ABSTRACT

Vaccinating children against COVID-19 is critical as a public health strategy in order to reach herd immunity and prevent illness among children and adults. The aim of the study was to identify correlation between willingness to vaccinate children under 12 years old, and vaccination rate for adult population in Canada, the United States, and Israel. This was a secondary analysis of a cross-sectional survey study (COVID-19 Parental Attitude Study) of parents of children 12 years and younger presenting to 12 pediatric emergency departments (EDs). Parental reports of willingness to vaccinate against COVID-19 when vaccines for children will be approved was correlated to country-specific rate of vaccination during December 2020–March 2021, obtained from ourworldindata.org. Logistic regression models were fit with covariates for week and the corresponding vaccine rate. A total of 720 surveys were analyzed. In Canada, administering mostly first dose to the adult population, willingness to vaccinate children was trending downward (correlation = −0.28), in the United States, it was trending upwards (correlation = 0.21) and in Israel, initially significant increase with decline shortly thereafter (correlation = 0.06). Odds of willingness to vaccinate in Canada, the United States, and Israel was OR = 0.82, 95% CI = 0.63–1.07, OR = 1.24, 95% CI = 0.99–1.56, and OR = 1.03, 95% CI = 0.95–1.12, respectively. A robust population-based vaccination program as in Israel, and to a lesser degree the United States, led to increasing willingness by parents to vaccinate their children younger than 12 years against COVID-19. In Canada, slow rate of vaccination of the adult population was associated with lower willingness to vaccinate children.

KEYWORDS: COVID-19, pediatrics, vaccine, willingness to vaccinate, vaccine hesitancy

Introduction

The international response to COVID-19 included more than 120 candidate SARS-CoV-2 vaccines and a varied worldwide implementation. Two messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines received emergency use authorization (EUA) by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) by December 2020.1

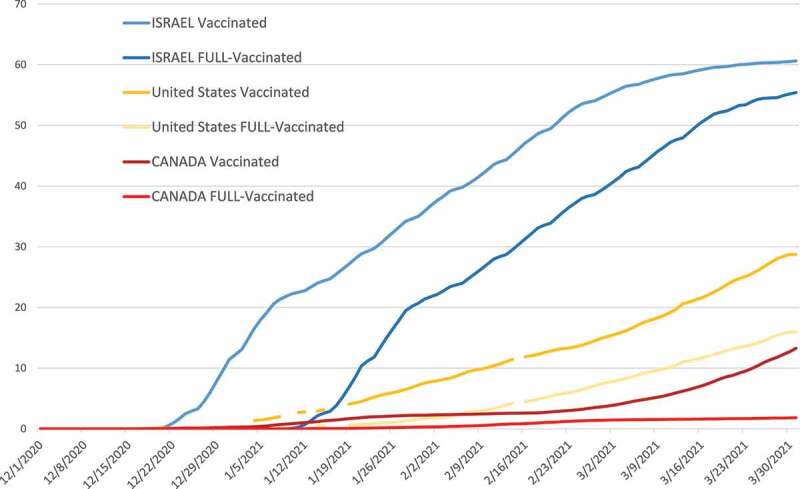

Israel was one of the first countries to mass-vaccinate its citizens and between December 19, 2020 and March 14, 2021, the majority of eligible health-care workers were vaccinated at least once,2 followed by a widespread vaccination of the entire population of Israel,3 reaching more than 90% of the elderly within a couple of months, then providing free access to vaccination to every citizen over 16 years old.4 In the United States, from December 14, 2020 to March 1, 2021, over 51 million residents received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine,5 prioritizing the elderly and health-care professionals. In Canada, initial vaccine supply was limited, leading to prioritization of those receiving the vaccine,6 and a decision to delay second dose administration by four months from the first vaccine in order to vaccinate the majority of the population with one dose7 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Rate of vaccination with first dose and second dose in Israel, the United States, and Canada during the study period (Source: ourworldindata.org).

The aim of this study was to determine the correlation between a country’s rate of vaccinating the population and willingness of parents to vaccinate their children under 12 years against COVID-19, once vaccines are available for the pediatric population. We hypothesize that availability of vaccines and implementation of a mass-vaccine program among adults, together with witnessing safety of vaccines, are associated with enhanced willingness to vaccinate children.

