Despite the accelerated and highly relevant growth of the implementation science (IS) field,38 critical lessons remain to be learned about the best implementation approaches to reduce persistent health and mental health disparities that impact diverse populations across the United States (US).9,29,30,35 For example, although Latinas/os have been essential to the growth of the US as a nation,2 low-income Latina/o immigrant populations remain largely excluded from primary systems of care.19,21,23,25

Most recently, the COVID-19 pandemic clearly demonstrated the profound economic inequities and health disparities experienced by disadvantaged Latinas/os. Specifically, low-income Latinos/as are among the ethnic groups most impacted by disproportionate COVID-19 infection rates.36 One of the main causes is the fact that poor Latina/o immigrants hold jobs that few US citizens are willing to perform but that remain of vital importance to the US economy (e.g., agriculture, food processing). Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, Latina/o immigrants remained an active labor force, despite the high risk for infection associated with their lines of work.4,5,7,8

As we reflect on these challenges, we consider that the IS field has fallen short of recognizing the critical importance that faith-based organizations have in the lives of underserved Latino/a immigrants and other populations of color, as well as the relevant role that churches can have in the implementation of health and mental health care prevention initiatives.27,29

Why do we place a strong emphasis on faith-based organizations? First, churches are frequently identified as trusted organizations by diverse populations exposed to intense contextual challenges. They also provide flexible infrastructures and reliable social support networks that are essential for the implementation of intervention and prevention initiatives.27,35 Further, lay church members trained as mental health providers can convey a unique sense of trust that is critical for implementing initiatives with populations exposed to historical adversity. Lay church members also tend to remain in their congregations for many years and constitute a steady presence, which addresses the issue of sustainment as interventions become part of church ministries.27,35 Finally, during times of crises such as the xenophobic persecutorial immigration activities promoted by the Trump administration against vulnerable immigrants, many churches remained strong advocates against abuses by immigration authorities. In contrast, the IS field mostly maintained a passive role during this humanitarian crisis.

It is our hope that the reflections in this manuscript can promote fruitful conversations in the IS field, highlighting the need to exponentially expand the voices of faith-based community leaders, as a counterbalance to those of researchers and academics who have been historically over-identified as the leading voices in the field. In the sections below, we first provide a brief overview of the intense adversity experienced by Latina/o immigrants in the US. We also present a case study that describes an alternative for promoting the wellbeing of Latina/o immigrant populations through the implementation of culturally adapted parenting prevention interventions. The presentation of the case study will have a main focus on describing two types of cultural adaptations that we consider account for the success of our initiatives: a) adaptation of evidence-based parenting interventions, and b) adaptation of implementation strategies.

Adversity Experienced by Low-Income Latina/o Immigrants

Low-income Latina/o immigrants have been essential to positioning the US as the dominant economic power in the world. However, the adversity experienced by this population remains largely unacknowledged. Specifically, poor Latina/o immigrants are likely to have jobs characterized by low salaries and strenuous working conditions. They are also commonly exposed to social isolation, language barriers, instances of discrimination, and multiple barriers to engage in formal health and mental health care services.28,19, 31,32

Further, it is well documented that the health of Latina/o immigrants is negatively impacted by the various forms of discrimination they experience.22,22 Latina/o children’ perceptions of discrimination experienced by their parents are also associated with increased risk for Latina/o youths’ internalizing problems such as depression and anxiety.28 Under the Trump administration, undocumented Latina/o immigrants were the target of forced and permanent family separations with extremely harmful and lasting impacts for children and youth.1

Flawed Frameworks and Strategies in the IS Field

We consider that most IS frameworks and strategies have been developed according to flawed assumptions of inclusion when referring to the most vulnerable immigrant populations in the US. For example, poor foreign-born Latina/o immigrant parents who lack documented status are ineligible to access basic systems of care, despite the critical contributions they offer to the US economy. This reality of invisibility has remained largely overlooked in implementation frameworks and strategies.

