Highlights

-

•

19.4% of healthcare students were hesitant to accept a COVID-19 vaccine with 66.6% reporting at least one concern with the vaccine.

-

•

Medical discipline, history of COVID-19 infection, perceived risk of contracting COVID-19, and perceived severity of illness if infected were predictive of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy.

-

•

Age, sex, and exposure to in-person clinical care were not predictive of vaccine hesitancy.

Keywords: COVID-19, COVID-19 vaccines, Vaccine hesitancy, Vaccination refusal, Health occupations students

Abstract

Introduction

Although the development of COVID-19 vaccines represents a triumph of modern medicine, studies suggest vaccine hesitancy exists among key populations, including healthcare professionals. In December 2020, a large academic medical center offered COVID-19 vaccination to 3439 students in medicine, nursing, dentistry, and other health professions. With limited vaccine hesitancy research in this population, this study evaluates the prevalence of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among healthcare students, including predictors of hesitancy and top concerns with vaccination.

Methods

The authors distributed a cross-sectional survey to all healthcare students (n = 3,439) from 12/17/2020 to 12/23/2020. The survey collected age, sex, perceived risk of contracting SARS-CoV-2 without vaccination, perceived impact on health if infected with SARS-CoV-2, vaccine hesitancy, and vaccine concerns. In 2021, logistic regressions identified risk factors associated with hesitancy.

Results

The response rate was 30.0% (n = 1030) with median age of 25.0. Of respondents, 19.4% were hesitant to accept COVID-19 vaccination, while 66.6% reported at least one concern with the vaccine. Medical discipline, history of COVID-19 infection, perceived risk of contracting COVID-19, and perceived severity of illness if infected were predictor variables of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy (p < 0.05). Age, sex, and exposure to in-person clinical care were not predictive of vaccine hesitancy.

Conclusions

Fewer students reported COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy than expected from surveys on the general public and on healthcare workers. Continued research is needed to evaluate shifting attitudes around COVID-19 vaccination among healthcare professionals and students. With COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy a growing concern in young adults, a survey of this size and breadth will be helpful to other academic medical centers interested in vaccinating their students and to persons interested in leveraging predictors of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy for targeted intervention.

Introduction

Uptake of COVID-19 vaccination is essential in efforts to end the COVID-19 pandemic. Vaccine hesitancy, particularly in key populations like healthcare workers, could be a primary barrier to success. Surveys of the American public estimate that 22–42.4% may be reluctant to accept vaccination [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], which is concerning when an estimated 60–80% of the population must be immune to achieve herd immunity [8], [9]. Additionally, with SARS-CoV-2 variants evolving to evade immunity, vaccinating the public has become increasingly urgent. Healthcare students play a key role in COVID-19 response and represent the next generation of front-line workers, making them critical components of vaccine efforts. However, there are limited data on how healthcare students will respond to an offered COVID-19 vaccine.

To date, studies assessing vaccine hesitancy among healthcare workers in the United States suggest hesitancy rates similar to or higher than the general public. In a September-October 2020 survey of 609 healthcare professionals in Los Angeles, 66.5% of respondents planned to delay vaccination [10]. In a survey of 13,000 nurses, 70% expressed hesitancy when asked if they would voluntarily accept vaccination against COVID-19 [11]. Although studies suggest COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy can be predicted by past influenza vaccine hesitancy, there are limited data on influenza vaccine hesitancy among healthcare students in the US [1], [4].

A growing body of knowledge provides insight into correlates of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the United States general public. Women and people who identify as Black or Hispanic report higher rates of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, though data for people of color may be confounded by decreased access to vaccination for these populations to date [2], [3], [4], [6], [12]. Additionally, lower levels of concern about contracting COVID-19 are also associated with hesitancy [2], [12]. Younger age and medical comorbidities are associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in some US studies but not others [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [12]. Respondents’ most common concern about COVID-19 vaccination is the accelerated development of vaccines leading to decreased vaccine safety [1], [3], [5], [6], [10], [12]. To our knowledge, there have been only three COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy surveys of healthcare workers in the United States, none of which included healthcare students [10], [11], [12]. Focused research on healthcare students is importance given their role in COVID-19 response and front-line risk.

