Abstract

Background

The association between an increase in regular physical activity and a reduction in the risk of hypertension is well documented for non‐pregnant people. It has been suggested that exercise may help prevent pre‐eclampsia and its complications. Possible adverse effects of increased physical activity during pregnancy, particularly on the risk of preterm birth and fetal growth restriction, are unclear. It is, therefore, important to assess whether exercise reduces the risk of pre‐eclampsia and its complications and, if so, whether these benefits outweigh the risks.

Objectives

To assess the effects of exercise, or increased physical activity, on prevention of pre‐eclampsia and its complications.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (December 2005), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (The Cochrane Library 2005, Issue 1), and EMBASE (2002 to February 2005). We updated the search of the Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register on 18 January 2010and added the results to the awaiting classification section.

Selection criteria

Studies were included if these were randomised trials evaluating the effects of exercise or increased physical activity during pregnancy for women at risk of pre‐eclampsia.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently selected trials for inclusion and extracted data. Data were entered on Review Manager software for analysis, and double checked for accuracy.

Main results

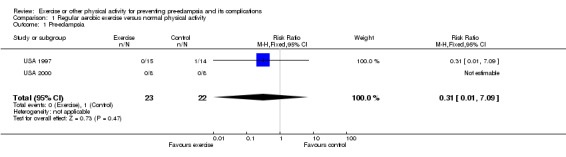

Two small, good quality trials (45 women) were included. Both compared moderate intensity regular aerobic exercise with maintenance of normal physical activity during pregnancy. The confidence intervals were wide and crossed the line of no effect for all reported outcomes including pre‐eclampsia (relative risk 0.31, 95% confidence interval 0.01 to 7.09).

Authors' conclusions

There is insufficient evidence for reliable conclusions about the effects of exercise on prevention of pre‐eclampsia and its complications.

[Note: The four citations in the awaiting classification section of the review may alter the conclusions of the review once assessed.]

Plain language summary

Exercise or other physical activity for preventing pre‐eclampsia and its complications

Not enough evidence to determine if exercise is helpful in preventing pre‐eclampsia and its complications.

Pre‐eclampsia is a serious complication of pregnancy occurring in about 2% to 8% of women. It is identified by increased blood pressure and protein in the urine, but women often suffer no symptoms initially. It can, through constriction of the blood vessels in the placenta, interfere with food and oxygen passing to the baby, thus inhibiting the baby's growth and causing the baby to be born too soon. Women can be affected through problems in their kidneys, liver, brain, and clotting system. Regular exercise in people who are not pregnant is known to have general health benefits, including increased blood flow and reduced risk of high blood pressure. So there is the potential for exercise to help prevent pregnant women developing pre‐eclampsia. There are, however, concerns that there may be adverse effects of exercise taken during pregnancy particularly the possibility of women giving birth too early. The review of trials found two small, well conducted studies but there was insufficient data to say what the potential benefits and harms might be. Further studies are needed, and in the meantime women will be guided by their own beliefs and reasoning, as well as those of their caregivers.

Background

The belief that women should remain physically active during pregnancy is prevalent in many cultures, and can be traced back to ancient times (Kitzinger 2000). It is thought, in many societies, that labour may be more difficult if women are not physically active during late pregnancy. For some, there is also a belief that being active will help keep the baby small enough to pass through the pelvis. Traditionally, the nature of women's work both within and outside the home has been such that most of the activities would have to be performed during pregnancy, as usual. Therefore, in most countries throughout history, only socially privileged women have had a choice about the level and type of physical activity they undertake during pregnancy. In the late twentieth century, as more women were comfortably off, and with the spread of labour saving machines to do household tasks, the concept of antenatal exercises developed. These exercises aim to prepare the woman for the birth. With changes in lifestyle in modern times, sport and exercise have also become major leisure activities for women. In addition, women increasingly have paid employment outside of the home that may include physical activity. When they become pregnant, women are often anxious about the safety to themselves and their unborn child of continuing these activities. Although there is a range of possible effects of exercise and other physical activity during pregnancy, this review deals primarily with those related to prevention of pre‐eclampsia, and its consequences.

Pre‐eclampsia is part of a spectrum of conditions known as the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Hypertension (high blood pressure) is common during pregnancy. Around 10% of women have raised blood pressure at some point before delivery. The hypertensive disorders of pregnancy are usually classified into four categories: (i) gestational hypertension: a rise in blood pressure during the second half of pregnancy; (ii) pre‐eclampsia: usually hypertension with proteinuria (protein in urine) during the second half of pregnancy; (iii) chronic hypertension: a rise in blood pressure before pregnancy or before 20 weeks' gestation, and (iv) pre‐eclampsia superimposed on chronic hypertension (NHBPEP 2000). Although the outcome of most such pregnancies is good, complications of pre‐eclampsia and severe hypertension are associated with a substantive increase in morbidity and mortality for both the woman and her baby (DH 2002). Pre‐eclampsia affects 2% to 8% of pregnancies (WHO 1988). It is a multisystem disorder, which may involve the brain, liver, kidneys, and placenta. Maternal complications include eclampsia, stroke, liver and kidney failure, and coagulopathy. Fortunately, such complications are rare. For the baby, there is an increased risk of poor growth and preterm birth. The cause of pre‐eclampsia is uncertain, but current belief is that reduced blood supply to the placenta leads to abnormal function of endothelial cells, possibly as a result of oxidative stress. Pre‐eclampsia is discussed in more detail in the generic protocol of interventions for prevention of pre‐eclampsia (Generic Protocol 2005).

