Abstract

Small-molecule modulators of calcineurin signaling have been proposed as potential therapeutics in Down syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease. Models predict that in Down syndrome, suppressed calcineurin-NFAT signaling may be mitigated by proINDY, which activates NFAT, the nuclear factor of activated T-cells. Conversely, elevated calcineurin signaling in Alzheimer’s disease may be suppressed with the calcineurin inhibitors cyclosporine and tacrolimus. Such small-molecule treatments may have both beneficial and adverse effects. The current study examines the effects of proINDY, cyclosporine and tacrolimus on behavior, using zebrafish larvae as a model system. To suppress calcineurin signaling, larvae were treated with cyclosporine and tacrolimus. We found that these calcineurin inhibitors induced hyperactivity, suppressed visually-guided behaviors, acoustic hyperexcitability and reduced habituation to acoustic stimuli. To activate calcineurin-NFAT signaling, larvae were treated with proINDY. ProINDY treatment reduced activity and stimulated visually-guided behaviors, opposite to the behavioral changes induced by calcineurin inhibitors. The opposing effects suggest that activity and visually-guided behaviors are regulated by the calcineurin-NFAT signaling pathway. A central role of calcineurin-NFAT signaling is further supported by co-treatments of calcineurin inhibitors and proINDY, which had therapeutic effects on activity and visually-guided behaviors. However, these co-treatments adversely increased excitability, suggesting that some behaviors are regulated by other calcineurin signaling pathways. Overall, the developed methodologies provide an efficient high-throughput platform for the evaluation of modulators of calcineurin signaling that restore neural function, while avoiding adverse side effects, in a complex neural system.

Keywords: Zebrafish, behavior, Calcineurin signaling, Down syndrome, Alzheimer’s disease

Graphical abstract

Introduction

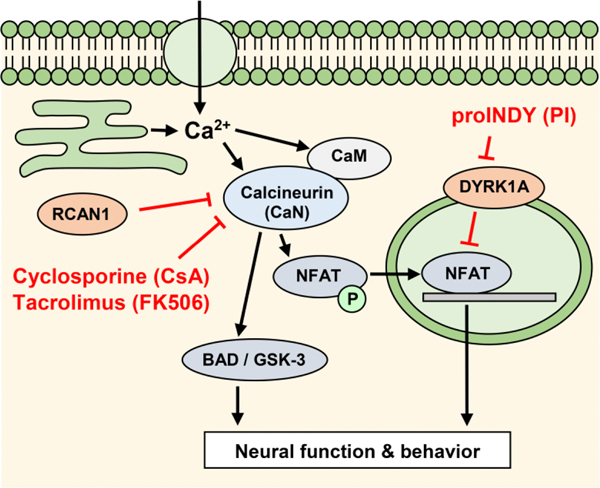

Calcineurin is a calcium-dependent serine-threonine phosphatase with a well-described signaling pathway (Fig 1) and broad clinical significance [1–3]. Calcineurin inhibitors are used as immunosuppressants to prevent rejection of organ transplants [1]. Additionally, modulated calcineurin signaling is associated with neural dysfunction in Down syndrome, Alzheimer’s disease, schizophrenia, epilepsy, neuro inflammation, and traumatic brain injury [3]. In Down syndrome (trisomy 21), the extra copy of chromosome 21 leads to a suppression of calcineurin signaling [4]. In contrast, various studies have shown that calcineurin signaling is elevated in Alzheimer’s disease and suggest that the inhibition of calcineurin may serve as a viable therapeutic strategy for treating early stage Alzheimer’s disease [5–8]. This concept is supported by a study showing that Alzheimer’s disease rarely develops in transplant patients treated with the calcineurin inhibitors cyclosporine (CsA) or tacrolimus (FK506), in all age groups above 65 [9]. While some neural degeneration may be beyond repair, modulators of calcineurin signaling have the potential to prevent progressive neural degeneration in various disorders.

Figure 1.

Model of calcineurin signaling. Intracellular free calcium activates calcineurin, which dephosphorylates various target proteins, including the nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT), BCL2-associated death protein (BAD) and glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3). Calcineurin can be inhibited by the ‘Regulator of Calcineurin’, RCAN1 (previously called the ‘Down syndrome critical region’, DSCR1), or by small molecules such as cyclosporine (CsA) and tacrolimus (FK506). DYRK1A inhibits the calcineurin-NFAT pathway by phosphorylating NFAT. The small molecule INDY inhibits the inhibitor DYRK, which leads to increased NFAT signaling. ProINDY can be used as a cell-permeable prodrug to deliver INDY inside a cell. Note: NFAT, DYRK and RCAN in mammals are named nfat, dyrk, rcan (genes) or Nfat, Dyrk, Rcan (proteins) in zebrafish.

Little is known about the risks and potential benefits of treatments that aim to restore calcineurin signaling pathways in the brain. Clinical or population studies are limited to a few potential treatments [9]. Animal model systems are available, but subtle morphological changes in specific neurons are easily missed when studying an organ as complex as the brain. The analysis of behavior offers a potential solution, since subtle changes in neural structure and function can be detected.

Zebrafish are well suited for large-scale analyses of behavior [10–13]. Zebrafish have a prototype vertebrate brain with conserved calcineurin signaling pathways and Alzheimer’s-related proteins such as the amyloid precursor protein and the microtubule-associated protein tau [14]. At 5 days post-fertilization, the developing zebrafish larvae have inflated swim bladders, hunt for food and display avoidance behaviors [15]. The larvae are only 4 mm long at this time and are well suited for automated analyses of behavior in 96-well plates [10].

