Abstract

The effects of probenecid, an anion transport inhibitor, on the renal excretion mechanism of a new anionic carbapenem, DA-1131, were investigated after a 1-min intravenous infusion of DA-1131 at 100 mg/kg of body weight to rabbits and 50 mg/kg to rats with or without probenecid at 50 mg/kg for both species. In control rabbits, the renal clearance (CLR) of DA-1131 and the glomerular filtration rate based on creatinine clearance (CLCR) were 6.14 ± 2.09 and 2.26 ± 0.589 ml/min/kg, respectively. When considering the less than 10% plasma protein binding of DA-1131 in rabbits, renal tubular secretion of DA-1131 was observed in rabbits. The CLR of DA-1131 (3.87 ± 0.543 ml/min/kg) decreased significantly with treatment with probenecid in rabbits, indicating that the renal tubular secretion of DA-1131 was inhibited by probenecid. However, in control rats, the CLR of DA-1131 (5.80 ± 1.94 ml/min/kg) was comparable to the CLCR (4.29 ± 1.64 ml/min/kg), indicating that DA-1131 was mainly excreted by glomerular filtration in rats. Therefore, it could be expected that the CLR of DA-1131 could not be affected by treatment with probenecid in rats; this was proved by a similar CLR of DA-1131 with treatment with (6.93 ± 0.675 ml/min/kg) or without (5.80 ± 1.94 ml/min/kg) probenecid. Therefore, the renal secretion of DA-1131 is a factor in rabbits but is not a factor in rats.

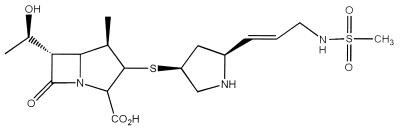

DA-1131, (1R, 5S, 6S) − (2S, 4S)-2-[(E)-3-methansulfonylamino - 1 - propenyl]pyrrolidine - 4 - ylthiol - 6 - [(R) - 1 - hydroxyethyl] -1-methyl-1-carbapen-2-em-3-carboxylic acid (Fig. 1), is a new anionic carbapenem antibiotic. DA-1131 has a broad antibacterial spectrum for both gram-positive and gram-negative organisms (12); DA-1131 is more active than imipenem-cilastatin and meropenem against Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Enterobacter cloacae, Proteus mirabilis, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Judging from the maximum velocity-to-Michaelis-Menten constant (Vmax/Km) ratios, DA-1131 showed relatively greater resistance than imipenem and meropenem to mouse, rat, rabbit, dog, and human renal dehydropeptidase I (DHP-I) (unpublished data); especially, the ratio of DA-1131 in the rabbit DHP-I was 1.5 and 4.3 times smaller than those of imipenem and meropenem, respectively. The Vmax/Km ratios of DA-1131, imipenem, and meropenem in human DHP-I were 1.43, 6.54, and 2.42, respectively. Therefore, meropenem is more stable than imipenem against human DHP-I but is less stable than DA-1131. DA-1131 is also resistant to degradation by various types of β-lactamases (13). DA-1131 is now being evaluated in a preclinical study.

FIG. 1.

Chemical structure of DA-1131.

The high-performance liquid chromatographic (HPLC) analysis of DA-1131 in biological fluids (20), stability, tissue metabolism, tissue distribution, and blood partition of DA-1131 (15), pharmacokinetics of DA-1131 in animals (19), interspecies pharmacokinetic scaling of DA-1131 (17), and the pharmacokinetics of DA-1131 in rats with uranyl nitrate-induced acute renal failure (21), in rats with alloxan-induced diabetes mellitus (18), and in rabbits with endotoxin-induced pyrexia (16) have been reported by our laboratories. In a previous study (19), the plasma protein binding of DA-1131 in rats and rabbits was less than 10%. The renal clearance (CLR) of DA-1131 (5.14 to 5.62 ml/min/kg) after intravenous (i.v.) administration of the drug at 20 to 200 mg/kg of body weight to rabbits (19) was higher than the reported creatinine clearance (CLCR) in rabbits, 3.12 ml/min/kg (5), indicating that active renal secretion of the drug was observed in rabbits. The CLR of DA-1131 (5.63 to 6.80 ml/min/kg) after i.v. administration of the drug at 50 to 500 mg/kg to rats (19) was slightly higher than the reported CLCR, 5.24 ml/min/kg (5), in rats, indicating that renal tubular secretion of the drug was not considerable in rats.

