Abstract

The autoimmune diseases are associated with the host immune system, chronic inflammation, and immune reaction against self-antigens, which leads to the injury and failure of several tissues. The onset of autoimmune diseases is related to unbalanced immune homeostasis. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are multipotent cells which have capability to self-renew and differentiate into various cell types that exert a critical role in immunomodulation and regenerative therapy. Under the certain condition in vitro, MSCs are able to differentiate into multiple lineage such as osteoblasts, adipocytes, and neuron-like cells. Consequently, MSCs have a valuable application in cell treatment. Accordingly, in this review we present the last observations of researches on different MSCs and their efficiency and feasibility in the clinical treatment of several autoimmune disorders including rheumatoid arthritis, type 1 diabetes, multiple sclerosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, inflammatory bowel disease, autoimmune liver disease, and Sjogren’s syndrome.

Keywords: Mesenchymal stromal cell, Autoimmune diseases, Stem cell therapy, Clinical application

Introduction

Autoimmune disorders include several chronic diseases which are frequently considered as organ-specific and systemic [1–3]. These diseases mainly occur because of the malfunction of immune system which mistakenly attack to own body’ cells and tissues [4–6]. Approximately 8–10% of the population is affected by autoimmune disorders which cause serious impairment, high mortality rate, and medical costs [7].

In recent years, stem cell-based therapy is progressively used as a therapeutic approach for various diseases such as autoimmune diseases. Stem cell transplantation, conventionally used for hematopoietic disorders, however, it is now established for the treatment of nonhematologic diseases [8–11]. The pivotal discovery of stem cells has provided a potential opportunity for accelerating tissue regeneration through switching damaged cells in paracrine and juxtacrine signaling modes. Mesenchymal stem/stromal cells (MSCs) display considerable trans-differentiation features into multiple lineages after implantation [12–14]. In order to utilize them in the clinical studies, it is obligatory to culture separated MSCs in vitro. Because of their ease collection procedure, existence in various tissues, differentiation into various cell lineages, and high proliferation rate, MSCs are more applied in stem cell therapy compared to the other stem cell types [15, 16]. The results of studies have demonstrated that MSCs can inhibit the proliferation and function of T lymphocytes, decrease the concentrations of tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), increase regulatory T (Treg) cells, regulate the expression of inflammatory mediators, and ameliorate bone injury [17–19]. The immunosuppressive and regenerative properties of MSCs show their great therapeutic ability in severe autoimmune disorders.

Considering these advantages, we provided a review of recent clinical studies which considered the efficiency of MSCs in autoimmune diseases including rheumatoid arthritis, type 1 diabetes, multiple sclerosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, inflammatory bowel disease, autoimmune liver disease, and Sjogren’s syndrome.

Mesenchymal stem cell

According to the current evidence, MSCs are spindle-shaped and resemble fibroblasts that can be isolated from a variety of sources such as umbilical cord (UC), Wharton’s jelly (WJ), adipose tissue, bone marrow (BM), teeth and menstrual fluid [15, 20]. The MSCs originally explained by Friendenstein et al. in 1966 as bone forming cells in BM; nevertheless, they are usually named MSCs because they present adult stem cell multipotency [21]. They can differentiate to endothelial cells [22], cardiomyocytes [23], cartilage, bone and other connective tissues at the single cell level in vitro [24]. The International Society of Cellular Therapy (ISCT) suggests three criteria to describe MSCs. First, these cells are adherent to plastic once cultured in tissue flasks under standard conditions. Second, they express a variety of markers include CD73, CD90, and CD105, but lack CD45, CD34, CD14/CD11b, CD79α/CD19, and HLA-DR, and finally, the cells can differentiate into osteoblasts, adipocytes, and chondroblasts in vitro [25]. In addition, MSCs exert immunosuppressive abilities via their paracrine properties and communication with various immune cells and display low level of human leukocyte antigen (HLA) I, and rarely expression of HLA II. There is also a lack of co-stimulatory molecules such as CD40, CD40L, CD80, CD86 in MSCs which make them evading of T cell recognition [26–29]. It was shown that MSCs regulate their local environment, cellular communications, and the release of several factors, and participate in regeneration of tissue injury [30–34]. Indeed, they possess a homing capacity, can migrate into damaged tissues, and have the ability to differentiate into local components of damaged tissues and the capacity to release growth factors, cytokines, and chemokines, which improve tissue regeneration [35, 36].

Clinical applications of mesenchymal stem cells

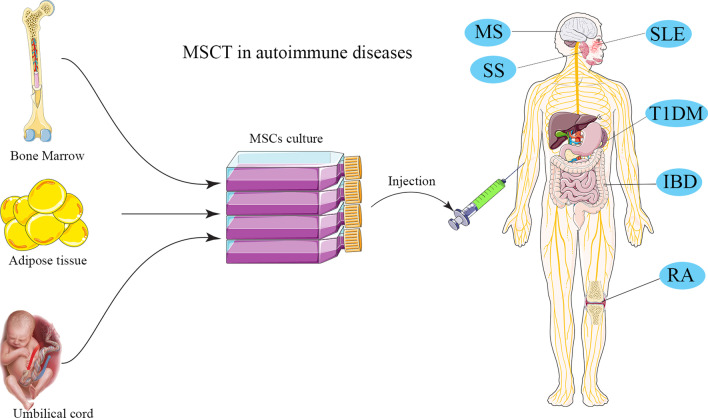

As mentioned in Table 1, many studies have evaluated the potential contribution of MSCs in treatment of various autoimmune diseases, which are discussed in the following sections (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Clinical application of mesenchymal stem cells in autoimmune diseases

| Disease | Infusion method | MSC source | Enrollment number | Cell mass | Outcome | NCT number | Reference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RA | I.V | Autologous BM-MSC | 9 | 1 × 106/kg | Clinical efficacy | NCT03333681 | [45] | |||

| RA | I.V | Autologous BM-MSC | 13 | 1 × 106/kg | Reduction of B cells response | NCT03333681 | [50] | |||

| RA | I.V | Autologous BM-MSC | 13 | 1 × 106/kg | Immunomodulatory effects of MSCT | NCT03333681 | [53] | |||

| RA | Intra-articular knee | Autologous BM-MSC | 30 | 40 × 106/joint | Clinical efficacy | NCT01873625 | [98] | |||

| RA | I.V | Allogeneic AD-MSC | 20 | 1 × 106/kg | Clinical efficacy | NCT01663116 | [46] | |||

| 20 | 2 × 106/kg | |||||||||

| 6 | 4 × 106/kg | |||||||||

| RA | I.V | hUC-MSC with IFN-γ | 63 | 1 × 106/kg | Clinical efficacy | Unknown | [47] | |||

| RA | I.V | hUC-MSC | 105 | 1 × 106/kg | Clinical efficacy/IFN-γ levels predicts the therapeutic effects of MSCs | Unknown | [48] | |||

| RA | I.V | hUC-MSC | 64 | 2 × 107 cell | UC-MSC cells + DMARDs therapy can be a safe, effective and feasible | NCT01547091 | [49] | |||

| RA | I.V | hUC-MSC | 172 | 4 × 107 cell | UC-MSC cells + DMARDs provide safe, and persistent clinical benefits | NCT01547091 | [51] | |||

| RA | I.V | hUC-MSC with LG | 119 | 4 × 107 cell | LG + UC-MSCs can improve the curative effect of RA patients | NCT01547091 | [99] | |||

| RA | I.V | hUC-MSC | 3 | 2.5 × 107cell | Clinical efficacy | NCT02221258 | [52] | |||

| 3 | 5 × 107 cell | |||||||||

| 3 | 1 × 108 cell | |||||||||

| T1DM | I.V | hUC-MSC | 53 | 1 × 106/kg | Clinical efficacy | Unknown | [55] | |||

| T1DM | I.V | hUC-MSC | 42 | 1.1 × 106/kg | Clinical efficacy | NCT01374854 | [58] | |||

