Abstract

A better understanding of the occurrence and risk of Plasmodium vivax infection among Duffy-negative individuals is required to guide further research on these infections across Africa. To address this, we used a meta-analysis approach to investigate the prevalence of P. vivax infection among Duffy-negative individuals and assessed the risk of infection in these individuals when compared with Duffy-positive individuals. This study was registered with The International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews website (ID: CRD42021240202) and followed Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analyses guidelines. Literature searches were conducted using medical subject headings to retrieve relevant studies in Medline, Web of Science, and Scopus, from February 22, 2021 to January 31, 2022. Selected studies were methodologically evaluated using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Tools to assess the quality of cross-sectional, case–control, and cohort studies. The pooled prevalence of P. vivax infection among Duffy-negative individuals and the odds ratio (OR) of infection among these individuals when compared with Duffy-positive individuals was estimated using a random-effects model. Results from individual studies were represented in forest plots. Heterogeneity among studies was assessed using Cochrane Q and I2 statistics. We also performed subgroup analysis of patient demographics and other relevant variables. Publication bias among studies was assessed using funnel plot asymmetry and the Egger’s test. Of 1593 retrieved articles, 27 met eligibility criteria and were included for analysis. Of these, 24 (88.9%) reported P. vivax infection among Duffy-negative individuals in Africa, including Cameroon, Ethiopia, Sudan, Botswana, Nigeria, Madagascar, Angola, Benin, Kenya, Mali, Mauritania, Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Senegal; while three reported occurrences in South America (Brazil) and Asia (Iran). Among studies, 11 reported that all P. vivax infection cases occurred in Duffy-negative individuals (100%). Also, a meta-analysis on 14 studies showed that the pooled prevalence of P. vivax infection among Duffy-negative individuals was 25% (95% confidence interval (CI) − 3%–53%, I2 = 99.96%). A meta-analysis of 11 studies demonstrated a decreased odds of P. vivax infection among Duffy-negative individuals (p = 0.009, pooled OR 0.46, 95% CI 0.26–0.82, I2 = 80.8%). We confirmed that P. vivax infected Duffy-negative individuals over a wide prevalence range from 0 to 100% depending on geographical area. Future investigations on P. vivax infection in these individuals must determine if Duffy-negativity remains a protective factor for P. vivax infection.

Subject terms: Parasitology, Malaria

Introduction

While Plasmodium falciparum is the most prevalent malaria parasite in the World Health Organization African Region and accounted for 99.7% of estimated malaria cases in 20181, there are increasing reports of P. vivax infection across Africa2,3. P. vivax infection of human erythrocytes requires the presence of a glycoprotein on the surface of red bloods, the Duffy blood group antigen or the Duffy Antigen Receptor for Chemokines (DARC)4,5. DARC is also the receptor for the simian malarial parasite, Plasmodium knowlesi6. DARC binds to P. vivax Duffy binding protein (PvDBP) before it invade erythrocytes7,8. The Duffy blood group is expressed by the FY gene on chromosome 1, and is genotyped as FY (a), FY (b), FY (a)ES, and FY (b)ES9. Duffy phenotypes, including Fy(a + b +), Fy(a + b −), and Fy(a − b +) are Duffy-positive phenotypes, while Fy(a − b −) or FY (a)ES(b)ES are Duffy-negative phenotypes. The Fy(a − b −) phenotype is caused by homozygosity of the FY allele carrying a point mutation at 67T > C (rs2814778) which prevents Duffy antigen expression in red blood cells10.

The Duffy-negative phenotype is highly predominant in sub-Saharan African populations, with high phenotype median frequencies of 98%–100% in west, mid, and south-eastern regions5. Recent studies reported that Duffy-negative individuals have a risk of P. vivax infection11,12. It was also postulated that P. vivax infections were passed back and forth between Duffy-positive and Duffy-negative individuals by P. vivax-infected mosquitoes parasitizing Duffy-positive individuals and transmitting parasites to Duffy-negative individuals13. As P. vivax infection can lead to severe malaria with poor outcomes14, a better understanding of P. vivax infection occurrence and risk among Duffy-negative individuals is required to guide further epidemiological research in Africa. Therefore, using a meta-analysis approach, we investigated P. vivax infection prevalence among Duffy-negative individuals and assessed the risk of infection among these individuals when compared with Duffy-positive individuals.

Methods

Protocol and registration

This study followed Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analyses guidelines15. The review was registered at The International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews website (ID: CRD42021240202).

Search strategy

Literature searches were conducted using medical subject headings in the National Library of Medicine and terms related to P. vivax malaria and Duffy status. The following search terms were used: “DBP” OR “D binding protein” OR “D-element-binding protein” OR “DBP transcription factor” OR “D-site binding protein.” Search terms are shown (Table S1). Medline, Web of Science, and Scopus were searched from the February 22, 2021 to the January 31, 2022. Additional searches of reference lists and review articles were also performed to ensure literature saturation.

Eligibility criteria

Cross-sectional, cohort, and case–control studies were considered if they reported P. vivax infections among Duffy-negative individuals. P. vivax infection was confirmed by microscopic or molecular analysis. Duffy genotypes or phenotypes were characterized by polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphisms, with and without sequencing. Only articles in English were included. The following articles were excluded: no Duffy-negative individuals among P. vivax cases, genetic analysis of the Duffy protein, no report on Duffy status, case reports and case series, experimental studies, clinical trials, and studies from which data could not be extracted.

Study selection

Study selection was performed in Endnote (Version X8, Clarivate Analytics, USA) by two authors (PW and MK). Discrepancies between authors on study selection were resolved by consensus and discussion with a third author (KUK). After retrieving articles, duplicated articles were removed. The remaining articles were title and abstract screened, after which irrelevant studies were excluded. The remaining article texts were examined according to eligibility criteria. All excluded articles were assigned appropriate reasons. Selected articles were further extracted using a standardized pilot datasheet.

Data extraction

The standardized pilot datasheet included the following: first author name, year of publication, study site, year the study was conducted, participants, age, gender, number of patients with malaria, number of P. vivax cases, number of P. vivax infections among Duffy-negative individuals, number of P. vivax infections among Duffy-positive individuals, malaria identification methods, and Duffy status. Two authors (PW and MK) independently collected these data. Disagreements over data extraction were resolved by discussion. Data were randomly checked by a third author (FRM) for completeness, plausibility, and integrity, before data was processed.

Study quality

The methodological quality of selected studies was evaluated using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Tools for assessing cross-sectional, case–control, and cohort studies16. The tool for cross-sectional studies comprised eight checklists, whereas 10 and 11 were used for case–control and cohort studies, respectively. Studies with > 75%, 50%, and ≤ 50% scores indicated high, moderate, or low quality, respectively. Study quality was assessed by two authors (PW and MK).

Study outcomes

The primary study outcome was the pooled prevalence of P. vivax infection among Duffy-negative individuals. The secondary outcome was the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of P. vivax infection among Duffy-negative individuals when compared with Duffy-positive individuals.

