Abstract

Background

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the leading cause of cancer death. Kinesin family member 2C (KIF2C) has been shown as oncogene in a variety of tumors. However, its role in HCC remains unclear.

Methods

In this study, the expression level of KIF2C in HCC was detected by immunohistochemical staining and RT-PCR, and verified by Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO), The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and Oncomine database. A curve was established to evaluate the diagnostic efficiency of KIF2C. The effect of KIF2C on HCC was investigated by flow cytometry, Cell Counting Kit-8, Transwell, and the wound-healing assay. We explored the underlying mechanism through epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and transcriptome sequences analysis.

Results

KIF2C was overexpression in HCC tissue and related to neoplasm histologic grade (P<0.001), pathology stage (P=0.001), and a dismal prognosis (overall, recurrence-free, and disease-free survival). The diagnostic efficacy of KIF2C was >90% in diagnosing HCC. The HCC cell function experiments showed that KIF2C promoted HCC cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and an accelerated cell cycle, and inhibited apoptosis. Based on western blot analysis and RT-PCR, we found that KIF2C promoted HCC invasion and metastasis through activation of the EMT. Based on transcriptome sequences, we showed that KIF2C promoted HCC through the Ras/MAPK and PI3K/Akt signaling pathway.

Conclusions

KIF2C was found to promote the progression of HCC and is anticipated to serve as a biomarker for HCC diagnosis, prognosis, and targeted therapy.

Keywords: Kinesin family member 2C (KIF2C), hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), Ras/mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway (Ras/MAPK signaling pathway), biomarker

Introduction

In 2018, there were over 800,000 new cases of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and 780,000 deaths worldwide, with HCC ranking seventh and third among all tumors, respectively (1). More than 90% of liver cancers are HCCs. HCC is one of the most common malignant tumors leading to cancer deaths, especially in East Africa, the Asia-Pacific region, and China (2,3). Hepatitis B and C virus infections, alcohol abuse, aflatoxin B1 exposure, and metabolic liver disease are risk factors for HCC (4). HCC heterogeneity is extremely strong due to complex genomic changes and abnormal signaling pathway activation, which reduces the efficacy of treatment, although traditional surgical treatment and emerging targeted therapy and immunotherapy play active roles (5,6). For these reasons, early diagnosis, individualized treatment, and prognostic assessment of HCC patients have become challenging, ultimately resulting in poor prognosis, with a 5-year survival rate of 15% (7). Therefore, it is important to search for new biomarkers and therapeutic targets, and elucidate the underlying pathogenesis related to the development, invasion, and metastasis of HCC.

More than 40 members in the kinesin superfamily genes (KIFs) are divided into 14 subfamilies (8). KIFs consist of 2 heavy and 2 light chains that possess molecular motor activity and regulate substance binding (9). KIF proteins are essential for molecular motor functions, and their role in transporting organelles, vesicles, mRNA, and proteins along microtubules has been demonstrated (10,11). Moreover, KIFs are involved in mitotic spindle and chromosome activities during cell division (12,13). Kinesin family member 2C (KIF2C), also known as mitotic centromere-associated kinesin, belongs to the kinesin-13 family. KIF2C-encoded proteins participate in microtubule depolymerization, therefore facilitating the separation of chromosomes during mitosis, which is of significance during cell division (14,15).

KIFs have been reported to be associated with many diseases. According to previous studies, KIFs are associated with neurological and metabolic diseases, such as epilepsy, intellectual disability, neuronal dysfunction, hypercholesterolemia, and diabetes (8,16-18).

KIFs, especially KIF2C, are also related to a variety of malignancies. KIF2C is overexpressed in breast, lung, and bladder cancers (19-21). The level of KIF2C expression is associated with tumor stage, sarcoma grade, lymph node metastasis, and prognosis (22-24). Although the innate mechanism underlying KIF2C has not been completely elucidated, there is sufficient evidence to suggest that KIF2C is an oncogene.

Some hub genes, such as telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT), tumor protein 53 (TP53), have been found to be HCC oncogenes, and can contribute to the occurrence and progression of HCC by promoting proliferation, cell cycle progression, and abnormal angiogenesis (25,26). Interestingly, KIF2C acts as a molecular motor during mitosis to facilitate chromosome separation, which is a critical process during the cell cycle and proliferation. KIF2C can promote the occurrence and development of HCC. Previous studies have screened out some genes, including KIF2C, through bioinformatics tools that can serve as key genes associated with HCC (27,28). One study indicated that the overexpression of KIF2C promotes HCC progression by connecting mammalian target of rapamycin 1 and Wnt/β-catenin signaling (29). However, the relationship between KIF2C and HCC metastasis like epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), transcriptome sequencing analysis, and the other underlying molecular mechanisms remain unclear.

Previous studies have shown that EMT was a biological process through which epithelial cells transdifferentiate into mesenchymal cells could lead to cancer progression and organ fibrosis (30). Studies have shown that KIF2C leaded to EMT and promotes invasion and metastasis in transformed human bronchial epithelial cells, but the role of KIF2C in EMT of HCC remains unclear (31). In the present study, we determined the level of KIF2C expression in HCC and non-tumor tissues, and the correlation between KIF2C expression and clinical variables, such as prognosis, tumor stage, tissue grade, and microvascular invasion. In vitro experiments were conducted to determine the relationship between silencing and overexpression of KIF2C on proliferation, invasion, metastasis, the cell cycle, apoptosis, and EMT markers of HCC cells. Transcriptome sequencing was used to screen out the potential mechanism by which KIF2C promotes HCC development. We present the following article in accordance with the MDAR reporting checklist (available at https://atm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/atm-21-6240/rc).

Methods

Cell culture and lentivirus infection

Since two human HCC cell lines (Hep3B and Huh7) were widely used and representative in various HCC studies, they were purchased from the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). We cultured the 2 cell lines using Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (Gibco, CA, USA) with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, USA) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin solution (Gibco, CA, USA) at 37 °C in a humidified incubator containing 5% CO2. Cell line authenticity was confirmed by genotyping (Figure S1A,S1B).

To establish a stable cell line and intervene the expression of KIF2C, lentiviral vectors and short hairpin RNA (shRNA; shRNA-1: 5'-GCCCACTGAATAAGCAAGAAT-3'; shRNA-2: 5'-GCCCGAATGATTAAAGAATTT-3'; and shRNA-3: 5'-GCACTGAATGTCTTGTACTTT-3') targeting KIF2C (NM_006845) were obtained from GeneChem (Shanghai, China). Cells were transfected and underwent sterility testing with lentivirus, strictly following the manufacturer’s instructions (GeneChem, China) (32). Lentivirus vectors were as follows: LV-KIF2C, Ubi-MCS-3FLAG-CBh-gcGFP-IRES-puromycin (Figure S1C); and shRNA vector, hU6-MCS-ubiquitin-EGFP-IRES-puromycin (Figure S1D).

Patients and specimens

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by the ethics committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University [approval number: 2021(KE-E-272)] and informed consent was taken from all the patients. We collected fresh samples from 76 patients at the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University from 2013 to 2014, including both cancerous and matched non-cancerous tissues. All patients underwent hepatectomy, had not received preoperative therapy, and were pathologically diagnosed with HCC. Tissue specimens were obtained during surgery and immediately preserved at –80 °C. Subsequent real-time polymerase chain reactions (RT-PCRs) of KIF2C were performed.

