Abstract

Objective

The Targeted Highly Effective Interventions to Reverse the HIV Epidemic (THRIVE) demonstration project created collaboratives of health departments, community-based organizations, and clinical partners to improve HIV prevention services for men who have sex with men (MSM) and transgender women (TGW) of color. We administered an online survey from September 2018 through February 2019 to assess the collaboratives.

Methods

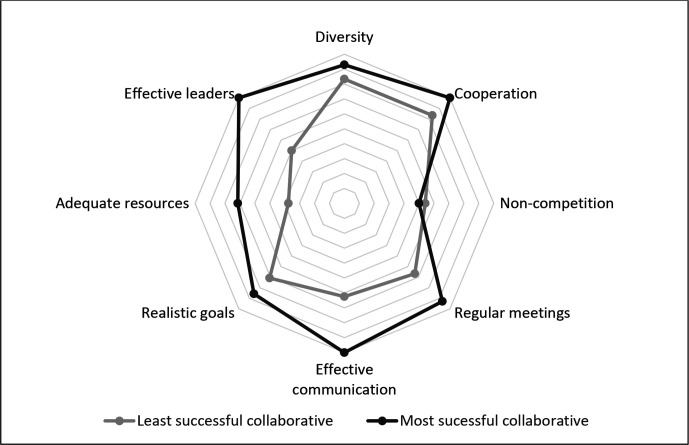

We used a Likert scale to measure agreement on collaborative characteristics. We used Fisher exact tests to compare success ratings by health department employment and funding status. We created a radar chart to compare the percentage agreement on key characteristics of the most and least successful collaboratives. We used a general inductive approach in the qualitative analysis of open-ended question responses.

Results

Of 262 survey recipients, 133 responded (51%); 49 (37%) respondents were from health departments. Most respondents (≥70%) agreed that their collaborative is diverse, cooperates, meets regularly, has realistic goals, has effective leadership, and has effective communication. Most respondents (87%) rated their collaborative as successful in implementing HIV prevention services for MSM and TGW of color. Comparison of the most and least successful collaborative found the greatest difference in respondent agreement in the presence of effective leadership, communication, and adequate resources. The most commonly cited challenge in the open-ended questions was inadequate resources. The most commonly cited success was increased provision of services, particularly preexposure prophylaxis.

Conclusions

Community collaboratives were considered successful by most collaborative members and may be an effective part of HIV prevention strategies.

Keywords: HIV prevention, PrEP, men who have sex with men, transgender women, people of color

Men of color who have sex with men (MSM) of color and transgender women (TGW) of color are disproportionately affected by HIV. 1,2 High-impact HIV prevention strategies can reduce the number of new HIV infections among MSM and TGW of color. Preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is a highly effective HIV prevention strategy; however, Black and Hispanic MSM are significantly less likely than White MSM to be aware of PrEP, to have discussed PrEP with a health care provider, or to have used PrEP within the past year. 3 Stigma, mistrust in the medical establishment, and health care disparities affecting MSM and TGW of color impede access to preventive health services, including PrEP. 4,5 Health departments can play an important role in overcoming health disparities by expanding the availability of HIV prevention services and by promoting collaboration among organizations already providing services in their communities. 6 Collaborative partnerships have been used to address various public health challenges, 7,8 but little is known about health department–led collaboratives to implement HIV prevention services for MSM and TGW of color.

The Targeted Highly Effective Interventions to Reverse the HIV Epidemic (THRIVE) demonstration project (2015-2020) supported 7 US health departments to provide comprehensive HIV prevention and care services for MSM and TGW of color by creating collaboratives consisting of funded and unfunded partnerships among health departments, community-based organizations (CBOs), and clinical providers. 9 The THRIVE project required that applicant sites demonstrate high rates of HIV morbidity or mortality, making lessons learned in these communities particularly valuable for US health departments that would be participating in phase 1 of the Ending the HIV Epidemic initiative being led by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 10 To be eligible for THRIVE, recipients had to meet 1 of 2 criteria: (1) represent a metropolitan statistical area or division with >2000 Black and/or Hispanic MSM living with diagnosed HIV or (2) represent a state in the fourth quartile for mortality rates as reported in its state progress report and have >1000 Black and/or Hispanic MSM living with diagnosed HIV in a specified metropolitan statistical area. THRIVE recipients were the departments of health in Alabama; Baltimore, Maryland; the District of Columbia; Louisiana; New York City; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; and Virginia. Recipient health departments received monetary support, training, and consultation with CDC throughout the demonstration project. Health departments provided monetary support to funded partners and training and consultation services to both funded and unfunded partners.

