Abstract

Background

The goal of this study was to investigate the effects of treatment with Saccharomyces boulardii and Lactobacillus reuteri on the eradication of Helicobacter pylori and Adverse effects (AEs) of the treatment.

Results

This study was a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. And, eradication of H. pylori was reported comparing quadruple therapy include of PPI (proton pomp inhibitor), bismuth subcitrate, clarithromycin, and amoxicillin versus quadruple therapy supplemented with S. boulardii and L. reuteri DSMZ 17648. For this aim, a total of 156 patients were included in the current study; and patients positive for H. pylori infection (n = 156) were randomly assigned to 3 groups: 52 patients (Group P) received conventional quadruple therapy plus L. reuteri, 52 patients (Group S) received conventional quadruple therapy plus S. boulardii daily, for 2 weeks, and 52 patients were in the control group (Group C). At the end of the treatment period, all the subjects continued to take proton pump inhibitor (PPI) alone for 14 days, and then, no medication was given for 2 weeks again. During follow-up, gastrointestinal symptoms were assessed using an evaluation scale (Glasgow dyspepsia questionnaire [GDQ]), and AEs were assessed at 7, 14, 21, and 28 days. As a result, all patients completed the treatment protocol in all groups by the end of the study. Additionally, eradication therapy was effective for 94.2% of subjects in Group S, 92.3% of subjects in Group P, and 86.5% of subjects in the control group, with no differences between treatment arms. In Group S, the chance of developing symptoms of nausea (OR = 2.74), diarrhea (OR = 3.01), headache (OR = 10.51), abdominal pain (OR = 3.21), and anxiety (OR = 3.58) was significantly lower than in the control group (p < 0.05).

Conclusion

S. boulardii could significantly reduce some AEs of H. pylori eradication therapy, but effectiveness of Lactobacillus reuteri on these cases was not significant. It is recommended to conduct the future research with larger sample size in order to investigate the effect.

Trial registration: IRCT20200106046021N1, this trial was registered on Jan 14, 2020.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12876-022-02187-z.

Keywords: Adverse effects, Eradication rate, Helicobacter pylori, Lactobacillus reuteri, Saccharomyces boulardii, Sequential treatment

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori is a gram-negative infective bacterium affecting more than half of the world's population [1]. H. pylori infection contributes to etiology of a variety of diseases, such as gastric ulcer disease, dyspepsia, lymphoma, and gastric cancer [2–4]. Treatment of H. pylori infection is still being debated around the world, owing to emergence of multidrug-resistant strains of H. pylori. At the present, the most effective treatment options for H. pylori infection are complete pathogen eradication using multiple combinations of proton pump inhibitors (PPI) and two or three antibiotics [5–7]. This complicated approach carries a high risk of adverse effects (AEs), antibiotic resistance, and incompatibility [8, 9]. Reduced H. pylori load in the stomach by selective bacterial-bacterial surface interaction indicates a novel treatment approach to mitigating the danger posed by this human infection. Bacterial accumulation has previously been discussed in terms of infection elimination via specific binding to pathogens and formation of co-aggregates [10–12]. Many observations support the use of probiotics with bioactive components in people infected with H. pylori, recommending the use of multiplex probiotic microorganisms in control and treatment of infections caused by H. pylori [13, 14]. It has been proposed that Lactobacillus supplementation may be effective in accelerating removal of H. pylori in first-time patients, as well as having a positive effect on some AEs associated with H. pylori treatment [15]. To date, saccharomyces boulardii and several Lactobacillus reuteri strains have been used alone or in combination with various H. pylori treatment regimens in clinical studies [16–29]. Previous studies have explored the effects of Saccharomyces boulardii and Lactobacillus Reuteri on the eradication of H. pylori and the elimination of AEs associated with the four-drug treatment separately or in comparison. However, very few studies have been done to compare the effects of Lactobacillus reuteri (DSMZ 17648) and Saccharomyces boulardii on this topic.

Therefore, purpose of this study was investigating whether adding saccharomyces boulardii (DAILY EAST®) probiotic or a supplement of DSMZ 17648 Lactobacillus reuteri (PYLOSHOT®) to the standard quadruple treatment for H. pylori infection after 14 days increases eradication rate and reduces the AEs. Due to lack of sufficient studies in this field, there is a need for a clinical trial and it is hoped that the results of this study will be useful in improving treatment of H. pylori.

Method and materials

A total of 156 patients were included in the current study. A total of 156 patients were included in the current study. The sample size was calculated based on Zojaji et al. [27] by using a sample size formula for comparison proportion. In this study, the percentage of improvement in group A (amoxicillin 1 g twice daily, clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily, omeprazole 20 mg twice daily, and probiotic Saccharomyces bulardi 250 mg twice daily) was 0.875, and in group B (amoxicillin 1 g twice daily, clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily, omeprazole 20 mg twice daily) was 0.812.

