Abstract

Candida albicans is a fungus thought to be viable in the presence of a deficiency in sterol 14α-demethylation. We showed in a strain of this species that the deficiency, caused either by a mutation or by an azole antifungal agent, made the cells susceptible to growth inhibition by acetate included in the culture medium. Studies with a mutant demonstrated that the inhibition was complete at a sodium acetate concentration of 0.24 M (20 g/liter) and was evident even at a pH of 8, the latter result indicating the involvement of acetate ions rather than the undissociated form of acetic acid. In fluconazole-treated cells, sterol profiles determined by thin-layer chromatography revealed that the minimum sterol 14α-demethylation-inhibitory concentrations (MDICs) of the drug, thought to be the most important parameter for clinical purposes, were practically identical in the media with and without 0.24 M acetate and were equivalent to the MIC in the acetate-supplemented medium. The acetate-mediated growth inhibition of azole-treated cells was confirmed with two additional strains of C. albicans and four different agents, suggesting the possibility of generalization. From these results, it was surmised that the acetate-containing medium may find use in azole susceptibility testing, for which there is currently no method capable of measuring MDICs directly for those fungi whose viability is not lost as a result of sterol 14α-demethylation deficiency. Additionally, the acetate-supplemented agar medium was found to be useful in detecting reversions from sterol 14α-demethylation deficiency to proficiency.

Sterol 14α-demethylation (herein referred to as 14-demethylation) is the principal, if not sole, target for the action of the azole antifungal agents (16). It has also been widely assumed that 14-demethylation inhibition per se is responsible for the clinical efficacies of these agents. In Candida albicans, 14-demethylation deficiency makes the cells hypervulnerable to killing by phagocytes (5, 11) and to active oxygen species (15). Furthermore, a 14-demethylation-deficient C. albicans mutant has been shown to exhibit reduced virulence in an experimental animal infection model (8). Additionally, such mutants are incapable of hyphal growth (6, 12), a phenotype often assumed to be linked to virulence.

On the other hand, the relationship between 14-demethylation deficiency and cell viability is not simple. For Saccharomyces cerevisiae, 14-demethylation deficiency results in cell lethality under the condition of aerobiosis, which is suppressed by a compensatory mutation in sterol C5-desaturase (3). In contrast, cells of 14-demethylation-deficient C. albicans mutants seem to be viable even without the sterol C5-desaturase mutation (2, 3, 10, 12, 14), although rigorous proof by disruption of the 14-demethylase gene is yet to be produced. It is also known that a virtually complete inhibition of 14-demethylation is effected by an azole agent at its sub-MIC (12).

The above considerations lead us to believe that in the case of azoles, the parameter of clinical relevance is the minimum drug concentration required for 14-demethylation inhibition (to be referred to as MDIC, for minimum demethylation-inhibitory concentration) rather than the MIC. A practical problem posed by this situation is that there is no simple and reliable method for determining the MDIC of the azole agent. In the course of our work on physiologic properties of C. albicans cells incurring 14-demethylation deficiency, we noticed that the growth of such cells was selectively inhibited by acetate added to the culture medium, and we characterized the phenomenon in some detail to probe its utility in the measurement of MDIC. Judging from our results, reported herein, the acetate-mediated, 14-demethylation-dependent growth inhibition seems to have great potential for application to azole susceptibility testing.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

C. albicans strains.

The C. albicans strains used are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

C. albicans strains used

| Strain | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| KD14 | Serotype A; Lys− but otherwise wild type | 12 |

| KD4900 | 14-Demethylation-deficient derivative of KD14 | 12, 14 |

| KD4907 | 14-Demethylation-proficient revertant of KD4900 | 12 |

| KD4911 | 14-Demethylation-proficient revertant of KD4900 | This work |

| KD4912 | 14-Demethylation-proficient revertant of KD4900 | This work |

| KD4913 | 14-Demethylation-proficient revertant of KD4900 | This work |

| KD4914 | 14-Demethylation-proficient revertant of KD4900 | This work |

| KD4915 | 14-Demethylation-proficient revertant of KD4900 | This work |

| ATCC 10231 | Serotype A, wild type | R. D. Cannon |

| B59630 | Cdr1-overexpressing clinical isolate | F. C. Odds, references 1 and 9 |

Culture media and conditions.

