Abstract

Background

The evidence on mental health during COVID-19 evolved fast, but still little is known about the long-lasting impact of the sequential lockdowns. We examine changes in young people's mental health from before to during the initial and second more prolonged lockdown, and whether women and those with pre-existing depressive symptoms were disproportionally impacted.

Methods

Participants reported on mental health indicators in an ongoing 18-year data collection in the Danish National Birth Cohort and in a COVID-19 survey, including 8 data points: 7 in the initial lockdown, and 1 year post. Changes in quality of life (QoL), mental well-being, and loneliness were estimated with random effect linear regressions on longitudinal data (N = 32,985), and linear regressions on repeated cross-sections (N = 28,579).

Findings

Interim deterioration in mental well-being and loneliness was observed during the initial lockdown, and only in those without pre-existing depressive symptoms. During the second lockdown, a modest deterioration was again observed for mental well-being and loneliness. QoL likewise only declined among those without pre-existing symptoms, where women showed a greater decline than men. QoL did not normalise during the initial lockdown and remained at lower levels during the second lockdown. These findings were not replicated in the repeated cross-sections.

Interpretation

Except for an interim decrease in mental health, and only in those without pre-existing depressive symptoms, this study's findings do not suggest a substantial detrimental impact of the lockdowns.

Keywords: COVID-19, Lockdown, Mental health, Young people, Depressive symptoms, Longitudinal data

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic became a global reality in early 2020 with enormous impact on society and daily living. Like many other countries worldwide, lockdowns, quarantine requirements and recommendations, social restrictions, and physical distancing were implemented in Denmark in March 2020 to mitigate the spread of the virus. The Danish lockdown demanded all public employees with no critical function to work from home, closing of national borders, schools, day-care centers, sports facilities, and restaurants. Moreover, private companies were strongly recommended to let their employees work from home (Clotworthy et al., 2020). This initial lockdown was eased during late spring, but then gradually reinforced during the autumn 2020 in response to rising numbers of cases and deaths attributed to COVID-19. Mid December, a second national strict lockdown was implemented that lasted to March 2021, from which a gradual reopening began. Several studies have documented acutely deteriorations of mental health during the initial lockdowns compared with pre-pandemic periods (Bueno-Notivol et al., 2021; Lee et al., 2020; Niedzwiedz et al., 2021; Vindegaard and Benros, 2020). Studies have also shown a covariation between pandemic pressure measured as confirmed COVID-19 cases, deaths, and restrictions and the level of psychological well-being in the Danish population (Sønderskov et al., 2020a, Sønderskov et al., 2020b, Sønderskov et al., 2020c; Vistisen et al., 2021, 2022). Especially women and young people have been observed to be disproportionally impacted by the lockdown (Chodkiewicz et al., 2021; Daly et al., 2020; Fancourt et al., 2020; Kwong et al., 2020, 2021; Lee et al., 2020; Niedzwiedz et al., 2021; Pierce et al., 2020; Varga et al., 2021; Vistisen et al., 2021). Further, patient organisations, case stories, and health professionals have raised concerns about marked worsening of pre-existing mental disorders during the lockdowns, which has also been documented by studies (Kwong et al., 2020, 2021). Contrary, other studies, all with before and during lockdown measures, have shown that the changes in mental health were minimal or even slightly improved in people with severe and chronic mental disorders, whereas the deteriorations in mental health were among people without pre-existing mental disorders (Daly et al., 2020; Pan et al., 2020; Pinkham et al., 2020; Thygesen et al., 2021).

Research on the impact of COVID-19 on mental health and related lockdowns evolved fast, but not many studies are based on high-quality data and only a few studies in young people include a before measure and up to several measures during the lockdown. Additionally, we lack knowledge on how the full picture will unfold, and how the sequential and prolonged lockdowns have impacted young people's mental health. Our aim was to investigate mental health in young people following and through the initial lockdown, and during the second and more prolonged lockdown. The objective was to quantify changes in mental health measured as quality of life (QoL), mental well-being, and loneliness from before to during the lockdowns. We further examined whether women and individuals with pre-existing depressive symptoms were disproportionally impacted by the lockdowns. We hypothesised that the lockdowns had a detrimental impact on mental health in young people, and that women and those with pre-existing depressive symptoms were most vulnerable.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

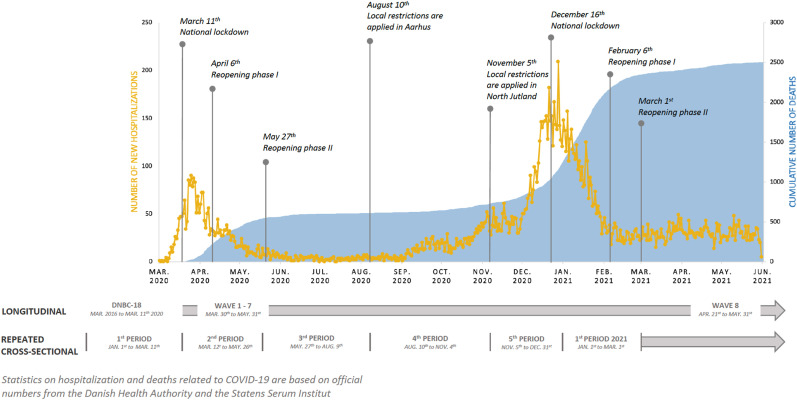

In the mid-nineties, the nationwide national birth cohort, the Danish National Birth Cohort (DNBC) was established, into which 30% of children born in Denmark in 1996–2003 were enrolled (Olsen et al., 2001). Longitudinal data exist from prenatal life unto early adulthood collected in the latest data sweep, the 18-year data collection (DNBC-18). The DNBC-18 was initiated in 2016 and was completed in the beginning of 2022. Further information is available: www.dnbc.dk. To document the public health impact of the national COVID-19 lockdown, we invited participants to complete a COVID-19 survey. Only participants who had earlier provided either their private mail or phone number were invited. Further eligibility criteria were an active social security number and not having withdrawn participation. The initial COVID-19 survey, determined wave 1, was launched in the third week of the initial lockdown, Fig. 1 . The participants born into the DNBC were between 16 and 24 years during the initial lockdown. All participants who responded within a week were re-invited to up to six subsequent consecutive online surveys, i.e. wave 2–7 (Clotworthy et al., 2020). Approximately one year later, i.e. April/May 2021, all participants with identical eligible criteria were re-invited to wave 8 of the COVID-19 survey.

