Abstract

The activities of HMR 3647, HMR 3004, erythromycin, clarithromycin, and levofloxacin for 97 Legionella spp. isolates were determined by microbroth dilution susceptibility testing. Growth inhibition of two Legionella pneumophila strains grown in guinea pig alveolar macrophages was also determined. The concentrations required to inhibit 50% of strains tested were 0.06, 0.02, 0.25, 0.03, and 0.02 μg/ml for HMR 3647, HMR 3004, erythromycin, clarithromycin, and levofloxacin, respectively. BYEα broth did not significantly inhibit the activities of the drugs tested, as judged by the susceptibility of the control Staphylococcus aureus strain; however, when Escherichia coli was used as the test strain, levofloxacin activity tested in BYEα broth was fourfold lower. HMR 3647, HMR 3004, erythromycin, and clarithromycin (0.25 and 1 μg/ml) reduced bacterial counts of two L. pneumophila strains grown in guinea pig alveolar macrophages by 0.5 to 1 log10, but regrowth occurred over a 2-day period. HMR 3647, erythromycin, and clarithromycin appeared to have equivalent intracellular activities which were solely static in nature. HMR 3004 was more active than all drugs tested except levofloxacin. In contrast, levofloxacin (1 μg/ml) was bactericidal against intracellular L. pneumophila and significantly more active than the other drugs tested. Therapy studies with HMR 3647 and erythromycin were performed in guinea pigs with L. pneumophila pneumonia. When HMR 3647 was given (10 mg/kg of body weight) by the intraperitoneal route to infected guinea pigs, mean peak plasma levels were 1.4 μg/ml at 0.5 h and 1.0 μg/ml at 1 h postinjection. The terminal half-life phase of elimination from plasma was 1.4 h. All 16 L. pneumophila-infected guinea pigs treated with HMR 3647 (10 mg/kg/dose given intraperitoneally once daily) for 5 days survived for 9 days after antimicrobial therapy, as did all 16 guinea pigs treated with the same dose of HMR 3647 given twice daily. Fourteen of 16 erythromycin-treated (30 mg/kg/dose given intraperitoneally twice daily) animals survived, whereas 0 of 12 animals treated with saline survived. HMR 3647 is effective against L. pneumophila in vitro, in infected macrophages, and in a guinea pig model of Legionnaires’ disease. HMR 3647 given once daily should be evaluated as a treatment for Legionnaires’ disease in humans.

HMR 3647 (RU 6647) and HMR 3004 (RU 004 and RU 64004) are novel macrolide compounds in the ketolide class. Ketolides are semisynthetic derivatives of erythromycin A which differ from erythromycin A by substitution of a 3-keto group for l-cladinose. Both HMR 3004 and HMR 3647 have a C11-C12 side chain. HMR 3004 has a C11-C12 carbazate on which a quinoline group is attached through a propyl chain and has been withdrawn from clinical development. In contrast, HMR 3647 has a carbamate group on which amidazolyl and pyridyl moieties are fixed through a propyl chain (1, 2, 6). HMR 3647 has potent activity against many gram-positive bacteria, including erythromycin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae. It is also known to be active against Haemophilus influenzae, many anaerobic bacteria, and Toxoplasma gondii (3, 22, 26) and to accumulate in polymorphonuclear neutrophils and macrophages in a nonsaturable fashion (23, 33). HMR 3004 is also known to have excellent activity against the same bacteria and to accumulate within human polymorphonuclear neutrophils (1–4, 18, 19, 22, 26, 31, 32). HMR 3004 has been reported to be active against Legionella bacteria in vitro (5). This study was designed to determine the in vitro activities of HMR 3647 and HMR 3004 against a large number of Legionella spp. bacteria as well as the in vivo activity of HMR 3647 for the treatment of a guinea pig model of Legionnaires’ disease. We demonstrate that HMR 3647 is at least as active as erythromycin against Legionella spp. bacteria in vitro, in Legionella pneumophila-infected alveolar macrophages, and in a guinea pig model of L. pneumophila pneumonia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

All legionellae studied were low-passage clinical isolates, if possible, and were isolated by us or obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Table 1). Included were all known serogroups of each Legionella species. Among the 46 L. pneumophila strains tested were 24 strains belonging to serogroup 1. Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213 and Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 were used as control organisms for susceptibility testing. To obtain inocula for susceptibility testing, legionellae were grown on MOPS (morpholinepropanesulfonic acid)-buffered charcoal yeast extract medium supplemented with 0.1% α-ketoglutarate that was made in our laboratory (BCYEα) and nonlegionellae were grown on commercial tryptic soy agar containing 5% sheep blood (13). All media were incubated at 35°C in humidified air for 24 to 48 h, depending on organism and growth rate.

TABLE 1.

