Abstract

Background

Circulating tumor cells (CTCs) are responsible for the metastatic dissemination of colorectal cancer (CRC) to the liver, lungs and lymph nodes. CTCs rarity and heterogeneity strongly limit the elucidation of their biological features, as well as preclinical drug sensitivity studies aimed at metastasis prevention.

Methods

We generated organoids from CTCs isolated from an orthotopic CRC xenograft model. CTCs-derived organoids (CTCDOs) were characterized through proteome profiling, immunohistochemistry, immunofluorescence, flow cytometry, tumor-forming capacity and drug screening assays. The expression of intra- and extracellular markers found in CTCDOs was validated on CTCs isolated from the peripheral blood of CRC patients.

Results

CTCDOs exhibited a hybrid epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) state and an increased expression of stemness-associated markers including the two homeobox transcription factors Goosecoid and Pancreatic Duodenal Homeobox Gene-1 (PDX1), which were also detected in CTCs from CRC patients. Functionally, CTCDOs showed a higher migratory/invasive ability and a different response to pathway-targeted drugs as compared to xenograft-derived organoids (XDOs). Specifically, CTCDOs were more sensitive than XDOs to drugs affecting the Survivin pathway, which decreased the levels of Survivin and X-Linked Inhibitor of Apoptosis Protein (XIAP) inducing CTCDOs death.

Conclusions

These results indicate that CTCDOs recapitulate several features of colorectal CTCs and may be used to investigate the features of metastatic CRC cells, to identify new prognostic biomarkers and to devise new potential strategies for metastasis prevention.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13046-022-02263-y.

Keywords: Circulating tumor cells, Colorectal cancer, Organoids, Metastasis, Cancer stem cells

Background

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second leading cause of cancer death worldwide [1]. While early-stage CRC is associated with high survival rates, advanced disease remains usually incurable despite the improvement of therapeutic protocols [2]. Therefore, new tools are urgently needed for the investigation, prevention and treatment of metastatic disease. Circulating tumor cells (CTCs) contain the physical elements responsible for tumor dissemination and metastasis. CTCs analysis through liquid biopsies provides not only a full repertoire of tumor biological material (including proteins, lipids, sugars and nucleic acids) but also a sample of living tumor cells endowed with metastatic ability [3]. Thus, CTCs characterization offers the opportunity to gain mechanistic insights into the metastatic process and to exploit specific CTCs features for metastasis prevention and treatment [4, 5]. Despite the great potential of CTCs for cancer diagnosis, prognosis and therapy, the technical challenges associated to their isolation and enrichment hampered for long time a successful clinical use. Several experimental models have been developed to allow the expansion of CTCs from multiple tumors including lung, breast, esophageal, bladder, gastric, pancreatic, colorectal and prostate cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma and pleural mesothelioma [6–20]. Among these, 3D models such as spheroids and organoids provide an improved reconstruction of the tumor context [21–23], which can be further improved with the use of coculture systems [24, 25]. Furthermore, in vivo CTC-derived xenografts are currently under scrutiny as suitable models to investigate the metastatic process [8, 26, 27]. The development of CTCs-based preclinical models is tightly linked to overcoming the difficulties related to CTCs rareness. In fact, cultures derived from patients’ CTCs usually take many months to grow (which is incompatible with their use for treatment decision) and may be scarcely representative of tumor complexity [28]. Nonetheless, CTCs represent a unique source of patients’ material and a valuable in vitro proxy platform for anti-cancer drug testing. We have established an experimental model of CTCs-derived organoids (CTCDOs) obtained from circulating cancer cells spontaneously generated in an orthotopic CRC xenograft model derived from one CRC patient. CTCDOs recapitulated several features of CRC CTCs including a hybrid epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) state and elevated expression of stemness-associated proteins. Moreover, CTCDOs displayed a distinctive pattern of drug sensitivity that may be helpful for the identification of anti-metastatic strategies. While our results will need confirmation on a larger number of patients, this study provides a proof of principle for the generation of organoid cultures with CTCs features starting from a primary tumor sample. Further validations of such experimental model may lead to new approaches for the identification of prognostic biomarkers, therapeutic targets and personalized treatment strategies.

Methods

Generation and validation of patient-derived organoids (PDOs), xenograft-derived organoids (XDOs) and circulating tumor cell-derived organoids (CTCDOs)

CRC was obtained from a 69 years old male patient with a G2 stage IVA left colon tumor upon informed consent and approval by the Policlinico Umberto I Ethical Committee (RIF.CE: 4107 17/10/2016). For CTCs isolation, mice blood was centrifuged using Lympholyte Cell separation media (#CL5020, Cedarlane Laboratories, Canada) and CTCs were selected from the mononuclear cell layer by depleting hematopoietic cells with ferromagnetic anti-mCD45 coated microbeads (#130-052-301, Miltenyi Biotec, Germany) as detailed in Additional file 1: Supplementary Methods. Organoid cultures were generated from either single cell suspensions from patient’s tissue, from subcutaneous xenografts or from CTCs isolated from mouse blood, by the method described in [29]. Shortly, cells were resuspended in Growth Factor Reduced Matrigel® (Corning). Matrigel® was overlaid with 500 μL of colon cancer culture medium supplemented with 20 ng/mL recombinant human epidermal growth factor (EGF), 10 ng/ml human basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) (both from Peprotech), 10 nM Gastrin, 10 μM Y-27632, 10 μM SB202190 (Sigma-Aldrich) and 500 nM A83-01 (Tocris Bioscience, UK).

Antibodies and reagents

All antibodies are reported in Additional file 1: Supplementary Methods.

Animal procedures

Animal procedures were performed according to the Italian national animal experimentation guidelines (D.L.116/92) upon approval of the experimental protocol by the Italian Ministry of Health’s Animal Experimentation Committee (DM n. 292/2015 PR 23/4/2015). 6-week-old female NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (NSG) mice were used for all experiments. For orthotopic xenografting, 105 cells obtained from dissociated PDOs and transduced with a luciferase (LUC)-expressing lentiviral vector were injected in the colon wall during open laparotomy and tumor formation was monitored with an IVIS imaging system (Perkin Elmer). For CTCs isolation, 1 mL of whole blood was drawn via transthoracic cardiac puncture. For subcutaneous xenografts generation, 5 × 104 dissociated cells obtained from PDOs or CTCDOs resuspended in PBS/Matrigel were injected in the flank of NSG mice. Tumor volumes were calculated with the formula: π/6 x d2 x D, where d and D represent shorter and longer tumor measurements. For stem cell quantitation in xenografts, tumors were pooled and dissociated into single cells that were injected into secondary mice at serial doses ranging from 10 to 10.3 Five animals were used for each dilution point, and mice were recorded as negative when no graft appeared 24 weeks after inoculation.

CTCs detection in mouse peripheral blood

CTCs were identified with the CellSearch® technology (Menarini Silicon Biosystems) as described in Additional file 1: Supplementary Methods.

CTCs isolation from CRC patients

Peripheral blood was obtained from patients with metastatic CRC (Additional file 2: Table S1 and Additional file 1: Supplementary Methods) and CTCs were isolated with the Screen Cell Size-Isolation Device (ScreenCell®, France) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All participants provided informed consent to the study.

Immunohistochemistry, flow cytometry, immunofluorescence, clonogenicity assay and single cell cloning, invasion/migration assay and immunoblotting

Please refer to Additional file 1: Supplementary Methods.

Drug screening

Anti-cancer compounds and low toxicity compounds listed in Additional file 3: Table S2 were purchased from Selleck Chemicals. Dissociated organoid cells were plated in Medium/Matrigel at 3500 cells/well in triplicate 72 h before drug treatment. Organoids were treated for 6 days in a humidified atmosphere at 37 °C, 5% CO2 and drug-containing medium was replaced every 72 h. Cell viability was determined with CellTiterGlo 3D viability assay (Promega). Further details are provided in Supplementary Methods, Additional file 1.

Proteome profiler arrays

The expression of stem cell- cancer- and stress-related proteins was evaluated with Proteome Profiler Human Pluripotent Stem Cell Array Kit (#ARY010), Proteome Profiler Human XL Oncology Array (#ARY026) and Proteome Profiler Human Cell Stress Array Kit (#ARY018) all from R&D Systems. Protein list is available in Additional file 4: Table S3. Further details are provided in Supplementary Methods, Additional file 1.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 4.0 for Windows (GraphPad Software) with unpaired Student’s t test. Results are presented as the mean ± SD or mean ± SEM where appropriate. Statistical significance is expressed as *, P < 0.05, **, P < 0.01 and ***, P < 0.001. Statistical analyses of Proteome Profiler and drug screening are described in the specific Supplementary Methods sections. Serial transplantation/limiting dilution assays were analyzed by extreme limiting dilution analysis (ELDA) software [30]. Principal Component Analysis was applied so to get a synthetic index of potency in the two tests (PC1) together with an independent index (PC2) of differential activity. The dose/effect and relative potency relationship of low-toxicity compounds was estimated in terms of LD50 by means of a logarithmic dose/effect relation model Vitality = a – b*log(dose).

