Abstract

The public health crisis created by the COVID-19 pandemic has spurred a deluge of scientific research aimed at informing the public health and medical response to the pandemic. However, early in the pandemic, those working in frontline public health and clinical care had insufficient time to parse the rapidly evolving evidence and use it for decision-making. Academics in public health and medicine were well-placed to translate the evidence for use by frontline clinicians and public health practitioners. The Novel Coronavirus Research Compendium (NCRC), a group of >60 faculty and trainees across the United States, formed in March 2020 with the goal to quickly triage and review the large volume of preprints and peer-reviewed publications on SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 and summarize the most important, novel evidence to inform pandemic response. From April 6 through December 31, 2020, NCRC teams screened 54 192 peer-reviewed articles and preprints, of which 527 were selected for review and uploaded to the NCRC website for public consumption. Most articles were peer-reviewed publications (n = 395, 75.0%), published in 102 journals; 25.1% (n = 132) of articles reviewed were preprints. The NCRC is a successful model of how academics translate scientific knowledge for practitioners and help build capacity for this work among students. This approach could be used for health problems beyond COVID-19, but the effort is resource intensive and may not be sustainable in the long term.

Keywords: COVID-19, epidemiology, vaccines, clinical care

The public health crisis created by the COVID-19 pandemic has spurred an unprecedented response from the public health and scientific community to generate evidence about transmission, clinical presentation, pathogenesis, and best practices for prevention and mitigation. From January 30 through April 23, 2020, an average of 367 articles about SARS-CoV-2 or COVID-19 were published weekly, with a median submission-to-publication time of 6 days. 1 In comparison, when the World Health Organization declared Ebola as an international emergency in 2019, only 4 articles were published weekly, with a median submission-to-publication time of 15 days. 1 More than 100 000 articles were published on SARS-CoV-2 from December 1, 2019, through December 31, 2020, 2 more than all articles ever published for infectious diseases such as measles (~53 000) or Lyme disease (~24 000) (search conducted by K. Lobner, October 30, 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic has necessitated such urgent sharing of scientific evidence that many authors have increasingly turned to preprints to share results quickly despite the acceleration in publication speed. 3 Preprints are manuscripts made publicly available through online repositories such as bioRxiv and medRxiv, prior to peer review, to share research findings more quickly than is possible through peer-reviewed publication in a journal. Although preprints provide access to study results more quickly, their findings can be more difficult to parse and act on than study results from published articles that have had the benefit of additional editing and peer review.

The large volume of new evidence about SARS-CoV-2 was produced with the aim of improving the collective medical and public health response; however, this aspiration can only be realized if, at a minimum, practitioners and policy makers see the best evidence at the right time. Early in the pandemic, 2 barriers to optimal use of emerging evidence became clear. First, clinicians and public health practitioners on the frontlines of the pandemic response did not have the time to keep up with the rapid pace of new knowledge generation. Their time and effort were completely consumed with patient care and ramping up public health responses. Second, given the diverse research disciplines represented in the emerging literature, few public health or medical professionals are likely to have the required technical expertise to appropriately evaluate the evidence across broad topic areas and to determine its relevance to clinical or public health practice. It can be even more difficult to assess the strengths and weaknesses of evidence presented in preprints compared with published articles because, by definition, they are often less developed than published articles.

Academics in public health and medicine are well-placed to facilitate the use of this evidence by frontline clinicians and public health practitioners. They routinely review and critique the scientific literature and collectively have the technical training to assess strengths and weaknesses of studies across a wide variety of scientific fields.

The Novel Coronavirus Research Compendium (NCRC) 4 formed in March 2020 with the goal to quickly triage and review the large volume of preprints and peer-reviewed publications on SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 and to summarize the most important, novel evidence to inform health departments, clinicians, and policy makers responsible for pandemic response. Here, we present our process and experiences with this initiative to provide a case study in knowledge translation for pandemic response and to serve as a reference for other academic or public health groups considering similar evidence curation efforts for other diseases.

Methods

Composition and Expertise of Teams

The NCRC comprises 8 teams focused on clinical presentation of COVID-19, diagnostics, ecology and spillover, epidemiology, disease modeling, nonpharmaceutical interventions, pharmaceutical interventions, and vaccines. Each topic is led by faculty with expertise in that area, supported by other faculty, doctoral trainees, postdoctoral fellows, or medical students. The NCRC is led by a team at Johns Hopkins University and includes >60 people from various institutions.