Broth dilution MICs (μg/ml) for 46 L. pneumophila strainsa

| Measureb | HMR 3647 | HMR 3004 | Erythro-mycin | Clarithro-mycin | Levo-floxacin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 0.054 | 0.017 | 0.186 | 0.035 | 0.019 |

| MIC50 | 0.032 | 0.008 | 0.125 | 0.032 | 0.016 |

| MIC90 | 0.125 | 0.032 | 0.500 | 0.046 | 0.032 |

| Minimum | 0.016 | 0.008 | 0.060 | 0.016 | 0.016 |

| Maximum | 0.344 | 0.063 | 1.0 | 0.125 | 0.032 |

All data are geometric means.

MIC50, MIC at which 50% of the isolates are inhibited; MIC90, MIC at which 90% of the isolates are inhibited.

Antimicrobial agents.

Standard powders of HMR 3647, HMR 3004, and levofloxacin were obtained from Hoechst Marion Roussel, Romainville, France. Clarithromycin and erythromycin standard powders were obtained from Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, Ill. Both ketolide compounds were solubilized by acidification in glacial acetic acid (13 mM final concentration) and then diluted in sterile water for injection, USP. Levofloxacin standard powder was dissolved in sterile water for injection, USP. Erythromycin and clarithromycin standard powders were first dissolved in methanol and then diluted in water and phosphate buffer, respectively. Subsequent dilutions of the dissolved compounds were sufficient to remove the possibility of antimicrobial activity of the solubilizing agents. Erythromycin lactobionate (Abbott Laboratories) was used for the treatment study and dissolved in lactated Ringer’s solution for injection, USP, to a final concentration of 9.7 mg/ml. The HMR 3647 concentrations used for the pharmacokinetic and treatment studies were 2.9 and 3.2 mg/ml, respectively, and were made within 1 h before each injection.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

Microbroth dilution susceptibility testing was performed with n-(2-acetamido)-2-aminoethanesulfonic acid (ACES)-buffered yeast extract broth supplemented with 0.1% α-ketoglutarate (BYEα) (Legionella) or Mueller-Hinton broth (non-Legionella bacteria), with a final volume of 100 μl and a final bacterial concentration of 5 × 105 CFU/ml (15). The BYEα broth was made in our laboratory. All testing was done in duplicate, with average results calculated by the geometric mean calculation.

Growth inhibition in alveolar macrophages.

Guinea pig pulmonary alveolar macrophages were harvested and purified as described previously (11). The final concentration of macrophages was approximately 105 cells per well. Incubation conditions for all macrophage studies were 5% CO2 in air at 37°C.

L. pneumophila F889 and F2111 grown overnight on BCYEα agar were used to infect the macrophages. Approximately 104 bacteria were added to each well. Bacteria were incubated with macrophages for 1 h in a shaking incubator and then for 1 day in stationary culture, as described previously (11). One set of replicate wells was washed (500 μl) three times with tissue culture medium and then sonicated at low energy to release intracellular bacteria, which were quantified with BCYEα agar. Antimicrobial agents were then added to the washed nonsonicated wells; several wells with no antimicrobial agent added served as growth controls. The infected tissue cultures were then incubated for 2 days, after which supernatant samples were taken for quantitative culture. The antimicrobial agents were then removed by washing, and the experiment continued for 5 more days, with daily quantification of L. pneumophila in well supernatants. All experiments were carried out in duplicate or triplicate, and quantitative plating was done in duplicate. All wells were observed microscopically daily to detect macrophage infection and to roughly quantify numbers of macrophages in the wells. To exclude ketolide or clarithromycin macrophage toxicity, control wells, containing macrophages, tissue culture medium, and antimicrobial agents, but no bacteria, were set up. Prior studies have demonstrated no macrophage toxicity caused by levofloxacin or erythromycin (15). In this system there is no extracellular growth of L. pneumophila, so all increases in supernatant bacterial concentration are the result of intracellular growth.

Guinea pig pneumonia model.

Hartley strain male guinea pigs, ≈320 g in weight, were used for the pneumonia model, as previously described (10). Animals were observed for illness 1 week prior to infection; for the animals used in the treatment study, temperatures and weights were obtained during the preinfection period. The guinea pigs were infected with L. pneumophila serogroup 1, strain F889, administered by the intratracheal route. About 6 × 106 and 4 × 106 CFU were administered for the pharmacokinetic and treatment studies, respectively.

Pharmacokinetic study.

HMR 3647 plasma concentrations were measured in guinea pigs with L. pneumophila pneumonia as described previously (17). The drug was given in a single intraperitoneal dose (10 mg/kg of body weight, 2.9 mg/ml, 1.0-ml injection) to guinea pigs 1 day after infection; the mean guinea pig weight was 290 g. At timed intervals after drug injection, anesthetized animals in groups of two to three were exsanguinated by the removal of heart blood under direct vision. Heart blood was collected with a syringe and needle and then transferred immediately to heparinized tubes (Vacutainer; Becton Dickinson, Rutherford, N.J.). The heparinized blood was refrigerated immediately afterwards at 5°C. Within 2 to 12 h, the plasma was separated from the cellular blood components by centrifugation at 5,000 × g at 5°C for 10 min and then stored frozen at −70°C until it was shipped to France on dry ice. HMR 3647 is stable in plasma stored at −20°C for up to a year (8). The plasma specimens were analyzed for HMR 3647 by high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC). Negative controls included guinea pig plasma that had been collected from both L. pneumophila-infected and normal guinea pigs given identical anesthesia but no antimicrobial agent.

