Abstract

Objectives:

Although many Iraq/Afghanistan warzone veterans report few problems with adjustment, a substantial proportion report debilitating mental health symptoms and functional impairment, suggesting the influence of personal factors that may promote adjustment. A significant minority also incur warzone-related traumatic brain injury (TBI), the majority of which are of mild severity (mTBI). We tested direct and indirect pathways through which a resilient personality prototype predicts adjustment of warzone veterans with and without mTBI over time.

Method:

A sample of 264 war veterans (181 men) completed measures of lifetime and warzone-related TBIs, personality traits, psychological adjustment, quality of life, and functional impairment. Social support, coping and psychological flexibility were examined as mediators of the resilience-adjustment relationship. Instruments were administered at baseline, 4-, 8-, and 12-month assessments. Structural equation models accounted for combat exposure and response style.

Results:

Compared with a non-resilient personality prototype, a resilient prototype was directly associated with lower PTSD, depression, and functional disability, and higher quality of life at all time-points. Warzone mTBIs frequency was associated with higher scores on a measure of functional disability. Indirect effects via psychological flexibility were observed from personality to all outcomes, and from warzone-related mTBIs to PTSD, depression, and functional disability, at each time-point.

Conclusions:

Several characteristics differentiate veterans who are resilient from those who are less so. These findings reveal several factors through which a resilient personality prototype and the number of mTBIs may be associated with veteran adjustment. Psychological flexibility appears to be a critical modifiable factor in veteran adjustment.

Keywords: Resilience, PTSD, depression, mild traumatic brain injury, psychological flexibility, personality

Many veterans returning from deployment to the post-9/11 wars in Iraq and Afghanistan are resilient, reporting few problems with adjustment or distress (Bonanno et al., 2012; Isaacs et al., 2017). A substantial proportion report debilitating symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD; 12% to 23%) and depression (15%; Fulton et al., 2015; Seal, Bertenthal, Miner, Sen, & Marmar, 2007). A significant minority also sustain a traumatic brain injury (TBI) during deployment. An estimated 10% of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans using Veterans Health Administration services between 2009 and 2011 were classified as having incurred a TBI (Cifu et al., 2014). The majority of TBIs occurring among military personnel are mild (mTBI; 82.3% out of 383,947 cases; Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center, 2019).

Certain symptoms of PTSD and depression are similar to those associated with post-concussive syndromes including fatigue, social withdrawal, sleep disturbance, somatic complaints, sadness, irritability, interpersonal sensitivity and difficulties concentrating (Bailie et al., 2016; Lange et al., 2014). Some studies find associations with distress and decreased quality of life among veterans with deployment-related mTBI (Brickell, Lange, & French, 2014; Dretsch, Silverberg, & Iverson, 2015). Critical and meta-analytic literature reviews argue that limited evidence substantiates mTBI as a risk factor for emotional problems (Carroll et al., 2014) suggesting that various psychological (e.g., preinjury mental health issues) and situational factors (e.g., litigation) account for much of the variance in adjustment problems post-mTBI (Broshek, De Marco, & Freeman, 2015; Panayioutou, Jackson, & Crowe, 2010; Rohling, Langhinrichsen-Rohling, & Axelrod, 2017). Studies utilizing omnibus measures of personality to monitor symptom exaggeration and distress among individuals with and without mTBI support these observations (Jones, Ingram, & Ben-Porath, 2012; Kennedy, Cooper, Reid, Tate, & Lange, 2015).

Despite the documented influence of individual and situational differences in adjustment of veterans with mTBI, the contribution of personality characteristics is understudied. Personality variables are often examined in this literature in relation to symptom exaggeration (e.g., Jurik et al., in press) or as indicators of distress that vary as a function of TBI severity (e.g., Kennedy et al., 2015). These approaches do little to inform our theoretical appreciation of personality factors that characterize veterans who may be more likely to exhibit optimal adjustment following deployment, regardless of their mTBI status.

To some extent, this gap has been addressed by recent cross-sectional studies that document inverse relationships between self-reported resilience and distress in mTBI samples (Losoi et al., 2015; Sullivan, Edmed, Allan, Smith, & Karlsson, 2015). However, these studies relied on face-valid measures derived from atheoretical conceptualizations of resilience that did not specify testable mechanisms through which resilience facilitated adjustment, a feature critical to developing clinical interventions. The lack of a comprehensive and testable theoretical model of resilience in this research undermines our ability to develop and provide psychological interventions that could promote resilience (Davydov, Stewart, Ritchie, & Chandieu, 2010).

In the present study, we rely on a theoretical model of resilience to test hypothesized relationships among psychological factors that differentially predict subsequent adjustment among warzone veterans with and without deployment-related mTBI. According to Block’s theory of personality development, ego control and ego resiliency develop from healthy attachments formed during infancy and maintained through childhood, and these factors provide an individual with capacities essential to effectively adapt to change, stress, and conflict (Block, 1993; Block & Block, 1980). Resilient individuals exhibit proactive behavior, pursue personally meaningful goals, and report greater flexibility, self-regulation, resourcefulness and active engagement with the environment under routine and stressful circumstances (Gramzow et al., 2004; Ong, Bergeman, & Boker, 2009). These capacities cultivate a positive cascade of rewarding emotional and behavioral experiences that, in turn, motivate further engagement with the environment and others, enhancing personal control, self-esteem, and confidence (Elliott, Barron, Stein, Wright, & Lowery, in press). Longitudinal research indicates resilient individuals are more socially competent as children and adults, have more rewarding interpersonal relationships, and are more likely to exhibit optimal physical and emotional health (Caspi, 2000; Dennissen, Asendorpf, & van Aken, 2008).

Applications of this model in studies of persons with debilitating, chronic health problems have found that resilient individuals have a proclivity for positive emotions (among persons with chronic pain; Ong, Zautra, & Reid, 2010), participate in desired activities (following upper limb loss; Walsh et al., 2016), and use more effective coping strategies (following spinal cord injury; Berry, Elliott, & Rivera, 2007). In previous work, we found a resilient personality prototype among war veterans predicted adjustment over time through associations with social support and psychological flexibility, and through an inverse relationship with avoidant coping (Elliott et al., 2015). These relationships were independent of a positive TBI screen and degree of combat exposure. Study limitations included a relatively low sample size (N = 127), inattention to quality of life, and no assessment of the number and severity of TBIs.

The current study extends our investigation of the ways in which a resilient personality prototype facilitates adjustment among war veterans with and without mTBI. We rectify the limitations of the previous work (Elliott et al., 2015) by including various indicators of TBI including lifetime number of TBIs, number of mTBIs incurred during post-9/11 warzone deployment, and length of loss of consciousness and post-traumatic amnesia as indicators of mTBI severity. We used a contextual model to test the positive effects of resilience on veteran adjustment, relying on an established measure of “Big Five” personality traits to identify a resilient personality prototype (Alessandri et al., 2014). We then examined the presumed beneficial associations of resilience with characteristics critical to veteran adjustment: social support, effective coping strategies, and psychological flexibility. We expected that resilience would predict important elements of veteran emotional adjustment (PTSD, depression) and functioning (quality of life, functional disability) over a 12-month period through its predicted effects on these mediators. In addition, we included a self-report measure of resilience as a potential mediator, to further elucidate the predictive properties of these popular measures when other psychological variables (e.g., personality traits, social support, coping) are taken into account. Combat exposure and socially desirable response tendencies served as covariates.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Procedures were approved by the local Institutional Review Board. Post-9/11 veterans enrolled in the Central Texas Veterans Health Care System (CTVHCS) were recruited to participate in a longitudinal study of predictors of post-deployment adjustment. Participants were recruited through advertisements and direct mailings to veterans enrolled at the healthcare system.

Telephone screenings were conducted to determine eligibility criteria: service in support of the Iraq or Afghanistan campaigns after September 11, 2001; stable on psychotropic medications or in psychotherapy if receiving such interventions; and not relocating out of the area within four months of consent. Initially eligible participants were scheduled for an in-person assessment. Informed written consent was obtained prior to the baseline interview during which participants completed a diagnostic interview and self-report measures. Participants were ineligible if they had suicidal or homicidal ideation warranting crisis intervention, or if they had an existing bipolar or psychotic disorder. Two follow-up assessments were mailed four and eight months later. At a 12-month follow-up, participants completed self-report measures and an in-person diagnostic interview conducted by master’s and doctoral level assessors. Diagnostic consensus was reached on all interviews under the supervision of a clinical psychologist.

A total of 345 veterans consented to participate. Thirty-six were excluded because of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Forty-three with moderate or severe TBI were also excluded. Two others were excluded due to missing personality data. The final sample for this study was 264 (average age = 38.94 years, SD = 9.94; average years of education = 14.09, SD = 2.09). The majority were male (n = 181; 68.6%) and identified as White/Caucasian (n = 147; African American, n = 90; other, n = 27). Fifty-two (19.7%) identified as Hispanic. Approximately 72% had a VA service-connected disability.