The definitions of 'exercise' include exertion of muscles, limbs, etc, especially for health's sake; bodily, mental or spiritual training (Oxford English Dictionary). The term 'aerobic exercise' refers to energetic exercise that results in a rise in oxygen consumption (to around 40% to 80% of maximum), and heart rate (to around 50% to 90% of maximum). This level of activity is necessary for at least 10 minutes on at least two days per week to produce a 'training effect' of increasing or maintaining fitness in non‐pregnant people (ACSM 1998). Non‐aerobic exercise refers to exercise that improves strength of muscles and flexibility. There is no consensus on the ideal or acceptable level of exercise, or other physical activity, during pregnancy. In the USA, an accumulation of at least 30 minutes moderate exercise each day is recommended for improving the health and well‐being of non‐pregnant people (ACSM 1998), and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists advises that this is appropriate for pregnant women without medical or obstetric complications (ACOG 2002).

Blood pressure tends to rise during physical exertion. Nevertheless, the association between an increase in regular physical activity and a reduction in the risk of hypertension is well documented in the non‐pregnant population (DH 1996). During pregnancy there has been relatively little research about the possible effects of exercise on hypertension, or on the risk of pre‐eclampsia and its consequences. Regular aerobic exercise in healthy pregnant women improves or maintains physical fitness, but it is unclear whether there are any other effects for either the mother or the baby (Kramer 2002). Case‐control studies have suggested that occupational and recreational exercise may be associated with a reduction in the risk of pre‐eclampsia and gestational hypertension (Weissgerber 2004). These studies largely evaluated the effects of exercise before conception and during the first half of pregnancy for primiparous women. Other observational studies suggest that physical exertion, including standing for prolonged periods, and work inside and outside the home are associated with an increased risk of preterm birth and having a small‐for‐gestational age baby (Henriksen 1995; Launer 1990; Mamelle 1984). There is also a theoretical risk that changes in posture and balance, and the increased laxity of ligaments during pregnancy, may predispose to maternal injury during exercise (Sternfeld 1997).

It has been suggested that the physiological changes associated with regular exercise may protect against pre‐eclampsia (Weissgerber 2004). Postulated mechanisms for such an effect include enhanced placental growth and vascularity, possibly as an adaptive response to intermittent reductions in placental blood flow during exercise, reduced oxidative stress, and correction of vascular endothelial dysfunction, particularly with aerobic exercise (Clapp 2003; Jackson 1995; Powers 1999). Regular exercise is associated with an increase in plasma volume and cardiac output. Exercise has also been shown to lower plasma triglycerides (Williams 1996), inflammatory cytokines (Clapp 2000), and insulin resistance (Mayer‐Davis 1998), all of which are elevated in pre‐eclampsia (Roberts 2002; Seely 2003). Exercise is associated with emotional well‐being and reduction in stress and anxiety (Marquez 2000), and non‐aerobic relaxational exercises like yoga reduce blood pressure in non‐pregnant hypertensive patients (Patel 1975; Sundar 1984). It is possible that non‐aerobic exercise could also reduce the risk of hypertension during pregnancy, although this may not necessarily influence the risk of pre‐eclampsia. The relationship between physical activity, rest and the risk of pre‐eclampsia is unclear, although pregnant women with hypertension have often been advised to rest (Caetano 2004; Maloni 1998), with exercise discouraged (ACOG 2002). The effects of rest for women with normal blood pressure or with high blood pressure are covered by other Cochrane reviews (Meher 2005; Meher 2006). The aim of this review is to assess the effects of exercise and other physical activity before conception and during pregnancy on the risk of pre‐eclampsia and its complications.

Objectives

To assess the effects of exercise and other physical activity on the risk of pre‐eclampsia and its complications.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised trials evaluating the effects of exercise, or other physical activity, in women at risk of pre‐eclampsia were included. Trials with quasi‐random design were excluded.

Types of participants

Women were included if they were (a) pregnant women with normal blood pressure, (b) pregnant with high blood pressure but no proteinuria, and (c) planning a pregnancy and so at risk of developing pre‐eclampsia in their next pregnancy.

Whenever possible, pregnant women were grouped on the basis of their risk at trial entry as follows.

(1) Women with normal blood pressure

(a) High risk: defined as having one or more of the following: diabetes, renal disease, thrombophilia, autoimmune disease, previous severe or early onset pre‐eclampsia, or multiple pregnancy. (b) Moderate risk: defined as none of the above, but having either previous pre‐eclampsia that was not severe or early onset (or severity unspecified), or a first pregnancy and at least one of the following: teenager or over 35 years age, family history of pre‐eclampsia, obesity (body mass index greater than or equal to 30), increased sensitivity to Angiotensin II, positive roll‐over test, abnormal uterine artery doppler scan. (c) Low risk: defined as pregnancy that does not qualify as either high or moderate risk. (d) Undefined risk: when the risk is unclear or not specified.

(2) Women with high blood pressure, without proteinuria

These women are all at high risk of developing pre‐eclampsia. They fall into two groups. (a) Gestational hypertension: hypertension detected for the first time after 20 weeks' gestation, in the absence of proteinuria. (b) Chronic hypertension: essential or secondary hypertension detected prior to pregnancy or before 20 weeks' gestation. Some women with chronic hypertension may have long‐standing proteinuria due to their underlying disease. These women will be included as their proteinuria is not due to pre‐eclampsia.