Data processing

Primary and secondary study outcomes were both estimated using the random-effects model. This model was used in the presence of heterogeneity of the effect estimates (ES) (pooled prevalence or OR); meanwhile, the fixed-effects model was used in the absence of heterogeneity of the ES. The results from individual studies were graphically represented on forest plots. Heterogeneity among studies was assessed using Cochrane Q and I2 statistics. A Cochrane Q p < 0.05 indicated significant heterogeneity among studies. I2 statistics were used to quantify heterogeneity; I2 > 50% indicated substantial heterogeneity. If heterogeneity existed, the random-effects model was used for pooled the pooled prevalence and OR, and if no heterogeneity was observed, the fixed-effects model was used for pooled the pooled prevalence and OR. Meta-regression analysis was performed to determine the source(s) of heterogeneity of ES (pooled prevalence, OR) among studies. If the source(s) of heterogeneity was identified, a subgroup analysis was conducted. We performed sensitivity analysis of the pooled prevalence and the odds of infection between Duffy-negative individuals using the fixed-effects model to determine the robustness of our meta-analysis results.

Publication bias

Publication bias was assessed by visualizing funnel plot asymmetry and the Egger’s test. Funnel plot asymmetry indicated publication bias. A significant Egger’s test (p < 0.05) indicated that funnel plot asymmetry was due to a small study effect. If the funnel plot was asymmetrical (by visualization or a significant Egger’s test), a contour-enhanced funnel plot was generated to identify if funnel plot asymmetry was due to publication bias or other causes.

Results

Search results

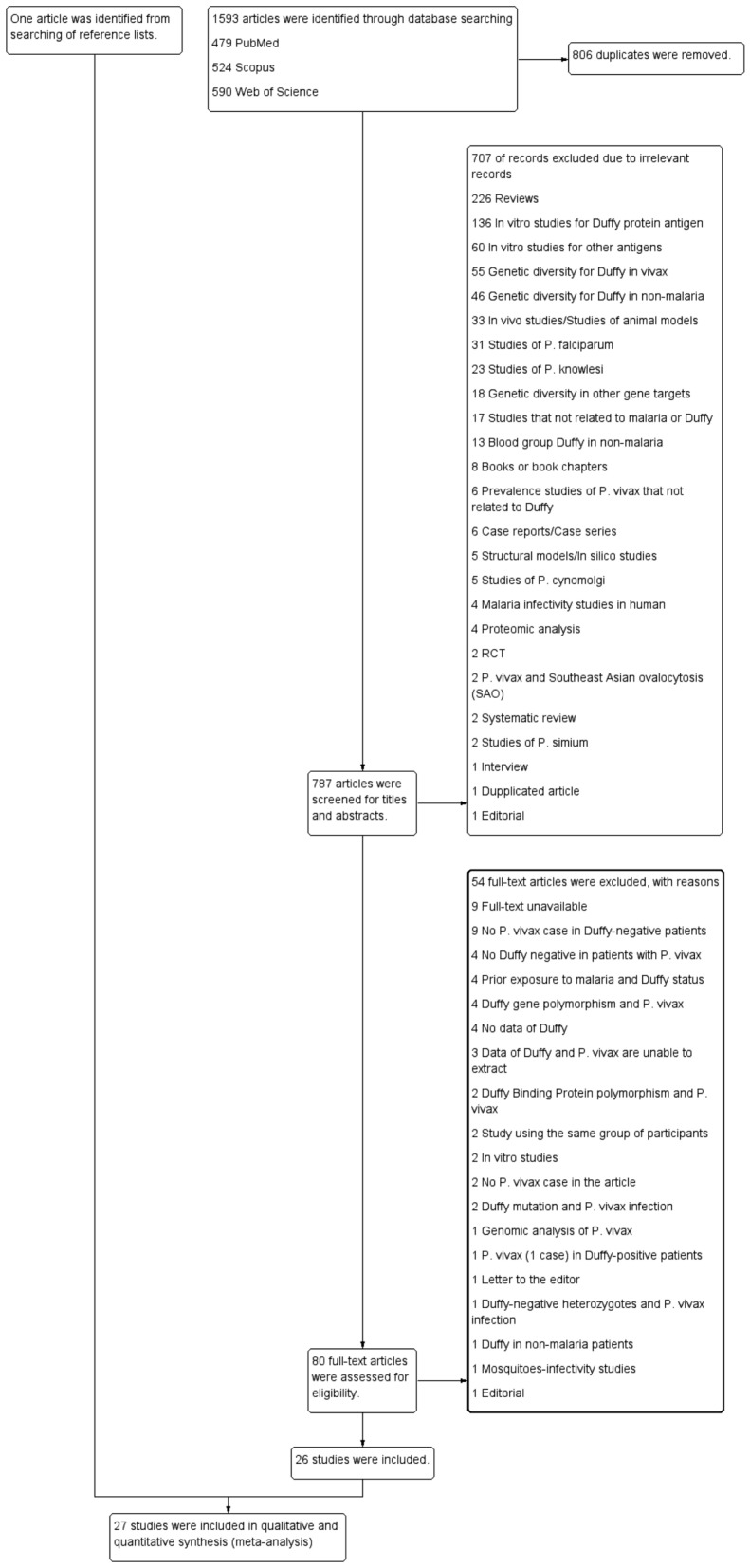

Of 1593 retrieved articles, 806 were retained after duplicated articles were removed. After screening title and abstracts of 787 articles, 707 were excluded due to irrelevance (Fig. 1). Thus, 80 articles were examined for full texts and 54 excluded due to the following reasons: nine full texts were unavailable, nine texts reported no P. vivax cases in Duffy-negative patients, four texts had no Duffy-negative patients with P. vivax infection, four texts indicated prior exposure to malaria and Duffy status, four texts reported Duffy gene polymorphisms and P. vivax infection, four texts had no Duffy data, three texts had Duffy and P. vivax data which could not be extracted, two reported DBP polymorphisms and P. vivax infection, two texts used the same participants, two texts were in vitro studies, two had no P. vivax cases, two reported a Duffy mutation and P. vivax infection, one text was a P. vivax genomic analysis, one text reported P. vivax (1 case) in Duffy-positive patients, one was a letter to the editor, one reported Duffy-negative heterozygotes and a P. vivax infection, one reported Duffy status in non-malaria patients, one was a mosquito-infectivity study, and one was an editorial. Thus, 26 studies17–42 met eligibility criteria, however, one study43 was identified from the bibliography of a study, therefore 27 studies17–43 met eligibility criteria and were included.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram demonstrating study selection process.