Independent Variables

Personality Prototypes.

The 60-item NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO–FFI; Costa & McCrae, 1992) was administered at baseline. The NEO-FFI is a shortened version of the Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO–PI–R; Costa & McCrae, 1992) for assessing five domains of adult personality: Neuroticism, Extraversion, Openness to Experience, Agreeableness, and Conscientiousness. The NEO–FFI factors show high correlations (.75 to .89) with the full-scale NEO–PI factors. Internal consistency reliabilities range from .68 (Agreeableness) to .86 (Neuroticism), and test–retest reliabilities from .79 (Extraversion, Openness) to .89 (Neuroticsm; Costa & McCrae, 1992). Raw scores were converted to gender-specific T scores based on adult norms (Costa & McCrae, 1992).

Studies of resilient personality prototypes usually apply clustering techniques to personality data collected from a variety of measurement methods including proxy reports, behavioral ratings, Q-sorts, and self-report measures of personality traits. Instruments that assess the “Big Five” traits are often used, as the resilient prototype is consistently represented by elevations on Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Openness to Experience and Extraversion, and lower scores on Neuroticism (Alessandri et al., 2014; Farkas & Orosz, 2015). This pattern captures the ego resiliency and ego control dimensions described in the Block model (Block & Block, 1980). Two other replicable prototypes – Overcontrolled and Undercontrolled – appear in most studies of the prototypes (Asendorpf, Borkenau, Ostendorf, & Van Aken, 2001). Individuals with these characteristics are more likely than resilient individuals to experience problems with emotional adjustment and in interpersonal and social relationships, and social adjustment. For purposes of the present study we focus on the characteristics of the resilient prototype hypothesized to facilitate adjustment compared to those who are not resilient, and to isolate potentially malleable mechanisms that distinguish between resilient and non-resilient veterans (e.g., coping, psychological flexibility, social support).

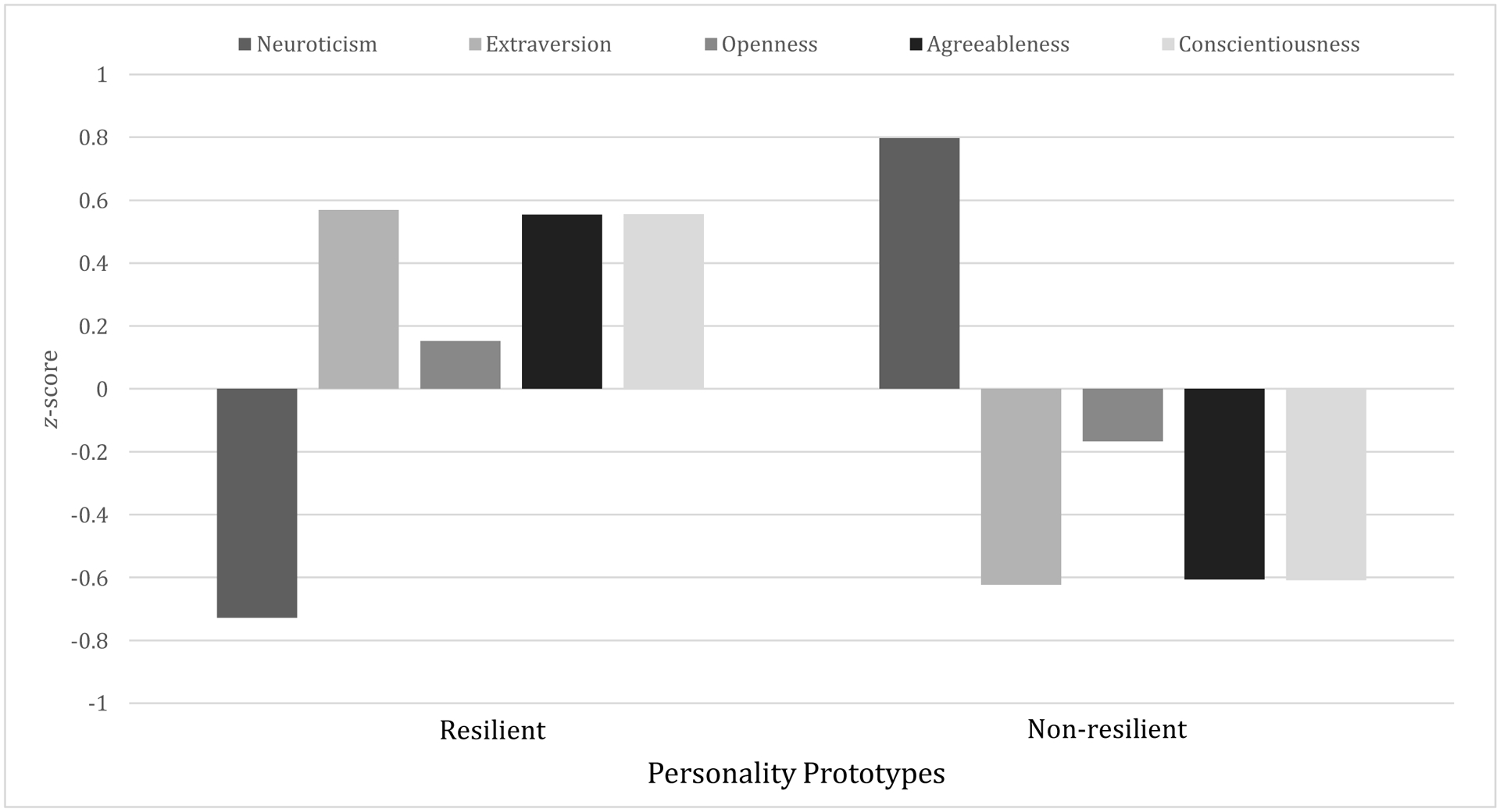

A two-step cluster analysis was conducted to decide the number of personality types (clusters). The clusters were created from the Neuroticism, Extraversion, Openness to Experience, Agreeableness, and Conscientiousness subscale scores. Given 264 participants, the candidate number of clusters ranged from 1 (totally homogenous) to 264 (totally heterogeneous). The Ward’s method along with squared Euclidean distance measures were used to calculate the total within-cluster sums of squares for each cluster solution. The largest change in total within-cluster sums of squares happened when the number of clusters increased from 1 to 2. After the 2-cluster solution, the total within-cluster sums of squares decreased mildly. Hence, we decided on a 2-cluster result in step 1. The K-means analysis was employed to optimize the cluster classification by utilizing the initial cluster centers from step 1. The level of agreement was substantial: Cohen’s Kappa coefficient was .77 (Landis & Koch, 1977). The personality prototype served as an independent variable. Consistent with past research, the resilient prototype (n = 138) was characterized by the lower Neuroticism value, and higher values on the other four scales (see Figure 1). The non-resilient prototype (n = 126) had an elevated Neuroticism value and lower values on the other scales.

Figure 1.

Resilient (n=138) and non-resilient (n=126) personality prototypes among veterans based on NEO-FFI z scores.

Traumatic Brain Injury.

The structured interview developed by Vasterling and colleagues (Alosco et al., 2016) was used to assess the number, recency, type, and clinical sequelae associated with TBI experienced at any time. A positive screen was determined by a head injury that resulted in a loss of consciousness (LOC), an alteration of consciousness (e.g., dazed, confused, “seeing stars”), or posttraumatic amnesia (PTA). From this information we determined (a) the number of lifetime TBIs reported by the veteran, the number of TBIs incurred during post-9/11 warzone deployment, and the longest periods of LOC and PTA. The number of TBIs assessed in detail was limited to five. Length of LOC and PTA were rated for each TBI. Mild TBIs were determined by a LOC lasting less than 30 minutes and/or PTA lasting less than 24 hours (American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine, 1993).

We coded the longest experience of LOC and PTA reported by each participant for our analyses. LOC was coded as either 0 (no LOC), 1 (less than 1 minute), 2 (1 to 15 minutes), or 3 (16 to 30 minutes). PTA was coded as 0 (no PTA occurred), 1 (less than 1 hour of PTA), or 2 (1 to 24 hours of PTA). A total of 164 (62%) veterans screened positive for at least one lifetime mTBI, and 118 (45%) screened positive for at least one mTBI during deployment (e.g., from a blast, vehicular accident, fall, bullet, fragment).

Covariates

Combat Exposure.

The 18-item Full Combat Experiences Scale (FCES; Hoge et al., 2004) was administered at baseline to assess level of combat exposure. The items describe combat events relevant to the Iraq and Afghanistan campaigns (e.g., being attacked or ambushed, handling human remains, incoming mortars). Items are rated on a 5-point scale, ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (10 or more times). The total score was used. Internal consistency was α = .93.

Social Desirability.

