ABSTRACT

Background

Self-isolation is challenging and adherence is dependent on a range of psychological, social and economic factors. We aimed to identify the challenges experienced by contacts of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) cases to better target support and minimize the harms of self-isolation.

Methods

The Contact Adherence Behavioural Insights Study (CABINS) was a 15-minute telephone survey conducted with confirmed contacts of COVID-19 (N = 2027), identified through the NHS Wales Test Trace Protect (TTP) database.

Results

Younger people (aged 18–29 years) were three times more likely to report mental health concerns (adjusted odds ratio [aOR]: 3.16, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.05–4.86) and two times more likely to report loneliness (aOR: 1.96, CI: 1.37–2.81) compared to people aged over 60 years. Women were 1.5 times more likely to experience mental health concerns (aOR: 1.51, 95% CI: 1.20–1.92) compared to men. People with high levels of income precarity were eight times more likely to report financial challenges (aOR: 7.73, CI: 5.10–11.74) and three times more likely to report mental health concerns than their more financially secure counterparts (aOR: 3.08, CI: 2.22–4.28).

Conclusion

Self-isolation is particularly challenging for younger people, women and those with precarious incomes. Providing enhanced support is required to minimize the harms of self-isolation.

Keywords: challenges, COVID-19, financial stability, health inequalities, self-isolation

Introduction

Self-isolation of close contacts was a key measure to stop community spread of coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) across a number of countries.1 Between 28 September 2020 and 16 August 2021, in the UK, self-isolation was a legal requirement for confirmed contacts.2,3 In Wales, from 29 October 2021 only household contacts aged five or over of symptomatic cases must self-isolate until a negative polymerase chain reaction is returned.4

Although differences in service delivery existed across the UK,5–8 in each UK nation contact tracing of index cases was used to identify their close contacts who were then informed to self-isolate. In Wales, contact tracing was conducted through NHS Wales Test, Trace, Protect (TTP) by local contact tracing teams working in each of the 22 Local Authorities.6 TTP is supported by a national database that records details of all cases and their identified contacts who are successfully traced and informed to self-isolate.6

Studies report adherence to self-isolation between 11% and 86% in the UK.9–13 However, despite this variation in the levels of self-reported adherence, roughly 80% report experiencing challenges to adhering to the UK Government’s coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) related instructions.13 The most prevalent challenges reported were mental health concerns, physical health difficulties and changes in daily routine.13 Men and those aged 55 years or older are least likely to report challenges.13

Identifying and understanding the challenges faced during self-isolation is important to help inform, target and tailor the support needed both during the COVID-19 pandemic and to minimize harms of future infectious disease outbreaks. Our study aimed to identify the specific challenges experienced by population sub-groups to better develop and target the support needed to minimize potential health and economic harms of self-isolation for future infectious disease outbreaks.

Methods

Study design

The COVID-19 Contacts Adherence Behavioural Insights Survey (CABINS) was a mixed methods study of confirmed contacts of cases of COVID-19. CABINS included two rounds of a telephone survey followed by online focus groups with a sample of telephone survey participants. Round 1 was undertaken between 11 November and 1 December 2020 and Round 2 between 18 February and 23 March 2021. Here we report telephone survey data from both rounds of data collection.

Participants

Individuals were eligible for inclusion if they: (i) had been successfully contacted by TTP after forward contact tracing (There are two different types of contact tracing. Forward contact tracing is used to identify individuals who may have been infected by the index case. Backwards contact tracing is used to identify the setting or event or primary case who infected the index case (Endo et al., 2021). Due to capacity and nature of the pandemic, forward contact tracing has predominately been conducted with backwards contact tracing used in the context of outbreak control.) and informed to self-isolate; (ii) were a close contact of a confirmed case of COVID-19; (iii) were aged 18 years or over; (iv) resident in Wales; and (v) had completed their self-isolation period at the time of telephone survey. Contacts were excluded from the study if they were: (i) under the age of 18; (ii) currently self-isolating; (iii) not a resident in Wales; or (v) a contact of a case of COVID-19 who died.

We used the national TTP database to identify eligible participants who have been asked to self-isolate at two different time periods (n = 47 072). Round 1 was between 12 September 2020 and 23 October 2020, the day before the start of the Welsh ‘Firebreak’14 (n = 18 568). Round 2 was between 13 December and 15 January 2021 (n = 28 504). Due to changes in Government guidelines14 the legally required duration of self-isolation during Round 1 was 14 days, and during Round 2 was 10 days.15

Sampling

A target sample size of 1000 was set for each survey round. This threshold was set to enable a sufficient number of participants to enable sub-group analysis. Quota sampling was applied based on age and gender (combined) and Welsh Index of Multiple Deprivation (WIMD) quintile to ensure that the sample was representative of contacts informed to self-isolate during each period.

