Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has disproportionately affected tribal populations, including the San Carlos Apache Tribe. Universal screening testing in a community using rapid antigen tests could allow for near–real-time identification of COVID-19 cases and result in reduced SARS-CoV-2 transmission. Published experiences of such testing strategies in tribal communities are lacking. Accordingly, tribal partners, with support from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, implemented a serial testing program using the Abbott BinaxNOW rapid antigen test in 2 tribal casinos and 1 detention center on the San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation for a 4-week pilot period from January to February 2021. Staff members at each setting, and incarcerated adults at the detention center, were tested every 3 or 4 days with BinaxNOW. During the 4-week period, 3834 tests were performed among 716 participants at the sites. Lessons learned from implementing this program included demonstrating (1) the plausibility of screening testing programs in casino and prison settings, (2) the utility of training non–laboratory personnel in rapid testing protocols that allow task shifting and reduce the workload on public health employees and laboratory staff, (3) the importance of building and strengthening partnerships with representatives from the community and public and private sectors, and (4) the need to implement systems that ensure confidentiality of test results and promote compliance among participants. Our experience and the lessons learned demonstrate that a serial rapid antigen testing strategy may be useful in work settings during the COVID-19 pandemic as schools and businesses are open for service.

Keywords: American Indian/Alaska Native, correctional facilities/prisons, minority health, occupational health, prevention, workforce

COVID-19 has disproportionately affected the health of tribal populations.1-3 The San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation in southeastern Arizona is home to approximately 10 400 members of the San Carlos Apache Tribe (SCAT) and encompasses more than 1.8 million acres of land.4,5 As of October 18, 2021, a total of 4965 people with COVID-19 (477 cases per 1000 people) and 59 deaths (12 deaths per 1000 cases) from COVID-19 had been reported on this reservation. 6 Mitigating transmission in community settings is an effective way to reduce the impact of COVID-19 on the health of the tribe and other indigenous populations. Transmission of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, can occur in various work settings, institutions, and facilities, and can propagate COVID-19 outbreaks in a community. 7 Screening through serial testing in these settings could help identify and isolate people with asymptomatic and presymptomatic COVID-19, prevent and control outbreaks, and reduce SARS-CoV-2 transmission in a community.8-10 Published experiences documenting the implementation of COVID-19 screening programs in rural, tribal settings are lacking. Dissemination of these experiences and the lessons learned could inform the efforts of other communities in implementing such programs and mitigating the negative public health effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Purpose

The Department of Health and Human Services of the San Carlos Apache Tribe (SCAT DHHS), in collaboration with the San Carlos Apache Healthcare Corporation (SCAHC) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), developed a serial testing program using rapid antigen testing at multiple community settings on the San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation. Tribal partners, with support from CDC, implemented the serial testing program using the BinaxNOW rapid antigen test (Abbott Laboratories) on the reservation in 2 casinos, which together have more than 400 employees and 2500-3000 patrons monthly, and a detention center, which has nearly 40 staff members and a bed capacity of 108 incarcerated adults. We describe the findings and lessons learned from the implementation of this serial antigen testing program.

Methods

The 28-day serial testing program commenced at both casinos on January 27, 2021, and ended on February 23, 2021, and commenced at the detention center on February 4, 2021, and ended on March 3, 2021. The program aimed to test each staff member at the casinos and detention center and each incarcerated person at the detention center every 72-96 hours or, on average, 8 or 9 tests (approximately 2 tests per week) during the program period. Partners, including the CDC team deployed to assist SCAT, SCAT DHHS, and SCAHC, designed and oversaw implementation of the program protocol and processes. Staff members at the detention center and casinos, along with public health staff members from SCAT DHHS, were primarily responsible for daily implementation of the program, which emphasized testing participants and reporting positive test results to public health authorities and participants confidentially and efficiently (Figure 1). Because of the potential benefit of the program to the health of staff members, clients, and the tribal community, and the minimal risk to participants, we did not formally obtain consent from participants. We collected demographic data from administrative records; test results from daily testing logs, which included frequency data that were collected among employees of the casinos and detention center, but not among incarcerated people because of their high turnover rate; and relevant medical data, including history of COVID-19 diagnosis and history of COVID-19 vaccination, from SCAHC’s electronic health records system. CDC, SCAT DHHS, SCAHC, and other key partners from the detention center and casinos reviewed and approved the protocols before implementation. SCAT DHHS presented the project proposal to the San Carlos Apache Tribal Council and received their approval before implementation. We did not seek institutional review board approval. However, this activity was reviewed by CDC and was conducted consistent with applicable federal law and CDC policy (see, eg, 45 CFR part 46.102(l)(2); 21 CFR part 56; 42 USC §241(d); 5 USC §552a; 44 USC §3501 et seq.).