In December 2020, a large academic medical center in Texas granting degrees in medicine, nursing, biomedical sciences, and other health professions, offered COVID-19 vaccination to all 4,000 students alongside its frontline faculty and staff. This effort provided the ideal setting to assess vaccine hesitancy among a diverse group of healthcare students. We conducted a cross-sectional, anonymous survey aimed to assess the degree of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among the healthcare students, to identify predictors of hesitancy, and to identify top concerns with the vaccine. These data provide insight for other academic medical centers interested in offering COVID-19 vaccines to their students. Additionally, identifying top concerns with the COVID-19 vaccine and predictors of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy will help guide targeted public health interventions aimed at vaccine hesitancy.

Methods

Context

Of 3439 enrolled students at the academic medical center, disciplines include: 875 in medicine, 562 in dentistry, 853 in nursing, 838 in health professions, and 311 in biomedical sciences [13]. Degree plans offered are: Professional (37.0%), Undergraduate (23.4%), Doctoral (21.1%), Masters (15.5%), and Postdoctoral Dental Specialty (3.1%) [13]. The institution is Hispanic-serving, with student racioethnic representation of: White (37.1%), Hispanic (34.8%), Asian (14.9%), Black or African American (5.2%), or Other/Unknown (8.1%). The majority of student enrollees were female (63.2%) [13]. Between December 12–21, 2020, all faculty and students were extended invitations to schedule COVID-19 vaccination. On December 17, 2020, the survey instrument was sent to the students.

Administration of the vaccine hesitancy survey occurred within a community COVID-19 surge. The percent positivity rate rose from 12.5% the week of December 12, 2020 to 23.2% the week of December 28, 2020 [14]. The rolling 7-day average of new COVID-19 cases per day increased 58% from 736 on December 1, 2020 to 1,164 on December 31, 2020 [14].

Survey design

Survey design was informed by a literature review on COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among healthcare professionals conducted in PubMed from December 7–8, 2020. The Health Belief Model, a theoretical model for predicting health behavior, informed survey design [15]. Race and ethnicity were omitted from the survey per institutional guidance to maintain anonymity because of low representation in some cohorts. A list of concerns related to COVID-19 vaccination were adapted from two other vaccine hesitancy surveys administered to healthcare workers in Israel and in Malta [16], [17]. Additional options reflected medical student concerns raised during a COVID-19 vaccine Q&A session conducted the week prior to survey distribution. The survey was reviewed and edited by leadership in student affairs, leadership in undergraduate medical education, and student peers for appropriateness and content validity.

Hesitancy outcome variables

Students offered vaccination prior to survey distribution were asked if they had accepted or planned to accept vaccination (Yes, No, Undecided). Students not yet offered vaccination were asked how likely they would be to accept vaccination when offered using a Likert scale of: Very likely, Likely, Undecided, Unlikely, Very Unlikely.

Predictor variables

Demographic variables included age, gender (male, female, other), and discipline. Other independent variables included: in-person clinical care within the next two months; previous COVID-19 diagnosis, and likert scales for perceived likelihood of contracting COVID-19 without vaccination, and perceived effect on health if infected with COVID-19. For perceived likelihood of contracting COVID-19, categories were assigned a numeric value, allowing for the calculation of mean risk scores for students from each discipline.

Data collection

The anonymous, web-based survey was administered using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN) and had an estimated completion time of 1–2 min. Responses to all survey questions were required to minimize incomplete data, but survey design did not prevent students from taking the survey more than once. The survey was distributed by email by the associate deans of students of each discipline. In total, the survey was emailed to approximately 3,439 students. The survey was live for one week, from December 17–23, 2020. All data was managed in the REDCap system.

Statistical analysis

Survey respondents were separated into two cohorts: those offered vaccination (N = 635) and not yet offered vaccination (N = 396). Two cohorts were needed as these individuals were in different stages of contemplation about the vaccine, with one group having an imminent choice to make an appointment and the other group considering a potential option in the future. Participant demographics were summarized with descriptive statistics.

