Abstract

In rodents, repeated single-bottle exposures to distinctly flavored isocaloric glucose and fructose solutions, two sugars with different metabolic pathways, eventually lead to a preference for the former. Because Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) surgery decreases preference for and intake of sugar solutions in rats, we tested whether RYGB would curtail the conditioning of a preference for a glucose-paired vs. fructose-paired flavor. RYGB (♂ n=11; ♀ n=10) and sham-operated (SHAM; ♂ n=9; ♀ n=10) rats were trained with a single bottle (30 min/day) containing 8% glucose solution flavored with either 0.05% grape or cherry Kool-Aid (Glu/CSG) or 8% fructose solution with the alternative Kool-Aid flavor (Fru/CSF) in an alternating fashion for 8 days. To determine baseline preferences, a 4-day 30-min two-bottle test was used to assess preference for Glu/CSG vs. Fru/CSF before training. After training, 2-day 30-min two-bottle tests assessed preference for the a) Glu/CSG (CSG-flavored 8% glucose solution) vs Fru/CSF (CSF-flavored 8% fructose solution), b) CSG- vs. CSF-flavored mixture of 4% glucose & 4% fructose (isocaloric), c) CSG- vs. CSF-flavored 0.2% saccharin (“sweet”, no calories), and d) CSG- vs. CSF-flavored water. During training, only male SHAM rats demonstrated progressively increased intake of Glu/CSG over Fru/CSF, and female SHAM rats displayed a trend. RYGB eliminated any difference in single-bottle intake of these solutions during training, regardless of sex. Like their male and female SHAM counterparts, male RYGB rats displayed a conditioned preference for the CSG-associated stimulus in Tests 1-3. Although female RYGB rats displayed acquisition of the conditioned flavor preference in Test 1, unlike the other groups, when the differential sugar cue between the two solutions was removed in Tests 2 and 3, female rats did not display a CSG preference. When the sugar and sweetener cues were both removed on Test 4, all groups displayed some generalization decrement. Thus, RYGB does not compromise the ability of rats to learn and express a glucose- vs. fructose-associated conditioned flavor preference when the exact CS used in training is presented in testing. The mechanistic basis for the sex difference in the effect of RYGB on the generalization decrement observed in this type of flavor preference learning warrants further study.

Keywords: Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, conditioned flavor preference, glucose, fructose, sex difference, generalization decrement

1. Introduction

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) surgery is one of the most effective ways to reduce body weight in patients with obesity as well as treating related comorbidities such as type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) [1-4]. This bariatric surgery produces broad physiological changes [5-7] including a pleiotropic endocrine response [8], and alterations in: gastric emptying [9], bile acid levels and receptors [10], gut microbiota [11], and energy expenditure and body composition [12-15]. It is widely believed that RYGB also changes relative macronutrient intake and food selection, especially for sugary and fatty foods [16-25]. In humans, however, recent studies using direct measures of food choice and intake have failed to confirm such behavioral changes other than reduced caloric intake, and so the question remains open as to how robust and consistent RYGB-induced alterations in food preferences are [26, 27]. In contrast, when given a choice between laboratory chow and a diet high in fat, rats that have RYGB will display significantly lower preferences for the latter compared with sham-operated controls. It has also been commonly observed that RYGB reduces the relative intake of fat and sugar solutions in drinking tests [28-31]. The decreases in sucrose and Intralipid preference by RYGB rats across a broad range of concentrations in 48-hr two-bottle tests is not observed for other prototypical taste compounds such as quinine (“bitter”), citric acid (“sour”), or NaCl (“salty”) solutions in 48-hr two-bottle tests [28, 29].

Some have argued that these changes in intake and preference are driven by the reduced taste-related palatability of these calorically dense foods, because RYGB rats will sometimes decrease their licking of fat and sugar solutions, at least at high concentrations, in brief access tests [32, 33]. Moreover, relative to their sham-operated counterparts, some investigators have reported that RYGB rats decrease their ingestive oromotor taste reactivity behavior elicited by 1.0 M sucrose; this measure of consummatory behavior is thought to reflect stimulus palatability [33].

On the other hand, some studies have found no effect of surgery on concentration-dependent licking to fat emulsions, sucrose, or glucose [29, 31, 34]. Even when RYGB rats display reduced preference for and/or intake of caloric solutions relative to sham-operated controls, when these stimuli are used as reinforcers in a progressive ratio task, this surgery has no effects on the breakpoints observed [30]. Moreover, the results from a microstructural analysis of licking during a liquid meal of a sugar or fat solution suggest that the decreased intake observed is not due to a blunting of the motivational potency of the taste of these stimuli [35].

Importantly, there is evidence that, under some conditions, those changes in intake and preference that are induced by RYGB in rats are progressive and grow with repeated test experience [30, 35-40]. Such findings suggest that learning processes may be influencing the ingestive behavior of patients and animal subjects after RYGB surgery. Indeed, a 1 ml oral gavage of corn oil after a short ingestive bout of a novel saccharin solution in RYGB rats subsequently led to a pronounced decrease in saccharin preference relative to water, a consequence that was not observed in sham-operated rats or in a group of RYGB rats that received gavage of saline instead of corn oil [29]. These studies demonstrate that RYGB rats are capable of forming a conditioned avoidance of a taste that was paired with the postoral consequences of fat digestion. This raises the question of whether RYGB rats are capable of displaying conditioned flavor preferences.

In numerous studies, largely conducted by Sclafani and his colleagues ([41-45]), when glucose ingestion is repeatedly paired with a novel flavor (often Kool-Aid), rodents will eventually develop a preference for the glucose-paired flavor compared with either a water-paired flavor or even a fructose-paired flavor [44, 46, 47]; fructose is apparently an ineffective unconditioned stimulus in such learning because many of its apparently relevant postoral consequences differ from those of glucose [48, 49]. Given that after RYGB, rats decrease their intake of sucrose and glucose solutions relative to controls, it remains to be seen if glucose can still serve as an unconditioned stimulus to promote flavor preference learning considering that ingestants bypass most of the stomach, the duodenum, and the proximal jejunum. Although it is true that glucose infused into the jejunum in intact animals while animals are drinking noncaloric flavored solutions is effective at conditioning a flavor preference [50], rats with RYGB have a permanent change in the anatomy of and nutrient flow through the gut. Indeed, under certain testing circumstances rats with RYGB demonstrate reduced preferences for sugar solutions relative to sham-operated controls [28, 30, 31, 33]. Accordingly, here, we adapted and applied a paradigm developed by Sclafani and his colleagues to assess whether RYGB would curtail the ability of rats to form a conditioned preference for a flavor paired with glucose versus a flavor paired with fructose [41] .

2. Materials & methods

2.1. Animals

Sprague-Dawley rats served as subjects (female, n = 28; male, n = 28). All rats were housed individually in a cage in rooms where temperature, humidity, and lighting (12-hr on/off; lights on at 7:00 AM) were controlled. The rats received ad libitum access to standard chow (PMI 5001, LabDiet, St. Louis, MO) and deionized water except where noted. Stainless steel toys (Rattle-Round, Otto Environmental) were provided for environmental enrichment. All procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Florida State University.

