Abstract

Phenomenon

Medical Student Portfolios (MSP)s allow medical students to reflect and better appreciate their clinical, research and academic experiences which promotes their individual personal and professional development. However, differences in adoption rate, content design and practice setting create significant variability in their employ. With MSPs increasingly used to evaluate professional competencies and the student's professional identity formation (PIF), this has become an area of concern.

Approach

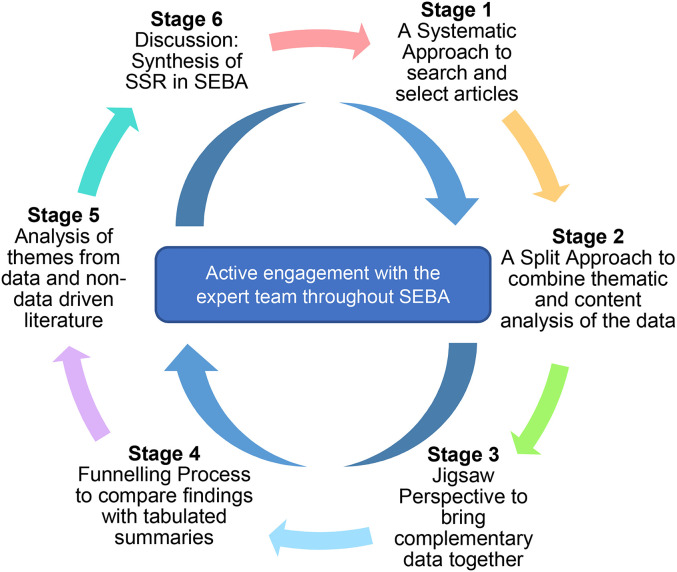

We adopt Krishna’s Systematic Evidence-Based Approach to carry out a Systematic Scoping Review (SSR in SEBA) on MSPs. The structured search process of six databases, concurrent use of thematic and content analysis in the Split Approach and comparisons of the themes and categories with the tabulated summaries of included articles in the Jigsaw Perspective and Funnelling Process offers enhanced transparency and reproducibility to this review.

Findings

The research team retrieved 14501 abstracts, reviewed 779 full-text articles and included 96 articles. Similarities between the themes, categories and tabulated summaries allowed the identification of the following funnelled domains: Purpose of MSPs, Content and structure of MSPs, Strengths and limitations of MSPs, Methods to improve MSPs, and Use of E-portfolios.

Insights

Variability in the employ of MSPs arise as a result of a failure to recognise its different roles and uses. Here we propose additional roles of MSPs, in particular, building on a consistent set of content materials and assessments of milestones called micro-competencies. Whislt generalised micro-competencies assess achievement of general milestones expected of all medical students, personalised micro-competencies record attainment of particular skills, knowledge and attitudes balanced against the medical student’s abilities, context and needs. This combination of micro-competencies in a consistent framework promises a holistic, authentic and longitudinal perspective of the medical student’s development and maturing PIF.

Keywords: medical student portfolio, medical student, portfolio, learning, assessment, reflection, curriculum

Introduction

At a time when medical education is embracing a more personalised approach to knowledge attainment, skills training and development of professional behaviours, portfolios promise a means for medical students to better understand, reflect upon and actively shape their learning and development 1 . Complementing traditional assessment methods with wider longitudinal appraisals of an individual’s growth, portfolios add a personalised dimension to logbooks4,5, by serving as a repository for written examinations, tutor-rating reports and bedside assessments 6 as well as individual reflections and analyses.

Indeed, portfolios offer medical students “a self-regulated, cyclical process in which [they may] mentally revisit their actions, analyse them, cogitate alternatives, [and] try out alternatives in practice” 7 . It is this platform to showcase individual educational, research, ethical, personal and professional development1,8, and guide specific, holistic and timely feedback and remediation throughout the individual’s medical education that underscores growing interest in portfolio use among medical students (henceforth medical student portfolios or MSPs)4,12. However, despite their growing traction 13 , MSPs show significant variability in their structure and content. With local, practical, sociocultural, educational and healthcare considerations prioritising different types of data, the role of MSPs remains limited.

Need for the Review

With MSPs representing a sustainable and effective educational undertaking that provides insight into the medical student’s development, needs, values and beliefs that may guide their professional identity formation (PIF), better understanding of the principles behind their use, the key elements within them and a framework for consistent utilisation is required.

Methods

To determine what is known about MSPs, a systematic scoping review (SSR) is proposed to study current literature to enhance understanding of their roles and structure. These insights will also help guide the design of a consistent framework for MSPs to be used across different settings, purposes and specialities given their ability to evaluate data 14 from “various methodological and epistemological traditions” 19 .

To overcome SSR’s variable methodological steps, guidance and standards, this review adopts the Systematic Evidence Based Approach (SEBA) 20 . A SEBA guided SSR (henceforth SSR in SEBA) facilitates the synthesis of an evidence-based, accountable, transparent, and reproducible analysis and discussion.

Steering this process and boosting accountability, oversight, and transparency, this SSR in SEBA sees an expert team involved in all stages of this review. The expert team comprised of medical librarians, local educational experts, and clinicians.

SSRs in SEBA are built on a constructivist perspective acknowledging the personalised, reflective, and experiential aspect of medical education and recognising the influence of particular clinical, academic, personal, research, professional, ethical, psychosocial, emotional, legal and educational factors upon the medical student’s learning journey, professional development and personal growth 27 .

To operationalise the SSR in SEBA, the research team adopted the principles of interpretivist analysis to enhance reflexivity and discussions18,32 in the six stages outlined in Figure 1 .

Figure 1.

The SEBA process.

(Insert Figure 1. The SEBA Process)

Stage 1 of SEBA: Systematic Approach

1. Determining the title and background of the review

The expert and research teams determined the overall goals of the SSR and the population, context and concept to be evaluated.

2. Identifying the research question

Guided by the PCC (population, concept and context), the expert and research teams agreed upon the research questions. The primary research question was “what is known about medical student portfolios?”. The secondary questions were “what are the components of MSPs?”, “how are MSPs implemented?” and “what are the strengths and weaknesses of MSPs?”.

3. Inclusion criteria

All peer reviewed articles, reviews and grey literature published from first January 2000 to 31st June 2021 were included in the PCC and a PICOS format was adopted to guide the research processes35,36. The PICOS format is found in Table 1 .

Table 1.

