Abstract

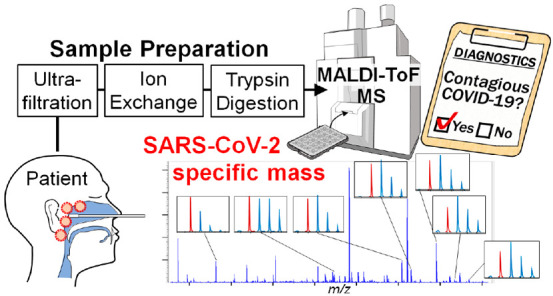

The most common diagnostic method used for coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) is real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (PCR). However, it requires complex and labor-intensive procedures and involves excessive positive results derived from viral debris. We developed a method for the direct detection of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in nasopharyngeal swabs, which uses matrix-assisted laser desorption and ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-ToF MS) to identify specific peptides from the SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid phosphoprotein (NP). SARS-CoV-2 viral particles were separated from biological molecules in nasopharyngeal swabs by an ultrafiltration cartridge. Further purification was performed by an anion exchange resin, and purified NP was digested into peptides using trypsin. The peptides from SARS-CoV-2 that were inoculated into nasopharyngeal swabs were detected by MALDI-ToF MS, and the limit of detection was 106.7 viral copies. This value equates to 107.9 viral copies per swab and is approximately equivalent to the viral load of contagious patients. Seven NP-derived peptides were selected as the target molecules for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 in clinical specimens. The method detected between two and seven NP-derived peptides in 19 nasopharyngeal swab specimens from contagious COVID-19 patients. These peptides were not detected in four specimens in which SARS-CoV-2 RNA was not detected by PCR. Mutated NP-derived peptides were found in some specimens, and their patterns of amino acid replacement were estimated by accurate mass. Our results provide evidence that the developed MALDI-ToF MS-based method in a combination of straightforward purification steps and a rapid detection step directly detect SARS-CoV-2-specific peptides in nasopharyngeal swabs and can be a reliable high-throughput diagnostic method for COVID-19.

Introduction

Currently, the most common method for coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) diagnosis is real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) targeting the S, E, or N gene of SARS-CoV-2. Various RT-PCR primer and probe sets and commercial kits are being used by hospitals and laboratories.1−3 RT-PCR requires complex components and reagents and a temperature-sensitive reaction. Laboratory technicians need to take care to avoid contamination or the amplification errors. Additionally, it is difficult to distinguish the intact virus from degraded viral RNA in clinical samples using RT-PCR; thus, noncontagious patients may be labeled as contagious.4 To curb COVID-19 transmission, the rapid identification of contagious patients is crucial. Thus, an alternative to RT-PCR is required for diagnosis.

Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), LC-orbitrap mass spectrometry, and LC-quadruple time-of-flight mass spectrometry (LC-QToF MS) have been applied to detect SARS-CoV-2-specific peptides in COVID-19 clinical samples.5−8 Methodologies should rely on a sufficient number of specific peptides, and the developed approaches may be not so reliable5,8 because amino acid modification or mutation affects the mass even if the alterations are minimal. In addition, MS analysis using LC needs a long time, e.g., 40 or 180 min per sample, for separation step.5−7 Analytical methods using immunoaffinity purification approaches followed by LC-MS analysis were developed.9,10 These methods can efficiently purify SARS-CoV-2-specific peptides from clinical samples, but the use of special antibodies lacks generality.

Matrix-assisted laser desorption and ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-ToF MS) identifies proteins and digestion-derived peptides by a simple procedure that requires no complex reagents and has a minimal risk of contamination. MALDI-ToF MS detects ions over a wide mass range; it identifies the modification or mutation and rapidly analyzes peptides in several seconds per sample. MALDI-ToF MS is widely used to identify bacterial and fungal species based on specific mass combinations generated by their proteins.11,12 In virology, MALDI-ToF MS is used to characterize viral coat proteins directly from the intact tobacco mosaic virus and to identify different respiratory viruses, such as the influenza virus, in cell cultures of clinical samples by protein spectra profiling.13,14 Proteins and trypsin-digested peptides from SARS-CoV-1 have been also characterized by MALDI-ToF MS.15 In these studies, clinical samples were cultured with cells, and the virus in supernatants were analyzed. The culture process is time-consuming and not suitable for rapid diagnosis. In other study, SARS-CoV-2 particles in a gargle sample were partially purified by ultracentrifugation, and the viral envelop proteins were analyzed by MALDI-ToF MS.16 The broad signals derived from crude proteins might make it difficult to accurately diagnose COVID-19. Another group found SARS-CoV-2-derived peptides for the MALDI Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance (FT-ICR) MS detection of SARS-CoV-2 in nasopharyngeal swabs.17 However, it was not tested whether these peptides were detected in clinical samples. Machine learning analysis of proteins and peptides identified by MALDI-ToF MS in clinical samples has been also investigated for COVID-19 diagnostic purposes, and potential patient-derived biomarkers have been identified.18−20 However, there is the concern of making a false diagnosis of COVID-19 using a screening method based on biomarker analysis. Therefore, a diagnostic method to identify SARS-CoV-2-specific proteins or peptides in nasopharyngeal swabs is a reliable way to detect SARS-CoV-2 infection, but no studies have succeeded in detecting specific molecules that originate from SARS-CoV-2 in clinical samples for diagnosis by MALDI-ToF MS. Several proteins present in nasopharyngeal swabs hamper the detection of SARS-CoV-2-specific proteins and peptides by MALDI-ToF MS. Consequently, we contrived a method that takes advantage of the properties of SARS-CoV-2 particles and proteins to purify them from nasopharyngeal swabs. To accurately determine whether a patient is contagious or not, we evaluated the detection limit of the MALDI-ToF MS. In addition, a novel diagnostic method using MALDI-ToF-MS analysis of specific peptides derived from intact particles of SARS-CoV-2 purified from nasopharyngeal swabs of COVID-19 patients is described.

Experimental Section

Ethics Statement

The study design and the protocol for the use of swab eluates from volunteers were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the National Institute of Health Sciences, Japan (NIHS) (approval no. 339). All experiments with live SARS-CoV-2 were performed in a biosafety level 3 (BSL3) facility at NIHS, and those for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 from patient specimens were also reviewed and approved by the IRB of the NIHS (approval No. 347) and the IRB of Saitama Medical University Hospital (approval no. 20166.01).

