Abstract

Objectives:

Testing remains critical for identifying pediatric cases of COVID-19 and as a public health intervention to contain infections. We surveyed US parents to measure the proportion of children tested for COVID-19 since the start of the pandemic, preferred testing venues for children, and acceptability of school-based COVID-19 testing.

Methods:

We conducted an online survey of 2074 US parents of children aged ≤12 years in March 2021. We applied survey weights to generate national estimates, and we used Rao–Scott adjusted Pearson χ2 tests to compare incidence by selected sociodemographic characteristics. We used Poisson regression models with robust SEs to estimate adjusted risk ratios (aRRs) of pediatric testing.

Results:

Among US parents, 35.9% reported their youngest child had ever been tested for COVID-19. Parents who were female versus male (aRR = 0.69; 95% CI, 0.60-0.79), Asian versus non-Hispanic White (aRR = 0.58; 95% CI, 0.39-0.87), and from the Midwest versus the Northeast (aRR = 0.76; 95% CI, 0.63-0.91) were less likely to report testing of a child. Children who had health insurance versus no health insurance (aRR = 1.38; 95% CI, 1.05-1.81), were attending in-person school/daycare versus not attending (aRR = 1.67; 95% CI, 1.43-1.95), and were from households with annual household income ≥$100 000 versus income <$50 000-$99 999 (aRR = 1.19; 95% CI, 1.02-1.40) were more likely to have tested for COVID-19. Half of parents (52.7%) reported the pediatrician’s office as the most preferred testing venue, and 50.6% said they would allow their youngest child to be tested for COVID-19 at school/daycare if required.

Conclusions:

Greater efforts are needed to ensure access to COVID-19 testing for US children, including those without health insurance.

Keywords: COVID-19, children, pediatric testing, testing venues, school-based testing

As of mid-September 2021, more than 5.7 million children in the United States had been diagnosed with COVID-19 and approximately 500 pediatric deaths had occurred. 1 Since April 2021, children have become an increasing portion of all diagnosed cases of COVID-19 in the United States. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, since the start of the pandemic, children represented 15.7% of all newly diagnosed COVID-19 cases, whereas during September 16-23, 2021, they accounted for 26.7% (n = 206 864 new pediatric infections). 1 Absolute numbers of COVID-19 cases in the United States began to sharply increase starting in July 2021, including among children, fueled by reopening and the emergence of the highly contagious B.1.617.2 (Delta) variant.2,3

Although most children infected with COVID-19 experience mild symptoms and have markedly lower mortality than adults, COVID-19 infection can lead to multi-inflammatory syndrome in children, and some infected children experience “long COVID,” similar to adults, with persistent symptoms after infection.4-6 Diagnosing infections in children is critical for providing appropriate care and for helping to contain the spread of COVID-19, including in school and daycare settings. 7 However, children remain a low proportion of all people tested in the United States. Data from September 16-23, 2021, showed that in 11 states, of all COVID-19 tests performed, the proportion of tests in children ranged from 11.4% to 22.0%. 1 Test positivity (the proportion of positive test results) among children ranged from 5.0% to 18.0% during this period, compared with a national average of 6.5% test positivity across all age groups in the United States during the last week of September.1,2

Few studies have examined testing coverage among US children, and routinely reported surveillance data on testing generally capture only information on age and few other characteristics. 8 A study of testing data from a network of urgent care centers in New York City found that the number of children aged 0-14 years tested for COVID-19 increased from early in the pandemic (March–June 2020) to later in the pandemic (October 2020–January 2021). The analysis also found that the highest seropositivity for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies among all age groups was in children aged 5-9 years (26.8%) and children and adolescents aged 10-14 years (27.3%), whereas test positivity (ie, current infection) was similar between children and adults. 9 Low diagnostic testing rates but high seropositivity among children and younger adolescents suggest that they were infected during the first wave but may not have been tested because of limited testing availability, having milder symptoms, or being asymptomatic. 10

To provide more in-depth information about COVID-19 testing in pediatric populations in the United States, we conducted an online survey of parents to determine the proportion of children who had been tested since the start of the pandemic. We also asked parents to report preferred testing venues and whether they would allow their child to be tested for COVID-19 at school or daycare.

