Abstract

In humans, ciliary dysfunction causes ciliopathies, which present as multiple organ defects, including developmental and sensory abnormalities. Sdccag8 is a centrosomal/basal body protein essential for proper cilia formation. Gene mutations in SDCCAG8 have been found in patients with ciliopathies manifesting a broad spectrum of symptoms, including hypogonadism. Among these mutations, several that are predicted to truncate the SDCCAG8 carboxyl (C) terminus are also associated with such symptoms; however, the underlying mechanisms are poorly understood. In the present study, we identified the Sdccag8 C-terminal region (Sdccag8-C) as a module that interacts with the ciliopathy proteins, Ick/Cilk1 and Mak, which were shown to be essential for the regulation of ciliary protein trafficking and cilia length in mammals in our previous studies. We found that Sdccag8-C is essential for Sdccag8 localization to centrosomes and cilia formation in cultured cells. We then generated a mouse mutant in which Sdccag8-C was truncated (Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice) using a CRISPR-mediated stop codon knock-in strategy. In Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice, we observed abnormalities in cilia formation and ciliopathy-like organ phenotypes, including cleft palate, polydactyly, retinal degeneration, and cystic kidney, which partially overlapped with those previously observed in Ick- and Mak-deficient mice. Furthermore, Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice exhibited a defect in spermatogenesis, which was a previously uncharacterized phenotype of Sdccag8 dysfunction. Together, these results shed light on the molecular and pathological mechanisms underlying ciliopathies observed in patients with SDCCAG8 mutations and may advance our understanding of protein–protein interaction networks involved in cilia development.

Keywords: cilia, CRISPR/cas, mouse, retina, kidney, spermatogenesis, serologically defined colon cancer antigen 8, intestinal cell kinase/ciliogenesis-associated kinase 1, male germ cell-associated kinase, sonic hedgehog

Abbreviations: AAV, adeno-associated virus; CRISPR, clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats; EGFP, enhanced green fluorescent protein; ERGs, electroretinograms; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; Ick, intestinal cell kinase; IFT, intraflagellar transport; Mak, male germ cell-associated kinase; MEFs, mouse embryonic fibroblasts; NPHP, nephronophthisis; ONL, outer nuclear layer; PFA, paraformaldehyde; RT-PCR, reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction; SDCCAG8, serologically defined colon cancer antigen 8; Sdccag8-C, Sdccag8 C-terminal region; Sdccag8-FL, full-length Sdccag8; shRNAs, short hairpin RNAs; Smo, Smoothened

Cilia are evolutionarily conserved microtubule-based organelles that extend from the basal bodies and are formed on the cell surface (1, 2). They are generally classified into two categories: motile cilia and primary cilia (3). Motile cilia are formed on specific epithelial cell types and cooperatively beat in wave-like patterns to generate fluid flow. Sperm flagella are an example of motile cilia which mainly function in cell locomotion. On the other hand, primary cilia are present in almost every cell type in vertebrates and act as cellular antennae to sense physical and biochemical extracellular signals. In humans, ciliary dysfunction causes diseases known as ciliopathies, which are characterized by a broad spectrum of pathologies, including polydactyly, craniofacial abnormalities, brain malformation, situs inversus, obesity, diabetes, retinal and renal degeneration, hearing loss, and infertility (4, 5).

Many ciliary proteins are known to play important roles in human physiology, signaling, and development (6). It was recently reported that there are at least 38 established ciliopathies with mutations in at least 247 genes (7). For example, Bardet–Biedl syndrome (BBS), which is an autosomal recessive ciliopathy that results in a plethora of developmental and multiorgan defects, is known to be caused by mutations in 22 identified pathogenic genes (8). In addition, mutations in more than 25 different pathogenic genes have been shown to be associated with nephronophthisis (NPHP), an autosomal recessive renal ciliopathy with additional features such as retinal defects, liver fibrosis, skeletal abnormalities, and brain developmental disorders (9). Although many gene mutations causing ciliopathies have been found in humans, the molecular and pathological mechanisms underlying ciliopathies are still not well understood.

Serologically defined colon cancer antigen 8 (SDCCAG8) was identified as a centrosome-associated tumor antigen protein and is also known as centrosomal colon cancer autoantigen protein, NPHP10, and BBS16 (10). Mutations in SDCCAG8 are associated with an NPHP-related ciliopathy, characterized by retinal and renal degeneration, cognitive defects, obesity, hypogonadism, hearing loss, recurrent respiratory infections, and infrequently clinodactyly (11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16). Several studies have reported that Sdccag8 is required for cilia formation and Hedgehog signaling (17, 18, 19). Sdccag8 knockout mice mostly died after birth with multiple organ defects, and Sdccag8 gene-trap mice exhibited retinal and renal degeneration (17, 20). It has also been reported that Sdccag8 is associated with the regulation of pericentriolar material recruitment (17). Several mutations in the human SDCCAG8 gene that are predicted to truncate the Sdccag8 carboxyl (C) terminus are associated with multiple organ defects, including retinal degeneration and cystic kidney (11, 12, 13); however, the underlying pathological mechanisms are poorly understood.

We and others have previously reported that intestinal cell kinase (Ick), also known as ciliogenesis-associated kinase 1, and male germ cell-associated kinase (Mak) play crucial roles in the regulation of cilia length and ciliary transport in mammals (21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26). Ick and Mak are serine-threonine kinases that belong to the mitogen-activating protein kinase family and show high homology, especially in their catalytic domains (27, 28, 29). Ick is ubiquitously expressed in various tissues, whereas Mak is predominantly expressed in the retina and testis (30). Several missense mutations in the human ICK gene have been reported to lead to endocrine-cerebro-osteodysplasia syndrome and short-rib polydactyly syndrome, lethal recessive ciliopathies with multiple developmental abnormalities, including cleft palate and cystic kidneys (31, 32, 33). Mutations in the human MAK gene also cause autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa (34, 35). In the current study, we found that Ick and Mak interact with the C-terminal region of Sdccag8 (Sdccag8-C) and investigated the role of Sdccag8-C in vitro and in vivo.

Results

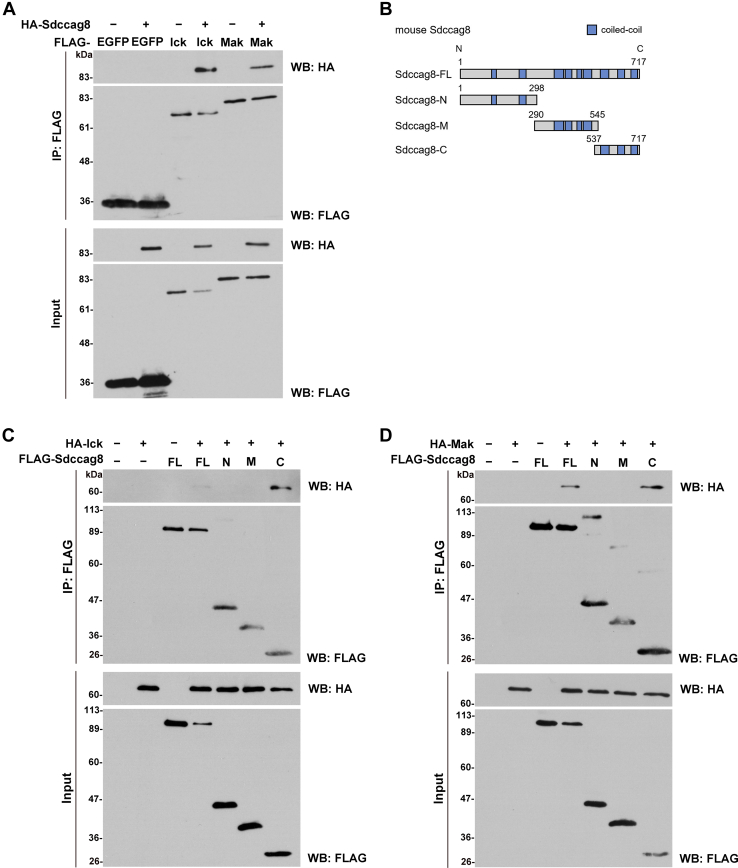

Ick and Mak interact with the C-terminal region of Sdccag8

To investigate the molecular mechanisms of cilia development and ciliopathies, we screened for proteins that interact with Ick protein using yeast two-hybrid screening and identified various proteins, including Sdccag8 (Table S1). Since this protein has previously been associated with ciliopathies with multiple organ defects as well as ICK, we focused on Sdccag8 in the present study. First, we confirmed the interaction between Ick and Sdccag8 by immunoprecipitation assay using HEK293T cells with an anti-FLAG antibody (Fig. 1A). To confirm the endogenous interaction between Ick and Sdccag8, we performed an immunoprecipitation assay using a HEK293T cell extract with an anti-SDCCAG8 antibody (Fig. S1). We observed the ICK band in immunoprecipitates with the anti-SDCCAG8 antibody by Western blot, suggesting the endogenous interaction between ICK and SDCCAG8. The immunoprecipitation assay also revealed an interaction between Mak and Sdccag8 (Fig. 1A). Human SDCCAG8 is a ciliary protein that consists of eight predicted coiled-coil motifs and can be divided into three regions: amino (N) terminal (1–294 aa), middle (286–541 aa), and C terminal (533–713 aa, SDCCAG8-C) (11). To determine which region of Sdccag8 interacts with Ick and Mak, we divided mouse Sdccag8 into three regions [N terminal (1–298 aa, Sdccag8-N), middle (290–545 aa, Sdccag8-M), and C terminal (537–717 aa, Sdccag8-C)] and examined their interaction with Ick and Mak by immunoprecipitation assays (Fig. 1B). Immunoprecipitation assays showed that both Ick and Mak interacted with the full-length Sdccag8 (Sdccag8-FL) and Sdccag8-C, but not Sdccag8-N or Sdccag8-M (Fig. 1, C and D). These results suggest that Ick and Mak interact with Sdccag8-C.

Figure 1.

Interaction of Sdccag8 with Ick and Mak.A, immunoprecipitation analysis of Sdccag8 and EGFP, Ick or Mak. Plasmids expressing FLAG-tagged EGFP, Ick or Mak, and HA-tagged Sdccag8 were co-transfected into HEK293T cells. The cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with an anti-FLAG antibody. Immunoprecipitated proteins were detected by Western blot analysis with anti-FLAG and anti-HA antibodies. B, schematic diagrams of mouse Sdccag8-FL, Sdccag8-N, Sdccag8-M, and Sdccag8-C. C and D, immunoprecipitation analysis of Sdccag8-FL, Sdccag8-N, Sdccag8-M, or Sdccag8-C and Ick (C) or Mak (D). The plasmids expressing FLAG-tagged Sdccag8-FL, Sdccag8-N, Sdccag8-M, or Sdccag8-C, and HA-tagged Ick or Mak were co-transfected into HEK293T cells. The cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with an anti-FLAG antibody. Immunoprecipitated proteins were detected by Western blot analysis with anti-FLAG and anti-HA antibodies. EGFP, enhanced green fluorescent protein; Ick, intestinal cell kinase; Mak, male germ cell-associated kinase.