2.2. Experimental design

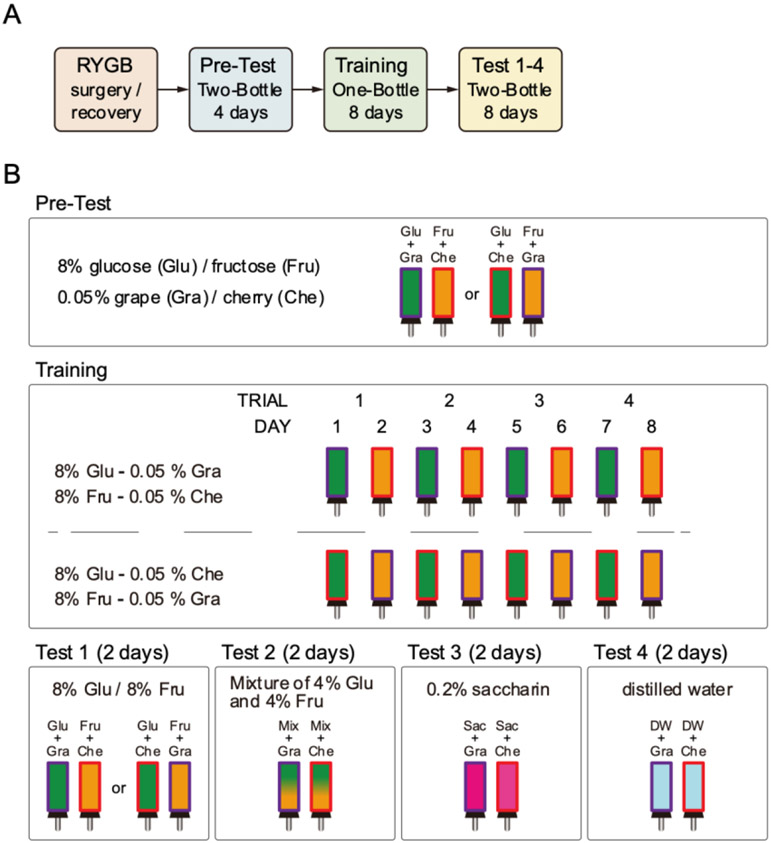

The general scheme of the experiment is depicted in Figure 1. Male and female rats received RYGB or sham (SHAM) surgery (see below) and then were presented with a 30-min two-bottle Pre-Test over 4 days to determine their baseline preference for a Kool-Aid flavor (either grape or cherry) mixed with 8% glucose when pitted against the other Kool-Aid flavor mixed with 8% fructose. The rats were then presented with four days of 30-min one-bottle training trials with an 8% glucose solution containing either grape or cherry Kool-Aid flavoring (conditioned stimulus with glucose; Glu/CSG) interspersed with four days of 30-min one-bottle training trials with an 8% fructose solution containing the alternative Kool-Aid flavor (conditioned stimulus with fructose; Fru/CSF) over a total of 8 trials presented across 8 consecutive days. After the training, we assessed the preference learning with a series of 30-min two-bottle tests. All of these tests (Pre-Test, Training, Tests) were conducted at 11:00 AM during the lights on phase and with relatively non-deprived rats (food and water were removed just before the training and test fluid presentations and replaced 1 hour after the session).

Figure 1.

Schedule of experiments. A) Flow of experiment. B) Procedures of Pre-Test, Training, and Test. The solution(s) were presented for 30 min in a day. Food and water were removed from the home cage during the presentation and for the following 1 hour. Animals were assigned to be exposed to either of glucose-grape and fructose-cherry or glucose-cherry and fructose-grape in a balanced fashion. In both cases, the glucose and fructose solutions were defined as Glu/CSG and Fru/CSF respectively. Each stimulus was presented every other day on training. The stimulus order was counterbalanced in each group (RYGB and SHAM).

2.3. Surgery

The rats that received RYGB surgery were given iron supplementation (2.5 mg/kg iron dextran, s.c.; Henry Schein, Inc.) once a week starting several weeks before surgery to the end of all experiments, while the rats that received sham operation were also given iron injections on the same schedule as the RYGB presurgically but were then switched postsurgically to injections of 0.9% saline (4 ml/kg, s.c.) instead of the iron. This is a procedure adopted and successfully used by our laboratory to preclude the anemia that sometimes develops in rats after RYGB [31, 34-36]. The iron injections were ceased postsurgically for the SHAM animals because these animals are not at risk of developing anemia and we wanted to preclude the potential for iron toxicity. A couple days before surgery, the rats were moved to a new cage equipped with a raised stainless-steel mesh floor and lined with an absorbable thin cardboard pad that would be used during recovery days to habituate them to this environment. This cage was designed to prevent the ingestion of regular wood chip bedding, which could lead to esophageal congestion and subsequent leakage from the gastrojejunostomy. During the habituation, the rats were given a gel diet (a mixture of starch, oil, vitamin, iron, water, protein) that would be provided during the recovery days. On the evening of the day before the surgery, the rats were moved to a new cage with a new cardboard pad and left with ~8 g of CHOW to minimize postsurgical hunger. Deionized water remained available ad libitum.

For RYGB surgery (female, n = 18; male, n = 19), rats were placed under isoflurane anesthesia (2–5% delivered in 1 L/min O2) and the small intestine was transected ~15 cm from the pylorus and the ends tied off with 5–0 PDSII suture (Ethicon), creating two stumps. A small incision was made in the proximal stump to create the biliopancreatic limb. A side-to-side anastomosis was created with a similarly sized incision in the small intestine positioned ~25 cm oral of the cecum using 7–0 PDSII suture (jejunojejunostomy). Next, the stomach was transected close to the esophageal junction, preserving no more than 3 mm of the stomach; the remaining stomach was closed with 5–0 PDSII sutures. A small incision was made to create the alimentary limb in the distal stump of the transected portion of jejunum initially. An end-to-side anastomosis with the stomach wall was created using 7–0 PDSII suture (gastrojejunostomy). For the sham operation (SHAM; female, n = 10; male, n = 9), stitches were placed at the sites of the intestinal transection and the jejuno-jejunostomy, and along the front wall of the stomach. After either surgery, the abdominal muscle wall was closed in one layer with PDSII 5–0 suture, and the skin was closed with Vicryl 4–0 suture (Ethicon). Each rat was injected with a fluoroquinolone antibiotic (enrofloxacin, Henry Schein, Inc., Melville, NY; 2.3 mg/kg s.c.), the analgesic carprofen (Rimadyl, Zoetis Inc., Parsippany, NJ, USA; 5 mg/kg s.c.) and with sterile saline (0.9%; 7–10 ml s.c.), and once recovered from anesthesia was returned to its home cage without food overnight to prevent rupture of the sutures. Deionized water was provided ad libitum.

For three days following surgery, each animal received enrofloxacin and carprofen (as above). The day after surgery, the rats were presented with supplemental diets. The density and hardness of the supplemental diets offered shifted from the very thin mash (a mixture of powdered chow with distilled water), to thin mash, to gel diet, to both gel diet and thin mash, followed by both gel diet and powdered chow, to only the powdered chow, and to a piece of a crushed pellet. The purpose of these diets was to prevent obstructions and promote recovery of the anastomoses. In some cases, rats would display drooling, and when this occurred, the animal was returned to an earlier step in the supplemental diet sequence until the drooling subsided. Eight female and eight male rats treated with RYGB surgery died or were euthanized during the surgery or the recovery period. Thus, twenty-one RYGB rats (female, n = 10; male, n = 11) and 19 sham-operated rats (female, n = 10; male, n = 9) were used in the behavioral experiments.

2.4. Stimulus

D-(+)-glucose (BDH9230, VWR International LLC., Radnor, PA, USA), D-(−)-fructose (F0127, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), and saccharin sodium salt hydrate (S6047, Sigma-Aldrich) were used as taste stimuli. The grape or cherry Kool-Aid (Kraft Foods Inc., Northfield, IL, USA) were dissolved in the taste solutions at the concentration of 0.05 % (w/v) and used as flavoring for the conditioned stimuli (CSs). The solvent for all fluid stimuli was deionized water.

2.5.1. Pre-Test and Training (Figure 1B)

When all RYGB rats showed stable maintenance of body weight, training started. Each rat was given a Pre-Test with two bottles; one contained 8% glucose solution flavored with either grape or cherry Kool-Aid (Glu/CSG) and the other contained 8% fructose solution with alternative Kool-Aid flavor (Fru/CSF). The Kool-Aid flavors used for the Glu/CSG and Fru/CSF were counterbalanced in each group (Female-RYGB, Female-SHAM, Male-RYGB, Male-SHAM). The two bottles were presented on the home cage for 30-min/day during the four days of the Pre-Test period. Each day the bottles were filled with fresh solutions and the left and right positions were switched. The average intake of the Glu/CSG solution over total intake (Glu/CSG and Fru/CSF) on the last two days of the four days of the Pre-Test period was taken as the initial baseline preference for the Glu/CSG before training began. Upon completion of the Pre-Test phase, Training began in which a single bottle containing either the Glu/CSG or Fru/CSF was presented in alternating fashion for 30 min/day. The Training phase lasted eight days with each stimulus presented four times. Immediately before each Pre-Test or Training session, both food and water were removed from the home cage and replaced one hour after the end of the presentation. Otherwise, the animals were non-deprived.

2.5.2. Two-Bottle Testing

Upon completion of the Training phase, Two-Bottle Testing began in which the rats received four different types of 2-day 30-min/day tests. In Test 1, one bottle contained the Glu/CSG and the other contained the Fru/CSF. In Test 2, a mixture of 4% glucose and 4% fructose was presented in both bottles, but one bottle contained the CSG Kool-Aid flavor and the other contained the CSF Kool-Aid flavor. In Test 3, a 0.2% saccharin solution was given in both bottles, but one bottle contained the CSG Kool-Aid flavor and the other contained the CSF Kool-Aid flavor. In Test 4, one bottle contained the CSG Kool-Aid flavor and the other contained the CSF Kool-Aid flavor dissolved in deionized water. Each day the bottles were filled with fresh solutions and the left and right positions switched. Immediately before the test session, both food and water were removed from the home cage and replaced one hour after the end of the presentation. Otherwise, the animals were non-deprived.

