ABSTRACT

Background

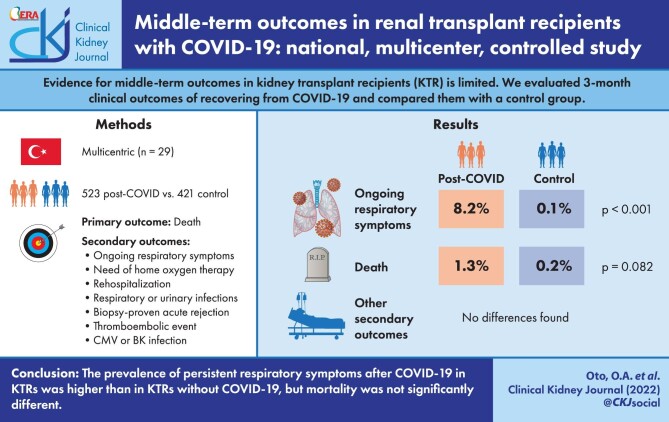

In this study, we evaluated 3-month clinical outcomes of kidney transplant recipients (KTR) recovering from COVID-19 and compared them with a control group.

Method

The primary endpoint was death in the third month. Secondary endpoints were ongoing respiratory symptoms, need for home oxygen therapy, rehospitalization for any reason, lower respiratory tract infection, urinary tract infection, biopsy-proven acute rejection, venous/arterial thromboembolic event, cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection/disease and BK viruria/viremia at 3 months.

Results

A total of 944 KTR from 29 different centers were included in this study (523 patients in the COVID-19 group; 421 patients in the control group). The mean age was 46 ± 12 years (interquartile range 37–55) and 532 (56.4%) of them were male. Total number of deaths was 8 [7 (1.3%) in COVID-19 group, 1 (0.2%) in control group; P = 0.082]. The proportion of patients with ongoing respiratory symptoms [43 (8.2%) versus 4 (1.0%); P < 0.001] was statistically significantly higher in the COVID-19 group compared with the control group. There was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of other secondary endpoints.

Conclusion

The prevalence of ongoing respiratory symptoms increased in the first 3 months post-COVID in KTRs who have recovered from COVID-19, but mortality was not significantly different.

Keywords: COVID-19, kidney transplantation, mortality, outcome, registry

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

INTRODUCTION

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has rapidly turned into a global pandemic after emerging in China in December 2019. It has been shown that approximately 20% of COVID-19 patients have moderate to severe clinical manifestations and 5% progress to critical illness [1]. Solid-organ transplant recipients have an increased vulnerability due to chronic immunosuppression and concomitant comorbidities, and the overall clinical course is worse than that of the general population [2–4]. Similarly, mortality rates in kidney transplant recipients (KTRs) were reported to be higher than in non-transplant patient groups [5, 6].

KTR may have different complications from non-transplant patient groups in the post-disease period. In KTRs that survive COVID-19, graft functions may be adversely affected by ischemic, inflammatory and nephrotoxic damage during the disease process. In addition, KTRs with COVID-19 are at higher immunological risk in the course of the disease due to drug and dose changes in immunosuppressive regimens, transfusion of blood products and virus-related immunomodulation [7].

Evidence for middle-term outcomes in KTRs recovering from COVID-19 is very limited. Therefore, in this nationwide multicenter retrospective observational study, we included a cohort of KTRs after recovery from COVID-19 with at least 3 months of follow-up and with an aim to identify the clinical outcomes and to compare them with the control group.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This retrospective cohort study, which was carried out following the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement [8], was approved by the Ethics Committee of Health Sciences University Haseki Training and Research Hospital (Number: 255–2020).

Population and setting

This multicenter study included KTRs aged 18 years and older who recovered from confirmed COVID-19. Recovery from COVID-19 was defined as no symptoms or presence of mild symptoms and/or a negative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test at the end of 14 days after diagnosis. A control group was also formed from KTR patients in the same center who did not have COVID-19. To select the control group, we included the next KTR patient without COVID-19 who was transplanted at the same center and on similar dates as KTR with COVID-19. We have created a web-based database to collect detailed national data on KTR patients with COVID-19, which was supported by the Turkish Society of Nephrology. The data of patients enrolled in the database between 15 March 2021 and 11 June 2021 were included in this study. We only included patients whose diagnosis of COVID-19 was confirmed by a nasopharyngeal swab positive reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test. Patients in the active period of COVID-19 who were still positive for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) RT-PCR and/or still receiving antiviral therapy for COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR negative COVID-19 patients and patients who lack outcome data were excluded.

