Abstract

This paper investigates the sleeplessness in Chinese cities during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. We provide first evidence of a link from daily COVID-19 cases resulting in sleep loss in a panel of Chinese cities. We use Wuhan, which was the first city to be completely locked down, as basis to present the result that sleeplessness has become a considerably serious issue owing to the COVID-19 pandemic. In using the intervention policy of various cities as exogenous shocks, we find that lockdown policies significantly increase the sleeplessness level of Chinese cities. In addition, the severity of COVID-19 pandemic significantly exacerbates the negative effect of lockdown policies on sleep quality in the city. Overall, this study indicates that policy makers should pay more attention to public mental health when citizens recover from COIVD-19 by investigating the unintended consequences of COVID-19 on sleeplessness level of cities.

Keywords: COVID-19, Sleeplessness, Lockdown, Baidu search index

1. Introduction

This paper exploits the exogenous shock of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, and uses a variety of high-quality data set to study the effect of the unprecedented lockdown policies on sleeplessness in the context of China. Given the importance of mental health (Alexander and Schnell, 2019, Douven et al., 2015, Kung et al., 2018, Mullins and White, 2019), we attempt to contribute to related literature by providing a timely evaluation on the unintended consequences of COVID-19 pandemic.

The COVID-19 pandemic has triggered enormous and heterogeneous global public health and economic crises. In January 2020, a series of pneumonia cases, which were eventually traced to and called COVID-19, was identified in Wuhan, where a lockdown policy was implemented on January 23 of 2020. Thereafter, the COVID-19 pandemic became the focused throughout China and, eventually, the world. By April 2020, COVID-19 has infected over 2.5 million people in 217 countries, with over 170,000 deaths. National governments responded quickly and increasingly implemented strict public health measures. In addition, various countries provided a series of stimulus packages1 to address a new round of economic crisis.2

COVID-19 is a health and geopolitical crisis, simultaneously spilling over into the real economy and financial markets (Fang et al., 2021, Nguyen and Hoang Dinh, 2021, Wang et al., 2022). Accordingly, studies on the economic consequences of COVID-19 have attracted significant attention from scholars and policy makers, thereby providing a wealth of conclusions on all fronts. For example, Chen, Qian, and Wen (2021) found that 214 Chinese cities after the outbreak of COVID-19 experienced significant consumption decreases ranging from 14% to 69% in late January 2020. Correspondingly, the firm also was greatly affected from all aspects, such as stock returns (Ding, Levine, Lin, & Xie, 2021) and investment (Jie, Hou, Wang, & Liu, 2021). Based on the lockdown policy that strictly restricted human mobility and economic activities, Fang, Wang, and Yang (2020) found that the lockdown in Wuhan reduced human mobility with inflow into Wuhan by 76.64%, outflow from Wuhan by 56.35%, and within-Wuhan movements by 54.15%. Moreover, Liu, Kong, and Kong (2021) determined that lockdown policies significantly reduced air pollution by an average of 12%.

There is one strand of literature that focuses on the public health. For instance, Huang, Wang, Li, Ren, Zhao, Hu, Gu et al. (2020) investigated the clinical features of patients infect with COVID-19 disease. Kuchler, Stroebel, and Russel (2020) argued that online social networks might prove beneficial to epidemiologists, and those hoping to forecast the spread of communicable diseases, such as COVID-19. Karaivanov, Lu, Shigeoka, Chen, and Pamplona (2021) found that mask mandates significantly decreased new COVID-19 case. Nevertheless, few studies analyze the impact of COVID-19 on the public sentiment and mental health.

Sleep is an essential aspect of the human well-being. However, under enormous psychological pressure, human being is susceptible to anxiety and depression, even troubling in falling sleep. For instance, COVID-19 disease appears to be more contagious and has longer incubation period than the flu virus, thereby resulting in many people being unaware of whether they are coronavirus carrier, then being with the fear of contracting of COVID-19. Second, to suppress the spread of COVID-19, the Chinese government decided to require the public to maintain social distancing, undergo self-isolation, and even sealed off the city. Unfortunately, the result, such as self-isolation, compulsorily staying at home, forbidding to go out and so on, led residents to persistent depression or anxiety, even panic. Third, owing to the expectation of economic downturn caused by the pandemic, people had to face the fact that they would receive minimal income for a long time and even experience job loss. Overall, self-isolation and severe economic dilemma, apart from the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic, exerts psychological pressure and even mental trauma on citizens.

Given that the COVID-19 pandemic was spreading, unprecedented financial problems have begun and the number of unemployed is increasing. Moreover, the severe status under the threat of COVID-19 and enormous economic pressure may develop serious mental health issue, which anxiety and sleeplessness are becoming increasingly serious. Thus, based on the sleeplessness in Chinese cities, we study the impact of COVID-19 on citizens' mental health and enrich the literature on the citizens' mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The reason why we restrict our research scope to the sleep quality in the context of China is as following two grounds. Firstly, sleep loss has been a significant problem in China during the period without the COVID-19 pandemic. For instance, 15% of Chinese are insomniac, thereby implying that over 207 million people suffer from a sleep disorder.3 In 2019, the topic on 300 million Chinese suffering from sleep disorders was posted in Weibo's list of the hottest search terms,4 with 540 million reading and 123,000 discussions. Secondly, China offers a good setting to assess the economic impact of COVID-19. On the one hand, this country was the first to experience a large-scale outbreak that started in January 2020, thereby providing statistical power for us to obtain credible estimation. On the other hand, considering that there was no the precedent in other countries that the spread of COVID-19 successfully have been stopped, this severe situation may further worsen citizens' mental health, thereby resulting in the more negative moods, including worries, anxiety, even sleeplessness. Noticeably, psychological disorder has been linked to a wide range of negative outcomes.

To conduct an empirical analysis, we follow Heyes and Zhu (2019) and measure sleeplessness in Chinese cities by using the sleeplessness search index from the website of Baidu Index (like Google Trend), which provides daily information on keyword search index in 400 cities across the country. Comparing with prior studies that use the sleeplessness data from a lot of surveys (Obradovich, Migliorini, Mednick, & Fowler, 2017), our sleeplessness variable covers most of citizens in a city as far as possible, and can reflect the sleeplessness level of the city. More importantly, sleeplessness variable in this paper puts emphasis on capturing the mood of insomnia and anxiety,5 which is consistent with our research purpose how the spread of COVID-19 affect the public anxiety and mental health from the view of sleeplessness in Chinese cities.

By using data of over 300 cities across China from January 1, 2020 to February 29, 2020, we set as the cumulative number of confirmed cases in city i on day t, to investigate the impact of the COVID-19 case on citizens' sleeplessness. We find that the spread of COVID-19 and increasing number of confirmed cases in China significantly decrease sleep in a city by an average of 4.5%. Then, we conduct a series of tests to check the robustness of our findings, including using the lagged sleeplessness as dependent variable to address the effect of virus' incubation, and using alternative the measurement of COVID cases, and controlling time-varying city fixed effects, and enlarging the sample range.

Next, we collect announcements related to lockdown policies in Chinese cities,6 and use various difference-in-differences (DID) estimation strategies to identify the effects of lockdown policies on sleeplessness. First, we regard the implementation date of Wuhan lockdown as the origin of the COVID-19 pandemic to study the spillover effects of this lockdown policy. Empirical result shows that the Wuhan lockdown had significant spillover effects for other cities. Second, to further investigate the effects of the government intervention policies, we use the sample of 2020 data for 80 locked down cities and 284 cities that were never locked down during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our finding suggests that the lockdown policy significantly decreases sleep in a city, Thirdly, we examine the heterogeneous effects of cities' connections with Wuhan and anxiety mood on our DID results, and find that the negative effect of lockdown policies would be more pronounced in cities where more people are connected to Wuhan, or more people in anxiety.

Lastly, we use to capture the joint impact of COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown policies on sleeplessness, and present strong evidence that the lockdown policy significantly leads to serious sleeplessness, and that the severity of COVID-19 pandemic significantly worsen the situation.

We contribute to the literature in three ways. First, we add to the literature that uses the far-reaching search engine data to develop a novel measurement on the public sentiment and behavior. For instance, Ginsberg, Mohebbi, Patel, Smolinski, and Brilliant (2009) used Google search engine data to detect influenza epidemic. Similarly, based on Google search data on relevant keywords, Keane and Neal (2021) constructed the variable of consumer panic and explored the volatility of panic index among different countries during the COVID-19 pandemic. By using the world's largest Chinese-language search engine (Baidu search engine), we hence, contribute to the related literature by focusing on the public moods with a large population of sample in the context of China (Xu, Feng, Li, & Jia, 2022).

