Abstract

Objective:

To compare the effectiveness of preoperative administration of ibuprofen and piroxicam on orthodontic pain experienced after separator placement.

Materials and Methods:

Ninety patients aged between 13 years 9 months and 18 years 2 months who were to undergo fixed appliance orthodontic treatment were enrolled in this double-blind, parallel-arm, prospective study. Patients were evenly and randomly distributed to any of three experimental groups, as follows: (1) administration of placebo, (2) administration of 400 mg ibuprofen, and (3) administration of 20 mg piroxicam; medications were administered 1 hour before separator placement. The pain perceived was recorded by the patients on a linear and graded Visual Analogue Scale at time intervals of 2 hours; 6 hours; nighttime on the day of appointment; 24 hours after the appointment; and 2 days, 3 days, and 7 days after separator placement during each of the four activities (viz, chewing, biting, fitting front teeth, and fitting back teeth).

Results:

The results revealed that preoperative administration of 20 mg of piroxicam 1 hour prior to separator placement resulted in a significant decrease in pain levels at 2 hours, 6 hours, nighttime, and 24 hours and on the second and third days after separator placement, compared to patients on a placebo or ibuprofen.

Conclusions:

Premedication with 20 mg of piroxicam results in significantly decreased pain experienced, compared to premedication with 400 mg of ibuprofen or placebo. Usage of 20 mg of piroxicam 1 hour prior to separator placement is recommended.

Keywords: NSAIDs, Orthodontic pain, Piroxicam, Ibuprofen

INTRODUCTION

Pain is defined as an unpleasant emotional experience usually initiated by a noxious stimulus and transmitted over a specialized neural network to the central nervous system (CNS), where it is interpreted as such.1 The noxious stimulus of orthodontic pain is the compression of the periodontal ligament by the tooth, resulting in an inflammatory response mediated by release of chemical mediators such as histamines, bradykinins, serotonin, substance P, cytokines, and prostaglandins.2,3

Surveys of orthodontic patients have brought to light that pain is among the most cited negative effects of orthodontic therapy, even when compared to that experienced after other invasive procedures, such as extractions, etc.4–8 There have been a few reported cases in which this pain reaction has proved to be a major deterrent to orthodontic treatment and an important reason for discontinuation of treatment.9 There exist differences among patients in the perceived pain; these differences are dependent on factors such as individual pain threshold, the magnitude of force applied, age, gender, cultural differences, previous pain experienced, and present emotional state and stress.10–15 It has been found10,16,17 that pain is present within 4 hours after the orthodontic procedure and continues for at least 24 hours, dissipating by day 7 after the orthodontic procedure. This is in agreement with the findings of other studies,5,18 which have found the greatest need for analgesics to exist within 3 days after archwire placement. Bergius et al19 found that 87% of participants reported pain on the first evening, but the most intense pain was reported to occur the day after archwire placement.

As a result of the release of the aforementioned chemical mediators, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAID) medication has been suggested14 as the gold standard in decreasing postoperative orthodontic pain. Other alternative methods, such as the application of low-level laser therapy to periodontal tissue,20 transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation,21,22 anesthetic gels, bite wafers,23 and vibratory stimulation of the periodontal ligament,24 have been shown to be effective at reducing orthodontic pain.

White25 reported that 63% of patients who chewed an analgesic chewing gum immediately after archwire changes experienced less discomfort than usual. Ngan et al.15 compared the effectiveness of 650 mg of aspirin, 400 mg of ibuprofen, and placebo for the control of orthodontic pain caused by either separators or initial archwire placement. They concluded that ibuprofen was the preferred analgesic to decrease the pain that is associated with orthodontic treatment.

Recent research26 has focused more on preoperative administration of analgesics, based on the hypothesis that blockage of immediate peripheral sensitization would prevent the subsequent central sensitization and thus decrease postoperative pain. The objective of preoperative administration of analgesics is to block the afferent nerve impulses before they reach the CNS, giving rise to subsequent central sensitization. Upon administration of NSAIDs, the favorable aspect is that the body has enough time to absorb and distribute the medication before tissue injury and consequent production of the primary and secondary messengers of inflammation.