Cells and Virus

Vero E6/TMPRSS2 cells (JCRB1819)21 were obtained from the Japanese Collection of Research Bioresources (JCRB) Cell Bank. The SARS-CoV-2 JPN/TY/WK-521 strain was obtained from the National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Japan. The methods for the purification of inactivated and live SARS-CoV-2 and the quantification of copy numbers are described in Supporting Information S1.

Purification of SARS-CoV-2 Particles from Nasopharyngeal Swabs Inoculated with the Inactivated Virus

Nasopharyngeal swabs were provided by volunteers with informed consent and were confirmed to be SARS-CoV-2-negative by RT-PCR before use according to the method described in Supporting Information S2. Each nasopharyngeal swab was placed in a sterile tube containing 1 mL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and the tube was vigorously shaken. The swab was removed, and the eluate was centrifuged at 11 200 × g for 5 min. For the sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE, Supporting Information S3) analysis, a 400 μL aliquot of the supernatant, a suspension of inactivated SARS-CoV-2 (109.0 copies), or a mixture of the two was filtered with a 0.22 μm cartridge filter (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). The filtrate was concentrated to a small volume (5–10 μL) in a 30, 100, or 300 kDa MWCO ultrafiltration cartridge (Pall Corporation, Ann Arbor, MI) at 2000 × g. The solution that passed through the cartridge membrane was collected as the flow-through fraction (FF). The fraction was concentrated by acetone precipitation, and the precipitate was subjected to SDS-PAGE. Water (400 μL) was added to the cartridge, and the sample concentration procedure was repeated. The residual liquid on the cartridge membrane was collected. The membrane was washed with water, which was then collected and combined with the residual liquid. The total amount of the concentrate was adjusted to 40 μL. This sample was collected as the concentrated fraction (CF). For SDS-PAGE analysis, the fraction was lyophilized, and the residue was dissolved in the protein sample buffer. Further purification was performed by mixing the fraction with 50 μL of 2-propanol, then adding 20 μL (suspension volume) of Q Sepharose XL resin (Cytiva, Uppsala, Sweden). After being shaken for 20 min at 1600 rpm, the resin was removed by filtration, and the filtrate was evaporated to dryness using a centrifugal evaporator (Micro Vac MV-100, Tomy Seiko, Tokyo, Japan). The residue was dissolved in the protein sample buffer. The method for the identification of the protein band is described in Supporting Information S4.

SARS-CoV-2 Detection in Nasopharyngeal Swabs Inoculated with the Live Virus by MALDI-ToF MS

The serially diluted live SARS-CoV-2 samples (108.7, 107.7, 106.7, or 105.7 copies in 5 μL of water) were inoculated in 70 μL of the above-mentioned nasopharyngeal swab eluate in PBS. After 330 μL of water was added to the eluate, the mixture was filtered with a 0.22 μm cartridge filter (Merck KGaA). The filtrate was concentrated to 5–10 μL using a 300 kDa MWCO ultrafiltration cartridge (Pall) at 2000 × g, and further purification was performed as described in “Purification of SARS-CoV-2 Particles from Nasopharyngeal Swabs Inoculated with the Inactivated Virus”. After evaporation by a centrifugal evaporator, the residue was dissolved in 30 μL of a digestion buffer containing 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate, 10% acetonitrile, and 200 ng of MS-grade trypsin protease (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). The mixture was incubated for 120 min at 37 °C. The digested sample was purified and concentrated on a ZipTip 0.6 μL C18 (Merck KGaA) pipette tip. The tip was preconditioned with acetonitrile, then 50% acetonitrile containing 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA; FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Osaka, Japan), and finally 10% acetonitrile containing 0.1% TFA. The digested sample was acidified with 1 μL of 10% TFA and then aspirated and dispensed 12 times through a ZipTip. The sample was washed three times with 20 μL of 10% acetonitrile containing 0.1% TFA. Peptides were eluted into a 96-well sample plate for MALDI-ToF MS by aspirating and dispensing 3 μL of 50% acetonitrile containing 0.1% TFA and 10 g/L 4-chloro-α-cyanocinnamic acid (ClCCA; Merck KGaA) four times and were allowed to air-dry.

MALDI-ToF MS Analysis

MS analysis was performed on an MS-S3000 SpiralTOF-plus spectrometer (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan). Instrument settings were as follows: mode, spiral positive; laser intensity, 55%; delay time, 330 ns; detector, 60%; mass range, 700–3000 m/z; and laser frequency, 250 Hz. The ProteoMass Peptide MALDI-MS Calibration Kit (Merck KGaA) was used as an external standard. The signal-to-noise (S/N) ratio was calculated by comparing the height (intensity) of the peptide peak with the height of the noise around the peptide peak.

SARS-CoV-2 Detection in Nasopharyngeal Swabs of COVID-19 Patients

Nasopharyngeal swabs from patients who underwent testing for COVID-19 (19 COVID-19-positive and 4 COVID-19-negative) at Saitama Medical University Hospital between December 2020 and March 2021 were used. Swabs were collected in accordance with the nationally recommended protocol in Japan.22 Patients were provided with the opportunity to opt out of the secondary use of their specimens in this study. Viral RNA levels and viral titers in swab eluates were measured by RT-PCR and the median tissue culture infective dose (TCID50), respectively, according to the methods described in Supporting Information S2 and S5. A 70 or 210 μL aliquot of the swab eluate was mixed with 330 or 190 μL of water, respectively, to achieve a total volume of 400 μL, and the mixture centrifuged at 11 430 × g for 5 min. Viral purification from the diluted swab eluates and MALDI-ToF MS analysis were performed as described above. In addition to the external standard, m/z 842.5095, m/z 1400.6805, or both were used as internal standards for mass calibration. The former peptide was derived from trypsin, and the latter peptide was derived from lysozyme (a contaminating protein in the nasopharyngeal swab). The method for nucleotide sequence analysis for the sequence-typing of SARS-CoV-2 strains in the swab eluates is described in Supporting Information S6.

Results and Discussion

Analysis of Proteins from Purified SARS-CoV-2

The inactivated viral particles (109.0 copies) were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and a major band at 50 kDa was observed in the gel stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue (CBB) (Figure S1A). The copy number of inactivated SARS-CoV-2 was quantified by RT-PCR (Figure S2A). Tryptic peptides from the 50 kDa band on the gel were analyzed by MALDI-ToF MS. A MASCOT database search revealed that the 20 peptides were derived from nucleocapsid phosphoprotein (NP) of SARS-CoV-2 (Figure S1B and Table S1). Tryptic peptides derived from this protein were candidate molecules for the MALDI-ToF MS analysis.

