1. Introduction

Since the 1990s, 25 states plus the District of Columbia have passed medical, recreational, and/or decriminalization laws for cannabis (hereafter referred to as “cannabis policies”; Pacula et al., 2015; Smart & Pacula, 2019; Veligati et al., 2020). Medical cannabis laws legalize the prescription use of the cannabis plant or its derivatives (National Institute on Drug Abuse [NIDA], 2014), while recreational laws allow them to be sold and used without a prescription. Decriminalization refers to the reclassification of low-level cannabis offenses (e.g., the possession of small amounts of the substance) from criminal to civil offenses regardless of offender status (Grucza et al., 2018). All cannabis policies in the US are enacted at the state level and continue to evolve. More states will likely decriminalize or legalize cannabis in the coming years. Most extant literature has examined the impact of cannabis policies on the prevalence of cannabis use (Compton et al., 2017; Maxwell & Mendelson, 2016), subsequent emergency department visits (Maxwell & Mendelson, 2016; Shen et al., 2019), risk perception (Carliner et al., 2017; Compton et al., 2016), and treatment admission rates (Freeman et al., 2018; Meinhofer et al., 2019). To our knowledge, no studies have examined the effect of these policies on treatment outcomes such as discharge variables. Examining these variables is important because they show whether individuals who entered treatment primarily for cannabis use completed their treatment. The current study examines the effect of cannabis policies and referral source on outpatient treatment completion and length of stay among US adults whose primary drug at treatment admission was cannabis.

Cannabis continues to be a commonly used illicit drug in the US, with nearly 10% of adults using it in the past month and 15.3% using it in the past year (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2018). Thirteen percent of individuals who receive substance use treatment report cannabis as their primary drug; these patients tend to be in their twenties, with the average age of admission being 27 years old (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2019). Despite initial concerns, cannabis policies do not appear to have increased the prevalence of use among adolescents under 18 years old (Anderson et al., 2015; Choo et al., 2014; Marzell et al., 2017). However, several reports note an increase in adult (age 18+) usage, which may subsequently increase treatment admission and treatment length among US adults (Cerdá et al., 2019; Compton et al., 2017; Maxwell & Mendelson, 2016). Thus, examining the effect of cannabis policies on adults’ treatment outcomes is important for public health and clinical fields alike.

1.1. Cannabis Treatment Outcomes and Correlates

Two objective measures of treatment outcomes available in the Treatment Episode Data Set - Discharge from 2006-2017 (SAMHSA, 2016, 2018a, 2018b, 2019b) are utilized in the current study: treatment completion and length of stay. Treatment completion indicates whether an individual completed their treatment program or dropped out but does not account for the variety of factors influencing their completion status. Thus, length of stay was added to provide a more nuanced examination of treatment. Most individuals undergoing treatment for alcohol or substance use disorders do not complete treatment (López-Goñi et al., 2014), indicating that length of stay may provide further differentiation beyond treatment completion. In particular, there is evidence that individuals who complete at least 90 days of treatment have lower rates of both recidivism and drug use (NIDA, 2018). Many studies focus on one or the other of these two outcomes; our perspective is that examining the combination of the two may provide more useful information.

A key aspect of studying the effects of cannabis policies on treatment outcomes is the referral source of individuals who seek help. Individuals who enter treatment after being mandated to do so by the justice system (drug court, probation) tend to have higher attendance rates and remain in treatment for longer, possibly due to extrinsic motivation such as legal pressure (NIDA, 2014). Criminal justice referrals typically make up a significant proportion of treatment admissions (Farabee et al., 1998; Howard & McCaughrin, 1996) and remain high for cannabis among individuals across the lifespan (SAMHSA, 2019a). However, the literature is mixed on whether individuals who seek treatment following a criminal justice referral have better treatment completion rates. Results range from no difference in treatment completion (Kiluk et al., 2015) to a nearly 10-fold increase in treatment completion among those with a criminal justice referral compared to those voluntarily referred (Coviello et al., 2013). Some of these differences may be related to demographic variables and treatment settings. For example, one study found that older adults (age 55+) who were legally mandated to attend treatment for any substance use disorder were 71% more likely to complete treatment compared to those who entered voluntarily, with treatment completion for cannabis being 51% higher among those with a criminal justice referral (Pickard et al., 2020). Another study found a moderation effect of treatment setting on the relationship between mandated drug treatment and treatment outcomes; women mandated to outpatient treatment were more likely to complete treatment than non-mandated women, a trend that was enhanced in those with outpatient or inpatient setting but not a detoxification setting (Longinaker & Terplan, 2014). Therefore, the referral source will be considered in the current study.

1.2. The Effect of Cannabis Policies on Treatment Outcomes

Since admission rates affect treatment outcomes, it should be noted that states with cannabis policies tend to have the same or fewer treatment admissions for cannabis use in the general population compared to states with no cannabis policies (Maxwell & Mendelson, 2016; Meinhofer et al., 2019; Kerr et al., 2012; Pacula et al., 2015). For example, there is evidence that cannabis policies reduced treatment admissions for cannabis among the general population by 14% (Pacula et al., 2015). Interestingly, there is a reversed effect whereby admissions for cannabis use among pregnant women is increased by 5% in states with cannabis policies (Meinhofer et al., 2019). Furthermore, states with legal recreational marijuana use policies have lower treatment admissions rates for cannabis use disorder, with a shift to more cannabis-related ER, poison control, and hospital visits (Maxsell & Mendelson, 2016). This shift may reflect the lag between the expansion of recreational marijuana use and the increase in problematic use in these states, often represented by ER visits (Maxwell & Mendleson, 2016). Nevertheless, while the effect of cannabis policies on treatment admissions has been frequently studied (Compton et al., 2017; Freeman et al., 2018; Maxwell & Mendelson, 2016; Meinhofer et al., 2019), we are unaware of any studies that examine the association between cannabis policies, referral source, and treatment outcomes.