Second, we complement the literature on public health related to COVID-19 by providing a rigorous estimation of the impact of COVID-19 on the increase in the number of sleeplessness cases. While the importance of mental health has been long recognized (Alexander and Schnell, 2019, Douven et al., 2015, Kung et al., 2018, Mullins and White, 2019), prior studies have mainly focused on the economic consequences of COVID-19, such as asset markets (Wang et al., 2022), consumption (Chen et al., 2020), firms performance (Bartik et al., 2020, Ding et al., 2021, Jie et al., 2021), human mobility (Fang et al., 2020). By comparison, we concentrate on the mental stress disorder and invisible losses caused by COVID-19 instead of the direct somatic disorders and economics losses.

Third, by exploring the determinants of sleeplessness in China, the current study enriches the emerging but expanding literature on the causes and consequences of sleeplessness in China (Heyes and Zhu, 2019, Obradovich et al., 2017), thereby offering timely policy implications for policy makers. What's more, we present empirical evidence that lockdown policies, cities' connection, and anxiety moods are important driving forces of sleeplessness. Such findings could be taken as a benchmark for regulators in public mental health when citizens recover from COIVD-19.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the data and empirical strategy. Section 3 presents the baseline results and robustness checks. Section 4 explores the effects of lockdown policies and cross-sectional heterogeneity. Section 5 concludes this paper.

2. Data and empirical strategy

2.1. Data and sample

This paper mainly uses following data sets to conduct empirical analysis, such as the daily Baidu search Index data, the daily COVID-19 cases, the daily weather conditions for major cities in China, and the implementation date of lockdown policies in Chinese cities during the COVID-19 pandemic.

First, Baidu (http://baidu.com) is China's leading search engine and has been the favorite in the country, occupied with an 80% share of the Chinese search engine market.7 Correspondingly, the search volume of specific keyword in Baidu search engine is summed and presented in the Baidu Index website (http://index.baidu.com). Thus, to describe the sleeplessness level in each city, we collect the daily search volume of keywords on sleeplessness in the Baidu search engine from users located within cities in China. Second, we obtain COVID-19 pandemic data about cumulative number of confirmed cases and death cases in all cities from the China Stock Market & Accounting Research Database (CSMAR). Third, to control the effect of weather conditions on sleep quality, we collect the weather factors in all cities from the China Meteorological Administration (CMA) website, including the maximum wind speed, precipitation, average humidity, and average temperature of each station. Subsequently, we define city-level weather conditions as the average of stations within the corresponding city.

Next, to suppress the spread of COVID-19, the central government of China imposed an unprecedented lockdown in Wuhan from 10 AM on January 23, 2020, and in other cities in Hubei Province several days later. As of February 29, 2020, 80 cities in 22 provinces have imposed different levels of lockdown policies. We collect announcements related to lockdown policies to study the intervention policies, including completed lockdown, partial lockdown, and setting up checkpoints and quarantine zones.

This paper mainly uses the daily data on over 300 cities across China from January 1, 2020 to February 29, 2020, exactly covering the period of one month before and after the outbreak of COVID-19. After removing the miss variables, we obtain the finally sample that includes 13,585 city-days observations.

2.2. The measure of sleeplessness

The important challenge in this paper is to measure the degree of sleeplessness in all cities. Prior studies have used the sleeplessness data from a lot of surveys (Obradovich et al., 2017). However, compared with the huge quantity of citizens in a city, the data from surveys or questionnaires is too limited and unable to reflect the sleeplessness level of the city.

With the development of internet and big data, it is no longer a hard work to collect and handle the tremendous data of the public sentiments and mental health. For instance, based on the search engine data from Google Trends, Bilgin, Demir, Gozgor, Karabulut, and Kaya (2019) constructed the word list of economic and financial uncertainty, and collected the search query volumes of these words to capture macroeconomic uncertainty of Turkey. Analogously, Costola, Iacopini, and Santagiustina (2020) used the search query volumes of several important countries' name to capture the public attention during the COVID-19 pandemic. To investigate the intention of migrating to other countries, Nakamura and Suzuki (2021) select 67 keywords related to migration decisions and collect the search volumes of these words from Google Trends Index. Based on the important social media site Weibo (like Facebook and Twitter) in China, Heyes and Zhu (2019) used the frequency of keyword on sleeplessness to construct the sleeplessness level of a city.

Thus, referring to the previous literature (Ginsberg et al., 2009, Heyes and Zhu, 2019, Keane and Neal, 2021), we collect the search quantity of keywords on sleeplessness from Baidu Index to measure the sleeplessness level in each city. Baidu search engine is the most popular and widely-used Chinese search engine in China, covering the great majority of users and cities in China. The higher Baidu Index of special keywords, the more attention users located within cities focus on related topics. Comparing with other online platform, the purpose of users in Baidu search engine mainly is to find a solution for their problems rather than share their moods and feelings (such as social media site).8 Hence, these users who search keywords on sleeplessness are more likely to have the symptom of insomnia,9 even have gotten sleep disturbances for several days. More importantly, owing to the low barrier of entry for users, Baidu search index is more representative of the sleeplessness level in each city. Consequently, this paper uses the search quantity of keywords on sleeplessness to describe the sleeplessness level in a city and further reflect the degree of mental well-being in this city.10

Another concern in this research is the range of keywords on sleeplessness, which is directly related to the availability of our key variable. Following Heyes and Zhu (2019), we choose “Shimian” and “Shuibuzhao” as keywords, which can express “sleepless,” “can't fall asleep,” “losing sleep,” and “insomnia,” among others. There is a lot of words that have the same semantic meaning as sleeping because of the extensive vocabulary and different phraseologies in Chinese writing. However, colloquial language is frequently used in daily life, and Internet users are more likely to search for information by using simple and common words. Thus, the other terms that have meaning equivalent to the difficulty sleeping may not affect our conclusions.

Based on different ports that serve as connection point to a web service, Baidu Search Index data provides three search index indicators: (1) daily PC index of a city, which is the keyword search volume that Internet users search via personal computer ports; (2) daily wise index of a city, which is measured as the search quantity of keywords from smart phone ports; and (3) daily all index of a city, which is the sum of the PC and wise indexes. The index indicators are consistent across cities and time. The development of mobile Internet has resulted in an increasing number of people using phones to search for information they need. Moreover, people probably use their phones to search sleeplessness at night when they lose sleep. Hence, the wise and all indexes substantially represent sleeplessness level in a city.

Noticeably, the sleeplessness variable that we construct in this paper is not direct measurement for insomniac in a city. Based on the nature of Baidu search index, the value of sleeplessness variables primarily stands for the level of concern that citizens in each city focus on sleepless problem, or the demand of sleepless information. A strong focus on sleeplessness can reflect worries, anxieties and sleeplessness in a city, thereby capturing the sleeplessness level. Given that this research focuses on public mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic, the sleeplessness search index is highly appropriate to measure sleep quality in a city and further describe entire mental well-being of this city.

Accordingly, when explaining the economic implications of empirical results below, the value of coefficients on independent variables reflects the effect on level of sleeplessness rather than the number of insomnias in a city. In this paper, the higher level of sleeplessness during the COVID-19 pandemic is more connected with psychological pressure, poor sleep quality and lower mental well-being, which owes to the fear of the COVID-19 disease and damage of the pandemic on all aspects of society.

2.3. Model specifications

We use OLS to estimate the association between COVID-19 cases and sleeplessness. The specification is as the follow:

| (1) |

where i denotes the city and t denotes the daily date, the dependent variable is a measure of sleeplessness in city i on day t. Here, we introduce two measures to proxy the degree of sleeplessness ( and ), which denotes the sum of search quantity by personal computer ports and smart phone ports, or the search quantity by smart phone ports, respectively. is the logarithm of the cumulative number of confirmed cases in city i on day t. As weather change may directly affect mental health (Hansen et al., 2008), we also control for the daily weather variable , including maximum wind speed, precipitation, average humidity, and average temperature, to eliminate the impact of weather conditions. Lastly, we control for the city fixed effect to eliminate the impact of unobserved, time-unvarying city attributes on sleeplessness. We control for the date fixed effect to eliminate the impact of time-varying attributes on air quality, including weekend, month, and Spring Festival Holiday dummies.