Participants and methods

Sample and procedures

This cross-sectional study was part of the COVID-19 Parental Attitude Study (COVIPAS) of caregivers presenting for emergency care for their children during the era of COVID-19. This subanalysis included parents that arrived to one of 12 pediatric emergency departments (EDs) in the United States (Denver, Los Angeles, Dallas, Seattle, Atlanta), Canada (Vancouver, Saskatoon, Edmonton, Calgary), and Israel (Zerifin, Hedera, Safed) with children under 12 years of age. One parent for each child was asked to complete an online survey while in the ED – either by a health care provider in the ED or in response to flyers in their room. Once a caregiver selected their study site from the online platform, consent for participation was considered completed. This study was approved by each site’s local Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Measures

The study-specific questionnaire was developed to include questions regarding demographic characteristics, information on symptoms leading to the ED visit, and caregiver attitudes about vaccinating against COVID-19. We specifically asked parents to respond to the following: “Vaccine/immunization for Coronavirus (COVID-19) will be available soon. Would you give it to your child?”

The objective of this substudy analysis was to determine caregivers’ perspectives on planned vaccination of their children based on their country’s pace of vaccinating against COVID-19 (first and second dose). The survey took about 15 minutes to complete. We have previously described the development and validation of the original survey.8

Country immunization data

For this study we obtained daily data on rate of vaccination among the population in each country between December 1, 2020 to March 31, 2021 (total 19 weeks) from the ourworldindata.org website. [https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus#coronavirus-country-profiles].

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics and frequencies were used to describe relevant variables overall and in each country. Vaccination rates as well as willingness to vaccinate children by their parents (survey) were calculated as a weekly average during the relevant study period. Response rates and vaccine rates were plotted over time with a LOES smoothing function and correlation between time series was calculated with Pearson correlation coefficients. To further assess the relationship between population vaccine rate and response to willingness to vaccinate, logistic regression models were fit with covariates for week and the corresponding vaccine rate. All models included interaction term with country to provide stratified estimates. Results are summarized as odds ratios for 5% increase in vaccine rate and with marginal predicted probabilities. A sensitivity analysis using the same model but adjusting for child’s age, who completed the survey (mother or father) and whether the child had up to date vaccination was conducted.

We then conducted a simulated analysis of anticipated rate of parental willingness to vaccinate children under 12 years against COVID-19 if the same trend discovered in our study would have continued to vaccinate 100% of the adult population against COVID-19 in each country.

All analyses were conducted using R statistical software version 4.0.3.

Results

Population characteristics

A total of 797 surveys were completed for children under 12 years. We excluded 17 (2.1%) that were not completed by parents (mother or father) and 60 (7.5%) that had no response to the willingness to vaccinate question. There were 441 surveys (61.3%) from Canada, 112 (15.5%) from the United States and 167 (23.2%) from Israel.

The study population from each country is presented in Table 1. Children were 5 years old on average, and just over half were male. Those in United States and Canada more frequently had chronic illness and used medications regularly. About 90% of children in each country had up to date immunization. Parents were generally over 35 years old and were moderately concerned about losing work, child losing school, and COVID-19 risks. Parents in Israel reported higher levels of concern.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics by country

| Surveys (720) | Total population |

Canada | Israel | United States | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child | |||||

| Child’s mean age in years (SD) | 720 | 5.13 (3.71) | 5.45 (3.78) | 4.55 (3.45) | 4.76 (3.71) |

| Child’s gender female | 720 | 321 (44.6%) | 201 (45.6%) | 67 (40.1%) | 53 (47.3%) |

| Child has chronic illness | 720 | 88 (12.2%) | 51 (11.6%) | 8 (4.79%) | 29 (25.9%) |

| Child uses chronic medication | 720 | 96 (13.3%) | 54 (12.2%) | 10 (5.99%) | 32 (28.6%) |

| Child’s immunizations up to date | 717 | 644 (89.8%) | 396 (89.8%) | 144 (87.8%) | 104 (92.9%) |

| Caregiver | |||||

| Completed by mother | 720 | 524 (72.8%) | 334 (75.7%) | 96 (57.5%) | 94 (83.9%) |

| Caregiver’s age | 703 | 36.9 (6.53) | 38.0 (6.26) | 35.6 (5.92) | 34.6 (7.49) |

| Caregiver has higher than high school education | 706 | 583 (82.6%) | 394 (91.4%) | 107 (65.6%) | 82 (73.2%) |