A brief review of literature27–29 reveals that preoperative administration of NSAIDs prior to a minor oral surgical procedure reduces the pain intensity and delays both the onset and peak pain levels.

Law et al.30 and Bernhartd et al.31 have reported that preoperative administration of ibuprofen 1 hour before the procedure decreases the pain level from 2 hours after bonding until nighttime. Polat et al.32 and Polat and Karaman33 evaluated the effects of one preemptive dose of ibuprofen (400 mg), naproxen sodium (550 mg), or placebo given 1 hour before archwire placement. Patients taking naproxen sodium had significantly less pain than did those in the ibuprofen or placebo groups at 2 hours, 6 hours, and nighttime. Although the pretreatment ibuprofen group showed a trend for decreased pain experienced at 2 hours and 6 hours, there were no statistically significant differences between the placebo and ibuprofen groups.

With regard to preoperative administration of analgesics for pain control in orthodontic therapy, the efficacy of only aspirin, ibuprofen, and naproxen sodium has been studied to date.31,32 Piroxicam is an oxicam, a nonselective COX inhibitor. It exhibits a long mean half-life of 50–60 hours, which permits once-daily dosing. The recommended dosage of piroxicam is 20–30 mg once daily. The advantage of piroxicam is the significantly lower gastrointestinal irritation it causes, as is commonly observed with administration of aspirin, ibuprofen, or naproxen sodium.34

Unfortunately, there is no widely accepted standard of care that is followed for managing orthodontic pain. The aim of this prospective, double-blind, parallel-arm study is to evaluate the efficacy of preoperative administration of ibuprofen and piroxicam with regard to orthodontic pain after separator placement.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Ninety patients (45 males and 45 females) who were scheduled to receive fixed orthodontic treatment at the Department of Orthodontics & Dentofacial Orthopedics (Hitkarini Dental College & Hospital, Jabalpur, India) agreed to participate in the study. The sample size was measured after conducting a power analysis, keeping in mind the previous publications on orthodontic pain control. Ethical clearance was obtained from the institution's Ethical Committee (internal review board), which oversees ethical clinical practice at the institute.

The following selection criteria were established: patients must be (1) at least 13 years of age and not older than 20 years of age; (2) beginning orthodontic treatment for the first time; (3) reporting no contraindications or adverse reactions related to ibuprofen and piroxicam; (4) currently not using any antibiotics; and (5) meeting a minimum weight requirement of 88 pounds, as per Food and Drug Administration–approved over-the-counter pediatric dosage labeling guidelines. In addition, patients were required to provide written informed consent for participation in the study.

Thirty patients were randomly assigned to the three experimental groups, namely, group A (lactose capsule), group B (ibuprofen, 400 mg), and group C (piroxicam, 20 mg). In all the three of the groups, all of the patients were administered only one tablet 1 hour prior to separator placement. The investigational drug pharmacy at the institute dispensed the drugs so that the investigator would be blinded to the experimental group.

Data Collection

The scale selected to measure the degree of discomfort was the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS).35 Routine posttreatment instructions were given to the patients, and the 100-mm horizontal VAS scale was given in the form of a questionnaire booklet to all patients, with possible answers of “no pain at all” (0 mm) and “worst pain experienced” (100 mm). Questionnaire booklets were provided in the form of a 7-page booklet. The patients were instructed to mark the degree of discomfort at the appropriate time intervals by placing a mark on the scale and indicating the perceived severity of pain/discomfort during masticatory activities such as biting, chewing, fitting back teeth together, and fitting front teeth together. These were recorded by the patients at the following intervals: 2 hours posttreatment; 6 hours posttreatment; bedtime on the day of the appointment; 24 hours after the appointment; and 2 days, 3 days, and 7 days after separator placement. All patients were instructed to return their booklets at the next appointment (after 1 week).