Further, most IS frameworks and strategies were not originally developed by including core constructs focused on examining dynamics of oppression, such as racial discrimination. As a result, the IS field remains one in which the voices that continue to be privileged are those of academics and researchers, while the voices of the individuals most affected by various forms of historical oppression remain minimized. In our view, the only way to move the IS field forward and to effectively address these issues is by elevating the voices of leaders of underserved communities of color. Because these individuals remain in the trenches with diverse populations exposed to continuous adversity, we consider that community leaders have a unique moral authority to speak for the ways in which implementation science can become a true social justice-informed science.

A Case Study of Collaboration and Shared Leadership: Implementing Parenting Prevention Programs in Faith-based Organizations

The adversity experienced by low-income Latina/o immigrant parents negatively impacts their parenting practices, with resulting negative effects on their children.15,23,34 However, evidence-based parenting interventions remain scarcely disseminated across US Latina/o immigrant communities.6 In addition, few evidence-based parenting interventions overtly address the impact of racism and other forms of discrimination experienced by low-income Latina/o immigrants.15, 17,18, 24 For this reason, we have engaged in efforts to culturally adapt parenting interventions for implementation in low-income Latina/o immigrant communities.

We focus on churches as our main implementation target because faith-based organizations are commonly trusted by the most vulnerable Latina/o immigrant populations. This was particularly important during the Trump administration when immigration authorities conducted arrests of immigrant parents in schools and other community settings. Throughout this humanitarian crisis, churches were perceived as consistent safe havens by vulnerable Latina/o immigrant parents.