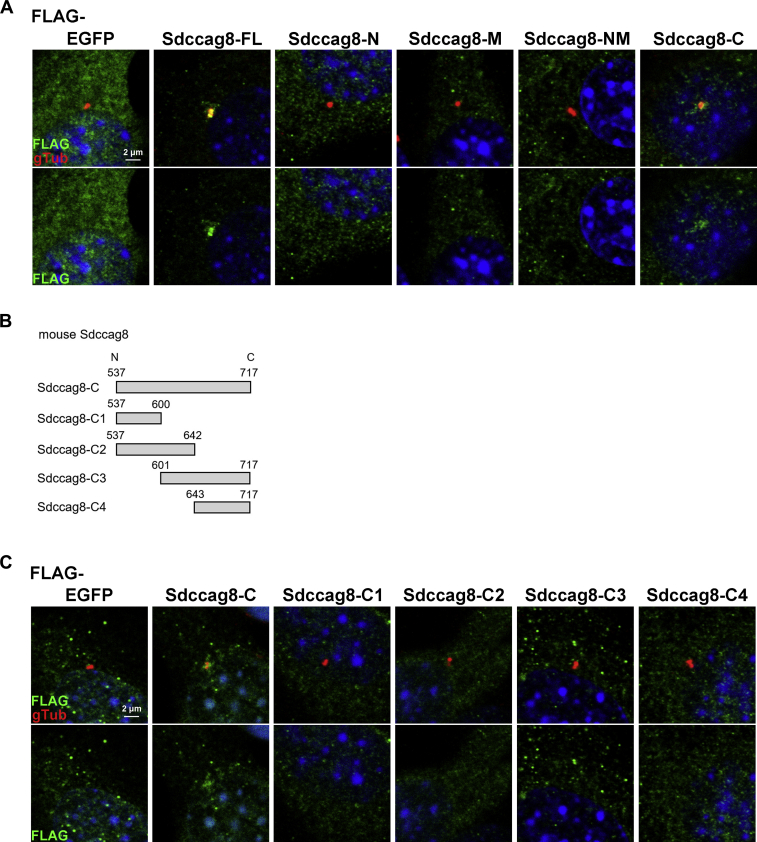

The C-terminal region is required for the localization of Sdccag8 to centrosomes

Since the Sdccag8 protein is known to localize to centrosomes and basal bodies (10, 11), we analyzed the role of Sdccag8-C in localizing to centrosomes. We transfected the plasmids expressing FLAG-tagged enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP), Sdccag8-FL, Sdccag8-N, Sdccag8-M, the N terminal to middle region of mouse Sdccag8 (1–545 aa, Sdccag8-NM), or Sdccag8-C into NIH-3T3 cells and compared their localization to centrosomes by immunostaining with antibodies against FLAG and γ-tubulin (a marker for centrosomes and basal bodies). We observed that Sdccag8-FL and Sdccag8-C localize to centrosomes in NIH-3T3 cells, although the signal intensity of Sdccag8-C at centrosomes was lower than that of Sdccag8-FL (Fig. 2A). In contrast, signals of Sdccag8-N, Sdccag8-M, and Sdccag8-NM were not detected at centrosomes. These results suggest that Sdccag8-C is required for localization to the basal bodies. To further analyze the localization of Sdccag8-C at basal bodies, we prepared the plasmids expressing a FLAG-tagged mouse Sdccag8-C1 (537–600 aa), Sdccag8-C2 (537–642 aa), Sdccag8-C3 (601–717 aa), or Sdccag8-C4 (643–717 aa), considering the evolutionary conservation of the amino acid sequences in vertebrate Sdccag8 proteins (Fig. 2B). We transfected plasmids expressing FLAG-tagged EGFP, Sdccag8-C, Sdccag8-C1, Sdccag8-C2, Sdccag8-C3, or Sdccag-C4 into NIH-3T3 cells and compared their localization to centrosomes. Unexpectedly, we did not observe signals corresponding Sdccag8-C1, Sdccag8-C2, Sdccag8-C3, and Sdccag8-C4 at centrosomes, whereas Sdccag8-C localized at centrosomes in NIH-3T3 cells (Fig. 2C). These results suggest that the entire Sdccag8-C (537–717 aa) comprises a functional unit that can localize to basal bodies.

Figure 2.

Roles of the C-terminal region on the localization of Sdccag8 to the centrosome in cultured cells.A, plasmids expressing a FLAG-tagged EGFP, Sdccag8-FL, Sdccag8-N, Sdccag8-M, Sdccag8-NM, or Sdccag8-C were transfected into NIH-3T3 cells. Cells were immunostained with anti-FLAG and anti-γ-tubulin (gTub, a marker for centrosomes and basal bodies) antibodies. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. B, schematic diagrams of mouse Sdccag8-C, Sdccag8-C1, Sdccag8-C2, Sdccag8-C3, and Sdccag8-C4. C, plasmids expressing a FLAG-tagged EGFP, Sdccag8-C, Sdccag8-C1, Sdccag8-C2, Sdccag8-C3, or Sdccag8-C4 were transfected into NIH-3T3 cells. Cells were immunostained with anti-FLAG and anti-γ-tubulin antibodies. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. EGFP, enhanced green fluorescent protein.

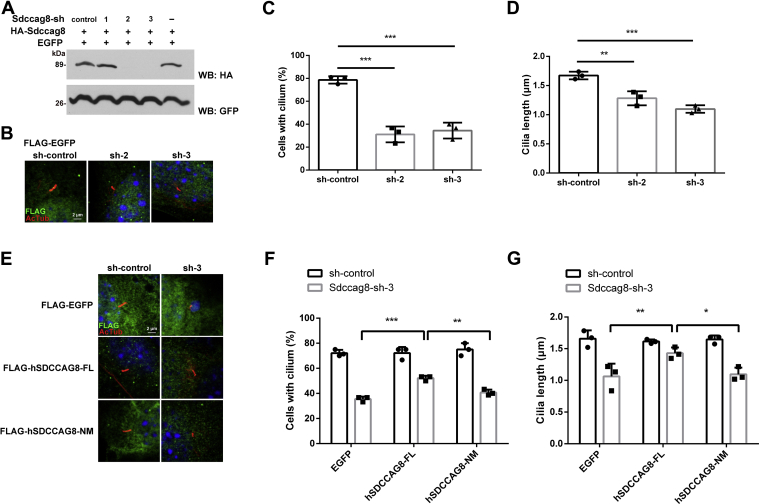

The C-terminal region of Sdccag8 is required for cilia formation in cultured cells

To investigate the roles of Sdccag8-C in cilia formation, we performed knockdown and rescue experiments using NIH-3T3 cells. We first constructed short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) to knockdown Sdccag8 and confirmed that Sdccag8-shRNA2 and Sdccag8-shRNA3 suppressed the Sdccag8 expression (Fig. 3A). We also confirmed that Sdccag8-shRNA2 and Sdccag8-shRNA3 suppressed the endogenous Sdccag8 expression in NIH-3T3 cells (Fig. S2). We transfected these constructs into NIH-3T3 cells and examined the cilia by immunostaining using anti-acetylated α-tubulin (a ciliary marker) and anti-FLAG antibodies. We observed that Sdccag8-shRNA2 and Sdccag8-shRNA3 significantly decreased the number of ciliated cells and cilia length (Fig. 3, B–D). Next, we prepared plasmids expressing a FLAG-tagged full-length human SDCCAG8 (1–713 aa, hSDCCAG8-FL) and the N-terminal to middle region of human SDCCAG8 (1–541 aa, hSDCCAG8-NM). We transfected the shRNA-control or Sdccag8-shRNA3 expression plasmids with plasmids expressing FLAG-tagged EGFP, hSDCCAG8-FL, or hSDCCAG8-NM into NIH-3T3 cells and examined the cilia by immunostaining using anti-acetylated α-tubulin and anti-FLAG antibodies. We found that the expression of hSDCCAG8-FL rescued the Sdccag8-shRNA–induced inhibition of cilia formation (Fig. 3, E–G). In contrast, the expression of hSDCCAG8-NM failed to rescue the Sdccag8-shRNA–induced inhibition of cilia formation. These results suggest that SDCCAG8-C is required for cilia formation.

Figure 3.

Roles of the C-terminal region of SDCCAG8 on cilia formation in cultured cells.A, inhibition efficacy of shRNA expression constructs for Sdccag8 knockdown. ShRNA-control, Sdccag8-shRNA1, Sdccag8-shRNA2, or Sdccag8-shRNA3 expression plasmids were co-transfected with plasmids expressing a HA-tagged Sdccag8 and a GFP into HEK293T cells. Western blot analysis was performed using anti-HA and anti-GFP antibodies. GFP was used as an internal transfection control. Sdccag8-shRNA2 and shRNA3 effectively suppressed Sdccag8 expression. B–D, ShRNA-control, Sdccag8-shRNA2, or Sdccag8-shRNA3 expression plasmids were co-transfected with a plasmid expressing FLAG-tagged EGFP into NIH-3T3 cells. Cells were immunostained with anti-FLAG and anti-acetylated α-tubulin (Actub, a ciliary marker) antibodies. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (B). The numbers (C) and length (D) of the cilia stained with an antibody against acetylated α-tubulin were measured. Sdccag8-shRNA2 and Sdccag8-shRNA3 inhibited ciliary formation. For the subsequent rescue experiment, Sdccag8-shRNA3 was used. Error bars show SD. ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001 (one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons test), n = 3. E–G, ShRNA-control or Sdccag8-shRNA3 expression plasmids were co-transfected into NIH-3T3 cells with plasmids expressing FLAG-tagged EGFP, hSDCCAG8-FL, or hSDCCAG8-NM. Cells were immunostained with anti-FLAG and anti-acetylated α-tubulin antibodies. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (E). The numbers (F) and length (G) of the cilia stained with an antibody against acetylated α-tubulin were measured. Error bars show SD. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001 (two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons test), n = 3. EGFP, enhanced green fluorescent protein.