Results

Workflow for CTCs-derived organoid generation from an orthotopic/metastatic mouse xenograft model

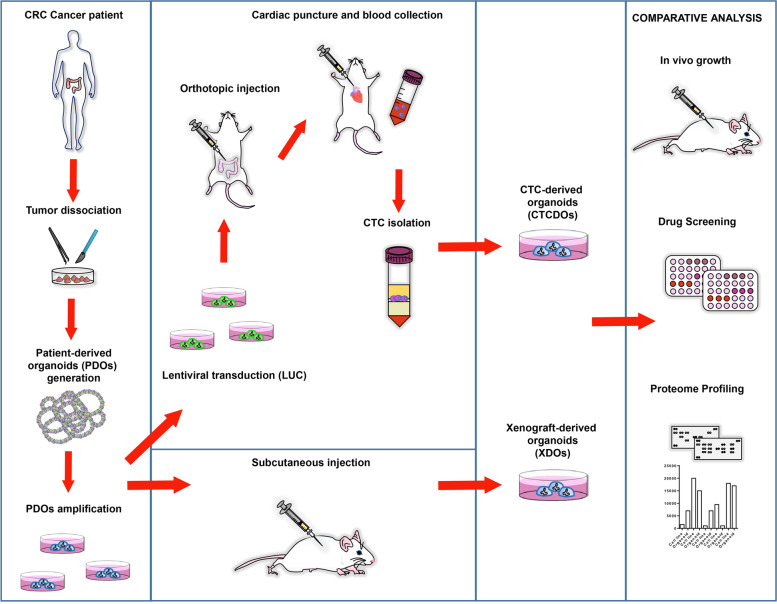

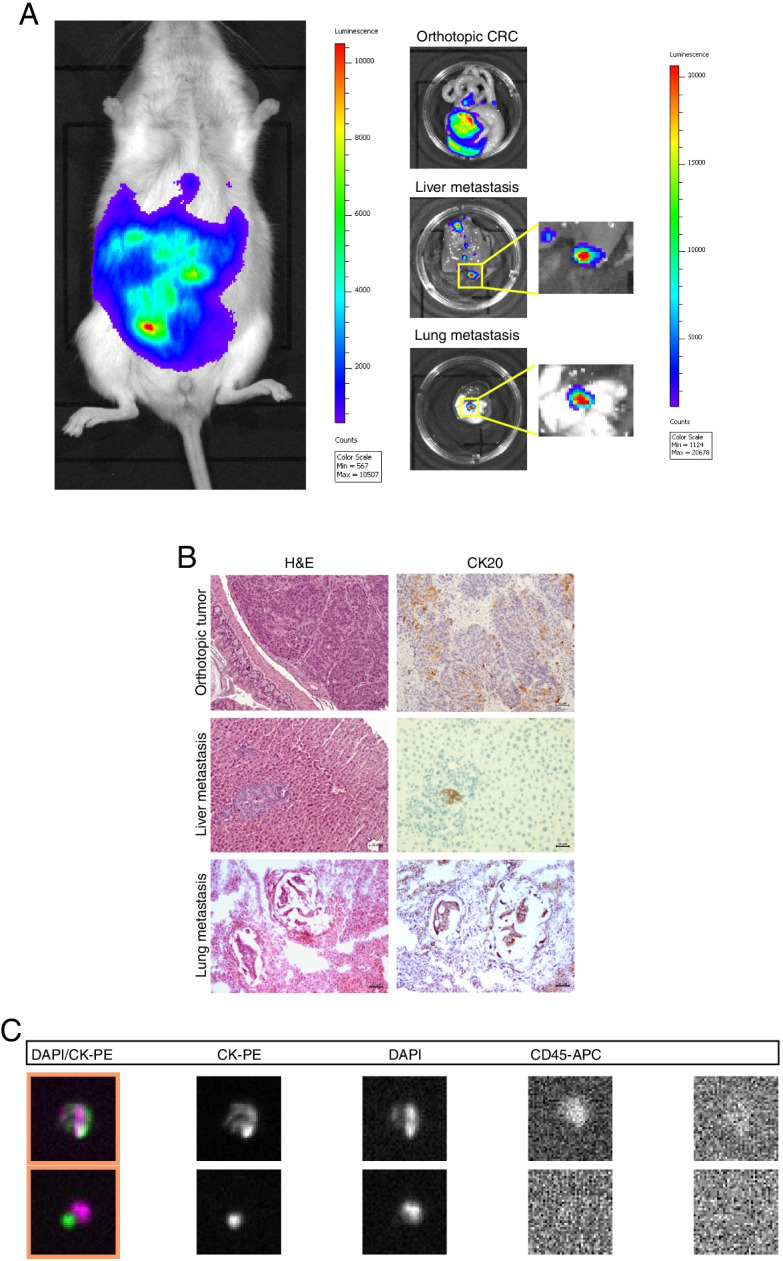

The workflow for CTCDOs generation is illustrated in Fig. 1. Tumor tissue derived from the surgical resection of a stage IV colonic adenocarcinoma was dissociated into single cells and used to generate patient-derived organoids (PDOs) according to the method originally created by Sato and coworkers [29]. MSI status and mutational profile of the tumor of origin are reported in Additional file 5, Fig. S1A and Fig. S1B. Short tandem repeat (STR) analysis of the primary tumor and PDOs confirmed their common cellular origin (data not shown). PDOs were also validated for their capacity to generate subcutaneous tumor xenografts that displayed the same histological structure of the patient’s tumor of origin (Additional file 5: Fig. S1C). The efficiency of PDOs generation from surgical specimens in our hands is around 90%, while subcutaneous PDOs engraftment has a 100% success rate. PDOs were then transduced with a LUC-encoding lentiviral vector to allow bioluminescence-based monitoring of tumor growth, and subsequently inoculated orthotopically into the colon of immunocompromised NSG mice. Orthotopic CRC xenografts spontaneously generate liver and lung metastases, thus recapitulating the metastatic process of human CRC (Fig. 2A and Additional file 6: Fig. S2) [31, 32]. The procedure of PDOs orthotopic xenografting in our model has an efficiency of 70-80%. Histological structure and Cytokeratin 20 (CK20) staining of orthotopic xenografts and of the deriving hepatic and pulmonary metastases confirmed their CRC origin (Fig. 2B). Analogously to human tumors, orthotopic CRC xenografts release CTCs, which were detected in the mouse peripheral blood with the CellSearch® platform as EpCAM+/CK (cytokeratins)+/mCD45− cells (Fig. 2C). In order to collect CTCs, mouse blood was harvested from orthotopic/metastatic xenografts by cardiac puncture, and then CTCs were isolated by density centrifugation and negative selection with murine anti-CD45 antibody (mCD45) (see Methods and Additional file 1: Supplementary Methods sections). Of note, a minority of mice bearing orthotopic-metastatic xenografts had detectable CTCs (as described in the following section) and thus CTCs isolation from mouse peripheral blood represents the limiting step of the workflow illustrated in Fig. 1. CTCs were then cultivated to generate CTCDOs. Alternatively, PDOs were used to obtain subcutaneous xenografts and xenograft-derived organoids (XDOs) that were used as a control for subsequent experiments in comparison with CTCDOs, to rule out the possibility that the effects seen in CTCDOs may be due to cell passage in mouse.

Fig. 1.

Establishment of organoid cultures generated from CRC patients (PDOs), subcutaneous xenografts (XDOs) or CTCs (CTCDOs). PDOs were directly generated from a colon adenocarcinoma surgically removed from a CRC patient. To obtain CTCDOs, PDOs were expanded, transduced with a luciferase-(LUC) encoding vector and orthotopically injected in the colon of immunocompromised mice. CTCs were then isolated from mouse peripheral blood collected by cardiac puncture and used to produce CTCDOs. XDOs were generated from subcutaneous xenografts and used a control for comparative in vitro and in vivo analyses

Fig. 2.