Yeast extract-peptone-glucose broth (YEPG), which was used throughout the present study as the basal or reference medium, contained yeast extract (Difco) (10 g/liter), polypeptone (Nihon Pharmaceutical Co., Tokyo, Japan) (20 g/liter), and glucose (20 g/liter), with a final pH of 6.5. YEPG was supplemented with sodium acetate at 0.24 M (20 g/liter) (final pH, 6.7) (YEPG-Ac). When needed, the pH of YEPG or YEPG-Ac was changed within the range from 4.0 to 8.0 by addition of HCl or NaOH. For solid media (YEPG or YEPG-Ac agar), agar was added at 20 g/liter. Azole drugs were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide and added to sterile media; the final concentration of the solvent was 1% (vol/vol). Incubation was performed at 25 or 35°C; the latter temperature was used when azole drugs were involved, in accordance with the currently recommended routine for azole susceptibility testing (7). Liquid cultures were grown with shaking.

Agar plate assays of azole susceptibility.

Gradient plate assays were carried out on rectangular plates of YEPG or YEPG-Ac agar containing a concentration gradient of an azole agent; the plates were prepared as described previously (4). Inoculation was carried out through applying filter paper strips impregnated with log phase cultures of test strains in YEPG to the agar surface and then removing them. Agar diffusion assays were done by the disc method; the filter paper discs were prepared by addition of appropriate amounts of azoles dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide.

Analysis of cellular sterols.

Extraction of cellular lipids and thin-layer chromatography (TLC) on silica gel plates (Merck) were carried out as described previously (12). Identification of sterols was done by comparing the Rfs with the following reference values obtained in our previous work (12): 0.46, 0.53, and 0.59 for ergosterol, 4,14-methylated sterols, and 4,4′,14-methylated sterols (corresponding to Rf classes II, III, and IV as described in reference 12), respectively.

Chemicals.

Fluconazole (FLCZ) was donated by Pfizer Pharmaceuticals (Tokyo, Japan), ketoconazole (KCZ) and itraconazole (ITZ) were gifts from Janssen Research Foundation (Beerse, Belgium), and clotrimazole (CTZ) was provided by M. Niimi of Kagoshima University.

RESULTS

Acetate-mediated growth inhibition of 14-demethylation-deficient mutant.

We fortuitously noticed that C. albicans KD4900 could not grow in YEPG-Ac, which contained 0.24 M sodium acetate, while strains KD14 and KD4907 could (Fig. 1A). KD4900 was a 14-demethylation-deficient mutant derived from KD14 (references 12 and 14; see also Fig. 1B, lanes 1 and 2), while KD4907 was a 14-demethylation-proficient revertant spontaneously formed from KD4900 (12). These observations strongly suggested that 14-demethylation deficiency per se was responsible for the acetate-mediated growth inhibition in KD4900. The inhibition was evident at a sodium acetate concentration of as low as 0.12 M and was virtually complete at 0.24 M (Fig. 2). Sodium chloride was ineffective, even at a much higher concentration, indicating that the acetate and not the sodium was responsible for the inhibition (Fig. 2).

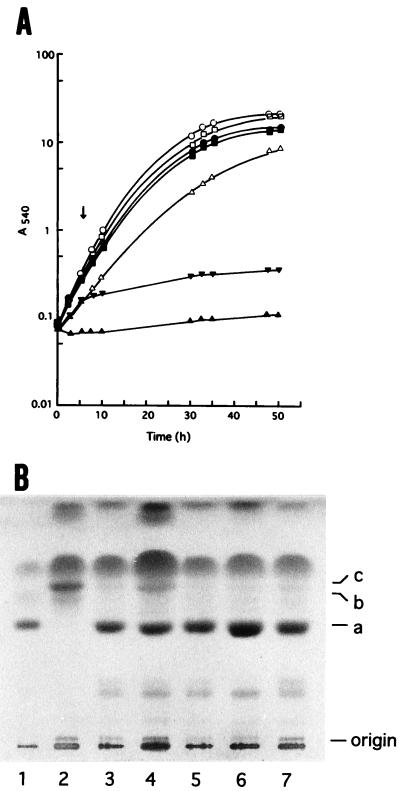

FIG. 1.