1.3. Specific Aims

The current study will fill this significant gap in the literature by exploring differences in treatment outcomes following outpatient treatment for cannabis use among US adults based on policy and referral sources. Accordingly, the first aim is to examine the effect of cannabis policies on treatment completion among those with criminal justice or voluntary referral source. The second aim is to focus on length of stay in outpatient facilities, again examining the effect of cannabis policies on this outcome variable in those with criminal justice or voluntary referral source.

2. Methods

2.1. Sample

Participants were adults age 18+ from the Treatment Episode Data Set - Discharges (TEDS-D) for 2006-2017 (SAMHSA, 2016, 2018a, 2018b, 2019b) whose primary substance used at admission was listed as cannabis and who sought treatment in an outpatient facility (N = 1,863,585). The outpatient setting was chosen to avoid potential confounding related to the shorter-termed, often fixed-length nature of residential or inpatient treatment, and because the majority of cannabis users (>90%) engage in outpatient treatment rather than residential or inpatient treatment (Stahler et al., 2016). Outpatient treatment as defined in the TEDS-D includes those engaged in individual, family, and/or pharmacological treatment on an outpatient basis, including intensive outpatient programs. Service settings such as detoxification, 24-hour residential treatment, or hospitalization were not included in these analyses.

See Table 1 for more details about the sample demographics. Briefly, the sample was 71.17% male, 65.44% non-white, and 33.28% Hispanic or Latinx. The sample was fairly evenly divided between the five age categories (18.93-23.19%) except for those aged 40+ (13.50%). Of note, under half of the participants had a criminal justice referral source (41.34%), while the rest had a voluntary source (58.66%). Most participants stayed in their outpatient treatment for 90 or fewer days (54.37% of the full sample), with slight differences between those with a criminal justice referral (50.96%) versus a voluntary referral (59.30%).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the sample for aim 2 (outcome = length of stay; outpatient only).

| Variable | Full sample | Criminal justice referred | Voluntary referral |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age | |||

| 18-20 | 352,770 (18.93%) | 127,708 (16.81% | 220,588 (20.45%) |

| 21-24 | 432,214 (23.19%) | 159,040 (20.94%) | 267,650 24.82%) |

| 25-29 | 40.68% (21.83%) | 166,719 (21.95%) | 234,591 (21.76%) |

| 30-39 | 420,076 (22.54%) | 185,675 (24.44%) | 228,334 (21.28%) |

| 40+ | 251,659 (13.50%) | 120,533 (15.87%) | 127,006 (11.78%) |

|

| |||

| Sex | |||

| Male | 1,326,054 (71.17%) | 4,421,112 (58,21%) | 867,465 (80.47%) |

| Female | 537,045 (28.83%) | 317,395 (41.769%) | 210,524 (19.53%) |

|

| |||

| Race | |||

| White | 637,981 (34.66%) | 246,849 (32.91%) | 383,658 (36.01%) |

| Black | 959,419 (52.13%) | 406,421 (54.18%) | 538,035 (50.50%) |

| Another | 243,126 (13.21%) | 96,855 (12.91%) | 43,685 (13.49%) |

|

| |||

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic | 1,237,362 (67.28%) | 492,401 (65.75%) | 728,184 (68.34%) |

| Not Hispanic | 601,707 (32.72%) | 256,445 (34.25%) | 337,393 (31.66%) |

|

| |||

| Education | |||

| Less than High School | 707,671 (38.65%) | 290,534 (38.99%) | 408,209 (38.46%) |

| High School or GED | 817,828 (44.67%) | 318,148 (42.69%) | 489,117 (46.08%) |

| More than High School | 305,243 (30.52%) | 136,499 (18.32%) | 164,074 (15.46%) |

|

| |||

| Referral Source | |||

| Criminal justice | 759,675 (41.34%) | -- | -- |

| Voluntary (self, provider, work) | 1,078,169 (58.66%) | -- | -- |

|

| |||

| Dual Psychiatric Diagnosis | |||

| Yes | 1,102,756 (71.37%) | 388,584 (61.54%) | 705,553 (78.47%) |

| No | 442,266 (28.63%) | 242,818 (38.46%) | 193,628 (21.53%) |

|

| |||

| Prior Treatment Episodes | |||

| Yes | 920346 (51.99%) | 383417 (52.98%) | 523749 (51.11%) |

| No | 849925 (48.01%) | 340331 (47.02%) | 500925 (48.89%) |

|

| |||

| Length of stay < 90 days | 1,013,182 (54.37%) | 549,480 (50.96%) | 450,516 (59.30%) |

2.2. Measures

Outcome measures data were from the TEDS-D for 2006-2017. The TEDS-D contains de-identified annual treatment-related data for all treatment episodes reported to the federal Behavioral Health Services Information System office by publicly-funded facilities across the US other than those managed by the Bureau of Prisons, Veterans Administration, Department of Defense, and some Native American health service (SAMHSA. Key variables of interest included treatment completion (outcome aim 1), length of stay (outcome aim 2), cannabis policy status for each US state (predictor variables in both aims), and referral source (grouping variable in both aims).

Cannabis Policy.