Drug assay.

HMR 3647 was quantified in plasma by HPLC (Hoechst Marion Roussel) (7). The bacteria in the plasma specimens were first inactivated by beta-irradiation of the frozen specimens at a dose of 50 kGy, which did not cause thawing of the samples. The samples were diluted 1:10 in normal human plasma, after which protein was precipitated by acetonitrile addition. The supernatant was dried under nitrogen gas and then dissolved in ammonium acetate (0.05 M), methanol/acetonitrile (29/24) in a 60:40 volume ratio. An internal standard (RU 66260) was added to the sample. The mobile phase was composed of ammonium acetate (0.05 M), methanol, and acetonitrile in a 52:29:24 volume ratio. HPLC was performed with a Purospher RP-18e 125 by 4.0 mm, 5-μm particle size column (Merck) with a mobile phase flow rate of 1 ml per min. HMR 3647 and the internal standard were detected with a fluorescence detector, with excitation and emission wavelengths of 263 and 460 nm, respectively. HMR 3647 was quantified by the peak height ratio method in comparison with the internal standard. A standardization curve for HMR 3647 contained in normal human plasma was constructed and was found to be linear over the concentration range of 0.005 to 1.000 μg/ml; this result correlates with a detectable range in the original samples of 0.05 to 10 μg/ml (because of 1:10 dilution). Positive controls tested included spiked human and guinea pig plasma. Several different tests of the extraction and detection efficiencies of the method were performed, including the use of spiked guinea pig plasma that was then irradiated. These quality control tests showed combined extraction and detection errors that ranged from −9 to +13%.

Animal treatment study.

Guinea pigs surviving surgery were randomized into four treatment groups 1 day after infection. Starting on that day, treatment was given once or twice daily (9 a.m. and 4 p.m.) for 5 days. All injections were given by the intraperitoneal route, in a 1.0-ml volume. One group of 16 animals received HMR 3647 (10 mg/kg) given once daily, another 16 animals received the same dose of HMR 3647 twice daily (total daily dose, 20 mg/kg). The third group of 16 animals received erythromycin twice daily (30 mg/kg/dose, or a total daily dose of 60 mg/kg), and the last group of 12 animals received normal saline. Dosing of the antimicrobial agents was designed to roughly emulate expected peak concentrations in serum in humans, as determined by pharmacokinetic studies in the animals and published and unpublished studies in humans, without regard to difference in drug clearances between the two different species (10, 28). Animal weights and temperatures were taken periodically during the 14-day postinfection observation period. Necropsies and quantitative lung cultures were performed on all animals that died. All animals surviving for 14 days postinfection were killed with pentobarbital. Necropsies, lung histopathology, and quantitative lung cultures were performed on the eight survivors from each treatment group with the lowest weights (10). The lower limit of detection of L. pneumophila in the lung was about 100 CFU/g. All animal studies were approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Statistical analysis.

All data analysis was performed with the use of either Prism (version 2.01) or InStat (version 2.01) software (GraphPad, San Diego, Calif.). Prism software was also used to calculate pharmacokinetic parameters. A P value of ≤0.05 was predefined as significant.

RESULTS

Broth dilution susceptibility.

All 99 Legionella strains tested by the agar dilution method were susceptible to low concentrations of all five antimicrobial agents tested (Tables 1 and 2). Both HMR 3004 and levofloxacin were equally and highly active against the bacteria tested and more active than the other drugs tested. HMR 3647 was more active than erythromycin but less active than clarithromycin, HMR 3004, and levofloxacin. Notably, of the Legionella species, L. pneumophila was the most susceptible to the antimicrobial agents tested except for HMR 3647 (Table 3). HMR 3647, HMR 3004, erythromycin, clarithromycin, and levofloxacin MICs for L. pneumophila F889 were 0.12, 0.03, 0.25, 0.04, and 0.02 μg/ml, respectively; respective values for strain F2111 were 0.18, 0.03, 0.50, 0.03, and 0.02 μg/ml. There were no significant differences in the MICs of all five drugs tested for the control S. aureus strain in BYEα and Mueller-Hinton broths. However, the levofloxacin MICs for E. coli were 2 twofold dilutions lower in Mueller-Hinton broth than in BYEα broth. Since the other agents tested are not active against E. coli, they could not be successfully tested with this organism.

TABLE 2.