KIF2C expression verification and survival analysis

The level of KIF2C expression was measured by the Oncomine database (http://www.oncomine.com/), and included 225 HCC and 220 normal cases. The GSE14520 dataset from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) datasets was used for analysis, which we have previously reported (33,34). For additional patients, more comprehensive information, and avoidance of the batch effect, the GPL3921 platform was used for further analysis. The expression profiles of KIF2C were extracted from the Metabolic gEne RApid Visualizer (MERAV; http://merav.wi.mit.edu/) database, and the expression of KIF2C in cancer cell lines, HCC, and normal tissues was compared using a raw matrix. The Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis (GEPIA; http://gepia.cancer-pku.cn/index.html) website, which matches The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA; https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov) normal and GTEx data, and Kaplan-Meier Plotter (https://kmplot.com/) were used to evaluate the level of KIF2C expression and the relationship between KIF2C and prognosis. Corresponding clinical variables and expression files were obtained from TCGA. The following criteria were established to screen for high-quality data from TCGA: (I) pathological diagnosis was HCC; (II) availability of the expression profile; and (III) complete clinical variables. According to the level of KIF2C expression in HCC and non-HCC tissues, the diagnostic efficiency of KIF2C was determined based on a receiver-operating characteristic curve, which was constructed using the pROC package in R (https://www.r-project.org/), and the value of the area under the curve (AUC) represented diagnostic efficiency.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining

We collected 20 HCC and adjacent non-tumor liver tissues from patients undergoing hepatobiliary surgery at the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University. All of the tissues were pathologically confirmed to be HCC and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight and embedded in paraffin. Sections were deparaffinized with xylene and hydrated with graded alcohols. Subsequently, the sections were incubated with 3% H2O2 for 10 min at 37 °C and washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The sections were then incubated with 50 µL of rabbit monoclonal anti-KIF2C antibody (Abcam, USA) at 4 °C overnight. The dilution ratio of the antibody was dependent on the recommended dilution ratio in the specifications. Next, the sections were incubated with PV-6001 (ZSBG, Beijing, China) for 30 min at 25 °C. Finally, we stained the slices with 3,3'-diaminobenzidine and hematoxylin for detection. A positive reaction was defined as cytoplasm showing a brown signal. The degree of immunostaining was performed independently by 2 experienced pathologists. The immunostaining score depended on the percentage of positive cells (range: 0–4%; 0, <5%; 1%, 5–25%; 2%, 25–50%; 3%, 51–75%; and 4%, >75%) multiplied by the immunostaining intensity (range: 0–4; 0, non-staining; 1, low intensity; 2 median intensity; and 3, high intensity) (35).

Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR)

We used TRIzol reagent (Solarbio, China) to extract total RNA from cells, and transcribed into complementary DNA. Subsequently, SYBR green PCR Master Kit (QIAGEN, Germany) was used for RT-PCR. The primer sequence was designed and showed in Table S1. The reaction conditions of qRT-PCR were as follows: initial heat activation 95 °C for 2 min and denaturation at 95 °C for 5 s, consecutively followed by 40 cycles of 60 °C for 30 s and a final extension step. The level of RNA expression was determined by the original Ct value and the 2–∆∆Ct method (36).

Western blotting

We used RIPA lysis buffer (Beyotime, China) to lyse Hep3b and Huh7 cells for total protein extraction. We diluted the total protein solution with a gradient and measured the protein concentration using the bicinchoninic acid method. The protein solution at a specific concentration was prepared according to the reagent instructions. Ten micrograms of internal control protein and 30 µg of the specimen protein were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gel and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes. The PVDF membrane was blocked for 1 h and washed 3 times with tris-buffered saline and Tween 20. The membrane was incubated with primary antibody at 4 °C overnight, then incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled secondary antibody and continuously shaken for 1 h. The antibodies used were as follows: HRP-conjugated GAPDH (HRP-60004; Proteintech, USA); HRP-linked anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) (7076P2; CST, USA); HRP-linked antirabbit IgG (7074S; CST, USA); anti-E-cadherin (ab40772; Abcam, UK); anti-N-cadherin (ab76011; Abcam, UK); Slug rabbit monoclonal antibody (mAb; 9585T; CST, USA); Snail rabbit mAb (3879T; CST, USA); and anti-Vimentin (ab92547; Abcam, UK) (35). The results were analyzed using Image J software.

Cell proliferation, and migration and invasion assay

The stably transfected Hep3b and Huh7 cells were divided into different groups and seeded onto a 96-well plate at a density of 5×104 cells/mL. We used the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8 Kit; Dojindo, Japan), based on the manufacturer’s instructions, to determine the proliferative capacity of cells. Optical density (OD) values were obtained at 450 nm after 24, 48, 72, 96, and 120 h.

A transwell cell migration and invasion assay was used to test the ability of cells to invade and metastasize. The cell density of different groups was adjusted to 2×105 cells/mL, and 100 µL cell suspension of different groups were added to the upper chamber with or without Matrigel (Corning, USA). The cells were cultured for 48 h in a humidified incubator containing 5% CO2 at 37 °C. The cells were them removed, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min, washed 3 times with PBS, stained with 1% crystal violet for 30 min, and rewashed with PBS. Each sample was viewed and photographed under a microscope in 5 fields. Crystal violet was eluted with 300 µL of 33% acetic acid, and 100 µL cell suspension of different groups were added to each of the 96-well plates. OD value at 590 nm was determined.

Wound-healing assay

We planted the Huh-7 and HepG3 cell lines (1×105 cells/well) onto 12-well plates. When the cell confluence reached 100%, a pipette tip was used to scratch the center of the well. After washing the cells 3 times with PBS, the cells were cultured and photographed after 0, 24, and 72 h. Image J software was used to calculate the area of the blank space.

Flow cytometry assay

To assess the effect of gene expression on the cell cycle, cells were centrifuged, fixed with ethanol, and washed with PBS; 500 µL of PI/RNase dye (BD Biosciences, USA) was then added. The cells were incubated in darkness for 15 min, and then the cells were analyzed by flow cytometry (BD Accuri C6 Plus; BD Biosciences, USA).

To assess the effect of gene expression on cell apoptosis, cells were centrifuged and resuspended in 50 µL 1× binding buffer. Then, 5 µL of Annexin V-APC and 10 µL of 7-AAD (MultiSciences Biotech, China) were added to the cells, which were then incubated in the dark at 25 °C for 25 min. The cells were immediately analyzed by flow cytometry.

RNA-sequencing and enrichment analysis

Negative control (NC) and shRNA groups of Huh-7 stably transfected cells were sent to BGI (Shenzhen, China) for further RNA-sequencing detection. The sequencing file was filtered and analyzed on the BGISEQ-500 platform (BGI, Shenzhen, China); known and novel coding and non-coding transcripts were included. We then used DESeq2 for the differential expression analysis, and |log fold change (FC)| >2 and an adjusted Q-value of <0.05 were considered to represent differentially expressed genes (DEGs). To further elucidate a change in the underlying mechanism, the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway was analyzed by phyper, based on hypergeometric testing with the Dr. Tom network platform of BGI (http://report.bgi.com). The interaction network of KIF2C to other genes or proteins was acquired from the Dr. Tom network platform and Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins (https://string-db.org/) or Gene Multiple Association Network Integration Algorithm (http://genemania.org).

