ABSTRACT

The purpose of this study was to identify the main barriers to vaccine acceptance among medical students in Kazakhstan and to develop the COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Scale (COV-VHS). A cross-sectional study was carried out among students at Astana Medical University (N = 888, Kazakhstan) in March 2021. Only 2% of the participants were currently vaccinated, and 22.4% showed the potential for COVID-19 vaccine acceptance. The following barriers were the most important in COVID-19 vaccine acceptance: concern about possible side effects of vaccination (73%), absence of sufficient evidence on the effectiveness and safety (57%) and quality (42%), the belief that the immune system will cope with COVID-19 even without vaccination (38%), and lack of trust in the effectiveness of vaccination against COVID-19 (33%). Moreover, this study identified the following factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine acceptance: contextual influences (e.g., communication and media environment, socio-demographic factors, vaccination policies, and perception of the pharmaceutical industry), individual and group influences (e.g., personal experience with vaccination, attitudes about health and prevention, trust in the health system and providers, perceived risk), and specific issues on COVID-19 vaccine/vaccination (e.g., choice of vaccine can reduce vaccine hesitancy by 30%). A developed 12-item 6-factor model of COV-VHS showed good validity and reliability. In conclusion, there was a low-level potential for COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among medical students in Kazakhstan. Thus, an effective vaccination education and policy are needed to combat the COVID-19 pandemic.

KEYWORDS: COVID-19, pandemic, vaccination, vaccine hesitancy, Vaccine Hesitancy Scale, validation, medical students

1. Introduction

The outbreak of a novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, turned up in December 2019, was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) on March 11, 2020. Considering the rapid spread and high mortality of COVID-19, an effective vaccination program is urgently needed to control this pandemic.1 And the faster the vaccine is deployed, the faster the pandemic can be controlled.2

On February 1, 2021, Kazakhstan began vaccination against COVID-19 using the Gam-COVID-Vac (“Sputnik V”) viral vector vaccine produced in Russia. On February 13, permission was obtained to use the Gam-COVID-Vac produced in Karaganda (Kazakhstan). From the second quarter of 2021, it was planned to vaccinate with QazCovid-In vaccine (Kazakhstan),3 which at the time of current article writing (April 1, 2021) was in phase 3 of clinical trials. The government of Kazakhstan has planned that from February 1, 2021, medical workers (approximately 100 thousand people) will be vaccinated; and at the second stage (from March 1), about 150 thousand people will be vaccinated, including teachers of schools and universities. From April 1, it was planned that the third stage of vaccination (about 600 thousand people) among students and people with chronic diseases would be started. And then (stage 4), the rest of the population was planned to be vaccinated (about 6 million people).4,5 However, as of March 5, 2021, about 15,000 people received the Gam-COVID-Vac vaccine and in 2 months (as of April 1, 2021), only 0.1% of the population received the COVID-19 vaccine.6 In this context, it is important to identify the main obstacles, in addition to the shortage of vaccines, to the adoption of the COVID-19 vaccine in anticipation of the planned vaccination among students.

Vaccination behavior of medical students has a number of significant implications. First, the early vaccination of students will allow them to resume the traditional format of education, when they can fully attend medical institutions to develop practical skills. Being vaccinated, students are less likely to be able to get infected from patients, or to be carriers of infection inside hospitals. Secondly, medical students are an integral part of the general population, and their vaccination will directly affect herd immunity. Thirdly, medical students, as future doctors and people with already some baggage of medical knowledge, can play the role of mentors for the general population on the issue of health protection. Besides, they may demonstrate model behavior in relation to vaccination against COVID-19.

Even before the pandemic, despite overwhelming evidence of the value of vaccines for disease prevention, vaccine hesitancy was growing. In 2014, the WHO Strategic Advisory Group on Experts (SAGE) on Immunization defined vaccine hesitancy as “a delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccination despite availability of vaccination services.” Moreover, the hesitation of vaccination depends on many factors.7 A review of the literature showed the following reasons for refusing vaccination against COVID-19: conspiracy beliefs (e.g., COVID-19 vaccines are intended to inject microchips),8,9 structural (e.g., vaccine availability) and attitudinal barriers,10 mistrust of the vaccine’s benefits and concerns about future unforeseen side effects, knowledge about vaccination,11,12 and availability of information.13 A review by Dubé et al.14 additionally pointed to the following factors of vaccine hesitancy: subjective norms, religion, past experiences, communication, and media. A study conducted among US adults demonstrated that vaccine efficacy, adverse effects, protection duration, and national origin of vaccine were associated with preferences for choosing a hypothetical COVID-19 vaccine.15 One way to study human behavior in relation to vaccination is to use the Vaccine Hesitancy Scales. Such measurements can be used widely to understand the correlates of vaccine hesitancy, and the association of vaccine hesitancy with different personal, environmental and political factors.16 However, there are no data on adapted and validated scales capable of assessing vaccine hesitancy in Kazakhstan. Despite the fact that previously there was a study on the parental hesitancy of children vaccination.17

According to Harrison and Wu18, in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic, the concept of public health must be broader than the delivery of the vaccine technology itself. Based on the above, the purpose of this study was to identify the main barriers to vaccine acceptance among medical students in Kazakhstan and to develop and validate the COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Scale (COV-VHS).

2. Method

2.1. Participants and study design

An online questionnaire-based cross-sectional study was conducted among bachelor medical students at Astana Medical University, Kazakhstan. The study was conducted in March 2021. An online survey (created in 1ka platform) was sent to students using the university information portal “Sirius” and various social networks. All medical students able to take online surveys had the opportunity to take the survey, having agreed in advance to participate.

2.2. Measures

Socio-demographic and personal characteristics included gender, age, year of study, diagnosis with COVID-19, past history of vaccination according to the national vaccination calendar of Kazakhstan and against influenza. Each item of the COV-VHS had 5 possible answers and ratings: “Strongly disagree” (1), “Disagree” (2), “Undecided” (3), “Agree” (4), and “Strongly agree” (5). To calculate the overall result, the answers received for each item must be summarized. The higher the value obtained, the higher the level of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy.

Vaccination hesitancy was assessed based on the question “Are you ready to receive the COVID-19 vaccine?” There were 4 possible answers to this question: “I am already vaccinated,” “I am ready to consent to vaccination,” “I am not ready to consent to vaccination, as I have medical and social contraindications,” and “I am not ready to consent to vaccination for other reasons.” Respondents who answered that they were not ready to consent to vaccination due to medical withdrawals were excluded from further analysis. At the same time, the respondents who indicated “I am not ready to consent to vaccination for other reasons” were allocated to the COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy group.