Methods

We conducted an online cross-sectional national survey of US parents and caregivers (hereinafter, parents). Recruitment was conducted through a Qualtrics panel, which sources participants from multiple nonprobability survey panels composed of parents identified through social media platforms and parent networks (ie, business-to-business partners used by Qualtrics). 11 All participation was voluntary and no incentives were provided. Eligible participants were English- and Spanish-speaking adults aged ≥18 years identifying as a primary caregiver of a child aged ≤12 years. We followed the American Association for Public Opinion Research guidelines for quota-based sampling to calculate survey weights and estimate national estimates. 12 We used 2019 US Census data 13 on sex, race and ethnicity, education, and region to develop sample quotas reflecting the population of US parents of children aged ≤12 years. Data were collected from March 9 through April 2, 2021. The institutional review board of the City University of New York Graduate School of Public Health and Health Policy provided ethical approval.

For the survey, parents reported information about the youngest child living in the household. Outcomes were the proportion of parents reporting a child tested for COVID-19 (“Has your child ever been tested for COVID-19?”) and where parents would take their child for testing (“If your child needs testing for COVID-19 in the future, where would you take him/her to be tested?”), which allowed for multiple response options (ie, “Select all that apply”) including pediatrician’s office, urgent care, hospital, drive-through testing clinic, health department testing site, other, and don’t know. A separate question asked about acceptance of school-based testing (“If your child’s school or daycare required COVID-19 testing on a random basis, would you allow your child to be tested at school or daycare?”). Parents also reported demographic characteristics for themselves and their child as well as household information.

Survey weights were used during the analyses to generate national estimates among US parents. We calculated unweighted frequencies and weighted percentages for the sample and cumulative incidence estimates for testing among children aged ≤12 years, parents’ preferred testing venues, and acceptance of school/daycare testing. We used Rao–Scott adjusted Pearson χ2 tests to compare incidence of testing and preferred testing venues by selected characteristics. We used modified Poisson regression models with robust SEs and accounting for survey weights to estimate adjusted risk ratios (aRRs) of COVID-19 testing, adjusted for demographic and household characteristics. P < .05 was considered significant.

Results

Of 2074 US parents surveyed, 35.9% reported their youngest child (median child age, 4.8 y; interquartile range [IQR], 1.7-8.3) had ever been tested for COVID-19 (Table 1). Almost all children (92.0%) were reported to have health insurance that covered some or all costs of physician visits, and nearly half (49.8%) were attending school or daycare ≥1 day per week in March 2021. In adjusted models, parents who were female versus male (aRR = 0.69; 95% CI, 0.60-0.79), Asian versus non-Hispanic White (aRR = 0.58; 95% CI, 0.39-0.87), and from the Midwest versus the Northeast (aRR = 0.76; 95% CI, 0.63-0.91) were less likely to report a child having been tested for COVID-19. Children who had health insurance versus no health insurance (aRR = 1.38; 95% CI, 1.05-1.81), were attending in-person school/daycare versus not attending (aRR = 1.67; 95% CI, 1.43-1.95), and were from households with annual household income ≥$100 000 versus <$50 000-$99 999 (aRR = 1.19; 95% CI, 1.02-1.40) were more likely to have been tested for COVID-19.

Table 1.