Purification of SARS-CoV-2 NP in a Nasopharyngeal Swab Eluate

Several proteins, such as IgA, lactoferrin, and lysozyme, are present in nasopharyngeal swabs.23 Because these proteins may interfere with SARS-CoV-2 detection, purification steps before MS analysis are essential. To purify viral particles from environmental samples and cell lysates, ultrafiltration was used in some studies, yielding high virus recoveries.24,25

SDS-PAGE analysis of a suspension of inactivated SARS-CoV-2 filtered with each of the three MWCO ultrafiltration cartridges showed that almost all the viral particles were observed in the concentrated fraction on the membranes of the 30, 100, and 300 kDa MWCO ultrafiltration cartridges (Figure 1A lanes 2, 4, and 6, respectively) and did not pass through the three MWCO ultrafiltration membrane (Figure 1A, lanes 3, 5, and 7, respectively). The concentrated fractions of a nasopharyngeal swab eluate filtrated with each of three MWCO ultrafiltration cartridges and the flow-through fractions were resolved by SDS-PAGE. Many protein bands were observed in the nasopharyngeal swab eluate (Figure. 1B, lane 1). When a 30 kDa MWCO ultrafiltration cartridge was used, most proteins were collected in the concentrated fraction (Figure 1B, lane 2), and few proteins were detected in the flow-through fraction (Figure 1B, lane 3). Proteins were separated in both the concentrated and flow-through fractions when a 100 kDa MWCO ultrafiltration cartridge was used (Figure 1B, lanes 4 and 5, respectively). Protein bands were hardly found in the concentrated fraction on the membrane of the 300 kDa MWCO ultrafiltration cartridge (Figure 1B, lane 6), while most proteins were present in the flow-through (Figure 1B, lane 7). These results indicated that use of a 300 kDa MWCO ultrafiltration cartridges might be effective for the purification of virus particles and the concentration of viral particle suspensions for volumes from several hundred microliters to 5–10 μL. In the SDS-PAGE analysis of the nasopharyngeal swab eluate inoculated with inactivated SARS-CoV-2 that was fractionated by the 300 kDa MWCO ultrafiltration cartridge, the proteins from the swab eluate and the viral particles were clearly separated into the different fractions (Figure 1C, lanes 1–3).

Figure 1.

Purification and concentration of SARS-CoV-2 particles in a nasopharyngeal swab eluate. (A) SDS-PAGE analysis of concentrated SARS-CoV-2 particles. Lane M contained the protein standard. The SARS-CoV-2 suspension (lane 1) was concentrated by each of the three MWCO ultrafiltration cartridges. The concentrated fraction (CF) and the flow-through fraction (FF) were analyzed to check which fraction the virus particles were collected in. Lane 2 contained the CF of 30 kDa MWCO, lane 3 contained the FF of 30 kDa MWCO, lane 4 contained the CF of 100 kDa MWCO, lane 5 contained the FF of 100 kDa MWCO, lane 6 contained the CF of 300 kDa MWCO, and lane 7 contained the FF of 300 kDa MWCO. (B) SDS-PAGE analysis of fractionated proteins in a nasopharyngeal swab eluate. Lane M contained the protein standard. The swab eluate (lane 1) was passed through each of the three molecular weight cutoff (MWCO) ultrafiltration cartridges. The CF and FF were analyzed to check the separated proteins. Lane 2 contained the CF of 30 kDa MWCO, lane 3 contained the FF of 30 kDa MWCO, lane 4 contained the CF of 100 kDa MWCO, lane 5 contained the FF of 100 kDa MWCO, lane 6 contained the CF of 300 kDa MWCO, and lane 7 contained the FF of 300 kDa MWCO. (C) SDS-PAGE analysis of purification steps for SARS-CoV-2 particles from a nasopharyngeal swab eluate. Lane M contained the protein standard. SARS-CoV-2 particles were mixed with a nasopharyngeal swab eluate (lane 1) and fractionated by a 300 kDa MWCO ultrafiltration cartridge. The FF (lane 2) and CF (lane 3) were analyzed to check the separated proteins and virus particles. The CF was further purified by Q Sepharose XL resin to remove contaminating proteins from the nasopharyngeal swab eluate (lane 4). Black arrows and a red arrow indicate contaminating proteins and the SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid phosphoprotein, respectively.

Further purification by an anion exchange resin, Q Sepharose XL, was performed to remove some contaminating bands from the swab eluate that were observed in the concentrated fraction (Figure 1C, lane 3, black arrows). The concentrated fraction was mixed with an equal amount of 2-propanol (final concentration of 50%) to extract the NP. Q Sepharose XL resin was added to the mixture, and contaminating proteins from the swab eluate, but not the NP, were adsorbed on the resin. The resin was removed by filtration, and the filtrate was resolved by SDS-PAGE. The contaminating proteins were clearly removed, and a single band derived from the NP was observed (Figure 1C, lane 4, a red arrow). The theoretical isoelectric point (pI) of SARS-CoV-2 NP is 10.07.26 Because of its high pI, SARS-CoV-2 NP had a positive charge in 50% 2-propanol and was not captured by the positively charged anion exchange resin. Negatively charged contaminating proteins were adsorbed with the resin and removed from the sample. The result of the image analysis showed that almost none of the NP was lost during these purification steps using a 300 kDa MWCO ultrafiltration cartridge and Q Sepharose XL.

