

Cytomegalovirus

- CNS

Central Nervous System

- CNTF

Ciliary Neutrotrophic Factor

- CT-1

Cardiotrophin-1

- DBR1

Debranching Enzyme 1

- DNV

Dengue Virus

- EBV

Epstein-Barr Virus

- EFs

Embryonic Fibroblasts

- EMCV

Encephalomyocarditis Virus

- EV

Epidermodysplasia Verruciformis

- GAS

Gamma Activation Sites

- GP130

Glycoprotein 130

- HAV

Hepatitis A Virus

- HHV4

Human Herpes Virus – 4

- HHV6

Human Herpes Virus – 6

- HLH

Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis

- HMPV

Human Metapneumovirus

- HPV

Human Papillomavirus

- HRV

Human Rhinovirus

- HSCT

Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation

- HSE

Herpes Simplex Virus Encephalitis

- HSV

Herpes Simplex Virus

- HVS

Herpesvirus Saimiri

- IAV

Influenza A Virus

- IFN

Interferon

- IFNAR1

Interferon Alpha Receptor 1

- IFNAR2

Interferon Alpha Receptor 2

- IFNGR1

Interferon Gamma Receptor 1

- IFNGR2

Interferon Gamma Receptor 2

- IFNL4

Interferon Lambda 4

- IFNLR1

Interferon Lambda receptor 1

- IL

Interleukin

- IL10RB

Interleukin 10 Receptor Beta

- IRF7

Interferon Regulatory Factor 7

- IRF9

Interferon Regulatory factor 9

- ISG

Interferon Stimulated Genes

- ISGF3

Interferon Stimulated Gene Factor 3

- ISRE

Interferon Stimulated Response Element

- JAK1

Janus Kinase 1

- JEV

Japanese Encephalitis Virus

- KO mouse

Knockout mouse

- LAV

Live Attenuated Vaccine

- LCL

Lymphoblastoid Cell Lines

- LCMV

Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis Virus

- LD50

Median Lethal Dose for 50% of the subjects

- LIF

Lithium Floride

- LPS

Lipopolysaccharide

- MCMV

Murine Cytomegalovirus

- MHC

Major Histocompatibility Complex

- MMR

Measles Mumps Rubella vaccine

- MSMD

Mendelian Susceptibility to Mycobacterial Diseases

- MxA

Myxovirus Resistance Protein A

- NK

Natural Killer cells

- OSM

Oncostatin M

- ParvoB19

Parvovirus B19

- PEF

Primary Embryonic Fibroblasts

- PTK

Protein-Tyrosine Kinase

- RSV

Respiratory Syncytial Virus

- SARS-CoV-2

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2

- SNORA31

Small Nucleolar RNA

- SOCS

Suppressors of Cytokine Signaling

- STAT1

Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 1

- STAT2

Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 2

- SV40

Simian Virus 40

- TLR

Toll-like Receptor

- TYK2

Tyrosine Kinase 2

- USP18

Ubiquitin Specific Peptidase 18

- VSV

Vesicular Stomatitis Virus

- VEE

Venezuelan Equine Encephalitis

- VZV

Varicella Zoster Virus

- WT

Wild Type

- YFV 17D vaccination

Yellow Fever Virus 17D vaccination

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The Authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This article has been accepted for publication and undergone full peer review but has not been through the copyediting, typesetting, pagination and proofreading process, which may lead to differences between this version and the Version of Record. Please cite this article as doi:10.1002/eji.202048793.