We included a ten-item version of the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale (MC; Strahan & Gerbasi, 1972) at baseline to assess social desirability response tendencies. Each item was rated as 1 (true) or 0 (false). Higher scores indicate a greater tendency to respond in a socially desirable fashion. Recent evidence indicates the Marlowe-Crowne scale performs well compared to contemporary methods in detecting “faking bad” and “faking good” (Lambert, Arbuckle, & Holden, 2016). Internal consistency was α = .61.

Mediating Variables

Psychological flexibility.

The 7-item Acceptance and Action Questionnaire - II (AAQ–II; Bond et al., 2011) assessed psychological flexibility at baseline. Psychological flexibility reflects the ability to which a person may experience unwanted internal experiences without trying to change them, and commit to context-appropriate behaviors consistent with personal values (Hayes, Luoma, Bond, Masuda, & Lillis, 2006). Items are rated on a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (never true) to 7 (always true). The AAQ–II has a single-factor structure and demonstrates acceptable internal consistency, test–retest reliability, and convergent associations with the original AAQ (Bond et al., 2011). Lower total scores indicate greater psychological flexibility, and predict greater PTSD symptom severity after accounting for established pre-, peri-, and post-trauma risk factors (Meyer et al., in press). Internal consistency was .93.

Coping.

The 28-item Brief COPE (B-COPE, Carver, 1997) assessed coping styles at baseline. Respondents are instructed to rate each item to indicate what they generally do and feel in stressful situations on a 4-point Likert-type scale that ranges from 0 (I usually don’t do this) to 3 (I usually do this a lot). A factor analysis of the B-COPE (Grosso et al., 2014) revealed two factor scores that we used for analysis: action-oriented and avoidant coping. Higher scores reflect a greater proclivity for that coping style. Internal coefficients were acceptable (.81, action-oriented coping; .70, avoidant coping).

Social support.

The 15-item Deployment Risk and Resilience Inventory Postdeployment Social Support scale (PDSS; King, King, Vogt, Knight, & Samper, 2006) assessed perceived availability of social support at baseline. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Validated for use with Iraq/Afghanistan veterans (Vogt, Proctor, King, King, & Vasterling, 2008), the PDSS measures the extent to which the respondent believes their friends and family provide emotional sustenance and instrumental assistance, and the extent to which they feel respected for their military service. Higher total scores indicate greater social support. Internal consistency was .87.

Self-reported resilience.

The Brief Resilience Scale (BRS; Smith et al., 2008) was administered at baseline. This six-item instrument assesses a unitary construct that signifies the ability to “…bounce back or recover from stress” (Smith et al., 2008; p. 199). Respondents are instructed to select how much they agree with each item on a Likert-type scale that ranges from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Higher total scores reflect greater resilience. The BRS is significantly associated with other self-report measures of resilience (Windle, Bennett, & Noyes, 2011), but also appears to account for unique variance in adjustment apart from these other measures (Smith et al., 2008). Internal consistency was .89.

Outcome Variables

PTSD symptoms.

The 17-item PTSD Checklist–Military Version (PCL–M; Weathers, Litz, Herman, Huska, & Keane, 1993) was administered at each measurement occasion to assess military-related PTSD symptoms during the past month according to DSM-IV criteria. Respondents indicate the degree to which they have experienced each symptom on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). The PCL-M has excellent internal consistency and validity (Blanchard, Jones-Alexander, Buckley, & Forneris, 1996; Forbes, Creamer, & Biddle, 2001). Internal consistency coefficients ranged from .96 to .97.

Depression symptoms.

The 21-item Beck Depression Inventory–II (BDI–II; Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996) was administered at each time-point. Respondents rate on a scale that ranges from 0 (does not experience the symptom) to 3 (severe experience of the symptom) the symptoms they have experienced over the past two weeks. The total score was used. Internal consistency ranged from .95 to .96.

Quality of Life.

The 16-item Quality of Life Scale (QLS; Burckhardt, Woods, Schultz, & Ziebarth, 1989) assessed subjective quality of life/life satisfaction at each measurement occasion. Respondents are instructed to rate their degree of satisfaction at the present time with an activity or a relationship on a scale that ranges from 1 (delighted) to 7 (terrible). The QLS exhibits good reliability and validity (Burckhardt & Anderson, 2003). Internal consistency ranged from .93 to .95.

Functional Disability.

The 36-item self-report version of the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Scale 2.0 (WHODAS; Üstün, 2010; Üstün et al., 2010) assessed functional disability at each time-point. Behaviorally anchored items, rated on a scale from 0 (none) to 4 (extreme/cannot do), assess function across 7 domains (understanding and communicating, getting around, getting along with people, life activities, work and school, participation in society, self-care) over the past 30 days. Respondents who have not worked or attending school in the past 30 days are instructed to skip those items. To obtain a single indicator of overall functional disability for all respondents, we computed an average item response score for subsequent analyses. Internal consistency ranged from .96 to .97.

Statistical Analyses

Preliminary analyses.

The associations among personality type (resilient vs. non-resilient), gender, race, and service-connected disability variables were estimated. Differences between personality prototypes on all other study variables were examined (Table 1) using SPSS 22.0.

Table 1.

Means and Standard Deviations Among Study Variables by Personality Prototypes (N = 264)

| Personality Prototype | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resilient (n = 138) | Non-Resilient (n = 126) | ||||

| Measure | M | SD | M | SD | p |

| TBI | |||||

| LOC | 0.48 | 0.82 | 0.55 | 0.84 | .519 |

| PTA | 0.17 | 0.48 | 0.20 | 0.51 | .663 |

| NTBI-Lifetime | 1.23 | 1.36 | 1.53 | 1.57 | .096 |

| NTBI (warzone) | 0.65 | 1.09 | 0.95 | 1.26 | .034 |

| Mediators | |||||

| BRS | 23.59 | 3.66 | 17.12 | 4.07 | <.001 |

| PDSS | 58.64 | 10.03 | 49.58 | 9.55 | <.001 |

| B-COPE Action | 10.57 | 4.26 | 9.58 | 3.37 | .042 |

| B-COPE Avoidant | 1.59 | 1.63 | 3.42 | 2.09 | <.001 |

| AAQ-II | 13.27 | 6.63 | 25.67 | 8.26 | <.001 |

| Covariates (Baseline) | |||||

| MC | 6.39 | 1.89 | 5.18 | 2.25 | <.001 |

| FCES | 17.05 | 13.98 | 20.36 | 14.58 | .068 |

| Outcomes (Baseline) | |||||

| PCL-M | 27.94 | 14.21 | 46.70 | 15.21 | <.001 |

| BDI-II | 6.85 | 8.22 | 22.46 | 15.21 | <.001 |

| QLS | 86.87 | 13.25 | 65.98 | 15.76 | <.001 |

| WHODAS 2.0 | 17.43 | 17.86 | 45.25 | 24.09 | <.001 |

| Outcomes (4-months) | |||||

| PCL-M | 28.48 | 13.46 | 48.73 | 17.72 | <.001 |

| BDI-II | 9.81 | 9.61 | 25.81 | 13.28 | <.001 |

| QLS | 85.11 | 17.29 | 60.01 | 15.40 | <.001 |

| WHODAS 2.0 | 21.63 | 20.98 | 52.93 | 25.50 | <.001 |

| Outcomes (8-months) | |||||

| PCL-M | 30.95 | 16.06 | 50.70 | 17.61 | <.001 |

| BDI-II | 10.71 | 10.77 | 26.72 | 13.45 | <.001 |

| QLS | 83.39 | 17.65 | 61.57 | 17.67 | <.001 |

| WHODAS 2.0 | 24.14 | 22.95 | 54.31 | 25.78 | <.001 |

| Outcomes (12-months) | |||||

| PCL-M | 27.45 | 13.59 | 44.90 | 17.55 | <.001 |

| BDI-II | 7.81 | 9.74 | 21.26 | 12.52 | <.001 |

| QLS | 86.72 | 15.75 | 65.65 | 15.67 | <.001 |

| WHODAS 2.0 | 19.03 | 20.70 | 44.94 | 26.52 | <.001 |

Note. WHODAS 2.0 scores are the sum of all items. Mean scores differences were examined by conducting independent sample t-tests. LOC = Worst loss of consciousness rating coded as 0 (no LOC), 1 (less than 1 minute), 2 (1 to 15 minutes), or 3 (16 to 30 minutes); PTA = Worst posttraumatic amnesia rating coded as 0 (no PTA occurred), 1 (less than 1 hour of PTA), or 2 (1 to 24 hours of PTA; NTBI = Lifetime number of traumatic brain injuries including civilian and military; NTBI (warzone) = Number of TBIs during post-9/11 warzone deployment; BRS = Brief Resilience Scale; PDSS = Post-deployment Social Support Scale; B-COPE Action = Brief COPE Active coping factor score; B-COPE Avoidant = Brief COPE Avoidant coping factor score; AAQ-II = Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II; MC = Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale; FCES = Full Combat Exposure Scale; PCL-M = PTSD checklist-military version; BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory-II; QLS = Quality of Life Scale; WHODAS = World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0.