Broth dilution MICs (μg/ml) for 51 non-L. pneumophila Legionella spp. strainsa

| Strain | No. of strains | HMR 3647 | HMR 3004 | Erythro-mycin | Clarithro-mycin | Levo-floxacin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L. adelaidensis | 1 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.125 | 0.012 | 0.008 |

| L. anisa | 1 | 0.063 | 0.032 | 0.500 | 0.032 | 0.032 |

| L. birminghamiensis | 1 | 0.125 | 0.063 | 0.500 | 0.125 | 0.032 |

| L. bozemanii | 4 | 0.059 | 0.030 | 0.256 | 0.024 | 0.023 |

| L. brunensis | 1 | 0.063 | 0.012 | 0.500 | 0.064 | 0.032 |

| L. cherrii | 1 | 0.032 | 0.032 | 0.250 | 0.032 | 0.016 |

| L. cincinnatiensis | 1 | 0.016 | 0.008 | 0.125 | 0.032 | 0.016 |

| L. dumofii | 3 | 0.125 | 0.063 | 0.143 | 0.025 | 0.025 |

| L. erythra | 1 | 0.250 | 0.125 | 0.750 | 0.125 | 0.016 |

| L. fairfieldensis | 1 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.032 | 0.012 | 0.125 |

| L. feeleii | 3 | 0.016 | 0.008 | 0.315 | 0.050 | 0.040 |

| L. geestiana | 1 | 0.063 | 0.032 | 0.250 | 0.064 | 0.004 |

| L. gormanii | 2 | 0.061 | 0.061 | 0.217 | 0.039 | 0.023 |

| L. gratiana | 1 | 0.063 | 0.032 | 0.500 | 0.032 | 0.064 |

| L. hackeliae | 1 | 0.063 | 0.008 | 0.500 | 0.060 | 0.125 |

| L. israelensis | 1 | 0.047 | 0.016 | 0.500 | 0.032 | 0.016 |

| L. jamestowniensis | 1 | 0.047 | 0.016 | 1.000 | 0.125 | 0.032 |

| L. jordanis | 1 | 0.250 | 0.032 | 1.000 | 0.125 | 0.032 |

| L. lansingensis | 1 | 0.032 | 0.004 | 0.375 | 0.048 | 0.125 |

| L. londiniensis | 1 | 0.032 | 0.016 | 0.188 | 0.032 | 0.008 |

| L. longbeachae | 4 | 0.165 | 0.116 | 0.297 | 0.087 | 0.027 |

| L. maceachernii | 1 | 0.063 | 0.024 | 0.500 | 0.060 | 0.016 |

| L. micdadei | 4 | 0.105 | 0.039 | 0.553 | 0.053 | 0.018 |

| L. moravica | 1 | 0.063 | 0.032 | 0.188 | 0.032 | 0.008 |

| L. nautarum | 1 | 0.008 | 0.004 | 0.125 | 0.032 | 0.064 |

| L. oakridgensis | 1 | 0.063 | 0.008 | 1.000 | 0.060 | 0.016 |

| L. quateirensis | 1 | 0.016 | 0.004 | 0.064 | 0.016 | 0.008 |

| L. quinlivanii | 1 | 0.063 | 0.024 | 0.188 | 0.032 | 0.032 |

| L. rubrilucens | 1 | 0.125 | 0.032 | 0.500 | 0.060 | 0.016 |

| L. sainthelensi | 1 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.250 | 0.046 | 0.032 |

| L. santicrucis | 1 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.250 | 0.046 | 0.012 |

| L. shakespearei | 1 | 0.063 | 0.032 | 1.000 | 0.064 | 0.125 |

| L. spiritensis | 1 | 0.063 | 0.012 | 0.250 | 0.032 | 0.016 |

| L. steigerwaltii | 1 | 0.016 | 0.008 | 0.375 | 0.016 | 0.024 |

| L. tucsonensis | 1 | 0.008 | 0.004 | 0.064 | 0.006 | 0.032 |

| L. wadsworthii | 1 | 0.032 | 0.008 | 0.250 | 0.032 | 0.008 |

| L. worsleiensis | 1 | 0.008 | 0.004 | 0.032 | 0.006 | 0.006 |

| Overall mean | 0.053 | 0.023 | 0.291 | 0.040 | 0.024 | |

| MIC50b | 0.062 | 0.032 | 0.50 | 0.032 | 0.032 | |

| MIC90c | 0.125 | 0.062 | 0.500 | 0.125 | 0.064 | |

| Minimum | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.032 | 0.004 | 0.004 | |

| Maximum | 0.250 | 0.125 | 1.0 | 0.125 | 0.125 |

All values represent geometric means of duplicate determinations; geometric means are also used to calculate mean values for results of multiple strains of a single species.

MIC50, MIC at which 50% of the strains are inhibited.

MIC90, MIC at which 90% of the strains are inhibited.

TABLE 3.

