Summary

Low-and middle-income countries (LMIC) are faced with healthcare challenges including lack of specialized healthcare workforce and limited diagnostic infrastructure. Task shifting for point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) can overcome both shortcomings. This review aimed at identifying benefits and challenges of task shifting for POCUS in primary healthcare settings in LMIC. Medline and Embase were searched up to November 22nd, 2021. Publications reporting original data on POCUS performed by local ultrasound naïve healthcare providers in any medical field at primary healthcare were included. Data were analyzed descriptively. PROSPERO registration number CRD42021223302. Overall, 36 publications were included, most (n = 35) were prospective observational studies. Medical fields of POCUS application included obstetrics, gynecology, emergency medicine, infectious diseases, and cardiac, abdominal, and pulmonary conditions. POCUS was performed by midwives, nurses, clinical officers, physicians, technicians, and community health workers following varying periods of short-term training and using different ultrasound devices. Benefits of POCUS were yields of diagnostic images with adequate interpretation impacting patient management and outcome. High cost of face-to-face training, poor internet connectivity hindering telemedicine components, and unstable electrici'ty were among reported drawbacks for successful implementation of task shifting POCUS. At the primary care level in resource-limited settings task shifting for POCUS has the potential to expand diagnostic imaging capacity and impact patient management leading to meaningful health outcomes.

Keywords: Point of care, Ultrasound, Task shifting, Low- and middle-income country

Introduction

Low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) are faced with healthcare challenges that disrupt successful implementation of health services creating inequitable access to care and entailing poor health outcome.1 Core to these challenges are lack of specialized health workforce and diagnostic infrastructure.2, 3, 4, 5, 6 Combining task shifting and point-of-care diagnostics can overcome these shortcomings.

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends task shifting as one strategy to strengthen and expand health workforce.7, 8, 9 By task shifting, specific tasks are moved from highly qualified health workers to health workers with shorter training and less qualifications in order to increase efficiency of available human resources for health.7 Key elements, including quality assurance mechanisms, standardized training and certification have been recommended to ensure a safe, efficient, effective, equitable and sustainable task shifting approach.7

Diagnostic imaging plays an important role in time-sensitive management of many conditions. In LMIC, diagnostic imaging services are limited and the quality of service varies significantly.4,10,11 Factors associated with limited availability and varying quality of diagnostic imaging in LMIC include the lack of or inadequate diagnostic imaging equipment, the lack of skilled human resources to operate and maintain equipment, and insufficient training capacity in diagnostic imaging.4

Progress in technology has advanced the development of portable, easy to use and affordable point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) devices that allow imaging at the patient's bedside.4,11 POCUS is a promising task shifting approach moving sonographic imaging from radiology departments to frontline healthcare.12 POCUS improves health outcomes by improved and timely diagnosis resulting in expedited clinical decision-making, and reduces lengths of hospital stays, need for referrals and costs.12, 13, 14

In this review we focus on benefits and challenges of POCUS tasks shifted to ultrasound naïve care providers at the primary level of care in LMIC. We thereby apply a comprehensive concept of task shifting for POCUS that is not limited to the fundamental task shifting of sonographic imaging away from radiology services to the bedside clinician but also includes further task shifting of sonographic imaging to health workers with shorter training and less qualifications than clinicians.

Methods

We reviewed literature following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines.15 The electronic databases Medline (Ovid, 1946 to present) and Embase (Ovid, 1947 to present) were searched on 23rd of January 2021; a search update was performed on 22nd November 2021. Key search terms included ‘point of care’, ‘ultrasonography’ and ‘low- and middle-income countries’ (Appendix 1). Synonyms for ‘Point of care’ included ‘handheld’ or ‘hand-carried’ or ‘portable’ or ‘mobile’ or ‘focused’ or ‘pocket’ or ‘bedside’. LMIC was defined using the World Bank definition of developing countries16 and the synonyms ‘resource limited setting’ or ‘developing country’ or ‘remote setting’ were applied. Synonyms of ultrasonography included ‘ultrasound’ or ‘echography’ or ‘sonography’.

The study was exempt from institutional review board approval and the review protocol was published on PROSPERO with registration number CRD42021223302.

Eligibility criteria for inclusion of publication

Task shifting for POCUS was defined as focused bedside ultrasound performed by health care providers with ultrasound training limited to the respective POCUS examinations. We included publications describing POCUS performed at the primary care level in all medical fields in LMICs by local healthcare providers (including primary care physicians, nurses, midwives, clinical officers, medical assistants, radiology technicians and community health workers) who had not primarily undergone ultrasound training. We excluded studies on POCUS performed by healthcare professionals whose formal training includes training in ultrasound (i.e. specialized or specializing doctors emergency medicine, obstetrics/gynaecology and cardiology, as well as specialized or specializing radiologists or sonographers), on POCUS performed by healthcare workers with basic ultrasound training according to WHO,17 and studies on POCUS training only without clinical application. Publications without original data (editorials, comments, and conference abstracts) and non-human studies were excluded. We made no restrictions regarding language of publication, year of publication nor patient population.

Data selection and extraction

We organized publications in ENDNOTE X9.18 Title and abstract screening were performed with Rayyan QCRI, a web and mobile app for systematic reviews.19 Two reviewers (SKA, LCR) performed title and abstract screening based on the pre-specified eligibility criteria. Discrepancies were resolved by a third reviewer (CCH). We performed full text screening of potentially eligible publications after title and abstract screening. Two independent reviewers (SKA and LCR) screened all full texts. Disagreement on full text assessment was also resolved by discussion with a third reviewer (CCH).

Following satisfactory non-discrepant comparison of a random 15% of data extraction performed by two reviewers (SKA, CCH), data of the other 85% citations were extracted by one reviewer (SKA or CCH) and checked by the other reviewer (SKA or CCH). The following data were extracted: first author, title, year of publication, study design, country, type of POCUS examination, type of ultrasound device, duration of POCUS training, mode of delivery of POCUS training, condition examined, outcome measured, type of healthcare providers performing POCUS, benefits of POCUS, and drawbacks of task shifting for POCUS.

Assessment of risk of bias

The methodological quality and risks of bias were assessed by two independent reviewers (SKA, LCR) for each publication using a modified National Heart, Lung and Blood institutes protocol for observational studies (Appendix 2, 3) and National Heart, Lung and Blood institutes protocol for controlled randomized studies (Appendix 4).20

Data analysis

Findings were analysed using Microsoft Excel 365 (version 16.57) and presented in a descriptive way in text and tables; sums and percentages were calculated or extracted from original studies, where appropriate.

Role of the funding source

There was no funding source in developing the study protocol; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication. All named authors had access to the data, contributed to the drafting and revising of the manuscript and agreed to submit for publication.