Recruitment

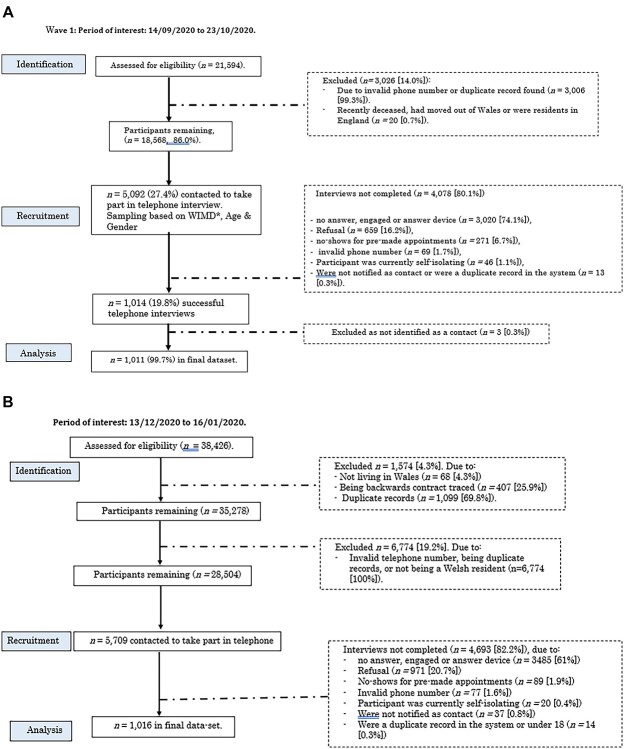

Figure 1 shows the study flowchart. Eligible participants were invited to participate in a 15-minute telephone interview. Bilingual interview was conducted in either Welsh or English, according to participant preference. We used an external market research company (Beaufort Research Limited) to recruit participants and collect data to ensure anonymity and minimize potential response bias if Public Health Wales had made initial contact with participants. Participants were approached for interview between 12 November and 1 December 2020 for those asked to self-isolate during Round 1 and between 18 February and 13 March 2021 for Round 2. Each respondent was contacted up to a maximum of seven times. Across both survey rounds, 47 072 contacts were eligible to participate; 10 801 (23.0%) were approached by telephonist and 2027 (18.8%) completed the telephone survey.

Fig. 1.

Study flowchart for both waves.

Measures

Challenges to self-isolation

Participants were asked to select from a list of challenges. In Round 1 this list included 15 options. Five additional options were added to Round 2, derived from data analysis on this question conducted after Round 1 and from the companion real-time Adherence Confidence Text Survey (ACTS).10 Challenges were treated as a binary ‘selected’ or ‘not selected’ variable in analysis.

Income precarity

To assess income precarity, questions were taken from the Wages subscale of the Employment Precariousness Scale.14 Participants were asked to provide their income during their self-isolation period using one of five categories (ranging from ‘Less than £200 a year/ less than £870 a month/ less than £10,400 a year’ to ‘£800 or more a week/ £3,460 or more a month/ £41,500 or more a year’), whether this income enabled them to cover their basic needs, and to what extent it enabled them to cover unforeseen expenses, on a 5-point Likert Scale (from ‘always’ to ‘never’). A ‘do not know’ and ‘prefer not to say’ option was added to all questions for those who did not want to disclose their financial situation. This was then recoded onto a 0–4 scale (where 0 = always, 4 = never). Scores for each item on the scale was divided by 12, summed and multiplied by 4 to give a composite Precarious Income (Wages) score.14 A composite score below 1 indicates low income precarity (i.e. are more financially secure); between 1 and 1.99 is moderate income precarity; and a score of 2 and above is considered high and very high precarious income precarity.14

Sociodemographic characteristics

Sociodemographic characteristics collected included age, gender, ethnicity and living alone. Participant’s WIMD quintile was derived using postcode data held by TTP.

Data analysis

Analysis was conducted in three steps. First, descriptive statistics were calculated for all variables and reported as n (%). Second, chi-squared tests were conducted to assess associations between sociodemographic characteristics and survey round, and between reported challenges to self-isolation and sociodemographic characteristics. Third, binary logistic regression models, adjusted for age, gender, WIMD, living alone, survey round and income precarity were built to assess independent predictors of each challenge reported as adjusted odds ratios (aOR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Weights were applied to all analyses to ensure that the final sample was representative of all eligible participants. A sensitivity analysis was conducted using the data for each survey round separately and showed no difference in results. To increase statistical power, analysis is therefore reported on the full study sample (n = 2027), adjusting for survey round. Due to the number of logistic regression models built, Bonferroni correction was applied to account for multiple testing and significance set at P ≤ 0.002 (i.e. P < 0.05/20 reported challenges). Only those findings that are significant at the corrected level are reported in the results narrative.

Ethical considerations

The Health Research Authority approved the CABINS study (IRAS: 289377).

Results

Sample characteristics

Table 1 displays sample characteristics. There were more female participants (53.6%) than male, over two-fifths lived in the most deprived quintiles (45.1%) and three-fifths (62.9%) had some degree of income precarity (i.e. moderate or high/very high).

Table 1.

Telephone survey samsple characteristics by survey round

| All respondents | Survey round | Sig. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | ||||||

| N = 2027 | N = 1011 | N = 1016 | |||||

| % | N | % | N | % | N | ||

| Gender1 | 0.50 | ||||||

| Male | 45.9 | 931 | 46.9 | 472 | 45.4 | 459 | |

| Female | 53.9 | 1086 | 53.1 | 533 | 54.6 | 553 | |

| Age2 | 0.13 | ||||||

| 18–29 | 29.5 | 598 | 31.8 | 322 | 26.9 | 273 | |

| 30–39 | 18.5 | 374 | 17.7 | 179 | 18.8 | 190 | |

| 40–49 | 17.0 | 344 | 16.1 | 163 | 18.1 | 183 | |

| 50–59 | 20.0 | 405 | 19.5 | 197 | 21.0 | 213 | |

| 60+ | 9.6 | 301 | 8.9 | 150 | 10.4 | 155 | |

| WIMD3 | 0.41 | ||||||

| Most deprived | 21.6 | 437 | 22.1 | 223 | 21.1 | 21 | |

| 2 | 23.5 | 476 | 22.7 | 230 | 24.1 | 245 | |

| 3 | 20.4 | 413 | 19.4 | 196 | 21.7 | 220 | |

| 4 | 17.7 | 359 | 17.5 | 177 | 17.5 | 178 | |

| 5 – Least deprived | 16.9 | 342 | 18.3 | 185 | 15.6 | 159 | |

| Income precarity4 | 0.72 | ||||||

| Low | 22.7 | 460 | 26.3 | 229 | 26.7 | 231 | |

| Moderate | 34.5 | 700 | 39.7 | 344 | 41.1 | 356 | |

| High/very high | 28.4 | 575 | 34.0 | 295 | 32.2 | 279 | |

| Living alone6 | 0.05 | ||||||

| Yes | 18.4 | 372 | 20.1 | 203 | 16.7 | 169 | |

| No | 81.6 | 1655 | 79.9 | 808 | 83.3 | 84.7 | |

Notes: 1 Ten people excluded from analysis who chose ‘In another way’ or ‘Prefer not to say’.

