Abstract

Objectives

(1) To elucidate the effectiveness of neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) toward improving activities of daily living (ADL) and functional motor ability post stroke and (2) to investigate the influence of paresis severity and the timing of treatment initiation for the effectiveness of NMES.

Data Sources

PubMed, MEDLINE, Embase, Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) and Cochrane Library searched for relevant articles from database inception to May 2020.

Study Selection

The inclusion criteria were randomized controlled trials exploring the effect of NMES toward improving ADL or functional motor ability in survivors of stroke. The search identified 6064 potential articles with 20 being included.

Data Extraction

Two independent reviewers conducted the data extraction. Methodological quality was assessed using the PEDro scale and the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool.

Data Synthesis

Data from 428 and 659 participants (mean age, 62.4 years; 54% male) for outcomes of ADL and functional motor ability, respectively, were pooled in a random-effect meta-analysis. The analysis revealed a significant positive effect of NMES toward ADL (standardized mean difference [SMD], 0.41; 95% CI, 0.14-0.67; P=.003), whereas no effect on functional motor ability was evident. Subgroup analyses showed that application of NMES in the subacute stage (SMD, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.09-0.78; P=.01) and in the upper extremity (SMD, 0.34; 95% CI, 0.04-0.64; P=.02) improved ADL, whereas a beneficial effect was observed for functional motor abilities in patients with severe paresis (SMD, 0.41; 95% CI, 0.12-0.70; P=.005).

Conclusions

The results of the present meta-analysis are indicative of potential beneficial effects of NMES toward improving ADL post stroke, whereas the potential for improving functional motor ability appears less clear. Furthermore, subgroup analyses indicated that NMES application in the subacute stage and targeted at the upper extremity is efficacious for ADL rehabilitation and that functional motor abilities can be positively affected in patients with severe paresis.

Keywords: Cerebrovascular disorders, Electric stimulation therapy, Neurology, Rehabilitation

List of abbreviations: ADL, activities of daily living; BRS, Brunnstrom recovery stages; CROB, Cochrane risk of bias; EMG, electromyogram; ES, electrical stimulation; FES, functional electrical stimulation; MMT, manual muscle test; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; NMES, neuromuscular electrical stimulation; PEDro, Physiotherapy Evidence Database; SMD, standardized mean difference; TES, therapeutic electrical stimulation

The global incidence of stroke is in the order of 13.7 million annually1 and is a clinical condition typically associated with limb paresis2 secondary to compromised function of upper motor neurons and associated neural pathways, with loss of locomotor function and the ability to perform activities of daily living (ADL) being functional manifestations hereof.3, 4, 5 Although recent medico-scientific advances within the fields of thrombolysis6,7 and thrombectomy8 have spurred major changes to the treatment of acute ischemic stroke, stroke remains a leading cause of disability,1 and effective rehabilitation modalities are thus of utmost importance.

In the newest Clinical Guidelines for Stroke Management9 and Guidelines for Adult Stroke Rehabilitation and Recovery,10 the rehabilitation modality of electrical stimulation (ES) is recommended as a supplementary therapy alongside the standard care modalities. ES can be broadly categorized into functional electrical stimulation (FES) and therapeutic electrical stimulation (TES). The primary difference between these 2 ES modalities is the degree of patient involvement; TES is administered with the patient completely passive or performing isolated muscle contractions, whereas FES is superimposed onto voluntary contractions while the patient is performing functional tasks such as walking, rising from a chair, or stair climbing.11,12 As alluded by Kroon et al,13 TES can be further subcategorized into neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES), electromyogram (EMG)-triggered ES, positional feedback stimulation training, and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation. In EMG-triggered and positional feedback stimulation, the electrical current is administered in response to the patient performing a minor contraction or movement, respectively, whereas NMES is administered according to a preprogrammed scheme and hence is received passively.11,14,15 Evidence suggests that NMES has the ability to strengthen muscles,16,17 reduce spasticity,10 increase excitability of corticospinal neural pathways,18 and augment neuroplasticity.19,20 Furthermore, when ES is administered prior to or after voluntary contractions (eg, NMES) in persons without stroke, it has been demonstrated to be more effective in developing functional motor abilities than both voluntary contractions performed simultaneously with stimulation and voluntary contractions performed in isolation.20,21 The apparent superiority could be governed by a cumulative effect of the 2 types of contractions and/or because of the unique motor drives associated with each type of contraction.21,22

According to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health, poststroke rehabilitation is a complex process that can be viewed in the context of function, activity, and participation domains.23 The activity domain encompasses the full range of life areas from a performance and capacity point of view, the performance level describes an individual's abilities in the actual context in which they live (ADL), and the capacity level entails the ability to execute a specific task or action in a standard environment (functional motor ability).23 ADL reflect the level of disability in daily life and are therefore thought of as the most clinically relevant outcomes in assessing poststroke recovery,24 whereas functional motor abilities are viewed as good surrogate outcomes.

A number of systematic reviews concerning the effectiveness of ES toward regaining overall activity performance post stroke have been published, including 3 Cochrane reviews.17,25,26 However, the majority of said reviews have pooled studies with a variety of ES methods16,25,27, 28, 29, 30, 31 or investigated other specific aspects of ES, typically FES.24,32, 33, 34 In contrast to previous systematic reviews, the aim of the present systematic review and meta-analysis was to elucidate the effectiveness of NMES in improving ADL and functional motor ability post stroke and additionally analyze data according to onset of NMES administration post stroke and paresis severity, which in our opinion are important additions to the stroke rehabilitation literature.

Methods

Literature search and study identification

Although the protocol was not preregistered, it was a priori specified and consistent with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Protocols.35 A systematic search of the literature was conducted in the scientific databases PubMed, MEDLINE, Embase, Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro), and Cochrane Library for relevant English articles published between database inception and May 2020. The search was carried out using keywords related to stroke, rehabilitation, and ES (appendix 1). Reference lists of relevant articles were screened to identify additional articles of relevance. The screening process, carried out by 2 reviewers (M.G.H.K., H.B.) independently, was conducted through reading of titles and abstracts. Full-text versions of potentially relevant articles were obtained and selected according to the criteria listed below. Any disagreements were resolved through comprehensive discussion, and if an agreement could not be attained, a third reviewer (T.W.) was consulted. Data of included trials were extracted independently by each reviewer and recorded in predesigned data forms to ensure a systematic data collection process. If outcome data were not available or unclear, data were extracted from previous Cochrane reviews or authors were contacted. If data could not be obtained, the study was excluded from the meta-analysis.

Study selection

Participants

Trials included adults (18 years or older) with clinically diagnosed stroke.1 No specific criteria were set regarding the participants’ level of disability or the timing of intervention initiation in relation to the stroke.

