Abstract

Background:

An association between chronic infectious diseases and development of dementia has been suspected for decades, based on the finding of pathogens in postmortem brain tissue and on serological evidence. However, questions remain regarding confounders, reverse causality, and how accurate, reproducible and generalizable those findings are.

Objective:

Investigate whether exposure to Herpes simplex (manifested as herpes labialis), Chlamydophila pneumoniae (C. pneumoniae), Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori), and cytomegalovirus (CMV) modifies the risk of dementia in a populational cohort.

Methods:

Questionnaires regarding incidence of herpes infections were administered to Original Framingham Study participants (n = 2,632). Serologies for C. pneumoniae, H. pylori, and CMV were obtained in Original (n = 2,351) and Offspring cohort (n = 3,687) participants. Participants are under continuous dementia surveillance. Brain MRI and neuropsychological batteries were administered to Offspring participants from 1999–2005. The association between each infection and incident dementia was tested with Cox models. Linear models were used to investigate associations between MRI or neuropsychological parameters and serologies.

Results:

There was no association between infection serologies and dementia incidence, total brain volume, and white matter hyperintensities. Herpes labialis was associated with reduced 10-year dementia risk (HR 0.66, CI 0.46–0.97), but not for the duration of follow-up. H. pylori antibodies were associated with worse global cognition (β −0.14, CI −0.22, −0,05).

Conclusion:

We found no association between measures of chronic infection and incident dementia, except for a reduction in 10-year dementia risk for patients with herpes labialis. This unexpected result requires confirmation and further characterization, concerning antiviral treatment effects and capture of episodes.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, Framingham, herpes labialis, viral infections

INTRODUCTION

The possibility that infectious agents play an important role in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) was first raised decades ago, with the observation of the correspondence between the areas typically affected in herpes encephalitis (limbic regions, especially the hippocampal formation and amygdala) and in AD [1], and the direct finding of viral DNA in patients brains [2]. It never gained wide acceptance, though, due to questions regarding the reproducibility of the detection of pathogens in diseased brains, the difficulty of knowing whether it was a cause or consequence of the disease, and their presence in the brains of unimpaired individuals [3], which at the very least suggests that factors such as genetic variation and timing of microbial exposure, in addition to the organisms’ presence, would be necessary for them to play a role in the risk of developing dementia.

Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV1) is a neurotropic human virus with an estimated prevalence of 90 % in older adults [4]. Multiple studies have investigated associations between HSV1 and AD. Steel’s meta-analysis of 18 studies [5], 13 of which involved autopsy, suggests an increased risk of AD when HSV1 is present (OR 1.38). The risk further increased when HSV1 DNA and an Apolipoprotein E ε4 allele (AP0E4) were present (OR 2.71), suggesting an interaction between viral exposure and genetic risk for AD. In contrast to the meta-analysis, individual studies assessing serological diagnosis of HSV1 and clinical AD are somewhat conflicting. A French cohort study found that reactivated, but not chronic, HSV infection, regardless of APOE4 status, increased risk of AD [6]. A Swedish cohort replicated those findings in 2015 [7]. In contrast, a nested case control study by Lövheim [8] found that chronic HSV1 infection, when detected > 6.6 years before AD diagnosis, portended increased risk (OR 2.25). This was extended by a study examining HSV seropositive individuals aged 65 or older, which found that APOE4 status and age mediated lower episodic memory scores in a cross-section analysis, and their decline in a longitudinal analysis [9]. Supporting the reactivation hypothesis, Tzeng [10], utilizing the Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database, showed that patients seen at least 3 times in a year (a relatively high frequency, suggesting severe infection) for any symptomatic HSV (n = 8,362) had an adjusted hazard ratio (HR) of 2.564 for the development of dementia, which was reduced to a HR of 0.092 if those infections had been treated with antivirals, in particular for a prolonged (>7 4 weeks) time. More recently, a large Swedish cohort study [11], using national registries with data on HSV diagnosis, antiviral prescription, and diagnosis of dementia, with approximately 5 years of follow-up, supported those findings: the relative risk of dementia was 0.66 with antiviral treatment, compared to herpes diagnosis without treatment. Individuals treated for herpes had a lower risk of dementia even when compared to controls without a herpes diagnosis. There was no serology data, and no analysis based on what body part was involved by the herpes flare.

Evidence from a different perspective was shown by Wozniak [12], who detected HSV DNA in amyloid plaques in brains of patients with AD, and complemented by Eimer [13], who described the binding of Aβ oligomers to herpesvirus 1, 6A and B surface glycoproteins and subsequent entrapping of virus particles in mouse and 3-D human cells models.

C. pneumoniae has also been postulated to have a possible relationship with incidence of AD, also based on the direct finding of the pathogen in diseased brains [14]. This pathogen is an obligate intracellular Gram-negative bacterium, with prevalence greater than 50% throughout lifetime, and with most infections being asymptomatic or mild. Small autopsy studies have detected bacterial DNA in 74 to 89% of AD brains, versus 5–11% in controls [15], while other studies were unable to detect any bacterial DNA in either cases or controls [16, 17]. C. pneumoniae DNA was found in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of 25/57 AD, 5/47 controls, and 7/21 patients with vascular dementia (VaD). There was no correlation between DNA detection and levels of amyloid-β or tau [18]. Serological studies are heterogeneous: A case-control study found no difference in IgG or IgA between 61 AD (36%) and 32 controls (25%); however, rates were substantially higher in individuals with VaD (61% of 31 cases) [19]. In contrast, another study did not find a difference in IgG or IgA in 28 VaD versus 24 controls [20]. No associations were found between C. pneumoniae antibodies (and HSV, H. pylori, CMV) and cognitive decline [21] in a cohort of 426 patients (186 completers, follow-up of 20 years). Limitations include controls comprising only 3% of the sample, no cognitive monitoring for 14 years, and large attrition rates. Dementia incidence was not measured.

As for CMV, it is also a herpes virus responsible for chronic infection, mostly asymptomatic, with prevalence in older adults usually greater than 60% [22], and with purported connections to immunosenescence [23]. An autopsy study from 2002 detected CMV DNA in 14/15 of VaD patients’ brains versus 34% of controls [24]. Lurain [25] reported increased CMV IgG in the CSF (11/44) in AD and increased IFNγ levels in CMV+AD patients (47/58). Regarding serological studies, Barnes [26] followed 849 subjects: IgG+ had a RR of 2.15 of AD, and faster cognitive decline. Lövheim [27], however, found that IgG antibodies 9.6 years before diagnosis did not increase risk of AD in a nested case-control study with 720 participants (cognition not tracked directly). When HSV was present, the OR was 5.66. Torniainen [28] found no association between CMV or EBV titers and development of dementia in 7,112 volunteers (4,620 reassessed after 11 years). Study limitations are the large interval between assessments, differential attrition, and indirect diagnosis of dementia.