2.3. Scale development and validation

According to Wallace et al.19, we followed a modified 6-step process to develop the validated COV-VHS. The item generation on the new COV-VHS scale was carried out by a deductive method, and the questions were created based on the literature review.8–15 Initially, the pool of elements consisted of 14 items. The content validity was assessed by experts from the fields of immunization, infectious diseases, epidemiology, and public health. The points of the scale for relevance, importance, and comprehensibility were rated by 6 experts. According to the recommendations of the experts, the item “Have you previously been vaccinated according to the vaccination schedule?” was excluded from the scale, but remained as an additional question in the general questionnaire. The scale development consisted of item reduction and extraction of factors using exploratory factor analysis (EFA). EFA was carried out to determine the number of factors with cutoff scores of item/factor loading >0.3.20 The scale evaluation consisted of a test of dimensionality, analysis of reliability and validity. Construct validity was established by the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) technique, with the Bartlett test of sphericity and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure (acceptable at RMSEA (<0.08); CFI and TLI (>0.9)).21 Scale reliability was assessed using the internal consistency coefficient Cronbach alpha with a cutoff value ≥0.7.22 Criterion validity was assessed using the ROC analysis with cutoff points for the area under the curve (AUC) varying between 0.5 and 1.0.23

2.4. Statistical analysis

Data analysis was conducted using Microsoft Excel 2007, SPSS version 20.0, and Jamovi version 1.2.17. Descriptive statistics were performed with the calculation of the mean (M) and standard deviation (SD) for quantitative variables; percentages were calculated for qualitative variables. The chi-squared test was used to assess the differences between variables. A statistically significant difference was accepted at a P value of less than 5%.

Media content analysis of information about the COVID-19 vaccine was performed to compare the focus of the information content and the reasons for vaccine hesitancy.

2.5. Ethical consideration

The study was approved by the Local Ethics Committee of Astana Medical University (extract from protocol No. 6 of April 6, 2020).

3. Results

In March 2021, a total of 999 students completed the survey. The average age of the participants was 19.9 (SD = 1.97). Of them, 18 participants (1.8%) were currently vaccinated, 15 of whom worked. Only 19.9% of the respondents were willing to consent to the COVID-19 vaccination, 67.2% of the students did not agree to be vaccinated, and 11.1% had medical and social contraindications. Since 111 respondents (89 women and 22 men) had medical contraindications, these data were removed from further analysis. Thus, the data of 888 respondents were used. Table 1 presents baseline socio-demographic and personal data of the participants.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population (N = 888)

| Variables | N (%) | COVID-19 vaccination status |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccinated | Agree to be vaccinated | Disagree to be vaccinated | ||

| Gender, χ2 = 21.2, p < .001 | ||||

| Male | 209 (23.5) | 11 (5.3) | 59 (28.2) | 139 (66.5) |

| Female | 679 (76.5) | 7 (1.0) | 140 (20.6) | 532 (78.4) |

| Year of study, χ2 = 27.8, p < .001 | ||||

| 1-year | 161 (18.1) | 2 (1.2) | 36 (22.4) | 123 (76.4) |

| 2-year | 186 (21.0) | 1 (0.5) | 36 (19.4) | 149 (80.1) |

| 3-year | 295 (33.2) | 5 (1.7) | 50 (16.9) | 240 (81.4) |

| 4-year | 184 (20.7) | 8 (4.4) | 60 (32.6) | 116 (63.0) |

| 5-year | 62 (7.0) | 2 (3.2) | 17 (27.4) | 43 (69.4) |

| Total | 888 | 18 (2.0) | 199 (22.4) | 671 (75.6) |

3.1. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and socio-demographic and personal characteristics

Male students were more likely to be vaccinated and willing to consent to vaccination against COVID-19 (χ2 = 12.1, p < .001). The largest number of the students who were not ready to receive vaccination was observed among students of study years 1–3.

The rate of refusal to vaccinate against COVID-19 was higher among the respondents who were not or were partially previously vaccinated according to the national vaccination schedule of the Republic of Kazakhstan (RK, 79.5% and 76.5, respectively), compared with those who were fully vaccinated according to the national vaccination schedule (71.5%), p < .05. The refusal rate was also higher among the respondents who had not previously been vaccinated against influenza (75.5%) compared with those who were vaccinated (70.7%), p < .001.

Potential vaccine acceptance rates were higher among those with a history of positive PCR analysis for COVID-19 (44.4% vs 22.9%, p < .001), IgM/IgG analysis (48.0% vs 23.8%, p < .05), and COVID-19 clinical manifestation (35.4% vs 22.8%, p < .05); meanwhile, they were lower among not infected participants (20.0% vs 28.9%, p < .05).

Results of the respondents’ answers to the question “What vaccine(s) against COVID-19 would you prefer to receive?” are presented in Table 2. Of the 671 respondents who had previously refused vaccination, 207 (30.8%) were ready to take one of these vaccines in case of their own choice.

Table 2.

Preference in the choice of vaccines against COVID-19 and the proportion of vaccine acceptance compared to those who previously refused vaccination

| Vaccines | n (%) | Previously COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy before choosing a vaccine type (N = 671) n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sputnik V (Russia) | 202 (22.7) | 89 (13.3) |

| Sputnik V (Kazakhstan) | 100 (12.5) | 39 (5.8) |

| JNJ-78436735 (Johnson & Johnson, Netherlands, USA) | 68 (7.7) | 40 (6.0) |

| QazCovid-In (Kazakhstan) | 66 (7.4) | 27 (4.0) |

| AstraZeneca (Covishield, UK) | 66 (7.4) | 38 (5.7) |

| Moderna (Moderna, BARDA, NIAID, USA) | 61 (6.9) | 35 (5.2) |

| Comirnaty (Pfizer, BioNTech; Fosun Pharma) | 49 (5.5) | 24 (3.6) |

| CoronaVac (Sinovac, China) | 31 (3.5) | 19 (2.8) |

| BBIBP-CorV (China) | 20 (2.3) | 10 (1.5) |

| Convidicea (Ad5-nCoV), CanSino Biologics (China) | 14 (1.6) | 6 (0.9) |

| EpiVacCorona (Russia, Turkmenistan) | 10 (1.1) | 6 (0.9) |

| Covaxin (Bharat Biotech, ICMR, India) | 10 (1.1) | 7 (1.0) |

| Total | 697 | 207 (30.8)* |

*Since respondents had the option to choose several vaccines, this number summarizes the total number of respondents who indicated at least one type of vaccine.

Regarding COVID-19 vaccination, the respondents trusted the following sources: governance (53.8%), WHO (39.6%), expert opinion (25.5%), opinion of family members (16.1%), and nonexpert opinions (6.8%). The respondents who indicated that they trusted government sources when deciding to vaccinate were more willing to receive the COVID-19 vaccine (28.0% vs 20.2%, p < .05). At the same time, trust in the opinions of close relatives was associated with the refusal to vaccinate (88.8% vs 73.0%, p < .001).