PICOS, inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| PICOS | INCLUSION CRITERIA | EXCLUSION CRITERIA |

|---|---|---|

| Population |

|

|

| Intervention |

|

|

| Comparison |

|

|

| Outcome |

|

|

| Study design |

|

4. Searching

A search on six bibliographic databases (PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO, ERIC, Google Scholar and Scopus) was carried out between first to 10th September 2021. Limiting the inclusion criteria was in keeping with Pham et al’s (2014) approach to ensuring a sustainable research process 37 . The search process adopted was structured along the processes set out by systematic reviews.

5. Extracting and charting

Using an abstract screening tool, members of the research team independently reviewed the titles and abstracts identified by each database to identify the final list of articles to be reviewed. Sambunjak et al’s (2010) approach to ‘negotiated consensual validation’ was used to achieve consensus on the final list of articles to be included 38 . The six members of the research team independently reviewed all the articles on the final list, used the Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument (MERSQI) 39 and the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Studies (COREQ) 40 , discussed them online and were in consensus that none should be excluded (Supplementary File 1).

Stage 2 of SEBA: Split Approach

Three teams of researchers simultaneously and independently reviewed the included full-text articles. Here, the combination of independent reviews by the various members of the research teams using two different methods of analysis provided triangulation 41 , while detailing the analytical process improved audits and enhanced the authenticity of the research 42 .

The first team summarised and tabulated the included full-text articles in keeping with recommendations drawn from Wong et al’s (2013) “RAMESES publication standards: meta-narrative reviews” 43 and Popay et al’s (2006) “Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews” 44 . The tabulated summaries served to ensure that key aspects of the included articles were not lost (Supplementary File 1).

Concurrently, the second team of three trained reviewers analysed the included articles using Braun & Clarke’s (2006) approach to thematic analysis 45 . In phase one, the research team carried out independent reviews, actively reading the included articles to find meaning and patterns in the data. In phase two, ‘codes’ were constructed from the ‘surface’ meaning and collated into a code book to code and analyse the rest of the articles using an iterative step-by-step process. As new codes emerged, these were associated with previous codes and concepts. In phase three, the categories were organised into themes that best depict the data. An inductive approach allowed themes to be “defined from the raw data without any predetermined classification”. In phase four, the themes were refined to best represent the whole data set. In phase five, the research team discussed the results of their independent analysis online and at reviewer meetings. ‘Negotiated consensual validation’ was used to determine a final list of themes.

A third team of three trained researchers employed Hsieh & Shannon’s approach to directed content analysis and independently analysed the included articles 46 . This analysis using involved “identifying and operationalising a priori coding categories”. The first stage saw the research team draw categories from Davis et al.’s (2001) “AMEE Medical Education Guide No. 24: Portfolios as a method of student assessment” 47 to guide the coding of the articles. Data not captured by these codes were assigned a new code in keeping with deductive category application. Categories were reviewed and revised as required. In the third stage, they discussed their findings online to achieve consensus on the final codes. These final codes were compared and discussed with the final author.

Stage 3 of SEBA: Jigsaw Perspective

As part of the reiterative process, the themes and categories identified were discussed with the expert team. Here, the themes and categories were viewed as pieces of a jigsaw puzzle and areas of overlap allowed these pieces to be combined to create a wider/holistic view of the overlying data. The combined themes and categories are referred to as themes/categories.

Creating themes/categories relied on use of Phases 4 to 6 of France et al.’s (2016) adaptation 48 of Noblit and Hare's (1998) seven phases of meta-ethnography 52 . To begin, the themes and categories were contextualised by reviewing them against the primary codes and subcategories and/or subthemes they were drawn from. Reciprocal translation was used to determine if the themes and categories could be used interchangeably.

Stage 4 of SEBA: Funnelling Process

To provide structure to the Funnelling Process, we employed Phases 3 to 5 of the adaptation. We described the nature, main findings, and conclusions of the articles. These descriptions were compared with the tabulated summaries. Adapting Phase 5, reciprocal translation was used to juxtapose the themes/categories identified in the Jigsaw Perspective with the key messages identified in the summaries. These verified themes/categories then form the line of argument in the discussion synthesis.

Results

A total of 14501 abstracts were reviewed, 779 full text articles were evaluated, and 96 articles were included (see Figure 2 .). The funnelled domains identified were: Purpose of MSPs, Content and structure of MSPs, Strengths and limitations of MSPs, Methods to improve MSPs, and Use of E-portfolios.

Figure 2.

PRISMA flow chart.

Funnelled Domain 1: Purpose of MSPs

The purpose behind the employ of MSPs are often poorly explained and have been summarised in Table 2 for ease of review.

Table 2.

Purpose of MSPs.

| CONTENT | ELABORATION AND/OR EXAMPLES |

|---|---|

| Learning | |

| Assessment |

|

Funnelled Domain 2: Content and structure of MSPs

1. Content in MSPs

Similarly, discussions on the contents of MSPs are limited and have been summarised in Table 3. The content can be broadly categorised into content provided by the institution, medical students, and feedback/assessments by other stakeholders.

Table 3.

Content in MSPs.

| CONTENT | ELABORATION AND/OR EXAMPLES |

|---|---|

| Contributed by institution | |

| Learning objectives |

|

| Educational Resources | |

| Reflective prompts | |

| Contributed by medical student | |

| Evidence of Activities |

|

| Evidence of reflection | |

| Evidence of self-assessment | |

| Contributed by other stakeholders (eg assessors, peers) | |

| Assessments |

|

2. Structure of MSPs

Standardisation within and across portfolios may be achieved through the use of a clear template 4 or set of guidelines 53 . MSPs with clear delineation of contents required 54 were found to boost student receptivity55,56 and enhanced reliability and validity during portfolio assessment47,55,57.

However, a flexible approach allowing medical students to personalise their MSPs 58 and express themselves more freely 59 facilitates portfolio student-centricity60,61 and ownership 53 . By encouraging students to incorporate their own content, such as reflective diary entries 55 , reflective essays 57 , video recordings 58 , audio recordings 59 , poetry or art 62 , improvements may be seen in the quantity and quality of their reflections 56 .

Funnelled Domain 3: Strengths and Limitations of MSPs

Given the lack of elaboration, much of the data for this domain is summarised in tables to aid easy review.

1. Strengths

Strengths of MSPs are highlighted in Table 4 .

Table 4.

Strengths of MSPs.

2. Limitations

The limitations of MSPs are highlighted in Table 5 .

Table 5.