Concerning H. pylori, a Gram-negative rod originally isolated in 1982, prevalence varies from 14 to greater than 90 %, possibly due to different social or hygiene factors, genetic predisposition, antimicrobial use, smoking, and environmental exposures [29]. There are no reports of direct brain invasion, and possible links with dementia are presumed to be related to an increase in inflammation [30]. Most prospective studies do support an association with dementia, although with some heterogeneity. Roubaud Baudron [31] reported a HR of 1.46 on 568 participants of a cohort, followed by 20 years. Itskovitch’s [32] meta-analysis reported an OR of 1.71. Beydoun [33] showed an adjusted HR of 1.44, in men of higher socio-economic status. Huang [34] detected an increased risk of developing mainly VaD, examining a Health Insurance database. ICD codes were used, which presents a bias toward severe H. pylori infections and limits dementia diagnostic accuracy. Fani [35], however, following 529 participants of the Rotterdam cohort for 13.3 years, found no difference in risk of dementia or AD. Cohort participants were 10 years younger than in previous cohorts. Additionally, lower virulence strains in the Netherlands may have contributed to the null findings.

The Framingham Heart Study is a population-based cohort that has serology and questionnaire data on those infectious diseases. Additionally, frequent cognitive assessments have been performed over several decades. Those resources would allow reducing some of the limitations in the medical literature, such as the use convenience samples, survivor bias, lack of in-person screening, and excessive attrition; and result in increased generalizability of its conclusions. A significant contribution to the elucidation of the question of whether infection by those organisms increases risk of AD would therefore be anticipated.

Our main goal was to investigate the association between the presence of chronic infections, assessed by responses to questionnaires and serological tests to H. pylori, C. pneumoniae, and CMV, and incident dementia as well as brain MRI and neuropsychological measures, in the Original and Offspring Cohorts of the Framingham Heart Study.

METHODS

Study sample

The Framingham Heart Study is a community-based, longitudinal cohort study that was initiated in 1948. The original cohort comprised 5,209 residents of Framingham, Massachusetts. These participants have undergone up to 32 examinations, performed every 2 years, which have involved detailed history taking by a physician, a physical examination, and laboratory testing. The Offspring cohort was started in 1971, and recruited 5,124 participants, that have undergone up to nine examinations.

Analysis with incident dementia as the outcome was restricted to participants that were at least 60 years old at the start of follow-up, who were free of dementia, had infection data (serologies or questionnaire answers), and who had follow-up for dementia. Analyses with cognitive measures as the outcome were restricted to participants in the Offspring cohort who were free of dementia and stroke at the time of cognitive examination and who had information on education and infection. Analyses with MRI measures as the outcome were restricted to patients in the Offspring cohort who were free of dementia, stroke, and other neurological disorders and who had infection data. All participants have provided written informed consent. Study protocols and consent forms were approved by the institutional review board at the Boston University Medical Center.

Materials and methods

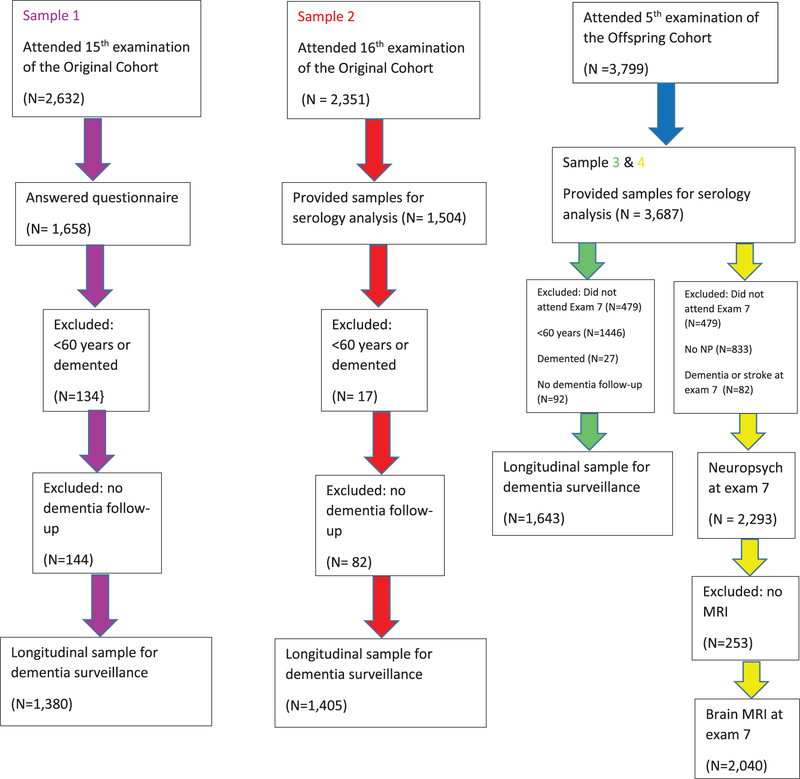

Figure 1 describes the patient flow in the Original and Offspring Cohorts.

Fig. 1.

Participant flow chart.

H. pylori, C. pneumoniae, and CMV serology

Blood samples were collected during the 16th examination (1979–1982) of the original cohort, and 5th examination (1991–5) of the Offspring cohort. Serum was frozen and stored at −20°C. Specimens were thawed and aliquoted into cryogenic vials in 1997 and shipped on dry ice to the Medical Reference Laboratory in Cypress, California for testing. Commercially available IgG antibody tests for H. pylori, C. pneumoniae, and CMV were performed.

H. pylori IgG

Sera were diluted in sample buffer, and 0.1 ml was added to individual microtiter wells (Enteric Products International kit). After 20 min at room temperature, plates were washed three times, and 0.1 ml of horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-human IgG was added. After 20 min at room temperature the plates were washed. Thrombo broth was added, and after 10 min, 1N sulfuric acid was added to stop the reaction. Absorbance was read at 450 nm. Absorbance values were converted to ELISA values using a 3-point standard curve. As recommended by the manufacturer, an ELISA value of 2.2 was considered positive.

C. pneumoniae IgG

Slides containing C. pneumoniae elementary bodies attached to the glass were used. There were 12 wells per slide. Sera were diluted 1:16, 1:64, and 1:256 in sample buffer. 0.025 ml of each dilution was added to slide wells. After 1 h at 37°C, the slides were washed, dried, and then treated with FITC-conjugated goat anti-human IgG. After 30 min at 37°C, slides were washed and dried as before. Glycerol mounting sodium was added, along with a coverslip. Slides were examined using a fluorescent microscope at 400 x. The presence of antibody was indicated by fluorescence of elementary bodies. Titers of 1:128 or greater were considered positive as per laboratory protocol.