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses used in the present study were performed using SPSS version 22.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA); P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. R (version 3.6.3) and GraphPad Prism (version 8.0.1) were used to create statistical graphics; χ2 test or rank sum test was used to assess statistical differences between multiple groups. Survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan-Meier method with a log-rank test. A 2-group comparison was performed using Student’s t-test. All data in this study are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (n=3).

Results

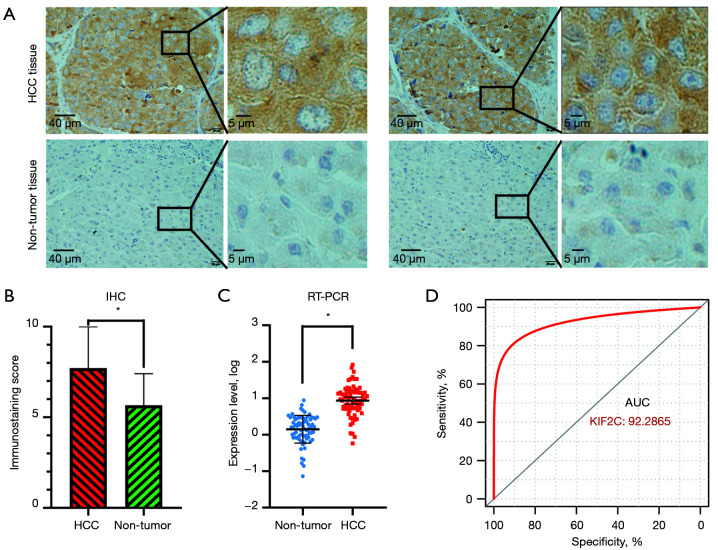

KIF2C overexpression in HCC

We first assessed the expression of KIF2C in HCC and non-tumor tissues. IHC based on 20 HCCs and an adjusted non-cancer tissues microarray indicated that the KIF2C protein was upregulated in HCC tissues (t=3.172, P=0.003) (Figure 1A,1B). To further confirm that the level of KIF2C expression was significantly increased in HCC, 76 samples were detected by RT-PCR (Figure 1C). The AUC of KIF2C in diagnosing HCC was 0.9229 (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

The expression level of KIF2C in HCC. (A) Representative IHC staining for KIF2C protein expression in 20 HCC and adjacent non-cancerous tissues. (B) Statistical analysis of KIF2C protein expression in 20 patients based on IHC staining. (C) mRNA expression of KIF2C in 76 paired HCC and adjacent non-cancerous tissues based on real-time polymerase chain reaction analysis. (D) Diagnostic receiver-operating characteristic curves for KIF2C in 76 paired HCC and adjacent non-cancerous tissues. *, P<0.05. KIF2C, kinesin family member 2C; IHC, immunohistochemical; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; AUC, area under the curve.

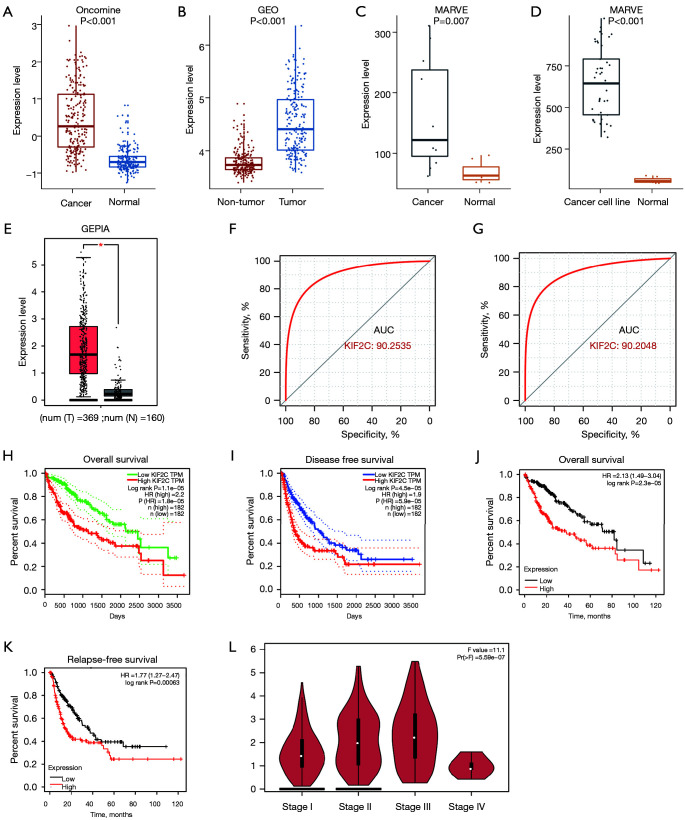

Differential expression of KIF2C verification and prognostic analysis

Next, we used public databases to verify the overexpression of KIF2C in HCC and evaluated the relationship between KIF2C and prognosis. In total, 225 HCC and 220 normal cases in the Oncomine database were obtained, and KIF2C was overexpressed in HCC tissue (Figure 2A). The same results were observed in the GEO databases, which included 212 HCC and 204 non-tumor tissues (Figure 2B). In the MERAV database, the expression of KIF2C in both HCC tissues and cancer cell lines were upregulated (Figure 2C,2D). In the GEPIA databases, the level of KIF2C expression was higher in HCCs compared with normal tissues (Figure 2E). KIF2C was found to have extremely high diagnostic performance, with an AUC of 0.9025 in the GEO and 0.9020 in the Oncomine databases (Figure 2F,2G). Survival analysis according to the GEPIA and Kaplan-Meier Plotter websites suggested that high KIF2C expression groups had poor overall survival, disease-free survival, and relapse-free survival (Figure 2H-2K). The higher the tumor stage, the higher the level of KIF2C expression, except stage IV (Figure 2L). Based on TCGA, KIF2C was significantly correlated with pathological stage (P=0.001) and neoplasm histological grade (P<0.001) (Table 1). The higher the level of KIF2C expression, the higher the 8th American Joint Committee on Cancer stage and neoplasm histological grade. KIF2C was overexpressed in nearly all tumors (Figure S2A).

Figure 2.

Clinical analysis and expression of KIF2C in HCC based on database. (A-E) Level of KIF2C expression in Oncomine, GEO, MERAV tissue, MERAV HCC cell line, and GEPIA datasets, respectively. (F,G) Diagnostic receiver-operating characteristic curves for KIF2C in GEO and Oncomine datasets. (H,I) Survival curves in GEPIA. (J,K) Survival curves in Kaplan-Meier Plotter website. (L) Relationship between KIF2C and HCC stage from GEPIA. *, P<0.05. KIF2C, kinesin family member 2C; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; GEO, Gene Expression Omnibus; MERAV, Metabolic gEne RApid Visualizer; GEPIA, Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis; AUC, area under the curve; TPM, transcripts per million; HR, hazard ratio.