Limitations of MSPs.

| LIMITATIONS | ELABORATION AND/OR EXAMPLES |

|---|---|

| Learning | |

| Assessment |

|

| Portfolio Implementation |

|

Funnelled Domain 4: Methods to Improve MSPs

The potential methods to improve MSPs are highlighted in Table 6 .

Table 6.

Methods to improve MSPs.

| METHODS | ELABORATION AND/OR EXAMPLES |

|---|---|

|

Increase

Mentorship Mentorship refers to a system where students are assigned to faculty throughout their training and portfolio creation to coach them54,57,101, engage them in supportive dialogue63,64,108,118,148, provide feedback1,61,63,64,133 and encourage them to fully engage with their portfolios74,78,103,131,146. | |

| Benefits of Mentorship | |

| Improving quality of mentorship | |

| Having a structured mentoring programme to guide portfolio use | |

| Encourage portfolio uptake | |

| Improve understanding |

|

| Increase Exposure |

|

| Structure portfolio appropriately | |

| Organise portfolio based on its purpose |

|

| Improving portfolio assessment process | |

| Enhance learning through assessment process | |

| Standardisation | |

| Improve assessment procedure |

|

| Improve self-assessment process |

|

| Evaluate Feedback | |

| Importance | |

Funnelled Domain 5: E-Portfolio

The electronic portfolio (e-portfolio) is a form of MSP that is hosted on electronic platforms5,6,9,47,53,56,58,61,63, and may be created using unique software47,63,65,76,86. Compared to hardcopy portfolios, they are more durable 66 , user friendly63,75,77, accessible6,53,58,61,80 collaborative5,67,73,76,81 and superior for assessment in certain areas 61 . Furthermore, they are able to include a wider variety of evidence including videos or website links5,63,75,78,79, provide increased privacy and confidentiality for users including students and coaches67,73,86 and allow for instant comparison between students 76 . These factors enhance their receptivity among medical students53,61,63.

However, accessibility may be limited by poor interface design64,67,73,74,77,87,88, limited administrative support67,73,88, poor technology66,67,73,79, and a lack of time or finances to upgrade and support e-portfolio technology 67 . Similarly, the lack of immediate access to computers in a clinical setting58,66,73, poor data security58,65,66, issues with communicating with mentors online 64 or mentors not being tech-savvy 67 also limit their applicability.

Stage 5 of SEBA: Analysis of Evidence-Based and Non-Data Driven Literature

Evidence-based data from bibliographic databases were separated from grey literature such as opinion pieces, perspectives, editorial, letters and non-data based articles drawn from bibliographic databases and both groups were thematically analysed separately. The themes from both groups were compared to determine if there were additional themes in the non-data driven sources that could influence the narrative. In this review, the themes from the two data sources overlap, suggesting no undue influence upon the findings of this review.

Stage 6 of SEBA: Synthesis of SSR in SEBA

The narrative produced from consolidation of the funnelled domains was guided by the Best Evidence Medical Education (BEME) Collaboration guide 89 and the STORIES (Structured approach to the Reporting In healthcare education of Evidence Synthesis) statement 90 .

Discussion

In answering its primary and secondary research questions, this SSR in SEBA reveals that MSPs have expanded beyond merely repositories of assessments and are now seen as a means of triangulating and contextualising assessments and their impact upon individual medical students. MSPs also allow students, faculty, and institutions to better understand the medical student’s needs, abilities, expectations, and aspirations, aiding the provision of personalised mentoring and remediation. However, to meet these wider roles, manageable 87 and “authentic” portfolios that improve levels of engagement 91 are key. Here, authenticity refers to the “extent to which the outcomes measured represent appropriate, meaningful, significant and worthwhile forms of human accomplishments” 47 and serves to enhance the trustworthiness of what is largely qualitative data, and the validity of longitudinal assessments that help to map the development of their clinical competency 4 and professional identity formation4,12,92.

However, current MSPs lack a consistent structure. While broad commonalities including learning objectives and professional expectations and roles to be met, and reflections, learning activities, self-assessments, achievements, and other evidence of competencies, MSPs vary significantly in their focus and content. Yet, these variations and particularities are unsurprising given the different practice settings, structure and program goals established by the host institution. These differences underpin the presence of different types, “depth” and nature of content prioritised. Inherent variability brought about by personalisation of longitudinal data, “choice of materials by the student” 54 and “individualised selection of evidence” 47 , ultimately limits the use of portfolios beyond the confines of a specific institution. This lack of consistency raises concerns about the efficacy of MSPs in providing a holistic perspective of the medical student’s personal, academic, clinical, and professional development.

We believe that these concerns may be bridged in part by harnessing the ability of current MSPs to capture education and assessment in specific areas of practice. Our findings suggest that current MSPs encapsulate several entrustable professional activities (EPA)s 94 . Each EPA however shares common aspects of other EPAs that may not be directly contained within a particular MSP. We believe that it is possible to harness these overlapping aspects to make MSPs more widely applicable. Here, we build upon the notion that micro-credentialling that incorporates “circumscribed assessments” of a specific EPA, such as “interpreting and communicating results of common diagnostic and screening tests”, may be extrapolated to other EPAs such as “[communicating] in difficult situations” in a different practice setting 97 .

Hong et al’s (2021) and Zhou et al’s (2021) adaptations98,99 of Norcini’s (2020) concept of micro-credentialling and micro-certification in medical education 100 which forward the concepts of generalised and personalised micro-competencies provide a viable bridge between prevailing MSP content without compromising the rich mix of structure and customisation within MSPs. Based on the certification of micro-competencies within an EPA, Zhou et al. (2021) suggest that generalised micro-competencies are the standards and expectations applicable to all medical students. They are small, professional learning milestones that all students need to attain before proceeding to the next competency-based stage. These are requisite knowledge, skills and attitudes all soon-to-be clinicians must have. Personalised micro-competencies, in turn, are determined by the individual’s particular goals, training, abilities, skills and experiences. They are determined by the medical student and tutors and must be consistent with institutional codes of conduct and expectations. They underscore the importance of assessing the student's individual needs and circumstances which influence which in turn shape the kind of training and support proffered. With expectations differing across practice settings and levels of training, both generalised andpersonalised micro-competencies must be clearly conveyed to the medical student and tutors in a timelyand structured manner. To encapture their learning and attainment, MSPs must forward clear learning plans to align expectations with evidence of diverse learning activities, reflective prompts and diaries, multisource formative and summative evaluations via standardised assessment tools and constructive feedback. These standardised baseline guidelines will lend clarity to portfolio developers and users. This may boost the latter’s trust and receptivity towards regular portfolio use55,56.