For the cohort offered vaccination, the outcome variable (vaccine hesitancy) was dichotomized as follows. Students who declined the vaccine or who were “undecided” were classified as vaccine hesitant. A chi-square test was used to determine associations between vaccine hesitancy and categorical predictor variables: in-person clinical care within the next two months and previous COVID-19. Because of small, expected cell size, Fisher exact tests were used to determine associations between vaccine hesitancy and discipline, gender, perceived likelihood of contracting COVID-19 without vaccination, and perceived effect on health if infected with COVID-19. A Wilcoxon rank sum (Mann-Whitney) test was performed for the continuous predictor variable (age).

For the cohort not yet offered vaccination, the Likert Scale outcome variable (vaccine hesitancy) was dichotomized. Survey respondents who were “unlikely,” “very unlikely,” or “undecided” to accept the vaccine in the future were classified as vaccine hesitant. Respondents who were “Likely” or “Very Likely” to accept the vaccine in the future were classified as non-hesitant. A chi-square test was used to determine associations between vaccine hesitancy and categorical predictor variables: in-person clinical care within the next two months, previous COVID-19 diagnosis, and perceived effect on health if infected with COVID-19. Because of small, expected cell size, Fisher exact tests were used to determine associations between vaccine hesitancy and discipline, gender, and perceived likelihood of contracting COVID-19 without vaccination. A Wilcoxon rank sum (Mann-Whitney) test was performed for the continuous predictor variable (age).

Average perceived risk for contracting COVID-19 was compared across schools using ANOVA. Perceived risk scores were derived by assigning a numeric value to each response for the question about perceived likelihood of contracting COVID-19 (1-Low Risk to 4-High risk).

Vaccine hesitancy scores in both cohorts were dichotomized into hesitant or not, which did lose information about the extent of hesitancy. However, this dichotomization facilitated interpretable logistic models. Logistic regression models were created for each cohort to predict vaccine hesitancy based on predictor variables found to be significant at p < 0.05 in the bivariate associations. For logistic regressions, outcome variables were collapsed into binary variables as described previously. Statistical significance was based on a two-sided p-value of 0.05. All analyses were conducted in STATA 16.0 in Spring 2021 (College Station, TX).

Ethical considerations

This research was reviewed by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Texas Health Science Center San Antonio (Protocol HSC 20200916 N) and was determined to not meet the definition of human subject research on December 16, 2020.

Results

Characteristics of the cohort and vaccine hesitancy

Of the 3,439 enrolled students, 1,031 students completed the survey, providing a response rate of 30.0%. Response rates varied by discipline: Dentistry (16.7%), Health Professions (22.7%), Nursing (25.8%), Biomedical Sciences (39.9%), Medicine (46.0%). Medical school students were overrepresented in the sample, representing 39.1% of respondents but only 25.4% of enrolled students. Female students were also slightly overrepresented, representing 67.5% of respondents but only 63.2% of all students. The median age of respondents was 25.0 (IQR = 5.0). Most respondents reported no history of a prior COVID-19 diagnosis (94.6%), and 55.0% reported plans to work in direct patient care over the next 2 months.

Of all respondents, 19.4% expressed some degree of vaccine hesitancy (Table 1). Of students who had already been offered vaccination at the time of survey distribution, 15.8% expressed vaccine hesitancy, while 25.3% of students who had not yet been offered the vaccine expressed hesitancy. The difference in vaccine hesitancy among students who had already been offered the vaccination and those not yet offered vaccination was found to be statistically significant (p < 0.01). Nursing students reported the highest vaccine hesitancy rate at 29.1%. Table 1 includes vaccine hesitancy rates detailed by cohort, sex, discipline, in-person clinical involvement, history of COVID-19 illness, perceived risk of infection, and perceived severity of infection.

Table 1.

COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Student Survey Results.

| Characteristic (N) | Not Hesitant | Hesitant | Statistical test |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort 1: Offered vaccination (n = 635) | |||

| Response |

535 (84.3%) |

100 (15.7%) |

– |

|

Sex Female (4 1 3) Male (2 2 0) Other (2) |

346 (64.7%) 187 (35.0%) 2 (0.4%) |

67 (67.0%) 33 (33.0%) 0 (0.0%) |

p = 0.9281 |

|

Discipline Medicine (3 5 8) Dentistry (67) Nursing (1 2 9) Biomedical Sciences (21) Health Professions (60) |

323 (60.4%) 56 (10.5%) 96 (17.9%) 18 (3.4%) 42 (7.9%) |

35 (35.0%) 11 (11.0%) 33 (33.0%) 3 (3.0%) 18 (18.0%) |

p=<0.00011 |

|

Involved in the in-person clinical care of patients in the next 2 months Yes (4 3 0) No (2 0 5) |

362 (67.7%) 173 (32.3%) |

68 (68.0%) 32 (32.0%) |

p = 0.5992 |

|

History of COVID-19 Illness Yes (34) No (6 0 1) |

22 (4.1%) 513 (95.9%) |

12 (12.0%) 88 (88.0%) |

p = 0.0012 |

|

Perceived likelihood of contracting SARS-CoV-2 without vaccination Very unlikely (23) Unlikely (2 2 6) Likely (3 2 1) Very likely (65) |

13 (2.4%) 175 (32.7%) 285 (53.3%) 62 (11.6%) |

10 (10.0%) 51 (51.0%) 36 (36.0%) 3 (3.0%) |

p=<0.00011 |

|

Perceived effect on health if infected with SARS-CoV-2 Not affected (48) Mildly affected (3 5 5) Moderately affected (1 9 2) Severely affected (40) |

35 (6.5%) 299 (55.9%) 164 (30.7%) 37 (6.9%) |

13 (13.0%) 56 (56.0%) 28 (28.0%) 3 (3.0%) |

p = 0.0921 |

| Age | 535 (84.3%) | 100 (15.7%) | p = 0.2183 |

| Cohort 2: Not yet offered vaccination (n = 396) | |||

| Response | 296 (74.7%) | 100 (25.3%) | |

|

Sex Female (2 8 3) Male (1 1 1) Other (2) |

211 (71.3%) 85 (28.7%) 0 (0%) |

72 (72%) 26 (26%) 2 (2%) |

p = 0.0801 |

|

Discipline Medicine (44) Dentistry (27) Nursing (92) Biomedical Sciences (1 0 3) Health Professions (1 3 0) |

40 (13.5%) 20 (6.8%) 61 (20.6%) 81 (27.4%) 94 (31.8%) |

4 (4.0%) 7 (7%) 31 (31%) 22 (22%) 36 (36%) |

p = 0.0211 |

|

Involved in the in-person clinical care of patients in the next 2 months Yes (1 3 6) No (2 6 0) |

99 (33.4%) 197 (66.6%) |

37 (37%) 63 (63%) |

p = 0.5182 |

|

History of COVID-19 Illness Yes (22) No (3 7 4) |

16 (5.4%) 280 (94.6%) |

6 (6%) 94 (94%) |

p = 0.8222 |

|

Perceived likelihood of contracting SARS-CoV-2 without vaccination Very unlikely (12) Unlikely (1 4 7) Likely (2 0 6) Very likely (31) |

5 (1.7%) 95 (32.1%) 167 (56.4%) 29 (9.8%) |

7 (7%) 52 (52%) 39 (39%) 2 (2%) |

p=<0.00011 |

|

Perceived effect on health if infected with SARS-CoV-2 Not affected (36) Mildly affected (1 9 8) Moderately affected (1 2 8) Severely affected (34) |

14 (4.7%) 147 (49.7%) 107 (36.1%) 28 (9.5%) |

22 (22%) 51 (51%) 21 (21%) 6 (6%) |

p=<0.00012 |

| Age | 296 (74.7%) | 100 (25.3%) | p = 0.4453 |

Fisher’s exact test.

Chi-square test.

Wilcoxon rank-sum (Mann-Whitney) test.