Figure 1.

Protocol for COVID-19 screening testing at 2 casinos and 1 detention center on the San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation, January–February 2021. Abbreviation: DHHS, Department of Health and Human Services.

All staff members and incarcerated people were eligible for BinaxNOW (Abbott Laboratories) testing; however, those who developed symptoms or had contact with someone who received a positive test result for COVID-19 within the previous 14 days would also require SARS-CoV-2 real-time polymerase chain reaction testing. For the BinaxNOW test, participants received a nasal swab, self-swabbed both anterior nares, and handed the swab to the tester. After handing the swab to the tester, the participant left the testing area, and the tester ran the sample. Participants were instructed to assume their test result was negative if they were not notified by the end of the business day and counseled that they likely did not have COVID-19 and did not require isolation.

In the casinos, a large conference room was designated as the testing area, with testers available daily. Staff members would come at the start of their shift or during breaks to be tested. In the detention center, testers would circulate through each pod or living quarters twice per week and test each incarcerated person in each pod. Once each incarcerated person was tested in the pod, the testers would move to the next pod. A classroom was designated twice per week in the detention center for staff member testing, and staff members would come to the classroom at the start of their shift to be tested. If a staff member could not leave a designated work area, testers would come to the staff member for testing.

Testers would log test results onto a data sheet and share results with administrative personnel at the end of the day. At the casinos, 1 human resources staff member was designated as the administrative personnel; at the detention center, 1 captain was designated as the administrative personnel. Personnel would log testing results onto a master data file that was shared regularly with San Carlos Apache Department of Health and Human Services (San Carlos DHHS).