Patients were advised against taking any other analgesic medications. If any other medications were taken by the patients within this time frame they were asked to make a mention of the date, dosage, time, and name of the drug taken in the booklet.

All of the 90 patients who participated in the study returned their questionnaires. None of them had resorted to the usage of any kind of ‘rescue medication.’ The patients were evenly distributed among the three experimental groups.

Statistics

All statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences for Windows (v. 10.0; SPSS, Chicago, Ill). Descriptive analysis were performed and calculated for pain scores at each time interval as defined earlier for the experimental groups. Comparisons between the three experimental groups in four parameters were made using repeated-measures two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). If the results of repeated-measures ANOVA were found to be significant, one-way ANOVA was carried out for each time interval, and multiple comparisons were made with Tukey Honestly Significantly Different test. In this study, the level of significance for repeated-measures ANOVA and Tukey tests was determined as P < .05.

RESULTS

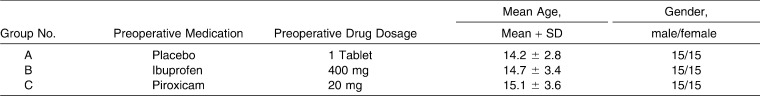

Descriptive statistics for the experimental groups are given in Table 1. There was no statistical difference between the mean ages of the subjects in the three experimental groups (P < .05).

Table 1.

Experimental Groups with Preoperative Analgesic, Mean Age, and Sex Distribution

Differences in Pain Experienced Between Experimental Groups in “Pain on Chewing”

The results of ANOVA demonstrated significant differences in pain experienced on chewing at all time intervals after separator placement (P < .05); repeated comparisons revealed that at 6 hours, nighttime, 24 hours, and 2 days posttreatment, patients who were administered piroxicam experienced less “pain on chewing” compared with patients in the placebo group (P < .05) (Figure 1; Table 2).

Figure 1.

Mean pain scores for “chewing,” according to condition and time.

Table 2.

Mean Pain Scores of Experimental Groups and their Standard Deviations (SDs; denoted as Mean Score ± SD)

At 24 hours and 2 days posttreatment, patients administered 20 mg of piroxicam preoperatively showed significantly decreased pain scores compared with the placebo group (P < .05) (Figure 1; Table 2).

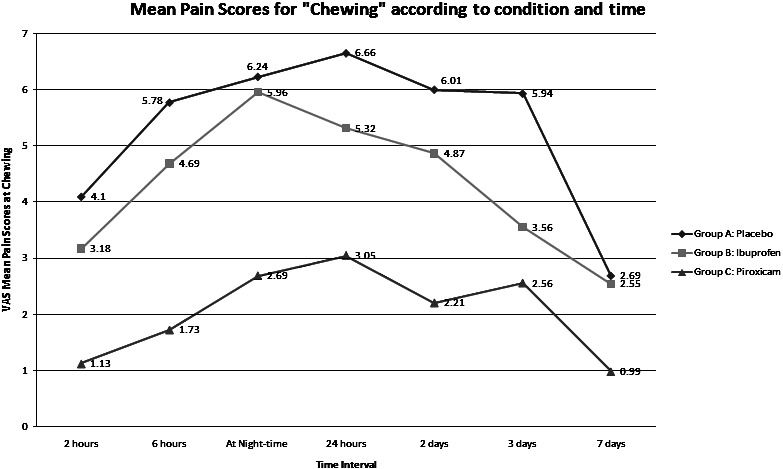

Differences in Pain Experienced Between Experimental Groups in “Pain on Biting”

The results of ANOVA reveal significant differences among the ibuprofen and piroxicam groups and the placebo group at the 2-hour and 6-hour intervals with reference to the placebo group (P < .05) (Figure 2; Table 2). Calculations of pain scores at nighttime and 24 hours and 2 days after the separator placement appointment showed significant differences between the placebo, ibuprofen, and piroxicam groups (P < .05) (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Mean pain scores for “biting,” according to condition and time.