Proportion of Legionella species other than L. pneumophila that were inhibited by MICs less than the MIC90s (μg/ml) of the five antimicrobial agents tested

| Drug | MIC90a | No. of strains susceptible to a MIC < MIC90/total no. tested

|

P for Fisher’s exact test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L. pneumophila | Non-L. pneumophila | |||

| HMR 3647 | 0.125 | 37/46 | 37/51 | 0.47 |

| HMR 3004 | 0.062 | 44/46 | 35/51 | 0.0006 |

| Erythromycin | 0.50 | 39/46 | 24/51 | 0.0001 |

| Clarithromycin | 0.062 | 44/46 | 33/51 | 0.0001 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.032 | 35/46 | 28/51 | 0.03 |

MIC90, MIC at which 90% of the strains are inhibited.

Antimicrobial inhibition of intracellular growth.

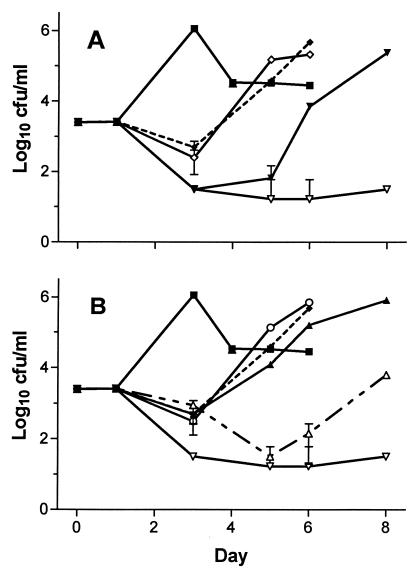

Both L. pneumophila serogroup 1 strains grown in guinea pig alveolar macrophages were significantly inhibited by all five drugs tested (Fig. 1). HMR 3647 was about as active as erythromycin and clarithromycin, while HMR 3004 and levofloxacin were significantly more inhibitory than the other drugs tested. Levofloxacin (0.25 μg/ml) was much more active than were HMR 3647, erythromycin, and clarithromycin (all 1.0 μg/ml). HMR 3004 (0.25 μg/ml) was about as active as the two macrolides and HMR 3647 (all 1.0 μg/ml). Levofloxacin was more active than HMR 3004 at an equivalent concentration. Thus, HMR 3004 and levofloxacin were the most active drugs tested in this assay, with levofloxacin the more active of the two. HMR 3647, erythromycin, and clarithromycin allowed rapid regrowth of L. pneumophila after drug washout, whereas HMR 3004 slowed regrowth. Levofloxacin did not allow any regrowth of F889 and significantly slowed the regrowth of F2111 by several days in comparison to erythromycin. No evidence of drug toxicity for macrophages was observed in drug-only control wells.

FIG. 1.

Growth of L. pneumophila serogroup 1 strain F2111 in guinea pig alveolar macrophages versus day of incubation after initiation of infection. Testing of strain F889 gave similar results. All points represent the means of triplicate wells counted in duplicate; error bars represent 95% CI which, unless shown, were smaller than the height of the symbol representing the mean. The lower limit of detection of the assay is log10 1.5 CFU/ml. (A) ■, no drug control; ◊, clarithromycin, 1 μg/ml; ⧫ (dotted line), HMR 3647, 1 μg/ml; ▾, levofloxacin, 0.25 μg/ml; ▿, levofloxacin, 1 μg/ml. (B) ■, no drug control; ○, erythromycin, 1 μg/ml; ⧫ (dotted line), HMR 3647, 1 μg/ml; ▴, HMR 3004, 0.25 μg/ml; ▵ (dotted line), HMR 3004, 1 μg/ml; ▿, levofloxacin, 1 μg/ml. Some identical data are reproduced in both figures for clarity. Results for HMR 3647, erythromycin, and clarithromycin (all at 0.25 μg/ml) gave results that were not significantly different than those for the higher concentration shown.

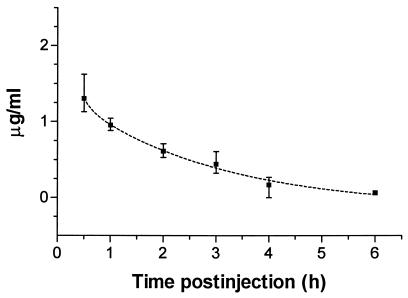

Pharmacokinetic study.

HMR 3647 administration (10 mg/kg) to L. pneumophila-infected guinea pigs gave the highest measured plasma concentrations of 1.4 and 1.0 μg/ml at 0.5 and 1.0 h, respectively (Fig. 2). A single-compartment exponential decay model gave the best fit for the data and was used to calculate half-life. The plasma terminal phase (β phase) half-life of elimination was calculated to be 1.4 h (95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.1 to 1.9 h), based on the single-compartment exponential decay model.

FIG. 2.

Mean HMR 3647 plasma concentrations in guinea pigs with L. pneumophila pneumonia. Animals were given a single 10-mg/kg dose administered by the intraperitoneal route at 0 h. Three animals were sampled at each time point, with the exception of the 6 h time point, at which two were sampled. Vertical bars represent the ranges for each time point. The dashed line shows the one-component exponential decay regression curve for the data; r2 = 0.91.