Measurements and definitions

We recorded demographic data, reported comorbidities, non-immunosuppressive medications, primary kidney diseases, body mass index (BMI), the data regarding transplantation (donor type, duration of transplantation, immunosuppressive medication), COVID-19-related symptoms, complications during the treatment [need for intensive care and renal replacement therapy (RRT), presence of acute kidney injury (AKI)], the COVID-19 treatment information and treatment changes. We collected data for laboratory tests [hemogram, serum creatinine, electrolytes, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), albumin, C-reactive protein (CRP), ferritin, urinalysis, quantitative proteinuria] at the last routine control before the development of COVID-19 and during the enrollment. The same laboratory tests were also performed in the control group. COVID-19 severity was classified according to the suggestions in our national guideline [9]. The clinical severity of COVID-19 was defined based on the clinical presentation of COVID-19 at hospital admission and divided into four categories. 1—Mild disease: patients without shortness of breath, or any signs of viral pneumonia on chest computed tomography (CT). 2—Moderate disease: patients with symptoms such as fever and cough, shortness of breath and viral pneumonia in chest CT. 3—Severe disease: patients who need oxygen support at admission. 4—Critical disease: patients who are hypoxic at admission (arterial oxygen saturation <90%) and require close follow-up and/or need an intensive care unit (ICU). AKI was defined by the following criteria determined by Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guidelines [10]: increase in serum creatinine ≥0.3 mg/dL (≥26.5 μmol/L) within 48 h or increase in serum creatinine to > 1.5 times the baseline creatinine levels within 7 days.

Follow-up and outcome

The primary endpoint in the study was death in the third month. The secondary endpoints were ongoing respiratory symptoms, need for home oxygen therapy, rehospitalization for any reason, lower respiratory tract infection, urinary system infection, biopsy-proven acute rejection, venous/arterial thromboembolic event, cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection/disease BK viruria/viremia. Persistent cough and/or shortness of breath were defined as ongoing respiratory symptoms. For the control group, primary and secondary endpoints were also questioned during the same period (3 months).

Statistical analyses

IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for statistical analysis. We used visual methods (histograms and probability plots) and Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests to decide the normality of the variables. For descriptive statistics, we used numbers and percentages for categorical variables and median and interquartile ranges (25–75%) for numerical variables. We used the Chi-squared test for two- or multiple-group comparisons of categorical variables. Independent t-test or Mann–Whitney U test, if appropriate, was used for comparison of numerical variables. Analysis of variance test was used for numerical variables with normal distribution and Kruskal–Wallis test was used for numerical variables that did not show normal distribution. We used the Bonferroni corrected Mann–Whitney U test for subgroup analyses of variables that did not show normal distribution in post hoc analyses, and the Bonferroni corrected Chi-squared test for subgroup analyses of categorical variables. P < 0.05 was considered as the significance level.

RESULTS

Demographic, clinical and laboratory characteristics of groups

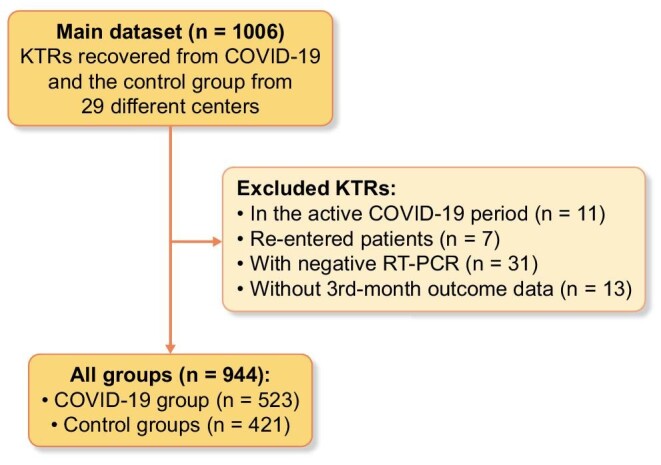

There were a total of 1006 patients in the raw data; 11 patients in the active COVID-19 period, 7 re-entered patients, 31 patients with negative RT-PCR and 13 patients without third month outcome data were excluded. A total of 944 (523 COVID-19 patients, 421 controls) KTRs from 29 different centers were included in the study (Figure 1). The mean ± SD age was 46 ± 12 years, the male/female ratio was 532/412 (56.4/43.6%). Age, gender, immunosuppressive medications, other medications (antihypertensive, antidiabetics, etc.), smoking habits, transplantation durations, donor type and other baseline parameters were generally similar in both groups (Table 1). However, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) was significantly more frequent in the COVID-19 group compared with the control group (3.8% versus 1.4%, respectively, P = 0.026). Compared with the control group, in the COVID-19 group; BMI, serum creatinine, amount of proteinuria, and ferritin, CRP, LDH, AST and ALT levels were significantly higher, whereas serum albumin and hemoglobin levels, and leukocyte and lymphocyte counts were significantly lower (Table 1). Other comorbidities and medication data of the study groups are shown in Supplementary data, Table S2.