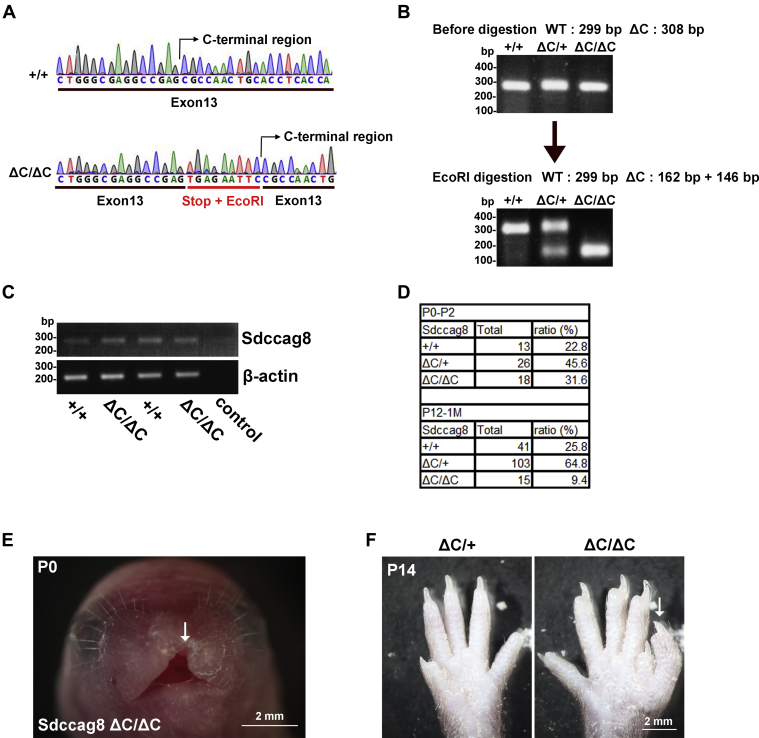

Sdccag8 Arg537Stop knock-in mice show partial postnatal lethality and skeletal defects

Next, to examine the in vivo roles of Sdccag8-C, we generated Sdccag8 Arg537Stop knock-in (Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC) mice using the clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-Cas9 system. A stop codon and an EcoRI restriction site were knocked-in before the DNA sequence encoding Sdccag8-C (537–717 aa) in Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice (Fig. 4A). The EcoRI restriction site was inserted to facilitate the detection of the stop codon insertion (Fig. 4B). We performed reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis and confirmed that the expression levels of Sdccag8 mRNA were comparable between Sdccag8+/+ and Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice (Fig. 4C), suggesting that Sdccag8 mRNA is not degraded by nonsense-mediated decay in Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice.

Figure 4.

Generation and characterization of Sdccag8ΔC/ΔCmice.A, DNA sequences encoding around the Sdccag8 C-terminal region of Sdccag8+/+ and Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice. The Arg537Stop codon and EcoRI restriction site were underlined in red. The Arg537Stop codon and EcoRI restriction site were knocked-in before Sdccag8-C (537–717 aa) in Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice. B, PCR analysis of Sdccag8 from tail tips of Sdccag8+/+, Sdccag8ΔC/+, and Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice. The PCR products from Sdccag8ΔC/+ and Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice were able to be digested by EcoRI. C, RT-PCR analysis of Sdccag8 (Exons 11–13) and β-actin in MEFs from Sdccag8+/+ and Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice. β-actin was used as a loading control. Sdccag8 mRNA was detected in Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice. D, genotype distribution of the offspring from Sdccag8ΔC/+ parents at P0-2 and P12-1 month old. E and F, skeletal defects in Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice. Gross appearance of the Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC face at P0 (E) and digits (F) in Sdccag8ΔC/+ and Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice at P14. Arrows indicate the cleft palate (E) and polydactyly (F) in Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice. MEF, mouse embryonic fibroblast.

To examine the survival of Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice, we measured the genotype distribution of the offspring from Sdccag8ΔC/+ parents at the neonatal stages from postnatal day 0 (P0) to P2 and at postnatal stages from P12 to 1 month old. The survival ratio of Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice was approximately 2.5 times lower than that of Sdccag8+/+ mice from P12 to 1 month old, whereas Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice were present at the expected Mendelian ratios at neonatal stages (Fig. 4D). This result suggests that Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice exhibit partial postnatal lethality, but not embryonic lethality. In addition, we found that one Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mouse showed a cleft palate (Fig. 4E). We also found that several Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice exhibited polydactyly (Fig. 4F). These observations suggest that Sdccag8-C is required for proper skeletal development.

The C-terminal region of Sdccag8 is essential for cilia formation and function in embryonic fibroblasts

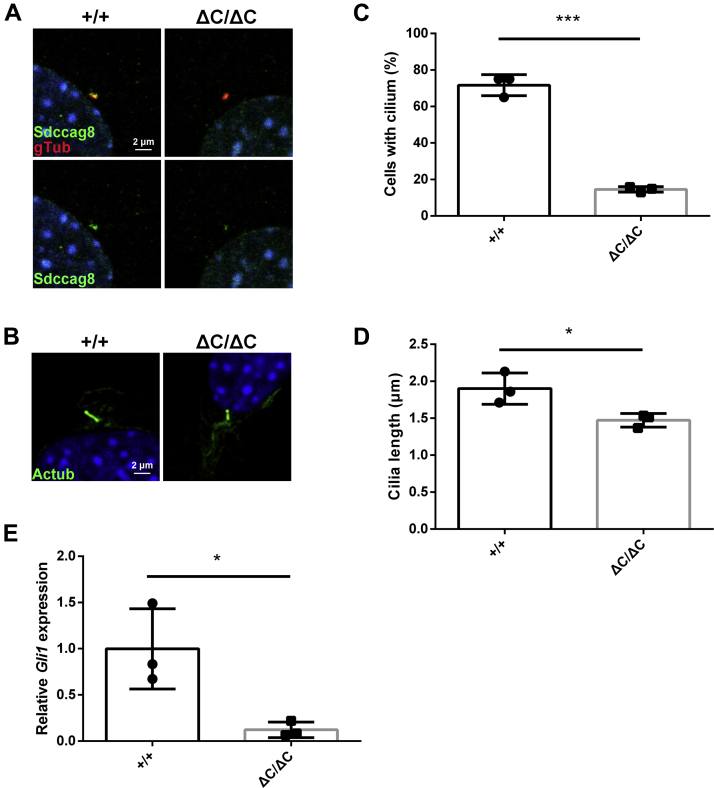

Since Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice exhibited ciliopathy-like phenotypes such as cleft palate and polydactyly, we examined cilia formation and function in Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice. To investigate the role of Sdccag8-C in cilia formation and function, we analyzed cilia in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) from Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC embryos. We first immunostained Sdccag8 in Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC MEFs with an antibody against γ-tubulin. We observed that Sdccag8 signals at centrosomes in Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC MEFs were lower than those in Sdccag8+/+ MEFs (Figs. 5A and S3A), suggesting a weak localization of Sdccag8 at centrosomes in Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC MEFs. We next performed immunofluorescent analyses of MEFs using the antibody against acetylated α-tubulin and found that the number of ciliated cells and cilia length significantly decreased in Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC MEFs compared with that in Sdccag8+/+ MEFs (Fig. 5, B–D). To examine whether the loss of Sdccag8-C affects intraflagellar transport (IFT), the bidirectional protein transport system in cilia, we immunostained IFT88 (a component of IFT complex) in the cilia of Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC MEFs. We observed no obvious difference in the ciliary localization of IFT88 between Sdccag8+/+ and Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC MEFs (Fig. S3B). Cilia are known to play important roles in Hedgehog signal transduction (36). To examine whether the loss of Sdccag8-C affects Hedgehog signaling, we first observed Hedgehog signal-dependent ciliary localization of Smoothened (Smo), a Hedgehog signaling component, in Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC MEFs with or without treatment of a Smo agonist (SAG) (37). Activation of the Hedgehog pathway with SAG treatment induces ciliary localization of Smo (38). We observed no significant difference in the Smo localization to cilia between Sdccag8+/+ and Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC MEFs (Fig. S3, C and D). We next examined the expression level of Gli family zinc finger 1 (Gli1), a downstream target gene of the Hedgehog signaling cascade, in Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC MEFs by quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis. The qRT-PCR analysis showed that Gli1 expression significantly decreased in Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC MEFs compared with that in Sdccag8+/+ MEFs in the presence of the Hedgehog pathway activation signals (Fig. 5E). These results suggest that Sdccag8-C plays an important role in cilia formation and the Hedgehog signal transduction.

Figure 5.

Ciliary defects in Sdccag8ΔC/ΔCMEFs.A, immunofluorescent analysis of MEFs from Sdccag8+/+ and Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice using anti-Sdccag8 and anti-γ-tubulin antibodies. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. B–D, immunofluorescent analysis of MEFs from Sdccag8+/+ and Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice using an anti-acetylated α-tubulin antibody. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (B). The numbers (C) and length (D) of the cilia stained with an antibody against acetylated α-tubulin were measured. Error bars show SD. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗p < 0.001 (unpaired t test), n = 3 mice per genotype. E, qRT-PCR analysis of Gli1 mRNA level in SAG-treated MEFs from Sdccag8+/+ and Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice. Shh signal-dependent expression of Gli1 was defective in the Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC MEF. Error bars show SD. ∗p < 0.05, (unpaired t test), n = 3 mice per genotype. MEF, mouse embryonic fibroblast; qRT-PCR, quantitative RT-PCR.

Deficiency of the C-terminal region of Sdccag8 causes retinal degeneration

To examine Sdccag8 expression in various tissues, we performed RT-PCR analysis using mouse tissue cDNAs at 4 weeks old. RT-PCR analysis showed that Sdccag8 is ubiquitously expressed in various tissues, including the retina, kidney, and testis (Fig. S4A). To examine Sdccag8 expression in the retina, we performed in situ hybridization using retinal sections at P9. We observed that Sdccag8 transcripts were broadly expressed in the retina (Fig. S4B).