We believe that structured and consistent micro-certification of micro-competencies could be extrapolated beyond the initial goals of the MSPs and could provide a longitudinal perspective of the medical student’s development. This is especially useful when considering competencies such as interpersonal, communication skills and systems-based practices. Perhaps here, too, the silver lining to changes in medical education practices due to the COVID-19 pandemic can be harnessed.

With many institutions incorporating online learning, e-portfolios should be institutionally sanctioned 85 with a dedicated team of portfolio developers and invested faculty members onboarding and overseeing their implementation. These considerations foreground the need for orientation sessions10,62,64,67,104 to educate students and faculty on the identified EPAs as well as the use of generalised and personalised micro-competencies to ensure learning and assessment congruity and objectivity91,105,106. Embedding the portfolios into the formal curricula, assigning students mentors trained in reflective engagement, and establishing protected time for regular portfolio reviews would help to facilitate their consistent usage. Concurrently, portfolio use must be part of a continuous quality improvement process, building on feedback 107 and lessons learnt to promote further improvement to MSPs and portfolio assessment10,11,47,62,78. Indeed, both forms of micro-competencies underline the need for effective recording and oversight. This is especially important when micro-competencies provide a holistic appraisal of the medical student’s progress and achievements, needs and abilities and provides insights into their professional identity formation. Capturing this data in a comprehensive, longitudinal manner replete with the medical student’s reflections reveals a new dimension to portfolio use.

Limitations

Firstly, the review is limited by the omission of articles not published in English. This creates the risk of missing key papers. Furthermore, the focus on papers published in English led to focus on studies in North America and Europe.

Secondly, while the articles comment on the sentiment of users including medical students on the effectiveness of portfolios for learning and assessment, there are a limited number of articles highlighting the perspectives of doctors who previously undertook the task of undergraduate portfolios. Hence, the review is limited by its inability to assess the long-term effectiveness and acceptability of portfolio usage after medical students enter the workforce as practicing medical professionals.

Conclusion

This SSR in SEBA reveals that if portfolios are to remain relevant and maintain their user-friendliness and accessibility, the future of MSPs must lie in improving assessments and in enhancing the manner in which they are designed.

While it is clear that assessments tools need to be enhanced to meet new perspectives of education and training, it is perhaps timely that this SSR in SEBA suggests key changes to portfolio use. In adopting e-portfolios for its accessible and expansive potential, it is clear that a robust and well-supported platform is critical. This platform ought to accommodate all manner of data and assessment results and remain a comprehensive repository of data. Categorised into different, sometimes overlapping, domains, data from this repository may be drawn to populate different designs of MSPs. Changing from one goal to another should therefore be simple. Such flexibility will still allow medical students to personalise their e-portfolios in a manner that they feel best represents their development without compromising faculty evaluation. A flexible yet robust e-portfolio such as this will also enable collaborations and facilitate input of corroborative data from third parties where required.

Moving forward, further research may be undertaken to identify the long-term effects of portfolio usage, the manner that portfolios are evaluated, and the impact it has on professional identity formation throughout and beyond medical school.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to dedicate this paper to the late Dr S Radha Krishna whose advice and ideas were integral to the success of this study.

Glossary Terms

- Professional Identity Formation

An adaptive developmental process that involves the psychological development of an individual, and the socialisation of the individual into appropriate roles and participation at work.

- Krishna’s Systematic Evidence-Based Approach (SEBA )

A structured and accountable approach used to guide analyses to ensure reproducible and robust data.

- Split Approach

Combines content and thematic analysis of data to enhance the trustworthiness and depth of an analysis.

- Jigsaw Perspective

Comparing overlaps between the themes and categories delineated by content and thematic analysis are considered in tandem, like complementary ‘pieces of the jigsaw’. This allows for holistic perspective of data.

List of abbreviations

- EPA

Entrustable Professional Activities

- MSP

Medical Student Portfolios

- PCC

Population, concept and context

- SEBA

Systematic Evidence-Based Approach

- SSR

Systematic Scoping Review

Biography

Ms Rei Tan is a medical student at the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore. Email: e0232945@u.nus.edu

Ms Jacquelin Jia Qi Ting is a medical student at the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore. Email: jacting@gmail.com

Mr Daniel Zhihao Hong is a medical student at the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore. Email: hongzhihao@live.com

Ms Annabelle Jia Sing Lim is a medical student at the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore. Email: annabellelimjs@gmail.com

Ms Yun Ting Ong is a medical student at the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore. Email: yunting.ong08@gmail.com

Ms Anushka Pisupati is a medical student at the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore. Email: anushka.pisupati@u.nus.edu

Ms Eleanor Jia Xin Chong is a medical student at the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore. Email: eleanor.chong@u.nus.edu

Ms Min Chiam, MSc (Medical Humanities) is a researcher at the Division of Cancer Education, National Cancer Centre Singapore, Singapore. Email: chiam.min@nccs.com.sg

Ms Alexia Sze Inn Lee, BSc (Psychological Science) works at the Division of Cancer Education, National Cancer Centre Singapore, Singapore. Email: "lee.sze.inn@nccs.com.sg

Dr Laura Hui Shuen Tan, MBBS graduated from the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore. Email: laura.tan.hs@gmail.com

Ms Annelissa Mien Chew Chin, MSc (Info & Lit) is a Senior Librarian at the Medical library, National University of Singapore libraries, Singapore. Email: annelissa_chin@nus.edu.sg

Dr Limin Wijaya MBBS (Melbourne), MRCP (UK), DTM&H (Liverpool), is a senior consultant at the Division of Infectious Disease, Singapore General Hospital, Singapore. Email: limin.wijaya@singhealth.com.sg

Dr Warren Fong MBBS, MRCP, FAMS, is a doctor at the Department of Rheumatology and Immunology, Singapore General Hospital, Singapore. Email: warren.fong.w.s@singhealth.com

Prof Lalit Kumar Radha Krishna MBChB, FRCP, FAMS, MA (Medical Education), MA (Medical Ethics), PhD (Medical Ethics) is a Senior Consultant at the Division of Supportive and Palliative Care at the National Cancer Centre Singapore, Singapore. Prof LKRK holds faculty appointments with the Centre for BioMedical Ethics, Duke-NUS Medical School and the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore. Email: lalit.radha-krishna@liverpool.ac.uk

Footnotes

Declarations: Ethics approval and consent to participate Not applicable

Consent for publication Not applicable

Availability of data and materials All data generated or analysed during this review are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Competing interests All authors have no competing interests.