2 Two people excluded from analysis who failed to provide their age.

3 Welsh Index of Multiple Deprivation.

4 Defined as those who self-reported that they were either: (i) a student, (ii) long-term sick or disabled, (ii) retired or (iv) a carer.

5 Two hundred and ninety-three excluded from analysis due to incomplete data.

6 Defined as living with no other adults.

Figures in bold represent statistical significance (to P ≤ 0.05).

Challenges to self-isolation

‘Wanting to see family’ (Round 1 = 66.7%; Round 2 = 61.9% [Table 2]) and ‘wanting to see friends’ (Round 1 = 60.6%; Round 2 = 58.2% [Table 2]) were the main challenges to self-isolation in both survey rounds. Around a third of individuals reported that loneliness was a challenge to self-isolation (Round 1 = 31.2% versus Round 2 = 27.3% [Table 2]) and a quarter of the sample in each survey round said that mental health difficulties were a challenge to self-isolation (Round 1 = 24.6% versus Round 2 = 24.8% [Table 2]).

Table 2.

Challenges faced to self-isolation, split by survey round

| Survey round | Sig. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All respondents | 1 | 2 | |||||

| N = 2,027 | N = 1011 | N = 1016 | |||||

| % | N | % | N | % | N | ||

| You wanted to see family | 64.3 | 1303 | 66.7 | 674 | 61.9 | 629 | 0.03 |

| You wanted to see friends | 59.4 | 1205 | 60.6 | 613 | 58.2 | 592 | 0.28 |

| A lack of exercise/ fresh air | 51.0 | 1033 | 58.6 | 592 | 43.4 | 441 | <0.001 |

| Loneliness | 29.3 | 593 | 31.2 | 315 | 27.3 | 278 | 0.06 |

| Mental health challenges | 24.7 | 501 | 24.6 | 249 | 24.8 | 252 | 0.93 |

| Financial concerns | 18.5 | 376 | 20.4 | 206 | 16.7 | 170 | 0.04 |

| Caring responsibilities for vulnerable adults outside your household | 17.2 | 348 | 17.7 | 173 | 17.3 | 175 | 0.95 |

| Living with people who are not self-isolating | 14.7 | 297 | 17.5 | 177 | 11.8 | 120 | <0.001 |

| No access to food | 9.9 | 201 | 7.7 | 78 | 12.1 | 123 | 0.001 |

| Caring for an individual within your household1 | 10.1 | 204 | – | – | 20.1 | 204 | – |

| Work not supporting you to self-isolate | 7.3 | 148 | 8.8 | 89 | 5.8 | 59 | 0.01 |

| Physical health challenges | 9.8 | 198 | 9.5 | 96 | 10.0 | 102 | 0.68 |

| Caring responsibilities for children outside your household | 8.4 | 171 | 8.5 | 86 | 8.4 | 85 | 0.91 |

| Concerns about the impact of isolation on work or business1 | 7.9 | 160 | – | – | 15.8 | 160 | – |

| Looking after pets or animals1 | 8.8 | 179 | – | – | 17.6 | 179 | – |

| Self-isolating away from vulnerable household members1 | 8.3 | 168 | – | – | 16.5 | 168 | – |

| Lack of support from family and friends | 5.8 | 119 | 64 | 63 | 5.5 | 56 | 0.44 |

| A lack of private outdoors space1 | 5.2 | 105 | – | – | 10.3 | 105 | – |

| No access to medication | 4.8 | 98 | 5.3 | 54 | 4.4 | 44 | 0.29 |

| You did not feel safe to isolate | 1.3 | 26 | 1.6 | 16 | 1.0 | 10 | 0.23 |

| None of the above | 10.2 | 206 | 9.6 | 97 | 10.7 | 109 | 0.40 |

Note: 1 Options only available in Wave 2 Telephone Survey.

Figures in bold represent statistical significance (corrected to P = 0.002).

Differences between survey rounds

Individuals were significantly less likely to say ‘a lack of exercise’ was a challenge in Round 2 than Round 1 (Round 2 = 43.4% versus Round 1 = 58.6, P ≤ 0.001; [Table 2]). A significantly greater number of individuals reported that having ‘no access to food’ was a challenge to self-isolation in Round 2 than Round 1 (Round 2 = 12.1% versus Round 1 = 7.7%; P = 0.001; [Table 2]). Individuals were also significantly more likely to say that ‘living with others who were not self-isolating’ was a challenge in Round 1 than in Round 2 (Round 2 = 11.8% versus Round 1 = 17.5%, P ≤ 0.001; [Table 2]).