Interventions

Trials were randomized controlled trials investigating the effect of NMES. As previously alluded to by Pomeroy et al,25 the terminology used within the field of ES is quite inconsistent; we therefore included or excluded studies according to our interpretation of whether the intervention was consistent with NMES and not the terminology adopted by the respective authors. Only studies administering NMES to either the upper or lower extremity through surface electrodes were considered. No criteria were set regarding stimulation characteristics (pulse duration, frequency etc); however, the documentation of a visible muscle contractions was required. The only difference between the control and intervention groups was the administration of ES. Theses or articles published only as abstracts were not included.

Outcomes

Endpoint measurements explored activity outcomes defined by the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health as the category Activity.23 Primary outcomes were measures of ADL; secondary outcomes were measures of functional motor ability. Where multiple measures were available in 1 study at either the motor or ADL level, the measure with the highest prevalence in the present pool of studies was selected to minimize heterogeneity. Only outcome measures at the end of the treatment were identified.

Assessment of risk of bias

Study methodological quality was quantified by the PEDro scale36 and the Cochrane risk of bias (CROB) tool.37 The PEDro scale is widely used in the field of physical therapy and consists of 11 items, criteria 1 concerning external validity, criteria 2-9 encompassing various aspects of internal validity, and criteria 10-11 being associated with the degree of statistical availability. Each item is rated as “yes” or “no,” and the final PEDro score is the number of items being satisfactorily fulfilled (excluding criteria 1 regarding external validity). Studies were scored according to the following system; excellent: 9-10 points, good: 6-8 points, fair: 4-5 points, and poor: ≤3 points. The CROB tool evaluates potential bias for 7 items across 6 domains: selection, performance, detection, attrition, and reporting bias and other sources of bias. Each of the 7 items is rated as “high,” “unclear,” or “low” risk of bias and are reported separately. Quality assessment was carried out independently by 2 reviewers (M.G.H.K., H.B.), with any disagreement resolved through discussion or consensus with a third reviewer (T.W.).

Data analysis

The extracted continuous outcomes (postintervention mean and SD) were subjected to a random-effect model calculating standardized mean difference (SMD) because of the different outcome measures.38 If >2 intervention or control groups in a given trial were relevant to the present review, these were merged according to the recommendations of the Cochrane handbooks formulae39 using the following equations:

where N is the group sample size, M is the postintervention mean, SD the associated SD, and 1 and 2 the group designations.

Subgroup analyses were conducted to elucidate the importance of (1) location of stimulation (upper vs lower limb); (2) time since stroke (acute <7 days, subacute 7 days to 6 months, chronic >6 months)40; and (3) severity of paresis as assessed either by a global severity score (eg, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale41 [NIHSS], Brunnstrom recovery stages42 [BRS]) or the level of muscle strength (eg, manual muscle test43 [MMT]). Studies were grouped according to the severity of preintervention paresis; mild (NIHSS 1 [motor function arm/leg], BRS 5, MMT 3–4), moderate (NIHSS 2 [motor function arm/leg], BRS 3-4, MMT 2), or severe paresis (NIHSS 3-4 [motor function arm/leg], BRS 1-2, MMT 0-1). Interstudy heterogeneity was evaluated through I2 statistic, with substantial heterogeneity defined as >50%.38 To identify possible sources of heterogeneity, a leave-1-out sensitivity analysis was conducted to quantify the effect of individual trials on the merged results. All statistical analyses were carried out using Review Manager 5.3.a

Results

Search results

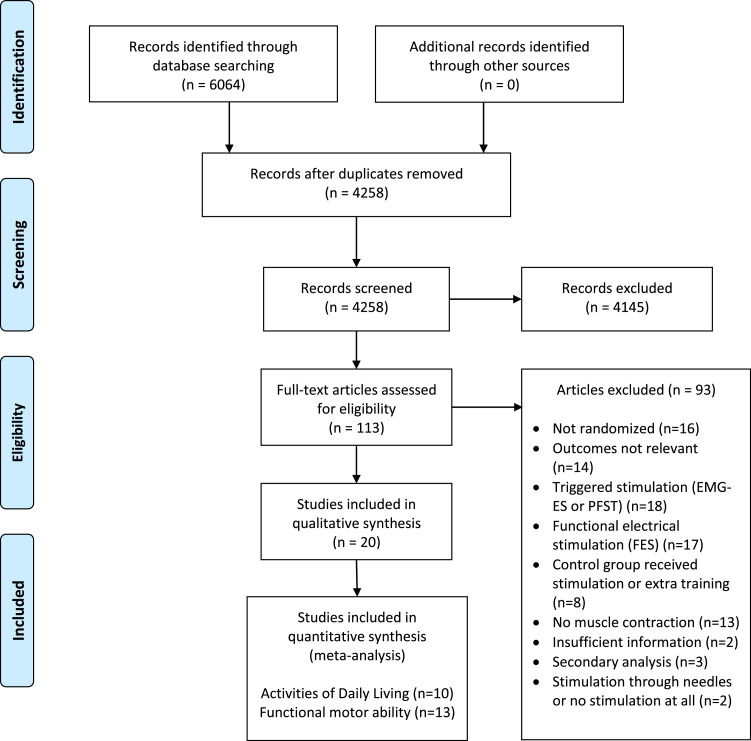

The literature search identified 6064 articles of potential relevance (fig 1), with title and abstract screening eliminating 5951, thus leaving 113 trials. No additional articles of relevance were identified through reference lists screenings. A total of 93 studies were excluded during the full-text review process, thus leaving 20 for final inclusion. Of these, 12 trials were included in the ADL analyses, 16 were included in the analyses pertaining to functional motor ability, and 8 trials were featured in both.

Fig 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow chart for study identification. Abbreviation: PFST, positional feedback stimulation training.

Participant characteristics

End of treatment results were collected from 956 patients with stroke (demographic data on 972 participants) with study sample sizes ranging from 14-163 participants. Eighty-nine dropouts were registered, with early discharge, death, or additional illness (eg, an additional stroke) being the most frequent causes. No adverse effects of stimulation were reported in any of the trials. Demographics and characteristics of included studies are presented in table 1. The participants were predominantly male (54%), with a mean age of 62.4 years (range, 51-75 years; 2 studies reported median age of 72.5 years [range, 64-81 years]44 and 71.5 years [range, 59-84 years]45). Sixteen trials provided specific paresis information (57% left-sided) and type of stroke (79% infarcts). Thirteen trials investigated patients in the subacute stage, ranging from 9 days to 4 months post stroke, whereas 3 and 4 trials featured patients in the acute44,45,50 and chronic48,54,55,57 stages, respectively. Severity of paresis was most frequently reported as a measure of global severity, with 7 trials reporting BRS47,54,57, 58, 59,61,63 and 3 NIHSS.44, 45, 46 Five trials reported MMT,49,50,52,60,62 whereas Rosewilliam et al53 provided a direct measure of strength. Kim48 and Sonde55 and colleagues provided Fugl-Meyer Assessment scores (global impairment),64 and McDonnell51 and Zhou56 and colleagues measured active range of motion. Five and 6 studies encompassed patients with moderate and severe paresis, respectively, with no studies including patients with mild paresis. Five studies failed to specify mean or median values and had wide ranging inclusion criteria such as mild to severe paresis (MMT≤3-4),49,52 mild to moderate paresis (MMT 2-3),60 and moderate to severe paresis (MMT≤2).50,62

Table 1.