FUNDING: No funding was received for this review

Authors’ contributions: All authors were involved in data curation, formal analysis and investigation, preparing the original draft of the manuscript as well as reviewing and editing the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Ethical Approval: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Informed Consent: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Trial Registration: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any clinical trials.

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Davis MH, Friedman Ben-David M, Harden RM, et al. Portfolio assessment in medical students’ final examinations. Med Teach. 2001;23(4):357‐366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fida NM, Shamim MS. Portfolios in Saudi medical colleges. Why and how? Saudi Med J. 2016;37(3):245‐248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Santonja-Medina F, Garcia-Sanz MP, Martinez-Martinez F, Bo D, Garcia-Estan J. Portfolio as a tool to evaluate clinical competences of traumatology in medical students. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2016;7:57‐61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Driessen EW, Overeem K, van Tartwijk J, van der Vleuten CP, Muijtjens AM. Validity of portfolio assessment: which qualities determine ratings? Med Educ. 2006;40(9):862‐866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sánchez Gómez S, Ostos EM, Solano JM, Salado TF. An electronic portfolio for quantitative assessment of surgical skills in undergraduate medical education. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13(65). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duque G, Finkelstein A, Roberts A, Tabatabai D, Gold SL, Winer LR. Learning while evaluating: the use of an electronic evaluation portfolio in a geriatric medicine clerkship. BMC Med Educ. 2006;6(4):4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fida NM, Hassanien M, Shamim MS, et al. Students’ perception of portfolio as a learning tool at king abdulaziz university medical school. Med Teach. 2018;40(sup1):S104‐s113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burch VC, Seggie JL. Use of a structured interview to assess portfolio-based learning. Med Educ. 2008;42(9):894‐900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiu YT, Lee KL, Ho MJ. Effects of feedback from near-peers and non-medical professionals on portfolio use. Med Educ. 2014;48(5):539‐540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dannefer EF, Henson LC. The portfolio approach to competency-based assessment at the Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine. Acad Med. 2007;82(5):493‐502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elango S, Jutti RC, Lee LK. Portfolio as a learning tool: students’ perspective. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2005;34(8):511‐514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greenberg L, Blatt B. Perspective: successfully negotiating the clerkship years of medical school: a guide for medical students, implications for residents and faculty. Acad Med. 2010;85(4):706‐709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burch VC, Seggie J. Portfolio assessment using a structured interview. Med Educ. 2005;39(11):1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ruiz-Perez I, Petrova D. Scoping reviews. Another way of literature review. Med Clin (Barc). 2019;153(4):165‐168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19‐32. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Armstrong R, Hall BJ, Doyle J, Waters E. Cochrane update. 'Scoping the scope' of a cochrane review. J Public Health (Oxf). 2011;33[1]:147‐150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schick-Makaroff K, MacDonald M, Plummer M, Burgess J, Neander W. What synthesis methodology should I Use? A review and analysis of approaches to research synthesis. AIMS Public Health. 2016;3(1):172‐215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomas A, Lubarsky S, Varpio L, Durning SJ, Young ME. Scoping reviews in health professions education: challenges, considerations and lessons learned about epistemology and methodology. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2020;25(4):989‐1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kow CS, Teo YH, Teo YN, et al. A systematic scoping review of ethical issues in mentoring in medical schools. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):1‐10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bok C, Ng CH, Koh JWH, et al. Interprofessional communication (IPC) for medical students: a scoping review. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ngiam LXL, Ong YT, Ng JX, et al. Impact of caring for terminally Ill children on physicians: a systematic scoping review. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2020;38(4):396–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krishna LKR, Tan LHE, Ong YT, et al. Enhancing mentoring in palliative care: an evidence based mentoring framework. Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development. 2020;7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kamal NHA, Tan LHE, Wong RSM, et al. Enhancing education in palliative medicine: the role of systematic scoping reviews. Palliative Medicine & Care: Open Access. 2020;7(1):1‐11. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ong RRS, Seow REW, Wong RSM, et al. A systematic scoping review of narrative reviews in palliative medicine education. Palliative Medicine & Care: Open Access. 2020;7(1):1‐22. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mah ZH, Wong RSM, Seow REW, et al. A systematic scoping review of systematic reviews in palliative medicine education. Palliative Medicine & Care: Open Access. 2020;7(1):1‐12. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guba EG, Lincoln YS. Competing paradigms in qualitative research. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS. eds. Handbook of qualitative research. Sage Publications; 1994:105‐117. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scotland J. Exploring the philosophical underpinnings of research: relating ontology and epistemology to the methodology and methods of the scientific, interpretive, and critical research paradigms. English Language Teaching. 2012;5(9):9‐16. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thomas A, Menon A, Boruff J, Rodriguez AM, Ahmed S. Applications of social constructivist learning theories in knowledge translation for healthcare professionals: a scoping review. Implement Sci. 2014;9(1):54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Radha Krishna LK, Renganathan Y, Tay KT, et al. Educational roles as a continuum of mentoring’s role in medicine – a systematic review and thematic analysis of educational studies from 2000 to 2018. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mack L. The philosophical underpinnings of educational research. Polyglossia. 2010;19:5–11. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pring R. The ‘false dualism’of educational research. Journal of Philosophy of Education. 2000;34(2):247‐260. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Crotty M. The Foundations of Social Research: Meaning and Perspective in the Research Process. Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ford K. Taking a narrative turn: possibilities, challenges and potential outcomes. OnCUE Journal. 2012;6(1):23–36. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peters M, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Soares C, Khalil H, Parker D. The Joanna Briggs Institute reviewers’ manual 2015: methodology for JBI scoping reviews. 2015. http://joannabriggs.org/assets/docs/sumari/Reviewers-Manual_Methodology-for-JBI-Scoping-Reviews_2015_v1.pdf