The orthotopic CRC xenograft model recapitulates the physiological metastatic process. A LUC-expressing PDOs were orthotopically injected into the colon of NSG mice, which were monitored for tumor growth by bioluminescent imaging (left panel). Upon sacrifice, orthotopic tumors and metastases were removed and quantified by bioimaging (central panels and right graph). B Paraffin-embedded section of PDOs-derived orthotopic tumor, liver and lung metastases were stained with Hematoxylin/Eosin (H&E, left panels) and cytokeratin-20 (CK20, right panels), 20x magnification. C Representative images of EpCAM-positive/cytokeratins (CK)-positive circulating tumor cells detected in mice whole blood. Abbreviations: CK-PE, cytokeratin (green); PE, phycoerythrin; DAPI; 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (violet); CD45-APC; APC, allophycocyanin

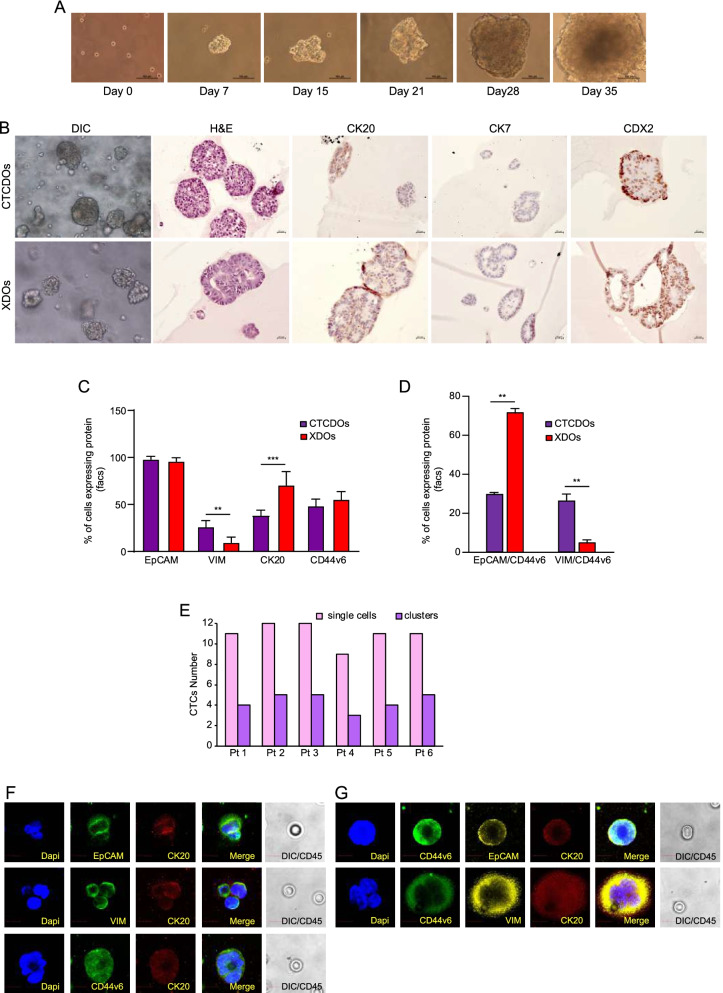

Generation and phenotypic characterization of CTC-derived organoid cultures

In order to obtain CTCDOs, we generated orthotopic CRC xenografts in 8 mice. We destined the blood of 4 mice to the CellSearch® analysis shown in Fig. 2C, which detected CTCs in 1/4 mice (two CTCs in one mouse and none in the other three mice). The remaining four mice were used directly for CTCs isolation, without prior CTCs detection. Mouse blood was processed through density centrifugation and negative selection with mCD45, and the resulting pellets were placed in organoid culture. One sample out of four generated CTCDOs, which were used for further analyses (Fig. 3A). CTCDOs showed a CK20+/CDX2+/CK7− phenotype typical of CRC (Fig. 3B). CTCDOs and XDOs were then analyzed by flow cytometry for the expression of markers associated to the epithelial/mesenchymal state (EpCAM, Vimentin), to intestinal differentiation (CK20) and to CRC stemness/metastatic ability (CD44v6) (Fig. 3C and Additional file 7: Fig. S3A-C). While EpCAM expression was comparable between CTCDOs and XDOs, Vimentin was more expressed in CTCDOs in line with a shift towards a mesenchymal state, while CK20 was decreased possibly reflecting a less differentiated state (Fig. 3C). The absolute levels of CD44v6 were comparable between CTCDOs and XDOs (Fig. 3C). To gain more insights into CD44v6 distribution on CTCDOs and XDOs, we analyzed CD44v6 expression in organoid subpopulations characterized by a prevalent epithelial (EpCAM+) or mesenchymal (Vimentin+) state. Interestingly, we observed that in CTCDOs the expression of CD44v6 was equally distributed among EpCAM+ cells and Vimentin+ cells, indicating their hybrid EMT state and high heterogeneity (Fig. 3D). By contrast, CD44v6 expression in XDOs was found prevalently on EpCAM+ cells (Fig. 3D). To investigate whether CTCDOs paralleled CRC CTCs in terms of phenotypic features, we isolated CTCs from the peripheral blood of six CRC patients (details in Additional file 2: Table S1) with the ScreenCell® technology in order to perform immunofluorescence analyses. The number of cells (both single CTCs and CTCs clusters) detected in the six patients used for this analysis is reported in Fig. 3E. Then, immunofluorescence analysis was performed on CTCs, confirming the expression of EpCAM, Vimentin and CD44v6 on CK20+/CD45− CTCs (Fig. 3F). Blood cells stained positive for CD45 (Additional file 7: Fig. S3D) and were excluded from the analyses. Moreover, double staining for EpCAM/CD44v6 and Vimentin/CD44v6 confirmed the presence of putative CD44v6+ metastatic cells characterized by a combined epithelial (EpCAM+) and mesenchymal (Vimentin+) phenotype, providing further evidence to CTCs heterogeneity (Fig. 3G).

Fig. 3.

Generation and phenotypic characterization of CTCDOs cultures. A Time course images of CTCDOs culture. B Images of paraffin embedded sections obtained from CTCDOs (upper panels) and XDOs (lower panels). From left to right: Differential interference contrast (DIC), H&E staining, cytokeratin-20 (CK20), cytokeratin-7 (CK7), Caudal Type Homeobox 2 (CDX2). C Flow cytometry experiments showing the percentage of EpCAM, Vimentin (VIM), CK20 and CD44v6 positive cells in CTCDOs (purple bars) and XDOs (red bars) cultures. Values are obtained as the ratio between positive cells and total cells multiplied by 100, and represent the mean ± SD of three independent experiments performed with technical replicates. D Percentage of EpCAM+/CD44v6+, VIM+/CD44v6+ cells in CTCDOs (purple bars) and XDOs (red bars). Values are obtained as the ratio between positive cells and total cells multiplied by 100, and represent the mean ± SD of three independent experiments performed with technical replicates. E CTCs enumeration performed on the whole ScreenCell® filters obtained from each patient (Pt 1-6). Aggregates containing ≥3 CD45-negative cells were considered as CTCs clusters. Single cells: pink bar, clusters: violet bar. F CTCs isolated from the peripheral blood of CRC patients and stained with EpCAM (green)/CK20 (red); VIM (green)/CK20 (red); CD44v6 (green)/CK20 (red); (G) CTCs isolated from the peripheral blood of CRC patients and stained with CD44v6 (green)/EpCAM (yellow)/CK20 (red) or CD44v6 (green)/VIM (yellow)/CK20 (red). Nuclei were stained with DAPI. CD45 staining was performed with diaminobenzidine (DAB) and detected on differential interference contrast (DIC) images, appearing negative on CTCs and positive on blood cells (Additional file 6: Fig. S2D). Images are representative of at least three CTCs isolated from three different patients. Magnification 60x, 5x zoom. Bar 10 μM

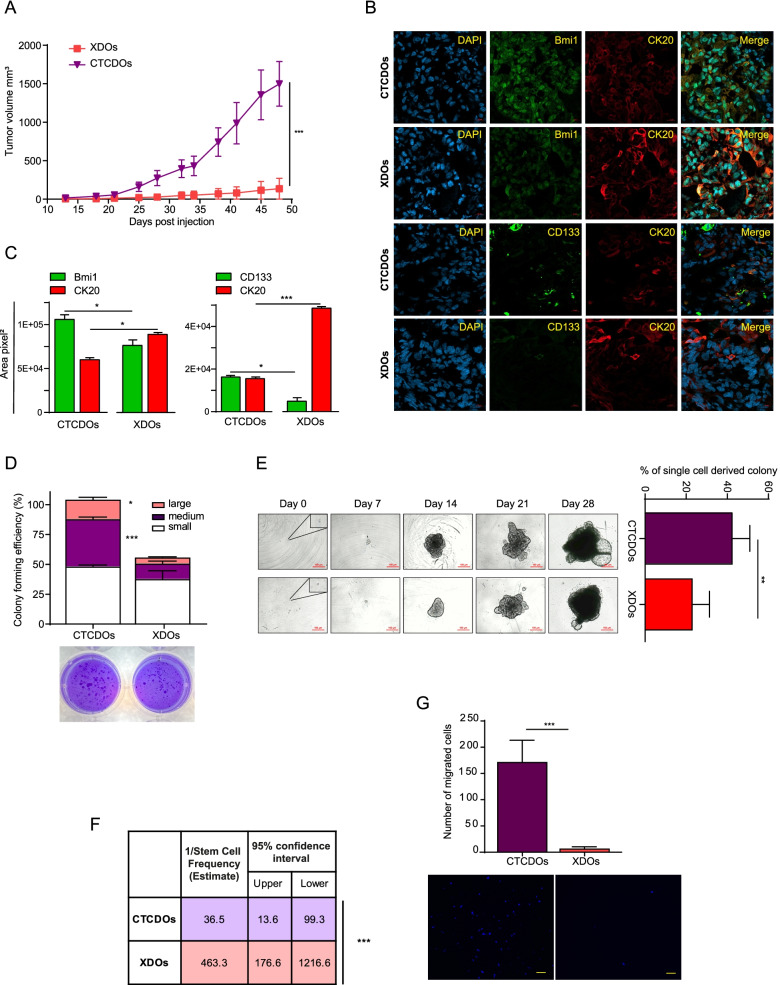

CTC-derived organoids exhibit increased aggressiveness, stem cell content and migratory ability