Characteristics of children aged ≤12 years and their parents, estimated cumulative incidence of testing for SARS-CoV-2, and adjusted risk ratios (aRRs) for SARS-CoV-2 testing (vs not testing), United States, March 2021 a

| Characteristic | Sample, no. (%) b | Children ever tested for COVID-19 |

Adjusted risk of COVID-19 testing in children

e

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % c (95% CI) | P value d | aRR (95% CI) | P value d | ||

| Total sample | 2074 (100.0) | 35.9 (33.5-38.3) | — | — | |

| Child | |||||

| Age, median (IQR), y | 4.8 (1.7-8.3) | 5.7 (2.5-9.0) | — | — | |

| Age group, y | .001 | ||||

| <2 | 371 (18.6) | 28.8 (23.2-34.4) | 1 [Reference] | ||

| 2-6 | 831 (40.3) | 33.0 (29.3-36.8) | 0.98 (0.78-1.22) | .85 | |

| 7-12 | 872 (41.1) | 42.0 (32.2-45.7) | 1.02 (0.82-1.29) | .83 | |

| Sex | .23 | ||||

| Female | 1046 (49.5) | 34.0 (34.4-41.4) | 0.93 (0.82-1.06) | .29 | |

| Male | 1022 (50.3) | 37.9 (30.6-37.3) | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Missing f | 6 (0.2) | — | — | ||

| Race and ethnicity g | .14 | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 1099 (50.5) | 38.6 (35.3-42.0) | |||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 200 (10.6) | 34.6 (27.2-41.9) | |||

| Asian | 99 (3.7) | 23.6 (13.9-33.2) | |||

| Hispanic | 488 (25.9) | 35.3 (30.2-40.3) | |||

| Non-Hispanic Other h | 188 (9.3) | 29.4 (21.9-36.9) | |||

| Has health insurance | <.001 | ||||

| Yes | 1914 (92.0) | 36.7 (34.2-39.2) | 1.38 (1.05-1.81) | .02 | |

| No | 149 (7.4) | 27.6 (19.8-35.4) | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Don’t know f | 11 (0.6) | — | — | ||

| Attending in-person school/daycare ≥1 day per week | <.001 | ||||

| Yes | 1098 (49.8) | 46.8 (43.5-50.2) | 1.67 (1.43-1.95) | <.001 | |

| No | 969 (50.0) | 25.0 (21.8-28.3) | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Don’t know f | 7 (0.2) | — | — | ||

| Parent | |||||

| Age, y | .13 | ||||

| 18-29 | 366 (20.3) | 31.7 (26.0-37.4) | 1.09 (0.84-1.41) | .53 | |

| 30-44 | 1387 (65.1) | 37.0 (34.1-39.9) | 1.01 (0.84-1.21) | .91 | |

| ≥45 | 321 (14.6) | 36.9 (30.6-43.1) | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Sex | <.001 | ||||

| Female | 1270 (60.1) | 28.3 (25.3-31.2) | 0.69 (0.60-0.79) | <.001 | |

| Male | 794 (39.3) | 47.6 (43.5-51.6) | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Transgender/otherf,i | 10 (0.6) | — | — | ||

| Race and ethnicity | .02 | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 1159 (53.3) | 37.7 (34.5-40.9) | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 219 (11.3) | 31.9 (25.5-38.4) | 0.92 (0.74-1.15) | .48 | |

| Asian | 129 (4.6) | 18.5 (11.3-25.7) | 0.58 (0.39-0.87) | .01 | |

| Hispanic | 467 (25.4) | 37.1 (31.7-42.5) | 1.07 (0.91-1.25) | .44 | |

| Non-Hispanic Other h | 100 (5.4) | 36.1 (25.0-47.1) | 1.19 (0.87-1.63) | .28 | |

| Education (highest level completed) | .03 | ||||

| ≤High school | 482 (30.7) | 30.6 (25.4-35.7) | 1.06 (0.87-1.30) | .55 | |

| Some college | 546 (31.4) | 37.8 (33.6-42.1) | 1.17 (1.02-1.36) | .03 | |

| ≥Completed college | 1015 (36.5) | 38.0 (34.8-41.3) | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Missing f | 31 (1.4) | — | — | ||