| BM-MNC | 106.8 × 106/kg | |||||||||

| T1DM | I.V | AD-ASC + Vit D | 9 | 1 × 106/kg | Clinical efficacy | NCT03920397 | [56] | |||

| T1DM | I.V | AD-ASC + Vit D | 13 | 67.37 ± 7.65 × 106cells | Clinical efficacy | NCT03920397 | [57] | |||

| T1DM | I.V | Autologous BM-MSC | 20 | 2.1–3.6 × 106/kg | Clinical efficacy | NCT01068951 | [59] | |||

| T1DM | I.A | IS-AD-MSC + autologous BM-HSC | 10 | 5.3 × 106/ml | Autologous IS-AD-MSC + BM-HSC co-infusion offers better long-term control of hyperglycemia | Unknown | [60] | |||

| IS-AD-MSC + allogenic BM-HSC | 5.1 × 106/ml | |||||||||

| T1DM | I.A | IS-AD-MSC plus BM-HSC | 10 | 2.7 × 104/kg | Clinical efficacy | Unknown | [100] | |||

| 60.55 × 106/kg | ||||||||||

| T1DM | I.A | IS-AD-MSC plus BM-HSC | 11 | Unknown | Clinical efficacy | Unknown | [101] | |||

| T1DM | I.V | WJ-MSC | 29 | 2.6 ± 1.2 × 107 cells | Clinical efficacy/restoration of function islet β cells | Unknown | [61] | |||

| MS | I.V | Autologous BM-MSC | 10 | 1–2 × 106/kg | Clinical efficacy | NCT00395200 | [68] | |||

| MS | I.T | Autologous BM-MSC | 10 | 110 ± 23.1 × 106/cells | Clinical efficacy | NCT01895439 | [72] | |||

| MS | I.V | Autologous BM-MSC | 10 | 1.6 × 106/kg | Clinical efficacy | NCT00395200 | [69] | |||

| MS | I.T | Autologous BM-MSC | 10 | 8.73 × 106cells | Feasibility of autologous MSC for treatment of MS patients | Unknown | [102] | |||

| MS | I.T | Autologous BM-MSC | 10 | 3–5 × 107cells | Clinical but not radiological efficacy | Unknown | [103] | |||

| MS | I.T | Autologous BM-MSC | 25 | 29.5 × 106cells | Safe and feasible therapeutic approach | Unknown | [104] | |||

| MS | I.T & I.V | Autologous BM-MSC | 15 | 2.5 × 106cells | Clinically feasible and relatively safe procedure and induces immediate immunomodulatory effects | NCT00781872 | [70] | |||

| MS | I.T & I.V | Autologous BM-MSC | 48 | 1 × 106/kg | Clinical efficacy/I.T administration was efficacious than the I.V | NCT02166021 | [64] | |||

| MS | I.V | Autologous AD-MSC | 10 | 1 × 106/kg | Safe and feasible | NCT01056471 | [71] | |||

| 9 | 4 × 106/kg | |||||||||

| MS | I.V | hUC-MSC | 20 | 20 × 106/cells | Safe and feasible | NCT02034188 | [65] | |||

| MS | I.V | hUC-MSC | 23 | 4 × 106/kg | High potential for hUC-MSC treatment of MS | Unknown | [105] | |||

| MS | I.V | Placenta-MSC | 16 | 15 × 107/cells | Safe and well tolerated in patients with MS | Unknown | [73] | |||

| 6 × 108/cells | ||||||||||

| MS | I.T | MSC-NP | 20 | 5.3 × 106 to 1 × 107 cells | Clinical efficacy | NCT01933802 | [66] | |||

| MS | I.T | MSC-NP | 18 | 9.4 × 106cells | Clinical efficacy | NCT01933802 | [67] | |||

| SLE | I.V | BM-MSC | 58 | 1 × 106/kg | Clinical efficacy | NCT00698191 | [106] | |||

| SLE | I.V | BM-MSC | 15 | 1 × 106/kg | Clinical efficacy | NCT00698191 | [107] | |||

| SLE | I.V | BM-MSC | 4 | ≥ 1 × 106/kg | Clinical efficacy | NCT00698191 | [108] | |||

| SLE | I.V | hUC-MSC | 178 | 1 × 106/kg | Safe and feasible | NCT00698191 | [109] | |||

| SLE | I.V | hUC-MSC | 40 | Unknown | 16 patients had no clinical response | NCT01741857 | [80] | |||

| Seven patients relapse after 6 months | ||||||||||

| SLE | I.V | hUC-MSC | 79 | 1 × 106/kg | UC-MSCs suppressed T cell proliferation in lupus patients by secreting IDO | NCT01741857 | [82] | |||

| SLE | I.V | hUC-MSC | 18 | 2.8 × 108/cells | hUC-MSC has no apparent additional effect over and above standard immunosuppression | NCT01539902 | [76] | |||

| SLE | I.V | BM-MSC | 81 | 1 × 106/kg | Clinical efficacy | Unknown | [110] | |||

| hUC-MSC | ||||||||||

| SLE | I.V | BM-MSC | 35 | 1 × 106/kg | Clinical efficacy | NCT00698191 | [77] | |||

| hUC-MSC | ||||||||||

| SLE | I.V | hUC-MSC | 16 | 1 × 106/kg | Clinical efficacy | NCT00698191 | [81] | |||

| SLE | I.V | BM-MSC | 87 | 1 × 106/kg | Clinical efficacy | Unknown | [111] | |||

| hUC-MSC | ||||||||||

| IBD | I.L | AD-MSC | 5 | 3–30 × 106/cells | Safe and feasible | Unknown | [112] | |||

| IBD | I.L | AD-MSC | 107 | 12 × 107/cells | Clinical efficacy | NCT01541579 | [86] | |||

| IBD | I.L | Autologous AD-MSC | 5 | Unknown | Safe and feasible | Unknown | [113] | |||

| IBD | I.L | AD-MSC | 24 | 2 × 107/cells | Safe and feasible | NCT01372969 | [114] | |||

| IBD | I.V | Autologous BM-MSC | 4 | 2 × 106/kg | Clinical efficacy | NCT01659762 | [115] | |||

| 4 | 5 × 106/kg | |||||||||

| 4 | 10 × 106/kg | |||||||||

| IBD | I.V | Autologous BM-MSC | 10 | 1–2 × 106/kg | Safe and feasible | NTR1360 | [116] | |||

| IBD | I.V | BM-MSC | 16 | 2 × 106/kg | Clinical efficacy | NCT01090817 | [3] | |||

| IBD | I.V | hUC-MSC | 41 | 1 × 106/kg | Clinical efficacy | NCT02445547 | [88] | |||

| IBD | I.L | BM-MSC | 5 | 1 × 107/cells | Clinical efficacy | NCT01144962 | [89] | |||

| 5 | 3 × 107/cells | |||||||||

| 5 | 9 × 107/cells | |||||||||

| IBD | I.V | BM-MSC | 30 | 3 × 106/kg | Safe and effective | Unknown | [117] | |||

| IBD | I.L | BM-MSC | 5 | 1 × 107/cells | Clinical efficacy | NCT01144962 | [90] | |||

| 5 | 3 × 107/cells | |||||||||

| 5 | 9 × 107/cells | |||||||||

| SS | I.V | hUC-MSC | 24 | 1 × 106/kg | Safe and effective | NCT00953485 | [93] | |||

RA, rheumatoid arthritis; T1DM, type 1 diabetes mellitus; MS, multiple sclerosis; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; SS, Sjogren’s syndrome; I.V, intravenous; I.T, intrathecal; I.L, intralesional; I.A, interatrial; MSC, mesenchymal stem cell; BM, bone marrow; hUC, human umbilical cord; AD, adipose tissue; ASC, adipose stem cell; IS, insulin-secreting

Fig. 1.