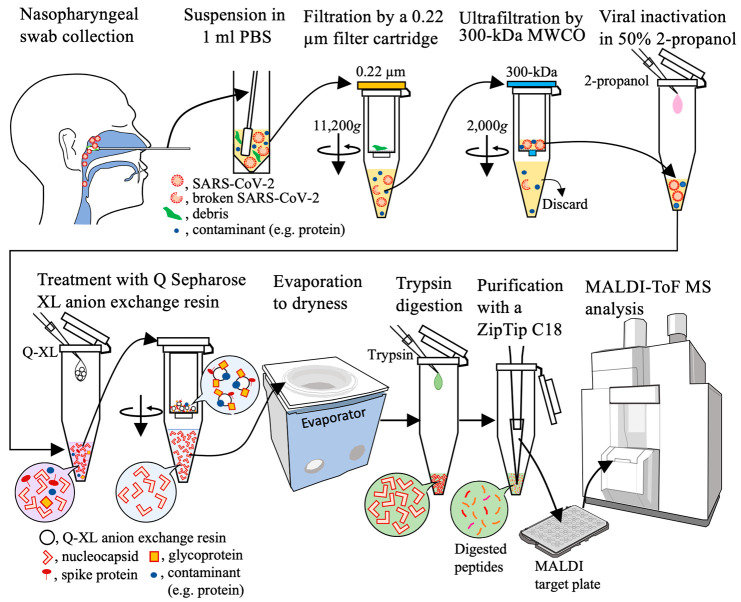

Detection of SARS-CoV-2 NP in a Nasopharyngeal Swab Inoculated with Live SARS-CoV-2

According to the results above, the workflow for SARS-CoV-2 detection in a nasopharyngeal swab by MALDI-ToF MS was determined as shown in Figure 2. Briefly, a nasopharyngeal swab eluate was filtered with a 0.22 μm cartridge filter to remove the cellular debris. The filtrate was concentrated with a 300 kDa MWCO ultrafiltration cartridge, and contaminating proteins were removed. The NP was extracted from the viral particles with 50% 2-propanol, and other contaminating proteins were adsorbed on Q Sepharose XL resin. After evaporating the inorganic solvent, the NP was digested with trypsin. The reaction solution was desalted and concentrated on a ZipTip, a pipet tip with a bed of chromatography media, and NP-derived peptides were detected by MALDI-ToF MS.

Figure 2.

Workflow of the method for the purification and concentration of SARS-CoV-2 particles in a nasopharyngeal swab eluate.

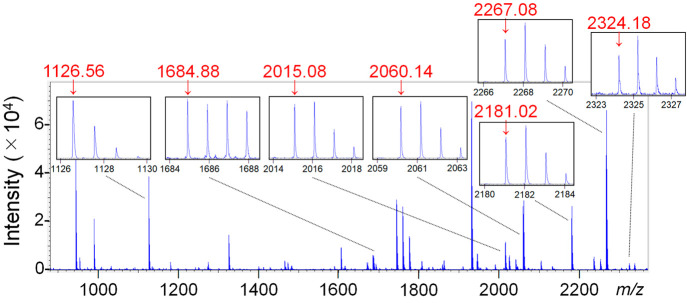

In accordance with the workflow, MALDI-ToF MS analysis of the nasopharyngeal swab eluate inoculated with live SARS-CoV-2 was performed. The copy number of live SARS-CoV-2 was quantified by RT-PCR (Figure S2A). In the MALDI-ToF MS analysis of the nasopharyngeal swab eluate inoculated with 108.7 copies of the live virus, seven NP-derived peptides were observed (Figure 3). When five blank nasopharyngeal swab eluates were analyzed, the average S/N ratios where the seven peptides were detected were between 0.86 and 1.10 (Table 1). Based on this result, the threshold average value for S/N ratios of the NP-derived peptides was set to 2.0. All the average S/N ratios of the seven NP-derived peptides detected in the nasopharyngeal swab eluate inoculated with 108.7 and 107.7 copies were ≥2.0 (Table 1). With 106.7 copies, the average S/N ratios of the three peptides were ≥2.0, while no average values were ≥2.0 with 105.7 copies. This result showed that the detection limit of the virus in a nasopharyngeal swab was 106.7 copies. This value is equivalent to 107.9 copies per milliliter when using a 70 μL swab eluate. According to the recent mathematical model,27 the viral load required for SARS-CoV-2 transmission is approximately three times larger than that required for infection. Positive results by RT-PCR do not necessarily indicate the shedding of infectious virus because noninfectious virus is also detectable using this method.4,28 In fact, it was reported that a viral load of >107.6 copies per swab is required for successful viral isolation from clinical specimens.29 The threefold value of 107.6 copies per swab is equivalent to 108.1 copies per swab in the context of the mathematical model27 and is assumed to be the viral copy number required for SARS-CoV-2 transmission. The MALDI-ToF MS-based diagnostic method established in this study can therefore detect transmissible virus levels in clinical specimens.

Figure 3.

MALDI-ToF MS spectrum of a tryptic digest of SARS-CoV-2 particles purified from a nasopharyngeal swab eluate. The seven peptide peaks derived from the nucleocapsid phosphoprotein are enlarged in small frames. The signals of the objective peptides are indicated by red arrows with their m/z values (red numbers).

Table 1. S/N Ratios of Peptide Signals from Tryptic Digests of SARS-CoV-2 Particles Inoculated in Nasopharyngeal Swab Eluates.

| S/N ratioa |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| peptide (m/z) | 108.7 | 107.7 | 106.7 | 105.7 | blank |

| 1126 | 130.95 ± 58.23 | 26.77 ± 8.02 | 3.62 ± 2.16 | 1.01 ± 0.21 | 0.87 ± 0.25 |

| 1685 | 41.74 ± 22.36 | 8.96 ± 5.41 | 1.29 ± 0.58 | 1.21 ± 0.12 | 1.00 ± 0.10 |

| 2015 | 22.01 ± 9.04 | 13.28 ± 6.00 | 1.76 ± 0.92 | 0.87 ± 0.19 | 0.86 ± 0.18 |

| 2060 | 70.28 ± 24.17 | 20.50 ± 7.40 | 2.44 ± 0.53 | 1.08 ± 0.09 | 1.10 ± 0.13 |

| 2181 | 113.06 ± 58.77 | 35.46 ± 10.12 | 3.77 ± 1.66 | 1.08 ± 0.07 | 1.03 ± 0.16 |

| 2267 | 74.38 ± 46.98 | 7.56 ± 3.89 | 1.25 ± 0.20 | 0.91 ± 0.20 | 0.99 ± 0.16 |

| 2324 | 15.38 ± 2.78 | 2.89 ± 1.16 | 1.39 ± 0.17 | 1.13 ± 0.18 | 0.96 ± 0.28 |

Values are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (n = 5).

Recently, a method to inactivate SARS-CoV-2 during sample preparation for proteomics experiments was reported.30 By adopting an inactivation method, some purification steps do not have to be performed in a BSL3 facility, and the efficiency of our method may be increased.

