Abstract

The efficacy of trovafloxacin against Staphylococcus aureus and viridans group streptococci was investigated in vitro and in an experimental model of endocarditis. The MICs at which trovafloxacin and ciprofloxacin inhibited 90% of clinical isolates of such bacteria (MIC90s) were (i) 0.03 and 2 mg/liter, respectively, for 30 ciprofloxacin-susceptible S. aureus isolates, (ii) 32 and 128 mg/liter, respectively, for 20 ciprofloxacin-resistant S. aureus isolates, and (iii) 0.25 and 8 mg/liter, respectively, for 28 viridans group streptococci. Rats with aortic vegetations were infected with either of two ciprofloxacin-susceptible but methicillin-resistant S. aureus strains (strains COL and P8), one penicillin-susceptible Streptococcus sanguis strain, or one penicillin-resistant Streptococcus mitis strain. Rats were treated for 3 or 5 days with doses that resulted in kinetics that simulated those achieved in humans with trovafloxacin (200 mg orally once a day), ciprofloxacin (750 mg orally twice a day), vancomycin (1 g intravenously twice a day), or ceftriaxone (2 g intravenously once a day). Against the staphylococci, the activities of both trovafloxacin and ciprofloxacin were equivalent to that of vancomycin, and treatment of endocarditis with these drugs was successful (P < 0.05). However, ciprofloxacin selected for resistant derivatives in vitro and in vivo, whereas trovafloxacin was 10 to 100 times less prone than ciprofloxacin to select for resistance in vitro and did not select for resistance in vivo. Against the two streptococcal isolates, trovafloxacin significantly (P < 0.05) decreased bacterial counts in the vegetations but was less effective than the control drug, ceftriaxone. Thus, a simulated oral dose of trovafloxacin (200 mg per day) was effective against ciprofloxacin-susceptible staphylococci and was less likely than ciprofloxacin to select for resistance. The simulated oral dose of trovafloxacin also had some activity against streptococcal endocarditis, but optimal treatment of infections caused by such organisms might require higher doses of the drug.

The emergence of bacterial resistance to most classes of antibiotics has stimulated the search for new drugs. Among these, the quinolone family of molecules has undergone a fast development and a series of promising substances has been generated. In the late 1980s, compounds such as ciprofloxacin, norfloxacin, and ofloxacin were proven to have invaluable efficacy against gram-negative bacteria (25). Nevertheless, these drugs were poorly active against gram-positive pathogens. Thus, they did not offer the awaited alternative against emerging multidrug-resistant staphylococci and streptococci.

Newer quinolones such as pefloxacin, temafloxacin, levofloxacin, sparfloxacin, clinafloxacin, and trovafloxacin demonstrate enhanced activities against gram-positive bacteria (27). Most of these agents also produce higher concentrations in serum and have more prolonged serum half-lives than those of the older quinolones, thus ensuring a greater therapeutic margin than their former counterparts (30). These improvements and the fact that quinolones are well absorbed after oral administration suggest that use of these newer molecules may allow a decrease in the numbers of daily drug doses that are required and may also partially replace parenteral treatment with oral therapy.

Despite these advantages, however, some of these new compounds appeared to be unacceptably toxic (4) or to produce undesirable side effects that may limit their use (11). Moreover, the therapeutic modalities of these new drugs against certain infections and/or certain specific pathogens remain incompletely specified. For instance, the efficacy of oral administration of sparfloxacin, trovafloxacin, or other new quinolones against severe staphylococcal infections is unclear. Likewise, their efficacy against severe streptococcal infection in animals or humans has not been much investigated.

The experiments described below address more specifically these issues with regard to trovafloxacin, a new quinolone with enhanced activity against gram-positive pathogens (17). Rats with catheter-induced aortic vegetations were infected either with ciprofloxacin-susceptible, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) or penicillin-susceptible or penicillin-resistant streptococci. Infected rats were treated with (i) the new quinolone trovafloxacin, (ii) the older quinolone ciprofloxacin, or (iii) vancomycin or ceftriaxone (used as control drugs against experimental endocarditis due to MRSA and streptococci, respectively) at doses that resulted in kinetics that simulated those achieved in humans. The efficacies of the quinolones were evaluated both in terms of therapeutic success and in terms of the risk of selection for drug resistance in vitro and in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Microorganisms and growth conditions.

The bacteria used in the experiments with animal were previously used in a model of experimental endocarditis (13, 15) and are described in Table 1. They included two ciprofloxacin-susceptible clinical isolates of MRSA (strains COL and P8) and two clinical isolates of streptococci (one susceptible to and one resistant to penicillin). Moreover, a total of 87 additional clinical isolates of staphylococci and streptococci originating from various geographical areas were tested in vitro for ciprofloxacin and trovafloxacin MICs for the isolates. These included (i) 46 isolates of ciprofloxacin-susceptible S. aureus (16 methicillin-susceptible S. aureus [MSSA] isolates and 30 MRSA isolates), (ii) 20 isolates of ciprofloxacin-resistant MRSA, and (iii) 27 isolates of the viridans group streptococci. Unless otherwise stated, the staphylococci were grown at 35°C in tryptic soy broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) supplemented with 2% NaCl with aeration in a shaking incubator at 120 rpm. Streptococci were grown in brain heart infusion (Difco) without aeration. All the organisms were plated on Columbia agar plates (Becton Dickinson Microbiology Systems, Cockeysville, Md.) supplemented with 3% blood. Bacterial stocks were kept at −70°C in tryptic soy broth (for staphylococci) or brain heart infusion (for streptococci) supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) glycerol.

TABLE 1.

MICs of various antibiotics for bacteria tested in rats with experimental endocarditis

| Bacterial strain | MIC (mg/liter)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trovafloxacin | Ciprofloxacin | Ceftriaxone | Vancomycin | |

| MRSA COL | 0.06 | 0.25 | NDa | 2 |

| MRSA P8 | 0.03 | 0.5 | ND | 1 |

| S. sanguis “Du” | 0.06 | 8 | 0.03 | ND |

| S. mitis 531 | 0.06 | 2 | 2 | ND |

ND, not determined.