Clinical application of MSCs from different sources in treatment of autoimmune diseases. RA, rheumatoid arthritis; T1DM, type 1 diabetes mellitus; MS, multiple sclerosis; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; SS, Sjogren’s syndrome

Rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is the most common systemic autoimmune disease worldwide. It is characterized by articular inflammation, synovial membrane hyperplasia as well as progressive joint damage, cartilage and bone destruction which worsening disability over time. The onset of RA is related to unbalanced immune homeostasis, most considerably, between T helper 17 (Th17) and Tregs lead to the activation of autoreactive immune cells which attack collagen-rich joint regions [37, 38]. Patients with RA have also elevated risk for developing cardiovascular disease in comparison with general population [39]. To treat RA, conventional drugs including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), corticosteroids, slow-acting anti-rheumatic drugs (SAARDs), and disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) are recommended in accordance with the severity of pathology [37, 40]. Methotrexate (MTX) remains the primary preferred antirheumatic drug and is the best candidate for RA therapy which ordinarily recommended to these patients [41]. As the mentioned drugs often cause liver injury, gastrointestinal injury, kidney side effects, BM suppression, and psychological disorders, the search for new innovative therapeutic approaches is an important issue [41, 42]. Studies have shown that MSCs decrease the production of the proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and interferon-γ (IFN-γ), whereas simultaneously increases secretion of anti-inflammatory cytokines like interleukin-10 (IL-10) and IL-4 which play a major role in tissue regeneration [43]. These features suggest that MSCs could be an emerging therapeutic option in treatment of RA. The results of studies have also indicated that MSCs can ameliorate the RA through different mechanisms such as suppression of Th17 cells, reduction of inflammatory cytokines, and up-regulation of Treg cells (Fig. 2) [44].

Fig. 2.

MSCs ameliorate RA by regulating T cells. MSCs can regulate the balance of T cells by homing to the articular cavity and releasing various cytokines that elevate the anti-inflammatory activity of the environment. T cells are also regulated by the transfer of mitochondria from MSCs. In addition, Th17 cells differentiation suppressed by costimulatory molecules ICOS (inducible costimulatory), and TL1A (TNF-like ligand 1A)

In a clinical report by Ghoryani et al. [45], autologous BM-MSCs were applied for treatment of patients with refractory RA. All nine participants intravenously received 1 × 106 autologous BM-MSCs/kg. After MSCT, a major decrease in Th17 percentage and a significant increase in regulatory T cells were observed. Furthermore, disease activity score 28-erythrocyte sedimentation rate (DAS28-ESR) and visual analogue scale (VAS) were significantly reduced, but no noticeable difference was detected for serum C-reactive protein (CRP) and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) levels after the intervention. These findings propose that autologous BM-MSCs can ameliorate refractory RA. In 2017, a multicenter, single blind, randomized phase Ib/IIa clinical trial using adipose-derived MSCs (AD-MSCs) in 53 patients with RA was reported [46]. Three groups were enrolled in this study which intravenously injected with different doses of AD-MSCs (1, 2, and 4 × 106 cells per kg of body weight). Overall, 141 adverse effects were observed in these participants that 133 were of moderate intensity (94%), and there were no life threatening effects, (grade 4) or deaths. The clinical advantage achieved in RA patients diminished or fluctuated after 12 weeks of cell administration, demonstrating that it is vital to have a repeat transplant. Moreover, Xu et al. [47] demonstrated that IFN-γ is an important mediator in determining the impact of MSCs in RA therapy. They showed that MSC + IFN-γ combination therapy synergistically augments the potential of MSC therapy in participants with RA without any adverse events during 1 year follow up.

Yang and coworkers additionally supported the therapeutic effects of UC-MSCs in patients with persistently active RA [48]. Their results showed that the percentage of Tregs and Th17 was increased and decreased, respectively. Also the concentrations of IL-6 and TNF-α were reduced and the levels of IL-10 were increased. These findings suggest that MSCs could play main roles in regulating immune homeostasis. Furthermore, serum IFN-γ levels predict the therapeutic effect of MSCT; a transient increase in serum IFN-γ (> 2 pg/ml) levels was observed before changes in levels of IL-6, TNF-α, IL-10, and the Treg/Th17 ratio. Wang and colleagues [49] performed another clinical phase I/II trial included 64 refractory RA patients. These patients received 40 mL of UC-MSC product (2 × 107 cells/20 mL) intravenously after 100 mL normal saline infusion. The results showed that Health index (HAQ) and DAS28 reduced after intervention. Also, serological markers and symptoms had improved, and there were no serious adverse events.

A study conducted by Gowhari et al. in 2020 has also examined the effect of autologous MSCs in thirteen patients with refractory RA. The results showed that MSCT suppressed B lymphocytes via decreasing the concentration of B-cell activating factor (BAFF) and a proliferation-inducing ligand (APRIL) cytokines as well as reducing the expression of their receptors on the B-cell surface. Their findings demonstrated a substantial decrease in the plasma levels of BAFF and APRIL following MSC administration, suggesting the significant effects of MSCs on humoral responses. These outcomes proposed that BAFF could be a hopeful candidate for subsequent evaluation of the pathogenesis of RA [50]. According to Wang et al. [51] clinical study, intravenous administration of UC-MSCs (4 × 107 cells) in 172 individuals with RA ameliorates the disease which was generally associated with reduced expression levels of several inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. In addition, the percentage of Treg and the IL-4 producing Th2 was increased. No serious adverse events were also observed during and after infusion of UC-MSCs. The main goal from the study was that DMARDs plus UC-MSCs infusion was harmless and effective in reducing disease activity in patients with refractory RA than controls receiving DMARDs plus medium without UC-MSCs. Similarly, in a clinical phase Ia study by PARK et al., UC-MSCs were applied for treatment of RA. The patients were intravenously injected with 2.5 × 107, 5 × 107, or 1 × 108 cells of UC-MSCs. Their findings illustrated enhanced symptoms and serological marker in all of the patients. No major adverse events were observed up to 4 weeks after each infusion of UC-MSCs [52].

Recently, Ghoryani et al. [53] indicated that intravenous injection of 1 × 106 autologous BM-MSCs per kg into 13 patients with refractory RA significantly up-regulates the gene expression of forkhead box P3 (FOXP3) in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) after 1 year. Their data also presented the appropriate immunomodulatory potential of the BM-MSCs on Tregs in RA patients, and authors hypothesized that the elevation in the number of MSCs could support their immunosuppressive properties in these patients.

Summarily, these data exhibited that MSCT could be a hopeful, safe, and impressive option for the clinical therapy of RA, considerably ameliorate the clinical symptoms of patients, and prevent disease progression.

Type 1 diabetes

Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) is a group of autoimmune diseases wherein autoreactive immune cells, especially CD4+ T cells, target pancreatic beta cells and cause complete insulin deficiency [54]. Increasing evidence has shown the therapeutic advantages of MSCs in clinical treatment of T1DM. For instance, Lu et al. [55] performed a nonrandomized, open-label, parallel controlled clinical report in which 1 × 106/kg allogeneic UC-MSCs were infused to 53 patients with T1DM, followed by an another dose after 3 months. They have found that the complete remission rate was 40.7% during 1-year follow-up. They have also showed that the level of postprandial C-peptide was obviously elevated between the adult-onset T1DM, however, its alteration was not obviously different among the juvenile-onset T1DM. No transplant-related severe adverse effects were observed.

In a recent pilot study, patients with T1DM were administered by one dose of 1 × 106/kg allogenic adipose tissue-derived stromal/stem cells (ASCs) and cholecalciferol 2000 UI/day for 6 months and compared with controls [56]. The authors declared that the glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1C) values were noticeably improved without a remarkable elevation in insulin dose/kg that might be followed by the up-regulation in basal insulin release reported in those patients. There were several side effects in these patients including transient headache, abdominal cramps, scotomas, thrombophlebitis, and mild local reactions. Nonetheless, the number of participants in this trial was too low and the follow-up period was short. Taken together, treatment with ASC was safe and caused few or transient adverse events. Recently, in a similar study conducted by Araujo et al. [57], 13 patients were transplanted with 1 × 106 per kg allogenic ASCs and cholecalciferol 2000 UI/day for 3 months and compared with control group. This study also showed the efficacy and safety of allogenic ASCs in T1DM therapy. No serious side effects associated with ASCs were observed in these patients.