3.2. Validity of the COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Scale

Based on a literature review and content validity analysis, this study identified 13 barriers to vaccine acceptance, which is presented in Table 3. Item “I do not know where and how to get the COVID-19 vaccine” was removed because it had a low impact (<0.3) on the EFA. The 6-factor model of the COV-VHS included 12 items presented in Table 4. The Bartlett sphericity test result was significant (p < .001), and the KMO measure of sampling adequacy exceeded 0.842.

Table 3.

Participants’ barriers associated with COVID-19 vaccine acceptance (n = 888)

| Barriers associated with COVID-19 vaccine acceptance | M (SD) | Vaccine refuses (N = 671) |

|---|---|---|

| I am concerned about the possible side effects of the COVID-19 vaccine | 3.82 (1.08) | 489 (72.9%) |

| I believe there is not enough scientific and clinical evidence on the effectiveness and safety of the COVID-19 vaccine | 3.52 (1.12) | 381 (56.8%) |

| I have not received sufficient information on the quality and effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccine | 3.19 (1.19) | 282 (42.0%) |

| Vaccination against COVID-19 is not required because I am confident that my immune system will cope with this infection. | 3.05 (1.10) | 259 (38.6%) |

| I do not consider vaccination against COVID-19 an effective way to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic | 3.06 (1.10) | 224 (33.4%) |

| I refuse vaccination as the environment in which I grew up (my family, guardians) is against vaccination in general, and in particular against the COVID-19 vaccine | 2.51 (1.20) | 178 (26.5%) |

| I am concerned that the COVID-19 vaccination is a purely commercial exercise designed to increase the profits of pharmaceutical companies | 2.75 (1.08) | 155 (23.1%) |

| In general, I do not consider vaccination to be an effective way to fight infectious diseases | 2.73 (1.09) | 155 (23.1%) |

| Vaccination against COVID-19 is not required if I have had COVID-19 | 2.84 (0.99) | 141 (21.0%) |

| I do not believe that COVID-19 is a dangerous infection for me | 2.57 (1.07) | 113 (16.8%) |

| I do not know where and how to get the COVID-19 vaccine | 2.55 (1.08) | 96 (14.3%) |

| I am concerned that the developed COVID-19 vaccine contains chips to control my privacy | 2.31 (1.09) | 82 (12.2%) |

| I refuse vaccinations for religious reasons | 2.07 (0.98) | 49 (7.3%) |

Table 4.

Factor loadings for development of a 6-factor scale version of the COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Scale (N = 888)

| Item | Standardized factor loading |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Efficacy and Safety (EE) | Risk Perceptions (RP) | Conspiracy (C) | Knowledge and information (KI) | Trust (T) | Social norm (SN) | |

| 1. I am concerned about the possible side effects of the COVID-19 vaccine | 0.569 | |||||

| 2. I do not consider vaccination against COVID-19 an effective way to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic | 0.446 | |||||

| 3. Vaccination against COVID-19 is not required if I have had COVID-19 | 0.618 | |||||

| 4. Vaccination against COVID-19 is not required because I am confident that my immune system will cope with this infection | 0.767 | |||||

| 5. I do not believe that COVID-19 is a dangerous infection for me | 0.593 | |||||

| 6. I am concerned that the COVID-19 vaccination is a purely commercial exercise designed to increase the profits of pharmaceutical companies | 0.765 | |||||

| 7. I am concerned that the developed COVID-19 vaccine contains chips to control my privacy | 0.698 | |||||

| 8. I have not received sufficient information on the quality and effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccine | 0.781 | |||||

| 9. I believe there is not enough scientific and clinical evidence on the effectiveness and safety of the COVID-19 vaccine | 0.698 | |||||

| 10. In general, I do not consider vaccination to be an effective way to fight infectious diseases. | 0.547 | |||||

| 11. I refuse vaccinations for religious reasons | 0.733 | |||||

| 12. I refuse vaccination as the environment in which I grew up (my family, guardians) is against vaccination in general, and in particular against the COVID-19 vaccine | 0.777 | |||||

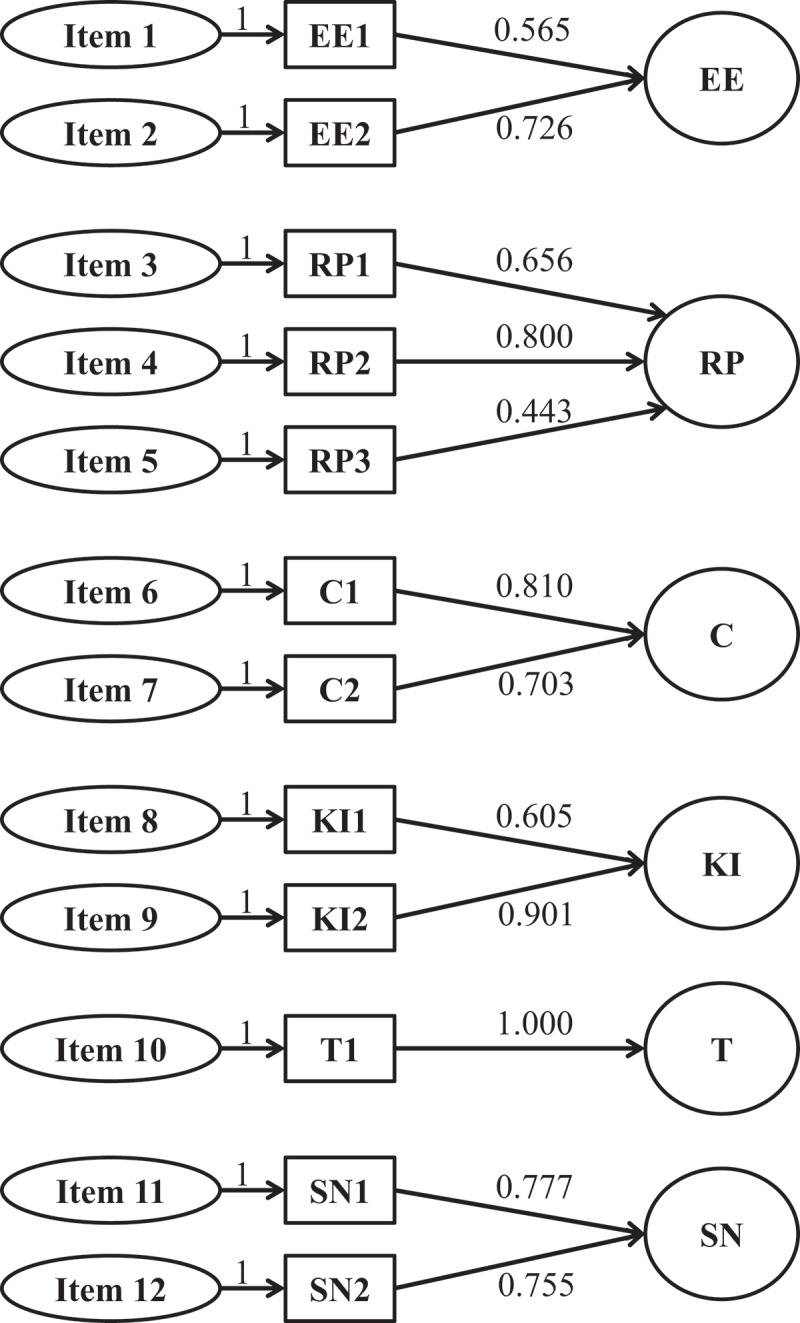

According to the CFA analysis, the model fit of the 6-factor COV-VHS model was confirmed by the indices: χ2/df = 2.819; RMSEA = 0.0452 (95%CI 0.030–0.0611), CFI = 0.902, TLI = 0.966; with cumulative variance of 55.4%. The total Cronbach alpha for the COV-VHS was 0.834. Figure 1 shows the factor model. Standardized covariances of 6 factors were in the range of 0.371–0.776.