Antibiotics.

Trovafloxacin and alatrofloxacin (the intravenous prodrug of trovafloxacin) were provided by Pfizer Inc. (Groton, Conn.), ciprofloxacin was purchased from Bayer AG (Wuppertal, Germany), vancomycin was purchased from Eli Lilly (Geneva, Switzerland), and ceftriaxone was purchased from Roche Pharma (Reinach, Switzerland).

Susceptibility testing and time-kill curve studies.

The MICs were determined by a previously described broth macrodilution method (24) with a final inoculum of 105 to 106 CFU/ml. The MIC was defined as the lowest antibiotic concentration that inhibited visible bacterial growth after 24 h of incubation at 35°C.

For time-kill curve studies, series of flasks containing fresh prewarmed medium were inoculated with ca. 106 CFU/ml (final concentration) from an overnight culture of bacteria and were further incubated at 35°C as described above. Immediately after inoculation, the antibiotics were added to the flasks at final concentrations approximating peak and trough levels of antibiotics produced in the serum of humans after the administration of therapeutic doses of the test drugs (see Results). These concentrations were (i) 2.5 mg/liter at 1 h (time to the maximum concentration of drug in serum [Tmax]) and 0.5 mg/liter at 24 h for trovafloxacin, (ii) 2.0 mg/liter at 1 h (Tmax) and 0.25 mg/liter at 12 h for ciprofloxacin, (iii) 40 mg/liter at 1 h (Tmax) and 5 mg/liter at 12 h for vancomycin, and (iv) 200 mg/liter at 0.5 h (Tmax) and 15 mg/liter at 24 h for ceftriaxone. Viable counts were determined just before and at various times after the addition of the antibiotics by plating adequate dilutions of the cultures on agar plates. To avoid antibiotic carryover, 0.5-ml samples of the cultures were transferred from the flasks into microcentrifuge tubes, and the bacteria were spun and resuspended twice in antibiotic-free medium to remove residual drugs. Then the bacterial suspensions were serially diluted and plated on Columbia agar. When ceftriaxone was used, the bacteria were plated on penicillinase-containing agar (Bacto-Penase concentrate [2,000 U/ml]; Difco) as an additional precaution to avoid antibiotic carryover. Each time-kill experiment was repeated at least three times independently. In certain tests, 50% decomplemented rat serum (heated for 30 min at 56°C) was added to the growth medium to investigate the effect of serum on susceptibility to the antibiotics.

Production of endocarditis and infusion pump installation.

Sterile aortic vegetations were produced in rats as described previously (19). An intravenous (i.v.) line was inserted via the jugular vein into the superior vena cava and was connected to a programmable infusion pump (Pump 44; Harvard Apparatus, Inc., South Natick, Mass.) to deliver the antibiotics (16). The pump was set to deliver a volume of 0.2 ml of saline per h to keep the catheter open until the onset of therapy. No i.v. lines were placed in the control animals. This did not affect the frequency of infection.

Bacterial endocarditis was induced 24 h after catheterization by i.v. challenge of the animals with either 105 CFU of the MRSA isolates or 107 CFU of the streptococcal test isolates. These inocula were 10 and 100 times larger, respectively, than the minimum inoculum of the test staphylococci and streptococci producing endocarditis in 90% of the untreated rats.

Antibiotic treatment of experimental endocarditis.

Therapy was started 12 h after inoculation in the case of MRSA and 24 h after inoculation in the case streptococci and lasted for 3 or 5 days. Antibiotics were administered at changing flow rates with the pump described above. This allowed the simulation in rat serum of the kinetics produced in the serum of humans by treatment with either (i) 200 mg of trovafloxacin orally every 24 h (33), (ii) 750 mg of ciprofloxacin orally every 12 h (5), (iii) 1 g of vancomycin i.v. every 12 h (3), or (iv) 2 g of ceftriaxone i.v. every 24 h (26). This required total amounts of antibiotics (in milligrams per kilogram of body weight) of 44.2 mg of alatrofloxacin (the intravenous prodrug of trovafloxacin) per 24 h, 37.4 mg of ciprofloxacin per 12 h, 23.2 mg of vancomycin per 12 h, and 1.06 g of ceftriaxone per 24 h.

Antibiotic concentrations in serum.

The concentrations of antibiotic in serum were determined on day 2 of therapy in groups of four to six uninfected or infected rats per experiment. The levels of drugs in the infected animals came from internal controls of therapeutic experiments, in which adequate drug delivery was tested routinely. Blood was drawn by puncturing the periorbital sinuses of the animals at several time points during and after antibiotic administration. Antibiotic concentrations were determined by an agar diffusion assay with antibiotic medium 1 (Difco) by using Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633 as the indicator organism for trovafloxacin, ciprofloxacin, and vancomycin and Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 as the indicator organism for ceftriaxone. The diluent was pooled rat serum. The limits of detection of the assays were 0.03 mg/liter for trovafloxacin, 0.12 mg/liter for ciprofloxacin, 0.6 mg/liter for vancomycin, and 3 mg/liter for ceftriaxone. The linearities of the standard curves were assessed with a regression coefficient of ≥0.995, and intraplate and interplate variations were ≤10%.

Evaluation of infection.