If a trial included women with pre‐eclampsia as well as those with non‐proteinuric hypertension (gestational or chronic), where possible, we planned to include only the women with non‐proteinuric hypertension in the review. For trials that did not report results separately for the two groups, we planned to include the data but present it as a separate subgroup. However, we did not find any such trials.

Women with established pre‐eclampsia and those who were postpartum at trial entry were excluded.

Types of interventions

We included comparisons of: (i) any type of exercise, increased physical activity or advice to exercise with no exercise or normal physical activity; and (ii) one type of exercise, increased physical activity or advice to exercise with another.

All forms of exercise or physical activity were included, regardless of whether aerobic, or not, and whether occupational or recreational. Subgroup analysis were planned based on varying intensity of exercise, as broadly defined in Table 1.

1. Classification of physical activity intensity, for activity up to 60 minutes.

| Intensity | VO2 max % | Maximum heart rate % | RPE (Borg rating) | METS (reprod. age gp | Max volum. contr. % |

| Light | 20‐39 | 35‐54 | 10‐11 | 2.4‐4.7 | 30‐49 |

| Moderate | 40‐59 | 55‐69 | 12‐13 | 4.8‐7.1 | 50‐69 |

| Hard | 60‐84 | 70‐89 | 14‐16 | 7.2‐10.1 | 70‐84 |

| Very Hard | >/= 85 | >/= 90 | 17‐19 | >/= 10.2 | > 85 |

Studies were excluded if the intervention was exercise for less than 30 minutes per week, or if the exercise was for less than one week.

Types of outcome measures

The following outcomes were included. The definitions used for each outcome are summarised below. Trials that used acceptable variations of these definitions, or that did not define their outcomes were still included, and definitions, where available, were described in the table of 'Characteristics of included studies'. Studies were excluded if they did not report outcome data for either gestational hypertension or pre‐eclampsia. If an important outcome was not reported, whenever possible we contacted authors.

For the woman

Main outcome

(1) Pre‐eclampsia: defined as hypertension (blood pressure at least 140 mmHg systolic or 90 mmHg diastolic) with proteinuria (at least 300 mg protein in a 24 hour urine collection or 1+ on dipstick). For women with chronic hypertension and proteinuria at trial entry, pre‐eclampsia was defined as sudden worsening of proteinuria and/or hypertension, or other signs and symptoms of pre‐eclampsia after 20 weeks' gestation.

Other outcomes

(2) Death: during pregnancy or up to 42 days after the birth. (3) Severe morbidity related to pre‐eclampsia: including eclampsia, liver or renal failure, haemolysis elevated liver enzymes and low platelets syndrome, disseminated intravascular coagulation, stroke and pulmonary oedema. These outcomes will be reported individually, and as a composite measure where the information is available. (4) Severe pre‐eclampsia: pre‐eclampsia with two or more signs or symptoms of severe disease, such as severe hypertension, severe proteinuria (usually 3 g/24 h, or 3+ on dipstick), visual disturbances, exaggerated tendon reflexes, upper abdominal pain, impaired liver function tests, high serum creatinine, low platelets, fetal growth restriction, or reduced liquor volume. (5) Early onset of pre‐eclampsia: pre‐eclampsia at or before 33 completed weeks. (6) Severe hypertension: blood pressure at least 160 mmHg systolic or 110 mmHg diastolic. (7) Gestational hypertension: new onset of hypertension after 20 weeks' gestation (for women with normal blood pressure at trial entry). (8) Use of antihypertensive drugs or need for additional antihypertensive drugs. (9) Abruption of the placenta or antepartum haemorrhage. (10) Elective delivery: induction of labour or elective caesarean section. (11) Caesarean section: emergency and elective. (12) Postpartum haemorrhage: blood loss of 500 ml or more. (13) Side‐effects: any adverse events related to exercise, such as physical injury, exercise stopped due to side‐effects. (14) Use of health service resources: antenatal clinic visits, visit to day care unit, antenatal hospital admission, intensive care. (15) Women's experiences and views of exercise.

For the child

Main outcomes

(1) Death: including all deaths before birth and up to discharge from hospital. (2) Preterm birth: birth at or before 37 completed weeks' gestation. (3) Small‐for‐gestational age: growth below the 3rd centile, or lowest centile reported.

Other outcomes

(4) Apgar score at five minutes: low (less than seven) and very low (less than four) or lowest reported. (5) Endotracheal intubation or use of mechanical ventilation. (6) Neonatal morbidity: such as respiratory distress syndrome, chronic lung disease, sepsis, retinopathy of prematurity, and intraventricular haemorrhage. (7) Long‐term growth and development: blindness, deafness, seizures, poor growth, neurodevelopmental delay and cerebral palsy. (8) Side‐effects associated with exercise. (9) Use of hospital resources: admission to neonatal intensive care unit, duration of hospital stay after delivery.

Economic outcomes

Costs to health service resources: short term and long term for both mother and baby.

Costs to the woman, her family, and society associated with exercise.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (December 2005). We updated this search on 18 January 2010 and added the results to Studies awaiting classification.

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE;

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL and MEDLINE, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

In addition, we searched CENTRAL (The Cochrane Library 2005, Issue 1) and EMBASE (2002 to February 2005) by combining the terms 'exercise', 'physical activity' and 'yoga' with the CENTRAL and EMBASE search strategies listed in the generic protocol (Generic Protocol 2005).

We did not apply any language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed potentially eligible studies for inclusion. We resolved any differences in opinion by discussion.

Assessment of study quality

We assessed the quality of each trial using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Reviewers' Handbook (Alderson 2003). Methods used for generation of the randomisation sequence are described for each trial, where possible. Each study was assessed for quality of concealment of allocation, completeness of follow up, and blinding.