Figure 1.

Confirmatory factor analysis of the COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Scale (COV-VHS) [χ2/df = 2.819; RMSEA = 0.0452, CFI = 0.902, TLI = 0.966].

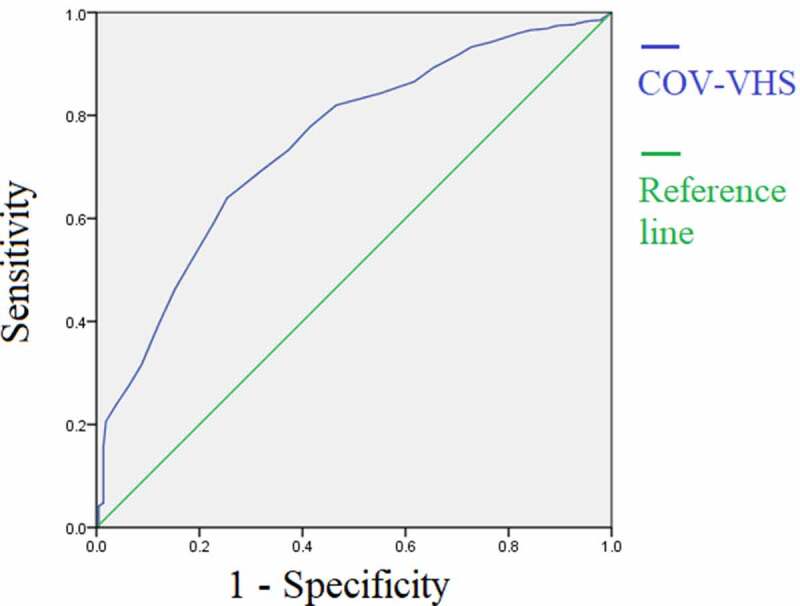

The criterion validity of COV-VHS was measured by the number of respondents who answered “I am not ready to consent to vaccination.” This resulted in an AUC of 0.744 (0.708–0.781) for COV-VHS, p < .001 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) of the COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Scale (COV-VHS).

The average value of the COV-VHS was 34.4 ± 7.79 (in a range of 12–60). Female students (35.0 ± 7.35) showed a higher level of the COV-VHS compared with male students (32.5 ± 8.82). The fourth-year medical students (33.2 ± 7.50) had a lower level of the COV-VHS compared with the second-year students (35.4 ± 6.97), p < .05.

3.3. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and social media

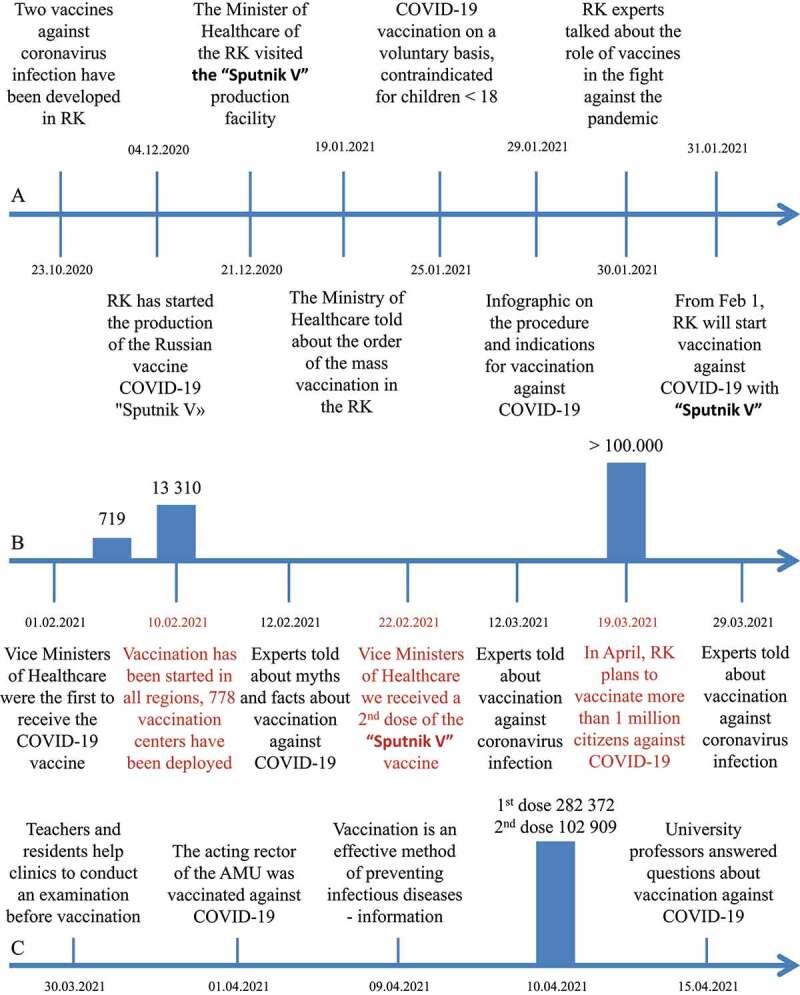

Media content analysis of information provided by the Ministry of Healthcare of the RK and Astana Medical University about the vaccination against COVID-19 is presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Media content analysis of information about the COVID-19 vaccine in the Republic of Kazakhstan (RK). (a) major information from the Ministry of Healthcare of the RK before the start of COVID-19 vaccination (31.01.2021); (b) major information from the Ministry of Healthcare of the RK for the period from February 1, 2021, to April 1, 2021; (c) information from Astana Medical University.

4. Discussion

Since healthcare workers play a key role in vaccination, initial training for medical students should be aimed at shaping their attitudes toward this issue.24 According to Sallam, low rates of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance could pose a major challenge in global efforts to combat the COVID-19 pandemic, and researches are needed to explore barriers to vaccination in Central Asian countries.25 In this study, we identified the main barriers to COVID-19 vaccination and validated a COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Scale (COV-VHS).