Previous studies showed that CTCs are characterized by stem cell properties and tumor-forming capacity [33, 34]. Therefore, we performed functional analyses to compare stemness and tumorigenicity in CTCDOs as compared to XDOs. First, we inoculated subcutaneously the same number of cells derived from XDOs or CTCDOs and we monitored subsequent tumor growth. Cells derived from CTCDOs generated more aggressive tumors as compared to XDOs-derived cells (Fig. 4A). Accordingly, we found a higher expression of the stem cell marker CD133 [35, 36] and of the self-renewal marker Bmi1 [37] in tumor xenografts sections derived from CTCDOs (Fig. 4B-C), while the differentiation marker CK20 was expressed at lower levels as compared to XDOs-derived xenografts. Cells isolated from tumor xenografts were placed in semisolid culture in order to evaluate their colony-forming ability. In such conditions, cells isolated from CTCDOs-derived tumors gave rise to a significantly higher number of colonies (particularly medium and large colonies) indicating an increased clonogenic and replicative capacity (Fig. 4D). This observation was confirmed by a liquid culture single-cell assay comparing the clonogenic capacity of cells derived from dissociated CTCDOs or XDOs (Fig. 4E). Then, we aimed to assess the relative amount of tumor-initiating cells (TICs) in CTCDOs or XDOs through an in vivo limiting dilution/serial transplantation assay. The relative TICs content calculated by the extreme limiting dilution assay (ELDA) [30] was 1/36,5 in CTCDOs and 1/463,3 in XDOs (Fig. 4F), providing further support to the enhanced stem cell content of CTCDOs. Finally, we compared the migratory and invasive capacity of CTCDOs and XDOs through the transwell migration/invasion assay. While XDOs were virtually unable to invade Matrigel and migrate towards the chemoattractant medium, CTCDOs exhibited a marked invasive and migratory capacity, thus reproducing a functional feature of metastatic cancer cells (Fig. 4G).

Fig. 4.

CTCDOs display increased aggressiveness, stem cell content and migratory ability. A Volume of subcutaneous tumor xenografts derived from XDOs (red line/squares) or CTCDOs (purple line/triangles). Mean ± SEM, 5 tumors per group. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 by unpaired Student’s t test with Welch’s correction. B Representative images of immunofluorescence staining (40x magnification) of Bmi1, CK20 and CD133 in xenograft sections obtained from tumor xenografts of Fig. 4A; nuclei were stained with DAPI. C Quantification of Bmi1, CK20 and CD133 performed on xenograft sections obtained from tumor xenografts of Fig. 4A, 5 fields/section. D Self-renewal capacity of cells isolated from xenografts of Fig. 4A, evaluated as colony formation in semisolid culture and expressed as normalized colony size/percentage over plated cells. Values represent the mean ± SD of three technical replicates. P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001 by unpaired Student’s t test. E Single-cell assay performed with CTCDOs- and XDOs-derived cells (right) and time course images of CTCDOs and XDOs cultures (left). 10x magnification, bar 100 μm. Values represent mean ± SD of three independent experiments. **P < 0.01 by unpaired Student’s t test. F Tumor initiating cells content of CTCDOs and XDOs cultures was evaluated through serial transplantation/limiting dilution assays and quantified with the extreme limiting dilution analysis (ELDA) software. Five mice were used for each dilution point. ***P < 0.001. G Invasion/migration assay performed with CTCDOs and XDOs. The upper panel graph indicates the number of migrated CTCDOs and XDOs, while the lower panels show representative images of nuclei of CTCDOs- and XDOs migrated cells stained with DAPI (10x magnification). Values represent mean ± SD of three independent experiments. ***P < 0.001

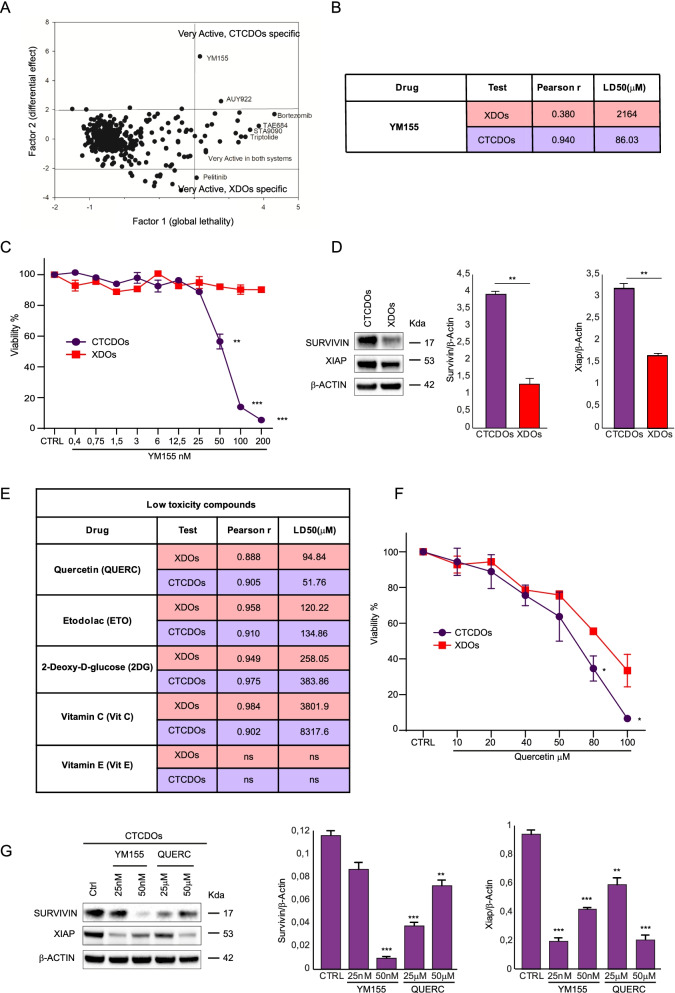

CTC-derived organoids have a distinctive therapy response profile and are more sensitive to drugs affecting the Survivin pathway

Few previous studies have investigated CTCs’ drug sensitivity profile [19, 38–40]. We performed a screening on CTCDOs and XDOs with a library of anti-cancer compounds and found that the two organoid cultures displayed a different drug sensitivity profile (Fig. 5A). In particular, XDOs were more sensitive to the EGFR inhibitor Pelitinib, whereas CTCDOs had an increased sensitivity to YM155, a drug targeting Survivin, and to the HSP90 inhibitor AUY922 (Luminespib). The LD50 of YM155 for XDOs and CTCDOs is shown in Fig. 5B. The differential response of CTCDOs and XDOs to YM155 was further confirmed by a dose-response cytotoxicity assay showing a highly significant difference starting from a dose of 50 nM (Fig. 5C). To gain more insights into the different effect of YM155 on CTCDOs and XDOs, we assessed the levels of Survivin and XIAP in the two cellular systems. As shown in Fig. 5D, CTCDOs expressed higher levels of both Survivin and XIAP, suggesting they may have an increased dependence on such pathway for their survival. The identification of a compound active on CTCs would be aimed at devising a therapeutic strategy for the prevention of metastatic disease. In this perspective, although YM155 (Sepantronium bromide) has successfully entered clinical trials, its pleiotropic mechanism of action may prevent its adoption for long-term therapeutic strategies involving non-metastatic patients. Therefore, in order to identify drugs potentially active on CTCs but with low toxicity on healthy tissues, we tested five additional compounds. Of these, three were chosen for their ability to inhibit EMT by interfering with metabolic pathways (Etodolac, 2-deoxy-D-glucose and vitamin C) [41] and two were chosen as multipurpose agents able to affect also the Survivin pathway (quercetin, vitamin E) [42]. The results of XDOs and CTCDOs challenging with different doses of the selected low toxicity compounds are shown in Fig. 5E, in Additional file 8 and in Fig. S4. While all the treatments with the exception of vitamin E were active (even if with a wide range of relative potency) with a statistically significant dose/effect, the only compound showing a significantly different effect (P < 0.05) between CTCDOs and XDOs was quercetin (Fig. 5E-F). Since both YM155 and quercetin have been shown to reduce cancer cell viability by decreasing Survivin protein levels [43, 44] we asked whether the same effect occurred in CTCDOs. An immunoblot analysis of Survivin and XIAP showed a decrease of both proteins upon treatment with either YM155 and quercetin, indicating this mechanism as a likely cause of CTCDOs death (Fig. 5G).