Path Model.

Path analyses under the structural equation modeling (SEM) framework were utilized to test the hypothesized model (Figure 2) using Mplus 7.1 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012). Personality prototypes and the TBI variables were positioned as exogenous variables to directly predict the four outcome variables (PCL-M, BDI-II, QLS, and WHODAS) across time-points (baseline, 4-, 8-, and 12-months). The effects from the predictors to the outcomes were assumed to be mediated by social support (PDSS), action-oriented and avoidant coping (Brief COPE), psychological flexibility (AAQ-II), and self-reported resilience (BRS). Combat exposure and social desirability were treated as covariates and were assumed to have direct effects on all other study variables. Mediators were allowed to correlate with each other. Outcomes were allowed to correlated with each other over time.

Figure 2.

Saturated a priori model of personality prototypes, TBI and mediating characteristics predicting adjustment over 12-months.

Note: The covariates were assumed to have direct effects on TBI variables, personality type, mediators and outcomes. Mediators were allowed to correlate with each other. Outcomes were allowed to correlated with each other over time. FCES = Full Combat Exposure Scale; MC = Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale; NTBI = Lifetime number of traumatic brain injuries including civilian and military; PTA = Worst posttraumatic amnesia rating; LOC = Worst loss of consciousness rating; NTBI (warzone) = Number of TBIs during post-9/11 warzone deployment; BRS = Brief Resilience Scale; PDSS = Postdeployment Social Support Scale; AAQ-II = Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II; B-COPE Action = Brief COPE Active coping factor score; B-COPE Avoidant = Brief COPE Avoidant coping factor score; PCL-M = PTSD Checklist-Military Version; BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory-II; QLS = Quality of Life Scale; WHODAS = World Health Organization Disability Assessment Scale 2.0.

The path model was evaluated with the following criteria: χ2 test ≥ .05, comparative fit index (CFI) and Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) ≥ .95 (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Yu, 2002), root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) ≤ .08 (Browne & Cudeck, 1992), and standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR) ≤ .08 (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Missing data were accommodated with the maximum likelihood estimation method to utilize all available information. The overall R2 values were estimated for each outcome across time. Effect sizes were interpreted using the cutoffs of .02, .15, and .35 as small, medium, and large, respectively (Cohen, 1995). Direct and indirect effects were examined, and 1000 bootstrapping samples were produced to estimate the 95% confidence interval for the indirect effects (Preacher & Hayes, 2008).

Results

Ninety percent of the participants completed the assessments at each measurement occasion. Preliminary χ2 tests of independence found that personality type was not associated with gender [χ2(1) = 1.36, ns], race/ethnicity [χ2(3) = 2.89, ns], or receipt of service-connected disability [χ2(1) = 2.68, ns].

Independent sample t-test results showed that personality prototypes were associated with number of warzone-related mTBIs (p < .05): Veterans with a non-resilient prototype had more mTBIs. All mediators were associated with personality prototype (p values < .05). Veterans with a resilient prototype reported more social support, more action-oriented coping, greater psychological flexibility, higher self-perceived resilience and less avoidant coping. The resilient group also had significantly higher social desirability scores. Combat exposure was not significantly associated with personality prototype. Personality prototypes were associated with the four outcome variables at each time-point (p values < .001). Veterans with a resilient prototype reported lower PTSD and depression symptoms and functional disability, and higher quality of life than veterans with a non-resilient prototype. The average BDI-II scores for the non-resilient group were indicative of “moderate depression” at every time-point (scores of 20 to 28; Beck et al., 1996). Similarly, the average PCL-M scores for the non-resilient group approached the recommended cut-off score of 50 that is often used to indicate a positive screen for PTSD among military personnel (and consistently exceeded a cut-off score of 38 that has good sensitivity with clinician diagnoses of PTSD among Iraq/Afghanistan veterans; Tsai, Pietrzak, Hoff, & Harpaz-Rotem, 2016). While firm interpretive guidelines for the WHODAS 2.0 in this population are needed (Konecky, Meyer, Marx, Kimbrel, Morissette, 2014), one recent study that combined several independent veteran samples identified a cutoff score on the WHODAS 2.0 that may differentiate between veterans with and without PTSD-related functional impairment (Bovin et al., 2019). The non-resilient and resilient groups in the current study scored well above and below this cutoff score, respectively, providing some evidence that these groups exhibited clinically meaningful differences in functional disability.

Path Analysis

In the saturated model, two direct effects -- total number of lifetime mTBIs to self-reported resilience and total number of lifetime mTBIs to active coping -- were non-significant and had effect sizes close to zero. Hence, these two paths were fixed to zero in the corrected model. The corrected model had excellent fit: χ2(2) = 0.019, p = 0.990; CFI = 1.00; TLI = 1.00; RMSEA = .000 (90% CI: [.000, .000]); SRMR = .001.

Direct effects.

We analyzed three types of direct effects: from predictors to mediators; from mediators to outcome variables; from predictors to outcome variables, as well as the indirect effects from predictors to outcomes through mediators. All effects accounted for combat exposure and social desirability and are described using standardized path coefficients. Statistically significant (p < .05) direct effects are depicted in Figures 3a to 3d for the four outcome variables.

Figure 3a.

Path model of personality prototype, traumatic brain injury variables, and mediating characteristics predicting PTSD Checklist-Military Version (PCL-M) scores across four time points. R2 = 52.4% – 72.4%

Note: Only statistically significant direct effects denoted by using standardized path coefficients were shown. The covariates were assumed to have direct effects on TBI variables, personality type, mediators and outcomes. Mediators were allowed to correlate with each other. Outcomes were allowed to correlate with each other over time. FCES = Full Combat Exposure Scale; MC = Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale; NTBI = Lifetime number of traumatic brain injuries including civilian and military; PTA = Worst posttraumatic amnesia rating; LOC = Worst loss of consciousness rating; NTBI (warzone) = Number of TBIs during post-9/11 warzone deployment; BRS = Brief Resilience Scale; PDSS = Postdeployment Social Support Scale; AAQ-II = Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II; B-COPE Action = Brief COPE Active coping factor score; B-COPE Avoidant = Brief COPE Avoidant coping factor score.

Figure 3d.

Path model of personality prototype, traumatic brain injury variables, and mediating characteristics predicting World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 (WHODAS) scores across four time points. R2 = 40.8% – 58.1%

Note: Only statistically significant direct effects denoted by using standardized path coefficients are shown. The covariates were assumed to have direct effects on TBI variables, personality type, mediators and outcomes. Mediators were allowed to correlate with each other. Outcomes were allowed to correlate with each other over time. FCES = Full Combat Exposure Scale; MC = Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale; NTBI = Lifetime number of traumatic brain injuries including civilian and military; PTA = Worst posttraumatic amnesia rating; LOC = Worst loss of consciousness rating; NTBI (warzone) = Number of TBIs during post-9/11 warzone deployment; BRS = Brief Resilience Scale; PDSS = Postdeployment Social Support Scale; AAQ-II = Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II; B-COPE Action = Brief COPE Active coping factor score; B-COPE Avoidant = Brief COPE Avoidant coping factor score.

Personality prototype was associated with all mediators except action-oriented coping. Compared with the resilient group, the non-resilient prototype was associated with lower self-reported resilience, social support, and psychological flexibility, and with greater avoidant coping (all p’s < .05). In contrast, only two significant effects were observed among the TBI variables: the number of warzone-related mTBIs was negatively associated with psychological flexibility and social support (p’s < .05).

The resilient personality prototype predicted lower PTSD and depression symptoms and functional disability and higher quality of life over time (p’s < .05). The number of lifetime TBIs, and the worst PTA and LOC ratings were not associated with the four outcome variables at any time with two exceptions: the worst PTA predicted 8-month PTSD and the worst LOC predicted baseline QOL. The number of warzone-related mTBIs was associated with greater functional disability at each time point.

Several mediators were directly predictive of outcome variables. As depicted in Figure 3a, psychological flexibility was associated with lower PTSD symptoms at all four time-points (p’s < .01) and social support was associated with lower PTSD at three time-points (p’s < .01). Avoidant coping was associated with greater PTSD at three time-points (p’s < .05). Psychological flexibility was consistently negatively associated with depression over time, and avoidant coping was consistently positively associated with depression over time (p’s < .01; Figure 3b). Social support was related to lower depression at baseline and 4-months (p’s < .05). Higher self-reported resilience (as measured by the BRS) and psychological flexibility predicted higher quality of life across time (p’s < .05; Figure 3c). Social support was positively associated with quality of life at baseline, 4-, and 12-month follow-up (p’s < .05). Psychological inflexibility also predicted greater functional disability at all time-points (p’s < .05; Figure 3d). Lower social support predicted greater functional disability at baseline, 4-, and 12-months.

Figure 3b.