Demographics and characteristics of included studies

| Upper Limb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Participants | Intervention | Stimulation | Outcome |

| Church et al44 | N=163 (89 exp/84 con) | Exp: dual channel, 60 min | Muscles: shoulder abd. | Motor: ARAT |

| Age (y): 72.5 (range, 64-81) | Con: sham, 60 min | Frequency: 30 Hz | ADL: only at follow-up | |

| Time since stroke: 3-7 d | 3/d × 7 d/wk × 4 wk | Pulse width: NA | ||

| Paresis: moderate | Program: cyclic, 15 s on/off, | |||

| (NIHSS mean 2 motor arm) | 3 s up/down | |||

| Fletcher- | N=35 (18 exp/17 con) | Exp: dual channel, 30 min | Muscles: wrist ext.+flex. | Motor: ARAT |

| Smith et al45 | Age (y): 71.5 (range, 59-84) | Con: nothing | Frequency: 40-60 Hz | ADL: BI |

| Time since stroke: <72 h | 2/d × 5 d/wk × 3 mo | Pulse width: 450 µs | ||

| Paresis: severe (NIHSS | Program: cyclic, constant current | |||

| median, 3-4 motor arm) | flex-hold-extend-hold pattern | |||

| Hochsprung | N=14 (7 exp/7 con) | Exp: dual channel, 30 min | Muscles: shoulder flex.+ext. | Motor: ARAT |

| et al46 | Age (y), mean ± SD: 62±9.6 | Con: nothing | Frequency: 30-50 Hz | ADL: BI |

| Time since stroke: <6 mo | 1/d × 7 d/wk × 4 wk | Pulse width: 250 µs | ||

| Paresis: severe | Program: cyclic, 5 s on/7 s off, | |||

| (NIHSS=4 motor arm) | 0.6s ramp up | |||

| Hsu et al47 | N=66 (44 exp/22 con) | Exp: dual channel, | Muscles: finger ext.+flex./ | Motor: ARAT |

| Age (y): 63±11 | 30 or 60 min | finger ext./shoulder abd. | ADL: not measured | |

| Time since stroke: 21±17 d | Con: nothing | Frequency: NA | ||

| Paresis: severe | 1/d × 5 d/wk × 4 wk | Pulse width: NA | ||

| (BRS mean, 2) | Program: NA | |||

| Kim et al48 | N=30 (15 exp/15 con) | Exp: dual channel, 30 min | Muscles: elbow+wrist ext. | Motor: BBT |

| Age (y): 62±9 | Con: sham, 30 min | Frequency: 100 Hz | ADL: not measured | |

| Time since stroke: 13±10 mo | 1/d × 5 d/wk × 4 wk | Pulse width: 200 µs | ||

| Paresis: NA | Program: NA | |||

| Lin et al49 | N=37 (19 exp/18 con) | Exp: dual channel, 30 min | Muscles: shoulder abd. | Motor: not measured |

| Age (y): 64±9 | Con: nothing | +wrist ext. | ADL: MBI | |

| Time since stroke: 42±26 d | 1/d × 5 d/wk × 3 wk | Frequency: 30 Hz | ||

| Paresis: Mild to severe | Pulse width: 300 µs | |||

| (MMT shoulder flexor ≤3) | Program: cyclic, 5 s on/off, | |||

| 1 s up/down | ||||

| Linn et al50 | N=40 (20 exp/20 con) | Exp: dual channel | Muscles: shoulder abd. | Motor: MAS, |

| Age (y): 72 | 30 min → 60 min | Frequency: 30 Hz | upper arm section | |

| Time since stroke: 1-2 d | Con: nothing | Pulse width: 300 µs | ADL: not measured | |

| Paresis: Moderate to severe | 4/d × 7 d/wk × 4 wk | Program: cyclic, 15 s on/off, | ||

| (MMT upper limb ≤2) | 3 s up/down | |||

| McDonnell | N=20 (10 exp/10 con) | Exp: dual channel, 60 min | Muscles: finger abd. | Motor: ARAT |

| et al51 | Age (y): 66±12 | Con: sham, 60 min | Frequency: NA | ADL: not measured |

| Time since stroke: 4±2 mo | 1/d × 3 d/wk × 3 wk | Pulse width: 100 µs | ||

| Paresis: NA | Program: constant-current | |||

| Powell et al52 | N=55 (27 exp/28 con) | Exp: dual channel, 30 min | Muscles: wrist+finger ext. | Motor: ARAT |

| Age (y): 68±12 | Con: nothing | Frequency: 20 Hz | ADL: BI | |

| Time since stroke: 23±7 d | 3/d × 7 d/wk × 8 wk | Pulse width: 300 µs | ||

| Paresis: Mild to severe | Program: cyclic, 5 s on/20 s off | |||

| (MMT wrist extension ≤4) | → 5 s on/off, 1 s up/1,5 s down | |||

| Rosewilliam | N=80 (39 exp/41 con) | Exp: single channel, 30 min | Muscles: wrist+finger ext. | Motor: ARAT |

| et al53 | Age (y): 75±11 | Con: nothing | Frequency: 40 Hz | ADL: BI |

| Time since stroke: ≤6 wk | 2-3/d × 5 d/wk × 6 wk | Pulse width: 300 µs | ||

| Paresis: Severe | Program: cyclic, 15 s on/off, | |||

| (wrist ext. 0.1±0.4N) | 6 s up/down | |||

| Sahin et al54 | N=42 (21 exp/21 con) | Exp: single channel, 15 min | Muscles: wrist ext. | Motor: not measured |

| Age (y): 60±8 | Con: nothing | Frequency: 100 Hz | ADL: FIM | |

| Time since stroke: 30±20 mo | 1/d × 5 d/wk × 4 wk | Pulse width: 100 µs | ||

| Paresis: moderate | Program: cyclic, 3 ms, 9 s off, | |||

| (BRS median, 3) | interval 0.9 ms | |||

| Sonde et al55 | n = 44 (26 exp/18 con) | Exp: dual channel, 60 min | Muscles: wrist ext± | Motor: not measured |

| Age (y): 72±5 | Con: nothing | elbow ext./shoulder abd. | ADL: BI | |

| Time since stroke: 9±2 mo | 1/d × 5 d/wk × 3 mo | Frequency: 1.7 Hz | ||

| Paresis: NA | Pulse width: NA | |||

| Program: 8 trains, 14-ms interval | ||||

| Zhou et al56 | N=49 (31 exp/18 con) | Exp: dual channel, 60 min | Muscles: shoulder abd. | Motor: not measured |

| Age (y): 62±11 | Con: nothing | Frequency: 15 Hz | ADL: BI | |

| Time since stroke: 90±98 d | 1/d × 5 d/wk × 4 wk | Pulse width: 200 µs | ||

| Paresis: NA | Program: 10 s on/off, | |||

| 5 s up/down | ||||

| Gürcan et al57 | N=32 (19 exp/13 con) | Exp: dual channel, 20 min | Muscles: ankle ext. | Motor: FAS |