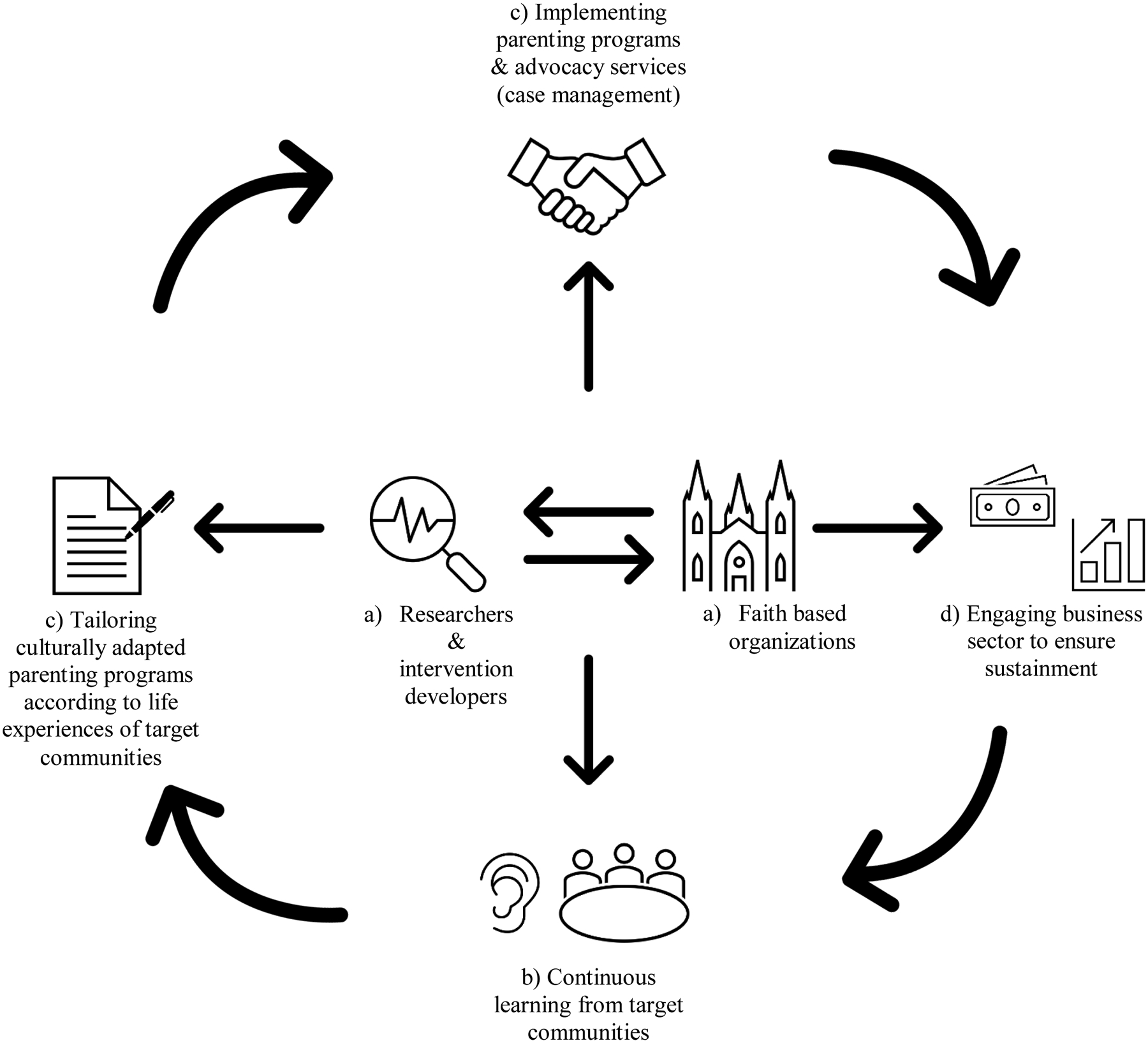

Currently, we have expanded our work to go beyond the adaptation of interventions. As illustrated in figure 1, the core of the proposed model consists of establishing a working alliance among intervention developers, cultural adaptation researchers, and church leaders. The figure also illustrates the inclusion of advocacy support for families, in addition to the delivery of prevention interventions. We consider that advocacy services are essential to support families as they cope with a variety of intense contextual stressors. Finally, we identify the business community as they have a crucial role for ensuring the long-term sustainment of interventions.

Figure 1.

Proposed Implementation Model

Culturally Adapting Evidence-based Parenting Interventions: Guiding the Process by Embracing Collaboration.

Culturally adapted interventions should be perceived as culturally and contextually relevant by target ethnic minority populations. However, what are the best ways to culturally adapt interventions? Scholars agree that a variety of methods are necessary. In our 15 years of experience adapting parenting interventions for Latina/o immigrant families, we have confirmed that three strategies are essential: a) learning the most relevant life and cultural experiences of target populations prior to conducting adaptations, b) adapting and tailoring interventions according to the most relevant contextual and cultural experiences of diverse families, and c) continuously tailoring adapted interventions to ensure high contextual and cultural relevance.

Learning from the life and cultural experiences of target diverse populations.

Resembling the approach we followed for the cultural adaptation of parenting programs for Latina/o immigrant communities in Michigan,14 we recently established a collaboration with a major faith-based organization in mid-Texas. As a foundational step, we corroborated with church leaders that the proposed adapted parenting intervention was of relevance to the needs expressed by community members. Next, we implemented a qualitative study with 30 parents to learn about their experiences as immigrants and parenting needs. We then proceeded to culturally tailor the adapted parenting intervention according to their life experiences.

As expected, Latino/a parents who participated in the qualitative study expressed a strong interest to attend church-based parenting programs as churches are consider safe places by them. The sense of urgency to receive support was continuously highlighted by parents, as one father said, “we all feel pressured about parenting. There are many parents with adolescents in this community and they do not know where to go for help…We just need a lot of help.”39

Caregivers also reported that parenting programs should be informed by a clear understanding of experiences of discrimination that negatively affect their lives and parenting practices. One of the many examples of racial discrimination reported in the interviews was described by one mother:

We attended a rally on immigration and a man walked towards us and told me, “You do not know what you are doing. President Trump is right about immigration. It is about cleaning the whole country, the whole United States.” My daughter told him, “I am a US citizen and I am also Mexican!”…And he said back to us, “Yes, and that is why we need to clean the whole United States!”39

With regards to work exploitation, parents provided several painful testimonies, such as this one:

Our boss would take advantage of us because she knew we had a lot of need and if the other workers did not like the job, they would just leave. But we were always there and they would never give us protection. One day, I cut my forehead very badly with a glass they left exposed, but she did not do anything for me. I had to go to the emergency room on my own and I had to pay for all my medical expenses.39

Adapting Interventions.

