Abstract

Background

Diabetic nephropathy (DN) is characterized by albuminuria and accumulation of extracellular matrix (ECM) in kidney. Transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) plays a central role in promoting ECM accumulation. We aimed to examine the effects of EW-7197, an inhibitor of TGF-β type 1 receptor kinase (ALK5), in retarding the progression of DN, both in vivo, using a diabetic mouse model (db/db mice), and in vitro, in podocytes and mesangial cells.

Methods

In vivo study: 8-week-old db/db mice were orally administered EW-7197 at a dose of 5 or 20 mg/kg/day for 10 weeks. Metabolic parameters and renal function were monitored. Glomerular histomorphology and renal protein expression were evaluated by histochemical staining and Western blot analyses, respectively. In vitro study: DN was induced by high glucose (30 mM) in podocytes and TGF-β (2 ng/mL) in mesangial cells. Cells were treated with EW-7197 (500 nM) for 24 hours and the mechanism associated with the attenuation of DN was investigated.

Results

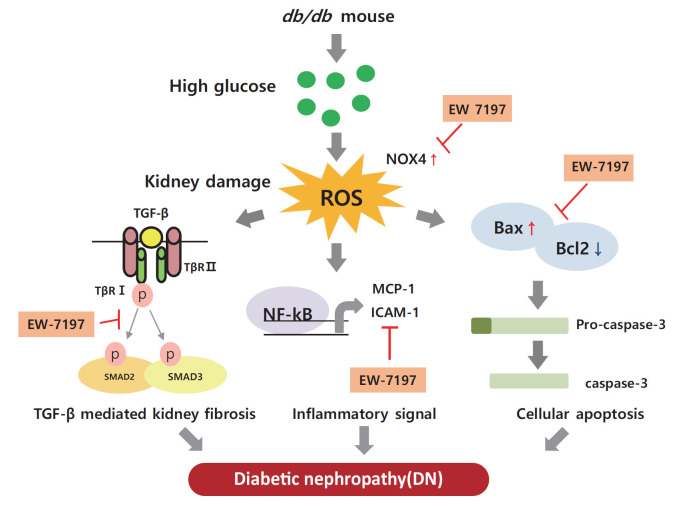

Enhanced albuminuria and glomerular morphohistological changes were observed in db/db compared to that of the nondiabetic (db/m) mice. These alterations were associated with the activation of the TGF-β signaling pathway. Treatment with EW-7197 significantly inhibited TGF-β signaling, inflammation, apoptosis, reactive oxygen species, and endoplasmic reticulum stress in diabetic mice and renal cells.

Conclusion

EW-7197 exhibits renoprotective effect in DN. EW-7197 alleviates renal fibrosis and inflammation in diabetes by inhibiting downstream TGF-β signaling, thereby retarding the progression of DN. Our study supports EW-7197 as a therapeutically beneficial compound to treat DN.

Keywords: Diabetic nephropathies, Glomerular mesangial cells, Podocytes, Transforming growth factor beta, Activin receptor-like kinase 5

Graphical abstract

INTRODUCTION

The number of people with diabetes is increasing worldwide because of the increased prevalence of obesity in the population [1]. Diabetic nephropathy (DN) is a leading cause of mortality in diabetic patients. This chronic kidney disease (CKD) is associated with progressive renal interstitial fibrosis, leading to end-stage renal disease [2,3]. Increased albuminuria, decreased glomerular filtration rate, high blood pressure, and progressive renal failure are characteristic features of DN [4,5]. Diabetes affects all types of renal cells, including podocytes, endothelial, tubulointerstitial, and mesangial cells [6]. Molecular mechanisms inducing DN include multiple factors, such as hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia, and impaired insulin signaling [7–9]. In diabetics, chronic hyperglycemia causes glycosylation of amino acids in the blood or tissues to form glycated complexes, called advanced glycation end products [10]. Advanced glycation end products act on cells to produce various hormones, free radicals, and cytokines, and induced infiltration of inflammatory cells, and accumulation of extracellular matrix (ECM) [11]. In the cell membrane, diacylglycerol, a glucose metabolite, activates diverse signaling pathways. By activating protein kinase C, increases the production of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and activates transcription factors such as nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and plasminogen activator inhibitor [12]. By phosphorylating mitogen-activated protein kinase at threonine and tyrosine residues, it activates transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) signaling resulting in tissue inflammation and vascular damage [13]. Accordingly, vascular damage of renal glomeruli and tubules, enhanced inflammatory mediators and cytokines, and accumulation of growth factors promote proliferation of mesangial cells, increasing the thickness of the glomerular basement membrane (GBM) and damaging foot podocytes. This leads to increased glomerular filtration rate, blood pressure, and albumin excretion [14,15] causing renal injury. Progression of DN eventually results in loss of functional nephrons, decreased glomerular filtration rate, mesangial expansion, enhanced proliferation, accumulation of ECM, glomerulosclerosis, tubular atrophy, and interstitial fibrosis [16]. Thus, through targeting the overexpression and/or regulation of TGF-β, a primary cause of glomerular matrix expansion can be exploited as a promising treatment option for renal fibrosis and cancer [17,18].

In the diabetic kidney, diverse pathways associated with the activation of TGF-β play an important role in the pathogenesis and progression of DN. Several studies in different models have proven that elevated glucose levels can stimulate TGF-β production [19–21]. In addition, there are studies confirming that TGF-β is increased, including renal fibrosis, in the db/db mouse model [22,23]. Therefore, we conducted a study to confirm the improvement of renal function through the db/db mouse model as an animal study. In vitro, podocytes were treated with high glucose (HG) to increase TGF-β, and in mesangial cells, renal fibrosis was induced by direct treatment with mouse recombinant TGF-β.

EW-7197 (vactosertib), a small molecule inhibitor of TGF-β type I receptor, inhibits hypoxia-inducible factor 1 α (HIF1-α), TGF-β/SMAD, and reactive oxygen species (ROS), and prevents heart and lung fibrosis [24–26]. However, the role and efficacy of this inhibitor in preventing renal damage in type 2 diabetes still needs to be elucidated. The present study aimed to confirm the role and efficacy of EW-7197 in effectively restoring renal function by regulating fibrosis, apoptosis, and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress in db/db mice.

METHODS

Reagent

N-[[4-([1,2,4]Triazolo[1,5-a]pyridin-6-yl)-5-(6-methylpyridin-2-yl)-1H-imidazol-2-yl]methyl]-2-fluoroaniline (EW-7197) was kindly provided by Dr. D.K. Kim (Ewha Womans University, Seoul, Korea). EW-7197 stock solution (10 mM) was prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, Kanto Chemical Co., Tokyo, Japan). For in vitro experiments, the substock (0.5 mM) was directly dissolved in the respective culture media.

Animals

All experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Yonsei University Wonju College of Medicine (YWC-170118-1).

Six-week-old nondiabetic (db/m) and diabetic (db/db) (C57BL/KsJ) mice weighing 20 to 23 g were purchased from Daehan Bio Link Co. (Eumseong, Korea). The mice were acclimatized for 2 weeks to a constant room temperature of (25°C±2°C), 60%±5% humidity, and 12-hour light/dark cycle, with free access to water and regular rodent chow. Thereafter, the mice were randomly divided into four groups (n=10 in each group): normal control (db/m), leptin receptor-deficient type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM, db/db), leptin receptor-deficient T2DM with EW-7197 at 5 mg/kg/day (db/db+EW5), leptin receptor-deficient T2DM with EW-7197 at 20 mg/kg/day (db/db+EW20). For oral administration, EW-7197 was prepared by diluting concentrated gastric fluid (dd H2O 900 mL, HCl 7 mL, NaCl 2.0 g, pepsin 3.2 g) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at a ratio of 1:10. For the db/m and db/db+vehicle groups, we administered a solution of gastric fluid and PBS in a 1:10 ratio.