Challenges to self-isolation by sociodemographic group

Age

In logistic regression models, adjusted for age, gender, living alone, survey round, and WIMD, younger people (aged 18–29) were three times more likely to report a lack of exercise (aOR = 3.51, [95% CI = 2.50–4.93]), mental health difficulties (aOR = 3.16, [95% CI = 2.05–4.86]) and concerns about the impact of self-isolation on work or business (aOR = 3.46, [95% CI = 1.63–7.35]) than older people [Table 3]. Younger people (aged 18–29) were also two times more likely to report wanting to see friends (aOR = 2.25, [95% CI = 1.62–3.21]) and loneliness (aOR = 1.96, [95% CI = 1.37–2.81]) as challenges to self-isolation, compared to older people. Those under the age of 39 years were three times more likely to report mental health difficulties (18–29: aOR = 3.16, [95% CI = 2.05–4.86]; 30–39: aOR = 2.46, [95% CI = 1.55–3.91]) and those aged between 30 and 49 years were three times more likely to report financial concerns as a challenge to self-isolation (30–39: aOR = 2.90, [95% CI = 1.72–4.89; 40–49: (aOR = 2.78, [95% CI = 1.62–4.76] [Table 3]). Individuals aged 30–39 years were three times more likely to have caring responsibilities for a vulnerable individual in the household (aOR = 3.32, [95% CI = 1.71–6.45]), whereas those aged 50–59 years where two times more likely to say they had caring responsibilities for vulnerable adults outside the household (aOR = 2.36, [95% CI = 1.50–3.74]) [Table 3].

Table 3.

Logistic Regression models

| Rank | Challenge | N | Age | Gender | Living alone | Survey round | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18–29 | 30–39 | 40–49 | 50–59 | 60+ | Male | Female | Yes | No | 1 | 2 | |||

| 1 | Wanting to see family | 1136 | 1.07 [0.76–1.51] | 0.85 [0.59–1.22] | 0.66 [0.46–0.96] | 0.76[0.53–1.09] | Ref. | Ref. | 1.35 [1.10–1.66] | 0.91 [0.70–1.20] | Ref. | Ref. | 0.86 [0.71–1.06] |

| 2 | Wanting to see friends | 995 | 2.25 [1.62–3.12] | 1.20 [0.85–1.69] | 1.07 [0.75–1.51] | 1.01 [0.82–1.23] | Ref. | Ref. | 1.01 [0.82–1.23] | 0.81 [0.62–1.05] | Ref. | Ref. | 0.96 [0.79–1.17] |

| 3 | A lack of exercise | 287 | 3.51 [2.50–4.93] | 3.01 [2.10–4.32] | 2.08 [1.44–2.99] | 1.59 [1.11–2.26] | Ref. | Ref. | 1.02 [0.83–1.25] | 0.81 [0.62–1.09] | Ref. | Ref. | 0.52 [0.42–0.63] |

| 4 | Loneliness | 507 | 1.96 [1.37–2.81] | 1.18 [0.80–1.75] | 0.98 [0.65–1.48] | 0.91 [0.61–1.36] | Ref. | Ref. | 1.31 [1.05–1.64] | 0.41 [0.31–0.53] | Ref. | Ref. | 0.87 [0.70–1.08] |

| 5 | Mental health difficulties | 374 | 3.16 [2.05–4.86] | 2.46 [1.55–3.91] | 1.95 [1.21–3.15] | 1.61 [1.00–2.59] | Ref. | Ref. | 1.51 [1.20–1.92] | 0.71 [0.53–0.96] | Ref. | Ref. | 1.04 [0.82–1.30] |

| 6 | Financial concerns | 327 | 2.10 [1.28–3.45] | 2.90 [1.72–4.89] | 2.78 [1.62–4.76] | 2.08 [1.22–3.55] | Ref. | Ref. | 0.71 [0.54–0.92] | 0.91 [0.65–1.27] | Ref. | Ref. | 0.84 [0.66–1.09] |

| 7 | Caring responsibilities for vulnerable adults outside your household | 304 | 1.05 [0.66–1.67] | 1.21 [0.74–1.98] | 1.87 [1.59–3.00] | 2.36 [1.50–3.74] | Ref. | Ref. | 1.27 [0.98–1.65] | 1.03 [0.80–1.32] | Ref. | Ref. | 1.03 [0.80–1.32] |

| 8 | Living with others who are not self-isolating | 266 | 2.02 [1.19–3.45] | 2.19 [1.25–3.85] | 2.29 [1.30–4.03] | 1.69 [0.96–2.99] | Ref. | Ref. | 1.12 [0.85–1.47] | 2.71 [1.70–4.33] | Ref. | Ref. | 0.62 [0.48–0.82] |

| 9 | No access to food | 181 | 1.51 [0.87–2.63] | 1.39 [0.77–2.52] | 1.38 [0.75–2.53] | 1.00 [0.54–1.86] | Ref. | Ref. | 0.98 [0.71–1.35] | 1.66 [0.96–2.88] | Ref. | Ref. | 1.57 [1.14–2.16] |

| 10 | Caring for a vulnerable individual in the household1 | 170 | 1.21 [0.62–2.39] | 3.32 [1.71–6.45] | 1.95 [0.97–3.92] | 1.45 [0.72–2.91] | Ref. | Ref. | 0.93 [0.65–1.32] | 1.60 [0.95–2.69] | Ref. | Ref. | – |

| 12 | Physical health difficulties | 163 | 0.73 [0.43–1.25] | 0.74 [0.41–1.34] | 1.21 [0.69–2.12] | 1.05 [0.61–1.84] | Ref. | Ref. | 0.74 [0.53–1.04] | 0.70 [0.47–1.05] | Ref. | Ref. | 1.04 [0.75–1.44] |

| 13 | Looking after pets1 | 159 | 3.14 [1.53–6.48] | 1.67 [0.76–3.65] | 2.25 [1.04–4.88] | 2.59 [1.23–5.48] | Ref. | Ref. | 1.36 [0.95–1.96] | 1.66 [0.96–2.88] | Ref. | Ref. | – |