4.1. Barriers of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance

Among 888 follow-up participants, only 2% were already vaccinated, 22.4% were ready to receive the COVID-19 vaccine, while more than three quarters indicated that they did not agree to be vaccinated. Given such a high percentage of refusal to vaccinate, the situation for further organization of the educational process at the university is aggravated and is also associated with the disappointing forecasts of the epidemiological situation in Kazakhstan. However, such a high percentage of refusals to vaccinate are not typical not only of student youth, but in general of RK. Thus, according to a survey conducted in August 2020–February 2021 by Gallup, only 25% of Kazakhstanis were ready to give potential consent to vaccination against COVID-19.26 However, a study provided by Issanov et al. showed that COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy was observed in 36% of study population.27 The reasons for such differences may be due to the different time of data collection and the sample under study.

The following barriers are the most important in COVID-19 vaccine refusal: concern about possible side effects of vaccination (73%), absence of sufficient scientific and clinical evidence on the effectiveness and safety of the COVID-19 vaccine (57%), absence of sufficient information on the quality and effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccine (42%), the belief that the immune system will cope with the COVID-19 even without vaccination (38%), and lack of trust in the effectiveness of vaccination in the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic (33%). In agreement with, a study conducted in China has revealed that the perception of vaccine effectiveness showed the highest significant odds of a definite intention to take the COVID-19 vaccine.12 In Portugal, dissatisfaction with the information received has been associated with vaccine refusal and delay.28

In this study more than half of the respondents indicated that there were no reliable data indicating the effectiveness and safety of the vaccine. However, preliminary results on the efficacy (91.6%) and safety of the “Sputnik V” vaccine were published before by Logunov et al.29 Moreover, the effectiveness of the QazCovid-In vaccine according to the results of the second stage of clinical trials has shown a result of 96%.30 A study conducted among Polish medical community has demonstrated, that the safety and efficacy of vaccination against COVID-19 would persuade more than 85% of hesitant people and those who would refuse to be vaccinated.31 Also, the impact of the COVID-19 vaccine safety and the side effects on low acceptance rates has been found among Palestinian nurses.32 However, in a large cross-sectional study of adults in Latin America and the Caribbean, although the prevalence of fear of vaccine side effects is 81.2%, 80% of the population intends to receive the COVID-19 vaccine.33

Most vaccine refusal rates have been observed among women. One study found that women were associated with a lower probability of vaccine intention and a higher probability of fear of its adverse effects.33 Meta-analytical calculations provided by Zintel et al.34 showed that men who resort to pharmaceutical methods are 1.41 times more willing to receive the COVID-19 vaccine. Khubchandani et al.35 have also indicated the role of gender in COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy.

Moreover, a history of COVID-19 has been associated with potential vaccine intake. This may be due to the individual’s perceived risk of COVID-19. However, some studies conducted both in the general population and among health care workers have not found associations between the history of COVID-19 and vaccine acceptance.36,37 In this case, it is necessary to take into account the severity of the past COVID-19 disease, other life/health responsibilities and possible medical histories of close relatives and friends. Considering the medical background of the study participants, the diagnosis of COVID-19 was more likely associated with concerns not only for their own health, but also for the health of other people. Also, one of the factors associated with making a decision about vaccination is influences arising from personal perception, e.g., past experience with vaccination.38 In the current study, the past behavior with vaccination relates to the adoption of the COVID-19 vaccine. A history of seasonal influenza vaccine withdrawal has also been linked to a COVID-19 vaccine refusal. However, a study conducted among healthcare workers in Saudi Arabia has not found such associations.39

Schwarzinger et al.40 have concluded that COVID-19 vaccine acceptance depends on the characteristics of new vaccines and the national vaccination strategy. A multinational study, conducted in June 2020, demonstrated that, the highest potential acceptance rate of a COVID-19 vaccine was in China (88.6%), and the lowest in Russia (54.9%).41 Of note, the “Sputnik V” vaccine was the preferred choice of respondents. As indicated in Table 2, different vaccines have varying degrees of preference among respondents. In our opinion, the company and the country of the manufacturer play an important role in the choice of the vaccine, and also, if we take into account the medical education of the respondents, then the manufacturing mechanism42 is a vector or inactivated vaccine. According to the result of this study, whichever choice respondents make, having multiple vaccine choices can reduce vaccination hesitancy by about 30%.

In our study the highest COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy was among pre-clinical medical students. This can be explained by the fact that although students begin to study microbiology, immunology, epidemiology, and public health in the second and third year of study according to the educational program in the RK, the clinical and epidemiological understanding of the importance of vaccination comes only when they are included in active practical work in the health care system. For this reason, early inclusion of public health education programs in medical education is recommended. A similar problem is observed in the higher education system of European countries.43–45 A study conducted among US medical students highlights the need for a safety and efficacy curriculum development to drive the COVID-19 vaccination.46

Israel has become a world leader in rolling out the COVID-19 vaccination program,47,48 which allows the factors associated with high vaccine acceptance to be assessed and compared with those among Kazakhstani medical student population. Rosen, Waitzberg, & Israeli49 have identified 3 factors that have influenced an effective vaccination program in Israel. One group of factors consisted of non-health characteristics of Israel, such as: Israel’s small size, relatively young population, and relatively warm weather. Given this, in this study the average age of participants was 19 years. At the same time, among 18–24-year-old French citizens, only 19.8% have indicated outright refusal of COVID-19 vaccination.50 Other factors were associated with the organization of the health care system.49 However, ignorance of vaccination places was associated with only 14% of refusal to vaccinate among medical students in Kazakhstan.

SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy has indicated 3 determinants of vaccine hesitancy: (1) historic, socio-cultural, environmental, health system/institutional, economic or political factors; (2) individual and group influences; and (3) factors directly related to vaccine or vaccination.38 In terms of contextual influence, in current study religion and geographic barriers contributed the least to vaccine refusal. Moreover, the free availability of the vaccine in the RK was supposed to reduce the vaccination-specific issues of refusal. However, it is worth paying attention to environmental and institutional factors of the vaccination campaign, e.g., communication and media environment, and policies. Talukdar, Stojkovski, & Suarez50 have indicated that information technology plays a critical role in the importance of vaccination against COVID19 infection. Moreover, the Working Group on Readying Populations for COVID-19 Vaccine in the US has recommended informing the public about the benefits, risks, and supply of vaccination against COVID-19.51 The authors of this study analyzed the information on vaccination provided by the Ministry of Health of the RK. Thus, before the start of vaccination (January 31, 2021), most of the information was related to organizational work (vaccination procedure, indications, and contraindications), and before the start of the vaccination campaign itself, information was published on the role of the vaccine in the fight against the pandemic. After the start of vaccination in Kazakhstan, educational information about vaccination increased and information about the experience of vaccination of representatives of the Ministry of Healthcare appeared. Research from low- and middle-income countries such as RK indicates that communication focused on vaccine efficacy and safety can be effective in clearing remaining doubts about COVID-19 vaccination.52 Given that the vaccine acceptance was associated with trust in governance, an earlier start of educational information is recommended before starting a vaccination campaign.