Bodyweight and food intake were measured every week during the experimental period. Ten weeks post-EW-7197 oral administration, serum and tissue samples were collected and stored for further use.

Metabolic parameters

Serum triglyceride (TG) and total cholesterol (TC) were measured using commercially available assay kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions (ASAN Pharmaceutical, Seoul, Korea). Blood was collected from the tip of the tail vein and the glucose level was measured using a glucometer (Auto-Check, Diatech Korea Co., Seoul, Korea) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Fasting blood glucose was measured after 6 hours of daytime fasting. Insulin (0.75 U/kg body weight; Humulin R, Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, IN, USA) was injected intraperitoneal for the insulin tolerance test. Blood glucose concentrations were measured at 0, 15, 30, 60, 90, and 120 minutes post-treatment.

Cell culture

Mouse mesangial cells (MES-13) were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). The cells were cultured in low-glucose Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, HyClone, Logan, UT, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco, Waltham, MA, USA) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco). For the experiments, cells were treated with mouse TGF-β (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) at 2 ng/mL and EW-7197 at 500 nM for 24 hours.

Conditionally immortalized mouse podocytes were kindly provided by Dr. Peter Mundel [27]. The cells were grown on type I collagen-coated 100-mm dishes (Sigma-Aldrich, Burlington, MA, USA). To enhance the expression of a thermo-sensitive T antigen, the podocytes were cultured at 33°C to proliferate in low-glucose DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, penicillin (100 U/mL), streptomycin (100 μg/mL), and mouse recombinant interferon-γ (10 U/mL, Sigma-Aldrich). To induce differentiation, podocytes were cultured at 37°C in low-glucose DMEM supplemented with 5% FBS, penicillin (100 U/mL), streptomycin (100 μg/mL) in the absence of interferon-γ for 14 days. During the experiments, cells were treated with HG (30 mM) for 24 hours.

Immunofluorescence

The cultured MES-13 cells were fixed in fixation buffer (BD cytofix, BD bioscience, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) at 37°C for 15 minutes and washed with PBS. After that, cells were treated with 0.1% triton x-100 (T8787, Sigma-Aldrich) for 20 minutes. The primary antibody diluted with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA, 1:200, 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine [8-OHdG], SC-66036, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) was added to cells and incubated overnight at 4°C. The secondary antibody was diluted with 3% BSA (1:500, anti-mouse immunoglobulin G, Alexa Fluor 488, #4408, Cell Signaling, Danvers, M, USA) and incubated with cells for 1 hour at 22°C to 24°C. A 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; 1 mg/mL stock solution; ab228549, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) was diluted to 1 mL/0.5 μL and incubated with cells for 15 minutes at 22°C to 24°C. After washing, cells were mounted (Immu-Mount, FS9990402, Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and intracellular ROS generation was measured by incubating podocytes with chloromethyl-H2-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (CM-H2DCF-DA, D399, Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA). In the presence of intracellular ROS, this dye quickly oxidizes to fluorescent 2, 7-dichlorofluorescein (DCF) and produces a bright fluorescent light. Podocytes plated on type I collagen-coated glass dish were treated with 10 μM CM-H2DCF-DA in a light-protected 5% CO2-humidified incubator at 37°C for 30 minutes. After incubation, podocytes were washed three times with Dulbecco’s Phosphate Buffered Saline (DPBS, LB 001-01, Welgene, Gyeongsan, Korea) in a darkroom. Next, podocytes were incubated with the primary antibody, fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-phalloidin (P5282, Sigma-Aldrich) in a light-protected incubator at 37°C for 2 hours. Next, using DPBS, the cells were washed three times in a darkroom. Samples were counterstained using DAPI (H-1500, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA).

Renal function test

Urine was collected for 24 hours from mice housed in metabolic cages every 4 weeks and for the last 2 weeks before the end of the experiment. In the metabolic cages, mice had access to water ad libitum, although no access to food was provided. Renal function tests included analyses of urinary albumin, creatinine, and albumin to creatinine ratio (ACR, Exocell, Logan Township, NJ, USA).

Histological examination

Glomeruli were analyzed for the glomerular area, glomerular volume, and Bowman’s space area by staining paraffin-embedded kidney tissue sections with hematoxylin and eosin. Glomerular mesangial expansion was measured as periodic acid Schiff stained area. The percentage of the mesangial matrix occupied by each the glomeruli were rated on a 5-point scale from 0 to 4 as follows: Grade 0, normal glomeruli; Grade 1, mesangial expansion area up to 25%; Grade 2, 25% to 50%; Grade 3, 50% to 75%; and Grade 4, >75% [28]. Glomerular histopathology and renal fibrosis were evaluated by immunohistochemical (IHC) staining of nephrin, collagen IV, and fibronectin. Hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid Schiff, sirius red, Masson’s trichrome stained sections were visualized using an optical microscope equipped with a charge-coupled device camera at ×400 magnification (Pulnix, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). For transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analyses, the renal cortex was partially excised and immersed in the buffer solution. TEM was used to analyze the thickness of the GBM, slit pore density, and width of foot podocytes at ×15,000 magnification.

Western blot analyses

Renal expression of proteins were evaluated by performing Western blot analysis using specific antibodies against synaptophodin (163-002, Synaptic Systems, Göttingen, Germany), nephrin (GP-N2, Progen Biotechnik, Heidelberg, Germany), collagen IV (SC-11360, Santa Cruz), fibronectin (SC-6952, Santa Cruz), TGF-β (SC-146, Santa Cruz), α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA, SC-32251, Santa Cruz), p-Smad2/3 (#8828, Cell signaling), Smad2/3 (#3102, Cell signaling), VEGF (SC-65617, Santa Cruz), connective tissue growth factor (CTGF, SC-365970, Santa Cruz), phosphorylated NF-κB (p-NF-κB, #3033, Cell signaling), NF-κB (#4764, Cell signaling), monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1, SC-28879, Santa Cruz), intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1, SC-7891, Santa Cruz), NADPH oxidase 4 (NOX4, SC-30141, Santa Cruz), nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2, SC-722, Santa Cruz), heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1, SC-136960, Santa Cruz), activating transcription factor 6 alpha (ATF6α, SC-22799, Santa Cruz), Bcl2 associated X (Bax, SC-7480, Santa Cruz), caspase-3 (SC-271759, Santa Cruz), B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl2, SC-7382, Santa Cruz), and β-actin (SC-47778, Santa Cruz).

Renal cortex tissues homogenized in protein lysis buffer (EBA-1149, Elpis Biotech, Daejeon, Korea) were centrifuged at 13,000 ×g for 20 minutes. The supernatants were mixed with the sample buffer and heated at 95°C for 5 minutes. Sample aliquots containing 15 to 30 μg of protein were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis using 8% to 12% gels. The resolved protein bands were transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. The membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies, washed three times in tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween-20, and finally incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies at 22°C to 24°C for 1 hour.

In the case of nuclear extraction, it is necessary to separate the cytosol protein. When harvesting cells, use a solution to which 10 mM Hydroxyethyl piperazine ethane sulfonicacid (HEPES), 10 mM potassium chloride (KCl), 0.1 mM ethylene-diamine-tetraacetic acid (EDTA), and 0.1 mM ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid (EGTA) have been added, and add 10% nonidet P40 ethylphenolpoly (NP-40) solution to the cell collection solution and voltexing. Centrifuge the solution at 4°C and 13,000 rpm for 5 minutes to collect only the pellets. The removed at this time is cytosol protein. Then, 20 mM HEPES, 0.4 M Nacl, 1 mM EDTA, and 1 mM EGTA were added to the pellet to extract proteins from the nucleus.