(1) Allocation concealment

A quality score for concealment of allocation was assigned to each trial using the following criteria: (A) adequate concealment of allocation, such as telephone randomisation, consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes; (B) unclear whether concealment of allocation was adequate; (C) inadequate concealment of allocation such as open random number tables, sealed envelopes that were not numbered and opaque.

Where the method of allocation concealment was unclear, whenever possible, we contacted trialists to provide further details.

(2) Completeness of follow up

Completeness of follow up was assessed using the following criteria: (A) less than 5% of participants excluded from analysis; (B) 5% to 10% of participants excluded from analysis; (C) more than 10% and up to and including 20% of participants excluded from analysis.

Studies were excluded if:

more than 20% of participants were excluded from analysis;

more than 10% of participants were not analysed in their randomised groups and it was not possible to restore participants to the correct group;

there was more than 10% difference in loss of participants between groups.

Data were analysed based on the group to which the participants were randomised, regardless of whether they received the allocated intervention or not. If data were missing, whenever possible, we sought clarification from the authors.

(3) Blinding

Blinding of participants is not possible, given the intervention under evaluation. Therefore, blinding was assessed only for the outcome assessor (yes/no/unclear or unspecified).

Data extraction and data entry

Two review authors independently extracted data. We entered data onto the Review Manager software (RevMan 2003), and double checked for accuracy.

Statistical analyses

We carried out statistical analyses using Review Manager (RevMan 2003). Results are presented as summary relative risk with 95% confidence intervals. The I2 statistic was used to assess heterogeneity between trials. In the absence of significant heterogeneity, results were pooled using a fixed‐effect model. If substantial heterogeneity was detected (I2 more than 50%), possible causes would be explored and subgroup analyses for the main outcomes performed. Heterogeneity that is not explained by subgroup analyses may be modelled using a random‐effects analysis, where appropriate.

Sensitivity analyses

We planned to do a sensitivity analysis for the main outcomes to explore the effects of trial quality based on concealment of allocation, by excluding studies with clearly inadequate allocation concealment (rated C). This analysis will be undertaken once sufficient data are available.

Subgroup analyses

Prespecified subgroup analyses for the main outcomes were based on the:

type of exercise: whether occupational, aerobic recreational, or non‐aerobic recreational;

timing of recruitment: whether preconception, at or before 20 weeks' gestation, or after 20 weeks;

intensity of exercise: whether light (oxygen consumption 20% to 39% or heart rate 35% to 54% of maximum), moderate (oxygen consumption 40% to 59% or heart rate 55% to 69% of maximum) or vigorous (oxygen consumption 60% to 85% or heart rate 70% to 90% of maximum), or their equivalents, as broadly classified in Table 1 (ACSM 1998).

We will conduct these subgroup analyses once sufficient data become available.

Results

Description of studies

Two small trials were included in this review. In one (USA 1997), all women had gestational diabetes, and in the other (USA 2000), they had either mild hypertension or a previous personal or family history of hypertension. Women in these trials were randomised between 18 and 34 weeks' gestation to moderate/high intensity aerobic exercise, carried out over a variable number of weeks. These trials are described in detail in the Characteristics of included studies table.

One ongoing study (USA 2002) is recruiting women with a previous history of pre‐eclampsia to assess the effects of moderate intensity aerobic exercise for prevention of recurrent pre‐eclampsia. Further details are in the Characteristics of ongoing studies table.

Ten studies were excluded. Five were observational studies, two were quasi‐randomised, two did not report relevant clinical outcomes, and in one study, 25% of participants were not randomised. Details of these studies are in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

(Four reports from an updated search in January 2010 have been added to Studies awaiting classification.)

Risk of bias in included studies

One study (USA 2000) was of good quality, with adequate allocation concealment, blinding of outcome assessment, and no losses to follow up. The other (USA 1997) had adequate concealment of allocation but there was no blinding of outcome assessment, and 12% of participants were excluded from the analysis (one in the exercise group and three in the control group).

Effects of interventions

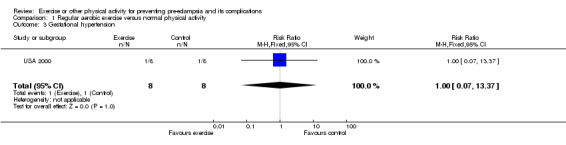

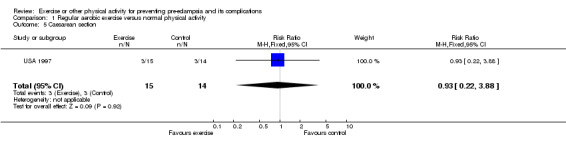

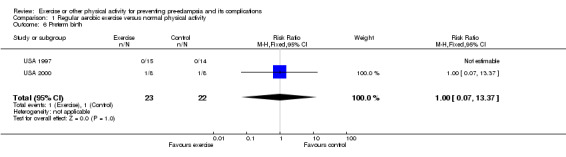

Two trials (45 women) compared moderate intensity aerobic exercise with normal physical activity during pregnancy in women who were at moderate to high risk of pre‐eclampsia. Even taken together, these trials are too small for any reliable conclusions about the effects of exercise. The confidence intervals are all wide, and cross the no‐effect line for all reported outcomes including pre‐eclampsia (two trials, 45 women; relative risk (RR) 0.31, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.01 to 7.09) and gestational hypertension (one trial, 16 women; RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.07 to 13.37).