Control rats were killed at the time of treatment onset, i.e., 12 and 24 h after inoculation for MRSA and streptococci, respectively, in order to measure both the frequency and the severity of valve infection at the start of therapy. Treated rats were killed at 12 h after the trough level of the last antibiotic dose in serum had been achieved, thus allowing minimization of the risk of antibiotic carryover from the vegetation onto the culture plates. The vegetations were sterilely dissected, weighed, homogenized in 1 ml of saline, and serially diluted before being plated for colony counts. Quantitative cultures of blood and spleen specimens were performed in parallel. The number of colonies growing on the plates was determined after 48 h of incubation at 35°C. The bacterial densities in the vegetations were expressed as log10 CFU per gram of tissue. The dilution technique permitted the detection of ≥2 log10 CFU/g of vegetation. For statistical comparisons of differences between the bacterial densities in the vegetations for various treatment groups, culture-negative vegetations were considered to contain 2 log10 CFU/g.

Detection of the emergence of antibiotic resistance in vivo.

To detect the emergence of quinolone-resistant bacteria during endocarditis therapy, 0.1-ml portions of each undiluted homogenate from vegetations from animals treated with either trovafloxacin or ciprofloxacin were plated in parallel on plain agar and on agar plates supplemented with the test drug at four or eight times the MIC. In addition, in the case of treatment failure, standard MIC determinations were also performed for bacteria that grew from vegetations on antibiotic-free agar. The colonies were pooled and grown in broth cultures, and MICs were determined as described above. This screening was not performed for vancomycin- and ceftriaxone-treated animals.

Selection of quinolone-resistant derivatives in vitro.

Additional experiments were performed to test the propensity of ciprofloxacin and trovafloxacin to select for quinolone-resistant derivatives in vitro. First, large inocula (109 to 1010 CFU) were spread onto agar plates containing either no antibiotic or antibiotics at concentrations equal to two, four, or eight times the MIC for the bacteria. The plates were then incubated for 48 h at 35°C before the colonies were counted. The colonies growing on antibiotic-containing plates were then retested for the new, increased MIC in liquid culture.

Second, selection for quinolone resistance was also performed in broth cultures by exposing the bacteria to stepwise increasing concentrations of antibiotic (15). Series of tubes containing twofold increasing concentrations of drugs were inoculated with 106 CFU/ml (final concentration), as for the MIC determinations. After 24 h of incubation, 0.1-ml samples from the tubes containing the highest antibiotic concentration and still showing turbidity were used to inoculate a new series of tubes containing antibiotic dilutions. The experiment was repeated several times, and the increase in MICs was followed.

Determination of antibiotic binding to serum proteins and drug concentrations in cardiac vegetations.

Binding of trovafloxacin and ciprofloxacin to serum proteins of rats was determined by a previously described ultrafiltration method (9) by using the Amicon Centrifree System (Amicon Inc., Beverly, Mass.). Both drugs were tested at concentrations of 0.6, 1.25, 2.5, and 5 mg of antibiotic per liter diluted either in decomplemented rat serum or in saline, which was used as a control. The drug concentrations in the original samples and in the ultrafiltrates were determined by an agar diffusion bioassay similar to that used to measure drug levels in serum (see above). When the antibiotics were diluted in saline, the amounts of antibiotics recovered in the ultrafiltrates invariably ranged between 90 and 96% of the amounts of the drugs present in the original sample.

The concentrations of trovafloxacin and ciprofloxacin in cardiac vegetations were determined on day 2 of therapy, at the Tmax. Sparfloxacin was used as a control, because this quinolone was shown to distribute homogeneously in the vegetation (10). Sparfloxacin was given to the rats as described previously (13). The Tmax was 1 h for all three quinolones tested. The drug concentrations in the vegetations, either in intact vegetations or in the supernatant of homogenized tissue, were measured by an agar diffusion assay as previously described (6, 7). E. coli Kp 1976-712 was used as the indicator organism for sparfloxacin (13).

Statistical analysis.

The median bacterial densities in the vegetations of various treatment groups were compared by the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance on ranks, with subsequent pairwise multiple comparison procedures done by Dunn’s method. Overall, differences were considered significant when P was ≤0.05 by use of two-tailed significance levels.

RESULTS

In vitro drug susceptibility.

Table 1 indicates that trovafloxacin was up to 10 times more active than ciprofloxacin against the two staphylococci and the two streptococci used to infect the animals. Against the additional 46 ciprofloxacin-susceptible isolates of MSSA and MRSA, the MIC at which 90% of the bacteria were inhibited (MIC90) was 0.03 mg/liter for trovafloxacin (range, 0.03 to 0.06 mg/liter), whereas it was 1 mg/liter for ciprofloxacin (range, 0.06 to 2 mg/liter). For the 20 ciprofloxacin-resistant MRSA isolates, the MIC90 was 32 mg/liter for trovafloxacin (range, 4 to 64 mg/liter), whereas it was ≥128 mg/liter for ciprofloxacin (range, 32 to ≥128 mg/liter). For the 28 clinical isolates of streptococci, the MIC90 was 0.25 mg/liter for trovafloxacin (range, ≤0.03 to 0.5 mg/liter), whereas it was 8 mg/liter for ciprofloxacin (range, 0.5 to 8 mg/liter). Thus, trovafloxacin was more active than ciprofloxacin against a number of staphylococcal and streptococcal isolates. However, its MIC for the ciprofloxacin-resistant MRSA collected from the clinical environment was already above its susceptibility cutoff of 1 to 2 mg/liter (20, 33).

Regarding the control drugs, the MRSA isolates used to infect the animals were all susceptible to vancomycin. In contrast, only the penicillin-susceptible strain S. sanguis “Du” was susceptible to ceftriaxone, whereas the penicillin-resistant strain S. mitis 531 was resistant to this compound (Table 1).

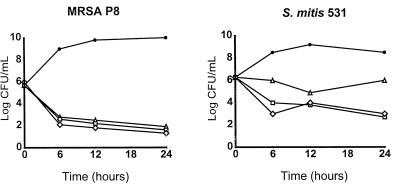

Time-kill curve studies.