Using the zebrafish model, the present study shows that modulators of calcineurin signaling have therapeutic effects on activity and visually-guided behaviors, but adversely affect acoustic excitability. The developed methodologies provide an efficient platform for the evaluation of modulators of calcineurin signaling that restore neural function, while avoiding adverse side effects, in developmental and neurodegenerative disorders.

Materials and Methods

Zebrafish

The research project has been conducted in accordance with local and federal guidelines for ethical and humane use of animals and has been reviewed and approved by the Brown University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryos were collected and grown to larval stages as previously described [10, 16]. Adult wild-type zebrafish are maintained at Brown University as a genetically-diverse outbred strain in a mixed male and female population. Zebrafish embryos from 0–3 days post-fertilization (dpf) and zebrafish larvae from 3–5 dpf were maintained at 28.5°C in 2L culture trays with egg water, containing 60 mg/L sea salt (Instant Ocean) and 0.25 mg/L methylene blue in deionized water. Embryos and larvae were kept on a 12 hour light/12 hour dark cycle and were randomly assigned to different experimental groups prior to experimental manipulation. The sex of embryos and larvae cannot be determined at such early stages because zebrafish use elusive polygenic factors for sex determination, and both males and females have juvenile ovaries between 2.5 and 4 weeks of development [17]. Zebrafish larvae were imaged at 5 dpf when the larvae display a range of locomotor behaviors and consume nutrients available in the yolk sac [18]. Larvae are approximately 4 mm long at the 5 dpf stage.

Pharmacological treatments

Cyclosporine (cyclosporin A, Enzo Life Sciences), FK506 (tacrolimus, Enzo Life Sciences), rapamycin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and proINDY (Tocris Bioscience) were diluted in egg water from 1000x stocks dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). DMSO (1 μl/ml DMSO) was added to the single treatments and the corresponding DMSO concentration (2 μl/ml) was used as a vehicle control. Larvae were exposed at 5 dpf to treatment solutions or DMSO for a total of 6 hours. Larvae were first treated in a Petri dish for 2 hours, transferred with the treatment solution to white 96-well ProxiPlates (PerkinElmer, 6006290) for 1 hour, and then imaged in the treatment solution for 3 hours. Immediately after exposure, larvae from each treatment group were washed in egg water and transferred to Petri dishes with 50 mL egg water. Larvae that were imaged again at 6 and 7 dpf were given food twice prior to each re-imaging session.

Imaging system

Zebrafish larvae were imaged in an imaging system that holds four 96-well plates for automated analysis of behavior in a 384-well format as previously described [10]. Briefly, the imaging system is housed in a 28.5ºC temperature-controlled cabinet where larvae in white 96-well ProxiPlates are placed onto a glass stage. Above the stage, a high-resolution camera (18-megapixel Canon EOS Rebel T6 with an EF-S 55–250 mm f/4.0–5.6 IS zoom lens) captures an image of the larvae in the four 96-well plates every 6 seconds. The camera is connected to a continuous power supply (Canon ACK-E10 AC Adapter) and controlled by a laptop computer using Canon’s Remote Capture software (EOS Utility, version 3), which is included with the camera. Unlike previous descriptions of this imaging system, two small speakers (OfficeTec USB Computer Speakers Compact 2.0 System) were attached speaker-side down to the glass stage. Speakers were connected by USB to the laptop computer and set to maximum volume, reaching 85 dBA on the stage. Below the glass stage, a M5 LED pico projector (Aaxa Technologies) with a 900 lumens LED light source displays Microsoft PowerPoint presentations through the opaque bottom of the 96-well plates.

Behavioral assay

Visual and acoustic stimuli are controlled by an automated 3-hour PowerPoint presentation that is shown to the larvae. The entire 3-hour presentation has a light gray background and starts with a 1-hour period without visual or acoustic stimuli, followed by 80 minutes of visual stimuli, a 10-minute period without visual or acoustic stimuli, and 30 minutes with acoustic stimuli. Larvae were not exposed to visual stimuli and acoustic stimuli at the same time.

The visual stimuli consisted of a series of moving lines that were red, green or blue. Prior studies have shown that zebrafish larvae will swim in the same direction as moving lines, a behavior that is called an optomotor response or OMR [16, 19]. Our previously-developed assays for visually-guided behaviors indicate 5 dpf larvae consistently respond to 1 mm thick lines set 7 mm apart that move 7 mm per 8 seconds downwards or upwards, alternating direction in 10-minute periods [10]. Additionally, the presentation included red lines that moved at a faster speed of 7 mm per 0.5 seconds (16x faster). We used the following sequence of moving visual stimuli in subsequent 10-minute periods: downward red lines, upward red lines, downward green lines, upward green lines, downward blue lines, upward blue lines, downward fast red lines, upward fast red lines. The brightness of the background (RGB = 210, 210, 210), red lines (RGB = 255, 0, 0), green lines (RGB = 0, 180, 0), and blue lines (RGB = 0, 0, 230) in the PowerPoint presentation are carefully matched to the camera settings (ISO200, Fluorescent, F5, 1/5 exposure) for optimal color separation in the automated image analysis.

The acoustic stimuli consisted of brief sine waves or ‘pulses’ (100 ms, 400Hz) created in Audacity as 20-second sound tracks and inserted in the PowerPoint presentation. Larvae were first exposed for 10 minutes to repeated acoustic pulses with a 20-second interval, followed by 10 minutes of repeated acoustic pulses with a 1-second interval, and 10 minutes of repeated acoustic pulses with a 20-second interval. The PowerPoint presentation with the visual and acoustic stimuli is included in the Supplementary Information.