Perceptions of risk and barriers to vaccine acceptance

The mean perceived risk score was calculated for each discipline. For the cohort offered vaccination, the mean risk scores were 2.63 ± 0.69 (Mean ± SD) for medical students, 2.76 ± 0.63 for dental students, 2.80 ± 0.75 for nursing students, 2.52 ± 0.81 for biomedical sciences students, and 2.65 ± 0.73 for health professions students. For the cohort not yet offered vaccination, the mean risk scores were 2.55 ± 0.66 for medical students, 2.78 ± 0.64 for dental students, 2.68 ± 0.77 for nursing students, 2.60 ± 0.63 for biomedical sciences students, and 2.66 ± 0.63 for health professions students. There were no statistically significant differences between mean risk scores of disciplines within either cohort.

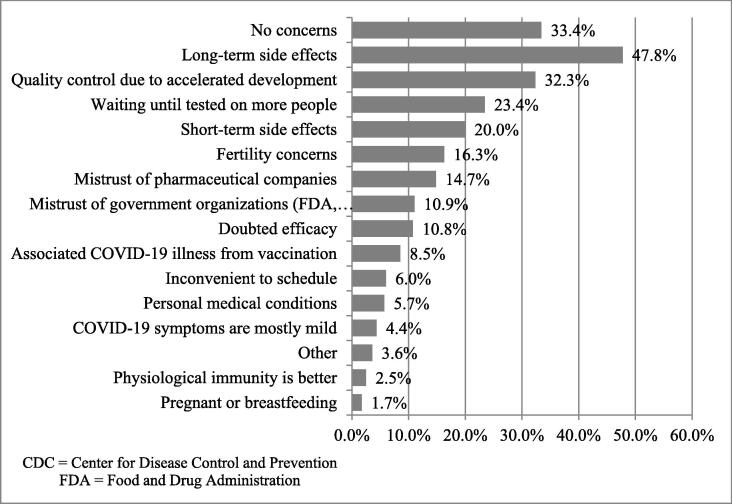

Of all students surveyed, 33.43% (345/1031) reported having no concerns with the COVID-19 vaccine. The other 66.57% (686/1031) of students reported their top five concerns to be long-term side effects, quality control due to accelerated development, waiting until tested on more people, short-term side effects, and mistrust of pharmaceutical companies (Fig. 1). For both cohorts, an ANOVA test was performed, which showed no statistical significance between a respondent’s total number of concerns and vaccine hesitancy.

Fig. 1.

Percent of Students Selecting Each COVID-19 Vaccine Concern (N = 1031).

Predictors of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy

For the cohort already offered vaccination, discipline, perceived risk of contracting COVID-19, and previous diagnosis of COVID-19 were all significant predictors of vaccine hesitancy (Table 2, p < 0.05). Students who perceived themselves as very unlikely to contract COVID-19 had significantly increased odds of vaccine hesitancy when compared with students who considered themselves very likely to contract COVID-19 (OR: 20.7, 95% CI: 4.70, 91.2). Students with a prior diagnosis of COVID-19 had significantly increased odds of vaccine hesitancy when compared to students who had not been previously diagnosed with COVID-19 (OR: 3.09, 95% CI: 1.36, 7.03). Medical students had the lowest rates of vaccine hesitancy, nursing and health professions students have significantly increased odds of vaccine hesitancy when compared with medical students. Dental students and biomedical science students did not have increased odds of vaccine hesitancy when compared with medical students.

Table 2.

Multivariable Logistic Regression Results with Associated Odds Ratios for Both Cohorts.

| OR | P-Value | CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort 1: Vaccine Hesitancy for Students Offered Vaccination | |||

|

Discipline Medicine Dentistry Nursing Biomedical Sciences Health Professions |

Ref 1.99 4.02 1.40 4.30 |

- 0.08 <0.001 0.61 <0.001 |

- 0.92, 4.31 2.30, 7.04 0.38, 5.15 2.15, 8.60 |

|

Perceived Risk of COVID-19 Very Likely Likely Unlikely Very Unlikely |

Ref 3.61 9.74 20.72 |

- 0.04 <0.001 <0.001 |

- 1.04, 12.56 2.80, 33.91 4.70, 91.22 |

|

Past COVID-19 Diagnosis No Yes |

Ref 3.09 |

- 0.01 |

- 1.36, 7.03 |

| Cohort 2: Vaccine Hesitancy for Students Not Yet Offered Vaccination | |||

|

Discipline Medicine Dentistry Nursing Biomedical Sciences Health Professions |

Ref 4.18 5.11 2.84 3.88 |

- 0.047 0.007 0.08 0.02 |

- 1.02, 17.14 1.57, 16.62 0.87, 9.28 1.23, 12.27 |

|

Perceived Risk of COVID-19 Very Likely Likely Unlikely Very Unlikely |

Ref 3.09 7.11 27.05 |

- 0.14 0.01 0.001 |

- 0.69, 13.86 1.56, 32.35 3.75, 194.92 |

|

Perceived Effect on Health from COVID-19 Severely Affected Moderately Affected Mildly Affected Not Affected |