In another study conducted by Cai et al. [58], 42 patients with T1DM were randomized to receive UC-MSCs (1.1 × 106/kg) plus 106.8 × 106/kg autologous BM-mononuclear cell (MNCs). Within 1 year, C-peptide was elevated, HbA1c reduced, fasting glycemia decreased, and daily insulin requirements decreased. Based on these results, UC-MSC and BM-MNC were safe and led to the improvement of metabolic measures in patients with T1DM. Carlsson et al. demonstrated that the autologous MSCT in new onset T1DM patients could be an efficient and safe approach to interfere with the process of T1DM and protect or restore pancreatic β cells function [59].

In the other study, 20 individuals divided into two groups; group 1 received autologous insulin-secreting AD-MSC (IS-AD-MSC) + BM-derived hematopoietic stem cell (BM-HSC) and group 2 treated with allogenic IS-AD-MSC plus BM-HSC [60]. No serious effects were reported with continual progress in HbA1c and serum C-peptide in both groups with a reduction in glutamic acid decarboxylase antibodies and decrease in mean insulin requirement. Their observations illustrated that autologous IS-AD-MSC injection showed better response in patients than allogenic IS-AD-MSC infusion.

In 2013, a double-blind study was reported that used intravenous infusion of WJ-MSCs in 29 patients with T1DM [61]. There were no reported adverse events and both the HbA1c and C peptide were significantly improved during the follow-up period. These findings suggested that the infusion of WJ-MSCs is safe and feasible for the treatment of T1DM.

Multiple sclerosis

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic autoimmune inflammatory disorder of the central nervous system (CNS). However, the exact pathophysiology of MS remains unclear. It is mainly concurred that autoreactive T cells, stimulated by either self-reactive or cross-reactive antigens, result in demyelination and progressive neurodegeneration of the CNS. In spite of the fact that available therapies like drugs help to the reduction of MS development or decrease disability in these patients, they lead to serious side effects and do not reverse the manifestations of MS [62, 63].

In 2020, a double-blind, randomized controlled trial was reported that used intrathecal (IT) and intravenous (IV) infusion of autologous BM-MSCs (1 × 106/kg) for treatment of 48 patients with progressive MS [64]. The participants divided into three groups according to injection method (IT or IV) and received a single infusion of BM-MSCs or sham injections. Their findings demonstrated positive results (Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)) in all predefined primary end points. No severe adverse effects were observed. However, they revealed that IT administration was more effective than the IV in several parameters of the disease. Despite the above mentioned, a larger phase III study is warranted to confirm these observations.

Furthermore, in a research by Riordan et al., 20 patients with MS was intravenously administrated with UC-MSCs [65]. The authors indicated that MS symptoms were considerably ameliorated by MSCT. Furthermore, EDSS scores as well as bladder, bowel, sexual dysfunction, and quality of life were improved. Also, MRI scans of the brain and the cervical spinal cord displayed inactive lesions and did not report any serious adverse events during or after intervention. However, headache or fatigue was noted as probably associated with the intervention.

In a phase I open-label clinical trial by Harris et al. [66], 20 patients with progressive MS were intrathecally injected with autologous BM-MSC-neural progenitors (NPs) every 12 weeks for a total of 3 doses (1 × 107 cells per dose). Their observations demonstrated that intrathecal MSC-NPs intervention was safe and well tolerated. In addition, the results represented an improvement in EDSS, muscle strength, and bladder function, respectively, following intrathecal MSC-NP administration. No severe adverse effects or hospitalizations related to intrathecal MSC-NP treatment were observed. The authors also hypothesized that a larger phase II placebo-controlled study is warranted to identify efficacy of intrathecal MSC-NP intervention in patients with MS.

In another long-term phase I clinical study which was conducted by Harris et al. [67], 20 patients with progressive MS were enrolled. The patients from 2014 to 2016 received three times IT injections of autologous MSC-NPs at an average dose of 9.4 × 106 cells (target dose was 1.0 × 107 cells). The results exhibited improvement in EDSS, and the timed 25-foot walk (T25FW). Furthermore, CSF investigation showed a decline in C–C motif chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2) and an elevation in IL-8, hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), and C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12 (CXCL12) after intervention. There were no serious adverse events related to IT-MSC-NP treatment. Nevertheless, the number of participants of this study was small, and there was no blinding and placebo group for comparison. Similarly, Connick and colleagues represented the improvement in MS patients after MSC treatment [68]. In another study by Connick et al. [69], MSCT ameliorated patients with progressive MS. A single dose of 1.6 × 106 per kg autologous BM-MSCs were intravenously administrated into the patients. They did not find any severe adverse effects. The results showed an enhancement in EDSS, log of minimum angle of resolution (logMAR) visual acuity, and low contrast visual acuity. They did not recognize any considerable effects on color vision, visual fields, macular volume, retinal nerve fiber layer thickness, or optic nerve magnetization transfer ratio. Taken together, the results of this intervention showed their neuroprotective effects in MS patients. In a study by Karussis et al., 15 MS patients were intrathecally received 2.5 × 106 cells autologous BM-MSCs, also five of the total patients received intravenous infusion of BM-MSCs (2.5 × 106 cells) [70]. The EDSS analysis represented positive results in MSC treatment. No serious adverse effects were showed during follow-up. Immunological analysis exhibited an increase in Tregs, reduction of proliferative responses of lymphocytes, and dendritic cells and a similar reduction in the number of Th cells. Interestingly, the quantitative analysis on MRI showed dissemination of MSCs from the infusion site to the ventricles of the CNS.

Fernandez et al. [71] reported a triple-blind, placebo-controlled study that involved 30 patients with MS who divided into two groups. Group 1 injected with low-dose (1 × 106 cells/kg) and group 2 received high-dose (4 × 106 cells/kg) autologous AD-MSCs and followed for 1 year. Evidence for this treatment showed an inconclusive trend of efficacy. There was just one major untoward effect in the MSC therapy.

Moreover, in a phase I/IIa clinical trial, ten patients with MS were injected of autologous BM-MSCs conditioned medium (MSC-CM) via the intrathecal route for the first time [72]. The results showed a general trend of enhancement in all the analysis, but the lesion volume elevated considerably. No serious adverse effects were reported during study. In addition, they demonstrated an association between a reduced white matter lesion number at baseline and higher IL-6, IL-8, and VEGF in MSC-CM content.

Another randomized, placebo clinical study which was conducted by Lublin and colleagues [73] applied placenta mesenchymal-like cells for treatment of 16 patients suffering from relapsing–remitting or progressive MS. Two groups participated in this trial who received low-dose (15 × 107cells) and high-dose (6 × 108cells) injection of these cells. According to the results, the safety and feasibility of this therapy were demonstrated in these patients. However, anaphylactoid reaction was seen as grade 1 side effects in one of the patients.

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), characterized by the high production of nuclear autoantibodies, is a chronic inflammatory autoimmune disease, which result in antibody-antigen immune complexes deposition in various organs [74]. In addition to an imbalance of Th1/Th17/Tregs, it seems that the regulatory B cells (Bregs) have a key role in pathogenesis of the SLE [75].

Deng et al. [76] performed a prospective, randomized, double-blind clinical study with a total infusion dose of 2 × 108 UC-MSCs in 18 patients with SLE. The results illustrated an improvement in renal function and decreased proteinuria, whereas serum albumin has elevated. In addition, other indices of SLE were improved. These comprised SLE Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI), British Isles Lupus Assessment Group (BILAG), anti-double-stranded DNA antibody (dsDNA) antibody and antinuclear antibody (ANA) titers and serum complement C3 and C4 concentrations. Four major adverse effects were also reported during study. Unfortunately, the study was abandoned when it had become apparent that the study would be unlikely to establish a positive treatment effect for UC-MSC.

Li et al. [77] have been shown that BM-MSCs could improve hematological abnormality and clinical remission in SLE patients with refractory cytopenia, which might be associated with increased Treg and decreased Th17.