In the several studies that have been conducted with other carbapenem antibiotics, imipenem and meropenem were reported to be eliminated almost exclusively by the kidney through both glomerular filtration and tubular secretion (1, 8). Probenecid, an anion transport inhibitor, increased the half-lives of imipenem and meropenem by 30% or more due to the inhibition of tubular secretion of the drugs (1, 6, 7).

The purpose of this paper is to report on the effects of probenecid on the renal excretion mechanism of DA-1131 in rats and rabbits.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals.

DA-1131 (as an HCl salt) was donated by the Research Laboratory of Dong-A Pharmaceutical Company (Yongin, Korea). Probenecid was a product of Sigma Chemical Company (St. Louis, Mo.). Ketamine was supplied by Yuhan Research Center of Yuhan Corporation (Kunpo, Korea). Other chemicals were of reagent grade or HPLC grade and were used without further purification.

Animals.

Male Sprague-Dawley rats of 8 weeks of age (weight, 270 to 310 g) were purchased from Charles River Company (Atsugi, Japan). Male New Zealand White rabbits (weight, 1.75 to 2.50 kg) were purchased from the Korea Laboratory of Animal Development (Seoul, Korea). The animals were housed in a light-controlled room kept at a temperature of 22 ± 1°C and a humidity of 55% ± 10% (College of Pharmacy, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea), with food (Samyang Company, Seoul, Korea) and tap water provided ad libitum.

Pretreatment of animals.

The carotid artery and the jugular vein of each rat were cannulated with polyethylene tubes (Clay Adams, Parsippany, N.J.) while the animals were under light ether anesthesia. Both cannulae were exteriorized to the dorsal side of the neck and terminated with a long silastic tube (Dow Corning, Midland, Mich.). Both silastic tubes were covered with a wire to allow free movement of the rat. The exposed areas were surgically sutured. Each rat was housed individually in a rat metabolic cage (Daejong Scientific Company, Seoul, Korea) and were allowed to recover from the anesthesia for 4 to 5 h before the commencement of the experiment. They were not restrained at any time during the study. Heparinized 0.9% NaCl injectable solution (20 U/ml), 0.3 ml, was used to flush each cannula to prevent blood clotting.

Each rabbit was anesthetized with 50 to 100 mg of ketamine (50 mg/ml) given i.v. via the ear vein, and the carotid artery and the jugular vein were catheterized with a silastic tube (Dow Corning). Each cannula terminated in a three-way stopcock. The exposed areas were surgically sutured. Each rabbit was restrained individually in a rabbit cage during the entire experimental period and was allowed to recover from anesthesia for 4 to 5 h before the commencement of the experiment. Urine samples were collected via a pediatric Foley catheter (5 French; Sewon Company, Seoul, Korea) introduced into the urinary bladder. Approximately 3-ml aliquots of the heparinized 0.9% NaCl injectable solution were used to flush each cannula.

i.v. administration of DA-1131 with or without probenecid to rabbits and rats.