FIGURE 1:

Flowchart of the study. KTR, kidney transplant recipient; RT-PCR, reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics, lab tests, medication and follow-up parameters of the study groups

| All patientsN: 944 | COVID-19 groupN: 523 | Control groupN: 421 | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 46.0 ± 12.0 | 45.0 ± 12.0 | 46.0 ± 12.0 | 0.726 | |

| Gender, n/N (%)a | Male | 532/944 (56.4) | 303/523(57.9) | 229/421 (54.4) | 0.276 |

| Smoking status, n (%) | Never smoked | 621/885 (70.2) | 339/494 (68.6) | 282/391 (72.1) | 0.410 |

| Current smoker | 25/885 (2.8) | 13/494 (2.6) | 12/391 (3.1) | ||

| Former smoked | 239/885 (27.0) | 142/494 (28.7) | 97/391 (24.8) | ||

| Tx duration, years, median (IQR) | 6.0 (3.0–11.1) | 6.6 (3.0–11.2) | 6.0 (3.0–11.0) | 0.414 | |

| Donor type, n (%) | Living non-related | 90/944 (9.5) | 50/523 (9.6) | 40/421 (9.5) | 0.068 |

| Living related | 638/944 (67.6) | 368/523 (70.4) | 270/421 (64.1) | ||

| Deceased | 216/944 (22.9) | 105/523 (20.1) | 111/421 (26.4) | ||

| BMI kg/m2, median (IQR) | 25.7 (23.8–28.1) | 25.9 (23.7–28.4) | 25.43 (22.9–27.9) | 0.019 | |

| Systolic BP, mmHg, median (IQR) | 130.0 (120.0–135.0) | 130.0 (120.0–133.0) | 130.0 (120.0–135.0) | 0.464 | |

| Diastolic BP, mmHg, median (IQR) | 80.0 (70.0–85.0) | 80.0 (70.0–85.0) | 80.0 (74.0–85.0) | 0.488 | |

| Creatinine, mg/dl, median (IQR) | 1.3 (1.0–1.6) | 1.3 (1.0–1.7) | 1.2 (1.0–1.5) | <0.001 | |

| AST, U/L, median (IQR) | 17.0 (14.0–22.0) | 17.5 (14.0–24.0) | 17.0 (13.0–21.0) | 0.018 | |

| ALT, U/L, median (IQR) | 17.0 (12.0–22.0) | 17.0 (13.0–24.0) | 16.0 (12.0–21.0) | 0.039 | |

| LDH, U/L, median (IQR) | 200.0 (163.0–247.0) | 206.0 (166.0–254.0) | 193.0 (160.0–236.0) | 0.014 | |

| Albumin, g/dL, median (IQR) | 4.2 (4.0–4.5) | 4.2 (3.9–4.5) | 4.3 (4.0–4.6) | 0.001 | |

| Ferritin, ng/mL, median (IQR) | 120.0 (43.1–295.9) | 136.0 (5.0–327.5) | 98.5 (38.0–252.0) | 0.022 | |

| CRP, mg/L, median (IQR) | 3.9 (2.1–10.0) | 15.0 (2.0–16.2) | 3.1 (1.7–5.6) | <0.001 | |

| Leukocyte counts/mm3, median (IQR) | 7400 (5895–9255) | 7200 (5600–8903) | 7600 (6100–9480) | 0.008 | |

| Neutrophil counts/mm3, median (IQR) | 4640 (3540–5960) | 4600 (3500–5800) | 4700 (3600–6270) | 0.124 | |

| Lymphocyte counts (/mm3), median (IQR) | 1775 (1185–2375) | 1600(1100–2300) | 1900 (1340–2500) | <0.001 | |

| Proteinuria (mg/mg), median (IQR) | 228.1 (117.5–564.9) | 280.0 (127.5–700.7) | 188.2 (103.7–467.5) | 0.001 | |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL), median (IQR) | 12.9 (11.3–14.2) | 12.8 (11.1–14.0) | 13.0 (11.6–14.4) | 0.013 |

P-values presented from the Chi-squared test, Fisher's exact test, t-test or Mann–Whitney U test.

aCompared with female gender.

IQR, interquartile range; BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; CRP, C-reactive protein; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase.