| Age (y): 58±12.5 | Con: nothing | Frequency: 20 Hz | ADL: FIM | |

| Time since stroke: 14±19 mo | 1/d × 5 d/wk × 3 wk | Pulse width: 300 µs | ||

| Paresis: moderate | Program: NA | |||

| (BRS mean, 3) | ||||

| Tan et al58 | N=45 (30 exp/15 con) | Exp: 4 or dual | Muscles: hip, knee, and ankle | Motor: BBS |

| Age (y): 65±9 | channel, 30 min | flex. + ext. / ankle flex. | ADL: MBI | |

| Time since stroke: 41±24 d | Con: nothing | Frequency: 30 Hz | ||

| Paresis: moderate | 1/d × 5 d/wk × 3 wk | Pulse width: 200 µs | ||

| (BRS mean, 3) | Program: cyclic, to mimic gait | |||

| Wang et al59 | N=53 (36 exp/17 con) | Exp: dual channel, 30 min | Muscles: ankle flex., toe ext. | Motor: TUG |

| Age (y): 51±10 | Con: nothing | Frequency: 20 Hz | ADL: not measured | |

| Time since stroke: 29±9 d | 2/d × 5 d/wk × 4 wk | Pulse width: 200 µs | ||

| Paresis: moderate | Program: cyclic, 5 s on/off, | |||

| (BRS mean, 4) | intensity according to group | |||

| Yan et al60 | N=26 (13 exp/13 con) | Exp: 2 dual channel, 30 min | Muscles: hip, knee, and | Motor: TUG |

| Age (y): 69±8 | Con: nothing | ankle flex.+ext. | ADL: not measured | |

| Time since stroke: 9±5 d | 1/d × 5 d/wk × 3 wk | Frequency: 30 Hz | ||

| Paresis: Mild to moderate | Pulse width: 300 µs | |||

| (MMT hip flexion 2-3) | Program: cyclic, to mimic gait | |||

| Yavuzer et al61 | N=25 (12 exp/13 con) | Exp: single channel, 10 min | Muscles: ankle flex. | Motor: walking velocity |

| Age (y): 55±8 | Con: nothing | Frequency: 80 Hz | ADL: not measured | |

| Time since stroke: 2±2 mo | 1/d × 5 d/wk × 4 wk | Pulse width: 100 µs | ||

| Paresis: moderate | Program: cyclic, 10 s on/50 s off, | |||

| (BRS mean, 3) | 2 s up/1 s down. | |||

| You et al62 | N=37 (19 exp/18 con) | Exp: dual channel, 30 min | Muscles: ankle flex.+eversion | Motor: BBS |

| Age (y): 62±10 | Con: nothing | Frequency: 30 Hz | ADL: MBI | |

| Time since stroke: 24±19 d | 1/d × 5 d/wk × 3 wk | Pulse width: 200 µs | ||

| Paresis: moderate to severe | Program: NA | |||

| (MMT ankle dorsal | ||||

| flexion <3) | ||||

| Zheng et al63 | N=48 (33 exp/15 con) | Exp: 4 or dual channel, | Muscles: hip, knee, ankle flex. | Motor: BBS |

| Age (y): 59±10 | 30 min | + ext./ankle flex.+eversion | ADL: MBI | |

| Time since stroke: 20±12 d | Con: sham, 30 min | Frequency: 30 Hz | ||

| Paresis: severe | NA/d × NA d/wk × 3 wk | Pulse width: 200 µs | ||

| (BRS mean, 2) | Program: cyclic, to mimic gait |

Abbreviations: abd., abduction; ARAT, Action Research Arm Test; BBS, Berg Balance Scale; BBT, Box and Block Test; BI, Barthel Index; con, control; exp, experimental; ext., extension; FAS, Functional Ambulation Scale; flex., flexion; MAS, Motor Assessment Scale; MBI, Modified Barthel Index; NA, not available; TUG, timed Up and Go.

Stimulation protocols

Thirteen trials administered stimulation to the upper extremity (5 with outcomes addressing functional motor ability,44,47,48,50,51 4 addressing ADL,49,54, 55, 56 and 4 addressing both types of outcomes45,46,52,53), primarily to the shoulder abductors and wrist extensors in isolation or in conjunction with additional muscle groups such as the wrist flexors, elbow extensors, and/or finger extensors and/or flexors. Seven trials used lower extremity stimulation (3 with outcomes addressing functional motor ability59, 60, 61 and 4 addressing both ADL and functional motor ability outcomes52,57,58,63), most frequently targeting the ankle dorsal flexors exclusively or in conjunction with hip and knee flexors and extensors, toe extensors, and ankle evertors. The characteristics of the stimulation protocols are available in table 1. The intervention duration ranged from 3 weeks to 3 months, with most trials spanning 3-4 weeks with individual sessions of 10-60 minutes, 1-4 times daily, and 3-7 weekly sessions. The typical NMES protocol consisted of cyclic stimulation with a frequency of 30 Hz (range, 1.7-100Hz) at a fixed pulse width of 200-300 µs (range, 100-450µs). The amplitude was most frequently reported as being individually adjusted to achieve a visible muscle contraction or joint movement.

Risk of bias

The mean PEDro score was 5.8 (range, 4-8), and the majority of studies (n=13) were rated as “good.” A detailed overview of the PEDro scoring is provided in table 2. The low scores were primarily because of lack of blinding because none of the included studies featured blinded therapists and only 2 studies encompassed participant blinding. According to the CROB tool assessment there were concerns regarding the description of the random sequence generation because the vast majority of the trials only described the process as being randomized without further elaboration. Six studies showed selective reporting, and 3 studies had high risk of “other bias,” typically because of the sample size being smaller than needed according to a priori power analysis. The individual results are displayed and summarized in fig 2 and fig 3, respectively. None of the included studies exhibited significant asymmetry (ADL: 1.47; 95% CI, −2.94 to 5.87; P=.53. Functional motor ability: −0.005; 95% CI, −2.92 to 2.91; P>.99). according to Egger's test as calculated with RStudio.b

Table 2.

Methodological quality assessment using PEDro score

| Author | Random | Concealed | Baseline | Blinded | Blinded | Blinded | Adequate | Intention | Between- | Point Estimate | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allocation | Allocation | Comparability | Participants | Therapists | Assessors | Follow-up | to Treat | Group | & Variability | ||||

| Church et al44 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | ||

| Fletcher-Smith et al45 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | ||

| Gürcan et al57 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 | ||

| Hochsprung et al46 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | ||

| Hsu et al47 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | ||

| Kim et al48 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 | ||

| Lin et al49 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 | ||

| Linn et al50 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 | ||

| McDonnell et al51 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 8 | ||

| Powell et al52 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 7 | ||

| Rosewilliam et al53 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | ||

| Sahin et al54 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 | ||

| Sonde et al55 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 | ||

| Tan et al58 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | ||

| Wang et al59 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 | ||

| Yan et al60 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 | ||

| Yavuzer et al61 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 7 | ||

| You et al62 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 | ||

| Zheng et al63 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | ||

| Zhou et al56 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 | ||

Fig 2.

