Abstract

This study assesses how a limited supply of monoclonal antibody therapy was allocated to patients at highest risk of severe disease among a population of fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries with a new COVID-19 diagnosis or confirmed exposure between November 2020 and August 2021.

Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) are highly effective in treating mild to moderate COVID-19 among nonhospitalized patients.1 Given limited supply, federal guidelines prioritize patients at higher risk of progression to hospitalization or mortality from COVID-19, with risk factors including age and comorbid conditions.2,3 Antibodies were initially allocated to states by the federal government,4 then distributed through suppliers in 2021.5 We assessed how the limited supply of mAb therapy was allocated to patients at highest risk of severe disease.

Methods

We used a 100% sample of outpatient, emergency department, and laboratory claims for fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries with a new COVID-19 diagnosis or confirmed exposure between November 2020 (first month of mAb availability) and August 2021. Beneficiaries hospitalized or deceased within 7 days of COVID-19 diagnosis, who were less likely to have mild to moderate disease and be eligible for mAb therapy, were excluded. We identified mAb infusions with Current Procedural Terminology codes (Q0239, Q0243-7, M0239, M0243-8) and classified COVID-19 diagnosis using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision codes U07.1, B97.29, and Z20.828 (exposure to confirmed COVID-19). Among nonhospitalized patients with a COVID-19 diagnosis, we compared rates of mAb receipt by age, sex, race and ethnicity, Medicaid eligibility, region, number of chronic conditions, reason for Medicare eligibility, and selected conditions associated with severe COVID-19. We performed multivariable logistic regression to estimate odds ratios, with statistical significance defined as a 95% confidence interval that does not include 1.0, for receipt of mAbs controlling for the patient characteristics listed above. We also compared rates of mAb treatment by state. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc). This study was approved and informed consent was waived by the Dartmouth College institutional review board.

Results

From November 2020 to August 2021, 1 902 914 fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries had a diagnosis of COVID-19 and were not hospitalized or deceased within 7 days of diagnosis. Of these, 7.2% received mAb therapy (Table). The likelihood of receiving mAb therapy was higher among those with fewer chronic conditions (23.2% of beneficiaries with 0 chronic conditions vs 6.3%, 6.0%, and 4.7% with 1-3, 4-5, and ≥6 chronic conditions, respectively; adjusted odds ratio, 7.43 [95% CI, 7.21-7.66] for 0 vs ≥6). Patients receiving treatment were also less likely to be Black (6.2% vs 7.4% of non-Hispanic white patients; adjusted odds ratio, 0.77 [95% CI, 0.75-0.79]) or dually enrolled in Medicaid (4.6% vs 8.1%, adjusted odds ratio 0.74 [95% CI, 0.72-0.75]). Unadjusted mAb therapy rates were lower for older beneficiaries (6.7% of ≥85-year-old vs 7.8% of 65- to 74-year-old beneficiaries), but after adjustment, being aged 85 years or older was associated with higher odds of mAb therapy (adjusted odds ratio, 1.42 [95% CI, 1.39-1.45]).

Table. Characteristics of Fee-for-Service Medicare Beneficiaries Receiving mAb Therapya.

| Characteristics | COVID-19 diagnosis/exposure, No. | Receiving mAbs, % | Adjusted OR of receiving mAbs (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 1 902 914 | 7.2 | |

| Age at first COVID-19 diagnosis, y | |||

| ≤64 | 305 163 | 4.9 | 0.67 (0.62-0.73) |

| 65-74 | 885 838 | 7.8 | 1 [Reference] |

| 75-84 | 501 432 | 7.8 | 1.30 (1.28-1.32) |

| ≥85 | 210 481 | 6.7 | 1.42 (1.39-1.45) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 1 072 140 | 7.1 | 1 [Reference] |