We would also like to note that no educational courses or seminars regarding vaccination against COVID-19 at the university were held at the time of article writing. Astana Medical University began to publish information on vaccination among students only from the end of March 2021. A study conducted among French students highlighted the need to develop special educational messages for students about the seriousness of COVID-19, in particular the possible long-term negative health effects, and to address the problems associated with vaccine side effects in general by debunking misconceptions.53 Moreover, the importance of universities working with government and health authorities to increase acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine is highlighted in a study from Egypt.54

4.2. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Scale

In the current study the identified barriers made it possible to create a reliable and validated 12-item COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Scale (COV-VHS). This could be indicated by the following values: the Bartlett sphericity test result was significant (p < .001), KMO measured 0.842, RMSEA = 0.0452, CFI = 0.902, TLI = 0.966, the Cronbach alpha was equal to 0.834, and the AUC was 0.744 from the ROC analysis. EFA made it possible to identify a 6-factor structure of COV-VHS: (1) efficacy and safety (EE) included concerns about vaccine side effects and pandemic efficacy, (2) risk perceptions (RP) included perceptions that vaccination is not required for a reason of the previous recovery from COVID-19, the immune system will cope, and COVID-19 is not a dangerous infection, (3) conspiracy beliefs (C) included the opinion that vaccines contain chips and are created for commercial purposes only, (4) knowledge and information (KI) included items describing absence of information about COVID-19 vaccination, (5) trust (T) included general confidence in the effectiveness of vaccination, and (6) social norms (SN) related to religious beliefs and family attitudes toward vaccinations.

Akel and others have pointed out that most research on vaccine hesitancy has focused on parental attitudes toward vaccination of children. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of assessing adult vaccination hesitancy as more adult vaccines will be introduced in the future.55 Several scales are currently available to measure COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Freeman et al.’s developed 7-item Oxford COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Scale assesses behavior regarding COVID-19 vaccination;56 however, it requires additional questions to identify the reasons for refusing vaccination. Rodriguez et al. have adopted the Vaccine Hesitancy Scale for people with HIV with two factors consisting of “Lack of confidence” and “Risks.”57 In contrast to the above-mentioned scales, COV-VHS developed in the current study has a more extensive factor structure, which not only describes the behavior in relation to vaccination, but is aimed at identifying barriers that contribute to the refusal of COVID-19 vaccination. However, it is necessary that the COV-VHS be faced with a question about the respondent’s attitude toward COVID-19 vaccination.

Currently, there are several models describing behavior or defining barriers to vaccination; there are several different scales describing hesitancy or readiness to vaccinate. However, each vaccine, each vaccination campaign has its unique structures, which can be determined by: the target group of the study (among adults or parents), cultural characteristics, relevance/potential danger of a preventative disease, the political and social life of individuals, the activity of the media system and much more. Therefore, at the moment it is difficult to create a universal scale that would describe the human behavior to vaccinate and that can determine all possible factors and barriers. However, the expansion of knowledge through similar studies will allow in the future creating universal and more sensitive scales, the use of which would more accurately describe the attitude of people toward vaccination and would create the necessary policy for combating early with vaccine hesitancy.

4.3. Limitations

There were several limitations in the current study. First, data collection was carried out only among those students who agreed to participate in the study, and there was no randomization process. Second, the results are based on a cross-sectional study, and the identification of causal relationships is not possible. Third, the potential barriers to COVID-19 vaccination and the process of item generation, respectively, were based only on a literature review, while it is recommended to combine this process with focus group surveys/interviews. Fourthly, assessing the validity, exploratory factor analysis and confirmatory factor analysis were carried out on the same sample. Finally, the data were obtained among students only from one university, and generalization of the results to all medical students is not acceptable; moreover, the use of the COV-VHS scale among the general population requires additional studies.

5. Conclusions

We agree with Biswas et al., that healthcare workers play a key role in modeling preventive behavior and vaccination assistance in the population,58 and we believe that medical students are also important in this role as learners today and health care providers in the future. Thus, students, especially in medical specialties, are a priority in COVID-19 vaccination; however, there a low level of their agreement to vaccinate was found. Therefore, interventional education programs are urgently needed to tackle vaccine hesitancy.59 Moreover, this study identified the following factors associated with acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine in Kazakhstan: contextual influences (e.g., communication and media environment, socio-demographic factors, vaccination policies, and perception of the pharmaceutical industry), individual and group influences (e.g., personal experience with vaccination, attitudes about health and prevention, trust in the health system and providers, perceived risk), and specific issues on COVID-19 vaccine/vaccination (e.g., risk/benefit, source of supply of vaccine, knowledge base on vaccination). The developed COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Scale COV-VHS is a reliable assessment method for identifying vaccination barriers in Kazakhstan.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank medical students at the Astana Medical University for their participation in this study.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this article.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization and Methodology: Aidos K. Bolatov, Telman Z. Seisembekov, and Dainius Pavalkis; Formal analysis and Investigation: Aidos K. Bolatov and Altynay Zh. Askarova; Writing - original draft preparation: Aidos K. Bolatov; Writing - review and editing: Telman Z. Seisembekov and Dainius Pavalkis; Supervision: Dainius Pavalkis.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Data availability statement

All data available by request to corresponding author.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Local Ethics Committee of Astana Medical University (extract from protocol No. 6 of April 6, 2020).

References

- 1.Li YD, Chi WY, Su JH, Ferrall L, Hung CF, Wu TC.. Coronavirus vaccine development: from SARS and MERS to COVID-19. J Biomed Sci. 2020. Dec 1;27. BioMed Central Ltd. doi: 10.1186/s12929-020-00695-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Excler JL, Saville M, Berkley S, Kim JH.. Vaccine development for emerging infectious diseases. Nat Med. 2021. Apr 1;27:591–600. Nature Research. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01301-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zakarya K, Kutumbetov L, Orynbayev M, Abduraimov Y, Sultankulova K, Kassenov M, Sarsenbayeva, G, Kulmagambetov, I, Davlyatshin, T, Sergeeva, M, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a QazCovid-in® inactivated whole-virion vaccine against COVID-19 in healthy adults: a single-centre, randomised, single-blind, placebo-controlled phase 1 and an open-label phase 2 clinical trials with a 6 months follow-up in Kazakhstan. EClinicalMedicine. 2021:101078. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.What you should know about the COVID-19 Vaccine. 2021. www.Coronavirus2020.Kz. https://www.coronavirus2020.kz/ru/vaccine.