Ref 0.96 1.19 4.57 |

- 0.94 0.73 0.01 |

- 0.34, 2.69 0.44, 3.18 1.44, 14.49 |

For the cohort not yet offered vaccination: discipline, perceived risk of contracting COVID-19, and perceived effect on health if infected with COVID-19 were significant predictors of vaccine hesitancy (Table 2, p < 0.05). Students who perceived themselves as very unlikely to contract COVID-19 had significantly increased odds of vaccine hesitancy when compared with students who considered themselves very likely to contract COVID-19 (OR: 27.1, 95% CI: 3.75, 194.92). Students who believed their health would be unaffected by COVID-19 infection had significantly increased odds of vaccine hesitancy when compared to students who believed their health would be very affected by COVID-19 infection (OR: 4.57, 95% CI: 1.44, 14.49). Dental, nursing, and health professions students had significantly increased odds of vaccine hesitancy when compared with medical students, but biomedical science students did not.

Age, sex, and the in-person clinical care of patients within the next two months were not statistically significant for either cohort.

Discussion

These data on COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy from over 1,000 students across health science disciplines demonstrate a reassuringly low level of vaccine hesitancy and 19.4%. However, key barriers to vaccination are identified that can provide insight on the concerns and factors influencing vaccine hesitancy among students. The majority of students expressed concerns regarding vaccination, the most common of which were: long-term side effects, quality control due to accelerated development, and waiting until tested on more people. Significant predictors of vaccine hesitancy varied slightly between those already offered vaccination and those awaiting vaccination, but discipline and low perceived likelihood of contracting COVID-19 without vaccination were consistent predictors of hesitancy across both cohorts. Age, sex, and the in-person clinical care did not have an association with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in either cohort. These findings suggest that programs wishing to address vaccine hesitancy among healthcare students may wish to design program-specific messaging that addresses vaccine side effects, development processes, and likelihood of COVID infection.

Vaccine hesitancy in our study is either comparable to or more encouraging than prior studies among healthcare professionals [10], [11], [12]. In late December 2020, a vaccine hesitancy survey at a children’s hospital in Chicago found a comparable vaccine hesitancy rate of 18.9% among their clinical and non-clinical staff [12]. Surveys through social media have found COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy rates among the US general public to be declining from 60.7% in September 2020 to 23.7% in March 2021, the Chicago study and our own suggest that rates of vaccine hesitancy among healthcare professionals and students may be lower than the general population [7], [12]. This may represent a shift in attitude. Prior to mid-November, hesitancy surveys addressed the possibility of a safe and effective vaccine, while surveys after this timeframe address COVID-19 vaccines with published data and federal approval. Our finding that vaccine hesitancy rates differed greatly between those who offered vaccination (15.8%) and those not yet offered vaccination (25.3%) is interesting since the mean perceived risk scores for both cohorts were nearly equivalent (2.68 for those offered vs. 2.65 for those not yet offered). Students who had not yet been offered the vaccine may also have not yet prioritized learning about vaccine safety and efficacy.

Consistent with other studies, the most commonly reported concerns in our study were related to vaccine safety, with fewer concerns related to vaccine efficacy [1], [3], [5], [6], [10], [12]. The misinformation that mRNA vaccines were linked with infertility also proved important in our population. These results affirm the need for continued assessment of vaccine concerns and local, context-specific belief patterns to inform vaccine hesitancy interventions. Additionally, identification of key concerns with COVID-19 vaccination can inform more effective vaccine information campaigns addressing specific misconceptions with aims to restore trust in vaccine safety.