Fig. 1.

The data set up presented according to the development of the COVID-19 pandemic and following lockdowns in Denmark.

The populations, in the present study, were restricted to participants aged 18–24 years with information on household-socio-occupational status, maternal age at childbirth, parity, and maternal smoking collected during pregnancy. In the analyses including the DNBC-18 and the COVID-19 survey, we further restricted our population to those eligible for the DNBC-18 before the initial lockdown, Fig. S1, resulting in a population aged 18–24 years. In total, 32,985 participants had complete data in the DNBC-18. Of these, 7,431 and 8,808, respectively, participated in wave 1 and wave 8 of the COVID-19 survey, Fig. S1. We also estimated changes in mental health by utilising the DNBC-18 collected in 2018 to March 2021 (N = 28,579) as repeated cross-sections divided into five periods for each year, Fig. S2. The periods reflected the initiation, reopening, and reinforcements of the lockdowns in Denmark, Fig. 1.

2.2. Primary mental health outcome measures

Primary mental health measures in this study include two widely used measures of QoL and mental well-being that have shown good reliability and validity (Koushede et al., 2019; Levin and Currie, 2014). The measure of loneliness in this study was only based on a single item.

2.2.1. QoL

We used an adaptation of the Cantril Ladder scale in which respondents rate their life from 0 for the worst life to 10 for the best possible life to measure QoL (Levin and Currie, 2014). This adaption of the Cantril Ladder scale is widely used internationally among adolescents and has shown good reliability and convergent validity with other emotional well-being measures.

2.2.2. Mental well-being

We used the 7-item Short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (SWEMWBS) (Stewart-Brown et al., 2011), which is a validated instrument, also in a Danish age-appropriate sample, to measure mental well-being (Koushede et al., 2019). The response-option for each item is a five-point likert scale. Thus, the total scale ranges from 7 to 35, with higher values indicating better well-being. In the DNBC-18 and wave 8, the items referred to the previous two weeks, whereas in wave 1–7 of the COVID-19 survey, the items were rephrased to the specific week. A 1-point change on the scale is considered to represent a clinically meaningful change.

2.2.3. Loneliness

In the DNBC-18, participants were asked ‘How often do you feel lonely?’ with the response options ‘Never’, ‘Occasionally’, ‘Often’, ‘Very often’, or ‘Do not know’ (excluded). In the COVID-19 survey, the item on loneliness was: ‘In the last week, how often have you felt lonely?’ with response options: ‘Seldom or not at all (less than 1 day)’, ‘Some or a little (1–2 days)’, ‘Occasionally or often (3–4 days)’, or ‘Most of the time (5–7 days)’. The two highest, i.e. at least ‘Often’ and ‘Occasionally or often (3–4 days)’ were categorised as lonely, and otherwise participants were categorised as not lonely.

2.3. Measure of pre-existing depressive symptoms

Measure of pre-existing depressive symptoms was assessed in the DNBC-18 by the Major Depression Inventory (MDI). The MDI is a validated instrument referring to feelings in the past two weeks and ranging from 0 to 50, with higher scores indicating more severe depression (Bech et al., 2015). Pre-existing depressive symptoms was categorised as scoring ≥26, and we further categorised severity of depressive symptoms: severe (31–50), moderate (26–30), mild (21–25), and no depression (0–20) (Bech et al., 2015).

2.4. Covariates

Participants reported their current educational enrolment and housing composition in the DNBC-18. We also included information on gender, age, household-socio-occupational status, maternal age at childbirth, parity, and maternal smoking collected during pregnancy. These covariates were categorised as shown in Table S1.

2.5. Statistical analysis

To account for differential attrition, we estimated inverse probability weights (IPW) by logistic regressions with having data as outcome and the following predictors: gender, household-socio-occupational status, maternal age at childbirth, parity, and maternal smoking collected during pregnancy. Separate analyses were performed for each data point and on the appropriate baseline population, Figs. S1 and S2. Age at time of wave 1 was additionally included in the models for the COVID-19 waves. These IPWs were included in all analyses including the specific data points.

Using the longitudinal data, we estimated the mean changes with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) in QoL, mental well-being, and proportion of change in loneliness by subtracting the pre-lockdown measurement from the lockdown measurement. For the periods in 2018–2021 in the repeated cross-sectional setup, we estimated the mean of QoL and mental well-being and the proportion being lonely with corresponding 95% CI. These calculations were stratified on gender and pre-existing depressive symptoms, respectively. Next, we performed random effects linear regressions on the longitudinal data and linear regressions on the repeated cross-sectional data to estimate the changes in mean QoL and mental well-being, as well as the proportion being lonely, respectively, from before to during lockdown. In the longitudinal setup, we examined the changes from before to during lockdown by including wave 1–8. We contrasted before with during lockdown in a model with a binary variable for lockdown, gender, and pre-existing depressive symptoms. To test for disproportional impact of the lockdown among women vs. men and young people with vs. without pre-existing depressive symptoms, we gradually expanded the models with interactions. First, we included the interaction between lockdown and gender and then the interaction with pre-existing symptoms. Interactions were included if disproportional impacts were observed for at least one of the mental health indicators. Additionally, we investigated whether severity of pre-existing depressive symptoms mattered by including the four categories of severity in the analyses. To examine whether the impact of the lockdown varied across the waves of the COVID-19 survey, we exchanged the binary lockdown variable with a variable indicating wave 1–8. Lastly, we conducted a sensitivity analysis where we restricted the before measure in the longitudinal analyses to participants who completed DNBC-18 in the spring/summer months (periods 2 or 3) in 2019. This was done to address whether our results were biased by seasonal variation or the time gap between the pre- and during lockdown measurement.