Image analysis

We previously created an ImageJ macro for automated analysis of behavior in a 384-well format [10]. This macro has since been optimized for the analysis of brighter images (version 26rc062019). The ImageJ macro can analyze up to four 96-well plates, with multiple treatment groups and visual stimuli that change direction, color, and speed. Users are prompted to enter information about the plates and the periods with different visual stimuli. The software opens the first image, splits the color channels, and selects a channel in which the visual stimuli and background have similar intensities. Subsequent images are subtracted from each other to remove the background and highlight larvae that move. The software then applies a threshold (40–255), selects the first well, measures the area and centroid of the larva and logs the measurements in a ‘Results’ file. This process is automatically repeated for all wells in an image and all subsequent images in a series. The frequency of larval movement and the relative position of larva in each well is analyzed and included in the Results file. The Results file is then imported into a Microsoft Excel template (version 26rc040320 - for 96-well plates). This template averages values for activity and vision in all experimental groups and imaging periods and displays the results in a graph. Alternatively, the template averages values for activity in each experimental group per image. The ImageJ macro and MS Excel templates are available in the Supplementary Information. The original results files and/or images will be made available upon request.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed in MS Excel as described previously [10]. Briefly, measurements of larval movement and position were averaged in each well during 10-minute periods. The 10-minute values were then averaged between larvae in the same treatment group. Differences between experimental groups and the corresponding controls were tested for significance. We used the non-parametric Chi-square test, since larval behaviors do not follow a normal distribution [10]. Differences in behavior were considered significant when p < 0.05, p < 0.01 or p<0.001 with a Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons (p < 0.05/14, p<0.01/14 or p < 0.001/14). The following 14 comparisons were made: single treatments vs. DMSO (5 comparisons); rapamycin (Rap) vs. FK506 to examine target specificity (1 comparison); CsA+PI vs. CsA to examine if 5 or 10 μM proINDY (PI) rescues the effect of CsA (2 comparisons); CsA+PI vs. PI to examine if CsA rescues the effect of 5 or 10 μM proINDY (2 comparisons); FK506+PI vs. FK506 to examine if 5 or 10 μM proINDY rescues the effect of FK506 (2 comparisons); and FK506+PI vs. PI to examine if FK506 rescues the effect of 5 or 10 μM proINDY (2 comparisons). The conservative Bonferroni correction helps to avoid type I errors (false positives), which is important in the analysis of large data sets. Internal vehicle controls were included in each imaging session.

Cluster analysis of behavioral profiles

Changes in larval activity, vision, startle response, habituation and excitability as compared to the DMSO vehicle controls were summarized in a ‘behavioral profile’. These behavioral profiles were generated for each compound used in this study. Similar profiles were grouped by hierarchical cluster analysis. The cluster analysis was carried out in Cluster 3.0 without filtering or adjusting data and using the Euclidian distance similarity metric with complete linkage. The clusters were shown in TreeView (version 1.1.6r4) using a spectrum from green (25% decrease) to red (25% increase).

Results

Measurements of behavior in zebrafish larvae

Zebrafish larvae were examined at 5 days post-fertilization (dpf) using an imaging system with four 96-well plates for automated analysis of behavior in a 384-well format (Fig 2). The high-resolution imaging system is capable of measuring movement and location of individual larvae in each well. At 5 dpf, zebrafish larvae are approximately 4 mm long, swim freely and respond to visual and acoustic stimuli. The visual stimuli in this study consisted of moving lines (red, green or blue), projected through the bottom of opaque 96-well plates. Zebrafish larvae swim in the same direction as moving lines through their innate optomotor response or OMR [16, 19]. The acoustic stimuli consisted of sound pulses at 20-second intervals or 1-second intervals. Larvae are known to display repeated startle responses to infrequent acoustic pulses at 20-second intervals, but habituate to frequent pulses at 1-second intervals [20, 21].

Figure 2.

Imaging of zebrafish larval behavior. Five-day-old larvae were imaged for 3 hours in a 384-well format (four 96-well plates). Left: overview of four plates. Right: individual well with a zebrafish larva located ‘down’ in the lower half of the well (plate 4, well D5). Moving lines (red, green or blue) were projected through the bottom of the 96-well plates for measurements of the optomotor response (OMR). Larval activity and location were measured by automated image analysis to prevent observer bias and fatigue. Inner well diameter = 7.15 mm.