- 36.Peters MD, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):141‐146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pham MA-O, Rajić A, Greig JD, Sargeant JM, Papadopoulos A, McEwen SA. A scoping review of scoping reviews: advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. 2014(1759-2887 [Electronic]). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Sambunjak D, Straus SE, Marusic A. A systematic review of qualitative research on the meaning and characteristics of mentoring in academic medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(1):72‐78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reed DA, Beckman TJ, Wright SM, Levine RB, Kern DE, Cook DA. Predictive validity evidence for medical education research study quality instrument scores: quality of submissions to JGIM’s medical education special issue. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(7):903‐907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349‐357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tavakol M, Sandars J. Quantitative and qualitative methods in medical education research: AMEE guide No 90: part I. Med Teach. 2014;36(9):746‐756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cleland J, Durning SJ. Researching medical education. John Wiley & Sons; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Westhorp G, Buckingham J, Pawson R. RAMESES Publication standards: meta-narrative reviews. BMC Med. 2013;11(1):20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A product from the ESRC methods programme Version. 2006;1:b92. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77‐101. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277‐1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Friedman Ben David M, Davis MH, Harden RM, Howie PW, Ker J, Pippard MJ. AMEE Medical education guide No. 24: portfolios as a method of student assessment. Med Teach. 2001;23(6):535‐551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.France EF, Wells M, Lang H, Williams B. Why, when and how to update a meta-ethnography qualitative synthesis. Syst Rev. 2016;5:44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.France EF, Uny I, Ring N, et al. A methodological systematic review of meta-ethnography conduct to articulate the complex analytical phases. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2019;19(1):35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.France EF, Wells M, Lang H, Williams B. Why, when and how to update a meta-ethnography qualitative synthesis. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):1‐12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.France EF, Uny I, Ring N, et al. A methodological systematic review of meta-ethnography conduct to articulate the complex analytical phases. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2019;19(1):1‐18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Noblit GW, Hare RD, Hare RD. Meta-ethnography: Synthesizing qualitative studies. Sage; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Franco RS, dos Santos Franco CAG, Pestana O, Severo M, Ferreira MA. The use of portfolios to foster professionalism: attributes, outcomes, and recommendations. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education. 2017;42(5):737‐755. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Driessen E, van Tartwijk J, Vermunt JD, van der Vleuten CP. Use of portfolios in early undergraduate medical training. Med Teach. 2003;25(1):18‐23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rees CE, Shepherd M, Chamberlain S. The utility of reflective portfolios as a method of assessing first year medical students’ personal and professional development. Reflective Practice. 2005;6(1):3‐14. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Franco R, Ament Giuliani Franco C, de Carvalho Filho MA, Severo M, Amelia Ferreira M. Use of portfolios in teaching communication skills and professionalism for Portuguese-speaking medical students. Int J Med Educ. 2020;11:37‐46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Driessen EW, van Tartwijk J, Overeem K, Vermunt JD, van der Vleuten CP. Conditions for successful reflective use of portfolios in undergraduate medical education. Med Educ. 2005;39(12):1230‐1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Avila J, Sostmann K, Breckwoldt J, Peters H. Evaluation of the free, open source software WordPress as electronic portfolio system in undergraduate medical education. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16:157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Oudkerk Pool A, Jaarsma ADC, Driessen EW, Govaerts MJB. Student perspectives on competency-based portfolios: does a portfolio reflect their competence development? Perspectives on medical education. 2020;9(3):166‐172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gordon J. Assessing students’ personal and professional development using portfolios and interviews. Med Educ. 2003;37(4):335‐340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chae SJ, Lee YW. Exploring the strategies for successfully building e-portfolios in medical schools. Korean J Med Educ. 2021;33(2):133‐137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yielder J, Moir F. Assessing the development of medical Students’ personal and professional skills by portfolio. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2016;3:JMECD.S30110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.O'Sullivan AJ, Harris P, Hughes CS, et al. Linking assessment to undergraduate student capabilities through portfolio examination. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education. 2012;37(3):379‐391. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Arntfield S, Parlett B, Meston CN, Apramian T, Lingard L. A model of engagement in reflective writing-based portfolios: interactions between points of vulnerability and acts of adaptability. Med Teach. 2016;38(2):196‐205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bashook P, Gelula M, Joshi M, Sandlow L. Impact of student reflective e-portfolio on medical student advisors. Teach Learn Med. 2008;20(1):26‐30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Belcher R, Jones A, Smith LJ, et al. Qualitative study of the impact of an authentic electronic portfolio in undergraduate medical education. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14(265). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chertoff J, Wright A, Novak M, et al. Status of portfolios in undergraduate medical education in the LCME accredited US medical school Status of portfolios in undergraduate medical education in the LCME accredited US medical school. Med Teach. 2016;38(9):886‐896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cotterill S, McDonald T, Horner P. Using the ePET portfolio to support teaching and learning in Medicine: Lessons from 3 Institutions. 2008.https://s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/assets.creode.advancehe-document-manager/documents/hea/private/using_the_epet_portfolio_1568036930.pdf

- 69.Cunningham H, Taylor D, Desai UA, et al. Looking back to move forward: first-year medical Students’ meta-reflections on their narrative portfolio writings. Acad Med. 2018;93(6):888‐894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dannefer EF, Bierer SB, Gladding SP. Evidence within a portfolio-based assessment program: what do medical students select to document their performance? Med Teach. 2012;34(3):215‐220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dannefer EF, Prayson RA. Supporting students in self-regulation: use of formative feedback and portfolios in a problem-based learning setting. Med Teach. 2013;35(8):655‐660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dornan T, Maredia N, Hosie L, Lee C, Stopford A. A web-based presentation of an undergraduate clinical skills curriculum. Med Educ. 2003;37(6):500‐508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Moores A, Parks M. Twelve tips for introducing E-portfolios with undergraduate students. Med Teach. 2010;32(1):46‐49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Vance GHS, Burford B, Shapiro E, Price R. Longitudinal evaluation of a pilot e-portfolio-based supervision programme for final year medical students: views of students, supervisors and new graduates. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Babovic M, Fu RH, Monrouxe LV. Understanding how to enhance efficacy and effectiveness of feedback via e-portfolio: a realist synthesis protocol. BMJ Open. 2019;9(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Carney PA, Mejicano GC, Bumsted T, Quirk M. Assessing learning in the adaptive curriculum. Med Teach. 2018;40(8):813‐819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chu A, Biancarelli D, Drainoni ML, et al. Usability of learning moment: features of an E-learning tool that maximize adoption by students. West J Emerg Med. 2019;21(1):78‐84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Désilets V, Graillon A, Ouellet K, Xhignesse M, St-Onge C. Reflecting on professional identity in undergraduate medical education: implementation of a novel longitudinal course. Perspectives on medical education. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Heeneman S, Driessen E, Durning SJ, Torre D. Use of an e-portfolio mapping tool: connecting experiences, analysis and action by learners. Perspect Med Educ. 2019;8(3):197‐200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kanfi A, Faykus MW, Tobler J, Dallaghan GLB, England E, Jordan SG. The early bird gets the work: maintaining a longitudinal learner portfolio From medical school to physician practice. Acad Radiol. 2021;S1076-6332(20)30705-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mejicano GC, Bumsted TN. Describing the journey and lessons learned implementing a competency-based, time-Variable undergraduate medical education curriculum. Acad Med. 2018;93(3S Competency-Based, Time-Variable Education in the Health Professions):S42‐S48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Roskvist R, Eggleton K, Goodyear-Smith F. Provision of e-learning programmes to replace undergraduate medical students’ clinical general practice attachments during COVID-19 stand-down. Education for primary care : an official publication of the Association of Course Organisers, National Association of GP Tutors, World Organisation of Family Doctors. 2020;31(4):247‐254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Santonja-Medina F, García-Sanz MP, Santonja-Renedo S, García-Estañ J. Mismatch between student and tutor evaluation of training needs: a study of traumatology rotations. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11(1):826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sohrmann M, Berendonk C, Nendaz M, Bonvin R. Swiss Working group For profiles I. Nationwide introduction of a new competency framework for undergraduate medical curricula: a collaborative approach. Swiss Med Wkly. 2020;150:w20201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ten Cate O, Graafmans L, Posthumus I, Welink L, van Dijk M. The EPA-based Utrecht undergraduate clinical curriculum: development and implementation. Med Teach. 2018;40(5):506‐513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Byszewski A, Fraser A, Lochnan H. East meets west: shadow coaching to support online reflective practice. Perspect Med Educ. 2018;7(6):412‐416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.O'Sullivan AJ, Howe AC, Miles S, et al. Does a summative portfolio foster the development of capabilities such as reflective practice and understanding ethics? An evaluation from two medical schools. Med Teach. 2012;34(1):e21‐e28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mason G, Langendyk V, Wang S. “The game is in the tutorial”: an evaluation of the use of an e-portfolio for personal and professional development in a medical school. 2014.https://ascilite2014.otago.ac.nz/files/fullpapers/43-Mason.pdf