In the repeated cross-sectional setup, the during lockdown period was defined as the second period in 2020 and onwards. The pre-defined periods coincide with seasonality as periods 2 and 3 represent spring and summer while periods 1, 4, and 5 represent autumn and winter. We started out testing for interaction between lockdown and period and omitted it if insignificant. We subsequently examined the disproportional impact of lockdown on gender and depressive symptoms by including interaction terms as described above. We performed these analyses unadjusted and adjusted for household-socio-occupational status, maternal age at childbirth, maternal smoking collected during pregnancy, educational enrolment, and household composition.

The analyses were performed with SAS Software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, North Carolina, US) using the commands proc survey means, proc mixed/GLM and applying the weight statement for IPW and random statement for random effect.

Role of the funding source

The funder of this study had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, writing of the article, or in decision to publish.

2.6. Ethical aspects

This study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency via a joint notification to the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences – University of Copenhagen (ref. 514–0497/20-3000, ‘Standing together at a distance: how are Danish National Birth Cohort participants experiencing the corona crisis?’). The cohort is approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency and the Committee on Health Research Ethics under case no. (KF) 01–471/94. Data handling in the DNBC has been approved by Statens Serum Institut (SSI) under ref. no 18/04608 and is covered by the general approval (Fællesanmeldelse) given to SSI. The 18-year follow-up was approved under ref. no 2015-41-3961. The DNBC participants were enrolled by informed consent.

3. Results

Slightly more than half of the participants were 18–20 years of age during the initial lockdown. More women than men participated in the DNBC-18 and the majority of the participants were undertaking education, living with parents, and from educated households. In the COVID-19 survey, seven out of ten participants were women in wave 1 and wave 8, while this proportion slightly increased in wave 2–7, Table S1. Participants in wave 2–7 were more often without pre-existing depressive symptoms, under education, living with parents, from educated households, nulliparous, non-smoking, and older mothers than participants within the DNBC-18 and wave 1 and 8, Table S1.

Before lockdown, women and young people with depressive symptoms reported lower on all mental health indicators than men and those without depressive symptoms, Table S2.

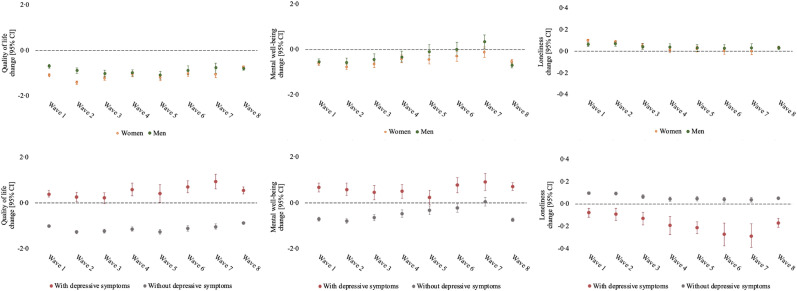

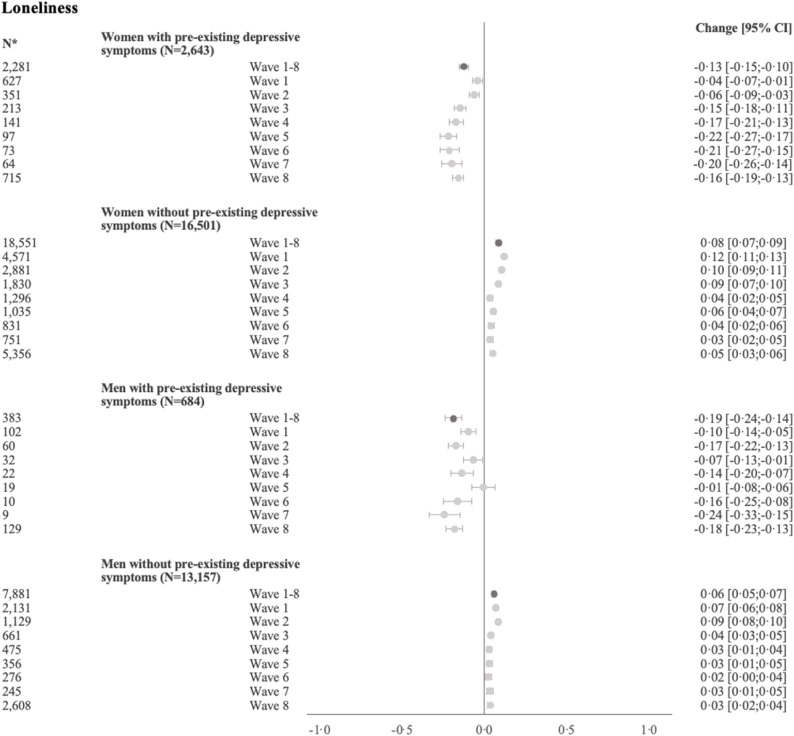

Deteriorations in QoL, mental well-being, and loneliness was observed in the strictest phase of the initial lockdown. Mental well-being and loneliness reached the before levels during the initial lockdown, while the QoL never normalised, Fig. 2 . One year post the initial lockdown (wave 8), reflecting the easing up after the second more prolonged lockdown, the QoL and mental well-being were at same levels as observed early during the initial lockdown. Loneliness was only slightly increased at wave 8 compared to before. Similar patterns were seen for women and men, while it was young people without pre-existing depressive symptoms who experienced the deteriorations.

Fig. 2.

Mean change from pre-to during lockdown [95% CI] in QoL and mental well-being, and proportion of change in loneliness stratified by gender and pre-existing depressive symptoms, respectively (longitudinal setup).