At the end of the treatment period, all the subjects continued to take proton pump inhibitor (PPI) alone for 14 days, and then no medication was given for 2 weeks again. During follow-up, gastrointestinal symptoms were assessed using an evaluation scale (Glasgow dyspepsia questionnaire (GDQ)), and Adverse effects were assessed at 7, 14, 21, and 28 days.

Study design

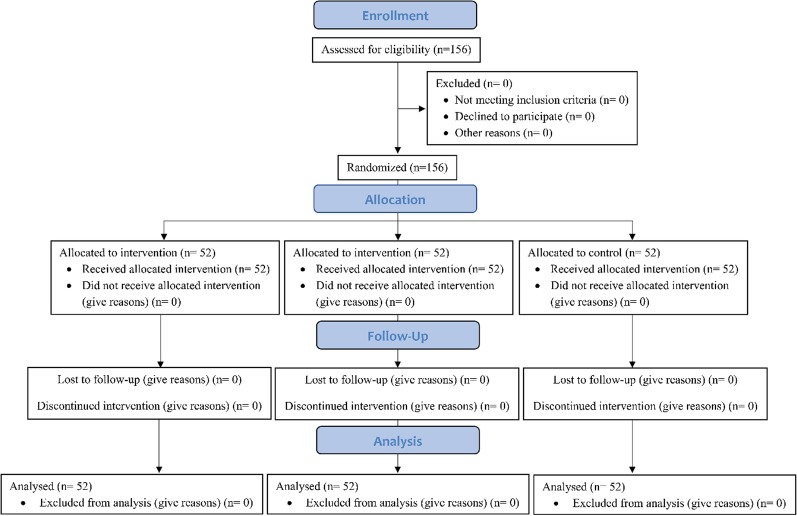

This study was designed according to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guideline [30]. The work flow for the overall procedure is shown in Fig. 1. Patients who were referred to the Gastroenterology Clinic of the Valiasr Hospital and met all the inclusion criteria were included in the study. Then, patients were randomly assigned to treatment groups by tossing a coin.

Fig. 1.

CONSORT diagram of the study

Inclusion criteria

Symptomatic H. pylori-positive patients of both sexes aged between 16 and 74 years old whose infection was confirmed by endoscopy and pathology were included in the study. Endoscopy and histopathological analysis on Antrum and body were performed by a pathologist blinded to the treatment arm and the time points of tissue sampling to determine the presence of H. pylori. Giemsa stain was used to stain all biopsies.

Exclusion criteria

Patients with less than 15 years of age, pregnant or lactating women, patients with hepatic, cardio-respiratory, renal, and neoplastic diseases, those receiving antibiotics, PPIs, bismuth salts, or probiotics within the previous 4 weeks, patients with a history of gastric surgery and sensitivity to any of the drugs used in this study, those receiving any medication interfering with the action of the lactobacilli, gastrectomy or gastric bypass, patients with autoimmune disease, organ transplantation, weight changes > 3 kg over the last 3 months, those with the history of eradication of H. pylori infection, lactose intolerance, and those participating in other clinical trials at the same time were excluded from the study.

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Research Council and Ethics Committee of the Birjand University of Medical Sciences with the ethics code of IR.BUMS.REC.1398.305. It was also registered on the website of the Iranian registry of clinical trials (IRCT) with the following Number: IRCT20200106046021N1 on 14/01/2020. An informed written consent was obtained from all the patients. No costs were imposed on patients. The drugs used in the study, as well as the dose administered to patients, had no AEs or toxicity. The final report and analysis were performed without names of the participants in the study. The modified Glasgow dyspepsia questionnaire (GDQ) was used to record dyspeptic symptoms before starting therapy and at the end of the follow-up period.

Treatment protocol

The interventions were based on the regimen containing bismuth and clarithromycin, and amoxicillin for H. pylori, which included 1 g of Amoxicillin twice daily, 500 mg of Clarithromycin twice daily, 40 mg of PPI (esomeprazole (Nexium®), lansoprazole (Takepron®. OD), pantoprazole (Pantoloc®), and rabeprazole(pariet)) twice daily, and 120 mg of bismuth subcitrate (two tablets, twice daily). Patients in Group S were given 1 capsule of DAILYEAST® (saccharomyces boulardii supplement 250 mg, ZistTakhmir, Tehran, Iran) b.i.d in combination with anti H. pylori quadruple therapy. Patients in Group P were given 2 capsules of PHYLOSHOT® (100 mg of non-viable Lactobacillus reuteri DSMZ 17648, Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus casei, and Bifidobacterium lactis > 109 CFU, ZistTakhmir, Tehran, Iran) b.i.d in combination with anti H. pylori quadruple therapy. Patients in the control group were also given a placebo capsule b.i.d along with anti H. pylori quadruple therapy. Duration of treatment was equal to 14 days.