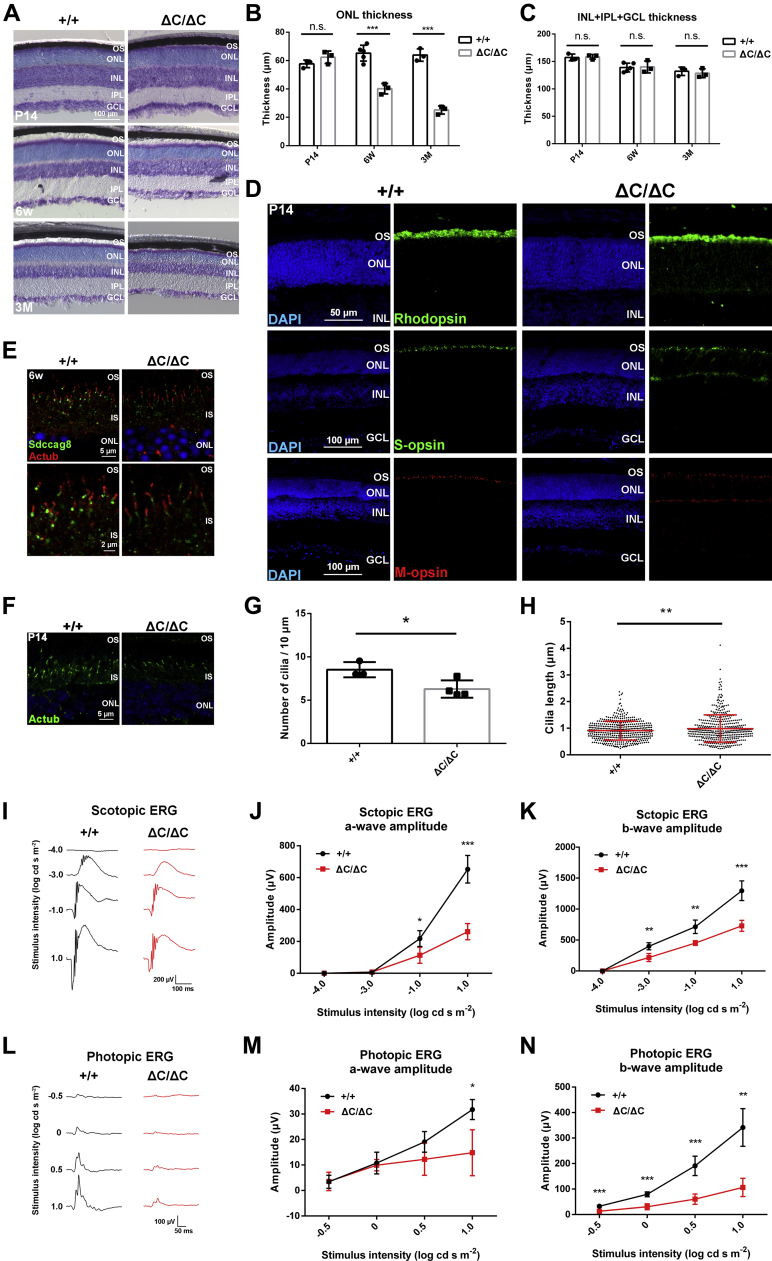

To investigate the roles of Sdccag8-C in the retina, we performed histological analyses using retinal sections from Sdccag8+/+ and Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice. Toluidine blue staining showed that there was no significant difference between the Sdccag8+/+ and Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC retinas at P14; however, the outer nuclear layer (ONL) thickness in the Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC retina progressively decreased after 6 weeks (Fig. 6, A and B). In contrast, we observed no significant difference in the thickness of the other layers between the Sdccag8+/+ and Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC retinas (Fig. 6C). These results indicate that Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice exhibit progressive photoreceptor degeneration. To observe outer segments in the Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC retina, we performed immunofluorescent analyses of retinal sections using antibodies against Rhodopsin (a marker for rod outer segments), S-opsin (a marker for S-cone outer segments), and M-opsin (a marker for M-cone outer segments). Disorganized rod and cone outer segments and mislocalization of Rhodopsin, S-opsin, and M-opsin in the ONL were observed in the Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC retina at P14 and 6 weeks (Figs. 6D and S4C). We also observed the mislocalization of Rhodopsin in the ONL of the retina injected with adeno-associated virus (AAV)-Sdccag8-shRNA3 (Fig. S4D). To analyze the subcellular localization of Sdccag8, we immunostained Sdccag8 and γ-tubulin in the photoreceptors of the Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC retina and found that Sdccag8 signals at basal bodies in Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC photoreceptors were lower than those in Sdccag8+/+ photoreceptors (Figs. 6E and S4E), suggesting the weak localization of Sdccag8 at basal bodies in Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC photoreceptors. Next, we immunostained acetylated α-tubulin and observed that the number of photoreceptor cilia significantly decreased in the Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC retina compared with that in the Sdccag8+/+ retina (Fig. 6, F and G). Unexpectedly, we found that the number of elongated photoreceptor cilia significantly increased in the Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC retina compared with that in the Sdccag8+/+ retina (Figs. 6H and S4F). On the other hand, we immunostained IFT88 in photoreceptor cilia of the Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC retina and observed no significant difference in the ciliary localization of IFT88 between Sdccag8+/+ and Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC photoreceptors (Fig. S4, G and H). Taken together, these results suggest that Sdccag8-C is essential for photoreceptor cilia formation.

Figure 6.

Photoreceptor degeneration in the Sdccag8ΔC/ΔCretina.A–C, toluidine blue staining of retinal sections from Sdccag8+/+ and Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice at P14, 6 weeks, and 3 months (A). The ONL (B) and INL + IPL + GCL (C) thicknesses were measured. The ONL thickness progressively decreased in the Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC retina. Error bars show SD. ∗∗∗p < 0.001, n.s., not significant (unpaired t test). Sdccag8+/+ at P14 and 3 months, n = 3 mice; Sdccag8+/+ at 6 weeks, n = 5 mice; Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC at P14, 6 weeks, and 3 months, n = 3 mice. D, immunofluorescent analysis of retinal sections from Sdccag8+/+ and Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice at P14 using antibodies as follows: anti-Rhodopsin (a marker for rod outer segments), anti-S-opsin (a marker for S-cone outer segments), and anti-M-opsin (a marker for M-cone outer segments). Nuclei were stained with DAPI. E, immunofluorescent analysis of retinal sections from Sdccag8+/+ and Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice at 6 weeks using anti-Sdccag8 and anti-acetylated α-tubulin antibodies. The lower panels indicate higher magnification views of the upper panels. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. F–H, immunofluorescent analysis of retinal sections from Sdccag8+/+ and Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice at P14 using the anti-acetylated α-tubulin antibody. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (F). The numbers (G) and length (H) of the cilia stained with an antibody against acetylated α-tubulin were measured. Error bars show SD. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01 (unpaired t test). G, Sdccag8+/+, n = 3 mice; Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC, n = 4 mice. H, Sdccag8+/+, n = 465 cilia from three mice; Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC, n = 427 cilia from four mice. I–N, ERG analysis of Sdccag8+/+ and Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice at 6 weeks (I and L). Representative scotopic ERGs (I) elicited by four different stimulus intensities (−4.0 to 1.0 log cd s/m2) and photopic ERGs (L) elicited by four different stimulus intensities (−0.5 to 1.0 log cd s/m2) from Sdccag8+/+ and Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice. J and K, the scotopic amplitudes of a-waves (J) and b-waves (K) are shown as a function of the stimulus intensity. M and N, the photopic amplitudes of a-waves (M) and b-waves (N) are shown as a function of the stimulus intensity. Error bars show SD. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001 (unpaired t test). Sdccag8+/+, n = 6 mice; Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC, n = 3 mice. ERG, electroretinogram; GCL, ganglion cell layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; IPL, inner plexiform layer; IS, inner segments; ONL, outer nuclear layer; OS, outer segment.

To investigate whether the loss of Sdccag8-C affects photoreceptor function, we measured the electroretinograms (ERGs) of Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice under dark-adapted (scotopic) and light-adapted (photopic) conditions. We observed that the amplitudes of a-waves (photoreceptors) and b-waves (ON bipolar cells) of Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice under both scotopic and photopic conditions significantly decreased compared with those of Sdccag8+/+ mice at 6 weeks (Fig. 6, I–N). These results indicate that rod and cone photoreceptor function is impaired by the Sdccag8-C deficiency.

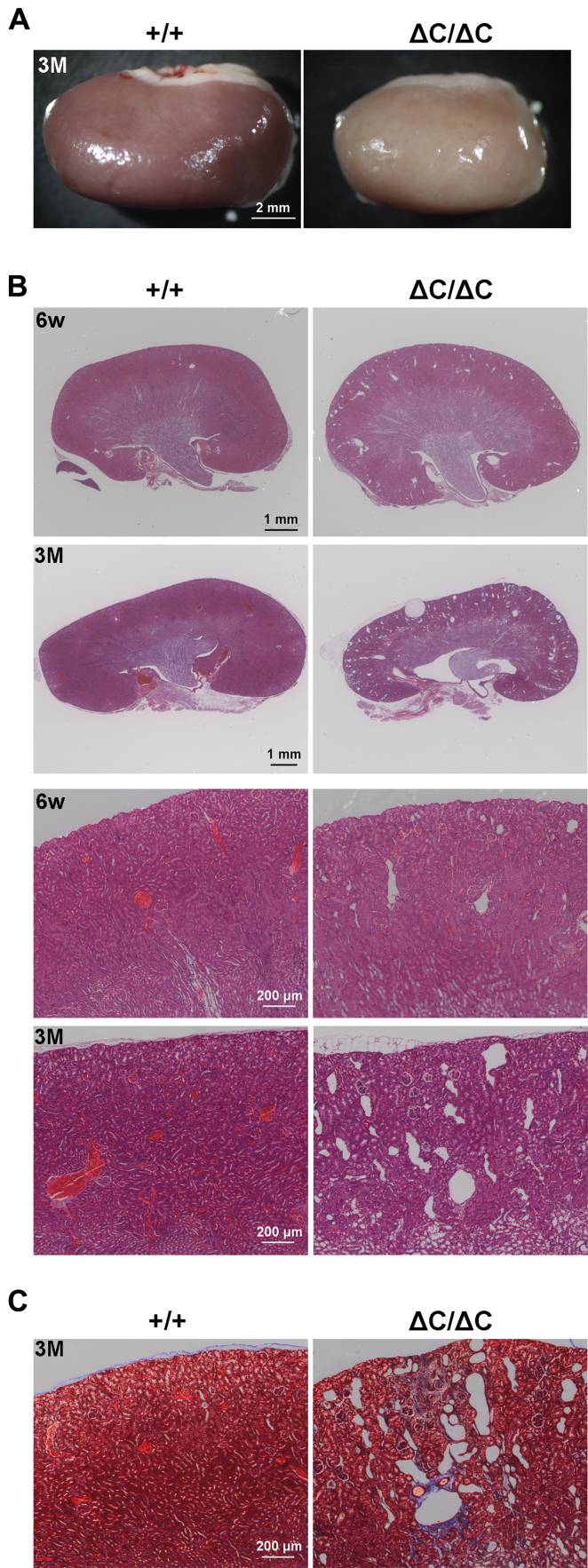

Deficiency of the C-terminal region of Sdccag8 causes renal degeneration

To investigate the role of Sdccag8-C in the kidney, we first observed the gross appearance of the Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC kidney. Anemic kidneys were observed in Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice at 3 months (Fig. 7A). Next, we performed hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining using renal sections from Sdccag8+/+ and Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice at 6 weeks and 3 months. The H&E staining showed progressive cyst formation in the Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC kidney from 6 weeks to 3 months (Fig. 7B). To examine renal interstitial fibrosis, which are observed in patients with NPHP (39), in the Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC kidney, we performed Masson trichrome staining using renal sections from Sdccag8+/+ and Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice at 3 months. This revealed interstitial fibrosis in the Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC kidney (Fig. 7C). These results suggest that Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice exhibit NPHP-like phenotypes, and the loss of Sdccag8-C leads to cyst formation, interstitial fibrosis, and subsequent renal degeneration.

