Abstract

Researchers and research participants increasingly support returning clinically actionable genetic research findings to participants, but researchers may lack the skills and resources to do so. In response, a genetic counsellor-led program to facilitate the return of clinically actionable findings to research participants was developed to fill the identified gap in research practice and meet Australian research guidelines. A steering committee of experts reviewed relevant published literature and liaised with researchers, research participants and clinicians to determine the scope of the program, as well as the structure, protocols and infrastructure. A program called My Research Results (MyRR) was developed, staffed by genetic counsellors with input from the steering committee, infrastructure services and a genomic advisory committee. MyRR is available to Human Research Ethics Committee approved studies Australia-wide and comprises genetic counselling services to notify research participants of clinically actionable research findings, support for researchers with developing an ethical strategy for managing research findings and an online information platform. The results notification strategy is an evidence-based two-step model, which has been successfully used in other Australian studies. MyRR is a translational program supporting researchers and research participants to access clinically actionable research findings.

Subject terms: Genetics research, Genetic counselling, Preventive medicine

Background

Between 1 and 3% of participants in large population-based studies will have a pathogenic or likely pathogenic variant in a clinically actionable gene identified by research genomic testing, here referred to as clinically actionable findings [1, 2]. As the cost of genomic testing decreases, there has been a corresponding increase in population-based genomic studies and an imperative to develop strategies for managing these clinically actionable findings. For example, Australian research guidelines mandate that researchers undertaking genomic research have an ethically defensible plan for managing such findings, although little guidance is provided beyond this [3].

There is broad agreement among research participants and researchers that returning clinically actionable findings is desirable [4–7]. Participants report a preference to receive results from genomic research, and the available literature suggests that participants cope well with receiving research results, particularly when provided with appropriate support and follow-up care [1, 5, 8]. Researchers also endorse the return of clinically actionable findings, such as those outlined in the ACMG list of reportable genes [9], and generally agree that offering clinically actionable findings respects participant preferences, and can improve health outcomes [7, 9, 10].

This impetus for returning clinically actionable findings is further evidenced by literature recommending systematic methods for their return, led by professionals with relevant skills and expertise, such as genetic counsellors [4, 6, 7, 11, 12]. In response, mechanisms for returning secondary genomic findings have been established in the USA, including a secondary findings service that provides identification of clinically actionable findings and genetic counselling services to intramural researchers [11, 13]. An Australian protocol has also been developed to manage additional findings in the diagnostic setting [12]. However, outside these settings, processes for returning research results are largely ad hoc and researchers have reported significant challenges when returning clinically actionable findings to participants, including a lack of expertise, resources and infrastructure [5–7, 10]. Therefore, there are still widespread unmet needs among researchers with regard to managing clinically actionable findings. This paper outlines the development of My Research Results (MyRR), an Australian genetic counselling program designed to fill this gap.

Methods

Scoping

The primary aim and scope of the program is to support Australian Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) approved research studies to return clinically actionable findings to research participants. Activities within the scope of this program include assisting researchers to develop an ethically defensible plan for managing clinically actionable findings and provision of genetic counselling services and resources to facilitate return of these findings to research participants. Identification and confirmatory testing of clinically actionable findings were outside the scope of the program, given logistical barriers to offering these services nationally. These roles are already appropriately filled by researchers and clinical genetics services respectively.

Steering committee

A steering committee was established to guide the development of the program, led by genetic counsellors who have experience returning research results and who are responsible for running the program. The steering committee included genetic and psychosocial researchers, education specialists, clinical geneticists and a consumer representative. A broader network of expertise supported the steering committee, including information technology and data security specialists and a genomics advisory committee.

Design and development

The design and development of the program was iterative and based on published literature, the steering committee’s expertise and the results of stakeholder engagement activities. Key considerations for the steering committee included the accessibility of the service, security and future scalability. The steering committee met regularly to assess priorities, review progress and plan future activities, as well as communicating by email. The role of the steering committee was to determine the services and resources offered, protocols and engagement plan for the program.