3. Estimation result

3.1. Descriptive statistics

We first present the summary statistics of key variables in Table 1. We winsorize all continuous variables at the 1st and 99th percentiles to alleviate the concern that our results may be driven by outliers. Panel A of Table 1 presents the summary statistics in the full sample. The dependent variable Sleeplessness index from personal computer ports and smart phone ports has a mean of 121.8 with a variance of 95.01. As we predicted, Sleeplessness1 that is search index from smart phone port has a mean of 102.5 with a variance of 71.68, which is nearly close to the search index from PC and smart phone ports. The 25th percentile of Covid is 0, which means that nearly a quarter of city-days is no pandemic.

Table 1.

Summary Statistics.

| Mean | S.D | P25 | Median | P75 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: All Cities | |||||

| Sleeplessness | 121.8 | 95.01 | 58 | 118 | 159 |

| Sleeplessness1 | 102.5 | 71.68 | 58 | 104.5 | 137 |

| Covid | 1.582 | 1.784 | 0 | 1.099 | 2.890 |

| Wind Speed | 4.317 | 2.283 | 2.700 | 4 | 5.300 |

| Precipitation | 1.153 | 3.824 | 0 | 0 | 0.100 |

| Humidity | 0.683 | 0.177 | 0.570 | 0.700 | 0.813 |

| Temperature | 3.202 | 9.846 | -3.343 | 4.088 | 10.01 |

| Obs | 13,858 | ||||

| Panel B: Locked Cities | |||||

| Sleeplessness | 189.8 | 123.8 | 78 | 172 | 264 |

| Sleeplessness1 | 152.4 | 89.97 | 67 | 142 | 204 |

| Covid | 2.318 | 2.265 | 0 | 2.079 | 4.060 |

| Wind Speed | 4.684 | 2.518 | 3 | 4 | 6 |

| Precipitation | 1.146 | 3.807 | 0 | 0 | 0.075 |

| Humidity | 0.708 | 0.159 | 0.611 | 0.718 | 0.824 |

| Temperature | 3.561 | 9.710 | -1.601 | 5.042 | 9.479 |

| Obs | 3300 | ||||

| Panel C: Unlocked Cities | |||||

| Sleeplessness | 100.5 | 71.86 | 58 | 86 | 133 |

| Sleeplessness1 | 86.97 | 56.53 | 58 | 67 | 128 |

| Covid | 1.352 | 1.533 | 0 | 0.693 | 2.639 |

| Wind Speed | 4.202 | 2.191 | 2.600 | 3.900 | 5.100 |

| Precipitation | 1.155 | 3.830 | 0 | 0 | 0.100 |

| Humidity | 0.676 | 0.182 | 0.558 | 0.693 | 0.810 |

| Temperature | 3.090 | 9.887 | -3.800 | 3.662 | 10.24 |

| Obs | 10,558 | ||||

Notes: This table presents the descriptive statistics of our main variables. All variables are defined in Appendix A. Panel A reports the summary statistics of all cities in 2020. Then we report the sleeplessness index on all cities. Panel B reports the statistics on the official lockdown cities. Panel C reports the statistics on unlocked cities.

Panel B shows the sleeplessness and COVID-19 pandemic within the lockdown cities with different types of lockdown interventions, such as completed lockdown, partial lockdown, and setting up checkpoints and quarantine zones. By comparison, Panel C reports the sleeplessness and COVID-19 pandemic within unlocked cities. Evidently, the mean of sleeplessness in locked cities is nearly twice that in unlocked cities. The COVID-19 case in cities where issued the lockdown policy is markedly more serious than those in unlocked cities.

3.2. Baseline results

This section estimates Model (1) to identify the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on sleeplessness level of cities. Table 2 reports the coefficients from estimating Model (1), in which the independent variable is log form of the cumulative number of confirmed cases of COVID-19, and the dependent variable is the sleeplessness. We find that the coefficient of Covid in Table 2 is significantly positive with different measurement of sleeplessness level. These results suggest a highly significant and robust relationship between COVID-19 cases and sleeplessness level of cities.

Table 2.

Baseline Results.

| Variables |

|

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| 3.575*** | 3.479*** | 2.405*** | 2.350*** | |

| (0.429) | (0.429) | (0.323) | (0.323) | |

| 0.221 | 0.174 | |||

| (0.218) | (0.159) | |||

| -0.009 | 0.064 | |||

| (0.105) | (0.078) | |||

| 18.589*** | 12.539*** | |||

| (3.109) | (2.292) | |||

| 0.320** | 0.328*** | |||

| (0.127) | (0.097) | |||

| City Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Date Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | 116.109*** | 101.590*** | 98.739*** | 88.385*** |

| (0.755) | (2.605) | (0.573) | (1.923) | |

| Observations | 13,858 | 13,858 | 13,858 | 13,858 |

| R-squared | 0.837 | 0.838 | 0.842 | 0.843 |

Notes: This table reports the impact of COVID-19 on sleeplessness. The dependent variable is Sleeplessness. The key independent variable is Covid. All variables are measured are defined in Appendix A. Robust standard errors are reported in parentheses. Significance at 10%, 5%, and 1% levels was indicated by *, **, and ***, respectively.

Except for somatic disorders caused by COVID-19 disease, the spread of COVID-19 exerts the negative and significant impact on sleep quality and mental health of citizens. For instance, with the increasing number of confirmed cases in Chinese cities, the more and more citizens in these cities feel anxious, along with the fear of contracting the COVID-19 disease, eventually getting trouble falling asleep. Moreover, negative moods also are caused by self-isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Forbidding to go out and mandatorily staying at home for a long time would harm the mental health severely, thereby resulting in sleep loss, especially in the city where the pandemic is the more serious.

In summary, the spread of COVID-19 has significant influence on sleeplessness in the level of city. The increasing number of confirmed cases in China could significantly incur an additional 3.6–4.5%11 increase in sleeplessness in the level of city.

3.3. Robustness checks

This section conducts several tests to check the robustness of our findings, including reducing the effect of virus' incubation, using alternative the measurement of COVID, controlling time-varying city fixed effects and enlarging the sample range.

3.3.1. Effect of incubation

Thus far, we find that the spread of COVID-19 has a negative impact on sleep quality in a city. Given that we use reported infections of COVID-19 to capture the severity of pandemic, the virus' incubation may disturb our results. More specifically, reported COVID-19 cases generally lag true COVID-19 cases by several days. In other words, the number of reported COVID-19 cases in day t is more likely to describe the scale of pandemic in day t-n (n > 1). Thus, the lagged effect of reported infections needs to be included in regression model.

To address the lagged effect of reported infections, we use the lagged sleeplessness variable as dependent variable to verify our results. Table 3 shows the related result. We find that the coefficient of Covid are significantly positive and statistically significant at the 1% level when using lagged variables of sleeplessness.12 It suggests that the confirmed cases of COVID-19 cause the increase in sleeplessness level of cities, revealing that our findings are not driven by the effect of virus' incubation.

Table 3.

Robustness check: the effect of incubation.

| Variables |

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| 2.146*** | 1.623*** | 1.623*** | 1.332*** | |

| (0.453) | (0.465) | (0.346) | (0.354) | |

| -0.162 | 0.132 | 0.000 | 0.060 | |

| (0.220) | (0.227) | (0.162) | (0.166) | |

| 0.112 | -0.023 | 0.026 | -0.002 | |

| (0.107) | (0.112) | (0.074) | (0.081) | |

| 0.523 | -2.560 | -2.457 | -3.726 | |

| (3.189) | (3.233) | (2.354) | (2.396) | |

| -0.136 | -0.371*** | -0.084 | -0.215** | |

| (0.131) | (0.132) | (0.099) | (0.099) | |

| City Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Date Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | 116.943*** | 118.912*** | 100.500*** | 101.598*** |

| (2.690) | (2.720) | (1.987) | (2.019) | |

| Observations | 12,932 | 12,701 | 12,932 | 12,701 |

| R-squared | 0.835 | 0.834 | 0.839 | 0.838 |

Notes: This table reports the impact of coronavirus' incubation. The dependent variable is the lagged Sleeplessness. The key independent variable is Covid. All variables are measured are defined in Appendix A. Robust standard errors are reported in parentheses. Significance at 10%, 5%, and 1% levels was indicated by * , * *, and * ** , respectively.

3.3.2. Alternative COVID-19

We use the accumulated death cases of COVID-19 to measure the severity of the pandemic and check the robustness of our findings. Table 4 shows the regression results. Consistent with baseline results, the result in Table 4 shows that the coefficient of Covid is significantly positive, thereby revealing that the positive effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on sleeplessness in a city is robust to alternative measurement of COVID-19 death cases.