We evaluated the success of health departments in developing these collaboratives, factors related to successful collaborative function, and the contribution of the collaboratives to implementation of HIV prevention services for MSM and TGW of color.

Methods

We developed a survey based on a validated and published evaluation tool intended to assess effective collaboration, the Collaborative Assessment Tool. 11 The content of the tool was tailored for relevance to the THRIVE project and clarity for the intended audience; otherwise, the survey structure and questions were as described in the published tool. 11 A team of epidemiologists, physicians, and public health professionals at CDC reviewed and approved the final survey version before use. This project was determined to be not human subjects research and was approved through the Office of Management and Budget information collection review process.

The THRIVE project was active during 2015-2020; the survey was administered online from September 2018 through February 2019. The 7 THRIVE health departments provided email contact lists for the health department, CBO, and clinical site staff members involved in their local collaboratives. The survey link was emailed to all people on the collaborative contact lists. No incentives were provided for participation. Participants were able to review, edit, and save responses until the survey was submitted. The survey was divided into 3 sections: (1) respondent demographic information, (2) Likert and numerical scale questions about characteristics of the collaboratives, and (3) open-ended questions about collaborative challenges and successes. Our outcome in this analysis was collaborative success in implementing HIV prevention services for MSM and TGW of color. We analyzed aggregated data.

We described the number and proportion of respondents and nonrespondents by type of organization they represented and by geographic site to evaluate for evidence of nonresponse bias. We used a Likert scale to query respondents’ agreement with questions about collaborative characteristics. The scale ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree); responses of 4 (agree) or 5 (strongly agree) were categorized as agreement. Respondents rated their agreement by responding to a series of statements describing various traits or characteristics of the collaboratives. For example, respondents were asked to rate their level of agreement with the statement “members of the collaborative represent the cultural diversity of our community.” We summarized these characteristics as the following: adequate resources, cooperation, diversity, effective communication, effective leadership, noncompetition (ie, collaborative members do not compete with one another for clients), realistic goals, and regular meetings. Respondents also rated the success of the collaborative in implementing HIV prevention services for MSM and TGW of color on a numerical scale of 1 (completely unsuccessful) to 10 (completely successful); a rating >5 was considered successful implementation.

We described respondent demographic characteristics on the following: type of organization represented (CBO, health department, clinical, or other), receipt of THRIVE funds (yes or no), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic White, Hispanic, or other), age (categorized as 21-30, 31-40, 41-50, or >50), sex (male, female, or other), and sexual orientation (heterosexual, gay or lesbian, or other). We estimated percentage, median, and interquartile range (IQR) agreement on questions about collaborative characteristics and on ratings of the success of the collaborative in implementing HIV prevention services. We used Fisher exact tests to compare collaborative success ratings between (1) health department and non–health department staff members, (2) respondents who reported competition within the collaborative and respondents who denied competition, and (3) funded and unfunded partners. We constructed a radar chart in Microsoft Excel to describe the percentage of respondents who agreed with key collaborative characteristics in the collaboratives with the highest and the lowest median success rating. 12 We also used Fisher exact tests to compare percentage agreement with key collaborative characteristics in the highest-rated and lowest-rated collaboratives.

We used a general inductive approach to evaluate responses to the open-ended question; themes emerged through iterative reviews of responses 13 and were organized into a thematic codebook that was revised as reviews were made. 13 Codes were independently assigned to the responses by 2 reviewers (M.R.T., K.W.H.); we calculated k statistics to assess intercoder reliability. Responses that addressed >1 topic were categorized in multiple thematic categories. We did not include blank or uninterpretable responses (such as “skip” or “not applicable”) in the analyses. We used R version 4.0.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) for all analyses; P ≤ .05 was considered significant.