Outcomes

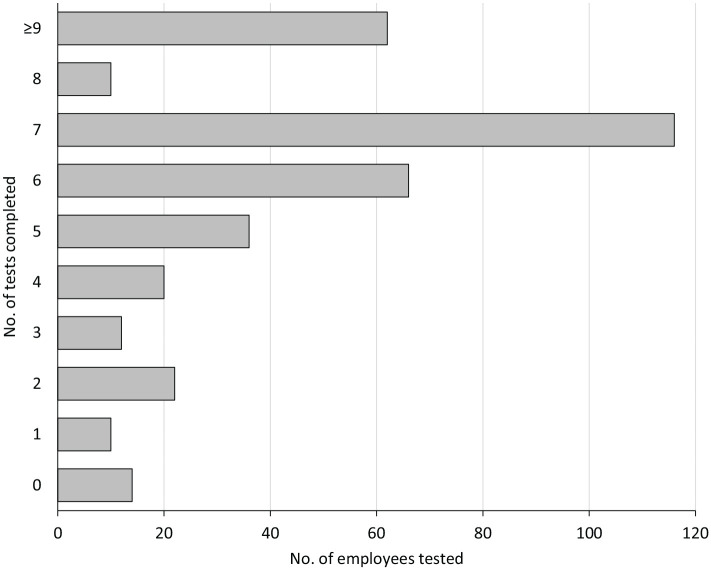

During the testing period, casino and detention center testers administered a total of 3834 tests among 716 people. Testers at the casinos administered 2764 tests among 409 of 421 (97%) staff members, resulting in 6.6 tests (range, 0-11) per employee. Testers at the detention center administered 1070 tests among 272 of 274 (99%) incarcerated people, resulting in 3.3 tests (range, 0-9) per incarcerated person and 35 of 37 (95%) staff members, resulting in 4.1 tests (range, 0-9) per employee. Among all employee participants (n = 458), 162 (35%) received ≥8 tests during the 4-week period, 218 (48%) received 5-7 tests, 78 (17%) received ≤4 tests, and 14 (3%) received no tests (Figure 2). Of the 716 people who were tested, 263 (37%) had a history of previous COVID-19 diagnosis, 177 (25%) had received ≥1 dose of the COVID-19 vaccine at the start of the testing program, and 307 (43%) had either had a previous COVID-19 diagnosis or ≥1 dose of the vaccine. Of the 177 people who had received ≥1 dose of the COVID-19 vaccine at initiation of testing, 77 (44%) had also received a second vaccine dose before initiation. Among all people tested, only 1 person, an employee at the casino living off the reservation, had a positive COVID-19 test result, and this employee had no close contacts within the casino.

Figure 2.

Testing compliance among staff participants in a COVID-19 screening and testing pilot program at 2 casinos and 1 detention center on the San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation, January–February 2021.

Lessons Learned

During the project period, only 1 person received a positive COVID-19 test result of the 3834 tests administered and 716 people tested. Several factors may have reduced the COVID-19 incidence and SARS-CoV-2 transmission in these settings during the testing period. First, community COVID-19 incidence substantially decreased during the program period; weekly COVID-19 incidence steadily dropped from 55 cases (328 per 100 000 people) during January 24-30, 2021, to 3 cases (18 per 100 000 people) during February 21-27, 2021. Second, substantial levels of possible immunity to COVID-19 were evident among participants, because 43% of participants had had a previous COVID-19 diagnosis or had received ≥1 vaccine dose at the start of testing. Third, existing community mitigation measures, target testing protocols, and infection control and prevention measures, which were adapted from CDC recommendations and guidance,11,12 had already been implemented in these community settings. These measures may have prevented transmission from the community into these workplaces. For example, in the detention center, in addition to enforcement of face mask wearing, physical distancing, and hand hygiene, staff members tested each incarcerated person by either SARS-CoV-2 reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction or a rapid antigen test at booking. Staff members isolated incarcerated people with positive test results from other incarcerated people to prevent transmission within the detention center. People identified as being in close contact with the person who received a positive COVID-19 test result were also quarantined until retesting per SCAHC testing protocols. Lastly, besides low COVID-19 incidence, limitations of the screening program may have led to reduced sensitivity of the program to identify COVID-19 cases and an underestimation of cases. Such limitations include variable compliance rates among participants and moderate sensitivity of the BinaxNOW test, particularly among asymptomatic people.13,14

Several lessons were learned while implementing this community-wide testing program, First, laboratory personnel from SCAHC trained and certified non–health care personnel staff members from the casinos and detention center to be testers. Using testers without previous health care experience was possible because of the ease of collecting specimens and the simple methodology of conducting, and reading results from, the rapid antigen test. No invalid tests were documented during the study period, demonstrating that the trained non–health care staff members were competent in administering the rapid tests. Furthermore, previous studies have demonstrated high interoperator agreement between testers and readers.15,16 Because of this approach, SCAT DHHS laboratory staff member time was preserved to continue routine COVID-19 testing and their other responsibilities. In addition, because SCAT DHHS staff members did not have to administer tests, they could focus on their other responsibilities related to the COVID-19 response, including surveillance, case investigation and isolation, contact tracing, quarantining close contacts, and administering reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction testing of contacts.

Second, obtaining buy-in from various partners in criminal justice, the gaming industry, and tribal leadership was a critical step in implementing this serial testing program. Before implementing the program, representatives from CDC and SCAT DHHS met with leadership from the tribal council and government, detention center, and casinos. They discussed the purpose of the testing program, how it would be implemented, and the resources required, particularly from the relevant organizations. The tribal council approved the program, and leadership from the detention center and casinos enthusiastically agreed to host these programs. Without this initial approval, the tribal partners would not have been able to implement the program. Because of the testing program, San Carlos public health and health care leaders have been able to strengthen partnerships with community representatives that will help improve the safety of the tribe.