CMV IgG

Sera were diluted 1:21 in sample buffer, and 0.1 ml was added to individual microtiter wells (Zeus Scientific kit). After 20 min at room temperature, plates were washed three times, and 0.1 ml of horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-human IgG was added. After 20 min at room temperature, the plates were washed as before, and 1N sulfuric acid was added to stop the reaction. Absorbance was read at 450 nm. An index value was calculated by dividing the patient absorbance value by a cutoff absorbance value (determined by multiplying the low positive control absorbance value by a kit-specific conversion factor). Index values 3.52 were considered positive, as recommended by the manufacturer.

Reproducibility was tested by including blinded duplicate specimens (2%), as measured by betweensubject variance as a percentage of total variance. Reproducibility estimates were 98% for H. pylori and CMV, 69% for C. pneumoniae IgG. Seropositivity was defined as ELISA value ≥2.2 for H. pylori IgG, C. pneumoniae IgG titer ≥1:128, and CMV index value ≥3.52.

APOE genotyping

Leukocyte DNA was extracted from 5–10 ml of whole blood. A 244-bp sequence of the APOE gene, including the two polymorphic sites, was amplified by polymerase chain reaction in a DNA Thermal Cycler (PTC-100, MJ Research, Watertown, MA) using oligonucleotide primers F4 and F6, according to the method described by Lahoz et al. [36].

Clinical herpes history questionnaire

Individuals from the original cohort were asked [37] on the 15th examination (1977–1979), for history of ever having had herpes labialis (cold sores or fever blisters), varicella (chickenpox), herpes zoster (shingles). Only “yes” responses were counted as positive; “no” and “maybe” were counted as negative, and “don’t know” was not counted. Less than 3% of the answers were “maybe” or “don’t know”, except for varicella (30%).

Surveillance for AD and other dementias

Surveillance methods have been published previously [38]. Briefly, cognitive status has been monitored in the original cohort since 1975, when comprehensive neuropsychological (NP) testing was performed. Since 1981, participants in this cohort have been assessed at each examination with the use of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE); participants are flagged for further cognitive screening if they have scores below education-based cutoffs, or if their scores have declined by 3 points since the previous exam, or 5 points from their highest ever score. Participants are also flagged if subjective cognitive decline is reported by the participant or a family member or by clinic staff at the time of clinic examination or during annual health-status updates. Participants who are identified as having possible cognitive impairment based on these screening assessments are invited to undergo a thorough neuropsychological examination and to be examined by a neurologist. Evidence of cognitive decline triggers annual or biennial cognitive assessment and/or neurology examination. Participants whose neurology examination indicates at least mild dementia undergo dementia review by a panel including at least one neurologist and one neuropsychologist.

The panel uses data from previously performed serial neurologic and neuropsychological assessments, telephone interviews with caregivers, medical records, neuroimaging studies, and, when applicable and available, autopsies.

MRI brain measures

2,063 offspring cohort participants who attended Examination Cycle 7 also agreed to have a brain MRI scan from 1999 to 2005. MRI acquisition, measurement techniques, and interrater reliability have previously been described [39]. In short, the majority of subjects were imaged on a Siemens Magnetom 1T field strength magnetic resonance machine using a T2-weighted double spin-echo coronal imaging sequence of 4 mm contiguous slices from nasion to occiput with a repetition time (TR) of 2420 ms, echo time (TE) of TE1 20/TE290 ms; echo train length 8 ms; field of view (FOV) 22 cm and an acquisition matrix of 182×256 interpolated to a 256×256 with one excitation. MRI measures assessed total cerebral brain volume, white matter hyperintensities (WMH), and hippocampal volume. Quantification of regional brain and WMH began with image segmentation to define brain matter from CSF. A difference image was created by the subtraction of the second echo image from the first echo image. Image intensity non-uniformities were removed, and the corrected image was modeled as a mixture of two Gaussian probability functions with the segmentation threshold determined at the minimum probability between these two distributions. After image segmentation, the operator returned to the image for measurement of lobar brain volumes. To increase the reliability of the lobar analyses, the images were rigidly rotated into anatomic standard space, using common cerebral landmarks: the interhemispheric fissure in the axial and coronal planes and a line joining the anterior and posterior commissures in the sagittal plane. Segmented brain-CSF images were rotated separately from the original image to preserve measurement precision. For segmentation of WMH from brain matter, the first and second echo images were summed after removal of CSF and correction of image intensity non-uniformities A repeat Gaussian distribution was fitted to the summed image data and a segmentation threshold for WMH was a priori determined as 3.5 S.D. in pixel intensity above the mean of the fitted distribution of brain parenchyma. Morphometric erosion of two exterior image pixels was applied to the image before modeling to remove the effects of partial volume CSF pixels on WMH determination.

Neuropsychological battery

The battery was applied at the seventh examination of the Offspring Cohort, and consisted of tests of verbal and visual memory, verbal learning, attention/concentration, tracking and mental flexibility. Verbal memory was tested with the Wechsler Memory Scale (WMS) tests of Logical Memory Immediate Recall and Logical Memory Delayed Recall. Visual memory was assessed with the WMS Visual Reproductions Immediate Recall and Delayed Recall tests. Participants were also tested with the WMS Paired Associates Immediate and Delayed Recall conditions, the similarities test from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, the Visual organization test and by the Halstad-Reitan Trails A and B tests. A global measure of cognitive decline derived from principal component analysis was also calculated [40].

Statistical analysis

We used Cox proportional Hazards models to test the association between each infection (based on questionnaire response and positive serology to CMV, C. pneumoniae, and H. pylori) and onset of dementia at 10 years, and after up to 35 years of follow-up among the Original Cohort. Participants were censored at death, loss to follow-up or incident dementia. Participants who were alive without developing dementia were censored at the last follow-up.

Each infection predictor was analyzed in a separate Cox proportional hazards model, adjusting for entry age, sex, and education.

We used multiple linear regression models to test the association between each infection and MRI or NP measurements. Models with NP outcomes were adjusted for age, sex, education, and time between infection and NP measurement. Models with MRI outcomes were adjusted for age, age-squared, sex, and time between infection and MRI measurement. MRI measures were analyzed as percent of total cranial volume. WMH was then log transformed to normalize its distribution. Trails B - A was log transformed to normalize its distribution and then re-signed to be consistent with the other cognitive measures, with higher values indicating better performance, i.e. -log[TrailsB-TrailsA+2].