In another study using one purification step by ultrafiltration, followed by MALDI-FT-ICR MS detection, high background signals were observed.17 We adapted two purification steps using an ultrafiltration cartridge and an anion exchange resin and used a high-resolution MALDI-ToF MS. This method enabled the low-background measurement of peptides derived from SARS-CoV-2.

Detection of SARS-CoV-2 NP in Nasopharyngeal Swabs of COVID-19 Patients

Neither viral RNA analyzed by RT-PCR nor viral titers measured by TCID50 assays were detected in 4 out of 23 nasopharyngeal swab specimens (Table 2, IDs 20–23). These patients were regarded as negative for COVID-19. The MALDI-ToF MS spectrum of the specimen from ID 20 is shown in Figure S3A. The signals of the seven NP-derived peptides were not observed in this sample. The S/N ratios of NP-derived peptides in the MALDI-ToF MS results of these RT-PCR-negative specimens were used to set detection thresholds. Because the S/N ratios of four NP-derived peptides at m/z 1126, 1685, 2015, and 2267 were <1.55 in these four negative specimens, their threshold S/N ratios were set to 2.0. The S/N ratio threshold was set to 1.5 for three NP peptides at m/z 2060, 2181, and 2324, since the S/N ratios in the negative specimens were <1.25.

Table 2. Analysis of SARS-CoV-2 in Clinical Nasopharyngeal Swabs.

| RT-PCR |

m/z value (S/N threshold) |

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ID | sex | age | symptom | clinical severity | collection time from the onset of symptoms (days) | Cta value | copies per mL | viral titer (TCID50/mL) | 1126 (2.0) | 1685 (2.0) | 2015 (2.0) | 2060 (1.5) | 2181 (1.5) | 2267 (2.0) | 2324 (1.5) | number of detected peptides |

| RT-PCR positive patients | ||||||||||||||||

| 1 | M | 77 | UKb | UK | UK | 16.4 | 109.6 | 105.8 | 7.00 | 2.83 | 3.95 | 2.03 | 3.58 | 3.09 | 1.75 | 7 |

| 2 | F | 71 | fever | mild | 1 | 20.0 | 109.1 | 106.1 | 11.16 | 5.38 | 4.78 | 6.98 | 23.20 | 1.12 | 1.80 | 6 |

| 3 | F | 40 | sore throat | mild | 2 | 17.7 | 109.7 | 106.1 | 72.12 | 36.09 | 41.35 | 1.13 | 143.79 | 14.10 | 8.56 | 6 |

| 4 | F | 91 | UK | death | UK | 21.4 | 108.1 | 104.1 | 5.10 | 2.70 | 2.06 | 2.36 | 3.23 | 1.04 | 1.02 | 5 |

| 5 | M | 94 | UK | UK | UK | 22.8 | 108.3 | 104.3 | 2.63 | 1.58 | 1.38 | 1.29 | 1.80 | 0.81 | 1.34 | 2 |

| 6 | F | 68 | UK | mild | UK | 18.6 | 109.5 | 105.9 | 78.86 | 43.02 | 40.89 | 41.36 | 172.91 | 9.80 | 9.01 | 7 |

| 7 | F | 51 | sore throat | mild | 2 | 23.9 | 108.0 | 104.1 | 10.89 | 4.52 | 4.33 | 4.75 | 11.30 | 1.61 | 1.34 | 5 |

| 8 | M | 81 | cough | mild | 2 | 20.8 | 108.8 | 105.1 | 6.13 | 3.66 | 2.73 | 6.95 | 5.92 | 0.90 | 1.64 | 6 |

| 9 | M | 71 | fever | mild | 2 | 19.5 | 108.7 | 104.6 | 3.80 | 1.48 | 1.73 | 0.66 | 2.38 | 1.33 | 1.15 | 2 |

| 10 | F | 66 | UK | mild | UK | 18.8 | 108.9 | 105.3 | 18.75 | 7.10 | 4.03 | 1.04 | 22.00 | 2.76 | 2.45 | 6 |

| 11 | F | 89 | fever | mild | –1 | 17.3 | 109.9 | 106.3 | 31.25 | 7.13 | 8.06 | 19.73 | 22.96 | 7.04 | 6.93 | 7 |

| 12 | M | 99 | sore throat | mild | 0 | 18.4 | 109.6 | 106.3 | 57.03 | 14.91 | 13.85 | 5.84 | 22.05 | 12.22 | 6.83 | 7 |

| 13 | F | 85 | fever | mild | 2 | 22.5 | 108.3 | 103.9 | 6.80 | 3.71 | 4.24 | 4.80 | 9.97 | 1.45 | 1.22 | 5 |

| 14 | F | 87 | fever | mild | 1 | 17.6 | 109.2 | 105.6 | 9.48 | 3.52 | 2.58 | 9.50 | 20.54 | 5.81 | 2.33 | 7 |

| 15 | F | 81 | fever | severe | 2 | 20.2 | 109.0 | 105.3 | 30.40 | 12.40 | 12.29 | 2.99 | 34.97 | 6.97 | 3.88 | 7 |

| 16 | F | 87 | fever | mild | 2 | 18.8 | 109.4 | 106.3 | 10.59 | 6.51 | 9.18 | 2.52 | 31.66 | 2.15 | 2.82 | 7 |

| 17 | F | 32 | UK | mild | UK | 19.7 | 109.1 | 105.1 | 6.36 | 4.96 | 5.26 | 2.30 | 14.37 | 1.04 | 1.71 | 6 |

| 18 | F | 40 | fever | mild | 1 | 19.0 | 109.3 | 105.3 | 22.93 | 13.04 | 19.48 | 6.22 | 27.66 | 5.67 | 2.84 | 7 |

| 19c | M | 80 | UK | mild | UK | 23.9 | 108.0 | 104.1 | 2.07 | 1.54 | 1.32 | 1.70 | 1.47 | 0.79 | 1.21 | 2 |

| RT-PCR negative patients | ||||||||||||||||

| 20 | M | 82 | fever | NAd | UK | UDe | UD | UD | 1.47 | 0.85 | 1.43 | 1.13 | 1.18 | 1.42 | 1.18 | 0 |

| 21 | F | 44 | cough | NA | UK | UD | UD | UD | 1.10 | 1.25 | 0.94 | 1.13 | 0.77 | 0.78 | 0.67 | 0 |

| 22 | F | 28 | fever | NA | UK | UD | UD | UD | 1.13 | 1.34 | 1.16 | 1.20 | 1.00 | 0.69 | 1.13 | 0 |

| 23 | F | 70 | fever | NA | UK | UD | UD | UD | 1.55 | 1.09 | 0.90 | 1.11 | 1.25 | 1.03 | 0.88 | 0 |

Threshold cycle.