Table 4.

Alternative COVID-19: Accumulated Death Case.

| Variables |

|

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| 6.867*** | 6.523*** | 5.640*** | 5.400*** | |

| (1.343) | (1.343) | (0.906) | (0.907) | |

| 0.234 | 0.179 | |||

| (0.218) | (0.159) | |||

| -0.029 | 0.053 | |||

| (0.105) | (0.078) | |||

| 19.045*** | 12.725*** | |||

| (3.111) | (2.291) | |||

| 0.303** | 0.313*** | |||

| (0.127) | (0.097) | |||

| City Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Date Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | 121.120*** | 106.190*** | 102.014*** | 91.506*** |

| (0.353) | (2.556) | (0.259) | (1.884) | |

| Observations | 13,858 | 13,858 | 13,858 | 13,858 |

| R-squared | 0.837 | 0.837 | 0.842 | 0.842 |

Notes: This table reports the impact of COVID-19 on sleeplessness by different COVID-19 case. The key independent variable is Covid, which is accumulated death case of COVID-19. All variables are measured are defined in Appendix A. Robust standard errors are reported in parentheses. Significance at 10%, 5%, and 1% levels was indicated by *, **, and ***, respectively.

3.3.3. Alternative fixed effects

Our baseline model has controlled city fixed effect and date fixed effect. However, there are unknown omitted variables that may affect the positive relationship between the COVID-19 pandemic and sleeplessness in a city, such as the time-varying city features. To further reduce the effect of omitted variables, we include city fixed effect, and related interaction term with week fixed effect. Panel A of Table 5 reports the regression results. We find that the coefficient of Covid is significantly positive after alleviating concerns of the time-varying city features, which is consistent with our baseline results.

Table 5.

Alternative fixed effect and sample period.

| Variables |

|

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Panel A: Controlling more fixed effect | ||||

| 2.975** | 4.074*** | 3.311*** | 4.128*** | |

| (1.278) | (1.285) | (0.969) | (0.973) | |

| Control Variables | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| City Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Week Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| City*Week Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 13,858 | 13,858 | 13,858 | 13,858 |

| R-squared | 0.853 | 0.854 | 0.855 | 0.856 |

| Panel B: Enlarging the sample range | ||||

| 0.812*** | 0.897*** | 0.452*** | 0.531*** | |

| (0.193) | (0.194) | (0.141) | (0.142) | |

| Control Variables | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| City Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Date Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | 115.111*** | 115.041*** | 95.043*** | 92.902*** |

| (0.108) | (1.505) | (0.082) | (1.137) | |

| Observations | 164,678 | 164,678 | 164,678 | 164,678 |

| R-squared | 0.824 | 0.825 | 0.819 | 0.819 |

Notes: This table reports the impact of COVID-19 on sleeplessness by controlling more fixed effect and changing the sample range. Panel A shows the result of including the interaction of city fixed effect, week fixed effect. Panel B reports the result of enlarging the sample range by using the data from Jan 1, 2019 to Dec 31, 2020. The dependent variable is Sleeplessness. The key independent variable is Covid. All variables are measured are defined in Appendix A. Robust standard errors are reported in parentheses. Significance at 10%, 5%, and 1% levels was indicated by *, **, and ***, respectively.

3.3.4. Enlarging the sample range

As note, in our baseline results, we use the daily data from January 1, 2020 to February 29, 2020, to conduct the regression result. Short sample interval probably has difficulty in reflecting the real effect of COVID-19 on sleep quality. To further investigate the sleeplessness in a city during the COVID-19 pandemic, we extend the sample period to check the robustness of sample interval. More specifically, we use the daily data from Jan 1, 2019 to Dec 31, 2020, to reduce the effect of seasonal factors. Panel B of Table 5 reports the regression result. These results show that the severity of COVID-19 are positively and significantly related to sleeplessness in the level of city. With the increase of sample period and covering the more range of post-COVID-19, the baseline result is little disturbed.

4. The lockdown policy

4.1. Spillover effects of Wuhan

Wuhan in Hubei Province is China's hardest hit city by the COVID-19 pandemic, and where the virus emerged from early December 2019. On January 20, 2020, the finding indicated that COVID-19 disease could be transmitted from person to person, resulting in COVID-19 pandemic spreading widely and fast. On January 23, 2020, the government of Wuhan issued the lockdown policy, thereby revealing that China had mobilized the entire country to respond to the outbreak. Moreover, this situation implied that the COVID-19 pandemic was much more serious that Wuhan must be locked down to suppress the spread of the virus. That is, the Wuhan lockdown can be regarded as the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

To investigate the spillover effects of the Wuhan lockdown, we include the dummy variable PostWuhan, which takes a value of 1 after Wuhan issued its lockdown policy, or after January 23, 2020 for all cities; and 0 otherwise. In particular, we re-estimate the impact of the Wuhan lockdown on sleeplessness using the following specifications:

| (2) |

where i denotes the city and t denotes the daily date. The dependent variable is a measure of sleeplessness in city i on day t. The key variable of our design is , which captures the impact of the spillover effects of the Wuhan lockdown policy. Noticeably, the effect of is absorbed because of controlling the day fixed effect.

Table 6 reports the regression results. As shown, the coefficients of are significantly positive in all columns. These results suggest that the Wuhan lockdown had significant spillover effects for other cities, leading cities' citizens to fall into sleeplessness and feel the more anxious.

Table 6.

Spillover Effect of Wuhan.

| Variables |

|

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| -9.412*** | -9.481*** | -6.114*** | -6.153*** | |

| (2.327) | (2.337) | (1.452) | (1.451) | |

| 13.077*** | 13.052*** | 8.578*** | 8.563*** | |

| (2.307) | (2.317) | (1.435) | (1.435) | |

| Control Variables | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| City Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Date Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | 116.101*** | 101.689*** | 98.734*** | 88.449*** |

| (0.748) | (2.604) | (0.569) | (1.922) | |

| Observations | 13,858 | 13,858 | 13,858 | 13,858 |

| R-squared | 0.838 | 0.838 | 0.843 | 0.843 |

Notes: This table reports the spillover effect of the lockdown policy. The key independent variable is . All variables are measured are defined in Appendix A. Robust standard errors are reported in parentheses. Significance at 10%, 5%, and 1% levels was indicated by * , * *, and * ** , respectively.

4.2. Effects of lockdown policy

To suppress the spread of COVID-19 in China, government decided to require the public to maintain social distancing, undergo self-isolation, and even sealed off the city. Fang et al. (2020) indicated that 80 cities in 22 provinces issued different level of lockdown policies before February 20, 2020, including completed lockdown, partial lockdown, and setting up checkpoints and quarantine zones. By using this setting as basis, this paper employ DID approach to investigate the impact of lockdown policies during the COVID-19 period. Furthermore, we verify parallel trend of our DID data, and conduct robustness checks, and explore heterogeneous effect of connection with Wuhan and anxiety on the utility of lockdown policies.

4.2.1. Effect of lockdown policy on sleeplessness

Referring to prior literature (Liu et al., 2021), we first employ several DID estimation strategies by comparing treatment and control groups to identify the impact of lockdown policies on sleeplessness. We use the sample of the 2020 data for 80 locked cities and 284 cities that were never locked down during the outbreak. The DID specification can be described as follows:

| (3) |

where i denotes the city and t denotes the daily date. The dependent variable is a measure of sleeplessness in city i on day t. takes a value of 1 if city i issues any lockdown policies in 2020, and 0 otherwise. takes a value of 1 for the sample period after city i issues any lockdown policies, and 0 otherwise. The key variable of the DID design is , which captures the impact of lockdown policies in all cities. Due to control city fixed effect and date fixed effect, the impact of and are omitted, thereby not reporting the coefficient of and in subsequent results.

Second, according to the severity of COVID-19 pandemic in different cities, governments implement the different degree of lockdown policies, consisting of completed lockdown, partial lockdown, and setting up checkpoints and quarantine zones. To further investigate the effect of different lockdown policies, we employ the following specification to conduct empirical analysis.

| (4) |

where takes a value of 1 if city i have issued the completed lockdown policy in date t, and 0 otherwise. takes a value of 1 if city i have issued the partial lockdown policy in date t, and 0 otherwise. takes a value of 1 if city i have set up checkpoints and quarantine zones in date t, and 0 otherwise. Moreover, we control the weather conditions, and city fixed effect, and date fixed effect.