Results

Of 262 survey recipients, 133 responded (51% response rate; Table 1). Of the 133 respondents, 54 (41%) were CBO staff members and 49 (37%) were health department staff members. Most (n = 92; 69%) were from organizations that received THRIVE funds. Respondents reported their race/ethnicity as non-Hispanic Black (n = 65; 49%), non-Hispanic White (n = 40; 30%), Hispanic (n = 15; 11%), or other (n = 9; 7%). More than half (53%) of respondents were female, 68 (51%) were aged ≤40, 62 (51%) were heterosexual, and 34 (26%) were gay or lesbian. The distribution of respondents and nonrespondents was similar by type of agency and geographic site (Table 2).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of respondents (N = 133) to the THRIVE Collaborative Assessment Tool, 7 THRIVE sites,a United States, September 2018–February 2019

| Characteristic | No. (%)b |

|---|---|

| Type of agency represented by respondent | |

| Community-based organization | 54 (41) |

| Health department | 49 (37) |

| Clinical | 14 (11) |

| Other (eg, behavioral and social service providers, academic partners) | 15 (11) |

| Missing | 1 (1) |

| Received THRIVE funds | |

| Yes | 92 (69) |

| No | 11 (8) |

| Don’t know | 26 (20) |

| Missing | 4 (3) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 65 (49) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 40 (30) |

| Hispanic | 15 (11) |

| Otherc | 9 (7) |

| Missing | 4 (3) |

| Age, y | |

| 21-30 | 19 (14) |

| 31-40 | 49 (37) |

| 41-50 | 21 (16) |

| >50 | 30 (23) |

| Missing | 14 (11) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 71 (53) |

| Male | 51 (38) |

| Other | 7 (5) |

| Missing | 4 (3) |

| Sexual orientation | |

| Heterosexual | 68 (51) |

| Gay/lesbian | 34 (26) |

| Other | 25 (19) |

| Missing | 6 (5) |

Abbreviation: THRIVE, Targeted Highly Effective Interventions to Reverse the HIV Epidemic.

aTHRIVE recipients were departments of health in Alabama; Baltimore, Maryland; the District of Columbia; Louisiana; New York City; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; and Virginia.

bPercentages may not total to 100 because of rounding.

cIncludes Asian, American Indian/Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander, and other.

Table 2.

Respondents and nonrespondents to the THRIVE Collaborative Assessment Tool, by whether respondent worked for health department and by geographic site, 7 THRIVE sites, a United States, September 2018–February 2019

| Characteristic | Respondents, no. (%)

b

(n = 133) |

Nonrespondents, no. (%)

b

(n = 129) |

|---|---|---|

| Health department staff member | ||

| Yes | 49 (37) | 36 (28) |

| No | 84 (63) | 93 (72) |

| Geographic site b | ||

| Alabama | 20 (15) | 21 (16) |

| Baltimore | 24 (18) | 17 (13) |

| District of Columbia | 14 (11) | 22 (17) |

| Louisiana | 16 (12) | 11 (9) |

| New York City | 9 (7) | 11 (9) |

| Philadelphia | 28 (21) | 23 (18) |

| Virginia | 22 (17) | 24 (19) |

Abbreviation: THRIVE, Targeted Highly Effective Interventions to Reverse the HIV Epidemic.

aTHRIVE recipients were the departments of health in Alabama; Baltimore, Maryland; the District of Columbia; Louisiana; New York City; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; and Virginia.

bPercentages may not total to 100 because of rounding.

Most respondents agreed that their collaborative represents their community’s cultural diversity (88%; median [IQR] rating, 5 [4-5]), cooperates to provide services (87%; median [IQR] rating, 4 [4-5]), meets regularly (82%; median [IQR] rating, 4 [4-5]), has realistic goals (74%; median [IQR] rating, 4 [3-4]), has effective leadership (73%; median [IQR] rating, 4 [3-5]), and communicates effectively (70%; median [IQR] rating, 4 [3-4]). Fewer respondents agreed that their collaborative has adequate financial resources (55%; median [IQR] rating, 4 [2-4]) or is noncompetitive (48%; median [IQR] rating, 3 [2-4]). Of 67 respondents who reported their collaborative competed for clients, 52 (78%) agreed that members of the collaborative were able to cooperate to provide services.