| 14 | Caring responsibilities for children outside your household | 155 | 0.34 [0.19–0.62] | 0.77 [0.44–1.38] | 1.01 [0.57–1.78] | 1.28 [0.76–2.17] | Ref. | Ref. | 0.91 [0.65–1.28] | 1.30 [0.82–2.05] | Ref. | Ref. | 1.57 [1.14–2.16] |

| 15 | Self-isolating away from vulnerable household members | 148 | 1.55 [0.78–3.06] | 1.84 [0.92–3.72] | 1.63 [0.80–3.36] | 1.44 [0.71–2.92] | Ref. | Ref. | 1.10 [0.76–1.59] | 1.80 [1.02–3.19] | Ref. | Ref. | – |

| 16 | Concerned about impact of isolation on work or business1 | 141 | 3.46 [1.63–7.35] | 2.02 [0.90–4.54] | 2.38 [1.06–5.38] | 1.55 [0.68–3.55] | Ref. | Ref. | 0.56 [0.38–0.82] | 0.97 [0.57–1.65] | Ref. | Ref. | – |

| 17 | Work not supporting you to self-isolate | 139 | 1.93 [0.98–3.83] | 1.96 [0.95–4.04] | 1.55 [0.72–3.35] | 1.75 [0.83–3.66] | Ref. | Ref. | 0.60 [0.42–0.87] | 0.72 [0.46–1.12] | Ref. | Ref. | 0.70 [0.49–1.00] |

| 18 | Lack of support from family/ friends | 104 | 1.42 [0.66–3.04] | 2.25 [1.05–4.83] | 1.92 [0.86–4.26] | 1.42 [0.63–3.19] | Ref. | Ref. | 0.64 [0.43–0.98] | 0.38 [0.24–0.59] | Ref. | Ref. | 0.84 [0.56–1.26] |

| 19 | A lack of private outdoors space1 | 91 | 3.09 [1.36–7.02] | 1.20 [0.47–3.04] | 1.40 [0.55–3.54] | 1.40 [0.55–3.54] | Ref. | Ref. | 0.61 [0.39–0.97] | 0.72 [0.39–1.31] | Ref. | Ref. | – |

| 20 | No access to medication | 86 | 1.11 [0.52–2.36] | 1.07 [0.47–2.45] | 1.23 [0.54–2.80] | 1.08 [0.47–2.45] | Ref. | Ref. | 1.14 [0.73–1.79] | 1.31 [0.71–2.44] | Ref. | Ref. | 0.84 [0.54–1.31] |

| 21 | Not feeling safe to self-isolate | 23 | 0.77 [0.20–2.98] | 1.17 [0.28–4.92] | 0.54 [0.09–3.28] | 0.93 [0.21–4.22] | Ref. | Ref. | 0.49 [0.21–1.16] | 1.45 [0.42–5.03] | Ref. | Ref. | 0.55 [0.23–1.31] |

| 11 | None of the above | 164 | 0.36 [0.22–0.59] | 0.38 [0.22–0.66] | 0.60 [0.36–1.00] | 0.45 [0.27–0.75] | Ref. | Ref. | 0.90 [0.65–1.26] | 1.41 [0.89–2.23] | Ref. | Ref. | 1.24 [0.90–1.73] |

| Logistic Regression Table | |||||||||||||

| Challenge | N | WIMD | Income precarity2 | ||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Low | Moderate | High/very high | ||||||

| 1 | Wanting to see family | 1136 | 0.93 [0.67–1.29] | 1.09 [0.79–1.51] | 1.12 [0.81–1.56] | 1.32 [0.93–1.87] | Ref. | Ref. | 1.02 [0.79–1.32] | 1.12 [0.85–1.47] | |||

| 2 | Wanting to see friends | 995 | 1.02 [0.74–1.42] | 1.01 [0.74–1.38] | 0.94 [0.68–1.29] | 1.18 1[0.84–1.65] | Ref. | Ref. | 0.96 [0.74–1.23] | 1.24 [0.95–1.62] | |||

| 3 | A lack of exercise | 287 | 0.69 [0.50–0.97] | 0.60 [0.43–0.83] | 0.70 [0.50–0.97] | 0.59 [0.42–0.82] | Ref. | Ref. | 0.84 [0.65–1.09] | 1.20 [0.92–1.57] | |||

| 4 | Loneliness | 507 | 0.84 [0.59–1.20] | 1.07 [0.76–1.52] | 0.95 [0.66–1.35] | 0.81 [0.56–1.18] | Ref. | Ref. | 1.30 [0.97–1.75] | 2.11 [1.56–2.85] | |||

| 5 | Mental health difficulties | 374 | 1.20 [0.82–1.76] | 1.24 [0.85–1.80] | 1.20 [0.82–1.77] | 0.79 [0.52–1.20] | Ref. | Ref. | 1.40 [1.00–1.95] | 3.08 [2.22–4.28] | |||

| 6 | Financial concerns | 327 | 1.79 [1.15–2.78] | 1.62 [1.04–2.51] | 1.43 [0.91–2.26] | 1.18 [0.73–1.90] | Ref. | Ref. | 2.56 [1.67–3.92] | 7.73 [5.10–11.74] | |||

| 7 | Caring responsibilities for vulnerable adults outside your household | 304 | 1.19 [0.78–1.82] | 1.27 [0.85–1.91] | 1.19 [0.79–1.81] | 0.97 [0.62–1.52] | Ref. | Ref. | 0.82 [0.60–1.14] | 1.07 [0.77–1.50] | |||

| 8 | Living with others who are not self-isolating | 266 | 1.05 [0.67–1.63] | 1.19 [0.77–1.82] | 0.96 [0.61–1.50] | 1.08 [0.69–1.69] | Ref. | Ref. | 0.90 [0.64–1.28] | 1.04 [0.73–1.49] | |||