Stakeholder engagement is key to developing a service that meets HREC requirements and the needs of research participants, researchers and clinical genetics services [14]. A range of engagement and continuous improvement activities informed development and are ongoing to enhance the program, including consultation, focus groups and cost effectiveness studies. For example, research collaborators and representatives from clinical genetics services were consulted to ensure the service meets their needs and fits with current practice. Supplementary resources offered to inform and support participants will be based on the results of focus groups with individuals enrolled in research projects.

An evaluation and quality improvement framework has been developed based on service inputs, activities, outputs and outcomes articulated in the service program logic model. The reach, efficiency and effectiveness of the service will be reviewed annually and will include data collected both from research teams who engage the service and research participants who receive results through the service.

Results

The resulting program, called MyRR, is led by genetic counsellors and supports researchers to develop and implement an ethically defensible plan for managing genomic research results, consistent with national research guidelines [3]. Genetic counsellors are the key contact point for researchers and participants, with an online platform hosting resources to support the service. The program is based at a leading Australian medical research institute, and is available to researchers and participants Australia-wide (launched February 2021; http://www.myresearchresults.org.au).

Infrastructure

Given services are offered Australia-wide, MyRR utilises telephone genetic counselling and online technologies to provide accessible services. A service agreement is used to formalise services provided by MyRR to researchers. A secure online platform supports genetic counsellors’ data management and interactions with participants and clinical genetics services. Online information and resources for researchers and participants support the genetic counselling service.

Clinical actionability and Genomics Advisory Committee

The MyRR service facilitates return of adult-onset, clinically actionable findings to research participants. Clinically actionable findings have been defined as pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants based on ACMG/AMP guidelines in genes with well-established management guidelines [15, 16]. Research results are identified by the research team according to their local protocols. However, a Genomics Advisory Committee provides clinical oversight of MyRR and ensures that results returned through MyRR meet these criteria for clinical actionability. The advisory committee members include genetic counsellors, clinical geneticists, a genomic pathologist and ad hoc experts as required. The advisory committee provides guidance on clinically actionable genes endorsed for return as a guide for researchers, using the ACMG list of reportable genes, with scope to report on other genes for which national guidelines and publicly-funded risk management strategies are available [9, 17]. The advisory committee also provides clinical case review of individual variants and challenging cases.

Genetic counselling and notification strategy

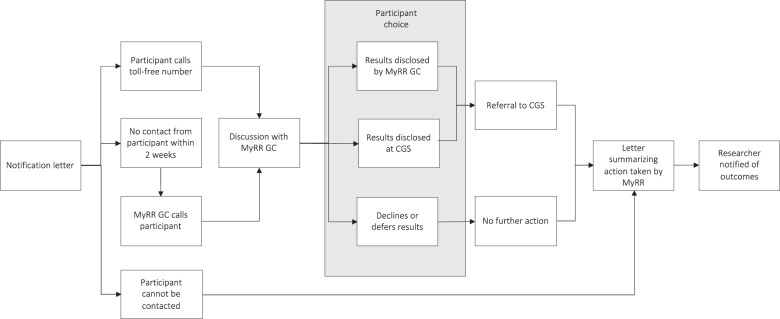

Appropriate consent to receive clinically actionable findings is required prior to notifying participants of results. Eliciting consent and acting in accordance with the consent decisions of participants and the study’s ethics approval is the responsibility of the researcher, with support available from MyRR genetic counsellors. Support needs vary, depending on the study context and procedures, but can include study document development, training in research genomic consent discussions, access to MyRR online resources and telephone access to genetic counsellors for participants if required. Participants typically consent to receipt of clinically actionable findings at enrolment into the research study, although pre-existing studies have retrospectively consented participants to receive results. The MyRR notification strategy is based on the current evidence-based two-step system used in multiple Australian research studies (Fig. 1), which has been shown to support research participants and reduce health system barriers to uptake of clinically actionable findings [18, 19].