Table 1. Correlation analysis of KIF2C gene expression level and patient clinical characteristics in The Cancer Genome Atlas database.

| Variable | All cases (n=358) | KIF2C expression level | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low expression | High expression | |||

| Age (years) | 0.026 | |||

| ≤60 | 172 | 75 | 97 | |

| >60 | 186 | 103 | 83 | |

| Sex | 0.132 | |||

| Female | 242 | 127 | 115 | |

| Male | 116 | 51 | 65 | |

| Child-Pugh classa | 0.622 | |||

| A | 209 | 112 | 97 | |

| B | 22 | 13 | 9 | |

| Alcohol historyb | 0.732 | |||

| No | 223 | 110 | 113 | |

| Yes | 117 | 60 | 57 | |

| Hepatitis virusc | 0.303 | |||

| No | 94 | 51 | 43 | |

| Yes | 256 | 123 | 133 | |

| Vascular invasiond | 0.235 | |||

| No | 199 | 109 | 90 | |

| Yes | 103 | 49 | 54 | |

| Pathological stagee | 0.001 | |||

| I | 165 | 96 | 69 | |

| II | 81 | 36 | 45 | |

| III + IV | 88 | 33 | 55 | |

| Neoplasm histological gradef | <0.001 | |||

| G1 | 53 | 38 | 15 | |

| G2 | 169 | 91 | 78 | |

| G3 + G4 | 131 | 47 | 84 | |

| Cirrhosisg | 0.687 | |||

| No | 72 | 29 | 43 | |

| Yes | 139 | 60 | 79 | |

| Radical resectionh | 0.154 | |||

| R0 | 315 | 162 | 153 | |

| R1/Rx | 36 | 14 | 22 | |

a, Child-Pugh class was unavailable for 127 patients; b, alcohol history was unavailable for 18 patients; c, hepatitis virus was unavailable for 8 patients; d, vascular invasion was unavailable for 56 patients; e, pathological stage was unavailable for 24 patients; f, neoplasm histological grade was unavailable for 5 patients; g, cirrhosis was unavailable for 147 patients; h, radical resection was unavailable for 7 patients. KIF2C, kinesin family member 2C.

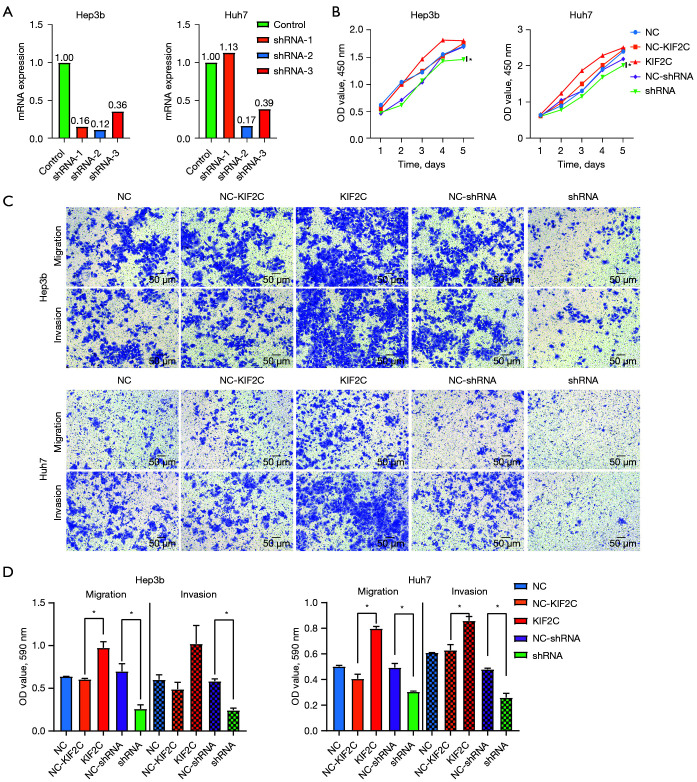

Evaluating the silencing efficacy of shRNA

qRT-PCR was used to detect the efficacy of 3 shRNAs silencing KIF2C in Hep3b and Huh7 HCC cell lines. In both cell lines, shRNA-2 had the best silencing efficacy (0.12 and 0.17 in Hep3b and Huh7, respectively) by qRT-PCR (Figure 3A). Therefore, shRNA-2 was used for further functional experiments. The ability of lentiviral infection to overexpress KIF2C was confirmed in Figure S2B.

Figure 3.

Results of cell proliferation, migration and invasion in HCC. (A) Real-time polymerase chain reaction results for KIF2C expression in Hep3b and Huh7 cell lines with different shRNAs. (B) Growth curves for Hep3b and Huh7 cell lines based on the Cell Counting Kit-8 assay and expressed as OD values. (C,D) Representative images and statistical analysis of transwell migration and invasion assays in different groups and cell lines expressed as OD values (crystal violet staining; scale bar, 50 µm). *, P<0.05. KIF2C, kinesin family member 2C; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; NC, negative control; shRNA, short hairpin RNA; OD, optical density.

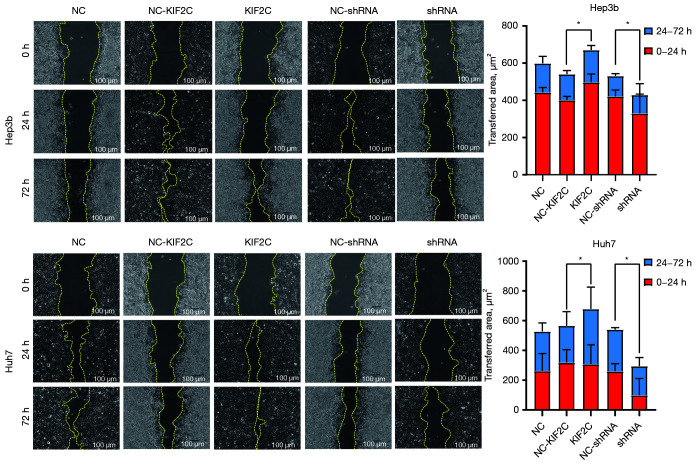

Downregulation of KIF2C inhibits proliferation, migration, and invasion of HCC cells

According to the results of the CCK-8 assay, changing the level of KIF2C expression changed the proliferative ability of HCC cells. KIF2C suppression significantly reduced the proliferative ability of HCC cells (Figure 3B). Transwell cell migration and invasion assay indicated that the overexpression of KIF2C promoted metastasis and invasion of HCC cells, while the suppression of KIF2C had the opposite result (Figure 3C,3D). Similar results were obtained with the wound-healing assay, indicating that the upregulation of KIF2C elevated migration activity, and the downregulation of KIF2C slowed migration activity (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Representative images and statistical analysis of wound-healing assay in different groups and cell lines. Scale bar, 100 µm. *, P<0.05. KIF2C, kinesin family member 2C; NC, negative control; shRNA, short hairpin RNA.