Identifying and Selecting Preprints and Articles for Review

Based on their knowledge of the most important articles published and preprints available through March 30, 2020, faculty experts on the team identified the first articles reviewed by the NCRC (n = 54) from each NCRC topic area. From that date forward, preprint and article searches were automated. An informationist coordinated with each team to develop 8 search queries—1 per research area—to identify articles on COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-2. For PubMed, queries were invoked using R (R Core Team) with the easyPubMed R package version 2.13 (Fantini) and reformatted from XML using the rvest package version 1.01 (Wickham) to extract relevant information. Preprints from bioRxiv and medRxiv were obtained from their “COVID-19 SARS-CoV-2 preprints” curated collection 5 using their application programming interface (API) in the JSON format using R and the jsonlite package version 1.72 (Ooms, Lang, Hilaiel). Preprints from SSRN were obtained as daily XML files through the Elsevier Developers API and were processed as previously described. All preprints were assigned to each research area using predefined search queries. Articles that matched multiple research areas were assigned to the group with the fewest articles.

Metadata about articles returned by this process were appended to a Google Sheets spreadsheet that served as the back-end database for an R Shiny web application, which we developed to be the primary interface for NCRC teams to access and select the articles generated through the automated search results.

In the “triage” process, NCRC faculty members with expert knowledge in a given topic area selected articles for in-depth review that (1) contained original research (could include reviews) representing important contributions to our understanding of the pandemic that would be relevant to a practice-based public health audience and/or (2) were widely circulated in the public sphere. Studies were also sometimes identified by members through news reports or social media before the automated process; these studies were processed outside the R Shiny application.

Structure of the Reviews and Editing

NCRC members read articles selected for review and identified the study population and design; highlighted the major findings, study strengths, and limitations; and summarized the added value of the evidence considering what was already known. Each review also included a section called “Our Take,” which provides a capsule evaluation in about 150 words. Reviews were typically drafted by doctoral trainees and reviewed by faculty before being entered into the R Shiny application. These submitted reviews underwent a second round of faculty editing for clarity and consistency of communication. Final reviews were then automatically posted to the NCRC website directly from a Google Sheet, which automatically populates sections. Through a formal collaboration with bioRxiv and medRxiv, NCRC reviews of most preprints were also automatically posted onto the preprint’s bioRxiv or medRxiv page.

Communicating Reviews

The NCRC website launched on April 27, 2020. Reviews were organized across the 8 research areas (with the ability to cross-post to all relevant areas). A search function allows viewers to search for reviews based on words appearing anywhere in the review. On June 15, 2020, each review began to include the date it was published to the NCRC website. Two reviews were of articles eventually retracted because of lack of data reproducibility. For these articles, the phrase “This article has been retracted due to concerns over data veracity” replaced our reviews on the website.

On July 2, 2020, the team launched an email newsletter in which subscribers received a weekly digest of all new reviews posted to the website. The team has also used Twitter (@JHSPH_NCRC) to highlight noteworthy articles and to post topical threads with an evidence summary and links to multiple related reviews. Popular hashtags (eg, #COVID19, #SARSCoV2, #coronavirus) are used to help people who are not yet following @JHSPH_NCRC to find these posts.

Outcomes

From April 6, through December 31, 2020, a total of 54 192 articles and preprints were uploaded into the R Shiny application for teams to triage and review. The number of articles and preprints uploaded to the R Shiny application increased through August and decreased in subsequent months (Table). Most articles and preprints uploaded to Shiny were articles in peer-reviewed journals (n = 41 072, 75.8%), and 13 120 (24.2%) were from preprint archives (bioRxiv, medRxiv, SSRN, and Research Square).

Table.

Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2–related articles and preprints triaged through the R Shiny application and reviewed and posted to the Novel Coronavirus Research Compendium (NCRC) website from April 6 through December 31, 2020

| Characteristic | Shiny (N = 54 192) | NCRC website (N = 527) |

|---|---|---|

| Article type | ||

| Preprint (not peer reviewed) | 13 120 (24.2) | 132 (25.0) |

| Publication (peer reviewed) | 41 072 (75.8) | 395 (75.0) |

| Team | ||

| Clinical | 6392 (11.8) | 132 (25.0) |

| Diagnostics | 7431 (13.7) | 20 (3.8) |

| Ecology | 2217 (4.1) | 28 (5.3) |

| Epidemiology | 9311 (17.2) | 168 (31.9) |

| Modeling | 8116 (15.0) | 38 (7.2) |

| Nonpharmaceutical interventions | 9003 (16.6) | 87 (16.5) |

| Pharmaceutical interventions | 6681 (12.3) | 22 (4.2) |

| Vaccines | 5041 (9.3) | 32 (6.1) |

| Publication/post month a | ||

| Before April | 2543 (4.7) | Not applicable |

| April | 4185 (7.7) | 43 (8.2) |

| May | 5395 (10.0) | 111 (21.1) |

| June | 5373 (9.9) | 66 (12.5) |

| July | 6672 (12.3) | 73 (13.9) |

| August | 8371 (15.4) | 55 (10.4) |

| September | 5812 (10.7) | 43 (8.2) |

| October | 5551 (10.2) | 55 (10.4) |

| November | 5403 (10.0) | 40 (7.6) |

| December | 4887 (9.0) | 41 (7.8) |

Publication month for articles was posted into the application, and month review was posted on the NCRC website for articles that were peer reviewed.