Growth and sterol profiles of 14-demethylation-proficient (KD14 and KD4907) and -deficient (KD4900) C. albicans strains. (A) Growth in YEPG-Ac (closed symbols) or YEPG (open symbols) at 25°C with shaking. ○ and •, KD14; ▵ and ▴, KD4900; ▾, KD4900 (acetate added at arrow); and □ and ■, KD4907. (B) TLC profiles of sterols. Lane 1, KD14; lane 2, KD4900; lanes 3 through 7, KD4911 through KD4915, respectively. Identification of sterols: a, ergosterol; b, 4,14-methylated sterols; c, 4,4′,14-methylated sterols.

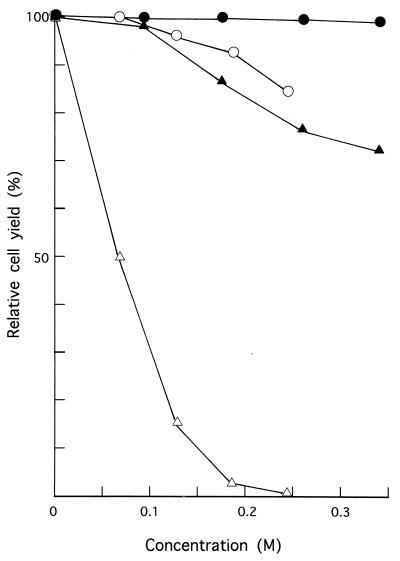

FIG. 2.

Effects of sodium acetate and NaCl on the growth of 14-demethylation-proficient (KD14) and -deficient (KD4900) cells. Cultures in YEPG supplemented with various concentrations of either salt were incubated with shaking at 25°C. Turbidities were measured after 48 h, when the control culture (KD14 in YEPG without supplement) had reached an early stationary phase, and values relative to that of the control were plotted. ○, KD14 with sodium acetate; •, KD14 with NaCl; ▵, KD4900 with sodium acetate; and ▴, KD4900 with NaCl.

Propionate and benzoate, both well known for their antifungal activities, also brought about similar selective inhibition at much lower concentration than acetate when added to YEPG broth, and the best discrimination values were achieved at around 25 and 5 mM, respectively. However, we did not study these two carboxylates further because their selectivity margins, reflecting their general toxicities to the fungal cell, were rather narrow (data not shown).

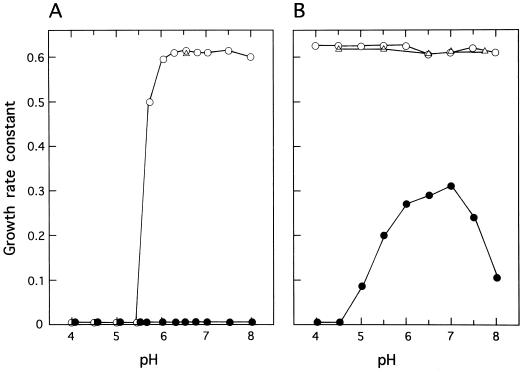

Effect of pH.

Tests were carried out for effect of pH on the growth in the range between 4.0 and 8.0. For KD14, acetate (0.24 M) affected growth little in the pH range between 5.5 and 8.0 but repressed it completely at a pH of 5.4 or lower; for KD4900, it totally inhibited growth over the whole pH range (Fig. 3). Hence, acetate discriminated between KD14 and KD4900 in the pH range from 5.5 to 8.0. Those pH profiles implied that the growth inhibition of KD14 was brought about only by the undissociated acetic acid present in significant amounts in the low pH range, whereas that of KD4900 was caused even by the dissociated acetate form.

FIG. 3.