The protein bands were visualized using the enhanced chemiluminescence gel electrophoresis system (Amersham Biosciences, Amersham, UK). The intensity of the bands was measured using the Image J software version 1.50i (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as the mean±standard error of the mean. Statistical analyses used for multiple comparisons included one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Turkey’s test. Data were analyzed using the SPSS software version 20.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA). P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

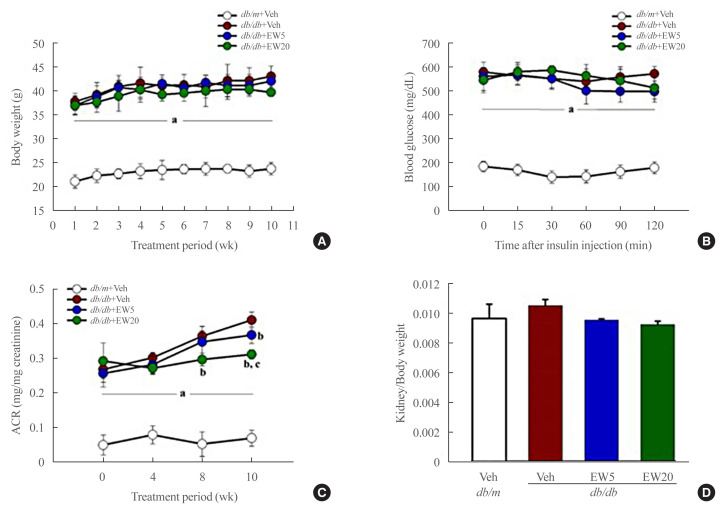

Renoprotective effect of EW-7197 is independent of metabolic regulation in db/db mice

A significant increase was seen in body weight, serum glucose, TG, and TC in db/db mice as compared to the db/m group after 10 weeks. EW-7197 treatment did not inhibit the above metabolic parameters (Table 1) or affect food intake or insulin tolerance in db/db mice (Fig. 1A, B). However, EW-7197 improved renal function by urinary ACR in the db/db+EW20 group (Fig. 1C, D) compared to the db/m group. Taken together, these results suggest a direct renoprotective role of EW-7197 that is independent of metabolic regulation.

Table 1.

EW-7197 Doesn’t Affect Metabolic Parameters

| Group | BW, g | Serum glucose, mg/dL | TG, mg/dL | TC, mg/dL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| db/m+Veh | 23.95±1.30 | 133.40±13.21 | 59.86±8.52 | 109.40±22.91 |

| db/db+Veh | 42.38±3.17a | 496.60±45.96a | 137.70±12.50a | 157.64±10.26a |

| db/db+EW5 | 42.36±1.92a | 483.22±47.65a | 129.40±3.99a | 162.51±5.39a |

| db/db+EW20 | 41.08±3.94a | 495.72±27.03a | 131.15±16.97a | 154.94±6.20a |

Values are expressed as mean±standard error of the mean. The changes of BW, serum glucose, TG, and TC.

BW, body weight; TG, triglyceride; TC, total cholesterol.

P<0.05 vs. db/m controls group. Each group (n=6–8/group).

Fig. 1.

EW-7197 has no effect on insulin tolerance but in kidney function. (A) Bodyweight was monitored throughout experimental period. (B) Intraperitoneal insulin tolerance test were performed after 10 weeks of EW-7197 treatment. (C) Urinary albumin/creatinine (ACR) ratios were measured 24-hour urine collection in metabolic cage. (D) Kidney weight/body weight in all experimental groups. Each group (n=6–8/group). aP<0.05 vs. db/m controls; bP<0.05 vs. db/db controls; cP<0.05 vs. db/db+EW5 mg/kg/day.

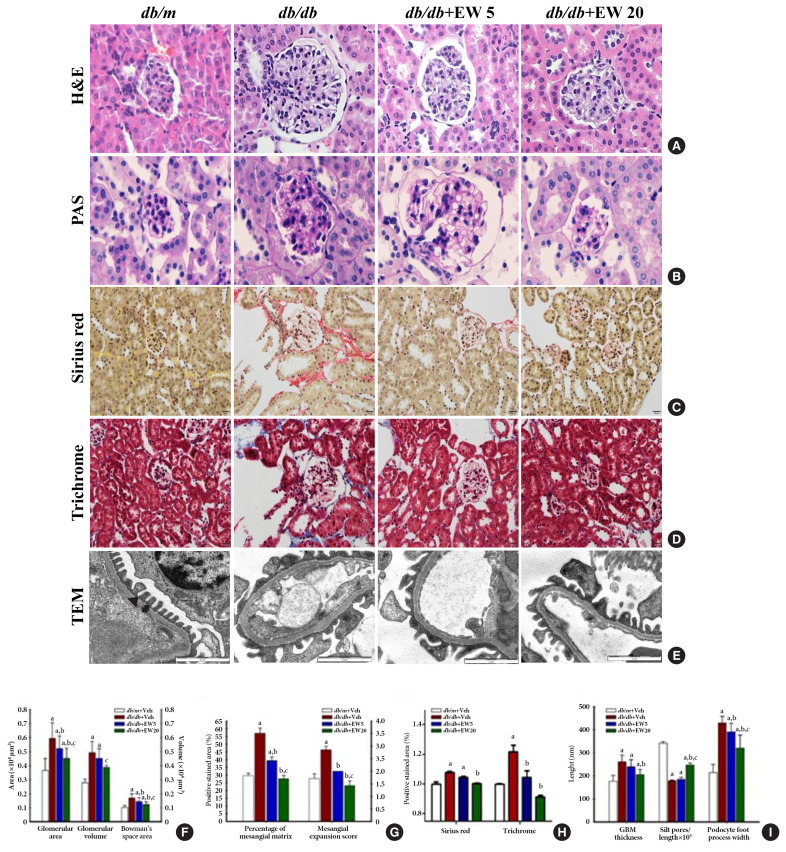

EW-7197 attenuates glomerular hypertrophy and fibrosis in db/db mice

Hypertrophy was detected in the glomeruli and podocytes on examination of hematoxylin and eosin and periodic acid Schiff stained samples respectively, in db/db mice (Fig. 2A, B). EW-7197 significantly reduced the glomerular area, glomerular volume, and Bowman’s space area (Fig. 2F). Mesangial expansion was measured as a percentage of the area stained with periodic acid Schiff. The mesangial expansion score is calculated based on the description in method (Fig. 2G). EW-7197 also showed improvement of renal fibrosis in db/db mice via sirius red and trichrome staining (Fig. 2C, D, H). In db/db mice, EW-7197 effectively improved the renal function by increasing the GBM thickness and foot width of podocytes and disrupting the slit pores compared to the db/m mice via ultrastructure studies (Fig. 2E, I). EW-7197-treatment effectively improved renal function in diabetic mice as evident from the decreased GBM thickness and foot width of podocytes, and the increased number of slit pores.

Fig. 2.