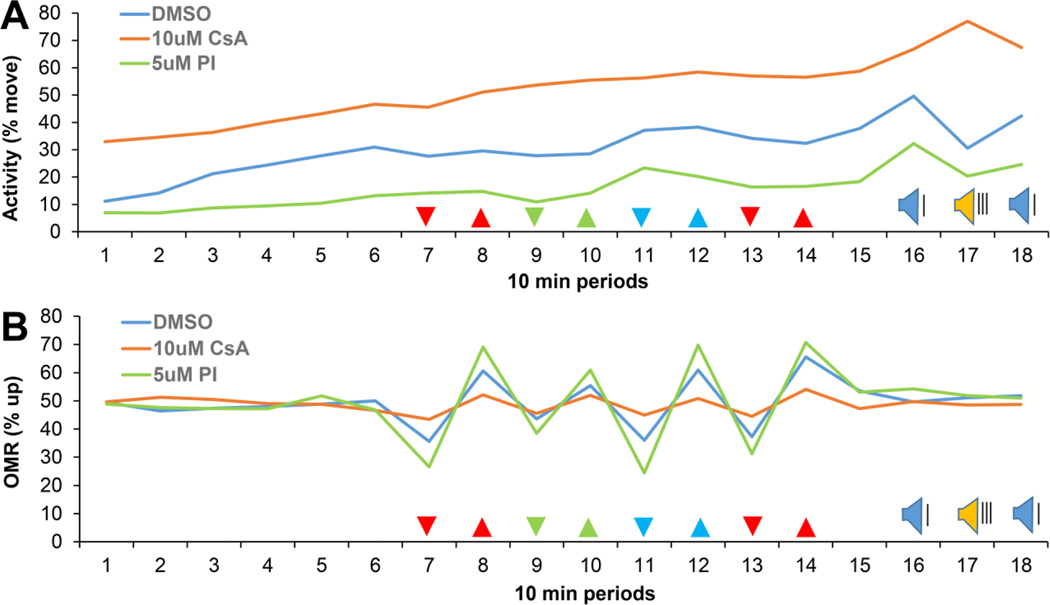

Zebrafish larvae were treated at 5 dpf with various modulators of calcineurin signaling, starting 3 hours before imaging. The larvae were then imaged for a total of 3 hours using a behavioral assay with various visual and acoustic stimuli (Fig 3). The behavioral assay started with a 1-hour period without stimuli, followed by 80 minutes with visual stimuli, 10 minutes without visual or acoustic stimuli, and 30 minutes with acoustic stimuli. Values of activity (% move) and position (% up) were averaged in individual larvae during 10-minute periods, for a total of 18 periods. These values were subsequently averaged between larvae in the same treatment group. We examined a total of 10 treatment groups. For clarity, only 3 treatment groups were graphed (Fig 3), but all 10 treatment groups were analyzed in detail as shown in subsequent figures. The 18-period graphs show that multiple calcineurin-sensitive behaviors can be examined in a single assay. The assay provides quantitative information on activity, visually-guided behaviors and acoustic startle responses.

Figure 3.

Measurements of zebrafish larval behavior. A) Activity in subsequent 10 minute periods (18 periods, 3 hours total). Cyclosporine (CsA) induced an increase in activity and proINDY (PI) induced a decrease in activity. B) The optomotor response (OMR); zebrafish larvae swim in the same direction as moving lines projected through the bottom of a 96-well plate. Cyclosporine induced a decrease in the optomotor response and proINDY induced an increase in the optomotor response. % move = the percentage of time that larvae move. % up = the percentage of time that a larvae are located in the upper half of a well. The arrowheads indicate the color and direction of the visual stimuli. For example, red lines move down in period 7 and move up in period 8. The red lines in period 13 and 14 move 16x faster than the red, green and blue lines in period 7–12. Blue speaker = acoustic stimuli with a 20-second interval. Yellow speaker = acoustic stimuli with a 1-second interval. Statistical analyses of activity and vision are shown in subsequent figures. N = 912, 372 and 383 larvae in the DMSO vehicle control, cyclosporine and proINDY group, respectively.

Pharmacological treatments

To determine if larval zebrafish behavior is affected by modulation of calcineurin signaling, we imaged 5 day-old larvae in the following 10 treatment groups: 10 μM cyclosporine A (CsA), 1 μM tacrolimus (FK506), 5 or 10 μM proINDY, a combination of CsA + 5 or 10 μM proINDY, or a combination of FK506 + 5 or 10 μM proINDY, DMSO as a vehicle control, and 1 μM rapamycin as a control for target specificity. Rapamycin and FK506 are both macrolide immunosuppressants with similar structures, however, rapamycin affects Target of Rapamycin (TOR) signaling instead of calcineurin signaling [22]. The concentrations of CsA, FK506 and rapamycin were selected based on prior studies in zebrafish embryos and larvae [23, 24]. The two concentrations of proINDY, a membrane-permeable form of INDY (inhibitor of DYRK), were selected based on studies in cell lines and Xenopus embryos [25]. We found that none of the treatments interfered with larval survival 1 or 2 days after treatment.

Activity

Activity was examined both early in the behavioral assay, as an average of activity during the first hour of imaging, and late in the assay, during period 15 (Fig 4). Early and late activity values were determined when larvae were imaged without visual or acoustic stimuli. We found that the calcineurin inhibitors CsA and FK506 increased early larval activity in comparison to the DMSO control (Fig 4a). Rapamycin also increased early activity, with activity values that exceeded activity in the DMSO control and FK506 treatment group. In contrast, proINDY treatments induced a decrease in early activity, in comparison to DMSO controls. We examined if the effects of CsA and FK506 could be rescued by the addition of proINDY and, conversely, if the effects of proINDY could be rescued by the addition of CsA and FK506. Our results show that this was indeed possible. For example, co-treatment of 10 μM CsA + 5 μM proINDY induced a decrease in early activity as compared to the CsA treatment alone, and induced an increase in early activity as compared to the proINDY treatment alone.

Figure 4.