Results

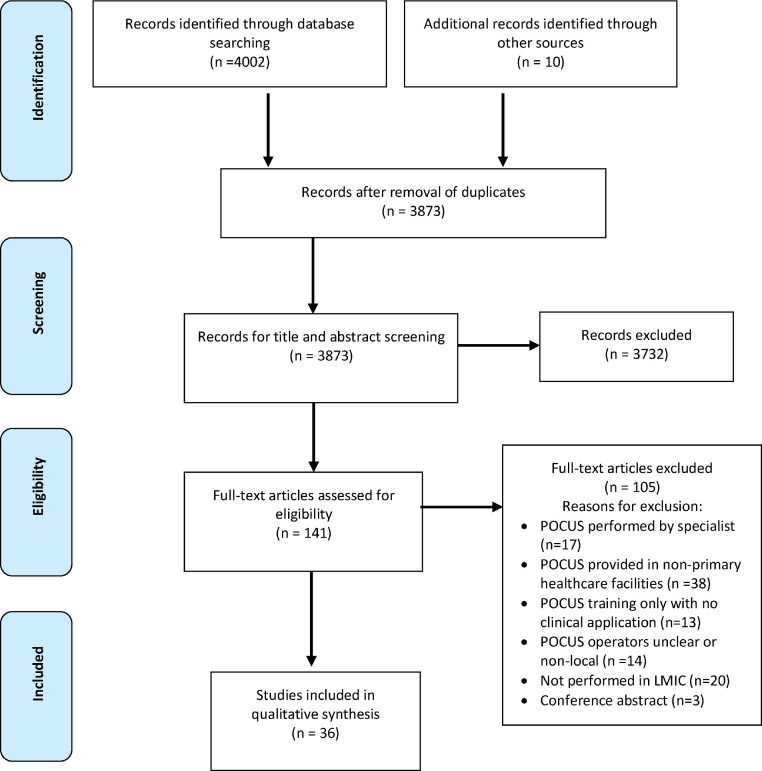

The database search yielded 3873 unique publications. One hundred and forty-one publications were retrieved for full text screening after title and abstract screening. Thirty-six publications were selected for synthesis (Figure 1).21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48 Thirty-five studies were prospective observational studies and one randomized controlled trial.30 The majority of the included publications (n = 20) were conducted on the African continent,21,22,31, 32, 33, 34, 35,37,39,40,42, 43, 44,46,47,49, 50, 51, 52, 53 nine studies originated from the Americas,24,27,29,38,41,45,54, 55, 56 two from Asia,26,36 and three from Oceania23,28,57 as shown in Figure 2. Two studies were multi-national studies.30,58

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow diagram of study selection.

Figure 2.

Medical fields and conditions of task shifting for POCUS studies identified by this review across continents. The outer circle displays POCUS applications, the inner circle continents where POCUS applications were applied. The relative sizes of cells indicate the frequency of studies evaluating respective POCUS applications and the continent origin, respectively. (POCUS: point-of-care ultrasound, FAST: focused assessment with sonography for trauma, FASH: focused assessment with sonography for HIV-associated tuberculosis, FASE: focused assessment with sonography for echinococcosis).

Risk of bias assessment

Of the 35 observational studies, ten were of high, twenty-two of moderate and three of low methodological quality (Appendix 2). Most studies were found with high risk of bias for sample size justification (selection bias) as shown in the supplementary material (Appendix 3). Twenty-one (60%) of the studies were associated high risk of bias regarding controlling for confounders and eight (23%) were associated with a high risk of detection bias as blinded assessment was not performed. The randomized controlled trial was of moderate methodological quality but associated with high risk of bias as concealed allocation of intervention and blinding assessment was not used (Appendix 4).

Applications of task shifting POCUS

There was a substantial range of clinical areas and conditions for which task shifting for POCUS was applied. All studies primarily examined the impact of task shifting for POCUS as a diagnostic or screening tool in LMIC as shown in Table 1. Ten publications reported on task shifting for POCUS in obstetric care, examining pregnancy and pregnancy related complications.24, 25, 26,30,31,34,35,43,46,47 Nine and three publications reported on task shifting for chest POCUS for cardiac and pulmonary conditions respectively, including rheumatic heart disease screening, diagnosing cardiac structural anomalies, aneurysms and deep vein thrombosis,23,28,30,36,38,39,45,55,57,58 and lung examinations to diagnose conditions such as pneumonia, tuberculosis, pleural effusion and atelectasia.29,53,59 Further reported task shifting for POCUS applications included abdominopelvic examination for liver, gallbladder diseases, and kidney diseases, prostate hypertrophy and urinary tract infection,21,32,41,42,44,54 breast and axillary examination for breast cancer screening,40,56 examination in trauma patients for pneumothorax and internal haemorrhage,48 examination for HIV associated tuberculosis,33 and screening for abdominal cystic echinococcosis.22,27

Table 1.

Overview of medical fields and conditions of task shifting POCUS applications in primary care in LMIC identified by this review

| Medical field/Organ system | Application |

|---|---|

| Obstetrics and perinatal care |

|

| Gynaecology | |

| Cardiac and vascular US | |

| Lung | |

| Emergency/Trauma | |

| Abdomen |

|

| Infectious diseases |

POCUS: point-of-care ultrasound, LMIC: low- and middle-income countries, eFAST/FAST: (extended) focused assessment with sonography for trauma, HIV: human immunodeficiency virus, FASH: focused assessment with sonography for HIV-associated tuberculosis, FASE: focused assessment with sonography for echinococcosis.

POCUS training and POCUS operators

Duration and mode of training of POCUS operators in respective POCUS applications were described by all publications except one.33 Training included theoretic sessions, hands-on practice, and supervised and unsupervised scans sessions. Duration and scope of training varied between studies (Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5). Most trainings were provided face-to-face, but online training was also reported. Most of the trainers were non-local POCUS trainers, who subsequently provided remote support for the trainees. Healthcare providers that were trained as POCUS operators included nurses, general physicians, residents, medical students, medical graduates, midwives, clinical officers, technicians, nursing assistants, and community health workers (CHW).

Table 2.

Overview of studies applying task shifting POCUS in obstetric care in primary care in LMIC.

| First author /Year | Country/ Setting | POCUS Operator | POCUS device | Training and duration of training | POCUS benefits identified in publication | Drawbacks of POCUS implementation. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kimberly et al. 201035 | Zambia/ Rural health centres and provincial hospital | Midwives | Sonosite 180; Sonosite Inc., Bothell, WA, USA | Didactics courses, hands-on instruction, supervised scanning 3 weeks | Change in clinical decision-making in 17% (74/441) examinations | Heavy workload impeding integration of POCUS in daily care Difficulty in learning skills Absence of supervision |

| Greenwold et al. 201431 | Mozambique/ Rural Health centres | Nurse, Clinical officer | 2 M-Turbo (Sonosite, Bothell, WA, USA) | Lectures, hands-on training 8 weeks | Identification of high-risk pregnancies and uterine fibroids in 23.5% (407/1734) leading to a change in management Referral of 3.6% (62/1734) women to district hospital Primary caesarean section in 1% (21/1734) |

None reported |

| Swanson et al. 201446 | Uganda/ Rural health centres | Midwives | GE Logiq E ultrasounds (GE Healthcare Clinical Systems, Wauwatosa, WI, USA) | Lectures, small-group tutorials, audio-visual material, supervised scanning 6 weeks | Change in diagnosis in 11% (100/939) 18/25 patients referred based on POCUS findings were confirmed with pathology |

None reported |

| Kawooya et al. 201536 | Uganda/ Rural health centres | Midwives | LOGIQe ultrasounds (GE Healthcare Clinical Systems, Wauwatosa, WI, USA) | Lectures, small group tutorials, audio-visual materials, supervised scanning 3 months |

Increased utilization of and adherence to ANC services Increase in facility-based deliveries and obstetric referrals |

None reported |

| Crispín Milart et al. 201624 | Guatemala/ Rural communities | Nurse | Laptop and USB ultrasound probe | Theoretical lessons, supervised practical sessions with pregnant women 1 week |

No maternal mortality in intervention group compared to 5 maternal mortalities in control group 64 % reduction in neonatal mortality in intervention group Non-urgent referral recommended in 9.2% |

Training is demanding and requires regular reinforcement |

| Viinayak et al. 201747 | Kenya/ Rural clinics | Midwives | Tablet-sized ultrasound scanner VISIQ (Philips Ultrasound, Inc., Bothell, WA, USA) | Daily lectures, daily hands-on work 4 weeks | Correct identification of high-risk pregnancies and referral to appropriate facility for further management | None reported |

| Goldenberg et al. 201830 | Zambia, Kenya, DRC, Pakistan, Guatemala / Rural and semi-urban health facilities | Ultrasound naïve health providers | Not reported | Didactic lectures, hands-on training 2 weeks | US-naïve providers were successfully trained to conduct basic obstetric POCUS examination No benefits of task shifting POCUS identified |

None reported |

| Dalmacion et al. 201826 | Philippines/ Rural and Urban communities | General physician, nurse, midwives | GE Vscan US | Lecture, hands-on training with pregnant women 3 days |

6.3% of maternal deaths and 14.6% of neonatal deaths were possibly averted by POCUS screening | None reported |

| Crispín Milart et al. 201925 | Guatemala/ Rural communities | Nurse | Laptop and USB ultrasound probe | Theoretical and practical sessions Duration not reported |

Identification and referral of most risk-pregnancies in time | None reported |

| Shah et al. 202043 | Uganda/ District hospital and health centres | Midwife, registered nurse | Not reported | Didactic and practical components2 weeks | Confidence and skills to detect high-risk conditions in pregnancy | Delay in feedback due to limited internet Power outages High cost of internet bundle affects data transfer |

Table 3.