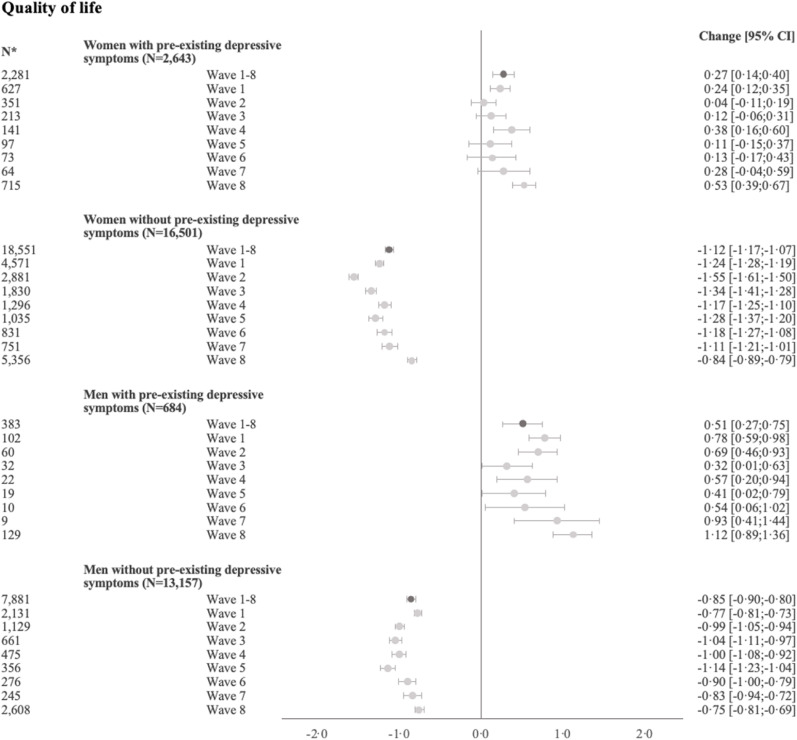

For QoL, the lockdown had a disproportional impact on gender and pre-existing depressive symptoms groups, Fig. 3 . The biggest decline in QoL following lockdown was observed for women without pre-exiting depressive symptoms [−1·12, 95% CI:-1·17;-1·07], while QoL declined −0·85 [95% CI:-0·90;-0·80] among men without pre-existing depressive symptoms. The lowest level of QoL was at wave 2–5 for both groups, and QoL then slightly increased later in the initial lockdown. The level of QoL was still lower compared with before lockdown for both groups in spring 2021. Contrary, the QoL improved in young people with pre-existing depressive symptoms, especially in men. For mental well-being and loneliness, it was likewise people without-pre-existing depressive symptoms who experienced the deteriorations, while those with pre-existing depressive symptoms improved. Women and men without pre-existing depressive symptoms were not disproportionally impacted by the lockdown, as the drop in mental well-being was −0·63 [95% CI:-0·71;-0·55] for women and −0·59 [95% CI:-0·67;-0·50] for men, and the proportion feeling lonely increased by 8·0% [95% CI:7·0; 9·0%] for women and 6·0% [95% CI:5·0; 7·0%] for men. The deteriorations in well-being and loneliness were greatest early in the initial lockdown. In spring 2021, the overall changes in mental well-being and loneliness from before lockdown were approximately the same as the change observed during the initial lockdown. When investigating the degree of pre-existing symptoms, the deteriorations were greatest for the no depressive symptom group and the greatest improvements were seen for the severe group, Fig. S3. Restricting the before measure to data collected in spring and summer 2019 did not change the overall conclusion, Fig. S4.

Fig. 3.

Regression of changes in QoL, mental well-being, and loneliness from pre-to during lockdown (longitudinal setup).

*Repeated measures

Random effect estimates and 95% CI presented (N = 32,985)

(Total number including repeated measures N = 62,081)

All models were weighted by IPW baseline population 1, Fig. S2 (N = 67,346)

p-value for interaction between lockdown, gender, and pre-existing depressive symptoms (wave 1–8):

QoL (p < 0·001), mental well-being (p < 0·001), and loneliness (p < 0·001).