The predictor variables included three binary variables indicating the type of cannabis policy (medical, recreational, decriminalized) for each state from 2006-2017. See Supplemental Table 1 for a breakdown of policies by year. Following the methods of Veligatti and colleagues (2020), we coded “medical” as whether or not a state had adopted a medical cannabis policy. While this approach may not be as nuanced as other approaches that consider the permissiveness of medical policies (Pacula et al., 2015), it was sufficient for our purposes, as we were examining the presence or absence of a general medical policy. Policy statuses for recreational, or commercial, legalization were taken from Smart and Pacula (2019). States were coded as having a decriminalization policy using the designations determined in Grucza and colleagues (2018). For all policy statuses, the state was coded as having the policy if it was implemented for most of the given year (e.g., implementation on or after July 1st was coded as 0, and implementation before July 1st was coded as 1). We updated policy status and cross-checked for implementation for all policy types using the Marijuana Policy Project website (2020) and the Nexis Uni criminal justice database.

Referral Source.

Criminal justice referrals were defined in the TEDS-D as referrals from police officials, court officials, probation or parole officers, and any other person affiliated with a judicial system, including deferred prosecution systems. Other types of referral source (self-referral, clinical or health care provider, education, employer, or other community referrals) were combined and coded as voluntary. Referral source was revealed to be a significant predictor of both main outcomes in preliminary analyses (see Supplemental Tables 4 and 5). Thus, it was utilized as a way to group the sample in both aims.

Covariates.

Several demographic and clinical variables were included in all analyses based on previous literature (see Supplemental Text 1). Demographic covariates included age (18-20, 21-24, 25-29, 30-39, 40+), sex (male, female), race (white, black, other), ethnicity (Hispanic or Latinx, not Hispanic or Latinx), and education (less than high school, high school or GED, more than high school). Clinical covariates included dual psychiatric diagnosis (yes/no) and prior treatment episodes (yes/no).

Treatment Completion.

Treatment completion was derived from the TEDS-D dataset and was recoded as a binary categorical variable (yes / no), with “yes” a combination of “treatment completed” and “transferred to another substance abuse treatment program or facility,” and “no” a combination of “left against professional advice,” “terminated by facility,” “incarcerated,” or “death.” Those coded “other” or “unknown” were not included.

Length of Stay.

Length of stay (LOS) was derived from the TEDS-D dataset and was a measure of the number of consecutive days in treatment initially coded as continuous for 1-30 days and then categorically thereon out (e.g., category 31 represented 31-45 days; category 37 represented days 366+ days). This coding made meaningful interpretation of the length of stay challenging; thus, length of stay was recoded into a binary categorical variable (LOS < 90 days; LOS ≥ 91 days). This decision to recode LOS was supported by research showing that drug intervention programs are most effective when they last at least 90 days in duration (National Institute of Health, 2007) and meta-analysis of 11 studies of outpatient psychosocial cannabis treatment found that the average planned length of outpatient cannabis treatment was just over 90 days (13.6 weeks; Gates et al., 2016). In addition, 90 days was the median LOS in our dataset.

2.3. Analyses

Analyses were performed in the R software package (R Core Development Team, 2015).

Covariates.

The effects of potential covariates were assessed before the primary analyses using multiple logistic regression (see Supplemental Tables 4 and 3). Significant covariates were kept in the primary analyses. Year (categorically coded 0-11 to represent years 2006-2017) and state (categorically coded 1-50 to represent each state alphabetically) were included in all analyses as covariates and were not tested a priori.

Primary Analyses.

A difference-in-difference analysis (Angrist & Pischke, 2009) was performed for each aim via multiple logistic regressions. The outcome variable in each aim was modeled as a function of policy (medical, recreational, decriminalized) while controlling for year and state. State was also used as a clustering variable to control autocorrelation effects (function lm.cluster in package miceadds; Robitzsch & Grund, 2020). For aim 1, treatment completion was the outcome variable, and for aim 2, length of stay was the outcome variable. Both aims were restricted to individuals in an outpatient treatment setting. There were two parts to each aim and analysis. Two analyses were run separately for each referral source group (criminal justice versus voluntary referral) in each aim, with all covariates remaining the same. Since two analyses were run on each outcome variable, Holm’s family-wise error rate was used to adjust the p-values of the effect of the main predictor variables (i.e., policy variables) for each aim (Field et al., 2012; Holm, 1979).

3. Results

3.1. Effects of Policy on Treatment Completion and Length of Stay

There were no policy effects on treatment completion in either those with criminal justice or voluntary referral source (see Table 2). There were only effects of covariates.

Table 2.

Effect of cannabis policy on treatment completion using multiple logistic regression by referral source.

| Predictor | Beta | Standard Error | Odds Ratio [95% Confidence Interval] |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Criminal Justice Referral Source | |||

|

| |||

| Policy | |||

| Medical | −0.06 | 0.095 | 0.94 [0.78 - 1.14] |

| Recreational | 0.32 | 0.202 | 1.38 [0.93 - 2.05] |

| Decriminalized | 0.06 | 0.080 | 1.06 [0.90 - 1.24] |

|

| |||

| Sex | |||

| Female | 0.09** | 0.032 | 1.10 [1.03 - 1.17] |

|

| |||

| Age | |||

| 21-24 | 0.08*** | 0.021 | 1.08 [1.04 - 1.13] |

| 25-29 | 0.17*** | 0.033 | 1.18 [1.11 - 1,26] |

| 30-39 | 0.27*** | 0.041 | 1.31 [1.21 - 1.41] |

| 40+ | 0.42*** | 0.052 | 1.52 [1.37 - 1.68] |

|

| |||

| Race | |||

| Black | 0.31*** | 0.035 | 1.36 [1.27 - 1.46] |

| Another | 0.22*** | 0.029 | 1.24 [1.18 - 1.32] |

|

| |||

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic | −0.01 | 0.023 | 0.99 [0.95 - 1.04] |