| Level of concern about child having COVID-19 (Likert Scale 0–10) | 660 | 2.59 (3.47) | 1.96 (3.06) | 4.66 (3.79) | 2.46 (3.62) |

| Level of concern about caregiver having COVID-19 (Likert Scale 0–10) | 652 | 2.29 (3.21) | 1.78 (2.81) | 4.04 (3.63) | 2.17 (3.39) |

| Level of concern about losing work (Likert Scale 0–10) | 640 | 3.21 (3.68) | 3.11 (3.61) | 3.87 (3.96) | 2.80 (3.56) |

| Level of concern about child losing school (Likert Scale 0–10) | 639 | 2.92 (3.66) | 2.50 (3.28) | 4.43 (4.19) | 2.69 (3.87) |

| Caregiver believe in social distancing as a good public health measure | 672 | 616 (91.7%) | 386 (92.1%) | 130 (90.3%) | 100 (91.7%) |

| Caregiver had lost income due to COVID-19 | 668 | 265 (39.7%) | 153 (36.5%) | 70 (49.3%) | 42 (39.3%) |

Willingness to vaccinate

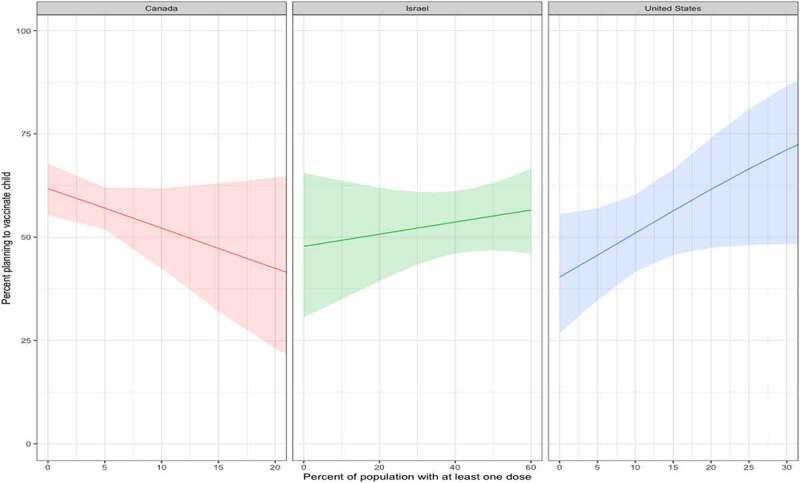

Figure 2 represents the rate of vaccination in each country for the first dose and the second dose of COVID-19 vaccine, as well as the trend in willingness of parents to vaccinate their children in the study period. In Canada, where vaccination was mostly limited to first dose during the study period, willingness to vaccinate children under 12 was trending downward(correlation = −0.28), whereas in the United States, it was trending upwards (correlation = 0.21). In Israel, the initial trend was a significant increase in willingness to vaccinate children; however, the willingness declined shortly thereafter (correlation = 0.06).

Figure 2.

Rate of population vaccinated (one dose of COVID-19 vaccine), fully vaccinated (two dosages) and rate of willingness to vaccinate children based on current study.

The odds ratios for change in willing to vaccinate, for every 5% increase in population vaccination rate (both by single and double dose), by each country is presented in Table 2. While none of the countries showed a significant change, the odds of willingness to vaccinate decreased in Canada (OR = 0.82, 95% CI = 0.63–1.07), and increased in the United States (OR = 1.24, 95% CI = 0.99–1.56). In both countries, adjustment for baseline characteristics attenuated the associations. In Israel, there was no change in willingness to vaccinate with increasing vaccination rates and confidence intervals were centered closely around the null (OR = 1.03, 95% CI = 0.95–1.12). When using rate of double vaccine dose, results showed null effect in Israel (OR = 1.00, 95% CI = 0.99–1.02) and were similar but attenuated in the United States compared to single dose (OR = 1.07, 95% CI = 0.99, 1.16).

Table 2.

Odds ratios for willing to vaccinate for a 5% increase in population vaccination rate by country and odds ratios based on multivariable model including age, who completed the survey and vaccination status (up-to-date or not based on schedule in the country)

| Country | OR (95% CI)* | p value | Adjusted OR (95% CI)** | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single dose | ||||

| Canada | 0.82 (0.63, 1.07) | .15 | 0.96 (0.91, 1.01) | .12 |

| Israel | 1.03 (0.95, 1.12) | .47 | 1.01 (0.99, 1.02) | .49 |

| United States | 1.24 (0.99, 1.56) | .07 | 1.04 (1.00, 1.09) | .08 |

| Two doses | ||||

| Canada *** | - | - | - | - |

| Israel | 1.00 (0.99, 1.02) | .75 | 1.00 (0.99, 1.02) | .66 |

| United States | 1.07 (0.99, 1.16) | .09 | 1.07 (0.99, 1.15) | .11 |

*Estimated from model including week and vaccinate rate. Odds ratios are per 5% increase in population rate of vaccine.