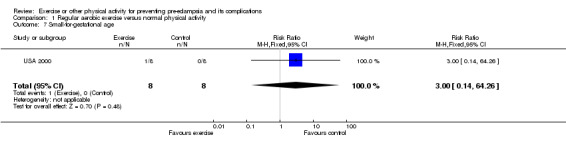

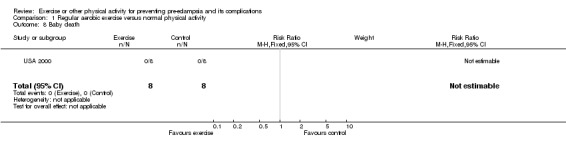

Other reported outcomes included preterm birth (two trials, 45 women; RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.07 to 13.37), small‐for‐gestational age babies (one trial, 16 women; RR 3.00, 95% CI 0.14 to 64.26), and caesarean section (one trial, 29 women; RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.22 to 3.88). There were no deaths in the baby in the one trial that reported this outcome. No data were available for any other outcomes.

Discussion

The aim of this review was to evaluate the effects of exercise or increased physical activity on prevention of pre‐eclampsia and its complications. Two small trials have compared the effects of regular moderate intensity aerobic exercise during pregnancy with maintenance of normal physical activity for women at moderate to high risk of pre‐eclampsia. In both studies, women appeared to have had good compliance with the exercise program. However, these trials are far too small to provide reliable information about the effects of exercise on prevention of pre‐eclampsia, or its complications.

Aerobic exercise appears to increase fitness during pregnancy (Kramer 2002). One study in this review also reported that cardiorespiratory fitness increased by 10% in the exercise group compared to 5% in the control group (USA 1997).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

At present, there is insufficient evidence to draw reliable conclusions about the possible effects of exercise on prevention of pre‐eclampsia and its complications. The decision about how much to exercise should therefore be left to individual women, in consultation with their clinicians.

Implications for research.

Women often request advice on the appropriate level of exercise or physical activity during pregnancy. In order to provide reliable advice, there is a need for good quality randomised trials with adequate sample size. Such trials should include pre‐eclampsia and its complications as reported outcomes.

[Note: The four citations in the awaiting classification section of the review may alter the conclusions of the review once assessed.]

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 18 January 2010 | Amended | Search updated. Four reports added to Studies awaiting classification (Ramirez‐Velez 2009; Yeo 2006; Yeo 2008; Yeo 2009). |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2005 Review first published: Issue 2, 2006

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 2 September 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format and amended contact details. |

Acknowledgements

Our thanks to Melissa Avery (USA 1997) and SeonAe Yeo (USA 2000) who have provided additional unpublished data.

As part of the pre‐publication editorial process, this review has been commented on by three peers (an editor and two referees who are external to the editorial team), one or more members of the Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's international panel of consumers and the Group's Statistical Adviser.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Regular aerobic exercise versus normal physical activity.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Pre‐eclampsia | 2 | 45 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.31 [0.01, 7.09] |

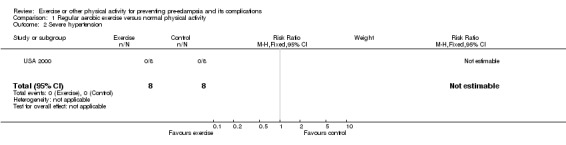

| 2 Severe hypertension | 1 | 16 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3 Gestational hypertension | 1 | 16 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.07, 13.37] |

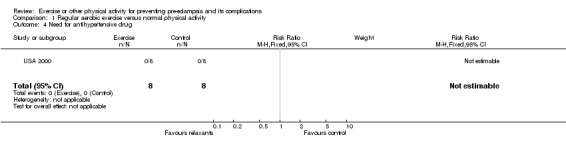

| 4 Need for antihypertensive drug | 1 | 16 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 5 Caesarean section | 1 | 29 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.22, 3.88] |

| 6 Preterm birth | 2 | 45 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.07, 13.37] |

| 7 Small‐for‐gestational age | 1 | 16 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.0 [0.14, 64.26] |

| 8 Baby death | 1 | 16 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Regular aerobic exercise versus normal physical activity, Outcome 1 Pre‐eclampsia.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Regular aerobic exercise versus normal physical activity, Outcome 2 Severe hypertension.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Regular aerobic exercise versus normal physical activity, Outcome 3 Gestational hypertension.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Regular aerobic exercise versus normal physical activity, Outcome 4 Need for antihypertensive drug.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Regular aerobic exercise versus normal physical activity, Outcome 5 Caesarean section.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Regular aerobic exercise versus normal physical activity, Outcome 6 Preterm birth.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Regular aerobic exercise versus normal physical activity, Outcome 7 Small‐for‐gestational age.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Regular aerobic exercise versus normal physical activity, Outcome 8 Baby death.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

USA 1997.

| Methods | Randomisation: block randomisation using random number table. Allocation concealment: opaque sealed envelopes. Blinding: outcome assessor not blinded. Follow up: 4 participants excluded: 1 in exercise group dropped out and 3 in the control group withdrawn for medical reasons (C). | |

| Participants | 33 pregnant women at < 34 weeks' gestation with gestational diabetes. Excluded: any other medical or obstetric complications (not specified), unable to read/write English, current exercise regimen for 30 minutes > 2 times/week. | |

| Interventions | Exp: moderate/hard intensity (70% maximum heart rate) exercise for 30 min 3‐4 times/week until delivery. 5 min warm up 20 min steady state, 5 min cool down). Cycle ergometer for 2 supervised sessions, plus walking or cycling unsupervised for 1‐2 sessions per week. Control: usual physical activity. Both groups had dietary counselling. |

|

| Outcomes | Maternal: PIH, caesarean section, blood glucose (mean), Hb A1C level, need for insulin, cardiorespiratory fitness, weight change. Baby: preterm birth, gestation at birth (mean), FHR patterns during exercise, birthweight (mean and > 4 kg), Apgar (median). | |

| Notes | Good compliance with exercise progam: experimental group exercised mean 3.0 (sd 0.6) times/week and controls 0.7 (sd 0.6) times/week. 144 women screened, 40 did not meet eligibility criteria, 68 declined, for 3 exercise recommended by carer. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