Figure 1 depicts the results of the time-kill curve studies performed with drug concentrations simulating either the peak (2.5 mg/liter) or the trough (0.5 mg/liter) levels of trovafloxacin produced in the serum of humans or rats during standard drug treatment (see below). The results indicate the means of three independent experiments. The relative variation between these experiments was ≤15%. The peak and trough drug concentrations in serum resulted in a rapid decrease in viable counts of ≥3 log CFU/ml within 6 h of treatment, followed by a plateau during which bacterial numbers remained stable for up to 24 h. This was observed against both the staphylococcal and the streptococcal isolates tested in rats.

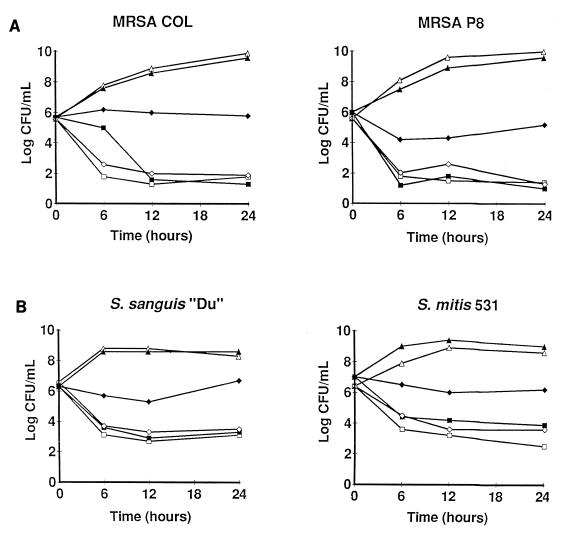

FIG. 1.

Time-kill experiments in broth cultures supplemented or not supplemented with rat serum. The two ciprofloxacin-susceptible MRSA isolates (MRSA COL and MRSA P8) (A) and the two viridans group streptococci (S. sanguis “Du” and S. mitis 531) (B) were treated with the peak (2.5 mg/liter; squares) and the trough (0.5 mg/liter; diamonds) concentrations of trovafloxacin produced in humans and rats after the administration of therapeutic doses of the drug. The bacteria were grown either in plain Mueller-Hinton broth (open symbols) or in Mueller-Hinton broth supplemented with 50% decomplemented rat serum (closed symbols). Triangles, untreated control cultures. The results are the means of three independent experiments, with a relative variation between experiments of ≤15%.

Control time-kill curve studies with ciprofloxacin were performed only with the two ciprofloxacin-susceptible MRSA isolates. As with trovafloxacin, the concentrations of ciprofloxacin simulating peak levels in serum (2 mg/liter) inflicted a ≥3-log-CFU/ml loss of viability on bacterial cultures exposed to the drug for 24 h. At trough concentrations in serum (0.25 mg/liter), on the other hand, ciprofloxacin-treated cultures rapidly became overgrown by staphylococcal variants for which the MIC of the compound was increased fourfold. For these low-level ciprofloxacin-resistant variants trovafloxacin MICs were unchanged.

Except for the limitation with trough concentrations of ciprofloxacin in serum, the control drugs used to treat the animals were all bactericidal against their respective target organisms, i.e., vancomycin against staphylococci and ceftriaxone against streptococci (data not shown).

Effect of serum on trovafloxacin-induced killing and penetration of trovafloxacin into cardiac vegetations.

Trovafloxacin was reported to be relatively highly bound (ca. 75%) to human serum proteins (33) and highly bound (ca. 90%) to rat serum proteins (32). This was confirmed in the present experiments. Indeed, the median level of binding of trovafloxacin to rat serum proteins (expressed as the percentage of the drug bound to serum proteins compared to the total drug concentration in the sera of six individual rats) was 91% (range, 75 to 96%), whereas it was 11% (range, 5 to 17%) for ciprofloxacin. These values were in accordance with those published in the literature (23, 32).

To determine the impact of trovafloxacin binding to serum protein on in vitro susceptibility test results, the MICs and time-kill experiments whose results are presented in Fig. 1 were repeated in the presence of 50% decomplemented rat serum. Serum did not affect bacterial growth (Fig. 1). However, it did increase the MICs of trovafloxacin twofold (data not shown) and blocked the drug-induced killing at drug concentrations simulating the trough levels of the antibiotic in human serum (Fig. 1). This serum effect was not observed with the other antibiotics tested, in particular, ceftriaxone (data not shown in Fig. 1), which is also highly bound to serum proteins (31). In this case, it is possible that the high ratio between the concentration of ceftriaxone used in time-kill experiments and its MIC for the test streptococci obliterated the effect of protein binding in the killing studies.

In certain experiments, the level of intravegetation penetration of trovafloxacin was determined and compared to those of ciprofloxacin and sparfloxacin. Drug levels were measured on day 2 of therapy, at 1 h after drug administration. This timing corresponded to the Tmax for all three antibiotics tested. Intravegetation penetration was expressed as the percentage of the drug concentration measured in the vegetation compared to the concentration measured in the sera of six individual rats. Intravegetation penetration was 22.5% for trovafloxacin (range, 13 to 37%), whereas it was 59% for ciprofloxacin (range, 54 to 89%) and 92.5% for sparfloxacin (range, 62 to 123%). These results were identical whether the drug concentration was measured in intact vegetations or in homogenized vegetations (see Materials and Methods). Thus, trovafloxacin was both highly bound to rat serum constituents and was relatively poorly concentrated in the cardiac lesions.

Antibiotic levels in rat serum.

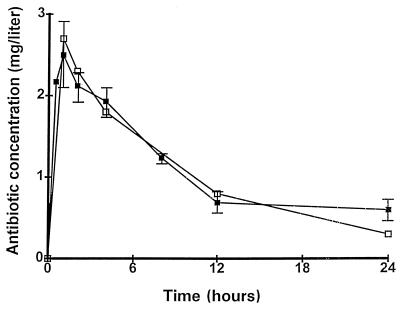

The concentrations of antibiotics in the serum of rats were adjusted to simulate the pharmacokinetics produced after the administration of 200-mg oral doses of trovafloxacin to humans (see Materials and Methods). Figure 2 presents the profiles of these pharmacokinetics either produced in humans (33) or simulated in rats. The simulations in rats of the kinetics of ceftriaxone, ciprofloxacin, and vancomycin in human serum were as described previously (13–15).