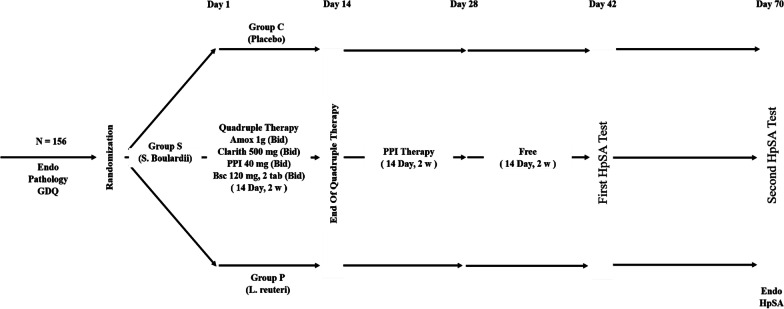

At the end of the treatment period, all the subjects continued to take PPI alone for 14 days. Then, the patients were given no medication for 2 weeks before having their first fecal antigen test (Novin Research®), at the end of the second week. Then, after another 4 weeks, they had a second stool antigen test (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Flow chart of the study. A total of 156 patients met the inclusion criteria. HpSA: H. pylori stool antigen, Endo: endoscopic, GDQ: Glasgow dyspepsia questionnaire, PPI: proton pomp inhibitor, Amox: amoxicillin, Clarith: clarithromycin, b.i.d: twice daily, BSC: bismuth subcitrate

Evaluation of treatments adverse effects and tolerability

Using a previously reported questionnaire, the Adverse effects (AEs) profile and tolerability were assessed during the follow-up period. The term "Adverse effects" in this study refers to the symptoms and complaints of patients caused by the use of antibiotic medicines during treatment and their persistence until two weeks after stopping antibiotics. Subjects were carefully instructed and trained on filling out questionnaires in order to achieve the highest level of compliance in registering any potential treatment-related AEs. Subjects were asked to report any side effects during and after therapy, such as bitter taste, nausea, vomiting, epigastric discomfort, abdominal pain, and diarrhea.

Statistical analysis

After entering the SPSS 24 software, the data were described using central and dispersion indices for quantitative variables and frequency and agreement tables for qualitative variables. Homogeneity of groups was assessed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Chi-Square tests. Marginal logistic model with generalized estimating equation (GEE) approach was used for modeling the changes in complications during the study. In the tests, significance level was set at 0.05.

Results

Patients

A total of 156 subjects with confirmed H. pylori infection completed the treatment protocol in all groups by the end of the study. The study included 60.9 percent female participants and 39.1% male participants, with a mean age of 47.76 ± 13.92 years old (age range of 16–74 years old). They were randomly assigned into three study arms: 52 patients were assigned into the L. Reuteri group (Group P), 52 patients were assigned into the S. boulardii group (Group S), and 52 patients were assigned into the placebo group (Group C). The majority of our patients (93.6%) were from rural areas, housewife (46.8%), and non-smokers (76.9%). Dyspepsia was the most common reason for undergoing an endoscopy procedure (64.7%). At the time of the first endoscopy, the majority of patients had antral gastritis. Antral and corpus predominant gastritis were found in 88.5and 27.6% of patients, respectively. The three treatment groups were similar in terms of their demographic, clinical, and endoscopic characteristics at baseline (Table 1) (p > 0.05).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the all groups

| Group C | Group S | Group P | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 46.57 ± 14.20 | 49.32 ± 13.42 | 47.38 ± 14.25 | 0.58 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 34.6% (18) | 48.1% (25) | 34.6% (18) | 0.26 |