Fig. 1. A flowchart of participant pathways through the MyRR two-step notification process.

Clinical genetics service (CGS), Genetic counsellor (GC), My Research Results (MyRR).

Once clinically actionable findings have been identified and approved for return, research participants are notified in writing that results are available by the researcher. The specific result is not provided in this initial notification (Box 1) [19]. The notification letter provides the contact details for the MyRR genetic counselling service and encourages the participant to contact the service for more information. If participants do not make contact, a genetic counsellor contacts them by phone within 2 weeks. The purpose of MyRR genetic counselling is to provide research participants with information to support an informed choice regarding receipt of the clinically actionable findings and facilitate further action as appropriate.

Participants have the option to receive their results, decline, or defer receiving their results. The potential pathways for participants are shown in Fig. 1. Participants who receive their results are provided with information regarding the variant identified and potential implications for their health and referred to their local clinical genetics service for diagnostic confirmatory testing and ongoing risk management. In Australia, the cost of confirmatory testing and appointments at public clinical genetics services are covered by a publicly-funded universal health care insurance scheme for Australian residents. MyRR genetic counsellors provide ongoing support to participants to facilitate access to clinical services, communicating with participants, clinical genetic services and other health professionals as required.

Participants who decline or defer results can change their mind in the future, as their information is held securely by MyRR, even if the research study is closed. Non-responders receive a letter summarising the contact attempts and are invited to contact MyRR in the future. Researchers are notified of the outcome of the notification process as part of standard aggregate reporting.

Box 1: Example notification letter.

From Rowley et al. [19].

When you gave your consent for us to use your DNA in genetic research, we let you know that if a research result relevant to your health was found, we would write to you and ask if you would like to learn more about that health information.

We now have some results from the research that may have relevance for your health and/or your family. If you would like to learn more, please contact [Genetic Counsellor], a member of the genetic counselling team at [Institution], either by telephone on [number] or by email at [email]. We will provide expert advisors to explain the nature of this health information and make sure you understand all the benefits and risks of learning more about this information.

Discussion

MyRR is a genetic counsellor-led program designed to facilitate the return of clinically actionable findings identified through research, which fills a current gap in Australian genomic research practice. The proposed model has been developed with input from participants, researchers and clinicians, with the aim of meeting the needs of each stakeholder group. The development was guided by a multidisciplinary team with relevant and diverse expertise, specifically to address Australian research guidelines.

A national service available to HREC approved studies that facilitates return of results will make clinically actionable findings from research testing available to more Australian research participants, consistent with their preferences and expectations [5]. Particularly given the cost of confirmatory testing and clinical care is publicly-funded. A national evidence-based service will also provide a consistent standard of care, and reduce reliance on ad hoc systems [11]. Promotion of consent discussions regarding research results is a key component of the service, as not all individuals wish to receive genetic information from research [5, 7, 10]. Also critical is providing timely information and support to participants receiving results, as receiving results can invoke distress and uncertainty, particularly while waiting for confirmatory testing [18, 20]. There is also evidence that individuals avoid acting on results or do not attend genetic counselling because of a lack of information or perceived cost or logistical issues [21, 22]. The model described here aims to remove these barriers to access, as well as remove geographical barriers by providing services through telephone counselling.

Researchers broadly agree with returning clinically actionable findings, but have reported a lack of expertise, resources and infrastructure to do so [6, 10]. With funding and regulatory bodies placing greater emphasis on an ethically defensible plan for managing clinically actionable findings [3], the MyRR model provides a useful template for researchers to return results to participants. The program can also provide the resources and infrastructure needed to return results to participants with appropriate clinical oversight and support. This then enables researchers to focus on their primary research aims and avoid significant time spent on and, in some cases, distress caused by the secondary task of returning and following up clinically actionable findings [10, 11].