| 9 | No access to food | 181 | 0.98 [0.59–1.62] | 0.77 [0.46–1.30] | 1.09 [0.66–1.80] | 0.78 [0.45–1.35] | Ref. | Ref. | 0.89 [0.57–1.38] | 1.90 [1.25–2.89] | |||

| 10 | Caring for a vulnerable individual in the household1 | 170 | 1.18 [0.67–2.10] | 1.09 [0.62–1.93] | 0.99 [0.56–1.77] | 0.74 [0.39–1.41] | Ref. | Ref. | 1.16 [0.72–1.86] | 2.51 [1.57–4.03] | |||

| 11 | Physical health difficulties | 163 | 1.18 [0.70–1.98] | 0.84 [0.49–1.44] | 0.93 [0.55–1.60] | 0.67 [0.37–1.23] | Ref. | Ref. | 1.94 [1.19–3.14] | 2.57 [1.57–4.21] | |||

| 12 | Looking after pets1 | 159 | 1.30 [0.74–2.31] | 0.77 [0.43–1.40] | 1.06 [0.60–1.89] | 0.86 [0.46–1.59] | Ref. | Ref. | 1.14 [0.72–1.82] | 1.30 [0.80–2.11] | |||

| 13 | Caring responsibilities for children outside your household | 155 | 1.18 [0.68–2.04] | 1.17 [0.69–1.99] | 0.77 [0.43–1.38] | 0.96 [0.53–1.72] | Ref. | Ref. | 1.52 [0.94–2.43] | 2.39 [1.48–3.84] | |||

| 14 | Self-isolating away from vulnerable household members | 148 | 0.83 [0.46–1.49] | 0.69 [0.38–1.23] | 1.00 [0.57–1.76] | 0.64 [0.34–1.20] | Ref. | Ref. | 0.94 [0.59–1.50] | 1.47 [0.91–2.36] | |||

| 15 | Concerned about impact of isolation on work or business1 | 141 | 0.98 [0.51–1.86] | 1.30 [0.70–2.41] | 0.89 [0.46–1.70] | 1.29 [0.67–2.49] | Ref. | Ref. | 1.25 [0.75–2.10] | 2.26 [1.35–3.78] | |||

| 16 | Work not supporting you to self-isolate | 139 | 2.10 [1.13–3.89] | 1.51 [0.80–2.85] | 1.35 [0.70–2.61] | 1.09 [0.54–2.21] | Ref. | Ref. | 1.31 [0.76–2.26] | 2.99 [1.77–5.02] | |||

| 17 | Lack of support from family/friends | 104 | 0.82 [0.44–1.55] | 0.85 [0.46–1.58] | 0.82 [0.43–1.57] | 0.38 [0.16–0.87] | Ref. | Ref. | 0.98 [0.54–1.77] | 2.45 [1.41–4.25] | |||

| 18 | A lack of private outdoors space1 | 91 | 1.84 [0.83–4.10] | 1.62 [0.72–3.61] | 1.16 [0.50–2.69] | 1.44 [0.61–3.40] | Ref. | Ref. | 1.17 [0.62–2.23] | 1.95 [1.04–3.66] | |||

| 19 | No access to medication | 86 | 1.29 [0.66–2.52] | 0.79 [0.39–1.63] | 1.10 [0.55–2.20] | 0.39 [0.16–0.99] | Ref. | Ref. | 0.92 [0.49–1.74] | 1.88 [1.03–3.43] | |||

| 20 | Not feeling safe to self-isolate | 23 | 2.17 [0.45–10.50] | 1.19 [0.21–6.58] | 2.27 [0.46–11.33] | 1.13 [0.19–6.86] | Ref. | Ref. | 4.86 [0.60–39.44] | 12.68 [1.66–97.00] | |||

| 21 | None of the above | 164 | 1.07 [0.61–1.87] | 1.44 [0.85–2.43] | 1.35 [0.80–2.29] | 0.86 [0.47–1.57] | Ref. | Ref. | 0.74 [0.50–1.09] | 0.55 [0.35–0.87] | |||

Notes: 1 Options only available in Wave 2 Telephone Survey.

2 Not all respondents answered the three questions associated with the income precarity measure (N = 292), leaving a sample of 1735.

Figures in bold represent statistical significance (corrected to P = 0.002).

Gender

Women were 1.5 times more likely than men to say they experienced mental health difficulties as a challenge to self-isolation (aOR = 1.51, [95% CI = 1.20–1.92]) [Table 3].

Income precarity

Individuals with moderate income precarity were two times more likely to report financial concerns as a challenge to self-isolation (aOR = 2.56 [95% CI = 1.67–3.92]) than their more financially secure counterparts [Table 3]. Those in the highest income precarity group were eight times more likely to report financial concerns (aOR = 7.73 [95% CI = 5.10–11.74]) and were three times more likely to report mental health difficulties (aOR = 3.08 [95% CI = 2.22–4.28]), caring for a vulnerable individual in the household (aOR = 2.51, [95% CI = 1.57–4.03]), physical health difficulties (aOR = 2.57, [95% CI = 1.57–4.21]) and work not supporting them to self-isolate (aOR = 2.99, [95% CI = 1.77–5.02]) as a challenge to self-isolation [Table 3]. They were also two times more likely to report a lack of support from family or friends (aOR = 2.45, [95% CI = 1.41–4.25]), caring responsibilities for children outside the household (aOR = 2.39, [95% CI = 1.48–3.84]) and loneliness (aOR = 2.11, [95% CI = 1.56–2.85]) [Table 3]. No significant differences were found when looking at the differences in the challenges reported by deprivation quintile [Table 3].