Effect modification by APOE4 status was assessed in all models.

RESULTS

History of herpes infections and dementia

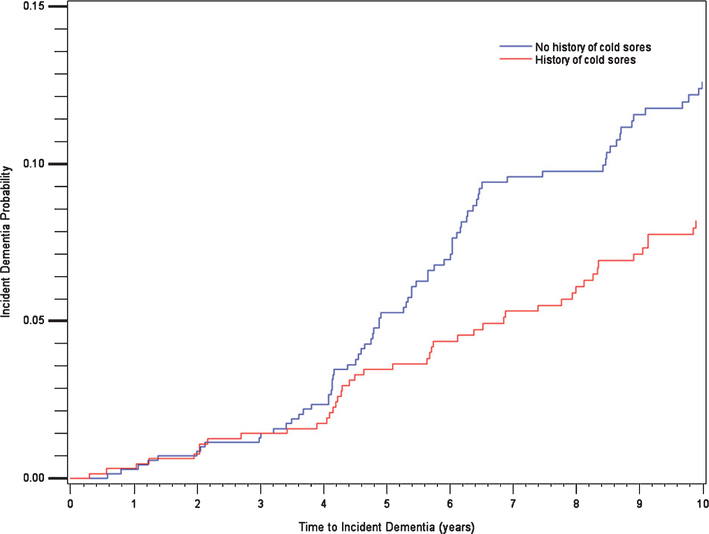

Up to 1,619 individuals in the original cohort provided questionnaire responses (average age 69, SD 7, 58% women). 641 out of 1,350 individuals (48%) from the original cohort reported a history of herpes labialis (Table 1). 119 of 1,350 developed dementia over the next 10 years, with a significantly reduced risk by 34% (Table 2A). A Kaplan-Meyer curve (Fig. 2) showed that the risk curves start to diverge after the third year of follow-up. Logistic regressions were performed as sensitivity analyses (not shown), and showed no significant associations, suggesting the importance of accounting differently for patients that completed follow-up, versus those that dropped out or died. When follow-up went beyond 10 years, there was no difference in the risk of dementia between individuals with and without a history of herpes labialis.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study populations

| Sample 1 (n = 1,380) | Sample 2 (n = 1,405) | Sample 3 (n = 1,643) | Sample 4 (n = 2,040) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Age (y), Mean (SD) | 68 (7) | 70 (7) | 69 (6) | 61 (9) |

| Men, N (%) | 568 (41) | 565 (40) | 778 (47) | 952 (47) |

| Education (y) | ||||

| Up to HS | 1017 (75) | 1012 (73) | 670 (41) | 633 (31) |

| Some college | 212 (15) | 222 (16) | 469 (29) | 608 (30) |

| College degree | 135 (10) | 157 (11) | 487 (30) | 799 (39) |

| APOE4, at least one allele, N (%) | 139 (20) | 153 (20) | 353 (22) | 438 (22) |

| BMI (kg/m2), Mean (SD) | 27 (4) | 27 (5) | 28 (5) | 28 (5) |

| Hypertension, N (%) | 777 (57) | 889 (63) | 966 (59) | 844 (41) |

| Diabetes mellitus, N (%) | 91 (7) | 96 (7) | 239 (15) | 204 (10) |

| Smoking, N (%) | 291 (22) | NA | 144 (9) | 242 (12) |

| History of cold sores, N (%) | 641 (48) | NA | NA | NA |

| History of shingles/herpes zoster, N (%) | 145 (11) | NA | NA | NA |

| History of chicken pox, N (%) | 556 (50) | NA | NA | NA |

| C. pneumoniae IgG, N (%) | NA | 478 (34) | 662 (40) | 831 (41) |

| H. pylori IgG, N (%) | NA | 854 (61) | 484 (30) | 416 (20) |

| CMV IgG, N (%) | NA | 972 (69) | 696 (42) | 681 (33) |

SD, standard deviation; NA, not available; BMI, body mass index.

Table 2A.

Association between infection and time to dementia (Sample 1)

| Infection | HR (95%) CI for incident dementia (Events/Person-years of follow-up) | HR (95%) CI for incident dementia (restricted to 10 years of follow-up) (Events/Person-years of follow-up) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Ever had cold sores | 0.97 (0.79–1.18) (410/19389) | 0.67 (0.46–0.98) (116/11105) |

| Ever had shingles or herpes zoster | 0.93 (0.69–1.25) (410/19474) | 0.96 (0.57–1.60) (115/11158) |

| Ever had chicken pox | 0.84 (0.67–1.06) (331/15887) | 0.90 (0.59–1.37) (93/9089) |

Adjusted for age, sex, and education.

Fig. 2.

Kaplan Meier curve for association between cold sores and incident dementia (10 year cutoff).

The prevalences of herpes zoster and chicken pox were 11 % and 50%, respectively. There was no modification in the risk of dementia at 10 years or for the entire follow-up in connection with history of those infections. There was no significant interaction by APOE in associations between infection and dementia.

Serologies and dementia

Serologies were available from 1,405 persons in the original cohort, and 1,643 individuals in the offspring cohort. Average ages were 70 (SD 6), and 69 (SD 7), respectively.

34% of the original cohort individuals tested had positive C. pneumonia IgG. 61% had H. pylori IgG and 69% had CMV IgG (Table 2B). 430 out of 1,405 individuals developed dementia during follow-up; 130 when it was restricted to 10 years. There was no association between any positive serology and risk of dementia.

Table 2B.

Association between serology and time to dementia – Original Cohort (Sample 2)

| Infection | HR (95%) CI for incident dementia (Events/Person-years of follow-up = 428/18516) | HR (95%) CI for incident dementia (restricted to 10 years of follow-up) (Events/Person-years of follow-up = 128/11001) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Chlamydia IgG | 0.86 (0.69–1.06) | 0.93 (0.64–1.37) |

| H. pylori | 0.99 (0.80–1.21) | 1.08 (0.74–1.56) |

| CMV | 1.05 (0.85–1.31) | 1.15 (0.75–1.78) |

Adjusted for age, sex, and education.

In the offspring cohort, 40% had positive C. pneumoniae IgG. 32% had H. pylori IgG and 42% had CMV IgG (Table 2C). 262 individuals out of 1,643 developed dementia during follow-up, 143 when follow-up was restricted to 10 years. Positive serologies did not modify the risk of dementia.

Table 2C.