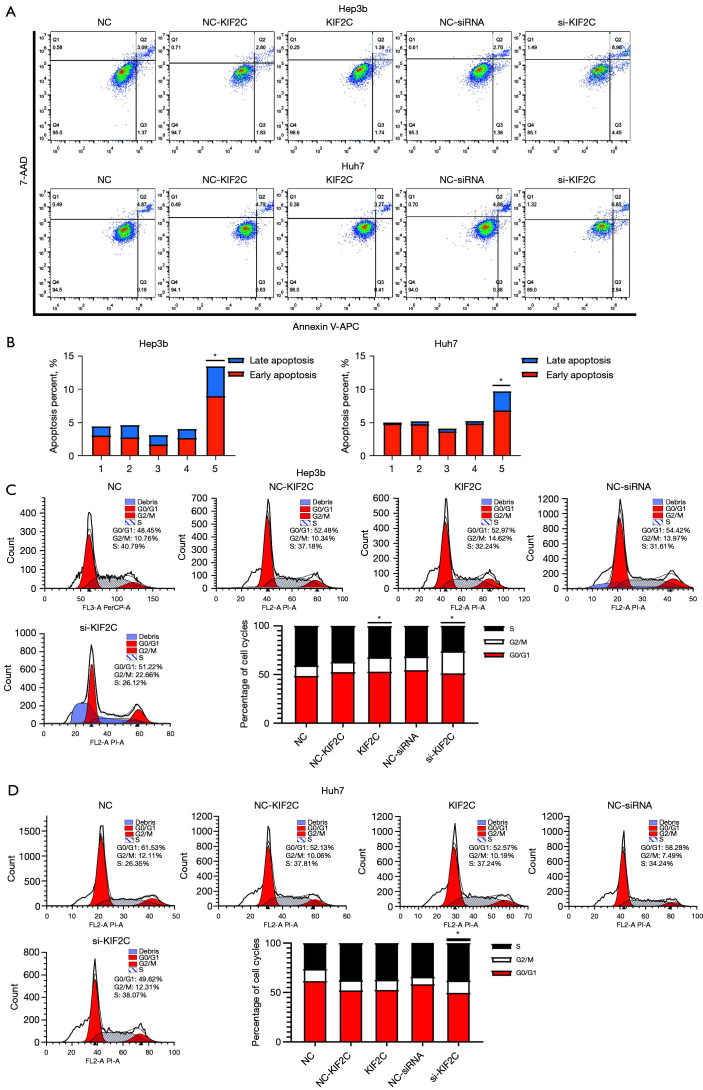

Suppressing KIF2C accelerates HCC cell apoptosis and prolongs the cell cycle

Cell apoptosis and the cell cycle are important in tumor progression. The relationship with KIF2C was ascertained using a flow cytometry assay. The results showed that the upregulation of KIF2C promoted the growth of HCC cells and reduced apoptosis (Figure 5A,5B). Suppressing KIF2C caused the percentage of G2/M phase cells to increase (P<0.001), and KIF2C inhibited cell mitosis and led to a prolonged cell cycle (Figure 5C,5D).

Figure 5.

Results of cell cycle and apoptosis assay. (A,B) Number of apoptotic cells in each group and cell line detected by flow cytometry assay and statistical analysis. (C,D) Cell cycle distribution in each group calculated by flow cytometry assay and statistical analysis in Hep3b and Huh7 cell lines, respectively. *, P<0.05. KIF2C, kinesin family member 2C; NC, negative control; shRNA, short hairpin RNA.

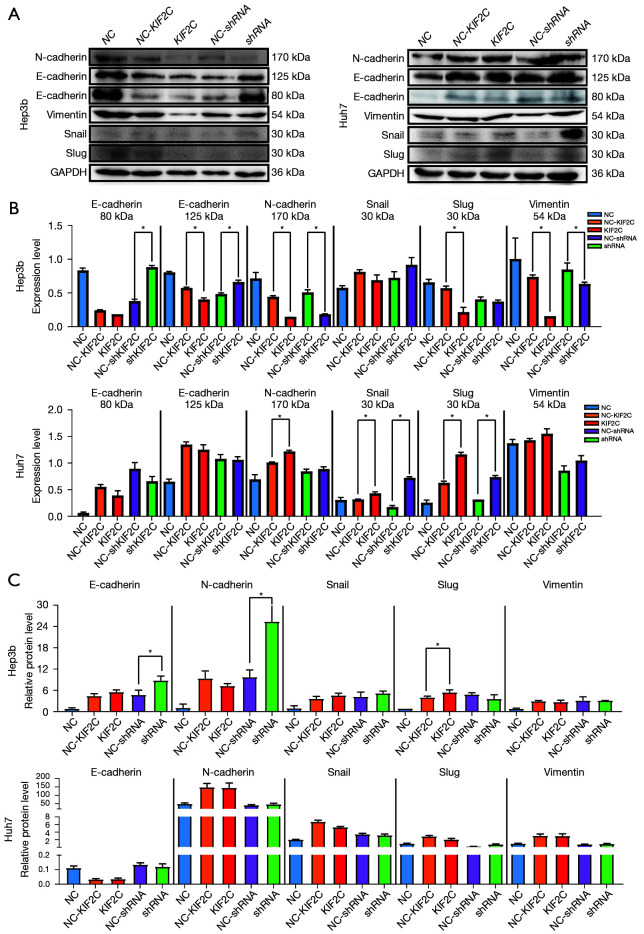

EMT in HCC cells

The biological processes of tumor cell invasion and metastasis were shown to be related to EMT and Western blot analysis; qRT-PCR was used to determine whether KIF2C promotes metastasis and invasion of HCC cells via EMT. E-cadherin was found at 80 and 125 kDa respectively, while N-cadherin was found at 170 kDa. The downregulation of KIF2C was characterized by the high expression of E-cadherin and low expression of N-cadherin and Vimentin in Hep3b cells (Figure 6A,6B, Figure S3A,3B). Overexpression of KIF2C in Huh7 cells was related to the high expression of N-cadherin and Slug. Based on qRT-PCR, the level of E-cadherin and N-cadherin were upregulated when KIF2C was downregulated in Hep3b (Figure 6C). E-cadherin exhibits anti-EMT activity and N-cadherin, Snail, Slug, and Vimentin are pro-EMT. In short, KIF2C regulated the metastasis and invasion of HCC cells through EMT.

Figure 6.

Expression of the epithelial proteins in HCC cells were detected by Western blot and PCR analysis. (A,B) Levels of E-cadherin, N-cadherin, Snail, Slug, and Vimentin expression was compared by Western blot analysis in Hep3b and Huh7 cell lines. (B) Corresponding statistical analysis. (C) Levels of E-cadherin, N-cadherin, Snail, Slug, and Vimentin expression were compared by real-time polymerase chain reaction in Hep3b and Huh7 cell lines. *, P<0.05. KIF2C, kinesin family member 2C; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; NC, negative control; shRNA, short hairpin RNA.