|

| |||

| Education | |||

| High School or GED | 0.20*** | 0.009 | 1.23 [1.20 - 1.25] |

| More than High School | 0.43*** | 0.019 | 1.54 [1.50 - 1.60] |

|

| |||

| Dual Psychiatric Diagnosis | |||

| Yes | −0.24*** | 0.036 | 0.79 [0.73 - 0.85] |

|

| |||

| Prior Treatment Episodes | |||

| Yes | −0.16*** | 0.023 | 0.85 [0.81 - 0.89] |

|

| |||

| Voluntary Referral Source | |||

|

| |||

| Policy | |||

| Medical | −0.09 | 0.091 | 0.92 [0.77 - 1.10] |

| Recreational | 0.16 | 0.089 | 1.18 [0.99 - 1.40] |

| Decriminalized | 0.15 | 0.097 | 1.16 [0.96 - 1.40] |

|

| |||

| Sex | |||

| Female | 0.02 | 0.035 | 1.02 [0.95 - 1.09] |

|

| |||

| Age | |||

| 21-24 | 0.11*** | 0.021 | 1.11 [1.06 - 1.16] |

| 25-29 | 0.18*** | 0.022 | 1.19 [1.14 - 1.25] |

| 30-39 | 0.24*** | 0.030 | 1.27 [1.19 - 1.34] |

| 40+ | 0.35*** | 0.034 | 1.43 [1.33 - 1.52] |

|

| |||

| Race | |||

| Black | 0.23*** | 0.062 | 1.27 [1.12 - 1.43] |

| Another | 0.14** | 0.045 | 1.15 [1.05 - 1.25] |

|

| |||

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic | −0.06 | 0.043 | 0.95 [0.87 - 1.03] |

|

| |||

| Education | |||

| High School or GED | 0.16*** | 0.022 | 1.17 [1.12 - 1.22] |

| More than High School | 0.27*** | 0.047 | 1.30 [1.19 - 1.43] |

|

| |||

| Dual Psychiatric Diagnosis | |||

| Yes | −0.35*** | 0.041 | 0.71 [0.65 - 0.77] |

|

| |||

| Prior Treatment Episodes | |||

| Yes | −0.07 | 0.033 | 0.94 [0.88 - 1.00] |

Notes: References are as follows - policy (no policy of that type); age (18-20); sex (male); race (white); ethnicity (not Hispanic); education (less than high school); dual psychiatric diagnosis (no); prior treatment (no).

State and year are not represented in the table for the sake of space.