The focus of our adaptation work for the past 10 years has been the evidence-based parenting intervention known as Parent Management Training Oregon (GenerationPMTO©). The positive impacts of GenerationPMTO have been thoroughly demonstrated in several studies over the course of 40 years.3 The first cultural adaptation of GenerationPMTO for Latina/o immigrant populations was achieved by following a rigorous model of cultural adaptation and was titled “CAPAS: Criando con Amor, Promoviendo Armonía y Superación” (Raising Children with Love, Promoting Harmony and Self-Improvement).10

In a prevention study with Latina/o immigrant families in Michigan with children ages 4–12, we demonstrated the importance of overtly addressing immigration-related challenges and biculturalism in the CAPAS intervention. Specifically, we compared a version of the CAPAS intervention exclusively focused on parent training components, in contrast to a CAPAS-Enhanced intervention in which parenting components were complemented by sessions focused on immigration-related challenges, discrimination, and biculturalism. According to study results, the CAPAS-Enhanced intervention was associated with the highest improvements on child mental health outcomes such as reduced youth anxiety and behavioral problems.12 Parents expressed that the CAPAS-Enhanced intervention was useful because they became aware of the ways in which immigration-related stressors such as discrimination, negatively impacted their parenting practices.13–14 Most recently, we completed a study with a version of CAPAS for immigrant families with youth, resulting in similar intervention impacts.13

Continuous Tailoring of Adapted Interventions.

In addition to quantitative indicators of intervention impact, personal testimonies of parents are essential to confirm their satisfaction with culturally adapted parenting programs. For example, caregivers consistently report in our studies the positive impact of practices leading to improving the positive involvement with their children, as well as implementing discipline in non-punitive ways. As one mother affirmed, “the discipline we learned here works really well. Discipline by being firm but without fighting with them, offending them, disrespecting them. Now they are learning rules but also respect.”13

Similarly, parents consistently reflect about the importance of learning new ways of interacting with their children, as one father affirmed, “I always asked my children stuff by yelling at them… Practicing how to give good directions helped me a lot…I was the problem because I was always angry…We are basically learning how to be good parents.”13

Cultural Adaptation of Implementation Strategies

Co-leadership Grounded in Members of the Community.

In addition to adapting interventions, it is essential to implement culturally relevant strategies aimed at building trust, co-leadership, and active participation of community members. In our current collaboration, San José Catholic church is the community leader of this initiative.

San José Catholic Church is the largest faith-based organization serving the Latina/o immigrant population in our target community. The Church is integrated by several ministries serving the needs of Latina/o immigrant families. In this project, we closely work with the San José Social Justice Ministry, which is led by lay leaders engaged in initiatives focused on promoting the rights of Latina/o immigrants. For example, Ofelia Zapata, a co-leader of the initiative, serves on the Board of Trustees of the local school district where most low-income Latina/o families reside.

The social justice ministry implements initiatives of high relevance for the local immigrant community. For example, the ministry will collaborate with key government agencies, including law enforcement, to generate personal church IDs for undocumented immigrants. The objective is for immigrants to permanently carry IDs that can be presented to law enforcement officials and demonstrate their affiliation with a highly recognized faith-based organization, in an effort to prevent biased police profiling.

The ministry also sponsors immigration legal aid programs focused on offering free-of-charge legal counsel to prepare mixed-immigrant status families for potential situations of forced family separation by immigration authorities. To offer a clear picture of this work, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the ministry congregated families to help them engage with immigration attorneys and discuss actions plans in case parents were deported by immigration authorities (e.g., transferring parental rights to relatives who are US citizens). These meetings would be followed by participation in our focus groups, in which parents reflected about their parenting experiences and needs. To this day, our research team talks about the extraordinary resilience that we have witnessed in these families as they cope in with intense adversity in their lives.

Why is San José’s leadership essential to this parenting prevention initiative? San José’s social justice ministry and its head priest, Father Jairo Sandoval-Pliego, have always demonstrated resolved support towards this initiative. Father Jairo has been an extraordinary advocate for this prevention initiative, including obtaining all necessary authorizations that were required from San José’s Pastoral Council. In addition, the social justice ministry has been essential to help us recruit ministry leaders who are already actively involved in the implementation of the parenting program. Further, as we will engage in the large-scale dissemination of the intervention, the ministry will support these efforts by relying on their extensive network of collaborations with churches committed to serving Latina/o immigrant populations in mid-Texas.