Association between serology and time to dementia – Offspring Cohort (Sample 3)

| Infection | HR (95%) CI for incident dementia (Events/Person-years of follow-up = 259/19277) | HR (95%) CI for incident dementia (restricted to 10 years of follow-up) (Events/Person-years of follow-up = 141/13583) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Chlamydia IgG | 0.90 (0.70–1.16) | 1.28 (0.90–1.82) |

| H. pylori | 1.01 (0.78–1.32) | 0.91 (0.63–1.30) |

| CMV | 1.12 (0.87–1.45) | 1.11 (0.79–1.56) |

Adjusted for age, sex, and education.

Serologies and MRI measures

In the offspring cohort, there was no association between positive serologies for C. pneumonia, H. pylori, and CMV and total brain volume or WMH on brain MRI (Table 3A). CMV IgG positivity was associated with 0.01% greater hippocampal volumes. Individuals with positive CMV IgG and no APOE4 allele had greater total brain volumes than CMV IgG+ individuals with that allele (Table 3B). APOE4 interactions were not detected in any of the other conditions investigated.

Table 3A.

Association between infection and MRI measures: Offspring Cohort (Sample 4)

| Infection | β (95% CI) for association with: |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total brain volume (%) | Hippocampal volume (%) | White matter hyperintensity (%)* | |

|

| |||

| Chlamydia IgG | −0.03 (−0.21, 0.14) | −0.001 (−0.005, 0.004) | 0.02 (−0.06, 0.10) |

| H. pylori | 0.12 (−0.10, 0.34) | −0.002 (−0.01, 0.004) | −0.02 (−0.12, 0.08) |

| CMV | 0.18 (−0.01, 0.36) | 0.01 (0.002, 0.01) | 0.03 (−0.05, 0.12) |

log transformed for normality.

Table 3B.

Effect modification by APOE4 in the association between infection and MRI measures: Offspring Cohort (Sample 4)

| Infection | APOE4 | β (95% CI) for association with: Total brain volume (%) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| H. pylori | Yes | −0.36 (−0.82, 0.09) |

| No | 0.21 (−0.04, 0.27) | |

| CMV | Yes | −0.23 (−0.62, 0.16) |

| No | 0.30 (0.09, 0.52) | |

Only associations with interaction p-value<0.10 are presented.

Serologies and neuropsychological measures

H. pylori positivity was associated with worse global cognition. There was no effect on logical memory, nor on Trail making B minus A performance (Table 4). C. pneumonia and CMV were not associated with differences in those cognitive measures, and there was no difference based on APOE4 positivity in connection with those serologies either.

Table 4.

Association between infection and neuropsych testing measures: Offspring Cohort (Sample 4)

| Infection | β (95% CI) for association with: |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Trails B-A* | Logical memories delayed | PC1 (Global cognition) | |

|

| |||

| Chlamydia IgG | 0.01 (−0.01, 0.03) | −0.18 (−0.46, 0.10) | −0.04 (−0.10, 0.03) |

| H. pylori | −0.01 (−0.03, 0.01) | −0.14 (−0.49, 0.21) | −0.14 (−0.22, −0.05) |

| CMV | −0.01 (−0.03, 0.01) | −0.09 (−0.39, 0.21) | −0.01 (−0.08, 0.07) |

Adjusting for entry age, sex, time between infection and NP measurement, and education.

log transformed for normality.

DISCUSSION

Our study found no correlation between positive serology for H. pylori, C. pneumoniae, and CMV and incident dementia risk. The main association detected in our study was of a decreased 10-year risk of developing dementia in individuals with history of herpes labialis, compared to those without such history. This was unexpected, given multiple reports [5–9] suggesting either increased risk of dementia in people with positive herpes serologies or no difference compared to controls. The increase in dementia risk was not verified when the entire duration of follow-up was considered. We believe there are several factors that could help reconcile those findings, and avenues to fully elucidate their meaning:

Patients with clinical history of herpes labialis are more likely to have used antiviral medications, and those could offer protective effects, as suggested by Tzeng [10] and Lopatko Lindman [11]. Antiviral medications are used as a response to clinical manifestations of herpes, and not to a positive serology, which is the only factor assessed by most of the prospective studies, albeit IgM can provide a serological measure of reactivation, and was reported in Letenneur’s [6] and Lövheim’s [7] studies. Acyclovir had not been licensed at the time of the questionnaires, but could have been used by our patients on outbreaks after 1982, though unfortunately we did not collect information on medication use, nor on any more herpes outbreaks after the questionnaire was administered. An antiviral medication effect, nevertheless, still seems a feasible explanation for our findings regarding reduction in the risk of dementia, which would align well with previous reports [10, 11]. Additionally, peppermint [41], propolis [42], and other over-the-counter remedies have been shown to have antiherpetic activity, but there is little to no evidence that such treatments have ever been used widely enough to potentially impact our results.

-

Positive HSV serologies and history of herpes labialis are significantly dissociated. In the small subset of our original cohort population which was tested for HSV serology, for example, 75/153 (49%) of individuals with no history of any symptomatic herpes had an HSV-1 titer of at least 1:32. 53/165 (32%) of patients with such history had titers lower than 1:32 [37] (Supplementary Table 1). Thus, rather than functioning as a surrogate marker for HSV infection, the clinical history of having herpes labialis seems to reflect a specific pattern of interactions between virus and host, possibly modulated by genetic polymorphisms such as in the C21orf91 gene, which is related to recurrent and severe disease [43]. The implication is that documenting clinical infections adds a dimension not adequately captured with serological markers.

It is also known that seropositive, asymptomatic individuals have CD 8 + T lymphocytes with different patterns of surface markers, and respond against different epitopes compared to CD 8 + lymphocytes of seropositive individuals with recurrent disease, a fact that is being used in attempts to manufacture safe and effective vaccines [44]. It is conceivable that differences in lymphocytic responsiveness profile could also modulate dementia risk, though there are no studies directly investigating this mechanism. An alternative hypothesis would be that localized clinical manifestations of herpes infection, such as herpes labialis, could be protective against disease manifestations that would require distant virus propagation through second and third-order neurons. The mechanism for that is thought to be related to adaptive immune surveillance suppressing distant infection, while in the more proximal site a different state of the viral cycle, not as effectively controlled by the adaptive immune response, has already been established. This hypothesis is based on the findings of animal studies by Poccardi et al. [45], that accounted for the fact that herpes keratitis reoccurs unilaterally, in spite of viral proliferation in the trigeminal ganglia bilaterally. Interestingly, in a report from Italy [46] with 141 patients with herpes genitalis and 70 controls, HSV-1 antibodies were found in 34.7% of cases and 67% of controls, and history of recurrent herpes labialis in 4% of cases and 31% of controls (all significant differences). A protective effect of herpes labialis against the development of herpes genitalis was deemed a possible explanation.