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001

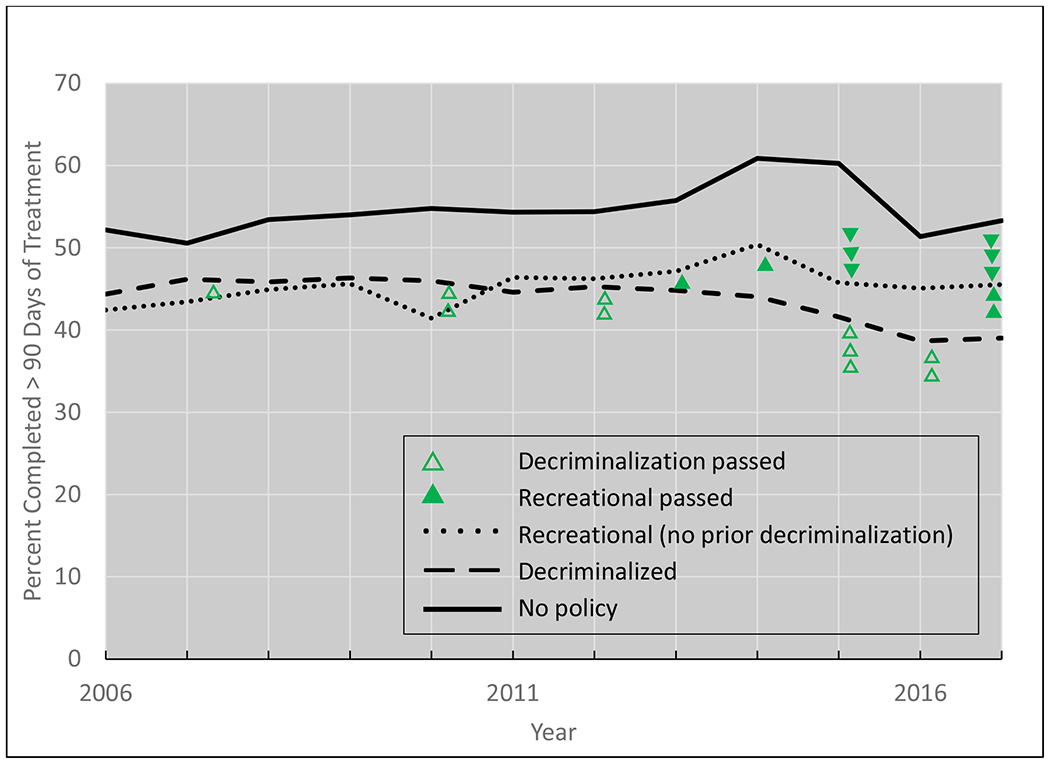

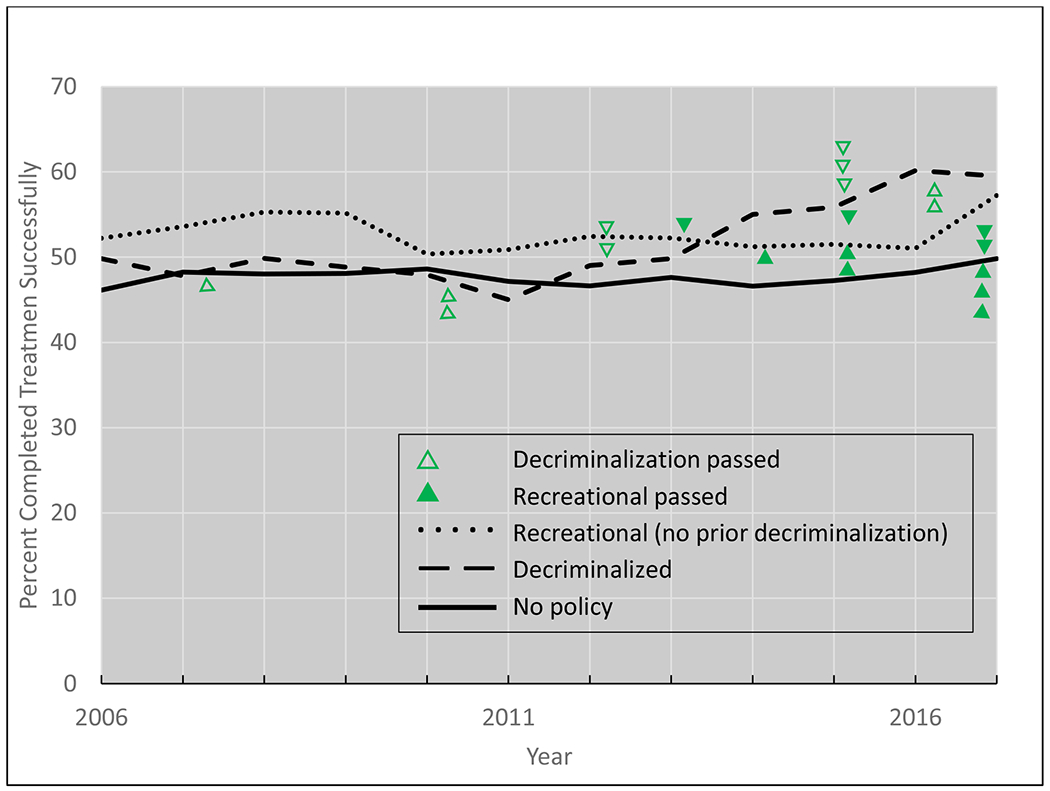

There were similar policy effects on length of stay found for those with a criminal justice referral source compared to those with a voluntary referral source (see Table 3). Among those with a criminal justice referral source, there were effects of decriminalization policies on length of stay and the effects of covariates. Compared to individuals in states without these policies, individuals with a criminal justice referral source in states with a decriminalization policy were 38% less likely to have a 91+ day length of stay. Among those with a voluntary referral source, there was also an effect of decriminalization policies and covariates. Individuals with a voluntary referral source in states with a decriminalization policy were about 20% less likely to have a length of stay 91+ day length of stay compared to those in states without these policies. See Table 4 for a condensed summary of findings across aims. As seen in the figures, there was a gradual decline in length of stay for states with decriminalization policies beginning around the first periods when decriminalization was adopted (open triangles, Figure 1), with no changes for states with recreational or no cannabis policies. There were no clear trends in treatment completion that could be seen in Figure 2.

Table 3.

Effect of cannabis policy on length of stay using multiple logistic regression by referral source.

| Predictor | Beta | Standard Error | Odds Ratio (Confidence Interval) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Criminal Justice Referral Source | |||

|

| |||

| Policy | |||

| Medical | −0.22 | 0.106 | 0.80 [0.65 - 0.98] |

| Recreational | 0.14 | 0.102 | 1.14 [0.94 - 1.40] |

| Decriminalized | −0.47** | 0.115 | 0.62 [0.50 - 0.78] |

|

| |||

| Sex | |||

| Female | 0.06 | 0.018 | 1.06 [1.02 - 1.10] |

|

| |||

| Age | |||

| 21-24 | 0.09*** | 0.013 | 1.10 [1.07 - 1.13] |

| 25-29 | 0.14*** | 0.022 | 1.15 [1.10 - 1.20] |

| 30-39 | 0.18*** | 0.039 | 1.19 [1.11 - 1.29] |

| 40+ | 0.24*** | 0.047 | 1.28 [1.16 - 1.40] |

|

| |||

| Race | |||

| Black | 0.18*** | 0.035 | 1.20 [1.12 - 1.28] |

| Another | 0.12** | 0.043 | 1.13 [1.04 - 1.23] |

|

| |||

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic | 0.00 | 0.021 | 1.00 [0.96 - 1.04] |

|

| |||

| Education | |||

| High School or GED | 0.09*** | 0.025 | 1.09 [1.04 - 1.14] |

| More than High School | 0.14** | 0.046 | 1.14 [1.05 - 1.25] |

|

| |||

| Dual Psychiatric Diagnosis | |||

| Yes | −0.10** | 0.032 | 0.90 [0.84 - 0.96] |

|

| |||

| Prior Treatment Episodes | |||

| Yes | −0.06 | 0.036 | 0.94 [0.88 - 1.01] |

|

| |||

| Not Criminal Justice Referral Source | |||

|

| |||

| Policy | |||

| Medical | −0.02 | 0.070 | 0.98 [0.86 - 1.13] |

| Recreational | 0.11 | 0.106 | 1.12 [0.91 - 1.38] |

| Decriminalized | −0.24*** | 0.068 | 0.78 [0.69 - 0.90] |

|

| |||

| Sex | |||

| Female | 0.08*** | 0.022 | 1.08 [1.03 - 1.13] |

|

| |||

| Age | |||

| 21-24 | 0.12*** | 0.031 | 1.12 [1.06 - 1.20] |

| 25-29 | 0.18*** | 0.038 | 1.20 [1.11 - 1.29] |

| 30-39 | 0.23*** | 0.050 | 1.26 [1.14 - 1.39] |

| 40+ | 0.34*** | 0.053 | 1.40 [1.26 - 1.56] |

|

| |||

| Race | |||

| Black | 0.06 | 0.037 | 1.06 [0.98 - 1.14] |

| Another | 0.05 | 0.035 | 1.05 [0.98 - 1.13] |

|

| |||

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic | 0.00 | 0.021 | 1.00 [0.96 - 1.04] |