USA 2000.

| Methods | Randomisation: random number table. Allocation concealment: sealed numbered opaque envelopes. Blinding: outcome assessor blinded. Follow up: no losses (A). | |

| Participants | 16 women 18 years or older, at 18 weeks' gestation with either mild hypertension or a history of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy or a family history of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Excluded: women with renal disease, diabetes, multiple pregnancy, and vigorous exercisers with RPE > 14. | |

| Interventions | Exp: 45 min moderate (RPE = 13) intensity exercise 3 times/week for 10 weeks (warm up 5 min, steady state 30 min, and cool down 10 min). At exercise laboratory under supervision, on bicycle and treadmill. Controls: normal daily physical activity. |

|

| Outcomes | Maternal: PIH, pre‐eclampsia, severe hypertension, change in SBP and DBP over 10 weeks, change in percent body fat (mean). Child: preterm birth, small‐for‐gestational age, death. | |

| Notes | Good compliance with exercise program: range 77% to 100%, average attendance 90%. One eligible woman dropped out before randomisation in 4 week observation period. Information about concealment of allocation provided by authors. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

DBP: diastolic blood pressure Exp: experimental FHR: fetal heart rate Hb: haemoglobin min: minutes PIH: pregnancy‐induced hypertension RPE: rating of perceived exertion SBP: systolic blood pressure sd: standard deviation

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Bung 1991 | Pre‐eclampsia not reported in the outcomes. Methods: randomised trial. Participants: 41 women with gestational diabetes. Interventions: exercise and dietary therapy versus insulin and dietary therapy. Outcomes: maternal blood glucose, hypoglycemia, mode of delivery, fetal heart rate during exercise, gestation at delivery, birthweight and length, macrosomia, Apgar score, neonatal hypoglycaemia. |

| Collings 1983 | The first 25% of participants were not randomised, and data were not reported separately for the remaining 75%. Methods: first 5 women allowed to choose their own treatment, remaining women assigned to two groups in a 'random fashion'. No further information. Participants: 20 healthy pregnant women in 2nd trimester. Interventions: aerobic exercise (cycle ergometer) 3 times per week versus no regular exercise. Outcomes: physical fitness, birthweight, birth length, 1‐ and 5‐minutes Apgar scores, gestational age, preterm birth, stillbirth, neonatal mortality, low birthweight, small‐for‐gestational age, pre‐eclampsia, gestational weight gain, duration of labour, and caesarean section. Fetal heart rate. |

| Erkkola 1976 | Not a randomised trial. Methods: quasi‐random design (allocation by strict alternation in a consecutive series). Participants: 76 healthy primiparous women with singleton pregnancy. Interventions: training exercise versus no training. Outcomes: physical fitness, heart volume, birthweight, gestational age, pre‐eclampsia. |

| Jovanovic 1991 | No clinical outcomes reported. Method: randomised trial. Participants: 20 women with gestational diabetes. Interventions: dietary therapy plus upper extremity exercise versus dietary therapy alone. Outcomes: plasma glucose levels. |

| Little 1984 | Not a randomised trial. Method: quasi‐random design (women were assigned sequentially into 3 groups). Participants: 60 pregnant women with blood pressure >/= 135/85 on 2 occasions. Interventions: 3 arms. Yoga relaxation versus yoga relaxation and biofeedback versus no intervention. Outcomes: blood pressure, hospital admission, length of hospital stay, length of labour, proteinuria, birthweight, Apgar score, head circumference. |

| Marcoux 1989 | Not a randomised trial. Method: case‐control study. Participants: 172 women with pre‐eclampsia, 254 with gestational diabetes, and 505 controls. Variable assessed: leisure time physical activity. Outcome: risk of pre‐eclampsia and gestational hypertension. |

| Rauramo 1988 | Not a randomised trial (physiological study). Methods: cohort study. Participants: 13 women with hypertension, 10 with diabetes, and 8 with cholestasis. Intervention: a single episode of standardised exercise test. Outcomes: maternal heart rate and blood pressure, fetal heart rate, placental blood flow. |

| Saftlas 2004 | Not a randomised trial. Method: case‐control study. Participants: 44 women with pre‐eclampsia, 172 with gestational hypertension, and 2422 normotensive controls. Variable assessed: work and leisure time physical activity. Outcomes: risk of pre‐eclampsia and gestational hypertension. |

| Sorensen 2003 | Not a randomised trial. Method: case‐control study. Participants: 201 women with pre‐eclampsia and 383 normotensive controls. Variable assessed: recreational physical activity. Outcomes: risk of pre‐eclampsia. |

| Spinillo 1995 | Not a randomised trial. Method: case‐control study. Participants: 160 women with severe pre‐eclampsia and 320 controls. Variable assessed: physical activity at work. Outcome: risk of severe pre‐eclampsia. |

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

USA 2002.