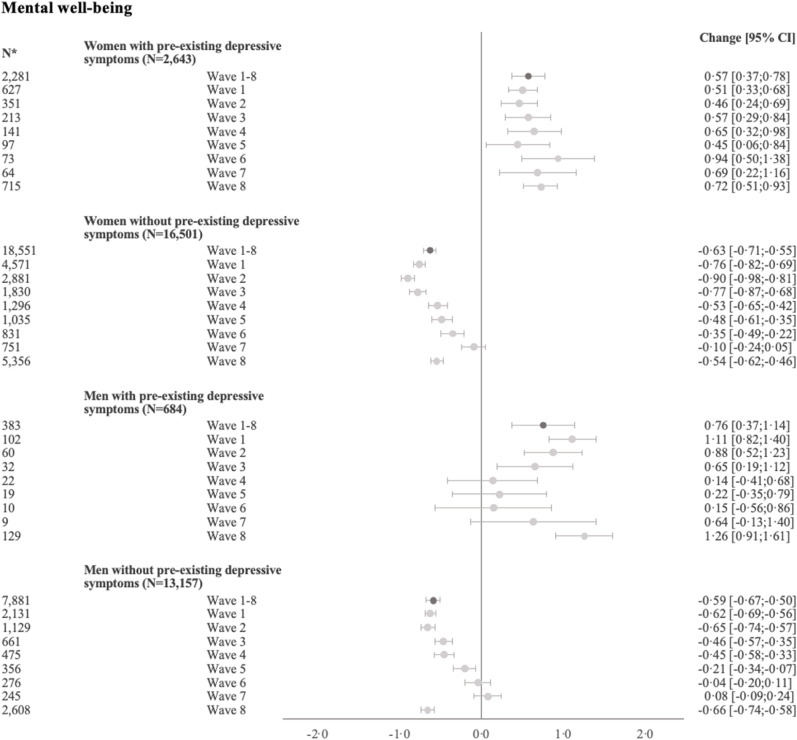

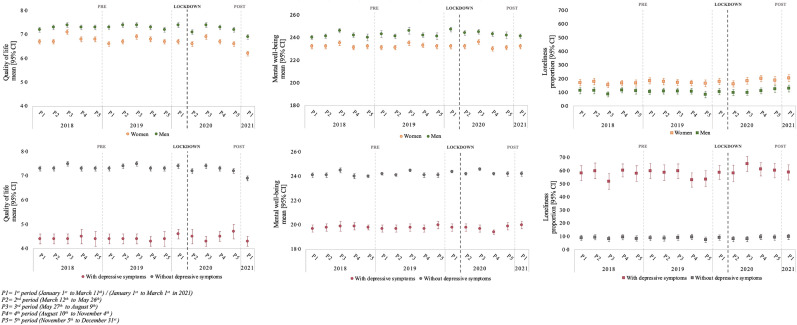

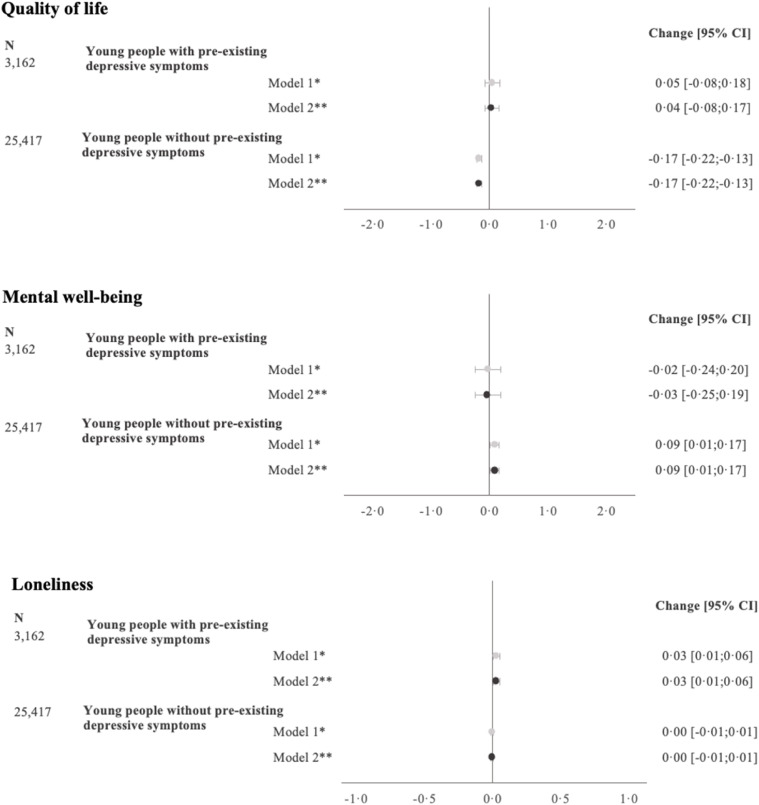

In the repeated cross-sections, there was a slight tendency of improved mental health during summer, i.e. period 3, but no obvious year-to-year variation, Fig. 4 . No clear changes from before to during lockdown were observed for QoL, mental well-being, or loneliness. The regression analyses confirmed almost no impact of the lockdown on any of the mental health indicators, Fig. 5 . The period effect was equal before and during lockdown, indicating no disproportional impact of lockdown on the periods. There was a minor indication of disproportional impact of the lockdown in people without depressive symptoms. QoL only dropped slightly [−0·17, 95% CI:-0·22;-0·13] in people without depressive symptoms, while no change was seen in young people with pre-existing depressive symptoms. A small improvement was observed in mental well-being among people without depressive symptoms [0·09, 95% CI:0·01; 0·17], whereas no improvements were seen in those with depressive symptoms. Loneliness increased 3·0% [95% CI:1·0; 6·0%] in young people with depressive symptoms, while no changes were observed among people without depressive symptoms.

Fig. 4.

Mean/proportion [95% CI] of QoL, mental well-being, and loneliness stratified by gender and depressive symptoms, respectively (repeated cross-sectional setup).

Fig. 5.

Regression of changes in QoL, mental well-being, and loneliness from pre-to during lockdown (repeated cross-sectional setup).

Adjusted estimates and 95% CI are presented (N = 28,579)

*Adjusted for gender and period

**Adjusted for gender, period, household socio-occupational status, maternal age at childbirth, maternal smoking during pregnancy, educational enrolment, and housing composition.

All models were weighted by IPW baseline population 2, Fig. S2 (N = 58,638)

p-value for interaction between lockdown and depressive symptoms:

QoL (p < 0·001), mental well-being (p = 0·3365), and loneliness (p < 0·001).

4. Discussion

Within the longitudinal setup, this study demonstrates an interim deterioration in mental well-being and loneliness during the initial lockdown, and only in young people without pre-existing depressive symptoms. During the gradual reopening of the second lockdown, the mental well-being was equivalent to early in the initial lockdown, while the proportion of loneliness was at levels during the reopening of the initial lockdown, thereby only slightly increased. QoL likewise only declined following lockdown among young people without pre-existing symptoms, but women had a bigger decline in QoL than men. QoL did not normalise among young people without pre-existing symptoms during the initial lockdown and remained at lower levels in spring 2021. These findings from the longitudinal setup also resonate well with findings from other Danish studies showing a covariation between the intensity of the pandemic and the level of psychological well-being in the Danish population (Sønderskov et al., 2020a, Sønderskov et al., 2020b, Sønderskov et al., 2020c; Vistisen et al., 2021, 2022). Further, loneliness and QoL improved in the Danish population during spring 2021 (Pedersen et al., 2022), so we believe that it is likely that the deteriorations observed were only interim. In our study, the observed deteriorations in mental health seemed rather modest and were not replicated in repeated cross-sectional setup. Summarised, our findings do not suggest a substantial lasting impact of the lockdowns on mental health among young individuals.

The longitudinal data allow us to quantify the week-to-week variation in impact across the entire span of the initial lockdown. In contrast, in the repeated cross-sections, the initial lockdown is represented by one longer period. Mental well-being and loneliness seemed to normalise during the gradual reopening of the initial lockdown, and this might explain why we only observe deteriorations in QoL in young people without depressive symptoms in the cross-sectional analyses. Additionally, in the COVID-19 survey it was explicitly stated that the aim was to investigate how the COVID-19 pandemic impacted our living, which was not the case in the ongoing DNBC-18, where COVID-19 was not mentioned, and no adaptions were made. The DNBC participants are regularly invited to complete age specific follow ups. Thus, it is likely, however untestable, that the participants in the DNBC-18 deliberately compensated, so their responses reflected their overall health and not solely their current lockdown situation.