| Male | 830 774 | 7.3 | 0.98 (0.97-1.00) |

| Race and ethnicityb | |||

| Black, non-Hispanic | 160 252 | 6.2 | 0.77 (0.75-0.79) |

| Hispanic | 123 998 | 6.7 | 1.16 (1.13-1.20) |

| White, non-Hispanic | 1 517 271 | 7.4 | 1 [Reference] |

| Other | 101 393 | 5.9 | 0.92 (0.90-0.95) |

| Medicaid | |||

| No | 1 402 371 | 8.1 | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 500 543 | 4.6 | 0.74 (0.72-0.75) |

| Region | |||

| Northeast | 374 960 | 5.9 | 0.50 (0.49-0.50) |

| Midwest | 516 424 | 6.5 | 0.51 (0.51-0.52) |

| South | 674 007 | 10.6 | 1 [Reference] |

| West | 329 249 | 2.9 | 0.22 (0.21-0.22) |

| Territories | 8274 | 3.1 | 0.05 (0.05-0.06) |

| Rural (non-MSA) | |||

| No | 1 319 013 | 7.0 | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 583 901 | 7.8 | 0.92 (0.91-0.93) |

| No. of chronic conditions | |||

| 0 | 178 064 | 23.2 | 7.43 (7.21-7.66) |

| 1-3 | 567 892 | 6.3 | 1.51 (1.48-1.55) |

| 4-5 | 448 857 | 6.0 | 1.30 (1.27-1.33) |

| ≥6 | 708 101 | 4.7 | 1 [Reference] |

| Current reason for eligibility | |||

| Aged ≥65 | 1 611 157 | 7.6 | 1 [Reference] |

| Disability | 282 393 | 4.9 | 0.95 (0.88-1.03) |

| ESRD | 7457 | 5.0 | 1.40 (1.23-1.60) |

| Both disability and ESRD | 1907 | 4.8 | 1.36 (1.08-1.71) |

| Alzheimer and related dementias | |||

| No | 1 638 509 | 7.8 | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 264 405 | 3.7 | 0.66 (0.65-0.68) |

| Chronic kidney disease | |||

| No | 1 304 033 | 8.2 | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 598 881 | 5.1 | 1.01 (1.00-1.03) |

| COPD | |||

| No | 1 613 857 | 7.7 | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 289 057 | 4.2 | 0.82 (0.81-0.84) |

| Heart failure | |||

| No | 1 542 703 | 7.8 | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 360 211 | 4.7 | 0.93 (0.92-0.95) |

| Diabetes | |||

| No | 1 305 110 | 7.8 | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 597 804 | 5.8 | 1.33 (1.31-1.35) |

| Ischemic heart disease | |||

| No | 1 254 879 | 8.0 | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 648 035 | 5.6 | 1.12 (1.10-1.13) |

| Stroke/transient ischemic attack | |||

| No | 1 805 635 | 7.4 | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 97 279 | 3.8 | 0.80 (0.77-0.83) |

Abbreviations: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; mAb, monoclonal antibody; MSA, metropolitan statistical area; OR, odds ratio.

See Methods section of text for codes used to identify mAb infusions and COVID-19 diagnoses. Patients hospitalized or deceased within 7 days of COVID-19 diagnosis were excluded. Data include patients from 50 states, the District of Columbia, and US territories except those residing in Guam or the Marshall Islands on January 1, 2021 (excluded because all beneficiaries in these territories either received or did not receive mAb therapy). Age data are age at time of COVID-19 diagnosis. Chronic conditions listed are those recognized as risk factors for severe COVID-19 outcomes. Model controlled for variables listed as well as state indicators and additional chronic conditions. The full list of 27 chronic conditions included acute myocardial infarction, Alzheimer disease and related disorders of senile dementia, atrial fibrillation, cataracts, chronic kidney disease, COPD, heart failure, diabetes, glaucoma, hip/pelvic fracture, ischemic heart disease, depression, osteoporosis, rheumatoid arthritis/osteoarthritis, stroke/transient ischemic attack, breast cancer, colorectal cancer, prostate cancer, lung cancer, endometrial cancer, anemia, asthma, hyperlipidemia, benign prostatic hyperplasia, hypertension, and acquired hypothyroidism.