Most respondents (n = 116; 87%) reported that that their collaborative was successfully implementing HIV prevention services for MSM and TGW of color. When evaluated by type of organization, similarly high proportions of health department (94%) and non–health department (83%) staff members rated their collaborative as successful (P = .11). Ninety percent of respondents from both funded and unfunded agencies rated their collaborative as successful (P > .99). Ninety-one percent of respondents who reported competition among collaborative members rated the collaborative as successful overall, compared with 96% of respondents who denied competition (P = .29).

All 7 sites were rated as successful in implementing HIV prevention services for MSM and TGW of color. The greatest difference in percentage agreement between the highest-rated and lowest-rated collaboratives were in effective leadership and effective communication (Figure). Respondent agreement with the characteristics was as follows: diversity (highest rated, 93%; lowest rated, 83%; P = .63), cooperation (highest rated, 100%; lowest rated, 83%; P = .28), noncompetition (highest rated, 50%; lowest rated, 54%; P > .99), regular meetings (highest rated, 93%; lowest rated, 67%; P = .12), effective communication (highest rated, 100%; lowest rated, 63%; P = .02), realistic goals (highest rated, 86%; lowest rated, 71%; P = .38), adequate resources (highest rated, 71%; lowest rated, 38%; P = .09), and effective leadership (highest rated, 100%; lowest rated, 50%; P = .002).

Figure.

Agreement among respondents (N = 133) about the presence of key characteristics in the collaboratives with the highest and lowest median success ratings in the Targeted Highly Effective Interventions to Reverse the HIV Epidemic (THRIVE) Collaborative Assessment Tool, 7 THRIVE sites, United States, September 2018–February 2019. THRIVE recipients were the departments of health in Alabama; Baltimore, Maryland; the District of Columbia; Louisiana; New York City; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; and Virginia. The outermost gridline of the radar chart represents 100% agreement and the innermost gridline represents no agreement.

We received 86 responses to the open-ended question about collaborative challenges. The following themes emerged from the responses to the question about major challenges: inadequate resources (45%), difficulties collaborating (43%), challenges reaching MSM and TGW of color (29%), inadequate leadership (26%), problems with communication (14%), data collection and management difficulties (8%), and too many changes during the project (7%) (Table 3). κ scores for the themes ranged from 0.71 to 1.00 and averaged 0.81.

Table 3.

Key themes and illustrative quotes among respondents (N = 133) to 2 open-ended questions in the THRIVE Collaborative Assessment Tool, 7 THRIVE sites, a United States, September 2018–February 2019

| Theme and subtheme b | No. (%) c of responses | Illustrative quote |

|---|---|---|

| What were the major challenges faced by your agency in building and maintaining the THRIVE collaborative? (86 responses) | ||

| Inadequate resources | 39 (45) | Funding was an issue as we had to look at sustainability in a context of uncertainty. |

| Fiscal | Adequate funding resources. | |

| Social, behavioral, and mental health services | One of our challenges was gathering and connecting to the resources in our county. For many service areas, the resources to support the most vulnerable populations are few and far between or hard to get to. | |

| Staff | Staff and leadership turnover within and across the collaborative. | |

| Time | The short duration of this project. Not enough time to build a sustainable collaborative. | |

| Difficulties collaborating | 37 (43) | The main challenge was the difficulty for teams composed of members of different agencies within the collaborative to work efficiently because of constraints within their agency. |

| Competition and lack of cooperation among agencies | Competing with various agencies and being in an area that is oversaturated with the type of support that we provide. | |

| Challenges integrating unfunded partners | Unfunded agencies are not willing to go to yet another meeting. | |

| Differences between agencies | Developing a universal system for workflow for collaboratives to follow is difficult due to each CBO’s internal agenda. | |

| Difficulties engaging partners | The biggest challenge in building the collaborative was that there wasn’t much buy-in from local institutions. | |

| Challenges reaching men who have sex with men and transgender women of color | 25 (29) | Understanding the Black LGBTQ community and providing and planning events with the community in mind. |

| Inadequate leadership | 22 (26) | Staff and leadership turnover within and across the collaborative. |

| Problems with communication | 12 (14) | Communication would be the only challenge I can say we have at times. |

| Data collection and management difficulties | 7 (8) | Competing priorities, extensive data collection requirements, lack of strong leadership. |

| Too many changes during the project | 6 (7) | Many changes from the health department rapidly. Not enough input in the decision-making process. |