Probenecid (dissolved in 0.5 N NaOH and then adjusted to pH 7.4 with saturated KH2PO4) (23), 50 mg/kg, was infused over 1 min via the jugular vein (total injection volume, approximately 1 ml) of the rabbits (treatment I; n = 6) a half hour before the i.v. infusion of DA-1131. The same volume of 0.9% NaCl injectable solution was infused into control rabbits (treatment II; n = 9). DA-1131 (DA-1131 as an HCl salt was dissolved in 0.9% NaCl injectable solution), 100 mg/kg, was administered intravenously over 1 min via the jugular vein of each rabbit in both groups. The total injection volume was approximately 1 ml. Approximately 0.25 ml of blood was collected via the carotid artery at 0 (to serve as a control), 1 (at the end of infusion), 5, 15, 30, 45, 60, 90, 120, 180, 240, and 360 min after the i.v. administration of DA-1131. Approximately 3 ml of the heparinized 0.9% NaCl injectable solution was used to flush each cannula immediately after each blood sampling. Blood samples were centrifuged immediately to reduce or minimize the potential “blood storage effect” (the change in the plasma DA-1131 concentration due to the time that elapsed between collection and centrifugation of the blood sample mainly due to degradation) of DA-1131 in plasma (15). A 50-μl aliquot of each plasma sample was stored in a −70°C freezer (Revco ULT 1490 D-N-S; Western Mednics, Asheville, N.C.) until HPLC analysis of DA-1131 (20). At the end of 8 h, the urinary bladder was rinsed twice with 20 ml of distilled water and 20 to 40 ml of air to ensure complete recovery of the urine. The rinsings were combined with the urine sample. After measuring the exact volume of the combined urine sample, two 0.1-ml aliquots of the combined urine sample were stored in a −70°C freezer (Revco ULT 1490 D-N-S) until HPLC analysis of DA-1131 (20) and the measurement of the creatinine level. At the same time, as much blood as possible was collected via the carotid artery and each rabbit was killed. After centrifugation, an aliquot (1 ml) of plasma sample was stored in a −70°C freezer (Revco ULT 1490 D-N-S) for measurement of the creatinine level.

Probenecid (the same solution used in rabbits), 50 mg/kg, was infused over 1 min via the jugular vein (total injection volume, approximately 1 ml) of the rats (treatment III; n = 10) a half hour before the i.v. infusion of DA-1131. The same volume of 0.9% NaCl injectable solution was infused into control rats (treatment IV; n = 14). DA-1131 (the same solution used in rabbits), 50 mg/kg, was administered intravenously over 1 min via the jugular vein of each rat in both groups. The total injection volume was approximately 1 ml. Approximately 0.12 ml of blood was collected via the carotid artery at 0 (to serve as a control), 1 (at the end of infusion), 5, 15, 30, 45, 60, 90, 120, 180, 240, and 360 min after the i.v. administration of DA-1131. At the end of 8 h, the metabolic cage was rinsed with 20 ml of distilled water and the rinsings were combined with the urine sample. At the same time, as much blood as possible was collected via the carotid artery and each rat was killed by cervical dislocation. After centrifugation, plasma was collected for measurement of the creatinine level. Blood and urine samples were handled similarly to those in the studies with rabbits.

HPLC assay and measurement of creatinine levels.

DA-1131 in biological samples was analyzed within 7 days by the previously reported HPLC method developed in our laboratories (17). The mobile phase, 0.015 M KH2PO4 and acetonitrile (9:1; vol/vol) with a pH of 5.0, was run through a reversed-phase column at a flow rate of 0.8 ml/min, and the column effluent was monitored with a UV detector set at 300 nm. The retention time of DA-1131 was approximately 8.0 min. The detection limits of DA-1131 in human plasma and urine and in rat tissue homogenate were 0.1, 0.5, and 0.1 μg/ml, respectively. The mean within-day coefficients of variation of DA-1131 in human plasma and urine were 2.85% (range, 1.76 to 5.04%) and 2.85% (range, 1.65 to 4.75%), respectively. The mean between-day coefficients of variation for the analysis of the same samples on 3 consecutive days were 2.30 and 4.29% in human plasma and urine, respectively.

The concentrations of creatinine in the plasma and urine of rats and rabbits were determined by Jaffe’s picrate method (without the deproteinization kinetic method) with a Hitachi 747 Automatic Analyzer (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan).