The majority of studies that have suggested a decline in young people's mental health are cross-sectional or do not include a pre-lockdown measurement (Bäuerle et al., 2020; Chodkiewicz et al., 2021; Daly et al., 2021; Fancourt et al., 2020; McGinty et al., 2020; Soest et al., 2020). Most of the earlier findings do also indicate that women were more detrimentally impacted by the lockdown than men (Chodkiewicz et al., 2021; Daly et al., 2020; Fancourt et al., 2020; Kwong et al., 2020, 2021; Lee et al., 2020; Niedzwiedz et al., 2021; Pierce et al., 2020; Varga et al., 2021; Vistisen et al., 2021), but for individuals with a pre-existing mental disorder, the findings are mixed (Bäuerle et al., 2020; Daly et al., 2020; Kwong et al., 2020, 2021; Pan et al., 2020; Pinkham et al., 2020; Thygesen et al., 2021; Varga et al., 2021; Vindegaard and Benros, 2020). One possible explanation for the mixed findings can be the methodological differences. Regression to the mean is of concern, and longitudinal studies in which adjustment for pre-lockdown mental health was performed documented greater deteriorations following the lockdown in individuals with pre-existing mental health disorders (Kwong et al., 2020, 2021). Contrary, studies without adjustment for baseline values, as in our study, document slightly improved or unchanged mental health following lockdown among those with a pre-existing mental disorder (Daly et al., 2020; Pan et al., 2020; Pinkham et al., 2020; Thygesen et al., 2021). Observational studies examining change and adjusting for baseline values can lead to bias in the direction of the cross-sectional association between pre-existing depressive symptoms and the pre-lockdown measure of mental health (Barnett et al., 2005; Glymour et al., 2005; Van Breukelen, 2006). Individuals with pre-existing depressive symptoms scored substantially lower on all mental health indicators, and thus the association between pre-existing depressive symptoms and these mental health indicators reverses after adjustment for the pre-lockdown levels (Tu et al., 2008).

Findings from the longitudinal setup showed that young people with pre-existing depressive symptoms experienced a resilience or an improvement during lockdown, for which there could be multiple possible explanations. The lockdown and the social isolation might have given individuals with depressive symptoms more calmness, as the new circumstances were in line with their normal daily life. This is also supported in a qualitative study where a small group of young people described how their mental health had improved during the initial lockdown (McKinlay et al., 2022). Young people without pre-existing depressive symptoms however showed a deterioration in mental health which might represent a normal fear in response to an unpredicted crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Although our study did not show any deteriorations among young people with pre-existing depressive symptoms, it is important to emphasise that we demonstrate that the mental health of these individuals was and remained systematically worse compared to those without pre-existing depressive symptoms.

4.1. Strengths and limitations

Strengths worth highlighting are the tandem use of longitudinal data on individuals aged 18–24 and repeated samples of individuals aged 18 years originating from the same baseline population. Moreover, our data collection during the initial lockdown included up to seven measurements spanning the reopening phases, as well as one measurement after a second and more prolonged lockdown. The repeated cross-sections allowed us to indirectly quantify seasonal variations, as the pre-specified periods reflect different seasons. In these analyses, there was no indications of a disproportional impact of lockdown on the periods. This setup is only vulnerable to attrition if the participation in DNBC-18 systematically changed over year of birth or season, as opposed to the longitudinal setup which is more vulnerable to attrition due to loss to follow-up. We attempted to reduce bias from differential attrition by inverse probability weighting. The validity of this method relies on a correctly specified model including all relevant predictors for loss to follow-up, which cannot be assumed as we only had access to the maternal self-reported characteristics.

Interpretation of our findings deserve consideration of some limitations. In the longitudinal setup, the baseline data was collected at age 18 years and three months for all participants, whereas the participants’ ages during lockdown was 18–24 years. Thus, the timespan between the before and during lockdown measurement was greater for the older participants. For older participants, changes in mental health may be underestimated since the pre-lockdown measurement represent a younger age than the follow-up measures, and on average reporting on mental health instruments improves with age (Pierce et al., 2020). Another limitation in the longitudinal setup is that the changes in mental health may be explained by the seasonal variation. As an attempt to preclude this, we restricted the before measure to data collected in spring/summer 2019 to account for both the varying timespan and potential seasonal variation. The results from these analyses did not change the overall conclusion, and therefore these limitations should not raise any major concerns. However, we cannot preclude that other life events such as moving from parental home, leaving or starting school, occupation, or university study have influenced the mental health and thereby our estimates of change. This shortcoming is circumvented in the repeated cross-sectional analyses, where we compare different samples of 18-year-olds.

Mental well-being was measured by SWEMWBS, which has been validated in a Danish setting and is psychometrically sound (Koushede et al., 2019), whereas QoL and loneliness were measured by one item only. However, by including all three mental health indicators based on before measure and several during lockdown measures, we believe that our results contribute substantially to our knowledge on the mental health impact of the lockdown. Finally, the DNBC has previously been shown to be healthier and more often from households with higher occupational levels than the background population (Jacobsen et al., 2010), and our population was mainly living with their parents and studying. Thus, the findings from this study cannot necessarily be generalised to all 18–24-year-olds. Moreover, all countries have experienced different COVID-19 related governmental restrictions as well as incidence and death rates (Varga et al., 2021). The impact of the lockdown in mental health is likely to be more pronounced in countries with more severe restrictions compared to a country where national lockdowns were accompanied with economic relief packages. Thus, the findings from this study should be generalised to other countries with caution.

In summary, the findings from the longitudinal setup did reveal a modest intermittent deterioration in mental health during the initial lockdown in young individuals without depressive symptoms prior to lockdown, as well as lower QoL and well-being during the second lockdown. The mental health of young individuals with depressive symptoms prior to lockdown did not show similar deteriorations but remained unchanged or even slightly improved. Only for QoL, women without pre-existing depressive symptoms experienced a greater decline than men. These findings interpreted simultaneously with the findings from the repeated cross-sections do not support a substantial lasting impact of the lockdowns on the mental health in young individuals.