Cochrane risk of bias tool: risk of bias summary.

Fig 3.

Cochrane risk of bias tool: risk of bias graph.

NMES and ADL

The effect of NMES toward ADL function was examined through a random-effect model by pooling postintervention data from 10 trials of 428 participants. A moderate effect of NMES toward ADL was observed compared with control (SMD, 0.41; 95% CI, 0.14-0.67; I2=42%; P=.003) (fig 4). Powell52 and Fletcher-Smith45 and colleagues were not included in this part of the meta-analysis because of incomplete reporting of data. Subgroup analysis showed a significant positive effect in the upper extremity (SMD, 0.34; 95% CI, 0.04-0.64; I2=29%; P=.02), whereas only a tendency was observed in the lower extremity (SMD, 0.49; 95% CI, −0.04 to 1.03; I2=61%; P=.07) (fig 4). A significant positive effect was identified in the subacute stage (SMD, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.09-0.78; I2=50%; P=.01), which was not the case in the chronic stage (SMD, 0.35; 95% CI, −0.14 to 0.84; I2=42%; P=.16) (fig 5). No trials included participants with a stroke in the acute stage. No effect of paresis severity was observed, with both moderate (SMD, 0.21; 95% CI, −0.16 to 0.58; I2=0%; P=.26; n=3) and severe (SMD, 0.36; 95% CI, −0.55 to 1.26; I2=81%; P=.44; n=3) subgroups demonstrating positive but insignificant effects (fig 6).

Fig 4.

Effect of NMES on ADL: subgroup analysis on limb stimulation.

Fig 5.

Effect of NMES on ADL: subgroup analysis on stage of stroke.

Fig 6.

Effect of NMES on ADL: subgroup analysis on degree of paresis.

NMES and functional motor ability

The effect of NMES toward functional motor ability was examined through a random-effect model by pooling data from 13 trials (659 participants), with 3 studies45,51,52 not included because of incomplete reporting of data. No significant effect of NMES was detected (SMD, 0.15; 95% CI, −0.13 to 0.43; I2=64%; P=.30) (fig 7), which was also the case when the upper (SMD, 0.18, 95% CI, −0.05 to 0.40; I2=13%; P=.12) and lower limbs (SMD, 0.00; 95% CI, −0.56 to 0.56; I2=78%; P=.99) (fig 7) were analyzed separately. The stage of stroke did not appear to affect the results because the acute (SMD, −0.03; 95% CI, −0.31 to 0.24; I2=0%; P=.89), subacute (SMD, 0.22; 95% CI, −0.15 to 0.58; I2=65%; P=.25), and chronic stages (SMD, 0.03; 95% CI, −1.40 to 1.46; I2=87%; P=.97) (fig 8) did not demonstrate a positive effect. Subgroup analyses indicated a positive effect in patients with severe paresis (SMD, 0.41; 95% CI, 0.12-0.70; I2=1%; P=.005; n=4), which was not the case in patients with moderate paresis (SMD, −0.24; 95% CI, −0.77 to 0.30; I2=76%; P=.39; n=5), with no studies encompassing patients with mild paresis (fig 9).

Fig 7.

Effect of NMES on functional motor ability: subgroup analysis on limb stimulation.

Fig 8.

Effect of NMES on functional motor ability: subgroup analysis on stage of stroke.

Fig 9.

Effect of NMES on functional motor ability: subgroup analysis on degree of paresis.

Sensitivity analysis

The meta-analysis regarding functional motor ability was associated with substantial heterogeneity, and a leave-1-out sensitivity analysis was thus performed to assess the influence of the individual studies. This analysis revealed that the exclusion of Yavuzer et al61 reduced the heterogeneity from I2=64% to I2=45% and furthermore resulted in a significant (P=.04) positive effect of NMES. This is further supported by the forest plot for functional motor ability (see fig 7) illustrating Yavuzer as a potential outlier. In the subgroup analyses, the heterogeneity was attenuated from I2=78% to I2=64% for the lower extremity and from I2=65% to I2=1% in the subacute stage, with the results becoming significant in the latter (P=.0009).

Discussion

The objectives of the present systematic review and meta-analysis were to explore the effect of NMES toward improving ADL and functional motor ability post stroke. In summary, NMES improved ADL, whereas no effect on functional motor ability was evident. Subgroup analyses showed that application of NMES in the subacute stage and applied to the upper extremity resulted in a significant improvement in ADL, with no apparent effect of treatment in the chronic stage and lower extremity application. Furthermore, NMES had a significant effect for improving functional motor abilities in patients with severe paresis, whereas treatment of moderate paresis was insignificant.

The different treatment effects of NMES toward improving ADL and functional motor abilities is consistent with a previous meta-analysis regarding FES24 where the authors speculated that the difference was governed by the patient characteristics of their analysis, all being in the chronic stage, which is not the case for our analysis. We propose that this result could be explained by 1 or both of the 2 following reasons. First, there are strong indications in the literature that poststroke motor recovery occurs partly through behavioral compensation rather than a “true” physiological recovery per se.65 Therapies using compensatory strategies are known to achieve functional goals sooner than therapies that do not allow for behavioral compensation.65,66 The most frequently adopted measure of functional motor abilities in the studies included is the Action Research Arm Test,67 which rates patients ability to perform tasks “normally” whereas the Barthel Index68,69 evaluates to what degree tasks are performed independently, not normally, thus allowing use of compensatory strategies. Perhaps the apparent ability of NMES to improve ADL is underpinned by the test's acceptance of patients’ preferred movement pattern, making them able to detect minor but important recovery improvements sooner. Second, in the sensitivity analysis the study by Yavuzer et al was excluded, which resulted in a significant positive effect of NMES toward functional motor abilities, eliminating the apparent contrast regarding the effectiveness of NMES toward ADL and functional motor abilities, respectively. Yavuzer reported a significant difference in baseline mean walking velocity between the intervention and control groups, which might have influenced their results.