References

- 1.Isaacs A, Lindenmann J. Virus interference. I. The interferon. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1957;147(927):258–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Isaacs A, Lindenmann J, Valentine RC. Virus interference. II. Some properties of interferon. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1957;147(927):268–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gresser I Production of interferon by suspensions of human leucocytes. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1961;108:799–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McNab F, Mayer-Barber K, Sher A, Wack A, O’Garra A. Type I interferons in infectious disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15(2):87–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gresser I Biologic effects of interferons. J Invest Dermatol. 1990;95(6 Suppl):66S–71S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crow YJ, Lebon P, Casanova JL, Gresser I. A Brief Historical Perspective on the Pathological Consequences of Excessive Type I Interferon Exposure In vivo. Journal of clinical immunology. 2018;38(6):694–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vilcek J Fifty years of interferon research: aiming at a moving target. Immunity. 2006;25(3):343–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wheelock EF. Interferon-like virus-inhibitor induced in human leukocytes by phytohemagglutinin. Science. 1965;149(3681):310–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nathan CF, Prendergast TJ, Wiebe ME, Stanley ER, Platzer E, Remold HG, et al. Activation of human macrophages. Comparison of other cytokines with interferon-gamma. J Exp Med. 1984;160(2):600–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bustamante J Mendelian susceptibility to mycobacterial disease: recent discoveries. Human genetics. 2020;139(6–7):993–1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hong M, Schwerk J, Lim C, Kell A, Jarret A, Pangallo J, et al. Interferon lambda 4 expression is suppressed by the host during viral infection. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2016;213(12):2539–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kotenko SV, Gallagher G, Baurin VV, Lewis-Antes A, Shen M, Shah NK, et al. IFN-lambdas mediate antiviral protection through a distinct class II cytokine receptor complex. Nat Immunol. 2003;4(1):69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sommereyns C, Paul S, Staeheli P, Michiels T. IFN-lambda (IFN-lambda) is expressed in a tissue-dependent fashion and primarily acts on epithelial cells in vivo. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4(3):e1000017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jaitin DA, Roisman LC, Jaks E, Gavutis M, Piehler J, Van der Heyden J, et al. Inquiring into the differential action of interferons (IFNs): an IFN-alpha2 mutant with enhanced affinity to IFNAR1 is functionally similar to IFN-beta. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26(5):1888–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Piehler J, Thomas C, Garcia KC, Schreiber G. Structural and dynamic determinants of type I interferon receptor assembly and their functional interpretation. Immunological reviews. 2012;250(1):317–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Darnell JE Jr. STATs and gene regulation. Science. 1997;277(5332):1630–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Darnell JE Jr., Kerr IM, Stark GR. Jak-STAT pathways and transcriptional activation in response to IFNs and other extracellular signaling proteins. Science. 1994;264(5164):1415–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stark GR, Kerr IM, Williams BR, Silverman RH, Schreiber RD. How cells respond to interferons. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:227–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levy DE, Marie IJ, Durbin JE. Induction and function of type I and III interferon in response to viral infection. Curr Opin Virol. 2011;1(6):476–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Briscoe J, Kohlhuber F, Muller M. JAKs and STATs branch out. Trends Cell Biol. 1996;6(9):336–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strehlow I, Schindler C. Amino-terminal signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) domains regulate nuclear translocation and STAT deactivation. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(43):28049–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wathelet MG, Lin CH, Parekh BS, Ronco LV, Howley PM, Maniatis T. Virus infection induces the assembly of coordinately activated transcription factors on the IFN-beta enhancer in vivo. Mol Cell. 1998;1(4):507–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takaoka A, Mitani Y, Suemori H, Sato M, Yokochi T, Noguchi S, et al. Cross talk between interferon-gamma and -alpha/beta signaling components in caveolar membrane domains. Science. 2000;288(5475):2357–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Platanias LC. Mechanisms of type-I- and type-II-interferon-mediated signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5(5):375–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suprunenko T, Hofer MJ. The emerging role of interferon regulatory factor 9 in the antiviral host response and beyond. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2016;29:35–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Negishi H, Taniguchi T, Yanai H. The Interferon (IFN) Class of Cytokines and the IFN Regulatory Factor (IRF) Transcription Factor Family. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2018;10(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kessler DS, Levy DE, Darnell JE, Jr. Two interferon-induced nuclear factors bind a single promoter element in interferon-stimulated genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85(22):8521–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Durbin JE, Hackenmiller R, Simon MC, Levy DE. Targeted disruption of the mouse Stat1 gene results in compromised innate immunity to viral disease. Cell. 1996;84(3):443–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meraz MA, White JM, Sheehan KC, Bach EA, Rodig SJ, Dighe AS, et al. Targeted disruption of the Stat1 gene in mice reveals unexpected physiologic specificity in the JAK-STAT signaling pathway. Cell. 1996;84(3):431–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haque SJ, Williams BR. Identification and characterization of an interferon (IFN)-stimulated response element-IFN-stimulated gene factor 3-independent signaling pathway for IFN-alpha. J Biol Chem. 1994;269(30):19523–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morrow AN, Schmeisser H, Tsuno T, Zoon KC. A novel role for IFN-stimulated gene factor 3II in IFN-gamma signaling and induction of antiviral activity in human cells. J Immunol. 2011;186(3):1685–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fleming SB. Viral Inhibition of the IFN-Induced JAK/STAT Signalling Pathway: Development of Live Attenuated Vaccines by Mutation of Viral-Encoded IFN-Antagonists. Vaccines (Basel). 2016;4(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alcais A, Quintana-Murci L, Thaler DS, Schurr E, Abel L, Casanova JL. Life-threatening infectious diseases of childhood: single-gene inborn errors of immunity? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1214:18–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Casanova JL, Abel L, Quintana-Murci L. Immunology Taught by Human Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor symposia on quantitative biology. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Casanova JL, Abel L. The human model: a genetic dissection of immunity to infection in natural conditions. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4(1):55–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Duncan CJA, Randall RE, Hambleton S. Genetic Lesions of Type I Interferon Signalling in Human Antiviral Immunity. Trends Genet. 2021;37(1):46–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Von Bernuth H, Picard C, Jin Z, Pankla R, Xiao H, Ku C-L, Chrabieh M, Ben Mustapha I, Ghandil P, Camcioglu Y, Vasconcelos J, Sirvent N, and 26 others.. Pyogenic bacterial infections in humans with MyD88 deficiency. . Science 2008;321:691–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fieschi C, Casanova JL. The role of interleukin-12 in human infectious diseases: only a faint signature. European journal of immunology. 2003;33(6):1461–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cypowyj S, Picard C, Marodi L, Casanova JL, Puel A. Immunity to infection in IL-17-deficient mice and humans. European journal of immunology. 2012;42(9):2246–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sancho-Shimizu VPdD R.; Jouanguy E; Zhang SY.; Casanova JL. Inborn errors of anti-viral interferon immunity in humans. Curr Opin Virol 2011;1(6):487–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haller O, Arnheiter H, Pavlovic J, Staeheli P. The Discovery of the Antiviral Resistance Gene Mx: A Story of Great Ideas, Great Failures, and Some Success. Annu Rev Virol. 2018;5(1):33–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ciancanelli MJ, Abel L, Zhang SY, Casanova JL. Host genetics of severe influenza: from mouse Mx1 to human IRF7. Current opinion in immunology. 2016;38:109–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Staeheli P, Haller O, Boll W, Lindenmann J, Weissmann C. Mx protein: constitutive expression in 3T3 cells transformed with cloned Mx cDNA confers selective resistance to influenza virus. Cell. 1986;44(1):147–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bastard P, Rosen LB, Zhang Q, Michailidis E, Hoffmann HH, Zhang Y, et al. Autoantibodies against type I IFNs in patients with life-threatening COVID-19. Science. 2020;370(6515). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang Q, Bastard P, Liu Z, Le Pen J, Moncada-Velez M, Chen J, et al. Inborn errors of type I IFN immunity in patients with life-threatening COVID-19. Science. 2020;370(6515). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang Q, Bastard P, Bolze A, Jouanguy E, Zhang SY, Effort CHG, et al. Life-Threatening COVID-19: Defective Interferons Unleash Excessive Inflammation. Med (N Y). 2020;1(1):14–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Uze G, Lutfalla G, Gresser I. Genetic transfer of a functional human interferon alpha receptor into mouse cells: cloning and expression of its cDNA. Cell. 1990;60(2):225–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Muller U, Steinhoff U, Reis LF, Hemmi S, Pavlovic J, Zinkernagel RM, et al. Functional role of type I and type II interferons in antiviral defense. Science. 1994;264(5167):1918–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hwang SY, Hertzog PJ, Holland KA, Sumarsono SH, Tymms MJ, Hamilton JA, et al. A null mutation in the gene encoding a type I interferon receptor component eliminates antiproliferative and antiviral responses to interferons alpha and beta and alters macrophage responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92(24):11284–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fenner JE, Starr R, Cornish AL, Zhang JG, Metcalf D, Schreiber RD, et al. Suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 regulates the immune response to infection by a unique inhibition of type I interferon activity. Nat Immunol. 