Author contributions

AJ, PKA, and KSL conceived and designed the study. AJ, KSL, and SD were involved in the data collection and data management of the COVID-19 survey. AJ conducted the analyses and together with KSL drafted the first draft of the manuscript. JG was involved in data visualisation. KSL was responsible for funding acquisition and supervision. All authors contributed to the analytical approach, interpretation of the data, revisions of the manuscript, and submission of the final manuscript. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted. AJ is the guarantor of the manuscript and was primarily responsible for the formal analyses, data curation, methodology, drafting of the original manuscript, writing/editing the manuscript, and data visualisation. KSL has additionally verified the underlying dataset.

Data sharing

According to European law (General Data Protection Regulation), data containing potentially identifying or sensitive personal information are restricted. However, for academic researcher, data could be available on request via DNBC dnbc-research@ssi.dk.

Funding

This study was made possible by a grant from the Velux Foundation (grant number 36336, ‘Standing together at a distance – how Danes are handling the corona crisis’). The funders of the study had no part in the conception or design of the study, or in the decision to publish.

Ethics

This study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency via a joint notification to the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences – University of Copenhagen (ref. 514–0497/20-3000, ‘Standing together at a distance: how are Danish National Birth Cohort participants experiencing the corona crisis?’). The cohort is approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency and the Committee on Health Research Ethics under case no. (KF) 01–471/94. Data handling in the DNBC has been approved by Statens Serum Institut (SSI) under ref. no 18/04608 and is covered by the general approval (Fællesanmeldelse) given to SSI. The 18-year follow-up was approved under ref. no 2015-41-3961. The DNBC participants were enrolled by informed consent.