FIG. 2.

Concentrations of trovafloxacin in the serum of humans following the administration of an oral dose of 200 mg of trovafloxacin (open symbols) (33) and simulation of these pharmacokinetics in rats (closed symbols). The prodrug alatrofloxacin was administered i.v. to the animals with the infusion pump described in the text. The effective drug concentration was determined by a bioassay in which trovafloxacin was used as a control. Each datum point on the graph represents the mean ± standard deviation of four to six determinations with individual rats.

In vivo experiments. (i) Trovafloxacin treatment of experimental endocarditis due to ciprofloxacin-susceptible MRSA and risk of quinolone resistance selection.

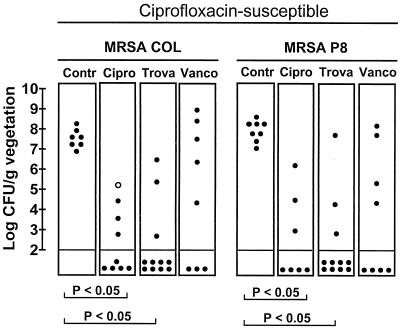

Figure 3 indicates that trovafloxacin and ciprofloxacin were both successful as treatments for valve infections due to the two ciprofloxacin-susceptible MRSA (P < 0.05). The two drugs were as effective as the control treatment with vancomycin. However, a potentially important difference between trovafloxacin and ciprofloxacin therapy was that one treatment failure in the group treated with ciprofloxacin was due to a staphylococcal variant for which the MIC of this drug was increased fourfold. In contrast, no treatment failures in the trovafloxacin-treated rats were due to drug-resistant derivatives. As in the time-kill experiments, for the variant for which an increased ciprofloxacin MIC was selected in vivo, the trovafloxacin MIC was unchanged. Cultures of spleen and blood specimens from all animals with sterile valve cultures were negative.

FIG. 3.

Outcome of 3 days of therapy of experimental endocarditis caused by the ciprofloxacin-susceptible and MRSA strains COL and P8. Each dot in the figure represents the bacterial density in the vegetation of a single animal. The open dot in the MRSA COL group treated with ciprofloxacin represents the data for one animal in which the ciprofloxacin MIC for the bacteria from the valve was increased. P was <0.05 when the results were compared by the Kruskal-Wallis test. Contr, control; Cipro, ciprofloxacin; Trova, trovafloxacin; Vanco, vancomycin.

To more accurately evaluate the risk of selection for quinolone resistance by the two drugs, the following additional tests were performed. First, large inocula (ca. 5 × 109 CFU) of the test staphylococci were spread on agar plates containing increasing concentrations of antibiotics (15). In this experiment, the frequency at which colonies grew on the plates containing two and four times the MIC of ciprofloxacin varied between 10−7 and 10−8. Upon retesting, all these variants had acquired a low level of resistance to ciprofloxacin, equal to four to eight times the original MIC. In comparison, trovafloxacin-resistant variants appeared only on plates containing the MIC of the drug at a frequency 10−8 and 10−9, i.e., at a frequency 10 to 100 times lower than that for variants on plates containing ciprofloxacin. No resistant variants grew on plates containing higher drug concentrations. This low frequency was similar to the resistance frequencies reported earlier in tests with this compound (1).

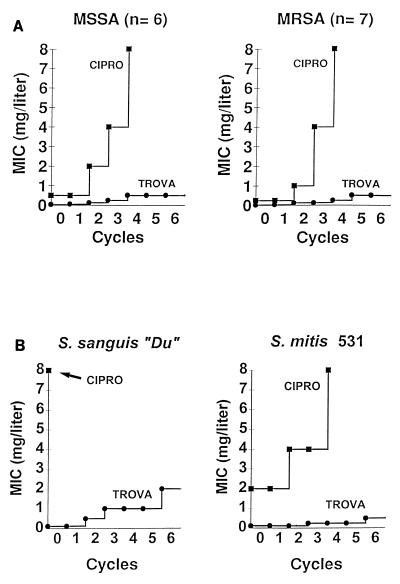

Second, six ciprofloxacin-susceptible MSSA isolates and seven ciprofloxacin-susceptible MRSA isolates were exposed individually to twofold stepwise increasing concentrations of the test quinolones. Figure 4 indicates that stepwise exposure to ciprofloxacin resulted in the rapid emergence from among all the staphylococci tested of variants with high levels of resistance. With ciprofloxacin, this selection procedure produced quite sharp increases in the MIC from one step to the other, resulting in MICs well above the therapeutic range of this drug. In contrast, trovafloxacin was notably less prone than ciprofloxacin to select for resistance. Moreover, when this experiment was repeated with the two streptococci tested in rats instead of the staphylococci, a similar low tendency of trovafloxacin to select for resistance was observed (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

Selection of ciprofloxacin (CIPRO)-resistant and trovafloxacin (TROVA)-resistant derivatives of staphylococci (A) and streptococci (B) exposed to stepwise increasing concentrations of ciprofloxacin or trovafloxacin. Series of tubes containing twofold serial dilutions of either of the test drugs were inoculated with a final concentration of 106 CFU of the organisms per ml and were further incubated for 24 h at 35°C, as described in the text for the MIC tests. On the next day, the tube with the highest antibiotic concentration still showing turbidity was used to inoculate a new series of antibiotic-containing tubes. The procedure was repeated, and the increase in the MIC was followed over time. (A) Results of this kind of passage for six clinical isolates of MSSA and seven clinical isolates of MRSA. The graph indicates the median results for the test organisms. Variations between the isolates did not exceed 1 tube dilution. (B) Results of similar experiments performed with the two streptococcal isolates tested in rats.