| Female | 65.4% (34) | 51.9% (27) | 65.4% (34) | |

| Smoking | ||||

| Yes | 17.3% (9) | 32.7% (17) | 19.2% (10) | 0.12 |

| No | 82.7% (43) | 67.3% (35) | 80.8% (42) | |

| Endoscopic reasons | ||||

| Dyspepsia | 59.6% (31) | 67.3% (35) | 67.3% (35) | 0.63 |

| Heart Burn | 25% (13) | 25% (13) | 21.2% (11) | 0.86 |

| Endoscopic pattern of gastritis | ||||

| Antral gastritis | 92.3% (48) | 82.7% (43) | 90.4% (47) | 0.26 |

| Corpus gastritis | 23.1% (12) | 21.2% (11) | 38.5% (20) | 0.09 |

| Pan-gastritis | 3.8% (2) | 11.5% (6) | 3.8% (2) | 0.22 |

| Duodenal ulcer | 3.8% (2) | 0.0% (0) | 1.9% (1) | 0.77 |

| Gastric ulcer | 0.0% (0) | 1.9% (1) | 5.8% (3) | 0.32 |

| Esophagitis | 0.0% (0) | 0.0% (0) | 0.0% (0) | – |

| Normal | 1.9% (1) | 1.9% (1) | 0.0% (0) | 1.00 |

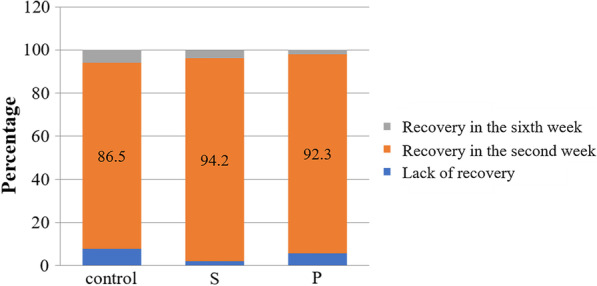

Eradication rate

The highest rate of H. pylori eradication occurred in all groups in the second week after treatment. Totally, 86.5, 94.2, and 92.3% of eradication was observed in the control, S, and P groups, respectively. In general, eradication rate in the studied groups was not statistically significant in the second and sixth weeks, (with P = 0.46 in the second week and P = 0.53 in the sixth week, respectively) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Rate of eradication of H. pylori infection in the studied groups

Patients compliance and adverse effects

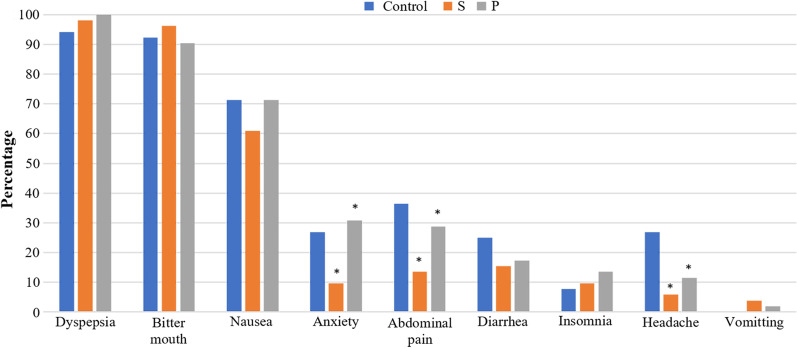

Headache, abdominal pain, and anxiety were significantly reduced in the Group S (who received saccharomyces boulardii probiotic-DAILYEAST®). But in Group P, headache and abdominal pain were significantly reduced and anxiety was significantly increased (p < 0.05). However, none of the study groups experienced significant changes in vomiting, insomnia, bitter taste in the mouth, or epigastric discomfort (p > 0.05) (Table 2). According to Table 2, after adjusting the effect of time, in the Group S, chance of developing symptoms of headache (OR = 10.51), abdominal pain (OR = 3.21), and anxiety (OR = 3.58) was significantly lower than control group (p < 0.05). Also, except for headache (OR = 3.75), the Group P did not differ significantly from the control group in incidence of complications (p > 0.05) (Fig. 4). For more details, see Additional file 1.

Table 2.

Generalized estimating equations (GEE) logistic model of the association between the treatment group and complications

| Outcome | Variables | Coefficient | SE | P value | OR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nausea | Treatment group | S | 0.90 | 0.36 | 0.01 | 2.47 |

| Base line: control group | P | 0.41 | 0.36 | 0.26 | 1.52 | |

| Time | 1.51 | 0.14 | < 0.001 | 4.55 | ||

| Diarrhea | Treatment group | S | 1.10 | 0.49 | 0.02 | 3.01 |

| Base line: control group | P | 0.63 | 0.51 | 0.21 | 1.89 | |

| Time | 1.74 | 0.16 | < 0.001 | 5.74 | ||

| Headache | Treatment group | S | 2.35 | 0.65 | < 0.001 | 10.51 |

| Base line: control group | P | 1.32 | 0.55 | 0.01 | 3.75 | |

| Time | 1.08 | 0.26 | < 0.001 | 2.95 | ||

| Abdominal pain | Treatment group | S | 1.16 | 0.54 | 0.03 | 3.21 |

| Base line: control group | P | 0.39 | 0.43 | 0.36 | 1.48 | |

| Time | 1.14 | 0.17 | < 0.001 | 3.14 | ||

| Anxiety | Treatment group | S | 1.27 | 0.56 | 0.02 | 3.58 |

| Base line: control group | P | − 0.38 | 0.46 | 0.40 | 0.68 | |

| Time | 0.61 | 0.12 | < 0.001 | 1.86 | ||

Fig. 4.