| Trial name or title | Exercise intervention to reduce recurrent pre‐eclampsia. |

| Methods | |

| Participants | 320 multiparous pregnant women with a history of pre‐eclampsia in a previous pregnancy. |

| Interventions | Experimental: moderate intensity exercise for 30 minutes, 5 days a week. Additional short bouts of exercise encouraged (3‐10 minutes of walking). Controls: usual activity. |

| Outcomes | Recurrence of pre‐eclampsia, metabolic markers, health behavior in pregnancy, and self‐efficacy. |

| Starting date | 5 September 2000. |

| Contact information | Thelma Patrick, Magee Women's Hospital, Pittsburgh, USA. |

| Notes | Randomised trial. Project end: 31 May 2005. |

Contributions of authors

The protocol was drafted by Shireen Meher and Lelia Duley. Trials were assessed for inclusion by both review authors independently, and data were extracted and entered into the Review Manager software by Shireen Meher and double checked for accuracy by Lelia Duley.

The review was drafted by Shireen Meher and Lelia Duley.

Sources of support

Internal sources

The University of Liverpool, UK.

University of Oxford, UK.

External sources

Health Technology Assessment, UK.

Medical Research Council, UK.

Declarations of interest

None known.

Edited (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

USA 1997 {published and unpublished data}

- Avery MD, Leon AS, Kopher RA. Effects for a partially home‐based exercise program for women with gestational diabetes. Obstetrics & Gynecology 1997;89:10‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

USA 2000 {published and unpublished data}

- Yeo S, Steele N, Chang M‐C, Leclaire S, Rovis D, Hayashi R. Effect of exercise on blood pressure in pregnant women with a high risk of gestational hypertensive disorders. Journal of Reproductive Medicine 2000;45(4):293‐8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Bung 1991 {published data only}

- Bung P, Artal R, Khodiguian N, Kjos S. Exercise in gestational diabetes: an optional therapeutic approach. Diabetes 1991;40(Suppl 2):182‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Collings 1983 {published data only}

- Collings CA, Curet LB, Mullin JP. Maternal and fetal responses to a maternal aerobic exercise program. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1983;145:702‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer MS. Aerobic exercise for women during pregnancy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2002, Issue 2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000180] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Erkkola 1976 {published and unpublished data}

- Erkkola R. The influence of physical exercise during pregnancy upon physical work capacity and circulatory parameters. Scandinavian Journal of Clinical and Laboratory Investigation 1976;6:747‐59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jovanovic 1991 {published data only}

- Jovanovic‐Peterson L, Peterson CM. Is exercise safe of useful in gestational diabetic women?. Diabetes 1991;40(Suppl 2):179‐81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Little 1984 {published data only}

- Little B, Benson P, Beard R, Hayworth J, Hall F, Dewhurst J, et al. Treatment of hypertension in pregnancy by relaxation and biofeedback. Lancet 1984;1(8328):865‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Marcoux 1989 {published data only}

- Marcoux S, Brisson J, Fabia J. The effects of leisure time physical activity on the risk of pre‐eclampsia and gestational hypertension. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 1989;43(2):147‐52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Rauramo 1988 {published data only}

- Rauramo I, Forss M. The effects of exercise on placenta blood flow in pregnancies complicated by hypertension, diabetes, or intrahepatic cholestasis. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica 1988;67(1):15‐20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Saftlas 2004 {published data only}

- Saftlas AF, Logsden‐Sackett N, Wang W, Woolson R, Bracken MB. Work, leisure‐time physical activity, and risk of preeclampsia and gestational hypertension. American Journal of Epidemiology 2004;160(8):758‐65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sorensen 2003 {published data only}

- Sorensen TK, Williams MA, Lee IM, Dashow EE, Thompson ML, Luthy DA. Recreational physical activity during pregnancy and risk of pre‐eclampsia. Hypertension 2003;41(6):1273‐80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Spinillo 1995 {published data only}

- Spinillo A, Capuzzo E, Colonna L, Piazzi G, Nicola S, Baltaro F. The effect of work activity in pregnancy on the risk of severe preeclampsia. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 1995;35(4):380‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies awaiting assessment

Ramirez‐Velez 2009 {published data only}

- Ramirez‐Velez R, Aguilar AC, Mosquera M, Garcia RG, Reyes LM, Lopez‐Jaramillo P. Clinical trial to assess the effect of physical exercise on endothelial function and insulin resistance in pregnant women. Trials 2009;10:104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Yeo 2006 {published data only}

- Yeo S. A randomized comparative trial of the efficacy and safety of exercise during pregnancy: design and methods. Contemporary Clinical Trials 2006;27(6):531‐40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Yeo 2008 {published data only}

- Yeo S, Davidge S, Ronis DL, Antonakos CL, Hayashi R, O'Leary S. A comparison of walking versus stretching exercises to reduce the incidence of preeclampsia: a randomized clinical trial. Hypertension in Pregnancy 2008;27(2):113‐30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Yeo 2009 {published data only}

- Yeo S. Adherence to walking or stretching, and risk of preeclampsia in sedentary pregnant women. Research in Nursing & Health 2009;32(4):379‐90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to ongoing studies

USA 2002 {published data only}

- Patrick T. Exercise intervention to reduce recurrent pre‐eclampsia. http://commons.cit.nih.gov.crisp (accessed May 2002).