Figure 7.

Renal degeneration in the Sdccag8ΔC/ΔCkidney.A, gross appearance of kidneys from Sdccag8+/+ and Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice at 3 months. Pale appearance was observed in the Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC kidney. B, H&E staining of renal sections from Sdccag8+/+ and Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice at 6 weeks and 3 months. The lower panels indicate higher magnification views of each upper panels. Progressive cyst formation was observed in the Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC kidney. C, Masson trichrome staining of renal sections from Sdccag8+/+ and Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice at 3 months. Interstitial fibrosis was observed in the Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC kidney. H&E, hematoxylin and eosin.

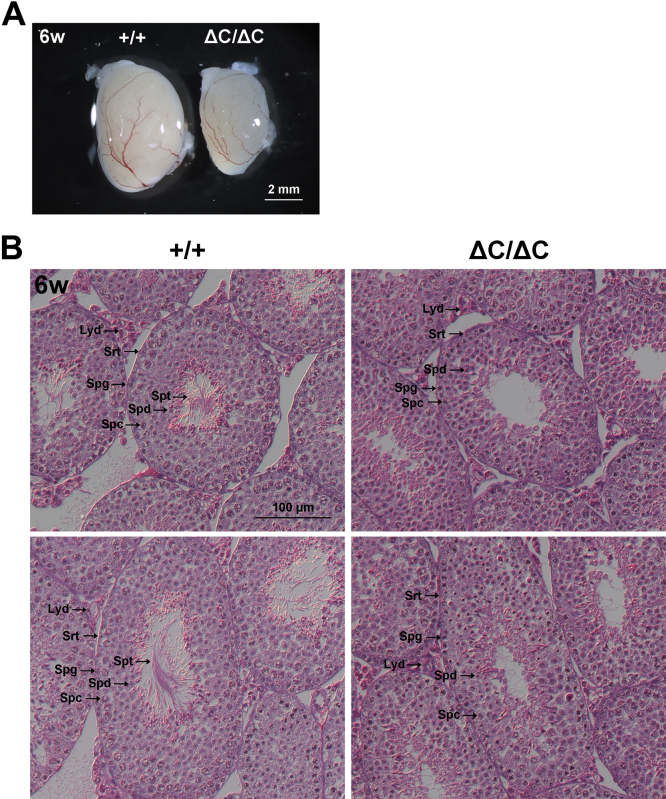

Deficiency of the C-terminal region of Sdccag8 causes impaired spermatogenesis

It has previously been reported that patients with mutations in SDCCAG8 gene display hypogonadism and hypogenitalism (12); however, the role of Sdccag8 in the testis remains unclear. We analyzed the testes from Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice and observed that the testes of Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice were smaller than those of Sdccag8+/+ mice (Fig. 8A). During spermatogenesis within seminiferous tubules, spermatogonia sequentially divide and differentiate into spermatocytes, spermatids, and sperm (40). To examine the roles of Sdccag8 in the testes, we performed histological analyses using testicular sections from male Sdccag8+/+ and Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice. H&E staining showed a lack of mature sperm with long tails in the seminiferous tubules of the Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC testis at 6 weeks, indicating that production of mature sperm is diminished in the Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC testes (Fig. 8B). In contrast, we observed spermatogonia, spermatocytes, and spermatids in the Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC testis, suggesting that the mitosis and meiosis phases in the Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC testis are normal. In addition, Leydig and Sertoli cells were also observed in the Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC testes. Taken together, our results suggest that Sdccag8-C is required for normal spermatogenesis. Sdccag8 may play a role in sperm flagella formation.

Figure 8.

Histological abnormality in the Sdccag8ΔC/ΔCtestis.A, gross appearance of the testes of male Sdccag8+/+ and Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice at 6 weeks. The testes from Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice were smaller than those from Sdccag8+/+ mice. B, H&E staining of testicular sections from male Sdccag8+/+ and Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice at 6 weeks. Mature sperm could not be observed in the Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC testis. H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; Lyd, Leydig cells; Spc, spermatocytes; Spd, spermatids; Spg, spermatogonia; Spt, sperm tails; Srt, Sertoli cells.

Discussion

In the current study, we screened and found that Ick and Mak interact with Sdccag8-C. To analyze the roles of Sdccag8-C in vivo, we generated Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice, in which Sdccag8-C was truncated, by the CRISPR-mediated stop codon knock-in strategy. We observed ciliopathy-like organ phenotypes, including cleft palate, polydactyly, retinal and renal degeneration, and abnormal spermatogenesis in Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice, although there may be defects in other tissues. Indeed, we also found ciliary abnormalities in Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice, suggesting that Sdccag8-C is required for normal cilia formation and function. Previous reports showed that Sdccag8 knockout mice mostly die after birth and that Sdccag8 gene-trap mice are present at Mendelian ratios at weaning age (17, 20). Unlike Sdccag8 knockout mice and Sdccag8 gene-trap mice, Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice exhibited partial postnatal lethality. Together, our findings and previous reports suggest that Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice can be used as a distinct and useful mouse model to understand the pathological mechanisms underlying the ciliopathies associated with mutations in SDCCAG8 gene.

In the Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC testis, we observed a lack of mature sperm with long tails in seminiferous tubules, suggesting that Sdccag8-C is required for normal spermatogenesis. Since previous studies have shown that Sdccag8 is expressed in spermatocytes and spermatids in the mature rat testes (41), Sdccag8 may play a role in sperm flagella formation in a cell autonomous manner. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that dysfunction of Leydig cells and/or Sertoli cells by the loss of Sdccag8-C leads to the abnormal spermatogenesis in the Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC testis. Furthermore, we have to consider the possible dysfunction of the hypothalamus and/or pituitary gland in Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice. Our findings provide insights into the pathological mechanisms underlying hypogonadism and hypogenitalism in patients with mutations in SDCCAG8 gene and the roles of Sdccag8 in the testis. Understanding the detailed molecular and pathological mechanisms of Sdccag8 dysfunction in the testis awaits future analyses.

How is Sdccag8-C involved in cilia formation and function? We found that Sdccag8-C interacts with Ick and Mak proteins by immunoprecipitation assay. We previously found that Ick localizes mainly to the ciliary tips; however, several studies have reported that Ick also localizes to the ciliary base (22, 23, 24). Furthermore, we previously found that Mak localizes to the connecting cilia and ciliary axonemes, as well as basal bodies in retinal photoreceptor cells (21). Given that Sdccag8 localizes to centrosomes and basal bodies (10, 11), Sdccag8 is suggested to colocalize with Ick and Mak at basal bodies. We found a decrease in ciliated cell number, cilia length, and Gli1 expression level in Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC MEFs. These phenotypes in Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC MEFs were similarly observed in Ick-deficient MEFs (22). In addition, retinal photoreceptor cells in Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice showed the mislocalization of Rhodopsin and elongated cilia, which were also observed in the Mak-deficient retina (21). In contrast, unlike Ick- and Mak-deficient mice, Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice showed no obvious and significant differences in the ciliary localization of IFT88 and Smo. Ick and Mak have been proposed to serve as regulators of IFT turnaround at the ciliary tip and cilia length in mammals (21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26). Remarkably, Caenorhabditis elegans DYF-5, an ortholog of Ick and Mak, was proposed to regulate cilia length and morphology via modulation of microtubule stability rather than IFT (42). Ick and Mak may modulate cilia length independent of IFT regulation, through interaction with Sdccag8 at the ciliary base. In humans, mutations in ICK and MAK genes have been reported to lead to retinal degeneration, cystic kidneys, genital abnormalities, and respiratory failure (31, 32, 33, 34, 35), which are also associated with human SDCCAG8 mutations (11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16). In addition, pathogenic variants in the ICK gene have been linked to juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (43). A previous study reported that a patient with a mutation in the SDCCAG8 gene displayed epilepsy (14). Collectively, our observations and previous reports suggest that Sdccag8 functionally interacts with Ick and Mak. However, since the yeast two-hybrid screening identified other proteins that interact with the Ick protein, we cannot exclude the possibility that Ick and Mak interact and function with other proteins at basal bodies.

We observed that Sdccag8-FL and Sdccag8-C localize to centrosomes in NIH-3T3 cells, whereas signals of Sdccag8-N, Sdccag8-M, Sdccag8-NM, Sdccag8-C1, Sdccag8-C2, Sdccag8-C3, and Sdccag8-C4 could not be detected at centrosomes, suggesting that Sdccag8-C serves as a module localizing at basal bodies. We also observed weak localization of Sdccag8 to centrosomes and/or basal bodies in Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC MEFs and photoreceptor cells. How does Sdccag8-C play key roles in the localization of Sdccag8 to basal bodies? Sdccag8-C consists of coiled-coil motifs that are commonly associated with protein–protein interactions (11, 44). Several centrosomal/basal body proteins recruit interacting partners to the basal bodies (45, 46, 47). It is possible that Sdccag8 localizes to basal bodies via the interaction of Sdccag8-C with centrosomal/basal body proteins. For example, previous studies reported that SDCCAG8-C interacts with oral-facial-digital syndrome 1, a centrosomal/basal body protein associated with oral-facial-digital syndrome, Joubert syndrome, and retinitis pigmentosa (11, 48, 49, 50). In addition, it was previously reported that SDCCAG8-C interacts with RAB GTPase binding effector protein 2 (RABEP2) that localizes to basal bodies and is required for cilia formation (18). Given that Sdccag8 also interacts with Ick and Mak, Sdccag8 may play a key role as the hub of the ciliary/basal body protein–protein interaction network.

In human SDCCAG8 gene, mutations that are predicted to truncate the Sdccag8 C terminus were reported to be associated with multiple organ defects, including retinal degeneration and cystic kidney (11, 12, 13). Our results suggest that Sdccag8-C is an Ick- and Mak-interacting module that is required for the localization of Sdccag8 to centrosomes/basal bodies and is essential for cilia formation and thereby organ development and homeostasis. The current findings shed light on the pathological mechanisms underlying the ciliopathies associated with mutations in SDCCAG8 gene. Additional mechanistic studies focusing on the relationship between Sdccag8 and the serine–threonine kinases Ick and Mak will advance our understanding of the detailed molecular and pathological mechanisms underlying the ciliopathies.