Distribution frequency of AEs observed in the study groups

Discussion

Treatment of H. pylori infection is becoming increasingly important, particularly in developing countries. Despite availability of various therapeutic regimens, treatment failure has remained a growing problem in daily clinical practices. Several factors could contribute to failure of eradication, but the most important factors are antibiotic resistance and clinical efficacy [31]. According to findings of the current study, there was no statistically significant difference between the study results at the second and sixth weeks after treatment. These findings were in agreement with the Zojaji et al. study that evaluated the efficacy and safety of adding S. boulardii to standard triple therapy in 160 adult patients with biopsy confirmed H. pylori infection. They randomized patients into two treatment regimens: patients in group A (n = 80) were given amoxicillin, clarithromycin, omeprazole, and a probiotic of Saccharomyces boulardii for 14 days. Moreover, patients in group B (n = 80) were given amoxicillin, clarithromycin, and omeprazole for 14 days. After the second week, the success rate for H. pylori eradication in group A was higher at 75 (87.5%) than in group B at 65 (81.2%), but the difference between the two groups was not significant [27]. Furthermore, Cindoruk et al., in a study on assessing the effect of S. boulardii on eradication of H. pylori infection and reduction of AEs reported no significant difference in H. pylori eradication between the study groups (71% in the S. boulardii-treated group and 60% in the placebo group), which was consistent with our findings [32]. Also, Shavakhi et al., found that using a combination of probiotics containing Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, and Streptococcus thermophilus species along with a standard quadruple therapy had no beneficial effect in treating H. pylori infection. This could be due to the probiotic diet's low dose or high frequency of upper gastrointestinal AEs, which can reduce H. pylori eradication [33]. On the other hand, Poonyam et al., indicated that eradication of H. pylori was significantly increased compared to the control group when Lactobacillus reuteri was used in combination with a standard quadruple therapy [34]. Moreover, Yu et al. demonstrated that Lactobacillus can significantly eradicate H. pylori in a meta-analysis with a sample size of 724 patients to investigate the probiotic effect of Lactobacillus in combination with a triple eradication regimen [35]. In addition, Zhou et al., in a meta-analysis showed that S. boulardii can significantly increase eradication of H. pylori [36], all these studies were not in agreement with our findings. Among the reasons for this mismatch, one can mention a difference in the type of probiotic used in the studies in terms of the strains used or the large sample size and multi-center nature of these studies are reasons for the inconsistency between the findings.

With the widespread use of probiotics in clinical practice in recent years, the concept of "treating bacteria with probiotics" has been proposed as a new strategy to eradicate H. pylori. However, the mechanism underlying L. reuteri and S. Bouvardia’s eradication of H. pylori has not been fully elucidated. Several potential mechanisms have been proposed, including the following:

The volume of S. boulardii is 10 times larger than that of common bacterial strains of probiotics, which increases the surface area and can better adhere to pathogenic bacteria, affecting the colonization of H. pylori in the gastric mucosa [37]. S. boulardii comprises neuraminidase activity selective for alpha (2–3)‐linked sialic acid, and acts as a ligand binding to H. pylori adhesin, which in turn inhibits the adhesion of H. Pylori in the duodenum [38].

Increasing antimicrobial substances, such as short‐chain fatty acids, inhibiting the growth and proliferation of H. pylori [39].

S. boulardii may stimulate an increase in secretory IgA and immunoglobulin levels [40], strengthening the mucosal immune barrier. H. pylori infection can stimulate gastric epithelial cells to produce inflammatory mediators such as interleukin (IL) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) [41, 42].

Reducing the incidence of adverse effects and, subsequently, compliance may improve, which may indirectly improve the H. pylori eradication rates.

In the case of L. reuteri, In vitro and in artificial gastric juice, H. pylori specifically co-aggregates with H. pylori without interfering with other commensal intestinal flora bacteria [43]. This specific binding may obscure H. pylori surface structures and impair Helicobacter motility. Pathogens that have aggregated are presumably no longer adhered to the gastric mucosa and are cleared from the stomach. Competition for specific binding proteins could be another mode of action [44].