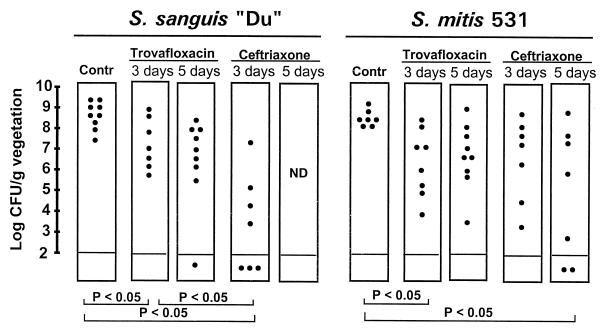

(ii) Trovafloxacin treatment of experimental endocarditis due to penicillin-susceptible and penicillin-resistant streptococci.

The good in vivo efficacy of trovafloxacin against infections due to ciprofloxacin-susceptible staphylococci prompted the further investigation of this new compound against one penicillin-susceptible and one penicillin-resistant streptococcal isolate. Although naturally resistant to ciprofloxacin, both bacteria were susceptible to trovafloxacin. Figure 5 presents the results of these experiments. Overall, 3 days of treatment with trovafloxacin significantly decreased bacterial densities in the vegetations compared to those in the vegetations of control rats (P < 0.05). Despite this result, however, trovafloxacin was significantly less effective than ceftriaxone against the penicillin-susceptible streptococcus (P < 0.05) and was not more active than this control antibiotic against the penicillin-resistant isolate.

FIG. 5.

Outcomes of 3 and 5 days of therapy of experimental endocarditis due to the penicillin-susceptible streptococcus S. sanguis “Du” and the penicillin-resistant streptococcus S. mitis 531. Each dot represents the bacterial density in the vegetation of a single animal. P was <0.05 when the results were compared by the Kruskal-Wallis test.

To investigate whether a more prolonged course of trovafloxacin might improve its efficacy, additional experiments were run in which antibiotic treatment was given for 5 days instead of 3 days. Figure 5 indicates that the prolonged treatment did not ameliorate the therapeutic results obtained with trovafloxacin. Importantly, however, no trovafloxacin-resistant derivatives were isolated from infected vegetations. Thus, while trovafloxacin had some activity against experimental endocarditis due to viridans group streptococci, it was less effective than ceftriaxone against the penicillin-susceptible streptococcus and was not better than this antibiotic against the penicillin-resistant strain.

Studies on the discrepancy between the therapeutic efficacy of trovafloxacin against staphylococcal and streptococcal experimental endocarditis.

The staphylococcal and streptococcal isolates used to infect the rats were equally susceptible to growth inhibition and killing by trovafloxacin (Table 1 and Fig. 1). Therefore, the discrepancy between the responses of these two organisms to therapy for experimental endocarditis was unexpected. To seek an explanation for this difference, additional time-kill experiments were performed with these bacteria by using low concentrations of trovafloxacin. Figure 6 depicts representative results of these studies for (i) MRSA P8 and (ii) the penicillin-resistant streptococcus S. mitis 531. Against MRSA P8, trovafloxacin was highly bactericidal even when it was used at concentrations as low as eight, four, and two times the MIC. These concentrations were 1.5 to 10 times lower than the trough concentrations of trovafloxacin in serum during therapy in humans and in rats (Fig. 2). In striking contrast, the penicillin-resistant streptococcus S. mitis 531 was barely killed by these low concentrations of trovafloxacin in vitro. The same discrepancy was observed with MRSA COL and the penicillin-susceptible streptococcus S. sanguis “Du.” MRSA COL was rapidly killed by low concentrations of trovafloxacin, whereas S. sanguis was refractory to drug-induced killing under these conditions (data not shown). Importantly, no resistant derivatives of either of the test bacteria were detected at the end of the experiments, thus confirming the low propensity of trovafloxacin to select for resistance.

FIG. 6.

Time-kill experiments with low concentrations of trovafloxacin. The test isolates MRSA P8 and the penicillin-resistant streptococcus S. mitis 531 were treated with two times (open triangles), four times (open squares) and eight times (open diamonds) the MIC of trovafloxacin for each isolate. Closed circles represent the results for untreated control cultures.

DISCUSSION

The present experiments investigated the efficacy of trovafloxacin in the setting of experimental endocarditis due to staphylococci and streptococci. This experimental model is important because it tests the efficacy of a drug against bacteria packed in an environment quasi-devoid of cellular host defenses, i.e., inside infected vegetations (12). Moreover, gram-positive organisms also resist complement-induced killing, thus ruling out this additional nonspecific humoral defense system. Therefore, simulation of human drug pharmacokinetics in such animal models helps in the evaluation of the activities of new antibiotics in a context that minimizes biases related to host defense factors.

The results of these experiments highlight some potentially important benefits of trovafloxacin, as well as a few limitations that might be considered for the further development of therapeutic modalities for humans. The most important benefit of trovafloxacin was its excellent in vitro and in vivo activity against ciprofloxacin-susceptible staphylococci, as well as its very low propensity to select for quinolone resistance both in the test tubes and in animal experiments. This was a major difference with ciprofloxacin, which was shown to select rapidly for quinolone-resistant derivatives of staphylococci in the present work as well as in previous studies (15, 21). Importantly, the difference was valid both for MSSA and for MRSA in in vitro tests, indicating that the methicillin resistance background did not affect the emergence of trovafloxacin resistance. This absence of a difference also suggests that the present therapeutic results obtained with MRSA are likely to be valid for MSSA as well.