| Household | |||||

| No. of children aged ≤12 y | .08 | ||||

| 1 | 1059 (50.8) | 36.8 (33.5-40.1) | 1 [Reference] | ||

| 2 | 751 (34.8) | 37.3 (33.2-41.3) | 0.99 (0.86-1.14) | .87 | |

| ≥3 | 264 (14.4) | 29.5 (0-1.8) | 0.86 (0.68-1.08) | .20 | |

| Annual household income, $ | <.001 | ||||

| <25 000 | 331 (20.3) | 29.7 (23.9-35.5) | 1.00 (0.79-1.26) | .99 | |

| 25 000-49 999 | 472 (24.6) | 31.8 (26.9-36.7) | 0.98 (0.81-1.19) | .84 | |

| 50 000-99 999 | 587 (27.4) | 34.5 (30.2-38.8) | 1 [Reference] | ||

| ≥100 000 | 617 (23.9) | 48.6 (44.1-53.2) | 1.19 (1.02-1.40) | .03 | |

| Missing f | 67 (3.8) | — | — | ||

| Region | .02 | ||||

| Northeast | 550 (15.7) | 42.1 (37.4-46.8) | 1 [Reference] | ||

| South | 684 (39.0) | 34.3 (30.2-38.3) | 0.87 (0.74-1.02) | .08 | |

| Midwest | 442 (21.0) | 30.3 (25.7-34.9) | 0.76 (0.63-0.91) | .002 | |

| West | 398 (24.3) | 39.4 (33.9-44.9) | 0.95 (0.81-1.13) | .58 | |

Abbreviations: —, does not apply; IQR, interquartile range.

Data reported by parents through online survey.

Weighted percentages are estimates of parents’ reporting history of SARS-CoV-2 testing for their youngest child.

Survey weights applied to sample to represent US population of parents by sex, race and ethnicity, education, and region.

P values from Rao–Scott adjusted Pearson χ2 tests to compare expected with observed frequencies among groups by characteristic for parental report of child SARS-CoV-2 testing. P < .05 was considered significant.

Adjusted models include all variables shown in the table except child’s race and ethnicity due to collinearity with parents’ race and ethnicity and included survey weights.

Categories are not presented in the table because the weighted estimates yielded unstable SEs.

Child’s race and ethnicity excluded from adjusted models due to collinearity with parent’s race and ethnicity.

Non-Hispanic Other included participants who identified as American Indian/Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander, or “other.”

Parents identifying as transgender were grouped with male or female groups according to their identified gender.

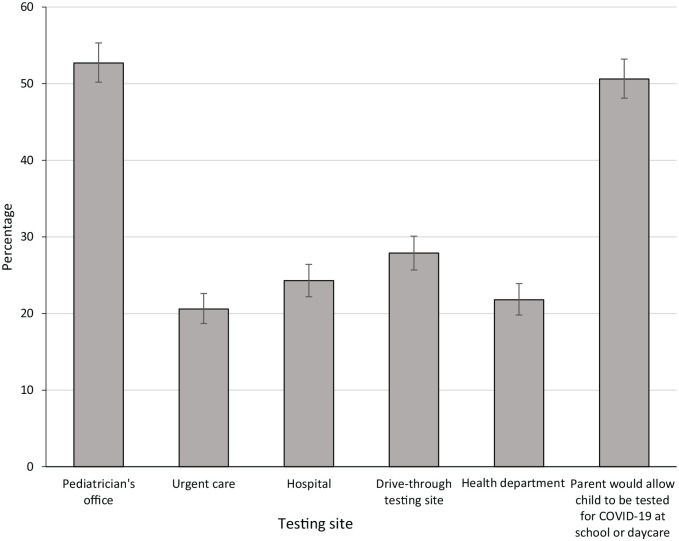

When asked to select venues where they would take their child for COVID-19 testing, 52.7% of all parents selected the pediatrician’s office, 27.9% drive-through testing sites, 24.3% hospitals, 21.8% health department testing sites, and 20.6% urgent care (Figure). A significantly higher percentage of parents of children aged <2 years preferred the pediatrician’s office for testing than parents of children aged 7-12 years (67.1% vs 42.0%; P < .001). Parents of younger children (aged <2 y) were less likely than parents of older children (aged 7-12 y) to report that they would take their child to an urgent care clinic (15.5% vs 24.5%; P = .003) or a health department testing site (15.1% vs 25.7%; P = .001) for testing (Table 2).