Test 1 aimed to examine whether the rats learned a preference for Glu/CSG over Fru/CSF. Test 2 evaluated the acquisition of preference for the Kool-Aid flavor associated with glucose over the alternative Kool-Aid flavor associated with fructose while keeping the solutions isocaloric with each other and with training. Moreover, any differential taste cues potentially provided by glucose and fructose were removed [51]. In Test 3, we removed the sugars (and calories) from the solutions while maintaining a “sweet” taste to evaluate the preference for the Glu/CSG versus Fru/CSF Kool-Aid flavors. Test 4 was designed to evaluate the preference for the CSG and the CSF Kool-Aid flavors alone in the absence of any additional taste or calories.

2.5.3. Data analysis

Body weight was analyzed as a percentage of the presurgical baseline and subjected to a three-way mixed repeated measures ANOVA (surgery x sex x day). Volume consumed was determined by weighing the bottles (assuming any difference in density between solutions to be negligible). The consumed volumes on the last two days of the Pre-Test were used as the baseline because intakes on the first two days were relatively lower for some of the groups than on the last two days (t-test: Female-SHAM, p < 0.001; Male-RYGB, p < 0.05; Male-SHAM, p < 0.01) and the last two days represented the most recent preference assessment before training. Preference scores on the Pre-Test and Two-Bottle Test sessions were calculated by dividing the volume of the CSG-flavored solution consumed by the total intake for the 30-min sessions and multiplying this quotient by 100. The preference scores for the same type of test were averaged across days for the statistical analyses. We analyzed the effect of surgery (SHAM and RYGB), sex (female and male), and training (Pre vs. Post) on the preference scores for each of the four Two-Bottle Tests using three-way ANOVA and then used two-way ANOVAs and two-tailed t-tests to explore significant interactions. A one-sample one-tailed t-test was used to test whether the mean preference score for each group was significantly higher from indifference (50%). The Training data were also analyzed by a mixed repeated measure two-way (stimulus x trial) ANOVA within each group. We also compared the total intake for the last two training days and Test 1 with a one-way repeated measures ANOVA followed by paired comparisons with t-tests. For t-tests, we present uncorrected p-values so that readers can choose the level of conservatism they wish to apply to the outcomes. The conventional p ≤ 0.05 was considered a statistically significant outcome.

3. Results

3.1. Body weight

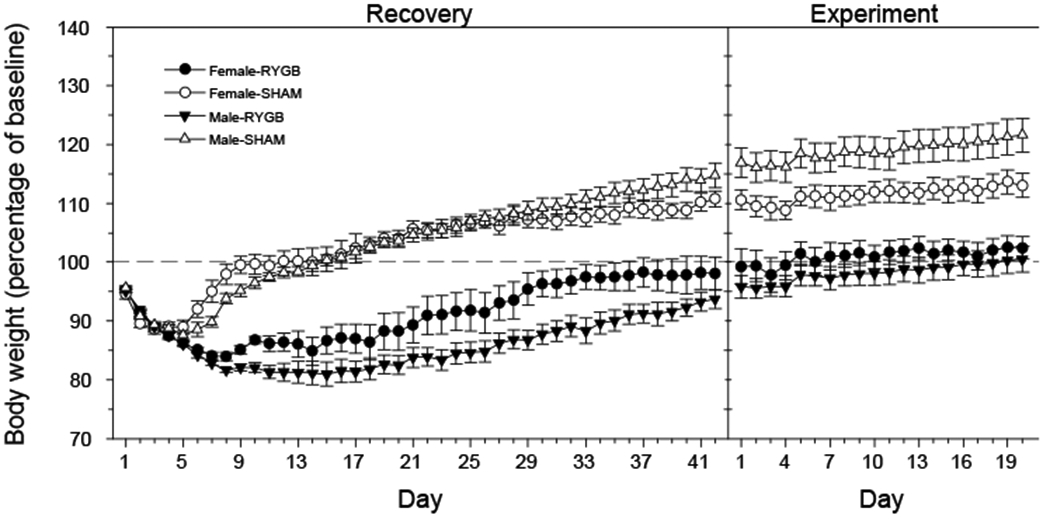

The percentage change in body weight during the recovery period after the surgery, and during the experiment is illustrated in Figure 2. As expected, all groups decreased body weight for the first few days after surgery in part due to the low calorie feeding during the initial stages of recovery, but the SHAM rats regained their weight and reached presurgical levels within about two weeks and then surpassed them after that. Rats receiving RYGB lost substantially more body weight after surgery and had a much slower rate of regain that appeared to plateau at or near the presurgical levels at the start of the experiment. The recovery of the body weight in the Female-RYGB group was more rapid than that in the Male-RYGB group. During the recovery and experiment phases, there was a significant main effect of surgery and day on percentage change in body weight and a significant sex x surgery interaction (Table 1). During the recovery period alone, there was also a day x surgery, day x sex, and day x sex x surgery interaction. Overall, the body weight results confirmed the effectiveness of the RYGB surgery in both males and females.

Figure 2.

Mean ± SE body weight changes after RYGB or sham operation for males and females. The weight on each day was presented as percentage of that on a day before surgery (baseline). The mean initial starting weight ± se on the baseline was 291.8 ± 5.53 g in Female-RYGB (n = 10), 296.3 ± 8.03 g in Female-SHAM (n = 10), 527.64 ± 7.17 g in Male-RYGB (n = 11), and 517.56 ± 14.66 g in Male-SHAM (n = 9).

Table 1.

Three-way (Surgery x Sex x Day) ANOVA of body weight (percentage of baseline)

| Surgery | Sex | Day | Sex x Surgery |

Day x Sex | Day x Surgery |

Day x Sex x Surgery |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recovery period | F (1, 19) = 104.7, p < 0.001 | F (1, 695) = 2.84, p = 0.092 | F (41, 779) = 88.63, p < 0.001 | F (1, 695) = 3.98, p < 0.05 | F (41, 695) = 1.48, p < 0.05 | F (41, 695) = 29.54, p < 0.001 | F (41, 695) = 4.38, p < 0.001 |

| Experiment | F (1, 19) = 53.95, p < 0.001 | F (1, 321) = 1.07, p = 0.302 | F (19, 361) = 32.47, p < 0.001 | F (1, 321) = 5.77, p < 0.05 | F (19, 321) = 1.59, p = 0.057 | F (19, 321) = 0.56, p = 0.9349 | F (19, 321) = 0.62, p = 0.892 |