Beneficiary race and ethnicity were defined using the Research Triangle Institute classification available in the Medicare Master Beneficiary Summary File. The “other” category includes Asian and Pacific Islander, American Indian and Alaska Native, and beneficiaries coded as “other” or “unknown” in the beneficiary race code. Race and ethnicity were included in this analysis to assess differences in rate of mAb receipt across racial and ethnic groups.

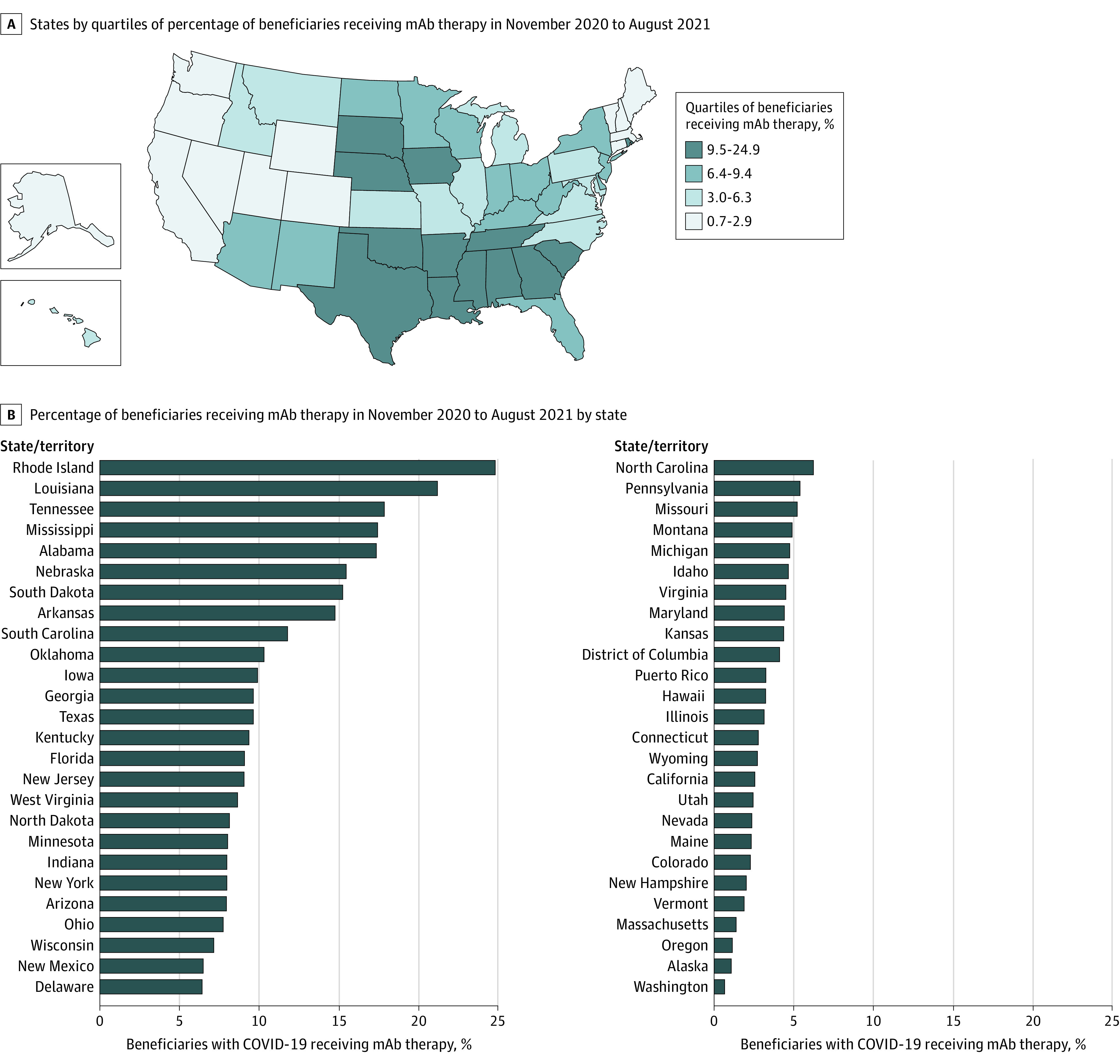

Rhode Island and Louisiana administered mAb therapy to the highest proportion of nonhospitalized patients with COVID-19 (24.9% and 21.2%), while Alaska and Washington administered mAb therapy to the lowest proportion (1.1% and 0.7%) (Figure). States in the South had the highest rates of mAb therapy (10.6% of beneficiaries) vs the lowest rates in states in the West (2.9%) (Table).

Figure. Fee-for-Service Medicare Beneficiaries With COVID-19 Receiving mAb Therapy by State.

mAb indicates monoclonal antibody. Proportion of Medicare beneficiaries with a documented COVID-19 diagnosis or exposure to a confirmed case of COVID-19 receiving mAb therapy between November 2020 and August 2021. Patients hospitalized or deceased within 7 days of COVID-19 diagnosis were excluded.

Discussion

Among nonhospitalized Medicare beneficiaries with a COVID-19 diagnosis between November 2020 and August 2021, only 7.2% received mAb therapy. In many cases, patients at the highest risk of severe disease were the least likely to receive mAb therapy. There was also extreme variation geographically.

These findings suggest that use of mAb therapy for mild to moderate COVID-19 failed to reach the highest-risk patients across and within states. There are multiple potential explanations for these results. Higher-risk patients may have had difficulty navigating the multiple steps needed to receive mAbs, from receipt of a timely COVID-19 diagnosis to referral and scheduling an infusion within 10 days. In addition, mAb supply may have been low or less used by clinicians in some regions of the country. Policy that explicitly prioritizes high-risk patients may be needed for equitable distribution of COVID-19 therapeutics.