Experimental procedures

Animal care

All procedures conformed to the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research, and these procedures were approved by the Institutional Safety Committee on Recombinant DNA Experiments (approval ID 04220) and the Animal Experimental Committees of Institute for Protein Research (approval ID 29-01-4), Osaka University, and were performed in compliance with the institutional guidelines. Mice were housed in a temperature-controlled room at 22 °C with a 12 h light/dark cycle. Fresh water and rodent diet were available at all times.

Generation of Sdccag8 Arg537Stop knock-in (Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC) mice

Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC mice were generated using the Alt-R CRISPR-Cas9 system (IDT). The crRNA (IDT) was designed to target exon 13 of the Sdccag8 gene using CRISPRdirect (http://crispr.dbcls.jp/). Single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) (IDT) containing an Arg537Stop codon and an EcoRI restriction site was also designed with 60 bp homology sequences on each side of the targeting codon. The crRNA and tracrRNA (IDT) in a duplex buffer (IDT) were incubated at 37 °C for 5 min and returned to room temperature. The guide RNA complex was mixed with Cas9 nuclease 3NLS (IDT), incubated at room temperature for 5 min, and then mixed with ssDNA in Opti-MEM (Gibco) before electroporation. The ribonucleoprotein complex and ssDNA were electroporated into the fertilized one-cell eggs of B6C3F1 mice. The founder mouse was then backcrossed with the C57BL/6J mice.

Plasmid construction

Plasmids expressing FLAG or HA-tagged Ick, FLAG-tagged EGFP, and EGFP were previously constructed (21, 22). Full-length cDNA fragments of mouse Mak and Sdccag8 were amplified by PCR using mouse retinal cDNA as a template and subcloned into the pCAGGSII-3xFLAG and pCAGGSII-2xHA vectors (51). The cDNA fragments encoding the mouse Sdccag8-N, Sdccag8-M, and Sdccag8-C were amplified by PCR using mouse retinal cDNA as a template and subcloned into the pCAGGSII-3xFLAG vector. The cDNA fragment encoding the mouse Sdccag8-NM, Sdccag8-C1, Sdccag8-C2, Sdccag8-C3, and Sdccag8-C4 were amplified by PCR using the plasmid encoding Sdccag8-FL as a template and subcloned into the pCAGGSII-3xFLAG vector. A full-length cDNA fragment of human SDCCAG8 was amplified by PCR using human retinal cDNA (Clontech) as a template and subcloned into the pCAGGSII-3xFLAG vector. The cDNA fragment encoding the human SDCCAG8-NM was amplified by PCR using the plasmid encoding full-length human SDCCAG8 as a template and subcloned into the pCAGGSII-3xFLAG vector. The cDNA fragment encoding EGFP was amplified by PCR using the plasmid encoding EGFP as a template and subcloned into the pCAGGSII-2xHA vector. For Sdccag8 knockdown, the Sdccag8-shRNA and shRNA-control cassette was subcloned into pBAsi-mU6 vector (Takara). The target sequences were as follows: Sdccag8-shRNA1, 5′-GCACAGCCATGCTGTCAATCA-3’; Sdccag8-shRNA2, 5′-GGAGACATTGAGGGAGCAAAC-3’; Sdccag8-shRNA3, 5′-GCGCAGAAGAGA GAGACAAGT-3’; shRNA-control, 5′-GACGTCTAACGGATTCGAGCT-3’ (52). For the production of AAV-Sdccag8-shRNA and AAV-shRNA-control, the mU6-Sdccag8-shRNA3 or mU6-shRNA-control fragment was inserted into the pAAV-CAG-AcGFP vector (53). Primer sequences used for amplification are shown in Table S2.

Yeast two-hybrid screening

Yeast two-hybrid screening was performed as described previously (54). In brief, we performed a yeast two-hybrid screen using the MATCHMAKER GAL4 Two-Hybrid System3 (Takara Bio). The open reading frame of mouse Ick was inserted into the pGBKT7 bait plasmid and transformed into the AH109 yeast strain. We screened 1.0 × 106 transformants from a one-to-one mixture of mouse E17 whole embryos and the P0-P3 retinal cDNA library. Positive colonies were identified on the basis of their ability to express the nutritional markers ADE2 and HIS3 by plating on synthetic defined (-Trp, -Leu, -Ade, -His) medium. The plasmids were isolated from yeast using Zymoprep Yeast Plasmid Miniprep I (Zymo Research) and transformed into E. coli DH5α.

Cell culture and transfection

Sdccag8+/+ and Sdccag8ΔC/ΔC MEFs were derived from embryonic day 13.5 embryos and cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Sigma) containing 10% fetal bovine serum supplemented with penicillin (100 μg/ml) and streptomycin (100 μg/ml) at 37 °C with 5% CO₂. To induce ciliogenesis in MEFs, cells were grown to 80 to 90% confluency and serum-starved for 24 h. Cells were incubated with SAG (100 nM) for 24 h in serum-free medium. HEK293T and NIH-3T3 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 10% fetal bovine and calf serum, respectively, supplemented with penicillin (100 μg/ml) and streptomycin (100 μg/ml) at 37 °C with 5% CO₂. Transfection was performed with the calcium phosphate method for HEK293T cells or Lipofectamine LTX (Invitrogen) for NIH-3T3 cells. To induce ciliogenesis in transfected cells, the medium was replaced by serum-free medium at 24 h or 48 h after the transfection, and cells were cultured for 24 h in serum-free medium.

Immunoprecipitation assay

Immunoprecipitation assays were performed as previously described (55). HEK293T cells were co-transfected with plasmids expressing FLAG and HA-tagged proteins. After 48 h of transfection, the cells were lysed in a lysis buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors (20 mM Tris (hydroxymethyl) aminomethane [Tris]–HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40 [NP-40], 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetate [EDTA], 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], 2 μg/ml leupeptin, 5 μg/ml aprotinin, and 3 μg/ml pepstatin A). The cell lysates were centrifuged twice at 15,100 g for 5 min. The supernatants were incubated with an anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel (Sigma-Aldrich) overnight at 4 °C. The beads were washed five times with wash buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, and 1 mM EDTA) and then eluted with elution buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mg/ml 1 × FLAG peptide) for 30 min at 4 °C. The immunoprecipitated samples were incubated with sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-sample buffer for 30 min at room temperature and analyzed by Western blot. For immunoprecipitation from HEK293T cell lysates, the cells were lysed in a RIPA buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Roche) (20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 1 mM PMSF, 2 μg/ml leupeptin, 5 μg/ml aprotinin, and 3 μg/ml pepstatin A). The cell lysates and antibodies were incubated overnight at 4 °C and then were incubated for 6 h at 4 °C with Protein A Sepharose four Fast Flow (GE Healthcare). The beads were washed five times with wash buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS). The immunoprecipitated samples were incubated with SDS-sample buffer for 5 min at 100 °C and analyzed by Western blot.

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was performed as described previously (56). Briefly, HEK293T cells were lysed in a lysis buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors (20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM PMSF, 2 μg/ml leupeptin, 5 μg/ml aprotinin, and 3 μg/ml pepstatin A) or RIPA buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Roche) (20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 1 mM PMSF, 2 μg/ml leupeptin, 5 μg/ml aprotinin, and 3 μg/ml pepstatin A). The samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane using semidry transfer cells (Bio-Rad or iBlot system; Invitrogen). The membranes were blocked with blocking buffer (3% skim milk, and 0.05% Tween 20 in Tris-buffered saline). Signals were detected using Chemi-Lumi One L (Nakalai Tesque) or Pierce Western Blotting Substrate Plus (Thermo Fisher Scientific). We used the following primary antibodies: rabbit anti-FLAG (1:5,000, Sigma, F7425); rat anti-HA (1: 2500 or 1:5,000, Roche, 3F10); rabbit anti-GFP (1:5,000, MBL, 598); guinea pig anti-Ick (1:50) (22); and rabbit anti-Sdccag8 (1:200, Proteintech, 13471-1-AP). The following secondary antibodies were used: horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (1:10,000, Jackson Laboratory), anti-rat IgG (1:10,000, Jackson Laboratory), and anti-guinea pig IgG (1:10,000, Jackson Laboratory).

Immunofluorescent analysis of cells and retinal sections

Immunofluorescent analysis of cells and retinal sections was performed as described previously (21). Cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS for 5 min at rom temperature or cold methanol for 5 min at −20 °C, subsequently incubated with blocking buffer (5% normal donkey serum, and 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS) for 30 min at room temperature, and then immunostained with primary antibodies in the blocking buffer overnight at 4 °C. Cells were washed with PBS and incubated with secondary antibodies and DAPI (1:1000, Nacalai Tesque) in the blocking buffer for 2 to 4 h at room temperature. Mouse eyes were fixed in 4% PFA in PBS for 15 s, 5 min or 10 min at room temperature, embedded in TissueTec OCT compound 4583 (Sakura), frozen, and cryosectioned at 20 μm thickness. Frozen sections on slides were dried overnight at room temperature, rehydrated in PBS, incubated with the blocking buffer, and then immunostained with primary antibodies in the blocking buffer overnight at 4 °C. Slides were washed with PBS and incubated with secondary antibodies and DAPI in the blocking buffer for 2 to 4 h at room temperature. The specimens were observed under a laser confocal microscope (LSM700 or LSM710, Carl Zeiss). We used the following primary antibodies: rabbit anti-FLAG (1:1,000, Sigma, F7425); rat anti-HA (1: 1000, Roche, 3F10); mouse anti-acetylated α tubulin (1:1000 or 1:2,000, Sigma, 6-11B-1); rabbit anti-IFT88 (1:1,000, Proteintech, 13967-1-AP); rabbit anti-Arl13b (1:500, Proteintech, 17711-1-AP); mouse anti-Smo (1:150, Santa Cruz, sc-166685); rabbit anti-Rhodopsin (1:1,000, LSL, LB-5597), goat anti-S-opsin (1:500, Santa Cruz, sc-14363); rabbit anti-M-opsin (1:300, Millipore, AB5405); rabbit anti-Sdccag8 (1:250 or 1:500, Proteintech, 13471-1-AP); rat anti-GFP (1:1,000, Nacalai Tesque, 04404-84); mouse anti-γ-tubulin (1:300, Sigma, T6557); rabbit IgG isotype control (same concentration as anti-Sdccag8 [1:500, Proteintech, 13471-1-AP], Abcam, ab172730). Cy3-conjugated (1:500, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories), DyLight 649-conjugated (1:500, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories), or Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated (1:500, Sigma) secondary antibodies were used.