Figure.

Preferred SARS-CoV-2 testing venues for children aged ≤12 years as reported in a parental survey, United States, March 2021 (N = 2074). Error bars show 95% CIs for prevalence estimates.

Table 2.

Preferred SARS-CoV-2 testing venues for US children aged ≤12 years as reported by parents, United States, March 2021 a

| Characteristic | Testing venue preference, %

b

|

Parent would allow child to be tested for COVID-19 at school or daycare, % c | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pediatrician’s office | Urgent care | Hospital | Drive-through testing site | Health department testing site | ||

| Child | ||||||

| Age, y | ||||||

| <2 | 67.1 | 15.5 | 21.5 | 21.5 | 15.1 | 38.1 |

| 2-6 | 57.0 | 19.0 | 22.3 | 28.9 | 21.0 | 46.3 |

| 7-12 | 42.0 | 24.5 | 27.5 | 29.9 | 25.7 | 60.5 |

| P value d | <.001 | .003 | .05 | .02 | .001 | <.001 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 54.5 | 21.5 | 22.5 | 26.8 | 21.3 | 50.8 |

| Male | 51.2 | 19.9 | 26.2 | 28.8 | 22.4 | 50.5 |

| P value d | .20 | .43 | .09 | .37 | .60 | .90 |

| Race and ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 49.4 | 20.4 | 27.7 | 26.4 | 25.3 | 54.9 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 54.1 | 23.0 | 21.9 | 28.4 | 17.9 | 42.8 |

| Asian | 57.1 | 21.1 | 19.1 | 37.5 | 21.2 | 56.5 |

| Hispanic | 56.1 | 19.4 | 20.0 | 29.4 | 20.3 | 49.9 |

| Non-Hispanic Other e | 58.0 | 22.2 | 22.5 | 27.7 | 11.8 | 35.8 |

| P value d | .11 | .86 | .02 | .40 | .002 | .01 |

| Has health insurance | ||||||

| Yes | 54.2 | 20.7 | 24.3 | 29.1 | 22.1 | 51.7 |

| No | 34.4 | 20.2 | 25.3 | 14.0 | 20.1 | 40.0 |

| P value d | .001 | .91 | .80 | <.001 | .61 | .09 |

| Attending in-person school/daycare ≥1 day per week | ||||||

| Yes | 48.0 | 22.0 | 26.6 | 30.1 | 25.2 | 61.2 |

| No | 57.6 | 19.2 | 21.9 | 25.9 | 18.4 | 40.2 |

| P value d | <.001 | .17 | .03 | .06 | .001 | <.001 |

| Parent | ||||||

| Age, y | ||||||

| 18-29 | 56.1 | 19.2 | 21.5 | 28.2 | 19.2 | 38.8 |

| 30-44 | 52.4 | 21.1 | 26.1 | 27.1 | 22.4 | 52.6 |

| ≥45 | 49.2 | 20.2 | 20.0 | 31.2 | 23.2 | 58.2 |

| P value d | .30 | .73 | .05 | .46 | .42 | <.001 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 58.1 | 21.6 | 17.8 | 29.5 | 16.3 | 43.2 |

| Male | 44.9 | 18.5 | 33.7 | 25.8 | 30.4 | 62.3 |

| P value d | <.001 | .13 | <.001 | .10 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Race and ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 51.4 | 20.0 | 26.8 | 26.4 | 24.7 | 54.5 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 55.5 | 26.6 | 23.8 | 26.1 | 17.7 | 41.5 |