|

| |||

| Education | |||

| High School or GED | 0.02 | 0.020 | 1.02 [0.98 - 1.06] |

| More than High School | 0.02 | 0.032 | 1.02 [0.95 - 1.08] |

|

| |||

| Dual Psychiatric Diagnosis | |||

| Yes | −0.03 | 0.057 | 0.97 [0.85 - 0.96] |

|

| |||

| Prior Treatment Episodes | |||

| Yes | −0.01 | 0.018 | 0.99 [0.87 - 1.01] |

Notes: References are as follows - policy (no policy of that type); age (18-20); sex (male); race (white); ethnicity (not Hispanic); education (less than high school); dual psychiatric diagnosis (no); prior treatment (no).

State and year are not represented in the table for the sake of space.

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001

Table 4.

Summary of findings across aims.

| Outcome = Treatment Completion (yes/no) | Result | Outcome = Length of Stay (<90 days / 90+ days) | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Criminal justice referral source | Criminal justice referral source | ||

| Medical policy | NS | Medical policy | NS |

| Recreational policy | NS | Recreational policy | NS |

| Decriminalization policy | NS | Decriminalization policy | Policy decreased the likelihood of a longer LOS |

|

| |||

| Voluntary referral source | Voluntary referral source | ||

| Medical policy | NS | Medical policy | NS |

| Recreational policy | NS | Recreational policy | NS |

| Decriminalization policy | NS | Decriminalization policy | Policy decreased the likelihood of a longer LOS |

Notes. NS = non-significant result; CJ = criminal justice; LOS = length of stay

Figure 1:

Length of stay by 2017 cannabis policy

Note: Triangles indicate states that passed decriminalization (open) or recreational (filled) policy laws. The triangles are oriented up or down to make legibility easier.

Figure 2:

Treatment completion by 2017 cannabis policy

Note: Triangles indicate states that passed decriminalization (open) or recreational (filled) policy laws. The triangles are oriented up or down to make legibility easier.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to determine whether living in a state with a cannabis policy (i.e., decriminalization, legalization of medical cannabis use, recreational cannabis use) and/or referral source (i.e., criminal justice vs. voluntary) affected treatment outcomes (treatment completion or length of stay) for those in an outpatient treatment facility whose primary substance used was cannabis. Our results showed no significant relationships between the states’ cannabis policy and treatment completion in those with either referral source. However, a significant relationship was found between states with a decriminalization policy and treatment length of stay. Specifically, the presence of a decriminalization policy decreased individuals’ likelihood of having a length of stay that was 91 days or more in those with either referral source. These differing findings across treatment outcomes (treatment completion versus length of stay) imply that the effect of cannabis policies on treatment is dependent on how these outcomes are defined, which is consistent with findings of previous studies (Coviello et al., 2013; Kiluk et al., 2015; Longinaker & Terplan, 2014; Pickard et al., 2020).

To our knowledge, the current study was the first to examine the effect of cannabis policies on different aspects of treatment outcomes. Many studies have noted relationships between cannabis policies and admissions for cannabis (Compton et al., 2017; Freeman et al., 2018; Maxwell & Mendelson, 2016; Meinhofer et al., 2019), and our current findings support this literature. The null findings seen in the relationship between cannabis policies and treatment completion are notable and potentially actionable, and they may be due to variability or inaccuracy in how different agencies classify treatment completion. For example, it may not be appropriate for treatment centers and researchers to use a simple “yes, treatment completed” indicator when studying the predictors of that outcome. More effective standardization of substance use treatment outcome documentation may be helpful. However, we also need to consider the possibility that cannabis policies do not affect treatment completion.

Treatment admissions and discharge for substance use disorders are complex phenomena, and it is critical how they are measured. While treatment completion was not impacted by cannabis policies in this study, length of stay was consistently impacted by decriminalization policies across both referral sources. In both instances, the presence of policies decreased individuals’ likelihood of having a length of stay in outpatient treatment of 91+ days. Notably, this study’s incorporation of the binary length of stay variable was important because it allowed for a simple yet powerful insight into treatment outcomes. Past research demonstrate that duration has a significant effect on long-term outcomes, with 90 days being the minimal ideal length across substances (NIDA, 2018). In our sample, slightly more participants had an outpatient length of stay under 91 days compared to 91+ days. Across treatment settings, it was approximately a 50-50 split between who did or did not complete treatment; this does not align with previous literature showing that most individuals with substance use problems do not complete treatment (López-Goñi et al., 2014). This finding implies that length of stay may provide differentiation beyond treatment completion when examining cannabis treatment and policies.

Relatedly, the different effects of medical and decriminalization policies on length of stay among individuals with different referral sources should be examined more deeply in future studies. The current findings indicate that referral source affects the cannabis policy’s impact on treatment length of stay, depending on the specific policy. There are a few possible explanations for this. First, treatment providers in states with decriminalization policies may have more flexibility in determining the length of stay and may consider treatment “complete” at shorter lengths of treatment than those in states that have not decriminalized cannabis. If true, then decriminalization would not necessarily impact completion, but it would impact length of stay because treatment is considered complete at shorter lengths of stay. Second, it could indicate that there are fewer criminal justice referrals to outpatient treatment for cannabis than other referral sources and, therefore, decriminalization policies present a reduction in the inherent motivation that may be associated with higher treatment completion among those with a criminal justice referral (Coviello et al., 2013). Finally, individuals with a criminal justice referral source may be using low amounts of cannabis; therefore, the presence of decriminalization policies would naturally decrease their likelihood of a longer length of stay because their low-dose use was not problematic to begin with.