| What were the major successes achieved by your agency in building and maintaining the THRIVE collaborative? (82 responses) | ||

| Provided services | 41 (50) | We have been able to build our STI and PrEP services much faster than anticipated. In turn, we have been able to meet the needs as they arise within our vulnerable populations. |

| PrEP services | Our major success for the program has been providing referrals and linkages to PrEP for those that have an unmet need. | |

| Access to services | Effectively addressed the barriers to accessing HIV prevention and treatment services. | |

| Linkage to services | Better integration of our internal services and speedier linkage to those services. | |

| Social, behavioral, and mental health services | Many clients have been linked to mental health and drug abuse services. | |

| Testing | The collaborative was very active with community testing events. Many people were tested. | |

| nPEP | The agency has definitely enhanced the array of services provided and educated the public about PrEP, nPEP. | |

| Workforce development | Development of workforce program, which increased economic growth within the community. | |

| Collaborated effectively | 36 (44) | We were able to work more closely with our community partners, which fostered cross-agency relationships that have proven to be invaluable. Seeing the positive effects gained from those relationships opened the door to other positive connections. |

| Reached men who have sex with men and transgender women of color | 20 (24) | More of the targeted interventions reached more of the intended community—services such as linkage to care and PrEP. |

| Provided navigation services | 12 (15) | Peer navigators working together, overcoming medical mistrust, harnessing community. |

| Conducted effective marketing and outreach | 12 (15) | Hosting town hall PrEP meetings and educational meetings about HIV research and sponsoring PrEP support groups. |

| Collected and shared useful data | 6 (7) | Getting a bigger picture to the work being done in the city around PrEP and HIV prevention by sharing data that otherwise would not have been available to the sites individually. |

| Provided useful staff training | 3 (4) | The establishment of subrecipient navigation programs, training staff, and responding to evolving data needs were the major successes as I see them. |

| Reduced HIV incidence | 1 (1) | 1. Built strong collaborative partnerships. 2. Effectively addressed the barriers to accessing HIV prevention and treatment services. 3. Reduced the incidence of HIV. |

Abbreviations: CBO, community-based organization; LGBTQ, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer; nPEP, nonoccupational postexposure prophylaxis; PrEP, preexposure prophylaxis; STI, sexually transmitted infection; THRIVE, Targeted Highly Effective Interventions to Reverse the HIV Epidemic.

aTHRIVE recipients were the departments of health in Alabama; Baltimore, Maryland; the District of Columbia; Louisiana; New York City; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; and Virginia.

bSubtheme categories included for 2 largest theme categories only.

cSome responses contained multiple themes, so column percentages total >100%.

We received 82 responses to the open-ended question about collaborative successes. The following themes emerged from the responses: provided services (50%), collaborated effectively (44%), reached MSM and TGW of color (24%), provided navigation services (15%), conducted effective marketing and outreach (15%), collected and shared useful data (7%), provided useful staff training (4%), and reduced HIV incidence (1%). κ scores for the themes ranged from 0.73 to 1.00 and averaged 0.86. Notably, 23 (56%) responses in the category “provided services” described PrEP services as an important collaborative success.

Discussion

Most staff members who participated in health department–led collaboratives found the collaborative successful in implementing HIV prevention services among MSM and TGW of color. This success is particularly notable because stigma, mistrust in the medical community, and health care disparities create challenges in engaging MSM and TGW of color in HIV prevention services. 5 Despite different community environments, resources, and challenges, most respondents reported that their collaborative cooperated effectively to provide services.

More than half of respondents reported that organizations within their collaborative competed for clients. However, most of the respondents who observed competition in their collaboratives still agreed that organizations were able to cooperate to provide services. Similar proportions of respondents who observed competition and respondents who did not observe competition reported that their collaborative was successful overall. These results suggest that the formal relationships developed by the collaborative structure were not able to overcome all sense of competition among agencies, but most respondents still felt their collaboratives were successful, despite the sense of competition. Overall, most respondents noted strong interorganizational collaboration, effective outreach to MSM and TGW of color, and successful service provision. The open-ended responses in particular indicated that many respondents observed that the creation of formal partnerships between organizations in collaboratives improved collaboration and access to and use of services by clients and patients. These partnerships appeared particularly effective in implementing PrEP services, the type of service reported most frequently by respondents when describing collaborative successes.