Table 7 reports the regression results about the effect of lockdown policies. Panel A compares the locked down cities in 2020 with the cities that were not locked down in 2020 by regressing Model (3). The coefficients of are significantly positive in all columns, suggesting that the lockdown policy significantly decrease sleep by an average of 6.7%− 10.4%.13 Panel B report the results of lockdown policies by using Model (4). We find that the coefficients of different lockdown policies variables. Completed Lockdown, Partial Lockdown, Checkpoint, are positive and statistically significant, revealing that the implementation of different lockdown policies could exert a significantly negative effect on sleep quality no matter the level of lockdown policies. Hence, we provide evidence that three kinds of lockdown policies result in the increase of cities' sleeplessness relative to cities without the shock of the lockdown policy. Additionally, the lockdown policy about setting up checkpoints and quarantine zones would cause the weaker effect on sleeplessness relative to other lockdown policies. However, it is hard to identify the difference among the level of lockdown policies.

Table 7.

Effect of Lockdown Policy.

|

Panel A: Effect of lockdown policy | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables |

|

|

||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |||

| 12.905*** | 12.670*** | 6.975*** | 6.856*** | |||

| (1.613) | (1.615) | (1.075) | (1.077) | |||

| Control variables | No | Yes | No | Yes | ||

| City Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Date Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Constant | 120.488*** | 105.788*** | 101.853*** | 91.260*** | ||

| (0.369) | (2.549) | (0.267) | (1.881) | |||

| Observations | 13,858 | 13,858 | 13,858 | 13,858 | ||

| R-squared | 0.837 | 0.838 | 0.842 | 0.842 | ||

| Panel B: Effect of different lockdown policy | ||||||

| Variables | ||||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |||

| 14.329*** | 13.980*** | 12.314*** | 12.064*** | |||

| (3.817) | (3.823) | (2.720) | (2.724) | |||

| 22.637*** | 22.368*** | 9.916*** | 9.816*** | |||

| (3.901) | (3.895) | (2.172) | (2.162) | |||

| 10.779*** | 10.575*** | 5.273*** | 5.179*** | |||

| (1.876) | (1.880) | (1.237) | (1.240) | |||

| Control variables | No | Yes | No | Yes | ||

| City Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Date Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Constant | 120.465*** | 105.772*** | 101.811*** | 91.251*** | ||

| (0.369) | (2.549) | (0.268) | (1.880) | |||

| Observations | 13,858 | 13,858 | 13,858 | 13,858 | ||

| R-squared | 0.837 | 0.838 | 0.842 | 0.842 | ||

| Panel C: Effect of multi-valued lockdown policy | ||||||

| Variables | ||||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| 7.252*** | 5.983*** | |||||

| (2.062) | (1.359) | |||||

| 12.808*** | 8.795*** | |||||

| (3.235) | (2.006) | |||||

| -7.185 | 1.881 | |||||

| (5.624) | (3.578) | |||||

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| City Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Date Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | 169.206*** | 169.070*** | 150.542*** | 133.898*** | 133.728*** | 114.217*** |

| (6.463) | (6.468) | (17.091) | (4.299) | (4.306) | (10.214) | |

| Observations | 3300 | 3300 | 900 | 3300 | 3300 | 900 |

| R-squared | 0.894 | 0.894 | 0.871 | 0.913 | 0.913 | 0.903 |

Notes: This table reports the impact of the lockdown policy on sleeplessness level of city. Panel A reports the impact of lockdown policy on sleeplessness. equals one if city i issues any lockdown policies in 2020, and 0 otherwise. takes a value of 1 for the sample period after city i issues any lockdown policies, and 0 otherwise. Panel B reports effect of different lockdown policies on cities' sleeplessness. takes a value of 1 if city i have issued the completed lockdown policy in date t, and 0 otherwise. takes a value of 1 if city i have issued the partial lockdown policy in date t, and 0 otherwise. takes a value of 1 if city i have set up checkpoints and quarantine zones in date t, and 0 otherwise. Panel C shows the heterogeneous effect of different lockdown policies. takes a value of 3 if city i issued completed lockdown policy, equals 2 for city i issued partial lockdown policy, and equals 1 for city i set up checkpoints and quarantine zones policies. takes a value of 1 if city i have issued the completed or partial lockdown policy in date t, and 0 otherwise. Other variables are measured are defined in Appendix A. Robust standard errors are reported in parentheses. Significance at 10%, 5%, and 1% levels was indicated by *, **, and ***, respectively.

Third, above results have demonstrated that lockdown policies result in the increase of cities' sleeplessness relative to the cities without the shock of policies no matter the type of policies. Another thing worth pointing out is that the shock of the lockdown policy on cities' sleeplessness probable varies with the level of these policies. We thus introduce a new multi-valued variable to measure variation in treatment intensity. Specifically, takes a value of 3 if city i issued completed lockdown policy, equals 2 for city i issued partial lockdown policy, equals 1 for city i set up checkpoints and quarantine zones policies. We use the interact term with and to further identify the heterogeneous effect lockdown policies, which regression model also includes the variables and . Panel C of Table 7 reports the results of multi-valued lockdown policies, which only discusses cities issued lockdown policies. As shown in column (1) and (4), the coefficient of is positive and significant. However, it is too soon to argue that the utility of lockdown policies on city sleeplessness would be the higher with the level of these lockdown policies.

When studying continuous/multi-valued treatments, the slope effect that is the causal responses to an incremental change in treatment intensity need to be incorporated into studies. The canonical DID research design compares outcomes between a treatment and comparison group (difference one) before and after that treatment begins (difference two), in which the outcomes caused by the different level of shocks are equal to be treated and obtain the average treatment effect. However, it results a misleading summary of overall average effect when canonical DID research design is applied to continuous treatment and multi-value treatment, even if satisfying strong parallel trends. As Callaway, Andrew, and Pedro (2021) stated, the strongest shocks or weakest shocks create relatively extreme causal responses, which is differ from the equal-weight in canonical DID. Hence, with the variation in treatment intensity, the heterogeneous treatment effect across treatment groups, namely selection bias, would disturbs our results.

To further and directly observe the heterogeneous treatment effect, we use variable that takes a value of 1 if city i have issued the completed or partial lockdown policy in date t, and 0 if city i have set up checkpoints and quarantine zones in date t to explore the difference between completed and partial lockdown policies and checkpoints and quarantine zones policy. Namely we set the city with checkpoints and quarantine zones as control group, which the result is reported in column (2) and (5). The results based on the coefficient of suggest that the utility of completed and partial lockdown policies on city sleeplessness would be the significantly higher than the policy of setting up checkpoints and quarantine zones. Then to distinguish the effect of completed lockdown policy from partial lockdown policy, we use the variable and conduct the regression in the sample that only includes completed and partial lockdown policies, that is to say, setting cities issued completed lockdown policies as treatment group and cities issued partial lockdown policies as control group. Column (3) and (6) in Table 7 show the comparison of completed and partial lockdown policies. According to the coefficients of , we find that there is no significant difference between the effect of completed and partial lockdown policies on cities' sleeplessness.

Consequently, three type of lockdown policies all exert the negative and significant influence on cities' sleep relative to the cities without lockdown policies. Compared with cities where set up checkpoints and quarantine zones, the citizen in cities issued completed and partial lockdown policies would suffer the more serious sleepless problem. Moreover, the impact on cities' sleeplessness doesn't vary in the completed and partial lockdown policies.

4.2.2. Parallel trend test

The base assumption of DID approach is that treatment group and control group have the parallel trend on the tested variables before the shock of events or policies. Moreover, satisfying the parallel assumption means that the difference between treatment group and control group is more likely to be caused in the post-event.

First, referring to Beck, Levine, and Levkov (2010), we examine the dynamics of the relation between lockdown policies and sleeplessness, to investigate whether our DID data satisfies the parallel assumption. Specifically, we set the issue date of lockdown policies as event day (T = 0), and then create a series of time dummy variables by modifying the issue date of lockdown policies around the real date. is a dummy variable that takes value 1 for nth day after (before) city i issues the lockdown policy, and 0 otherwise. We interact each of with our treatment variable as shown in Model (5). Following the baseline regression, we control for the same variables and fixed effects.

| (5) |

where, we set as 1 for all days that are five or more days before the issue date of lockdown policies. Similarly, equals 1 if the day n is ten or more days after the issue date of lockdown policies. Noticeably, we exclude the day of issuing lockdown policies, namely event day (n = 0) as base period, to estimating the dynamic effect of lockdown policies on sleeplessness relative to the issue day of lockdown policies.