EW-7197 reduces glomerular hypertrophy and fibrosis in db/db mice. (A, B) Glomerular hypertrophy was determined in hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and periodic acid Schiff (PAS) stained glomeruli from diabetic mice. (F) Changes in glomerular area, glomerular volume, Bowman’s space area, (G) percentage of mesangial matrix and mesangial expansion score. (C, D, H) Sirius red, trichrome staining were performed to check the degree of fibrosis of the glomerular (original magnification, 400×). (E) Ultrastructure of glomerular basement membrane (GBM). The GBM thickness, filtration silt pores, and foot process width of podocytes (I) were analyzed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) at 15000-X magnification. An arrowhead indicates filtration slit pore; a up-down arrow shows GBM thickness (n=2/group). aP<0.05 vs. db/m controls; bP<0.05 vs. db/db controls; cP<0.05 vs. db/db+EW5 mg/kg/day.

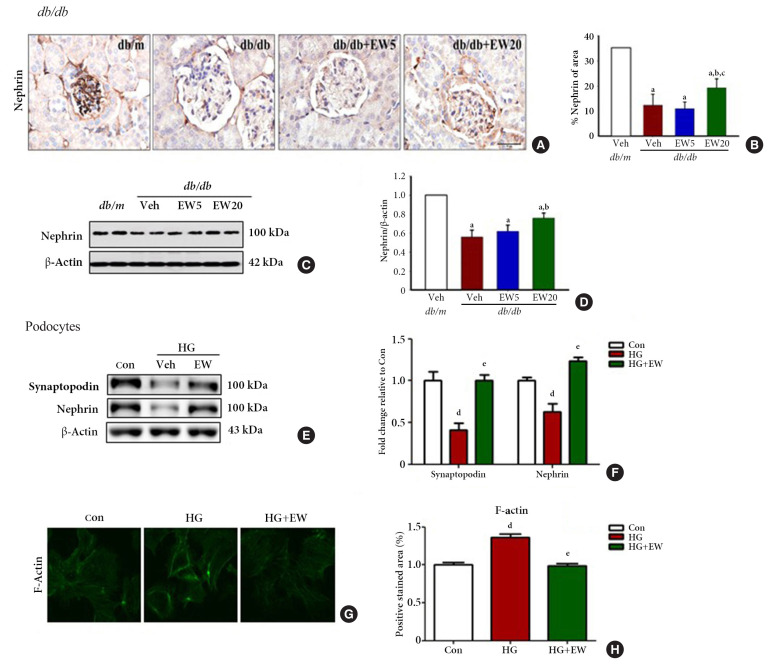

EW-7197 inhibits nephrin loss in diabetic glomeruli and podocytes

Nephrin, a transmembrane protein and structural component of the slit diaphragm, is required for the proper functioning of the renal filtration barrier and is decreased in the diabetic kidney [29]. The kidney function of mice in different experimental groups was analyzed based on the extent of nephrin staining in the kidney tissue through IHC. Nephrin staining was significantly decreased in the db/db group compared to that of the db/m group, where it was reconfirmed as positively stained areas (Fig. 3A, B). Accordingly, decreased levels of nephrin were detected in the renal cortex and podocytes of db/db compared to that of the db/m group by Western blotting (Fig. 3C-F, respectively). In podocytes treated with HG, EW-7197-treatment restored the levels of synaptopodin and nephrin.

Fig. 3.

EW-7197 protects against nephrin loss from diabetic glomeruli and podocytes. (A) Immunohistochemistry of renal nephrin, (B) the percentage of positively stained area. Original magnification is 400× (scale bar=50 μm). (C, D) By Western blot protein expression of nephrin were analyzed from diabetic mice (n=4–5/group). (E, F) After treatment with high glucose (HG, 30 mM) and EW (500 nM) in podocytes, the protein expression of synaptopodin and nephrin was confirmed by Western blot. (G, H) F-actin stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-phalloidin and positive stained area. aP<0.05 vs. db/m controls; bP<0.05 vs. db/db controls; cP<0.05 vs. db/db+EW5 mg/kg/day; dP<0.05 vs. controls; eP<0.05 vs. high glucose.

Structural changes in podocytes were analyzed by measuring f-actin levels as detected by IHC. F-actin is a contractile cytoskeleton protein that regulates the filtration surface area; it is involved in the maintenance of structural integrity and is a modulator of glomerular expansion [30]. F-actin levels were significantly decreased in EW-7197-treated compared to that of HG-treated podocytes, where it was increased (Fig. 3G, H). Taken together, these results indicate the role of EW-7197 in ameliorating the structural and functional changes associated with DN.

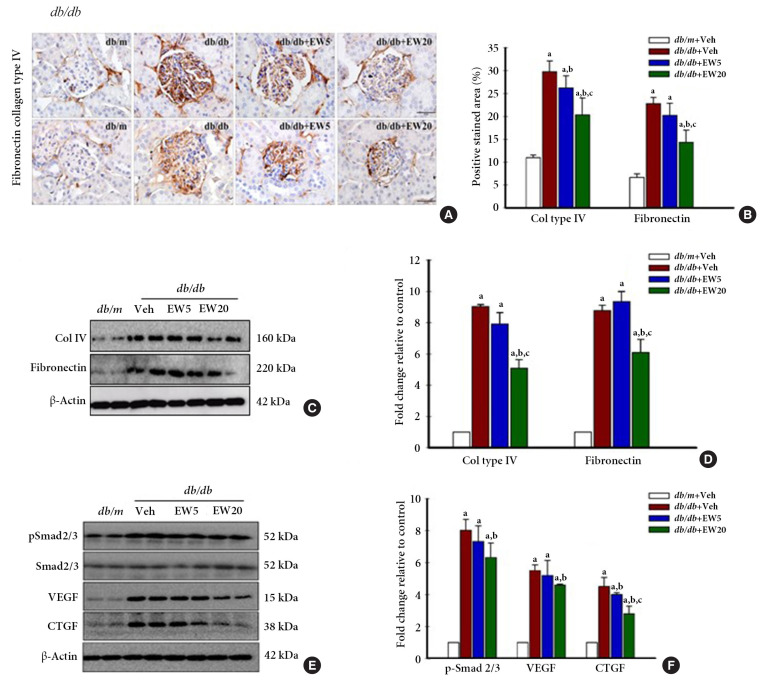

EW-7197 down-regulates the expression of fibrogenic mediators in db/db mice, in vivo

Renal fibrosis is a histological feature of CKD characterized by excessive accumulation of ECM. ECM proteins that are abundantly expressed in the kidney include collagen IV and fibronectin [31]. IHC analyses detected the presence of a positively stained area corresponding to the fibrosis markers collagen IV and fibronectin in vivo (Fig. 4A, B). Western blotting confirmed the expression of collagen IV and fibronectin (Fig. 4C, D), together with the fibrogenesis markers p-Smad 2/3, VEGF, and CTGF in the renal tissue of db/db mice (Fig. 4E, F). EW-7197-treatment effectively reduced the expression of fibrotic markers in the db/db mice.

Fig. 4.

EW-7197 down-regulates the expression on fibrogenic mediators in diabetic mice. (A) Immunohistochemistry of renal collagen IV and fibronectin, (B) positively stained area. Original magnification is 400× (scale bar=50 μm). (C, D) By Western blot of renal cortex protein expression of col IV and fibronectin. (E, F) The expression of Smad2/3, p-Smad 2/3, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) as proteins related to fibrosis was confirmed, respectively from diabetic mice (n=4–5/group). aP<0.05 vs. db/m controls; bP<0.05 vs. db/db controls; cP<0.05 vs. db/db+EW5 mg/kg/day.