Overview of studies applying task shifting chest POCUS in primary care in LMIC.

| First author/Year | Country/Setting | Type of POCUS | POCUS Operator | POCUS device | Training and duration of training | POCUS benefits identified in publication | Drawbacks of POCUS implementation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colquhoun et al. 201323 | Fiji/ Rural primary schools | Cardiac US | Nurses | Portable Mindray machine (Mindray Diagnostic Ultrasound System Model M5, Mahwah, New Jersey, United States of America) | Workshop to follow screening protocol, supervised hands-on training 3 weeks | Skills to operate portable echocardiography and competence to detect findings suggestive of rheumatic heart disease with high sensitivity and reasonable specificity | Lack of algorithm to guide rheumatic heart disease echocardiographic |

| Engelman et al. 201628 | Fiji/ Schools | Cardiac US | Nurses | M-Turbo portable ultrasound machine (SonoSite Inc., Bothell, WA) | Classroom-based workshops, practical training 8 weeks | Generation of adequate images in 96.6% Detection and measurement of regurgitation with adequate reliability feasible |

None reported |

| Shah et al. 201645 | Haiti/ Regional referral centre | Cardiac US, Lung US | Residents | Sonosite Micromaxx (SonoSite Inc., Bothell, WA) | Didactic training, supervised practice 3 weeks | POCUS examination changed diagnosis in 15.4% (18/117) patients POCUS changed management modality in 19.6% (23/117) patients |

None reported |

| Nascimento et al. 201638 | Brazil/Primary and secondary schools | Cardiac US | Nurse, biomedical technician, imaging technician | Vivid Q® or VSCAN®, GE Healthcare (Milwaukee, WI, USA) | Online education, hands-on training 12 weeks | High quality imaging achieved Telemedicine useful to support non-expert team remotely in interpretation Lower costs of handheld devices permit concurrent work of more screeners |

None reported |

| Ploutz et al. 201639 | Uganda/ Public primary schools | Cardiac US | Nurses | Vivid Q® and VSCAN®, GE Healthcare (Milwaukee, WI, USA) | Didactic session, hands-on training 2.5 days with previous limited 6 months experience |

Sensitivity of around 90% for identification of definite RHD and adequate specificity | Technical issues due to overheating and short battery life |

| Kirkpatrick et al. 201836 | Vietnam/ Village health clinic | Cardiac US | Nurses | Laptop-sized device (M7; Midray Shenzhen, China) | Lecture, image review, practice1 day | POCUS augmented nurse examination with electrocardiography increased accuracy in diagnosis to 91.5% | None reported |

| Nadimpalli et al. 201996 | South Sudan/ District hospital | Paediatric lung US | Clinical officer | Philips Lumify linear probe 5–12 MHz (Bothell, WA) and Nvidia Shield 2 tablet (Santa Clara, CA) | Didactic session, bedside teaching, practice 2 days |

POCUS algorithm to diagnose pneumonia and other pulmonary diseases in children < 5 years old through a focused, field-based training is feasible |

|

| Fentress et al. 202029 | Peru/Not specified | Lung US | General practitioners | Sonosite Micromaxx (FUJIFILM Sonosite, Bothell, WA) | Not specified 30 hours training |

Possible role in screening and diagnosing PTB in areas without ready access to CXR | None reported |

| Salisbury et al. 202152 | Tanzania/Rural and urban health facilities | Paediatric lung US | Clinicians | Mindray DP-10 model | Theoretical and practical training on lung ultrasound Refresher IMCI training Supervised practical training 6 weeks |

Lung ultrasound plays a role in misdiagnosis (underdiagnosis and overdiagnosis) of childhood pneumonia | None reported |

| Muhame et al. 202158 | Médecins Sans Frontières sites – multi-site study | Cardiac US | Clinicians | Not reported | 4 weeks of face to face didactic lectures 50 hours of scanning |

Change in management occurred in 75% (122/163) cases in whom a diagnosis was possible on focussed cardiac ultrasound including addition and removal of medications, changes to drug dosing, initiation of other supportive therapies or withdrawal of care | None reported |

| Voleti et al, 202157 | Republic of Palau/School Setting | Cardiac US | Nurses, Physicians, Medical student, Patient care technician | Vscan Extend ultrasound machines (General Electric, Milwaukee, WI, USA) | 2 weeks web-based curriculum Two hands on session (1.5 hours each) 11 hours of face-to-face, hands-on learner training |

Non-experts’ cardiac POCUS for the screening and detection of RHD can be achieved with reasonable sensitivity and specificity. Novel educational tool is a useful real-time adjunct to traditional computer-based training in enabling novice learner screening for RHD |

This tool potentially has less utility in users whose routine practice with handheld ultrasound has been established |

| Nascimento et al, 202055 | Brazil | Cardiac US | Nurses and Technicians | (VScan®, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI) | at least 32 hours of hands-on practice utilizing hand-held machines | Implementing task shifting for POCUS (ECHO) in prenatal care is feasible Integrating prenatal cardiovascular screening into the primary care level may be essential to improve heart disease diagnosis |

None reported |

US: ultrasound, IMCI: Integrated management of childhood illness, CXR: Chest X-ray, RHD: Rheumatic heart disease.

Table 4.

Overview of studies applying task shifting multi-organ POCUS in primary care in LMIC.

| First author /Year | Country/ Setting | Type of POCUS | POCUS Operator | POCUS device | Training and duration of training | POCUS benefits identified in publication | Drawbacks of POCUS implementation. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adler et al. 200821 | Tanzania/ Refugee camp | Abdominal, cardiac, lung, obstetric, trauma, soft tissue | Clinical officers | SonoSite Titan® (SonoSite Inc, Seattle, WA, USA) |

Didactic and practical sessions 4 days 20 or more supervised exams |

Useful diagnostic tool mostly for pelvic and obstetric conditions Good distinction between ovarian cysts and uterine fibroids Useful for identifying (twin) pregnancies and progression of pregnancy |

No qualified sonographer going forward Unable to transmit images due to lack of internet access No comparison with “formal” ultrasound or CT Quality data decreased over time due to poor supervision |

| Shah et al. 200944 | Rwanda/ Rural hospitals | Abdominal (Hepato- biliary & renal), cardiac, vascular, obstetric, DVT, vascular access, abscess (drainage) | Physicians | SonoSite Micromaxx® (SonoSite Inc, Bothell, WA, USA) |

Lectures followed by practical hands-on scanning 9 weeks |

Useful diagnostic tool especially in women's health and obstetrics May influence patient management; 43% change in management Most common changes: a) indication for surgical procedure (caesarean section, biopsy, minor surgery), b) medication changes (adding furosemide), c) referral to specialist Ultrasound program led by local health care providers can be sustainable |

None reported |

| Kolbe et al.,201496 | Nicaragua/ Village clinic | Abdominal, pelvic, obstetric | Two physicians, clinic nurse, nursing assistant | Sonosite, Titan®, Seattle, WA, USA |

Didactic sessions, practical workshops Duration not reported |

After POUCS 52% received a new diagnosis With a change in management in 48% |

Unreliable electricity supply Poor internet connection Knowledge to maintain the ultrasound machiner Risk of theft and vandalism |

| Henwood et al. 201732 | Rwanda/ Provincial hospitals | Abdominal, cardiac, lung, obstetric, soft-tissue | General physician | Not reported | Not specified

|

Most frequently used for abdominal and obstetric examination Change in management in 81.3% Most common changes: a) medication (42.4%, mainly diuretics), b) admission (30%), c) transfer to higher level of care (28.1%), d) procedures (23.3%) FAST had a strong impact on management Long-term use of POCUS |