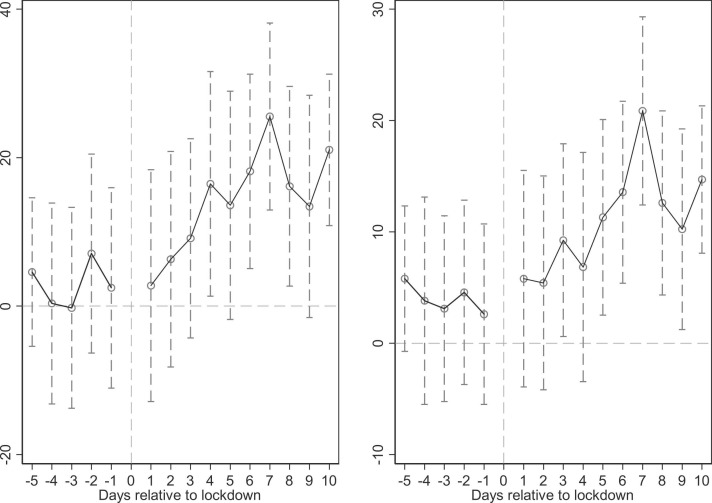

Thus, the coefficients capture the average of locked cities' sleeplessness in the nth day after (before) issuing the lockdown policy relative to in the day of issuing lockdown policies (n = 0). In the regression of Model (5), we are particularly interested in the difference of the coefficients for all interaction terms () and plot them in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The dynamic impact of lockdown on sleeplessness. Notes: This figure plots the difference of interaction terms' coefficients between the period before and after the lockdown issued date under a binary treatment variable. The dependent variables is Sleeplessness in the left graph and Sleeplessness1 in the right graph. The solid line shows the estimated coefficients over time. X-axis refers to the days relative to the implementation date of lockdown policies. In each year, the dashed line surrounding the coefficient is 95% confidence intervals of it.

Fig. 1 illustrates two key points, as the left solid line in two graphs shown, the coefficients are obviously insignificantly different from zero during the pre-issue date, with no trends in sleeplessness prior to lockdown policies. Thus, the identifying assumption associated with our DID estimation specification is supported. Note that the symptoms of sleeplessness need time to show, difficult sleep lasting for several days is generally regarded as sleepless problem by people. As shown, the impact of lockdown policy on sleeplessness are more pronounced in four days later. Both graphs suggest that sleeplessness do not precede lockdown policies, and that lockdown policies have a significant and negative effect on sleeping.

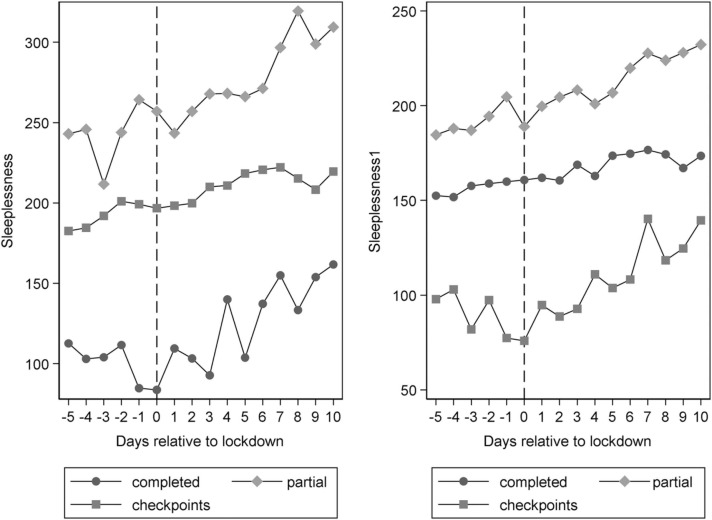

Second, above results focus on the average effect of all kind of lockdown policies. To clearly observe the parallel trend, we describe the variation of cities' sleeplessness under the different degree of lockdown policies with the different issue date. Specifically, due to lockdown policies with the different issue date, we first repeat previous processing, modifying the issue date of lockdown policies around the real date, thereby standardized dates. Then, we calculate the average of cities' sleeplessness according to the different kind of lockdown policies, and draw the graph to show the trend of cities sleeplessness among groups, which is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

The parallel trend of different degree of lockdown policies with different implementation date, Notes: This figure describes the variation of cities' sleeplessness under the different degree of lockdown policies. Y-axis refers to the average of cities' sleeplessness. X-axis represents the days relative to the implementation date of lockdown policies. completed, partial, and checkpoints is defined as the group in which cities issue completed lockdown policy, partial lockdown policy and lockdown policy about setting up checkpoints and quarantine zones.

As shown in Fig. 2, the shocks of three kinds of lockdown policies result in the significant increase of cities' sleeplessness, presenting the same and growth trend. It supports the results that lockdown policies lead to the increase of cities' sleeplessness relative to the cities without the shock no matter the type of policies. More importantly, the growth of sleeplessness in cities where issued completed or partial lockdown policies is the faster than cities where set up checkpoints and quarantine zones, which is consistent with above results. Moreover, the change of sleeplessness in cities issued completed lockdown policy and cities issued partial lockdown policy keep the parallel trend before and after the shock. It demonstrates again that the impact on cities' sleeplessness doesn't vary in the completed and partial lockdown policies.

4.2.3. Robustness checks on lockdown policies

The announcement date of lockdown policies is ahead of implementation date so that the government and the public have time to get ready for it. Faced with advance announcement of lockdown policies, the public may have timely and different response to policy information. In fact, considering the emergency of pandemic control measures, the lockdown policy is only announced a day in advance, even a few hours early. However, our results is probably disturbed by time inconsistency between announcement date and implementation date of the lockdown policy. To address this problem, we re-conduct the regression of Model (3) and Model (4) after excluding the sample during the period of three days before and after the implementation of the lockdown policy,14 which is shown in Panel A of Table 8.

Table 8.

Robustness check on lockdown policy.

|

Panel A: Excluding the sample around the implementation date of lockdown policies | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables |

|

|

||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| 15.069 * ** | 8.169 * ** | |||

| (1.709) | (1.138) | |||

| 14.049*** | 12.336*** | |||

| (3.985) | (2.798) | |||

| 26.336*** | 12.239*** | |||

| (3.977) | (2.207) | |||

| 13.144*** | 6.466*** | |||

| (2.004) | (1.323) | |||

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| City Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Date Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | 104.629*** | 104.561*** | 90.208*** | 90.175*** |

| (2.560) | (2.560) | (1.894) | (1.894) | |

| Observations | 13,583 | 13,583 | 13,583 | 13,583 |

| R-squared | 0.834 | 0.834 | 0.838 | 0.838 |

| Panel B: Using the forward variable of sleeplessness | ||||

| Variables | ||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| 16.680*** | 10.030*** | |||

| (1.706) | (1.118) | |||

| 10.994*** | 9.535*** | |||

| (3.959) | (2.828) | |||

| 29.206*** | 15.850*** | |||

| (3.923) | (2.116) | |||

| 15.598*** | 9.006*** | |||

| (2.020) | (1.308) | |||

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| City Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Date Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | 115.924*** | 115.892*** | 99.320*** | 99.285*** |

| (2.600) | (2.600) | (1.941) | (1.941) | |

| Observations | 12,701 | 12,701 | 12,701 | 12,701 |

| R-squared | 0.838 | 0.838 | 0.843 | 0.843 |

Notes: This table reports the robustness of the impact of lockdown policy. Panel A presents the results of excluding the sample around the implementation date of lockdown policy. In Panel B, we use the five-day forward sleeplessness to investigate the effect of lockdown policies on sleeplessness level of city. Other variables are measured are defined in Appendix A. Robust standard errors are reported in parentheses. Significance at 10%, 5%, and 1% levels was indicated by * , * *, and * ** , respectively.

In Panel A, we find that no matter the degree of lockdown policies, sleeplessness in a city appears a significantly increase after implementing lockdown policies. To further identify the impact of the lockdown policy on sleeping, we use the five-day forward sleeplessness () to re-conduct the regression. Panel B in Table 8 reports the related results. When using forward sleeplessness variables, we find that the effect of lockdown policies also have lasting and significate influence on sleeping in a city, which is consistent with baseline results.

4.2.4. Heterogeneity

The previous section shows that the lockdown policy could increase sleeplessness. Extensive literature has emphasized a substantial heterogeneity in the city characteristics across China, thereby possibly having crucial implications for our previous findings. Thus, we explore whether the heterogeneity of city's connection with Wuhan, citizen's attitude to anxiety mood could affect the response to lockdown policies.