Most respondents agreed that their collaboratives were diverse, cooperated, had regular meetings, communicated effectively, had effective leadership, and were able to meet their goals. However, the comparison between the most and least successful collaboratives showed that the areas of greatest difference were leadership and communication. In addition, inadequate resources was the most commonly cited challenge among the open-ended responses. These findings suggest that paying particular attention to effective health department leadership, communication, and resource allocation may help health department–led collaboratives avoid some of the challenges faced by respondents.

Similar proportions of health department staff members and non–health department staff members, and respondents among funded and unfunded agencies, reported successful collaboratives. These data suggest that even when collaboratives faced challenges, such as concerns about leadership or resources, establishing and strengthening partnerships among agencies promoted provision of effective HIV prevention services.

Limitations

Our study had several limitations. First, it included only participants in a demonstration project, which could limit the generalizability of findings. Second, the overall number of people surveyed was small. However, the inclusion of people from 7 localities and various organization types allowed these findings to inform health departments who will be participating in phase 1 of the Ending the HIV Epidemic initiative. 10 Because the THRIVE project required that applicant sites demonstrate high rates of HIV morbidity or mortality, lessons learned in THRIVE may be particularly pertinent to communities with a similar need for enhanced HIV prevention services. Third, survey recipients were asked to comment on their own collaboratives and may have been more likely than people outside their collaboratives to report positively on their own programs. However, recipients were assured of the confidentiality of their responses, which were not linked to names and were analyzed in aggregate. In addition, success ratings were similar among respondents from funded and unfunded agencies.

Public Health Implications

Overall, we found that most staff members who participated in health department–led collaboratives of CBOs and clinical care providers described them as successful in implementing HIV prevention services for MSM and TGW of color. Health departments should consider developing organized collaboratives that include CBOs and clinical partners as part of their strategy to provide HIV prevention services to MSM and TGW of color. Key considerations are including in the collaborative organizations that serve the diverse populations in the community, promoting cooperation between organizations, ensuring effective communication among collaborative organizations, conducting regular meetings, setting realistic goals, identifying adequate resources, and establishing effective leadership.

The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Mary R. Tanner, MD  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2755-1123

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2755-1123

References

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas, 2018 (preliminary). HIV Surveill Rep. 2019;30:1-129. Accessed September 21, 2020. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html

- 2. Becasen JS., Denard CL., Mullins MM., Higa DH., Sipe TA. Estimating the prevalence of HIV and sexual behaviors among the US transgender population: a systematic review and meta-analysis, 2006-2017. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(1):e1-e8. 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kanny D., Jeffries WL., Chapin-Bardales J. et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in HIV preexposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men—23 urban areas, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(37):801-806. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6837a2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Calabrese SK., Krakower DS., Mayer KH. Integrating HIV preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) into routine preventive health care to avoid exacerbating disparities. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(12):1883-1889. 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Eaton LA., Driffin DD., Kegler C. et al. The role of stigma and medical mistrust in the routine health care engagement of Black men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(2):e75-e82. 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Derose KP., Gresenz CR., Ringel JS. Understanding disparities in health care access—and reducing them—through a focus on public health. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(10):1844-1851. 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Roussos ST., Fawcett SB. A review of collaborative partnerships as a strategy for improving community health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2000;21:369-402. 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.21.1.369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Paikoff RL., Traube DE., McKay MM. Overview of community collaborative partnerships and empirical findings: the foundation for youth HIV prevention. Soc Work Ment Health. 2007;5(1-2):3-26. 10.1300/J200v05n01_01 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . About THRIVE. 2019. Accessed September 21, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/research/thrive/about.html

- 10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Ending the HIV epidemic: a plan for America. 2020. Accessed September 21, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/endhiv/index.html

- 11. Marek LI., Brock DJP., Savla J. Evaluating collaboration for effectiveness: conceptualization and measurement. Am J Eval. 2014;36(1):67-85. 10.1177/1098214014531068 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Saary MJ. Radar plots: a useful way for presenting multivariate health care data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(4):311-317. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.04.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Thomas DR. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am J Eval. 2006;27(2):237-246. 10.1177/1098214005283748 [DOI] [Google Scholar]