According to findings of our study, distribution frequency of some AEs in the subjects receiving S. boulardii probiotic was significantly reduced after the intervention but, except for headache, no significant change was observed in the Lactobacillus reuteri-treated group. According to the findings, the most common AEs in the first week were vomiting, bitter taste in the mouth, epigastric discomfort, and insomnia, which were decreased after that time. However, no statistically significant difference was found between the studied groups at different times. Our findings were consistent with those of the studies by Pourmasoumi et al., and Lv et al., who showed that probiotic administration can reduce the AEs of anti H. pylori treatment [26, 28]. Also, Zojaji et al., discovered that using S. boulardii supplement significantly reduces AEs, such as nausea, diarrhea, epigastric discomfort, and bloating in the first and second weeks of treatment [27]. Furthermore, Cindoruk et al., in a study found that the AEs of epigastric discomfort and dyspepsia were significantly reduced in the group that received S. boulardii [32]. Moreover, Shavakhi et al., reported that incidence of diarrhea was significantly lower in the group that consumed combined probiotics containing Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, and Streptococcus thermophilus than the placebo group. On the other hand, incidence of abdominal pain was significantly higher in the probiotic group than the placebo group [33]. On the contrary, Frequency of nausea, vomiting, epigastric discomfort, and bitter taste was significantly reduced in the group that received oral supplement of Lactobacillus reuteri compared to the placebo group in the study by Poonyam et al. [34]. Also, Yu et al., in a meta-analysis found that Lactobacillus reduces treatment-related AEs [35]. Furthermore, Zhou et al., discovered that S. boulardii could significantly reduce treatments AEs, particularly diarrhea and constipation [36]. which were not in line with the results of our study.

Limitations of the study

One of the study's limitations is that it does not investigate the severity of Adverse effects caused by antibiotics. Furthermore, the term "Adverse effects" in this study is defined differently than its usual definition and refers to patients' symptoms and complaints about the side effects of the antibiotics during treatment and their persistence until two weeks after stopping antibiotics. Furthermore, in our country, simply receiving the code of ethics is sufficient to begin research, and for this reason, we began collecting samples after the ethics committee's approval.

Conclusion

In general, our findings revealed that the use of probiotic supplements containing S. boulardii could significantly reduce some of the AEs of H. pylori eradication therapy. But, the effectiveness of Lactobacillus reuteri (DSMZ 17648 strain) on these cases was not significant, and only the headache was remarkably reduced, which was in accordance with the previous evidence in the literature. Therefore, it is recommended to conduct future research with a larger sample size in order to investigate the effect of S. boulardii supplementation on eradicating H. pylori infection and reducing treatment AEs.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. Supplementary figures: The frequency distribution of side effects over time in the study groups.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