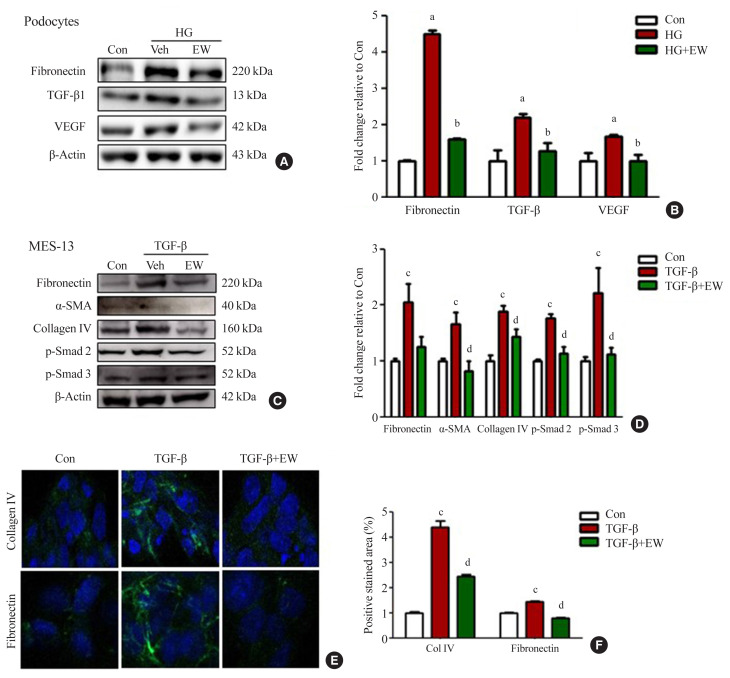

EW-7197 down-regulates the expression of fibrotic markers in podocytes and mesangial cells in vitro

Anti-fibrotic effects of EW-7197 were evaluated in podocytes and MES-13 cells. In podocytes, HG treatment induced enhanced expression of TGF-β, fibronectin, and VEGF whereas EW-7197 treatment inhibited their expression (Fig. 5A, B). In line with the effects seen in podocytes, EW-7197 significantly reduced the TGF-β induced expression of fibronectin, α-SMA, and collagen IV in MES-13 cells. In addition, TGF-β mediated enhanced expression of fibronectin and collagen IV were significantly reduced by EW-7197 in MES-13 cells (Fig. 5C, D). The differential expression of collagen IV and fibronectin was confirmed by immunostaining in MES-13 cells (Fig. 5E, F). These results suggest EW-7197 mediated regulation of TGF-β signaling in the inhibition of cellular fibrosis.

Fig. 5.

EW-7197 down-regulates the expression of fibrosis markers in podocyte and mesangial cell lines. (A, B) Podocyte fibrosis marker; fibronectin, transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) was detected by Western blots and quantified values. (C, D) Changes in extracellular matrix (ECM) through fibronectin, α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), and collagen type IV were detected by mesangial cell Western blot. (E, F) Immunofluorescence of fibronectin and collagen type IV and positive stained area. MES-13, mouse mesangial cells. aP<0.05 vs. controls; bP<0.05 vs. high glucose; cP<0.05 vs. controls; dP<0.05 vs. TGF-β.

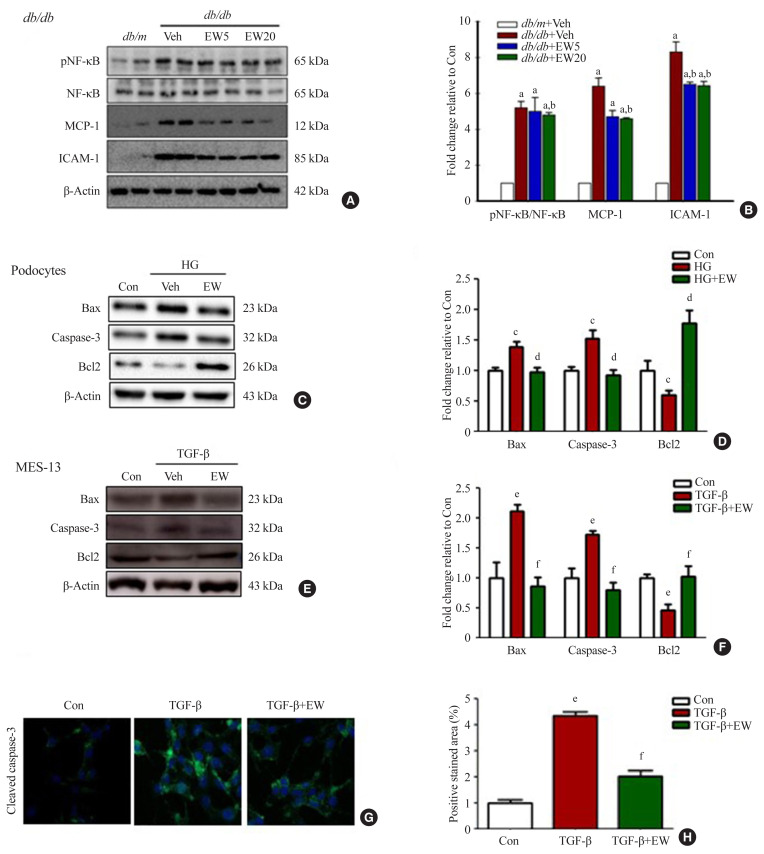

EW-7197 inhibits inflammatory responses and cell death

In the renal cortex of diabetic mice, protein expression of inflammatory response-associated markers, including p-NF-κB, NF-κB, MCP-1, and ICAM-1, were analyzed (Fig. 6A, B). EW-7197 treatment significantly reduced the inflammatory response in renal tissue. The effect of EW-7197 on apoptosis, pro-apoptotic, and anti-apoptotic markers was analyzed by Western blot and immunofluorescence. As compared to HG-treated podocytes, EW-7197 treatment significantly decreased the expression of apoptotic cell markers, Bax, and caspase-3. In addition, HG-induced reduced expression of Bcl2 was significantly recovered by EW-7197 treatment (Fig. 6C, D). In line with the effect seen in podocytes, EW-7197 effectively inhibited apoptosis in MES-13 cells (Fig. 6E, F). TGF-β induced cleaved caspase-3 expression was significantly inhibited by TGF-β treatment (Fig. 6G, H). Taken together, these results indicate the anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic role of EW-7197 in DN.

Fig. 6.

EW-7197 inhibits the inflammatory response and prevents cell death. (A, B) Protein expression in the renal cortex of diabetic mice, a marker related to the inflammatory response; phosphorylated nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (p-NF-κB), NF-κB, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), and intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1). (C, D) Expression of proteins such as, Bcl2 Associated X (Bax) and caspase-3 were investigated using Western blot and fold change relative to control. Anti-apoptotic B-cell lymphoma/leukemia-2 (Bcl2) an apoptosis-related marker, in podocytes. (E, F, G, H) Expression of apoptosis-related proteins and immunofluorescence staining in mesangial cells. MES-13, mouse mesangial cells. aP<0.05 vs. db/m controls; bP<0.05 vs. db/db controls; cP<0.05 vs. controls; dP<0.05 vs. high glucose; eP<0.05 vs. controls; fP<0.05 vs. TGF-β.