Presentation, treatment regimes and complications of COVID-19 patients during the active period

The most common symptoms at admission were myalgia (68.0%) and cough (63.8%), followed by fever (63.7%) and dyspnea (38.0%). Most of the patients (66.0%) had a mild disease at the time of admission (Supplementary data, Table S1). The majority of the patients received favipiravir (87.5%) as antiviral treatment. A smaller subset of the patients also received tocilizumab (3.9%) or anakinra (3.1%). Almost none of the glucocorticoids (0.4%) were stopped during the active period of the disease, but the dose was temporarily increased in 43.6% of the patients. Most patients discontinued mycophenolic acid treatments (65.6%) (Supplementary data, Table S3). Chest CT revealed viral pneumonia findings in 72.9% of the COVID-19 patients. A total of 290 COVID-19 patients (55.4%) were hospitalized, 31 patients (10.7%) were followed in the ICU. Nine of 31 patients needed invasive mechanical ventilation. The length of stay in the hospital was 10 [interquartile range (IQR) 6–15] days. AKI was developed in 114 patients (39.4%) and RRT was required in 15 (5.2%) patients. SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR-positive reinfection was reported in 6 (1.2%) patients after a median of 42 (IQR 31–89) days. In the first month, the proportion of ongoing respiratory symptoms [93 (17.8%) versus 5 (1.2%), respectively; P < 0.001)] and the development of lower respiratory tract infection rates [36 (6.9%) versus 5 (1.2%), respectively; P < 0.001] were statistically significantly higher in the COVID-19 group compared with the control group. The CRP level and proteinuria were significantly higher, while the hemoglobin and albumin levels were significantly lower in the COVID-19 patient group than in the control group. Both groups were comparable in terms of creatinine levels (Supplementary data, Table S4).

Clinical and laboratory characteristics of groups according to primary and secondary outcomes

Table 2 shows the outcomes and biochemical parameters during 3 months of follow-up. The CRP level was significantly higher, while the hemoglobin level was significantly lower in the COVID-19 patient group compared with the control group in the third month. Both groups were comparable in terms of systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, creatinine levels, albumin levels and amount of proteinuria. More deaths occurred in the COVID-19 group compared with the control group, but the difference was not statistically significant [7 (1.3%) versus 1 (0.2%), respectively; P = 0.082]. The proportion of ongoing respiratory symptoms [43 (8.2%) versus 4 (1.0%), respectively; P < 0.001] was statistically significantly higher in the COVID-19 group. Although it did not reach statistical significance, a trend towards an increase in the development of lower respiratory tract infection was detected in the COVID-19 group compared with the control group (P = 0.05). There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups in terms of the need for home oxygen therapy, rehospitalization, urinary tract infection, acute rejection, venous/arterial thromboembolic event, CMV infection/disease or BK virus infection. When comparing the control group, the frequency of hypertension, BMI, creatinine, AST, ALT, LDH, ferritin, CRP and proteinuria was higher, whereas the serum albumin levels, lymphocyte and hemoglobin were lower in the inpatient group. (Supplementary data, Table S5).

Table 2.

Outcomes and biochemical parameters at 3 month follow-up

| All patients | COVID-19 patients | Control group | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Death, n/N (%) | 8/944 (0.8) | 7/523 (1.3) | 1/421 (0.2) | 0.082 |

| Ongoing respiratory symptoms, n/N (%) | 47/944 (5.0) | 43/523 (8.2) | 4/421 (1.0) | <0.001 |

| Need for home oxygen therapy, n/N (%) | 5/944 (0.5) | 5/523 (1.0) | 0/421 (0.0) | 0.069 |

| Re-hospitalization for any reason, n/N (%) | 71/944 (7.5) | 41/523 (7.8) | 30/421 (7.1) | 0.679 |

| Lower respiratory tract infection, n/N (%) | 12/944 (1.3) | 10/523 (1.9) | 2/421 (0.5) | 0.050 |

| Urinary tract infection, n/N (%) | 47/944 (5.0) | 26/523 (5.0) | 21/421 (5.0) | 0.991 |

| Acute rejection (biopsy proven), n/N (%) | 10/944 (1.1) | 6/523 (1.1) | 4/421 (1.0) | 1.000 |

| Venous or arterial thromboembolic event, n/N (%) | 5/944 (0.5) | 5/523 (1.0) | 0/421 (0.0) | 0.069 |

| CMV infection/disease, n/N (%) | 8/944 (0.8) | 6/523 (1.1) | 2/421 (0.5) | 0.310 |

| BK virus infection, n/N (%) | 13/944 (1.4) | 6/523 (1.1) | 7/421 (1.7) | 0.499 |

| Hematuria, n/N (%) | 40/369 (10.8) | 22/195 (11.3) | 18/174 (10.3) | 0.773 |

| Pyuria, n/N (%) | 65/368 (17.7) | 35/195 (17.9) | 30/173 (17.3) | 0.879 |

| BMI (kg/m2), median (IQR) | 25.6 (23.4–27.9) | 25.7 (24.1–28.3) | 25.5 (22.7–27.5) | 0.133 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg, median (IQR) | 130.0 (120.0–132.0) | 130.0 (120.0–132.0) | 130.0 (120.0–134.0) | 0.890 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg, median (IQR) | 80.0 (70.0–85.0) | 80.0 (70.0–84.0) | 80.0 (75.0–85.0) | 0.501 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL, median (IQR) | 1.3 (1.0–1.7) | 1.3 (1.0–1.7) | 1.2 (1.0–1.6) | 0.230 |

| Albumin, g/dL, median (IQR) | 4.2 (4.0–4.5) | 4.2 (3.9–4.5) | 4.2 (4.0–4.5) | 0.527 |

| CRP, mg/L, median (IQR) | 3.3 (2.0–6.0) | 4.1 (2.5–7.4) | 3.0 (2.0–5.0) | 0.021 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL, median (IQR) | 12.9 (11.4–14.2) | 12.8 (11.2–14.1) | 13.0 (11.7–14.4) | 0.005 |

| Proteinuria, mg/mg, median (IQR) | 234.0 (115.1–600.0) | 257.5 (115.0–616.0) | 201.5 (115.5–458.1) | 0.434 |