4.1. Clinical Implications

Our results show that the presence of state-level cannabis policies do not significantly impact treatment completion but that decriminalization policies do decrease the likelihood of the person remaining in treatment for more than 90 days for both those who are self-referred and referred by the criminal justice system. As noted above, this may indicate that clinicians have greater flexibility in determining the length of treatment in states with cannabis policies. However, it also raises the important point that people in treatment continue to seek out and complete treatment for Cannabis Use Disorder regardless of the presence of cannabis policies. In addition, recent studies have shown that people who are mandated to drug treatment have similar outcomes as those who are voluntary (e.g., Pilarinos et al., 2020), and there is growing evidence that coercive treatment is unethical and neurobiologically contraindicated (Hall et al., 2012; Uusitalo & Eijk, 2016). Our findings that the introduction of decriminalization cannabis policies reduce the length of stay for those referred by the criminal justice system may indicate a shift to a less punitive and restrictive model, which may allow for more tailored treatment. This shift may then provide clinicians with more flexibility to provide shorter and more focused treatment to those with less severe problems than previously mandated (Pelan, 2015).

4.2. Limitations

There are significant limitations to effectively studying the impact of cannabis policies on treatment admissions and outcomes. One of these barriers is that there is often a large time lag between cannabis policy change and clinical effects. Furthermore, most states that implemented recreational laws had previous medical cannabis laws that could potentially confound any relationship between newer policies and treatment outcomes (Smart & Pacula, 2019). Finally, while reducing our length of stay outcome into a binary variable was an evidence-based, clinically valid choice (NIDA, 2018), this categorization reduces the information contained within the data (MacCallum et al., 2002). However, this is more a limitation of how the TEDS-D defines the length of stay variable, making it difficult to compare shorter stays to longer stays without categorization.

4.3. Conclusions

The current study sought to examine the effect of cannabis policies (medical, recreational, decriminalization) on treatment outcomes (treatment completion, length of stay) in an outpatient treatment sample that was stratified by referral source (criminal justice, voluntary). There were two key takeaways. First, it might be necessary to use length of stay instead of treatment completion when examining treatment outcomes for cannabis use. Second, across samples, decriminalization policies were associated with a decreased likelihood of a 91+ day length of stay in outpatient treatment facilities among individuals whose primary substance was cannabis in both referral sources. While more work needs to be done to disentangle the nuances of these findings further, they hold potentially actionable clinical and research implications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

This work was conducted as part of a class project in the Master of Population Health Sciences Program, Washington University School of Medicine.

Funding:

This work was partially supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse [grant number T32DA01035 (JLB and MWF)].

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None of the authors have significant conflicts of interest to report.

References

- Anderson DM, Hansen B, & Rees DI (2015). Medical Marijuana Laws and Teen Marijuana Use. American Law and Economics Review, 17(2), 495–528. 10.1093/aler/ahv002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Angrist JD, & Pischke JS (2009). Mostly Harmless Econometrics: An Empiricist’s Companion. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carliner H, Brown QL, Sarvet AL, & Hasin DS (2017). Cannabis use, attitudes, and legal status in the U.S.: A review. Preventive Medicine, 104, 13–23. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.07.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2018). 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2017-nsduh-detailed-tables [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerdá M, Mauro C, Hamilton A, Levy NS, Santaella-Tenorio J, Hasin D, Wall MM, Keyes KM, & Martins SS (2019). Association Between Recreational Marijuana Legalization in the United States and Changes in Marijuana Use and Cannabis Use Disorder From 2008 to 2016. JAMA Psychiatry. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.3254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choo EK, Benz M, Zaller N, Warren O, Rising KL, & McConnell KJ (2014). The Impact of State Medical Marijuana Legislation on Adolescent Marijuana Use. Journal of Adolescent Health, 55(2), 160–166. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, Han B, Jones CM, Blanco C, & Hughes A (2016). Marijuana use and use disorders in adults in the USA, 2002–14: Analysis of annual cross-sectional surveys. The Lancet Psychiatry, 3(10), 954–964. 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30208-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, Volkow ND, & Lopez MF (2017). Medical Marijuana Laws and Cannabis Use: Intersections of Health and Policy. JAMA Psychiatry, 74(6), 559–560. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coviello DM, Zanis DA, Wesnoski SA, Palman N, Gur A, Lynch KG, & McKay JR (2013). Does mandating offenders to treatment improve completion rates? Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 44(4), 417–425. 10.1016/j.jsat.2012.10.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farabee D, Prendergast M, & Anglin MD (1998). The effectiveness of coerced treatment for drug-abusing offenders. Federal Probation, 62(1), 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman TP, van der Pol P, Kuijpers W, Wisselink J, Das RK, Rigter S, van Laar M, Griffiths P, Swift W, Niesink R, & Lynskey MT (2018). Changes in cannabis potency and first-time admissions to drug treatment: A 16-year study in the Netherlands. Psychological Medicine, 48(14), 2346–2352. 10.1017/S0033291717003877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates PJ, Sabioni P, Copeland J, Foll BL, & Gowing L (2016). Psychosocial interventions for cannabis use disorder. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 5. 10.1002/14651858.CD005336.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grucza RA, Vuolo M, Krauss MJ, Plunk AD, Agrawal A, Chaloupka FJ, & Bierut LJ (2018). Cannabis decriminalization: A study of recent policy change in five U.S. states. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 59, 67–75. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.06.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall W, Babor T, Edwards G, Laranjeira R, Marsden J, Miller P, Obot I, Petry N, Thamarangsi T, & West R (2012). Compulsory detention, forced detoxification and enforced labour are not ethically acceptable or effective ways to treat addiction. Addiction, 107(11), 1891–1893. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03888.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard DL, & McCaughrin WC (1996). The Treatment Effectiveness of Outpatient Substance Misuse Treatment Organizations between Court-Mandated and Voluntary Clients. Substance Use & Misuse, 31(7), 895–926. 10.3109/10826089609063962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiluk BD, Serafini K, Malin‐Mayor B, Babuscio TA, Nich C, & Carroll KM (2015). Prompted to treatment by the criminal justice system: Relationships with treatment retention and outcome among cocaine users. The American Journal on Addictions, 24(3), 225–232. 10.1111/ajad.12208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longinaker N, & Terplan M (2014). Effect of criminal justice mandate on drug treatment completion in women. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 40(3), 192–199. 10.3109/00952990.2013.865033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Goñi JJ, Fernández-Montalvo J, Cacho R, & Arteaga A (2014). Profile of Addicted Patients Who Reenter Treatment Programs. Substance Abuse, 35(2), 176–183. 10.1080/08897077.2013.826614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum RC, Zhang S, Preacher KJ, & Rucker DD (2002). On the practice of dichotomization of quantitative variables. Psychological Methods, 7(1), 19–40. 10.1037//1082-989X.7.1.19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marijuana Policy Project. (2020). State Policy. Marijuana Policy Project. https://www.mpp.org/states/ [Google Scholar]