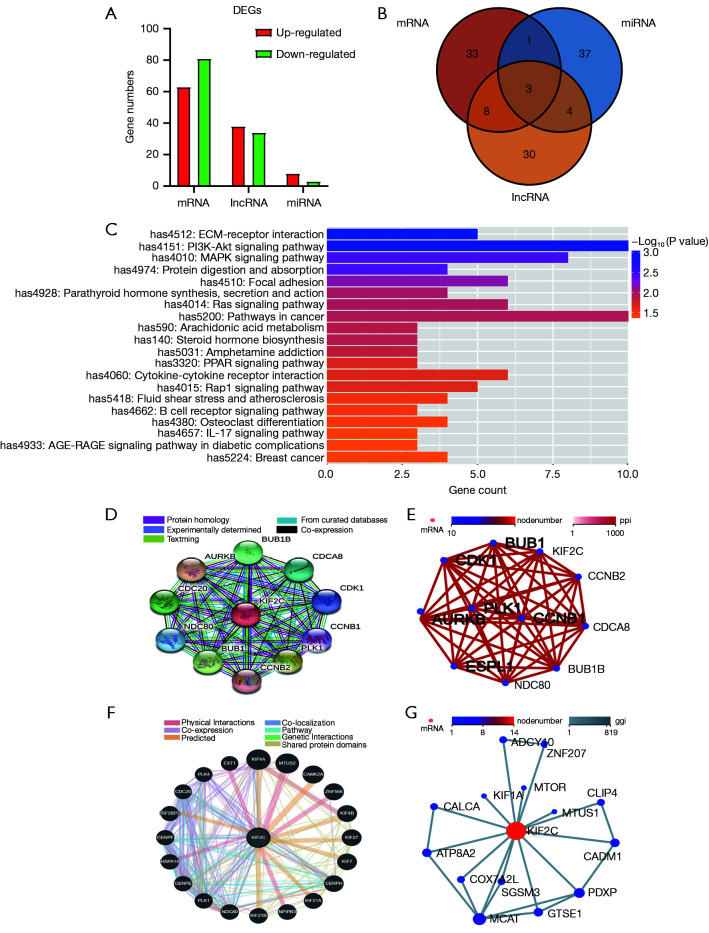

Transcriptome sequence analysis and interaction network

To further explore the potential mechanism underlying KIF2C to promote the progression of HCC, we analyzed the differences in the transcriptome between the si-KIF2C and control groups. In total, 144 mRNAs were differentially expressed, of which 63 were upregulated and 81 were downregulated. Seventy-two long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) were DEGs and 34 and 38 lncRNA were downregulated and upregulated, respectively. Three miRNAs were downregulated and 8 miRNAs were upregulated (Figure 7A). Based on the enrichment of differentially expressed mRNAs, lncRNA target genes, and miRNA-targeted mRNA genes, the leading 45 KEGG pathways that were enriched were selected according to the enrichment results of KEGG from small to large P values (Tables S2-S4). Finally, the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway, Ras signaling pathway, and colorectal cancer were all enriched in 3 enrichment analyses (Figure 7B). Phospha-tidylinositol-3 kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (Akt) signaling pathway was one of the potential pathways (Figure 7C). Protein interaction networks showed that KIF2C interacts with BUB1B, CDCA8, CDK1, CCNB1, CCNB2, PLK1, AURKB, and NDC80, which were reported to be associated with HCC (Figure 7D,7E) (37-39). The results of the gene-to-gene interaction are shown in Figure 7F,7G.

Figure 7.

The potential mechanism of KIF2C in HCC and interaction network. (A) Number of DEGs between shRNA and control group. (B) Intersection of mRNA, long non-coding RNA, and miRNA-enriched Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) signaling pathways. (C) Top 20 enrichment KEGG pathways based on differentially expressed mRNA from small to large according to P value. (D,E) Interaction network for KIF2C and other proteins. (F,G) Interaction network for KIF2C and other genes. LncRNA, long non-coding RNA; KIF2C, kinesin family member 2C; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; ECM, extracellular matrix; DEGs, differentially expressed genes.

Discussion

Generally, most HCC patients are first diagnosed at an advanced stage and have intra- or extra-hepatic metastases, which affect the therapeutic effect and result in a poor prognosis (40). Recent studies have indicated that targeted molecular therapies, such as sorafenib and lenvatinib, relieve pain and improve prognosis, but only a fraction of patients benefit because therapeutic targets are limited due to genetic alterations of HCC being complicated and multifaceted (40). Therefore, there is an urgent need to explore the mechanism underlying HCC and search for new biomarkers.

In our study, we first proposed that KIF2C promotes the development of HCC through the Ras/MAPK signaling pathway by detecting transcriptome changes between the KIF2C silent and control groups based on KEGG enrichment analysis. Moreover, based on qRT-PCR and IHC, we found that KIF2C was overexpressed in HCC, and public databases confirmed our findings. At the same time, KIF2C was correlated with clinical factors, such as pathological stage and histopathological grade, and patients in the high KIF2C expression group had a worse prognosis. KIF2C was shown to be highly effective in the diagnosis of HCC. Based on in vitro experiments, the overexpression of KIF2C promoted cell proliferation, migration, and invasion, and accelerated the cell cycle, and inhibited apoptosis. Using RT-PCR and Western blotting assay, we found that the upregulation of KIF2C promoted the invasion and metastasis of tumor cells by changing the level of EMT expression. Finally, the Ras/MAPK signaling pathway was the main mechanism by which KIF2C promotes tumorigenesis and the progression of HCC.

The oncogenic role of KIF2C has been widely reported. In lung adenocarcinoma, KIF2C is overexpressed and associated with poor overall survival (41). KIF2C promotes transition from a low-grade glioma to secondary glioblastoma, increases the risk of early death, and is related to susceptibility to chemotherapy for secondary glioblastoma (42). High KIF2C expression in male patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma is associated with worse overall survival, and even with the same pathological TNM stage, patients with high KIF2C expression had a worse outcome (43). Similar results have indicated that KIF2C promotes breast cancer, prostate cancer, and thyroid carcinoma (44-46). In our study, KIF2C was also upregulated in HCC tissues and was associated with a poor outcome. KIF2C promotes HCC cell proliferation, migration, and metastasis, accelerates the cell cycle, and inhibits apoptosis. The above cell functional experiments explain why upregulation of KIF2C leads to early recurrence and death in patients. Previous studies have also added to the credibility of our study (29,47). These finding indicate that KIF2C is an oncogenic gene and a promising biomarker for the diagnosis and prognosis of HCC.

EMT is a key process in tumor migration and distant metastases (48). The mechanism underlying KIF2C promotion of invasion and metastasis was found to be related to EMT by detecting the relationship of KIF2C expression and epithelial and mesenchymal markers of EMT in HCC cells. Changes in these markers indicate that KIF2C could promote the invasion and metastasis of HCC cells through EMT. It has been reported that a novel, orally bioavailable compound (VS 8) significantly upregulates E-cadherin and downregulates Vimentin, and that VS 8 promotes apoptosis of HCC cells (49). Moreover, rapamycin was found to effectively reduce the expression of N-cadherin and enhanced the expression of E-cadherin by reducing the expression of BUB1B, therefore inhibiting EMT (37). Therefore, KIF2C could be a target for the treatment of HCC by inhibiting EMT, but more functional studies and clinical trials are needed to confirm this.