Path model of personality prototype, traumatic brain injury variables, and mediating characteristics predicting Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) scores across four time points. R2 = 47.4% – 68.7%

Note: Only statistically significant direct effects denoted by using standardized path coefficients are shown. The covariates were assumed to have direct effects on TBI variables, personality type, mediators and outcomes. Mediators were allowed to correlate with each other. Outcomes were allowed to correlate with each other over time. FCES = Full Combat Exposure Scale; MC = Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale; NTBI = Lifetime number of traumatic brain injuries including civilian and military; PTA = Worst posttraumatic amnesia rating; LOC = Worst loss of consciousness rating; NTBI (warzone) = Number of TBIs during post-9/11 warzone deployment; BRS = Brief Resilience Scale; PDSS = Postdeployment Social Support Scale; AAQ-II = Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II; B-COPE Action = Brief COPE Active coping factor score; B-COPE Avoidant = Brief COPE Avoidant coping factor score.

Figure 3c.

Path model of personality prototype, traumatic brain injury variables, and mediating characteristics predicting Quality of Life Scale (QLS) scores across four time points. R2 = 39.2% – 59.3%

Note: Only statistically significant direct effects denoted by using standardized path coefficients are shown. The covariates were assumed to have direct effects on TBI variables, personality type, mediators and outcomes. Mediators were allowed to correlate with each other. Outcomes were allowed to correlate with each other over time. FCES = Full Combat Exposure Scale; MC = Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale; NTBI = Lifetime number of traumatic brain injuries including civilian and military; PTA = Worst posttraumatic amnesia rating; LOC = Worst loss of consciousness rating; NTBI (warzone) = Number of TBIs during post-9/11 warzone deployment; BRS = Brief Resilience Scale; PDSS = Postdeployment Social Support Scale; AAQ-II = Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II; B-COPE Action = Brief COPE Active coping factor score; B-COPE Avoidant = Brief COPE Avoidant coping factor score.

Indirect effects.

Psychological flexibility partially mediated the association between personality prototype and PTSD across time (p’s < .001). Social support and avoidant coping each partially mediated the association between personality and PTSD at three time-points (p’s < .01). Compared with the resilient prototype, the non-resilient group had higher PTSD scores through lower psychological inflexibility, lower social support, and greater use of avoidant coping. Number of warzone-related mTBIs was associated with higher PTSD through its association with psychological inflexibility across time (p’s < .05).

The association between the non-resilient prototype and higher depression was partially mediated by both avoidant coping and psychological inflexibility across time (all p’s < .01). Higher depression scores in the non-resilient group were also partially mediated by lower social support at baseline and 4-months (both p’s < .05). Psychological inflexibility mediated the effect of number of warzone-related mTBI on greater depression scores at each time point (all p’s < .05).

Partial mediation of psychological flexibility on the personality-quality of life relationship occurred at all time-points (p’s < .05), and by social support and self-reported resilience at three time-points (p’s < .05). A resilient prototype predicted higher QOL through its beneficial associations with psychological flexibility, higher social support and greater self-perceptions of personal resilience. Lower psychological flexibility mediated the relationship between greater number of warzone-related mTBIs and lower QOL at baseline and 4-months (p’s < .05).

Psychological inflexibility also partially mediated the personality-functional disability relationship at every measurement occasion (p’s < .01). Social support partially mediated this relationship at three time-points (p’s < .05). The non-resilient prototype reported greater disability through lower psychological flexibility and social support. Avoidant coping partially mediated the effect of personality prototype on functional disability at baseline and 12-months (p’s < .01). Similarly, greater psychological inflexibility partially mediated the effects of a greater number of warzone-related mTBIs on greater functional disability across time-points (all p’s < .05).

R2 values indicative of large effect sizes were observed for each outcome variable in the final model. The model accounted for 52% to 72% of the variance in PTSD across each measurement, 47% to 69% of the variance in depression across time, 39% to 59% of the variance in QOL, and 41% to 58% of the variance in functional disability.

Discussion

Consistent with the Block conceptualization of ego resilience and control, veterans with a resilient personality prototype exhibited fewer problems with PTSD, depression, and functional disability, and reported greater QOL over the course of a year, compared to veterans who were not resilient. This “person-centered” approach to personality research provides support for studying “normal,” non-pathological personality factors in veteran adjustment, as our findings reveal valuable insights into several behavioral mechanisms that account for differences in veteran adjustment. Consistent with our theoretical expectations, resilience facilitated adjustment on all outcome variables at all time points through its beneficial association with psychological flexibility. Indirect effects through higher social support and less avoidant coping and in a few cases, with a measure of perceived abilities to “bounce back” in time of stress, reflect characteristics that typify the resilient prototype: Enduring capacities for personal and social relationships and self-regulation that foster a sense of confidence, self-esteem, and self-efficacy (Farkas & Orosz, 2015).

The consistency of the direct effects from the resilient prototype to each outcome variable independent of the mediating variables suggest that other mechanisms associated with the prototype may also facilitate veteran adjustment (e.g., capacities for positive emotions, active engagement with the environment). These particular mechanisms are part of the constellation of adaptive qualities associated with ego resiliency and control that are measured, in part, by the separate traits that constitute the resilient prototype. Higher Extraversion is associated with sociability and positive emotions, and higher Conscientiousness has been associated with active engagement and goal-directed activity among persons with disabling conditions (Elliott et al., in press). These two traits are also associated with the higher-order personality factors of stability (Conscientiousness) and plasticity (Extraversion) that are represented in the resilient prototype (DeYoung, 2006; Farkas & Orosz, 2015).

Moreover, the results of this study indicate that the effects of resilience, social support, and psychological flexibility on optimal adjustment occurred regardless of mTBI history. Of the TBI variables in the model, the number of warzone-related mTBIs had a direct effect on functional disability, and its association with PTSD, depression and functional disability was mediated by its relationship with psychological inflexibility. Although research has found multiple mTBIs to be associated with veteran distress (Dretsch et al., 2015; Spira, Lathan, Bleiberg, & Tsao, 2014), critical observers argue that the research concerning the “cumulative effects of multiple mTBIs” is equivocal (Rohling et al., 2017; p. 160). Our findings do not resolve these issues, but perhaps imply that the negative effects of multiple mTBIs may appear when studied in the context of additional factors such as combat exposure, personality characteristics, and specific behaviors. Thus, our results may reflect the “burden of adversity” in which multiple factors, including premorbid factors, personal history (including combat exposure), and comorbidities, affect symptom reporting among veterans with deployment-related mTBI and PTSD (Brenner, Vanderploeg, & Terrio, 2009).

Brenner et al. (2009) recommended the use of evidence-based interventions to treat veteran distress regardless of etiology, and recent work suggests that cognitive-behavioral interventions may be more effective in alleviating post-concussive symptoms associated with mTBI than cognitive rehabilitation strategies (Vanderploeg, Belanger, Curtiss, Bowles, & Cooper, 2019). Our results suggest that there are pathways common to both personality prototypes and mTBIs incurred during warzone-deployment that impact symptom reports of PTSD, depression, and functional impairment. Of particular interest is the critical role of psychological flexibility in our model as a significant mediator and predictor of veteran adjustment. Arguably a transdiagnostic concept relevant to an array of psychopathological conditions, psychological flexibility is a central mechanism of change in Acceptance and Commitment therapy (ACT; Hayes et al., 2006), and its properties parallel those associated with ego-resiliency (Kashdan & Rottenberg, 2010). Rather than focus on symptom reduction, ACT intends to increase psychological flexibility by helping a person to remain present in the moment, accept uncomfortable, distressing internal and external experiences, and persist in activities and behaviors consistent with their values and goals, without avoiding the internal stimuli or the contextual demands (Hayes et al., 2006). The theoretical properties of psychological flexibility and its pivotal role in ACT distinguish it from cognitive flexibility, a component of executive function recognized in neuropsychological research and in TBI rehabilitation (Whiting, Deane, Simpson, McLeod, & Ciarrochi, 2017). Moreover, the evidence to date – including the results of the present study – suggests that it warrants consideration in psychological interventions with veterans with mTBI specifically, (Whiting et al., 2017), and polytrauma, generally (e.g., Cook et al., 2015). Clinical interventions that address interpersonal skills and social competence may prevent a downward spiral in relationship quality and well-being (Diener et al., 2017) and in the process, promote social and interpersonal ties and corresponding experiences of positive emotion that characterize personal resilience (Kok & Fredrickson, 2014).

There are several limitations to this study. The sample was predominately male and Caucasian, and enrolled in a specific VA healthcare system, which may limit generalizability. Predeployment personality data were not available; we cannot readily dismiss concerns about possible personality changes following warzone service. The indicators of PTSD and depression reflect symptom reports, and these should not be interpreted as actual diagnostic conditions. Interpretive guidelines for use of the WHODAS 2.0 are needed across populations, including in war veterans, to facilitate making strong inferences about the relative degree of functional impairment reported by the non-resilient group (Konecky et al., 2014). Our model included mediators that were assessed at the time we obtained personality data. Consequently, the observed relationships among the variables assessed at baseline reflect atemporal associations, precluding strong inferences about mediation (Winer et al., 2016).