| Asian | 62.0 | 19.2 | 18.1 | 33.7 | 21.7 | 53.7 |

| Hispanic | 53.8 | 19.2 | 19.9 | 30.4 | 18.5 | 50.2 |

| Non-Hispanic Other e | 47.0 | 22.4 | 25.9 | 29.9 | 17.9 | 30.7 |

| P value d | .30 | .27 | .06 | .40 | .10 | .001 |

| Education (highest level completed) | ||||||

| ≤High school | 54.2 | 16.9 | 20.9 | 21.5 | 15.9 | 43.0 |

| Some college | 54.9 | 22.0 | 21.4 | 29.5 | 18.5 | 46.2 |

| ≥Completed college | 50.0 | 22.6 | 28.5 | 32.1 | 28.7 | 60.5 |

| P value d | .25 | .05 | .01 | .001 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Household | ||||||

| No. of children aged ≤12 y | ||||||

| 1 | 51.0 | 21.2 | 25.0 | 27.7 | 21.1 | 51.8 |

| 2 | 52.2 | 18.0 | 24.4 | 29.6 | 23.3 | 53.1 |

| ≥3 | 59.9 | 24.7 | 21.3 | 24.7 | 20.9 | 40.3 |

| P value d | .08 | .10 | .52 | .39 | .65 | .01 |

| Annual household income, $ | ||||||

| <25 000 | 53.5 | 14.7 | 18.9 | 22.1 | 14.0 | 43.9 |

| 25 000-49 999 | 58.2 | 22.0 | 21.5 | 27.0 | 17.5 | 41.6 |

| 50 000-99 999 | 51.2 | 24.3 | 23.2 | 33.2 | 23.7 | 52.3 |

| ≥100 000 | 47.8 | 22.0 | 34.1 | 28.7 | 32.5 | 68.3 |

| P value d | .04 | .01 | <.001 | .01 | <.001 | <.001 |

| US region | ||||||

| Northeast | 56.1 | 20.1 | 21.9 | 21.4 | 18.8 | 52.5 |

| South | 54.1 | 21.6 | 22.9 | 26.8 | 20.4 | 48.3 |

| Midwest | 48.9 | 20.6 | 28.3 | 30.6 | 22.7 | 47.6 |

| West | 51.6 | 19.8 | 24.7 | 31.6 | 25.3 | 55.7 |

| P value d | .28 | .87 | .19 | .01 | .14 | .29 |

Data reported by parents through online survey.

Weighted percentages are estimates of US parents reporting SARS-CoV-2 testing venue preferences.

This question was asked separately and was not a response option with other testing venues.

P values from Rao–Scott adjusted Pearson χ2 tests comparing levels of categories shown for each variable. P < .05 was considered significant.

Non-Hispanic Other included participants who identified as American Indian/Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander, or “other.”

Overall, 50.6% of parents said they would allow their youngest child to be tested for COVID-19 at school/daycare if required (Figure), 33.5% said they would not allow school-based testing, and 14.4% said they did not know (1.5% did not answer) (Table 2). In unadjusted analyses, parents of children aged 7-12 years, parents whose children had health insurance, and parents who had children attending school or daycare at the time of the survey were more likely to say they would allow testing in these venues. Parents who were non-Hispanic Black, were aged 18-24 years, had ≥3 children in the home, had not completed college, and had annual household income <$50 000 were significantly less likely to report that they would allow their child to be tested for COVID-19 in school or daycare settings.

Discussion

During the first 12 months of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, testing among children was low. In our study, only 36% of parents reported a child aged ≤12 years had ever been tested for SARS-CoV-2. Female and Asian parents were less likely to report children having received COVID-19 testing than male parents and parents from other racial and ethnic groups. Children without health insurance were also less likely to have been tested, whereas those attending school were more likely to have been tested. The most preferred COVID-19 testing location was a pediatrician’s office, and only half of parents in our survey reported they would allow their child to be tested at school or daycare.