2006;7(1):33–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ryman KD, Klimstra WB, Nguyen KB, Biron CA, Johnston RE. Alpha/beta interferon protects adult mice from fatal Sindbis virus infection and is an important determinant of cell and tissue tropism. Journal of virology. 2000;74(7):3366–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Garcia-Sastre A, Durbin RK, Zheng H, Palese P, Gertner R, Levy DE, et al. The role of interferon in influenza virus tissue tropism. J Virol. 1998;72(11):8550–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Price GE, Gaszewska-Mastarlarz A, Moskophidis D. The role of alpha/beta and gamma interferons in development of immunity to influenza A virus in mice. J Virol. 2000;74(9):3996–4003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Koerner I, Kochs G, Kalinke U, Weiss S, Staeheli P. Protective role of beta interferon in host defense against influenza A virus. Journal of virology. 2007;81(4):2025–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wessely R, Klingel K, Knowlton KU, Kandolf R. Cardioselective infection with coxsackievirus B3 requires intact type I interferon signaling: implications for mortality and early viral replication. Circulation. 2001;103(5):756–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.van den Broek MF, Muller U, Huang S, Zinkernagel RM, Aguet M. Immune defence in mice lacking type I and/or type II interferon receptors. Immunol Rev. 1995;148:5–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kuchinsky SC, Hawks SA, Mossel EC, Coutermarsh-Ott S, Duggal NK. Differential pathogenesis of Usutu virus isolates in mice. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14(10):e0008765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Martin-Acebes MA, Blazquez AB, Canas-Arranz R, Vazquez-Calvo A, Merino-Ramos T, Escribano-Romero E, et al. A recombinant DNA vaccine protects mice deficient in the alpha/beta interferon receptor against lethal challenge with Usutu virus. Vaccine. 2016;34(18):2066–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gerlach N, Gibbert K, Alter C, Nair S, Zelinskyy G, James CM, et al. Anti-retroviral effects of type I IFN subtypes in vivo. European journal of immunology. 2009;39(1):136–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zelinskyy G, Kraft AR, Schimmer S, Arndt T, Dittmer U. Kinetics of CD8+ effector T cell responses and induced CD4+ regulatory T cell responses during Friend retrovirus infection. European journal of immunology. 2006;36(10):2658–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bouloy M, Janzen C, Vialat P, Khun H, Pavlovic J, Huerre M, et al. Genetic evidence for an interferon-antagonistic function of rift valley fever virus nonstructural protein NSs. Journal of virology. 2001;75(3):1371–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lidbury BA, Mahalingam S. Specific ablation of antiviral gene expression in macrophages by antibody-dependent enhancement of Ross River virus infection. Journal of virology. 2000;74(18):8376–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Samuel M, Diamond MS. Alpha/beta interferon protects against lethal West Nile virus infection by restricting cellular tropism and enhancing neuronal survival. J Virol 2005;79(21):13350–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sheehan KC, Lazear HM, Diamond MS, Schreiber RD. Selective Blockade of Interferon-alpha and -beta Reveals Their Non-Redundant Functions in a Mouse Model of West Nile Virus Infection. PloS one. 2015;10(5):e0128636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shresta S, Kyle JL, Snider HM, Basavapatna M, Beatty PR, Harris E. Interferon-dependent immunity is essential for resistance to primary dengue virus infection in mice, whereas T- and B-cell-dependent immunity are less critical. Journal of virology. 2004;78(6):2701–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Meier A, Kirschning CJ, Nikolaus T, Wagner H, Heesemann J, Ebel F. Toll-like receptor (TLR) 2 and TLR4 are essential for Aspergillus-induced activation of murine macrophages. Cell Microbiol. 2003;5(8):561–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Aoki K, Shimada S, Simantini DS, Tun MM, Buerano CC, Morita K, et al. Type-I interferon response affects an inoculation dose-independent mortality in mice following Japanese encephalitis virus infection. Virol J. 2014;11:105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dowall SD, Graham VA, Rayner E, Atkinson B, Hall G, Watson RJ, et al. A Susceptible Mouse Model for Zika Virus Infection. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10(5):e0004658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lazear HM, Govero J, Smith AM, Platt DJ, Fernandez E, Miner JJ, et al. A Mouse Model of Zika Virus Pathogenesis. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;19(5):720–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rossi SL, Vasilakis N. Modeling Zika Virus Infection in Mice. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;19(1):4–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gibb TR, Bray M, Geisbert TW, Steele KE, Kell WM, Davis KJ, et al. Pathogenesis of experimental Ebola Zaire virus infection in BALB/c mice. J Comp Pathol. 2001;125(4):233–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lever MS, Piercy TJ, Steward JA, Eastaugh L, Smither SJ, Taylor C, et al. Lethality and pathogenesis of airborne infection with filoviruses in A129 alpha/beta −/− interferon receptor-deficient mice. J Med Microbiol. 2012;61(Pt 1):8–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rieger T, Merkler D, Gunther S. Infection of type I interferon receptor-deficient mice with various old world arenaviruses: a model for studying virulence and host species barriers. PloS one. 2013;8(8):e72290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]