As expected by the Health Belief Model, lower perceived COVID-19 threat was found to predict vaccine hesitancy. Respondents who perceived themselves as lower risk of contracting COVID-19 or who believed their health would not be affected by COVID-19 infection were more likely to express vaccine hesitancy. These findings are consistent with other studies identifying higher levels of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among respondents who reported no or low concerns with COVID-19 infection [2], [12]. Perceived severity of COVID-19 infection was shown to influence vaccine hesitancy in the cohort of students who were not yet offered vaccination.

There were notable differences in our findings of predictors of vaccine hesitancy compared with other studies. In contrast to most US studies assessing predictors of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, our results found sex did not significantly impact COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy [2], [3], [4], [6], [12]. While one study identified nonclinical staff as more vaccine hesitant than clinical staff, in-person clinical care was not a significant predictor of vaccine hesitancy in this survey [12]. Students with a past COVID-19 diagnosis were significantly more likely to report vaccine hesitancy compared with those not diagnosed with COVID-19. This predictor has not been assessed in prior studies, and may be influenced by perceptions of natural immunity conferred by past COVID-19 infection. This perception may change as more information becomes available comparing the natural versus vaccinated immunity and as CDC and ACIP recommendations strengthen regarding vaccination for those with prior infection [18].

Discipline was found to significantly predict vaccine hesitancy in both cohorts. When controlling for other significant confounding variables, perceived risk of COVID-19 infection, previous COVID-19 diagnosis, and perceived severity of COVID-19 infection did not significantly impact discipline’s effect on vaccine hesitancy. Nursing students reported the highest vaccine hesitancy rate at 29.10%, which is consistent with other studies showing that nurses have more COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy than other healthcare professionals [10], [16]. Given that nurses serve as critical frontline workers with significant direct patient contact, the high rates of vaccine hesitancy among nursing students has serious public health implications.

Though this survey achieved broad representation across health science disciplines, it is a single site study, which may affect generalizability of results. The survey response rate was 30%, yet the respondents were relatively well distributed across the student body and was higher than anticipated considering the survey was distributed by email before a break in the academic calendar. By making each survey question required, incomplete surveys were discarded at the expense of response rate. Response bias, particularly regarding acceptability, was likely influential in our sample, and the survey was anonymous to reduce acceptability bias. The statistical analysis dichotomized the vaccine hesitancy predictor variables with Likert scale responses, leading to some decrease in the specificity of the test but an increase in power. Finally, because some students had been offered vaccines and others had not yet, hesitancy questions were different for each cohort, which limited our ability to combine data for all students.

Conclusions

This investigation provides important and novel data to address COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in a key population, health care students, who are both front line workers themselves and represent the future healthcare work force. There are also ethical considerations that healthcare students, with increasing responsibility for patient safety and health, assume personal responsibility to mitigate risk of hospital-acquired SARS-CoV-2 transmission as much as possible. With a survey of this size and breadth across health care disciplines, this information may be helpful to other academic medical centers interested in vaccinating their students, or for anyone interested in understanding predictors of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among healthcare students. Since this survey was administered in the initial weeks of COVID-19 vaccine distribution under Emergency Use Authorization in the United States, we suspect vaccine hesitancy will continue to evolve as people begin to hear first-hand accounts from vaccine recipients in their community and as more safety data are released. Since all respondents had access to the vaccine through the academic medical center, our results may be more generalizable as vaccine access continues to increase. Based on our findings, public health campaigns aimed at addressing COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among students in health career programs should focus on safety concerns, as these were the top concerns identified. Additionally, efforts to minimize COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy at academic medical centers should focus on nursing students and health professions students, with specific focus on students who consider themselves low risk for infection. Ongoing vaccine hesitancy surveys will be needed to confirm a positive shift in attitude towards COVID-19 vaccination among healthcare workers as COVID-19 vaccinations become more common and as new information continues to emerge.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the University of Texas Health San Antonio COVID-19 Vaccine Assessment and Access Task Force and the Office of Undergraduate Medical Education for their support of this study. Special thanks to Dr. Patrick Ramsey and Dr. Joshua Hanson for their review of the manuscript and to the student body for taking the time to respond to the survey.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Ethics approval