Discussion

Our study identified that self-isolation is particularly challenging for younger people aged under 30, women, and those with precarious incomes. These population sub-groups were more likely to report mental health difficulties, loneliness and concerns about the impact of self-isolation on their work or business, wanting to see friends and a lack of exercise as challenges to self-isolation.

What is already known on this topic?

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted and exacerbated existing health inequalities, disproportionately impacting women, those who are in low-skilled employment, of younger age or those with underlying health conditions.15 Specifically, younger people are more likely to be affected by disruption in their education at a critical time and in the long-term most are at risk of poor employment and the associated health outcomes in economic downturn.16 Also, individuals who already struggled to cover their basic financial needs, were significantly more likely to be placed on ‘Furlough’ during the pandemic,17 further increasing their financial concerns and risk for non-compliance to COVID-19 restrictions. Due to these concerns, these low-income groups (those who earn <£20 000 a year or had <£100 saved), report three times lower ability to self-isolate than their more wealthy counterparts.15 Lastly, women continue to do the majority of unpaid care within households18 and face high risks of economic insecurity19 and are over-represented in caring professions, especially nursing and are working at the front-line of the response to COVID-19.18 Self-isolation and lockdown restrictions will also increase the demand for unpaid work at home, much of which traditionally falls onto women.19

Governments moving quickly to introduce schemes to compensate for financial loss during self-isolation to encourage adherence.20 In Wales, the self-isolation support scheme was introduced on 23 October 202021 and provided people who met eligibility criteria with £500 for each period of self-isolation up to a maximum of three times after they (or from 7 December 2020 their child) had been advised to self-isolate.22 This payment was subsequently increased to £750 on 7 August 2021.21 Moreover, to support younger people and to mitigate against the decline in their mental health, charities and support groups have developed online blogs, videos and support groups.22 However, currently very little support exists that is targeted specifically at women during their self-isolation.18

What does our study add?

Our findings highlight the importance of directing support to younger people (aged under 30), those with precarious incomes and women during initial conversations with contact tracers. For example, as younger people are more likely to be employed through the expanding ‘gig economy’, and consequently may have no access to sick pay, stable work contracts or the ‘furlough’ scheme,17 it is important to consider support mechanisms so that these individuals do not fall through cracks in social or financial support systems. Also, given that women are significantly more likely to face economic insecurity, be unpaid carers, and live in vulnerable or harmful situations support needs to be targeted specifically to this group. Specific support for those living in challenging social circumstances could be enabled by expanding community partnerships, training contact tracers to recognize emerging mental health issues, those women who may be struggling with their social circumstances, signs of abuse and violence, and spreading awareness about the importance of reporting incidents.23 Internationally, to support these groups, countries have implemented warning systems to enable victims of gender and family violence to alert the authorities.24

Our study found that people with precarious incomes not only experienced financial challenges of self-isolation, but also challenges with employers and mental health concerns. This means that identification of people with precarious incomes is important to enable access to both financial and mental health support to individuals, as well as to employers to enable employees to self-isolate. However, there are challenges associated with identifying groups with precarious incomes. Asking about income at the point of contact tracing could be viewed as sensitive, especially when efforts have been made to encourage engagement with the contact tracing systems by reassuring citizens that financial information, such as bank details, would not be requested. To protect against these harms in future infectious disease outbreaks, an income precarity measure such as that used in our study could be used during initial conversations with contact tracers to identify financial needs and direct financial support. Our study suggests that this would be a justified approach when set against the health and economic harms of self-isolation this group reported.

Strengths and limitations

Our study is the first in Wales to examine the challenges faced by people asked to self-isolate. It included responses from a representative sample of contacts of COVID-19 identified through the national TTP database, ensuring that all those in the study had been confirmed and informed to self-isolate. This enabled sampling to ensure that contacts in our study were representative of all contacts successfully reached by TTP in each of the periods of interest for the two survey rounds. However, this also presents the key limitation of the study, as it includes only those who have been successfully reached by a contact tracer and informed to self-isolate. It is likely that those who are not successfully reached may perceive additional challenges to self-isolation that are not captured in our findings.

Conclusion

Our study found that young adults, females and those with precarious incomes are more likely to report facing challenges during periods of self-isolation to control the spread of COVID-19. Identifying those with precarious incomes and at greatest risk of experiencing mental health harms of self-isolation during initial conversations with contact tracers is a key priority to ensure comprehensive assessment of needs and access to targeted support to help maximize potential adherence to self-isolation during this and future pandemics.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the Public Health Wales Research and Development office on PHW.research@wales.nhs.uk. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Authors’ contribution

KI, RK and AD conceputaltised the study. KI, RK and AD performed methodology of the study. KI and RK the project management. KI wrote the original draft of the manuscript. KI, RK and BG did the data analysis. KI, RK, BG and AD edited the final draft. RK and AD acquired the funding RK and AD had project oversight.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank colleagues in the Research and Evaluation Division, Public Health Wales, for their support in completing this work, particularly James Bailey and Poppy Escritt. The authors would also like to thank Beaufort Research Limited, who conducted data collection. CABINS was funded by Public Health Wales.

Kate Isherwood, Senior Public Health Researcher.

Richard Kyle, Deputy Head of Research and Evaluation.

Benjamin Gray, Senior Public Health Researcher.

Alisha Davies, Head of Research and Evaluation.

Contributor Information

Richard G Kyle, Research and Evaluation Division, Public Health Wales, Cardiff, Wales CF10 4BZ, UK.

Benjamin J Gray, Research and Evaluation Division, Public Health Wales, Cardiff, Wales CF10 4BZ, UK.

Alisha R Davies, Research and Evaluation Division, Public Health Wales, Cardiff, Wales CF10 4BZ, UK.

References

- 1. World Health Organisation . 2020. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Advice for the Public. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public (6 September 2021, date last accessed).