**Further adjusted for age, who completed the survey and child vaccination status (up-to-date schedule vs not up-to-date).

***Could not be computed due to small cell size.

Figure 3 provides willingness to vaccinate amongst the study population as a function of first dose population percentage. Trends were similar to the odds ratios above. In Canada (total first dose given to <25% by end of study period), the estimated willingness declined over time from above to below 50%, in Israel (>60% received first dose) the estimated trend was almost unchanged in regards to plan to vaccinate children (~50%) and in the United States (30+% given first dose) estimated willingness increased from near 50% to 75%.

Figure 3.

Trend of parental willingness to vaccinate rate and population vaccinated with one dose of COVID-19 vaccine in each country.

Figure 4 represents simulated anticipated rate of parental willingness to vaccinate children under 12 years against COVID-19 if trend continued to 100% vaccination of adults in each country.

Figure 4.

Simulated anticipated rate of parental willingness to vaccinate children under 12 years against COVID-19 if trend continued to 100% vaccination of adults in population in each country. Shaded area is the confidence interval for the estimate.

Discussion

Vaccinating children against COVID-19 is critical as a public health strategy in order to reach herd immunity and prevent illness among children and adults.9 To our knowledge, this is the first study to identify correlation between willingness to vaccinate children under 12 years of age against COVID-19 in the future, and the country’s state of vaccination of the entire adult population (first and second dose). We found negative correlation in Canada, positive correlation in the United States and almost no correlation in Israel.

Vaccine safety is of paramount importance to individuals. Among a convenience sample in the United States, decrease in the incidence of major adverse effects of a hypothetical COVID-19 vaccine (before it was available) from 1/10,000 to 1/1,000,000 was associated with a higher probability of choosing a vaccine.10

When vaccine safety and efficacy scenarios were offered to a representative sample of the US population, vaccine acceptance improved when the efficacy of the vaccine was more than 70% and willingness reduced when the probability of serious adverse reactions was 1/100,000 (but not when it was 1/million or 1/100 million).11

We hypothesized that since safety is an imperative factor for both adult vaccine considerations as well as parental decision making about their children’s health, the implementation of a new vaccine program with a good safety profile as portrayed in the media, will increase confidence in parents’ decision to administer the same vaccine to their children. Our hypothesis suggested that the faster and more inclusive the country’s vaccine implementation, the higher the willingness trend of parents in that country.

In Israel, vaccinating the entire population was swift and effective, for both the first and second doses, with 60% of the population vaccinated in 4 months. Parents’ initial increasing willingness to vaccinate their children decreased once a large portion of the population was vaccinated.

There is some evidence that cultural dimensions, including social group-norms, may be different in individualistic versus collectivistic cultures and that given equal opportunity and access, some countries are more likely to be vaccinated compared to others.12 The phenomenon of Free-riding vaccines, where communities may feel that when a sufficiently effective vaccine is available, individuals may want others to get vaccinated to reach herd immunity, while not risking taking the vaccine themselves.13 It is possible that initial impression of quick vaccination progress in Israel helped parents feel more secured in administering their children a vaccine later. Then, when a certain threshold was reached, and rate of COVID-19 new cases declined, parents may have felt herd immunity provided sufficient protection and their children do not need to get vaccinated. Furthermore, after our study was completed an outbreak at two schools, attributed to the more infectious Delta variant, which resulted according to media in enhanced willingness to vaccinate adolescents.14 Public health authorities must stay vigilant and follow developments of the evolving pandemic, to ensure parental attitudes are followed closely. Another consideration that may have affected public opinion in Israel were the increasing pockets of unvaccinated groups around the same time as decline was noted among willingness to vaccinate in our study.15

In the United States, where parents witnessed a steady increase in rate of vaccination in the population, public opinion may have gathered momentum over the study’s four months and parents’ confidence increased, to a level they felt more willing to have their children under 12 years receive a future vaccine. In the United States, a third of parents did not plan to vaccinate their children in April 202116,17 and a report by a polling company in May 2021 found many parents desire to vaccinate their children after waiting several months.17