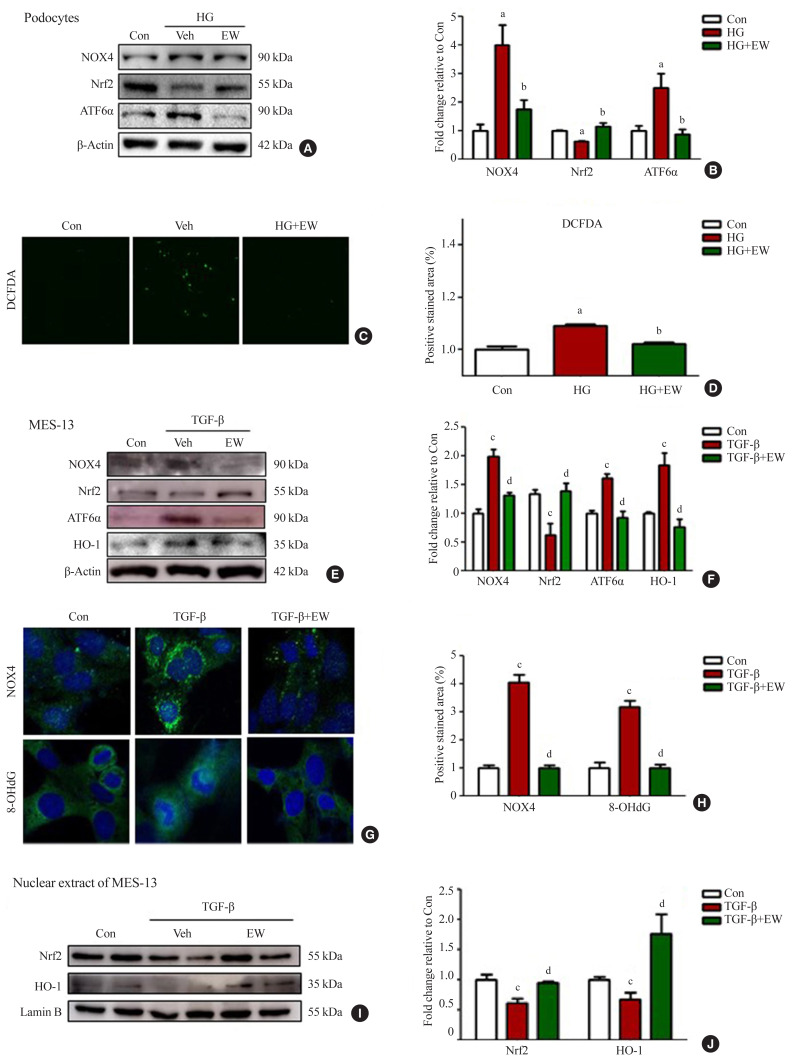

EW-7197 ameliorates oxidative and ER stress in HG-treated podocytes and mesangial cells

Stimulation with HG decreased Nrf2 levels and increased those of NOX4, ROS, and ATF6α, an ER stress marker in podocytes. As compared to HG, the above changes improved following EW-7197 treatment (Fig. 7A, B). Measurement of ROS by CM-H2DCF-DA staining revealed EW-7197-mediated ameliorated DCF-DA levels in HG-treated podocytes (Fig. 7C, D). In MES-13 cells, ROS and ER stress indicator levels were measured after stimulation with TGF-β. EW-7197 not only reduced ROS through NOX4 and Nrf2-HO-1 regulation, but also reduced ER stress by inhibiting ATF6α (Fig. 7E, F). In addition, TGF-β-induced NOX4 and 8-OHdG expression were inhibited by EW-7197 (Fig. 7G, H). Nrf2 moves into the nucleus and increases the transcription of genes related to ROS detoxification (Fig. 7I, J). Thus, EW-7197 inhibited TGF-β induced renal fibrosis by reducing oxidative stress.

Fig. 7.

EW-7197 ameliorates renal reactive oxygen species (ROS) and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress. (A, B) Expression of ROS related proteins such as NAD(P)H oxidase 4 (NOX4) and ER stress markers; nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor (Nrf2) and, transcription factor 6 alpha (ATF6α) in podocytes. (C, D) ROS measurements in podocytes with CM-H2DCF-DA. (E, F) Expression of NOX4 and ER stress-related proteins in mesangial cells. (G, H) ROS generation in mesangial cells by immunofluorescence staining with NOX4 and 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine (8-OHdG). (I, J) The expression of Nrf2, heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), and Lamin B was confirmed by extracting the protein from the nucleus. HG, high glucose; MES-13, mouse mesangial cells; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-β. aP<0.05 vs. controls; bP<0.05 vs. high glucose; cP<0.05 vs. controls; dP<0.05 vs. TGF-β.

DISCUSSION

DN is a common complication seen in diabetic patients. Diverse signal transduction pathways are associated with the progression of DN, such as mammalian rapamycin target (mTOR), extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), ER stress, TGF-β, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT). Activation of these signaling pathways is thought to play an important role in the pathogenesis of DN [32]. Among the hallmarks of DN, loss of function accompanying tissue damage is attributed to renal interstitial fibrosis [33].

TGF-β is a cytokine with multiple roles associated with wound healing, angiogenesis, immune regulation, and cancer. During wound healing, enhancement of TGF-β levels induces tissue fibrosis. Increased TGF-β levels activate fibrotic diseases by regulating the phenotype and function of fibroblasts and promote the accumulation of ECM proteins, thereby leading to organ failure [34].

HG-induced overexpression of ROS is an integrated mechanism linked to diabetic complications [35]. HG-stimulated ROS production increases the expression of TGF-β, Akt, and phosphorylation rates of mTOR, resulting in EMT [36]. EMT is involved in the pathways leading from the onset of DN to the establishment of renal interstitial fibrosis [37]. The ER is an essential organelle that aids the efficient folding and assembly of post-translational proteins [38]. In hyperglycemic conditions, excessive production of proteins overwhelms the ER protein-folding machinery and induces ER stress, contributing to renal cell damage and progression of DN [39].

Several studies have reported increased expression of TGF-β in experimental models of renal fibrosis [40]. Therefore, inhibiting TGF-β signaling is a promising therapeutic approach to prevent fibrosis. Accordingly, direct inhibition of TGF-β receptor type 1 (ALK5), is an effective therapeutic strategy in preventing TGF-β-induced fibrosis in breast cancer [41]. Several bioavailable small molecule inhibitors of TGF-β receptor kinase have been designed to treat fibrosis and cancer via oral administration. One such inhibitor, EW-7197 was found to possess a superior anti-fibrotic effect compared to the others [24].

In db/db mice, glomerular surface area and mesangial matrix area were increased at around 12 weeks of age and albuminuria was prominent after 8 weeks. The fibrosis-related factors, such as collagen IV and fibronectin, were enhanced with age [42]. In the present study, oral administration of EW-7197 at 5 and 20 mg/kg did not significantly affect body weight, food intake, serum glucose, TG, and TC in db/m and db/db mice. However, it significantly decreased the ACR in a dose-dependent manner, thereby affecting renal function, which was confirmed by renal morphology. EW-7197 significantly inhibited the expansion of mesangial tissue through the glomerular area, glomerular volume, and Bowman’s space area. In addition, EW-7197 aided the reduction in podocyte foot width and GBM thickness, and increased slit pores length.

The db/db mouse model showed increased expression of collagen IV and fibronectin, both indicative of induction of renal fibrosis. In addition, activation of the canonical pathway, represented by p-Smad2/3, VEGF, and CTGF levels that destabilize endothelial cells, plays an important role in the development and progression of DN [43]. In this study, EW-7197 prevented TGF-β mediated renal fibrosis and alleviation of nephropathy in the db/db mouse model, suggesting its role as an attractive therapeutic strategy for the treatment of fibrotic diseases. Similar to the db/db mouse model, renal cell fibrosis was induced in kidney cells with HG and TGF-β. Mouse podocytes treated with HG levels showed enhanced expression of TGF-β and fibrosis-related factors. Stimulation of MES-13 with TGF-β initiates both the canonical and non-canonical pathways, thereby exerting multiple biological effects. In advanced renal fibrosis, Smad signaling is a major pathway associated with TGF-β signaling and is substantially activated during fibrosis [44]. Renal mesangial cell fibrosis resulting from TGF-β mediated enhanced expression of p-Smad2/3 and ECM-related proteins fibronectin, α-SMA, and collagen IV was effectively restored by EW-7197. Thus, EW-7197-mediated targeting of TGF-β/Smad3 signaling could be a specific and effective treatment strategy for CKD associated with renal fibrosis.