Fig. 5.

CTCDOs show a distinctive therapy response profile. A Principal component analysis (PCA) of cell viability assay performed with anti-cancer compounds (detailed in Additional file 3: Table S2) highlighting drugs very active on CTCDOs and XDOs, respectively. Drugs were used at a 200 nM concentration. B Schematic representation of YM155 potency (LD50, μM) and dose/effect relationship (Pearson r) in XDOs (red lines) and CTCDOs (purple lines). Doses of YM155 are reported in Fig. 5C. C Cell viability of CTCDOs (purple line/circles) and XDOs (red line/squares) treated with YM155 at the indicated concentrations. Values represent the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 by unpaired Student’s t test. D Left: immunoblot analysis of Survivin and XIAP on whole lysates of CTCDOs and XDOs. β-actin was used as a loading control. Right: quantification of immunoblot experiments (three replicates). E Schematic representation of low toxicity compounds potency (LD50, μM) and dose/effect relationship (Pearson r going from 0.88 to 0.98) in XDOs (red lines) and CTCDOs (purple lines). Doses of low toxicity compounds are reported in Additional file 3: Table S2. F Cell viability of CTCDOs- (purple line/circles) and XDOs (red line/squares) treated with quercetin (QUERC) at the indicated concentrations. Values represent mean ± SD of three independent experiments. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 by unpaired Student’s t test. G Left: immunoblot analysis of Survivin and XIAP on whole lysates of CTCDOs treated for 6 days with the indicated concentrations of YM155 and quercetin. β-actin was used as a loading control. Right: quantification of immunoblot experiments (three replicates)

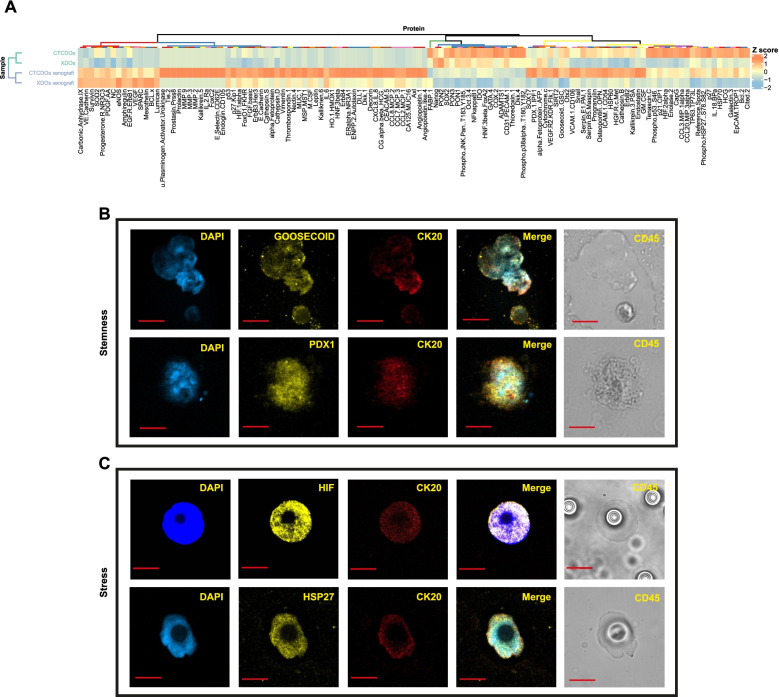

Proteome profiling of CTC-derived organoids reveals expression of factors involved in stemness and stress response that are also expressed in CRC CTCs

In order to generate a broader picture of proteins differentially expressed in CTCDOs and XDOs we analyzed the two systems with the Proteome Profiler Antibody Array®. In addition to CTCDOs and XDOs, we compared also subcutaneous xenografts derived from either CTCDOs or XDOs. Proteome analysis revealed an increased expression of factors involved in stemness (PDX1, Goosecoid, Oct3/4, SOX2, Delta-like protein/DLL1, Cited-2), stress response (Heat Shock Proteins HSP27, HSP60, HSP70, Hypoxia-Inducible Factors HIF-1α, HIF-2α), cell migration/invasion (Cathepsin D, Cathepsin S, Matrix Metalloproteinases MMP-2, MMP-3, MMP-9, c-Met) and EMT (Vimentin, Snail) in CTCDOs and/or in the deriving xenografts (Fig. 6A). Moreover, we observed an increased expression in CTCDOs of factors involved in antioxidant pathways (Manganese Superoxide Dismutase SOD2, Thioredoxin-1, Paraoxanase-1 and -2). The enhanced expression of HSPs, HIFs and antioxidant enzymes indicated that CTCDOs have an increased capacity to cope with oxidative stress, which has been recently recognized as a metastasis-promoting feature [45, 46] (Fig. 6A). A restricted number of endpoints was also validated by immunoblotting in CTCDOs, XDOs and in the respective xenografts (Additional file 9: Fig. S5). PDOs were also included in the analysis, providing a partial view of factor expression during the different stages of disease progression. Immunoblot analyses show that protein expression in PDOs was more similar to XDOs than to CTCDOs. Specifically, PDOs have lower levels of several factors (including B-cell lymphoma 2/Bcl-2, MMP2, Cathepsin D and Survivin) as compared to CTCDOs, suggesting that proteins related to tumor cell survival and aggressiveness increase during sequential stages of the disease. Notably, although xenografts tend to cluster together in the proteome profiler heatmap, CTCDOs-derived xenografts have a greater activation of signaling molecules involved in matrix remodeling, stress and EMT, even if compared to XDOs-derived xenografts. This observation substantiates the higher aggressiveness of CTCDOs-derived xenografts which cannot be attributed only to the in vivo passage but likely derives from the ability to recapitulates CTCs features. Finally, we ought to investigate whether selected factors that emerged from CTCDOs proteome profiling were also expressed in CTCs isolated from two CRC patients (Additional file 2: Table S1). Among stemness-related factors, we focused on the homeobox transcription factors Goosecoid and PDX1, as their expression is implicated in carcinogenesis and metastasis but was never detected in CTCs. In line with proteome profiling results, we found Goosecoid and PDX1 expression in CRC CTCs, possibly associated with a functional implication of these two factors in CRC metastasis (Fig. 6B). CTCs isolated from CRC patients also expressed high levels of stress-related proteins HIF-1α and phosphorylated HSP27 (Fig. 6C), suggesting a role in resistance to adverse microenvironmental conditions. CTCs observed positive for Goosecoid, PDX1, HIF1α and pHSP27 were respectively 3, 3, 12 and 3. Altogether, these observations indicate that CTCDOs recapitulate specific features of CRC CTCs such as the expression of stemness and stress response factors.

Fig. 6.

Proteome Profiler analysis of CTCDOs/CTCDOs-derived xenografts versus XDOs/XDOs-derived xenografts and selected protein validations on CRC CTCs. A Hierarchical clustering of Proteome Profiler results obtained on CTCDOs/XDOs and CTCDOs-derived tumor xenografts /XDOs-derived tumor xenografts (n = 2 pools of 3 tumors each). Clusters, identified for either antibodies or samples and based on optimal cut of dendrograms, are indicated by colored bars adjacent to dendrograms. The values represented by the heatmap correspond to normalized intensities of antibodies, standardized over the sample set analyzed (z score). A list of Proteome Profiler antibodies is reported in Additional file 4: Table S3. B Immunofluorescence analysis of stemness-associated factors Goosecoid and PDX1 on CTCs isolated from the peripheral blood of two CRC patients. C Immunofluorescence analysis of stress-associated factors HIF-1α and phospho-HSP27 on CTCs isolated from the peripheral blood of two CRC patients. Images are representative of at least three CTCs isolated from three different patients. Magnification 60x, 5x zoom, bar 10 μM