In Canada, vaccinating the population started later and was significantly slower than the other two countries, and public health decision was to first administer only one dose to the majority of the population, resulting in delayed administration of a second dose. Parents may have felt a lack of confidence in the vaccine program, resulting in a decline in willingness to vaccinate their young children as implied by the results. Slow vaccination rate of the general population may have prevented parents in Canada from feeling the vaccination program was safe and effective, further limiting their confidence in vaccinating their children. Furthermore, in March 2021 concerns over possible thromboses after immunization with the AstraZeneca vaccine,18 used only in Canada, appeared in the media and may have also affected confidence of parents.

Vaccine hesitancy has been a barrier to implementation of vaccine programs worldwide19 and more than 70 factors have been identified as affecting parental decision-making to have children vaccinated.20 This has also affected acceptance of COVID-19 available vaccines21 and doubts about the safety of the COVID-19 vaccine22,23 have contribute to hesitancy. Views of COVID-19 as a mild illness in children may contributed during the study period to hesitancy in planning to vaccinate children.

Vaccine-uptake strategies that focus solely on providing facts to parents are unsuccessful24 and a Cochrane review of face-to-face educational programs about vaccine safety found they were ineffective at changing parental attitudes about vaccines.25

The study has several limitations. First, the sample size for this secondary analysis is small and does not represent the population in the three countries, or those visiting participating EDs. This also led to increased uncertainty in predicted trends. Many factors that may affected willingness to vaccinate children were not captured in this survey, and despite adjustment for a few key baseline factors, evaluation of parental attitudes in this complex and ever-changing pandemic was limited. Also, trends may have changed once greater share of the population was vaccinated, and public health agencies should consider the findings in this study in view with country specific considerations. Finally, about 90% of children had up to date immunization, which may be higher than rates in other countries, and may represent a population with propensity to immunize their children.

Conclusions

A robust population-based vaccination program as in Israel and to a lesser degree in the US led to increasing willingness by parents to vaccinate their children younger than 12 years against COVID-19. In Canada, with slower rate of vaccination of the adult population, parents were found to be less willing to consider vaccinating their children. When considering future booster COVID-19 vaccines, Governments and public health leaders should consider the implications of vaccination program pace on parental decisions to vaccinate their young children. Public health in those countries, and likely others, need to continue and understand determinants of vaccine hesitancy among parents by creating a strong community-based qualitative and qualitative surveying of parents of young children. Vaccination campaigns need to be flexible and address parental concerns and attitudes, and take into account the pace and mobilization of vaccine programs in the country.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to Ms. Marissa Gibbard from BC Children’s Research Institute for her ongoing effort in support of this international study.

Funding Statement

The author(s) reported there is no funding associated with the work featured in this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data statement

The data will not be shared nor disseminated to study participants/patient organizations.

References

- 1.Oliver SE, Gargano JW, Marin M.. The advisory committee on immunization practices’ interim recommendation for use of moderna COVID-19 vaccine - United States, December 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;69:1653–56. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm695152e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Regev-Yochay G, Amit S, Bergwerk M, Lipsitch M, Leshem E, Kahn R, Lustig Y, Cohen C, Doolman R, Ziv A, et al. Decreased infectivity following BNT162b2 vaccination: a prospective cohort study in Israel. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2021;7:100150. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dagan N, Barda N, Kepten E, Miron O, Perchik S, Katz MA, Hernán MA, Lipsitch M, Reis B, Balicer RD.. BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine in a nationwide mass vaccination setting. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(15):1412–23. Epub 2021 Feb 24. PMID: 33626250. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2101765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) . Vaccines and related biological products advisory committee meeting. FDA Briefing Document Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine; 2020. [accessed 2021 Sep 28]. https://www.fda.gov/media/144434/download.