Our reliance on the “person-centered” use of personality prototypes varies from the traditional trait-based approach, and clustering prototypes can, at times, result in sample-specific configurations (Donnellan & Robins, 2010). To a great extent, this issue was circumvented by restricting our theoretical and clinical focus to two prototypes -- resilient and non-resilient – rather than the three that are usually studied in the relevant literature. Controversies about the incremental and predictive validity of the prototypes versus the traditional use of specific traits are contentious and unresolved. In the current study, we were invested in a theoretical model from which we could conceptualize, anticipate, and test relationships that would have implications for psychological interventions. In contrast, the use of isolated traits in clinical research sometimes provides “…little information about the internal psychological mechanisms…that could be the target of change” in psychological interventions (Shadel, 2010; p. 336). In addition, the person-centered approach that guided our study helped us avoid the tautology that plagues the use of self-report, face-valid measures of resilience in studies of distress. Longitudinal research finds that responses to these instruments fluctuate with changes in emotional well-being and social support over time (positive or negative; Laird et al., in press) and the predictive value of these instruments diminishes in contextual models that account for stable personality factors and other behavioral and social characteristics (Elliott et al., 2015).

Our findings provide additional evidence that a resilient personality prototype serves a protective function, endowing a veteran with several adaptive characteristics that facilitate their adjustment. Veterans who have personality characteristics associated with a non-resilient prototype lack personal and social resources that, in turn, undermines their psychological adjustment and quality of life, and contributes to impairment in everyday roles and activities. Additional research is needed to demonstrate the effectiveness of interventions that target the mechanisms of change identified in this study – psychological flexibility and social support, in particular – in promoting veteran resilience.

Table 2.

Standardized Path Coefficients and 95% Confidence Interval (CI) of Indirect Effects of Personality Subtypes and Number of mTBIs Incurred During Deployment on the Outcome Variables Over Time

| Baseline | 4-months | 8-months | 12-months | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | CI | Estimate | CI | Estimate | CI | Estimate | CI | |

| PCL-M | ||||||||

| Non-Resilient → BRS → | −0.08 | [−0.20, 0.05] | 0.07 | [−0.04, 0.19] | 0.06 | [−0.03, 0.15] | 0.05 | [−0.05, 0.14] |

| Non-Resilient → PDSS → | 0.02 | [−0.07, 0.11] | 0.07* | [0.01, 0.13] | 0.05* | [0.00, 0.10] | 0.05* | [0.00, 0.10] |

| Non-Resilient → B-COPE Action → | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.04] | −0.01 | [−0.02, 0.01] | 0.00 | [−0.01, 0.02] | −0.01 | [−0.03, 0.01] |

| Non-Resilient → B-COPE Avoidant → | 0.09* | [0.02, 0.17] | 0.02 | [−0.04, 0.08] | 0.05* | [0.00, 0.11] | 0.06* | [0.01, 0.11] |

| Non-Resilient → AAQ-II → | 0.32** | [0.18, 0.45] | 0.18** | [0.08, 0.28] | 0.17** | [0.08, 0.26] | 0.19** | [0.09, 0.28] |

| NTBI(warzone) → PDSS → | 0.01 | [−0.03, 0.04] | 0.03 | [−0.01, 0.07] | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.05] | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.05] |

| NTBI(warzone)→ AAQ-II → | 0.09* | [0.01, 0.17] | 0.05* | [0.00, 0.10] | 0.04* | [0.00, 0.09] | 0.05* | [0.00, 0.10] |

| BDI-II | ||||||||

| Non-Resilient → BRS → | 0.01 | [−0.07, 0.09] | 0.07 | [−0.02, 0.15] | 0.08 | [−0.02, 0.17] | 0.03 | [−0.08, 0.13] |

| Non-Resilient → PDSS → | 0.05* | [0.01, 0.09] | 0.06* | [0.01, 0.11] | 0.02 | [−0.03, 0.07] | 0.05 | [−0.01, 0.10] |

| Non-Resilient → B-COPE Action → | 0.01 | [−0.01, 0.03] | 0.01 | [−0.01, 0.02] | 0.01 | [−0.01, 0.03] | 0.00 | [−0.01, 0.02] |

| Non-Resilient → B-COPE Avoidant → | 0.09** | [0.04, 0.14] | 0.07* | [0.02, 0.12] | 0.07* | [0.01, 0.13] | 0.09* | [0.03, 0.16] |

| Non-Resilient → AAQ-II → | 0.27** | [0.19, 0.36] | 0.20** | [0.12, 0.29] | 0.16** | [0.07, 0.25] | 0.17** | [0.06, 0.27] |

| NTBI(warzone) → PDSS → | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.04] | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.05] | 0.01 | [−0.02, 0.03] | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.05] |

| NTBI(warzone) → AAQ-II → | 0.08* | [0.00, 0.15] | 0.06* | [0.00, 0.11] | 0.04* | [0.00, 0.09] | 0.05* | [0.00, 0.10] |

| QLS | ||||||||

| Non-Resilient → BRS → | −0.09* | [−0.16, −0.02] | −0.10* | [−0.18, −0.02] | −0.09 | [−0.19, 0.00] | −0.11* | [−0.22, −0.01] |

| Non-Resilient → PDSS → | −0.07* | [−0.12, −0.02] | −0.08* | [−0.13, −0.02] | −0.03 | [−0.09, 0.03] | −0.06* | [−0.13, −0.00] |

| Non-Resilient → B-COPE Action → | −0.02 | [−0.04, 0.01] | −0.01 | [−0.03, 0.01] | −0.01 | [−0.03, 0.01] | −0.01 | [−0.02, 0.01] |

| Non-Resilient → B-COPE Avoidant → | −0.02 | [−0.07, 0.02] | −0.04 | [−0.08, 0.01] | −0.04 | [−0.09, 0.02] | −0.04 | [−0.09, 0.02] |

| Non-Resilient → AAQ-II → | −0.23** | [−0.32, −0.15] | −0.15** | [−0.22, −0.07] | −0.09* | [−0.19, −0.01] | −0.10* | [−0.20, −0.00] |

| NTBI(warzone) → PDSS → | −0.03 | [−0.06, 0.01] | −0.03 | [−0.07, 0.01] | −0.01 | [−0.04, 0.02] | −0.02 | [−0.06, 0.02] |

| NTBI(warzone) → AAQ-II → | −0.07* | [−0.13, −0.00] | −0.04* | [−0.08, −0.00] | −0.03 | [−0.06, −0.0H | −0.03 | [−0.07, 0.0H |

| WHODAS | ||||||||

| Non-Resilient → BRS → | 0.08* | [0.00, 0.17] | 0.08 | [−0.01, 0.17] | 0.08 | [−0.02, 0.19] | 0.01 | [−0.08, 0.09] |

| Non-Resilient → PDSS → | 0.05* | [0.00, 0.10] | 0.07* | [0.02, 0.13] | 0.03 | [−0.03, 0.10] | 0.05* | [0.00, 0.11] |

| Non-Resilient → B-COPE Action → | 0.01 | [−0.01, 0.02] | 0.01 | [−0.01, 0.03] | 0.00 | [−0.02, 0.02] | 0.01 | [−0.01, 0.02] |

| Non-Resilient → B-COPE Avoidant → | 0.08* | [0.03, 0.13] | 0.04 | [−0.02, 0.09] | 0.03 | [−0.02, 0.09] | 0.11** | [0.04, 0.17] |

| Non-Resilient → AAQ-II → | 0.16** | [0.08, 0.24] | 0.16** | [0.07, 0.26] | 0.12* | [0.02, 0.23] | 0.16** | [0.06, 0.26] |

| NTBI(warzone) → PDSS → | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.05] | 0.03 | [−0.01, 0.06] | 0.01 | [−0.02, 0.04] | 0.02 | [−0.02, 0.06] |

| NTBI(warzone) → AAQ-II → | 0.04* | [0.00, 0.09] | 0.05* | [0.00, 0.09] | 0.03* | [0.00, 0.07] | 0.04* | [0.00, 0.09] |

Note. Resilient personality prototype is the reference group. PCL-M = PTSD Checklist-Military Version; BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory-II; QLS = Quality of Life Scale; WHODAS = World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0; BRS = Brief Resilience Scale; PDSS = Post-deployment Social Support Scale; AAQ-II = Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II; NTBI (warzone) = Number of TBIs during post-9/11 warzone deployment.

p < .05,

p < .001

Impact.

The present study indicates that the beneficial effects of a resilient personality prototype occur among warzone veterans with and without mTBI.

Several of the characteristics associated with a resilient personality prototype can be addressed in psychological interventions to facilitate psychological adjustment of veterans who are experiencing difficulties with depression, post-traumatic stress symptoms, and quality of life.