Given the low proportion of US children tested during the first year of the pandemic and the high seropositivity observed in New York City, 9 it is possible that US children have not received all the COVID-19 testing needed. A survey conducted in February 2021 among US adults found that 49% had ever been tested for SARS-CoV-2 14 compared with 36% of children in our survey. The disparity between testing uptake among children and testing uptake among adults has not been widely reported and requires further examination.

In addition, our study found that children without health insurance were less likely to have received COVID-19 testing and children living in households with high incomes were more likely to have received testing. Few studies have examined access and barriers to COVID-19 testing among children, but data on adults and at the population level suggest that racial and ethnic minority groups, people with low incomes, people living in rural areas, and non-English speakers have been less likely to be tested for COVID-19 despite many of these groups having high infection rates.15-18 To address the testing gap in children, future research should examine barriers to COVID-19 testing in pediatric populations.

Although the US Food and Drug Administration granted emergency use authorization for the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine for children aged 5-11 years in October 2021, 19 evidence suggests that initial vaccination uptake for this age group may be low.20,21 With rising infections in the United States (starting in July 2021), efforts to maximize uptake of COVID-19 testing in pediatric populations should be a priority. In addition, the return to school for children in the United States in fall 2021 increased the need for testing. Although limited evidence is available on strategies to improve testing coverage among children, our data provide insights into how testing may be effectively expanded.

In our survey, lack of health insurance and low annual household income were associated with less testing in children, underscoring the importance of increasing access to free pediatric COVID-19 testing in the United States, including at pediatricians’ offices. Efforts should also be made to increase parental awareness of no-fee testing venues through social media and advertising campaigns. Although school attendance was associated with more reported COVID-19 testing among children, only half of the parents in our survey indicated that they would allow their child to be tested at school. Efforts are needed to identify reasons for parental hesitancy toward school- and daycare-based testing, because testing in these venues may be critical for ensuring the safety of children, teachers, and staff members. It will also be important to ensure access to testing services for children who are not attending school in person.

Parents’ preferred venue for pediatric COVID-19 testing was a pediatrician’s office. However, if the numbers of COVID-19 cases continue to rise, strategies may be needed to ensure that pediatric practices can safely offer testing to meet demand, including drive-through testing or designated practice hours for testing. Finally, an important testing implementation strategy may involve the ability of health care providers, laboratories, and parents to authorize and easily provide and disclose certified proof of test results for children (eg, via a national app) to entities (eg, schools), thus allowing flexibility and the ability for parents to choose a preferred testing provider and venue that meets basic standards for COVID-19 testing.

Limitations

Our study had several limitations. For one, our survey focused on children aged ≤12 years to collect information about younger children and did not provide information about adolescents. In addition, survey data were self-reported and, therefore, subject to recall, response, and social desirability bias. Another limitation was a lack of data on parental preferences for test type, specimen collection modality, or test result documentation, which could also contribute to efforts to expand testing access and uptake. In addition, we did not verify testing using medical record data. The survey was weighted to reflect the US population of parents based on 2019 US Census estimates. However, it was conducted online; therefore, it excluded parents who did not have access to the internet and may not reflect the full population of parents and caregivers of children. Finally, our study was conducted before the emergence of the Delta variant, which has contributed to an increase in COVID-19 cases among children and may have led to increased testing rates among pediatric populations.

Conclusion

In light of the current increase in pediatric cases of COVID-19, and in anticipation of initially low vaccination coverage among children, testing will remain critical for identifying pediatric infections and as a public health intervention to contain the epidemic. As such, our data can inform strategies to increase testing coverage and acceptability among US children.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was funded by the CUNY Institute for Implementation Science in Population Health.