UK, unknown.

Used 210 μL of the swab eluate.

NA, not applicable.

UD, undetermined.

The SARS-CoV-2 copy numbers in 19 specimens (ID1–19) calculated using standard RT-PCR curves (Figure S2B–E) were between 108.0 and 109.9 copies per milliliter (Table 2). The titers of 19 infectious specimens (IDs 1–19) were between 103.9 and 106.3 TCID50/mL (Table 2). In the MALDI-ToF MS spectrum of specimen ID 6, seven NP peptides were typically observed (Figure S3B). Based on the S/N ratio thresholds, the number of detected NP-derived peptides was calculated for all RT-PCR-positive specimens (Table 2). We detected seven, six, five, and two NP-derived peptides in seven, five, four, and three specimens, respectively. Regarding the result of ID 19, one NP-derived peptide (m/z 2181) was detected when 70 μL of the swab eluate was used (data not shown), while two NP-derived peptides (m/z 1126 and m/z 2060) were found when 210 μL of the swab eluate was used (Table 2).

In our COVID-19-positive specimens, a strong correlation (R2 = 0.88) was observed between RT-PCR copy numbers and TCID50 titers, and an approximately 103.8-fold (99.99% confidence interval from 103.4 to 104.2) difference was observed between them (Table 2 and Figure S4, the red-colored data). A similar observation was reported by a local public health institute in Japan (Figure S4, the blue-colored data).31 The viral loads measured in the clinical specimens were from middle to high levels. The presence of asymptomatic patients with viral loads of 104 TCID50/mL is a serious epidemiological concern.32 We estimated that the viral load required for SARS-CoV-2 transmission in a clinical specimen would be at least 104.3 TCID50/mL (108.1/103.8 = 104.3), as calculated with a transmissible level of 108.1 copies27 and a 103.8-fold difference between TCID50 titers and copy numbers. Using our MALDI-ToF MS-based diagnostic method, we detected SARS-CoV-2-specific peptides in clinical specimens with viral loads of 103.9–106.3 TCID50/mL (Table 2). This suggested that our method detected SARS-CoV-2 NP-derived peptides from contagious COVID-19 patients.

Mass Shift of a NP-Derived Peptide by an Amino Acid Mutation

The amino acid sequence of the NP-derived peptide at m/z 2060 was NPANNAAIVLQLPQGTTLPK, and the signal of the peptide was observed at m/z 2060.1413 in the MALDI-ToF MS chromatogram of ID 6 (Figure S5A). In the results of ID 1, ID 2, ID 4, ID 7, ID 8, and IDs 11–19, the signals of the peptide were also observed (Table 2), and the accurate observed mass of the peptide was between m/z 2060.1202 and m/z 2060.1481. Instead of the signal of the peptide at m/z 2060, those of m/z 2076.1793 (measured accurate mass of 2075.1720) and 2076.1892 (measured accurate mass of 2075.1819) were observed in the MALDI-ToF MS spectra of IDs 3 and 10, respectively (Figure S5B and C). The differences in mass between the NP-derived peptide at m/z 2060 (calculated exact mass of 2059.1426), and the unknown peptides were 16.0294 (ID 3) and 16.0393 (ID 10). These values approximately correspond to the difference in mass (16.0313) between proline (calculated exact mass of 115.0633) and leucine (calculated exact mass of 131.0946). There were three proline residues n the amino acid sequence of the NP-derived peptide at m/z 2060, and one of them might have been changed to leucine. Nucleotide sequences of RNA of the NP gene were determined to sequence-type the SARS-CoV-2 strains in the nasopharyngeal swab specimens of IDs 3, 6, and 10 in this study. Nucleotide sequence analysis showed that a missense mutation (452 C to U), which caused a P151L mutation, occurred in nucleotide sequences of the gene-encoding NP in both the ID 3 and ID 10 specimens compared with a downloaded sequence of the NP gene from GenBank (accession no. NC045512). The amino acid sequences of the variant peptides from ID 3 and ID 10 were determined as NLANNAAIVLQLPQGTTLPK. The NP-derived peptides are frequently used as target molecules for the MS-based detection of SARS-CoV-2, and four out of the seven target peptides in our method were suggested as good candidates for MS analysis.33 Since December 2020, the appearance of SARS-CoV-2 variants has been reported, and 20 mutations were found in the NP of SARS-CoV-2 isolated from Indian COVID-19 patients.34 The LC-MS/MS method of detecting some NP-derived peptides by multiple reaction monitoring can possibly miss the peptide signal if an amino acid mutation occurs in the targeted peptide. Although LC-Orbitrap-MS and LC-Q-ToF MS analyses may be able to detect mutated peptides,35 the change in retention times causes the peptides to be missed. In our MALDI-ToF MS-based method, the signal of the mutated peptide can be detected even if the peptide mass is shifted by an amino acid mutation, and the pattern of the amino acid mutation can be predicted without RNA sequence analysis. By adding the information on the mutated peptide mass to the detection targets, the SARS-CoV-2 variants can easily be found in the next test. In this way, the method developed in this study is quite suitable for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 variants, which are now increasingly prevalent.

Conclusions

Preventing the spread of infection and curbing the COVID-19 pandemic will require high-throughput diagnostics of multiple specimens. In this study, a method to purify SARS-CoV-2 particles in a nasopharyngeal swab eluate and the extract NP was developed. The purification step is straightforward and suitable for multisample processing. We successfully detected peptides derived from the SARS-CoV-2 NP in nasopharyngeal swab specimens from COVID-19 patients. Nontargeted analysis by MALDI-ToF MS enables the detection of unknown peptides derived from the virus variant. The advantages and disadvantages of RT-PCR and MALDI-ToF MS methods are listed in Table S2. The MS method has great advantages in operability, time for detection, and cost. Although the sensitivity of MALDI-ToF MS is inferior to that of RT-PCR, the novel MALDI-ToF MS-based diagnostics of COVID-19 developed in this study can detect contagious patients, allowing the appropriate isolation of patients. We believe this method can contribute to preventing the continued spread of SARS-CoV-2.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Dr. Takako Misaki, Kawasaki City Institute for Public Health, for collecting nasopharyngeal swabs from volunteers. We thank Dr. Masanori Katsumi, Sendai City Institute of Public Health, for providing the published data of virus titers and RT-PCR copies.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.analchem.1c04328.