In line with earlier work,70,71 our subgroup analysis revealed a positive effect of NMES toward ADL in the subacute stage, with no apparent effect in the chronic stage. This observation could possibly relate to the mechanisms underlying strength attenuation, initially because of a loss of descending motor drive, whereas decreased muscle cross sectional area, spasticity and long-term reduction of motor units secondary to inactivity govern later-stage strength reduction.27,72 The subgroup analysis on paresis severity showed a positive effect of NMES in patients with severe paresis, with insignificant results in moderate paresis, which is in contrast to previous related work indicating a superior rehabilitation potential and prognosis in patients with paresis compared with patients with paralysis.71,73 The positive effect in patients with severe paresis might be because of the feasibility of NMES in a patient population with limited capacity for voluntary training. These results, however, should be interpreted with caution because only half of the studies were included in this subgroup analysis because of poor data reporting.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Our search identified a considerable number of studies applying NMES through triggering devices or applied during voluntary movement. Because this was not the focus of our review, these studies were excluded, and the present results are thus not generalizable throughout the entirety of the ES research domain. This narrow review question was chosen with the aim of guiding practitioners in the process of choosing between multiple different ES modalities. Even though 20 studies were included, the underlying evidence for NMES is not complete. Overall, the patients were similar regarding sex and age, and to strengthen our study, the differences in time since stroke and severity of paresis were addressed by the subgroup analyses, but because none or only a small number of studies included participants within the first week post stroke (acute stage), 6 months post stroke (chronic), or with mild paresis, we are unable to draw firm conclusions regarding the effectiveness of NMES in these patient populations. Furthermore, it appears that there are no universally agreed on stimulation parameters, and none of the included studies used the same stimulation protocol, with heterogeneity in parameters of importance such as stimulation channels, time per stimulation session, and the intervention duration. Although we exclusively included studies that produced muscle contractions through stimulation to minimize heterogeneity and strengthen our results, this was accomplished with different stimulation parameters, for example, Sonde et al55 applied low frequencies of 1.7 Hz in pulse trains, whereas the majority of studies used relatively high frequencies (≥20Hz) in a cyclical pattern, thus contributing to the overall high degree of interstudy variability and thus equivocality of the evidence pertaining to NMES.

Comparison with previous reviews

Two previous systematic reviews13,16 have examined the effect of NMES on activity measures post stroke; however, both including studies featuring EMG-triggered ES. De Kroon et al13 analyzed motor control and functional motor abilities and identified 6 relevant trials overall, 2 with functional motor ability measures. Although a meta-analysis was not performed, it was concluded that a positive effect of NMES on motor control exists, but no conclusions were drawn concerning the effect on functional motor abilities. Nascimento et al16 analyzed the effect of ES on strength and conducted a secondary analysis to delineate whether this improvement carried over to measures of activity, identifying 16 relevant trials with 6 including measures of activity. Meta-analysis showed that ES had a moderate positive effect on strength and a small to moderate positive effect on activity, with the benefits extending beyond the intervention period for both measures. Nascimento performed their systematic literature search in December 2012, including 3 trials also included in the present review. The present review identified 8 additional trials investigating activity from the same period and 9 trials published afterward, thus justifying an updated analysis.

Study limitations

The present review is associated with some limitations that should be kept in mind when interpreting the results. The mean PEDro score of 5.8 only represents fair quality. Both the PEDro score and CROB tool revealed high risk of bias concerning blinding, thus increasing the risk of performance bias, which is a perennial issue in ES studies25 because of the nature of the intervention. Also, our protocol was not registered a priori, introducing the possibility of reporting bias. We identified studies for inclusion by searching across multiple medical and physiotherapy related databases, but we limited our search to English literature and no gray literature search was conducted. The extent of our search potentially confounded the pool of included studies; however, the Egger's test does not appear to be indicative of this being the case. Lastly, studies were only included if the sole difference between the intervention and control group was ES; therefore, the groups received the same amount of physical training, but the intervention group additionally received stimulation outside formal sessions. Time in therapy is a robust predictor of recovery across different types of therapy74 and is known to bias the results in favor of the group receiving more therapy.75,74 Therefore, one could argue that our review question is inherently biased and our positive results toward NMES is a result of more therapy time. On the other hand, the sole effect of NMES was best disclosed by comparing it with nothing or placebo, and therefore our results indicate that NMES could be one of multiple ways to increase therapy time.

Conclusions

The results of the current systematic review and meta-analysis are indicative of a significant positive effect of NMES toward ADL function in the poststroke rehabilitation process, whereas the potential for improving functional motor ability appears to be less clear. Subgroup analysis indicated that NMES application in the subacute stage and targeted at the upper extremity is efficacious for ADL rehabilitation and that functional motor abilities can be positively affected in patients with severe paresis. Although the present results are generally in favor of NMES in poststroke rehabilitation, the only fair mean methodological quality of the included trials should be kept in mind. Furthermore, one should be cognizant that the apparent benefits of NMES are in reference to nothing or placebo and not supplementary training, and the results could thus be somewhat influenced by the additional time devoted to these patients. Future studies comparing different therapeutic interventions applicable outside formal sessions to maximize total therapy time without extra rehabilitation resources for both patients and the health care system appear warranted.

Suppliers

a. Review Manager version 5.3; The Cochrane Collaboration. b. RStudio version 1.4; RStudio Public Benefit Corporation.

Footnotes

Disclosures: none

Appendix 1: Search Strategy PubMed, MEDLINE

-

1.

Cerebrovascular disorders [MeSH]

-

2.

Stroke* OR poststroke OR post-stroke OR CVA

-

3.

cerebrovasc* OR cerebral vascular

-

4.

cerebral OR cerebellar OR brain OR vertebrobasilar

-

5.

infarct* OR ischemi* OR thrombos* OR thromboe* OR emboli* OR apoplexy

-

6.

4 AND 5

-

7.

cerebral OR brain OR subarachnoid

-

8.

haemorrhage OR hemorrhage OR haematoma OR hematoma

-

9.

7 AND 8

-

10.

1 OR 2 OR 3 OR 6 OR 9

-

11.

Electric stimulation therapy [MeSH]

-

12.

electric* stimulat* OR muscu* stimulat* OR muscle* stimulat*

-

13.

neuromusc* stimulat* OR nerve stimulat* OR transcutaneous nerve stimulat*

-

14.

transcutaneous muscu* stimulat* OR transcutaneous muscle* stimulat*

-

15.

NMES OR FES OR TES OR TENS OR electrostimulat* OR electrotherap*

-

16.

11 OR 12 OR 13 OR 14 OR 15

-

17.

Upper Extremity [MeSH]

-

18.

upper limb OR upper extremit*

-

19.

shoulder OR arm OR forearm OR wrist OR hand OR finger OR digit

-

20.

17 OR 18 OR 19

-

21.

Lower Extremity [MeSH]

-

22.

lower limb OR lower extremit*

-

23.

leg OR hip OR thigh OR crus OR foot OR knee OR ankle OR toe OR gait

-

24.

21 OR 22 OR 23

-

25.

20 OR 24

-

26.

10 AND 16 AND 25

-

27.

humans[mesh:noexp]

-

28.

26 AND 27

-

29.

animals[mesh:noexp]

-

30.

28 NOT 29

-

31.

migrain* OR epilep* OR myocard* OR headache* OR heart* OR parkinson*

-

32.