It has also been declared that the soluble human leukocyte antigen-G (sHLA-G), a non-classical HLA class I molecule, is considerably up-regulated in serum of SLE patients along with the increase of Tregs following the administration of UC-MSCs which alleviate SLE [78]. Additionally, another important immunomodulatory effects of MSCs are related to IL-10 which induce secretion of HLA-G5 molecule [79].

Wang et al. [80] also performed a clinical trial that included 40 patients with active and refractory SLE. Their observations exhibited a significant decline in SLEDAI and BILAG scores as well as proteinuria, serum creatinine, and urea nitrogen. Additionally, serum concentration of albumin and complement amplified after UC-MSC infusion. No administration-related adverse events were showed and all participants tolerated the intervention well. However, seven patients relapsed 6 months after intervention, showing the requirement for a second treatment to avoid relapse. Likewise, Sun et al. [81] illustrated that the injection dose of UC-MSCs was directly associated with their efficacy. They also found that MSCT ameliorated disease activity, serologic changes, and stabilization of proinflammatory cytokines. In another study, the authors showed that allogeneic UC-MSCs mediate immunosuppression via suppression of T cell proliferation in SLE patients by releasing high levels of indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase (IDO) [82].

In addition, a study was conducted by Wang et al. [83] in 2016 to evaluate the safety of allogeneic UC-MSC therapy for refractory SLE patients. Nine patients were administrated intravenously at days 0 and 7 and followed up during 6 years. There were no adverse effects like fluster, headache, nausea, or vomit in these patients.

Inflammatory bowel disease

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic inflammatory gastrointestinal and autoimmune disease that includes ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD). IBD is mostly resulted from inappropriate and ongoing immune response of genetically susceptible hosts to pathogenic organism [84].

Several studies have shown that therapeutic potential of MSCs in treatments of IBD could restore epithelial barrier integrity [85]. In a phase 3 clinical study by Panés et al. [86], 212 patients were injected intralesionally with 120 × 106 allogeneic AD-MSCs. The results of the study revealed that the treatment group achieved combined remission in the intention-to-treat (ITT) and modified ITT populations at 24 weeks after treatment, showing the efficiency and safety of MSC therapy in CD. Eighteen of the total patients experienced treatment-related adverse events such as anal abscess and proctalgia. Philandrianos et al. [87] also reported that after administration of autologous adipose-derived stromal vascular fraction (ADSVF), perianal Crohn’s fistulas had clinically healed with complete re-epithelialization.

In a randomized controlled clinical trial conducted by Zhang et al., 82 patients were intravenously received UC-MSCs [88]. According to their findings, CD symptoms were remarkably ameliorated by MSC injection. CD activity index (CDAI), Harvey–Bradshaw index (HBI), and corticosteroid level were also improved. There were no further MSCT associated adverse events. In a phase 2 study, Forbes et al. exhibited that infusion of allogeneic MSCs improved CDAI and CD endoscopic index of severity (CDEIS) scores in patients with luminal CD refractory to biologic therapy [3].

In a long-term retrospective trial by Barnhoorn et al. [89], 21 participants with refractory CD were treated with 1 × 107/kg BM-MSCs. The 4-year follow-up results exhibited that Crohn’s fistulas closure rates had clinically alleviated. In none of the participants anti-HLA antibodies could be identified 24 weeks and 4 years following MSCT. This long-term study displayed that MSCT is able to ameliorate fistulas in CD patients and recovered patients’ quality of life. Furthermore, any adverse events thought to be associated with MSCT. Molendijk et al. [90] described another clinical double-blind research included 21 patients who were distributed into three groups and given a single injections of 1 × 107, 3 × 107, and 9 × 107 BM-MSCs. The results indicated that local treatment with 3 × 107 MSCs could more efficiently promote healing of perianal fistulas.

Therefore, MSCT can be effective, feasible, and safe treatment method which noticeably increase fistulas closure rates, improve CDAI and CDEIS scores, and promote patients’ quality of life.

Sjögren’s syndrome

Sjogren’s syndrome (SS) is one of the three most common autoimmune disorders in which lymphocytes infiltrate into salivary and lacrimal glands [91]. It is a multifaceted disorder and the hallmark characteristics include dry mouth and eyes, and joint pain [91, 92]. Due to their beneficial abilities in suppression the differentiation and proliferation of many immune cells, production of inflammatory factors, and secretion of antibodies, their injection has been used as a novel approach to treat SS.

In a study performed by Xu etal., 24 participants with SS were intravenously administrated with UC-MSCs [93]. They showed that SS manifestations were notably decreased, the Sjogren’s syndrome Disease Activity Index (SSDAI) and VAS were ameliorated, and salivary flow rate increased by MSCT. However, no serious adverse events occurred during or after MSC administration. The results revealed that the beneficial properties of MSCT in treatment of diseases were attributed to their immunomodulatory feature such as regulation of CD4+ T lymphocytes, up-regulation of Tregs and Th2 cells, and down-regulation of T17 and Tfh inflammatory reactions. In addition, they also exhibited a vital role of the stromal cell-derived factor-1/C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 (SDF-1/CXCR4) axis in guiding MSC toward inflammation sites, to play inhibitory activities and improved the function of salivary glands.

Autoimmune liver disease

Autoimmune liver disease (AILD) is one of the chronic renal conditions resulting from malfunction of the immune system that including autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), and primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC). The clinical symptoms of these conditions include: fatigue, reduced appetite, liver pain, and scleral icterus, and cause abnormal levels of liver function markers such as alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT), IgM, IgG, and presence of autoantibodies in blood tests [94, 95].

In a pilot study conducted by Wang et al., seven patients with PBC were intravenously administrated with UC-MSCs (0.5 × 106cells/kg) once every month on three times [96]. After MSCT, serum ALP and GGT values were meaningfully reduced, but no adverse events were observed during and after trials. Some of the common manifestations of PBC patients such as fatigue and pruritus were significantly ameliorated. These findings indicated that MSCT can reduce the severity of PBC and is safe and feasible procedure. In another study, ten patients with PBC were received a single dose of 3–5 × 105cells/kg allogeneic BM-MSCs [97]. The results of this study demonstrated that the life quality of the participants was enhanced after MSCT. Liver biomarkers exhibited that the level of ALT, AST, GGT, IgM, and direct bilirubin remarkably reduced from baseline after intervention during the 12-month follow-up period. Furthermore, the level of Treg cells in the peripheral blood mononuclear cells of participants remarkably up-regulated, while the level of CD8 + T cells was decreased following the infusion of BM-MSCs which enhanced PBC. Their observation indicated that the levels of IL-10 were also increased, while no therapy-related side effects were reported.

To date, there were no clinical study to assess the effect of MSCs on another AILDs such as AIH and PSC.

Conclusion and outlook

In recent years, MSCs have indicted notable implications in clinical trials and treatments of various autoimmune diseases because of their beneficial properties such as safe and easy obtaining procedure, high proliferation ability and multipotent differentiation capacity as well as anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties, and regenerative potential. In addition to this, their low tumorigenic effects along with poor immunogenicity make these cells as an emerging option in clinical treatment of various disorders and regeneration therapy. According to the clinical trials explained in our review, the repeated administration of MSCs have more effects in comparison with a single infusion. The MSCs were applied intravenously in most of the studies and the injection dosage was mainly between 1 × 106 and 1 × 108 cells/kg.