First, we capture a city's connection with Wuhan by the daily between-city migration data related to Wuhan from January 1, 2020 to February 29, 2020 from the Baidu Migration data.15 The Baidu Migration data is based on real-time location records for every smart phone using the Baidu Map app or other apps imbedding the Baidu Map Software Development Kit, thereby precisely reflecting population movements. For each city in China, Baidu Migration provides the top 100 origination cities for the population moving into this city, and the top 100 destination cities for population in this city moving out. We choose the daily in-migration index of each city, and define Connection as the percentage of inflow population from Wuhan. Based on the daily median of Connection, we divide all samples into two groups to estimate the impact of lockdown policy on sleeplessness. Panel A of Table 9 presents the effect of connections with Wuhan on the utility of lockdown policy.

Table 9.

Heterogeneity.

| Variables |

|

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (1) | |

| Panel A: Connections with Wuhan | ||||

| High | Low | High | Low | |

| 12.014*** | 2.896 | 6.430*** | 0.493 | |

| (2.110) | (2.811) | (1.290) | (2.242) | |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| City Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Date Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 6899 | 6958 | 6899 | 6958 |

| R-squared | 0.840 | 0.598 | 0.857 | 0.599 |

| Panel B: Anxiety | ||||

| High | Low | High | Low | |

| 13.035*** | 2.739 | 7.033*** | 1.983 | |

| (2.129) | (2.734) | (1.286) | (2.231) | |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| City Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Date Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 6245 | 7582 | 6245 | 7582 |

| R-squared | 0.837 | 0.547 | 0.867 | 0.551 |

Notes: This table reports the heterogeneity of the impact of lockdown policy. Panel A reports the results of connections with Wuhan on the utility of lockdown policy. We use the daily median of Connection to divide the sample into two groups. Panel B reports the results of citizen's anxiety mood on the utility of lockdown policy. According to the daily median of Anxiety, we partition all sample into two subsamples. The key independent variable is Treat*Post. All variables are measured are defined in Appendix A. Robust standard errors are reported in parentheses. Significance at 10%, 5%, and 1% levels was indicated by *, **, and ***, respectively.

Second, we capture the people's anxiety mood by using search index of mask and N95. We collect the search quantity of words related to mask from the Baidu Index. If one searches for mask, a feeling of anxiety will be the outcome because mask is important and scarce during these early days of the outbreak. And the terrible consequence of COVID-19 disease would make you feel the more fear about it. Therefore, the aggregate search frequency is a good proxy of anxiety mood. Referring to Liu, Kong, and Kong (2020), we define Anxiety as the search index on (N95) mask in the corresponding city, and divide all samples into two groups by the daily median of Anxiety, to estimate the impact of lockdown policy on sleeplessness. Panel B of Table 9 reports the regression results.

Table 9 compares the locked down cities in 2020 to those not on lock down in 2020, and present the results with weather conditions and fixed effects. Columns (1) and (3) of Panel A show that the coefficients of are significantly positive, suggesting that the connection with Wuhan significantly increases the utility of lockdown policies on sleeplessness in the city. This result demonstrates that the negative effect of lockdown policies on sleep quality would be significantly increased within cities, where more inflow population comes from Wuhan. Panel B shows that the coefficients of are significantly positive in more anxiety mood, revealing that the anxiety mood would make people markedly sleepless, thereby significantly increasing the utility of lockdown policies on sleeplessness. This situation demonstrates that the negative effect of lockdown policies would be the more serious and significant within cities where citizens experience considerable anxiety owing to the supply of mask.

In summary, we find that the utility of lockdown policies on city sleeplessness would be the higher in cities where more people are connected to Wuhan, or more people in anxiety.

4.3. Effects of Lockdown policy and COVID-19

In this section, we use the following specification to study the joint impact of COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown policies on sleeplessness.

| (6) |

where i denotes the city and t denotes the daily date. The dependent variable is a measure of sleeplessness in city i on day t. The key variable of the DID design is , which captures the joint impact of lockdown policies and COVID-19 cases in all cities.

Table 10 reports the regression results. We find that the coefficient of is significantly positive in all columns. These results suggest that the severity of COVID-19 pandemic significantly exacerbates the negative effect of lockdown policies on sleep in the city. Namely, when facing double pressure from increasing number of COVID-19 cases and lockdown policies, citizens in cities are more likely to have trouble falling sleep.

Table 10.

Effect of Lockdown Policy and COVID19 pandemic.

| Variables |

|

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| 11.691*** | 11.654*** | 8.569*** | 9.830*** | |

| (1.125) | (1.123) | (0.781) | (0.963) | |

| Control variables | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| City Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Date Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | 115.967*** | 101.596*** | 98.645*** | 88.842*** |

| (0.774) | (2.588) | (0.608) | (1.927) | |

| Observations | 13,858 | 13,858 | 13,858 | 13,858 |

| R-squared | 0.841 | 0.841 | 0.845 | 0.846 |

Notes: this table reports the joint effect of lockdown policy and COVID-19 on sleeplessness. The key independent variable is Treat*Post and Covid*Treat*Post. All variables are measured are defined in Appendix A. Robust standard errors are reported in parentheses. Significance at 10%, 5%, and 1% levels was indicated by * , * *, and * ** , respectively.

5. Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic has triggered enormous and heterogeneous global public health and economic crises. Except for direct somatic disorders and economics losses, the invisible loss caused by psychological disorders should not be disregarded. Anxiety and sleeplessness are becoming substantially serious under the threat of COVID-19 and enormous economic pressure. Moreover, sleep loss is a significant problem in China. Hence, evaluations related to sleep quality during the COVID-19 pandemic are particularly important.

This study contributes to the literature by exploring the effects of COVID-19 on sleeplessness in the level of Chinese cities. We use the COVID-19 cases and the lockdown policy from different cities as exogenous shocks in conducting OLS and DID estimation. Accordingly, we show that COVID-19 pandemic and the lockdown policy significantly result cities' citizens in getting trouble falling asleep, which probably owes to the fear for COVID-19 disease and the anxiety for corresponding economics loss. And the negative effect of lockdown policies would be more pronounced in cities where more people are connected to Wuhan, or more people in anxiety. Lastly, the severity of COVID-19 pandemic significantly exacerbates the negative effect of lockdown policies on sleep quality in the city. These results support that human beings feel enormous psychological pressure under the threat of COVID-19 pandemic.

Overall, by illustrating the negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on sleeplessness in Chinese cities, this study provides timely policy implications for policy makers. As important as physical health, the public sentiments and mental health should be much valued when important public health emergency is occurred. What' s more, policy makers should pay more and lasting attention to public mental health when citizens recover from COIVD-19, and take better into account the potential estrangement caused by lockdown policies between cities.

Declaration of Conflict of Interests

We, the authors of this paper, declare that: 1) we have no conflict of interest that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper, and 2) we have no competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

We thank Shiyi Chen (editor-in-chief), Hong Song (the associate editor), one anonymous referee, Rui Shen, Haijian Zeng, and seminar participants at Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan University, and Zhongnan University of Economics and Law for helpful suggestions. We also gratefully acknowledge the financial support from National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 71802061; 71772178). All errors are our own.

The US released a fiscal stimulus package of two trillion dollars at the end of March 2020 to distribute directly to residents, support small- and medium-sized enterprises, and fund hospitals. The European Commission announced the setting of a fund of 100 billion euros to offer loan for members where the pandemic is substantially serious.

S&P 500 implemented circuit breakers thrice in March 2020. Bartik et al. (2020) conducted a survey of over 5800 small businesses and find that 43% of businesses are temporarily closed. Ding et al. (2021) indicated that due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the average US manufacturing firm saw stock prices fall by 29% over the first quarter. Owing to the lockout of manufacturing, the supply of oil considerably exceeded the demand, thereby resulting in the negative values of future prices of crude oil for the first time.

The National Health Commission of China issued the report on preventing diseases and keeping healthy on July 15, 2019. The related report can be found at: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2019–07/15/content_5409694.html.

Weibo is the most popular social media platform in China, which has over 503 million registered and 313 million regular users among the 720 million Internet users in the country. Like Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, and YouTube, Weibo users can share what they see, hear, and think, and read the posts of others.

Based on Google search data on relevant keywords, Keane and Neal (2021) develop a measure of consumer panic and explore the volatility of panic index among different countries during the COVID-19 pandemic.