Larval activity. A) Early activity averaged during the first hour of imaging. B) Late activity averaged during period 15. Larvae were treated at 5 dpf with DMSO (2 μl/ml), cyclosporine (CsA, 10 μM), tacrolimus (FK506, 1 μM), rapamycin (RM, 1 μM), proINDY (5PI = 5 μM proINDY, 10PI = 10 μM proINDY), or a combination of two treatments. For example, in the CsA+5PI group, larvae were co-treated with 10 μM CsA and 5 μM PI. Differences between corresponding treatment groups were examined for significance using a Chi-square test with a Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. * p < 0.05/14, ** p < 0.01/14, *** p < 0.001/14. N = 912, 372, 188, 263, 383, 275, 190, 178, 93 and 86 larvae in the 10 subsequent treatment groups. The colors of the asterisks indicate differences as compared to the DMSO control (black asterisks), CsA group (red asterisks), FK506 group (yellow asterisks) and PI group (green asterisks). In an ideal rescue experiment, the co-treatments will have red, yellow or green asterisks (indicating differences between the co-treatment and single treatment), but will not have black asterisks (the co-treatment is similar to the DMSO control).

Similar results were obtained in the analysis of late activity (Fig 4b). CsA, FK506 and rapamycin increased activity and proINDY decreased activity in comparison to the DMSO control. In addition, we again found a rescue of activity in co-treatments of CsA + proINDY and FK506 + proINDY. While the overall patterns of early and late activity were very similar in the rapamycin group and the FK506 group, we did observe a noticeable difference between the two treatments. Early activity is higher in the rapamycin group than the FK506 group (Fig 4a), while late activity is lower in the rapamycin group than the FK506 group (Fig 4b). Thus, the effects of FK506 and rapamycin on early and late activity were similar, but not the same. Based on the results described above, we conclude that the calcineurin-NFAT signaling pathway regulates activity in zebrafish larvae.

Visually-guided behaviors

The optomotor response or OMR was examined in 5 dpf larvae using red, green and blue lines as well as red lines that move 16 times faster than all other lines. The optomotor response was calculated by subtracting the average larval position in two subsequent 10-minute periods, when lines moved down and then up (see Fig 3). Optomotor responses were examined in all 10 treatment groups to determine if visually-guided behaviors are affected by modulation of calcineurin signaling (Fig 5). We first analyzed the visually-guided response to red lines (Fig 5a). Larvae treated with the calcineurin inhibitors CsA and FK506 displayed decreased optomotor responses, compared to the DMSO vehicle control. Rapamycin did not induce a significant change in the optomotor response, in comparison to the DMSO control. The optomotor response of the rapamycin treatment group was higher than the optomotor response of the FK506 treatment group. Treatment with 5 μM ProINDY led to an increased optomotor response in comparison to the DMSO control. This excessive optomotor response can be rescued by co-treatment with CsA or FK506. Similar results were obtained when analyzing responses to green lines (Fig 5b) and blue lines (Fig 5c). The analysis of larval responses to fast red lines (Fig 5d) revealed a similar CsA-induced decrease in the optomotor response and proINDY-induced increase in the optomotor response. Based on the differential OMR observed across treatment groups, we conclude that the calcineurin-NFAT signaling pathway affects optomotor responses in zebrafish larvae.

Figure 5.

Optomotor response (OMR). A) Response to moving red lines. B) Response to moving green lines. C) Response to moving blue lines. D) Response to red lines, moving 16x faster than the moving lines in A-C. Larvae were treated at 5 dpf with DMSO (2 μl/ml), cyclosporine (CsA, 10 μM), tacrolimus (FK506, 1 μM), rapamycin (RM, 1 μM), proINDY (5PI = 5 μM proINDY, 10PI = 10 μM proINDY), or a combination of two treatments. Differences between corresponding groups were examined for significance using a Chi-square test with a Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. N = 912, 372, 188, 263, 383, 275, 190, 178, 93 and 86 larvae in the 10 subsequent treatment groups. * p < 0.05/14, ** p < 0.01/14, *** p < 0.001/14.

Acoustic startle responses

Previous studies have shown that zebrafish larvae will repeatedly startle when exposed to infrequent acoustic stimuli at 20-second intervals, but habituate to frequent acoustic stimuli at 1-second intervals [20, 21]. We examined these startle responses in four 10-minute periods: period 15 without acoustic stimuli, period 16 with infrequent acoustic stimuli, period 17 with frequent stimuli and period 18 with infrequent stimuli (Fig 6). As anticipated, DMSO-treated control larvae displayed stable activity during period 15, increased activity during period 16, gradually decreasing activity during period 17, and increased activity during period 18 (Fig 6a). In contrast, the CsA-treated larvae displayed increased activity throughout period 17, which indicates that larvae lost the ability to habituate, and continuously startled in response to frequent acoustic pulses at 1-second intervals. To examine these effects in more detail, we measured habituation, acoustic startle, and 1-second excitability in all 10 treatment groups. CsA and FK506-treated larvae displayed decreased habituation, as compared to the DMSO-treated controls (Fig 6b). In contrast, rapamycin-treated larvae displayed normal habituation, which did not differ significantly from the DMSO controls and was elevated compared to habituation in the FK506-treated larvae. Startle responses were slightly elevated after treatment with proINDY (Fig 6c). CsA and FK506 treatment led to an increase in excitability, compared to excitability in the DMSO controls (Fig 6d). Rapamycin treatment also increased excitability in comparison to the DMSO controls, although the level of excitability was lower than observed in the FK506-treated larvae. The effects of CsA and FK506 on larval excitability could not be rescued by co-treatment with proINDY. In fact, co-treatment of FK506 and proINDY led to a large increase in excitability, which was higher than the excitability observed with either compound alone.

Figure 6.