Pharmacokinetic analysis.

The total area under the plasma concentration-time curve (AUC) from time zero to time infinity (AUC0–∞) was calculated by the trapezoidal rule-extrapolation method (14); this method uses the logarithmic trapezoidal rule recommended by Chiou (2) for calculation of the area during the phase of a declining level in plasma and the linear trapezoidal rule for the phase of a rising level in plasma. The area from the last datum point to infinity was estimated by dividing the last measured concentration in plasma by the terminal rate constant.

A standard method (11) was used to calculate the following pharmacokinetic parameters: the time-averaged total body clearance (CL), the area under the first moment of the plasma concentration-time curve (AUMC), the mean residence time (MRT), the apparent volume of distribution at steady state (VSS), and the time-averaged CLR and nonrenal clearance (CLNR) (14). The following equations were used: CL = dose/AUC, AUMC =  t Cpdt, MRT = AUMC/AUC, VSS = CL MRT, CLR = XU(∞)/AUC, and CLNR = CL − CLR, where Cp is the concentration of DA-1131 in plasma at time t and XU(∞) is the amount of DA-1131 excreted in urine up to time infinity (this was assumed to be equal to the total amount excreted in 8 h, since DA-1131 was present at a level below the detection limit in the urine collected thereafter).

t Cpdt, MRT = AUMC/AUC, VSS = CL MRT, CLR = XU(∞)/AUC, and CLNR = CL − CLR, where Cp is the concentration of DA-1131 in plasma at time t and XU(∞) is the amount of DA-1131 excreted in urine up to time infinity (this was assumed to be equal to the total amount excreted in 8 h, since DA-1131 was present at a level below the detection limit in the urine collected thereafter).

The mean values of CL, CLR, and CLNR (4), VSS (3), and terminal half-life (t1/2) (9) were calculated by the harmonic mean method.

The glomerular filtration rates in rats and rabbits were estimated by measuring the CLCR. CLCR was calculated by dividing the total amounts of creatinine excreted in urine over 8 h by the AUC of creatinine from time zero to 8 h (AUC0–8; (the concentration of creatinine in plasma was measured 8 h after the administration of the i.v. dose), assuming that the kidney function was stable during the 8-h experimental period.

Statistical analysis.

A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant by the t test between two means for unpaired data. All data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation.

RESULTS

Pharmacokinetics of DA-1131 after i.v. administration to rabbits.

After i.v. administration to rabbits, the plasma DA-1131 concentrations declined rapidly for both treatments (Fig. 2), with mean t1/2s of 20.1 and 17.2 min for treatments I and II, respectively (Table 1). The plasma DA-1131 concentrations were significantly higher in treatment I than those in treatment II (Fig. 2), and this resulted in a significant increase in the AUC (13,900 versus 7,980 μg · min/ml), AUMC (391,000 versus 118,000 μg · min2/ml), and MRT (27.9 versus 14.4 min) for DA-1131 in treatment I (Table 1). The CL (7.21 versus 12.5 ml/min/kg), CLR (3.87 versus 6.14 ml/min/kg), and CLNR (3.10 versus 5.86 ml/min/kg) of DA-1131 were significantly slower in treatment I (Table 1). However, the VSS and t1/2 of DA-1131 and the total amount of unchanged drug excreted in urine over 8 h (XU0–8) were not significantly different between the two treatments (Table 1).

FIG. 2.

Mean arterial plasma concentration-time profiles of DA-1131 after a 1-min i.v. infusion of the drug at 100 mg/kg without (○; n = 9) or with (•; n = 6) probenecid at 50 mg/kg to rabbits. Bars represent standard deviations. ∗∗, P < 0.01; ∗∗∗, P < 0.001.