Study characteristics

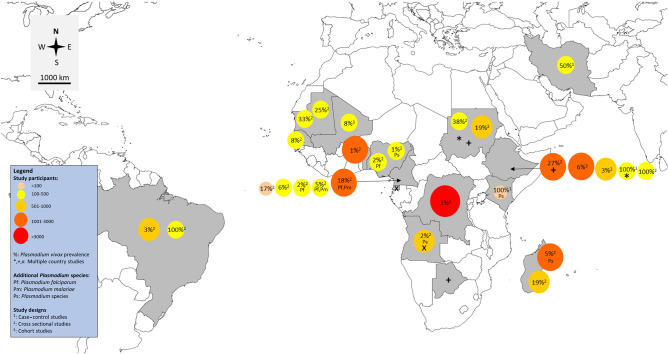

Study characteristics are shown (Table 1). All were published between 2006–2021 and almost all (24/27, 88.9%) reported P. vivax infection among Duffy-negative individuals in Africa. Three studies20,21,31 were conducted in South America (2/27, 7.4%) and Asia (1/27, 3.7%). Of the 24 African studies, six were conducted in East Africa (Ethiopia28,43, Madagascar25,29, Kenya40, and Ethiopia41), seven in Mid Africa (Democratic Republic of Congo19, Cameroon22,23,32,33,39, Angola, and Equatorial Guinea30), seven in West Africa (Mauritania24,42, Nigeria36,37, Senegal34, Mali35, and Benin38), two in North Africa (Sudan17,18), one in North and East Africa (Ethiopia and Sudan26), and one in Ethiopia/Botswana/Sudan27. Twenty-two articles were cross-sectional studies (22/27, 81.5%), two were case-controls12,40, and one was a cohort study35. The geographical distribution of studies is shown (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies.

| No | Author, year | Study area (years of the survey) | Study design | Age range (years) | Gender (male, %) | Participants | Method for Plasmodium spp. identification | Target gene for PCR | Number of P. vivax (malaria positive) | Method for Duffy antigen genotyping | Duffy status among P. vivax cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Abdelraheem et al. (2016) | Sudan (2009) | Cross-sectional study | < 10 (38), 10–20 (9), > 20 (1) | 22, 45.8 | 126 suspected malaria patients | Microscopy, RDT and PCR | SSU rRNA | 48 | PCR–RFLP |

Duffy negative: 4/4 Duffy positive: 44 |

| 2 | Albsheer et al. (2019) | Sudan (2013–2017) | Cross-sectional study | Mean 25 years | Male/female: 1.73 | 992 microscopy positive samples | Microscopy, PCR | SSU rRNA | 190 (992) | Sequencing (190) |

Duffy negative: 34/77 Duffy positive: 156/178 |

| 3 | Brazeau et al. (2021) | Democratic Republic of the Congo (2013–2014) | Cross-sectional study | 15–59 years and 15–49 years | NS | 17,972 screened for P. vivax infection | PCR | SSU rRNA | 467 (5646) | High-Resolution Melt (HRM) |

Duffy negative: 464/467 Duffy positive: 3 |

| 4 | Carvalho et al. (2012) | Brazil (2009) | Cross-sectional study | NS | NS | 678 individuals | Microscopy, PCR | mtDNA | 19 (137) | Sequencing |

Duffy negative: 2/29 Duffy positive: 96/553 |

| 5 | Cavasini et al. (2007) | Brazil (2003–2005) | Cross-sectional study | 18 years | NS | 312 patients with P. vivax infection | Microscopy, PCR | NS | 312 | PCR–RFLP |

Duffy negative: 2/312 Duffy positive: 310 |

| 6 | Dongho et al. (2021) | Cameroon (2016–2017) | Cross-sectional study | Any age | NS | Febrile outpatients (1,001) | PCR | SSU rRNA | 181 (37 mixed-infected with P. falciparum, 2 mixed-infected with P. malariae) (482) | PCR–RFLP | Duffy negative: 181/181 |

| 7 | Fru-Cho et al. (2014) | Cameroon (2008–2009) | Cross-sectional study | 18–55 years | NS | 269 individuals | Microscopy, PCR | SSU rRNA | 13 (4 mixed-infected with P. falciparum and P. malariae | PCR–RFLP, sequencing (12) |

Duffy negative: 6/12 Duffy positive: 6/12 |

| 8 | Gunalan et al. (2017) | Ethiopia | Cross-sectional study | NS | NS | 200 symptomatic or febrile patient | Microscopy, PCR | SSU rRNA | 200 | Sequencing |

Duffy negative: 2/71 Duffy positive: NA/129 |

| 9 | Hamdinou et al. (2017) | Mauritania | Cross-sectional study | NS | NS | 129 | Microscopy, RDT | – | 42 (129) | Indirect anti-globulin assay |

Duffy negative: 16/42 Duffy positive: 26 |

| 10 | Howes et al. (2018) | Madagascar (2014) | Cross-sectional study | 19.6 ± 16.5 | 977, 47.4 | 2,783 eligible individuals | Microscopy, RDT and PCR | SSU rRNA | 137 (37 mixed infected with other Plasmodium spp.) (275) | A microtyping kit |

Duffy negative: 44/914 Duffy positive: 86/964 |

| 11 | Kepple et al. (2021) | Ethiopia, Sudan | Case control study | NS | NS | 305 and 107 P. vivax samples from Duffy-positive and Duffy-negative individuals | PCR | SSU rRNA | 412 | NS |

Duffy negative: 16/107 Duffy positive: 42/305 |

| 12 | Lo et al. (2015) | Ethiopia | Cross-sectional study | 0–5 (72), 6–18 (128), > 18 (190) | NS | 390 and 416 community and clinical samples | PCR | SSU rRNA | 23 (73) | Sequencing |

Duffy negative: 2/139 Duffy positive: 21/251 |

| 13 | Lo et al. (2021) | Ethiopia, Botswana, Sudan | Cross-sectional study | NS | NS | 1215 febrile patients | Microscopy, PCR | SSU rRNA | 332 | Sequencing | Duffy negative: 49/332 |

| 14 | Ménard et al. (2010) | Madagascar (2007) | Cross-sectional study | 3–13 years | NS | 661 asymptomatic school children | Microscopy, RDT and PCR | SSU rRNA | 128 (263) | A micro typing kit |

Duffy negative: 42/476 Duffy positive: 86/185 |

| 15 | Mendes et al. (2011) | Angola (2006–2007) and Equatorial Guinea (2005) | Cross-sectional study | NS | NS | 995 individuals (898 from Angola and 97 from Equatorial Guinea) | PCR | SSU rRNA | 15 (10 mixed infected with other Plasmodium spp.) (245) | PCR–RFLP, sequencing | Duffy negative: 15/15 |

| 16 | Miri-Moghaddam et al. (2014) | Iran (2009–2012) | Case control study | Patients with P. vivax (29.9), patients without P. vivax (29.3) | NS | 160 patients with P. vivax and 160 patients without P. vivax infection | Microscopy | – | 160 | PCR–RFLP, sequencing |

Duffy negative: 2/6 Duffy positive: 158/314 |

| 17 | Mbenda et al. (2014) | Cameroon | Cross-sectional study | 1 month–82 years | 104, 51.7 | 485 malaria symptomatic patients | PCR | SSU rRNA | 8 (2 mixed infected with P. falciparum) (201) | Sequencing | Duffy negative: 8/8 |

| 18 | Mbenda et al. (2016) | Cameroon | Cross-sectional study | 2.3 months and 86 years | 20, 33.3 |