Discussion

The analysis of CTCs isolated from the peripheral blood of cancer patients can provide important cues that may be useful to support clinical decision making. In particular, the possibility to perform a small-scale phenotypic drug screen would allow the identification of treatment strategies with increased tumor-killing ability. However, drug testing on CTCs requires the realization of ex vivo models based on CTCs expansion. CTCs-based cultures systems have been fulfilled in several tumors [6–20] and new methods to improve CTCs survival in vitro are currently being explored by many laboratories. Applying the organoid technology to CTCs is a promising strategy that combines the advantages of organoid cultures (ability to reproduce the architecture and function of original tissue, high predictive power in preclinical studies) with the enormous potential of CTCs for precision oncology. So far, the direct derivation of organoids from CTCs has been achieved in prostate cancer [39, 47], ovarian cancer [48, 49] and head and neck cancer [50]. However, organoid generation from CTCs remains a challenging task due to CTCs rareness. A possible solution has been implemented by Mout and coworkers by collecting high CTCs numbers for organoid culture from the diagnostic leukapheresis of prostate cancer patients [39]. In this work we describe the generation and characterization of organoid cultures derived from CTCs isolated from an orthotopic/metastatic mouse model of CRC. The CTCDOs experimental model presented in this study provides several advantages as compared to other CTCs culture systems. First, organoids allow tumor cells to adopt a more physiological architecture, behavior and differentiation hierarchy as compared with other experimental systems [51], thus resulting in a more faithful reproduction of CTCs features. In fact, CTCDOs showed several molecular and functional features of CTCs including increased aggressiveness, tumor-forming capacity, migratory/invasive ability, heterogeneity and expression of proteins involved in stemness, stress response and EMT [46]. Secondly, the CTCDOs model bypasses the need to collect sufficient numbers of CTCs from the peripheral blood of cancer patients. Third, CTCDOs can be established early after diagnosis starting from surgical tumor specimens, theoretically allowing the generation cells with metastatic features even before the onset of metastatic disease. Due to the technical challenges in CTCs isolation and expansion, few studies have previously investigated CTCs drug sensitivity profiles. Such studies were performed on CTCs-derived cultures of prostate cancer [39, 40], breast cancer [19] and small cell lung cancer [38]. To our knowledge, this is the first time that a library of anticancer compounds is tested on CTCs-derived organoid cultures, thus providing new insights on CTCs patterns of drug sensitivity. Specifically, we found an increased cytotoxic efficacy of Survivin and HSP90 inhibitors in CTCDOs as compared to XDOs. These results prompted us to further search for compounds with low toxicity that would preferentially target CTCDOs by decreasing Survivin levels [42]. Accordingly, we observed that CTCDOs were significantly more sensitive to quercetin which, similarly to YM155, was able to decrease Survivin and XIAP levels. Finally, we produced a comprehensive profile of proteins involved in stemness, stress response and tumorigenesis in CTCDOs and CTCDOs-derived xenografts. In line with CTCDOs enhanced aggressiveness and tumor-forming capacity, we found an increased expression of several factors implicated in stemness maintenance both in normal and malignant tissues such as PDX1, Goosecoid, Oct3/4, SOX2, DLL1, Cited-2. Among these, the homeobox transcription factors Goosecoid and PDX1 have been previously shown to be involved respectively in EMT/metastasis of breast and liver carcinomas [52, 53] and in pancreatic tumorigenesis and metastasis formation [54, 55]. Goosecoid and PDX1 expression was found in CTCs isolated from CRC patients, suggesting that these factor may play a role also in CRC metastatic process. Finally, the high expression of factors involved in migration/tissue invasion (Cathepsin D, Cathepsin S, MMP-2, MMP-3, MMP-9, c-Met), stress response (HSP27, HSP60, HSP70, HIF-1α, HIF-2α) and antioxidant activity (SOD2, Thioredoxin-1, Paraoxanases) further confirms the metastatic propensity of CTCDOs. In particular, the enhanced antioxidant capacity has been recently indicated as a key feature of metastatic dissemination [45, 46], further substantiating the similarity between CTCDOs and metastasis-competent CRC cells. These results, if confirmed by further studies on a larger number of patients, will be useful to characterize new druggable targets in CTCs. In summary, the results presented in this study contribute to depict a picture of CTCs as cells endowed with particular plasticity, stemness, adaptability and aggressiveness. This view is in line with the finding, emerged in the last years, that CTCs disseminate early during cancer progression and may reside in distant organs for many years as dormant cells that retain metastatic potential [56]. Unravelling CTCs survival mechanisms and drug vulnerabilities carries important clinical implications, possibly allowing the development of strategies for metastasis prevention.

Conclusions

Our results provide preliminary evidence that CTCDOs may provide a suitable model to investigate CTCs molecular features, to identify timely strategies for metastasis prevention and to test personalized treatments. Future applications of the organoid technology to CTCs may open new perspectives by providing unprecedented insights onto the metastatic process, by allowing the detection of new CTCs biomarkers, therapeutic targets and chemoresistance mechanisms.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:. Supplementary Methods.

Additional file 2: Table S1. Information of CRC patients used to isolate CTCs. NA: Not Available; CT: Chemotherapy.

Additional file 3: Table S2. List of compounds used in the screening: drug name, targets Selleckchem catalogue number and doses are reported. Anti-cancer compounds (sheet 1) have been used at a 200 nM concentration, whereas low toxicity compounds (sheet 2) have been used at the indicated doses in order to identify the LD50 value reported in Fig. 5E.

Additional file 4: Table S3. List of proteins and raw endpoint values relative to the Proteome Profiler Arrays shown in Fig. 6A.

Additional file 5: Figure S1. MSI status/mutational profile of patient’s CRC and xenograft validation. (A) WES analysis was performed on the surgical sample used for organoid generation, allowing the estimation of mutation rates (hypermutated: more than 10 mutations per Megabase). High-grade microsatellite instability (MSI) was also detected. Both Non-Silent (blue) and Silent (orange) somatic variants are reported. (B) OncoPrint showing functionally relevant intragenic lesions in recurrently mutated genes. Half boxes and full boxes represent heterozygous and homozygous variants, respectively; colors are used to specify the type of mutation. Stars indicate germline mutations; multiple hits affecting the same gene are indicated by numbers. (C) Hematoxylin/Eosin staining of the primary patient’s tumor and of PDOs-derived subcutaneous tumor xenograft showing comparable histological structure. Magnification 20x.

Additional file 6: Figure S2. Growth and metastatization of orthotopic tumor xenografts recorded by bioimaging. Representative images of LUC-expressing PDOs orthotopically injected into the colon wall of NSG mice and monitored by bioluminescent imaging (IVIS imaging system) at different time points.

Additional file 7: Figure S3. CTCDOs phenotypic characterization. (A) Flow cytometry of purified CTCDOs stained for human EpCAM and mouse CD45 expression. (B) Representative flow cytometry plots performed on XDOs and CTCDOs for the expression of: EpCAM, VIM, CK20, CD44v6 shown in Fig. 3C. (C) Representative flow cytometry plots performed on XDOs and CTCDOs for the expression of CD44v6/EpCAM and CD44v6/Vimentin Fig. 3D. (D) Representative confocal images of CD45-positive (hematopoietic) cells present on ScreenCell® filters. Cells were stained with CD45/DAB (appearing as the dark staining in the differential interference contrast/DIC brightfield), CD44v6 (green), EpCAM (yellow) and CK20 (red). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Magnification 60x, 5x zoom, bar 10 μM.

Additional file 8: Figure S4. Linear regression of the effect of low toxicity compounds on CTCDOs and XDOs. Schematic representation trough linear regression of low toxicity compounds described in Fig. 5D and used at different indicated doses specified in Additional file 3: Table S2 (upper panel); detail of endpoints contained in the red square (lower panel).

Additional file 9: Figure S5. Selected protein validations on CTCDOs, XDOs, PDOs and CTCDOs/XDOs-derived xenografts. Left: immunoblot analysis of E-Cadherin, Vimentin, p21, P53, PON2, pHSP27 (Ser78), HIF-1α, Sirt2, Bcl-2, MMP2, Cathepsin D and Survivin on whole lysates of CTCDOs, XDOs, PDOs and CTCDOs/XDOs-derived xenografts (reported as CTCDOs xeno and XDOs xeno). β-actin and GAPDH were used as a loading control. Right: quantification of immunoblot experiments.

Acknowledgements

We thank Rachele Rossi, Paola Di Matteo, Daniele Macchia, Anna Pacca, Maria Teresa D’Urso, and Mario Falchi for excellent technical assistance and Emilia Stellacci for STR profile analysis.