RT-PCR and qRT-PCR analyses

RT-PCR and qRT-PCR analyses were performed as described previously (30, 57). Total RNAs were isolated from MEFs and mouse tissues, including the retina, cerebrum, cerebellum, brain stem, thymus, heart, lung, kidney, liver, spleen, muscle, intestine, ovary, and testis, using TRIzol RNA extraction reagent (Invitrogen). The total RNA (0.5 or 2 μg) was reverse transcribed into cDNA using PrimeScript RT reagent or PrimeScript II reagent (Takara). The cDNAs were used as templates for RT-PCR reactions with rTaq polymerase (Takara). qRT-PCR was performed using a SYBR GreenER qPCR Super Mix Universal (Invitrogen) and Thermal Cycler Dice Real Time System Single MRQ TP700 (Takara) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantification was performed by Thermal Cycler Dice Real Time System software version 2.11 (Takara). Primer sequences used for amplification are shown in Table S2.

In situ hybridization

Eyeballs were freshly frozen and cryosectioned at 14 μm thickness. Generation of a digoxigenin-labeled riboprobe and in situ hybridization were performed as described previously (51). The cDNA fragment encoding the Sdccag8-NM was used to synthesize the riboprobe.

Toluidine blue staining

Toluidine blue staining of retinal sections was performed as described previously (58). Retinal sections were rinsed with PBS and stained with 0.1% toluidine blue in PBS for 30 s. After washing with PBS, slides were coverslipped and immediately observed under the microscope. ONL and inner nuclear layer + inner plexiform layer + ganglion cell layer thicknesses were measured and quantified with the National Institutes of Health ImageJ software.

AAV production and subretinal injection

AAV production and subretinal injection of AAVs were performed as previously described (59). AAVs were produced by triple transfection of an AAV vector plasmid, an adenovirus helper plasmid, and an AAV helper plasmid (pXR5) into AAV-293 cells using the calcium phosphate method. The cells were harvested 72 h after transfection and lysed in four freeze-thaw cycles. The supernatant was collected by centrifugation and treated with benzonase nuclease (Novagen). The viruses were purified using an iodixanol gradient. The gradient was formed in Ultra-Clear centrifuge tubes (14 × 95 mm, Beckman) by first adding 54% iodixanol (Axis-Shield) in PBS-MK buffer (1 × PBS, 1 mM MgCl2, and 25 mM KCl), followed by overlaying 40% iodixanol in PBS-MK buffer, 25% iodixanol in PBS-MK buffer containing phenol red, and 15% iodixanol in PBS-MK buffer containing 1 M NaCl. The tubes were centrifuged at 40,000 rpm in an SW40Ti rotor. The 54% to 40% fraction containing virus was collected using an 18-gauge needle and concentrated using an Amicon Ultra Centrifugal Filter Ultracel-100K (Millipore). The titer of each AAV (in vector genomes (VG)/ml) was determined by qPCR using SYBR GreenER Q-PCR Super Mix (Invitrogen) and Thermal Cycler Dice Real Time System Single MRQ TP700 (Takara). The primers used for the AAV titrations are listed in Table S2. The titers of AAV-shRNA-control and AAV-Sdccag8-shRNA3 were adjusted to approximately 2 × 1012 VG/ml. 0.3 μl of the AAV preparations was injected into the subretinal spaces of the P0 ICR mice. The injected retinas were harvested at P15.

ERG analysis

ERG analysis was performed as described previously (60). Briefly, ERG responses were measured by the PuREC system with LED LS-100 (Mayo). Mice were dark-adapted overnight and then anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of 100 mg/kg ketamine and 10 mg/kg xylazine diluted in saline (Otsuka). The mice were placed on a heating pad and stimulated with four stroboscopic stimuli ranging from −4.0 to 1.0 log cd s/m2 for scotopic ERGs. After the mice were light-adapted for 10 min, they were stimulated with four stroboscopic stimuli ranging from −0.5 to 1.0 log cd s/m2 for photopic ERGs. The photopic ERGs were recorded on a rod-suppressing white background of 1.3 log cd s/m2.

H&E staining and Masson trichrome staining

H&E and Masson trichrome stainings were commissioned to Applied Medical Research Laboratory. Mouse kidneys and testes were fixed with 4% PFA in PBS for 72 h at 4 °C and Bouin solution for 20 h at 4 °C, respectively, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned at 5 μm thickness.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was evaluated using unpaired t test, one-way ANOVA, or two-way ANOVA. A value of p < 0.05 was taken to be statistically significant.

Data availability

All data are contained in the manuscript.

Supporting information

This article contains supporting information.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Kadowaki, A. Tani, T. Kon, M. Wakabayashi, S. Gion, T. Nakayama, M. Nakamura, K. Yoshida, and M. Nishi for technical assistance. This work was supported by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) (21H02657), (C) (20K07326), and JSPS Fellows (20J12966) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, The Takeda Science Foundation, The Uehara Memorial Foundation, The Cell Science Research Foundation, and Suzuken Memorial Foundation.

Author contributions

R. T., T. C., and T. F. conceptualization; R. T., T. C., T. T., and T. F. methodology; R. T., T. C., T. T., and T. F. validation; R. T. and T. C. formal analysis; R. T., T. C., and T. T. investigation; R. T., T. C., and T. T. resources; R. T. and T. C. data curation; R. T. and T. C. writing-original draft; T. F. writing-review & editing; R. T. and T. C. visualization; T. F. supervision; T. F. project administration; R. T., T. C., and T. F. funding acquisition.