Bold font indicates significant result

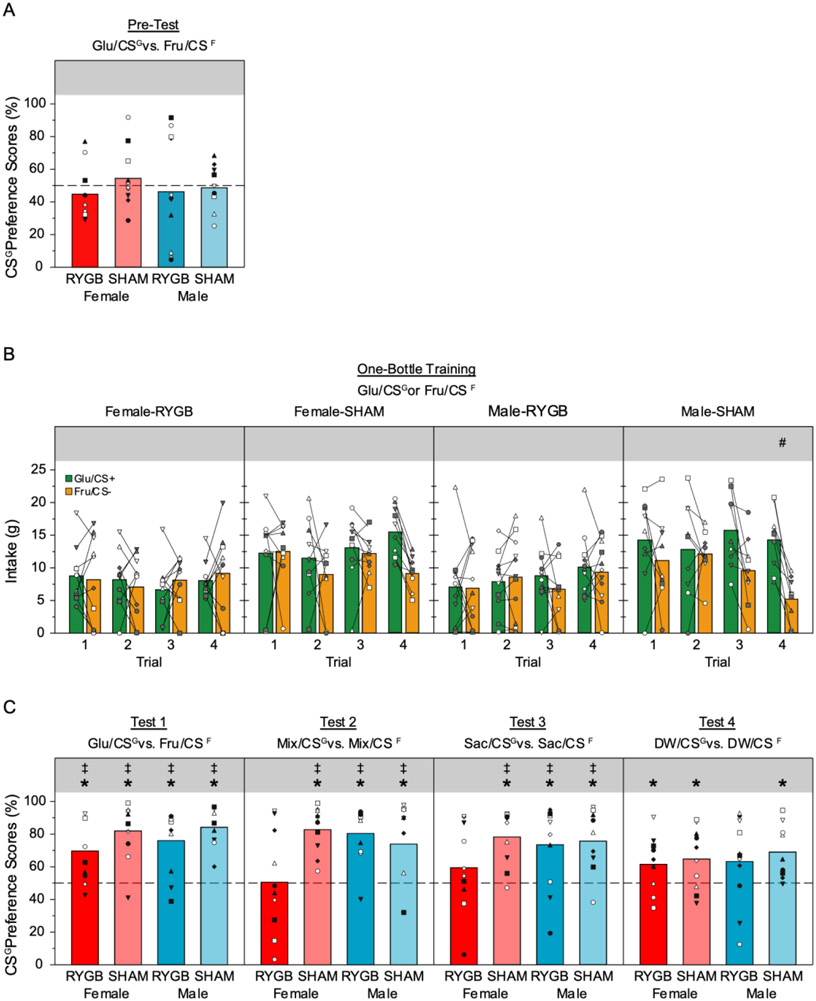

3.2. Pre-Test

Absolute intakes of the CS solutions during the Pre-Test, Training, and each of the four Tests are presented in Table 2. A two-way ANOVA (surgery x sex) revealed that there was no significant effect of surgery (F[1,36] = 0.71, p= 0.41), sex (F[1,36] = 0.09, p= 0.77), nor an interaction (F[1,36] = 0.25, p= 0.62) on the preference scores on the final 2 days of the Pre-Test, which served as the baseline (Figure 3A). The Glu/CSG preference scores for all of the groups hovered around 50%, and did not significantly differ from 50% (all ps > 0.40).

Table 2.

Mean ± SEM on each day of Pre-Test, Training, and Tests

| DAY | Female-RYGB | Female-SHAM | Male-RYGB | Male-SHAM | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Test | 1 | (Glu/CSG | 5.08±0.65 | 4.31±0.95 | 2.54±0.75 | 2.67±0.66 |

| Fru/CSF | 2.73±0.62 | 3.47±0.49 | 2.61±0.49 | 3.22±0.51 | ||

| 2 | (Glu/CSG | 7.23±0.97 | 8.64±1.61 | 3.39±1.22 | 4.88±1.08 | |

| Fru/CSF | 3.42±1.16 | 5.83±1.83 | 5.85±1.12 | 8.73±1.57 | ||

| 3 | (Glu/CSG | 5.76±0.95 | 11.46±2.28 | 4.5±1.12 | 9.64±1.88 | |

| Fru/CSF | 4.82±1.36 | 6.52±1.78 | 6.75±2.15 | 5.24±1.63 | ||

| 4 | (Glu/CSG | 2.79±0.68 | 8.04±1.43 | 4.05±1.53 | 5.52±1.76 | |

| Fru/CSF | 6.39±1.26 | 8.98±1.76 | 5.84±1.68 | 9.96±3.23 | ||

| Training | 1-2 | (Glu/CSG | 8.79±1.38 | 12.29±2.12 | 7.17±1.9 | 14.3±2.25 |

| Fru/CSF | 8.22±2.13 | 12.53±1.5 | 6.99±1.78 | 11.16±2.24 | ||

| 3-4 | (Glu/CSG | 8.21±1.39 | 11.55±1.83 | 7.99±1.39 | 12.86±2.51 | |

| Fru/CSF | 7.11±1.52 | 9.04±1.65 | 8.7±1.85 | 12.14±1.17 | ||

| 5-6 | (Glu/CSG | 6.69±1.36 | 13.11±1.63 | 8.89±1.32 | 15.77±1.89 | |

| Fru/CSF | 8.16±1.18 | 12.23±0.96 | 6.83±1.34 | 9.6±1.76 | ||

| 7-8 | (Glu/CSG | 8.08±0.87 | 15.57±1.21 | 10.23±1.48 | 14.38±1.56 | |

| Fru/CSF | 9.2±2 | 9.24±0.75 | 9.45±1.43 | 5.32±1.11 | ||

| Test 1 | 1 | (Glu/CSG | 5.58±1.34 | 14.32±1.79 | 11.07±1.77 | 14.57±1.86 |

| Fru/CSF | 3.76±0.97 | 3.08±1.1 | 1.91±0.64 | 2.57±1.32 | ||

| 2 | (Glu/CSG | 8.35±0.99 | 15.26±1.54 | 7.25±1.92 | 16.3±2.17 | |

| Fru/CSF | 2.28±1.01 | 2.51±0.75 | 3.78±1.27 | 2.52±0.57 | ||

| Test 2 | 1 | Mix/CSG | 6.86±2.53 | 16.95±1.2 | 11.18±1.35 | 13.69±3.66 |

| Mix/CSF | 5.29±1.1 | 1.98±0.74 | 3.23±0.94 | 6.2±2.8 | ||

| 2 | Mix/CSG | 7.08±2.15 | 12.51±2.1 | 11.85±1.4 | 13.78±1.57 | |

| Mix/CSF | 4.05±1.12 | 4.02±1.47 | 2.44±0.71 | 2.91±0.96 | ||

| Test 3 | 1 | Sac/CSG | 4.54±1.04 | 6.7±0.76 | 4.23±0.74 | 8.06±1.8 |

| Sac/CSF | 2.36±0.64 | 2.75±0.89 | 2.52±0.93 | 2.43±0.56 | ||

| 2 | Sac/CSG | 5.48±1.06 | 10.52±1.32 | 6.69±1 | 10.73±2.15 | |

| Sac/CSF | 3.38±0.78 | 2.89±1.07 | 2.59±1.2 | 2.47±0.65 | ||

| Test 4 | 1 | DW/CSG | 3.83±0.44 | 4.84±0.76 | 3.56±0.67 | 5.14±0.77 |

| DW/CSF | 2.31±0.45 | 1.61±0.43 | 1.81±0.32 | 1.42±0.44 | ||

| 2 | DW/CSG | 3.37±0.8 | 3.96±0.79 | 3.31±0.78 | 3.36±0.79 | |

| DW/CSF | 2±0.64 | 2.94±0.62 | 1.39±0.52 | 1.96±0.63 |

Figure 3.

Mean (bars) and individual (symbols) CSG-flavored solution preference scores on the last two days of the two-bottle Pre-Test (A) and the various two-bottle tests after training (C), and intake volume during single bottle Training (B); * in panels A and C represents significant (p ≤ 0.05) increases from 50%; ‡ in panel C represents significant (p ≤ 0.05) difference from Glu/CSG preference during Pre-Test. # represents significant (p ≤ 0.05) difference between Glu/CSG and Fru/CSF intake on a given test trial in the series in panel B.

3.3. Training

The Male-SHAM group drank more Glu/CSG than Fru/CSF in one-bottle exposures by the end of the training (Figure 3B, Table 3). A similar trend was seen in the Female-SHAM rats but the interaction in a stimulus x day two-way ANOVA failed to reach statistical significance. That said, there was a very clear difference in stimulus intake on the last two training days (i.e., last training trial) in Female-SHAM group. Every animal in this group drank more Glu/CSG than Fru/CSF and a paired t-test confirmed that the difference was statistically significant (t[9]=6.74, p < 0.001). In striking contrast, neither of the RYGB groups displayed any significant difference between the intake of the Glu/CSG and Fru/CSF.

Table 3.

Two-way (stimulus x trial) ANOVA of Training

| Group | Stimulus | Trial | Trial x Stimulus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female-RYGB | F (1, 18) = 0.02, p = 0.89 | F (3, 54) = 0.62, p = 0.60 | F (3, 54) = 0.67, p = 0.57 |

| Female-SHAM | F (1, 18) = 3.00, p = 0.10 | F (3, 54) = 1.34, p = 0.27 | F (3, 54) = 2.25, p = 0.09 |

| Male-RYGB | F (1, 20) = 0.11, p = 0.74 | F (3, 60) = 1.96, p = 0.13 | F (3, 60) = 0.49, p = 0.69 |

| Male-SHAM | F (1, 16) = 5.54, p < 0.05 | F (3, 48) = 2.01, p = 0.13 | F (3, 48) = 3.39, p < 0.05 |

Bold font indicates significant result

3.4. Two-Bottle Test

Test 1: Glu/CSG vs. Fru/CSF

A three-way ANOVA (training x surgery x sex) revealed a significant main effect of only training indicating the Glu/CSG preference increased overall after training relative to the Pre-Test (Table 4, Figure 3C). A series of one-sample t-tests demonstrated that each group displayed a preference for the Glu/CSG vs. Fru/CSF (Table 5). We conducted a matched t-test comparing the Pre-Test Glu/CSG preference score with that seen on Test 1 for each group, which revealed a significant increase in preference after training for all groups (Table 6) providing evidence of good flavor-nutrient conditioning.

Table 4.