Limitations of this analysis include the use of Medicare fee-for-service data, which may not generalize to other populations, including Medicare Advantage enrollees. This analysis did not account for patient vaccination status or observed disease severity, which could influence clinicians’ choice to give mAb therapy.

Section Editors: Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editor; Kristin Walter, MD, Associate Editor.

References

- 1.Gottlieb RL, Nirula A, Chen P, et al. Effect of bamlanivimab as monotherapy or in combination with etesevimab on viral load in patients with mild to moderate COVID-19: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021;325(7):632-644. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.0202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Institutes of Health . Therapeutic management of nonhospitalized adults with COVID-19. In: Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Treatment Guidelines. Updated October 19, 2021. Accessed November 5, 2021. https://files.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/guidelines/archive/covid19treatmentguidelines-10-27-2021.pdf [PubMed]

- 3.National Institutes of Health . Updated COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel’s statement on the prioritization of anti-SARS-CoV-2 monoclonal antibodies for the treatment or prevention of SARS-CoV-2 infection when there are logistical or supply constraints. Updated October 7, 2021. Accessed November 5, 2021. https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/therapies/updated-statement-on-the-prioritization-of-anti-sars-cov-2-mabs/

- 4.Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response . Update: distribution and administration of COVID-19 therapeutics. Updated September 15, 2021. Accessed November 5, 2021. https://www.phe.gov/emergency/events/COVID19/investigation-MCM/Bamlanivimab-etesevimab/Pages/Update-13Sept21.aspx

- 5.US Department of Health and Human Services . HHS announces state/territory-coordinated distribution system for monoclonal antibody therapeutics. Updated September 13, 2021. Accessed November 5, 2021. https://www.phe.gov/emergency/events/COVID19/investigation-MCM/Bamlanivimab-etesevimab/Pages/Update-13Sept21.aspx