- 5.Zhunusova A. Coronavirus vaccination began in Kazakhstan: what you need to know. Tengrinews.Kz. 2021. Feb 1. https://tengrinews.kz/kazakhstan_news/vaktsinatsiya-koronavirusa-nachalas-kazahstane-nujno-znat-427018/.

- 6.Smayil, M. Vaccination failure in Kazakhstan. Why Tokayev had to intervene. 2021 Apr 1. www.Tengrinews.Kz. https://tengrinews.kz/kazakhstan_news/proval-vaktsinatsii-kazahstane-pochemu-tokaevu-prishlos-433326/.

- 7.Larson HJ, Jarrett C, Schulz WS, Chaudhuri M, Zhou Y, Dube E, Hickler B, MacDonald NE, Wilson R. Measuring vaccine hesitancy: the development of a survey tool. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4165–75. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sallam M, Dababseh D, Eid H, Al-Mahzoum K, Al-Haidar A, Taim D, Yaseen A, Ababneh NA, Bakri FG, Mahafzah A. High rates of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and its association with conspiracy beliefs: a study in Jordan and Kuwait among other Arab countries. Vaccines. 2021;9(1):42. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9010042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freeman D, Loe B, Chadwick A, Vaccari C, Waite F, Rosebrock L, Jenner, L, Petit, A, Lewandowsky, S, Vanderslott, S, et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the UK: the Oxford coronavirus explanations, attitudes, and narratives survey (Oceans) II. Psychol Med. 2020:1–15. doi: 10.1017/S0033291720005188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisk RJ. Barriers to vaccination for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) control: experience from the United States. Glob Health J. 2021;5(1):51–55. doi: 10.1016/j.glohj.2021.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paul E, Steptoe A, Fancourt D. Attitudes towards vaccines and intention to vaccinate against COVID-19: implications for public health communications. Lancet Regional Health - Europe. 2021;1:100012. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2020.100012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin Y, Hu Z, Zhao Q, Alias H, Danaee M, Wong LP. Understanding COVID-19 vaccine demand and hesitancy: a nationwide online survey in China. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14(12):e0008961. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murphy J, Vallières F, Bentall RP, Shevlin M, McBride O, Hartman TK, Hyland P, Bennett K, Mason L, Gibson-Miller J. Psychological characteristics associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and resistance in Ireland and the United Kingdom. Nat Commun. 2021;12:1. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-20226-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dubé E, Laberge C, Guay M, Bramadat P, Roy R, Bettinger J. Vaccine hesitancy: an overview. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2013;9(8):1763–73. doi: 10.4161/hv.24657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kreps S, Prasad S, Brownstein JS, Hswen Y, Garibaldi BT, Zhang B, Kriner DL. Factors associated with US adults’ likelihood of accepting COVID-19 vaccination. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(10):e2025594. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.25594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shapiro GK, Tatar O, Dube E, Amsel R, Knauper B, Naz A, Perez S, Rosberger Z. The Vaccine Hesitancy Scale: psychometric properties and validation. Vaccine. 2018;36(5):660–67. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akhmetzhanova Z, Sazonov V, Riethmacher D, Aljofan M. Vaccine adherence: the rate of hesitancy toward childhood immunization in Kazakhstan. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2020;19(6):579–84. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2020.1775080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harrison EA, Wu JW. Vaccine confidence in the time of COVID-19. Eur J Epidemiol. 2020;35:325–30. doi: 10.1007/s10654-020-00634-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wallace AS, Wannemuehler K, Bonsu G, Wardle M, Nyaku M, Amponsah-Achiano K, Dadzie JF, Sarpong FO, Orenstein WA, Rosenberg ES, et al. Development of a valid and reliable scale to assess parents’ beliefs and attitudes about childhood vaccines and their association with vaccination uptake and delay in Ghana. Vaccine. 2019;37(6):848–56. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.12.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DeVellis RF. Scale development: theory and applications. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): SAGE Publications, Inc; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xia Y, Yang Y. RMSEA, CFI, and TLI in structural equation modeling with ordered categorical data: the story they tell depends on the estimation methods. Behav Res Methods. 2019;51(1):409–28. doi: 10.3758/s13428-018-1055-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taber KS. The use of Cronbach’s alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Res Sci Educ. 2018;48(6):1273–96. doi: 10.1007/s11165-016-9602-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Habibzadeh F, Habibzadeh P, Yadollahie M. On determining the most appropriate test cut-off value: the case of tests with continuous results. Biochem Med. 2016;26(3):297–307. doi: 10.11613/BM.2016.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Szmyd B, Bartoszek A, Karuga FF, Staniecka K, Błaszczyk M, Radek M. Medical students and SARS-CoV-2 vaccination: attitude and behaviors. Vaccines. 2021;9(2):128. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9020128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sallam M. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy worldwide: a systematic review of vaccine acceptance rates. Vaccines. 2020:2020120717. Preprints. doi: 10.20944/preprints202012.0717.v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ray BJ. Over 1 billion worldwide unwilling to take COVID-19 vaccine. Gallup.Com. 2021. May 7. https://news.gallup.com/poll/348719/billion-unwilling-covid-vaccine.aspx.

- 27.Issanov A, Akhmetzhanova Z, Riethmacher D, Aljofan M. Knowledge, attitude, and practice toward COVID-19 vaccination in Kazakhstan: a cross-sectional study. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021:1–7. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1925054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soares P, Rocha JV, Moniz M, Gama A, Laires PA, Pedro AR, Dias S, Leite A, Nunes C. Factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Vaccines. 2021;9(3):300. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9030300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Logunov DY, Dolzhikova IV, Shcheblyakov DV, Tukhvatulin AI, Zubkova OV, Dzharullaeva AS, Kovyrshina AV, Lubenets NL, Grousova DM, Erokhova AS. Safety and efficacy of an rAd26 and rAd5 vector-based heterologous prime-boost COVID-19 vaccine: an interim analysis of a randomised controlled phase 3 trial in Russia. Lancet. 2021;397(10275):671–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00234-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krivtsanova K. Kazakhstan’s vaccine is effective against new mutations COVID-19, said the head of the research institute. NUR.KZ. 2021, Apr 2. https://www.nur.kz/society/1905982-kazahstanskaya-vaktsina-effektivna-protiv-novyh-mutatsiy-covid-19-zayavila-glava-nii/.

