Abstract

This cross-sectional study examines prostate cancer recommendations among US cancer centers to identify differences from clinical practice guidelines.

The US Preventive Services Task Force, American Cancer Society, and American Urological Association recommend that men at average risk engage in shared decision-making with their physicians regarding the decision to start prostate cancer screening with prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing at age 50 or 55 years, and most recommend discontinuing screening at age 70 years or in men with fewer than 10 years of life expectancy.1,2,3 These recommendations reflect evidence that PSA screening has both benefits and harms. Screening may reduce the incidence of metastatic disease, and possibly prostate cancer–specific mortality, but there is no clear evidence that screening decreases all-cause mortality. Potential harms include false-positive results, psychological effects, biopsy complications, and treatment sequelae for overdiagnosed or indolent tumors.1,2,3,4

We examined prostate cancer screening recommendations of US cancer centers, hypothesizing that some may differ from clinical practice guidelines. While public recommendations of cancer centers may not necessarily represent their clinical practices, the extent to which public recommendations align with national guidelines is important because they provide physicians and the public with guidance regarding screening.

Methods

In this cross-sectional study, we reviewed PSA screening recommendations on the public websites of 1119 US cancer centers accredited by the Commission on Cancer, of which 64 were National Cancer Institute (NCI) designated, focusing on age, shared decision-making, and potential harms. Comparisons to US Preventive Services Task Force, American Cancer Society, and American Urological Association national guidelines were made using 2-tailed Fisher test with a statistical significance of α < .05. This study was deemed exempt from review by the Weill Cornell institutional review board because it was not human participant research. Data were analyzed from January to June 2021.

Results

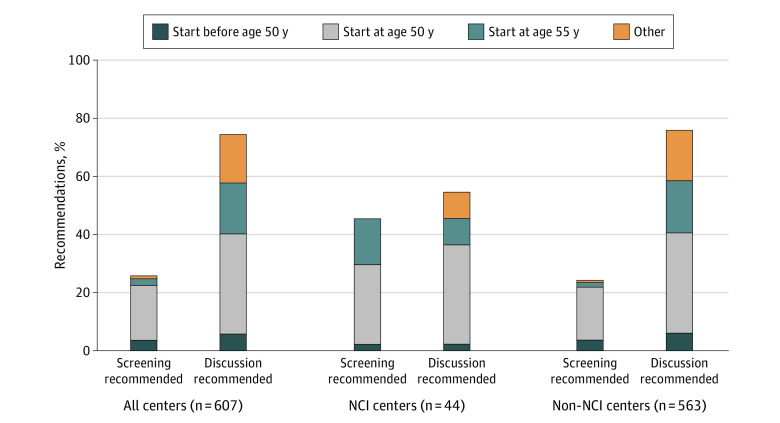

Of 607 centers providing recommendations for prostate screening, 451 (74%) recommended that men discuss screening with health care professionals, in accordance with national guidelines that recommend shared decision-making. Of these, 209 centers (34%) recommended discussion at 50 years of age and 106 (17%) at 55 years of age (Figure). Contrary to national guidelines, 156 centers (26%) recommended that all men universally initiate screening: 22 (4%) recommended starting before 50 years of age, 114 (19%) at 50 years of age, and 16 (3%) at 55 years of age. Of the centers providing recommendations, 476 (78%) did not specify an upper age limit at which to stop screening. The NCI-designated centers were less likely than non–NCI-designated centers to recommend shared decision-making and more likely to recommend universal screening without discussion (46% vs 24%, respectively; P = .009; Figure). Potential harms of screening were acknowledged by 229 centers (38%), of which 116 (19%) detailed specific risks (Table).

Figure. Prostate Cancer Screening Recommendations Among National Cancer Institution (NCI)-Designated and Non–NCI-Designated Cancer Centers.

Bars compare differences in prostate cancer screening recommendations (whether to universally start screening or discuss screening) across all centers and according to NCI designation.

Table. Details of Prostate Cancer Screening Risks as Specified on Websites of US Cancer Centers.

| Risks of screening mentioned | No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| All centers (n = 607) | NCI-designated centers (n = 44) | Non–NCI-designated centers (n = 563) | |

| Overdiagnosis, overtreatment, or unnecessary treatment | 56 (9.2) | 15 (34.1) | 41 (7.3) |

| False-positive results | 47 (7.7) | 4 (9.1) | 43 (7.6) |

| False-negative results | 13 (2.1) | 2 (4.6) | 11 (2.0) |

| States but does not specify risks | 113 (18.6) | 4 (9.1) | 109 (19.4) |

| States that there are no risks | 1 (0.2) | 1 (2.3) | 0 |

| No discussion of risks | 377 (62.1) | 18 (40.9) | 359 (63.8) |

Abbreviation: NCI, National Cancer Institute.

Discussion

Prostate-specific antigen screening does not reduce all-cause mortality in men, and screening carries risks from biopsies and treatment of overdiagnosed tumors, including risks to urinary, sexual, and bowel function.1,2 In contrast with national society guidelines that advise men (ages 50 or 55 to 70 years) to discuss screening risks and benefits with their physician, many US cancer centers (26%) recommend that all men universally receive PSA screening (using language such as “annual prostate screening is recommended for men beginning at age 50 years”), without advising shared decision-making. Most centers (62%) do not discuss screening risks on their websites.

A limitation of this study is that the public recommendations of cancer centers may not reflect their clinical practices. Nevertheless, the divergence between these recommendations and national society guidelines highlights the need to encourage shared decision-making for men considering screening. These findings are similar to the language used by many centers regarding lung cancer screening, generally emphasizing screening benefits more than potential harms and rarely recommending shared decision-making.5 Because clinical practice guidelines do not make specific recommendations regarding whether men at potentially higher risk owing to family history or race and ethnicity should consider earlier screening, the present analysis was unable to examine this.

The pattern of recommendations for PSA screening differs markedly from recommendations around screening mammography provided by breast cancer centers, which diverge from national society guidelines in more than 80% of cases: the majority of centers advise women to undergo earlier, more frequent screening than guidelines.6 The differences between PSA and mammography screening recommendations illuminate differences in how cancer centers advise men and women considering cancer screening and suggest further exploration of how recommendations differ across sex and cancer.

References

- 1.Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Owens DK, et al. ; US Preventive Services Task Force . Screening for prostate cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2018;319(18):1901-1913. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.3710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolf AM, Wender RC, Etzioni RB, et al. ; American Cancer Society Prostate Cancer Advisory Committee . American Cancer Society guideline for the early detection of prostate cancer: update 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60(2):70-98. doi: 10.3322/caac.20066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carter HB, Albertsen PC, Barry MJ, et al. Early detection of prostate cancer: AUA Guideline. J Urol. 2013;190(2):419-426. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.04.119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schröder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ, et al. ; ERSPC Investigators . Screening and prostate cancer mortality: results of the European Randomised Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) at 13 years of follow-up. Lancet. 2014;384(9959):2027-2035. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60525-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clark SD, Reuland DS, Enyioha C, Jonas DE. Assessment of lung cancer screening program websites. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(6):824-830. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel NS, Lee M, Marti JL. Assessment of screening mammography recommendations by breast cancer centers in the US. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(5):717-719. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.0157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]