Cost of training, training ultrasound device, maintenance of ultrasound device and image archiving (Technical) problems with image archiving |

| Rominger et al. 201841 | Mexico/ Rural clinics | Obstetric, abdominal, pelvic, lung, soft tissue, musculo-skeletal, cardio-vascular, ocular Obstetric, abdominopelvic | General physician | Sonosite nanomaxx | Lectures, hands-on training 4 days training, recurring every 3–4 months for 1 year3–4 month |

Most frequently used for obstetric and abdominal examination POCUS changed diagnosis in 34% and clinical management in 30% In unsupervised scanning POCUS changed the diagnosis in 34% of scans and changed clinical management in 31% |

Incomplete ultrasound log Problems with archiving images High turnover of supervision Possible language barrier between local physicians and supervisors |

| Sabatino et al. 202042 | Sierra Leone/ Rural hospital | Lung, abdominal, pelvic, trauma | Community health officers | Esaote® MyLab™Alpha | Theoretical and hands-on training course 2 weeks |

Abdominal (66.3%) and chest (24.5%) ultrasound most frequently performed 17.1% change of diagnosis after POCUS, leading to change in management |

To keep ultrasound programme sustainable, successful training programs for local practitioners should be implemented |

Table 5.

Overview of studies applying task shifting POCUS in primary care in LMIC for emergency care, trauma, infectious disease, and breast cancer.

| First author /Year | Country | Type of POCUS | POCUS Operator | POCUS device | Training and duration of training | POCUS benefits identified in publication | Drawbacks of POCUS implementation. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Levine et al. 201037 | Rwanda/ District hospital | Aorta inferior - vena cava ratio (severe dehydration) | Physicians | Sonosite Micromaxx (Bothell, WA) | Didactic presentation, hands-on scanning Duration not reported |

Aorta inferior - vena cava ratio is a relatively accurate and reliable predictor of severe dehydration in children with diarrhoea and/or vomiting POCUS may be a useful adjunct to clinical exam in guiding management |

None reported |

| Bonnard et al. 201151 | Senegal/ Rural communities | Vesico-urinary | Clinician versus radiologist | GE LOGICe | Not specified 8 days |

Diagnosis and surveillance of Schistosoma haematobium related lesions | None reported |

| Del Carpio et al. 201227 | Patagonia, Chile, Argentina /Rural communities | Abdomen (FASE) | General practitioners, residents | Not reported | Lectures, practice 20 hours |

Identification of cystic echinococcosis Minimization of social and health care costs |

High turnover of rural doctors |

| Chebli et al. 201722 | Morocco/ Rural communities | Abdomen (FASE) | General practitioners | Not reported | Lectures, hands-on training 24 hours |

Accurate diagnosis of abdominal cystic echinococcosis | None reported |

| Terry et al. 201996 | Uganda/ Rural emergency centre | FAST | Medical students, medical graduates | Sonosite Micromaxx (Bothell, WA) |

Lecture, hands-on training Dispersed training over one month |

Increased utilisation of POCUS for patient management with Remotely delivered quality assurance fosters skills and continued use of POCUS |

Loss of POCUS data Delayed feedback |

| Kahn et al. 202033 | Malawi / Private health care centre | FASH | Clinical officer, medical doctor | Philips ClearVue 650 | Not reported | POCUS supported clinical decision making in 76% of encounters POCUS augments the clinician's ability to make a timely diagnosis |

None reported |

| Raza et al. 202140 | Rwanda/ Rural hospital | Breast | Nurse, midwife, general practitioners | Fujifilm Sonosite, (Bothell, Washington) | Didactic lectures, practical session, remote mentorship 9 weeks |

POCUS supplements clinical breast examination in the absence of mammography POCUS facilitates accurate patient triage, improves patient access to diagnostic services, and optimizes use of limited resources |

None reported |

| Aklilu et al. 202156 | Peru/ Rural primary care center | Breast | Primary care physician | VINNO E30 (Sozhou, China) or SAMSUNG MEDISON ACUVIXXG (Seoul, Korea). | Didactic sessions and practical sessions 8 hours daily for 2 days |

Task shifting for POCUS combined clinical breast examination led to change in management in 29.2% of cases (mostly increasing biopsies), and 66.7% with condensed and full BI-RADS (mostly decreasing biopsies) | None reported |

FAST: focused assessment with sonography for trauma, FASH: focused assessment with sonography for HIV-associated tuberculosis, FASE: focused assessment with sonography for echinococcosis.

Clinical benefits of obstetrics POCUS

Ten publications reported on task shifting for POCUS in obstetric care (Table 2). POCUS interventions aimed at sonographic identification of high-risk pregnancy, increased accuracy of obstetric diagnoses, POCUS-guidance on clinical decision-making, increased utilization of antenatal care services, increased deliveries by skilled birth attendants and in healthcare facilities, and reduced maternal and neonatal mortality.24, 25, 26,30,31,34,35,43,46,47 High risk pregnancies such as foetal mal-presentation, placenta previa, amniotic fluid abnormalities, multiple gestation and intra-uterine growth restrictions were identified by midwives and nurses during the prenatal period,24,31 and at labour.43 Task shifting for POCUS services improved accuracy of diagnosis when compared with clinical exam only; midwives applying POCUS corrected their diagnosis in around 7% of examinations46 or changed their clinical decision making in 17% following POCUS examinations.35 Task shifting ultrasound increased utilization of antenatal care (ANC) services and motivated women to comply with the recommended ANC schedule and complete four ANC visits.34 An increase in facility-based deliveries and obstetric referrals to Comprehensive Emergency Obstetric Care facilities (CEmOC) were reported by this study.34 A study from the Philippines showed that 6.3% of maternal deaths and 14.6% of neonatal deaths were averted by introducing task shifting for POCUS services by CHW.26 On the contrary, a multi-country cluster randomized controlled trial, reported that introducing task shifting for POCUS services as routine antenatal ultrasound did not increase the use of ANC and the rate of hospital births for women with complications, nor did it improve the composite outcome of maternal, and neonatal mortality, and near-miss maternal mortality.30

Clinical benefits of chest POCUS

Task shifting for cardiac and lung POCUS were described in nine23,28,36,38,39,45,55,57,58 and three29,52,53 studies respectively. Cardiac examinations focused on using handheld echocardiography to screen structural cardiac abnormalities and was primarily performed by nurses (Table 3). Cardiac POCUS was used to screen for rheumatic heart disease (RHD) in pediatric populations by obtaining qualitative images of pathologies such as mitral and aortic regurgitation with satisfactory interobserver agreement when compared with experienced reviewers.23,28,38,39,55,57 Task shifting for cardiac POCUS was also used to diagnose heart failure and hypertensive heart disease in the adult population.36,45

Task shifting POCUS for lung examination was reported to be a feasible tool for both, healthcare facility and community-based diagnosis of lung pathologies, including pneumonia, pleural effusion, atelectasis, and tuberculosis for both in the pediatric and adult population.29,52,53

Clinical benefits of multi-organ POCUS

Six studies applied task shifting for POCUS to examine a combination of different organ systems comprising abdominal/pelvic, heart, lung, and soft tissue POCUS.21,32,41,42,44 Task shifting for POCUS by CHW in Sierra Leone led to changes in the initial diagnosis in 34% (196/ 584) of examinations and changes in patient management in 29% (171/584) of the patients (Table 4).41 A study from Rwanda observed similar findings with change in patient management in 81.3% of patients after POCUS by general physicians32; most common changes in patient management related to medication administration (42.4%), admission (30%), change in surgical procedure (23.3%), and transfer to a higher level of care (28.1%).

Clinical benefits of POCUS for emergency care, trauma, infectious diseases, and breast cancer

Three studies reported the use of task shifting for POCUS for trauma (FAST); one study focused exclusively on FAST,48 while the other two performed FAST as part of multi-organ examinations.21,42 General physicians and non-physician clinicians including medical students, clinical officers, and CHW obtained quality ultrasound images and accurately interpreted the findings. Together with feedback from specialists, diagnostic accuracy of FAST examinations improved patient management.