To suppress the spread of COVID-19, the central government of China imposed an unprecedented lockdown in Wuhan from 10 AM on January 23, 2020, and in other cities in Hubei Province several days later. As of February 29, 2020, 80 cities in 22 provinces have imposed different levels of lockdown policies, including completed lockdown, partial lockdown, and setting up checkpoints and quarantine zones.

Google had closed its search engine in China on March 23, 2010, including Google Search, Google News, and Google Images on Google.cn (Kong, Lin, Wei, & Zhang, 2022). Thus, Google Trend is not suitable for our research.

The user in Weibo (the most popular social media platform in China) are younger.

Ginsberg et al. (2009) find that the frequency of certain keywords in Google search engine is significantly related to the percentage of physician visits in which a patient presents with influenza-like symptoms.

Keane and Neal (2021) use Google search data on relevant keywords to capture the consumer panic during the COVID-19 pandemic.

We obtain 4.5% by multiplying 1.582 (the standard deviation of Covid) with 3.479 (the coefficient on Covid in column (2) of Table 2), which is divided by 121.8 (the mean of Sleeplessness). Similarly, we obtain 3.6% by multiplying 1.582 (the standard deviation of Covid) with 2.350 (the coefficient on Covid in column (4) of Table 2), which is divided by 102.5 (the mean of Sleeplessness1).

We also use other multi-year lagged sleeplessness variables to conduct the tests, and obtain consistent regression results.

We obtain 10.4% by 12.670 (the coefficient on Treat*Post in column (2) of Table 5), which is divided by 121.8 (the mean of Sleeplessness). Similarly, we obtain 6.7% by 6.856 (the coefficient on Treat*Post in column (4) of Table 5), which is divided by 102.5 (the mean of Sleeplessness1).

We have removed the sample during the period of five days before and after the lockdown policy, and obtain consistent results.

Appendix A. Variable Definitions

| Variable | Definition and Data Source |

|---|---|

| Sleeplessness | The search quantity of keywords about “Shimian” and “Shuibuzhao” by PC and smart phone ports from Baidu index, in city i on day t. Source: http://index.baidu.com |

| Sleeplessness1 | The search quantity of keywords about “Shimian” and “Shuibuzhao” by smart phone ports from Baidu index, in city i on day t. Source: http://index.baidu.com |

| Covid | The logarithm of the cumulative number of confirmed or death cases in city i on day t. Source: CSMAR |

| Wind Speed | The max wind speed (Km/h) in city i on day t. Source: China Meteorological Administration |

| Precipitation | The average precipitation (mm) in city i on day t. Source: China Meteorological Administration |

| Humidity | The average humidity (%) in city i on day t. Source: China Meteorological Administration |

| Temperature | The average temperature (◦C) in city i on day t. Source: China Meteorological Administration |

| PostWuhan | Equals one after Wuhan city issued their lockdown policy, or after January 23, 2020 for all cities, and zero otherwise. Source: http://www.hubei.gov.cn/ |

| Treat | Equals one if city i issues any lockdown policies in 2020, and Zero otherwise. Source: http://www.gov.cn/ |

| Post | Equals one for the sample period after city i issues any lockdown policies, and zero otherwise. Source: http://www.gov.cn/ |

| Completed Lockdown | Equals one if city i issues the completed lockdown policy in 2020, and Zero otherwise. Source: http://www.gov.cn/ |

| Partial Lockdown | Equals one if city i issues the partial lockdown policy in 2020, and Zero otherwise. Source: http://www.gov.cn/ |

| Checkpoint | Equals one if city i sets up checkpoints and quarantine in 2020, and Zero otherwise. Source: http://www.gov.cn/ |

| MultiTreat | Equals three if city i issued completed lockdown policy, two for city i issued partial lockdown policy, and one for city i set up checkpoints and quarantine zones. Source: http://www.gov.cn/ |

| Completed&Partial | Equals one if city i issues the completed or partial lockdown policy in 2020, and Zero if city i sets up checkpoints and quarantine in 2020. Source: http://www.gov.cn/ |

| Connection | The percentage of inflow population that comes from Wuhan in daily in-migration index of each city. Source: http://qianxi.baidu.com |

| Anxiety | The search quantity of keywords about mask and N95 by smart phone ports from Baidu index, in city i on day t. Source: http://index.baidu.com |

References

- Alexander D., Schnell M. Just what the nurse practitioner ordered. Journal of Health Economics. 2019;66:145–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2019.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartik, A.W., Bertrand, M., Cullen, Z.B., Glaeser, E.L., Luca, M., Stanton, C.T. (2020). How Are Small Businesses Adjusting to COVID-19?. NBER Working Paper No. 26989.

- Beck T., Levine R., Levkov A. Big bad banks? the winners and losers from bank deregulation in the United States. The Journal of Finance. 2010;65(5):1637–1667. [Google Scholar]

- Bilgin M.H., Demir E., Gozgor G., Karabulut G., Kaya H. A novel index of macroeconomic uncertainty for turkey based on google-trends. Economics Letters. 2019;184 [Google Scholar]

- Callaway B., Andrew G., Pedro S. Difference-in-differences with a continuous treatment. arXiv Preprint arXiv. 2021;2107:02637. [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Qian W., Wen Q. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on consumption: learning from high frequency transaction data. AEA Paper and Proceeding. 2021;111:307–311. [Google Scholar]

- Costola M., Iacopini M., Santagiustina C. Google search volumes and the financial markets during the covid-19 outbreak. Finance Research Letters. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.frl.2020.101884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding W., Levine R., Lin C., Xie W. Corporate immunity to the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Financial Economics. 2021;141(2):802–830. doi: 10.1016/j.jfineco.2021.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douven R., Remmerswaal M., Mosca I. Unintended effects of reimbursement schedules in mental health care. Journal of Health Economics. 2015;42:139–150. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2015.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang H., Wang L., Yang Y. Human mobility restrictions and the spread of the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in China. Journal of Public Economics. 2020;191 doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang J., Collins A., Yao S. On the global COVID-19 pandemic and China's FDI. Journal of Asian Economics. 2021;74 doi: 10.1016/j.asieco.2021.101300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsberg J., Mohebbi M.H., Patel R.S., Brammer L., Smolinski M.S., Brilliant L. Detecting influenza epidemics using search engine query data. Nature. 2009;457:1012–1014. doi: 10.1038/nature07634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen A., Bi P., Nitschke M., Ryan P., Pisaniello D., Tucker G. The effect of heat waves on mental health in a temperate Australian city. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2008;116(10):1369–1375. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyes A., Zhu M. Air pollution as a cause of sleeplessness: Social media evidence from a panel of Chinese cities. Journal of Environment Economics and Management. 2019;98 [Google Scholar]

- Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y.…Gu X., et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. The Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jie J., Hou J., Wang C., Liu H. COVID-19 impact on firm investment-Evidence from Chinese publicly listed firms. Journal of Asian Economics. 2021;75 doi: 10.1016/j.asieco.2021.101320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karaivanov A., Lu S.E., Shigeoka H., Chen C., Pamplona S. Face masks, public policies and slowing the spread of COVID-19. Journal of Health Economics. 2021;78 doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2021.102475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keane M., Neal T. Consumer panic in the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Econometrics. 2021;22(1):86–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jeconom.2020.07.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong D., Lin C., Wei L., Zhang J. (2022). Information Accessibility and Corporate Innovation. Management Science, forthcoming.

- Kuchler T., Stroebel J., Russel D. (2020). The geographic spread of covid-19 correlates with structure of social networks as measured by facebook. NBER Working Paper No. 26990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kung C.S.J., Johnston D.W., Shields M.A. Mental health and the response to financial incentives. Journal of Health Economics. 2018;62:84–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2018.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S., Kong G., Kong D. Effects of the COVID-19 on air quality: Human mobility, spillover effect, and city connections. Environmental and Resource Economics. 2020;76:635–653. doi: 10.1007/s10640-020-00492-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullins J.T., White C. Temperature and mental health: Evidence from the spectrum of mental health outcomes. Journal of Health Economics. 2019;68 doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2019.102240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura N., Suzuki A. COVID-19 and the intentions to migrate from developing countries. Journal of Asian Economics. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.asieco.2021.101348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen L., Hoang Dinh P. Ex-ante risk management and financial stability during the COVID-19 pandemic: a study of Vietnamese firms. China Finance Review International. 2021;11(3):349–371. [Google Scholar]

- Obradovich N., Migliorini R., Mednick S.C., Fowler J.H. Nighttime temperature and human sleep loss in a changing climate. Science Advances. 2017;3(5) doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1601555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]