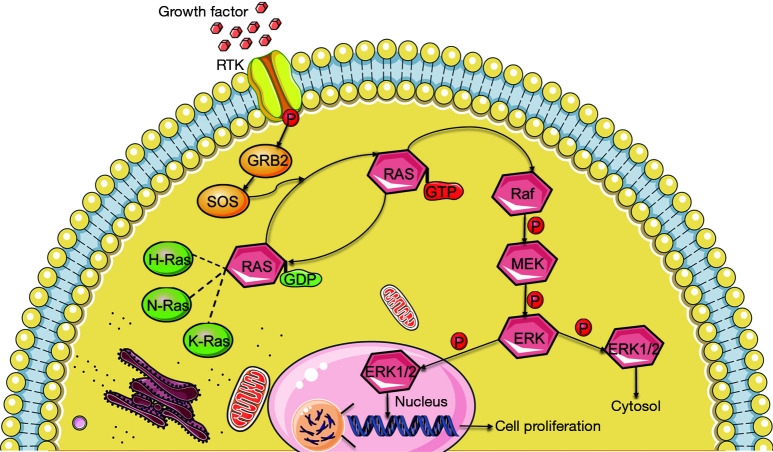

Cell proliferation is one of the most important mechanisms for HCC progression and the Ras-Raf-mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK)-extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)-MAPK (Ras/MAPK) signaling pathway is one of the major molecular classes of HCC (Figure 8) (50). A number of studies have also demonstrated that HCC tumorigenesis and progression are related to the Ras/MAPK signaling pathway (51). Hepatitis B and C viruses are known risk factors for HCC and can activate the Ras/MAPK signaling pathway through Hepatitis B virus regulatory X (HBx) and the hepatitis C virus (HCV) core protein, resulting in hepatocarcinogenesis (52,53). The MAPK signaling pathway transduces signals from cell surface receptors to the nucleus and activates biological processes. Most of the MAPK signaling pathway is activated depending on the GTPase-mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase (MEKK)-MEK-MAPK axis (54).

Figure 8.

Schematic representation of mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade activation. ERK1/2, extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2; MEK, mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase; RTK, receptor tyrosine kinase.

The Ras protein belongs to the small GTPases family and is activated by various extracellular stimuli; the ERK1/2 pathway, which belongs to the MAPK pathway superfamily, is then activated (54). In addition, the level of Ras/MAPK signaling pathway marker expression, such as PAN-Ras, Raf-1, and phosphorylated MEK1, is correlated with poor prognosis in HCC patients (55). In a study of lung cancer cell lines, suppressing KIF2C inhibits the migration and invasion of tumor cells (31). Importantly, in the transformed model, knocking down K-Ras or inhibiting the activation of ERK1/2 reduces KIF2C expression, which also suggests that KIF2C could be considered a new alternative cancer drug target (31). Inhibitors of the Ras/MAPK signaling pathway or its upstream and downstream targets have been developed, such as imatinib, sorafenib and gefitinib (56).

Based on this, we suggest that the KIF2C oncogene promotes HCC generation and progression through the Ras/MAPK and PI3K/Akt signaling pathway, providing a new biomarker for the treatment of HCC patients. Previous studies further strengthen the credibility of our findings (29).

There were some drawbacks to the present study. First, there was a lack of a clinical cohort to assess the relationship between KIF2C and clinical variables. Second, we need to confirm the effect of KIF2C in in vivo experiments. Third, more functional experiments are needed to clarify the mechanism of KIF2C regulating Ras/MAPK.

We found that KIF2C is an oncogene in HCC and is highly expressed in HCC tissues. High expression of KIF2C can promote tumorigenesis, progression, migration, and invasion, and accelerate the cell cycle, and inhibit cell apoptosis through the Ras/MAPK and PI3K/Akt signaling pathway and activate the EMT, all of which indicate poor prognosis. KIF2C is an anticipated biomarker for HCC diagnosis, prognosis, and targeted therapy.

Supplementary

The article’s supplementary files as

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant Nos. 81802874, 81560535, 81802874, 81072321, 30760243, 30460143 and 30560133); the Natural Science Foundation of the Guangxi Province of China (grant No. 2018 GXNSFBA138013); the Guangxi Key R&D Program (No. GKEAB18221019); the Key Laboratory of High-Incidence-Tumor Prevention & Treatment (Guangxi Medical University); Ministry of Education (No. GKE2018-01).

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by the ethics committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University [approval number: 2021(KE-E-272)] and informed consent was taken from all the patients.

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the MDAR reporting checklist. Available at https://atm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/atm-21-6240/rc

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://atm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/atm-21-6240/dss

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://atm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/atm-21-6240/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

(English Language Editor: R. Scott)