Edited by Enrique De La Cruz

Supporting information

References

- 1.Gerdes J.M., Davis E.E., Katsanis N. The vertebrate primary cilium in development, homeostasis, and disease. Cell. 2009;137:32–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malicki J.J., Johnson C.A. The cilium: Cellular antenna and central processing unit. Trends Cell Biol. 2017;27:126–140. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2016.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ishikawa H., Marshall W.F. Ciliogenesis: Building the cell's antenna. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011;12:222–234. doi: 10.1038/nrm3085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nigg E.A., Raff J.W. Centrioles, centrosomes, and cilia in health and disease. Cell. 2009;139:663–678. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hildebrandt F., Benzing T., Katsanis N. Ciliopathies. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;364:1533–1543. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1010172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reiter J.F., Leroux M.R. Genes and molecular pathways underpinning ciliopathies. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017;18:533–547. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2017.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lovera M., Luders J. The ciliary impact of nonciliary gene mutations. Trends Cell Biol. 2021;31:876–887. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2021.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McConnachie D.J., Stow J.L., Mallett A.J. Ciliopathies and the kidney: A review. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2021;77:410–419. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2020.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luo F., Tao Y.H. Nephronophthisis: A review of genotype-phenotype correlation. Nephrology (Carlton) 2018;23:904–911. doi: 10.1111/nep.13393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kenedy A.A., Cohen K.J., Loveys D.A., Kato G.J., Dang C.V. Identification and characterization of the novel centrosome-associated protein CCCAP. Gene. 2003;303:35–46. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(02)01141-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Otto E.A., Hurd T.W., Airik R., Chaki M., Zhou W., Stoetzel C., Patil S.B., Levy S., Ghosh A.K., Murga-Zamalloa C.A., van Reeuwijk J., Letteboer S.J., Sang L., Giles R.H., Liu Q., et al. Candidate exome capture identifies mutation of SDCCAG8 as the cause of a retinal-renal ciliopathy. Nat. Genet. 2010;42:840–850. doi: 10.1038/ng.662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schaefer E., Zaloszyc A., Lauer J., Durand M., Stutzmann F., Perdomo-Trujillo Y., Redin C., Bennouna Greene V., Toutain A., Perrin L., Gerard M., Caillard S., Bei X., Lewis R.A., Christmann D., et al. Mutations in SDCCAG8/NPHP10 cause Bardet-Biedl syndrome and are associated with penetrant renal disease and absent polydactyly. Mol. Syndromol. 2011;1:273–281. doi: 10.1159/000331268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Billingsley G., Vincent A., Deveault C., Heon E. Mutational analysis of SDCCAG8 in Bardet-Biedl syndrome patients with renal involvement and absent polydactyly. Ophthalmic Genet. 2012;33:150–154. doi: 10.3109/13816810.2012.689411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamamura T., Morisada N., Nozu K., Minamikawa S., Ishimori S., Toyoshima D., Ninchoji T., Yasui M., Taniguchi-Ikeda M., Morioka I., Nakanishi K., Nishio H., Iijima K. Rare renal ciliopathies in non-consanguineous families that were identified by targeted resequencing. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 2017;21:136–142. doi: 10.1007/s10157-016-1256-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watanabe Y., Fujinaga S., Sakuraya K., Morisada N., Nozu K., Iijima K. Rapidly progressive nephronophthisis in a 2-year-old boy with a homozygous SDCCAG8 mutation. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 2019;249:29–32. doi: 10.1620/tjem.249.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bahmanpour Z., Daneshmandpour Y., Kazeminasab S., Khalil Khalili S., Alehabib E., Chapi M., Soosanabadi M., Darvish H., Emamalizadeh B. A novel splice site mutation in the SDCCAG8 gene in an Iranian family with Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Int. Ophthalmol. 2021;41:389–397. doi: 10.1007/s10792-020-01588-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Insolera R., Shao W., Airik R., Hildebrandt F., Shi S.H. SDCCAG8 regulates pericentriolar material recruitment and neuronal migration in the developing cortex. Neuron. 2014;83:805–822. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Airik R., Schueler M., Airik M., Cho J., Ulanowicz K.A., Porath J.D., Hurd T.W., Bekker-Jensen S., Schroder J.M., Andersen J.S., Hildebrandt F. SDCCAG8 interacts with RAB effector proteins RABEP2 and ERC1 and is required for hedgehog signaling. PLoS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flynn M., Whitton L., Donohoe G., Morrison C.G., Morris D.W. Altered gene regulation as a candidate mechanism by which ciliopathy gene SDCCAG8 contributes to schizophrenia and cognitive function. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2020;29:407–417. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddz292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Airik R., Slaats G.G., Guo Z., Weiss A.C., Khan N., Ghosh A., Hurd T.W., Bekker-Jensen S., Schroder J.M., Elledge S.J., Andersen J.S., Kispert A., Castelli M., Boletta A., Giles R.H., et al. Renal-retinal ciliopathy gene Sdccag8 regulates DNA damage response signaling. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2014;25:2573–2583. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013050565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Omori Y., Chaya T., Katoh K., Kajimura N., Sato S., Muraoka K., Ueno S., Koyasu T., Kondo M., Furukawa T. Negative regulation of ciliary length by ciliary male germ cell-associated kinase (Mak) is required for retinal photoreceptor survival. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:22671–22676. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009437108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chaya T., Omori Y., Kuwahara R., Furukawa T. ICK is essential for cell type-specific ciliogenesis and the regulation of ciliary transport. EMBO J. 2014;33:1227–1242. doi: 10.1002/embj.201488175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moon H., Song J., Shin J.O., Lee H., Kim H.K., Eggenschwiller J.T., Bok J., Ko H.W. Intestinal cell kinase, a protein associated with endocrine-cerebro-osteodysplasia syndrome, is a key regulator of cilia length and Hedgehog signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014;111:8541–8546. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323161111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Broekhuis J.R., Verhey K.J., Jansen G. Regulation of cilium length and intraflagellar transport by the RCK-kinases ICK and MOK in renal epithelial cells. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Okamoto S., Chaya T., Omori Y., Kuwahara R., Kubo S., Sakaguchi H., Furukawa T. Ick ciliary kinase is essential for planar cell polarity formation in inner ear hair cells and hearing function. J. Neurosci. 2017;37:2073–2085. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3067-16.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chaya T., Furukawa T. Post-translational modification enzymes as key regulators of ciliary protein trafficking. J. Biochem. 2021;169:633–642. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvab024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miyata Y., Nishida E. Distantly related cousins of MAP kinase: Biochemical properties and possible physiological functions. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999;266:291–295. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Togawa K., Yan Y.X., Inomoto T., Slaugenhaupt S., Rustgi A.K. Intestinal cell kinase (ICK) localizes to the crypt region and requires a dual phosphorylation site found in map kinases. J. Cell Physiol. 2000;183:129–139. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(200004)183:1<129::AID-JCP15>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shinkai Y., Satoh H., Takeda N., Fukuda M., Chiba E., Kato T., Kuramochi T., Araki Y. A testicular germ cell-associated serine-threonine kinase, MAK, is dispensable for sperm formation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:3276–3280. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.10.3276-3280.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsutsumi R., Chaya T., Furukawa T. Enriched expression of the ciliopathy gene Ick in cell proliferating regions of adult mice. Gene Expr. Patterns. 2018;29:18–23. doi: 10.1016/j.gep.2018.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lahiry P., Wang J., Robinson J.F., Turowec J.P., Litchfield D.W., Lanktree M.B., Gloor G.B., Puffenberger E.G., Strauss K.A., Martens M.B., Ramsay D.A., Rupar C.A., Siu V., Hegele R.A. A multiplex human syndrome implicates a key role for intestinal cell kinase in development of central nervous, skeletal, and endocrine systems. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2009;84:134–147. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oud M.M., Bonnard C., Mans D.A., Altunoglu U., Tohari S., Ng A.Y.J., Eskin A., Lee H., Rupar C.A., de Wagenaar N.P., Wu K.M., Lahiry P., Pazour G.J., Nelson S.F., Hegele R.A., et al. A novel ICK mutation causes ciliary disruption and lethal endocrine-cerebro-osteodysplasia syndrome. Cilia. 2016;5:8. doi: 10.1186/s13630-016-0029-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paige Taylor S., Kunova Bosakova M., Varecha M., Balek L., Barta T., Trantirek L., Jelinkova I., Duran I., Vesela I., Forlenza K.N., Martin J.H., Hampl A., University of Washington Center for Mendelian Genomics. Bamshad M., Nickerson D., et al. An inactivating mutation in intestinal cell kinase, ICK, impairs hedgehog signalling and causes short rib-polydactyly syndrome. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2016;25:3998–4011. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddw240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tucker B.A., Scheetz T.E., Mullins R.F., DeLuca A.P., Hoffmann J.M., Johnston R.M., Jacobson S.G., Sheffield V.C., Stone E.M. Exome sequencing and analysis of induced pluripotent stem cells identify the cilia-related gene male germ cell-associated kinase (MAK) as a cause of retinitis pigmentosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:E569–E576. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108918108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ozgul R.K., Siemiatkowska A.M., Yucel D., Myers C.A., Collin R.W., Zonneveld M.N., Beryozkin A., Banin E., Hoyng C.B., van den Born L.I., European Retinal Disease Consortium. Bose R., Shen W., Sharon D., Cremers F.P., et al. Exome sequencing and cis-regulatory mapping identify mutations in MAK, a gene encoding a regulator of ciliary length, as a cause of retinitis pigmentosa. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2011;89:253–264. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huangfu D., Anderson K.V. Cilia and Hedgehog responsiveness in the mouse. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:11325–11330. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505328102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen J.K., Taipale J., Young K.E., Maiti T., Beachy P.A. Small molecule modulation of smoothened activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:14071–14076. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182542899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rohatgi R., Milenkovic L., Scott M.P. Patched1 regulates Hedgehog signaling at the primary cilium. Science. 2007;317:372–376. doi: 10.1126/science.1139740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hildebrandt F., Zhou W. Nephronophthisis-associated ciliopathies. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2007;18:1855–1871. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006121344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cheng C.Y., Mruk D.D. Cell junction dynamics in the testis: Sertoli-germ cell interactions and male contraceptive development. Physiol. Rev. 2002;82:825–874. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00009.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kamio T., Asano A., Hosaka Y.Z., Khalid A.M., Yokota S., Ohta M., Ohyama K., Yamano Y. Expression of the centrosomal colon cancer autoantigen gene during spermatogenesis in the maturing rat testis. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2010;74:1466–1469. doi: 10.1271/bbb.100044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maurya A.K., Rogers T., Sengupta P. A CCRK and a MAK kinase modulate cilia branching and length via regulation of axonemal microtubule dynamics in Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr. Biol. 2019;29:1286–1300.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2019.02.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bailey J.N., de Nijs L., Bai D., Suzuki T., Miyamoto H., Tanaka M., Patterson C., Lin Y.C., Medina M.T., Alonso M.E., Serratosa J.M., Duron R.M., Nguyen V.H., Wight J.E., Martinez-Juarez I.E., et al. Variant intestinal-cell kinase in juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018;378:1018–1028. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1700175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Burkhard P., Stetefeld J., Strelkov S.V. Coiled coils: A highly versatile protein folding motif. Trends Cell Biol. 2001;11:82–88. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)01898-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tanos B.E., Yang H.J., Soni R., Wang W.J., Macaluso F.P., Asara J.M., Tsou M.F. Centriole distal appendages promote membrane docking, leading to cilia initiation. Genes Dev. 2013;27:163–168. doi: 10.1101/gad.207043.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Joo K., Kim C.G., Lee M.S., Moon H.Y., Lee S.H., Kim M.J., Kweon H.S., Park W.Y., Kim C.H., Gleeson J.G., Kim J. CCDC41 is required for ciliary vesicle docking to the mother centriole. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013;110:5987–5992. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1220927110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ye X., Zeng H., Ning G., Reiter J.F., Liu A. C2cd3 is critical for centriolar distal appendage assembly and ciliary vesicle docking in mammals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014;111:2164–2169. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1318737111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ferrante M.I., Giorgio G., Feather S.A., Bulfone A., Wright V., Ghiani M., Selicorni A., Gammaro L., Scolari F., Woolf A.S., Sylvie O., Bernard L., Malcolm S., Winter R., Ballabio A., et al. Identification of the gene for oral-facial-digital type I syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2001;68:569–576. doi: 10.1086/318802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Coene K.L., Roepman R., Doherty D., Afroze B., Kroes H.Y., Letteboer S.J., Ngu L.H., Budny B., van Wijk E., Gorden N.T., Azhimi M., Thauvin-Robinet C., Veltman J.A., Boink M., Kleefstra T., et al. OFD1 is mutated in X-linked Joubert syndrome and interacts with LCA5-encoded lebercilin. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2009;85:465–481. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Webb T.R., Parfitt D.A., Gardner J.C., Martinez A., Bevilacqua D., Davidson A.E., Zito I., Thiselton D.L., Ressa J.H., Apergi M., Schwarz N., Kanuga N., Michaelides M., Cheetham M.E., Gorin M.B., et al. Deep intronic mutation in OFD1, identified by targeted genomic next-generation sequencing, causes a severe form of X-linked retinitis pigmentosa (RP23) Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012;21:3647–3654. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Irie S., Sanuki R., Muranishi Y., Kato K., Chaya T., Furukawa T. Rax homeoprotein regulates photoreceptor cell maturation and survival in association with Crx in the postnatal mouse retina. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2015;35:2583–2596. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00048-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Itoh Y., Moriyama Y., Hasegawa T., Endo T.A., Toyoda T., Gotoh Y. Scratch regulates neuronal migration onset via an epithelial-mesenchymal transition-like mechanism. Nat. Neurosci. 2013;16:416–425. doi: 10.1038/nn.3336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kozuka T., Omori Y., Watanabe S., Tarusawa E., Yamamoto H., Chaya T., Furuhashi M., Morita M., Sato T., Hirose S., Ohkawa Y., Yoshimura Y., Hikida T., Furukawa T. miR-124 dosage regulates prefrontal cortex function by dopaminergic modulation. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:3445. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-38910-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ueno A., Omori Y., Sugita Y., Watanabe S., Chaya T., Kozuka T., Kon T., Yoshida S., Matsushita K., Kuwahara R., Kajimura N., Okada Y., Furukawa T. Lrit1, a retinal transmembrane protein, regulates selective synapse formation in cone photoreceptor cells and visual acuity. Cell Rep. 2018;22:3548–3561. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chaya T., Tsutsumi R., Varner L.R., Maeda Y., Yoshida S., Furukawa T. Cul3-Klhl18 ubiquitin ligase modulates rod transducin translocation during light-dark adaptation. EMBO J. 2019;38 doi: 10.15252/embj.2018101409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Omori Y., Kubo S., Kon T., Furuhashi M., Narita H., Kominami T., Ueno A., Tsutsumi R., Chaya T., Yamamoto H., Suetake I., Ueno S., Koseki H., Nakagawa A., Furukawa T. Samd7 is a cell type-specific PRC1 component essential for establishing retinal rod photoreceptor identity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2017;114:E8264–E8273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1707021114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sugiyama T., Yamamoto H., Kon T., Chaya T., Omori Y., Suzuki Y., Abe K., Watanabe D., Furukawa T. The potential role of Arhgef33 RhoGEF in foveal development in the zebra finch retina. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:21450. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-78452-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chaya T., Matsumoto A., Sugita Y., Watanabe S., Kuwahara R., Tachibana M., Furukawa T. Versatile functional roles of horizontal cells in the retinal circuit. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:5540. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-05543-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Watanabe S., Sanuki R., Ueno S., Koyasu T., Hasegawa T., Furukawa T. Tropisms of AAV for subretinal delivery to the neonatal mouse retina and its application for in vivo rescue of developmental photoreceptor disorders. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kubo S., Yamamoto H., Kajimura N., Omori Y., Maeda Y., Chaya T., Furukawa T. Functional analysis of Samd11, a retinal photoreceptor PRC1 component, in establishing rod photoreceptor identity. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:4180. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-83781-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are contained in the manuscript.