Parents as Interventionists.

In the initiatives we have implemented, an average of 83% of participating families have completed the parenting programs.13 A key factor associated with this success refers to the fact that parenting groups are co-delivered by a master’s level clinician and a parent from the target community. This composition of the intervention delivery team is highly relevant. First, trained clinicians can identify and manage delicate clinical situations that often arise in parenting groups. With regards to parents, they provide a sense of safety and trust that only community members can communicate. Thus, whenever contextual challenges are shared by participant parents, parent educators transmit empathy in a way that only members of target communities can.

Beyond Offering Interventions: Advocacy as a Human Rights Implementation Strategy

A key implementation strategy leading to the success of our programs refers to supporting immigrant families beyond their exposure to prevention interventions. This is a matter of social justice, particularly because there is a high risk for researchers and academics to remain fixated in “research outcomes.” Thus, we pair each participating family with an advocate whose role is to help families find resources to help them cope with a variety of contextual stressors (e.g., low-cost immigration legal services, food assistance programs, access to health care).

In our current project, this work is led the Migrant Clinicians Network (MCN). The MCN’s organizational mission is to reduce health disparities for people who need care but who are unable to access it due to the contextual challenges they experience. Based on their mission and expertise in assisting families exposed to intense diversity, the MCN constitutes an ideal co-leader in this project.

Establishing Sustainment Since the Beginning.

Planning the long-term sustainment of interventions constitutes a key strategy that should be implemented at the outset of community-based initiatives.29 In our current work, we are engaged in the process of identifying business leaders committed to social innovation, which is an emerging trend in the business world that expects from entrepreneurs to become agents of social change in underserved communities.37 We consider this strategy as essential, particularly because it is critical to provide innovative models capable of sustaining community-based prevention initiatives beyond temporary funding cycles.

Bringing All the Pieces Together

In closing, we consider unacceptable that despite poor Latina/o immigrants having a crucial role in positioning and maintaining the US as the strongest economy in the world, their basic needs and human rights continue to be largely unaddressed. We see this as a phenomenon grounded in historical xenophobia, racism, and dehumanized capitalism. Thus, it is essential to promote conversations in the IS field, aimed at finding alternatives to support the lives of underserved immigrant populations in the US. As the field moves forward, it is essential to thoroughly recognize the extraordinary leadership of faith-based organizations committed to serving vulnerable immigrant communities. These organizations, their leaders, and the families they serve; should always be recognized as the primary agents of change as diverse communities continue their efforts to bring down legacies of adversity and oppression.

Contributor Information

Rubén Parra-Cardona, Steve Hicks School of Social Work, The University of Texas at Austin.

Deliana García, Migrant Clinicians Network.

References

- 1.Capps R, Koball H, Campetella A, Perreira K, Hooker S, & Pedroza JM (2015). Implications of Immigration Enforcement Activities for the Well-Being of Children in Immigrant Families: A Review of the Literature. Retrieved from the Migration Policy Institute website: http://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/implications-immigration-enforcement-activities-well-being-children

- 2.United States Census Bureau. (2018). USA Quick Facts. Retrieved August 7, 2018, from http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/00000.html