Three-way (training x surgery x sex) ANOVA of Two-bottle test

| Group | Training | Surgery | Sex | Training x Surgery |

Training x Sex | Surgery x Sex | Training x Surgery x Sex |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test 1 | F (1, 36) = 35.69, p < 0.001 | F (1, 36) = 3.91, p = 0.056 | F (1, 36) = 0.07, p = 0.789 | F (1, 36) = 0.19, p = 0.666 | F (1, 36) = 0.44, p = 0.512 | F (1, 36) = 0.47, p = 0.498 | F (1, 36) = 0.02, p = 0.881 |

| Test 2 | F (1, 36) = 18.23, p < 0.001 | F (1, 36) = 3.89, p = 0.056 | F (1, 36) = 0.77, p = 0.385 | F (1, 36) = 0.41, p = 0.527 | F (1, 36) = 1.37, p = 0.25 | F (1, 36) = 5.78, p < 0.05 | F (1, 36) = 2.15, p = 0.15 |

| Test 3 | F (1, 36) = 21.43, p < 0.001 | F (1, 36) = 2.56, p = 0.118 | F (1, 36) = 0.12, p = 0.732 | F (1, 36) = 0.21, p = 0.649 | F (1, 36) = 0.62, p = 0.436 | F (1, 36) = 1.32, p = 0.258 | F (1, 36) = 0.23, p = 0.635 |

| Test 4 | F (1, 36) = 8.57, p < 0.01 | F (1, 36) = 1.67, p = 0.204 | F (1, 36) = 0.01, p = 0.921 | F (1, 36) = 0.02, p = 0.893 | F (1, 36) = 0.22, p = 0.643 | F (1, 36) = 0.08, p = 0.783 | F (1, 36) = 0.20, p = 0.658 |

Bold font indicates significant result

Table 5.

CSG Preference vs. 50% (one-sample t-test)

| Group | Test 1 | Test 2 | Test 3 | Test 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female-RYGB | t = 3.30, df = 9, p < 0.01 | t = 0.09, df = 9, p = 0.928 | t = 1.17, df = 9, p = 0.273 | t = 2.28, df = 9, p < 0.05 |

| Female-SHAM | t = 5.75, df = 9, p < 0.001 | t = 7.41, df = 9, p < 0.001 | t = 5.38, df = 9, p < 0.001 | t = 2.56, df = 9, p < 0.05 |

| Male-RYGB | t = 4.59, df = 10, p < 0.01 | t = 6.19, df = 10, p < 0.001 | t = 3.11, df = 10, p < 0.05 | t = 1.73, df = 10, p = 0.11 |

| Male-SHAM | t = 8.33, df = 8, p < 0.001 | t = 2.71, df = 8, p < 0.05 | t = 4.03, df = 8, p < 0.01 | t = 3.50, df = 8, p < 0.01 |

Bold font indicates significant result

Table 6.

t-test between preference scores on the Pre-Test days and each test

| Group | Test 1 | Test 2 | Test 3 | Test 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female-RYGB | t = 2.78, df = 9, p < 0.05 | t = 0.40, df = 9, p = 0.696 | t = 1.36, df = 9, p = 0.208 | t = 1.98, df = 9, p = 0.079 |

| Female-SHAM | t = 3.40, df = 9, p < 0.01 | t = 3.36, df = 9, p < 0.01 | t = 2.288, df = 9, p < 0.05 | t = 1.08, df = 9, p = 0.309 |

| Male-RYGB | t =2.34, df = 10, p < 0.05 | t = 3.21, df = 10, p < 0.01 | t = 2.57, df = 10, p < 0.05 | t = 1.19, df = 10, p = 0.261 |

| Male-SHAM | t = 4.87, df = 8, p < 0.01 | t = 2.49, df = 8, p < 0.05 | t = 3.94, df = 8, p < 0.01 | t = 2.18, df = 8, p =0.061 |

Bold font indicates significant result

The fact that both the Male-RYGB and Female-RYGB group displayed a clear demonstration of a conditioned preference for Glu/CSG over Fru/CSF in Test 1, but did not differentially consume these solutions during the single-bottle test on their respective last training days led us to question whether there was any evidence of ceiling effect for these animals during the single-bottle training tests. To explore this possibility, we conducted a 1-way repeated measures ANOVA on the average daily total intake during Test 1 (two-bottle test) and the intake of Glu/CSG and Fru/CSF on their respective last single-bottle training trial (Table 7). Only the SHAM groups displayed significantly different total intake across these tests. Paired comparisons with t-tests revealed that for both the Male-SHAM and Female-SHAM groups, Glu/CSG intake was significantly larger than Fru/CSF intake on the last training day (Male-SHAM: t[8]=6.17, p < 0.001; Female-SHAM: t[9]=6.74, p < 0.001). In the Female-SHAM group, Glu/CSG intake did not differ from the average daily intake during Test 1 (t[9]=1.42, p = 0.189). Although it is true that this comparison was significant in the Male-SHAM group, for which Test 1 intake was larger than the last training trial intake of Glu/CSG (t[8]=2.30, p = 0.05), in both SHAM groups total intake on Test 1 was significantly higher than intake of Fru/CSF on its last training trial (Male-SHAM: t[8]=6.19, p < 0.001; Female-SHAM: (t[9]=6.71, p < 0.001). Overall, the results of this analysis suggest that total intake in the animals with RYGB had a limit and this obscured the acquisition of the Glu/CSG over Fru/CSF differential intake in the single-bottle training trials. In support, a two-way ANOVA (surgery x sex) on the average daily intake of Test 1 (Table 2) revealed a significant main effect of surgery (F[1,36] = 26.8, p < 0.001), but no main effect of sex (F[1,36] = 0.85, p = 0.36) nor interaction (F[1,36] = 0.39, p = 0.54).

Table 7.

Mean ± SEM and One-way ANOVA of total intake on last training trial and Test 1

| Group | last training trial |

Test 1 | One-way ANOVA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Glu/CSG | Fru/CSF | |||

| Female-RYGB | 8.08 ± 0.87 | 9.2 ± 2 | 9.99 ± 0.9 | F (2, 18) = 0.75, p = 0.49 |

| Female-SHAM | 15.57 ± 1.21 | 9.24 ± 0.75 | 17.59 ± 0.99 | F (2, 18) = 25.59, p < 0.05 |

| Male-RYGB | 10.23 ± 1.48 | 9.45 ± 1.43 | 12.01 ± 1.43 | F (2, 20) = 0.98, p = 0.39 |

| Male-SHAM | 14.38 ± 1.56 | 5.32 ± 1.11 | 17.98 ± 1.77 | F (2, 16) = 29.04, p < 0.05 |

Bold font indicates significant result

Test 2: Mix/CSG vs. Mix/CSF

Test 2 was conducted to determine the effect of training on preference for the CSG Kool-Aid flavor over the CSF Kool-Aid flavor in a context in which both solutions were equally “sweet” and were isocaloric with a combination of the postoral effects of glucose and fructose. A three-way ANOVA (training x surgery x sex) revealed a significant main effect of only training indicating the Mix/CSG preference after training was greater than that for the Glu/CSG in the Pre-Test (Table 4, Figure 3C). There was also a significant surgery x sex interaction. A series of one-sample t-tests demonstrated that each group, except for the Female-RYGB group, displayed a preference for the Mix/CSG vs. Mix/CSF (Table 5). Likewise, a matched t-test comparing the Pre-Test Glu/CSG preference score with that seen on Test 2 revealed that the Mix/CSG preference after training was higher than that for the Pre-Test Glu/CSG for all groups except the Female-RYGB group (Table 6). Apparently, when we made the differential sugar cue ambiguous, there was no statistical evidence of a CSG preference for female rats that had RYGB.

Test 3: Sac/CSG vs. Sac/CSF

In Test 3, the mixture of 4.0% glucose and 4.0% fructose was replaced with the noncaloric sweetener saccharin to examine what impact the removal of the nutrient sources but maintenance of a “sweet” taste has on the preference for the CSG and CSF Kool-Aid flavors. A three-way ANOVA (training x surgery x sex) revealed a significant main effect of only training indicating that, overall, the Sac/CSG preference after training was greater than that for the Glu/CSG in the Pre-Test (Table 4, Figure 3C). Emulating what was seen in Test 2, all groups, except the Female-RYGB group, preferred the Sac/CSG to Sac/CSF solution, and the Sac/CSG preference on Test 3 was higher that the Pre-Test preference for Glu/CSG (Figure 3C, Tables 5 & 6). Thus, for the Male-SHAM, Female-SHAM, and Male-RYGB groups, the conditioned preference for the CSG Kool-Aid flavor remained clearly evident in the presence of a noncaloric sweetener even when the nutrients were removed.