Effect of pH on the growth of 14-demethylation-proficient (KD14 and KD4907) and -deficient (KD4900) cells in the presence or absence of acetate. Cultures in YEPG-Ac (A) or YEPG (B) at various pH values were shaken at 25°C, and the growth rate constant of each culture (the reciprocal of generation time, or h−1) is plotted against the medium pH. ○, KD14; •, KD4900; and ▵, KD4907.

Selection of 14-demethylation-proficient cells by acetate.

The selective growth inhibition in KD4900 was shown to provide a convenient means of selecting revertants from a 14-demethylation-deficient mutant. When late-stationary-phase cells of KD4900 grown in YEPG were plated on YEPG-Ac agar, colonies were formed with a frequency of ≈10−8;examination of five independent strains thus isolated (KD4911 through KD4915) for their sterol profiles showed that they were all proficient in 14-demethylation (Fig. 1B, lanes 3 through 7).

Acetate-mediated growth inhibition in azole-treated cells.

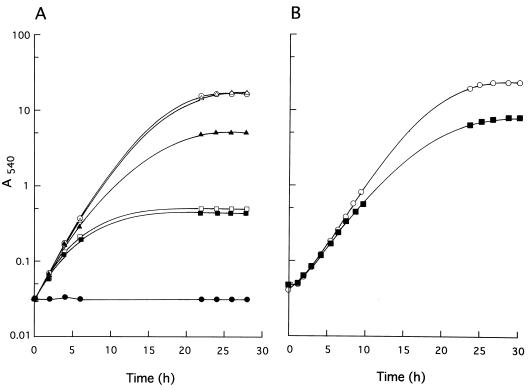

The above-described observations led us to expect that similar acetate-mediated growth inhibition should occur in cells incurring 14-demethylation inhibition but still growing in the presence of an azole drug. We tested this possibility with FLCZ and found that this was indeed the case. FLCZ severely inhibited the growth of KD14 cells in YEPG-Ac in a concentration-dependent manner, and saturation was achieved at 2.5 μg/ml (Fig. 4A). Only gradual cessation of growth, as opposed to an abrupt halt, was effected in YEPG-Ac, even at high drug concentrations of up to 50 μg/ml (data not shown), probably reflecting a progressive dilution of the preexisting membrane ergosterol by newly synthesized 14-methylated sterols. In contrast, only slight effect on the cell growth was observed in YEPG even at the FLCZ concentration of 10 μg/ml (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

Effect of FLCZ on the growth of KD14 cells. Cultures were shaken at 35°C in YEPG-Ac (A) or YEPG (B). FLCZ concentration: ○, 0; ▵, 0.1 μg/ml; ▴, 0.5 μg/ml; □, 2.5 μg/ml; ■, 10 μg/ml. •, KD4900 without FLCZ.

To confirm that the growth inhibition caused by FLCZ in YEPG-Ac was in fact a consequence of the replacement of cellular ergosterol by 14-methylated sterols, we looked at whether the degree of growth inhibition was correlated to that of 14-demethylation inhibition. In effect, the results showed such a correlation to exist. The lowest FLCZ concentration required for a complete inhibition of ergosterol formation (or 14-demethylation) in YEPG-Ac was 1.25 μg/ml (Fig. 5A), which may be considered to represent the MDIC under the conditions used. On the other hand, the final turbidity of the culture relative to that of the control (growth index) was 7% at the drug concentration of 2.5 μg/ml (Fig. 5A) and did not decrease any further at 5 μg/ml (data not shown), which is consistent with the results shown in Fig. 4. (Note that, due to the gradual growth cessation as seen in Fig. 4, the growth index of zero could not be attained.) We regard the concentration of 2.5 μg/ml as the MIC under the present experimental conditions, and we interpret these results as showing that the observed MDIC and MIC are very close, if not identical, to each other. Importantly, YEPG gave essentially the same sterol profiles as YEPG-Ac with respect to the concentration of FLCZ (Fig. 5B), indicating that acetate did not interfere with FLCZ with respect to 14-demethylation inhibition. The cell growth in YEPG was only moderately affected in the virtual absence of ergosterol formation at the FLCZ concentrations of 1.25 to 2.5 μg/ml (Fig. 5B; see also Fig. 4B).