- 3.Forgatch MS, Patterson GR, DeGarmo DS, & Beldavs ZG (2009). Testing the Oregon delinquency model with 9-year follow-up of the Oregon divorce study. Development and Psychopathology, 21, 637–660. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perrino T, Pantin H, Prado G, Huang S, Brincks A, Howe G,…Brown CH (2014). Preventing internalizing symptoms among Hispanic adolescents: A synthesis across Familias Unidas trials. Prevention Science, 15, 917–928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stein GL, & Guzman LE (2015). Prevention and intervention research with Latino families: A translational approach. Family Process, 54, 280–292. 10.1111/famp.12143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Michelson D, Davenport C, Dretzke J, Barlow J, & Day C (2013). Do evidence-based interventions work when tested in the “real world?” A systematic review and meta-analysis of parent management training for the treatment of child disruptive behavior. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 16, 18–34. 10.1007/s10567-013-0128-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Estrada Y, Lee TK, Huang S, Tapia MI, Velazquez M-R, Martinez MJ, … Prado G (2017). Parent-centered prevention of risky behaviors among Hispanic youths in Florida. American Journal of Public Health, 107, 607–613. 10.2105/ajph.2017.303653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prado G, Estrada Y, Rojas LM, Bahamon M, Pantin H, Nagarsheth M, Gwyn L, Ofir AY, Forster LQ, Torres N, Brown CH (2019). Rationale and design for eHealth Familias Unidas Primary Care: A drug use, sexual risk behavior, and STI preventive intervention for Hispanic youth in pediatric primary care clinics. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 76, 64–71. Doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2018.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, HHS. (2015). HHS Action Plan to Reduce Racial and Ethnic Disparities: Implementation Progress Report 2011–2014. US Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved from HHS website: http://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/assets/pdf/FINAL_HHS_Action_Plan_Progress_Report_11_2_2015.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 10.Domenech Rodríguez MM, Baumann AA, & Schwartz AL (2011). Cultural adaptation of an evidence-based intervention: From theory to practice in Hispanic/a community context. American Journal of Community Psychology, 47, 170–186. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9371-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parker MA, & Anthony JC (2018). Population-level predictions from cannabis risk perceptions to active cannabis use prevalence in the United States, 1991–2014. Addictive Behaviors, 82, 101–104. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parra-Cardona JR, Bybee D, Sullivan CM, Domenech Rodríguez MM, Dates B, Tams L, & Bernal G (2017). Examining the impact of differential cultural adaptation with Latina/o immigrants exposed to adapted parent training interventions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 85, 58–71. doi.org/ 10.1037/ccp0000160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parra-Cardona JR, López-Zerón G, Leija SG, Maas MK, Villa M, Zamudio E, Arredondo M, Yeh HH, & Domenech Rodríguez MM (2018). A Culturally Adapted Intervention for Mexican-origin Parents of Adolescents: The Need to Overtly Address Culture and Discrimination in Evidence-Based Practice. Family Process. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1111/famp.12381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parra-Cardona JR, Holtrop K, Córdova D, Escobar-Chew AR, Tams L, Horsford S, Villarruel FA, Villalobos G, Dates B, Anthony JC, & Fitzgerald HE (2009). “Queremos Aprender”: Latino immigrants call to integrate cultural adaptation with best practice knowledge in a parenting intervention. Family Process, 48, 211–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gonzales NA, German M, Kim SY, George P, Fabrett FC, Millsap R, & Dumka LE (2008). Mexican American adolescents’ cultural orientation, externalizing behavior and academic engagement: The role of traditional cultural values. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41, 151–164. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9152-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smokowski PR, Buchanan RL, & Bacallao ML (2009). Acculturation and adjustment in Hispanic adolescents: How cultural risk factors and assets influence multiple domains of adolescent mental health. Journal of Primary Prevention, 30, 371–393. doi: 10.1007s/10935-009-0179-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park IJK, Wang L, Williams DR, & Alegria M (2017). Does anger regulation mediate the discrimination-mental health link among Mexican-origin adolescents? A longitudinal mediation analysis using multilevel modeling. Developmental Psychology, 53, 340–352. 10.1037/dev0000235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Unger JB (2015). Preventing substance use and misuse among racial and ethnic minority adolescents: Why are we not addressing discrimination in prevention programs? Substance Use & Misuse, 50, 952–955. 10.3109/10826084.2015.1010903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cardoso JB, Scott JL, Faulkner M, & Lane LB (2018). Parenting in the context of deportation. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 80, 301–316. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12463 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Updegraff KA, & Umaña-Taylor AJ (2015). What can we learn from the study of Mexican-origin families in the United States? Family Process, 54, 205–216. doi: 10.1111/famp.12135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Psychological Association (2017). Mental Health Disparities: Hispanics and Latinos. Retrieved on July 5th, 2018, from http:///C:/Users/jrpcp/AppData/Local/Packages/Microsoft.MicrosoftEdge_8wekyb3d8bbwe/TempState/Downloads/Mental-Health-Facts-for-Hispanic-Latino%20(1).pdf