Test 4: DW/ CSG vs. DW/ CSF

In Test 4, the CSG and CSF Kool-Aid flavors were presented alone in water without the presence of nutrients or sweeteners. A three-way ANOVA (training x surgery x sex) revealed a significant main effect of only training indicating that, overall, the DW/CSG preference after training was greater than that for the Glu/CSG in the Pre-Test (Table 4, Figure 3C). Nevertheless, there was evidence that the CSG preference decayed in all groups. A matched t-test comparing the Pre-Test Glu/CSG preference score with that seen on Test 4 for each group revealed that the DW/CSG preference after training was not significantly different from that for the Pre-Test Glu/CSG in all groups (Table 6, Figure 3C). A series of one-sample t-tests revealed that all groups, except the Male-RYGB group, displayed a preference for the DW/CSG vs. DW/CSF (Table 5). Because glucose and fructose were part of the CSG and CSF flavors during training, it is not surprising that when all sweeteners and calories were removed there was some observable decay in the expression of the learned preference depending on which measure is used to evaluate the behavior.

4. Discussion

It is well established, largely through the seminal work of Sclafani and his colleagues, that rats can learn preferences for Kool-Aid flavors that are paired with glucose ingestion [41,42, 46, 47]. Such preferences are not dependent simply on calories because learning does not occur, or is much less effective, if flavors are paired with fructose ingestion [43, 44, 52]. The development of this experience-dependent preference is considered to be a form of classical conditioning with the oral characteristics of the stimulus serving as the CS and the postoral characteristics of the stimulus serving as the unconditioned stimulus (US). While in this study glucose and fructose were both part of the CS and the US was Kool-Aid, the Kool-Aid presumably has no postingestive consequences; prior studies have shown that glucose or fructose infused directly into either the stomach, duodenum, or jejunum while animals drink a Kool-Aid+saccharin mixture leads to a preference for the glucose-, but not fructose-, paired flavor [50, 53]. Our results replicated the effectiveness of several sessions of one-bottle access to a mixture of a Kool-Aid flavor and 8% glucose interspersed with several sessions of a different Kool-Aid flavor mixed with 8% fructose to lead to a preference for the glucose-paired Kool-Aid flavor (i.e., CSG) when it contains a sweetener in both intact male and female rats that have received sham surgery (c.f. [41]).

At issue here, however, was whether rats with a reorganized gastrointestinal tract as a result of RYGB surgery would be similarly capable of demonstrating a conditioned preference for the glucose-paired flavor. On the one hand, intrajejunal infusions of glucose serve as an effective US supporting flavor preference learning and so one might predict that rats with RYGB would be competent at forming a preference for the glucose-paired flavor in our experimental design. On the other hand, RYGB surgery has a variety of anatomical and physiological consequences beyond the direct delivery of nutrients into the jejunum through a small gastric pouch [7, 54-59]. Indeed, RYGB rats display decreased intake and preferences for sucrose and glucose solutions at higher concentrations relative to sham-operated controls [28-33]. Thus, it was in question whether RYGB would compromise the effectiveness of the glucose to serve as a US.

After RYGB, males were entirely competent at learning a flavor preference under the conditions used in this study. They increased their preference for the Glu/CSG solution over that measured in the Pre-Test baseline, and their Glu/CSG preference relative to the Fru/CSF solution was significantly greater than indifference after training (Test 1) but not before. When glucose and fructose equally contributed to the caloric content of the CSG and CSF Kool-Aid flavors which was maintained at a density identical to that used in training, the Male-RYGB group still demonstrated a preference for the CSG Kool-Aid flavor (Test 2). Likewise, when calories were entirely removed from the solutions and sweetness was provided by saccharin, the Male-RYGB group preferred the CSG Kool-Aid flavor to the CSF Kool-Aid flavor (Test 3). It was only when the sweetness signal was removed and the CSG and CSF Kool-Aid flavors were presented in deionized water (Test 4), that the CSG preference disappeared in the Male-RYGB group statistically speaking, whereas it was somewhat maintained in the Male-SHAM group, depending on which measure was used to assess the preference.

After RYGB, females also displayed evidence of learning the flavor preference. After training, in Test 1, the Female-RYGB group displayed a significant preference for the Glu/CSG over the Fru/CSF solution relative to 50% and compared with their preference on the Pre-Test. However, during Test 2 when the differential saccharide signal was removed but the caloric density maintained in both the CSG and CSF solutions, the Female-RYGB group was the only one that failed to show a significant preference for the CSG over the CSF. The same was true for Test 3 when calories were removed by replacing the sugars with saccharin. We cannot dismiss the possibility that after many more training trials or if a higher (or lower) concentration of the sugars had been used, the Female-RYGB group would have displayed some type of CSG preference in Tests 2 and 3. It is also true that the Female-RYGB group showed a preference for the CSG over the CSF when the flavors were mixed in water (Test 4), suggesting that some vestige of the conditioned preference remained. Nevertheless, it is clear that after RYGB surgery, given the experimental parameters chosen here, the conditioned flavor preference was not as robust as in the other groups. It could reflect an impairment in learning about the components of the overall CS (i.e., the glucose, the flavor, the “sweetness”), or it could simply be that the Female-RYGB group formed a very specific learned response for the Glu/CSG stimulus and showed a very narrow generalization function.

That is, these decays in CSG preference, especially in the Female-RYGB group, would appear to represent a generalization decrement due to the removal of the differential sugar cues. Although any decay in CSG preference in Tests 2-4 could potentially represent some degree of extinction, flavor-glucose associations appear to be long-lasting and resistant to extinction [60-62]. These are not mutually exclusive possibilities. It would have been optimal to present the various 2-bottle tests in a counterbalanced order to help differentiate between extinction and differential generalization, but it was simply impractical because of the number of animals required for such a design and the difficulty and exceptional effort associated with the RYGB surgeries. We chose to focus instead on the fundamental question at hand regarding the ability of RYGB animals to learn a conditioned preference (i.e., Test 1). Accordingly, we adapted and applied a paradigm developed by Ackroff and Sclafani (1991). They presented solutions to the rats in 30-min tests as we did. We cannot, however, dismiss the possibility that a longer duration test may have been more sensitive at detecting a CSG preference, even in Test 4.

The mechanistic basis for the sex difference in the effect of RYGB on the expression of flavor preference learning in the generalization tests is unclear. The sex differences in eating behaviors are strongly affected by gonadal hormones, especially estrogen which interacts with gut peptides [63-66]. After RYGB, postprandial GLP-1 and peptide YY (PYY) levels are elevated [7], and it has been shown that estrogen administration interacts with GLP-1 and CCK satiation in a rat model of RYGB [67]. Therefore, one possibility is that, after RYGB, estrogen may interact with GLP-1 to alter the effectiveness of glucose to serve as a differential US over fructose. Here, we did not measure or try to control estrous cycling and thus it is difficult to confidently speculate on mechanism, but the possibility that circulating levels of estrogen may be at the root of the difference deserves further examination.

The Male-SHAM group eventually displayed increased intake of the Glu/CSG compared with the Fru/CSF solution in the single-bottle training trials. The Female-SHAM group also demonstrated such a trend, but the interaction between stimulus and day failed to reach statistical significance; nonetheless, the intake of the Glu/CSG was greater than that of the Fru/CSF for every animal on the last pair of training trials and was significantly different. In the RYGB groups, however, there was no hint of a selective increase in Glu/CSG relative to Fru/CSF intake during training. The lack of differential intake of the Glu/CSG and Fru/CSF solutions during training would appear to be at odds with the Glu/CSG preferences displayed by the RYGB groups in the first post-training two-bottle test. However, it is not without precedence. Prior studies in rats have also found that flavor preference learning in non-deprived animals is less evident in single-bottle tests and is more robustly displayed when the CSG and CSF are presented together in a choice test (e.g., [41]). It is interesting to also note, however, that the phenomenon of glucose-induced appetition was not observed in the RYGB groups. Appetition refers to the ability of certain nutrients such as glucose to increase intake within a single test session as a function of their ongoing reinforcing postingestive effects [68]. Glucose has been shown to be far more effective than fructose in generating appetition [42-44, 69]. It appears that the lack of differential intake between Glu/CSG and Fru/CSF during the single-bottle training trials in the RYGB groups is due to a ceiling past which further intake cannot be displayed. Indeed, on Test 1, the total intake of the RYGB groups was statistically lower than that in the SHAM groups and did not differ from the intake observed on the final pair of training trials. For whatever reason, perhaps the limitation in the amount of glucose that was ingested during training in the Female-RYGB group led to the apparent inability of this group to display the CSG preference in Tests 2 and 3. It is unclear, however, why this would not be the case in the Male-RYGB group as well.