60 malaria symptomatic patients |

PCR | SSU rRNA | 10 (43) | Sequencing | Duffy negative: 10/10 |

| 19 | Niang et al. (2018) | Senegal (2010–2011) | Cross-sectional study | Mean 9 (8–11) | 28, 58.3 | 48 asymptomatic school children (192 samples) | PCR | SSU rRNA | 15 samples positive from 5 individuals (74 samples positive) | Sequencing | Duffy negative: 5/5 |

| 20 | Niangaly et al. (2017) | Mali (2009–2011) | Cohort study | New born to 6 years | NS | 300 children | Microscopy, PCR | SSU rRNA | 25 (134) | Sequencing | Duffy negative: 25/25 |

| 21 | Oboh et al. (2018) | Nigeria (2016–2017) | Cross-sectional study | Mean 23 (1–85) | 197, 45.2 | 436 febrile patients (256 samples for PCR) | Microscopy, RDT and PCR | SSU rRNA | 5 (4 mixed infected with other Plasmodium spp. (256) | Sequencing | Duffy negative: 5/5 |

| 22 | Oboh et al. (2020) | Nigeria (2016–2017) | Cross-sectional study | 25 (2–85), 26 (2–86) | 109, 45 | 242 individuals | Microscopy, RDT and PCR | SSU rRNA | 4 (1 mixed infected with P. falciparum) (145) | Sequencing | Duffy negative: 4/4 |

| 23 | Poirier et al., 2016 | Benin (2009–2010) | Cross-sectional study | NS | NS | 1,234 Beninese blood donors (86 for PCR) | Microscopy, RDT and PCR | SSU rRNA | 13 (86) | Sequencing | Duffy negative: 13/13 |

| 24 | Russo et al. (2017) | Cameroon | Cross-sectional study | Median 24 (4–40) | 191, 39.5 | 484 febrile outpatients | PCR | SSU rRNA | 27 (70) | Sequencing |

Duffy negative: 70/224 Duffy positive: 0/4 |

| 25 | Ryan et al. (2006) | Kenya (1999–2000) | Case–control study | NS | NS | 8 P. vivax positive cases | Microscopy, PCR | SSU rRNA | 9 (9 mixed infected with other Plasmodium spp.) | flow cytometry for Fy6 and Fy3 epitopes | Duffy negative: 9/9 |

| 26 | Woldearegai et al. (2013) | Ethiopia (2009) | Cross-sectional study | NS | NS | 1,931 febrile patients | Microscopy, PCR | SSU rRNA | 111 (205) | Sequencing |

Duffy negative: 3/41 Duffy positive: 108/164 |

| 27 | Wurtz et al. (2011) | Mauritania (2007–2009) | Cross-sectional study | NS | NS | 439 febrile outpatients (277 for Duffy blood group) | PCR | Aquaglyceroporin, P. vivax enoylacyl carrier protein reductase, P. ovale P25 ookinete surface protein | 110 | Sequencing |

Duffy negative: 1/52 Duffy positive: 109/206 |

NS Not specified.

Figure 2.

Distribution of included studies on P. vivax infection among Duffy-negative individuals. Map was sourced and modified from https://mapchart.net/world.html by authors. Authors were allowed to use, edit and modify any map created with mapchart.net for publication freely by adding the reference to mapchart.net in publication.

Study quality

Study quality was assessed using the JBI Critical Appraisal Tool (Table S2). Eighteen studies18,19,21,23,25–29,32,34–39,41,42 were high-quality, while nine17,20,22,24,30,31,33,40,43 were of moderate quality.

The prevalence of P. vivax infection among Duffy-negative individuals

Twenty-seven studies17–43 reported P. vivax infection among Duffy-negative individuals. Of these, 1117,22,30,32–38,40 reported that all P. vivax infection cases were Duffy-negative (100%). These studies were conducted in West Africa (Nigeria36,37, Senegal34, Mali35, Benin38), Mid Africa (Cameroon22,32,33, Angola and Equatorial Guinea30), North Africa (Sudan17), and East Africa (Kenya40).

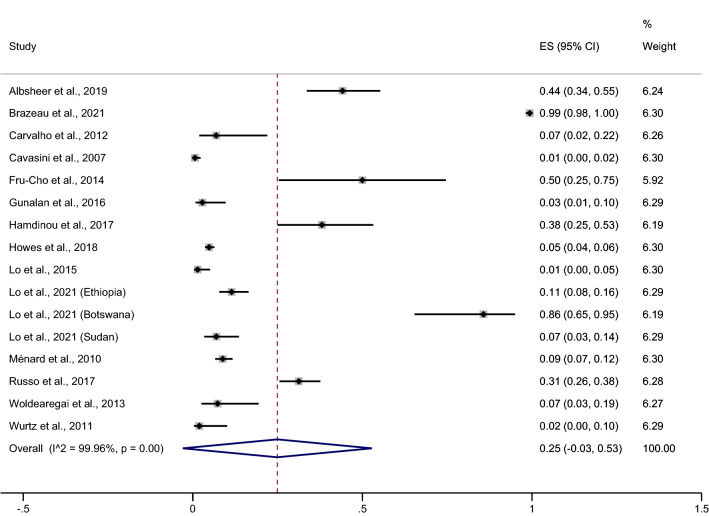

Fourteen studies18–21,23–25,27–29,39,41–43, conducted in 16 areas and reporting P. vivax infection prevalence among Duffy-negative individuals, were included in the pooled prevalence meta-analysis. These results showed that the pooled prevalence was 25% (95% CI − 3%–53%, I2 = 99.96%, Fig. 3). Due to high heterogeneity in studies reporting this prevalence, a meta-regression analysis of the continent as a covariate was performed to test if it (the continent) was a source of heterogeneity. These results showed that the continent covariate was indeed a source of heterogeneity in the pooled prevalence (p = 0.013), therefore, further subgroup continent analyses were performed.

Figure 3.

Forrest plot demonstrated the pooled prevalence of P. vivax infection among Duffy negative individuals. ES prevalence estimate, CI confidence interval.