Furthermore, no remarkable association was found between the MSCT and occurrence of tumor and infection. However, there is still a lack understanding of the mechanisms through which the MSCT ameliorate the various autoimmune diseases which can facilitate the MSC modification and enhance their future clinical use.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- AILD

Autoimmune liver disease

- AIH

Autoimmune hepatitis

- ALT

Alanine aminotransferase

- AST

Aspartate aminotransferase

- ALP

Alkaline phosphatase

- GGT

Gamma-glutamyl transferase

- ANA

Antinuclear antibody

- ADSVF

Adipose-derived stromal vascular fraction

- ASCs

Adipose tissue-derived stromal/stem cells

- AD-MSCs

Adipose-derived-mesenchymal stem cells

- Anti-CCP

Anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide

- APRIL

A proliferation-inducing ligand

- BAFF

B-cell activating factor

- BM

Bone marrow

- BILAG

British Isles Lupus Assessment Group

- BM-HSC

Bone marrow-derived hematopoietic stem cell

- Bregs

Regulatory B cells

- CD

Crohn’s disease

- CNS

Central nervous system

- CXCL12

C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- CCL2

C-C motif chemokine ligand 2

- CDAI

Crohn’s disease activity index

- CDEIS

Crohn’s disease endoscopic index of severity

- CXCR4

C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4

- DsDNA

Anti-double-stranded DNA antibody

- DMARDs

Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs

- EDSS

Expanded Disability Status Scale

- FOXP3

Forkhead box P3

- HbA1C

Glycosylated hemoglobin

- HBI

Harvey–Bradshaw index

- HGF

Hepatocyte growth factor

- HLA

Human leukocyte antigen

- IBD

Inflammatory bowel disease

- IDO

Indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase

- IL-10

Interleukin-10

- IFN-γ

Interferon-γ

- IV

Intravenous

- IT

Intrathecal

- IS-AD-MSC

Autologous insulin-secreting adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells

- ISCT

International Society of Cellular Therapy

- LogMAR

Log of minimum angle of resolution

- MSCs

Mesenchymal stem cells

- MNCs

Mononuclear cell MNCs

- MS

Multiple sclerosis

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- MTX

Methotrexate

- NPs

Neural progenitors

- NSAIDs

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- PBC

Primary biliary cholangitis

- PSC

Primary sclerosing cholangitis

- PBMCs

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- RA

Rheumatoid arthritis

- SAARDs

Slow-acting anti-rheumatic drugs

- sHLA-G

Soluble human leukocyte antigen-G

- SLE

Systemic lupus erythematosus

- SLEDAI

Systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity index

- SS

Sjogren’s syndrome

- SSDAI

Sjogren’s syndrome disease activity index

- SDF-1

Stromal cell-derived factor-1

- TNF-α

Tumor necrosis factor α

- Th17

T helper 17

- T1DM

Type 1 diabetes mellitus

- T25FW

Timed 25-foot walk

- Treg

Regulatory T cells

- UC

Umbilical cord

- UC

Ulcerative colitis

- WJ

Wharton’s jelly

Authors' contributions

S.A.J. and A.V.Y. performed and wrote the manuscript; W.K.A., R.M., and A.M. collected the references, designed the table and figures; W.S. and B.P. modified the manuscript; and L.T. and S.H.A. designed the manuscript and approved the final manuscript for publication. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Fugger L, Jensen LT, Rossjohn J. Challenges, progress, and prospects of developing therapies to treat autoimmune diseases. Cell. 2020;181(1):63–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ghorbani F, et al. Biosensors and nanobiosensors for rapid detection of autoimmune diseases: a review. Microchim Acta. 2019;186(12):838. doi: 10.1007/s00604-019-3844-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forbes GM, et al. A phase 2 study of allogeneic mesenchymal stromal cells for luminal Crohn's disease refractory to biologic therapy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(1):64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sinha AA, Lopez MT, McDevitt HO. Autoimmune diseases: the failure of self tolerance. Science. 1990;248(4961):1380–1388. doi: 10.1126/science.1972595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang X, et al. Immunosensors for biomarker detection in autoimmune diseases. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 2017;65(2):111–121. doi: 10.1007/s00005-016-0419-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahmadi M, et al. Epigenetic modifications and epigenetic based medication implementations of autoimmune diseases. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;87:596–608. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.12.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zharkova O, et al. Pathways leading to an immunological disease: systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2017;56(suppl_1):i55–i66. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kew427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Good RA, Verjee T. Historical and current perspectives on bone marrow transplantation for prevention and treatment of immunodeficiencies and autoimmunities. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2001;7(3):123–135. doi: 10.1053/bbmt.2001.v7.pm11302546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krivit W, Peters C, Shapiro EG. Bone marrow transplantation as effective treatment of central nervous system disease in globoid cell leukodystrophy, metachromatic leukodystrophy, adrenoleukodystrophy, mannosidosis, fucosidosis, aspartylglucosaminuria, Hurler, Maroteaux-Lamy, and Sly syndromes, and Gaucher disease type III. Curr Opin Neurol. 1999;12(2):167–176. doi: 10.1097/00019052-199904000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swart JF, et al. Haematopoietic stem cell transplantation for autoimmune diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2017;13(4):244–256. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2017.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Műzes G, Sipos F. Issues and opportunities of stem cell therapy in autoimmune diseases. World J Stem Cells. 2019;11(4):212–221. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v11.i4.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rezabakhsh A, Sokullu E, Rahbarghazi R. Applications, challenges and prospects of mesenchymal stem cell exosomes in regenerative medicine. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2021;12(1):521. doi: 10.1186/s13287-021-02596-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ullah I, Subbarao RB, Rho GJ. Human mesenchymal stem cells—current trends and future prospective. Biosci Rep. 2015;35(2):e00191. doi: 10.1042/BSR20150025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zakrzewski W, et al. Stem cells: past, present, and future. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10(1):68. doi: 10.1186/s13287-019-1165-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abbaszadeh H, et al. Regenerative potential of Wharton's jelly-derived mesenchymal stem cells: a new horizon of stem cell therapy. J Cell Physiol. 2020;235(12):9230–9240. doi: 10.1002/jcp.29810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mirershadi F, et al. Unraveling the therapeutic effects of mesenchymal stem cells in asthma. Stem Cells Res Ther. 2020;11(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s13287-020-01921-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Y, et al. Clinical application of mesenchymal stem cells in rheumatic diseases. Stem Cells Res Ther. 2021;12(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s13287-021-02635-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cuerquis J, et al. Human mesenchymal stromal cells transiently increase cytokine production by activated T cells before suppressing T-cell proliferation: effect of interferon-γ and tumor necrosis factor-α stimulation. Cytotherapy. 2014;16(2):191–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2013.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giacomelli C, et al. Negative effects of a high tumour necrosis factor-α concentration on human gingival mesenchymal stem cell trophism: the use of natural compounds as modulatory agents. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2018;9(1):135. doi: 10.1186/s13287-018-0880-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ding D-C, Shyu W-C, Lin S-Z. Mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Transplant. 2011;20(1):5–14. doi: 10.3727/096368910X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Friedenstein AJ, Piatetzky S, II, Petrakova KV. Osteogenesis in transplants of bone marrow cells. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1966;16(3):381–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oswald J, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells can be differentiated into endothelial cells in vitro. Stem Cells. 2004;22(3):377–384. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.22-3-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Toma C, et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells differentiate to a cardiomyocyte phenotype in the adult murine heart. Circulation. 2002;105(1):93–98. doi: 10.1161/hc0102.101442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pittenger MF, et al. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science. 1999;284(5411):143–147. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5411.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dominici M, et al. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 2006;8(4):315–317. doi: 10.1080/14653240600855905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chamberlain G, et al. Concise review: mesenchymal stem cells: their phenotype, differentiation capacity, immunological features, and potential for homing. Stem Cells. 2007;25(11):2739–2749. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sotiropoulou PA, et al. Interactions between human mesenchymal stem cells and natural killer cells. Stem Cells. 2006;24(1):74–85. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abbaszadeh H, et al. The effect of Acellularized Wharton's Jelly-derived exosomes on myeloid differentiation of umbilical cord blood-derived CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells. Gene Rep. 2021;25:101298. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang M, Yuan Q, Xie L. Mesenchymal stem cell-based immunomodulation: properties and clinical application. Stem Cells Int. 2018;2018:3057624–3057624. doi: 10.1155/2018/3057624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murphy MB, Moncivais K, Caplan AI. Mesenchymal stem cells: environmentally responsive therapeutics for regenerative medicine. Exp Mol Med. 2013;45(11):e54–e54. doi: 10.1038/emm.2013.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Najar M, et al. Mesenchymal stromal cell immunology for efficient and safe treatment of osteoarthritis. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020;8:567813–567813. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.567813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim HK, et al. A subset of paracrine factors as efficient biomarkers for predicting vascular regenerative efficacy of mesenchymal stromal/stem cells. Stem Cells. 2019;37(1):77–88. doi: 10.1002/stem.2920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abbaszadeh H, et al. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles: a novel therapeutic paradigm. J Cell Physiol. 2020;235(2):706–717. doi: 10.1002/jcp.29004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oh EJ, et al. In vivo migration of mesenchymal stem cells to burn injury sites and their therapeutic effects in a living mouse model. J Control Release. 2018;279:79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2018.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fu X, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell migration and tissue repair. Cells. 2019;8(8):784. doi: 10.3390/cells8080784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang B, et al. Myocardial transfection of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α and co-transplantation of mesenchymal stem cells enhance cardiac repair in rats with experimental myocardial infarction. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2014;5(1):22. doi: 10.1186/scrt410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee H-J, et al. Chronic inflammation-induced senescence impairs immunomodulatory properties of synovial fluid mesenchymal stem cells in rheumatoid arthritis. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2021;12(1):502. doi: 10.1186/s13287-021-02453-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tang C-H. Research of pathogenesis and novel therapeutics in arthritis. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burggraaf B, et al. Effect of a treat-to-target intervention of cardiovascular risk factors on subclinical and clinical atherosclerosis in rheumatoid arthritis: a randomised clinical trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78(3):335–341. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mianehsaz E, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes: a new therapeutic approach to osteoarthritis? Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10(1):340. doi: 10.1186/s13287-019-1445-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim J, et al. Recapitulation of methotrexate hepatotoxicity with induced pluripotent stem cell-derived hepatocytes from patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2018;9(1):357. doi: 10.1186/s13287-018-1100-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aithal GP. Hepatotoxicity related to antirheumatic drugs. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011;7(3):139–150. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aggarwal S, Pittenger MF. Human mesenchymal stem cells modulate allogeneic immune cell responses. Blood. 2005;105(4):1815–1822. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wei Z, et al. Regulatory effect of mesenchymal stem cells on T cell phenotypes in autoimmune diseases. Stem Cells Int. 2021;2021:5583994. doi: 10.1155/2021/5583994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ghoryani M, et al. Amelioration of clinical symptoms of patients with refractory rheumatoid arthritis following treatment with autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells: a successful clinical trial in Iran. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;109:1834–1840. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.11.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Álvaro-Gracia JM, et al. Intravenous administration of expanded allogeneic adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells in refractory rheumatoid arthritis (Cx611): results of a multicentre, dose escalation, randomised, single-blind, placebo-controlled phase Ib/IIa clinical trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(1):196–202. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.He X, et al. Combination of human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem (stromal) cell transplantation with IFN-γ treatment synergistically improves the clinical outcomes of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79(10):1298–1304. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang Y, et al. Serum IFN-γ levels predict the therapeutic effect of mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in active rheumatoid arthritis. J Transl Med. 2018;16(1):165. doi: 10.1186/s12967-018-1541-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang L, et al. Efficacy and Safety of umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell therapy for rheumatoid arthritis patients: a prospective phase I/II study. Drug Des Dev Ther. 2019;13:4331–4340. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S225613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gowhari Shabgah A, et al. A significant decrease of BAFF, APRIL, and BAFF receptors following mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in patients with refractory rheumatoid arthritis. Gene. 2020;732:144336. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2020.144336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang L, et al. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell therapy for patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: safety and efficacy. Stem Cells Dev. 2013;22(24):3192–3202. doi: 10.1089/scd.2013.0023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Park EH, et al. Intravenous infusion of umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells in rheumatoid arthritis: a phase Ia clinical trial. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2018;7(9):636–642. doi: 10.1002/sctm.18-0031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ghoryani M, et al. The sufficient immunoregulatory effect of autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell transplantation on regulatory T cells in patients with refractory rheumatoid arthritis. J Immunol Res. 2020;2020:3562753. doi: 10.1155/2020/3562753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ye L, et al. Immune response after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2017;8(1):90. doi: 10.1186/s13287-017-0542-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lu J, et al. One repeated transplantation of allogeneic umbilical cord mesenchymal stromal cells in type 1 diabetes: an open parallel controlled clinical study. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2021;12(1):340. doi: 10.1186/s13287-021-02417-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dantas JR, et al. Adipose tissue-derived stromal/stem cells + cholecalciferol: a pilot study in recent-onset type 1 diabetes patients. Arch Endocrinol Metab. 2021;65(3):342–351. doi: 10.20945/2359-3997000000368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Araujo DB, et al. Allogenic adipose tissue-derived stromal/stem cells and vitamin D supplementation in patients with recent-onset type 1 diabetes mellitus: a 3-month follow-up pilot study. Front Immunol. 2020;11:993. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cai J, et al. Umbilical cord mesenchymal stromal cell with autologous bone marrow cell transplantation in established type 1 diabetes: a pilot randomized controlled open-label clinical study to assess safety and impact on insulin secretion. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(1):149–157. doi: 10.2337/dc15-0171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Carlsson P-O, et al. Preserved β-cell function in type 1 diabetes by mesenchymal stromal cells. Diabetes. 