Of these characteristics, psychological flexibility appears to be a particularly important mechanism through which resilience promotes adjustment, and psychological flexibility is a central element of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Merit Award #I01RX000304-01 to Dr. Morissette and #I01RX000304-04 to Drs. Meyer and Morissette from the Rehabilitation Research and Development (R&D) Service. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.

Footnotes

The present study is one in a series from the Project SERVE FX collaboration. An earlier version of this work was presented by the first author at the 19th annual Rehabilitation Psychology Conference conducted in Albuquerque, NM, in February, 2017. A complete list of all papers and presentations from the Project SERVE FX collaboration is available from Sandra Morissette at Sandra.Morissette@utsa.edu or from Eric Meyer at Eric.Meyer2@va.gov.

Contributor Information

Timothy R. Elliott, Texas A&M University

Yu-Yu Hsiao, University of New Mexico.

Nathan A. Kimbrel, Durham Veterans Affairs Medical Center, VA Mid-Atlantic Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center, and Duke University Medical Center

Bryann B. DeBeer, VA VISN 17 Center of Excellence for Research on Returning War Veterans, Central Texas Veterans Healthcare System, & Texas A&M University Health Science Center

Suzy Bird Gulliver, Warriors Research Institute at Baylor Scott & White Health, & Texas A&M University Health Science Center.

Oi-Man Kwok, Texas A&M University.

Sandra B. Morissette, The University of Texas at San Antonio

Eric C. Meyer, VA VISN 17 Center of Excellence for Research on Returning War Veterans, Central Texas Veterans Healthcare System, Texas A&M University Health Science Center, Warriors Research Institute at Baylor Scott & White Health

References

- Alessandri G, Vecchione M, Donnellan BM, Eisenberg N, Caprara GV, & Cieciuch J (2014). On the cross-cultural replicability of the resilient, undercontrolled and overcontrolled personality types. Journal of Personality, 82, 340–353. doi: 10.1111/jopy.12065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alosco ML, Aslan M, Du MM, Ko J, Grande L,… & Vasterling JJ (2016). Consistency of recall for deployment-related traumatic brain injury. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 31, 360–368. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0000000000000201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine (1993). Definition of mild traumatic brain injury. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 8, 86–87. [Google Scholar]

- Asendorpf JB, Borkenau P, Ostendorf F, & Van Aken MA (2001). Carving personality description at its joints: Confirmation of three replicable personality prototypes for both children and adults. European Journal of Personality, 15, 169–198. DOI: 10.1002/per.408 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bailie JM, Kennedy JE, French LM, Marshall K, Prokhorensko O, Asumssen S, …& Lange RT (2016). Profile analysis of the neurobehavioral and psychiatric symptoms following combat-related mild traumatic brain injury: Identification of subtypes. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 31, 2–12. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0000000000000142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, & Brown GK (1996). Beck Depression Inventory manual (2nd ed.). San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW, Elliott TR, & Rivera P (2007). Resilient, undercontrolled, and overcontrolled personality prototypes among persons with spinal cord injury. Journal of Personality Assessment, 89, 292–302. doi: 10.1080/00223890701629813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard EB, Jones-Alexander J, Buckley TC, & Forneris CA (1996). Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist (PCL). Behaviour Research and Therapy, 34, 669–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block J (1993). Studying personality the long way. In Funder DC, Parke RD, Tomlinson-Keasey C, & Widaman K (Eds.), Studying lives through time (pp. 9–41). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Block JH, & Block J (1980). The role of ego control and ego resiliency in the organization of behavior. In Collins WA (Ed.), The Minnesota symposium on child psychology: Vol. 13. Development of cognition, affect, and social relations (pp. 39–101). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Mancini AD, Horton JL, Powell TM, LeardMann CA, Boyko EJ, …for the Millenium Cohort Study Team. (2012). Trajectories of trauma symptoms and resilience in deployed US military service members: Prospective cohort study. British Journal of Psychiatry, 200, 317–323. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.096552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond FW, Hayes SC, Baer RA, Carpenter KM, Guenole N Orcutt HK, … Zettle RD (2011). Preliminary psychometric properties of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire—II: A revised measure of psychological flexibility and experiential avoidance. Behavior Therapy, 42, 676–688. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2011.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bovin MJ, Meyer EC, Kimbrel NA, Kleiman SE, Green JD, Morissette SB, & Marx BP (2019). Using the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 to assess disability in veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner LA, Vanderploeg RD, & Terrio H (2009). Assessment and diagnosis of mild traumatic brain injury, posttraumatic stress disorder, and other polytrauma conditions: Burden of adversity hypothesis. Rehabilitation Psychology, 54, 239–246. doi: 10.1037/a0016908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brickell TA, Lange RT, & French LM (2014). Health-related quality of life within the first 5 years following military-related concurrent mild traumatic brain injury and polytrauma. Military Medicine, 179, 827–838. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-13-00506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broshek DK, De Marco AP, & Freeman JR (2015). A review of post-concussion syndrome and psychological factors associated with concussion. Brain Injury, 29, 228–237. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2014.974674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, & Cudeck R (1992). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociological Methods & Research, 21(2), 230–258. [Google Scholar]

- Burckhardt CS, & Anderson KL (2003). The quality of life scale (QOLS): Reliability, validity and utilization. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 1, 60. http://www.hqlo.com/content/1/1/60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burckhardt CS, Woods SL, Schultz AA, & Ziebarth DM (1989). Quality of life of adults with chronic illness: a psychometric study. Research in Nursing & Health, 12, 347–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll LJ, Cassidy D, Cancelliere C, Cote P, Hincapie CA,…Hartvigsen J (2014). Systematic review of the prognosis after mild traumatic brain injury in adults: Cognitive, psychiatric, and mortality outcomes: Results of the International Collaboration on mild traumatic brain injury prognosis. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 95, S152–S173. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2013.08.300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS (1997). You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: Consider the Brief COPE. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 4, 92–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, (2000). The child is the father of the man: Personality continuities from childhood to adulthood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78, 158–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cifu DX, Taylor BC, Carne WF, Bidelspach DE, Sayer NA, Scholten J, & Hagel E (2014). TBI, PTSD and pain diagnoses in Iraq and Afghanistan conflict veterans. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development, 50, 1169–1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J (1995). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112, 155–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook AJ, Meyer EC, Evans LD, Vowles KE, Klocek JW, Kimbrel NA, Gulliver SB, & Morissette SB (2015). Chronic pain acceptance incrementally predicts disability in polytrauma-exposed veterans at baseline and 1-year follow-up. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 73, 25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2015.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT Jr., & McCrae RR (1992). Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO–PI–R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO–FFI) professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Davydov DM, Stewart R, Ritchie K, & Chaudrieu I (2010). Resilience and mental health. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 479–495. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center. (2019). DoD worldwide numbers for TBI. Retrieved from https://dvbic.dcoe.mil/dod-worldwide-numbers-tbi.

- Dennissen JA, Asendorpf JB, & van Aken MAG (2008). Childhood personality predicts long-term trajectories of shyness and aggressiveness in the context of demographic transitions in emerging adulthood. Journal of Personality, 76, 67–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2007.00480.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeYoung CE (2006). Higher-order factors of the big five in a multi-informant sample. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91, 1138–1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Heintzelman SJ, Kushlev K, Tay L, Wirtz D, Lutes L, & Oishi S (2017). Findings all psychologists should know from the new science on subjective well-being. Canadian Psychology, 58, 87–104. DOI: 10.1037/cap0000063 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Donnellan MB, & Robins RW (2010). Resilient, overcontrolled, and undercontrolled personality types: Issues and controversies. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 4, 1070–1083. DOI: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00313.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dretsch MN, Silverberg ND, & Iverson GL (2015). Multiple past concussions are associated with ongoing post-concussive symptoms but not cognitive impairment in active-duty army soldiers. Journal of Neurotrauma, 32, 1301–1306. doi: 10.1089/neu.2014.3810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott T, Barron L, Stein K, Wright E, & Lowery L (in press). Personality and disability: A scholarly tapestry from disparate threads. In Dunn D (Ed.), The social psychology of disability and rehabilitation. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott T, Hsiao YY, Kimbrel N, Meyer E, DeBeer B, Gulliver S, Kwok OM, & Morissette S (2015). Resilience, traumatic brain injury, depression and posttraumatic stress among Iraq/Afghanistan war veterans. Rehabilitation Psychology, 60, 263–276. doi: 10.1037/rep0000050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farkas D, & Orosz G (2015). Ego resilience reloaded: A three-component model of general resiliency. PLOS One, 10(3). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes D, Creamer M, & Biddle D (2001). The validity of the PTSD checklist as a measure of symptomatic change in combat-related PTSD. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 39, 977–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulton JJ, Calhoun PS, Wagner HR, Schry AR, Hair LP, Feeling N, … & Beckham JC (2015). The prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder in Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom (OEF/OIF) Veterans: A meta-analysis. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 31, 98–107. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2015.02.00 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gramzow RH, Sedikides C, Panter AT, Sathy V, Harris J, & Insko CA (2004). Patterns of self-regulation and the big five. European Journal of Personality, 18, 367–385. [Google Scholar]