ORCID iD: Chloe A. Teasdale, PhD  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9165-8972

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9165-8972

References

- 1. American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and Children’s Hospital Association. Children and COVID-19: state-level data report. Accessed September 26, 2021. https://services.aap.org/en/pages/2019-novel-coronavirus-covid-19-infections/children-and-covid-19-state-level-data-report

- 2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID data tracker: COVID-19 integrated country view. Accessed October 3, 2021. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#county-view

- 3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Delta variant: what we know about the science. 2021. Accessed August 9, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/variants/delta-variant.html

- 4. Felsenstein S, Hedrich CM. SARS-CoV-2 infections in children and young people. Clin Immunol. 2020;220:108588. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2020.108588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Buonsenso D, Munblit D, De Rose C, et al. Preliminary evidence on long COVID in children. Acta Paediatr. 2021;110(7):2208-2211. doi: 10.1111/apa.15870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lewis D. Long COVID and kids: scientists race to find answers. Nature. 2021;595(7868):482-483. doi: 10.1038/d41586-021-01935-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Leidman E, Duca LM, Omura JD, Proia K, Stephens JW, Sauber-Schatz EK. COVID-19 trends among persons aged 0-24 years—United States, March 1–December 12, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(3):88-94. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7003e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sisk B, Cull W, Harris JM, Rothenburger A, Olson L. National trends of cases of COVID-19 in children based on US state health department data. Pediatrics. 2020;146(6):e2020027425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rane MS, Profeta A, Poehlein E, et al. The emergence, surge and subsequent wave of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in New York metropolitan area: the view from a major region-wide urgent care provider. Preprint. Posted online April 12, 2021. medRxiv. doi: 10.1101/2021.04.06.21255009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mehta NS, Mytton OT, Mullins EWS, et al. SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19): what do we know about children? A systematic review. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(9):2469-2479. doi: 10.1039.cic/ciaa556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Miller CA, Guidry JPD, Dahman B, Thomson MD. A tale of two diverse Qualtrics samples: information for online survey researchers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2020;29(4):731-735. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-19-0846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. American Association for Public Opinion Research. Standard definitions: final dispositions of case codes and outcome rates for surveys. Revised 2016. Accessed January 13, 2021. https://www.aapor.org/AAPOR_Main/media/publications/Standard-Definitions20169theditionfinal.pdf

- 13. US Census Bureau. QuickFacts: population estimates July 1, 2019. Accessed January 5, 2021. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045219

- 14. Silverman E. STAT-Harris Poll: 1 in 4 Americans were unable to get a COVID-19 test when they wanted one. STAT+. February 15, 2021. Accessed August 9, 2021. https://www.statnews.com/pharmalot/2021/02/15/stat-harris-poll-1-in-4-americans-unable-to-get-covid19-test

- 15. Kim HN, Lan KF, Nkyekyer E, et al. Assessment of disparities in COVID-19 testing and infection across language groups in Seattle, Washington. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9):e2021213. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.21213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Souch JM, Cossman JS. A commentary on rural–urban disparities in COVID-19 testing rates per 100,000 and risk factors. J Rural Health. 2021;37(1):188-190. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lieberman-Cribbin W, Tuminello S, Flores RM, Taioli E. Disparities in COVID-19 testing and positivity in New York City. Am J Prev Med. 2020;59(3):326-332. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2020.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dryden-Peterson S, Velásquez GE, Stopka TJ, Davey S, Lockman S, Ojikutu BO. Disparities in SARS-CoV-2 testing in Massachusetts during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(2):e2037067. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.37067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC recommends pediatric COVID-19 vaccine for children 5 to 11 years. November 2, 2021. Accessed November 2, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2021/s1102-PediatricCOVID-19Vaccine.html

- 20. Teasdale CA, Borrell LN, Shen Y, et al. Parental plans to vaccinate children for COVID-19 in New York City. Vaccine. 2021;39(36):5082-5086. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.07.058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Teasdale CA, Borrell LN, Kimball S, et al. Plans to vaccinate children for coronavirus disease 2019: a survey of United States parents. J Pediatr. 2021;237:292-297. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2021.07.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]