Analysis of proteins from inactivated SARS-CoV-2; standard curves for the calculation of the SARS-CoV-2 copy number; MALDI-ToF MS spectra; correlation between SARS-CoV-2 copy numbers and infectious titers; list of the observed m/z, position, and sequence of 20 peptides derived from the nucleocapsid phosphoprotein; and advantages and disadvantages of RT-PCR and MALDI-ToF MS methods for COVID-19 diagnosis (PDF)

Author Contributions

○ These authors contributed equally. T.Y. and Y.H.-K. designed the study. T.Y., K.H., S.H., K.O., T.O., M.W., and Y.H.-K. developed the technique and carried out the experiments. T.Y., K.H., S.H., K.O., T.O., M.W., S.A., and Y.H.-K. analyzed the data and prepared the manuscript. S.T., H.M., T.T., T.M., Y.O., R.K., and Y.S. provided reagents and technical support. Y.G. supervised the project. Y.G. and Y.H.-K. provided funding.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- WHO Team, Public Health Laboratory Strenghtening . Laboratory testing for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in suspected human cases; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/10665-331501 (accessed 2021-01-13).

- Pujadas E.; Ibeh N.; Hernandez M. M.; Waluszko A.; Sidorenko T.; Flores V.; Shiffrin B.; Chiu N.; Young-Francois A.; Nowak M. D.; et al. Comparison of SARS-CoV-2 detection from nasopharyngeal swab samples by the Roche cobas 6800 SARS-CoV-2 test and a laboratory-developed real-time RT-PCR test. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 1695–1698. 10.1002/jmv.25988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman J. A.; Pepper G.; Naccache S. N.; Huang M.-L.; Jerome K. R.; Greninger A. L. Comparison of commercially available and laboratory-developed assays for in vitro detection of SARS-CoV-2 in clinical laboratories. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2020, 58, e00821-20. 10.1128/JCM.00821-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson T.; Spencer E. A.; Brassey J.; Heneghan C. Viral cultures for COVID-19 infectious potential assessment: A systematic review. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, e3884. 10.1093/cid/ciaa1764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihling C.; Tanzler D.; Hagemann S.; Kehlen A.; Huttelmaier S.; Arlt C.; Sinz A. Mass Spectrometric Identification of SARS-CoV-2 Proteins from Gargle Solution Samples of COVID-19 Patients. J. Proteome Res. 2020, 19, 4389–4392. 10.1021/acs.jproteome.0c00280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaev E. N.; Indeykina M. I.; Brzhozovskiy A. G.; Bugrova A. E.; Kononikhin A. S.; Starodubtseva N. L.; Petrotchenko E. V.; Kovalev G. I.; Borchers C. H.; Sukhikh G. T. Mass-Spectrometric Detection of SARS-CoV-2 Virus in Scrapings of the Epithelium of the Nasopharynx of Infected Patients via Nucleocapsid N Protein. J. Proteome Res. 2020, 19, 4393–4397. 10.1021/acs.jproteome.0c00412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouveia D.; Miotello G.; Gallais F.; Gaillard J.-C.; Debroas S.; Bellanger L.; Lavigne J.-P.; Sotto A.; Grenga L.; Pible O.; et al. Proteotyping SARS-CoV-2 Virus from Nasopharyngeal Swabs: A Proof-of-Concept Focused on a 3 min Mass Spectrometry Window. J. Proteome Res. 2020, 19, 4407–4416. 10.1021/acs.jproteome.0c00535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardozo K. H. M.; Lebkuchen A.; Okai G. G.; Schuch R. A.; Viana L. G.; Olive A. N.; Lazari C. d. S.; Fraga A. M.; Granato C. F. H.; Pintao M. C. T.; et al. Establishing a mass spectrometry-based system for rapid detection of SARS-CoV-2 in large clinical sample cohorts. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 6201. 10.1038/s41467-020-19925-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangalaparthi K. K.; Chavan S.; Madugundu A. K.; Renuse S.; Vanderboom P. M.; Maus A. D.; Kemp J.; Kipp B. R.; Grebe S. K.; Singh R. J.; Pandey A. A SISCAPA-based approach for detection of SARS-CoV-2 viral antigens from clinical samples. Clin. Proteomics 2021, 18, 25. 10.1186/s12014-021-09331-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renuse S.; Vanderboom P. M.; Maus A. D.; Kemp J. V.; Gurtner K. M.; Madugundu A. K.; Chavan S.; Peterson J. A.; Madden B. J.; Mangalaparthi K. K.; Mun D. G.; Singh S.; Kipp B. R.; Dasari S.; Singh R. J.; Grebe S. K.; Pandey A. A mass spectrometry-based targeted assay for detection of SARS-CoV-2 antigen from clinical specimens. EBioMedicine 2021, 69, 103465. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2021.103465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchida S.; Umemura H.; Nakayama T. Current Status of Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization-Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) in Clinical Diagnostic Microbiology. Molecules 2020, 25, 4775. 10.3390/molecules25204775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkendorf L. S.; Bowles E.; Buil J. B.; van der Lee H. A. L.; Posteraro B.; Sanguinetti M.; Verweij P. E. Update on Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization-Time of Flight Mass Spectrometry Identification of Filamentous Fungi. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2020, 58, e01263-20. 10.1128/JCM.01263-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J. J.; Falk B.; Fenselau C.; Jackman J.; Ezzell J. Viral characterization by direct analysis of capsid proteins. Anal. Chem. 1998, 70, 3863–3867. 10.1021/ac9802372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderaro A.; Arcangeletti M. C.; Rodighiero I.; Buttrini M.; Montecchini S.; Simone R. V.; Medici M. C.; Chezzi C.; De Conto F. Identification of different respiratory viruses, after a cell culture step, by matrix assisted laser desorption/ionization time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS). Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 36082. 10.1038/srep36082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krokhin O.; Li Y.; Andonov A.; Feldmann H.; Flick R.; Jones S.; Stroeher U.; Bastien N.; Dasuri K. V.; Cheng K.; et al. Mass spectrometric characterization of proteins from the SARS virus: A preliminary report. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2003, 2, 346–356. 10.1074/mcp.M300048-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iles R. K.; Zmuidinaite R.; Iles J. K.; Carnell G.; Sampson A.; Heeney J. L. Development of a Clinical MALDI-ToF Mass Spectrometry Assay for SARS-CoV-2: Rational Design and Multi-Disciplinary Team Work. Diagnostics (Basel) 2020, 10, 746. 10.3390/diagnostics10100746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dollman N. L.; Griffin J. H.; Downard K. M. Detection, Mapping, and Proteotyping of SARS-CoV-2 Coronavirus with High Resolution Mass Spectrometry. ACS Infec. Dis. 2020, 6, 3269–3276. 10.1021/acsinfecdis.0c00664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachtigall F. M.; Pereira A.; Trofymchuk O. S.; Santos L. S. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in nasal swabs using MALDI-MS. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 1168–1173. 10.1038/s41587-020-0644-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocca M. F.; Zintgraff J. C.; Dattero M. E.; Santos L. S.; Ledesma M.; Vay C.; Prieto M.; Benedetti E.; Avaro M.; Russo M.; et al. A combined approach of MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry and multivariate analysis as a potential tool for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 virus in nasopharyngeal swabs. J. Virol. Methods 2020, 286, 113991. 10.1016/j.jviromet.2020.113991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmud I.; Garrett T. J. Mass spectrometry techniques in emerging pathogens studies: COVID-19 perspectives. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2020, 31, 2013–2024. 10.1021/jasms.0c00238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuyama S.; Nao N.; Shirato K.; Kawase M.; Saito S.; Takayama I.; Nagata N.; Sekizuka T.; Katoh H.; Kato F.; et al. Enhanced isolation of SARS-CoV-2 by TMPRSS2- expressing cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2020, 117, 7001–7003. 10.1073/pnas.2002589117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Infectious Diseases. Manual for the Detection of Pathogen 2019-nCoV Ver.2.6.; National Institute of Infectious Diseases: Sinjuku, Japan, 2020. https://www.niid.go.jp/niid/images/epi/corona/2019-nCoVmanual20200217-en.pdf.