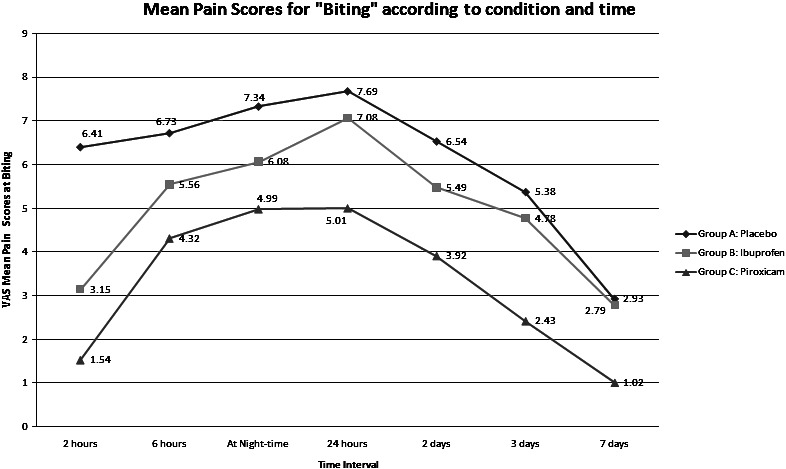

Differences in Pain Experienced Between Experimental Groups in “Pain on Fitting the Front Teeth”

With respect to pain experienced on fitting front teeth, patients administered piroxicam and ibuprofen showed significantly less pain with regard to this activity within the placebo group at 2-hour, 6-hour, and nighttime intervals (P < .05). However, at the 24-hour and 2-day and 3-day time intervals, patients in the piroxicam group reported significantly less pain than did patients in the ibuprofen group (P < .05) (Figure 3; Table 2).

Figure 3.

Mean pain scores for “fitting front teeth,” according to condition and time.

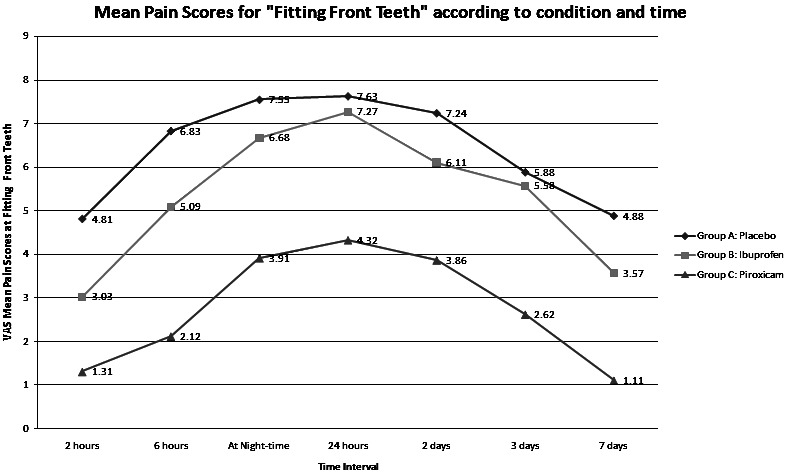

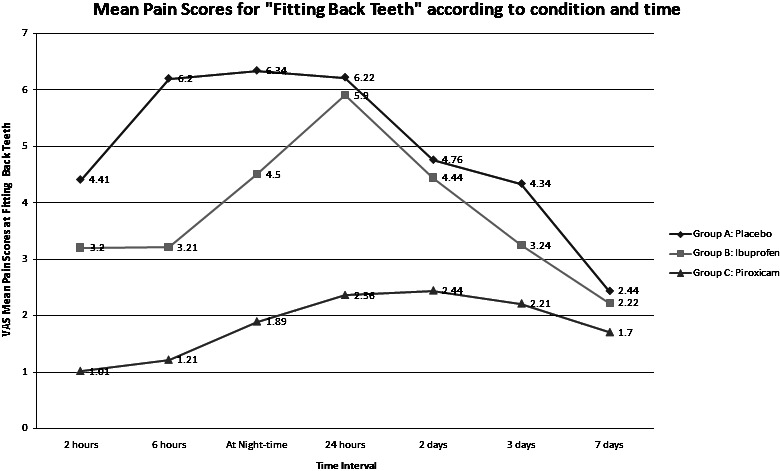

Differences in Pain Experienced Between Experimental Groups in “Pain on Fitting the Back Teeth”