In the present study, EW-7197 effectively prevented the enhanced expression of inflammatory cytokines, NF-κB, MCP-1, and ICAM-1, a VEGF, suggesting the anti-inflammatory role of EW-7197 in db/db mice. The expression of Bax, Bcl2, and caspase-3 was analyzed to study the beneficial effect of EW-7197 on renal cell death. Bax/Bcl2 is an indicator of response to the apoptotic signal and subsequent activation [43]. TGF-β-mediated enhanced cell death increased expression of Bax and caspase-3 and decreased Bcl2 expression were inhibited by EW-7197, indicating its protective anti-apoptotic effect on renal cells in DN.

Normal physiological conditions are maintained in cells by an oxidizer/antioxidant balance. The impairment of this balance associated with the pathogenesis of diabetes generates ROS and results in oxidative stress [45]. In the present study, the expression level of Nrf2, a key regulator of cellular redox response, was reduced by TGF-β. In normal condition, Nrf2 is expressed in the cytoplasm and it bound to the keap1 [46]. Oxidative stress dissociates the Nrf2-keap1 complex and Nrf2 translocated to the nucleus. In the nucleus, Nrf2 binds to antioxidant-response element sequences thus, induces the expression of antioxidant enzymes such as HO-1, NAD(P)H dehydrogenase quinone 1 and glutamate-cysteine ligase catalytic subunit [47]. In this study, we confirmed the Nrf2/keap-1/HO-1 expressions were significantly decreased by methionine choline deficient diet and combination treatment more recovered these expressions than CUR5-8 or EW-7197 single administration in the whole lysates of liver. In mouse podocytes and mesangial cells, HG or TGF-β stimulation also reduced Nrf2 expression in the whole lysates. HO-1 expression differently showed between cytoplasmic and nucleus. In whole lysates HO-1 significantly increased however, nucleic HO-1 was significantly decreased by TGF-β compared to normal condition. These changes were converted by EW-7197. The expressions of Nrf2 and HO-1 expressions are shown differently depending on the cell treatment condition. In some studies, TGF-β-mediated HO-1 induction counteracts the negative effects of TGF-β1 by blocking additional TGF-β1 production or affecting cell proliferation, apoptosis and ECM deposition [48]. In addition, TGF-β-mediated increases in ROS and NOX4 levels were significantly inhibited by EW-7197 in kidney cells. These findings are consistent with previous studies that reported reduced protein and mRNA levels of NOX components by EW-7197 both in vivo and in vitro [24,25]. Thus, EW-7197 could be therapeutically promising for the inhibition of the oxidative stress induced by TGF-β.

The ER plays an important role in deciding the fate and regulation of various cellular functions. In addition, the ER is highly sensitive to changes in cellular homeostasis; thus, ER stress is induced by several pathological conditions [49]. In DN, activation of TGF-β signaling induces ER stress in renal cells [50]. EW-7197 could significantly inhibit HG-mediated up-regulated expression of ATF6α, an ER stress marker in podocytes, suggesting its reno-protective effect.

Thus, the results of the present study suggest the role of EW-7197 as a new promising therapeutic compound for improving renal function and tissue fibrosis based on its ability to inhibit fibrosis and apoptosis induced by hyperglycemia, in addition to reducing ROS.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) (2018R1A2B6005360, 2021R1A2B5-B01002354). EW-7197 was generously provided by the Department of Pharmacy, College of Pharmacy, Ewha Womans University, Seoul, Korea

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception or design: K.B.H., W.S., A.R.J., E.S.L., H.M.K., S.S. Acquisition, analyses and interpretation of data: K.B.H., W.S. Drafting the work and revision: K.B.H., W.S. Final approval of the manuscript: U.K., D.K.K., E.Y.L., C.H.C.

REFERENCES

- 1.Elmarakby AA, Sullivan JC. Relationship between oxidative stress and inflammatory cytokines in diabetic nephropathy. Cardiovasc Ther. 2012;30:49–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5922.2010.00218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Susztak K, Raff AC, Schiffer M, Bottinger EP. Glucose-induced reactive oxygen species cause apoptosis of podocytes and podocyte depletion at the onset of diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes. 2006;55:225–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.He T, Xiong J, Nie L, Yu Y, Guan X, Xu X, et al. Resveratrol inhibits renal interstitial fibrosis in diabetic nephropathy by regulating AMPK/NOX4/ROS pathway. J Mol Med (Berl) 2016;94:1359–71. doi: 10.1007/s00109-016-1451-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sedeek M, Callera G, Montezano A, Gutsol A, Heitz F, Szyndralewiez C, et al. Critical role of Nox4-based NADPH oxidase in glucose-induced oxidative stress in the kidney: implications in type 2 diabetic nephropathy. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2010;299:F1348–58. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00028.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jerums G, Panagiotopoulos S, Premaratne E, MacIsaac RJ. Integrating albuminuria and GFR in the assessment of diabetic nephropathy. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2009;5:397–406. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2009.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maezawa Y, Takemoto M, Yokote K. Cell biology of diabetic nephropathy: roles of endothelial cells, tubulointerstitial cells and podocytes. J Diabetes Investig. 2015;6:3–15. doi: 10.1111/jdi.12255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li JJ, Kwak SJ, Jung DS, Kim JJ, Yoo TH, Ryu DR, et al. Podocyte biology in diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int Suppl. 2007;106:S36–42. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schena FP, Gesualdo L. Pathogenetic mechanisms of diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(Suppl 1):S30–3. doi: 10.1681/asn.2004110970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaneto H, Katakami N, Kawamori D, Miyatsuka T, Sakamoto K, Matsuoka TA, et al. Involvement of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of diabetes. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9:355–66. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bucala R, Vlassara H. Advanced glycosylation endproducts in diabetic renal disease: clinical measurement, pathophysiological significance, and prospects for pharmacological inhibition. Blood Purif. 1995;13:160–70. doi: 10.1159/000170199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolf G, Ziyadeh FN. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of proteinuria in diabetic nephropathy. Nephron Physiol. 2007;106:p26–31. doi: 10.1159/000101797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inoguchi T, Sonta T, Tsubouchi H, Etoh T, Kakimoto M, Sonoda N, et al. Protein kinase C-dependent increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in vascular tissues of diabetes: role of vascular NAD(P)H oxidase. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14(8 Suppl 3):S227–32. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000077407.90309.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haneda M, Kikkawa R, Sugimoto T, Koya D, Araki S, Togawa M, et al. Abnormalities in protein kinase C and MAP kinase cascade in mesangial cells cultured under high glucose conditions. J Diabetes Complications. 1995;9:246–8. doi: 10.1016/1056-8727(95)80013-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Londero TM, Giaretta LS, Farenzena LP, Manfro RC, Canani LH, Lavinsky D, et al. Microvascular complications of posttransplant diabetes mellitus in kidney transplant recipients: a longitudinal study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104:557–67. doi: 10.1210/jc.2018-01521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feng D, Ngov C, Henley N, Boufaied N, Gerarduzzi C. Characterization of matricellular protein expression signatures in mechanistically diverse mouse models of kidney injury. Sci Rep. 2019;9:16736. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-52961-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vallon V, Richter K, Blantz RC, Thomson S, Osswald H. Glomerular hyperfiltration in experimental diabetes mellitus: potential role of tubular reabsorption. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:2569–76. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V10122569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamamoto T, Nakamura T, Noble NA, Ruoslahti E, Border WA. Expression of transforming growth factor beta is elevated in human and experimental diabetic nephropathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:1814–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.5.1814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Voelker J, Berg PH, Sheetz M, Duffin K, Shen T, Moser B, et al. Anti-TGF-β1 antibody therapy in patients with diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28:953–62. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015111230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu Y, Usui HK, Sharma K. Regulation of transforming growth factor beta in diabetic nephropathy: implications for treatment. Semin Nephrol. 2007;27:153–60. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Whiteside CI, Dlugosz JA. Mesangial cell protein kinase C isozyme activation in the diabetic milieu. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2002;282:F975–80. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00014.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee TS, Saltsman KA, Ohashi H, King GL. Activation of protein kinase C by elevation of glucose concentration: proposal for a mechanism in the development of diabetic vascular complications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:5141–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.13.5141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Research Misconduct Found]