- 2. UK Government . 2020. New Legal Duty to Self-Isolate Comes into Force Today. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/new-legal-duty-to-self-isolate-comes-intoforce-today. (6 September 2021, date last accessed).

- 3. UK Government . 2021. Self-Isolation Removed for Double-Jabbed Close Contacts from 16th August. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/self-isolation-removed-for-double-jabbed-close-contacts-from-16-august. (22 October 2021, date last accessed).

- 4. Welsh Government . 2021. Self-Isolation. Available from: https://gov.wales/self-isolation. (20 October 2021, date last accessed).

- 5. NHS . 2021. Help the NHS Alert Your Close Contacts If You Test Positive for Coronavirus (COVID-19). Available from: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/coronavirus-covid19/testing/test-results/help-the-nhs-alert-your-close-contacts-if-you-test-positive/. (16 April 2021, date last accessed).

- 6. Welsh Government . 2020. Test Trace Protect: Our Strategy for Testing the General Public and Tracing the Spread of Coronavirus in Wales. Available from: https://gov.wales/testtrace-protect-html. (16 April 2021, date last accessed).

- 7. NHS Scotland . 2020. Coronavirus (COVID-19): Contact Tracing. Available from: https://www.nhsinform.scot/illnesses-and-conditions/infections-andpoisoning/coronavirus-covid-19/test-and-protect/coronavirus-covid-19-contact-tracing. (16 April 2021, date last accessed).

- 8. Public Health Agency . 2020. Testing and Tracing for COVID-19. Available from: https://www.publichealth.hscni.net/covid-19-coronavirus/testing-and-tracing-covid-19. (16 April 2021, date last accessed).

- 9. Smith LE, Potts HWW, Amlot R et al. Adherence to the test, trace and isolate system: results from a time series of 21 nationally representative surveys in the UK the COVID-19 rapid survey of adherence to interventions and responses [CORSAIR]. BMJ 2020. 10.1101/2020.09.15.20191957. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kyle, R.G., Isherwood, K.R., Bailey, J.W., Davies, A.R. (2021). Self-Isolation Confidence, Adherence and Challenges: Behavioural Insights from Contacts of Cases of COVID-19 Starting and Completing Self-Isolation in Wales. Cardiff: Public Health Wales. Available from: https://phw.nhs.wales/publications/publications1/self-isolation-confidenceadherence-and-challenges-behavioural-insights-from-contacts-of-cases-of-covid-19starting-and-completing-self-isolation-in-wales/ [Google Scholar]

- 11. Office of National Statistics . 2021. Coronavirus and Self-isolation after Testing Positive in England: 10th May to 15th May 2021. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/healthandwellbeing/bulletins/coronavirusandselfisolationaftertestingpositiveinengland/10mayto15may2021. (09 June 2021, date last accessed).

- 12. Keyworth C, Epton T, Byrne-Davies L et al. What challenges do UK adults face when adhering to COVID-19 related instructions? Cross-sectional survey in a representative sample. Prev Med 2021;147:106458. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Welsh Government . 2020. National Coronavirus Firebreak to be Introduced in Wales on Friday. Retrieved from: https://gov.wales/national-coronavirus-fire-break-to-beintroduced-in-wales-on-friday. (09 June 2021, date last accessed).

- 14. Vives A, Amable M, Ferrer M et al. The employment precariousness scale (EPRES): psychometric properties of a new tool for epidemiological studies among waged and salaried workers. Occup Environ Med 2010;67(8):548–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bambra C, Riordan R, Ford J, Matthews F. The COVID-19 -pandemic and health inequalities. J Epidemiol Community Health 2020;74(11):964–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Douglas M, Katikireddi S, Taulbut M et al. Mitigating the wider health effects of COVID-19 pandemic response. BMJ 2020;369. 10.1136/bmj.m.1557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gray BJ, Kyle RG, Song J, Davies AR. Characteristics of those most vulnerable to employment changes during the COVD-19 pandemic: a nationally representative cross-sectional study in Wales. J Epidemiol Community Health 2021. 10.1136/jech-2020-216030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. OECD . 2020. Women at the Core of the Fight against COVID-19 Crisis. Available from: https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/women-at-the-core-of-the-fightagainst-covid-19-crisis-553a8269/. (28 June 2021, date last accessed).

- 19. OECD . 2019. Health at a Glance 2019. Available from: https://www.oecdilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/health-at-a-glance-2019_4dd50c09-en. (29 June 2021, date last accessed).

- 20. UK Government . 2020. Claiming Financial Support under the Test and Trace Support Payment Scheme. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/test-andtrace-support-payment-scheme-claiming-financial-support/claiming-financial-supportunder-the-test-and-trace-support-payment-scheme. (28 June 2021, date last accessed).

- 21. Welsh Government . 2020. Self-Isolation Support Scheme. Available from: https://gov.wales/self-isolation-support-scheme. (28 June 2021, date last accessed).

- 22. Young Minds . 2020. Coronavirus and Mental Health. Available from: https://youngminds.org.uk/find-help/looking-after-yourself/coronavirus-and-mentalhealth/#i-am-struggling-with-self-isolation-and-social-distancing-. (29 June 2021, date last accessed).

- 23. Campbell AM. An increasing risk of family violence during COVID-19 pandemic: strengthening community collaborations to save lives. Forensic Science International Reports 2020;2:1–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Guenfound, I 2020. French Women Use Code Words at Pharmacies to Escape Domestic Violence During Coronavirus Lockdown. ABC News. Available from: https://abcnews.go.com/International/frenchwomen-code-words-pharmacies-escapedomestic-violence/story?id=69954238. (06 July 2021, date last accessed).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the Public Health Wales Research and Development office on PHW.research@wales.nhs.uk. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.