The low tendency of trovafloxacin to select for quinolone resistance was not restricted to ciprofloxacin-susceptible staphylococci. Indeed, despite its poor therapeutic efficacy against experimental endocarditis due to streptococci, no streptococcal derivatives for which trovafloxacin MICs were increased were detected in animals that were infected with these bacteria but that failed treatment. The reason for this low rate of resistance selection was unclear. It could have resulted from the combination of the low susceptibility of trovafloxacin to NorA-mediated active drug efflux or other extrusion mechanisms and its good affinity for its topoisomerase and gyrase molecular targets (8, 18). If trovafloxacin remained highly antibacterial at concentrations very close to its MIC for the target bacterium, it could have impaired the capacity of the organisms to acquire or express resistance even when the therapeutic margin was low. The present experiments indicate that this hypothesis might hold true for staphylococci. Indeed, these organisms were exquisitely susceptible to killing by trovafloxacin even when they were exposed to very low concentrations (e.g., twofold the MIC) of the drug. However, this was not the case for streptococci, which were refractory to trovafloxacin-induced killing at such low drug concentrations.

Alternatively, it is also possible that the development of high-level resistance to trovafloxacin is particularly costly for the organisms, either because it might require multiple chromosomal mutations or because it might involve mutations that are potentially harmful for the bacterium. The answer to this question requires further investigations.

Aside from these beneficial effects, an unexpected limitation of trovafloxacin was its relatively poor efficacy against experimental endocarditis due to streptococci. This was in contrast to its excellent activity against these organisms in vitro. As mentioned above, failures of treatment of streptococcal endocarditis were not due to resistance selection. The fact that trovafloxacin did less well in vivo than in vitro was tentatively attributed to its high level of serum binding (ca. 90% in the present experiments) in rats (32) and its resulting low concentration in the vegetation. However, the explanation is likely to be more complicated. First, for the two streptococcal test isolates, which responded poorly to in vivo therapy, trovafloxacin MICs were similar to those for the two test staphylococci, and the streptococcal isolates were rapidly killed by therapeutic levels of the drug in vitro. Second, there was no difference in the bacterial counts in the vegetations or the size of vegetations (data not shown) that could explain subtle pharmacodynamic differences between the two types of infection. Third, others (28, 29) also recently reported a similar marginal efficacy of trovafloxacin against experimental streptococcal endocarditis, and the difference between the therapeutic efficacy against these two types of pathogens does not seem to be bound to trovafloxacin alone. A lower level of efficacy against experimental streptococcal endocarditis than against experimental staphylococcal endocarditis was also observed with other quinolones such as sparfloxacin (2, 13). This difference was recently referred to as the staphylococcal-streptococcal paradox of new quinolones.

In the present experiments, a tentative explanation for this difference came from time-kill experiments performed with low drug concentrations. These in vitro tests highlighted a striking discrepancy between the capacity of low levels of trovafloxacin (e.g., twofold the MIC) to kill staphylococci effectively and the inability of similar drug concentrations to kill streptococci. This difference is likely to be particularly relevant for drugs that do not afford a high therapeutic margin and/or that are not highly concentrated at the infected site. However, while this difference provides a potential explanation for the present observation in the setting of experimental endocarditis, it does not explain why trovafloxacin—and supposedly also other newer quinolones—might be more bactericidal against staphylococci than against viridans group streptococci. Thus, a solution to the staphylococcal-streptococcal paradox of newer quinolones will require further studies.

In summary, the results of the experiments described here indicate that the excellent in vitro antistaphylococcal activity of trovafloxacin against quinolone-susceptible strains translated into in vivo efficacy. Since this was achieved with pharmacokinetics simulating those achieved in humans after the administration of oral doses of the drug, it adds to a recent publication demonstrating that trovafloxacin was effective when it was administered to animals at higher doses (i.e., 300 mg i.v.) (22). Moreover, the fact that trovafloxacin is less bound to plasma proteins in humans (ca. 75%) (33) than in rats (≥90%) provides an additional margin of safety for its use against staphylococcal infections in humans. On the other hand, viridans group streptococci responded only marginally to therapy, despite their excellent in vitro susceptibilities. Although these organisms might respond to larger drug doses, the observation is important because it emphasizes that optimistic in vitro susceptibility test results might not always predict therapeutic results.