HSV serology has its own significant limitations: it does not capture individuals that have had contact with the virus, but developed a lymphocyte T-based immunity, which can be detected by lymphoproliferative or cytotoxic T lymphocyte assays [47]. Those individuals tend to develop immunity against immediate early viral proteins, as opposed to virion proteins. Possibly due to this, a study collecting saliva and tears of 50 asymptomatic individuals (13 seronegative) daily, for 30 days, detected HSV DNA in 49 of them at least once, including 12 of the 13 seronegative [48], with the overall percentage of positive mouth swabs being 37.5%. The very high prevalence of herpes viral shedding in both asymptomatic and seronegative individuals suggest that absence of herpes manifestations does not equal suppression of viral replication.

The possession of an APOE4 allele has been suggested to be a risk factor for herpes labialis [49, 50]. In our cohort, APOE4 status did not modify risk of developing dementia in patients with cold sores.

As for the lack of significant associations between herpes labialis and incidence of dementia beyond 10 years, the extraordinarily long duration of follow-up in the original cohort, resulting in increasing competition with other causes of dementia, or in greater remoteness of the episodes of herpes labialis, which is reported to be less frequent with increased age [43], may account for it. The last examination of the Original Cohort happened from 2012–2014, 35 years after the infection questionnaire was administered. There is a risk of exposure misclassification with such long follow-up, in that we have no data on whether cohort participants in the group without history of herpes labialis subsequently developed the disease, or took antiherpetic medications. For those reasons, 10 years is a generally agreed-upon adequate follow-up duration, as it addresses those limitations while also minimizing the reverse causality problem of shorter follow-up studies.

Our results, in regards to C. pneumoniae and CMV, are in line with the negative findings of other cohorts [21, 27, 28], and address some of their limitations (infrequent follow-up, reduced number of controls, large attrition rates and lack of monitoring for dementia).

Our findings did not confirm a reported connection between positive CMV serology, cognitive decline, and incidence of AD [26]. That cohort was on average 8.6 years older than our study population, and follow-up was of only 5 years. It is possible that a larger amount of his population was already in the preclinical stages of AD, and the shorter duration of follow-up does not permit to rule out reverse causality.

The increased risk of AD [31, 33], only in men on the NHANES retrospective cohort [33], with positive H. pylori was also not verified in our cohort, although we did see an association with worse global cognition, as described by Beydoun [33] and George [21]. The lack of such an association was also reported in the Rotterdam cohort [35]. Factors such as differences in strain virulence and case ascertainment are likely to account for the discrepancy in findings. The use of proton pump inhibitors could also be a confounding factor, as it has been reported, in in vitro and animal models, to be associated with increased production of pathogenic forms of amyloid-β [51] and decrease in acetylcholine [52]. Unfortunately, medication use information was not available in our cohort.

Our study’s main strengths stem from the large number of individuals that were assessed frequently, in a very detailed way, with well-validated cognitive and imaging measures, and for a prolonged time.

Some of the most important limitations in our study are the incomplete information on the severity, frequency, and timing of the herpetic infections and recurrences, which would have been very useful to clarify the correct interpretation of our finding of a protective effect of herpes labialis only in the 10 year follow-up. Moreover, the use of questionnaires, without laboratory confirmation of the herpetic infections, may have led to misclassification of some of the cases. However, in routine practice the clinical diagnosis is deemed accurate. Additional steps such as viral culture, Tzanck smears, or investigation of viral DNA by PCR are mostly used in immunocompromised patients, or cases with atypical features [53–55]. Yet another critical problem with the utilization of questionnaires in that setting is the very large interval between herpes labialis manifestations and the obtention of data. Since herpes infection peaks in the ages between 2 and 3 years old [56], and we have selected participants above the age of 60, a substantial risk of individuals in remission for decades to have forgotten their history of previous infection seems possible, and could generate a bias toward more severe or recurrent infections. Because participants did not have dementia at the time of the questionnaire, and remote memories tend to be much better preserved than short-term memories not only in prodromal, but also in established dementias, we think there is little reason to believe there would be a different rate of forgetting previous episodes of herpes labialis in both groups. Additionally, the lack of HSV serologies in most of the cohort, the absence of data on lymphocytic response and antiviral medication use prevent that firmer conclusions be drawn at this time.

Other limitations include the absence of CSF data, which would provide improved characterization of CNS involvement by the pathogens we studied, as well a more accurate diagnosis of AD. The serological assay used for C. pneumonia also had a low reproducibility, reducing the precision of our results. The generalizability of our findings is limited by the low number of participants from ethnic minorities in our cohorts. We also caution that corrections for multiple comparisons were not performed, which could increase the possibility of a type I error. Our findings are, therefore, to be viewed as hypothesisgenerating, and in need of confirmatory studies in different cohorts.

CONCLUSION

There was no association between positive serologies for H. pylori, CMV, and C. pneumonia, and incident dementia. History of chickenpox and zoster also had no association with the incidence of dementia. Herpes labialis was associated with a decreased 10-year risk of incident dementia, but no change in risk when follow-up continued for up to 35 years. Additional studies to confirm this finding and provide a clearer understanding of its significance are needed. Such studies, ideally in a prospective setting, would need to control for the use of antiviral agents and for the incidence and frequency of multiple possible clinical manifestations of herpes (labialis, genital, ocular, encephalitic, esophageal, cerebral), and harness neuroimaging, CSF, and plasma biomarkers. A more complete assessment of virus exposure, including serologies, immunophenotyping, lymphocyte assays and viral shedding, sampling mouth, tears, and olfactory pathways, would also be critical for an accurate understanding of the true prevalence of herpes simplex virus and its connection with neurodegenerative disease. Sampling the olfactory pathways would be of high interest given the anatomical connection with the limbic system and reports that olfactory herpes is more closely related to herpes encephalitis than herpes in the trigeminal pathway [57].

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Framingham Heart Study is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (contract no. 75N92019D00031, N01-HC-25195 and no. HHSN268201500001) and by grants from the National Institute on Aging (R01 AG054076, R01 AG049607, R01 AG033193. U01 AG049505. U01 AG052409, RF1 AG059421) and the National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke (NSO 17950 and UH2 NS 100605).

Footnotes

Authors’ diclosures available online (https://www.j-alz.com/manuscript-disclosures/20-0957r3).

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

The supplementary material is available in the electronic version of this article: https://dx.doi.org/10.3233/JAD-200957.