This research was reviewed by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Texas Health Science Center San Antonio (Protocol HSC 20200916 N) and was determined to not meet the definition of human subject research on December 16, 2020. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1.Fisher K.A., Bloomstone S.J., Walder J., Crawford S., Fouayzi H., Mazor K.M. Attitudes Toward a Potential SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine: A Survey of U.S. Adults. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(12):964–973. doi: 10.7326/M20-3569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khubchandani J., Sharma S., Price J.H., Wiblishauser M.J., Sharma M., Webb F.J. COVID-19 Vaccination Hesitancy in the United States: A Rapid National Assessment. J Community Health. 2021;46(2):270–277. doi: 10.1007/s10900-020-00958-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nguyen K.H., Srivastav A., Razzaghi H., Williams W., Lindley M.C., Jorgensen C., et al. COVID-19 Vaccination Intent, Perceptions, and Reasons for Not Vaccinating Among Groups Prioritized for Early Vaccination - United States, September and December 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(6):217–222. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7006e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruiz J.B., Bell R.A. Predictors of intention to vaccinate against COVID-19: Results of a nationwide survey. Vaccine. 2021;39(7):1080–1086. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pogue K., Jensen J.L., Stancil C.K., Ferguson D.G., Hughes S.J., Mello E.J., et al. Influences on attitudes regarding potential covid-19 vaccination in the united states. Vaccines. 2020;8(4):582. doi: 10.3390/vaccines8040582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Latkin C.A., Dayton L., Yi G., Colon B., Kong X. Mask usage, social distancing, racial, and gender correlates of COVID-19 vaccine intentions among adults in the US. PLoS One. 2021;16(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246970. e0246970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MIT COVID-19 Survey. https://covidsurvey.mit.edu/. Accessed March 10, 2021.

- 8.Kadkhoda K. Herd Immunity to COVID-19. Am J Clin Pathol. 2021;155(4):471–472. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/aqaa272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson R.M., Vegvari C., Truscott J., Collyer B.S. Challenges in creating herd immunity to SARS-CoV-2 infection by mass vaccination. Lancet. 2020;396(10263):1614–1616. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32318-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gadoth A, Martin-Blais R, Tobin NH, et al. Assessment of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among healthcare workers in Los Angeles. medRxiv. November 2020:2020.11.18.20234468. doi:10.1101/2020.11.18.20234468.

- 11.American Nurses Foundation. Pulse on the Nation’s Nurses COVID-19 Survey Series: COVID-19 Vaccine. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/work-environment/health-safety/disaster-preparedness/coronavirus/what-you-need-to-know/covid-19-vaccine-survey/. Accessed December 22, 2020.

- 12.Kociolek L.K., Elhadary J., Jhaveri R., Patel A.B., Stahulak B., Cartland J. Coronavirus disease 2019 vaccine hesitancy among children’s hospital staff: A single-center survey. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2021;42(6):775–777. doi: 10.1017/ice.2021.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dashboards - UT Health San Antonio. https://wp.uthscsa.edu/data/dashboards/. Accessed March 10, 2021.

- 14.Takeaways K. COVID-19 Monthly Epidemiological Report I. Current Status and Overview of COVID-19 in Bexar County.; 2020.

- 15.Green E.C., Murphy E. The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Health, Illness, Behavior, and Society. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; Chichester, UK: 2014. Health Belief Model; pp. 766–769. doi:10.1002/9781118410868.wbehibs410. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dror A.A., Eisenbach N., Taiber S., Morozov N.G., Mizrachi M., Zigron A., et al. Vaccine hesitancy: the next challenge in the fight against COVID-19. Eur J Epidemiol. 2020;35(8):775–779. doi: 10.1007/s10654-020-00671-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grech V., Gauci C., Agius S. Vaccine hesitancy among Maltese Healthcare workers toward influenza and novel COVID-19 vaccination. Early Hum Dev. 2020:105213. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2020.105213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Interim Clinical Considerations for Use of COVID-19 Vaccines | CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/info-by-product/clinical-considerations.html. Accessed April 5, 2021.