Utilization of task shifting for POCUS for tuberculosis (FASH) in Malawi was reported as an important adjunctive diagnostic tool to augment clinicians’ ability to diagnose tuberculosis.33

Task shifting for POCUS for screening cystic echinococcosis (FASE) in Morocco and Patagonia were performed with good accuracy by general practitioners and residents for detection of cyst.22,27

Similarly, in Rwanda and Peru nurses, midwives, and general practitioners used POCUS to supplement clinical examination for breast cancer and associated axillary lesions40,56 and assess for signs of severe dehydration in children with diarrhoea and/or vomiting by examining the aorta and inferior vena cava ratio,37 and in Senegal for surveillance of Schistosoma haematobium morbidity51 (Table 5).

Benefits and drawbacks of task shifting POCUS

The many clinical benefits of POCUS on patient management have been described within the above sections; in summary the major clinical benefits include improved diagnosis and support in clinical decision making leading to better bedside management but also adequate referral, increased use of health services, and ultimately better health outcomes. Additional benefits identified include availability of imaging at primary health care level, empowerment of frontline health care workers, saving of costs by identifying needless referrals. Challenges of task shifting for POCUS including drawbacks to successful implementation and sustainability were described in 13 (37%) of the publications.21,23,24,27,32,35,39,41,43,44,50,54,57 The common constraints of working in resource limited settings including poor quality of the healthcare system paired with lack of local healthcare providers to lead and sustain ultrasound programs,44 a high turn-over of local supportive supervision,27 and unstable electricity43,54 were identified as barriers. These factors led to reduced frequency of POCUS examination, incomplete data log, loss of data, loss of ultrasound images and interpretations.50 Other barriers included training constraints and lack of an algorithm to guide POCUS screening and diagnosis.23 Face-to-face training sessions were reported to be expensive as costs for services of experienced trainers including travelling are high.24

Poor internet connectivity was reported to pose serious challenges to both implementing e-training and remote supervision as this translated into delays in exchanging POCUS information between POCUS operators and reviewers.21,43,54 Language barrier was also identified as a challenge to POCUS training.41

Discussion

This systematic review is the first to collate benefits and challenges of task shifting POCUS in primary healthcare in LMIC. Most studies included in this review report favourable effects of task shifting POCUS on clinical management at the primary care level in LMIC. Although the clinical value of POCUS is generally well established, collated evidence by this review needs to be appreciated with caution as studies originate from heterogenous settings and methodology is limited by uncontrolled study designs and constrained reference standards. More generally, there may be relevant publication bias with disappointing task shifting experiences less likely being published. Nevertheless, available literature indicates that task shifting for POCUS can make a difference in patient care in major medical fields of LMIC and highlights the pronounced potential of task shifting for POCUS for primary healthcare settings in LMIC where diagnostic imaging is otherwise barely accessible to large proportions of the population.

In LMIC, maternal mortality is the leading cause of death among women of childbearing age60 and 98% of the global neonatal mortality rate occur in LMIC.61 Antenatal sonographic examinations are integral to identifying high-risk pregnancies and for initiating time-sensitive management to reduce maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality. Consequently, the WHO recommends at least one ultrasound examination for pregnant women.62 Task shifting for obstetric POCUS provided by midwives, nurses or birth attendants at the primary care level may be essential to increase access to antenatal ultrasound for pregnant women in LMIC. Obstetric POCUS studies reported considerable impact of POCUS on management and clinical care of pregnant women including improved diagnosis of high-risk and complicated pregnancies, increased number of deliveries by skilled birth attendants, more deliveries in healthcare facilities and a reduction in maternal and neonatal mortalities.

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are on the rise and are the leading cause of mortality globally; over three quarters of CVD deaths occur in LMIC.63,64 Patients with heart diseases often present late with symptoms of heart failure that do not allow for distinguishing the underlying etiology of heart disease.65 In the recent past, increasing experience has become available on the benefits of cardiac POCUS by non-cardiologists to evaluate structural and functional heart pathology.66 The studies on cardiac POCUS showed the need for imaging capacity at the primary care and that task shifting for POCUS can partly fill this gap. A broader cardiac POCUS yet context tailored approach to identify most prevalent etiologies underlying heart failure and to guide clinical management in LMIC has been suggested65; its feasibility and diagnostic utility in routine care remain to be evaluated.

Road traffic trauma constitutes a global health challenge, particularly in LMIC where 90% of the world's fatalities on the roads occur.67 Multi-sector approach including improved post-crash care in the health sector is required in addressing challenges of road trauma victims.67 Focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST) is part of resuscitation of trauma patients in most high-level care settings and recommended by international panel consensus.68, 69, 70 FAST and eFAST (extended FAST (eFAST)) are highly accurate for identification of free fluid and pneumothorax.71,72 Comparatively, few publications on FAST application in LMIC were identified by this review. FAST in LMIC can play an important role in the management of trauma patients given the limited access to other cross-sectional imaging modalities. FAST in a pre-hospital setting allows targeted referral of trauma patients requiring surgery or transfusion.

In LMIC, lower respiratory tract infection is a leading infectious cause of morbidity and mortality particularly in children under 5 years.73 Chest ultrasound for the diagnosis of pneumonia has been reported as an imaging modality with sensitivity and specificity superior to chest-x-ray (CXR) for the diagnosis of childhood pneumonia.74 The substantial inter-rater agreement between POCUS operators and experts for lung consolidation and the almost perfect inter-rater agreement for viral lower respiratory tract infection encourages that locally trained lung POCUS can become a feasible tool to diagnose pneumonia and other pulmonary diseases in children under 5 years old in LMIC.52,53

POCUS for imaging pulmonary tuberculosis (PTB) has recently been subject of various studies,75 but only one study from Peru could be included in this review. The potential role of POCUS in screening and diagnosis of PTB in areas without access to CXR is also supported by other studies; a specific sonographic pattern of tuberculous lung infection is being discussed and could help differentiate between tuberculous and non-tuberculous pneumonia.76 Accurate diagnosis of tuberculosis (TB) in HIV-coinfected people is difficult. HIV patients have higher rates of extrapulmonary tuberculosis (EPTB), and the diagnosis of TB is often limited to clinical findings and imaging results, if imaging services are accessible. Focused assessment with sonography for HIV-associated TB (FASH)77 aims at detecting common EPTB manifestations and has become one of the most applied POCUS modules in settings with high TB/HIV burden.78,79 Of the many studies that evaluated EPTB-focused POCUS in adult and pediatric patients either as a diagnostic or treatment monitoring tool,80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85 only one met the inclusion criteria for this review; most studies were excluded because POCUS was performed by non-locals and at higher care levels. Included and excluded studies conclude that FASH can augment the clinician's ability to make a timely diagnosis of TB and monitor treatment response. Adoption of TB-focused POCUS and TB diagnostic algorithms can support its rollout in primary care setting, but to date data on its utility at primary care are limited.

Further, infectious diseases with public health relevance in endemic LMIC have been investigated for suitability for POCUS diagnostics. The study from Morocco on POCUS screening for cystic echinococcosis (CE)22 an infectious disease with a primarily imaging-based diagnosis,86 proved not only feasible and successful in identifying the disease, but is a good example that POCUS can also support the implementation of disease control activities. POCUS for the detection of urogenital schistosomiasis,49 POCUS to guide management of severe malaria,87 POCUS for early detection of vascular leakage in severe dengue88 and POCUS for visceral leishmaniasis89,90 have been piloted and discussed, but diagnostic studies from primary care settings in LMIC are not yet available.