REFERENCES

- [1].Ball MJ (1982) Limbic predilection in Alzheimer dementia: Is reactivated herpesvirus involved? Can J Neurol Sci 9, 303–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Jamieson GA, Maitland NJ, Wilcock GK, Craske J, Itzhaki RF (1991) Latent herpes simplex virus type 1 in normal and Alzheimer’s disease brains. J Med Virol 33, 224–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Itzhaki RF, Golde TE, Heneka MT, Readhead B (2020) Do infections have a role in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer disease? Nat Rev Neurol 16, 193–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Smith JS, Robinson NJ (2002) Age-specific prevalence of infection with herpes simplex virus types 2 and 1: A global review. J Infect Dis 186(Suppl 1), S3–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Steel AJ, Eslick GD (2015) Herpes viruses increase the risk of Alzheimer’s disease: A meta-analysis. J Alzheimers Dis 47, 351–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Letenneur L, Peres K, Fleury H, Garrigue I, BarbergerGateau P, Helmer C, Orgogozo JM, Gauthier S, Dartigues JF (2008) Seropositivity to herpes simplex virus antibodies and risk of Alzheimer’s disease: A population-based cohort study. PLoS One 3, e3637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Lovheim H, Gilthorpe J, Adolfsson R, Nilsson LG, Elgh F (2015) Reactivated herpes simplex infection increases the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 11, 593–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Lovheim H, Gilthorpe J, Johansson A, Eriksson S, Hallmans G, Elgh F (2015) Herpes simplex infection and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease: A nested case-control study. Alzheimers Dement 11, 587–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Lovheim H, Norman T, Weidung B, Olsson J, Josefsson M, Adolfsson R, Nyberg L, Elgh F (2019) Herpes simplex Virus, APOEepsilon4, and cognitive decline in old age: Results from the Betula Cohort Study. J Alzheimers Dis 67, 211–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Tzeng NS, Chung CH, Lin FH, Chiang CP, Yeh CB, Huang SY, Lu RB, Chang HA, Kao YC, Yeh HW, Chiang WS, Chou YC, Tsao CH, Wu YF, Chien WC (2018) Anti-herpetic medications and reduced risk of dementia in patients with herpes simplex virus infections-a nationwide, population-based cohort study in Taiwan. Neurotherapeutics 15, 417–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Lopatko Lindman K HE, Weidung B, Brännström J, Josefsson M, Olsson J, Elgh F, Nordström P, Lövheim H (2021) Herpesvirus infections, antiviral treatmentm and the risk of dementia - a registry-based cohort study in Sweden. Alzheimers Dement (N Y) 7, el2119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Wozniak MA, Mee AP, Itzhaki RF (2009) Herpes simplex virus type 1 DNA is located within Alzheimer’s disease amyloid plaques. J Pathol 217, 131–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Eimer WA, Vijaya Kumar DK, Navalpur Shanmugam NK, Rodriguez AS, Mitchell T, Washicosky KJ, Gyorgy B, Breakefield XO, Tanzi RE, Moir RD (2018) Alzheimer’s disease-associated beta-amyloid is rapidly seeded by herpesviridae to protect against brain infection. Neuron 99, 56–63 e53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Balin BJ, Hammond CJ, Little CS, Hingley ST, Al-Atrache Z, Appelt DM, Whittum-Hudson JA, Hudson AP (2018) Chlamydia pneumoniae: An etiologic agent for late-onset dementia. Front Aging Neurosci 10, 302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Gerard HC, Dreses-Werringloer U, Wildt KS, Deka S, Oszust C, Balin BJ, Frey WH, Bordayo EZ, Whittum-Hudson JA, Hudson AP (2006) Chlamydophila (Chlamydia) pneumoniae in the Alzheimer’s brain. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 48, 355–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Ring RH, Lyons JM (2000) Failure to detect Chlamydia pneumoniae in the late-onset Alzheimer’s brain. J Clin Microbiol 38, 2591–2594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Gieffers J, Reusche E, Solbach W, Maass M (2000) Failure to detect Chlamydia pneumoniae in brain sections of Alzheimer’s disease patients. J Clin Microbiol 38, 881–882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Paradowski B, Jaremko M, Dobosz T, Leszek J, Noga L (2007) Evaluation of CSF-Chlamydia pneumoniae, CSFtau, and CSF-Abeta42 in Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. J Neurol 254, 154–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Yamamoto H, Watanabe T, Miyazaki A, Katagiri T, Idei T, Iguchi T, Mimura M, Kamijima K (2005) High prevalence of Chlamydia pneumoniae antibodies and increased high-sensitive C-reactive protein in patients with vascular dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 53, 583–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Chan Carusone S, Smieja M, Molloy W, Goldsmith CH, Mahony J, Chernesky M, Gnarpe J, Standish T, Smith S, Loeb M (2004) Lack of association between vascular dementia and Chlamydia pneumoniae infection: A case-control study. BMC Neurol 4, 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].George KM, Folsom AR, Norby FL, Lutsey PL (2020) No association found between midlife seropositivity for infection and subsequent cognitive decline: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Neurocognitive Study (ARIC-NCS). J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 33, 15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Korndewal MJ, Mollema L, Tcherniaeva I, van der Klis F, Kroes AC, Oudesluys-Murphy AM, Vossen AC, de Melker HE (2015) Cytomegalovirus infection in the Netherlands: Seroprevalence, risk factors, and implications. J Clin Virol 63, 53–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Weltevrede M, Eilers R, de Melker HE, van Baarle D (2016) Cytomegalovirus persistence and T-cell immunosenescence in people aged fifty and older: A systematic review. Exp Gerontol 77, 87–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Lin WR, Wozniak MA, Wilcock GK, Itzhaki RF (2002) Cytomegalovirus is present in a very high proportion of brains from vascular dementia patients. Neurobiol Dis 9, 82–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Lurain NS, Hanson BA, Martinson J, Leurgans SE, Landay AL, Bennett DA, Schneider JA (2013) Virological and immunological characteristics of human cytomegalovirus infection associated with Alzheimer disease. J Infect Dis 208, 564–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Barnes LL, Capuano AW, Aiello AE, Turner AD, Yolken RH, Torrey EF, Bennett DA (2015) Cytomegalovirus infection and risk of Alzheimer disease in older black and white individuals. J Infect Dis 211, 230–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Lovheim H, Olsson J, Weidung B, Johansson A, Eriksson S, Hallmans G, Elgh F (2018) Interaction between Cytomegalovirus and herpes simplex virus type 1 associated with the risk of Alzheimer’s disease development. J Alzheimers Dis 61, 939–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Torniainen-Holm M, Suvisaari J, Lindgren M, Harkanen T, Dickerson F, Yolken RH (2018) Association of cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus with cognitive functioning and risk of dementia in the general population: 11-year follow-up study. Brain Behav Immun 69, 480–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Brown LM (2000) Helicobacter pylori: Epidemiology and routes of transmission. Epidemiol Rev 22, 283–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Alvarez-Arellano L, Maldonado-Bernal C (2014) Helicobacter pylori and neurological diseases: Married by the laws of inflammation. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol 5, 400–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Roubaud Baudron C, Letenneur L, Langlais A, Buissonniére A, Mégraud F, Dartigues J-F, Salles N (2013) Does Helicobacter pylori infection increase incidence of dementia? The Personnes Agées QUID Study. J Am Geriatr Soc 61, 74–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Shindler-Itskovitch T, Ravona-Springer R, Leibovitz A, Muhsen K (2016) A systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between Helicobacter pylori infection and dementia. J Alzheimers Dis 52, 1431–1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Beydoun MA, Beydoun HA, Elbejjani M, Dore GA, Zonderman AB (2018) Helicobacter pylori seropositivity and its association with incident all-cause and Alzheimer’s disease dementia in large national surveys. Alzheimers Dement 14, 1148–1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Huang WS, Yang TY, Shen WC, Lin CL, Lin MC, Kao CH (2014) Association between Helicobacter pylori infection and dementia. J Clin Neurosci 21, 1355–1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Fani L, Wolters FJ, Ikram MK, Bruno MJ, Hofman A, Koudstaal PJ, Darwish Murad S, Ikram MA (2018) Helicobacter pylori and the risk of dementia: A population-based study. Alzheimers Dement 14, 1377–1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Lahoz C, Schaefer EJ, Cupples LA, Wilson PW, Levy D, Osgood D, Parpos S, Pedro-Botet J, Daly JA, Ordovas JM (2001) Apolipoprotein E genotype and cardiovascular disease in the Framingham Heart Study. Atherosclerosis 154, 529–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Blackwelder WC, Dolin R, Mittal KK, McNamara PM, Payne FJ (1982) A population study of herpesvirus infections and HLA antigens. Am J Epidemiol 115, 569–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Satizabal CL, Beiser AS, Chouraki V, Chene G, Dufouil C, Seshadri S (2016) Incidence of dementia over three decades in the Framingham Heart Study. N Engl J Med 374, 523–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].DeCarli C, Massaro J, Harvey D, Hald J, Tullberg M, Au R, Beiser A, D’Agostino R, Wolf PA (2005) Measures of brain morphology and infarction in the framingham heart study: Establishing what is normal. Neurobiol Aging 26, 491–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Pase MP, Beiser A, Enserro D, Xanthakis V, Aparicio H, Satizabal CL, Himali JJ, Kase CS, Vasan RS, DeCarli C, Seshadri S (2016) Association of ideal cardiovascular health with vascular brain injury and incident dementia. Stroke 47, 1201–1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Schuhmacher A, Reichling J, Schnitzler P (2003) Virucidal effect of peppermint oil on the enveloped viruses herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2 in vitro. Phytomedicine 10, 504–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Jautova J, Zelenkova H, Drotarova K, Nejdkova A, Grunwaldova B, Hladikova M (2019) Lip creams with propolis special extract GH 2002 0.5% versus aciclovir 5.0% for herpes labialis (vesicular stage): Randomized, controlled double-blind study. Wien Med Wochenschr 169, 193–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Petti S, Lodi G (2019) The controversial natural history of oral herpes simplex virus type 1 infection. Oral Dis 25, 1850–1865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Khan AA, Srivastava R, Chentoufi AA, Kritzer E, Chilukuri S, Garg S, Yu DC, Vahed H, Huang L, Syed SA, Furness JN, Tran TT, Anthony NB, McLaren CE, Sidney J, Sette A, Noelle RJ, BenMohamed L (2017) Bolstering the number and function of HSV-1-Specific CD8(+) effector memory T cells and tissue-resident memory T cells in latently infected trigeminal ganglia reduces recurrent ocular herpes infection and disease. J Immunol 199, 186–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Poccardi N, Rousseau A, Haigh O, Takissian J, Naas T, Deback C, Trouillaud L, Issa M, Roubille S, Juillard F, Efstathiou S, Lomonte P, Labetoulle M (2019) Herpes simplex virus 1 replication, ocular disease, and reactivations from latency are restricted unilaterally after inoculation of virus into the lip. J Virol 93, e01586–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Delmonte S, Sidoti F, Ribero S, Dal Conte I, Curtoni A, Ciccarese G, Stroppiana E, Stella ML, Costa C, Cavallo R, Rebora A, Drago F (2019) Recurrent herpes labialis and Herpes simplex virus-1 genitalis: What is the link? G Ital Dermatol Venereol 154, 529–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Posavad CM, Remington M, Mueller DE, Zhao L, Magaret AS, Wald A, Corey L (2010) Detailed characterization of T cell responses to herpes simplex virus-2 in immune seronegative persons. J Immunol 184, 3250–3259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Kaufman HE, Azcuy AM, Varnell ED, Sloop GD, Thompson HW, Hill JM (2005) HSV-1 DNA in tears and saliva of normal adults. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 46, 241–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Lin WR, Shang D, Wilcock GK, Itzhaki RF (1995) Alzheimer’s disease, herpes simplex virus type 1, cold sores and apolipoprotein E4. Biochem Soc Trans 23, 594S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Koelle DM, Magaret A, Warren T, Schellenberg GD, Wald A (2010) APOE genotype is associated with oral herpetic lesions but not genital or oral herpes simplex virus shedding. Sex Transm Infect 86, 202–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Badiola N, Alcalde V, Pujol A, Munter LM, Multhaup G, Lleo A, Coma M, Soler-Lopez M, Aloy P (2013) The proton-pump inhibitor lansoprazole enhances amyloid beta production. PLoS One 8, e58837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Kumar R, Kumar A, Nordberg A, Langstrom B, Darreh-Shori T (2020) Proton pump inhibitors act with unprecedented potencies as inhibitors of the acetylcholine biosynthesizing enzyme-A plausible missing link for their association with incidence of dementia. Alzheimers Dement 16, 1031–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Siegel MA (2002) Diagnosis and management of recurrent herpes simplex infections. J Am Dent Assoc 133,1245–1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Fatahzadeh M, Schwartz RA (2007) Human herpes simplex labialis. Clin Exp Dermatol 32, 625–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Arduino PG, Porter SR (2008) Herpes simplex virus type 1 infection: Overview on relevant clinico-pathological features. J Oral Pathol Med 37, 107–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Leung AKC, Barankin B (2017) Herpes labialis: An update. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov 11, 107–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Steiner I, Benninger F (2013) Update on herpes virus infections of the nervous system. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 13, 414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.