Abbreviations

- CTC

Circulating tumor cells

- CRC

Colorectal cancer

- CTCDOs

CTCs-derived organoids

- EMT

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- PDX1

Pancreatic Duodenal Homeobox 1

- XDOs

Xenograft-derived organoids

- PDOs

Patient-derived organoids

- NSG

NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ

- LUC

Luciferase

- DAPI

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- SD

Standard Deviation

- SEM

Standard Error of Mean

- ELDA

Extreme limiting dilution analysis

- PCA

Principal Component Analysis

- LD50

Lethal dose 50

- CK

Cytokeratins

- EpCAM

Epithelial cell adhesion molecule

- CD45

Leucocyte common antigen

- MSI

Microsatellite instability

- STR

Short tandem repeat

- CDX2

Caudal Type Homeobox 2

- CD44v6

Variant 6 of the cell surface glycoprotein CD44

- CD133

Prominin-1

- Bmi1

Polycomb complex protein

- TIC

Tumor-initiating cells

- EGFR

Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor

- YM155

Sepantronium bromide

- HSP

Heat shock proteins

- AUY922

Luminespib

- XIAP

X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein

- Oct3/4

Octamer binding transcription factor 3/4

- SOX2

SRY-Box Transcription Factor 2

- DLL1

Delta-like protein

- Cited-2

Cbp/P300 Interacting Transactivator With Glu/Asp Rich Carboxy-Terminal Domain 2

- HIF

Hypoxia-inducible factor

- MMP

Matrix metalloproteinase

- c-Met

Tyrosine-protein kinase Met

- SOD2

Manganese superoxide dismutase

- p21Cip1

Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1

- p53

Tumor protein P53

- PON2

Paraoxonase 2

- SIRT2

Sirtuin 2

- Bcl-2

B-cell lymphoma 2

- GAPDH

Glyceraldehyde-3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase

Authors’ contributions

MLDA performed most experiments and analyzed data. FF, CN performed experiments. MSi and AG performed statistical analysis. AB, VM, FS and MSp provided essential technical services. LC, AC, PG and FLT provided clinical samples and expertise. RDM, MBa and MBi provided essential conceptual expertise. AZ supervised the project and wrote the manuscript. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by an Italian Association for Cancer Research (AIRC) Investigator Grant to A.Z. (AIRC IG 2017 Ref: 20744), with a partial contribution by La Sapienza University of Rome (grant RM11916B31436754 to P.G.).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to partecipate

CRC specimens were obtained from patients undergoing surgical resection upon informed consent and approval by La Sapienza-Policlinico Umberto I Ethical Committee (RIF.CE: 410717/10/2016). Peripheral blood samples were obtained from 6 patients with metastatic CRC at baseline before initiation of treatment at Policlinico Umberto I of Rome according to the protocol approved by Ethical Committee of Policlinico Umberto I of Rome (protocol n. 668/09, July 09, 2009; amended protocol 179/16, March 01, 2016). All animal procedures were performed according to the Italian National animal experimentation guidelines (D.L.116/92) upon approval of the experimental protocol by the Italian Ministry of Health’s Animal Experimentation Committee (DM n. 292/2015 PR 23/4/2015).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Maria Laura De Angelis, Email: marialaura.deangelis@iss.it.

Ruggero De Maria, Email: ruggerodemaria@gmail.com.

Ann Zeuner, Email: a.zeuner@iss.it.

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biller LH, Schrag D. Diagnosis and treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer: a review. JAMA. 2021;325(7):669–685. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.0106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cortes-Hernandez LE, Eslami SZ, Costa-Silva B, Alix-Panabieres C. Current applications and discoveries related to the membrane components of circulating tumor cells and extracellular vesicles. Cells. 2021;10(9):221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Keller L, Pantel K. Unravelling tumour heterogeneity by single-cell profiling of circulating tumour cells. Nat Rev Cancer. 2019;19(10):553–567. doi: 10.1038/s41568-019-0180-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alix-Panabières C, Pantel K. Liquid biopsy: from discovery to clinical application. Cancer Discovery. 2021;11(4):858–873. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baccelli I, Schneeweiss A, Riethdorf S, Stenzinger A, Schillert A, Vogel V, et al. Identification of a population of blood circulating tumor cells from breast cancer patients that initiates metastasis in a xenograft assay. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31(6):539–544. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamilton G, Burghuber O, Zeillinger R. Circulating tumor cells in small cell lung cancer: ex vivo expansion. Lung. 2015;193(3):451–452. doi: 10.1007/s00408-015-9725-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hodgkinson CL, Morrow CJ, Li Y, Metcalf RL, Rothwell DG, Trapani F, et al. Tumorigenicity and genetic profiling of circulating tumor cells in small-cell lung cancer. Nat Med. 2014;20(8):897–903. doi: 10.1038/nm.3600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jordan NV, Bardia A, Wittner BS, Benes C, Ligorio M, Zheng Y, et al. HER2 expression identifies dynamic functional states within circulating breast cancer cells. Nature. 2016;537(7618):102–106. doi: 10.1038/nature19328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu J, Fan T, Zhao Q, Zeng W, Zaslavsky E, Chen JJ, et al. Isolation of circulating epithelial and tumor progenitor cells with an invasive phenotype from breast cancer patients. Int J Cancer. 2010;126(3):669–683. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bobek V, Gurlich R, Eliasova P, Kolostova K. Circulating tumor cells in pancreatic cancer patients: enrichment and cultivation. World J Gastroenterol: WJG. 2014;20(45):17163. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i45.17163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bobek V, Matkowski R, Gürlich R, Grabowski K, Szelachowska J, Lischke R, et al. Cultivation of circulating tumor cells in esophageal cancer. Folia Histochem Cytobiol. 2014;52(3):171–177. doi: 10.5603/FHC.2014.0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cayrefourcq L, Mazard T, Joosse S, Solassol J, Ramos J, Assenat E, et al. Establishment and characterization of a cell line from human circulating colon cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2015;75(5):892–901. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-2613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cegan M, Kolostova K, Matkowski R, Broul M, Schraml J, Fiutowski M, et al. In vitro culturing of viable circulating tumor cells of urinary bladder cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7(10):7164. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kolostova K, Matkowski R, Gürlich R, Grabowski K, Soter K, Lischke R, et al. Detection and cultivation of circulating tumor cells in gastric cancer. Cytotechnology. 2016;68(4):1095–1102. doi: 10.1007/s10616-015-9866-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rossi E, Rugge M, Facchinetti A, Pizzi M, Nardo G, Barbieri V, et al. Retaining the long-survive capacity of circulating tumor cells (CTCs) followed by xeno-transplantation: not only from metastatic cancer of the breast but also of prostate cancer patients. Oncoscience. 2014;1(1):49. doi: 10.18632/oncoscience.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bobek V, Kacprzak G, Rzechonek A, Kolostova K. Detection and cultivation of circulating tumor cells in malignant pleural mesothelioma. Anticancer Res. 2014;34(5):2565–2569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang Y, Zhang X, Zhang J, Sun B, Zheng L, Li J, et al. Microfluidic chip for isolation of viable circulating tumor cells of hepatocellular carcinoma for their culture and drug sensitivity assay. Cancer Biol Ther. 2016;17(11):1177–1187. doi: 10.1080/15384047.2016.1235665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu M, Bardia A, Aceto N, Bersani F, Madden MW, Donaldson MC, et al. Cancer therapy. Ex vivo culture of circulating breast tumor cells for individualized testing of drug susceptibility. Science. 2014;345(6193):216–220. doi: 10.1126/science.1253533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang L, Ridgway LD, Wetzel MD, Ngo J, Yin W, Kumar D, et al. The identification and characterization of breast cancer CTCs competent for brain metastasis. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5(180):180ra48. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Praharaj PP, Bhutia SK, Nagrath S, Bitting RL, Deep G. Circulating tumor cell-derived organoids: current challenges and promises in medical research and precision medicine. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2018;1869(2):117–127. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2017.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tellez-Gabriel M, Cochonneau D, Cade M, Jubellin C, Heymann MF, Heymann D. Circulating tumor cell-derived pre-clinical models for personalized medicine. Cancers (Basel). 2018;11(1):19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Yang C, Xia BR, Jin WL, Lou G. Circulating tumor cells in precision oncology: clinical applications in liquid biopsy and 3D organoid model. Cancer Cell Int. 2019;19:341. doi: 10.1186/s12935-019-1067-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang Z, Shiratsuchi H, Lin J, Chen G, Reddy RM, Azizi E, et al. Expansion of CTCs from early stage lung cancer patients using a microfluidic co-culture model. Oncotarget. 2014;5(23):12383–12397. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khoo BL, Grenci G, Lim YB, Lee SC, Han J, Lim CT. Expansion of patient-derived circulating tumor cells from liquid biopsies using a CTC microfluidic culture device. Nat Protoc. 2018;13(1):34–58. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2017.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu X, Li J, Cadilha BL, Markota A, Voigt C, Huang Z, et al. Epithelial-type systemic breast carcinoma cells with a restricted mesenchymal transition are a major source of metastasis. Sci Adv. 2019;5(6):eaav4275. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aav4275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vishnoi M, Liu NH, Yin W, Boral D, Scamardo A, Hong D, et al. The identification of a TNBC liver metastasis gene signature by sequential CTC-xenograft modeling. Mol Oncol. 2019;13(9):1913–1926. doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.12533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Diamantopoulou Z, Castro-Giner F, Aceto N. Circulating tumor cells: ready for translation? J Exp Med. 2020;217(8):e20200356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Sato T, Stange DE, Ferrante M, Vries RG, Van Es JH, Van den Brink S, et al. Long-term expansion of epithelial organoids from human colon, adenoma, adenocarcinoma, and Barrett's epithelium. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(5):1762–1772. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hu Y, Smyth GK. ELDA: extreme limiting dilution analysis for comparing depleted and enriched populations in stem cell and other assays. J Immunol Methods. 2009;347(1-2):70–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baiocchi M, Biffoni M, Ricci-Vitiani L, Pilozzi E, De Maria R. New models for cancer research: human cancer stem cell xenografts. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2010;10(4):380–384. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Angelis ML, Francescangeli F, Zeuner A, M. B. In: Orthotopic xenografts of colorectal cancer stem cells. Elsevier, editor. Springer; 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Agnoletto C, Corrà F, Minotti L, Baldassari F, Crudele F, Cook WJJ, et al. Heterogeneity in circulating tumor cells: the relevance of the stem-cell subset. Cancers (Basel) 2019;11(4):483. doi: 10.3390/cancers11040483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scholch S, Garcia SA, Iwata N, Niemietz T, Betzler AM, Nanduri LK, et al. Circulating tumor cells exhibit stem cell characteristics in an orthotopic mouse model of colorectal cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7(19):27232–27242. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O’Brien CA, Pollett A, Gallinger S, Dick JE. A human colon cancer cell capable of initiating tumour growth in immunodeficient mice. Nature. 2007;445(7123):106–110. doi: 10.1038/nature05372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ricci-Vitiani L, Lombardi DG, Pilozzi E, Biffoni M, Todaro M, Peschle C, et al. Identification and expansion of human colon-cancer-initiating cells. Nature. 2007;445(7123):111–115. doi: 10.1038/nature05384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kreso A, Van Galen P, Pedley NM, Lima-Fernandes E, Frelin C, Davis T, et al. Self-renewal as a therapeutic target in human colorectal cancer. Nat Med. 2014;20(1):29–36. doi: 10.1038/nm.3418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Klameth L, Rath B, Hochmaier M, Moser D, Redl M, Mungenast F, et al. Small cell lung cancer: model of circulating tumor cell tumorospheres in chemoresistance. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):5337. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-05562-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mout L, van Dessel LF, Kraan J, de Jong AC, Neves RPL, Erkens-Schulze S, et al. Generating human prostate cancer organoids from leukapheresis enriched circulating tumour cells. Eur J Cancer. 2021;150:179–189. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2021.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pavese JM, Bergan RC. Circulating tumor cells exhibit a biologically aggressive cancer phenotype accompanied by selective resistance to chemotherapy. Cancer Lett. 2014;352(2):179–186. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ramesh V, Brabletz T, Ceppi P. Targeting EMT in cancer with repurposed metabolic inhibitors. Trends Cancer. 2020;6(11):942–950. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2020.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kanwar J, Samarasinghe R, Kanwar R. Natural therapeutics targeting Survivin. Biochemistry & Analytical. Biochemistry. 2012;1(6):1000e121. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Siegelin MD, Reuss DE, Habel A, Rami A, von Deimling A. Quercetin promotes degradation of survivin and thereby enhances death-receptor-mediated apoptosis in glioma cells. Neuro-Oncology. 2009;11(2):122–131. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2008-085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Voges Y, Michaelis M, Rothweiler F, Schaller T, Schneider C, Politt K, et al. Effects of YM155 on survivin levels and viability in neuroblastoma cells with acquired drug resistance. Cell Death Dis. 2016;7(10):e2410. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2016.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Le Gal K, Ibrahim MX, Wiel C, Sayin VI, Akula MK, Karlsson C, et al. Antioxidants can increase melanoma metastasis in mice. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(308):308re8. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad3740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Piskounova E, Agathocleous M, Murphy MM, Hu Z, Huddlestun SE, Zhao Z, et al. Oxidative stress inhibits distant metastasis by human melanoma cells. Nature. 2015;527(7577):186–191. doi: 10.1038/nature15726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gao D, Vela I, Sboner A, Iaquinta PJ, Karthaus WR, Gopalan A, et al. Organoid cultures derived from patients with advanced prostate cancer. 2014;159(1):176–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Chen H, Gotimer K, De Souza C, Tepper CG, Karnezis AN, Leiserowitz GS, et al. Short-term organoid culture for drug sensitivity testing of high-grade serous carcinoma. 2020;157(3):783–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Kopper O, De Witte CJ, Lõhmussaar K, Valle-Inclan JE, Hami N, Kester L, et al. An organoid platform for ovarian cancer captures intra-and interpatient heterogeneity. 2019;25(5):838–49. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Lin K-C, Ting L-L, Chang C-L, Lu L-S, Lee H-L, Hsu F-C, et al. Ex vivo expanded circulating tumor cells for clinical anti-cancer drug prediction in patients with head and neck cancer. 2021;13(23):6076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Yang L, Yang S, Li X, Li B, Li Y, Zhang X, et al. Tumor organoids: from inception to future in cancer research. Cancer Lett. 2019;454:120–133. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hartwell KA, Muir B, Reinhardt F, Carpenter AE, Sgroi DC, Weinberg RA. The Spemann organizer gene, Goosecoid, promotes tumor metastasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(50):18969–18974. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608636103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xue TC, Ge NL, Zhang L, Cui JF, Chen RX, You Y, et al. Goosecoid promotes the metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma by modulating the epithelial-mesenchymal transition. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e109695. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ischenko I, Petrenko O, Hayman MJ Analysis of the tumor-initiating and metastatic capacity of PDX1-positive cells from the adult pancreas. PNAS. 2014;111(9):3466–3471. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319911111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Roy N, Takeuchi KK, Ruggeri JM, Bailey P, Chang D, Li J, et al. PDX1 dynamically regulates pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma initiation and maintenance. Genes Dev. 2016;30(24):2669–2683. doi: 10.1101/gad.291021.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chemi F, Mohan S, Guevara T, Clipson A, Rothwell DG, Dive C. Early dissemination of circulating tumor cells: biological and clinical insights. Front Oncol. 2021;11:672195. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.672195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1:. Supplementary Methods.