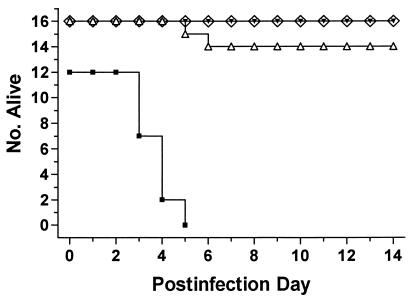

Therapy in guinea pigs.

All guinea pigs treated with HMR 3647 given once or twice daily (10 mg/kg/dose, n = 16 in each group) survived, as opposed to 100% deaths in the 12 guinea pigs receiving saline alone (Fig. 3). Fourteen of 16 guinea pigs given erythromycin treatment twice daily (30 mg/kg/dose) survived. The two erythromycin treatment group animals that died did so on days 5 and 6 postinfection and had necropsy, lung histology, and culture findings consistent with antibiotic-associated colitis, not with fatal pneumonia. Lung culture and necropsy results of all saline-treated animals were diagnostic of fatal L. pneumophila pneumonia; the mean concentration of L. pneumophila was log10 9.2 CFU/g of lung, with a range of log10 7.6 to 9.7 CFU/g. Five of the seven lungs examined from the erythromycin treatment group survivors were positive for L. pneumophila; these contained an average of log10 3.8 CFU/g, with a range of log10 3.1 to 4.2 CFU/g. Three of the eight lungs examined from the once daily HMR 3647 treatment group contained L. pneumophila; these contained log10 3.0, 3.4, and 3.4 CFU/g. Seven of eight lungs examined from the twice daily HMR 3647 treatment group contained L. pneumophila, with an average concentration of log10 3.6 CFU/g and a range of log10 2.7 to 4.2 CFU/g. There were no significant differences between the three active groups in the proportion of culture-negative survivors (P > 0.1 by chi-square test). Animal weights and temperatures were indistinguishable for all three active treatment groups (data not shown). No significant differences in lung histopathology were observed between those examined from the erythromycin and ketolide treatment groups or between those in the once and twice daily ketolide treatment groups.

FIG. 3.

Number of surviving guinea pigs with L. pneumophila pneumonia versus postinfection day. Animals were treated on days 1 to 5 postinfection with saline (■), HMR 3647 once daily (◊), HMR 3647 twice daily (▾), or erythromycin (▵).

DISCUSSION

Both HMR 3647 and HMR 3004 were more active than erythromycin against Legionella species in vitro, with HMR 3004 being the most active of the two ketolides tested. Because of the intracellular residence of L. pneumophila in human infection, antimicrobial agents used to treat Legionnaires’ disease need to be effective at limiting growth of the intracellular bacterium, which was demonstrated for both ketolide compounds. HMR 3647 given once or twice daily was quite effective for the treatment of a guinea pig model of L. pneumophila pneumonia, confirming its intracellular and extracellular activity.

Since the 14-OH metabolite of clarithromycin was not included in our in vitro testing, we may have underestimated the extracellular activity of clarithromycin (29). Also, the extracellular activity of one or more drugs may have been underestimated because of medium inhibition of drug activity, as evidenced by the differences in the E. coli susceptibility to levofloxacin depending on the test medium used. Greater resistance to antimicrobial agents of Legionella species other than L. pneumophila has not been reported. The large number and variety of non-L. pneumophila strains studied, greater than previously published, may account for this result. The greater apparent resistance of Legionella spp. other than L. pneumophila to several antimicrobial agents may account in part for the poorer outcome of patients with infections caused by such species (20).

HMR 3647 and clarithromycin were about as active as erythromycin for intracellular L. pneumophila. All three of these drugs were solely inhibitory for the intracellular bacterium, based on rapid regrowth of the bacterium after drug washout from the wells. Prior studies by us and others have shown that erythromycin is purely inhibitory in this and other macrophage systems, even at concentrations as high as 5 μg/ml (12, 25, 34). In contrast, HMR 3004 and levofloxacin were bactericidal against L. pneumophila in macrophages at concentrations of 1 μg/ml. Many fluoroquinolone drugs possess this bactericidal activity against intracellular L. pneumophila (11, 12, 17, 24, 27, 34). A prolonged postantibiotic effect, as observed in this study for levofloxacin and HMR 3004, has been regularly observed for fluoroquinolone antimicrobial agents tested by these methods (11, 17, 30).

The pharmacokinetic profile of plasma HMR 3647 in the guinea pig is different from that measured in humans (28). In addition, the plasma concentrations achieved in our animal treatment study are lower than those achieved in humans. The HMR 3647 serum half-life of terminal elimination (β phase) in humans is about 10 to 13 h, in contrast to the 1.4-h half-life measured in our study. Peak serum levels in humans after chronic daily oral administration of 800 mg are about 1.8 ± 1.1 μg/ml and occur about 2 h after administration. In contrast, the maximum plasma level we observed in the guinea pig was 1.3 μg/ml and occurred 0.5 h after intraperitoneal administration. The implication of these pharmacokinetic differences for HMR 3647 treatment of Legionnaires’ disease in humans is unclear but favors at least equivalent efficacy based on pharmacokinetic considerations alone.