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:394-424. 10.3322/caac.21492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Qi Z, Yan F, Chen D, et al. Identification of prognostic biomarkers and correlations with immune infiltrates among cGAS-STING in hepatocellular carcinoma. Biosci Rep 2020;40:BSR20202603. 10.1042/BSR20202603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wallace MC, Preen D, Jeffrey GP, et al. The evolving epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma: a global perspective. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;9:765-79. 10.1586/17474124.2015.1028363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang JD, Hainaut P, Gores GJ, et al. A global view of hepatocellular carcinoma: trends, risk, prevention and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;16:589-604. 10.1038/s41575-019-0186-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Villanueva A. Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2019;380:1450-62. 10.1056/NEJMra1713263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tanaka S, Arii S. Molecular targeted therapies in hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Oncol 2012;39:486-92. 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2012.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bosetti C, Turati F, La Vecchia C. Hepatocellular carcinoma epidemiology. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2014;28:753-70. 10.1016/j.bpg.2014.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hirokawa N, Tanaka Y. Kinesin superfamily proteins (KIFs): Various functions and their relevance for important phenomena in life and diseases. Exp Cell Res 2015;334:16-25. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2015.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang JT, Laymon RA, Goldstein LS. A three-domain structure of kinesin heavy chain revealed by DNA sequence and microtubule binding analyses. Cell 1989;56:879-89. 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90692-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirokawa N, Takemura R. Molecular motors and mechanisms of directional transport in neurons. Nat Rev Neurosci 2005;6:201-14. 10.1038/nrn1624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hirokawa N. Kinesin and dynein superfamily proteins and the mechanism of organelle transport. Science 1998;279:519-26. 10.1126/science.279.5350.519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wordeman L. How kinesin motor proteins drive mitotic spindle function: Lessons from molecular assays. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2010;21:260-8. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2010.01.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cross RA, McAinsh A. Prime movers: the mechanochemistry of mitotic kinesins. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2014;15:257-71. 10.1038/nrm3768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wordeman L, Wagenbach M, von Dassow G. MCAK facilitates chromosome movement by promoting kinetochore microtubule turnover. J Cell Biol 2007;179:869-79. 10.1083/jcb.200707120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maney T, Wagenbach M, Wordeman L. Molecular dissection of the microtubule depolymerizing activity of mitotic centromere-associated kinesin. J Biol Chem 2001;276:34753-8. 10.1074/jbc.M106626200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakajima K, Yin X, Takei Y, et al. Molecular motor KIF5A is essential for GABA(A) receptor transport, and KIF5A deletion causes epilepsy. Neuron 2012;76:945-61. 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Willemsen MH, Ba W, Wissink-Lindhout WM, et al. Involvement of the kinesin family members KIF4A and KIF5C in intellectual disability and synaptic function. J Med Genet 2014;51:487-94. 10.1136/jmedgenet-2013-102182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Terada S, Kinjo M, Aihara M, et al. Kinesin-1/Hsc70-dependent mechanism of slow axonal transport and its relation to fast axonal transport. EMBO J 2010;29:843-54. 10.1038/emboj.2009.389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li TF, Zeng HJ, Shan Z, et al. Overexpression of kinesin superfamily members as prognostic biomarkers of breast cancer. Cancer Cell Int 2020;20:123. 10.1186/s12935-020-01191-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ling B, Liao X, Huang Y, et al. Identification of prognostic markers of lung cancer through bioinformatics analysis and in vitro experiments. Int J Oncol 2020;56:193-205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pan S, Zhan Y, Chen X, et al. Identification of Biomarkers for Controlling Cancer Stem Cell Characteristics in Bladder Cancer by Network Analysis of Transcriptome Data Stemness Indices. Front Oncol 2019;9:613. 10.3389/fonc.2019.00613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bie L, Zhao G, Wang YP, et al. Kinesin family member 2C (KIF2C/MCAK) is a novel marker for prognosis in human gliomas. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2012;114:356-60. 10.1016/j.clineuro.2011.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gan H, Lin L, Hu N, et al. KIF2C exerts an oncogenic role in nonsmall cell lung cancer and is negatively regulated by miR-325-3p. Cell Biochem Funct 2019;37:424-31. 10.1002/cbf.3420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ishikawa K, Kamohara Y, Tanaka F, et al. Mitotic centromere-associated kinesin is a novel marker for prognosis and lymph node metastasis in colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer 2008;98:1824-9. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khemlina G, Ikeda S, Kurzrock R. The biology of Hepatocellular carcinoma: implications for genomic and immune therapies. Mol Cancer 2017;16:149. 10.1186/s12943-017-0712-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zucman-Rossi J, Villanueva A, Nault JC, et al. Genetic Landscape and Biomarkers of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2015;149:1226-1239.e4. 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.05.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang D, Liu J, Liu S, et al. Identification of Crucial Genes Associated With Immune Cell Infiltration in Hepatocellular Carcinoma by Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis. Front Genet 2020;11:342. 10.3389/fgene.2020.00342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ji Y, Yin Y, Zhang W. Integrated Bioinformatic Analysis Identifies Networks and Promising Biomarkers for Hepatitis B Virus-Related Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Int J Genomics 2020;2020:2061024. 10.1155/2020/2061024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wei S, Dai M, Zhang C, et al. KIF2C: a novel link between Wnt/β-catenin and mTORC1 signaling in the pathogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Protein Cell 2021;12:788-809. 10.1007/s13238-020-00766-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen T, You Y, Jiang H, et al. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT): A biological process in the development, stem cell differentiation, and tumorigenesis. J Cell Physiol 2017;232:3261-72. 10.1002/jcp.25797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zaganjor E, Osborne JK, Weil LM, et al. Ras regulates kinesin 13 family members to control cell migration pathways in transformed human bronchial epithelial cells. Oncogene 2014;33:5457-66. 10.1038/onc.2013.486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Debruyne DN, Dries R, Sengupta S, et al. BORIS promotes chromatin regulatory interactions in treatment-resistant cancer cells. Nature 2019;572:676-80. 10.1038/s41586-019-1472-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Han Q, Wang X, Liao X, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic value of WNT family gene expression in hepatitis B virus related hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol Rep 2019;42:895-910. 10.3892/or.2019.7224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liao X, Liu X, Yang C, et al. Distinct Diagnostic and Prognostic Values of Minichromosome Maintenance Gene Expression in Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J Cancer 2018;9:2357-73. 10.7150/jca.25221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ma Z, Liu D, Li W, et al. STYK1 promotes tumor growth and metastasis by reducing SPINT2/HAI-2 expression in non-small cell lung cancer. Cell Death Dis 2019;10:435. 10.1038/s41419-019-1659-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001;25:402-8. 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qiu J, Zhang S, Wang P, et al. BUB1B promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression via activation of the mTORC1 signaling pathway. Cancer Med 2020;9:8159-72. 10.1002/cam4.3411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zou Y, Ruan S, Jin L, et al. CDK1, CCNB1, and CCNB2 are Prognostic Biomarkers and Correlated with Immune Infiltration in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Med Sci Monit 2020;26:e925289. 10.12659/MSM.925289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhu J, Tang B, Li J, et al. Identification and validation of the angiogenic genes for constructing diagnostic, prognostic, and recurrence models for hepatocellular carcinoma. Aging (Albany NY) 2020;12:7848-73. 10.18632/aging.103107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen Z, Xie H, Hu M, et al. Recent progress in treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Cancer Res 2020;10:2993-3036. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Song YJ, Tan J, Gao XH, et al. Integrated analysis reveals key genes with prognostic value in lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Manag Res 2018;10:6097-108. 10.2147/CMAR.S168636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhao L, Zhang J, Liu Z, et al. Identification of biomarkers for the transition from low-grade glioma to secondary glioblastoma by an integrated bioinformatic analysis. Am J Transl Res 2020;12:1222-38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Duan H, Zhang X, Wang FX, et al. KIF-2C expression is correlated with poor prognosis of operable esophageal squamous cell carcinoma male patients. Oncotarget 2016;7:80493-507. 10.18632/oncotarget.11492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang K, Gao J, Luo M. Identification of key pathways and hub genes in basal-like breast cancer using bioinformatics analysis. Onco Targets Ther 2019;12:1319-31. 10.2147/OTT.S158619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Elliott B, Millena AC, Matyunina L, et al. Essential role of JunD in cell proliferation is mediated via MYC signaling in prostate cancer cells. Cancer Lett 2019;448:155-67. 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu M, Qiu YL, Jin T, et al. Meta-analysis of microarray datasets identify several chromosome segregation-related cancer/testis genes potentially contributing to anaplastic thyroid carcinoma. PeerJ 2018;6:e5822. 10.7717/peerj.5822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang GP, Shen SL, Yu Y, et al. Kinesin family member 2C aggravates the progression of hepatocellular carcinoma and interacts with competing endogenous RNA. J Cell Biochem 2020;121:4419-30. 10.1002/jcb.29665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nieto MA, Huang RY, Jackson RA, et al. EMT: 2016. Cell 2016;166:21-45. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.06.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Modi SJ, Kulkarni VM. Discovery of VEGFR-2 inhibitors exerting significant anticancer activity against CD44+ and CD133+ cancer stem cells (CSCs): Reversal of TGF-β induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Med Chem 2020;207:112851. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Llovet JM, Bruix J. Molecular targeted therapies in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2008;48:1312-27. 10.1002/hep.22506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Aravalli RN, Cressman EN, Steer CJ. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Arch Toxicol 2013;87:227-47. 10.1007/s00204-012-0931-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang X, Zhang H, Ye L. Effects of hepatitis B virus X protein on the development of liver cancer. J Lab Clin Med 2006;147:58-66. 10.1016/j.lab.2005.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nakamura H, Aoki H, Hino O, et al. HCV core protein promotes heparin binding EGF-like growth factor expression and activates Akt. Hepatol Res 2011;41:455-62. 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2011.00792.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Delire B, Stärkel P. The Ras/MAPK pathway and hepatocarcinoma: pathogenesis and therapeutic implications. Eur J Clin Invest 2015;45:609-23. 10.1111/eci.12441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen L, Shi Y, Jiang CY, et al. Expression and prognostic role of pan-Ras, Raf-1, pMEK1 and pERK1/2 in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol 2011;37:513-20. 10.1016/j.ejso.2011.01.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dangle PP, Zaharieva B, Jia H, et al. Ras-MAPK pathway as a therapeutic target in cancer--emphasis on bladder cancer. Recent Pat Anticancer Drug Discov 2009;4:125-36. 10.2174/157489209788452812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The article’s supplementary files as