Declaration of competing interest

All authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgment

The Danish National Birth Cohort (DNBC) was established with a significant grant from the Danish National Research Foundation. Additional support was obtained from the Danish Regional Committees, the Pharmacy Foundation, the Egmont Foundation, the March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation, the Health Foundation, and other minor grants. The DNBC Biobank has been supported by the Novo Nordisk Foundation and the Lundbeck Foundation. Follow-up of mothers and children has been supported by the Danish Medical Research Council (SSVF 0646, 271-08-0839/06-066023, O602-01042B, 0602-02738B), the Lundbeck Foundation (195/04, R100-A9193), The Innovation Fund Denmark 0603-00294B (09-067124), the Nordea Foundation (02-2013-2014), Aarhus Ideas (AU R9-A959-13-S804), a University of Copenhagen Strategic Grant (IFSV 2012) and the Danish Council for Independent Research (DFF – 4183-00594 and DFF – 4183-00152). We thank Professor Lau Caspar Thygesen for a valuable discussion of the analytical model and interpretation of results.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2022.03.001.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Barnett A.G., van der Pols J.C., Dobson A.J. Regression to the mean: what it is and how to deal with it. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2005;34:215–220. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bäuerle A., Steinbach J., Schweda A., Beckord J., Hetkamp M., Weismüller B., Kohler H., Musche V., Dörrie N., Teufel M., Skoda E.M. Mental health burden of the COVID-19 outbreak in Germany: predictors of mental health impairment. J. Prim. Care Community Heal. 2020;11:1–8. doi: 10.1177/2150132720953682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bech P., Timmerby N., Martiny K., Lunde M., Soendergaard S. Psychometric evaluation of the major depression inventory (MDI) as depression severity scale using the LEAD (longitudinal expert Assessment of all data) as index of validity. BMC Psychiatr. 2015;15:190. doi: 10.1186/s12888-015-0529-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bueno-Notivol J., Gracia-García P., Olaya B., Lasheras I., López-Antón R., Santabárbara J. Prevalence of depression during the COVID-19 outbreak: a meta-analysis of community-based studies. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2021;21:100196. doi: 10.1016/j.ijchp.2020.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chodkiewicz J., Miniszewska J., Krajewska E., Biliński P. Mental health during the second wave of the covid-19 pandemic—polish studies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2021;18:3423. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18073423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clotworthy A., Dissing N., Nguyen L., Jensen A.K., Andersen T.O., Bilsteen J.F., Elsenburg L.K., Keller A.C., Kusumastuti S., Mathisen J., Mehta A.J., Pinot de Moira A., Skovdal M., Strandberg-Larsen K., V Varga T., Vinter J.L., Xu T., Hoyer K., Rod N.H. Standing together - at a distance”: Documenting changes in mental-health indicators in Denmark during the COVID-19 pandemic. Scand. J. Publ. Health. 2020;49:79–87. doi: 10.1177/1403494820956445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly M., Sutin A., Robinson E. Longitudinal changes in mental health and the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence from the UK household longitudinal study. Psychol. Med. 2020;13:1–10. doi: 10.1017/S0033291720004432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly M., Sutin A.R., Robinson E. Depression reported by US adults in 2017–2018 and March and April 2020. J. Affect. Disord. 2021;278:131–135. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.09.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fancourt D., Steptoe A., Bu F. Trajectories of anxiety and depressive symptoms during enforced isolation due to COVID-19 in England: a longitudinal observational study. Lancet Psychiatr. 2020;8:141–149. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30482-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glymour M.M., Weuve J., Berkman L.F., Kawachi I., Robins J.M. When is baseline adjustment useful in analyses of change? An example with education and cognitive change. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2005;162:267–278. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen T.N., Nohr E.A., Frydenberg M. Selection by socioeconomic factors into the Danish national birth cohort. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2010;25:349–355. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9448-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koushede V., Lasgaard M., Hinrichsen C., Meilstrup C., Nielsen L., Rayce S.B., Torres-Sahli M., Gudmundsdottir D.G., Stewart-Brown S., Santini Z.I. Measuring mental well-being in Denmark: validation of the original and short version of the Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS and SWEMWBS) and cross-cultural comparison across four European settings. Psychiatr. Res. 2019;271:502–509. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwong A.S.F., Pearson R.M., Adams M.J., Northstone K., Tilling K., Smith D., Fawns-Ritchie C., Bould H., Warne N., Zammit S., Gunnell D.J., Moran P.A., Micali N., Reichenberg A., Hickman M., Rai D., Haworth S., Campbell A., Altschul D., Flaig R., McIntosh A.M., Lawlor D.A., Porteous D., Timpson N.J. Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in two longitudinal UK population cohorts. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2021;24:1–10. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2020.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwong A.S.F., Pearson R.M., Smith D., Northstone K., Lawlor D.A., Timpson N.J. Longitudinal evidence for persistent anxiety in young adults through COVID-19 restrictions. Wellcome Open Res. 2020;5:195. doi: 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.16206.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C.M., Cadigan J.M., Rhew I.C. Increases in loneliness among young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic and association with increases in mental health problems. J. Adolesc. Health. 2020;67:714–717. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin K.A., Currie C. Reliability and validity of an adapted version of the Cantril ladder for use with adolescent samples. Soc. Indicat. Res. 2014;119:1047–1063. doi: 10.1007/s11205-013-0507-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McGinty E.E., Presskreischer R., Han H., Barry C.L. Psychological Distress and loneliness reported by US adults in 2018 and April 2020. JAMA, J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2020;324:93–94. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.9740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinlay A.R., May T., Dawes J., Fancourt D., Burton A. ‘You’re just there, alone in your room with your thoughts': a qualitative study about the psychosocial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic among young people living in the UK. BMJ Open. 2022;12 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-053676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niedzwiedz C.L., Green M.J., Benzeval M., Campbell D., Craig P., Demou E., Leyland A., Pearce A., Thomson R., Whitley E., Katikireddi S.V. Mental health and health behaviours before and during the initial phase of the COVID-19 lockdown: longitudinal analyses of the UK Household Longitudinal Study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2021;75:224–231. doi: 10.1136/jech-2020-215060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen J., Melbye M., Olsen S.F., Sørensen T.I.A., Aaby P., Andersen A.-M.N., Taxbøl D., Hansen K.D., Juhl M., Schow T.B., Sørensen H.T., Andresen J., Mortensen E.L., Olesen A.W., Søndergaard C. The Danish National Birth Cohort - its background, structure and aim. Scand. J. Publ. Health. 2001;29:300–307. doi: 10.1177/14034948010290040201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan K.Y., Kok A.A.L., Eikelenboom M., Horsfall M., Jörg F., Luteijn R.A., Rhebergen D., Oppen P. van, Giltay E.J., Penninx B.W.J.H. The mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on people with and without depressive, anxiety, or obsessive-compulsive disorders: a longitudinal study of three Dutch case-control cohorts. Lancet Psychiatr. 2020;8:121–129. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30491-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen M.T., Andersen T.O., Clotworthy A., Jensen A.K., Strandberg-Larsen K., Rod N.H., Varga T.V. Time trends in mental health indicators during the initial 16 months of the COVID-19 pandemic in Denmark. BMC Psychiatr. 2022;22:25. doi: 10.1186/s12888-021-03655-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce M., Hope H., Ford T., Hatch S., Hotopf M., John A., Kontopantelis E., Webb R., Wessely S., McManus S., Abel K.M. Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. Lancet Psychiatr. 2020;7:883–892. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30308-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinkham A.E., Ackerman R.A., Depp C.A., Harvey P.D., Moore R.C. A longitudinal investigation of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of individuals with pre-existing severe mental illnesses. Psychiatr. Res. 2020;294:113493. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soest T.V., Bakken A., Pedersen W., Sletten M.A. Life satisfaction among adolescents before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Tidsskr. Den Nor. Laegeforening. 2020;140 doi: 10.4045/tidsskr.20.0437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sønderskov K.M., Dinesen P.T., Santini Z.I., Ostergaard S.D. Increased psychological well-being after the apex of the COVID-19 pandemic. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2020;32:277–279. doi: 10.1017/neu.2020.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sønderskov K.M., Dinesen P.T., Santini Z.I., Østergaard S.D. The depressive state of Denmark during the COVID-19 pandemic. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2020:1–3. doi: 10.1017/neu.2020.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sønderskov K.M., Dinesen P.T., Vistisen H.T., Østergaard S.D. Variation in psychological well-being and symptoms of anxiety and depression during the COVID-19 Pandemic: results from a 3-wave panel survey. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2020;33:156–159. doi: 10.1017/neu.2020.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart-Brown S., Platt S., Tennant A., Maheswaran H., Parkinson J., Weich S., Tennant R., Taggart F., Clarke A. The Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS): a valid and reliable tool for measuring mental well-being in diverse populations and projects. J. Epidemiol. Community Heal. 2011;65:A38–A39. doi: 10.1136/jech.2011.143586.86. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thygesen L.C., Møller S.P., Ersbøll A.K., Santini Z.I., Nielsen M.B.D., Grønbæk M.K., Ekholm O. Decreasing mental well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal study among Danes before and during the pandemic. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021;144:151–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.09.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu Y.K., Gunnell D., Gilthorpe M.S. Simpson's Paradox, Lord's Paradox, and Suppression Effects are the same phenomenon - the reversal paradox. Emerg. Themes Epidemiol. 2008;5:1. doi: 10.1186/1742-7622-5-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Breukelen G.J.P. ANCOVA versus change from baseline had more power in randomized studies and more bias in nonrandomized studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2006;59:920–925. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varga T.V., Bu F., Dissing A.S., Elsenburg L.K., Bustamante J.J.H., Matta J., van Zon S.K.R., Brouwer S., Bültmann U., Fancourt D., Hoeyer K., Goldberg M., Melchior M., Strandberg-Larsen K., Zins M., Clotworthy A., Rod N.H. Loneliness, worries, anxiety, and precautionary behaviours in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal analysis of 200,000 Western and Northern Europeans. Lancet Reg. Heal. - Eur. 2021;2:100020. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2020.100020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vindegaard N., Benros M.E. COVID-19 pandemic and mental health consequences: systematic review of the current evidence. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020;89:531–542. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vistisen H.T., Santini Z.I., Sønderskov K.M., Østergaard S.D. The less depressive state of Denmark following the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2022:1–4. doi: 10.1017/neu.2022.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vistisen H.T., Sønderskov K.M., Dinesen P.T., Østergaard S.D. Psychological well-being and symptoms of depression and anxiety across age groups during the second wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Denmark. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2021;33:331–334. doi: 10.1017/neu.2021.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.