Additional file 2: Table S1. Information of CRC patients used to isolate CTCs. NA: Not Available; CT: Chemotherapy.

Additional file 3: Table S2. List of compounds used in the screening: drug name, targets Selleckchem catalogue number and doses are reported. Anti-cancer compounds (sheet 1) have been used at a 200 nM concentration, whereas low toxicity compounds (sheet 2) have been used at the indicated doses in order to identify the LD50 value reported in Fig. 5E.

Additional file 4: Table S3. List of proteins and raw endpoint values relative to the Proteome Profiler Arrays shown in Fig. 6A.

Additional file 5: Figure S1. MSI status/mutational profile of patient’s CRC and xenograft validation. (A) WES analysis was performed on the surgical sample used for organoid generation, allowing the estimation of mutation rates (hypermutated: more than 10 mutations per Megabase). High-grade microsatellite instability (MSI) was also detected. Both Non-Silent (blue) and Silent (orange) somatic variants are reported. (B) OncoPrint showing functionally relevant intragenic lesions in recurrently mutated genes. Half boxes and full boxes represent heterozygous and homozygous variants, respectively; colors are used to specify the type of mutation. Stars indicate germline mutations; multiple hits affecting the same gene are indicated by numbers. (C) Hematoxylin/Eosin staining of the primary patient’s tumor and of PDOs-derived subcutaneous tumor xenograft showing comparable histological structure. Magnification 20x.

Additional file 6: Figure S2. Growth and metastatization of orthotopic tumor xenografts recorded by bioimaging. Representative images of LUC-expressing PDOs orthotopically injected into the colon wall of NSG mice and monitored by bioluminescent imaging (IVIS imaging system) at different time points.

Additional file 7: Figure S3. CTCDOs phenotypic characterization. (A) Flow cytometry of purified CTCDOs stained for human EpCAM and mouse CD45 expression. (B) Representative flow cytometry plots performed on XDOs and CTCDOs for the expression of: EpCAM, VIM, CK20, CD44v6 shown in Fig. 3C. (C) Representative flow cytometry plots performed on XDOs and CTCDOs for the expression of CD44v6/EpCAM and CD44v6/Vimentin Fig. 3D. (D) Representative confocal images of CD45-positive (hematopoietic) cells present on ScreenCell® filters. Cells were stained with CD45/DAB (appearing as the dark staining in the differential interference contrast/DIC brightfield), CD44v6 (green), EpCAM (yellow) and CK20 (red). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Magnification 60x, 5x zoom, bar 10 μM.

Additional file 8: Figure S4. Linear regression of the effect of low toxicity compounds on CTCDOs and XDOs. Schematic representation trough linear regression of low toxicity compounds described in Fig. 5D and used at different indicated doses specified in Additional file 3: Table S2 (upper panel); detail of endpoints contained in the red square (lower panel).

Additional file 9: Figure S5. Selected protein validations on CTCDOs, XDOs, PDOs and CTCDOs/XDOs-derived xenografts. Left: immunoblot analysis of E-Cadherin, Vimentin, p21, P53, PON2, pHSP27 (Ser78), HIF-1α, Sirt2, Bcl-2, MMP2, Cathepsin D and Survivin on whole lysates of CTCDOs, XDOs, PDOs and CTCDOs/XDOs-derived xenografts (reported as CTCDOs xeno and XDOs xeno). β-actin and GAPDH were used as a loading control. Right: quantification of immunoblot experiments.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.