A most important property of trovafloxacin was its low propensity to select for resistance, at least with the organisms used in these experiments. If this characteristic is confirmed on a larger scale, it may have a fundamental implication on the use of quinolones in the future. During antibiotic treatment of a specific infection, the pressure for resistance is applied on the global bacterial flora of the patient. Accordingly, use of an older quinolone against a urinary tract infection might select for quinolone-resistant staphylococci in the nose. Whether trovafloxacin or other newer quinolones might lower this potential risk remains to be determined.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Marlyse Giddey for outstanding technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barry A L, Brown S D, Fuchs P C. In vitro-selection of quinolone-resistant staphylococcal mutants by single exposure to ciprofloxacin or trovafloxacin (CP-99,219) J Antimicrob Chemother. 1996;38:324–327. doi: 10.1093/jac/38.2.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blatter M, Entenza J, Moreillon P, Glauser M P. Program and abstracts of the 33rd Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1993. Parenteral sparfloxacin compared to vancomycin in the treatment of experimental endocarditis due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, abstr. 150; p. 147. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blouin R A, Bauer L A, Miller D D, Record K E, Griffen W O. Vancomycin pharmacokinetics in normal and morbidly obese subjects. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1982;21:575–580. doi: 10.1128/aac.21.4.575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blum M D, Graham D J, McCloskey C A. Temafloxacin syndrome: review of 95 cases. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;18:946–950. doi: 10.1093/clinids/18.6.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borner K, Höffken G, Lode H, Koeppe P, Prinzing C, Glatzel P, Wiley R, Olschewski P, Sievers B, Reinitz D. Pharmacokinetics of ciprofloxacin in healthy volunteers after oral and intravenous administration. Eur J Clin Microbiol. 1986;5:179–186. doi: 10.1007/BF02013983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bouvet A, Cremieux A C, Contrepois A, Vallois J M, Lamesch C, Carbon C. Comparison of penicillin and vancomycin, individually and in combination with gentamicin and amikacin, in the treatment of experimental endocarditis induced by nutritionally variant streptococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1985;28:607–611. doi: 10.1128/aac.28.5.607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cars O, Ögren S. A microtechnique for the determination of antibiotics in muscle. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1981;8:39–48. doi: 10.1093/jac/8.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Child J, Andrews J, Boswell F, Brenwald N, Wise R. The in-vitro activity of CP-99,219, a new naphthyridone antimicrobial agent: a comparison with fluoroquinolone agents. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1995;35:869–876. doi: 10.1093/jac/35.6.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Craig W A, Suh B. Protein binding and the antimicrobial effects: methods for the determination of protein binding. In: Lorian V, editor. Antibiotics in laboratory medicine. 3rd ed. Baltimore, Md: The Williams & Wilkins Co.; 1991. pp. 367–402. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crémieux A C, Saleh-Mghir A, Vallois J M, Mazière B, Ottaviani M, Pocidalo J J, Carbon C. Program and abstracts of the 31st Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1991. Pattern of diffusion of three quinolones throughout infected cardiac vegetations studied by autoradiography, abstr. 357; p. 158. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Domagala J M. Structure-activity and structure-side-effect relationships for the quinolone antibacterials. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1994;33:685–706. doi: 10.1093/jac/33.4.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dürack D T, Beeson P B, Petersdorf R G. Experimental endocarditis. III. Production and progress of the disease in rabbits. Br J Exp Pathol. 1973;54:142–150. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Entenza J M, Blatter M, Glauser M P, Moreillon P. Parenteral sparfloxacin compared with ceftriaxone in treatment of experimental endocarditis due to penicillin-susceptible and -resistant streptococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:2683–2688. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.12.2683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Entenza J M, Fluckiger U, Glauser M P, Moreillon P. Antibiotic treatment of experimental endocarditis due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:100–109. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.1.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Entenza J M, Vouillamoz J, Glauser M P, Moreillon P. Levofloxacin versus ciprofloxacin, flucloxacillin, or vancomycin for treatment of experimental endocarditis due to methicillin-susceptible or -resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1662–1667. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.8.1662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flückiger U, Francioli P, Blaser J, Glauser M P, Moreillon P. Role of amoxicillin serum levels for successful prophylaxis of experimental endocarditis due to tolerant streptococci. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:1397–1400. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.6.1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Girard A E, Girard D, Gootz T D, Faiella J A, Cimochowski C R. In vivo efficacy of trovafloxacin (CP-99,219), a new quinolone with extended activities against gram-positive pathogens, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Bacteroides fragilis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:2210–2216. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.10.2210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gootz T D, Zaniewski R, Haskell S, Schmieder B, Tankovic J, Girard D, Courvalin P, Polzer R J. Activity of the new fluoroquinolone trovafloxacin (CP-99,219) against DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV mutants of Streptococcus pneumoniae selected in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2691–2697. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.12.2691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heraief E, Glauser M P, Freedman L. Natural history of aortic valve endocarditis in rats. Infect Immun. 1982;37:127–131. doi: 10.1128/iai.37.1.127-131.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones R N. Preliminary interpretative criteria for in vitro susceptibility testing of CP-99219 by dilution and disk diffusion methods. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1994;20:167–170. doi: 10.1016/0732-8893(94)90112-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaatz G W, Barriere S L, Schaberg D R, Fekety R. The emergence of resistance to ciprofloxacin during therapy of experimental methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1987;20:753–758. doi: 10.1093/jac/20.5.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaatz G W, Seo S M, Aeschlimann J R, Houlihan H H, Mercier R C, Rybak M J. Efficacy of trovafloxacin against experimental Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:254–256. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.2.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Naora K, Katagiri Y, Ichikawa N, Hayashibara M, Iwamoto K. A possible reduction of the renal clearance of ciprofloxacin by fenbufen in rats. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1990;42:704–707. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1990.tb06563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. Approved standard M7-A3. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Norrby S R. Treatment of urinary tract infections with fluoroquinolone antibacterial agents. In: Wolfson J S, Hooper D C, editors. Quinolone antimicrobial agents. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1989. pp. 107–123. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patel I H, Chen S, Parsonnet M, Hackman M R, Brooks M A, Konikoff J, Kaplan S A. Pharmacokinetics of ceftriaxone in humans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1981;20:634–641. doi: 10.1128/aac.20.5.634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Piddock L J. New quinolones and gram-positive bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:163–169. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.2.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Piper K E, Rouse M S, Patel R, Wilson W R, Steckelberg J M. Program and abstracts of the 37th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1997. Trovafloxacin treatment of viridans streptococcal experimental endocarditis, abstr. B-20; p. 30. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rouse M S, Piper K E, Patel R, Wilson W R, Steckelberg J M. Program and abstracts of the 37th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1997. In vitro and in vivo activity of trovafloxacin against methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus experimental endocarditis, abstr. B-26; p. 31. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stein, G. E. 1996. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of newer fluoroquinolones. Clin. Infect. Dis. 23(Suppl. 1):S19–S24. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Stoeckel K, McNamara J, Brandt R, Plozza-Nottebrock H, Ziegler W H. The effects of concentration-dependent plasma protein binding on the pharmacokinetics of ceftriaxone (Ro 13-9904), a new parenteral cephalosporin. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;29:650–657. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1981.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Teng R, Girard D, Gootz T D, Foulds G, Liston T E. Pharmacokinetics of trovafloxacin (CP-29,219), a new quinolone, in rats, dogs, and monkeys. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;40:561–566. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.3.561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wise R, Mortiboy D, Child J, Andrews J M. Pharmacokinetics and penetration into inflammatory fluid of trovafloxacin (CP-99,219) Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:47–49. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.1.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]