HMR 3647 was about as effective as erythromycin for the treatment of experimental Legionnaires’ disease, despite the fact that it was given only once daily and at a low dose. There was no evidence that twice daily HMR 3647 dosing was more advantageous than once daily dosing by any outcome measure recorded—animal weight or temperature, survival, lung histology, or bacterial lung load. Neither HMR 3647 nor erythromycin treatments resulted in the lung sterilization seen with some very active fluoroquinolone antimicrobial agents or azithromycin (14–16, 21). Regardless, HMR 3647 was very effective in this animal model and has the potential to be as effective in humans, because the correlation between results for treatment of Legionnaires’ disease in an animal model and humans is excellent (9).

The apparently equivalent efficacy of once and twice daily dosing of HMR 3647 stresses the importance of the use of animal models in assessing the potential utility of antimicrobial agents for the treatment of Legionnaires’ disease. Such equivalence could not have been predicted based on knowledge of HMR 3647 animal pharmacokinetics, extracellular MICs, or intracellular infection studies. Once-daily dosing was effective, despite drug concentrations in plasma that were below the extracellular MIC for the infecting strain for ≥18 h. Drug persistence and activity in phagosomes may partially explain this result, as intracellular HMR 3647 is slowly cleared from cells, albeit completely within 2 to 3 h (23, 33). Another possible explanation is a greater postantibiotic effect in vivo than we measured in vitro. In addition, recovery from L. pneumophila pneumonia occurs in the guinea pig despite the persistence of the bacterium in the lung, which may also explain why nonbactericidal drugs can be effective in this disease. The reason more drug was not more effective is not known but might hinge on some sort of threshold effect of drug clearance or effectiveness.

Based on the results of our studies, HMR 3647 should be effective for the treatment of Legionnaires’ disease. This finding, plus the activity of the drug against penicillin-resistant pneumococci, may warrant human clinical trials of HMR 3647 for community-acquired pneumonia.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was funded by Hoechst Marion Roussel, Romainville, France.