TABLE 1.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of DA-1131 after a 1-min i.v. infusion of the drug at 100 mg/kg to rabbits with (treatment I) or without (treatment II) the administration of probenecid at 50 mg/kga

| Parameter | Treatment I (n = 6) | Treatment II (n = 9) |

|---|---|---|

| t1/2 (min) | 20.1 ± 7.65 | 17.2 ± 5.19 |

| AUC (μg · min/ml)b | 13,900 ± 1,510 | 7,980 ± 2,000 |

| AUMC (μg · min2/ml)b | 391,000 ± 92,500 | 118,000 ± 47,300 |

| MRT (min)b | 27.9 ± 4.01 | 14.4 ± 3.79 |

| CL (ml/min/kg)c | 7.21 ± 0.782 | 12.5 ± 4.29 |

| CLR (ml/min/kg)c | 3.87 ± 0.543 | 6.14 ± 2.09 |

| CLNR(ml/min/kg)c | 3.10 ± 0.911 | 5.86 ± 2.85 |

| CLCR (ml/min/kg)c | 3.54 ± 1.23 | 2.26 ± 0.589 |

| VSS (ml/kg) | 200 ± 21.7 | 176 ± 47.5 |

| XU 0–8 (% of i.v. dose) | 54.8 ± 9.28 | 50.3 ± 9.80 |

Values are means ± standard deviations.

P < 0.001.

P < 0.05.

Pharmacokinetics of DA-1131 after i.v. administration to rats.

After i.v. administration to rats, the plasma DA-1131 concentrations declined rapidly for both treatments (Fig. 3), with mean t1/2s of 14.5 and 15.7 min for treatments III and IV, respectively (Table 2). The plasma DA-1131 concentrations were not significantly different between the two treatments (Fig. 3). The pharmacokinetic parameters of DA-1131 listed in Table 2 were not significantly different between treatments III and IV.

FIG. 3.

Mean arterial plasma concentration-time profiles of DA-1131 after a 1-min i.v. infusion of the drug at 50 mg/kg without (○; n = 14) or with (•; n = 10) probenecid at 50 mg/kg to rats. Bars represent standard deviations. Each point was not significantly (P < 0.05) different.

TABLE 2.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of DA-1131 after a 1-min i.v. infusion of the drug at 50 mg/kg to rats with (treatment III) or without (treatment IV) the administration of probenecid at 50 mg/kga

| Parameter | Treatment III (n = 10) | Treatment IV (n = 14) |

|---|---|---|

| t1/2 (min) | 14.5 ± 1.66 | 15.7 ± 2.47 |

| AUC (μg · min/ml) | 3,850 ± 272 | 4,000 ± 951 |

| AUMC (μg · min2/ml) | 46,500 ± 8,020 | 48,700 ± 14,600 |

| MRT (min) | 12.0 ± 1.65 | 12.2 ± 2.32 |

| CL (ml/min/kg) | 13.0 ± 0.903 | 12.5 ± 3.09 |

| CLR (ml/min/kg) | 6.93 ± 0.675 | 5.80 ± 1.94 |

| CLNR(ml/min/kg) | 5.99 ± 0.653 | 6.26 ± 2.05 |

| CLCR (ml/min/kg) | 4.97 ± 2.13 | 4.29 ± 1.64 |

| VSS (ml/kg) | 154 ± 20.4 | 147 ± 53.8 |

| XU 0–8 (% of i.v. dose) | 53.6 ± 3.70 | 48.8 ± 8.71 |

Values are means ± standard deviations.