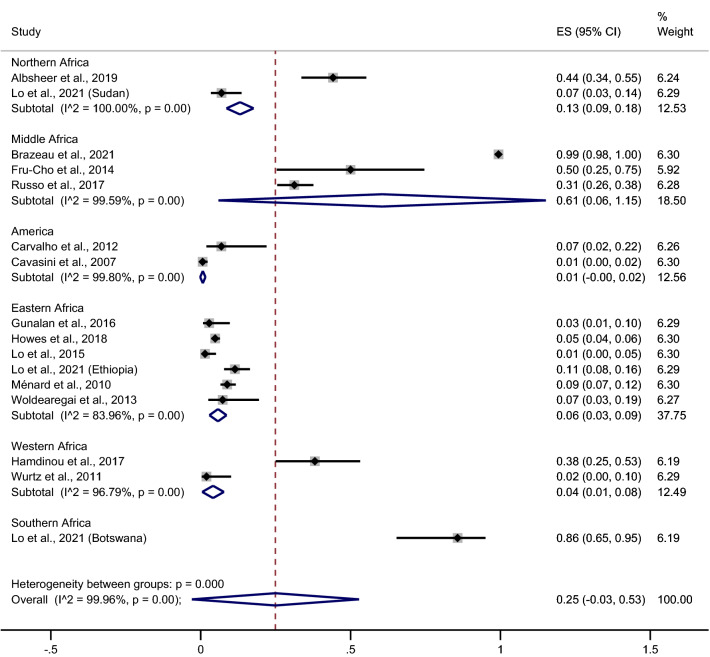

These results indicated that the highest prevalence of P. vivax infection among Duffy-negative individuals was identified in a Southern African study (Botswana, 86%, 95% CI 65%–95%)27, followed by Mid Africa (61%, 95% CI 6%–115%, I2 = 99.59%, three studies 19,23,39), and North Africa (13%, 95% CI 9%–18%, I2 = 100%, two studies18,27). However, a low prevalence was reported in an East African study [6%, 95% CI 3%–9%, I2 = 83.96%, five studies (six study areas)25,27,29,41,43], followed by West Africa (4%, 95% CI 1%–8%, I2 = 96.79%, two studies24,42). But the lowest prevalence was reported in a South American study (Brazil, 1%, 95% CI 0%–2%, I2 = 99.8%, two studies20,21) (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Forrest plot demonstrated the pooled prevalence of P. vivax infection among Duffy negative individuals stratified by continents. ES prevalence estimate, CI confidence interval.

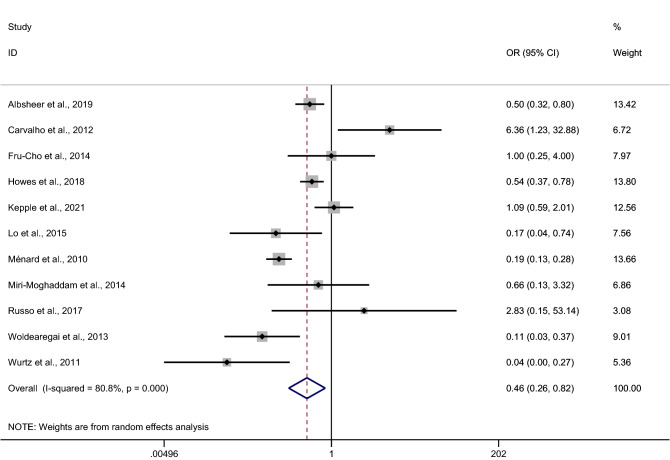

The odds of P. vivax infection among Duffy-negative individuals

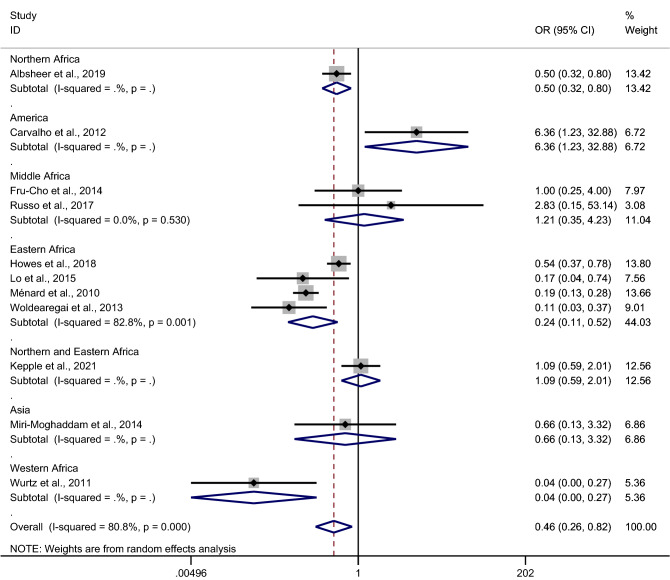

The odds of P. vivax infection among Duffy-negative individuals when compared with Duffy-positive individuals were estimated using data from 11 studies12,18,20,23,25,31,39,41,44–46. Results of individual study showed that Duffy-negativity was a protective factor for P. vivax infection in six studies17,25,41,44–46. These studies were conducted in Sudan18, Madagascar25,45, Ethiopia41,44, and Mauritania46. Only one study conducted outside Africa (Brazil) demonstrated a higher risk of P. vivax infection among Duffy-negative individuals20. No differences in infection risk were identified in four studies from Cameroon23,39, Ethiopia and Sudan12, and Iran31. Overall, our pooled analysis of 11 studies demonstrated a decreased odds of P. vivax infection among Duffy-negative individuals (p = 0.009, pooled OR 0.46, 95% CI 0.26–0.82, I2 = 80.8%, 11 studies, Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Forrest plot demonstrated the odd of P. vivax infection among Duffy negative individuals. OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval.

Due to a high degree of heterogeneity in some studies, a meta-regression analysis of country, continent, and study design as covariates, was performed to test if covariates were heterogeneity sources of the pooled OR; continent was identified as a heterogeneity source (p = 0.027), whereas, country and study design were not heterogeneity sources of the pooled OR (p = 0.06 and p = 0.188, respectively).

Subgroup continent analysis showed that the decreased odds of P. vivax infection among Duffy-negative individuals were identified in studies in North Africa (OR 0.50, 95% CI 0.32–0.80)18, East Africa (pooled OR 0.24, 95% CI 0.11–0.52, four studies25,28,29,41), and West Africa (OR 0.40, 95% CI 0–0.27)42. Also, the increased odds of P. vivax infection among Duffy-negative individuals were identified in a South American study (OR 6.36, 95% CI 1.23–32.88)20. Other studies from Mid Africa23,39, North and East Africa26, and Asia31 showed no differences in the odds of infection between Duffy-negative and Duffy-positive individuals (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Forrest plot demonstrated the odd of P. vivax infection among Duffy negative individuals stratified by continents. OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval l.

Sensitivity analysis

The sensitivity analysis showed that the pooled prevalence was 45% (95% CI 44%–45%, 14 studies in 16 areas, Supplementary Fig. 1). The decreased odds of infection between Duffy-negative individuals when compared with Duffy-positive individuals was p = 0.009, OR 0.46, 95% CI 0.26–0.82, 11 studies (Supplementary Fig. 2).