- Marzell M, Sahker E, & Arndt S (2017). Trends of Youth Marijuana Treatment Admissions: Increasing Admissions Contrasted with Decreasing Drug Involvement. Substance Use & Misuse, 52(13), 1778–1783. 10.1080/10826084.2017.1311349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell JC, & Mendelson B (2016). What Do We Know Now About the Impact of the Laws Related to Marijuana? Journal of Addiction Medicine, 10(1), 3–12. 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinhofer A, Witman A, Murphy SM, & Bao Y (2019). Medical marijuana laws are associated with increases in substance use treatment admissions by pregnant women. Addiction, 114(9), 1593–1601. 10.1111/add.14661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2014). Principles of Drug Abuse Treatment for Criminal Justice Populations—A Research-Based Guide. https://www.drugabuse.gov/sites/default/files/txcriminaljustice_0.pdf

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2018). Principles of Drug Addiction Treatment: A Research-Based Guide (NIH Publication No. 12–4180). National Institute on Drug Abuse. https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/principles-drug-addiction-treatment-research-based-guide-third-edition/preface [Google Scholar]

- Pacula RL, Powell D, Heaton P, & Sevigny EL (2015). Assessing the Effects of Medical Marijuana Laws on Marijuana Use: The Devil is in the Details. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 34(1), 7–31. 10.1002/pam.21804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelan M (2015). Re-visioning Drug Use: A Shift Away From Criminal Justice and Abstinence-based Approaches. Social Work & Society, 13(2), Article 2. https://socwork.net/sws/article/view/432 [Google Scholar]

- Pickard JG, Sacco P, Berk-Clark C van den, & Cabrera-Nguyen EP (2020). The effect of legal mandates on substance use disorder treatment completion among older adults. Aging & Mental Health, 24(3), 497–503. 10.1080/13607863.2018.1544209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilarinos A, Barker B, Nosova E, Milloy M-J, Hayashi K, Wood E, Kerr T, & DeBeck K (2020). Coercion into addiction treatment and subsequent substance use patterns among people who use illicit drugs in Vancouver, Canada. Addiction, 115(1), 97–106. 10.1111/add.14769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Development Team. (2015). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. http://www.R-project.org [Google Scholar]

- Robitzsch A, & Grund S (2020). miceadds: Some Additional Multiple Imputation Functions, Especially for “mice.” R package version 3.9–2. [Google Scholar]

- Smart R, & Pacula RL (2019). Early evidence of the impact of cannabis legalization on cannabis use, cannabis use disorder, and the use of other substances: Findings from state policy evaluations. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 45(6), 644–663. 10.1080/00952990.2019.1669626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahler GJ, Mennis J, & DuCette JP (2016). Residential and outpatient treatment completion for substance use disorders in the U.S.: Moderation analysis by demographics and drug of choice. Addictive Behaviors, 58, 129–135. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.02.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2016). Treatment episode data set—Discharges (TEDS-D)—Concatenated, 2006 to 2014 [Data set] Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://www.datafiles.samhsa.gov/study-dataset/treatment-episode-data-set-discharges-2006-2014-teds-d-2006-2014-ds0001-nid18549 [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2018a). Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS) Discharges, 2015 [Data set]. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://www.datafiles.samhsa.gov/study/treatment-episode-data-set-discharges-teds-d-2015-nid18450 [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2018b). Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS) Discharges, 2016 [Data set]. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://www.datafiles.samhsa.gov/study/treatment-episode-data-set-discharges-teds-d-2016-nid18452 [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2019a). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP19–5068, NSDUH Series H-54). Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/ [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2019b). Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS), 2017 [Data set]. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2019c). Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS), 2017 [Data set]. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://www.datafiles.samhsa.gov/study/treatment-episode-data-set-discharges-teds-d-2017-nid18479 [Google Scholar]

- Uusitalo S, & Eijk Y. van der. (2016). Scientific and conceptual flaws of coercive treatment models in addiction. Journal of Medical Ethics, 42(1), 18–21. 10.1136/medethics-2015-102910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veligati S, Howdeshell S, Beeler-Stinn S, Lingam D, Allen PC, Chen L-S, & Grucza RA (2020). Changes in alcohol and cigarette consumption in response to medical and recreational cannabis legalization: Evidence from U.S. state tax receipt data. International Journal of Drug Policy, 75, 102585. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.10.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.