P-values presented from the Chi-squared test, Fisher's exact test, or Mann–Whitney U test.

IQR, interquartile range; BMI, body mass index; CMV, cytomegalovirus; CRP, C-reactive protein.

Clinical and laboratory characteristics according to mortality

Those who died had older age, severe COVID-19 clinic at the time of admission, needed hospitalization, required ICU, required RRT during the hospital follow-up period, required rehospitalization, ongoing respiratory symptoms, had lower respiratory infection and needed home oxygen therapy (Table 3). There was no statistically significant difference between the dead and the survivors in terms of donor type, transplantation duration, smoking habit, gender, CMV infection/disease, acute rejection, BK infection, venous/arterial thromboembolic event and urinary system infection.

Table 3.

Demographic and clinical parameters according to the survival status of all patients at 3 months

| TotalN: 944 | SurvivorsN: 936 | NonsurvivorsN: 8 | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study groups, n/N (%) | Control group | 421/944 (44.6) | 420/936 (44.9) | 1/8 (12.5) | 0.082 |

| COVID-19 group | 523/944 (55.4) | 516/936 (55.1) | 7/8 (87.5) | ||

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 46.0 (37.0–55.0) | 46.0 (36.0–55.0) | 59.0 (54.0–65.0) | 0.001 | |

| Gender, n/N (%) | Male | 532/944 (56.4) | 527/936 (56.3) | 5/8 (62.5) | 1.000 |

| Smoking, n/N (%) | Never smoked | 621/885 (70.2) | 616/877 (70.2) | 5/8 (62.5) | 0.758 |

| Current smoker | 25/885 (2.8) | 25/877 (2.9) | 0/8 (0.0) | ||

| Former smoker | 239/885 (2.7) | 236/877 (26.9) | 3/8 (37.5) | ||

| Tx duration, years, median (IQR) | 6.0 (3.0–11.0) | 6.0 (3.0–11.0) | 8.0 (5.0–10.0) | 0.536 | |

| Donor type, n/N (%) | Living non-related | 90/944(9.5) | 88/936 (9.4) | 2/8 (25.0) | 0.071 |

| Living related | 638/944 (67.6) | 635/936 (67.8) | 3/8 (37.5) | ||

| Deceased | 216/944 (22.9) | 213/936 (22.8) | 3/8 (37.5) | ||

| Pneumonia finding on CT, n/N (%) | 317/435 (72.9) | 310/428 (72.4) | 7/7 (100.0) | 0.197 | |

| Clinical presentation, n/N (%) | Mild disease | 345/523 (66.0) | 344/516 (66.6) | 1/7 (14.4) | <0.001 |

| Moderate disease | 157/523 (30.0) | 155/516 (30.0) | 2/7 (28.6) | ||

| Severe-critical disease | 21/523(4.0) | 17/516 (3.3) | 4/7 (57.1) | ||

| Type of treatment, n/N (%) | Inpatient | 290/523 (55.4) | 283/516 (54.8) | 7/7 (100.0) | 0.019 |

| ICU admission, n/N (%) | 31/290 (10.7) | 25/283 (8.8) | 6/7 (85.7) | <0.001 | |

| Outcomes at 3 month follow-up, n/N (%) | Ongoing respiratory symptoms | 47/944 (5.0) | 42/936 (4.5) | 5/8 (62.5) | <0.001 |

| Re-hospitalization | 5/944 (0.5) | 2/936 (0.2) | 3/8 (37.5) | <0.001 | |

| Need for home oxygen therapy | 71/944 (7.5) | 66/936 (7.1) | 5/8 (62.5) | <0.001 | |

| Lower respiratory tract infection | 12/944 (1.3) | 7/936 (0.7) | 5/8 (62.5) | <0.001 | |

| Urinary tract infection | 47/944 (5.0) | 46/936 (4.9) | 1/8 (12.5) | 1.000 | |

| Acute rejection (biopsy proven) | 10/944 (1.1) | 9/936 (1.0) | 1/8 (12.5) | 0.082 | |

| Venous or arterial thromboembolic event | 5/944 (0.5) | 5/936 (0.5) | 0/8 (0.0) | 1.000 | |

| CMV infection/disease | 8/944 (0.8) | 7/936 (0.7) | 1/8 (12.5) | 0.066 | |

| BK virus infection | 13/944 (1.4) | 13/936 (1.4) | 0/8 (0.0) | 1.000 | |

P-values presented from the Chi-squared test Fisher's exact test, or Mann–Whitney U test.