- 89.Haig A, Dozier M. BEME Guide no 3: systematic searching for evidence in medical education--part 1: sources of information. Med Teach. 2003;25(4):352‐363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gordon M, Gibbs T. STORIES Statement: publication standards for healthcare education evidence synthesis. BMC Med. 2014;12(1):143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Davis MH, Ponnamperuma GG, Ker JS. Student perceptions of a portfolio assessment process. Med Educ. 2009;43(1):89‐98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ho CY, Kow CS, Chia CHJ, et al. The impact of death and dying on the personhood of medical students: a systematic scoping review. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kuek JTY, Ngiam LXL, Kamal NHA, et al. The impact of caring for dying patients in intensive care units on a physician's personhood: a systematic scoping review. Philos Ethics Humanit Med. 2020;15(1):12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ten Cate O, Taylor DR. The recommended description of an entrustable professional activity: AMEE Guide No. 140. Med Teach. 2021;43(10):1106–1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ten Cate O. AM Last page: what entrustable professional activities add to a competency- based curriculum. Acad Med. 2014;89(4):691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Carraccio C, Englander R, Gilhooly J, et al. Building a framework of entrustable professional activities, supported by competencies and milestones, to bridge the educational Continuum. Acad Med. 2017;92(3):324‐330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Pinilla S, Lenouvel E, Cantisani A. Working with entrustable professional activities in clinical education in undergraduate medical education: a scoping review. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(172). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hong DZ, Lim AJS, Tan R, et al. A systematic scoping review on portfolios of medical educators. Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Zhou YC, Tan SR, Tan CGH, et al. A systematic scoping review of approaches to teaching and assessing empathy in medicine. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(292). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Norcini J. Is it time for a new model of education in the health professions? Med Educ. 2020;54(8):687‐690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Beck Dallaghan GL, Coplit L, Cutrer WB, Crow S. Medical student portfolios: their value and what You need for successful implementation. Acad Med. 2020;95(9):1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Datta R, Datta K, Routh D, et al. Development of a portfolio framework for implementation of an outcomes-based healthcare professional education curriculum using a modified e-delphi method. Medical Journal Armed Forces India. 2021;77:S49‐S56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Cunningham H, Taylor DS, Desai UA, et al. Reading the self: medical Students’ experience of reflecting on their writing over time. Acad Med. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ross S, Maclachlan A, Cleland J. Students’ attitudes towards the introduction of a personal and professional development portfolio: potential barriers and facilitators. BMC Med Educ. 2009;9(69). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Bierer SB, Dannefer E. Does Students’ gender, citizenship, or verbal ability affect fairness of portfolio-based promotion decisions? Results From One medical school. Acad Med. 2011;86(6):773‐777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Rees C, Sheard C. Undergraduate medical students’ views about a reflective portfolio assessment of their communication skills learning. Med Educ. 2004;38(2):125‐128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hall P, Byszewski A, Sutherland S, Stodel EJ. Developing a sustainable electronic portfolio (ePortfolio) program that fosters reflective practice and incorporates CanMEDS competencies into the undergraduate medical curriculum. Acad Med. 2012;87(6):744‐751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Ekayanti F, Risahmawati R, Fadhilah M. Portfolio Assessment Implementation in Clinical Year of Community Medicine Module: Students’ Perspective. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2017;10:44–48. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Sheng AY, Chu A, Biancarelli D, Drainoni ML, Sullivan R, Schneider JI. A novel Web-based experiential learning platform for medical students (learning moment): qualitative study. JMIR Med Educ. 2018;4(2):e10657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.van Schaik S, Plant J, O'Sullivan P. Promoting self-directed learning through portfolios in undergraduate medical education: the mentors’ perspective. Med Teach. 2013;35(2):139‐144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.O'Brien CL, Sanguino SM, Thomas JX, Green MM. Feasibility and outcomes of implementing a portfolio assessment system alongside a traditional grading system. Acad Med. 2016;91(11):1554‐1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Michels NR, Driessen EW, Muijtjens AM, Van Gaal LF, Bossaert LL, De Winter BY. Portfolio assessment during medical internships: how to obtain a reliable and feasible assessment procedure. Educ Health (Abingdon). 2009;22[3]:313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Borgstrom E, Cohn S, Barclay S. Medical professionalism: conflicting values for tomorrow's doctors. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(12):1330‐1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Chaffey LJ, de Leeuw EJ, Finnigan GA. Facilitating students’ reflective practice in a medical course: literature review. Educ Health (Abingdon). 2012;25[3]:198‐203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Deketelaere A, Kelchtermans G, Druine N, Vandermeersch E, Struyf E, De Leyn P. Making more of it! medical students’ motives for voluntarily keeping an extended portfolio. Med Teach. 2007;29(8):798‐805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Haffling AC, Beckman A, Pahlmblad A, Edgren G. Students’ reflections in a portfolio pilot: highlighting professional issues. Med Teach. 2010;32(12):e532‐e540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Rees CE, Sheard CE. The reliability of assessment criteria for undergraduate medical students’ communication skills portfolios: the nottingham experience. Med Educ. 2004;38(2):138‐144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Cherfi Y, Szántó K. Student portfolios: not just a tick-box exercise. Clin Teach. 2019;16(6):641‐642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Forenc KM, Eriksson FM, Malhotra B. Medical Students’ perspectives on an assessment of reflective portfolios. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2020;11:463‐464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Imafuku R, Saiki T, Hayakawa K, Sakashita K, Suzuki Y. Rewarding journeys: exploring medical students’ learning experiences in international electives. Med Educ Online. 2021;26(1):1913784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Kassab SE, Bidmos M, Nomikos M, et al. Construct validity of an instrument for assessment of reflective writing-based portfolios of medical students. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2020;11:397‐404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Kim JW, Ryu H, Park JB, et al. Establishing a patient-centered longitudinal integrated clerkship: early results from a single institution. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35(50):e419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Yoo DM, Cho AR, Kim S. Evaluation of a portfolio-based course on self-development for pre-medical students in korea. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2019;16:38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Yoo DM, Cho AR, Kim S. Development and validation of a portfolio assessment system for medical schools in korea. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2020;17:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Van Tartwijk J, Driessen EW. Portfolios for assessment and learning: AMEE. Guide no. 45. Med Teach. 2009;31(9):790‐801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Sahu SK, Soudarssanane M, Roy G, Premrajan K, Sarkar S. Use of portfolio-based learning and assessment in community-based field curriculum. Indian J Community Med. 2008;33(2):81‐84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Prayson RA, Bierer SB, Dannefer EF. Medical student resilience strategies: a content analysis of medical students’ portfolios. Perspect Med Educ. 2017;6(1):29‐35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Özçakar N, Mevsim V, Güldal D. Use of portfolios in undergraduate medical training: first meeting With a patient. Balkan Med J. 2009;26(2):145‐150. [Google Scholar]