2015;64(2):587–592. doi: 10.2337/db14-0656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thakkar UG, et al. Insulin-secreting adipose-derived mesenchymal stromal cells with bone marrow-derived hematopoietic stem cells from autologous and allogenic sources for type 1 diabetes mellitus. Cytotherapy. 2015;17(7):940–947. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2015.03.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hu J, et al. Long term effects of the implantation of Wharton's jelly-derived mesenchymal stem cells from the umbilical cord for newly-onset type 1 diabetes mellitus. Endocr J. 2013;60(3):347–357. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.ej12-0343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brown C, et al. Neural stem cells derived from primitive mesenchymal stem cells reversed disease symptoms and promoted neurogenesis in an experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis mouse model of multiple sclerosis. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2021;12(1):499. doi: 10.1186/s13287-021-02563-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bakhuraysah MM, Siatskas C, Petratos S. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for multiple sclerosis: is it a clinical reality? Stem Cell Res Ther. 2016;7(1):12. doi: 10.1186/s13287-015-0272-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Petrou P, et al. Beneficial effects of autologous mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in active progressive multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2020;143(12):3574–3588. doi: 10.1093/brain/awaa333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Riordan NH, et al. Clinical feasibility of umbilical cord tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells in the treatment of multiple sclerosis. J Transl Med. 2018;16(1):57. doi: 10.1186/s12967-018-1433-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Harris VK, et al. Phase I trial of intrathecal mesenchymal stem cell-derived neural progenitors in progressive multiple sclerosis. EBioMedicine. 2018;29:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Harris VK, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived neural progenitors in progressive MS: two-year follow-up of a phase I study. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2021;8(1):e928. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Connick P, et al. The mesenchymal stem cells in multiple sclerosis (MSCIMS) trial protocol and baseline cohort characteristics: an open-label pre-test: post-test study with blinded outcome assessments. Trials. 2011;12:62. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-12-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Connick P, et al. Autologous mesenchymal stem cells for the treatment of secondary progressive multiple sclerosis: an open-label phase 2a proof-of-concept study. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11(2):150–156. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70305-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Karussis D, et al. Safety and immunological effects of mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in patients with multiple sclerosis and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 2010;67(10):1187–1194. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fernández O, et al. Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (AdMSC) for the treatment of secondary-progressive multiple sclerosis: A triple blinded, placebo controlled, randomized phase I/II safety and feasibility study. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(5):e0195891. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0195891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dahbour S, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells and conditioned media in the treatment of multiple sclerosis patients: clinical, ophthalmological and radiological assessments of safety and efficacy. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2017;23(11):866–874. doi: 10.1111/cns.12759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lublin FD, et al. Human placenta-derived cells (PDA-001) for the treatment of adults with multiple sclerosis: a randomized, placebo-controlled, multiple-dose study. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2014;3(6):696–704. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhou T, et al. Efficacy of mesenchymal stem cells in animal models of lupus nephritis: a meta-analysis. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2020;11(1):48. doi: 10.1186/s13287-019-1538-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chun W, Tian J, Zhang Y. Transplantation of mesenchymal stem cells ameliorates systemic lupus erythematosus and upregulates B10 cells through TGF-β1. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2021;12(1):512. doi: 10.1186/s13287-021-02586-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Deng D, et al. A randomised double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of allogeneic umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cell for lupus nephritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(8):1436–1439. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Li X, et al. Mesenchymal SCT ameliorates refractory cytopenia in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48(4):544–550. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2012.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chen C, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells upregulate Treg cells via sHLA-G in SLE patients. Int Immunopharmacol. 2017;44:234–241. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2017.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Castro-Manrreza ME, Montesinos JJ. Immunoregulation by mesenchymal stem cells: biological aspects and clinical applications. J Immunol Res. 2015;2015:394917–394917. doi: 10.1155/2015/394917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wang D, et al. Umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in active and refractory systemic lupus erythematosus: a multicenter clinical study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2014;16(2):R79. doi: 10.1186/ar4520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sun L, et al. Umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in severe and refractory systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(8):2467–2475. doi: 10.1002/art.27548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wang D, et al. A CD8 T cell/indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase axis is required for mesenchymal stem cell suppression of human systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(8):2234–2245. doi: 10.1002/art.38674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wang D, et al. Long-term safety of umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells transplantation for systemic lupus erythematosus: a 6-year follow-up study. Clin Exp Med. 2017;17(3):333–340. doi: 10.1007/s10238-016-0427-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yang S, et al. A novel therapeutic approach for inflammatory bowel disease by exosomes derived from human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells to repair intestinal barrier via TSG-6. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2021;12(1):315. doi: 10.1186/s13287-021-02404-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yabana T, et al. Enhancing epithelial engraftment of rat mesenchymal stem cells restores epithelial barrier integrity. J Pathol. 2009;218(3):350–359. doi: 10.1002/path.2535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Panés J, et al. Expanded allogeneic adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (Cx601) for complex perianal fistulas in Crohn's disease: a phase 3 randomised, double-blind controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;388(10051):1281–1290. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31203-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Philandrianos C, et al. First clinical case report of local microinjection of autologous fat and adipose-derived stromal vascular fraction for perianal fistula in Crohn's disease. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2018;9(1):4. doi: 10.1186/s13287-017-0736-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zhang J, et al. Umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell treatment for Crohn's disease: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Gut Liver. 2018;12(1):73–78. doi: 10.5009/gnl17035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Barnhoorn MC, et al. Long-term evaluation of allogeneic bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cell therapy for Crohn's disease perianal fistulas. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14(1):64–70. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Molendijk I, et al. Allogeneic bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells promote healing of refractory perianal fistulas in patients with Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(4):918–27.e6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Li B, et al. Labial gland-derived mesenchymal stem cells and their exosomes ameliorate murine Sjögren's syndrome by modulating the balance of Treg and Th17 cells. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2021;12(1):478. doi: 10.1186/s13287-021-02541-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Fox RI. Sjögren's syndrome. The Lancet. 2005;366(9482):321–331. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66990-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Xu J, et al. Allogeneic mesenchymal stem cell treatment alleviates experimental and clinical Sjögren syndrome. Blood. 2012;120(15):3142–3151. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-11-391144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Doherty DG. Immunity, tolerance and autoimmunity in the liver: a comprehensive review. J Autoimmun. 2016;66:60–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2015.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.He C, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-based treatment in autoimmune liver diseases: underlying roles, advantages and challenges. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2021;12:2040622321993442. doi: 10.1177/2040622321993442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wang L, et al. Pilot study of umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cell transfusion in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28(Suppl 1):85–92. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wang L, et al. Allogeneic bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in patients with UDCA-resistant primary biliary cirrhosis. Stem Cells Dev. 2014;23(20):2482–2489. doi: 10.1089/scd.2013.0500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Shadmanfar S, et al. Intra-articular knee implantation of autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells in rheumatoid arthritis patients with knee involvement: results of a randomized, triple-blind, placebo-controlled phase 1/2 clinical trial. Cytotherapy. 2018;20(4):499–506. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2017.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Qi T, et al. Cervus and cucumis peptides combined umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;99(28):e21222. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000021222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Dave S, et al. Novel therapy for insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: infusion of in vitro-generated insulin-secreting cells. Clin Exp Med. 2015;15(1):41–45. doi: 10.1007/s10238-013-0266-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Vanikar AV, et al. Cotransplantation of adipose tissue-derived insulin-secreting mesenchymal stem cells and hematopoietic stem cells: a novel therapy for insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Stem Cells Int. 2010;2010:582382–582382. doi: 10.4061/2010/582382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Mohyeddin Bonab M, et al. Does mesenchymal stem cell therapy help multiple sclerosis patients? Report of a pilot study. Iran J Immunol. 2007;4(1):50–57. doi: 10.22034/iji.2007.17180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Yamout B, et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in patients with multiple sclerosis: a pilot study. J Neuroimmunol. 2010;227(1–2):185–189. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2010.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bonab MM, et al. Autologous mesenchymal stem cell therapy in progressive multiple sclerosis: an open label study. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2012;7(6):407–414. doi: 10.2174/157488812804484648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Li JF, et al. The potential of human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells as a novel cellular therapy for multiple sclerosis. Cell Transplant. 2014;23(Suppl 1):S113–S122. doi: 10.3727/096368914X685005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Wang D, et al. Double allogenic mesenchymal stem cells transplantations could not enhance therapeutic effect compared with single transplantation in systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Dev Immunol. 2012;2012:273291. doi: 10.1155/2012/273291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Liang J, et al. Allogenic mesenchymal stem cells transplantation in refractory systemic lupus erythematosus: a pilot clinical study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(8):1423–1429. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.123463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Sun L, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell transplantation reverses multiorgan dysfunction in systemic lupus erythematosus mice and humans. Stem Cells. 2009;27(6):1421–1432. doi: 10.1002/stem.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Liang J, et al. Safety analysis in patients with autoimmune disease receiving allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells infusion: a long-term retrospective study. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2018;9(1):312. doi: 10.1186/s13287-018-1053-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Gu F, et al. Allogeneic mesenchymal stem cell transplantation for lupus nephritis patients refractory to conventional therapy. Clin Rheumatol. 2014;33(11):1611–1619. doi: 10.1007/s10067-014-2754-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Wang D, et al. Allogeneic mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in severe and refractory systemic lupus erythematosus: 4 years of experience. Cell Transplant. 2013;22(12):2267–2277. doi: 10.3727/096368911X582769c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.García-Olmo D, et al. A phase I clinical trial of the treatment of Crohn's fistula by adipose mesenchymal stem cell transplantation. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48(7):1416–1423. doi: 10.1007/s10350-005-0052-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Lightner AL, et al. Matrix-delivered autologous mesenchymal stem cell therapy for refractory rectovaginal Crohn's fistulas. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020;26(5):670–677. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izz215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.de la Portilla F, et al. Expanded allogeneic adipose-derived stem cells (eASCs) for the treatment of complex perianal fistula in Crohn's disease: results from a multicenter phase I/IIa clinical trial. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2013;28(3):313–323. doi: 10.1007/s00384-012-1581-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Dhere T, et al. The safety of autologous and metabolically fit bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells in medically refractory Crohn's disease - a phase 1 trial with three doses. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44(5):471–481. doi: 10.1111/apt.13717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Duijvestein M, et al. Autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cell treatment for refractory luminal Crohn's disease: results of a phase I study. Gut. 2010;59(12):1662–1669. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.215152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Knyazev OV, et al. Cell therapy of refractory Crohn's disease. Bull Exp Biol Med. 2013;156(1):139–145. doi: 10.1007/s10517-013-2297-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.