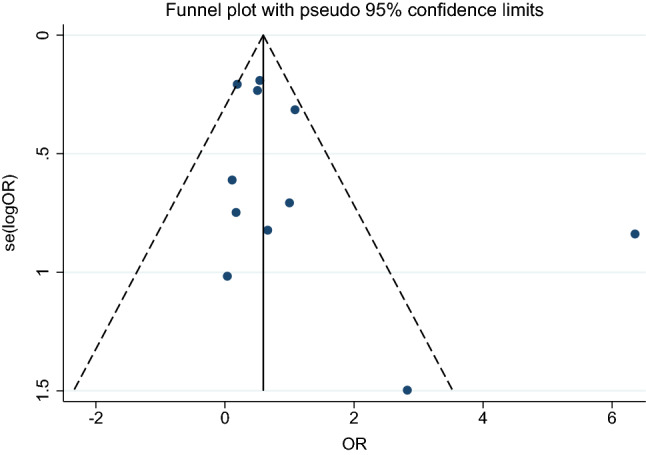

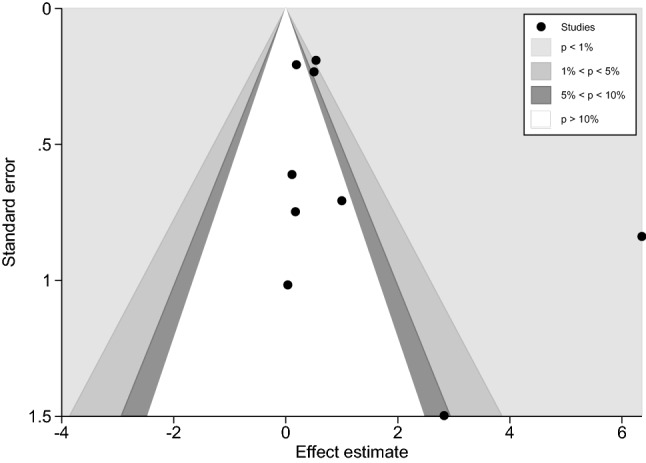

Publication bias

A funnel plot between ES (OR) and standard error of the logES of 11 studies showed a symmetrical funnel plot (Fig. 7). Egger’s test results showed no small study effects (p = 0.188). Contour-enhanced funnel plot analyses were performed to identify if funnel plot asymmetry was due to publication bias or other causes. These results showed that the ES’s were distributed in both significant and non-significant areas, thereby suggesting funnel plot asymmetry was due to other causes (e.g., heterogeneity in the OR between studies) (Fig. 8).

Figure 7.

The funnel plot between odds ratio (OR) and standard error (se) of the logOR of the 11 studies demonstrated that the funnel plot was asymmetry. OR odds ratio, se standard error.

Figure 8.

Contour-enhanced funnel plot demonstrated that the effect estimates were distributed in both significance and non-significance areas indicating that the funnel plot asymmetry was due to other causes.

Discussion

Duffy-negative individuals are typically resistant to P. vivax infection; however, a recent study showed that the Duffy-negative antigen was no longer a barrier to such infections30. In our review, we collated 27 studies showing P. vivax infection among Duffy-negative individuals in Africa, including Cameroon, Ethiopia, Sudan, Botswana, Nigeria, Madagascar, Angola, Benin, Kenya, Mali, Mauritania, Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Senegal. Moreover, three studies20,21,31 reported infections among Duffy-negative individuals in South America (Brazil)20,21 and Asia (Iran)31.

Our qualitative analyses showed that several studies17,22,30,32–38,40 reported that 100% P. vivax infection occurred in Duffy-negative individuals. In addition, our quantitative analyses (meta-analyses) showed that the pooled prevalence of infection among Duffy-negative individuals was 25%, with a high heterogeneity across studies. These finding confirmed data from previous studies and supported the hypothesis that Duffy-negativity was no longer protective against P. vivax infection. Nevertheless, a high prevalence of infection among Duffy-negative individuals was observed in West Africa34–38), Mid Africa19,22,23,30,32,33,39), North Africa17,18,27, East Africa40, and Southern Africa27. Our meta-analysis results showed that Duffy-negativity was protective against P. vivax infection in individuals from East Africa25,28,29,41, although several reports have documented about the infection of P. vivax in Duffy- negative individuals. Our forest plot demonstrated the increased odds of P. vivax infection among Duffy-negative individuals in studies outside Africa, such as South America. This was likely caused by a low sample size, as the authors suggested P. vivax infections were not significantly different between Duffy-positive and Duffy-negative individuals20.

Several mechanisms have been postulated for P. vivax infections among Duffy-negative individuals. (1) Duffy-positive individuals may act as P. vivax reservoirs and facilitate parasite infection of Duffy-negative hepatocytes, thereby selecting new P. vivax strains which invade Duffy-negative erythrocytes via Duffy-independent mechanisms45. (2) P. vivax evolution for host selection may have occurred in Africa due to ideal temperatures and highly competent transmission vectors17. (3) In Africa, increased vector capacity to transmit other P. vivax malaria parasites such as Anopheles gambiae and An. Arabiensis has been observed40,47. Demographic factors and a high population density of young age groups may have contributed to a higher entomological inoculation rate, and contributed to P. vivax infection in Duffy-negative individuals, similar to P. falciparum infection12,48. (4) Parasite adaptation may have occurred for P. knowlesi infection rates, potentially facilitating the zoonotic transmission of specific P. vivax strains in Duffy-negative individuals, resulting from long exposure to P. vivax infections in African populations. In studies on simian malaria parasites requiring the Duffy protein antigen for erythrocyte invasion, P. knowlesi invaded Duffy-negative erythrocytes, suggesting a Duffy-independent P. knowlesi infection mechanism49. (5) P. vivax can hide in the bone marrow of Duffy-negative hosts and persist as low parasitemic, asymptomatic infections50. (6) Difference in latitude in some areas could affect P. vivax transmission, e.g., higher altitudes in Cameroon11, therefore, P. vivax could infect populations in these areas rather than P. falciparum, suggesting P. vivax abilities to infect populations in higher altitudes51. (7) P. vivax may use several receptor-ligand interactions to tightly bind erythrocytes in the absence of a Duffy receptor, e.g., the glycophosphatidylinositol-anchored micronemal antigen or tryptophan-rich antigens52.

Our study had some limitations. Firstly, we identified a limited number of studies reporting P. vivax infection among Duffy-negative individuals. Secondly, we identified high heterogeneity among studies. Thirdly, we observed funnel plot asymmetry which was likely caused by heterogeneity of the ES among studies. Although subgroup analyses were performed, the heterogeneity persisted. Therefore, our results must be interpreted with caution.

Conclusions

Our systematic review and meta-analysis confirmed that P. vivax infected Duffy-negative individuals over a wide prevalence range from 0 to 100% depending on different geographical areas. Future investigations are required to determine if Duffy-negativity is still protective for P. vivax infection.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

This research was partially supported by the New Strategic Research (P2P) Project, Walailak University, Thailand.

Author contributions

P.W. and M.K. carried out the study design, study selection, data extraction, and statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. F.R.M., K.U.K. and G.D.M. participated in the study selection and data extraction and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially supported by the New Strategic Research (P2P) project fiscal year 2022, Walailak University, Thailand. The funders had on role in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data.

Data availability

All data related to this study are available in this manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-022-07711-5.

References

- 1.World Malaria Report 2019. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241565721.