Collectively, the results from this experiment show that RYGB does not compromise the ability of both male and female rats to express a conditioned flavor preference when the exact CS used in training is presented in testing. However, in female rats, RYGB compromises the ability to express the learning in further testing when the differential sugar cues are eliminated, at least under the conditions used here. In all but the female-RYGB group, the learned preference for the CSG remained even after the CSG and CSF Kool-Aid flavors were presented in a glucose-fructose mixture (Test 2) or presented in saccharin (Test 3). Indeed, for some of the groups there was some evidence of a CSG preference when the Kool-Aid flavors were presented in water (Test 4). On the other hand, in all groups, when the sweetness cue was removed in Test 4, the conditioned preference for the CSG Kool-Aid flavor had clearly decreased to levels similar with what was observed on the Pre-Test. The mechanism underlying the apparent sex-specific surgical effect on the generalization of flavor-preference learning remains to be elucidated. Nevertheless, the altered gut anatomy and physiological changes associated with RYGB do not eliminate the ability for glucose to serve as a US in flavor preference learning in rats.

Highlights:

RYGB does not impair acquisition of glucose vs. fructose flavor preference in rats.

Female RYGB rats display less generalization of the learned flavor preference.

RYGB impairs the expression of appetition for glucose in single-bottle tests.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported in part by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (R01DK106112) as part of the US-Ireland Research and Development Partnership. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Mingrone G, Panunzi S, De Gaetano A, Guidone C, Iaconelli A, Leccesi L, et al. Bariatric surgery versus conventional medical therapy for type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. (2012),366:1577–85. 10.1056/NEJMoa1200111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP, Wolski K, Brethauer SA, Navaneethan SD, et al. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes--3-year outcomes. N Engl J Med. (2014),370:2002–13. 10.1056/NEJMoa1401329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Tadross JA, le Roux CW The mechanisms of weight loss after bariatric surgery. Int J Obes (Lond). (2009),33 Suppl 1:S28–32. 10.1038/ijo.2009.14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Sjostrom L Bariatric surgery and reduction in morbidity and mortality: experiences from the SOS study. Int J Obes (Lond). (2008),32 Suppl 7:S93–7. 10.1038/ijo.2008.244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Miras AD, le Roux CW Mechanisms underlying weight loss after bariatric surgery. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2013), 10:575–84. 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Sweeney TE, Morton JM Metabolic surgery: action via hormonal milieu changes, changes in bile acids or gut microbiota? A summary of the literature. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. (2014),28:727–40. 10.1016/j.bpg.2014.07.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Steinert RE, Feinle-Bisset C, Asarian L, Horowitz M, Beglinger C, Geary N Ghrelin CCK, GLP-1, and PYY(3-36): Secretory Controls and Physiological Roles in Eating and Glycemia in Health, Obesity, and After RYGB. Physiol Rev. (2017),97:411–63. 10.1152/physrev.00031.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].le Roux CW, Aylwin SJ, Batterham RL, Borg CM, Coyle E, Prasad V, et al. Gut hormone profiles following bariatric surgery favor an anorectic state, facilitate weight loss, and improve metabolic parameters. Ann Surg. (2006),243:108–14. 10.1097/01.sla.0000183349.16877.84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Suzuki S, Ramos EJ, Goncalves CG, Chen C, Meguid MM Changes in GI hormones and their effect on gastric emptying and transit times after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in rat model. Surgery. (2005), 138:283–90. 10.1016/j.surg.2005.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kohli R, Bradley D, Setchell KD, Eagon JC, Abumrad N, Klein S Weight loss induced by Roux-en-Y gastric bypass but not laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding increases circulating bile acids. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2013),98:E708–12. 10.1210/jc.2012-3736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Zhang H, DiBaise JK, Zuccolo A, Kudrna D, Braidotti M, Yu Y, et al. Human gut microbiota in obesity and after gastric bypass. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (2009), 106:2365–70. 10.1073/pnas.0812600106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Hao Z, Mumphrey MB, Townsend RL, Morrison CD, Munzberg H, Ye J, et al. Body Composition, Food Intake, and Energy Expenditure in a Murine Model of Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass Surgery. Obes Surg. (2016),26:2173–82. 10.1007/s11695-016-2062-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Tamboli RA, Hossain HA, Marks PA, Eckhauser AW, Rathmacher JA, Phillips SE, et al. Body composition and energy metabolism following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Obesity (Silver Spring). (2010), 18:1718–24. 10.1038/oby.2010.89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Benedetti G, Mingrone G, Marcoccia S, Benedetti M, Giancaterini A, Greco AV, et al. Body composition and energy expenditure after weight loss following bariatric surgery. J Am Coll Nutr. (2000), 19:270–4. 10.1080/07315724.2000.10718926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Gahtan V, Goode SE, Kurto HZ, Schocken DD, Powers P, Rosemurgy AS Body composition and source of weight loss after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. (1997),7:184–8. 10.1381/096089297765555700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Papamargaritis D, Panteliou E, Miras AD, le Roux CW Mechanisms of weight loss, diabetes control and changes in food choices after gastrointestinal surgery. Curr Atheroscler Rep. (2012), 14:616–23. 10.1007/s11883-012-0283-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Mathes CM, Spector AC Food selection and taste changes in humans after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery: a direct-measures approach. Physiol Behav. (2012),107:476–83. 10.1016/j.physbeh.2012.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Ernst B, Thurnheer M, Wilms B, Schultes B Differential changes in dietary habits after gastric bypass versus gastric banding operations. Obes Surg. (2009), 19:274–80. 10.1007/s11695-008-9769-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Zheng H, Shin AC, Lenard NR, Townsend RL, Patterson LM, Sigalet DL, et al. Meal patterns, satiety, and food choice in a rat model of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. (2009),297:R1273–82. 10.1152/ajpregu.00343.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Makaronidis JM, Neilson S, Cheung WH, Tymoszuk U, Pucci A, Finer N, et al. Reported appetite, taste and smell changes following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy: Effect of gender, type 2 diabetes and relationship to post-operative weight loss. Appetite. (2016),107:93–105. 10.1016/j.appet.2016.07.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Graham L, Murty G, Bowrey DJ Taste, smell and appetite change after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Obes Surg. (2014),24:1463–8. 10.1007/s11695-014-1221-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Halmi KA, Mason E, Falk JR, Stunkard A Appetitive behavior after gastric bypass for obesity. Int J Obes. (1981),5:457–64 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Coughlin K, Bell RM, Bivins BA, Wrobel S, Griffen WO Jr. Preoperative and postoperative assessment of nutrient intakes in patients who have undergone gastric bypass surgery. Arch Surg. (1983), 118:813–6. 10.1001/archsurg.1983.01390070025006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Bavaresco M, Paganini S, Lima TP, Salgado W Jr., Ceneviva R, Dos Santos JE, et al. Nutritional course of patients submitted to bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. (2010),20:716–21. 10.1007/s11695-008-9721-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Thomas JR, Marcus E High and low fat food selection with reported frequency intolerance following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. (2008), 18:282–7. 10.1007/s11695-007-9336-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Nielsen MS, Christensen BJ, Ritz C, Rasmussen S, Hansen TT, Bredie WLP, et al. Roux-En-Y Gastric Bypass and Sleeve Gastrectomy Does Not Affect Food Preferences When Assessed by an Ad libitum Buffet Meal. Obes Surg. (2017),27:2599–605. 10.1007/s11695-017-2678-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Nielsen MS, Andersen I, Lange B, Ritz C, le Roux CW, Schmidt JB, et al. Bariatric Surgery Leads to Short-Term Effects on Sweet Taste Sensitivity and Hedonic Evaluation of Fatty Food Stimuli. Obesity (Silver Spring). (2019),27:1796–804. 10.1002/oby.22589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Bueter M, Miras AD, Chichger H, Fenske W, Ghatei MA, Bloom SR, et al. Alterations of sucrose preference after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Physiol Behav. (2011),104:709–21. 10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.07.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].le Roux CW, Bueter M, Theis N, Werling M, Ashrafian H, Lowenstein C, et al. Gastric bypass reduces fat intake and preference. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. (2011),301:R1057–66. 10.1152/ajpregu.00139.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Mathes CM, Bohnenkamp RA, Blonde GD, Letourneau C, Corteville C, Bueter M, et al. Gastric bypass in rats does not decrease appetitive behavior towards sweet or fatty fluids despite blunting preferential intake of sugar and fat. Physiol Behav. (2015),142:179–88. 10.1016/j.physbeh.2015.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Hyde KM, Blonde GD, Bueter M, le Roux CW, Spector AC Gastric bypass in female rats lowers concentrated sugar solution intake and preference without affecting brief-access licking after long-term sugar exposure. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. (2020),318:R870–R85. 10.1152/ajpregu.00240.2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Hajnal A, Kovacs P, Ahmed T, Meirelles K, Lynch CJ, Cooney RN Gastric bypass surgery alters behavioral and neural taste functions for sweet taste in obese rats. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. (2010),299:G967–79. 10.1152/ajpgi.00070.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Shin AC, Zheng H, Pistell PJ, Berthoud HR Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery changes food reward in rats. Int J Obes (Lond). (2011),35:642–51. 10.1038/ijo.2010.174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Mathes CM, Bueter M, Smith KR, Lutz TA, le Roux CW, Spector AC Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in rats increases sucrose taste-related motivated behavior independent of pharmacological GLP-1-receptor modulation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. (2012),302:R751–67. 10.1152/ajpregu.00214.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Mathes CM, Bohnenkamp RA, le Roux CW, Spector AC Reduced sweet and fatty fluid intake after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in rats is dependent on experience without change in stimulus motivational potency. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. (2015),309:R864–74. 10.1152/ajpregu.00029.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Mathes CM, Letourneau C, Blonde GD, le Roux CW, Spector AC Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in rats progressively decreases the proportion of fat calories selected from a palatable cafeteria diet. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. (2016),310:R952–9. 10.1152/ajpregu.00444.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Shin AC, Zheng H, Townsend RL, Patterson LM, Holmes GM, Berthoud HR Longitudinal assessment of food intake, fecal energy loss, and energy expenditure after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery in high-fat-fed obese rats. Obes Surg. (2013),23:531–40. 10.1007/s11695-012-0846-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Saeidi N, Nestoridi E, Kucharczyk J, Uygun MK, Yarmush ML, Stylopoulos N Sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass exhibit differential effects on food preferences, nutrient absorption and energy expenditure in obese rats. Int J Obes (Lond). (2012),36:1396–402. 10.1038/ijo.2012.167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Geary N, Bachler T, Whiting L, Lutz TA, Asarian L RYGB progressively increases avidity for a low-energy, artificially sweetened diet in female rats. Appetite. (2016),98:133–41. 10.1016/j.appet.2015.11.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Seyfried F, Miras AD, Bueter M, Prechtl CG, Spector AC, le Roux CW Effects of preoperative exposure to a high-fat versus a low-fat diet on ingestive behavior after gastric bypass surgery in rats. Surg Endosc. (2013),27:4192–201. 10.1007/s00464-013-3020-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Ackroff K, Sclafani A Flavor preferences conditioned by sugars: rats learn to prefer glucose over fructose. Physiol Behav. (1991),50:815–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Sclafani A, Ackroff K Glucose- and fructose-conditioned flavor preferences in rats: taste versus postingestive conditioning. Physiol Behav. (1994),56:399–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Sclafani A, Cardieri C, Tucker K, Blusk D, Ackroff K Intragastric glucose but not fructose conditions robust flavor preferences in rats. Am J Physiol. (1993),265:R320–5. 10.1152/ajpregu.1993.265.2.R320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Ackroff K, Touzani K, Peets TK, Sclafani A Flavor preferences conditioned by intragastric fructose and glucose: differences in reinforcement potency. Physiol Behav. (2001),72:691–703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Ackroff K, Sclafani A Fructose-conditioned flavor preferences in male and female rats: effects of sweet taste and sugar concentration. Appetite. (2004),42:287–97. 10.1016/j.appet.2004.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Myers KP, Sclafani A Conditioned enhancement of flavor evaluation reinforced by intragastric glucose: I. Intake acceptance and preference analysis. Physiol Behav. (2001),74:481–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Myers KP, Sclafani A Conditioned enhancement of flavor evaluation reinforced by intragastric glucose. II. Taste reactivity analysis. Physiol Behav. (2001),74:495–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Merino B, Fernandez-Diaz CM, Cozar-Castellano I, Perdomo G Intestinal Fructose and Glucose Metabolism in Health and Disease. Nutrients. (2019),12. 10.3390/nu12010094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Jang C, Hui S, Lu W, Cowan AJ, Morscher RJ, Lee G, et al. The Small Intestine Converts Dietary Fructose into Glucose and Organic Acids. Cell Metab. (2018),27:351–61 e3. 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.12.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Ackroff K, Yiin YM, Sclafani A Post-oral infusion sites that support glucose-conditioned flavor preferences in rats. Physiol Behav. (2010),99:402–11. 10.1016/j.physbeh.2009.12.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Schier LA, Spector AC Behavioral Evidence for More than One Taste Signaling Pathway for Sugars in Rats. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. (2016),36:113–24. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3356-15.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Sclafani A, Fanizza LJ, Azzara AV Conditioned flavor avoidance, preference, and indifference produced by intragastric infusions of galactose, glucose, and fructose in rats. Physiol Behav. (1999),67:227–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Sclafani A, Ackroff K Flavor preferences conditioned by intragastric glucose but not fructose or galactose in C57BL/6J mice. Physiol Behav. (2012),106:457–61. 10.1016/j.physbeh.2012.03.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Makaronidis JM, Batterham RL Potential Mechanisms Mediating Sustained Weight Loss Following Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass and Sleeve Gastrectomy. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. (2016),45:539–52. 10.1016/j.ecl.2016.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Gero D, Steinert RE, le Roux CW, Bueter M Do Food Preferences Change After Bariatric Surgery? Curr Atheroscler Rep. (2017),19:38. 10.1007/s11883-017-0674-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Kapoor N, Al-Najim W, le Roux CW, Docherty NG Shifts in Food Preferences After Bariatric Surgery: Observational Reports and Proposed Mechanisms. Curr Obes Rep. (2017),6:246–52. 10.1007/s13679-017-0270-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Zakeri R, Batterham RL Potential mechanisms underlying the effect of bariatric surgery on eating behaviour. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. (2018),25:3–11. 10.1097/MED.0000000000000379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Shoar S, Naderan M, Shoar N, Modukuru VR, Mahmoodzadeh H Alteration Pattern of Taste Perception After Bariatric Surgery: a Systematic Review of Four Taste Domains. Obes Surg. (2019),29:1542–50. 10.1007/s11695-019-03730-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Mathes CM Taste- and flavor-guided behaviors following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in rodent models. Appetite. (2020),146:104422. 10.1016/j.appet.2019.104422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Kimbrough A, Houpt TA Forty-eight hour conditioning produces a robust long lasting flavor preference in rats. Appetite. (2019),139:159–63. 10.1016/j.appet.2019.04.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Drucker DB, Ackroff K, Sclafani A Nutrient-conditioned flavor preference and acceptance in rats: effects of deprivation state and nonreinforcement. Physiol Behav. (1994),56:701–7. 10.1016/0031-9384(94)90230-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Myers KP Robust preference for a flavor paired with intragastric glucose acquired in a single trial. Appetite. (2007),48:123–7. 10.1016/j.appet.2006.07.077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Asarian L, Geary N Sex differences in the physiology of eating. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. (2013),305:R1215–67. 10.1152/ajpregu.00446.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Butera PC, Clough SJ, Bungo A Cyclic estradiol treatment modulates the orexigenic effects of ghrelin in ovariectomized rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. (2014),124:356–60. 10.1016/j.pbb.2014.07.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Asarian L, Geary N Cyclic estradiol treatment phasically potentiates endogenous cholecystokinin's satiating action in ovariectomized rats. Peptides. (1999),20:445–50. 10.1016/s0196-9781(99)00024-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Maske CB, Jackson CM, Terrill SJ, Eckel LA, Williams DL Estradiol modulates the anorexic response to central glucagon-like peptide 1. Horm Behav. (2017),93:109–17. 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2017.05.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Asarian L, Abegg K, Geary N, Schiesser M, Lutz TA, Bueter M Estradiol increases body weight loss and gut-peptide satiation after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in ovariectomized rats. Gastroenterology. (2012),143:325–7 e2. 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Sclafani A Gut-brain nutrient signaling. Appetition vs. satiation. Appetite. (2013),71:454–8. 10.1016/j.appet.2012.05.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Glendinning JI, Maleh J, Ortiz G, Touzani K, Sclafani A Olfaction contributes to the learned avidity for glucose relative to fructose in mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. (2020),318:R901–R16. 10.1152/ajpregu.00340.2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]