An immediate impact of POCUS on patient management relates to appropriate use of anti-microbial medication. Henwood et al. reported that POCUS by local healthcare workers changed treatment modality in 42% of patients and this included administration of antibiotics.32 Comparably, a change in treatment following POCUS was observed by Chavez et al. for children diagnosed with pneumonia.59 In TB/HIV co-infected patients POCUS prompted live-saving initiation of antituberculosis treatment, addition of steroids in case of sonographically identified tuberculous pericarditis, and guided initiation of antiretroviral treatment.81 As mentioned above, POCUS shows also promise as a monitoring tool for treatment response in TB treatment with inadequately long persistence of sonographic findings indicating inadequate treatment dosing, intake, or resistant tuberculosis.83,91,92

Challenges relating to basic and continuous training were reported repeatedly. Particularly face-to face training was identified to be expensive. Most POCUS trainers were from overseas and travel related costs were high. Using e-learning methods have been suggested,43 however, these come with difficulties such as poor internet connectivity and extra costs in procuring internet data for streaming videos and downloading study material.93,94 The lack of stable internet connection and electricity to access study materials may lead to low motivation among healthcare workers to utilize e-learning platforms.95 Poor internet infrastructure can also hamper communication between POCUS operators and reviewers which was identified as the commonest method of supervision provided. The extremely broad range of length and type of training in the articles included highlights the need for standardized curricula; given the operator dependency of POCUS, under-training and lack of supervision can endanger patients’ safety.

Primary care settings in most LMIC often face power instability, and hot and humid climate conditions that can damage ultrasound devices. Inadequate know-how for maintenance service and lack of close technical service threatens continuous availability of functioning ultrasound devices. Many devices have been used for POCUS in LMIC but no comparative evaluation of device performance under LMIC conditions is available.

Most studies focused on clinical aspects relating to POCUS rather than key determinants of the task shifting approach. Ultrasound devices were not specifically studied for their suitability for task shifted use; user-friendliness including the possibility for setting presets targeted to the specific POCUS applications likely impacts feasibility and quality. Although most studies reported on the basic components of POCUS training it remains unclear to what extent POCUS training had been contextualized to the respective setting. Mention of infrastructure support needed to enable and sustain task shifting POCUS were discussed in relation to challenges with electricity and internet provision; further infrastructure aspects such as availability of ultrasound device servicing or arrangement of favorable scanning conditions (e.g., room darkening) may also play a role. None of the studies assessed cost-effectiveness of task shifting POCUS. Generating data on cost-effectiveness of task shifting for POCUS will, however, be crucial to guide implementation of task shifting for POCUS.

Within the available studies structures, quality management and supervision of task shifting for POCUS have largely been set up for the respective research and included overseas telemedicine components. For an independent and sustainable task shifting program pathways, local quality management and supervision are warranted. The empowerment of health care workers by gaining diagnostic capacities through task shifting for POCUS will likely increase satisfaction and recognition of their work and consecutively promote staff retention, a prerequisite for long term success of task shifting for POCUS.

In summary, seed evidence on task shifting for POCUS encourages further promotion of task shifted frontline POCUS use in LMIC. Establishing and disseminating successful and sustainable task shifting for POCUS programs needs a comprehensive strategy that addresses key aspects of a task shifting approach including definition of suitable technology, contextualized training, infrastructure support, adequate financing, quality management, longitudinal supervision, staff retention strategies, and outcome analysis. Determination of local disease burdens and needs assessment will allow conception of context adapted POCUS programs and POCUS curricula that could become integral part of local health education programs. Operational research on facilitators and barriers of POCUS implementation programs is needed to guide higher level decisions on integration in health sectors.

This review identified multiple studies that showed that shifting ultrasound tasks away from radiology centres to frontline bedside care is a feasible and effective strategy to change patient management at the primary care level in LMIC. Task shifting for POCUS thereby demonstrates that task shifting diagnostics to providers at lower-level facilities is impactful and translates to meaningful health outcomes. Technological advances and affordability of POCUS devices will continue to promote the diffusion of POCUS into frontline care, however, appreciation of POCUS as a diagnostic tool suitable for task shifting is warranted to deliberately enhance sustainable and qualitative implementation of task shifting for POCUS.

Data sharing statement

All data are already publicly available.

Funding

No funding was received.

Contributors

SKA and SB conceptualized the systematic review. SKA developed the data extraction tools with input from SB and CCH. SKA, LCR and CCH performed the initial abstract screen and subsequently full text screening. SKA and CCH extracted data from the included publication. SKA and LCR performed the risk of bias assessment. All named authors contributed to drafting, revising, and approving of the final manuscript.

Declaration of interests

Sabine Bélard is a board member (unpaid) for the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Tropenmedizin, Reisemedizin und Globale Gesundheit e.V.

Lisa C. Ruby report a Medizinernachwuchs.de travel grant and a Charité SEED grant for travel support for a research project in India.

The other authors have nothing to declare.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Bettina Utz for initial contribution in the idea stage of this research.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101333.

Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Okyere E., Mwanri L., Ward P. Is task-shifting a solution to the health workers’ shortage in Northern Ghana? PLoS One. 2017;12(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0174631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scheffler R., Bruckner T., Spetz J. The labour market for human resources for health in low-and middle-income countries. Hum Resour Health Obs. 2012;11 [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; 2016. Global Strategy on Human Resources for Health: Workforce 2030. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frija G., Blažić I., Frush D.P., et al. How to improve access to medical imaging in low- and middle-income countries ? eClinicalMedicine. 2021;38 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hricak H., Abdel-Wahab M., Atun R., et al. Medical imaging and nuclear medicine: a lancet oncology commission. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(4):e136–172. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30751-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Darzi A., Evans T. The global shortage of health workers-an opportunity to transform care. Lancet. 2016;388(10060):2576–2577. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32235-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2008. Task shifting: Global Recommendations and Guidelines. [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; 2007. Task Shifting: Rational Redistribution of Tasks Among Health Workforce Teams: Global Recommendations and Guidelines. [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization . OECD Publishing; 2018. Delivering Quality Health Services: A Global Imperative. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stolz L.A., Muruganandan K.M., Bisanzo M.C., et al. Point-of-care ultrasound education for non-physician clinicians in a resource-limited emergency department. Trop Med Int Health. 2015;20(8):1067–1072. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fleming K.A., Horton S., Wilson M.L., et al. 10315th. Vol. 398. Lancet; 2021 Nov 27. The lancet Commission on diagnostics: transforming access to diagnostics; pp. 1997–2050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moore C.L., Copel J.A. Point-of-care ultrasonography. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(8):749–757. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0909487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reynolds T.A., Amato S., Kulola I., Chen C.J., Mfinanga J., Sawe H.R. Impact of point-of-care ultrasound on clinical decision-making at an urban emergency department in Tanzania. PLoS One. 2018;13(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0194774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones T., Leng P. Clinical impact of point of care ultrasound (POCUS) consult service in a teaching hospital: effect on diagnoses and cost savings. Chest. 2016;149(4):170–179. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Page M.J., McKenzie J.E., Bossuyt P.M., et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Bank Country and Lending Groups. Country Classification. June 2020. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups Accessed 10 May 2021.