30 NOT 31

References

- 1.GBD 2016 Stroke Collaborators Global, regional, and national burden of stroke, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18:439–458. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30034-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonita R, Beaglehole R. Recovery of motor function after stroke. Stroke. 1988;19:1497–1500. doi: 10.1161/01.str.19.12.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pound P, Gompertz P, Ebrahim S. A patient-centred study of the consequences of stroke. Clin Rehabil. 1998;12:338–347. doi: 10.1191/026921598677661555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sveen U, Bautz-Holter E, Sødring KM, Wyller TB, Laake K. Association between impairments, self-care ability and social activities 1 year after stroke. Disabil Rehabil. 1999;21:372–377. doi: 10.1080/096382899297477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robinson CA, Shumway-Cook A, Matsuda PN, Ciol MA. Understanding physical factors associated with participation in community ambulation following stroke. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33:1033–1042. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2010.520803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fransen PS, Beumer D, Berkhemer OA, et al. MR CLEAN, a multicenter randomized clinical trial of endovascular treatment for acute ischemic stroke in the Netherlands: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2014;15:343. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomalla G, Simonsen CZ, Boutitie F, et al. MRI-guided thrombolysis for stroke with unknown time of onset. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:611–622. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1804355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Albers GW, Marks MP, Kemp S, et al. Thrombectomy for stroke at 6 to 16 hours with selection by perfusion imaging. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:708–718. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1713973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stroke Foundation. Clinical guidelines for stroke management. Available at: https://informme.org.au/Guidelines/Clinical-Guidelines-for-Stroke-Management-2017. Accessed February 26, 2021.

- 10.Winstein CJ, Stein J, Arena R, et al. Guidelines for adult stroke rehabilitation and recovery: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2016;47:e98–169. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Kroon JR, Ijzerman MJ, Chae J, Lankhorst GJ, Zilvold G. Relation between stimulation characteristics and clinical outcome in studies using electrical stimulation to improve motor control of the upper extremity in stroke. J Rehabil Med. 2005;37:65–74. doi: 10.1080/16501970410024190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quandt F, Hummel FC. The influence of functional electrical stimulation on hand motor recovery in stroke patients: a review. Exp Transl Stroke Med. 2014;6:9. doi: 10.1186/2040-7378-6-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Kroon JR, van der Lee JH, IJzerman MJ, Lankhorst GJ. Therapeutic electrical stimulation to improve motor control and functional abilities of the upper extremity after stroke: a systematic review. Clin Rehabil. 2002;16:350–360. doi: 10.1191/0269215502cr504oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson RD, Page SJ, Delahanty M, et al. Upper-limb recovery after stroke: a randomized controlled trial comparing EMG-triggered, cyclic, and sensory electrical stimulation. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2016;30:978–987. doi: 10.1177/1545968316650278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knutson JS, Fu MJ, Sheffler LR, Chae J. Neuromuscular electrical stimulation for motor restoration in hemiplegia. Phys Med Rehabil Clin North Am. 2015;26:729–745. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2015.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nascimento LR, Michaelsen SM, Ada L, Polese JC, Teixeira-Salmela LF. Cyclical electrical stimulation increases strength and improves activity after stroke: a systematic review. J Physiother. 2014;60:22–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jphys.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pollock A, Farmer SE, Brady MC, et al. Interventions for improving upper limb function after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;11 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010820.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaneko F, Hayami T, Aoyama T, Kizuka T. Motor imagery and electrical stimulation reproduce corticospinal excitability at levels similar to voluntary muscle contraction. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2014;11:94. doi: 10.1186/1743-0003-11-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ridding MC, Uy J. Changes in motor cortical excitability induced by paired associative stimulation. Clin Neurophysiol. 2003;114:1437–1444. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(03)00115-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pyndt HS, Ridding MC. Modification of the human motor cortex by associative stimulation. Exp Brain Res. 2004;159:123–128. doi: 10.1007/s00221-004-1943-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vanderthommen M, Duchateau J. Electrical stimulation as a modality to improve performance of the neuromuscular system. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2007;35:180–185. doi: 10.1097/jes.0b013e318156e785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paillard T. Combined application of neuromuscular electrical stimulation and voluntary muscular contractions. Sports Med. 2008;38:161–177. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200838020-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. World Health Organization. Available at: https://apps.who.int/classifications/icfbrowser/. Accessed December 4, 2020.

- 24.Eraifej J, Clark W, France B, Desando S, Moore D. Effectiveness of upper limb functional electrical stimulation after stroke for the improvement of activities of daily living and motor function: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst Rev. 2017;6:40. doi: 10.1186/s13643-017-0435-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pomeroy VM, King L, Pollock A, Baily-Hallam A, Langhorne P. Electrostimulation for promoting recovery of movement or functional ability after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;2 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003241.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mendes LA, Lima IN, Souza T, do Nascimento GC, Resqueti VR, Fregonezi GA. Motor neuroprosthesis for promoting recovery of function after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;1 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012991.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ada L, Dorsch S, Canning CG. Strengthening interventions increase strength and improve activity after stroke: a systematic review. Aust J Physiother. 2006;52:241–248. doi: 10.1016/s0004-9514(06)70003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Veerbeek JM, van Wegen E, van Peppen R, et al. What is the evidence for physical therapy poststroke? A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e87987. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin IH, Tsai HT, Wang CY, Hsu CY, Liou TH, Lin YN. Effectiveness and superiority of rehabilitative treatments in enhancing motor recovery within 6 months poststroke: a systemic review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2019;100:366–378. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2018.09.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hong Z, Sui M, Zhuang Z, et al. Effectiveness of neuromuscular electrical stimulation on lower limbs of patients with hemiplegia after chronic stroke: a systematic review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2018;99:1011–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2017.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vafadar AK, Cote JN, Archambault PS. Effectiveness of functional electrical stimulation in improving clinical outcomes in the upper arm following stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/729768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pereira S, Mehta S, McIntyre A, Lobo L, Teasell RW. Functional electrical stimulation for improving gait in persons with chronic stroke. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2012;19:491–498. doi: 10.1310/tsr1906-491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Busk H, Stausholm MB, Lykke L, Wienecke T. Electrical stimulation in lower limb during exercise to improve gait speed and functional motor ability 6 months poststroke. A review with meta-analysis. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2020;29 doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2019.104565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Howlett OA, Lannin NA, Ada L, McKinstry C. Functional electrical stimulation improves activity after stroke: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96:934–943. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2015.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4:1. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sherrington C, Herbert RD, Maher CG, PEDro Moseley AM. A database of randomized trials and systematic reviews in physiotherapy. Man Ther. 2000;5:223–226. doi: 10.1054/math.2000.0372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Sterne JAC. Chapter 8: assessing risk of bias in included studies. London, England: The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011.

- 38.Deeks JJ, Higgins JPT, Altman DG. Chapter 9: analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. London, England: The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011.

- 39.Higgins JPT, Deeks JJ. Chapter 7: selecting studies and collecting data. London, England: The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011.