- 5.Hughes MM, Wang A, Grossman MK, Pun E, Whiteman A, Deng L, Hallisey E, Sharpe JD, Ussery EN, Stokley S, et al. County-level COVID-19 vaccination coverage and social vulnerability - United States, December 14, 2020-March 1, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(12):431–36. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7012e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ismail SJ, Zhao L, Tunis MC, Deeks SL, Quach C; National Advisory Committee on Immunization . Key populations for early COVID-19 immunization: preliminary guidance for policy. CMAJ. 2020;192(48):E1620–32. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.202353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Government of Canada . COVID-19 immunization: federal, provincial and territorial statement of common principles. Ottawa (ON): Government of Canada; 2020. [accessed 2021 Sep 26]. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/2019-novel-coronavirus-infection/canadas-reponse/covid-19-immunization-federal-provincial-territorial-statement-common-principles.html. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldman RD, Yan TD, Seiler M, Parra Cotanda C, Brown JC, Klein EJ, Hoeffe J, Gelernter R, Hall JE, Davis AL, et al. International COVID-19 Parental Attitude Study (COVIPAS) group. Caregiver willingness to vaccinate their children against COVID-19: cross sectional survey. Vaccine. 2020;38(48):7668–73. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.09.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paul LA, Daneman N, Schwartz KL, Science M, Brown KA, Whelan M, Chan E, Buchan SA. Association of age and pediatric household transmission of SARS-CoV-2 infection. JAMA Pediatr. 2021. PMID: 34398179. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.2770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kreps S, Prasad S, Brownstein JS, Hswen Y, Garibaldi BT, Zhang B, Kriner DL. Factors associated with US adults’ likelihood of accepting COVID-19 vaccination. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(10):e2025594. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.25594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaplan RM, Milstein A. Influence of a COVID-19 vaccine’s effectiveness and safety profile on vaccination acceptance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118(10):e2021726118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2021726118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thomson A, Watson M. Listen, understand, engage. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(138):138ed6. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agranov M, Elliott M, Ortoleva P. The importance of social norms against strategic effects: the case of Covid-19 vaccine uptake. Econ Lett. 2021;206:109979. doi: 10.1016/j.econlet.2021.109979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reuters . COVID-19 cases spur parents to vaccinate kids. 2021. Jun 22 [accessed 2021 Sep 26]. https://www.straitstimes.com/world/middle-east/school-covid-19-cases-spur-israeli-parents-to-vaccinate-kidsSchool.

- 15.Lyski ZL, Brunton AE, Strnad MI, Sullivan PE, Siegel SAR, Tafesse FG, Slifka MK, Messer WB. SARS-CoV-2 specific memory B-cells from individuals with diverse disease severities recognize SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern. medRxiv [Preprint]. 2021. Jun 3;2021(5):28.21258025. doi: 10.1101/2021.05.28.21258025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Calarco JM, Anderson EM. “I’m not gonna put that on my kids”: gendered opposition to new public health initiatives. 2021. Mar 18 [accessed 2021 Sep 26]. 10.31235/osf.io/tv8zw. [DOI]

- 17.Invisibly . Parents are cautious to vaccinate their kids against COVID. 2021. May 10 [accessed 2021 Sep 26]. https://realtimeresearch.invisibly.com/insights/pandemic-new-normal-2.0.

- 18.Huner PR. Thrombosis after covid-19 vaccination. BMJ. 2021;373:n958. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.MacDonald NE. Vaccine hesitancy: definition, scope and determinants. SAGE working group on vaccine hesitancy. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4161–64. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McGregor S, Goldman RD. Determinants of parental vaccine hesitancy. Can Fam Physician. 2021;67:339–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Detoc M, Bruel S, Frappe P, Tardy B, Botelho-Nevers E, Gagneux-Brunon A. Intention to participate in a COVID-19 vaccine clinical trial and to get vaccinated against COVID-19 in France during the pandemic. Vaccine. 2020;38(45):7002–06. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.09.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dror AA, Eisenbach N, Taiber S, Morozov NG, Mizrachi M, Zigron A, Srouji S, Sela E. Vaccine hesitancy: the next challenge in the fight against COVID-19. Eur J Epidemiol. 2020;35(8):775–79. Epub 2020 Aug 12. PMID: 32785815. doi: 10.1007/s10654-020-00671-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Griffith J, Marani H, Monkman H. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Canada: content analysis of tweets using the theoretical domains framework. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(4):e26874. doi: 10.2196/26874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Damnjanović K, Graeber J, Ilić S, Lam WY, Lep Ž, Morales S, Pulkkinen T, Vingerhoets L. Parental decision-making on childhood vaccination. Front Psychol. 2018;9:735. PMID: 29951010. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaufman J, Ryan R, Walsh L, Horey D, Leask J, Robinson P, Hill S. Face-to-face interventions for informing or educating parents about early childhood vaccination. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;5(5):CD010038. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010038.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]