Responses to acoustic stimuli. A) Example of one imaging experiment analyzed during the final 40 minutes in 6-second intervals. B) Habituation to acoustic stimuli at 1-second intervals (first 5 minutes minus last 5 minutes of period 17). C) Startle responses (average activity in period 16 minus period 17). D) Excitability by acoustic stimuli at 1 second intervals (average activity in period 17 minus period 16). Larvae were treated at 5 dpf with DMSO (2 μl/ml), cyclosporine (CsA, 10 μM), tacrolimus (FK506, 1 μM), rapamycin (RM, 1 μM), proINDY (5PI = 5 μM proINDY, 10PI = 10 μM proINDY), or a combination of two treatments. Differences between corresponding groups were examined for significance using a Chi-square test with a Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. N in panel A = 96 larvae per treatment group. N in panel B, C and D = 912, 372, 188, 263, 383, 275, 190, 178, 93 and 86 larvae in the 10 subsequent treatment groups. * p < 0.05/14), ** p < 0.01/14), *** p < 0.001/14).

Based on the effects of CsA and FK506, we conclude that habituation, startle responses and excitability are regulated by calcineurin signaling. However, the adverse effect of proINDY on FK506-induced hyperexcitability is not easily explained by calcineurin-NFAT signaling and may suggest the involvement of other calcineurin signaling pathways.

Recovery of behavior at 6 and 7 dpf

Zebrafish larvae were treated and imaged at 5 dpf, rinsed, grown in egg water, and imaged again at 6 and 7 dpf to assess the recovery of behavior. To evaluate the effects of five single treatments on multiple behaviors at 5, 6 and 7 dpf, we calculated treatment-induced changes as compared to the DMSO control and color coded the differences in behavior (Fig 7). The color-coded figure provides a summary of all experiments at 5 dpf, highlighting the observed changes in behavior at the time of initial imaging. CsA and FK506 treatments increased activity, decreased optomotor responses and increased excitability. In contrast, proINDY treatments decreased activity, increased optomotor responses and increased excitability. A few treatments showed a 6 dpf withdrawal effect, where changes in behavior were opposite to the changes in behavior at 5 dpf. For example, in the CsA treatment group activity was elevated at 5 dpf and decreased at 6 dpf. In the same treatment group, the optomotor response to fast red lines was suppressed at 5 dpf and elevated at 6 dpf. The summary figure shows that most, but not all, behaviors recovered in two days after treatment.

Figure 7.

Recovery of behavior in 6 and 7 day-old larvae. After treatment and initial imaging at 5 days post fertilization (dpf), zebrafish larvae were grown in egg water and imaged again at 6 and 7 dpf. Changes in behavior were calculated (Treatment - DMSO) and color coded for a visual evaluation of altered behaviors. Note that most, but not all behaviors, recovered two days after the treatment at 7 dpf. Measurements of behavior included activity in the first hour (1hr) and period 15 (P15), optomotor responses to moving lines in red (R), green (G), blue (B), fast red (FR) and all colors and speeds combined (RGB), startle response (S), habituation (Hab) and excitability (E).

Cluster analysis of behavioral profiles

Values of multiple behaviors, as shown in Figure 7, are often referred to as ‘behavioral profiles’ and are well suited for hierarchical cluster analysis. The cluster analysis evaluates if various treatments induce similar behavioral profiles. Cluster analysis of the 5 dpf data revealed that CsA and FK506 treatments cluster together, indicating a profile specific to calcineurin inhibition (Fig 8). The cluster analysis has sufficient phenotypic resolution to separate the behavioral profile of FK506 from rapamycin, two macrolide immunosuppressants with similar structures but different molecular targets [22]. Both concentrations of proINDY induce similar changes in behavior and cluster together. The proINDY behavioral profile is nearly opposite to the profile induced by inhibition of calcineurin. Based on these results, we conclude that modulators of calcineurin signaling induce specific behavioral profiles that can be grouped by cluster analyses.

Figure 8.

Hierarchical cluster analysis of behavioral profiles. Behaviors at 5 dpf were analyzed in Cluster 3.0, using the Euclidian distance metric with complete linkage. The clusters were then color coded in TreeView using a spectrum from green (25% decrease) to red (25% increase). Three main clusters were identified, each with a distinct behavioral profile: 1) the calcineurin inhibitors FK506 and CsA, 2) DMSO and rapamycin (RM), and 3) the DYRK1A inhibitor ProINDY (PI) at two concentrations. Measurements behavior include activity in the first hour (1hr) and period 15 (P15), optomotor responses to moving lines in red (R), green (G), blue (B), fast red (FR) and all colors and speeds combined (RGB1), startle response (S), habituation (Hab) and excitability (E).

Discussion

Modulation of calcineurin signaling

The current study shows that zebrafish larvae serve as a valuable model to study the risks and benefits of treatments that modulate calcineurin signaling. Using automated analyses of behavior, we found that the calcineurin inhibitors CsA and FK506 increase activity and decrease optomotor responses. Conversely, the DYRK inhibitor proINDY induces opposite effects, i.e. a decrease in activity and an increase in optomotor responses. These results are consistent with models of calcineurin-NFAT signaling (Fig 1) and suggest that small-molecule treatments aimed to restore calcineurin signaling have beneficial effects on activity and visually-guided behaviors. This idea is supported by the observed rescues of behavior in co-treatments of calcineurin inhibitors and proINDY.

Other signaling pathways

Some changes in behavior cannot be easily explained by the calcineurin-NFAT model. Specifically, CsA and FK506 treatments lead to an increase in acoustic excitability. These larvae continuously startle, without habituation, in response to acoustic stimuli at 1-second intervals. This behavior is not rescued by co-treatment with proINDY. Instead, such co-treatments induce an exacerbated phenotype. These results indicate that excitability may not be regulated by calcineurin-NFAT signaling and suggest the involvement of other calcineurin signaling pathways. For example, calcineurin may act by dephosphorylation of other signaling proteins such as CREB, GSK-3 and BAD [5]. Overall, the observed hyperexcitability phenotype indicates that small-molecule treatments aimed to restore calcineurin signaling can induce adverse side effects.