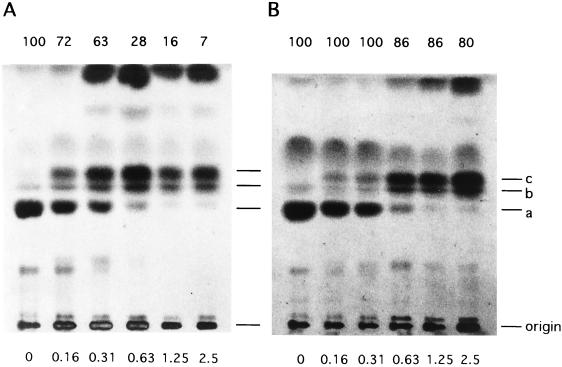

FIG. 5.

TLC profiles for sterols from KD14 cells grown in the presence of various concentrations of FLCZ. Cultures in YEPG-Ac (A) or YEPG (B) were shaken at 35°C for 48 h, the cell yields were assessed by turbidimetry, and the cells were subjected to sterol analysis. Figures below and above each lane are the FLCZ concentrations (μg/ml) and the relative cell yields (growth indices, percents), respectively. Identification of sterols: a, ergosterol; b, 4,14-methylated sterols; c, 4,4′,14-methylated sterols.

Demonstration of acetate effect with agar plates.

To further confirm the effect of acetate, we visualized it by means of the gradient-concentration plate and agar diffusion techniques. In so doing, we included two additional C. albicans strains (ATCC 10231 and B59630) as well as three other azoles (KCZ, ITZ, and CTZ) in the tests in order to probe the generality of the effect.

The results obtained with gradient-concentration plates were as follows. On YEPG (Fig. 6B, D, and F), all strains grew over the entire concentration range of each drug. On YEPG-Ac (Fig. 6A, C, and E), KD14 (lane 1) did not grow at all, ATCC 10231 (lane 2) grew only in zone I (with the lowest drug concentration) of plate A, and the azole-resistant mutant B59630 (lane 3) grew in all zones of the three plates. These results were apparently consistent with the acetate-mediated growth inhibition of 14-demethylation-deficient cells. To substantiate this, we examined cell samples taken from the YEPG agar plates for their sterol profiles. As expected, ergosterol was not detectable in the cells from those zones for which no growth occurred on the YEPG-Ac counterparts (Fig. 7).

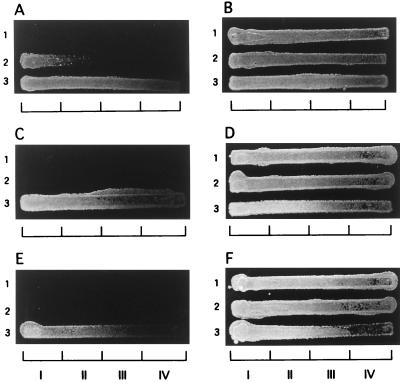

FIG. 6.

Growth of C. albicans strains on plates containing gradient azole concentration. (A) YEPG-Ac plus FLCZ, (B) YEPG plus FLCZ, (C) YEPG-Ac plus KCZ, (D) YEPG plus KCZ, (E) YEPG-Ac plus ITZ, and (F) YEPG plus ITZ. Gradients (from left to right): for FLCZ, 0 to 10 μg/ml; for KCZ, 0 to 0.1 μg/ml; and for ITZ, 0 to 0.1 μg/ml. Strains: 1, KD14; 2, ATCC 10231; 3, B59630. I, II, III, and IV are sampling zones (see also legend to Fig. 7.).

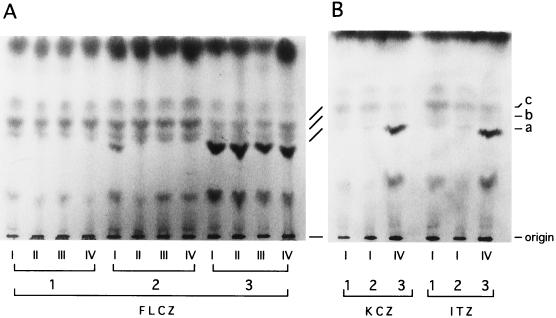

FIG. 7.