NN coordinated the experiments, FS performed the Statistical analysis and Interpretated the data, SN prepared the manuscript, TT revised the important intellectual content and Supervision, all authors reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by ZistTakhmir pharmaceutical company, Tehran, Iran.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. This study was approved by the Research Council and Ethics Committee of the Birjand University of Medical Sciences with the ethics code of IR.BUMS.REC.1398.305. It was also registered on the website of the Iranian registry of clinical trials (IRCT) with the following Number: IRCT20200106046021N1 on 14/01/2020 (https://en.irct.ir/trial/44865). Informed written consent was obtained from all the patients. No costs were imposed on patients. The drugs used in the study, as well as the dose administered to patients, had no AEs or toxicity. The final report and analysis were performed without the names of the participants in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hooi JK, Lai WY, Ng WK, Suen MM, Underwood FE, Tanyingoh D, Malfertheiner P, Graham DY, Wong VW, Wu JC. Global prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2017;153(2):420–429. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sjomina O, Heluwaert F, Moussata D, Leja M. Helicobacter pylori infection and nonmalignant diseases. Helicobacter. 2017;22:e12408. doi: 10.1111/hel.12408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uemura N, Okamoto S, Yamamoto S, Matsumura N, Yamaguchi S, Yamakido M, Taniyama K, Sasaki N, Schlemper RJ. Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(11):784–789. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa001999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wotherspoon AC, Ortiz-Hidalgo C, Falzon MR, Isaacson PG. Helicobacter pylori-associated gastritis and primary B-cell gastric lymphoma. The Lancet. 1991;338(8776):1175–1176. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)92035-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nishizawa T, Suzuki H. Mechanisms of Helicobacter pylori antibiotic resistance and molecular testing. Front Mol Biosci. 2014;1:19. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2014.00019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fiorini G, Zullo A, Vakil N, Saracino IM, Ricci C, Castelli V, Gatta L, Vaira D. Rifabutin triple therapy is effective in patients with multidrug-resistant strains of Helicobacter pylori. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2018;52(2):137–140. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thung I, Aramin H, Vavinskaya V, Gupta S, Park J, Crowe S, Valasek M. the global emergence of Helicobacter pylori antibiotic resistance. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;43(4):514–533. doi: 10.1111/apt.13497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang M. High antibiotic resistance rate: a difficult issue for Helicobacter pylori eradication treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(48):13432. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i48.13432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’morain C, Gisbert J, Kuipers E, Axon A, Bazzoli F, Gasbarrini A, Atherton J, Graham DY. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection—the Maastricht V/Florence consensus report. Gut. 2017;66(1):6–30. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Younes JA, van der Mei HC, van den Heuvel E, Busscher HJ, Reid G. Adhesion forces and coaggregation between vaginal staphylococci and lactobacilli. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(5):e36917. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lang C, Böttner M, Holz C, Veen M, Ryser M, Reindl A, Pompejus M, Tanzer J. Specific lactobacillus/mutans streptococcus co-aggregation. J Dent Res. 2010;89(2):175–179. doi: 10.1177/0022034509356246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McMillan A, Dell M, Zellar MP, Cribby S, Martz S, Hong E, Fu J, Abbas A, Dang T, Miller W. Disruption of urogenital biofilms by lactobacilli. Colloids Surf, B. 2011;86(1):58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2011.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gotteland M, Brunser O, Cruchet S. Systematic review: are probiotics useful in controlling gastric colonization by Helicobacter pylori? Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23(8):1077–1086. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02868.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vítor JM, Vale FF. Alternative therapies for Helicobacter pylori: probiotics and phytomedicine. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2011;63(2):153–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2011.00865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zou J, Dong J, Yu X. Meta-analysis: lactobacillus containing quadruple therapy versus standard triple first-line therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Helicobacter. 2009;14(5):449–459. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2009.00716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Francavilla R, Lionetti E, Castellaneta SP, Magistà AM, Maurogiovanni G, Bucci N, De Canio A, Indrio F, Cavallo L, Ierardi E. Inhibition of Helicobacter pylori infection in humans by Lactobacillus reuteri ATCC 55730 and effect on eradication therapy: a pilot study. Helicobacter. 2008;13(2):127–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2008.00593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dore MP, Cuccu M, Pes GM, Manca A, Graham DY. Lactobacillus reuteri in the treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection. Intern Emerg Med. 2014;9(6):649–654. doi: 10.1007/s11739-013-1013-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Emara MH, Mohamed SY, Abdel-Aziz HR. Lactobacillus reuteri in management of Helicobacter pylori infection in dyspeptic patients: a double-blind placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial. Ther Adv Gastroenterol. 2014;7(1):4–13. doi: 10.1177/1756283X13503514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holz C, Busjahn A, Mehling H, Arya S, Boettner M, Habibi H, Lang C. Significant reduction in helicobacter pylori load in humans with non-viable lactobacillus reuteri DSM17648: a pilot study. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins. 2015;7(2):91–100. doi: 10.1007/s12602-014-9181-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mehling H, Busjahn A. Non-viable Lactobacillus reuteri DSMZ 17648 (Pylopass™) as a new approach to Helicobacter pylori control in humans. Nutrients. 2013;5(8):3062–3073. doi: 10.3390/nu5083062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holz C, Busjahn A, Mehling H, Arya S, Boettner M, Habibi H, Lang C. Significant reduction in Helicobacter pylori load in humans with non-viable Lactobacillus reuteri DSM17648: a pilot study. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins. 2015;7(2):91–100. doi: 10.1007/s12602-014-9181-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saulnier DM, Santos F, Roos S, Mistretta T-A, Spinler JK, Molenaar D, Teusink B, Versalovic J. Exploring metabolic pathway reconstruction and genome-wide expression profiling in Lactobacillus reuteri to define functional probiotic features. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(4):e18783. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yadegar A, Mobarez AM, Alebouyeh M, Mirzaei T, Kwok T, Zali MR. Clinical relevance of cagL gene and virulence genotypes with disease outcomes in a Helicobacter pylori infected population from Iran. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;30(9):2481–2490. doi: 10.1007/s11274-014-1673-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yadegar A, Alebouyeh M, Zali MR. Analysis of the intactness of Helicobacter pylori cag pathogenicity island in Iranian strains by a new PCR-based strategy and its relationship with virulence genotypes and EPIYA motifs. Infect Genet Evol. 2015;35:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2015.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pourmasoumi M, Najafgholizadeh A, Hadi A, Mansour-Ghanaei F, Joukar F. The effect of synbiotics in improving Helicobacter pylori eradication: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Complement Ther Med. 2019;43:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2019.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lv Z, Wang B, Zhou X, Wang F, Xie Y, Zheng H, Lv N. Efficacy and safety of probiotics as adjuvant agents for Helicobacter pylori infection: a meta-analysis. Exp Ther Med. 2015;9(3):707–716. doi: 10.3892/etm.2015.2174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zojaji H, Ghobakhlou M, Rajabalinia H, Ataei E, Sherafat SJ, Moghimi-Dehkordi B, Bahreiny R. The efficacy and safety of adding the probiotic Saccharomyces boulardii to standard triple therapy for eradication of Helicobacter pylori; a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2013;2016(Suppl. 2011):S2099–S2104. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dore MP, Bibbo S, Pes GM, Francavilla R, Graham DY. Role of probiotics in Helicobacter pylori eradication: lessons from a study of Lactobacillus reuteri strains DSM 17938 and ATCC PTA 6475 (Gastrus®) and a proton-pump inhibitor. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2019 doi: 10.1155/2019/3409820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buckley M, Lacey S, Doolan A, Goodbody E, Seamans K. The effect of Lactobacillus reuteri supplementation in Helicobacter pylori infection: a placebo-controlled, single-blind study. BMC Nutr. 2018;4(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s40795-018-0257-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D, The CG CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMC Med. 2010;8(1):18. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-8-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ibrahim NH, Gomaa AA, Abu-Sief MA, Hifnawy TM, Tohamy MAE. The use of different laboratory methods in diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection; a comparative study. Life Sci J-Acta Zhengzhou Univ Overseas Ed. 2012;9(4):249–259. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cindoruk M, Erkan G, Karakan T, Dursun A, Unal S. Efficacy and safety of Saccharomyces boulardii in the 14-day triple anti-Helicobacter pylori therapy: a prospective randomized placebo-controlled double-blind study. Helicobacter. 2007;12(4):309–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2007.00516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shavakhi A, Tabesh E, Yaghoutkar A, Hashemi H, Tabesh F, Khodadoostan M, Minakari M, Shavakhi S, Gholamrezaei A. The effects of multistrain probiotic compound on bismuth-containing quadruple therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection: a randomized placebo-controlled triple-blind study. Helicobacter. 2013;18(4):280–284. doi: 10.1111/hel.12047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Poonyam P, Chotivitayatarakorn P, Vilaichone RK. High effective of 14-day high-dose PPI-bismuth-containing quadruple therapy with probiotics supplement for Helicobacter pylori eradication: a double blinded-randomized placebo-controlled study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2019;20(9):2859–2864. doi: 10.31557/APJCP.2019.20.9.2859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu M, Zhang R, Ni P, Chen S, Duan G. Efficacy of Lactobacillus-supplemented triple therapy for H. pylori eradication: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(10):e0223309. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0223309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou B-G, Chen L-X, Li B, Wan L-Y, Ai Y-W. Saccharomyces boulardii as an adjuvant therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication: a systematic review and meta-analysis with trial sequential analysis. Helicobacter. 2019;24(5):e12651. doi: 10.1111/hel.12651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Czerucka D, Piche T, Rampal P. Yeast as probiotics–Saccharomyces boulardii. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26(6):767–778. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sakarya S, Gunay N. S accharomyces boulardii expresses neuraminidase activity selective for α2, 3-linked sialic acid that decreases Helicobacter pylori adhesion to host cells. APMIS. 2014;122(10):941–950. doi: 10.1111/apm.12237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McFarland LV. Systematic review and meta-analysis of Saccharomyces boulardii in adult patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(18):2202. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i18.2202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Buts J-P, Bernasconi P, Vaerman J-P, Dive C. Stimulation of secretory IgA and secretory component of immunoglobulins in small intestine of rats treated with Saccharomyces boulardii. Dig Dis Sci. 1990;35(2):251–256. doi: 10.1007/BF01536771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Suerbaum S, Michetti P. Helicobacter pylori infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(15):1175–1186. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee J, Choi S, Park J, Shin J, Joo Y. The effect of Saccharomyces boulardii as an adjuvant to the 14-day triple therapy for eradication of Helicobacter pylori. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:257. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lang C. DSMZ17648 specifically co-aggregates H. pylori under in vitro conditions. 2011. unpublished work.

- 44.Mukai T, Asasaka T, Sato E, Mori K, Matsumoto M, Ohori H. Inhibition of binding of Helicobacter pylori to the glycolipid receptors by probiotic Lactobacillus reuteri. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2002;32(2):105–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2002.tb00541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Supplementary figures: The frequency distribution of side effects over time in the study groups.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.