Cluster analysis

Multiple measures of behavior were organized in behavioral profiles, which are suitable for hierarchical cluster analysis. Cluster analyses are typically used to examine gene expression patterns, but have also been successfully used in the analysis of behavior [11–13]. The cluster analysis performed in this study revealed a specific behavioral profile for calcineurin inhibition. In addition, the analysis had sufficient phenotypic resolution to distinguish FK506 and rapamycin, which are both macrolide immunosuppressants with similar structures, but that affect different signaling pathways [22].

Clinical significance

Modulated calcineurin signaling is associated with neural dysfunction in Down syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease. In Down syndrome (trisomy 21), the extra copy of chromosome 21 leads to overexpression of both the Down Syndrome Critical Region gene 1 (DSCR1), also called the Regulator of Calcineurin (RCAN1), and a dual-specificity tyrosine phosphorylation-regulated kinase (DYRK1A), which both suppress calcineurin signaling pathways [4]. The suppressed calcineurin signaling pathway may affect fetal development as well as neural function later in life. INDY and other DYRK inhibitors have been proposed as therapeutics to restore calcineurin-NFAT signaling in Down syndrome [25–27]. People with Down syndrome frequently develop Alzheimer’s disease in their fifties or sixties, although it is unclear if this is caused by a suppression of calcineurin signaling or by the gene for the Amyloid Precursor Protein (APP), which is also located on chromosome 21 [5, 26, 28]. In fact, various studies have shown that calcineurin signaling is elevated, rather than suppressed, in Alzheimer’s disease [5–8]. The activation of calcineurin leads to dephosphorylation of various proteins, including the nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT), BCL2-associated death protein (BAD) and glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3), which in turn induce various hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease, such as inflammation, cell death, and hyperphosphorylation of tau [5]. Based on this model, the inhibition of calcineurin with cyclosporine or tacrolimus may serve as a viable therapeutic strategy for treating early stage Alzheimer’s disease [5, 9].

The automated analysis of zebrafish behavior may be used to examine other previously identified DYRK and calcineurin inhibitors that may restore neural function without adverse side effects. Such inhibitors are likely to have clinical significance in various calcineurin-related disorders, including Down syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease [3–8, 26, 28]. Calcineurin and DYRK inhibitors that are not used in medicine would need to be further examined for efficacy and safety in a mammalian model system, such as the mouse, before initiating clinical trials. This route makes use of the strengths of various model systems, i.e. zebrafish are well suited for large-scale screens and mice are well suited for more detailed pre-clinical studies. In addition, a comparative approach using both zebrafish and mice can reveal fundamental mechanisms that are critical to neural function, since these core mechanisms have been conserved in the past 400 million years [29]. A more direct bench-to-bedside approach may be possible if specific calcineurin inhibitors or DYRK inhibitors are already used in medicine or are natural products that are part of our diet. In these cases, human population studies could reveal beneficial effects in neural function, similar to the beneficial effects of CsA and FK506 in the prevention of Alzheimer’s disease [9].

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Zebrafish larval behavior can be imaged in vivo at an in vitro scale

Modulators of calcineurin signaling affect behavior

Our studies revealed beneficial and adverse effects of small-molecule therapeutics

The findings have clinical relevance in Down syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease

Acknowledgments.

We would like to thank Bethany Arabic for prior work on the optimization of visual and acoustic stimuli.

Funding. This work was supported by the following grants from the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation: NIH R01GM136906 (R.C.), NIH R01EY024562 (R.C.), NSF EPSCoR 1655221 (R.C.), P20GM119943 (J.A.K.), and NIH P01AG051449 (J.A.K.).