TLC profiles for sterols from cells grown on the YEPG plates containing gradient azole concentration shown in Fig. 6. (A) Cell samples from FLCZ-containing plate (plate B in Fig. 6); (B) cell samples from KCZ-containing plate (plate D in Fig. 6) and ITZ plate (plate F in Fig. 6). Lanes: 1, KD14; 2, ATCC 10231; 3, B59630; I, II, III, and IV, sampling zones.

In the diffusion plate assay, each inhibitory zone on YEPG-Ac agar was, also as expected, invariably larger than the counterpart on YEPG agar (Fig. 8).

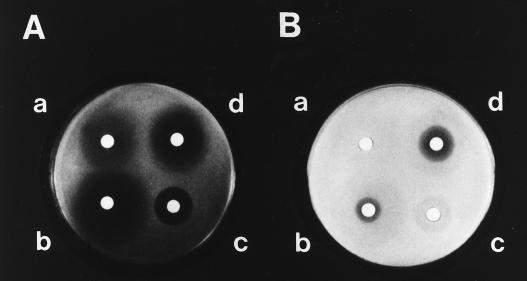

FIG. 8.

Demonstration by agar diffusion tests of acetate-mediated growth inhibition in azole-treated cells. An aliquot of a log-phase culture of KD14 in YEPG was poured onto a YEPG-Ac (A) or a YEPG (B) plate and removed by pipetting. After being dried, the plates received filter paper discs containing 100 μg of FLCZ (a) or 10 μg (each) of KCZ (b), ITZ (c), or CTZ (d) and were incubated at 35°C for 3 days.

DISCUSSION

It was corroboratively demonstrated by two independent methodologies, i.e., studies of mutants and inhibitor studies, that acetate caused growth inhibition in cells of the 14-demethylation-deficient C. albicans strain. In the 14-demethylation-proficient strain KD14, acetate brought about an elevation of the lower limit of growth pH (from ≤4.0 to 5.5), suggesting that undissociated acetic acid, thought to be capable of crossing the plasma membrane, may be responsible and that the resulting increase in the intracellular concentration of acetate could be somehow detrimental to the cell. By contrast, the 14-demethylation-deficient strain could not grow in the presence of acetate within the whole pH range tested, including alkaline pHs. This suggests that the membranes of 14-demethylation-deficient cells may be permeable not only to undissociated acetic acid but also to acetate ions. This is in accordance with our previous finding that such cells of C. albicans show increased sensitivity to a variety of water-soluble, structurally unrelated antifungal substances (13). The nature of the hypothetical toxicity of acetate is presently unknown, except that it is fungistatic rather than fungicidal (our unpublished results).

The acetate-mediated, 14-demethylation deficiency-dependent growth inhibition seems to have various applications. As verified in this work, the phenomenon provides a reliable method for detecting reversions from 14-demethylation deficiency to proficiency. Perhaps more importantly, it suggests the possibility of a simple and rational method for the azole susceptibility testing. For this purpose, MDIC rather than MIC is obviously relevant in 14-demethylation deficiency-tolerant fungi such as C. albicans, and a method capable of measuring MDIC is therefore needed. We showed that for KD14 the MDICs of FLCZ in YEPG-Ac and YEPG were practically identical to each other and very close to its MIC in YEPG-Ac (Fig. 5). If this observation can be generalized, YEPG-Ac should be an obvious candidate to meet this demand. Although not quite quantitative in nature and involving only a few additional C. albicans strains and azoles, the gradient plate assays provided results that appear to favor such generalization. Obviously, this problem should be addressed by performing more quantitative evaluation with many more fungal species and strains. In this connection, a point worthy of note is that there would be no problem, at least theoretically, in applying this method to MDIC determination for fungi which are intolerant to 14-demethylation deficiency, like S. cerevisiae. In those fungi, the MDIC and MIC of an azole agent would coincide, regardless of the presence or absence of acetate. In other words, acetate would probably make no interference and simply not be required in such cases. Experiments to test this prediction are under way in the authors’ laboratory.