Additional references

ACOG 2002

- ACOG Committe Opinion No. 267. Exercise during pregnancy and postpartum period. Obstetrics & Gynecology 2002;99(1):171‐3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

ACSM 1998

- Pollock ML, Gaesser GA, Butcher JD, Despres J‐P, Dishman RK, Franklin BA, et al. ACSM position stand: the recommended quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory and muscular fitness and flexibility in healthy adults. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 1998;30(6):975‐92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Alderson 2003

- Alderson P, Green S, Higgins JPT, editors. Cochrane Reviewers' Handbook 4.2.2 [updated March 2004]. In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 1, 2004. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Caetano 2004

- Caetano M, Ornstein MP, Dadelszen P, Hannah ME, Logan A, Gruslin A, et al. A survey of Canadian practitioners regarding the management of the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Hypertension in Pregnancy 2004;23(1):61‐74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Clapp 2000

- Clapp III JF, Kiess W. Effects of pregnancy and exercise on concentrations of metabolic markers tumour necrosis factor alpha and leptin. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2000;182:300‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Clapp 2003

- Clapp JF 3rd. The effects of maternal exercise on fetal oxygenation and feto‐placental growth. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology 2003;110:S80‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

DH 1996

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Physical activity and health: a report of the Surgeon General. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Atlanta: CDC, 1996. [Google Scholar]

DH 2002

- Department of Health, Scottish Executive Health Department and Department of Health, Social Services, Public Safety. Northern Ireland. Why mothers die. The sixth report on confidential enquiries into maternal deaths in the United Kingdom 2000‐2002. London: RCOG Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

Generic Protocol 2005

- Meher S, Duley L, Prevention of Pre‐eclampsia Cochrane Review Authors. Prevention of pre‐eclampsia and its consequences: generic protocol. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2005, Issue 2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD005301] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Henriksen 1995

- Henriksen TB, Hedegaard M, Secher NJ, Wilcox AJ. Standing at work and preterm delivery. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 1995;102:198‐206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jackson 1995

- Jackson MR, Gott P, Lye SJ, Knox Ritchie JW, Clapp III JF. The effects of maternal aerobic exercise on human placental development: placental volumetric composition and surface areas. Placenta 1995;16:179‐91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kitzinger 2000

- Kitzinger S. Rediscovering birth. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 2000. [Google Scholar]

Kramer 2002

- Kramer MS. Aerobic exercise for women during pregnancy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2002, Issue 2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000180] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Launer 1990

- Launer LJ, Villar J, Kestler E, Onis M. The effect of maternal work on fetal growth and duration of pregnancy: a prospective study. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 1990;97:62‐70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Maloni 1998

- Maloni JA, Cohen WA, Kane JH. Prescription of activity restriction to treat high‐risk pregnancies. Journal of Women's Health 1998;7(3):351‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mamelle 1984

- Mamelle N, Laumon B, Lazar P. Prematurity and occupational activity during pregnancy. American Journal of Epidemiology 1984;119(3):309‐22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Marquez 2000

- Marquez‐Sterling S, Perry AC, Kaplan TA, Halberstein RA, Signorile JF. Physical and psychological changes with vigorous exercise in sedentary primigravida. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 2000;32:58‐62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mayer‐Davis 1998

- Mayer‐Davis EJ, D'Agostino R Jr, Karter AJ, Haffner SM, Rewers MJ, Saad M, et al. Intensity and amount of physical exercise in relation to insulin sensitivity. JAMA 1998;279:669‐74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Meher 2005

- Meher S, Abalos E, Carroli G. Bed rest with or without hospitalisation for hypertension during pregnancy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2005, Issue 4. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003514.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Meher 2006

- Meher S, Duley L. Rest during pregnancy for preventing pre‐eclampsia and its complications in women with normal blood pressure. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2006, Issue 2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD005939] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

NHBPEP 2000

- Gifford RW Jr, August PA, Cunningham G, Green LA, Lindhemier MD, McNellis D, et al. Report of the national high blood pressure education program working group on high blood pressure in pregnancy. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2000;183 Suppl:1‐22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Patel 1975

- Patel C, North WRS. Randomised controlled trial of yoga and biofeedback in management of hypertension. Lancet 1975;2:93‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Powers 1999

- Powers SK, Ji LL, Leeuwenburgh C. Exercise training‐induced alterations in skeletal muscle antioxidant capacity: a brief review. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 1999;31(7):987‐97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

RevMan 2003 [Computer program]

- The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager (RevMan). Version 4.2 for Windows. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2003.

Roberts 2002

- Roberts JM, Lain KY. Recent insights into the pathogenesis of pre‐eclampsia. Placenta 2002;23:359‐72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Seely 2003

- Seely EW, Solomon CG. Insulin resistance and its potential role in pregnancy‐induced hypertension. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2003;88(6):2393‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sternfeld 1997

- Sternfeld B. Physical activity and pregnancy outcome: review and recommendations. Sports Medicine 1997;23(1):33‐47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sundar 1984

- Sundar S, Agrawal SK, Singh VP, Bhattachary SK, Udupa KN. Role of yoga in management of essential hypertension. Acta Cardiology 1984;39(3):203‐8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Weissgerber 2004

- Weissgerber TL, Wolfe LA, Davies GAL. The role of regular physical activity in preeclampsia prevention. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 2004;36(12):2024‐31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

WHO 1988

- World Health Organization International Collaborative Study of Hypertensive Disorders in Pregnancy. Geographic variation in the incidence of hypertension in pregnancy. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1988;158:80‐3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Williams 1996

- Williams PT. High density lipoprotein cholesterol and other risk factors for coronary heart disease in female runners. New England Journal of Medicine 1996;334:1298‐303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]