- 2.Twohig KA, Pfeffer DA, Baird JK, Price RN, Zimmerman PA, Hay SI, Gething PW, Battle KE, Howes RE. Growing evidence of Plasmodium vivax across malaria-endemic Africa. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2019;13:e0007140. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oboh MA, Oyebola KM, Idowub ET, Badianea AS, Otubanjo OA, Ndiayea D. Rising report of Plasmodium vivax in sub-Saharan Africa: Implications for malaria elimination agenda. Sci. Afr. 2020;10:e00596. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller LH, Mason SJ, Clyde DF, McGinniss MH. The resistance factor to Plasmodium vivax in blacks: The Duffy-blood-group genotype, FyFy. N. Engl. J. Med. 1976;295:302–304. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197608052950602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Howes RE, Patil AP, Piel FB, Nyangiri OA, Kabaria CW, Gething PW, Zimmerman PA, Barnadas C, Beall CM, Gebremedhin A, et al. The global distribution of the Duffy blood group. Nat. Commun. 2011;2:266. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaudhuri A, Zbrzezna V, Johnson C, Nichols M, Rubinstein P, Marsh WL, Pogo AO. Purification and characterization of an erythrocyte membrane protein complex carrying Duffy blood group antigenicity. Possible receptor for Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium knowlesi malaria parasite. J. Biol. Chem. 1989;264:13770–13774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chitnis CE, Sharma A. Targeting the Plasmodium vivax Duffy-binding protein. Trends Parasitol. 2008;24:29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chaudhuri A, Polyakova J, Zbrzezna V, Williams K, Gulati S, Pogo AO. Cloning of glycoprotein D cDNA, which encodes the major subunit of the Duffy blood group system and the receptor for the Plasmodium vivax malaria parasite. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:10793–10797. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.22.10793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.King CL, Adams JH, Xianli J, Grimberg BT, McHenry AM, Greenberg LJ, Siddiqui A, Howes RE, da Silva-Nunes M, Ferreira MU, Zimmerman PA. Fy(a)/Fy(b) antigen polymorphism in human erythrocyte Duffy antigen affects susceptibility to Plasmodium vivax malaria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:20113–20118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109621108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoher G, Fiegenbaum M, Almeida S. Molecular basis of the Duffy blood group system. Blood Transfus. 2018;16:93–100. doi: 10.2450/2017.0119-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Djeunang Dongho GB, Gunalan K, L'Episcopia M, Paganotti GM, Menegon M, Sangong RE, Georges BM, Fondop J, Severini C, Sobze MS, et al. Plasmodium vivax infections detected in a large number of febrile Duffy-negative Africans in Dschang, Cameroon. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2021;2021:1–10. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kepple D, Hubbard A, Ali MM, Abargero BR, Lopez K, Pestana K, Janies DA, Yan G, Hamid MM, Yewhalaw D, Lo E. Plasmodium vivax from Duffy-negative and Duffy-positive individuals shares similar gene pool in east Africa. J. Infect. Dis. 2021;224:1422–1431. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiab063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gunalan K, Niangaly A, Thera MA, Doumbo OK, Miller LH. Plasmodium vivax infections of Duffy-negative erythrocytes: Historically undetected or a recent adaptation? Trends Parasitol. 2018;34:420–429. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2018.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kotepui M, Kotepui KU, Milanez GJ, Masangkay FR. Prevalence and risk factors related to poor outcome of patients with severe Plasmodium vivax infection: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and analysis of case reports. BMC Infect. Dis. 2020;20:363. doi: 10.1186/s12879-020-05046-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moola SMZ, Tufanaru C, Aromataris E, Sears K, Sfetcu R, Currie M, Qureshi R, Mattis P, Lisy K, Mu P-F. Systematic Reviews of Etiology and Risk. JBI; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abdelraheem MH, Albsheer MM, Mohamed HS, Amin M, Abdel Hamid MM. Transmission of Plasmodium vivax in Duffy-negative individuals in central Sudan. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2016;110:258–260. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/trw014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Albsheer MMA, Pestana K, Ahmed S, Elfaki M, Gamil E, Ahmed SM, Ibrahim ME, Musa AM, Lo E, Abdel Hamid MM. Distribution of duffy phenotypes among Plasmodium vivax infections in Sudan. Genes. 2019;2019:10. doi: 10.3390/genes10060437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brazeau NF, Mitchell CL, Morgan AP, Deutsch-Feldman M, Watson OJ, Thwai KL, Gelabert P, van Dorp L, Keeler CY, Waltmann A, et al. The epidemiology of Plasmodium vivax among adults in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:4169. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24216-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carvalho TA, Queiroz MG, Cardoso GL, Diniz IG, Silva AN, Pinto AY, Guerreiro JF. Plasmodium vivax infection in Anajás, State of Pará: No differential resistance profile among Duffy-negative and Duffy-positive individuals. Malar. J. 2012;11:430. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-11-430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cavasini CE, de Mattos LC, D'Almeida Couto AAR, D'Almeida Couto VSC, Gollino Y, Moretti LJ, Bonini-Domingos CR, Rossit ARB, Castilho L, Machado RLD. Duffy blood group gene polymorphisms among malaria vivax patients in four areas of the Brazilian Amazon region. Malar. J. 2007;6:8. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-6-167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Djeunang Dongho GB, Gunalan K, L'Episcopia M, Paganotti GM, Menegon M, Efeutmecheh Sangong R, Bouting Mayaka G, Fondop J, Severini C, Sanou Sobze M, et al. Plasmodium vivax infections detected in a large number of febrile Duffy-negative Africans in Dschang, Cameroon. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2021;104:987–992. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fru-Cho J, Bumah VV, Safeukui I, Nkuo-Akenji T, Titanji VP, Haldar K. Molecular typing reveals substantial Plasmodium vivax infection in asymptomatic adults in a rural area of Cameroon. Malar. J. 2014;13:170. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-13-170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hamdinou MM, Deida J, Ebou MH, El-Ghassem A, Lekweiry KM, Salem M, Tahar R, Simard F, Basco L, Boukhary A. Distribution of Duffy blood group (FY) phenotypes among Plasmodium vivax-infected patients in Nouakchott, Mauritania. Trop. Med. Int. Health. 2017;22:127–128. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Howes RE, Franchard T, Rakotomanga TA, Ramiranirina B, Zikursh M, Cramer EY, Tisch DJ, Kang SY, Ramboarina S, Ratsimbasoa A, Zimmerman PA. Risk factors for malaria infection in central Madagascar: Insights from a cross-sectional population survey. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2018;99:995–1002. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.18-0417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kepple D, Hubbard A, Ali MM, Abargero BR, Lopez K, Pestana K, Janies DA, Yan GY, Hamid MM, Yewhalaw D, Lo E. Plasmodium vivax from Duffy-negative and Duffy-positive individuals share similar gene pools in east Africa. J. Infect. Dis. 2021;224:1422–1431. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiab063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lo E, Russo G, Pestana K, Kepple D, Abagero BR, Dongho GBD, Gunalan K, Miller LH, Hamid MMA, Yewhalaw D, Paganotti GM. Contrasting epidemiology and genetic variation of Plasmodium vivax infecting Duffy-negative individuals across Africa. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021;108:63–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lo E, Yewhalaw D, Zhong DB, Zemene E, Degefa T, Tushune K, Ha M, Lee MC, James AA, Yan GY. Molecular epidemiology of Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium falciparum malaria among Duffy-positive and Duffy-negative populations in Ethiopia. Malar. J. 2015;14:10. doi: 10.1186/s12936-015-0596-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ménard D, Barnadas C, Bouchier C, Henry-Halldin C, Gray LR, Ratsimbasoa A, Thonier V, Carod JF, Domarle O, Colin Y, et al. Plasmodium vivax clinical malaria is commonly observed in Duffy-negative Malagasy people. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:5967–5971. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912496107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mendes C, Dias F, Figueiredo J, Mora VG, Cano J, de Sousa B, de Rosario VE, Benito A, Berzosa P, Arez AP. Duffy negative antigen is no longer a barrier to Plasmodium vivax: Molecular evidences from the African West Coast (Angola and Equatorial Guinea) PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2011;5:6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miri-Moghaddam E, Bameri Z, Mohamadi M. Duffy blood group genotypes among malaria Plasmodium vivax patients of Baoulch population in Southeastern Iran. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2014;7:206–207. doi: 10.1016/S1995-7645(14)60021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.NgassaMbenda HG, Das A. Molecular evidence of Plasmodium vivax mono and mixed malaria parasite infections in Duffy-negative native Cameroonians. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e103262. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ngassa Mbenda HG, Gouado I, Das A. An additional observation of Plasmodium vivax malaria infection in Duffy-negative individuals from Cameroon. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2016;10:682–686. doi: 10.3855/jidc.7554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Niang M, Sane R, Sow A, Sadio BD, Chy S, Legrand E, Faye O, Diallo M, Sall AA, Menard D, Toure-Balde A. Asymptomatic Plasmodium vivax infections among Duffy-negative population in Kedougou, Senegal. Trop. Med. Health. 2018;46:45. doi: 10.1186/s41182-018-0128-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Niangaly A, Karthigayan G, Amed O, Coulibaly D, Sá JM, Adams M, Travassos MA, Ferrero J, Laurens MB, Kone AK, et al. Plasmodium vivax infections over 3 years in Duffy blood group negative Malians in Bandiagara, Mali. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2017;97:744–752. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.17-0254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oboh MA, Badiane AS, Ntadom G, Ndiaye YD, Diongue K, Diallo MA, Ndiaye D. Molecular identification of Plasmodium species responsible for malaria reveals Plasmodium vivax isolates in Duffy negative individuals from southwestern Nigeria. Malar. J. 2018;17:439. doi: 10.1186/s12936-018-2588-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oboh MA, Singh US, Singh US, Ndiaye D, Badiane AS, Ali NA, Bharti PK, Das A. Presence of additional Plasmodium vivax malaria in Duffy negative individuals from Southwestern Nigeria. Malar. J. 2020;19:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12936-020-03301-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Poirier P, Doderer-Lang C, Atchade PS, Lemoine JP, de l’Isle MC, Abou-Bacar A, Pfaff AW, Brunet J, Arnoux L, Haar E, et al. The hide and seek of Plasmodium vivax in West Africa: Report from a large-scale study in Beninese asymptomatic subjects. Malar. J. 2016;15:570. doi: 10.1186/s12936-016-1620-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Russo G, Faggioni G, Paganotti GM, Djeunang Dongho GB, Pomponi A, De Santis R, Tebano G, Mbida M, Sanou Sobze M, Vullo V, et al. Molecular evidence of Plasmodium vivax infection in Duffy negative symptomatic individuals from Dschang, West Cameroon. Malar. J. 2017;16:74. doi: 10.1186/s12936-017-1722-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ryan JR, Stoute JA, Amon J, Dunton RF, Mtalib R, Koros J, Owour B, Luckhart S, Wirtz RA, Barnwell JW, Rosenberg R. Evidence for transmission of Plasmodium vivax among a duffy antigen negative population in Western Kenya. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2006;75:575–581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Woldearegai TG, Kremsner PG, Kun JF, Mordmüller B. Plasmodium vivax malaria in Duffy-negative individuals from Ethiopia. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2013;107:328–331. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/trt016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wurtz N, Mint Lekweiry K, Bogreau H, Pradines B, Rogier C, Ould Mohamed Salem Boukhary A, Hafid JE, Ould Ahmedou Salem MS, Trape JF, Basco LK, Briolant S. Vivax malaria in Mauritania includes infection of a Duffy-negative individual. Malar. J. 2011;10:336. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-10-336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gunalan K, Lo E, Hostetler JB, Yewhalaw D, Mu J, Neafsey DE, Yan G, Miller LH. Role of Plasmodium vivax Duffy-binding protein 1 in invasion of Duffy-null Africans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:6271–6276. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1606113113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lo E, Yewhalaw D, Zhong D, Zemene E, Degefa T, Tushune K, Ha M, Lee MC, James AA, Yan G. Molecular epidemiology of Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium falciparum malaria among Duffy-positive and Duffy-negative populations in Ethiopia. Malar. J. 2015;14:84. doi: 10.1186/s12936-015-0596-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Menard D, Barnadas C, Bouchier C, Henry-Halldin C, Gray LR, Ratsimbasoa A, Thonier V, Carod JF, Domarle O, Colin Y, et al. Plasmodium vivax clinical malaria is commonly observed in Duffy-negative Malagasy people. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:5967–5971. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912496107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wurtz N, Lekweiry KM, Bogreau H, Pradines B, Rogier C, Boukhary A, Hafid JE, Salem M, Trape JF, Basco LK, Briolant S. Vivax malaria in Mauritania includes infection of a Duffy-negative individual. Malar. J. 2011;10:8. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-10-336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Taye A, Hadis M, Adugna N, Tilahun D, Wirtz RA. Biting behavior and Plasmodium infection rates of Anopheles arabiensis from Sille, Ethiopia. Acta Trop. 2006;97:50–54. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vafa M, Troye-Blomberg M, Anchang J, Garcia A, Migot-Nabias F. Multiplicity of Plasmodium falciparum infection in asymptomatic children in Senegal: relation to transmission, age and erythrocyte variants. Malar. J. 2008;7:17. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-7-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mason SJ, Miller LH, Shiroishi T, Dvorak JA, McGinniss MH. The Duffy blood group determinants: their role in the susceptibility of human and animal erythrocytes to Plasmodium knowlesi malaria. Br. J. Haematol. 1977;36:327–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1977.tb00656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Obaldia N, 3rd, Meibalan E, Sa JM, Ma S, Clark MA, Mejia P, Moraes Barros RR, Otero W, Ferreira MU, Mitchell JR, et al. Bone marrow is a major parasite reservoir in Plasmodium vivax infection. MBio. 2018;9:1–10. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00625-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bango ZA, Tawe L, Muthoga CW, Paganotti GM. Past and current biological factors affecting malaria in the low transmission setting of Botswana: A review. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2020;85:104458. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2020.104458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chan LJ, Dietrich MH, Nguitragool W, Tham WH. Plasmodium vivax reticulocyte binding proteins for invasion into reticulocytes. Cell Microbiol. 2020;22:e13110. doi: 10.1111/cmi.13110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data related to this study are available in this manuscript.