- 129.Austin C, Braidman I. Support for portfolio in the initial years of the undergraduate medical school curriculum: what do the tutors think? Med Teach. 2008;30(3):265‐271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.King TS, Sharma R, Jackson J, Fiebelkorn KR. Clinical case-based image portfolios in medical histopathology. Anat Sci Educ. 2019;12(2):200‐209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Michels NR, Avonts M, Peeraer G, et al. Content validity of workplace-based portfolios: a multi-centre study. Med Teach. 2016;38(9):936‐945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Montrezor LH. Lectures and collaborative working improves the performance of medical students. Adv Physiol Educ. 2021;45(1):18‐23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Zundel S, Blumenstock G, Zipfel S, Herrmann-Werner A, Holderried F. Portfolios enhance clinical activity in surgical clerks. J Surg Educ. 2015;72(5):927‐935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Dolan BM, O'Brien CL, Cameron KA, Green MM. A qualitative analysis of narrative preclerkship assessment data to evaluate teamwork skills. Teach Learn Med. 2018;30(4):395‐403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Roberts C, Shadbolt N, Clark T, Simpson P. The reliability and validity of a portfolio designed as a programmatic assessment of performance in an integrated clinical placement. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14:197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Adeleke OA, Cawe B, Yogeswaran P. Opportunity for change: undergraduate training in family medicine. S Afr Fam Pract (2004). 2020;62(1):1‐3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Brits H, Bezuidenhout J, Van der Merwe LJ. Quality assessment in undergraduate medical training: how to bridge the gap between what we do and what we should do. Pan African Medical Journal. 2020;36(79). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Pinto-Powell R, Lahey T. Just a game: the dangers of quantifying medical student professionalism. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(8):1641‐1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Bierer SB, Dannefer EF, Tetzlaff JE. Time to loosen the apron strings: cohort-based evaluation of a learner-driven remediation model at One medical school. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(9):1339‐1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Davis MH, Ponnamperuma GG. Examiner perceptions of a portfolio assessment process. Med Teach. 2010;32(5):e211‐e215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Shiozawa T, Glauben M, Banzhaf M, et al. An insight into professional identity formation: qualitative analyses of Two reflection interventions during the dissection course. Anat Sci Educ. 2020;13(3):320‐332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.O'Brien C, Thomas J, Green M. What is the relationship between a preclerkship portfolio review and later performance in clerkships? Acad Med. 2017;93(1):113–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Kassab SE, Bidmos M, Nomikos M, et al. Medical Students’ perspectives on an assessment of reflective portfolios [response to letter]. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2020;11:495‐496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Pitkälä KH, Mäntyranta T. Feelings related to first patient experiences in medical school A qualitative study on students’ personal portfolios. Pt Educ Couns. 2004;54(2):171‐177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Royce CS, Everett EN, Craig LB, et al. To the point: advising students applying to obstetrics and gynecology residency in 2020 and beyond. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;224(2):148‐157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Goldie J, Dowie A, Cotton P, Morrison J. Teaching professionalism in the early years of a medical curriculum: a qualitative study. Med Educ. 2007;41(6):610‐617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Duque G, Finkelstein A, Roberts A, Tabatabai D, Gold S, Winer L. Members of the division of geriatric medicine MU learning while evaluating: the use of an electronic evaluation portfolio in a geriatric medicine clerkship. BMC Med Educ. 2006;6:1‐7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Sturmberg JP, Farmer L. Educating capable doctors-A portfolio approach. Linking learning and assessment. Med Teach. 2009;31(3):e85‐e89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Souza AD, Vaswani V. Diversity in approach to teaching and assessing ethics education for medical undergraduates: a scoping review. Annals of Medicine and Surgery. 2020;56:178‐185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Amin TT, Kaliyadan F, Al-Muhaidib NS. Medical students’ assessment preferences at king faisal university, Saudi Arabia. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2011;2:95‐103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Kennedy G, Rea JNM, Rea IM. Prompting medical students to self-assess their learning needs during the ageing and health module: a mixed methods study. Med Educ Online. 2019;24(1):1579558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Driessen E, van Tartwijk J, Dornan T. The self critical doctor: helping students become more reflective. Br Med J. 2008;336(7648):827‐830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.