Finally, it should be added that although it was not studied here in further detail, 14-demethylation deficiency-dependent growth inhibition was also seen with other carboxylates, i.e., propionate and benzoate. Moreover, our previous work has shown that a number of other structurally unrelated compounds are selectively toxic to 14-demethylation-deficient C. albicans cells (13). One should keep in mind the possibility that some of these substances might also be useful for azole susceptibility testing. In any event, it is hoped that the present report will ignite the more extensive work that is necessary for evaluating the utility of acetate-containing culture media in azole susceptibility testing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank F. C. Odds, Janssen Research Foundation, and R. D. Cannon, University of Otago, for providing us with fungus strains. Gifts of azole drugs from Pfizer Pharmaceuticals, Janssen Research Foundation, and M. Niimi are gratefully acknowledged. Thanks are also due to K. Sakai for general supportive services in the laboratory.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albertson G D, Niimi M, Cannon R D, Jenkinson H F. Multiple efflux mechanisms are involved in Candida albicans fluconazole resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2835–2841. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.12.2835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bard M, Lees N D, Barbuch R J, Sanglard D. Characterization of a cytochrome P450 deficient mutant of Candida albicans. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1987;147:794–800. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(87)91000-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bard M, Lees N D, Turi T, Craft D, Cofrin L, Barbuch R, Koegel C, Loper J C. Sterol synthesis and viability of erg11 (cytochrome P450 lanosterol demethylase) mutations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Candida albicans. Lipids. 1993;28:963–967. doi: 10.1007/BF02537115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bryson V, Szybalski W. Microbial selection. Science. 1952;116:45–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeBrabander M, Aerts F, Van Cutsem J, Vanden Bossche H, Borgers M. The activity of ketoconazole in mixed cultures of leukocytes and Candida albicans. Sabouraudia. 1980;18:197–210. doi: 10.1080/00362178085380351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lees N D, Broughton M C, Sanglard D, Bard M. Azole susceptibility and hyphal formation in a cytochrome P-450-deficient mutant of Candida albicans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:831–836. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.5.831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeast. Proposed standard M27-P. Villanova, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nishikawa T, Tokunaga S, Fuse H, Takashima M, Noda T, Ohkawa M, Nakamura S, Namiki M. Experimental study of ascending Candida albicans pyelonephritis focusing on the hyphal form and oxidant injury. Urol Int. 1997;58:131–136. doi: 10.1159/000282969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Odds F C. Antifungal susceptibility testing of Candida spp. by relative growth measurement at single concentrations of antifungal agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:1727–1737. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.8.1727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pierce A M, Pierce H D, Unrau A M, Oehlschlager A C. Lipid composition and polyene antibiotic resistance of Candida albicans mutants. Can J Biochem. 1978;56:135–142. doi: 10.1139/o78-023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shigematsu M L, Uno J, Arai T. Correlative studies on in vivo and in vitro effectiveness of ketoconazole against Candida albicans infection. Jpn J Med Mycol. 1981;22:195–201. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shimokawa O, Kato Y, Nakayama H. Accumulation of 14-methyl sterols and defective hyphal growth in Candida albicans. J Med Vet Mycol. 1986;24:327–336. doi: 10.1080/02681218680000481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shimokawa O, Kato Y, Nakayama H. Increased drug sensitivity in Candida albicans cells accumulating 14-methylated sterols. J Med Vet Mycol. 1986;24:481–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shimokawa O, Kato Y, Kawano K, Nakayama H. Accumulation of 14α-methylergosta-8,24(28)-dien-3β,6α-diol in 14α-demethylation mutant of Candida albicans: genetic evidence for the involvement of 5-desaturase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1989;1003:15–19. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(89)90092-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shimokawa O, Nakayama H. Increased sensitivity of Candida albicans cells accumulating 14α-methylated sterols to active oxygen: possible relevance to in vivo efficacies of azole antifungal agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:1626–1629. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.8.1626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vanden Bossche H, Willemsens G, Cools W, Lauwers W F G, Le Jeune L. Biochemical effects of miconazole on fungi. II. Inhibition of ergosterol biosynthesis in Candida albicans. Chem-Biol Interact. 1978;21:59–78. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(78)90068-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]