- 17.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; 1998. Training in Diagnostic Ultrasound: Essentials, Principles and Standards: Report of a WHO Study Group. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.The EndNote Team . EndNote X9 ed. Clarivate; Philadelphia, PA: 2013. Endnote. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ouzzani M., Hammady H., Fedorowicz Z., Elmagarmid A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):210. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Heart Lung and Blood Institue . National Heart Lung and Blood Institue; 2021. Study Quality Assessment Tools.https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools. Accessed 20 May. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adler D., Mgalula K., Price D., Taylor O. Introduction of a portable ultrasound unit into the health services of the Lugufu refugee camp, Kigoma District, Tanzania. Int J Emerg Med. 2008;1(4):261–266. doi: 10.1007/s12245-008-0074-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chebli H., Laamrani El Idrissi A., Benazzouz M., et al. Human cystic echinococcosis in Morocco: ultrasound screening in the Mid Atlas through an Italian-Moroccan partnership. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11(3):e0005384. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Colquhoun S.M., Carapetis J.R., Kado J.H., et al. Pilot study of nurse-led rheumatic heart disease echocardiography screening in Fiji-a novel approach in a resource-poor setting. Cardiol Young. 2013;23(4):546–552. doi: 10.1017/S1047951112001321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crispín Milart P.H., Diaz Molina C.A., Prieto-Egido I., Martínez-Fernández A. Use of a portable system with ultrasound and blood tests to improve prenatal controls in rural Guatemala. Reprod Health. 2016;13(1):110. doi: 10.1186/s12978-016-0237-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crispín Milart P.H., Prieto-Egido I., Díaz Molina C.A., Martínez-Fernández A. Detection of high-risk pregnancies in low-resource settings: a case study in Guatemala. Reprod Health. 2019;16(1):80. doi: 10.1186/s12978-019-0748-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dalmacion G.V., Reyles R.T., Habana A.E., et al. Handheld ultrasound to avert maternal and neonatal deaths in 2 regions of the Philippines: an iBuntis® intervention study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):32. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-1658-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Del Carpio M., Hugo Mercapide C., Salvitti J.C., et al. Early diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of cystic echinococcosis in remote rural areas in Patagonia: impact of ultrasound training of non-specialists. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6(1):e1444. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Engelman D., Kado J.H., Reményi B., et al. Screening for rheumatic heart disease: quality and agreement of focused cardiac ultrasound by briefly trained health workers. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2016;16:30. doi: 10.1186/s12872-016-0205-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fentress M., Ugarte-Gil C., Cervantes M., et al. Lung ultrasound findings compared with chest X-ray findings in known pulmonary tuberculosis patients: a cross-sectional study in Lima, Peru. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;103(5):1827–1833. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldenberg R.L., Nathan R.O., Swanson D., et al. Routine antenatal ultrasound in low- and middle-income countries: first look - a cluster randomised trial. BJOG. 2018;125(12):1591–1599. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.15287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Greenwold N., Wallace S., Prost A., Jauniaux E. Implementing an obstetric ultrasound training program in rural Africa. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2014;124(3):274–277. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2013.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Henwood P.C., Mackenzie D.C., Liteplo A.S., et al. Point-of-care ultrasound use, accuracy, and impact on clinical decision making in Rwanda hospitals. J Ultrasound Med. 2017;36(6):1189–1194. doi: 10.7863/ultra.16.05073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kahn D., Pool K.L., Phiri L., et al. Diagnostic utility and impact on clinical decision making of focused assessment with sonography for HIV-associated tuberculosis in malawi: a prospective cohort study. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2020;8(1):28–37. doi: 10.9745/GHSP-D-19-00251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kawooya M.G., Nathan R.O., Swanson J., et al. Impact of introducing routine antenatal ultrasound services on reproductive health indicators in Mpigi District, Central Uganda. Ultrasound Q. 2015;31(4):285–289. doi: 10.1097/RUQ.0000000000000142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kimberly H.H., Murray A., Mennicke M., et al. Focused maternal ultrasound by midwives in rural Zambia. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2010;36(8):1267–1272. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kirkpatrick J.N., Nguyen H.T.T., Doan L.D., et al. Focused cardiac ultrasound by nurses in rural Vietnam. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2018;31(10):1109–1115. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2018.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Levine A.C., Shah S., Noble V.E., Epino H. Ultrasound assessment of dehydration in children with gastroenteritis. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54(3):S91. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nascimento BR, Beaton AZ, Nunes MC, et al. PROVAR (Programa de RastreamentO da VAlvopatia Reumática) investigators. Echocardiographic prevalence of rheumatic heart disease in Brazilian schoolchildren: Data from the PROVAR study. Int J Cardiol. 2016 Sep 15;219:439-45. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Ploutz M., Lu J.C., Scheel J., et al. Handheld echocardiographic screening for rheumatic heart disease by non-experts. Heart. 2016;102(1):35–39. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Raza S., Frost E., Kwait D., et al. Training nonradiologist clinicians in diagnostic breast ultrasound in rural Rwanda: impact on knowledge and skills. J Am Coll Radiol. 2021;18(1):121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2020.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rominger A.H., Gomez G.A.A., Elliott P. The implementation of a longitudinal POCUS curriculum for physicians working at rural outpatient clinics in Chiapas, Mexico. Crit Ultrasound J. 2018;10(1):19. doi: 10.1186/s13089-018-0101-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sabatino V., Caramia M.R., Curatola A., et al. Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) in a remote area of Sierra Leone: impact on patient management and training program for community health officers. J Ultrasound. 2020;23(4):521–527. doi: 10.1007/s40477-019-00426-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shah S., Santos N., Kisa R., et al. Efficacy of an ultrasound training program for nurse midwives to assess high-risk conditions at labor triage in rural Uganda. PLoS One. 2020;15(6):e0235269. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0235269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shah S.P., Epino H., Bukhman G., et al. Impact of the introduction of ultrasound services in a limited resource setting: rural Rwanda 2008. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2008;9:4. doi: 10.1186/1472-698X-9-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shah S.P., Shah S.P., Fils-Aime R., et al. Focused cardiopulmonary ultrasound for assessment of dyspnea in a resource-limited setting. Crit Ultrasound J. 2016;8(1):7. doi: 10.1186/s13089-016-0043-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Swanson J.O., Kawooya M.G., Swanson D.L., Hippe D.S., Dungu-Matovu P., Nathan R. The diagnostic impact of limited, screening obstetric ultrasound when performed by midwives in rural Uganda. J Perinatol. 2014;34(7):508–512. doi: 10.1038/jp.2014.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vinayak S. Training midwives to perform basic obstetric pocus in rural areas using a tablet platform and mobile phone transmission technology. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2017;43:S84. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2017.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Terry B., Polan D.L., Nambaziira R., Mugisha J., Bisanzo M., Gaspari R. Rapid, remote education for point-of-care ultrasound among non-physician emergency care providers in a resource limited setting. Afr J Emerg Med. 2019 Sep;9(3):140–144. doi: 10.1016/j.afjem.2019.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Remppis J., Verheyden A., Bustinduy A.L., et al. Focused assessment with sonography for urinary schistosomiasis (FASUS)-pilot evaluation of a simple point-of-care ultrasound protocol and short training program for detecting urinary tract morbidity in highly endemic settings. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2020;114(1):38–48. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/trz101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Terry B., Polan D., Islam R., Mugisha J., Gaspari R., Bisanzo M. Rapid Internet-based review of point-of-care ultrasound studies at a remote hospital in Uganda. Ann Glob Health. 2014;80(3):222–223. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bonnard P., Boutouaba S., Diakhate I., Seck M., Dompnier J.P., Riveau G. Learning curve of vesico-urinary ultrasonography in Schistosoma haematobium infection with WHO practical guide: a "simple to learn" examination. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2011;85(6):1071–1074. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2011.11-0282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Salisbury T., Redfern A., Fletcher E.K., et al. Correct diagnosis of childhood pneumonia in public facilities in Tanzania: a randomised comparison of diagnostic methods. BMJ Open. 2021;11(5) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nadimpalli A, Tsung JW, Sanchez R, et al. Feasibility of Training Clinical Officers in Point-of-Care Ultrasound for Pediatric Respiratory Diseases in Aweil, South Sudan. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2019;101(3):689–695. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.18-0745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kolbe N., Killu K., Coba V., et al. Point of care ultrasound (POCUS) telemedicine project in rural Nicaragua and its impact on patient management. J Ultrasound. 2015;18(2):179–185. doi: 10.1007/s40477-014-0126-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nascimento B.R., Sable C., Nunes M.C.P., et al. Echocardiographic screening of pregnant women by non-physicians with remote interpretation in primary care. Fam Pract. 2021;38(3):225–230. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmaa115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Aklilu S., Bain C., Bansil P., et al. Evaluation of diagnostic ultrasound use in a breast cancer detection strategy in Northern Peru. PLoS One. 2021;16(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0252902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Voleti S., Adelbai M., Hovis I., et al. Novel handheld ultrasound technology to enhance non-expert screening for rheumatic heart disease in the Republic of Palau: a descriptive study. J Paediatr Child Health. 