While MyRR is primarily focused on connecting research participants with research results, clinical genetics services are another key stakeholder. Returning research results can enable the identification of at-risk individuals who would not otherwise have been offered genetic testing [19]. Genetics health professionals typically support the return of clinically actionable findings, despite concerns regarding the workforce impact of these endeavours [7]. A goal of this centralised model and engagement with the clinical community is to minimise the impact of returning clinically actionable research findings on overstretched public health systems. An additional benefit of providing results with genetic counselling through MyRR is improved quality of referrals and genetic counselling appointments regarding research findings, given evidence of better outcomes from genetic counselling when patients know what to expect [22].

Challenges and limitations

While the authors believe this program represents a beneficial evidence-based model for managing clinically actionable findings in the Australian setting, it is not without challenges and limitations. Developing the infrastructure, ensuring appropriate data security and engaging appropriate clinical oversight has been a significant and iterative undertaking. Setting up such a comprehensive program is an ongoing project, but the challenges also present opportunities for improvement and growth. A limitation of this model is the possibility of returning erroneous results, given research results are not confirmed on an independent sample prior to return. However, this is consistent with current Australian research practice, with confirmatory testing completed by clinical genetics services using public health funds in a diagnostic setting. Participants with no reportable findings will also not receive any results under this model. This raises the importance of appropriate consent, including discussion of the limitations of research testing.

Conclusion

MyRR is a translational program to facilitate the return of clinically actionable genomic research findings, with potential to fill an important gap for Australian research studies and deliver health benefits to research participants. The centralised, scalable model can be adapted for other settings, such as population screening, and will enable the platform to change and grow in alignment with stakeholder preferences, resources and best practice. Future work will focus on growing, evaluating and improving MyRR, to ensure the platform meets stakeholders’ needs now and in the future.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of the Genomics Advisory Committee Members: A/Prof Kathy Tucker, A/Prof Jodie Ingles, Prof Leslie Burnett, Prof Ingrid Winship, Dr Lesley Andrews, Ms Ebony Richardson and Dr Thomas Ohnesorg. The authors would also like to acknowledge the contribution of Simone Busija and Radhika Rajkumar to the development of this platform. This work was supported by The Kinghorn Foundation.

Author contributions

AM, AP, AW, BT, M-AY and MB contributed to the conceptualisation and design of the program. AP, AW, BT and M-AY were responsible for project administration. AW drafted the paper and AM, AP, AW, BT, M-AY and MB reviewed and edited the paper.

Funding

This work was supported by The Kinghorn Foundation.

Data availability

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This research did not involve human subjects, material or data; therefore ethics approval was not required.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hart MR, Biesecker BB, Blout CL, Christensen KD, Amendola LM, Bergstrom KL, et al. Secondary findings from clinical genomic sequencing: prevalence, patient perspectives, family history assessment, and health-care costs from a multisite study. Genet Med. 2019;21:1100–10. doi: 10.1038/s41436-018-0308-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.eMERGE Clinical Annotation Working Group. Frequency of genomic secondary findings among 21,915 eMERGE network participants. Genet Med. 2020;22:1470–7. doi: 10.1038/s41436-020-0810-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The National Health and Medical Research Council, the Australian Research Council, Universities Australia. National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research. Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra: National Health and Medical Research Council; 2007 (Updated 2018).