Jianjun Ren, Thao Truoung, and Masao Tateyama provided expert technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agouridas C, Bonnefoy A, Chantot J F. Program and abstracts of the 35th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1995. In vitro antibacterial activity of RU 004, a novel ketolide highly active against respiratory pathogens, abstr. F158; p. 140. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agouridas C, Bonnefoy A, Chantot J F. Antibacterial activity of RU 64004 (HMR 3004), a novel ketolide derivative active against respiratory pathogens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2149–2158. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.10.2149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Araujo F G, Khan A A, Slifer T L, Bryskier A, Remington J S. The ketolide antibiotics HMR 3647 and HMR 3004 are active against Toxoplasma gondii in vitro and in murine models of infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2137–2140. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.10.2137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barry A L, Fuchs P C, Brown S D. In vitro activity of the new ketolide HMR 3004 compared to an azalide and macrolides against Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1997;16:767–769. doi: 10.1007/BF01709263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bornstein N, Behr H, Brun Y, Fleurette J. Program and abstracts of the 35th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1995. In vitro activity of RU 004 on Legionella species, abstr. F166; p. 142. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bryskier A, Agouridas C, Chantot J F. Ketolides: new semisynthetic 14-membered-ring macrolides. In: Zinner S H, Young L S, Acar J, Neu H C, editors. Expanding indications for the new macrolides, azalides, and streptogramins. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker, Inc.; 1997. pp. 39–50. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dupront A, Coussediere D, Lenfant B. Assay technique of HMR 3647 in human plasma. Romainville, France: Hoechst Marion Roussel; 1997. pp. 1–56. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dupront A, Lenfant B. Assay technique of HMR 3647 in human plasma. Addendum No. 5: 12 months stability of HMR 3647 in frozen plasma. Romainville, France: Hoechst Marion Roussel; 1997. pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edelstein P H. Antimicrobial chemotherapy for Legionnaires’ disease: a review. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:S265–S276. doi: 10.1093/clind/21.supplement_3.s265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edelstein P H, Calarco K, Yasui V K. Antimicrobial therapy of experimentally induced Legionnaires’ disease in guinea pigs. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1984;130:849–856. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1984.130.5.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edelstein P H, Edelstein M A C. WIN 57273 is bactericidal for Legionella pneumophila grown in alveolar macrophages. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33:2132–2136. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.12.2132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edelstein P H, Edelstein M A C. In vitro activity of azithromycin against clinical isolates of Legionella species. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:180–181. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.1.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edelstein P H, Edelstein M A C. Comparison of three buffers used in the formulation of buffered charcoal yeast extract medium. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:3329–3330. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.12.3329-3330.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edelstein P H, Edelstein M A C, Holzknecht B. In vitro activities of fleroxacin against clinical isolates of Legionella spp, its pharmacokinetics in guinea pigs, and use to treat guinea pigs with L. pneumophila pneumonia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:2387–2391. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.11.2387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edelstein P H, Edelstein M A C, Lehr K H, Ren J. In-vitro activity of levofloxacin against clinical isolates of Legionella spp., its pharmacokinetics in guinea pigs, and use in experimental Legionella pneumophila pneumonia. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1996;37:117–126. doi: 10.1093/jac/37.1.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edelstein P H, Edelstein M A C, Ren J J, Polzer R, Gladue R P. Activity of trovafloxacin (CP-99,219) against Legionella isolates: in vitro activity, intracellular accumulation and killing in macrophages, and pharmacokinetics and treatment of guinea pigs with L. pneumophila pneumonia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:314–319. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.2.314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edelstein P H, Edelstein M A C, Weidenfeld J, Dorr M B. In vitro activity of sparfloxacin (CI-978; AT-4140) for clinical Legionella isolates, pharmacokinetics in guinea pigs, and use to treat guinea pigs with L. pneumophila pneumonia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:2122–2127. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.11.2122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ednie L M, Spangler S K, Jacobs M R, Appelbaum P C. Antianaerobic activity of the ketolide RU 64004 compared to activities of four macrolides, five beta-lactams, clindamycin, and metronidazole. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1037–1041. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.5.1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ednie L M, Spangler S K, Jacobs M R, Appelbaum P C. Susceptibilities of 228 penicillin- and erythromycin-susceptible and -resistant pneumococci to RU 64004, a new ketolide, compared with susceptibilities to 16 other agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1033–1036. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.5.1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fang G-D, Yu V L, Vickers R M. Disease due to the Legionellaceae (other than Legionella pneumophila). Historical, microbiological, clinical, and epidemiological review. Medicine (Baltimore) 1989;68:116–132. doi: 10.1097/00005792-198903000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fitzgeorge, R. B., S. Lever, and A. Baskerville. 1993. A comparison of the efficacy of azithromycin and clarithromycin in oral therapy of experimental airborne Legionnaires’ disease. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 31(Suppl. E):171–176. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Frean J A, Arntzen L, Capper T, Bryskier A, Klugman K P. In vitro activities of 14 antibiotics against 100 human isolates of Yersinia pestis from a southern African plague focus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2646–2647. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.11.2646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.García I, Pascula A, Ballesta S, Perea E J. Program and abstracts of the 38th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1998. Uptake and intracellular activity of HMR 3647 in human phagocytic and nonphagocytic cells, abstr. A-112; p. 35. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Havlichek D, Saravolatz L, Pohlod D. Effect of quinolones and other antimicrobial agents on cell-associated Legionella pneumophila. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987;31:1529–1534. doi: 10.1128/aac.31.10.1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horwitz M A, Silverstein S C. Intracellular multiplication of Legionnaires’ disease bacteria (Legionella pneumophila) in human monocytes is reversibly inhibited by erythromycin and rifampin. J Clin Investig. 1983;71:15–26. doi: 10.1172/JCI110744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jamjian C, Biedenbach D J, Jones R N. In vitro evaluation of a novel ketolide antimicrobial agent, RU-64004. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:454–459. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.2.454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kitsukawa K, Hara J, Saito A. Inhibition of Legionella pneumophila in guinea pig peritoneal macrophages by new quinolone, macrolide and other antimicrobial agents. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1991;27:343–353. doi: 10.1093/jac/27.3.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lenfant B, Sultan E, Wable C, Pascual M H, Meyer B H. Program and abstracts of the 38th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1998. Pharmacokinetics of 800-mg once-daily oral dosing of the ketolide, HMR 3647, in healthy young volunteers, abstr. A-49; p. 16. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin S J, Pendland S L, Chen C, Schreckenberger P C, Danziger L H. In vitro activity of clarithromycin alone and in combination with ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin against Legionella spp.: enhanced effect by the addition of the metabolite 14-hydroxy clarithromycin. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1997;29:167–171. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(97)81806-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rajagopalan-Levasseur P, Dournon E, Dameron G, Vilde J-L, Pocidalo J-J. Comparative postantibacterial activities of pefloxacin, ciprofloxacin, and ofloxacin against intracellular multiplication of Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:1733–1738. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.9.1733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schulin T, Wennersten C B, Moellering R C J, Eliopoulos G M. In vitro activity of RU 64004, a new ketolide antibiotic, against gram-positive bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1196–1202. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.5.1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vazifeh D, Abdelghaffar H, Labro M T. Cellular accumulation of the new ketolide RU 64004 by human neutrophils: comparison with that of azithromycin and roxithromycin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2099–2107. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.10.2099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vazifeh D, Preira A, Bryskier A, Labro M T. Interactions between HMR 3647, a new ketolide, and human polymorphonuclear neutrophils. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1944–1951. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.8.1944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vildé J L, Dournon E, Rajagopalan P. Inhibition of Legionella pneumophila multiplication within human macrophages by antimicrobial agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1986;30:743–748. doi: 10.1128/aac.30.5.743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]