2021;57(7):1089–1095. doi: 10.1111/jpc.15409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Muhame R.M., Dragulescu A., Nadimpalli A., et al. Cardiac point of care ultrasound in resource limited settings to manage children with congenital and acquired heart disease. Cardiol Young. 2021;31(10):1–7. doi: 10.1017/S1047951121000834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chavez M.A., Naithani N., Gilman R.H., et al. Agreement between the world health organization algorithm and lung consolidation identified using point-of-care ultrasound for the diagnosis of childhood pneumonia by general practitioners. Lung. 2015;193(4):531–538. doi: 10.1007/s00408-015-9730-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Goldenberg R.L., McClure E.M. Maternal mortality. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205(4):293–295. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.07.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jehan I., Harris H., Salat S., et al. Neonatal mortality, risk factors and causes: a prospective population-based cohort study in urban Pakistan. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87(2):130–138. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.050963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Whitworth M., Bricker L., Mullan C. Ultrasound for fetal assessment in early pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015(7) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007058.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gaziano T.A. Reducing the growing burden of cardiovascular disease in the developing world. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26(1):13–24. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.1.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; 2021. Cardiovascular Diseases (CVDs)https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds Accessed 4 August 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Huson M.A.M., Kaminstein D., Kahn D., et al. Cardiac ultrasound in resource-limited settings (CURLS): towards a wider use of basic echo applications in Africa. Ultrasound J. 2019;11(1):34. doi: 10.1186/s13089-019-0149-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nelson B.P., Sanghvi A. Point-of-care cardiac ultrasound: feasibility of performance by noncardiologists. Glob Heart. 2013;8(4):293–297. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; 2021. Road Traffic Injuries.https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/road-traffic-injuries Accessed 1 September 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gaarder C., Kroepelien C.F., Loekke R., Hestnes M., Dormage J.B., Naess P.A. Ultrasound performed by radiologists-confirming the truth about FAST in trauma. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2009;67(2):323–329. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181a4ed27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Boulanger B.R., McLellan B.A., Brenneman F.D., Ochoa J., Kirkpatrick A.W. Prospective evidence of the superiority of a sonography-based algorithm in the assessment of blunt abdominal injury. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 1999;47(4):632. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199910000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Savatmongkorngul S., Wongwaisayawan S., Kaewlai R. Focused assessment with sonography for trauma: current perspectives. Open Access Emerg Med. 2017;9:57–62. doi: 10.2147/OAEM.S120145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nandipati K.C., Allamaneni S., Kakarla R., et al. Extended focused assessment with sonography for trauma (EFAST) in the diagnosis of pneumothorax: experience at a community based level I trauma center. Injury. 2011;42(5):511–514. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2010.01.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ianniello S., Di Giacomo V., Sessa B., Miele V. First-line sonographic diagnosis of pneumothorax in major trauma: accuracy of e-FAST and comparison with multidetector computed tomography. Radiol Med. 2014;119(9):674–680. doi: 10.1007/s11547-014-0384-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Troeger C., Forouzanfar M., Rao P.C., et al. Estimates of the global, regional, and national morbidity, mortality, and aetiologies of lower respiratory tract infections in 195 countries: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2015. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17(11):1133–1161. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30396-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Heuvelings C.C., Bélard S., Familusi M.A., Spijker R., Grobusch M.P., Zar H.J. Chest ultrasound for the diagnosis of paediatric pulmonary diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy. Br Med Bull. 2019;129(1):35–51. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldy041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Heuvelings C.C., Bélard S., Andronikou S., Jamieson-Luff N., Grobusch M.P., Zar H.J. Chest ultrasound findings in children with suspected pulmonary tuberculosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2019;54(4):463–470. doi: 10.1002/ppul.24230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Agostinis P., Copetti R., Lapini L., Badona Monteiro G., N'Deque A., Baritussio A. Chest ultrasound findings in pulmonary tuberculosis. Trop Dr. 2017;47(4):320–328. doi: 10.1177/0049475517709633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Heller T., Wallrauch C., Goblirsch S., Brunetti E. Focused assessment with sonography for HIV-associated tuberculosis (FASH): a short protocol and a pictorial review. Crit Ultrasound J. 2012;4(1):21. doi: 10.1186/2036-7902-4-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.van Hoving D.J., Lamprecht H.H., Stander M., et al. Adequacy of the emergency point-of-care ultrasound core curriculum for the local burden of disease in South Africa. Emerg Med J. 2013;30(4):312–315. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2012-201358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Heller T., Mtemang'ombe E.A., Huson M.A., et al. Ultrasound for patients in a high HIV/tuberculosis prevalence setting: a needs assessment and review of focused applications for Sub-Saharan Africa. Int J Infect Dis. 2017;56:229–236. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2016.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Heller T., Wallrauch C., Lessells R.J., Goblirsch S., Brunetti E. Short course for focused assessment with sonography for human immunodeficiency virus/tuberculosis: preliminary results in a rural setting in South Africa with high prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus and tuberculosis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;82(3):512–515. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Heller T., Goblirsch S., Wallrauch C., Lessells R., Brunetti E. Abdominal tuberculosis: sonographic diagnosis and treatment response in HIV-positive adults in rural South Africa. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14(6):e108–e112. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2009.11.030. Suppl 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Heller T., Goblirsch S., Bahlas S., et al. Diagnostic value of FASH ultrasound and chest X-ray in HIV-co-infected patients with abdominal tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2013;17(3):342–344. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.12.0679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bélard S., Heuvelings C.C., Banderker E., et al. Utility of point-of-care ultrasound in children with pulmonary tuberculosis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2018;37(7):637–642. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bobbio F., Di Gennaro F., Marotta C., et al. Focused ultrasound to diagnose HIV-associated tuberculosis (FASH) in the extremely resource-limited setting of South Sudan: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(4) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Weber S.F., Saravu K., Heller T., et al. Point-of-care ultrasound for extrapulmonary tuberculosis in india: a prospective cohort study in HIV-Positive and HIV-negative presumptive tuberculosis patients. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2018;98(1):266–273. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.17-0486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Group W.I.W. International classification of ultrasound images in cystic echinococcosis for application in clinical and field epidemiological settings. Acta Trop. 2003;85(2):253–261. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(02)00223-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Pugliese C.M., Adegbite B.R., Edoa J.R., et al. Point-of-care ultrasound to assess volume status and pulmonary oedema in malaria patients. Infection. 2022;50(1):65–82. doi: 10.1007/s15010-021-01637-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Dewan N., Zuluaga D., Osorio L., Krienke M.E., Bakker C., Kirsch J. Ultrasound in dengue: a scoping review. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2021;104(3):826–835. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mohammed R., Gebrewold Y., Schuster A., et al. Abdominal ultrasound in the diagnostic work-up of visceral leishmaniasis and for detection of complications of spleen aspiration. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0009107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bélard S., Stratta E., Zhao A., et al. Sonographic findings in visceral leishmaniasis-a narrative review. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2021;39 doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Heller T., Wallrauch C., Brunetti E., Giordani M.T. Changes of FASH ultrasound findings in TB-HIV patients during anti-tuberculosis treatment. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2014;18(7):837–839. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.13.0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Weber S.F., Weber M., Tenbrock K., Bélard S. Call for ultrasound in paediatric tuberculosis work-up: a case report from Germany. J Paediatr Child Health. 2020;56(6):964–966. doi: 10.1111/jpc.14721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Nguyen Q., Nguyen P.T., Huynh V.D.B., Nguyen L.T. Application Chang's extent analysis method for ranking barriers in the e-learning model based on multi-stakeholder decision making. Univers J Educ Res. 2020;8(5):1759–1766. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zalat M.M., Hamed M.S., Bolbol S.A. The experiences, challenges, and acceptance of e-learning as a tool for teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic among university medical staff. PLoS One. 2021;16(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0248758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Naresh B., Reddy B.S. Challenges and opportunity of E-learning in developed and developing countries-a review. Int J Emerg Res Manag Technol. 2015;4(6):259–262. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.