IQR, interquartile range; CMV, cytomegalovirus; ICU, intensive care unit; CT, computed tomography; Tx, transplantation.

DISCUSSION

In this multicenter, retrospective, controlled follow-up study of KTRs recovering from COVID-19, although it did not reach statistical significance, the number of patients who died in the post-COVID era was higher than in the control group. We found persistence of respiratory symptoms without increased risk of acute rejection, BK and CMV infection, thromboembolic event or urinary tract infection. As far as we know, this is the first controlled follow-up study in KTRs who have recovered from COVID-19.

There are growing concerns about possible long-term sequelae of COVID-19 [11]. The inflammatory damage and severe tissue sequelae characteristic of particularly severe forms of the disease may affect multiple organ systems. Some patients who recovered from COVID-19 develop persistent or new symptoms lasting weeks or months. This condition is defined as ‘long COVID’, ‘Long Haulers’ or ‘Post COVID syndrome’ [12].

Several publications showed that COVID-19 causes significant pulmonary sequelae. Although it was not a controlled study and was not conducted specifically for the transplant population, in a follow-up study evaluating recovery from COVID-19 in 478 patients, the incidence of new-onset dyspnea was 16%. Also, 4 months after hospitalization for COVID-19, a proportion of patients developed previously unreported symptoms and lung scan abnormalities were common in this group [13]. Similarly, in another study, dyspnea, chest pain and cough were found in 37, 16 and 14% of patients between 3 weeks and 3 months, after discharge of hospital admission by COVID-19, respectively [14]. In our patient group, the rate of patients with persistent respiratory symptoms was lower than in the literature. This may be related to the fact that many of our patients had mild COVID-19 or our patients were relatively young. The mean age was 60.9 ± 16.1 in the study of Morin et al. and between 49 ± 15 and 63.2 ± 15.7 in the review of Cares-Marambio et al. [13, 14]. However, the mean age in our study was 46.0 ± 12.0 years. In addition, we found that death was more common in the patient group whose respiratory symptoms continued. However, we do not have enough evidence to state that the deaths are related to COVID-19. This result may be an important finding emphasizing that the patient group with persistent respiratory symptoms should be followed closely after discharge.

It is unclear whether changes in immunosuppressive therapy during active COVID-19 or possible persistent inflammation during the recovery period are associated with a higher risk of transplant complications such as rejection or infection.

There are several reports that SARS-CoV-2 infection could cause exhaustion of T cells and particularly CD8+ T cells, thus leading to viral replication [15, 16]. We did not detect an increase in the risk of CMV and BK viruria/viremia in our patient group after recovery from COVID-19. This may be related to the short follow-up period. It is unclear whether there will be an increase in the frequency of viral infections in the long term.

Numerous studies have shown evidence of COVID-19-related coagulopathy and an increased risk of arterial and venous thromboembolic events [17–20]. We did not detect a significant increase in thromboembolic phenomena. This may be related to the fact that most of the patients had a mild course of COVID-19.

In immunosuppressed hosts, comorbidities and medications may impair cellular and humoral immunity and limit viral clearance in COVID-19 as in other infections [21]. COVID-19 reinfections, which can sometimes be lethal, have been described in the literature [22]. We also detected reinfection in 1.2% of patients.

According to KDIGO guidelines, reduction of immunosuppressants in life-threatening infections in KTRs may be indicated [23]. Although these modifications raise concerns about the increased risk of acute rejection, studies that found no increased risk have been published [24]. Similar findings were found in a study of KTRs with COVID-19. In this study, the intensity and degree of reduction in immunosuppression were not associated with acute allograft rejection [25]. We also did not detect an increase in the risk of acute rejection, which is consistent with the literature. However, the short follow-up period should be considered while interpreting these data.

The results of our study should be evaluated according to their strengths and potential limitations. Among the strengths, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first multicenter, controlled follow-up study involving a large sample of KTRs who survived COVID-19. This study had several limitations. First, this investigation was a retrospective study. Second, simple randomization was used instead of systematic randomization when creating groups. Third, the cause of death of the patients who died was not clear. Fourth, etiological examination (radiological or functional tests) for lung pathologies causing respiratory symptoms was not performed. Fifth, the low number of patients and the low number of primary events were also potential limitations, so statistical significance might not have been determined despite the numerical difference. However, considering the chaotic environments during the pandemic period, these data can be considered close to real practical life data despite all the study's limitations.