- 22.Hong YA, Lim JH, Kim MY, Kim TW, Kim Y, Yang KS, et al. Fenofibrate improves renal lipotoxicity through activation of AMPK-PGC-1α in db/db mice. PLoS One. 2014;9:e96147. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Juarez P, Vilchis-Landeros MM, Ponce-Coria J, Mendoza V, Hernandez-Pando R, Bobadilla NA, et al. Soluble betaglycan reduces renal damage progression in db/db mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;292:F321–9. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00264.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park SA, Kim MJ, Park SY, Kim JS, Lee SJ, Woo HA, et al. EW-7197 inhibits hepatic, renal, and pulmonary fibrosis by blocking TGF-β/Smad and ROS signaling. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2015;72:2023–39. doi: 10.1007/s00018-014-1798-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim MJ, Park SA, Kim CH, Park SY, Kim JS, Kim DK, et al. TGF-β type I receptor kinase inhibitor EW-7197 suppresses cholestatic liver fibrosis by inhibiting HIF1α-induced epithelial mesenchymal transition. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2016;38:571–88. doi: 10.1159/000438651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jin CH, Krishnaiah M, Sreenu D, Subrahmanyam VB, Rao KS, Lee HJ, et al. Discovery of N-((4-([1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyridin-6-yl)-5-(6-methylpyridin-2-yl)-1H-imidazol-2-yl)methyl)-2-fluoroaniline (EW-7197): a highly potent, selective, and orally bioavailable inhibitor of TGF-β type I receptor kinase as cancer immunotherapeutic/antifibrotic agent. J Med Chem. 2014;57:4213–38. doi: 10.1021/jm500115w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim SY, Park S, Lee SW, Lee JH, Lee ES, Kim M, et al. RIPK3 contributes to Lyso-Gb3-induced podocyte death. Cells. 2021;10:245. doi: 10.3390/cells10020245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seok SJ, Lee ES, Kim GT, Hyun M, Lee JH, Chen S, et al. Blockade of CCL2/CCR2 signalling ameliorates diabetic nephropathy in db/db mice. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28:1700–10. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tesch GH, Lim AK. Recent insights into diabetic renal injury from the db/db mouse model of type 2 diabetic nephropathy. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2011;300:F301–10. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00607.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cortes P, Mendez M, Riser BL, Guerin CJ, Rodriguez-Barbero A, Hassett C, et al. F-actin fiber distribution in glomerular cells: structural and functional implications. Kidney Int. 2000;58:2452–61. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Michael AF. The glomerular mesangium. Contrib Nephrol. 1984;40:7–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ravindran S, Pasha M, Agouni A, Munusamy S. Microparticles as potential mediators of high glucose-induced renal cell injury. Biomolecules. 2019;9:348. doi: 10.3390/biom9080348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mima A. Inflammation and oxidative stress in diabetic nephropathy: new insights on its inhibition as new therapeutic targets. J Diabetes Res. 2013;2013:248563. doi: 10.1155/2013/248563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Biernacka A, Dobaczewski M, Frangogiannis NG. TGF-β signaling in fibrosis. Growth Factors. 2011;29:196–202. doi: 10.3109/08977194.2011.595714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosen P, Nawroth PP, King G, Moller W, Tritschler HJ, Packer L. The role of oxidative stress in the onset and progression of diabetes and its complications: a summary of a Congress Series sponsored by UNESCO-MCBN, the American Diabetes Association and the German Diabetes Society. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2001;17:189–212. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith KA, Zhou B, Avdulov S, Benyumov A, Peterson M, Liu Y, et al. Transforming growth factor-β1 induced epithelial mesenchymal transition is blocked by a chemical antagonist of translation factor eIF4E. Sci Rep. 2015;5:18233. doi: 10.1038/srep18233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zeisberg M, Neilson EG. Biomarkers for epithelial-mesenchymal transitions. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1429–37. doi: 10.1172/JCI36183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Balasubramanyam M, Lenin R, Monickaraj F. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in diabetes: new insights of clinical relevance. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2010;25:111–8. doi: 10.1007/s12291-010-0022-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chiang CK, Hsu SP, Wu CT, Huang JW, Cheng HT, Chang YW, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress implicated in the development of renal fibrosis. Mol Med. 2011;17:1295–305. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2011.00131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moon JA, Kim HT, Cho IS, Sheen YY, Kim DK. IN-1130, a novel transforming growth factor-beta type I receptor kinase (ALK5) inhibitor, suppresses renal fibrosis in obstructive nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2006;70:1234–43. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5001775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Park CY, Son JY, Jin CH, Nam JS, Kim DK, Sheen YY. EW-7195, a novel inhibitor of ALK5 kinase inhibits EMT and breast cancer metastasis to lung. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:2642–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sharma K, McCue P, Dunn SR. Diabetic kidney disease in the db/db mouse. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2003;284:F1138–44. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00315.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marques C, Mega C, Goncalves A, Rodrigues-Santos P, Teixeira-Lemos E, Teixeira F, et al. Sitagliptin prevents inflammation and apoptotic cell death in the kidney of type 2 diabetic animals. Mediators Inflamm. 2014;2014:538737. doi: 10.1155/2014/538737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meng XM, Tang PM, Li J, Lan HY. TGF-β/Smad signaling in renal fibrosis. Front Physiol. 2015;6:82. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2015.00082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gill PS, Wilcox CS. NADPH oxidases in the kidney. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:1597–607. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kaspar JW, Niture SK, Jaiswal AK. Nrf2:INrf2 (Keap1) signaling in oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;47:1304–9. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.07.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Katsuoka F, Motohashi H, Ishii T, Aburatani H, Engel JD, Yamamoto M. Genetic evidence that small maf proteins are essential for the activation of antioxidant response element-dependent genes. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:8044–51. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.18.8044-8051.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Michaeloudes C, Chang PJ, Petrou M, Chung KF. Transforming growth factor-β and nuclear factor E2–related factor 2 regulate antioxidant responses in airway smooth muscle cells: role in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:894–903. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201011-1780OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cao Y, Hao Y, Li H, Liu Q, Gao F, Liu W, et al. Role of endoplasmic reticulum stress in apoptosis of differentiated mouse podocytes induced by high glucose. Int J Mol Med. 2014;33:809–16. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2014.1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Madhusudhan T, Wang H, Dong W, Ghosh S, Bock F, Thangapandi VR, et al. Defective podocyte insulin signalling through p85-XBP1 promotes ATF6-dependent maladaptive ER-stress response in diabetic nephropathy. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6496. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]