- 31.Grochowska M, Ratajczak A, Zdunek G, Adamiec A, Waszkiewicz P, Feleszko W. A comparison of the level of acceptance and hesitancy towards the influenza vaccine and the forthcoming COVID-19 vaccine in the medical community. Vaccines. 2021;9(5):475. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9050475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rabi R, Maraqa B, Nazzal Z, Zink T. Factors affecting nurses’ intention to accept the COVID‐9 vaccine: a cross‐sectional study. Public Health Nurs. 2021;38:781–88. doi: 10.1111/phn.12907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Urrunaga-Pastor D, Bendezu-Quispe G, Herrera-Añazco P, Uyen-Cateriano A, Toro-Huamanchumo CJ, Rodriguez-Morales AJ, Hernandez, AV, Benites-Zapata VA. Cross-sectional analysis of vaccine intention, perceptions and hesitancy across Latin America and the Caribbean. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2021:102059. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2021.102059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zintel S, Flock C, Arbogast AL, Forster A, von Wagner C, Sieverding M. Gender differences in the intention to get vaccinated against COVID-19 - a systematic review and meta-analysis. SSRN. 2021. Mar 12. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3803323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Khubchandani J, Sharma S, Price JH, Wiblishauser MJ, Sharma M, Webb FJ. COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy in the United States: a rapid national assessment. J Community Health. 2021;46(2):270–77. doi: 10.1007/s10900-020-00958-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsai FJ, Yang HW, Lin CP, Liu JZ. Acceptability of covid-19 vaccines and protective behavior among adults in Taiwan: associations between risk perception and willingness to vaccinate against COVID-19. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:11. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18115579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Adeniyi OV, Stead D, Singata-Madliki M, Batting J, Wright M, Jelliman E, Abrahams S, Parrish A. Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine among the healthcare workers in the Eastern Cape, South Africa: a cross sectional study. Vaccines. 2021;9(6):666. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9060666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.MacDonald NE, Eskola J, Liang X, Chaudhuri M, Dube E, Gellin B, Goldstein S, Larson H, Manzo M, Reingold A, et al. Vaccine hesitancy: definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4161–64. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baghdadi LR, Alghaihb SG, Abuhaimed AA, Alkelabi DM, Alqahtani RS. Healthcare workers’ perspectives on the upcoming COVID-19 vaccine in terms of their exposure to the influenza vaccine in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study. Vaccines. 2021;9(5):465. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9050465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schwarzinger M, Watson V, Arwidson P, Alla F, Luchini S. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in a representative working-age population in France: a survey experiment based on vaccine characteristics. Lancet Public Health. 2021;6(4):e210–e221. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00012-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lazarus JV, Ratzan SC, Palayew A, Gostin LO, Larson HJ, Rabin K, Kimball S, El-Mohandes A. A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nat Med. 2021;27(2):225–28. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1124-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dror AA, Daoud A, Morozov NG, Layous E, Eisenbach N, Mizrachi M, Rayan D, Bader A, Francis S, Kaykov E. Vaccine hesitancy due to vaccine country of origin, vaccine technology, and certification. Eur J Epidemiol. 2021;36(7):709–14. doi: 10.1007/s10654-021-00758-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zarobkiewicz MK, Zimecka A, Zuzak T, Cieślak D, Roliński J, Grywalska E. Vaccination among Polish university students. Knowledge, beliefs and anti-vaccination attitudes. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017;13(11):2654–58. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2017.1365994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kernéis S, Jacquet C, Bannay A, May T, Launay O, Verger P, Pulcini C, Abgueguen P, Ansart S, Bani-Sadr F; EDUVAC Study Group . Vaccine education of medical students: a nationwide cross-sectional survey. Am J Prev Med. 2017;53(3):e97–e104. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rostkowska OM, Peters A, Montvidas J, Magdas TM, Rensen L, Zgliczyński WS, Durlik M, Pelzer BW. Attitudes and knowledge of European medical students and early graduates about vaccination and self-reported vaccination coverage—multinational cross-sectional survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(7):7. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18073595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lucia VC, Kelekar A, Afonso NM. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among medical students. J Public Health (Oxford, England). 2020. fdaa230. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdaa230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McKee M, Rajan S. What can we learn from Israel’s rapid roll out of COVID 19 vaccination? Isr J Health Policy Res. 2021. Dec 1. BioMed Central Ltd. doi: 10.1186/s13584-021-00441-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marchildon GP. The rollout of the COVID-19 vaccination: what can Canada learn from Israel?. Isr J Health Policy Res. 2021. Dec 1. BioMed Central Ltd. doi: 10.1186/s13584-021-00449-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rosen B, Waitzberg R, Israeli A. Israel’s rapid rollout of vaccinations for COVID-19. Isr J Health Policy Res. 2021;10:1. doi: 10.1186/s13584-021-00440-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Talukdar D, Stojkovski K, Suarez D. Role of information technology in COVID19 vaccination drive: an analysis of the COVID-19 global beliefs, behaviors, and norms survey. 2021. p. 2021040552. Preprints. doi: 10.20944/preprints202104.0552.v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Schoch-Spana M, Brunson EK, Long R, Ruth A, Ravi SJ, Trotochaud M, Borio L, Brewer J, Buccina J, Connell N, et al. The public’s role in COVID-19 vaccination: human-centered recommendations to enhance pandemic vaccine awareness, access, and acceptance in the United States. Vaccine. 2020:S0264-410X(20) 31368–2. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.10.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Solís Arce JS, Warren SS, Meriggi NF, Scacco A, Mcmurry N, Voors M, Syunyaev G, Malik AA, Aboutajdine S, Adeojo O, et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and hesitancy in low- and middle-income countries. Nat Med. 2021;27(8):1385–94. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01454-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tavolacci MP, Dechelotte P, Ladner J. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance, hesitancy, and resistancy among university students in France. Vaccines. 2021;9(6):654. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9060654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Saied SM, Saied EM, Kabbash IA, Abdo SAEF. Vaccine hesitancy: beliefs and barriers associated with COVID-19 vaccination among Egyptian medical students. J Med Virol. 2021;93(7):4280–91. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Akel KB, Masters NB, Shih SF, Lu Y, Wagner AL. Modification of a Vaccine Hesitancy Scale for use in adult vaccinations in the United States and China. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1884476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Freeman D, Loe BS, Chadwick A, Vaccari C, Waite F, Rosebrock L, Jenner, L., Petit, A., Lewandowsky, S., Vanderslott, S, et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the UK: the Oxford coronavirus explanations, attitudes, and narratives survey (Oceans) II. Psychol Med. 2021. doi: 10.1017/S0033291720005188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rodriguez VJ, Alcaide ML, Salazar AS, Montgomerie EK, Maddalon MJ, Jones DL. Psychometric properties of a Vaccine Hesitancy Scale adapted for COVID-19 vaccination among people with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2021:1–6. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1007/s10461-021-03350-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Biswas N, Mustapha T, Khubchandani J, Price JH. The nature and extent of COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy in healthcare workers. J Community Health. 2021. doi: 10.1007/s10900-021-00984-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dror AA, Eisenbach N, Taiber S, Morozov NG, Mizrachi M, Zigron A, Srouji S, Sela E. Vaccine hesitancy: the next challenge in the fight against COVID-19. Eur J Epidemiol. 2020;35(8):775–79. doi: 10.1007/s10654-020-00671-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data available by request to corresponding author.