DISCUSSION

The significant increases in AUC (74% increase) and AUMC (231% increase) for DA-1131 in treatment I were due to the significantly slower CL of DA-1131 (42% decrease) in treatment I (Table 1). In treatment I, the compensatory changes in the clearances (CLR and CLNR) of DA-1131 were not observed; both the CLR (37% decrease) and the CLNR (47% decrease) of DA-1131 were significantly slower than those in treatment II (Table 1). Therefore, the significantly slower CL of DA-1131 in treatment I could be due to the significantly slower CLR and CLNR of DA-1131 in treatment I (Table 1). In treatment II, the glomerular filtration rate based on the CLCR was 2.26 ml/min/kg (Table 1). When considering the level of plasma protein binding of DA-1131 in rabbits (less than 10% [16]) and the CLR of DA-1131 in treatment II (6.14 ml/min/kg [Table 1]), renal tubular secretion of DA-1131 was observed in control rabbits. However, in treatment I, the CLCR of DA-1131 was 3.54 ml/min/kg and the CLR of DA-1131 (3.87 ml/min/kg) was significantly slower than that in treatment II (Table 1), indicating that the renal tubular secretion of DA-1131 was inhibited by probenecid. The significantly slower CLNR of DA-1131 in treatment I could be due to the considerably slower metabolism of DA-1131 in the rabbit kidney, possibly by DHP-I; this could be at least partly due to the increased plasma DA-1131 concentrations (Fig. 2) from the inhibition of the active renal secretion of the drug by probenecid. The existence of a Michaelis-Menten type of hydrolysis of DA-1131 in rabbit kidney DHP-I was studied; the Vmax and Km of DA-1131 were 3.45 units/mg and 0.63 mM, respectively (unpublished data). The slower CLNR of DA-1131 obtained after treatment with probenecid was also obtained after treatment with meropenem (1), imipenem (6), T-3761, a novel fluoroquinolone (10), and diprophylline (22).

In treatment IV, the CLR of DA-1131 (5.80 ml/min/kg) in rats was not significantly different from the CLCR (4.29 ml/min/kg; Table 2), indicating that DA-1131 was excreted in urine mainly via glomerular filtration in rats. Therefore, it was expected that the CLR of DA-1131 could not be affected by treatment with probenecid, and this was proved by the insignificant differences in the CLR of DA-1131 (6.93 versus 5.80 ml/min/kg) between treatments III and IV (Table 2). Note that the percentage of the i.v. dose of DA-1131 excreted in bile as unchanged drug over 8 h after i.v. administration of the drug at 200 mg/kg to six rats was very low; the value was 1.76% (19). The data presented above indicate that the contribution of the biliary excretion of DA-1131 to CLNR of DA-1131 in rats seemed to be minor. Therefore, the CLNR listed in Table 2 could represent the metabolic clearance of DA-1131 in rats.

In conclusion, the renal tubular secretion of DA-1131 was inhibited by probenecid in rabbits, but the effect of probenecid was negligible in rats. Therefore, the renal secretion of DA-1131 is a factor in rabbits but is not a factor in rats.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by the Korea Ministry of Science and Technology (HAN Project), 1995–1996.