On measuring the differences in pain experienced on fitting the back teeth at the 2-hour and 6-hour intervals, patients on the placebo reported higher pain scores than did patients on ibuprofen and piroxicam (Figure 4; Table 2). However, at the 2-day and 3-day time intervals, group C showed lower pain scores than did group A or group B (P < .05). At all times patients in the placebo group showed the highest VAS scores, while patients on piroxicam showed the lowest VAS scores (Table 2).

Figure 4.

Mean pain scores for “fitting back teeth,” according to condition and time.

DISCUSSION

This randomized control trial was conducted using a patient pool of 90 individuals who were scheduled to undergo fixed appliance therapy. Three experimental groups were formed: Group A patients were administered a placebo (lactose capsule), group B patients were administered 400 mg of ibuprofen, and group C patients were administered 20 mg of piroxicam; in all groups, medications were administered preoperatively 1 hour before separator placement. None of the patients resorted to the use of any ‘rescue medications.’

To measure the pain scores, patients were asked to comment in their VAS booklets regarding the perceived degree of discomfort they experienced during the four masticatory activities (biting, chewing, fitting the front teeth, and fitting the back teeth) at the specified time intervals. The incidence and severity of pain were recorded at 2 hours; 6 hours; nighttime; 24 hours; and 2 days, 3 days, and 7 days after separator placement. Since there is no objective scale with which to measure the intensity of pain perceived, the VAS scale was chosen because it has been shown to be the most reliable and accurate tool in the evaluation of subjective experiences such as pain.19,35

The experimental groups had been formed in such a way that there were an equal number of male and female patients in each group (Table 1). Care was taken that the patients with similar malocclusions and social background were selected.15

The results of this study show that pain levels increased from 2 hours to a maximum in the first 24 hours and then gradually declined from peak pain scores through 7 days after separator placement. This finding is in accordance with those of previous investigations by Wilson et al.17 and Law et al.30

The results of this investigation reveal that patients who had been administered 20 mg of piroxicam 1 hour preoperatively exhibited significantly lower pain scores than did patient in the other groups until 3 days after separator placement. This finding could be attributed to the absorption of the NSAIDs and the high bioavailability of the drug, which blocks the synthesis of prostaglandins and consequently decreases the inflammatory response.

According to the results obtained in this study, it was observed that in comparison with patients in the placebo group, the patients on preoperative courses of ibuprofen and piroxicam experienced lower pain levels at all time intervals; however, the measurements were statistically significant for the piroxicam group at all time intervals.

Previous studies on the preoperative use of analgesics have investigated the use of ibuprofen and naproxen sodium only. Law et al.30 observed that preemptive ibuprofen significantly decreased pain upon chewing at 2 hours, compared with postoperative ibuprofen or placebo. Polat et al.32 found that naproxen sodium significantly decreased the perceived pain level compared to ibuprofen.

Piroxicam has a long mean half-life and, hence, has a longer duration of action than ibuprofen.34 Although single preoperative doses of 20 mg of piroxicam and 400 mg of ibuprofen were similar in terms of onset of action, piroxicam provided pain relief for a longer duration, until the third day; this allows for a single preoperative dose, without the need for an additional postoperative dose.

The major concern with using NSAIDs to manage orthodontic pain is that it may interfere with tooth movement by inhibiting cyclo-oxygenase activity and thus prostaglandin production. A number of animal studies36,37 have demonstrated decreased rates of tooth movement with NSAID administration. However, the use of NSAIDs is only of concern in chronic users and not when taken at modest doses over the 3–4 days following treatment.23

This study was designed to evaluate the analgesic efficacy of preoperative usage of piroxicam vis-à-vis ibuprofen; it was found that piroxicam exhibited a superior analgesic effect compared to ibuprofen and the placebo. This study also aimed to answer a question raised in a previous study; we evaluated a longer-acting NSAID (piroxicam) compared to ibuprofen and found that there was significant reduction in pain levels at the 2- and 3-day time intervals. However, further studies on the safety of NSAID usage and longer-acting NSAIDs are recommended.