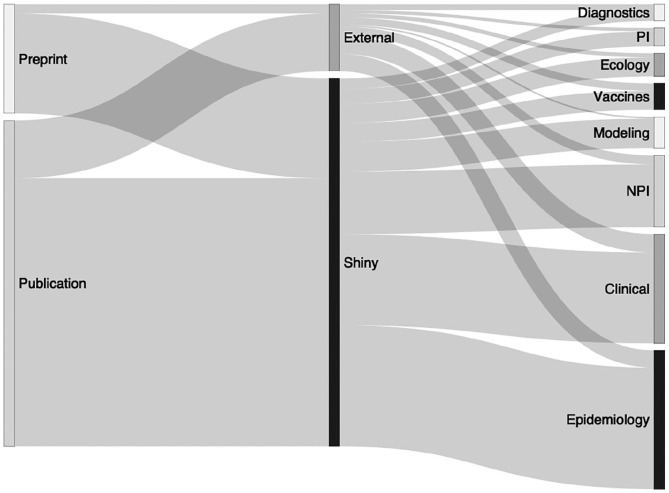

Teams posted 527 total reviews to the NCRC website as of January 1, 2021, of which 395 (75.0%) were of peer-reviewed publications and 132 (25.0%) were of preprints (Table, Figure). Of 472 articles published after April 1, 2020, the median time from online publication to posting on the NCRC website was 30 days (interquartile range [IQR], 19-46 days), and this timing was largely consistent by month of review and article status (preprint vs article). Of 132 preprints reviewed, 73 (55.3%) were published in a peer-reviewed journal before January 27, 2021. The NCRC review of the preprint was posted to the NCRC website a median of 43 days (IQR, 14-93 days) before publication in a peer-reviewed journal.

Figure.

Sankey diagram of workflow for all reviews published to the Novel Coronavirus Research Compendium website, by source, article type, and primary review group, April 1–December 31, 2020 (N = 472). Preprints are manuscripts made publicly available before peer review. Articles are peer-reviewed and published in journals. Preprints and articles were identified for review either through the triage list in the R Shiny application or through identification through external sources, such as social media or news reports. Abbreviations: NPI, nonpharmaceutical intervention review group; PI, pharmaceutical intervention review group.

Articles reviewed by the NCRC (n = 395) were published in 102 journals. More than half (61.5%, 243/395) of the uploaded reviews of articles came from 7 journals or journal families: Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (n = 51, 12.9%), the Lancet family (n = 47, 11.9%), JAMA family (n = 36, 9.1%), Nature family (n = 31, 7.9%), New England Journal of Medicine (n = 30, 7.6%), Clinical Infectious Diseases (n = 26, 6.6%), and Emerging Infectious Diseases (n = 22, 5.6%).

Through December 31, 2020, the NCRC newsletter acquired 1018 subscribers, the Twitter account had 689 000 impressions, and the website received 112 615 views from 42 174 users, with traffic from 180 countries. More than 90% of traffic was from the United States, United Kingdom, and Canada; more than 1000 page views were from Spain, Brazil, Germany, and India. We were able to discern from the email addresses of newsletter subscribers that they included academics, government officials, hospital staff members, journalists, nonprofit or for-profit employees, and nonacademic research staff members. Visitors to the website most commonly visited the epidemiology (29.0% of page views), nonpharmaceutical intervention (27.0%), and clinical presentation and prognosis (16.0%) content.

The NCRC has been covered by media outlets, including Buzzfeed, Vox, and The New York Times, as well as scientific magazines such as Science. NCRC faculty have also appeared on the Public Health on Call podcast produced by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health to discuss recent reviews.

Lessons Learned

The NCRC is a large, coordinated, multidisciplinary effort of technical experts in public health science and clinical medicine dedicated to using their skills to support frontline clinicians and public health practitioners. One of the most important lessons we learned was that our successes required a large team with experience across disciplines. The urgency of the pandemic allowed us to motivate a singular, and often uncompensated, effort to quickly curate and evaluate emerging science. This team-based approach allowed the NCRC to not only code a complex content management system from scratch but also to cover a wide variety of topics, from transmission across settings, face mask–wearing behaviors, and the use of dogs for detecting SARS-CoV-2 to vaccine efficacy against SARS-CoV-2 variants.