In conclusion, the prevalence of persistent respiratory symptoms after COVID-19 in KTRs was higher than in KTRs without COVID-19, but mortality was not significantly different.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Ozgur Akin Oto, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Nephrology, Istanbul University Istanbul Faculty of Medicine, Istanbul, Turkey.

Savas Ozturk, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Nephrology, Istanbul University Istanbul Faculty of Medicine, Istanbul, Turkey.

Mustafa Arici, Department of Nephrology, Hacettepe University Faculty of Medicine, Ankara, Turkey.

Arzu Velioğlu, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Nephrology, Marmara University, School of Medicine, Istanbul, Turkey.

Belda Dursun, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Nephrology, Pamukkale University, Faculty of Medicine, Denizli, Turkey.

Nurana Guller, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Nephrology, Istanbul University Istanbul Faculty of Medicine, Istanbul, Turkey.

İdris Şahin, Department of Internal Medicine, Nephrology Division, Inonu University, Faculty of Medicine, Malatya, Turkey.

Zeynep Ebru Eser, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Nephrology, Mersin University, Mersin Faculty of Medicine, Mersin, Turkey.

Saime Paydaş, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Nephrology, Çukurova University Faculty of Medicine, Adana, Turkey.

Sinan Trabulus, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Nephrology, Istanbul University-Cerrahpasa, Cerrahpasa Medical Faculty, Istanbul, Turkey.

Sümeyra Koyuncu, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Nephrology, Erciyes University, Erciyes Faculty of Medicine, Kayseri, Turkey.

Murathan Uyar, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Nephrology, Yeni Yüzyıl University, Gaziosmanpaşa Hospital, Istanbul, Turkey.

Zeynep Ural, Department of İnternal Medicine, Division of Nephrology Gazi University, Faculty of Medicine, Ankara, Turkey.

Rezzan Eren Sadioğlu, Department of Nephrology, Ankara University School of Medicine, Ankara, Turkey.

Hamad Dheir, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Nephrology, Sakarya University Training and Research Hospital, Sakarya, Turkey.

Neriman Sıla Koç, Department of Nephrology, Hacettepe University Faculty of Medicine, Ankara, Turkey.

Hakan Özer, Division of Nephrology, Konya Necmettin Erbakan University, Meram Faculty of Medicine, Konya, Turkey.

Beyza Algül Durak, Department of Nephrology, Ankara Bilkent City Hospital, Ankara, Turkey.

Cuma Bülent Gül, Department of Nephrology, University of Health Sciences, Bursa Yuksek Ihtisas Training and Research Hospital, Istanbul, Turkey.

Umut Kasapoğlu, Department of Nephrology, University of Health Sciences, Bakirkoy Dr Sadi Konuk Training and Research Hospital, Istanbul, Turkey.

Ebru Gök Oğuz, Department of Nephrology, University of Health Sciences, Diskapi Yildirim Beyazit Education and Research Hospital, Ankara, Turkey.

Mehmet Tanrısev, Department of Nephrology, University of Health Sciences, Izmir Faculty of Medicine, Tepecik Training and Research Hospital, Izmir, Turkey.

Gülşah Şaşak Kuzgun, Department of Nephrology, Goztepe Prof Dr Suleyman Yalcin City Hospital, Istanbul, Turkey.

Safak Mirioglu, Division of Nephrology, Department of Internal Medicine, Bezmialem Vakif University School of Medicine, Istanbul, Turkey.

Erkan Dervişoğlu, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Nephrology, Kocaeli University, Faculty of Medicine, Kocaeli, Turkey.

Ertuğrul Erken, Department of Nephrology, Kahramanmaras Sutcu Imam University, Kahramanmaras, Turkey.

Numan Görgülü, Department of Nephrology, University of Health Sciences, Bagcilar Training and Research Hospital, Istanbul, Turkey.

Sultan Özkurt, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Nephrology, Eskişehir Osmangazi University, Faculty of Medicine, Eskişehir, Turkey.

Zeki Aydın, Department of Nephrology, University of Health Sciences, Darıca Farabi Training and Research Hospital, Darica, Turkey.

İlhan Kurultak, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Nephrology, Trakya University, Faculty of Medicine, Edirne, Turkey.

Melike Betül Öğütmen, Department of Nephrology, University of Health Sciences, Haydarpaşa Numune Training and Research Hospital, Istanbul, Turkey.

Serkan Bakırdöğen, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Nephrology, Canakkale Onsekiz Mart University, School of Medicine, Canakkale, Turkey.

Burcu Kaya, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Nephrology, Marmara University, School of Medicine, Istanbul, Turkey.

Serhat Karadağ, Department of Nephrology, University of Health Sciences, Haseki Training and Research Hospital, Istanbul, Turkey.

Memnune Sena Ulu, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Nephrology, Bahçeşehir University, Faculty of Medicine, Istanbul, Turkey.

Özkan Güngör, Department of Nephrology, Kahramanmaras Sutcu Imam University, Kahramanmaras, Turkey.