- 22.Paret M (2014). Legality and exploitation: Immigration enforcement and the US migrant labor system. Latino Studies, 12, 503–526. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park IJK, Du H, Wang L, Williams DR, & Alegria M (2018). Racial/ethnic discrimination and mental health in Mexican-origin youths and their parents: Testing the “linked lives” hypothesis. Journal of Adolescent Health, 62, 480–487. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaminski JW, Valle LA, Filene JH, & Boyle CL (2008). A Meta‐analytic review of components associated with parent training program effectiveness. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36, 567–589. 10.1007/s10802-007-9201-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Castle B, Wendel M, Kerr J, Brooms D, & Rollins A (2018). Public health’s approach to systemic racism: A systematic literature review. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Disparities. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bach-Mortensen AM, Lange BC, & Montgomery P (2018). Barriers and facilitators to implementing evidence-based interventions among third sector organizations: a systematic review. Implementation Science, 13:103. 10.1186/s13012-018-0789-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Allen JD, Torres MI, Tom LS, Leyva B, Galeas AV, Ospino H (2016). Dissemination of evidence-based cancer control interventions among Catholic faith-based organizations: results from the CRUZA randomized trial. Implementation Science, 11:74, 1–11. doi: 10.1186/s13012-016-0430-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Espinoza G, Gonzalez NA, & Fuligni AJ (2016). Parent discrimination predicts Mexican-American adolescent psychological adjustment 1 year later. Child Development, 87, 1079–1089. Doi: 10.1111/cdev.12521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palinkas LA, Spear SE, Mendon SJ, Villamar J, Valente T, Chou CP…Brown CH (2016). Measuring sustainment of prevention programs and initiatives: a study protocol. Implementation Science, 11:95. doi: 10.1186/s13012-0160467-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cabassa LJ, & Stefancic A (2018). Context before implementation: a qualitative study of decision makers’ views of a peer-led healthy lifestyle intervention for people with serious mental illness in supportive housing. Translational Behavioral Medicine, April: 1–10. doi: 10.1093/tbm/iby034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Whitney DG, & Peterson MD (2019). US National and State-Level prevalence of mental health disorders and disparities of mental health care use in children. JAMA Pediatrics, February. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Community Advancement Network (2018). Key socioeconomic indicators for greater Austin and Travis County. Retrieved online on 3/3/2019 from Community Advancement Network website: http://canatx.org/dashboard/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/2017-CAN-Dashboard-FINAL-FOR-WEB-9.21.17.pdf

- 33.World Health Organization (2013). World Health Organization Mental Health Action Plan. Geneva: WHO Press. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Niec LN, Acevedo-Polakovich ID, Abbenante-Honold E, Christian AS, Barnett ML, Aguilar G, & Peer SO (2014). Working together to solve disparities: Latina/o parents’ contributions to the adaptation of a preventive intervention for childhood conduct problems. Psychological Services, 11, 410–420. doi: 10.1037/a0036200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stewart JM (2014). Implementation of evidence-based HIV interventions for young adult African American women in church settings. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing, 43, 655–663. doi: 10.1111/1552-6909.12494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yudell M, Roberts D, DeSalle R, & TishKoff S (2020). NIH must confront the use of race in science, Science, 369, 1313–1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stanford Graduate School of Business (2020). Defining Social Innovation. Downloaded from Stanford University website on November 4th, 2020: https://www.gsb.stanford.edu/faculty-research/centers-initiatives/csi/defining-social-innovation

- 38.Colditz GA, & Emmons KM (2020). The promise and challenges of dissemination and implementation research. In Brownson RC, Colditz GA, & Proctor EK (Eds.)., Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health, pp. 1–18. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parra-Cardona JR, Londono T,* Davila S,* Gonzalez Villanueva E,* Fuentes J,* Fondren C,* Zapata O, Emerson M, & Claborn K (2020). Parenting in the Midst of Adversity: Tailoring a Culturally Adapted Parent Training Intervention According to the life experiences of Mexican-Origin Caregivers. Family Process. doi: 10.1111/famp.12555. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]