- 40.Bernhardt J, Hayward KS, Kwakkel G, et al. Agreed definitions and a shared vision for new standards in stroke recovery research: the Stroke Recovery and Rehabilitation Roundtable taskforce. Int J Stroke. 2017;12:444–450. doi: 10.1177/1747493017711816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brott T, Adams HP, Jr, Olinger CP, et al. Measurements of acute cerebral infarction: a clinical examination scale. Stroke. 1989;20:864–870. doi: 10.1161/01.str.20.7.864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brunnstrom S. Motor testing procedures in hemiplegia: based on sequential recovery stages. Phys Ther. 1966;46:357–375. doi: 10.1093/ptj/46.4.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aitkens S, Lord J, Bernauer E, Fowler WM, Jr, Lieberman JS, Berck P. Relationship of manual muscle testing to objective strength measurements. Muscle Nerve. 1989;12:173–177. doi: 10.1002/mus.880120302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Church C, Price C, Pandyan AD, Huntley S, Curless R, Rodgers H. Randomized controlled trial to evaluate the effect of surface neuromuscular electrical stimulation to the shoulder after acute stroke. Stroke. 2006;37:2995–3001. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000248969.78880.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fletcher-Smith JC, Walker DM, Allatt K. The ESCAPS study: a feasibility randomized controlled trial of early electrical stimulation to the wrist extensors and flexors to prevent post-stroke complications of pain and contractures in the paretic arm. Clin Rehabil. 2019;33:1919–1930. doi: 10.1177/0269215519868834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hochsprung A, Domínguez-Matito A, López-Hervás A, et al. Short- and medium-term effect of kinesio taping or electrical stimulation in hemiplegic shoulder pain prevention: a randomized controlled pilot trial. Neurorehabilitation. 2017;41:801–810. doi: 10.3233/NRE-172190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hsu SS, Hu MH, Wang YH, Yip PK, Chiu JW, Hsieh CL. Dose-response relation between neuromuscular electrical stimulation and upper-extremity function in patients with stroke. Stroke. 2010;41:821–824. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.574160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim TH, In TS, Cho HY. Task-related training combined with transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation promotes upper limb functions in patients with chronic stroke. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2013;231:93–100. doi: 10.1620/tjem.231.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lin Z, Yan T. Long-term effectiveness of neuromuscular electrical stimulation for promoting motor recovery of the upper extremity after stroke. J Rehabil Med. 2011;43:506–510. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Linn SL, Granat MH, Lees KR. Prevention of shoulder subluxation after stroke with electrical stimulation. Stroke. 1999;30:963–968. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.5.963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McDonnell MN, Hillier SL, Miles TS, Thompson PD, Ridding MC. Influence of combined afferent stimulation and task-specific training following stroke: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2007;21:435–443. doi: 10.1177/1545968307300437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Powell J, Pandyan AD, Granat M, Cameron M, Stott DJ. Electrical stimulation of wrist extensors in poststroke hemiplegia. Stroke. 1999;30:1384–1389. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.7.1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rosewilliam S, Malhotra S, Roffe C, Jones P, Pandyan AD. Can surface neuromuscular electrical stimulation of the wrist and hand combined with routine therapy facilitate recovery of arm function in patients with stroke? Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;93:1715–1721. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sahin N, Ugurlu H, Albayrak I. The efficacy of electrical stimulation in reducing the post-stroke spasticity: a randomized controlled study. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34:151–156. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2011.593679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sonde L, Gip C, Fernaeus SE, Nilsson CG, Viitanen M. Stimulation with low frequency (1.7 Hz) transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation (low-tens) increases motor function of the post-stroke paretic arm. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1998;30:95–99. doi: 10.1080/003655098444192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhou M, Li F, Lu W, Wu J, Pei S. Efficiency of Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation And Transcutaneous Nerve Stimulation On Hemiplegic Shoulder Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2018;99:1730–1739. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2018.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gurcan A, Selcuk B, Onder B, Akyuz M. Akbal Yavuz A. Evaluation of clinical and electrophysiological effects of electrical stimulation on spasticity of plantar flexor muscles in patients with stroke. Turk J Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;61:307–313. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tan Z, Liu H, Yan T. The effectiveness of functional electrical stimulation based on a normal gait pattern on subjects with early stroke: a randomized controlled trial. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/545408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang YH, Meng F, Zhang Y, Xu MY, Yue SW. Full-movement neuromuscular electrical stimulation improves plantar flexor spasticity and ankle active dorsiflexion in stroke patients: a randomized controlled study. Clin Rehabil. 2016;30:577–586. doi: 10.1177/0269215515597048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yan T, Hui-Chan CW, Li LS. Functional electrical stimulation improves motor recovery of the lower extremity and walking ability of subjects with first acute stroke: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Stroke. 2005;36:80–85. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000149623.24906.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yavuzer G, Geler-Kulcu D, Sonel-Tur B, Kutlay S, Ergin S, Stam HJ. Neuromuscular electric stimulation effect on lower-extremity motor recovery and gait kinematics of patients with stroke: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;87:536–540. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2005.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.You G, Liang H, Yan T. Functional electrical stimulation early after stroke improves lower limb motor function and ability in activities of daily living. NeuroRehabilitation. 2014;35:381–389. doi: 10.3233/NRE-141129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zheng X, Chen D, Yan T. A randomized clinical trial of a functional electrical stimulation mimic to gait promotes motor recovery and brain remodeling in acute stroke. Behav Neurol. 2018;2018 doi: 10.1155/2018/8923520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gladstone DJ, Danells CJ, Black SE. The Fugl-Meyer Assessment of motor recovery after stroke: a critical review of its measurement properties. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2002;16:232–240. doi: 10.1177/154596802401105171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kwakkel G, Kollen B, Lindeman E. Understanding the pattern of functional recovery after stroke: facts and theories. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2004;22:281–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kwakkel G, Kollen BJ. Predicting activities after stroke: what is clinically relevant? Int J Stroke. 2013;8:25–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2012.00967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lyle RC. A performance test for assessment of upper limb function in physical rehabilitation treatment and research. Int J Rehabil Res. 1981;4:483–492. doi: 10.1097/00004356-198112000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: the Barthel Index. Md State Med J. 1965;14:61–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shah S, Vanclay F, Cooper B. Improving the sensitivity of the Barthel Index for stroke rehabilitation. J Clin Epidemiol. 1989;42:703–709. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(89)90065-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Skilbeck CE, Wade DT, Hewer RL, Wood VA. Recovery after stroke. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1983;46:5–8. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.46.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kwakkel G, Wagenaar RC, Kollen BJ, Lankhorst GJ. Predicting disability in stroke–a critical review of the literature. Age Ageing. 1996;25:479–489. doi: 10.1093/ageing/25.6.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sions JM, Tyrell CM, Knarr BA, Jancosko A, Binder-Macleod SA. Age- and stroke-related skeletal muscle changes: a review for the geriatric clinician. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2012;35:155–161. doi: 10.1519/JPT.0b013e318236db92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hendricks HT, van Limbeek J, Geurts AC, Zwarts MJ. Motor recovery after stroke: a systematic review of the literature. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83:1629–1637. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2002.35473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lohse KR, Lang CE, Boyd LA. Is more better? Using metadata to explore dose-response relationships in stroke rehabilitation. Stroke. 2014;45:2053–2058. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.004695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kwakkel G, van Peppen R, Wagenaar RC, et al. Effects of augmented exercise therapy time after stroke: a meta-analysis. Stroke. 2004;35:2529–2539. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000143153.76460.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]