- 4.Forrest LE, Young MA. Clinically significant germline mutations in cancer-causing genes identified through research studies should be offered to research participants by genetic counselors. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:898–901. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.60.9388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henrikson NB, Scrol A, Leppig KA, Ralston JD, Larson EB, Jarvik GP. Preferences of biobank participants for receiving actionable genomic test results: results of a recontacting study. Genet Med. 2021;23:1163–6. doi: 10.1038/s41436-021-01111-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lázaro-Muñoz G, Torgerson L, Smith HS, Pereira S. Perceptions of best practices for return of results in an international survey of psychiatric genetics researchers. Eur J Hum Genet. 2021;29:231–40. doi: 10.1038/s41431-020-00738-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mackley MP, Fletcher B, Parker M, Watkins H, Ormondroyd E. Stakeholder views on secondary findings in whole-genome and whole-exome sequencing: a systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Genet Med. 2017;19:283–93. doi: 10.1038/gim.2016.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sapp JC, Johnston JJ, Driscoll K, Heidlebaugh AR, Miren Sagardia A, Dogbe DN, et al. Evaluation of recipients of positive and negative secondary findings evaluations in a hybrid CLIA-research sequencing pilot. Am J Hum Genet. 2018;103:358–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller DT, Lee K, Chung WK, Gordon AS, Herman GE, Klein TE, et al. ACMG SF v3.0 list for reporting of secondary findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing: a policy statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) Genet Med. 2021;23:1381–90. doi: 10.1038/s41436-021-01172-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Halverson CME, Bland ST, Leppig KA, Marasa M, Myers M, Rasouly HM, et al. Ethical conflicts in translational genetic research: lessons learned from the eMERGE-III experience. Genet Med. 2020;22:1667–72. doi: 10.1038/s41436-020-0863-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Darnell AJ, Austin H, Bluemke DA, Cannon RO, III, Fischbeck K, Gahl W, et al. A clinical service to support the return of secondary genomic findings in human research. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;98:435–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martyn M, Kanga-Parabia A, Lynch E, James PA, Macciocca I, Trainer AH, et al. A novel approach to offering additional genomic findings-A protocol to test a two-step approach in the healthcare system. J Genet Couns. 2019;28:388–97. doi: 10.1002/jgc4.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwartz MLB, McCormick CZ, Lazzeri AL, Lindbuchler DM, Hallquist MLG, Manickam K, et al. A model for genome-first care: returning secondary genomic findings to participants and their healthcare providers in a large research cohort. Am J Hum Genet. 2018;103:328–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hartzler A, McCarty CA, Rasmussen LV, Williams MS, Brilliant M, Bowton EA, et al. Stakeholder engagement: a key component of integrating genomic information into electronic health records. Genet Med. 2013;15:792–801. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17:405–23. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller DT, Lee K, Gordon AS, Amendola LM, Adelman K, Bale SJ, et al. Recommendations for reporting of secondary findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing, 2021 update: a policy statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) Genet Med. 2021;23:1391–8. doi: 10.1038/s41436-021-01171-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cancer Institute NSW. eviQ Cancer Treatments Online 2020 https://www.eviq.org.au/.

- 18.Crook A, Plunkett L, Forrest LE, Hallowell N, Wake S, Alsop K, et al. Connecting patients, researchers and clinical genetics services: The experiences of participants in the Australian Ovarian Cancer Study (AOCS) Eur J Hum Genet. 2015;23:152–8. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2014.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rowley SM, Mascarenhas L, Devereux L, Li N, Amarasinghe KC, Zethoven M, et al. Population-based genetic testing of asymptomatic women for breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility. Genet Med. 2019;21:913–22. doi: 10.1038/s41436-018-0277-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McBride K, Hallowell N, Tattersall MN, Kirk J, Ballinger M, Thomas D, et al. Timing and context: important considerations in the return of genetic results to research participants. J Community Genet. 2016;7:11–20. doi: 10.1007/s12687-015-0231-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Willis AM, Smith SK, Meiser B, Ballinger ML, Thomas DM, Young MA. Sociodemographic, psychosocial and clinical factors associated with uptake of genetic counselling for hereditary cancer: a systematic review. Clin Genet. 2017;92:121–33. doi: 10.1111/cge.12868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Metcalfe A, Werrett J, Burgess L, Clifford C. Psychosocial impact of the lack of information given at referral about familial risk for cancer. Psychooncology. 2007;16:458–65. doi: 10.1002/pon.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.