We thank Hae-ran Moon (Green Cross Reference Laboratory, Seoul, Korea) for the measurement of creatinine levels in plasma and urine.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bax, R. P., W. Bastain, A. Featherstone, D. M. Wilkinson, M. Hutchison, and S. J. Haworth. 1989. The pharmacokinetics of meropenem in volunteers. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 24(Suppl. A):311–320. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Chiou W L. Critical evaluation of potential error in pharmacokinetic studies using the linear trapezoidal rule method for the calculation of the area under the plasma level-time curve. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 1978;6:539–546. doi: 10.1007/BF01062108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chiou W L. New calculation method for mean apparent drug volume of distribution and application to rationale dosage regimens. J Pharm Sci. 1979;68:1067–1069. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600680843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chiou W L. New calculation method of mean total body clearance of drugs and its application to dosage regimens. J Pharm Sci. 1980;69:90–91. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600690125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davies B, Morris T. Physical parameters in laboratory animals and humans. Pharm Res. 1995;7:1093–1095. doi: 10.1023/a:1018943613122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drusano, G. L. 1986. An overview of the pharmacology of imipenem/cilastatin. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 18(Suppl. E):79–92. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Drusano, G. L., and H. C. Standiford. 1985. Pharmacokinetic profile of imipenem/cilastatin in normal volunteers. Am. J. Med. 78(Suppl. 6A):47–53. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Drusano G L, Standiford H C, Bustamante C, Forrest A, Rivera G, Leslie J, Tatem B, Delaportas D, MacGregor R R, Schimpff S C. Multiple-dose pharmacokinetics of imipenem/cilastatin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1984;26:715–721. doi: 10.1128/aac.26.5.715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eatman F B, Colburn W A, Boxenbaum H G, Posmanter H N, Weinfeld R E, Ronfeld R, Weissman L, Moore J D, Gibaldi M, Kaplan S A. Pharmacokinetics of diazepam following multiple dose oral administration to healthy human subjects. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 1977;5:481–494. doi: 10.1007/BF01061729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fukuda Y, Muratani T, Takahata M, Fukuoka Y, Tasuda T, Watanabe Y, Narita H. Mechanism of renal excretion of T-3761, a novel fluoroquinolone agent, in rabbits. Jpn J Antibiot. 1995;48:649–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gibaldi M, Perrier D. Pharmacokinetics. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker, Inc.; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim G W, Chang M S, Lee K W, Chong Y S, Yang J. Abstracts of the Annual Meeting of the Korea Society of Applied Pharmacology. 1996. Comparative in vitro antibacterial activity of DA-1131, a new carbapenem antibiotic (I), abstr; p. 232. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim J Y, Kim G W, Choi S H, We J S, Park H S, Yang J. Abstracts of the Annual Meeting of the Korea Society of Applied Pharmacology. 1996. Renal dehydropeptidase-I (DHP-I) stability and pharmacokinetics of DA-1131, a new carbapenem antibiotic, abstr; p. 238. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim S H, Choi Y M, Lee M G. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of furosemide in protein-calorie malnutrition. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 1993;21:1–17. doi: 10.1007/BF01061772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim S H, Kim W B, Lee M G. Stability, tissue metabolism, tissue distribution, and blood partition of DA-1131, a new carbapenem. Res Commun Mol Pathol Pharmacol. 1995;90:347–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim S H, Kim W B, Lee M G. Pharmacokinetics of a new carbapenem, DA-1131, after intravenous administration to rabbits with endotoxin-induced pyrexia. Res Commun Pharmacol Toxicol. 1997;2:121–128. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim S H, Kim W B, Lee M G. Interspecies pharmacokinetic scaling of a new carbapenem, DA-1131, in mice, rats, rabbits, and dogs, and prediction of human pharmacokinetics. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 1998;19:231–235. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-081x(199805)19:4<231::aid-bdd96>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim S H, Kim W B, Lee M G. Pharmacokinetics of a new carbapenem, DA-1131, after intravenous administration to rats with alloxan-induced diabetes mellitus. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 1998;19:303–308. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-081x(199807)19:5<303::aid-bdd103>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim S H, Kwon J W, Lee M G. Pharmacokinetics and tissue distribution of a new carbapenem, DA-1131, after intravenous administration to mice, rats, rabbits, and dogs. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 1998;19:219–229. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-081x(199805)19:4<219::aid-bdd95>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim S H, Kwon J W, Yang J, Lee M G. Determination of a new carbapenem derivative, DA-1131, in plasma and urine by high-performance liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr Ser B. 1997;688:95–99. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(97)88060-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim S H, Shim H J, Kim W B, Lee M G. Pharmacokinetics of a new carbapenem, DA-1131, after intravenous administration to rats with uranyl nitrate-induced acute renal failure. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1217–1221. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.5.1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nadai M, Apichartpichean R, Hasegawa T, Nabeshima T. Pharmacokinetics and the effect of probenecid on the renal excretion mechanism of diprophylline. J Pharm Sci. 1992;81:1024–1027. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600811014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ram A, Glaubiger D, Ramu N P, Eldridge N, Blaschke T F. Probenecid inhibition of methotrexate excretion from cerebrospinal fluid in dogs. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 1978;6:389–397. doi: 10.1007/BF01062721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]