CONCLUSIONS

Preoperative administration of 20 mg of piroxicam 1 hour prior to separator placement resulted in a significant decrease in pain levels at 2 hours; 6 hours; nighttime; 24 hours; and day 2 and day 3 after separator placement, compared to patients receiving a placebo or ibuprofen.

Piroxicam has a longer duration of analgesic effect compared to ibuprofen.

Use of 20 mg of piroxicam 1 hour preoperatively (only) is recommended for adequate pain control after separator placement.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bennett C. R. Pain. In: Bennett C. R, editor. Monheim's Local Anesthesia and Pain Control in Dental Practice 7th ed. Delhi, India: CBS Publishers; 1990. pp. 20–21. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Skjelbred P, Lokken P. Pain and other sequelae after surgery—mechanisms and management. In: Andreasen J. O, Petersen J. K, Laskin D. M, editors. Textbook and Color Atlas of Tooth Impactions. Copenhagen, Denmark: Munksgaard; 1997. pp. 369–437. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krishnan V. Orthodontic pain: from causes to management—a review. Eur J Orthod. 2007;29:170–179. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjl081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oliver R. G, Knapman Y. M. Attitudes to orthodontic treatment. Br J Orthod. 1985;12:179–188. doi: 10.1179/bjo.12.4.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones M, Chan C. The pain and discomfort experienced during orthodontic treatment: a randomized controlled clinical trial of two initial aligning arch wires. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1992;102:373–381. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(92)70054-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lew K. K. Attitudes and perception of adults towards orthodontic treatment in an Asian community. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1993;21:31–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1993.tb00715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kvam E, Bondevik O, Gjerdet N. R. Traumatic ulcers and pain during orthodontic treatment. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1989;17:154–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1989.tb00012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scheurer P, Firestone A, Burgin W. Perception of pain as a result of orthodontic treatment with fixed appliances. Eur J Orthod. 1996;18:349–357. doi: 10.1093/ejo/18.4.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oliver R, Knapman Y. Attitudes to orthodontic treatment. Br J Orthod. 1985;12:179–188. doi: 10.1179/bjo.12.4.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ngan P, Kess B, Wilson S. Perception of discomfort by patients undergoing orthodontic treatment. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1989;96:47–53. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(89)90228-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown D. F, Moerenhout R. G. The pain experience and psychological adjustment to orthodontic treatment of preadolescents, adolescents, and adults. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1991;100:349–356. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(91)70073-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scheurer P. A, Firestone A. R, Burgin W. B. Perception of pain as a result of orthodontic treatment with fixed appliances. Eur J Orthod. 1996;18:349–357. doi: 10.1093/ejo/18.4.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Firestone A. R, Scheurer P. A, Burgin W. B. Patients' anticipation of pain and pain-related side effects and their perception of pain as a result of orthodontic treatment with fixed appliances. Eur J Orthod. 1999;21:387–396. doi: 10.1093/ejo/21.4.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bergius M, Kiliaridis S, Berggren U. Pain in orthodontics. A review and discussion of the literature. J Orofac Orthop. 2000;61:125–137. doi: 10.1007/BF01300354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ngan P, Wilson S, Shanfeld J, Amini H. The effect of ibuprofen on the level of discomfort in patients undergoing orthodontic treatment. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1994;106:88–95. doi: 10.1016/S0889-5406(94)70025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sergl H. G, Klages U, Zentner A. Pain and discomfort during orthodontic treatment: causative factors and effects on compliance. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1998;114:684–691. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(98)70201-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilson S, Ngan P, Kess B. Time course of the discomfort in young patients undergoing orthodontic treatment. Pediatr Dent. 1989;11:107–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones M. L. An investigation into the initial discomfort caused by placement of an archwire. Eur J Orthod. 1984;6:48–54. doi: 10.1093/ejo/6.