Third, SCAHC and SCAT DHHS had to establish procedures to ensure privacy and confidentiality of test results. For example, implementing partners created and used anonymized employee identification numbers to collect information on test results. Furthermore, partners instructed administrative personnel and testers not to share results with participants immediately after testing was conducted. This delay prevented crowding of the testing area (participants were instructed to go to their workstation or pod after giving a sample to the tester) and to ensure privacy and prevent other participants or staff members in the immediate area from overhearing test results. Rather, after a positive test result was reported to SCAT DHHS, the public health authorities would notify the participant. When deciding whether administrative personnel or public health authorities should directly inform participants of their results, partners weighed the risks of crowding and breaching confidentiality with the risk of potentially permitting further SARS-CoV-2 transmission if a person was not notified immediately of a positive test result. Because only 1 person was identified, these concerns did not have a substantial impact on program implementation; however, future implementers would need to consider these risks in the scenario when multiple people received a positive test result.

Fourth, ensuring compliance among participants, particularly staff members, to complete all required testing was challenging. Potential reasons for suboptimal compliance included staff members being on leave or off duty when testing occurred or being unable or unwilling to leave their workstation to be tested. At least 1 incarcerated person was not tested because of concerns about safety to himself or others if he participated. Adaptations to the protocol improved compliance. For example, in the detention center, testers would migrate to an employee’s individual workstation if the employee was unable to leave the station. In the casinos, because of the large number of staff members, testers could not migrate to employees’ individual workstations. However, testers worked with the human resources department and supervisors to facilitate participation among staff members. Another example included adaptations to ensure both daytime and nighttime staff members were tested. In the casinos, the testing area was available to employees from the early morning until the evening to ensure those working the night shift could get tested at change of shift. In the detention center, testers would conduct testing at change of shift in the morning or evening to ensure night shift staff members could be tested. Lastly, promoting compliance to protect the health of the community had to be weighed against ensuring the autonomy of participants. Some participants refused or avoided testing; however, we acknowledge that employees and incarcerated people may not have complete self-efficacy and autonomy.

Through the development and implementation of this serial testing program, community and public health partners worked together to administer 3834 tests among 716 participants in 3 tribal community settings confidentially, efficiently, and effectively. After completion of the pilot program, serial rapid antigen testing continued at the casinos and the detention center. SCAT DHHS is using the experience from this program to implement serial testing strategies in tribal schools and tribal government workplaces as they reopen.

In conclusion, our experience in implementing a serial testing program in 3 work settings in a tribal nation may encourage other communities to consider implementing similar programs as businesses, workplaces, and schools continue to fully reopen. Communities interested in implementing such testing programs will need to create and strengthen partnerships with key members of the community and implement mechanisms to ensure confidentiality and promote participant compliance. Such communities should also consider using CDC’s antigen test algorithm for community settings in their protocols to help determine disposition after a test result, particularly if and when a rapid antigen test result requires confirmatory PCR testing. 17 Along with intensive infection prevention and control measures, adherence to community mitigation measures, and widespread vaccination, implementation of a screening testing program can be beneficial to help communities mitigate the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the following people and organizations for their assistance in designing and implementing this screening testing program: San Carlos Apache Tribal Council; San Carlos Apache Healthcare Corporation Board of Directors; Nam Le-Morawa (interim chief operations officer, San Carlos Apache Healthcare Corporation); Myron Moses (executive director, San Carlos Apache Juvenile and Adult Rehabilitation and Detention Center); Antoinette Henry (captain and juvenile manager, San Carlos Apache Juvenile and Adult Rehabilitation and Detention Center); participating staff members and incarcerated people from San Carlos Apache Juvenile and Adult Rehabilitation and Detention Center; Matt Olin (chief executive officer, San Carlos Apache Gold Casino and Resort and Apache Sky Casino); Lee Randall (general manager, Apache Sky Casino); Linda Michaels (general manager, Apache Gold Casino and Resort); participating staff members from San Carlos Apache Gold Casino and Resort and Apache Sky Casino; Aaron Tohtsoni (communication officer, San Carlos Apache Tribe Department of Health and Human Services); and Anniece Minor (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] communications officer).