- Grosso JA, Kimbrel NA, Dolan S, Meyer EC, Kruse MI, Gulliver SB, & Morissette SB (2014). A test of whether coping styles moderate the effect of PTSD symptoms on alcohol outcomes. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 27, 478–482. doi: 10.1002/jts.21943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC, Strosahl K, Wilson KG, Bissett RT, Pistorello J, Toarmino D, … McCurry SM (2004). Measuring experiential avoidance: A preliminary test of a working model. The Psychological Record, 54, 553–578. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC, Luoma J, Bond F, Masuda A, & Lillis J (2006). Acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, processes, and outcomes. Behavior and Research Therapy, 44(1), 1–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoge CW, Castro CA, Messer SC, McGurk D, Cotting DI, & Koffman RL (2004). Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems, and barriers to care. New England Journal of Medicine, 351, 12–22. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa040603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L-T, & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Isaacs K, Mota NP, Tsai J, Harpaz-Rotem I, Cook JM,…Pietrzak RH (2017). Psychological resilience in U.S. military veterans: A 2-year, nationally representative prospective cohort study. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 84, 301–309. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones A, Ingram MV, & Ben-Porath YS (2012). Scores on the MMPI-2-RF scales function of increasing levels of failure on cognitive symptom validity tests in a military sample. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 26, 790–815. doi: 10.1080/13854046.2012.693202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurik SM, Crocker LD, Keller AV, Hoffman SN, Bomyea J,…Jak AJ (in press). The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2-RF in treatment-seeking veterans with history of mild traumatic brain injury. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acy048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan TB, & Rottenberg J (2010). Psychological flexibility as a fundamental aspect of health. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 865–878. DOI: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy JE, Cooper DB, Reid MW, Tate DF, & Lange RT (2015). Profile analyses of the personality assessment inventory following military-related traumatic brain injury. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 30, 236–247. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acv014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King LA, King DW, Vogt DS, Knight J, & Samper RE (2006). Deployment Risk and Resilience Inventory: A collection of measures for studying deployment-related experiences of military personnel and veterans. Military Psychology, 18, 89–120. DOI: 10.1207/s15327876mp1802_1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kok BE, & Fredrickson BL (2014). Wellbeing begins with “we”: The physical and mental health benefits of interventions that increase social closeness. In Huppert FA & Cooper CI (Eds.), Interventions and policies to enhance wellbeing: Wellbeing: A complete reference guide , Volume VI (pp. 277–306). Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Konecky B, Meyer EC, Marx BP, Kimbrel NA, & Morissette SB (2014). Using the WHODAS 2.0 to assess functional disability associated with DSM-5 mental disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171, 818–820. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14050587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird V, Elliott T, Brossart DF, Luo W, Hicks JA, Warren AM, & Foreman M (in press). Trajectories of affective balance 1 year after traumatic injury: Associations with resilience, social support, and mild traumatic brain injury. Journal of Happiness Studies. DOI: 10.1007/s10902-018-0004-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert CE, Arbuckle SA, & Holden RR (2016). The Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability scale outperforms the BIDR impression management scale for identifying fakers. Journal of Research in Personality, 61, 80–86. DOI: 10.1016/j.jrp.2016.02.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Landis JR, & Koch GG (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 33, 159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange RT, Brickell TA, Kennedy JE, Bailie JM, Sills C,… French LM (2014). Factors influencing postconcussion and posttraumatic stress symptom reporting following military-related concurrent polytrauma and traumatic brain injury. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 29, 329–347. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acu013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losoi H, Silverberg ND, Waljas M, Turunen S, Rosti-Otajavi,…Iverson GL (2015). Resilience is associated with outcome from mild traumatic brain injury. Journal of Neurotrauma, 32, 942–949. doi: 10.1089/neu.2014.3799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer EC, La Bash H, DeBeer BB, Kimbrel NA, Gulliver SB, & Morissette SB (in press). Psychological inflexibility predicts PTSD symptom severity in war veterans after accounting for established PTSD risk factors and personality. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. doi: 10.1037/tra0000358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (1998–2013). Mplus user’s guide (7th edition). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Ong AD, Bergeman CS, & Boker SM (2009). Resilience comes of age: Defining features in later adulthood. Journal of Personality, 77(6), 1777–1804. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00600.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong AD, Zautra AJ, & Reid MC (2010). Psychological resilience predicts decreases in pain catastrophizing through positive emotions. Psychology and Aging, 25, 516–523. doi: 10.1037/a0019384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panayiotou A, Jackson M, & Crowe SF (2010). A meta-analytic review of the emotional symptoms associated mild traumatic brain injury. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 32, 463–473. doi: 10.1080/13803390903164371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, & Hayes AF (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohling ML, Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, & Axelrod BN (2017). Mild traumatic brain injury. In Bush SS (Editor in Chief), Handbook of forensic neuropsychology (pp. 147–200). Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Seal KH, Bertenthal D, Miner CR, Sen S, & Marmar C (2007). Bringing the war back home: Mental health disorders among 103,788 US veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan seen at Department of Veterans Affairs facilities. Archives of Internal Medicine, 167, 476–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadel WG (2010). Clinical assessment of personality: Perspectives from contemporary personality science. In Maddux JE & Tangney JP (Eds.), Social foundations of clinical psychology (pp. 329–348). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smith BW, Dalen J, Wiggins K, Tooley E, Christopher P, & Bernard J (2008). The Brief Resilience Scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 15, 194–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spira JL, Lathan CE, Bleiberg J, & Tsao J (2014). The impact of multiple concussions on emotional distress, post-concussive symptoms, and neurocognitive functioning in active duty United States marines independent of combat exposure or emotional distress. Journal of Neurotrauma, 31, 1823–1834. doi: 10.1089/neu.2014.3363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strahan R, & Gerbasi KC (1972). Short, homogenous version of the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability scale. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 28, 191–193. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan KA, Edmed SL, Allan AC, Smith SS, & Karlsson LJ (2015). The role of psychological resilience and mtbi as predictors of postconcussional syndrome symptomatology. Rehabilitation Psychology, 60, 147–154. doi: 10.1037/rep0000037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai J, Pietrzak RH, Hoff RA, & Harpaz-Rotem I (2016). Accuracy of screening for posttraumatic stress disorder in specialty mental health clinics in the U.S. Veterans Affairs Healthcare System. Psychiatry Research, 240, 157–162. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.04.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Üstün TB (2010). Measuring health and disability: Manual for WHO disability assessment schedule WHODAS 2.0 Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Üstün TB, Chatterji S, Kostanjsek N, Rehm J, Kennedy C, Epping-Jordan J…& Pull C in collaboration with WHO/NIH Joint Project. (2010). Developing the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 88, 815–823. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2013.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderploeg RD, Belanger H, Curtiss G, Bowles A, & Cooper D (2019). Reconceptualizing rehabilitation of individuals with chronic symptoms following mild traumatic brain injury. Rehabilitation Psychology, 64, 1–12. doi: 10.1037/rep0000255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt DS, Proctor SP, King DW, King LA, & Vasterling J (2008). Validation of scales from the Deployment Risk and Resilience Inventory in a sample of Operation Iraqi Freedom veterans. Assessment, 15, 391–402. doi: 10.1177/1073191108316030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh M, Armstrong T, Poritz J, Elliott TR, Jackson WT, & Ryan T (2016). Resilience, pain interference and upper-limb loss: Testing the mediating effects of positive emotion and activity restriction on distress. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 97, 781–787. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2016.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Litz BT, Herman DS, Huska JA, & Keane TM (1993). The PTSD Checklist: Reliability, validity, and diagnostic utility. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, San Antonio, TX. [Google Scholar]

- Whiting DL, Deane FP, Simpson GK, McLeod HJ, & Ciarrochi J (2017). Cognitive and psychological flexibility after a traumatic brain injury and the implications for treatment in acceptance-based therapies: A conceptual review. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 27, 263–299. doi: 10.1080/09602011.2015.1062115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windle G, Bennett KM, & Noyes J (2011). A methodological review of resilience measurement scales. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 9, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winer ES, Cervone D, Bryant J, McKinney C, Liu RT, & Nadorff MR (2016). Distinguishing mediational models and analyses in clinical psychology: Atemporal associations do not imply causation. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 72, 947–955. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu C (2002). Evaluating cutoff criteria of model fit indices for latent variable models with binary and continuous outcome. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation. University of California. [Google Scholar]

- Yu R, Branje S, Keijsers L, & Meeus W (2015). Associations between young adult romantic relationship quality and problem behaviors: An examination of personality-environment interactions. Journal of Personality, 57, 1–10. DOI 10.1016/j.jrp.2015.01.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]