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bergius M, Berggren U, Kiliaridis S. Experience of pain during an orthodontic procedure. Eur J Oral Sci. 2002;110:92–98. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0722.2002.11193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lim H. M, Lew K. K, Tay D. K. A clinical investigation of the efficacy of low level laser therapy in reducing orthodontic postadjustment pain. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1995;108:614–622. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(95)70007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roth P. M, Thrash W. J. Effect of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for controlling pain associated with orthodontic tooth movement. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1986;90:132–138. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(86)90045-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weiss D. D, Carver D. M. Transcutaneous electrical neural stimulation for pain control. J Clin Orthod. 1994;28:670–671. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Proffit W. R. Contemporary Orthodontics 3rd ed. St Louis, Mo: Mosby; 2000. pp. 280–281. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marie S. S, Powers M, Sheridan J. J. Vibratory stimulation as a method of reducing pain after orthodontic appliance adjustment. J Clin Orthod. 2003;37:205–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.White L. W. Pain and cooperation in orthodontic treatment. J Clin Orthod. 1984;18:572–575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Woolf C. J. Generation of acute pain: central mechanisms. Br Med Bull. 1991;47:523–533. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a072490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jackson D, Moore P, Hargreaves K. Postoperative nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication for the prevention of postoperative dental pain. J Am Dent Assoc. 1989;119:641–647. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8177(89)95018-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dionne R. A, Cooper S. Evaluation of preoperative ibuprofen for postoperative pain after removal of third molars. Oral Surg Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1978;45:851–856. doi: 10.1016/s0030-4220(78)80004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dionne R. A, Campbell R. A, Cooper S. A, Hall D. L, Buckingham B. Suppression of postoperative pain by preoperative administration of ibuprofen in comparison to placebo, acetaminophen, and acetaminophen plus codeine. J Clin Pharmacol. 1983;23:37–43. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1983.tb02702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Law S. L. S, Southard K. S, Law A. S, Logan H. L, Jakobsen J. R. An evaluation of ibuprofen treatment of pain associated with orthodontic separator placement. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2000;118:629–635. doi: 10.1067/mod.2000.110638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bernhartd M. K, Southhard K. A, Batterson K. D, Logan H. L, Baker K. A, Jakobsen J. R. The effect of preemptive and/or postoperative ibuprofen therapy for orthodontic pain. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2001;120:20–27. doi: 10.1067/mod.2001.115616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Polat O, Karaman A. I, Durmus E. Effects of preoperative ibuprofen and naproxen sodium on orthodontic pain. Angle Orthod. 2005;75:791–796. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2005)75[791:EOPIAN]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Polat O, Karaman A. I. Pain control during fixed orthodontic appliance therapy. Angle Orthod. 2005;75:214–219. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2005)075<0210:PCDFOA>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Furst D. E, Munster T. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, disease modifying antirheumatic drugs, non-opioid analgesics & drugs used in gout. In: Katzung B. G, editor. Basic & Clinical Pharmacology 8th ed. New York, NY: Lange-McGraw Hill; 2001. pp. 596–624. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sriwatanakul K, Kelvie W, Lasagna L, Calimlim J. F, Weis O. F, Mehta G. Studies with different types of visual analog scales for measurement of pain. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1983;34:234–239. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1983.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Walker J. B, Buring S. M. NSAID impairment of orthodontic tooth movement. Ann Pharmacother. 2001;35:113–115. doi: 10.1345/aph.10185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kehoe M. J, Cohen S. M, Zarrinnia K, Cowan A. The effect of acetaminophen, ibuprofen, and misoprostol on prostaglandin E2 synthesis and the degree and rate of orthodontic tooth movement. Angle Orthod. 1996;66:339–349. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1996)066<0339:TEOAIA>2.3.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]