Footnotes

Competing interests. The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Azzi JR, Sayegh MH, Mallat SG, Calcineurin inhibitors: 40 years later, can’t live without, J Immunol 191(12) (2013) 5785–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Furman JL, Norris CM, Calcineurin and glial signaling: neuroinflammation and beyond, J Neuroinflammation 11 (2014) 158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Saraf J, Bhattacharya P, Kalia K, Borah A, Sarmah D, Kaur H, Dave KR, Yavagal DR, A Friend or Foe: Calcineurin across the Gamut of Neurological Disorders, ACS Cent Sci 4(7) (2018) 805–819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Arron JR, Winslow MM, Polleri A, Chang CP, Wu H, Gao X, Neilson JR, Chen L, Heit JJ, Kim SK, Yamasaki N, Miyakawa T, Francke U, Graef IA, Crabtree GR, NFAT dysregulation by increased dosage of DSCR1 and DYRK1A on chromosome 21, Nature 441(7093) (2006) 595–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Reese LC, Taglialatela G, A role for calcineurin in Alzheimer’s disease, Curr Neuropharmacol 9(4) (2011) 685–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Kocahan S, Dogan Z, Mechanisms of Alzheimer’s Disease Pathogenesis and Prevention: The Brain, Neural Pathology, N-methyl-D-aspartate Receptors, Tau Protein and Other Risk Factors, Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci 15(1) (2017) 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Popugaeva E, Pchitskaya E, Bezprozvanny I, Dysregulation of neuronal calcium homeostasis in Alzheimer’s disease - A therapeutic opportunity?, Biochem Biophys Res Commun 483(4) (2017) 998–1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Sompol P, Norris CM, Ca(2+), Astrocyte Activation and Calcineurin/NFAT Signaling in Age-Related Neurodegenerative Diseases, Front Aging Neurosci 10 (2018) 199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Taglialatela G, Rastellini C, Cicalese L, Reduced Incidence of Dementia in Solid Organ Transplant Patients Treated with Calcineurin Inhibitors, J Alzheimers Dis 47(2) (2015) 329–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Thorn RJ, Dombroski A, Eller K, Dominguez-Gonzalez TM, Clift DE, Baek P, Seto RJ, Kahn ES, Tucker SK, Colwill RM, Sello JK, Creton R, Analysis of vertebrate vision in a 384-well imaging system, Sci Rep 9(1) (2019) 13989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Bruni G, Rennekamp AJ, Velenich A, McCarroll M, Gendelev L, Fertsch E, Taylor J, Lakhani P, Lensen D, Evron T, Lorello PJ, Huang XP, Kolczewski S, Carey G, Caldarone BJ, Prinssen E, Roth BL, Keiser MJ, Peterson RT, Kokel D, Zebrafish behavioral profiling identifies multitarget antipsychotic-like compounds, Nat Chem Biol 12(7) (2016) 559–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Kokel D, Bryan J, Laggner C, White R, Cheung CY, Mateus R, Healey D, Kim S, Werdich AA, Haggarty SJ, Macrae CA, Shoichet B, Peterson RT, Rapid behavior-based identification of neuroactive small molecules in the zebrafish, Nat Chem Biol 6(3) (2010) 231–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Rihel J, Prober DA, Arvanites A, Lam K, Zimmerman S, Jang S, Haggarty SJ, Kokel D, Rubin LL, Peterson RT, Schier AF, Zebrafish behavioral profiling links drugs to biological targets and rest/wake regulation, Science 327(5963) (2010) 348–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Nery LR, Eltz NS, Hackman C, Fonseca R, Altenhofen S, Guerra HN, Freitas VM, Bonan CD, Vianna MR, Brain intraventricular injection of amyloid-beta in zebrafish embryo impairs cognition and increases tau phosphorylation, effects reversed by lithium, PLoS One 9(9) (2014) e105862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Colwill RM, Creton R, Imaging escape and avoidance behavior in zebrafish larvae, Rev Neurosci 22(1) (2011) 63–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Thorn RJ, Clift DE, Ojo O, Colwill RM, Creton R, The loss and recovery of vertebrate vision examined in microplates, PLoS One 12(8) (2017) e0183414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Liew WC, Orban L, Zebrafish sex: a complicated affair, Brief Funct Genomics 13(2) (2014) 172–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Clift D, Richendrfer H, Thorn RJ, Colwill RM, Creton R, High-throughput analysis of behavior in zebrafish larvae: effects of feeding, Zebrafish 11(5) (2014) 455–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Naumann EA, Fitzgerald JE, Dunn TW, Rihel J, Sompolinsky H, Engert F, From Whole-Brain Data to Functional Circuit Models: The Zebrafish Optomotor Response, Cell 167(4) (2016) 947–960 e20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Wolman MA, Jain RA, Liss L, Granato M, Chemical modulation of memory formation in larval zebrafish, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108(37) (2011) 15468–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Best JD, Berghmans S, Hunt JJ, Clarke SC, Fleming A, Goldsmith P, Roach AG, Non-associative learning in larval zebrafish, Neuropsychopharmacology 33(5) (2008) 1206–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Vellanki S, Garcia AE, Lee SC, Interactions of FK506 and Rapamycin With FK506 Binding Protein 12 in Opportunistic Human Fungal Pathogens, Front Mol Biosci 7 (2020) 588913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Clift DE, Thorn RJ, Passarelli EA, Kapoor M, LoPiccolo MK, Richendrfer HA, Colwill RM, Creton R, Effects of embryonic cyclosporine exposures on brain development and behavior, Behav Brain Res 282 (2015) 117–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Siebel AM, Menezes FP, Schaefer I. da Costa, Petersen BD, Bonan CD, Rapamycin suppresses PTZ-induced seizures at different developmental stages of zebrafish, Pharmacol Biochem Behav 139 Pt B (2015) 163–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ogawa Y, Nonaka Y, Goto T, Ohnishi E, Hiramatsu T, Kii I, Yoshida M, Ikura T, Onogi H, Shibuya H, Hosoya T, Ito N, Hagiwara M, Development of a novel selective inhibitor of the Down syndrome-related kinase Dyrk1A, Nat Commun 1 (2010) 86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Kim H, Lee KS, Kim AK, Choi M, Choi K, Kang M, Chi SW, Lee MS, Lee JS, Lee SY, Song WJ, Yu K, Cho S, A chemical with proven clinical safety rescues Down-syndrome-related phenotypes in through DYRK1A inhibition, Dis Model Mech 9(8) (2016) 839–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Jarhad DB, Mashelkar KK, Kim HR, Noh M, Jeong LS, Dual-Specificity Tyrosine Phosphorylation-Regulated Kinase 1A (DYRK1A) Inhibitors as Potential Therapeutics, J Med Chem 61(22) (2018) 9791–9810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Castro P, Zaman S, Holland A, Alzheimer’s disease in people with Down’s syndrome: the prospects for and the challenges of developing preventative treatments, J Neurol 264(4) (2017) 804–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Gerlai R, Evolutionary conservation, translational relevance and cognitive function: The future of zebrafish in behavioral neuroscience, Neurosci Biobehav Rev 116 (2020) 426–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.