- Widdicombe J. Relationships among the composition of mucus, epithelial lining liquid, and adhesion of microorganisms. Am. J. Respir. 1995, 151, 2088–2093. 10.1164/ajrccm.151.6.7767562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestola P.; Martins D. L.; Peixoto C.; Roederstein S.; Schleuss T.; Alves P. M.; Mota J. P.; Carrondo M. J. Evaluation of novel large cut-off ultrafiltration membranes for adenovirus serotype 5 (Ad5) concentration. PLoS One 2014, 9, e115802. 10.1371/journal.pone.0115802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Y.; Zhao L.; Imperiale M. J.; Wigginton K. R. Integrated cell culture-mass spectrometry method for infectious human virus monitoring. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2019, 6, 407–412. 10.1021/acs.estlett.9b00226. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scheller C.; Krebs F.; Minkner R.; Astner I.; Gil-Moles M.; Wätzig H. Physicochemical properties of SARS-CoV-2 for drug targeting, virus inactivation and attenuation, vaccine formulation and quality control. Electrophoresis 2020, 41, 1137–1151. 10.1002/elps.202000121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyal A.; Reeves D. B.; Cardozo-Ojeda E. F.; Schiffer J. T.; Mayer B. T. Viral load and contact heterogeneity predict sars-cov-2 transmission and super-spreading events. Elife 2021, 10, e63537. 10.7554/eLife.63537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wölfel R.; Corman V. M.; Guggemos W.; Seilmaier M.; Zange S.; Müller M. A.; Niemeyer D.; Jones T. C.; Vollmar P.; Rothe C.; Hoelscher M.; Bleicker T.; Brünink S.; Schneider J.; Ehmann R.; Zwirglmaier K.; Drosten C.; Wendtner C. Virological assessment of hospitalized patients with COVID-2019. Nature 2020, 581, 465–469. 10.1038/s41586-020-2196-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Kampen J. J. A.; van de Vijver D. A. M. C.; Fraaij P. L. A.; Haagmans B. L.; Lamers M. M.; Okba N.; van den Akker J. P. C.; Endeman H.; Gommers D. A. M. P. J.; Cornelissen J. J.; et al. Duration and key determinants of infectious virus shedding in hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19). Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 267. 10.1038/s41467-020-20568-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossegesse M.; Leupold P.; Doellinger J.; Schaade L.; Nitsche A. Inactivation of Coronaviruses during Sample Preparation for Proteomics Experiments. J. Proteome Res. 2021, 20, 4598–4602. 10.1021/acs.jproteome.1c00320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsumi M.; Yamada K.; Matsubara H.; Narita M.; Kawamura K.; Tamura S.; Chida K.; Omori E.; Oshita M.; Murakami M.; Ishida H.; Karino M.; Aihara A. Consideration of SARS-CoV-2 virus copy count and virus titer in specimen. Infectious Agents Surveillance Report 2021, 42, 22–24. [Google Scholar]

- Wakatsuki A.; Tanizawa A.; Tokoi Y.; Sao T.; Kawamata S.; Kobayashi M.; Kaneko J.; Nagaya M.; Ishioka M. About infectious viral load and epidemiology of new coronavirus positive person-Utsunomiya City. Infectious Agents Surveillance Report 2021, 42, 35–36. [Google Scholar]

- Gouveia D.; Grenga L.; Gaillard J. C.; Gallais F.; Bellanger L.; Pible O.; Armengaud J. Shortlisting SARS-CoV-2 Peptides for Targeted Studies from Experimental Data-Dependent Acquisition Tandem Mass Spectrometry Data. Proteomics 2020, 20, 2000107. 10.1002/pmic.202000107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azad G. K. The molecular assessment of SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid Phosphoprotein variants among Indian isolates. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06167. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallais F.; Pible O.; Gaillard J. C.; Debroas S.; Batina H.; Ruat S.; Sandron F.; Delafoy D.; Gerber Z.; Olaso R.; Gas F.; Bellanger L.; Deleuze J. F.; Grenga L.; Armengaud J. Heterogeneity of SARS-CoV-2 virus produced in cell culture revealed by shotgun proteomics and supported by genome sequencing. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2021, 413, 7265. 10.1007/s00216-021-03401-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.