Elif Arı Bakır, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Nephrology University of Health Sciences, Kartal Training Hospital, Istanbul, Turkey.

Ali Rıza Odabaş, Department of Nephrology, University of Health Sciences, Sultan 2. Abdulhamid Han Training and Research Hospital, Istanbul, Turkey.

Nurhan Seyahi, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Nephrology, Istanbul University-Cerrahpasa, Cerrahpasa Medical Faculty, Istanbul, Turkey.

Alaattin Yıldız, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Nephrology, Istanbul University Istanbul Faculty of Medicine, Istanbul, Turkey.

Kenan Ateş, Department of Nephrology, Ankara University School of Medicine, Ankara, Turkey.

REFERENCES

- 1. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese center for disease control and prevention. JAMA 2020; 323: 1239–1242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Oltean M, Søfteland JM, Bagge Jet al. COVID-19 in kidney transplant recipients: a systematic review of the case series available three months into the pandemic. Infect Dis 2020; 52: 830–837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ravanan R, Callaghan CJ, Mumford Let al. SARS-CoV-2 infection and early mortality of waitlisted and solid organ transplant recipients in England: a national cohort study. Am J Transplant 2020; 20: 3008–3018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kates OS, Haydel BM, Florman SSet al. Coronavirus disease 2019 in solid organ transplant: a multicenter cohort study. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 73.11: e4090–e4099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Caillard S, Chavarot N, Francois Het al. Is COVID-19 infection more severe in kidney transplant recipients? Am J Transplant 2021; 21: 1295–1303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Oto OA, Ozturk S, Turgutalp Ket al. Predicting the outcome of COVID-19 infection in kidney transplant recipients. BMC Nephrol 2021; 22: 100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vanichanan J, Udomkarnjananun S, Avihingsanon Yet al. Common viral infections in kidney transplant recipients. Kidney Res Clin Pract 2018; 37: 323–337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DGet al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Int J Surg 2014; 12: 1500–1524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Guidance to COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2 Infection) (Study of Scientific Board) Republic of Turkey, Ministry of Health (published on 14 April 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kellum JA, Lameire N, Aspelin Pet al. Kidney disease: improving global outcomes (KDIGO) acute kidney injury work group. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. Kidney Int Suppl 2012; 2: 1–138 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wiersinga WJ, Rhodes A, Cheng ACet al. Pathophysiology, transmission, diagnosis, and treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a review. JAMA 2020; 324: 782–793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Raveendran AV, Jayadevan R, Sashidharan S. Long COVID: an overview. Diabetes Metab Syndr 2021; 15: 869–875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Morin L, Savale L, Pham Tet al. Four-month clinical status of a cohort of patients after hospitalization for COVID-19. JAMA 2021; 325: 1525–1534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cares-Marambio K, Montenegro-Jiménez Y, Torres-Castro Ret al. Prevalence of potential respiratory symptoms in survivors of hospital admission after coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chron Respir Dis 2021; 18: 14799731211002240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Masset C, Ville S, Halary Fet al. Resurgence of BK virus following COVID-19 in kidney transplant recipients. Transpl Infect Dis 2021; 23: e13465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vabret N, Britton GJ, Gruber Cet al. Immunology of COVID-19: current state of the science. Immunity 2020; 52: 910–941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cui S, Chen S, Li Xet al. Prevalence of venous thromboembolism in patients with severe novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost 2020; 18: 1421–1424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fogarty H, Townsend L, Ni Cheallaigh Cet al. COVID19 coagulopathy in Caucasian patients. Br J Haematol 2020; 189: 1044–1049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wichmann D, Sperhake JP, Lütgehetmann Met al. Autopsy findings and venous thromboembolism in patients with COVID-19: A Prospective Cohort Study Ann Intern Med 2020; 173: 268–277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhou F, Yu T, Du Ret al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2020; 395: 1054–1062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ling Y, Xu S-B, Lin Y-Xet al. Persistence and clearance of viral RNA in 2019 novel coronavirus disease rehabilitation patients. Chin Med J (Engl) 2020; 133: 1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ma BM, Hung IFN, Chan GCWet al. Case of “relapsing” COVID-19 in a kidney transplant recipient. Nephrology (Carlton) 2020; 25: 933–936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kasiske BL, Zeier MG, Chapman JRet al. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the care of kidney transplant recipients: a summary. Kidney Int 2010; 77: 299–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shih C-J, Tarng D-C, Yang W-Cet al. Immunosuppressant dose reduction and long-term rejection risk in renal transplant recipients with severe bacterial pneumonia. Singapore Med J 2014; 55: 372–377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Santeusanio AD, Menon MC, Liu Cet al. Influence of patient characteristics and immunosuppressant management on mortality in kidney transplant recipients hospitalized with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Clin Transplant 2021; 35: e14221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.