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of CDC. Use of trade names and commercial sources is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by the US Department of Health and Human Services or CDC.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Nickolas T. Agathis, MD, MPH  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2641-4888

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2641-4888

References

- 1. Arrazola J, Massiello MM, Joshi S, et al. COVID-19 mortality among American Indian and Alaska Native persons—14 states, January–June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(49):1853-1856. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6949a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hatcher SM, Agnew-Brune C, Anderson M, et al. COVID-19 among American Indian and Alaska Native persons—23 states, January 31–July 3, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(34):1166-1169. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6934e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Williamson LL, Harwell TS, Koch TM, et al. COVID-19 incidence and mortality among American Indian/Alaska Native and White persons—Montana, March 13–November 30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(14):510-513. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7014a2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Inter Tribal Council of Arizona. San Carlos Apache Tribe introductory information. 2021. Accessed October 18, 2021. https://itcaonline.com/member-tribes/san-carlos-apache-tribe

- 5. The University of Arizona Native American Advancement, Initiatives, and Research. San Carlos Apache Tribe community profile. 2021. Accessed October 6, 2021. https://naair.arizona.edu/san-carlos-apache-indian-tribe

- 6. San Carlos Apache Healthcare Corporation. COVID-19 information: SCAHC COVID-19 update. March 3-4, 2021. Accessed October 18, 2021. https://www.scahealth.org/covid-19-information-2

- 7. Pray IW, Kocharian A, Mason J, Westergaard R, Meiman J. Trends in outbreak-associated cases of COVID-19—Wisconsin, March–November 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(4):114-117. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7004a2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pray IW, Ford L, Cole D, et al. Performance of an antigen-based test for asymptomatic and symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 testing at two university campuses—Wisconsin, September–October 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;69(5152):1642-1647. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm695152a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wadhwa A, Fisher KA, Silver R, et al. Identification of pre-symptomatic and asymptomatic cases using cohort-based testing approaches at a large correctional facility—Chicago, Illinois, USA, May 2020. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72(5):e128-e135. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wallace M, James AE, Silver R, et al. Rapid transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in detention facility, Louisiana, USA, May–June, 2020. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27(2):421-429. doi: 10.3201/eid2702.204158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19: considerations for casinos and gaming operations. Updated April 19, 2021. Accessed March 4, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/organizations/business-employers/casinos-gaming-operations.html

- 12. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19: interim guidance on management of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in correctional and detention facilities. Updated June 9, 2021. Accessed March 4, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/correction-detention/guidance-correctional-detention.html

- 13. Okoye NC, Barker AP, Curtis K, et al. Performance characteristics of BinaxNOW COVID-19 antigen card for screening asymptomatic individuals in a university setting. J Clin Microbiol. 2021;59(4):e03282-20. doi: 10.1128/jcm.03282-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Prince-Guerra JL, Almendares O, Nolen LD, et al. Evaluation of Abbott BinaxNOW rapid antigen test for SARS-CoV-2 infection at two community-based testing sites—Pima County, Arizona, November 3-17, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(3):100-105. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7003e3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pollock NR, Jacobs JR, Tran K, et al. Performance and implementation evaluation of the Abbott BinaxNOW rapid antigen test in a high-throughput drive-through community testing site in Massachusetts. J Clin Microbiol. 2021;59(5):e00083-21. doi: 10.1128/jcm.00083-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shah MM, Salvatore PP, Ford L, et al. Performance of repeat BinaxNOW severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 antigen testing in a community setting, Wisconsin, November–December 2020. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(Suppl 1):S54-S57. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim guidance for antigen testing for SARS-CoV-2. Updated September 9, 2021. Accessed August 22, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/lab/resources/antigen-tests-guidelines.html#using-antigen-tests-community-settings