In a fast-moving public health crisis, practitioners need the most important and up-to-date evidence quickly to make decisions about clinical care and public health programs. Preprints are an increasingly important pathway for communicating emerging evidence about COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-2. However, using data from preprints to make clinical and public health decisions has risks. Because they have not yet undergone peer review, preprints are often more difficult to parse and may contain flaws in their methodology or analyses that could fatally compromise the findings and conclusions. Given the increasing attention from the media on preprints and the urgency to quickly understand the novel coronavirus, the NCRC designed its system to routinely include preprints in the review process. The NCRC’s collaboration with bioRxiv and medRxiv ensures that reviews of preprints are seen by authors and others, such as journalists or the public, who might access them directly from the preprint server.

The NCRC’s team of experts aimed to quickly identify popular but flawed preprints and articles. Even after peer review, errors in analysis or overreach in the interpretation of data in research studies may be identified after publication. The extraordinary speed of publication during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic may have exacerbated the risk of these errors. Sometimes, errors can give rise to surprising results, and these findings can garner outsized attention because of the claims they make. On multiple occasions, the NCRC posted reviews to evaluate whether the conclusions of a paper were supported by its data and to highlight key methodological shortcomings when applicable to separate actionable evidence from questionable evidence.

The structure of the NCRC also provides a crucial training opportunity for doctoral students and postdoctoral fellows to understand the connections between academic literature and practice. Students and fellows practice distilling the meaning of a study and translating science into accessible language for decision makers. In addition to providing mentorship on science communication, faculty also meet regularly with students and fellows to reflect on which preprints and articles should be included on the NCRC website. The curation process helps to hone the skills of students and fellows to understand the current scientific landscape, gaps in knowledge, and which research questions are indispensable for moving the evidence base forward.

Despite these strengths, the sustainability of such a large effort is unclear. In particular, the NCRC has been unable to identify long-term funding to cover the costs of faculty time dedicated to the project, and this resource limitation poses a risk to the future of the endeavor. The lag between publication and our reviews is a concern, because it has reduced our ability to contribute to discussions about evidence in real time. These delays had multiple causes, including the lags between publication and indexing in PubMed, but a lack of salary support for the effort also contributed. Our ability to measure the impact of the NCRC on changes to knowledge or practice among our target audience has been limited, for multiple reasons. First, we have no information about our subscribers except their email addresses, and little can be gleaned about their motivation or purpose in receiving our newsletter from the email address alone. Second, any measurement of impact would almost certainly require interviews with members of our target audience, who had no time to spare from pandemic response in 2020 to participate in such endeavors. Third, the NCRC team has been stretched to keep up with the literature, leaving little time to focus on impact assessments, although future work focused on impact assessment should be considered. Nevertheless, continued use of the reviews, reflected in growing numbers of newsletter subscribers and increases in website views, and informal conversations with colleagues in our target audience suggest that the NCRC is a valued resource.

Because the COVID-19 pandemic has emphasized the necessity of collaboration between public health researchers and practitioners to save lives, we believe that the NCRC is one model of how this collaboration could be successful. Since its inception, the NCRC has been conceptualized as a critical training opportunity for the next generation of public health and clinical scientists in knowledge translation to improve decision-making. The NCRC approach could be useful to improve timely translation of data to action for other public health problems in which lags in knowledge translation persist, particularly if funding were available to support the effort. By using this model, we have attempted to improve the access of public health officials and clinicians to relevant evidence for action to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, we have also built capacity that can be applied to solving other public health problems, including future pandemics.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported in part by the Division of Intramural Research, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

ORCID iDs: Brooke A. Jarrett, MSPH  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2966-3521

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2966-3521

Amrita Rao, ScM  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9596-2418

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9596-2418

Chelsea S. Lutz, MPH  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5706-2144

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5706-2144

Eshan U. Patel, MPH  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2174-5004

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2174-5004

Ruth Young, MS  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8787-2391

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8787-2391

Emily S. Gurley, PhD, MPH  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8648-9403

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8648-9403

References

- 1. Palayew A, Norgaard O, Safreed-Harmon K, Andersen TH, Rasmussen LN, Lazarus JV. Pandemic publishing poses a new COVID-19 challenge. Nat Hum Behav. 2020;4(7):666-669. doi: 10.1038/s41562-020-0911-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chan Zuckerburg Biohub. CoronaCentral dashboard. Accessed July 2, 2021. https://coronacentral.ai

- 3. Horbach SPJM. Pandemic publishing: medical journals strongly speed up their publication process for COVID-19. Quant Sci Stud. 2020;1(3):1056-1067. doi: 10.1162/qss_a_00076 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Novel Coronavirus Research Compendium (NCRC). Accessed July 2, 2021. https://ncrc.jhsph.edu

- 5. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. COVID-19 SARS-CoV-2 preprints from medRxiv and bioRxiv. Accessed July 2, 2021. https://connect.biorxiv.org/relate/content/181